Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Wit & Wisdom® , Alexandria Plan™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2023 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder. Where expressly indicated, teachers may copy pages solely for use by students in their classrooms.

Printed in the USA

979-8-88588-746-5

Module Summary 2 Module at a Glance 3 Texts 3 Module Learning Goals 4 Module in Context 6 Standards ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 7 Major Assessments............................................................................................................................... ....................... 8 Module Map 10

Focusing Question: Lessons 1–6 How does someone show a great heart, figuratively?

Lesson 1 ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 19 n TEXT: None ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Etymology of heart Lesson 2 37 n TEXT: None ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Punctuation for Quotations Lesson 3 51

n TEXTS: Biography of Clara Barton • Biography of Helen Keller • Biography of Anne Frank ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Greathearted Lesson 4 61

n TEXTS: Biography of Clara Barton • Biography of Helen Keller • Biography of Anne Frank ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Punctuation for Quotations Lesson 5 73

n TEXTS: Biography of Clara Barton • Biography of Helen Keller • Biography of Anne Frank ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Punctuation with Quotations

Lesson 6 ............................................................................................................................... ...................................... 87

n TEXT: Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), Thomas Eakins

What is a great heart, literally?

Lesson 7 ............................................................................................................................... ...................................... 99

n TEXTS: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj “Exploring the Heart—The Circulatory System!”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Morphology of Circulatory Lesson 8 113

n TEXT: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Chamber

Lesson 9 125

n TEXTS: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj “Exploring the Heart—The Circulatory System!”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Domain-Specific Words

Lesson 10 137

n TEXTS: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj “Grand Central Terminal, NYC”

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Capitalization

Lesson 11 147

n TEXT: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Capitalization

Lesson 12 159

n TEXT: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Capitalization

Lesson 13 167

n TEXTS: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj Image of a subway map

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Commas in Compound Sentences

Lesson 14 179

n TEXT: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Commas in Compound Sentences

Lesson 15 191

n TEXTS: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj “Gallery Walk”

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Commas in Compound Sentences

Lesson 16 201

n TEXT: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Domain-Specific Vocabulary

Lesson 17............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 211

n TEXT: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj

How do the characters in Love That Dog show characteristics of great heart?

Lesson 18 ............................................................................................................................... ................................... 219

n TEXT: “The Red Wheelbarrow,” William Carlos Williams

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Ordering of Adjectives

Lesson 19 229

n TEXT: Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Ordering Adjectives

Lesson 20 241

n TEXTS: Love That Dog, Sharon Creech “The Red Wheelbarrow,” William Carlos Williams “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” Robert Frost

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Ordering Adjectives

Lesson 21 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 255

n TEXTS: “dog,” Valerie Worth Love That Dog, Sharon Creech “The Tyger,” William Blake

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Strategies: Morphology of anonymous Lesson 22 267

n TEXTS: “The Tyger,” William Blake “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” Robert Frost “The Pasture,” Robert Frost Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Strategies: Morphology of immortal Lesson 23 279

n TEXTS: “dog,” Valerie Worth Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Using Quotation Marks When Citing Lesson 24 293

n TEXTS: “Street Music,” Arnold Adoff Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with and Execute Using Quotation Marks Lesson 25 305

n TEXTS: “Love That Boy,” Walter Dean Myers Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Using Quotation Marks Lesson 26 315

n TEXT: Love That Dog, Sharon Creech Lesson 27 323

n TEXT: Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Synthesize Lesson 28 333

n TEXT: Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Words That Reflect a Great Heart Lesson 29 345

n TEXT: Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment 1

Essential Question: Lessons 30–32

What does it mean to have a great heart, literally and figuratively?

Lesson 30 ............................................................................................................................... ................................. 355

n TEXTS: “Heart to Heart,” Rita Dove • Student-selected poems

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment 2

Lesson 31 363

n TEXTS: All module texts

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Style and Conventions Checklist

Lesson 32 371

n TEXTS: The Circulatory Story, Mary K. Corcoran; Illustrations, Jef Czekaj • Love That Dog, Sharon Creech

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Edit for Style and Conventions

Appendix A: Text Complexity............................................................................................................................... ...... 381

Appendix B: Vocabulary 383

Appendix C: Answer Keys, Rubrics, and Sample Responses 391

Appendix D: Volume of Reading 413

Appendix E: Works Cited 415

If I were to speak of war, it would not be to show you the glories of conquering armies but the mischief and misery they strew in their tracks; and how, while they marched on with tread of iron and plumes proudly tossing in the breeze, someone must follow closely in their steps, crouching to the earth, toiling in the rain and darkness, shelterless themselves, with no thought of pride or glory, fame or praise, or reward; hearts breaking with pity, faces bathed in tears and hands in blood. This is the side which history never shows.

—Clara BartonThe heart is both a literal muscle that sustains human life and a figurative center of emotion, love, and desire. In Grade 4 Module 1, A Great Heart, students explore, explain, and challenge these various meanings of the word heart. Students examine literal and figurative uses of heart through quotations from individuals including Confucius, Bill Nye (“The Science Guy”), and Helen Keller. Students deepen their understanding of the people behind these quotations about heart as they study biographies of Clara Barton, Helen Keller, and Anne Frank. These biographies show students how people’s thoughts and actions demonstrate great compassion and courage, thus exemplifying a figurative great heart.

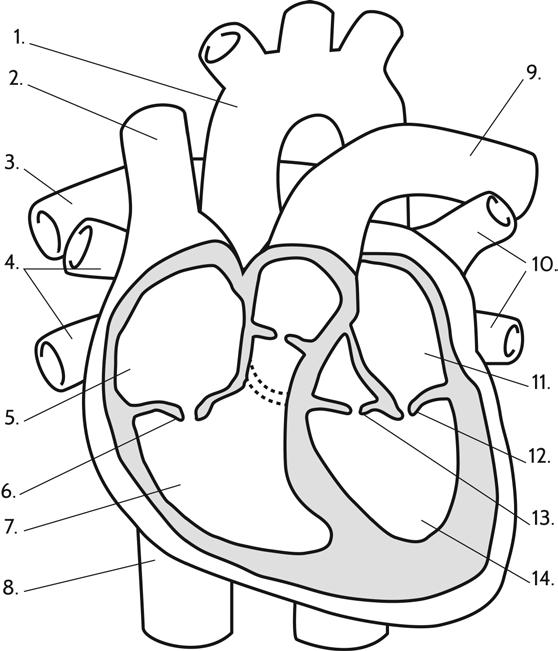

Next, students explore the systemic, pulmonary, and coronary circuits of the literal heart through Mary K. Corcoran’s witty and engaging The Circulatory Story. In that text, readers follow a red blood cell on its journey through the body, and in the process, learn how the body combats disease, performs gas exchanges, and fights plaque in the arteries. This text delves deeply into the literal meaning of a great heart—a heart that is strong and healthy. Although the text is complex, the author weaves in figurative language with the scientific terms and concepts to make the ideas more accessible to Grade 4 students. Studying the science of a great heart and the effect of figurative language helps students build knowledge in both areas.

Students then explore the figurative meaning of heart in Love That Dog, Sharon Creech’s poignant story of a boy who finds his voice. Students first examine his broken heart and then analyze his great change of heart. In Love That Dog, students will read and analyze a series of free-verse poems from the main character’s point of view, as well as the classic poetry referenced in this text. Again, this text helps students as they develop skills in both reading and writing poetry, including the ability to infer deeper meaning from the words of the poems. Students learn how carefully chosen words and phrases can communicate powerful emotions and affect the reader.

Students conclude this module by reading “Heart to Heart,” a beautiful poem by Rita Dove. Through this poem, students examine the differences between the literal heart and a figurative great heart, analyzing how figurative language communicates these concepts in powerful and unexpected ways. Taken together, these rich and varied texts help students become adept at distinguishing the literal and the figurative. In the End-of-Module (EOM) Task, students write an informative essay to explain what it means to have a great heart, both literally and figuratively.

What does it mean to have a great heart, literally and figuratively?

A great heart, literally, is one that pumps blood to keep one’s body healthy. The heart connects to the complex circulatory system, which supplies the body’s cells with oxygen and releases carbon dioxide into the air.

A person who demonstrates a figurative great heart is one who is generous, courageous, or heroic.

Poetry differs from prose in structure and form, and it provides a writer with another vehicle through which to express thoughts and feelings.

“The Red Wheelbarrow,” William Carlos Williams

“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” Robert Frost (http://witeng.link/0663)

“The Pasture,” Robert Frost (http://witeng.link/0787)

“Love That Boy,” Walter Dean Myers (http://witeng.link/0743)

“dog,” Valerie Worth

“Heart to Heart,” Rita Dove (http://witeng.link/0786)

“The Tyger,” William Blake (http://witeng.link/0742)

“Street Music,” Arnold Adoff

“Exploring the Heart—The Circulatory System!” (http://witeng.link/0672)

“Grand Central Terminal, NYC” (http://witeng.link/0668)

“Gallery Walk” (http://witeng.link/0669)

Biography of Anne Frank, Britannica Kids (http://witeng.link/0666)

Biography of Clara Barton, Biography.com (http://witeng.link/0664)

Biography of Helen Keller, Cobblestone

Explain why Clara Barton, Helen Keller, and Anne Frank could each be said to have had a great heart, figuratively.

Explain what makes a human heart great, or healthy.

Identify people or characters who have a figurative great heart because they are generous, courageous, or heroic.

Define a figurative great heart by synthesizing textual details from biographies (RI.4.2).

Determine the main idea and details of both shorter and longer sections of texts about the heart (RI.4.2).

Interpret information presented visually in text features, and explain how the information contributes to an understanding of the text (RI.4.7).

Make inferences about characters and events based on details in a literary text (RL.4.1).

Explain the structure and meaning of poems (RL.4.5).

Create a focus statement about a famous person, and support it with textual details (W.4.2, W.4.8, W.4.9).

Practice integrating paraphrased and quoted evidence from informational and literary texts into a single-paragraph informative/explanatory response (W.4.8, W.4.9).

Write an essay describing the figurative and literal uses of the term great heart, citing textual evidence as support (W.4.2, W.4.8, W.4.9).

Write summaries of narratives and poems (W.4.2, W.4.8).

In small- and large-group discussions, concentrate on peers’ contributions to understand and respond to their ideas (SL.4.1).

Build on others’ ideas in small- and large-group discussions (SL.4.1).

Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (SL.4.1.b).

Differentiate between literal and figurative uses of heart (L.4.4.a).

Demonstrate how punctuation is used with quotations (L.4.2.b).

Identify examples of each rule of capitalization in a given text (L.4.2.a).

Identify an example of figurative language in a complex text, and explain why the author uses figurative language to describe a scientific concept (L.4.5.a).

Use a comma before a coordinating conjunction in a compound sentence (L.4.2.c).

Order a series of adjectives within sentences according to conventional patterns (L.4.1.d).

Knowledge: In this first module of Grade 4, students learn the difference between the literal and figurative use of words by focusing on the multiple meanings of the word heart. Students examine what makes a literal heart “great,” or healthy, by reading an informational text on the circulatory system. Module 1 also explores the concept of a figurative great heart through a series of quotations from famous people, biographies of three women who showed great heart, and a literary text that emphasizes the beauty and power of poetry. These nuanced and abstract concepts prepare Grade 4 students to understand and analyze complex ideas later in the year, such as the struggle to survive in extreme settings, the causes and consequences of war, and the origin and purpose of myths across cultures.

Reading: Students begin Grade 4 by reading a wide range of text types of varying complexity. They read shorter texts, such as brief biographies of famous women and quotations from famous people; a complex scientific text; poetry; and a novel. In The Circulatory Story, students focus on the use of figurative language and illustrations that help readers understand the complex scientific terms and concepts in that informational text. Students then read Love That Dog, a novel that exposes students to the beauty and power of poetry. While reading the novel, students infer information from the unusual structure of the story, which is written in the form of a journal. Students also explore the poetry of Robert Frost, including “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and “The Pasture.” Through these texts, students explore the literal and figurative meanings of the term great heart, helping them explain what it means when someone is said to have a “great heart.”

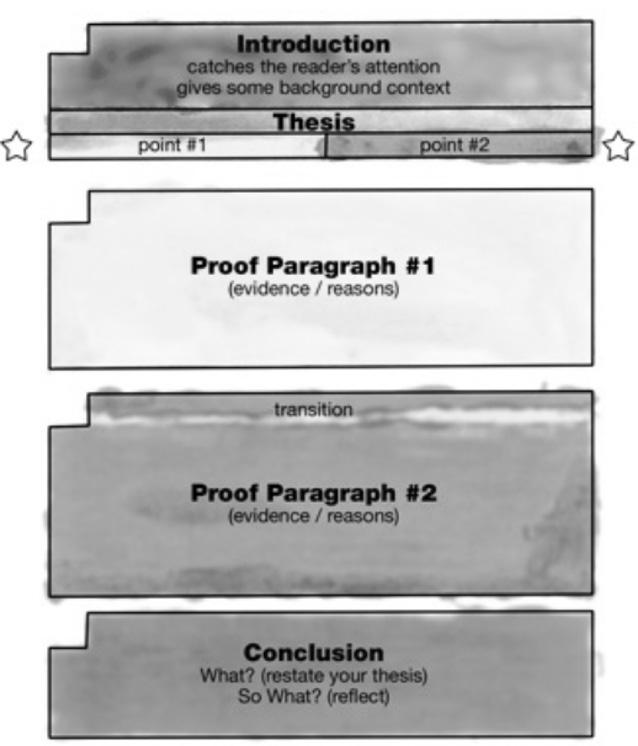

Writing: Students use the Painted Essay® form to examine the structure of an informative text, which includes a focus statement, supporting details, and a conclusion. They then apply that knowledge to write a paragraph describing how a famous woman demonstrated great heart and later, to write a paragraph describing the use of figurative language in a complex science text. Students also learn to summarize both informational and literary texts, and they use their knowledge of a well-constructed essay to write summaries of The Circulatory Story and Love That Dog. In the EOM Task, students apply their knowledge of a well-constructed paragraph to write an informative essay to explain what it means to have a great heart, both literally and figuratively. Students continue to develop their informative writing in future modules, building on the skills they learned in Module 1.

Speaking and Listening: In this first module, students begin to develop the essential skill of concentrating on the words of others. Students establish class norms for speaking and listening and extend their speaking and listening skills in three Socratic Seminars about the literal and figurative meanings of great heart. These Socratic Seminars allow students to discuss both informational and literary texts, and to synthesize evidence from all module texts. In the Socratic Seminars, students elaborate on and respond to others’ thinking and, in the process, revise and rearticulate their own ideas.

RL.4.2 Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text; summarize the text.

RL.4.5 Explain major differences between poems, drama, and prose, and refer to the structural elements of poems (e.g., verse, rhythm, meter) and drama (e.g., casts of characters, settings, descriptions, dialogue, stage directions) when writing or speaking about a text.

RI.4.2 Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details; summarize the text.

RI.4.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words or phrases in a text relevant to a grade 4 topic or subject area

RI.4.7 Interpret information presented visually, orally, or quantitatively (e.g., in charts, graphs, diagrams, time lines, animations, or interactive elements on Web pages) and explain how the information contributes to an understanding of the text in which it appears.

W.4.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

W.4.8 Recall relevant information from experiences or gather relevant information from print and digital sources; take notes and categorize information, and provide a list of sources.

L.4.1.d Order adjectives within sentences according to conventional patterns (e.g., a small red bag rather than a red small bag).

L.4.2.a Use correct capitalization.

L.4.2.b Use commas and quotation marks to mark direct speech and quotations from a text.

L.4.2.c Use a comma before a coordinating conjunction in a compound sentence.

L.4.5.a Explain the meaning of simple similes and metaphors (e.g., as pretty as a picture) in context.

SL.4.1.b Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions and carry out assigned roles.

RL.4.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poetry, in the grades 4–5 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

RI.4.10 By the end of year, read and comprehend informational texts, including history/social studies, science, and technical texts, in the grades 4–5 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

L.4.6 Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases, including those that signal precise actions, emotions, or states of being (e.g., quizzed, whined, stammered) and that are basic to a particular topic (e.g., wildlife, conservation, and endangered when discussing animal preservation).

1. Write an informative paragraph that explains how Clara Barton, Helen Keller, or Anne Frank demonstrated a figurative great heart.

2. Write an informative paragraph that explains what it means to have a literal great heart.

3. Write an informative paragraph to identify a theme in Sharon Creech’s Love

That Dog, and explain how the author develops this theme by showing how Jack changes from the beginning to the end of the story.

Demonstrate an understanding of what it means to have a figurative great heart. Develop a focus statement, and support that focus with textual evidence and elaboration in an informative paragraph.

RI.4.1; W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.9.b; L.4.2.b

Demonstrate an understanding of the circulatory system and the importance of a healthy heart. Develop a paragraph that includes a focus statement supported by evidence paraphrased from the text.

Demonstrate understanding of how the main character, Jack, changes over the course of Love

That Dog

Develop an informative paragraph that includes a focus statement supported by evidence paraphrased from the text.

RI.4.1, RI.4.2, RI.4.3; W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.8, W.4.9.b; L.4.2.a, L.4.2.c

RL.4.1, RL.4.2, RL.4.3; W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.9.a; L.4.1.d, L.4.2.a, L.4.2.b, L.4.2.c

1. Read an excerpt from The Circulatory Story. Then answer multiple-choice items to demonstrate understanding of key vocabulary, main idea and details, and how illustrations contribute to an understanding of the text.

2. Read the poem “Heart to Heart” by Rita Dove, and respond to multiple-choice and constructed-response items to demonstrate literal and inferential understanding.

1. Share ideas and build on what others say to answer a Content Framing Question about the essential meaning of The Circulatory Story in a Socratic Seminar.

2. Engage effectively in a collaborative discussion about Miss Stretchberry’s actions, building on others’ ideas and expressing your own clearly.

3. Engage effectively in a collaborative discussion, synthesizing evidence from literary and informational texts to explain what it means to have a literal and figurative great heart.

Determine the main idea and key details for a section of text.

Demonstrate understanding of key vocabulary related to healthy heart function.

RI.4.2, RI.4.3, RI.4.4, RI.4.7; L.4.4.a

Analyze a poem in a New-Read Assessment to demonstrate comprehension, and analyze the language and structural elements of the poem.

RL.4.1, RL.4.2, RL.4.5; L.4.2.b, L.4.5.a

Demonstrate an understanding of the essential meaning of an informational text.

Demonstrate an understanding of what it means to have a literal healthy heart.

SL.4.1

Demonstrate an understanding of the relationship between Miss Stretchberry and Jack in Love That Dog, and the way in which Miss Stretchberry demonstrates great heart.

SL.4.1

Synthesize evidence from multiple texts to explain a theme.

SL.4.1

Write an informative essay that synthesizes evidence from core literary and informational texts and explains the figurative and literal meanings of the term great heart

Demonstrate an understanding of the difference between literal and figurative uses of the term great heart

Cite textual evidence to support statements about what it means to have a great heart, literally or figuratively.

RL.4.1, RI.4.1; W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.9; L.4.1.d, L.4.2.a, L.4.2.b, L.4.2.c

Demonstrate skill with the elements of an informative essay, including topic sentence, supporting evidence, and a conclusion.

Demonstrate understanding of academic, textcritical, and domain-specific words, phrases, and/or word parts.

Acquire and use grade-appropriate academic terms.

Acquire and use domain-specific or text-critical words essential for communication about the module’s topic.

*While not considered Major Assessments in Wit & Wisdom, Vocabulary Assessments are listed here for your convenience. Please find details on Checks for Understanding (CFUs) within each lesson.

L.4.6

Focusing Question 1: How does someone show a great heart, figuratively?

1

What do I notice and wonder about the word heart?

Examine

Why is evidence important in informative writing?

Differentiate between literal and figurative uses of heart (RI.4.2, RI.4.4, L.4.4.a).

Identify textual evidence to support a focus and organize ideas, citing the source and attributing direct quotation (W.4.8).

Trace the roots of words related to heart, making connections among various cognates (L.4.4.b).

2

What does a deeper exploration of figurative and literal meanings reveal in heart quotations?

Examine

Why is each part of a Painted Essay important? Examine Why is punctuation important?

Analyze quotations to explain their meaning based on the literal or figurative use of the word heart (RI.4.4, L.4.4.a).

Identify the parts of an informative essay and the purpose each serves (W.4.2).

3 Biographies of Clara Barton, Helen Keller, and Anne Frank

4 Biographies of Clara Barton, Helen Keller, and Anne Frank

Organize

What is happening in each biography?

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of each person’s actions reveal in these biographies?

Examine

How does a focus statement work?

Demonstrate how punctuation is used with quotations (L.4.2.b).

Recount the key achievements from the biography of Clara Barton, Helen Keller, or Anne Frank (RI.4.3).

Clarify the precise meaning of the word greathearted (L.4.4.c, L.4.5.c).

Experiment

How does a focus statement work? Experiment

How do punctuation marks for quotations work?

Define a figurative great heart by synthesizing textual details from a biography (RI.4.2).

Create a focus statement about a famous person, and support it with textual details (W.4.2, W.4.8, W.4.9).

Punctuate quotations from given sources (L.4.2.b).

Focusing Question 1: How does someone show a great heart, figuratively?

5 FQT Biographies of Clara Barton, Helen Keller, and Anne Frank

Know

How do the biographies build my knowledge about great heart?

Execute

How do I write an informative paragraph using a focus statement and evidence?

Execute

How do I use punctuation with quotations in my Focusing Question Task 1 response?

In a paragraph with an introduction, focus statement, textual evidence, elaboration, and a concluding statement, explain how a famous woman (Clara Barton, Helen Keller, or Anne Frank). showed great heart (RI.4.1, W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.9.b).

Use punctuation correctly with quoted evidence from a text (L.4.2.b).

6 Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic)

Distill How does Thomas Eakins’s painting, Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic), and a close reading of Dr. Gross’s quotation extend my understanding of a figurative great heart?

Focusing Question 2: What is a great heart, literally?

7 “Exploring the Heart—The Circulatory System!”

The Circulatory Story

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about The Circulatory Story?

8 The Circulatory Story Organize

What is happening in The Circulatory Story?

How do I find evidence to support a focus statement?

Synthesize details from a painting and a quotation to define a figurative great heart (RI.4.4).

Create a focus statement about a famous person, and support it with textual details (W.4.2, W.4.8).

Develop a framework for understanding the text by referring to details and examples in a new text (RI.4.1).

Formulate a definition for the word circulatory after studying the morphology of the word (L.4.4.b).

Use the text structure of The Circulatory Story to determine the main idea of a short section of text, and show how it is supported by key details (RI.4.2, RI.4.5, RI.4.7).

Explain the significance of the word chamber in relation to the heart, and show where the chambers of the heart are located (L.4.5.c).

Focusing Question 2: What is a great heart, literally?

9 The Circulatory Story

“Exploring the Heart—The Circulatory System!”

10 The Circulatory Story

“Grand Central Terminal, NYC”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of figurative language reveal in The Circulatory Story?

Organize

What is happening in The Circulatory Story?

Experiment

Why are evidence/ elaboration sentence sets important?

Identify and explain an example of figurative language in The Circulatory Story (L.4.5, W.4.8).

Examine and Experiment How does paraphrasing in a summary work? Examine

Why is capitalization important?

Use reference materials to clarify the precise meanings of key words and phrases in content-rich texts (L.4.4.c).

Determine the main idea and details to articulate the big ideas of a section of text about the heart (RI.4.2).

Summarize information about the heart using notes from a Boxes and Bullets Chart (W.4.2, W.4.8).

Generate a list of rules for capitalization after examining excerpts from the text (L.4.2.a).

11 The Circulatory Story Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of text features reveal about The Circulatory Story?

Experiment

How does an evidence/elaboration sentence set work? Experiment

What are the rules of capitalization?

Explain how text features contribute to comprehension of the text about blood vessels (RI.4.3, RI.4.4, RI.4.7, L.4.4).

Identify examples of figurative language in The Circulatory Story, and explain why the author uses figurative language to describe parts of the circulatory system (L.4.5, W.4.2, W.4.8, W.4.9).

Identify examples of each rule of capitalization in a given text (L.4.2.a).

12 The Circulatory Story Organize

What is happening in The Circulatory Story?

Execute

How do I use paraphrasing to write my summaries? Execute

How do I use capitalization?

Determine the main idea and details of a section of text about blood vessels, and organize them in a graphic organizer (RI.4.2, RI.4.3, W.4.8).

Independently paraphrase and summarize information about blood vessels into a brief paragraph using notes in a Boxes and Bullets Chart (W.4.2).

Integrate rules for capitalization in writing (L.4.2.a).

13 The Circulatory Story

Image of a subway map

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of text features and figurative language reveal in The Circulatory Story?

Execute

How do I use evidence/elaboration sentence sets to describe how figurative language makes hard ideas easier to understand? Examine

Why are commas in compound sentences important?

Interpret information presented visually in text features, and explain how the information contributes to an understanding of The Circulatory Story (RI.4.7).

Identify an example of figurative language in The Circulatory Story, and explain why the author uses figurative language to describe the blood vessels (L.4.5, W.4.2, W.4.8).

Use commas correctly in compound sentences (L.4.2.c).

14 NR The Circulatory Story Organize

What is happening in The Circulatory Story?

Examine

Why is a wellcrafted introduction important? Experiment

How do commas in compound sentences work?

Demonstrate understanding of key vocabulary and main idea, as well as how illustrations contribute to an understanding of the text in an excerpt from The Circulatory Story (RI.4.2, RI.4.3, RI.4.4, RI.4.7, L.4.4.a).

Explain why a well-crafted introduction in a text is important (W.4.2).

Incorporate commas before coordinating conjunctions in compound sentences (L.4.2.c).

15 The Circulatory Story

“Gallery Walk”

Organize

What is happening in The Circulatory Story?

Execute

How do I use commas in compound sentences?

Determine and paraphrase the main idea and figurative language in a section of text (RI.4.2, L.4.5, W.4.8, SL.4.1, SL.4.2).

Correctly use commas and conjunctions in compound sentences that relate to The Circulatory Story (L.4.2.c).

Focusing Question 2: What is a great heart, literally?Focusing Question 2: What is a great heart, literally?

16 SS The Circulatory Story Distill

What is the essential meaning of The Circulatory Story?

17 FQT The Circulatory Story Know

How does The Circulatory Story build my knowledge about a great heart, literally?

Execute

How do I use evidence from The Circulatory Story in my Focusing Question Task 2 response?

Infer what makes a heart healthy, using knowledge learned from reading The Circulatory Story (RI.4.2, RI.4.7).

Share ideas and build on what others say to answer a Content Framing Question about the essential meaning of a text in a Socratic Seminar (SL.4.1).

Apply knowledge of content-specific vocabulary about the heart to label a heart diagram (L.4.6).

Gather evidence about a literal great heart, and explain what it means to have a literal great heart by writing an informative paragraph with a focus statement, evidence and elaboration, and a conclusion (RI.4.1, RI.4.2, RI.4.3, W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.8, W.4.9.b, L.4.2.a, L.4.2.c).

Focusing Question 3: How do the characters in Love That Dog show characteristics of great heart?

18 “The Red Wheelbarrow” Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about “The Red Wheelbarrow”?

Examine

Why are adjectives important in “The Red Wheelbarrow”?

Analyze the rules the poet used to craft “The Red Wheelbarrow” to determine the poem’s structure and organization (RL.4.5).

Evaluate writing for vivid use and correct order of adjectives (L.4.1.d).

19

What do I notice and wonder about Love That Dog?

Examine

How does a narrative summary work?

Experiment

How does the process of ordering adjectives work?

Interpret the journal narrative structure to infer events between Jack’s entries (RL.4.1).

Analyze the characteristics of an effective narrative summary (RL.4.2).

Test text-based phrases to generalize the order of adjectives (L.4.1.d).

20

“The Red Wheelbarrow”

“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of poetic elements reveal about “The Red Wheelbarrow” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”?

Execute

How do I order adjectives when writing?

21 “dog”

Love That Dog

“The Tyger”

22 “The Tyger”

“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”

“The Pasture”

Love That Dog

23 “dog”

Love That Dog

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Jack’s journal entries reveal in Love That Dog?

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of poetry elements reveal in Robert Frost’s poems?

Execute

How do I use details in an effective summary?

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the book’s structure reveal in Love That Dog?

Examine

How do I use evidence to write a supporting paragraph? Examine

Why is using proper punctuation when quoting an author important?

Analyze a Robert Frost poem for craft (e.g., repetition, rhythm, and rhyme) (RL.4.1, RL.4.5). Explain how knowing the elements of poetry helps to understand the meaning of a poem (RL.4.2). Order multiple adjectives in a phrase or sentence according to established rules (L.4.1.d).

Summarize key events from a novel (RL.4.2, W.4.2, W.4.8). Study the root of anonymous, and infer why Jack asks what it means in Love That Dog (L.4.4.b).

Summarize Robert Frost’s poem “The Pasture” (RL.4.3, W.4.2).

Describe why William Blake described the creator of the tiger as immortal in the poem “The Tyger” (L.4.4.b).

Analyze the text structure of Love That Dog (RL.4.3, RL.4.5).

Analyze how evidence is used in an informative paragraph (W.4.2, W.4.9).

Formulate the proper use of quotation marks when quoting an author or speaker (L.4.2.b).

Focusing Question 3: How do the characters in Love That Dog show characteristics of great heart?24 “Street Music”

Love That Dog

Distill

What are the themes in the text and poems of Love That Dog?

Execute

How do I use evidence to write an informative paragraph? Experiment and Execute

How do quotation marks work when quoting text?

Determine the themes in Love That Dog (RL.4.2).

Write an informative paragraph about one of the themes in Love That Dog (RL.4.2, W.4.2, W.4.9).

Develop the proper use of quotation marks when quoting text (L.4.2.b).

25

Love That Dog

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Jack’s writing reveal in Love That Dog?

Execute

How do I use evidence to write a supporting paragraph?

Execute

How do I use correct punctuation with quotations, commas, and ending marks?

Analyze the text to find evidence of Jack’s figurative great heart (RL.4.3, W.4.8).

Describe and explain Jack’s figurative great heart, supporting points with evidence from the text (RL.4.3, W.4.2).

Integrate the proper use of quotation marks when quoting text (L.4.2.b).

26 SS Love That Dog Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Miss Stretchberry’s character reveal in Love That Dog?

Execute

How do I listen closely and build on others’ comments in a Socratic Seminar?

Explain how inferences drawn from the text reveal Miss Stretchberry’s actions (RL.4.3, W.4.8).

Engage effectively in a collaborative discussion about Miss Stretchberry’s actions, building on others’ ideas and expressing your own clearly (SL.4.1).

27

What does a deeper exploration of Jack’s dog poem reveal in Love That Dog?

28

What are the themes of Love That Dog?

Excel

How do I write a well-developed informative paragraph to analyze theme?

Identify elements of poetry Jack uses in his poem (RL.4.3).

Identify what Jack’s poem reveals about his great heart (RL.4.3).

Demonstrate how to synthesize evidence to support a point (L.4.6).

Articulate a theme of Love That Dog—and how it relates to a change in Jack’s character—by writing a welldeveloped informative paragraph (RL.4.1, RL.4.2, RL.4.3, W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.9.a, L.4.1.d, L.4.2.a, L.4.2.b, L.4.2.c).

Build connections between words related to a great heart (L.4.4.c, L.4.5.c).

Focusing Question 3: How do the characters in Love That Dog show characteristics of great heart?29 V Love That Dog Know

How does Love That Dog build my knowledge?

Execute

How do I use evidence to show what I know about Love That Dog?

Gather and record evidence to support the point that Jack, Miss Stretchberry, or Walter Dean Myers show figurative great heart in Love That Dog (RL.4.3, W.4.8).

Summarize learning from reading Love That Dog into knowledge statements (RL.4.2, RL.4.3, W.4.8).

Demonstrate knowledge of module content vocabulary by defining words in context (L.4.6).

30 NR V

“Heart to Heart”

Studentselected poems

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of its elements and language reveal about the poem “Heart to Heart”?

31 SS All module texts Know

How do the module texts build my knowledge about a great heart, both literal and figurative?

Excel

How do I synthesize evidence to answer the Focusing Question in a Socratic Seminar?

Excel

How do I improve the use of Module 1 Language skills in context?

Analyze Rita Dove’s poem “Heart to Heart” in a New-Read Assessment to summarize and demonstrate understanding of the poem and its elements (RL.4.1, RL.4.2, RL.4.5, L.4.2.b, L.4.5.a).

Demonstrate knowledge of module content vocabulary by defining words in context (L.4.6).

Synthesize evidence from multiple texts in a Socratic Seminar (RL.4.1, RI.4.1, RI.4.9).

Cite textual evidence to support statements about what it means to have great heart, literally and figuratively (RL.4.1, RI.4.1, SL.4.1).

32 EOM The Circulatory Story

Love That Dog

Know

How do the module texts build my knowledge about a great heart, both literal and figurative?

Execute

How do I use my informative writing skills to respond to the EOM Task?

Excel

How do I improve my use of Module 1 Language skills in the context of my EOM Task response?

Write an informative essay with evidence from the module’s core texts that tells what it means to have a great heart, literally and figuratively (RL.4.1, RI.4.1, W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.9, L.4.1.d, L.4.2.a, L.4.2.b, L.4.2.c).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-appropriate style and conventions (L.4.1.d, L.4.2.a, L.4.2.b, L.4.2.c).

Focusing Question 4: What does it mean to have a great heart, literally and figuratively?Welcome (5 min.)

Define heart Launch (5 min.)

Learn (55 min.)

Explore Literal and Figurative Meanings for heart (10 min.)

Annotate and Analyze Two Heart Quotations (15 min.)

Organize Textual Evidence (30 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question Wrap (5 min.)

Assign Homework

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Etymology of heart (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RI.4.2, RI.4.4

Writing W.4.8

Speaking and Listening SL.4.1

Language L.4.4a L.4.4.b

Display copy of evidence organizer (see lesson for model)

Handout 1A: Quotations by Barnard and Confucius

Index cards

Plain paper

Yellow and blue highlighters

Differentiate between literal and figurative uses of heart (RI.4.2, RI.4.4, L.4.4.a).

Complete an Exit Ticket demonstrating understanding of the literal and figurative uses of heart

Identify textual evidence to support a focus and organize ideas, citing the source and attributing direct quotation (W.4.8).

Complete an evidence organizer for a quotation about the heart.

Trace the roots of words related to heart, making connections among various cognates (L.4.4.b).

Make connections among the Latin and Greek word parts cor and cardi and the literal and figurative uses of the word heart

What does it mean to have a great heart, literally and figuratively?

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–6

How does someone show a great heart, figuratively?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 1

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about the word heart?

CRAFT QUESTION: Lesson 1

Examine: Why is evidence important in informative writing?

Students explore the word heart, considering its literal and figurative meanings. Students begin the process of reading, annotating, and analyzing texts by working with two short quotations that use the word heart literally or figuratively. Delineating the two uses of heart prepares students for the module’s work. Over the course of this module, students develop a deep understanding of the heart, both how the literal human heart functions in the body as well as how the figurative heart represents the center of the human spirit and emotions. In this lesson, students practice annotation and evidence gathering to develop skills in close reading and tracking textual evidence for writing. This knowledge of heart and these fundamental reading and evidence collection skills support the writing throughout the module and build toward students’ performance on the EOM Task.

5 MIN.

Distribute an index card to each student.

Display these directions:

What comes to mind when you think of the word heart? Choose one of the following ways to express your ideas about the word heart

1 Draw a picture of a heart.

2 Write a sentence that uses the word heart

3 Define the word heart.

4 Do a word association, and list as many words as you can that connect to the word heart

5 Make a short rhyme or a poem that uses the word heart.

Students work independently.

5 MIN.

Post the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and Content Framing Question.

Explain that these questions set the purpose for learning and illuminate what students will study over the whole module (Essential Question), in an arc of lessons (Focusing Question), and in this lesson (Content Framing Question).

Have students Choral Read the Content Framing Question. Explain that this lesson will answer this question and help answer the Focusing Question.

Ask students to Think–Pair–Share their Welcome activity ideas.

Ask: “What do you notice about your different ideas about heart?”

n Some people drew a heart shape, but other people tried to draw an actual heart.

n My partner and I thought about how the heart shows your feelings.

n There was more than one true meaning for the word heart

n Some people were talking about the heart that beats inside your body and pumps blood.

n Quite a few people mentioned love.

TEACHER NOTE

If the entire class focused only on either the figurative or the literal meaning of heart, it is okay. Students will expand their understanding through the rest of the lesson.

55 MIN.

Display the following sentences, and ask students how they are alike:

It’s raining cats and dogs. Has the cat got your tongue?

That coat costs an arm and a leg. She said she would say what she meant and not beat around the bush. She is the breadwinner in the family.

He was as cool as a cucumber when he gave his speech.

My legs turned to jelly.

Allow time for students to recognize that all of these phrases have a meaning beyond their literal meaning.

Explain that words or phrases sometimes have different meanings and uses. For example, the phrase it’s raining cats and dogs does not mean animals are falling from the sky; this phrase means “it is raining hard.” This phrase is an example of figurative language

Tell students that when we talk about words or phrases, we often talk about their meanings as being either literal or figurative.

Ask students to take out their Vocabulary Journal. Provide the following definitions for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

literal (adj.) The usual or exact meaning of a word or phrase.

metaphorical

concrete, exact figurative (adj.) Not meant to be understood in a literal way; expressing something in an interesting way; using words to mean something beyond their ordinary meaning.

Ask students to think back to the class’s Welcome activity responses. Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “How is the word heart used in a literal way? How is it used in a figurative way?”

Then, provide both literal and figurative definitions for the word heart for students to add to their

Vocabulary Journal.

heart (n.) (literal meaning)

heart (n.) (figurative meaning)

The muscular organ in the chest that pumps blood throughout the body.

A person’s deepest feelings or true personality; feelings of love, affection, or sympathy. soul; compassion

Ask additional volunteers to share their Welcome activity responses, and identify each response as either figurative or literal.

Display a list of sentences with common expressions about the heart.

He has a sweetheart back home.

She had a broken heart.

An average heart is the size of your fist.

She ate a heart-healthy snack.

I love you from the bottom of my heart.

I can play the piano by heart.

Exercise can make your heart stronger.

Eat your heart out.

Think with your head, not your heart.

His grandfather had a heart attack.

They had a heart-to-heart talk.

Ask students to identify each as either a figurative use of the word heart or a literal use.

Then ask students to come up with their own phrase or sentence and tell if it is literal or figurative.

Review the module’s Essential Question: What does it mean to have a great heart, literally and figuratively? Invite students on a literary journey to discover what it means for a person to have a great heart.

Distribute Handout 1A, and display the quotations.

“It is infinitely better to transplant a heart than to bury it to be devoured by worms.” —Christiaan Barnard, the first cardiovascular surgeon to transplant a human heart

15 MIN.

“Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” —Confucius, a Chinese philosopher

Read aloud the two quotations without interjecting discussion or definitions.

Tell students that to annotate means to “add notes or comments.” Annotating can help readers focus on a text and keep track of what they notice and wonder as they read. Read aloud the directions for annotating text at the bottom of the page.

Mark ? for questions.

Circle unknown words.

Write observations in the margins.

Allow students to work silently for a few minutes, annotating the quotations to mark questions, unknown words, and observations.

Work with a small group of students if they need more support to annotate the text while others work independently.

As a whole group, focus on the Barnard quotation first. Have students identify unfamiliar words they circled. Then have them share what they know or infer from the context of the meanings of any circled words.

Using the displayed handout, demonstrate how to jot down short definitions above the circled words, inserting “much” above infinitely, “move from one place to another, or one body to another” above transplant, or “eaten” above devoured. Give students a moment to discuss and annotate unknown words.

Ask: “What does Dr. Barnard’s quotation mean?” Ensure that students understand the meaning of the quotation.

Inform students they will now work together to complete the final direction. Read aloud the fourth annotation direction at the bottom of the page:

Write an F or L to show whether the speaker is using the word heart figuratively or literally.

Call for students to signal by raising their left hand if the word heart is used in a literal way or their right hand if it is used in a figurative way. Affirm that Dr. Barnard’s quotation is literal. Have students write an “L” next to the quotation.

Ask students to read the second quotation, from Confucius.

Ask: “What advice does Confucius give in this quotation?” Ensure that students understand the quotation.

Call for students to raise their left hand if the word heart is used in a literal way or their right hand if it is used in a figurative way. Affirm that Confucius’ quotation is figurative. Have students write an “F” next to the quotation.

Tell students that in this module, they will practice informative writing. Ask: “What kind of writing is informative writing? How is it different from writing an opinion or writing a story?”

n Informative writing teaches readers about a topic.

n It can explain something.

n It tells about facts. It might be about history or science.

n An opinion tries to convince someone to do something or think something.

n A story is not true.

Tell students that in this module, they will read different texts about the literal heart and the figurative heart. Tell them that as they read, they will collect evidence to support their ideas.

Just as they annotated to take notes while they read, students can use an organizer to keep track of their ideas.

Throughout this module, students will use a graphic organizer called an evidence organizer. This lesson introduces students to the organizer and gives them practice using it. As needed, define terms like row and column so that students can follow along. A working understanding of how and why to use the organizer will help students in their reading and writing activities throughout the module.

Display the evidence organizer.

What does the word heart mean, literally and figuratively?

Focus Statement:

Who says this? Quote or paraphrase Where does this information come from? Literal or figurative? Why?

Discuss the parts of the evidence organizer, and explain the purpose of each row or column.

The top of the evidence organizer has space to write a focus statement. Sometimes you start with the focus statement. Other times, the evidence helps you decide what your focus statement will be. The focus statement tells the topic or big idea. This is why this space is at the top.

The first column is for context. Here you can give background about your text. Because we have two quotations, I would identify the speaker of each quotation in a separate row.

The next column is where you can write evidence from the text. You can copy the exact words from the text or paraphrase in your own words. (Remind students to use quotation marks when they use the exact words from the text.)

The third column is for the source of the evidence. You can list the text title here. For these quotations, I would write “Handout 1A.” (As needed, explain that the source is “the book or place from where the information, evidence, or quotation came.”)

The last column is a space to elaborate and explain the evidence. This is where you can explain why the evidence is important. You can elaborate on how it connects to the focus. (As needed, define elaboration: “the action of adding more detail to a simple text or statement.”)

Tell students that you will fill out the evidence organizer together for the first quotation, but you will wait to add the Focus Statement until after you have added to the Evidence and Elaboration/ Explanation sections of the organizer.

Add Christiaan Barnard’s name to the first cell, identifying him as a doctor, and add “Handout 1A” to the third cell.

Then, ask: “What does the first quotation say? How would you paraphrase it, or say it in your own words?” Record student responses in the class evidence organizer for display.

n The first quotation says, “It is infinitely better to transplant a heart than to bury it to be devoured by worms.”

n This means it is better to donate your heart to another person after you die than to have it simply decay in the ground. Or, it is better to reuse a heart than to throw it away.

Ask: “Does this quotation use the word heart in a literal way or a figurative way?” Record student responses in the class evidence organizer for display.

n The word heart is used literally.

n Heart refers to a body part.

n Barnard is talking about moving an actual heart from one body to another.

n He is talking about the heart that is the muscle that pumps blood through our bodies.

Next, highlight the evidence and elaboration about the Barnard quotation in yellow. Point out that this information identifies evidence, includes the quotation and its meaning, and then elaborates on how the evidence shows a literal use of the word heart.

Tell students they will now complete the next row of the organizer on their own. Ask students to take out their Response Journal and make four columns on a page by drawing five vertical lines down the page. Model for students. Tell students to label the first column “Context,” the second “Evidence,” the third “Source,” and the fourth “Elaboration/Explanation.” Tell students that in the next lesson they will see how this evidence organizer connects to writing a paragraph.

Students can work individually, in pairs, or in small groups for this activity.

Students complete a row of the evidence organizer in which they analyze the Confucius quotation, stating who said the quotation, what it means, whether the quotation uses the word heart literally or figuratively, and listing Handout 1A as the source.

As students share their learning with the whole group, add their ideas to the class chart. Highlight the entries about the Confucius quotation in blue.

What does the word heart mean, literally and figuratively?

Focus Statement:

Context Evidence Source Elaboration/Explanation

Who says this? Quote or paraphrase

Christiaan Barnard, doctor “It is infinitely better to transplant a heart than to bury it to be devoured by worms.”

When you die, it is better to donate your heart to a living person than to bury it in the ground. It is better to reuse a heart than to throw it away.

Where did this information come from?

Literal or figurative? Why?

Handout 1A Literal

Barnard means moving an actual heart from one body to another; this is the muscle that pumps blood through our bodies.

Confucius, Chinese philosopher

“Wherever you go, go with all your heart.”

When a person goes somewhere or does something, they need to give that place or activity their full attention.

Handout 1A

Figurative

This can’t mean the physical heart because it always goes with you. So if you have to remember to bring it, this means it is the idea of your “heart.”

For example, when I go to school, I need to be there with all of my attention, and when I go to baseball practice, I need to be there with my effort and my emotions.

Invite students to review the whole chart. Ask: “What are the big ideas?”

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share to generate ideas for what to add to the space for the focus statement at the top of the organizer.

As a whole group, generate a class focus statement to add to the evidence organizer.

n The word heart is an interesting word because it can be used both literally and figuratively.

Extension

If students are ready and time allows, explain that the information recorded in the evidence organizer can be used to write sentences and paragraphs that can support the focus statement. Model how to use the information in the evidence organizer to create supporting evidence/elaboration sentences.

I can turn the information in the evidence organizer into sentences to support the focus statement.

For example, I can use the first row to explain the meaning of Barnard’s quotation:

Christiaan Barnard was concerned about the literal human heart. He was the first heart surgeon to perform a heart transplant. He said, “It is infinitely better to transplant a heart than to bury it to be devoured by worms.” He meant that when you die, it is much better to donate your heart to a living person who needs it than to bury it in the ground. Barnard uses the word heart in a literal way because he is talking about an actual beating heart that pumps blood through the body.

Then I can use the information in the second row of the evidence organizer to create sentences about Confucius.

Confucius thought about the heart figuratively. He was an ancient Chinese philosopher who said, “Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” He meant when a person goes somewhere or does something, he or she should give full attention to it. For example, when I go to school, I need to be there with all of my attention, and when I go to baseball practice, I need to be there with my effort and my emotions. Confucius used heart in a figurative way because he is referring to a person’s mind and spirit, not their physical, beating heart.

Or, model for just the first, yellow section of the evidence organizer and invite students to write in complete sentences using the second, blue section.

Repeat the Craft Question: Why is evidence important in informative writing? Ask students to Think–Pair–Share to discuss the question.

n Evidence is important when we write because it supports our ideas about a focus.

n Evidence shows what we learned from reading a text.

n Evidence, including facts, shows that we know the topic.

n Evidence gives us a chance to elaborate on a topic.

Explain that the next lesson will demonstrate how the evidence organizer notes can help plan informative writing. Save the completed evidence organizer for display in the next lesson.

5 MIN.

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about the word heart?

Distribute a plain sheet of paper to each student. Ask students to hold it horizontally and fold it in half. Tell students that they will now complete an Exit Ticket; this sheet of paper will be their ticket “out” of class.

For an Exit Ticket, students write two sentences. On the top half of the paper, students write one sentence that uses the word heart in a literal way. On the bottom half, they write a sentence that uses heart in a figurative way.

Wrap5 MIN.

Students ask three people, not in class, “What does the word heart mean?” and record the answers in the form of a quotation. For each response, students determine if heart is used figuratively or literally.

Distribute and review the list of additional texts from Appendix D: Volume of Reading, and the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions (see the Student Edition). Explain that the list contains books with further information about topics discussed in the module. Tell students to consider the reflection questions as they independently read any additional texts and respond to them when they finish a text.

Students may complete the reflections in their Knowledge Journal, or submit them directly. Students can also use the questions as discussion questions for a book club or other small-group activity. See the Implementation Guide ( http://witeng.link/IG ) for a further explanation of Volume of Reading, as well as various ways of using the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions.

Students’ Exit Tickets demonstrate their understanding of the literal and figurative meanings of the word heart (RI.4.2, RI.4.4, L.4.4.a). Separate the Exit Tickets into three piles—“Gets It,” “Almost There,” and “Not There Yet”—according to the following criteria:

Students who “get it” will use the figurative meaning of heart to describe strong character in one sentence, and the literal meaning of heart to describe a physical beating heart in the other sentence.

Students who are “almost there” will have one sentence correct.

Students who are “not there yet” will not be able to use the figurative or literal meanings of heart in sentences.

For students who need more practice with the literal and figurative definitions for heart, explicitly explain the definitions in the next lesson when students continue to work on these definitions. You may also need to work with a small group to clarify the definitions. Remind students that they will continue to work with the different meanings of heart throughout the entire module, so it is okay if they are still learning the concepts. They should keep asking questions about how the word is being used to develop an understanding of the difference.

Time: 15 min.

Texts: None

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Trace the roots of words related to heart, making connections among various cognates (L.4.4.b).

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “Where do English-language words come from?”

As a group, discuss that words in English can often be traced back to Greek, Latin, or German. Tell students that knowing these roots can help them understand other unfamiliar words that share the same word origins and word parts.

Ask students to take out their Vocabulary Journal and be ready to make entries to help them think about the word heart in different ways.

Display these sentences.

I lift weights, but I need to do more cardio exercise.

After his heart attack, he went to see a cardiologist.

My parents encouraged me to follow my dreams.

She showed courage when the bear came into the campground.

List the words cardio, cardiologist, encouraged, and courage

Ask: “What do the words cardio and cardiologist have in common? What do the words encouraged and courage share?”

When students identify the word parts cardio and cour, point out that these are the kinds of word parts the class discussed in the Launch.

Ask: “What do these words mean?”

Note student responses for display, or post definitions, if needed.

cardio (n.) Exercise that raises one’s heart rate. cardiologist (n.) A doctor who specializes in treating the human heart. encouraged (v.) Gave support or advice to. courage (n.) The strength to control fear in the face of a dangerous or difficult situation.

Ask: “From studying these words, what do you think cardi means? Why?”

n Heart!

n Both words are about the heart—exercise for the heart or a doctor for the heart.

Ask: “Does this word part, cardi, connect to the literal or the figurative meaning of the word heart? How do you know?”

n Literal.

n Both words are about the actual heart in the human body.

As needed, remind students of the core lesson discussion about the literal and figurative uses of the word heart Remind students that sometimes the word heart refers to the literal, physical heart in the center of your chest. Sometimes it refers to the figurative heart and might describe human love, emotions, determination, courage, or spirit.

Tell students that the word part cour comes from the Latin cor, and cor also means “heart.” Ask: “How do encouraged and courage show the figurative meaning of the word heart?”

n We might talk about people who have a big heart. These kinds of people would be encouraging people.

n I’ve heard people say “take heart” when they mean “have courage.”

Provide time for students to enter these word parts into their Vocabulary Journal.

cardi Pertaining to the heart. cardia, kardia cor Heart. cord

Multilingual learners may value the chance to share their words for heart to determine if the words in English and other languages share any word parts. For example, the French cœur, the Spanish corazón, and the Greek kardiá all show clear connections.

Organize students into seven groups, and assign each group a heart-related word: core, accord, cordial, record, cardiac, pericardium, and cardiogram. (Add additional words as needed for the size of the class.)

Students will need dictionaries or access to online dictionaries for this activity. Or, provide the word and definition on an index card for each group, and have the group complete the rest of the activity on the back of each card.

Post the following prompts:

Which word part, cardi or cor, is in your word? Define your word. Use your word in a sentence. Is your word used in a literal way or a figurative way? Groups share their responses. core n cor n “the center or most important part” n We need to get to the core of the problem. n figurative

cardiac n cardi n “dealing with the heart” n The doctor worked in the cardiac unit of the hospital. n literal accord n cor n “to be of one heart” n The group was of one accord and agreed on the goals. n figurative

pericardium n cardi n “the membrane surrounding the heart” n He had surgery to fix his damaged pericardium. n literal

cordial n cor n “friendly”

cardiogram n cardi

n “a record of the heart’s activity”

n She treats everyone in a cordial way.

n figurative

n He went to the doctor to have a cardiogram test. n literal record n cor n “remember, or write by heart”

n Please record the notes from the meeting. n figurative

For an Exit Ticket, students describe how the Latin and Greek word parts cor and cardi connect to the literal and figurative uses of the word heart.

Invite students to share their responses, and challenge them to use two of the heart words in a sentence.

n My cardiologist treats her patients in a cordial way.

Welcome (5 min.)

Sort Homework Quotations

Launch (10 min.)

Learn (50 min.)

Analyze Quotations (20 min.)

Analyze an Exemplar Essay (30 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question Wrap (5 min.)

Assign Homework

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Punctuation for Quotations (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

Reading RI.4.4

Writing W.4.2

Speaking and Listening SL.4.1

Language L.4.4.a L.4.2.b

Handout 2A: Heart Quotations

Handout 2B: Exemplar Essay

Handout 2C: Fluency Homework

Colored pencils (red, green, yellow, purple, and blue)

Sticky notes

Colored highlighters (yellow, green, blue, and purple)

Analyze quotations to explain their meaning based on the literal or figurative use of the word heart (RI.4.4, L.4.4.a).

Explain whether heart is meant to be understood in a figurative or literal way in quotations, and state the meaning of the quotations.

Identify the parts of an informative essay and the purpose each serves (W.4.2).

Compose a Quick Write to demonstrate understanding of the parts of an informative essay and the connections among the evidence organizer, Painted Essay, and Exemplar Essay.

Demonstrate how punctuation is used with quotations (L.4.2.b).

Punctuate a quotation that is in the form of a sentence.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–6

How does someone show a great heart, figuratively?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 2

Reveal: What does a deeper exploration of figurative and literal meanings reveal in heart quotations?

CRAFT QUESTION: Lesson 2

Examine: Why is each part of a Painted Essay important?

In this lesson, students analyze quotations from famous and ordinary people about the heart. Some quotations refer to the literal meaning of heart, and others refer to heart in a figurative way. Then, students examine an exemplar informative essay to determine the significance of each component of the essay. Students also discuss how an evidence organizer connects to writing an essay.

5 MIN.

For homework, students asked three people outside of class what heart means and recorded the responses as quotations.

Instruct students to share their quotations with a partner and discuss whether each quotation uses the word heart in a literal or a figurative way.

Display these questions.

Did the people we interviewed talk about the heart more literally or figuratively? Why do you think that is?

10 MIN.

Have students Think–Pair–Share about the responses to the questions.

Post the Focusing Question and Content Framing Question.

Draw a two-column chart, and label one side “Literal Heart” and the other side “Figurative Heart.” Instruct students to brainstorm key words that might indicate how the word heart is used in a quotation. Record the responses in the chart. Some possible responses are as follows:

Literal Heart Figurative Heart Beat. Blood. Exercise. Healthy. Heartbeat.

Love. Beautiful. Good. Spirit. Caring.

Explain that in today’s lesson, students work as detectives to identify clues that help explain how heart is used in many different quotations.

MIN.

G4 G4 M1 Lesson 2WIT & WISDOM®

Distribute Handout 2A. At the top of the handout are the two quotations from the previous lesson. Read aloud these quotations. Demonstrate the sign-language gestures for the letter f (open right hand with index finger held down by thumb) and the letter l (using right hand, place index finger and thumb in shape of a capital L with other fingers folded down). After you read each quotation, have students sign l or f to identify if the word heart was used literally or figuratively. Clarify any misunderstandings about the quotations.

Explain that students will work in pairs to read and understand the deeper meaning of a quotation on Handout 2A.

M1

2A WIT

Handout 2A: Heart Quotations

Directions Use these quotations to explore the difference between a literal and a figurative great heart.

“It is infinitely better to transplant a heart than to bury it to be devoured by worms.”

—Christiaan Barnard

“Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” —Confucius

Who Said It? Quotation

Helen Keller, author and teacher who overcame being both blind and deaf The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched—they must be felt with the heart.

Michael Miller, MD, F.A.C.C., Center for Preventive Cardiology at the University of Maryland Medical Center

The recommendation for a healthy heart may one day be exercise, eat right, and laugh a few times a day.

Nelson Mandela, an anti-apartheid leader and South Africa’s first black president A good head and a good heart are always a formidable combination.

Anne Frank, a young Jewish Holocaust victim who kept a diary Despite everything, believe that people are really good at heart.

NOVA website Your heart beats about 100,000 times in one day and about 35 million times in a year.

John Muir, a Scottish-American naturalist who advocated for national parks Keep close to Nature’s heart ... and break clear away, once in a while, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean.

Anonymous, a veteran trapeze artist Throw your heart over the bars and your body will follow.

Bill Nye, “The Science Guy” Your heart is a pump. It pushes blood all over your body.

Assign one quotation to each pair, allowing them to work for ten minutes. Circulate to answer any clarifying questions. Encourage students to persevere to determine the meaning of each quotation and to jot down notes from the discussions in the evidence organizer in their Response Journal. Remind students to state who said the quotation, to paraphrase an important section that reveals the literal or figurative meaning of heart, and then to elaborate and explain how the context of the sentence helps readers understand its meaning.

Pairs complete one row in the evidence organizer in their Response Journal to analyze their assigned quotation, stating who said the quotation, what it means, whether the quotation uses the word heart literally or figuratively, and listing Handout 2A as the source.

Explain that evidence organizers can be helpful when writing informative essays about a topic. The evidence organizers organize ideas about the topic or focus so that these ideas can be used to explain a focus statement.

Display the Painted Essay template, and explain that this illustration shows how we organize an informative essay.

RED GREEN YELLOW BLUE

YELLOW

The Painted Essay organizer and this Wit & Wisdom module will introduce students to different terms used when discussing informative writing. Provide additional instruction as needed to ensure that students understand this contentarea vocabulary:

Thesis/focus statement—The Painted Essay uses the word thesis to describe the introductory statement that will be explained or proved in the essay. In the instruction on informative writing throughout this module, the term focus statement describes the sentence that provides the focus for the essay.

Proof paragraph/supporting paragraph—The body paragraphs of the informative essay are proof paragraphs or supporting paragraphs.

The evidence organizers used throughout this module reinforce these contentarea terms with students.

YELLOW G4 M1 Lesson 2 WIT & WISDOM® 42

Post the Craft Question, and lead students in a Choral Reading: Why is each part of a Painted Essay important?

Distribute Handout 2B. Read aloud the entire essay on Handout 2B while students follow along on their own copies.

Handout 2B: Exemplar Essay Directions: Read the following essay.

Name Date Class

Have you ever really thought about what your coach or piano teacher means when they say, “Come on! I want to see you put your heart into it!”? The word heart is an interesting word because it can be used both literally and figuratively when we speak, when we read, or when we write. When the word is used literally, it refers to the human heart, that organ that beats as it pumps blood to all of your other body parts. When the word is used figuratively, it refers to the emotion that shows caring, effort, and involvement in other people’s lives and your own.

Sometimes, the word heart is used literally. Christiaan Barnard, a South African heart surgeon, said, “It is infinitely better to transplant a heart than to bury it to be devoured by worms.” He was saying that when you die, it is much better to donate your heart to a living person than to bury it. In this quotation, Barnard was using the word heart literally to refer to the organ in a person’s body. He wanted people to reuse their real, beating hearts to save other people’s lives.

At other times, heart is used figuratively. For example, when Confucius said, “Wherever you go, go with all your heart,” he wasn’t talking about the heart that beats inside your body. He was saying that a person has a choice of taking their heart with them when they go somewhere. For example, when a student enters a classroom on the first day of school, they can choose to do an essay or math assignment with all their heart or with very little effort invested. If Confucius was talking about the literal heart, he would have been saying something very silly, like a person had the option of taking their physical heart out of their body when they were going somewhere or doing something. In saying that we need to go somewhere with our full effort and emotional involvement, with our whole heart, Confucius was using the word heart in a figurative way.

In conclusion, the word heart can be used both literally, as in Christiaan Barnard’s quotation, and figuratively, as in Confucius’s quotation. It is up to readers to put their whole heart into the reading to determine the speaker’s intended meaning.

1 of

To personalize the Exemplar Essay for students, you may choose to write your own essay using students’ responses in the blue and yellow evidence organizer from the previous lesson. Write this essay in advance of today’s class and copy it for students. Use this in place of Handout 2B.

Display the following questions:

What is the job of the first paragraph?

What is the job of each sentence in the first paragraph?

How do the words in this heart essay accomplish these jobs?

Read the first paragraph of the Exemplar Essay again slowly, pausing after each sentence. Have students jot down notes in the margin as you lead a discussion about each sentence. Then have them color each sentence the corresponding Painted Essay color.