Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Wit & Wisdom® , Alexandria Plan™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2023 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder. Where expressly indicated, teachers may copy pages solely for use by students in their classrooms.

Printed in the USA A-Print

Module Summary 2

Essential Question 3

Suggested Student Understandings 3 Texts 3

Module Learning Goals 4 Module in Context............................................................................................................................... ........................ 6 Standards ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 7 Major Assessments 9 Module Map 11

Focusing Question: Lessons 1–5

How do the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream understand love?

Lesson 1 21

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Functions of a Comma Lesson 2 37

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Examine Academic Vocabulary: Yield Lesson 3 49

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Using Commas with Interrupters Lesson 4 63

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Figurative Language: Puns

Lesson 5 ............................................................................................................................... ...................................... 77

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Commas with Interrupters

Focusing Question: Lessons 6–17

What defines the experience of love?

Lesson 6 85

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Explore Academic Vocabulary: Aggravate, obscenely

Lesson 7 99

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Examine Academic Vocabulary: Dissension Lesson 8 111

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare Lesson 9 123

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Develop Academic Vocabulary: Contagious Lesson 10 135

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore the Morpheme ceiv Lesson 11 145

¢ TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Conditional Verb Mood

Lesson 12 157

n TEXTS: The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Morphemes –ity and –al Lesson 13 ............................................................................................................................... ............................................ 169

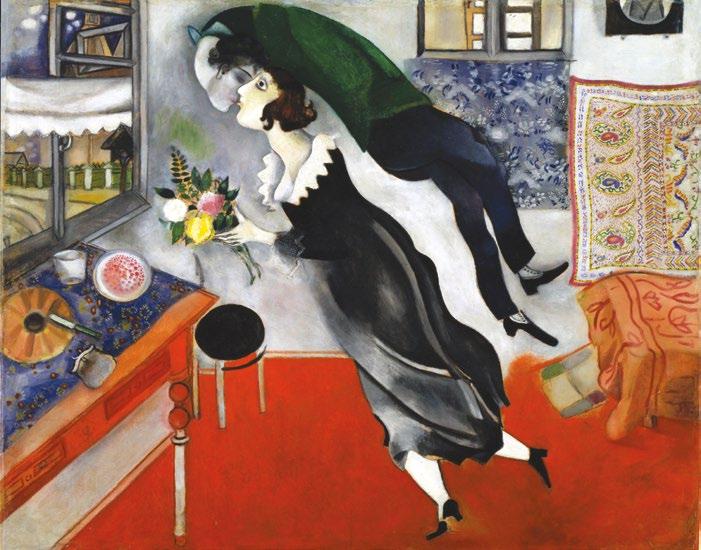

n TEXTS: Birthday, Marc Chagall • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Conditional Verb Mood Lesson 14 181

¢ TEXTS: “What Is Love? Five Theories on the Greatest Emotion of All,” Jim Al-Khalili, Philippa Perry, Julian Baggini, Jojo Moyes, and Catherine Wybourne • Birthday, Marc Chagall • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher • “March of Progress,” Rudolph Zallinger

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore the Morpheme volv Lesson 15 191

n TEXTS: Birthday, Marc Chagall • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Content Vocabulary: Besotted, obsessed Lesson 16 201

n TEXTS: “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher • The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck •

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Conditional Verb Mood

Lesson 17 209

¢ TEXTS: All Module Texts • Birthday, Marc Chagall • The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Conditional Verb Mood

What makes love complicated?

Lesson 18 ............................................................................................................................... ............................................ 219

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “Globe On Screen 2014: A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Content Vocabulary: Entice, enamored, enthralled Lesson 19 233

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment 1 Lesson 20 ............................................................................................................................... .......................................... 245

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore the Morpheme con Lesson 21 255

¢ TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Examine Morphemes ver and fall Lesson 22 265

¢ TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • The Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore the Morpheme –ous Lesson 23 275

n TEXTS: “EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Subjunctive Verb Mood Lesson 24 289

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Academic Vocabulary: Bluff, spared Lesson 25 303

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Subjunctive Verb Mood Lesson 26 315

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Subjunctive Verb Mood Lesson 27 ............................................................................................................................... ........................................... 325

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut • “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Subjunctive Verb Mood Lesson 28 333

¢ TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

Is love real in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Lesson 29 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 339

n TEXTS: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Shifts in Verb Moods

Lesson 30 351

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare • “What Is Love? Five Theories on the Greatest Emotion of All,” Jim Al-Khalili, Philippa Perry, Julian Baggini, Jojo Moyes, and Catherine Wybourne

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Academic Vocabulary: Amity, enmity

Lesson 31 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 363

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Correct Spelling

Lesson 32 373

n TEXTS: All Module Texts ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Spelling Correctly

Is love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream a result of agency or fate?

Lesson 33 383

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment 2

Lesson 34 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 391

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

Lesson 35 397

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel at Using Commas with Interrupters

Lesson 36 405

n TEXT: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Shifts in Verb Moods

Appendix A: Text Complexity .............................................................................................................................. 413

Appendix B: Vocabulary 415

Appendix C: Answer Keys, Rubrics, and Sample Responses 425

Appendix D: Volume of Reading 443

Appendix E: Works Cited 445

“The course of true love never did run smooth” (1.1.136).

In this module, students examine a question that has vexed humans—and the world’s most renowned literary authors—for generations: what is love? Deceptively simple, this question requires students to examine ideas about the roles of individual choice, fate, power, and social status in the development of seemingly personal relations. Their primary testing ground will be Shakespeare’s eternally popular comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which love transforms characters in unexpected ways.

This module challenges the idea that love is a strictly emotional and personal experience, removed from social attitudes, scientific definition, and forces beyond an individual’s control. This study doesn’t negate the personal importance of falling in love or being crushed from heartache; rather, it situates those experiences in larger contexts to ask about the motivations for love and whether we have the freedom to choose whom we love or even understand what love is. The module’s questions compel students to combine intellectual and creative thinking, as they gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of love. They come to discover that love has never been simple or static but nonetheless remains a powerful force in our lives. The meaning of love is the perfect topic to introduce students to argument writing and claim-making, which they practice in written and oral formats.

Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream offers a compelling and humorous way for students to think about love. Shakespeare’s characters introduce multiple, conflicting perspectives about love and about its purpose, place, and power, and students see love wax and wane through the action and inaction of those at love’s mercy in the play. Through this work, students discover the comedy and conflict that erupts when love takes unexpected turns. Magic and confusion abound as the fairies interfere with the human activities in the play. In addition to mirth, A Midsummer Night’s Dream offers opportunities for deep rereading and commenting on the roles of social norms, agency, and fate in the relationships between men and women. Numerous instances of figurative language and wordplay contribute to the density and complexity of this Shakespearean comedy, and they prompt an investigation of the power of figurative language and symbols to communicate humans’ experiences of love.

The human experience of love is considered from a dramatically different perspective in a neuroscientific argument that provides provocative and groundbreaking information on the state of being in love. This is a challenging article, but the scientific point of view provides an excellent counterpart to Shakespeare’s canonical comedy that, in some ways, seems to support similar claims about the power of love to overtake the individual. Furthermore, the article offers an outstanding example of an argument, as it clearly states a claim, counterclaim, and reasoning. Students also read the modern short story “EPICAC,” by Kurt Vonnegut, which, although comedic, raises ethical questions about the actions undertaken in the name of love. Finally, students examine two compelling paintings, The Arnolfini Portrait, painted in 1434 by Jan Van Eyck, and Birthday, painted

in 1915 by Marc Chagall, and analyze how elements such as line and color create very specific and stylized understandings of love.

For their End-of-Module (EOM) Task, students write an argument essay that asserts whether one character from A Midsummer Night’s Dream chose whom they loved at the end of the drama, thus attributing the nature of love to either agency or fate.

What is love?

Love may be a personal and emotional experience, but it is also a physical, mental, and social experience.

Love can be complicated, manipulated, or shaped by factors beyond an individual’s control. Arguments require logical reasoning.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare

Opinion Piece

“What Is love? Five Theories on the Greatest Emotion of All,” Jim Al-Khalili, Philippa Perry, Julian Baggini, Jojo Moyes, and Catherine Wybourne (http://witeng.link/0259)

Birthday, Marc Chagall (http://witeng.link/0258)

The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan Van Eyck (http://witeng.link/0255)

The Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh (http://witeng.link/0274)

“In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction,” Helen Fisher (http://witeng.link/0256)

“EPICAC,” Kurt Vonnegut

Illustration

“March of Progress,” Rudolph Zallinger (http://witeng.link/0260)

“All I Want is You,” Barry Louis Polisar (http://witeng.link/0275)

“Globe On Screen 2014: A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Shakespeare’s Globe (http://witeng.link/0273)

Identify how drama, fiction, and informational texts define love and its impact.

Understand why love is a complex idea and experience.

Analyze how love is affected by social norms, human agency, and matters beyond one’s control.

Determine one or more themes of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to the characters, setting, and plot (RL.8.2).

Analyze the impact of word choices on meaning and tone, including analogies or allusions to other texts (RL.8.4, RI.8.4).

Analyze how differences in the points of view of the characters and the audience (e.g., created through the use of dramatic irony) create effects such as suspense or humor (RL.8.6).

Analyze how a modern work of fiction draws on themes, patterns of events, or character types from myths, traditional stories, or religious works, explaining how the material is rendered new (RL.8.9).

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing the reasoning and evidence, and recognizing when irrelevant evidence is introduced (RI.8.8).

Assert clear and logical evidence-based claims in response to debatable questions (W.8.1.a).

Write an argument essay that supports well-distinguished claims with clear reasons that are developed logically with relevant evidence and demonstrate understanding of the text (W.8.1).

Try a new approach to argument sequencing, by purposefully reordering pieces of an argument to create different effects (W.8.5).

Distinguish claims from alternate or opposing claims, using appropriate transitions (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.c).

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to the task, purpose, and audience (W.8.1.d).

Focus on purpose of discussion through preparation and posing of questions that connect ideas of several speakers using relevant evidence (SL.8.1.c).

Listen to assess the logic of a speaker’s assertions (SL.8.3).

Use grade-appropriate morphemes to infer the meaning of words and verify the preliminary definitions using a dictionary (L.8.4.b, L.8.4.d).

Consult a glossary to find the pronunciation of words and to determine the precise meanings of words (L.8.4.c).

Distinguish among the connotations of words with similar denotations to analyze a text (L.8.5.c).

Accurately use grade-appropriate, general academic, and domain-specific vocabulary (L.8.6).

Form and use verbs in the conditional and subjunctive moods to express uncertainty and hypothetical situations (L.8.1.c, L.8.3.a).

Recognize and correct inappropriate shifts in verb moods (L.8.1.d).

Spell correctly (L.8.2.c).

Knowledge: Students continue their work grappling with big ideas by focusing intently on the concept of agency, or individual choice, in relation to fate, contemplating questions such as: How much do we dictate what happens to us? What defines agency, and can that definition change depending upon circumstances? Are we truly agents in the pursuit of personal experiences like love, or do external or biological drivers dictate them? In a more implicit way, students extend their understanding of sense of self by exploring how love can undermine or empower one’s sense of self. This also gets at the idea that one cannot always control or act on their love because of factors outside their control. Students continue to develop their understanding of the value of the humanities by understanding how literary and artistic texts do not present unilateral and didactic commentary but instead raise important questions about humanity that offer rich opportunities for exploration and spirited debate.

Reading: Students extend their analytical and close reading skills by working with a Shakespearean play with its dense language and sophisticated themes, as well as with a complex scientific article and a contemporary short story that build deep knowledge about love. While reading A Midsummer Night’s Dream, students examine how the central ideas about love are developed in increasingly complex ways through the play’s events and Shakespeare’s use of figurative language and dramatic irony. With the play and short story, students examine the role of fate and agency in love and apply that understanding in their EOM Task through an analysis of the outcome of the romantic relationships in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Students expand their analysis of the claims the play makes about love to explain and evaluate the arguments made in informational texts. Building on their extensive reading of informational texts in previous modules, students hone their analytical skills by discerning the effectiveness of an author’s reasoning and evidence.

Writing: This module features argument writing. Students practice in discrete and manageable steps, focusing on aspects such as evidence-based claims, argument structure, and alternate and opposing claims. With published texts and their peers’ works, students explain and evaluate the claims, logic, and validity of arguments. In formal writing assessments, students demonstrate their ability to construct arguments that include clear and persuasive claims, logical reasoning, relevant evidence, elaboration, an effective sequence with transitional language, and a conclusion.

Speaking and Listening: Students build their speaking and listening skills and develop their work with argument writing by listening for a speaker’s logic and posing questions that connect ideas from multiple speakers.

RL.8.2 Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to the characters, setting, and plot; provide an objective summary of the text.

RL.8.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including analogies or allusions to other texts.

RL.8.6 Analyze how differences in the points of view of the characters and the audience or reader (e.g., created through the use of dramatic irony) create such effects as suspense or humor.

RL.8.9 Analyze how a modern work of fiction draws on themes, patterns of events, or character types from myths, traditional stories, or religious works such as the Bible, including describing how the material is rendered new.

RI.8.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including analogies or allusions to other texts.

RI.8.8 Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; recognize when irrelevant evidence is introduced.

W.8.1 Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence.

W.8.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

W.8.4 With some guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on how well purpose and audience have been addressed. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 1-3 up to and including Grade 8 here.)

L.8.1.c Form and use verbs in the indicative, imperative, interrogative, conditional, and subjunctive mood.

L.8.1.d Recognize and correct inappropriate shifts in verb voice and mood.

L.8.2.a Use punctuation (comma, ellipsis, dash) to indicate a pause or break.

L.8.2.c Spell correctly.

L.8.4.b Use common, grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of a word (e.g., precede, recede, secede).

L.8.4.c Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to find the pronunciation of a word or determine or clarify its precise meaning or its part of speech.

L.8.4.d Verify the preliminary determination of the meaning of a word or phrase (e.g., by checking the inferred meaning in context or in a dictionary).

L.8.5.a Interpret figures of speech (e.g. verbal irony, puns) in context.

L.8.5.c Distinguish among the connotations (associations) of words with similar denotations (definitions) (e.g., bullheaded, willful, firm, persistent, resolute).

SL.8.1.a Come to discussions prepared, having read or researched material under study; explicitly draw on that preparation by referring to evidence on the topic, text, or issue to probe and reflect on ideas under discussion.

SL.8.1.c Pose questions that connect the ideas of several speakers and respond to others’ questions and comments with relevant evidence, observations, and ideas.

SL.8.3 Delineate a speaker’s argument and specific claims, evaluating the soundness of the reasoning and relevance and sufficiency of the evidence and identifying when irrelevant evidence is introduced.

RL.8.10

By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, at the high end of grades 6–8 text-complexity band independently and proficiently.

RI.8.10

By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction at the high end of the grades 6–8 text-complexity band independently and proficiently.

L.8.6 Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

1. Write four informative/explanatory paragraphs that identify and explain one character’s understanding of love from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

2. Write two informative/explanatory paragraphs that explain and evaluate Helen Fisher’s argument in “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction.”

3. Write two informative/explanatory paragraphs that explain how the love triangle in Kurt Vonnegut’s “EPICAC” draws on the complexities of love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and makes this pattern of events new.

4. Write a one-paragraph argument about whether love is strange or true that is supported with reason, evidence, and elaboration.

Summarize events from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Demonstrate an understanding of how a character from A Midsummer Night’s Dream experiences love.

Delineate and evaluate an argument about love.

Recognize strong evidence and various parts of an argument.

Demonstrate an understanding of the complexities of love.

Organize evidence clearly and appropriately to demonstrate reasons.

RL.8.1, 8.2, 8.4; W.8.2.b, 8.4, 8.9.a; L.8.2.a, 8.5.a

RI.8.1, 8.8; W.8.2.a, b, c, d, e, 8.9.b; L.8.1.c, 8.1.d

RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.9; W.8.2.a, W.8.2.b, W.8.2.c, W.8.2.d, W.8.9.a; L.8.1.c, L.8.1.d

Establish a claim and acknowledge an alternate or opposing claim.

Elaborate and expand on evidence to support a claim.

RL.8.1, RL.8.2; W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b, W.8.1.c, W.8.1.d, W.8.1.e; L.8.1.d, L.8.2.c

1. Read an excerpt from Act 2, Scene 2, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Respond to multiplechoice questions, and then write two paragraphs, the first translating Shakespeare, the second explaining the final incident in Scene 2.

2. Read a new informational article, “What Is love? Five Theories on the Greatest Emotion of All.” Respond to multiple-choice questions, and then write two short-answer responses that explain aspects of arguments in the article.

3. Read an excerpt from Act 3, Scene 2, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Respond to multiplechoice questions, and then write two paragraphs analyzing dramatic irony and Robin Goodfellow’s actions in the whole portion of Act 3, Scene 2.

Analyze a specific incident in A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Demonstrate an understanding of Shakespearean language and the action of the play.

Identify a claim, including the strongest evidence to support a claim.

Analyze different qualities of love.

RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.3, RL.8.4; W.8.10; L.8.4.d, L.8.5.a, L.8.5.c

RI.8.1, RI.8.3, RI.8.4, RI.8.8; W.8.10; L.8.4.a, L.8.5.c

Apply an understanding of a particular character’s experience in the play.

Summarize an understanding of a large portion of A Midsummer Night’s Dream

RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.3, RL.8.4, RL.8.6; W.8.10; L.8.4.a, L.8.4.c, L.8.5.a

1. Analyze whether the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and “EPICAC” should be held responsible for their situation or actions.

2. Debate connections between love, imagination, and reality in all module texts, and consider whether love is something that can be defined as “real.”

Synthesize an understanding of the actions and perspectives of different characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Apply an understanding of ideas of fate and agency to characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream

RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.9; SL.8.1, SL.8.6

Analyze love as an abstract idea through collaborative conversation with peers.

RL.8.1, RL.8.2; SL.8.1, SL.8.3, SL.8.6

Write an argument essay that argues whether the outcome of a romantic relationship between one of the four lovers is directed by agency or fate.

Assert and develop an evidence-based claim.

Develop an evidence-based claim with reasons and with well-chosen and wellorganized evidence.

Support the overall sequence of the argument by elaborating on evidence.

RL.8.1, RL.8.2; W.8.1, W.8.4, W.8.5, W.8.9.a; L.8.1.d, L.8.2.a, L.8.2.c

Demonstrate understanding of academic, text-critical, and domainspecific words, phrases, and/or word parts.

Acquire and use grade-appropriate academic terms. Acquire and use domain-specific or text-critical words essential for communication about the module’s topic.

L.8.4.b L.8.6

* While not considered Major Assessments in Wit & Wisdom, Vocabulary Assessments are listed here for your convenience. Please find details on Checks for Understanding (CFUs) within each lesson.

Focusing Question 1: How do the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream understand love?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

1 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.1.1–20

2 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.1.21–129

Wonder What do I notice and wonder about A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Organize What’s happening in Act 1, Scene 1?

3 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.1.130–182

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character relationships reveal?

Examine

Why are commas important?

4 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.1.183–257

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of figurative language in A Midsummer Night’s Dream reveal?

Experiment How do commas and interrupters work? Examine

Why are evidencebased claims important in an argument?

Examine

Why is focusing on the purpose of a discussion important? Experiment

How does making evidence-based claims in an argument work?

Make inferences about characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream using text features (RL.8.1).

Identify the various functions of a comma (L.8.2.a).

Summarize the conflict between Egeus, Hermia, Lysander, and Demetrius (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.4, W.8.10).

Use context to determine multiple meanings and connotations of yield (L.8.4.a, L.8.5.c).

Explain how Hermia and Lysander’s predicament exemplifies Lysander’s description of love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.2, W.8.10, L.8.5.a).

Use commas with interrupters (L.8.2.a).

Analyze how figurative language reveals an idea about love (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.4, L.8.5.a).

Identify an evidence-based claim about a character (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b).

Interpret puns and determine their significance in context of the play (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.4, L.8.5.a).

Focusing Question 1: How do the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream understand love?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

5 FQT

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.1 Distill

What are the central ideas about love in Act 1, Scene 1, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Execute

How do I use commas with interrupters in FQT 1?

Focusing Question 2: What defines the experience of love?

Summarize the plot in Act 1, Scene 1, and explain a particular character’s point of view on the central ideas of love and marriage in a style that is appropriate to a talk show (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.4, W.8.2.b, W.8.4, W.8.9.a, L.8.2.a, L.8.5.a).

Use commas with interrupters to demonstrate understanding of the play (L.8.2.a).

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

6 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1.2 and 2.1.1–150

Organize What’s happening with the fairies in Act 2, Scene 1?

Examine

Why is the structure of an argument important? Examine

Why is listening for a speaker’s logic important?

7 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.1.62–194

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Oberon and Titania’s conflict reveal?

Experiment How does structuring an argument work?

8 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.1.195–276

Distill

What are the central ideas about the experience of love in Act 1 and Act 2?

Execute

How do I write an evidence-based claim? Experiment How does focusing on the purpose of discussion work?

Summarize key details about Titania and Oberon, and make inferences to explain each one’s perception of the couple’s problem (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.3, W.8.10).

Use context to predict the meaning of a word, consult a glossary to clarify its precise meaning, and determine the intended word’s meaning by using a dictionary (L.8.4.a, L.8.4.c, L.8.4.d).

Apply an understanding of Shakespearean language to explain the impact of Titania and Oberon’s conflict around love (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.3, RL.8.4, W.8.10, L.8.5.a).

Delineate the aspects of an argument structure (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b).

Distinguish among the connotations of argument, debate, dissension and feud (L.8.5.c).

Using effective evidence, analyze how a central idea about love in Act 1 is developed in Act 2 (RL.8.1, RL.8.3, RL.8.4, W.8.10, L.8.5.a).

Make an evidence-based claim that is supported by strong evidence and logical reasoning (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b).

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

9 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.2.1–93

Reveal What does a deeper exploration of character conflict reveal in Act 2, Scene 2, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Execute

How do I structure an argument?

Experiment

How does listening for a speaker’s logic work?

10 NR

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 2.2.94–163

Organize What’s happening in Act 2, Scene 2, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Excel

How do I improve argument structure?

The Arnolfini Portrait

Distill What are the themes about love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Execute

How do I listen for a speaker’s logic?

Execute

How do I focus on the purpose of discussion?

Examine

Why is the conditional verb mood important?

Analyze Hermia and Lysander’s conflict in the woods, explaining the rationale for their different perspectives (RL.8.1, RL.8.3, W.8.1.c, W.8.10).

Execute a CREE outline to support an evidence-based claim (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b).

Determine how the connotation of a word develops meaning in a passage, using a glossary to support general understanding of the passage (L.8.4.c, L.8.5.c).

Demonstrate an understanding of the meaning and impact of incidents and language in a new portion of Act 2, Scene 2, of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.3, RL.8.4, W.8.10, L.8.4.d, L.8.5.a, L8.5.c).

Revise an argument outline based on feedback from a peer (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b, W.8.5).

Use context, knowledge of the root ceiv, and various prefixes as clues to the meaning of words and verify preliminary definitions in dictionaries (L.8.4.a, L.8.4.b, L.8.4.d).

Synthesize evidence to identify a theme about the experience of love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, W.8.10).

Analyze peers’ claims about what defines the experience of love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, SL.8.1.a, SL.8.1.c, SL.8.3).

Identify the traits of the conditional verb mood and recognize verbs in the conditional mood (L.8.1.c).

Focusing Question 2: What defines the experience of love?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

12 “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction”

The Arnolfini Portrait

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about the relationship between love and the brain?

Examine

Why is formal style important?

Identify a connection between love, the brain, and addiction in “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction” (RI.8.1, RI.8.4).

Consult a glossary to determine the pronunciation and part of speech of words, and use knowledge of the suffixes –ity and –al to determine the meaning of words (L.8.4.b, L.8.4.c).

13 “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction”

Birthday

Organize

What’s happening in “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction”?

Experiment

How does formal style work? Experiment How does the conditional verb mood work?

14 NR

“What Is love? Five Theories on the Greatest Emotion of All”

Birthday

Reveal What does a deeper exploration of arguments about love reveal?

Identify Helen Fisher’s claim in “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction” (RI.8.1, RI.8.8, W.8.10).

Form verbs in the conditional verb mood (L.8.1.c).

Listen and explain the arguments in a new text (RI.8.1, RI.8.3, RI.8.4, RI.8.8, W.8.10, L.8.4.a, L.8.5.c).

Use knowledge of the root volv and context clues to determine the meaning of evolution (L.8.4.a, L.8.4.b).

15 “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction”

Birthday

Distill What’s the central message of “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction”?

Outline Helen Fisher’s argument, including organization and structure (RI.8.1, RI.8.2, RI.8.8).

Use context to determine the meaning of words and distinguish between the connotations of besotted and obsessed (L.8.4.a, L.8.4.c, L.8.5.c).

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

19

VOC

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 3.2.43–123

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of dramatic irony reveal?

Experiment How does distinguishing opposing claims work?

Analyze how dramatic irony creates humor, suspense, or surprise in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.6, W.8.10).

Distinguish an evidence-based claim from an opposing or opposite claim (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.c).

20 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 3.2.124–226

Organize

What’s happening in Act 3, Scene 2?

Experiment How does distinguishing alternate claims work?

Demonstrate acquisition of gradeappropriate academic and domainspecific words (L.8.4.a, L.8.6).

Summarize the conflict between the four lovers (RL.8.1, RL.8.2).

Distinguish an evidence-based claim from an alternate claim (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.c).

Use knowledge of the prefix con– to determine word meanings and to infer significance of a key passage (L.8.4.b, L.8.5.a).

21 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 3.2.227–365

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of point of view reveal?

22 NR

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 3.2.418–459

Distill

What are the central ideas of A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Execute

How do I distinguish claims in a NewRead Assessment?

Synthesize an understanding of how different points of view can complicate love (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.6).

Apply knowledge of roots and context clues to solve word meaning and verify definitions using a dictionary (L.8.4.b, L.8.4.d).

Analyze how the conflict between the four lovers develops central ideas about love’s complexities in a new portion of text in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.3, RL.8.4, RL.8.6, W.8.10, L 8.4.a, L.8.4.c, L.8.5.a).

Distinguish an original claim from an alternate or opposing claim (W.8.1.a, W.8.1.c).

Use knowledge of affixes and roots to help infer meanings of words (L.8.4.b).

23 “EPICAC” Organize

What’s happening in “EPICAC”?

Examine

Why is the sequence of an argument important? Examine

Why is the subjunctive verb mood important?

24 A Midsummer Night’s Dream

“EPICAC”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the love triangle in “EPICAC” reveal?

Experiment

How does sequencing an argument work?

25 A Midsummer Night’s Dream

“EPICAC”

Distill What are the central ideas of “EPICAC”?

Experiment How does the subjunctive verb mood work?

26 SS A Midsummer Night’s Dream

“EPICAC”

Know

How do A Midsummer Night’s Dream and “EPICAC” build my knowledge of love’s complexities?

Execute

How do I sequence an argument?

Execute

How do I use the subjunctive verb mood in my Knowledge Journal response?

Summarize the relationship between the characters in “EPICAC” (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, W.8.10).

Create a sentence using the subjunctive verb mood (L.8.1.c).

Delineate how the love triangle in “EPICAC” draws on the same pattern of events in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.9, W.8.10).

Use context clues to determine the meanings of bluff and spared, and determine how these words provide insight into the point of view of the narrator in “EPICAC” (L.8.4.a).

Analyze fate and agency in “EPICAC,” drawing on an understanding of situations from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.9, W.8.10).

Form and use verbs in the subjunctive verb mood to express formal suggestions and ideas contrary to fact (L.8.1.c, L.8.3.a).

Apply an understanding of central ideas in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and “EPICAC,” considering how actions taken by characters complicate love through collaborative conversation with peers (RL.8.2, SL.8.1).

Outline an argument, trying a new approach to the order of the sequence (W.8.1, W.8.5).

Use the subjunctive verb mood to achieve particular effects (L.8.1.c, L.8.3.a).

Focusing Question 3: What makes love complicated?

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

27

FQT A Midsummer Night’s Dream “EPICAC” “In the Brain, Romantic Love Is Basically an Addiction”

28

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 3.2.250–295 and 334–365

Know

How do A Midsummer Night’s Dream and “EPICAC” build my knowledge of love?

Excel How do I improve the style of my writing?

Analyze how “EPICAC” develops ideas and patterns of events about the complexities of love found in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and makes them new (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.9, W.8.2.a, W.8.2.b, W.8.2.c, W.8.2.d, W.8.9.a).

Know

How does A Midsummer Night’s Dream build my knowledge of dramatic performance?

Focusing Question 4: Is love real in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

29

Form and use verbs in the subjunctive verb mood in FQT 3 (L.8.1.c, L.8.3.a).

Demonstrate an understanding of Shakespearean drama by participating in a Readers’ Theater and employing wellchosen oral strategies (SL.8.5).

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 4.1

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of point of view in Act 4, Scene 1, reveal?

30

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 5.1

“What Is love? Five Theories on the Greatest Emotion of All”

Distill What is the central idea of A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

Examine

Why are conclusions important?

Experiment

How do verb moods work?

Experiment

How do conclusions work?

Analyze how the outcome of the lovers’ situation in A Midsummer Night’s Dream creates humor, suspense, or surprise (RL.8.1, RL.8.6).

Use and form verbs to achieve particular effects and avoid inappropriate shifts in verb moods (L.8.1.c, L.8.1.d, L.8.3.a).

Analyze how the central idea of love as a fantasy has developed over the course of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2).

Write a concluding statement that follows from and supports an argument (W.8.1.d).

Use context clues to infer word meaning and create mnemonic devices to remember spellings and meanings (L.8.2.c, L.8.4.a, L.8.4.d).

Focusing

31

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

FQT A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 5.1

Know

How does A Midsummer Night’s Dream build my knowledge of love?

Execute

How do I write a concluding statement in a Focusing Question Task?

Execute

How do I spell correctly in my Endof-Module Task?

32 SS All module texts Know

How do module texts build my knowledge of love?

Excel

How do I improve listening for a speaker’s logic?

Excel

How do improve my spelling in my Endof-Module Task?

Focusing

Lesson

33

EOM

VOC

A Midsummer Night’s Dream Know

How does the experience of a character in A Midsummer Night’s Dream build my knowledge of fate and agency?

34 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Know

How does the experience of a character in A Midsummer Night’s Dream build my knowledge of fate and agency?

Excel

How do I improve listening for a speaker’s logic?

Respond to a claim about love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b, W.8.1.c, W.8.1.d, W.8.1.e).

Correctly spell commonly misspelled homophones and words (L.8.2.c).

Analyze love as an abstract idea through collaborative conversation with peers (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, SL.8.1, SL.8.3).

Revise writing to correct spelling errors (L.8.2.c).

Identify evidence that best supports a claim about a character’s pursuit of love in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, W.8.5).

Demonstrate acquisition of gradeappropriate academic and domainspecific words (L.8.4.a, L.8.6).

Establish an argument outline with reasons, evidence, and an opposing claim, using a new approach to sequencing the argument (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, W.8.1.a, W.8.1.b, W.8.5).

Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals35 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Know

How does the experience of a character in A Midsummer Night’s Dream build my knowledge of fate and agency?

Execute

How do I give and receive feedback on an argument essay? Excel

How can I improve my use of commas with interrupters in the rebuttal of my End-ofModule Task?

Revise argument writing in response to peer and teacher review (W.8.1, W.8.5).

Revise EOM Task to use commas with interrupters (L.8.2.a).

36 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Know

How does the experience of a character in A Midsummer Night’s Dream build my knowledge of fate and agency?

Excel

How do I avoid inappropriate shifts in verb mood in my End-of-Module Task?

Finalize draft of an argument essay through self-assessment (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, W.8.1, W.8.4, W.8.5, W.8.9, L.8.1.d, L.8.2.a, L.8.2.c).

Revise EOM Task to avoid inappropriate shifts in verb mood (L.8.1.c, L.8.1.d).

AGENDA

Welcome (5 min.)

Define a Concept Launch (10 min.)

Learn (55 min.)

Examine Shakespearean Language (7 min.)

Examine Text Features (13 min.)

Read to Understand Characters (20 min.)

Research Topics of Interest (15 min.)

Land (4 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (1 min.)

Assign Homework

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Functions of a Comma (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.8.1, RL.8.4

Writing W.8.7, W.8.10

Speaking and Listening SL.8.1

Language

L.8.4.a, L.8.4.c, L.8.4.d L.8.2.a

Volume of Reading Reflection Questions

Make inferences about characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream using text features (RL.8.1).

Record two inferences about Theseus and Hippolyta.

Identify the various functions of a comma (L.8.2.a).

Complete an Exit Ticket to determine function of the comma(s) in each sentence.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–5

How do the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream understand love?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 1

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

In this module, students examine a question that has vexed humans—and the world’s most renowned literary authors—for generations: what is love? Deceptively simple, this question requires students to examine ideas about the roles of individual choice, fate, power, social norms, and science in the development of a seemingly personal and emotional experience. The meaning of love is the perfect topic to introduce students to argument writing and making claims, which they practice in written and oral formats throughout the module. Their primary testing ground for students’ investigation of love is Shakespeare’s eternally popular comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which they begin reading in this first Focusing Question arc. In this sequence of lessons, students focus on closely reading the dense language of Shakespeare’s play. Their analysis of the different characters’ perspectives on love provides a foundation for deeper textual analysis and builds essential understanding for their EOM Task, in which they analyze one character’s experience to make an argument about whether love is the result of agency or fate.

5 MIN.

Students write a three- or four-sentence response to the following question: “How would you explain the idea of love to an alien on their first day on Earth?”

10 MIN.

Post the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and Content Framing Question. Have a volunteer read the Essential Question aloud.

Instruct students to underline two nouns and/or adjectives in their response from the Welcome task that best answer the Essential Question.

Ask: “Look at your responses: why do you think this is an important or interesting question for study?”

Facilitate a brief discussion of responses.

Now provide the following definition, and have students record it in the New Words section of their Vocabulary Journal.

Word Meaning Synonyms universal (adj.) 1. Of, having to do with, or characteristic of the whole world or the world’s population.

1. global, worldwide

2. comprehensive, general

2. For or affecting everyone.

Ask: “Using one or both of these definitions, do you think love is a universal experience?”

Lead a brief discussion of responses.

Now have students share their underlined words with three or four peers.

Then ask: “Based on your shared words, do you think your understanding of love is a universal experience?”

Lead a brief discussion of responses.

Tell students that in this module they examine the Essential Question primarily through studying a play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, by a writer named William Shakespeare. In this first Focusing Question sequence, they begin their examination of love and whether there is a universal understanding of love, by exploring how Shakespeare’s characters understand love.

Distribute copies of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

7 MIN.

Instruct students to form pairs and try to read aloud the first stanza of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, from “Now, fair Hippolyta” to “young man’s revenue” (1.1.1–6).

Encourage students to attempt to pronounce every word. Tell them to notice where they have difficulty but not to worry if they don’t yet understand what the text means.

Have partners Stop and Jot, and ask: “What do you notice about the language and words Shakespeare uses?”

n I notice that Shakespeare uses very formal language.

n I notice there is a lot of figurative language.

n I notice that Shakespeare uses poetic language.

n I notice there are a lot of words I do not know.

Tell students that Shakespeare was writing this and other plays more than four hundred years ago.

Emphasize that the English language has changed and developed a great deal since that time. Tell students that if they met someone from Shakespeare’s time who was speaking English, they might have trouble understanding one another! Given this distance from the time Shakespeare was writing, students may find that reading Shakespeare is challenging and potentially even frustrating. Tell students that people can spend their entire lives studying Shakespeare, and it is extremely difficult for nonexperts to read Shakespeare at any age.

Explain that despite these challenges, Shakespeare has remained one of the most enduring writers in the English language—people have been reading, performing, and discussing his plays for centuries! Shakespeare wrote some of the most beautiful, rich, and complex texts we have available to us today, and Shakespeare is one of the most important and influential figures in literature. Understanding Shakespeare opens up a world of possibilities and connections in literature!

Establish and post a list of class norms and strategies for reading, and add to it throughout the next few lessons. Begin with points such as:

Do not feel like you need to understand every word or line of the play on your first try. Do engage in productive struggle. Do make every effort to stay engaged with the text when you encounter frustration. Do ask for help when you need it!

Tell students that now they examine some tools and tricks that can help them as they read and understand Shakespeare for the first time.

13 MIN.

Instruct students to create a Notice and Wonder T-Chart in their Response Journal. Have a student read the title of the play aloud.

Ask: “What do you notice and wonder about the title of the play?”

Students record their observations and wonderings on the T-chart.

Have students share responses.

n I notice that the play takes place in the summertime.

n I notice the word “midsummer” is not a word we commonly use today.

n I wonder if there will be more than one dream in this play.

n I wonder if the play is about something that is real or something someone imagined.

Inform students that before they begin to examine how the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream understand love, they need to have a basic understanding of how to read a play and the text features that a play contains.

Instruct students to turn to page 3, “Characters in the Play.”

Instruct students to write their observations on the Notice side of the T-chart, and ask: “What does the page show us about the characters?”

n There are names in all capital letters; we learn the character’s names.

n There are names in groups; we learn which characters are similar or related, for example, that Egeus is Hermia’s father.

n After the names, there are descriptions of that character; we learn a little bit about most of the characters.

n We learn what some characters have in common.

n The way the groups are divided suggests the relationship between characters, for example, Hermia, Lysander, Helena, and Demetrius are all “lovers” and there is a group of fairies who work for Titania.

Instruct students to write their wonderings on the Wonder side of the T-chart, and ask: “What do you wonder about the play based on the character list?”

n I wonder where the play happens and what the setting is going to be.

n I wonder why all the characters have such unusual names.

n I wonder what time period the play is set in and when it takes place.

n I wonder what the “four lovers” are like and their relationship to one another.

n I wonder if this is a fantasy story because there is royalty and magical creatures.

Instruct students to jot their wonderings on the Wonder side of the T-chart, and ask: “How do you think the character list relates to the title of the play? Does the list resolve any questions you have or raise any new ones?”

n I wonder if the fairies will be real or part of the dream.

n I wonder if the whole play is one character’s dream.

n I wonder if the whole play takes place at night.

n I wonder if the play is happy, since the word dream is sometimes used as a synonym for the word wonderful.

Have students flip through the text and jot their observations on the Notice side of the T-chart, and ask: “What do you notice about the text features in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?”

TEACHER NOTE

Remind students of text features they have encountered in Grade 8 so far, such as headlines and bylines in a news article, or titles and line breaks in a poem.

n The left-hand page includes words and phrases and definitions of those words and phrases.

n The right-hand page includes the text of the play.

n The text of the play is divided into acts and scenes, like chapters in a book.

n At the beginning of every scene, there is a summary on the left-hand page.

n The text of each act and scene is divided into lines, like poetry.

n The lines of the play are numbered.

n Before each block of text, there is a character’s name in all caps, which probably shows who is speaking.

n There are italicized lines in the play that show when people enter and exit the play.

Have students Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What is the purpose of the left-hand pages?”

n The left-hand pages define some words and phrases that may be unfamiliar to the reader.

n The left-hand pages define words that we use differently than people in Shakespeare’s time.

n The left-hand pages, at the beginning of each scene, have a summary at the top to help orient the reader by explaining what happens in the scene.

Tell students that when they encounter an unknown word or phrase, they should try to determine the word in context and then check the left-hand page to try to determine the definition before using a dictionary.

Now, students will examine how the notes on the left-hand page work.

Instruct students to turn to page 7 of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and mark lines that are defined in the notes section (N) and lines that are not (X).

Ask: “What do you notice about the number of definitions in the notes section?”

n The number of words and phrases defined in the notes is 11 out of 20 lines, over half!

n The notes section provides different definitions for multiple sets of lines and individual words and phrases.

Tell students they will now use the text features they identified to try and understand the first lines of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Display the following line, with citation: “Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour / draws on apace” (1.1.1).

Briefly explain that the way we cite lines in a play can also be a tool to help you find the exact line you are referring to, quickly and easily:

The first number indicates the act, for example, (Act 1).

The second number indicates the scene, for example, (Act 1.Scene 1).

The third number indicates a line or lines, for example, (Act 1.Scene 1.Line 1).

Instruct students to use the citation to locate the line in the play.

Now, students use the text features of the play to respond to the following questions and write their answers in their Response Journal:

Which character is speaking?

Who is this character speaking to?

What does “our nuptial hour” (1.1.1) mean?

n Theseus, the duke of Athens, is speaking this line.

n Theseus is speaking to Hippolyta, the Amazon queen.

n “[O]ur nuptial hour” means “the time for our wedding” (6).

Tell students that text features will be useful for determining definitions of unusual or unknown words and phrases and to get a general gist of what’s happening in the play. Inform students that text features do not replace close reading, but they help clarify challenging passages so students can focus on digging deep into the meaning of the text.

Explain that a play is a unique narrative text that is written for performance. If students were watching a play, they would have other cues, such as the character’s body language or the set design, to help them understand what is happening. Inform students that in a later lesson in this module they will have the opportunity to view a recorded performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Tell them that because there are no descriptions of the setting or events in the printed text of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, they have to pay more attention to the dialogue to understand what is happening and to the meaning of the figurative language to infer what people are thinking and feeling.

Read aloud Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 1–20, and have students follow along in their copies of the text, jotting notes in their Response Journal about what they notice and wonder about the characters they encounter.

Throughout the module, consider using a recorded version of the play (http://witeng.link/0225), which would allow students to hear different actors read different roles, and thus, support their fluency work as students read portions of the play aloud. This portion of text runs from 00:17–01:33.

Ask: “What do you notice and wonder about Theseus and Hippolyta?”

n I notice Theseus and Hippolyta are talking to each other.

n I notice Theseus talks more than Hippolyta does.

n I notice Theseus has a servant.

n I wonder what Theseus and Hippolyta are talking about.

n I wonder what’s going to happen in “four happy days” (1.1.2).

n I wonder how Theseus and Hippolyta know each other.

Ask: “Who are Theseus and Hippolyta?”

TEACHER NOTE Remind students to reference the text features as they answer these initial questions about the play.

n These two characters are royalty: Theseus is the duke of Athens and Hippolyta is the queen of the Amazons.

Reread aloud Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 1–20, and have students follow along in their copies of the text, jotting notes about what they notice and wonder about the content and language of the characters’ remarks.

Ask: “What are these characters saying to each other?”

n Theseus and Hippolyta do not agree with each other.

n They both mention “four days” (1.1.7), and I wonder why Theseus calls them “happy” (1.1.2).

n They both talk about time passing, but Theseus thinks time passes in a “slow” way (1.1.3) and Hippolyta thinks time passes “quickly” (1.1.7).

n They both use similes, for example, Theseus says “like to a stepdame of a dowager” (1.1.5), and Hippolyta says “like to a silver bow” (1.1.9).

Remind students that, in the play, the dialogue between the characters provides insight into their thoughts and feelings, about the situation and their relationship.

Have students start a new page in their Response Journal labeled Character Relationships.

Students Stop and Jot, recording two inferences about Theseus and Hippolyta’s relationship and referencing the text feature that informed their inferences.

Create an anchor chart called Character Relationships. Have students share responses, and add them to the anchor chart. Continue to add observations about character relationships at key moments throughout the module.

Explain that to gain helpful background information about William Shakespeare, and to better understand the original production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, students will conduct brief research about a topic of their choice.

Direct students to page xlviii “An Introduction to this Text,” and ask: “When was this play published?”

n A Midsummer Night’s Dream was published in 1600.

Explain that when we read a play that was written and performed at another point in history, it is always interesting—and illuminating—to understand more about its original production. Tell students to choose one of the following research questions to explore:

What is known about William Shakespeare, and why do we still read his plays?

Where were Shakespeare’s plays originally performed? How did people at the time think about plays and theater?

How did people in Shakespeare’s time understand the language he uses in his plays? Is this how people talked at that time?

Have students quickly find a partner interested in the same topic. Explain that students should research the topic they choose for homework, take notes in their own words in their Response Journal about what they discover, and be ready to share one or two interesting discoveries with two other pairs that focused on the same research questions in the following lesson.

Doing brief, informal research assignments helps students become more comfortable with the research process, practice their skills as researchers without the pressure of having to produce a formal research paper, and learn how to use research to answer questions of interest. These research topics will also help answer some of students’ wonder questions from this lesson and prepare them for a fuller understanding of the rest of the text.

Depending on students’ skills and the technology available, consider letting students search for resources on their own with guidance for how to select sources. Or, consider providing them with links or printed articles from sites like the following:

http://witeng.link/0228. http://witeng.link/0229. http://witeng.link/0231. http://witeng.link/0232.

4 MIN.

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

In their Response Journal, students record one thing they noticed about A Midsummer Night’s Dream and one question they have about the play.

1 MIN.

Students reread Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 1–20.

Additionally, students may continue their research and prepare to share something they learned in the following lesson.

Distribute and review the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions. Explain that students should consider these questions as they read independently and respond to them when they finish a text.

Students may complete the reflections in their Knowledge Journal or submit them directly. The questions can also be used as discussion questions for a book club or other small-group activity. See the Implementation Guide for further explanation of Volume of Reading, as well as various ways of using the reflection.

Students make inferences about characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, using text features (RL.8.1). Given that this is their first encounter with a drama and Shakespeare in this module, it is crucial that students are able to correctly use text features and make inferences about characters to support their success as they continue to read the play. Check for the following success criteria:

Expresses an understanding of Theseus and Hippolyta’s relationship.

If students have difficulty making inferences, direct them to specific lines of text that are supported in the notes section, such as Line 16, which indicates the mood and tone of the scene and could be a jumping-off point for inferences about the relationship between the royal couple.

Time: 15 min.

Text: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Shakespeare, 1.1.1–20

Style and Conventions Learning Goal: Identify the various functions of a comma (L.8.2.a).

STYLE AND CONVENTIONS CRAFT QUESTION: Lesson 1

Examine: Why are commas important?

Refresher on Interrupters (L.8.2.a)

Interrupters are “asides” in a sentence that add additional information but are not essential to the main clause. Interrupters can be a word or phrase, such as however or for instance, or they can add more specific information.

Interrupters are punctuated with two commas. The subject and the predicate of a sentence can be separated by an interrupter framed by two commas but should never be separated by only one comma.

Have students Stop and Jot all the uses of a comma that they can remember. Challenge students to see who can correctly list the most.

Perform a Give One–Get One–Move On to share their ideas.

Call on students, and display student responses.

n Commas separate items in a list.

n Commas separate coordinate adjectives.

n Commas are used to join two independent clauses or two sentences.

n Commas are used to indicate nonrestrictive or unnecessary information.

n Commas are sometimes used to emphasize dependent clauses.

n Commas are used in direct address.

n Commas are used with dialogue.

If students struggle to recall some of the functions of a comma, write examples of commas being used in particular ways on the board, and ask students if the examples remind them of the ways commas can function.

Reveal that they will examine the use of commas in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “After examining the features of the text and reading the first lines, what functions of the comma do you predict will be most common in this play?”

n I think that we will see the comma used frequently for direct address because characters will be talking to one another.

n I think we will also see it with dependent clauses and restrictive elements because the lines in a play are spoken, and we talk with a lot of pauses and added ideas.

n I thought we’d see commas with dialogue, but a play doesn’t use quotation marks.

Direct students to Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 1–20. Read aloud the lines, and tell students to circle all the commas.

TEACHER NOTE When reading these lines, emphasize the commas by intentionally pausing at these points.

Have student pairs identify the function of each comma and write their notes in the margins of the play. Encourage students to return to the displayed list for help. Circulate as students work, offering refreshers about the comma rules as needed.

Call on students to share annotations.

n The first comma is used with “O” (1.1.3). We said that maybe this was a nonrestrictive element.

n The next comma is used with “like to a silver bow / [New]-bent in heaven” (1.1.9-10). This phrase is describing the moon, so it’s nonrestrictive or unnecessary.

n The next comma is used in a direct address to the character Philostrate.

n Then, the next comma is used in a direct address to Hippolyta.

n The comma before the word but is being used to join two sentences, and the last comma is used with another nonrestrictive or unnecessary element.

Direct students’ attention to the commas surrounding “O” (1.1.3).

Read the line aloud, and ask: “Why is Theseus saying ‘O’ (1.1.3) here?”

n It sounds like he is frustrated because time moves so slowly.

n Sometimes people say things like “O,” “ugh,” or “darn” when they are mad or frustrated.

Reveal that these lines show how the comma functions to emphasize interrupters. Interrupters are words and phrases that interrupt the thought(s) in a sentence but are not essential to the main idea(s).

Add another item on the list of comma functions: commas are used to emphasize interrupters. Tell students that they will look at other interrupters in the following lessons.

Land Display:

Theseus, will you marry me?

Egeus, Hermia, Lysander, and Demetrius come to Theseus for help.

Theseus, understandably so, is very eager to marry Hippolyta.

Students complete an Exit Ticket to determine function of the comma(s) in each sentence.

If time remains, have students brainstorm words that might interrupt the flow of ideas in a sentence.

Welcome (5 min.)

Brainstorm Romantic Gestures

Launch (5 min.)

Learn (60 min.)

Share Research (10 min.)

Read to Understand Characters (25 min.)

Annotate for Character Details (10 min.)

Summarize Key Details (15 min.)

Land (4 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question Wrap (1 min.)

Assign Homework

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Examine

Academic Vocabulary: Yield (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.4

Writing W.8.10

Speaking and Listening SL.8.1

Language

L.8.4.a, L.8.4.c, L.8.4.d, L.8.5.a, L.8.5.c

L.8.4.a, L.8.5.c

Summarize the conflict between Egeus, Hermia, Lysander, and Demetrius (RL.8.1, RL.8.2, RL.8.4, W.8.10).

Write two to three sentences that summarize the main conflict in Act 1, Scene 1, using either woo, bewitch, or vexation

Use context to determine multiple meanings and connotations of yield (L.8.4.a, L.8.5.c).

Write one-sentence summaries of Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 69–75 and 81–84, using synonyms for yield that fit the context of the lines.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–5

How do the characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream understand love?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 2

Organize: What’s happening in Act 1, Scene 1?

Students encounter the first conflict of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as they continue to read Act 1, Scene 1, and discuss Hermia’s disagreement with her father when he tries to marry her off to a man she doesn’t love. This work establishes what will become a module-long theme— love is not simple, it is not easy, and it is certainly not gained without a struggle! First, students establish an understanding of the section of text they read in the previous lesson, before moving on to apply their understanding of text features to support their understanding of who Hermia is and why her father is so upset with her. Students are also introduced to the laws of Athens, which are unyielding and give women no control over their future. This work establishes a foundational understanding of some of the different arenas that affect and might exert control over love—familial, social, or even magical.

Display the following questions:

How would you get someone to go on a date?

What are ways to get someone’s attention using social media?

How do you show someone you care about them more than others?

Students consider the displayed questions and brainstorm a list of all the different ways they could engage someone romantically.

5 MIN.

Display the following definitions, and have students record the definitions in the New Words section of their Vocabulary Journal.

woo (v.) bewitch (v.)

To seek to win the love or approval of.

To enchant or cast a spell over with magic or as if with magic. To charm or fascinate.

Have students return to their brainstorm from the Welcome task and identify any examples of romantic gestures that fit the definition of either woo or bewitched

Ask: “Is wooing someone the same romantic gesture as bewitching them? Why or why not?”

Lead a brief discussion of responses.

n Whether you describe a romantic gesture as wooing or bewitching might depend on your opinion of the relationship of the two people involved.

n If someone you like tried to do something romantic, you might think they were wooing you, but if your friend started hanging out with someone you didn’t like, you might say that person bewitched your friend.

n Whether you describe a romantic gesture as wooing or bewitching is particular to your experience. Love might be a universal idea, but that doesn’t mean there is a universal understanding of romantic gestures. It’s about your perspective and how you interpret them.

Post the Focusing Question and Content Framing Question.

Explain that in this lesson students encounter several new characters who have very different ideas about the same romantic gestures.

60 MIN.

SHARE RESEARCH 10 MIN.

Tell students that before they continue their work with the play, they will share what they learned through research.

Have pairs form small groups, with all the students in a group having researched the same question. Partners share their findings with one another.

Then, have each small group share one or two things they learned through their research.

Ask: “How can what you learned help you better understand what is happening in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?”

Possible responses:

n Knowing that people have been reading and thinking about Shakespeare’s plays for hundreds of years can help me feel more comfortable with being confused or taking my time to understand—these plays are challenging and complex, and that’s part of what makes them so lasting!

n Imagining the play as a performance can help me picture what is happening while the characters are speaking and where the characters are in relationship to one another.

n Understanding that plays were originally thought of as entertainment, like modern movies, can help me appreciate the humor and drama of the play and think about how the plot might be similar to entertainment I already enjoy.

n Knowing that people in Shakespeare’s time didn’t talk the way the characters talk helps me feel confident to rely more on context clues to support my understanding, in the same way that Shakespeare’s audiences would have relied on gestures, tone of voice, and expressions to understand the language.

Students record their group members’ research in their Response Journal.

READ TO UNDERSTAND CHARACTERS 25 MIN.

Tell students that before they move on to a new portion of text, they need to orient to the characters and setting of the play. Have students return to their notes from the previous lesson, and ask them to briefly summarize: Who? What? Where?

n Who: The duke of Athens, Theseus, and his fiancé, Hippolyta.

n What: The duke and Hippolyta are about to get married.

n When: In the middle of summer.

n Where: The city of Athens.

Read Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 21–129, aloud as students follow along silently in their portion of the text.

Tell students that they will need to track the characters’ relationships to one another to orient themselves to the events of the play.

Have students review Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 21–129, and annotate for information about the relationship of the new characters they encounter.

Have students Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What are the relationships between Egeus, Hermia, Lysander, and Demetrius?”

Record responses on the Character Relationships Anchor Chart.

Students record these relationships or draw a visual representation of them in their Response Journal.

n Egeus is Hermia’s father.

n Hermia is in love with Lysander.

n Lysander is in love with Hermia.

n Egeus gave Demetrius permission to marry Hermia.

n Egeus hates Lysander.

Have students Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “Why did these characters come to see Theseus?”

n Egeus came to Theseus for help with his problem, his daughter doesn’t want to marry the man he wants her to marry, Demetrius.

n Hermia came to Theseus to try and get permission to marry Lysander.

n Lysander came to Theseus to try and get permission to marry Hermia.

n Demetrius came to Theseus to try and get permission to marry Hermia.

Tell students that as they track relationships, they should not only pay attention to how people are related (e.g., through family or marriage), but also how they feel about one another.

Ask: “How do Lysander, Demetrius, Hermia, and Egeus feel toward one another?”

n Demetrius is angry with Lysander.

n Lysander is angry with Demetrius and Egeus.

n Egeus is angry with Hermia and Lysander.

n Hermia is upset with her father.

Have students add to the Character Relationships Anchor Chart and the related section of their Response Journal.

10 MIN.

Instruct students to reread Act 1, Scene 1, Lines 21–129, and annotate about Hermia’s character as expressed by all of the characters. Remind students to use text features to support their annotations and understanding of the text.

Annotations may include:

n “This man [Lysander] hath bewitched the bosom of my child” (1.1.28).

n “Turned her obedience (which is due to me) / To stubborn harshness” (1.1.38–39).

n “[F]air maid” (1.1.47).

n “I would my father looked but with my eyes” (1.1.58).

n “My soul consents not to give sovereignty” (1.1.84).

Ask: “What do you know about Hermia from this portion of text?”

n Hermia won’t listen to her father when he tells her whom to marry.

n Hermia used to have a good relationship with her father, until she met Lysander.

n Hermia is very beautiful.

n Hermia isn’t afraid to disagree with her father, or with the duke.

n Hermia is stubborn and brave.