Gabriela Gonzalez

Reconfiguring the Missing Middle:

Desuburbanization Without Urbanization

501

USC Architecture

Casper Section

Fall 2022

Abstract

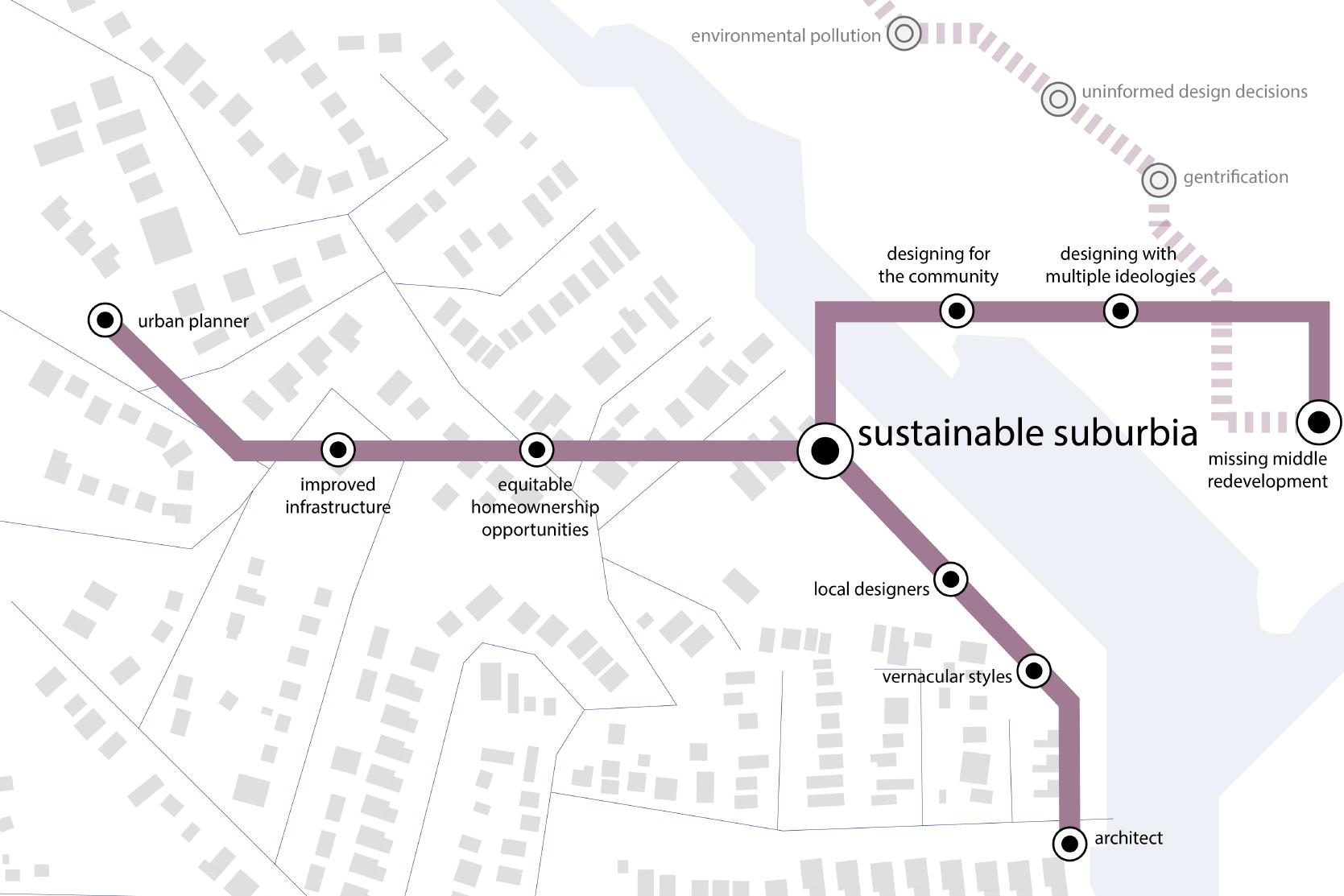

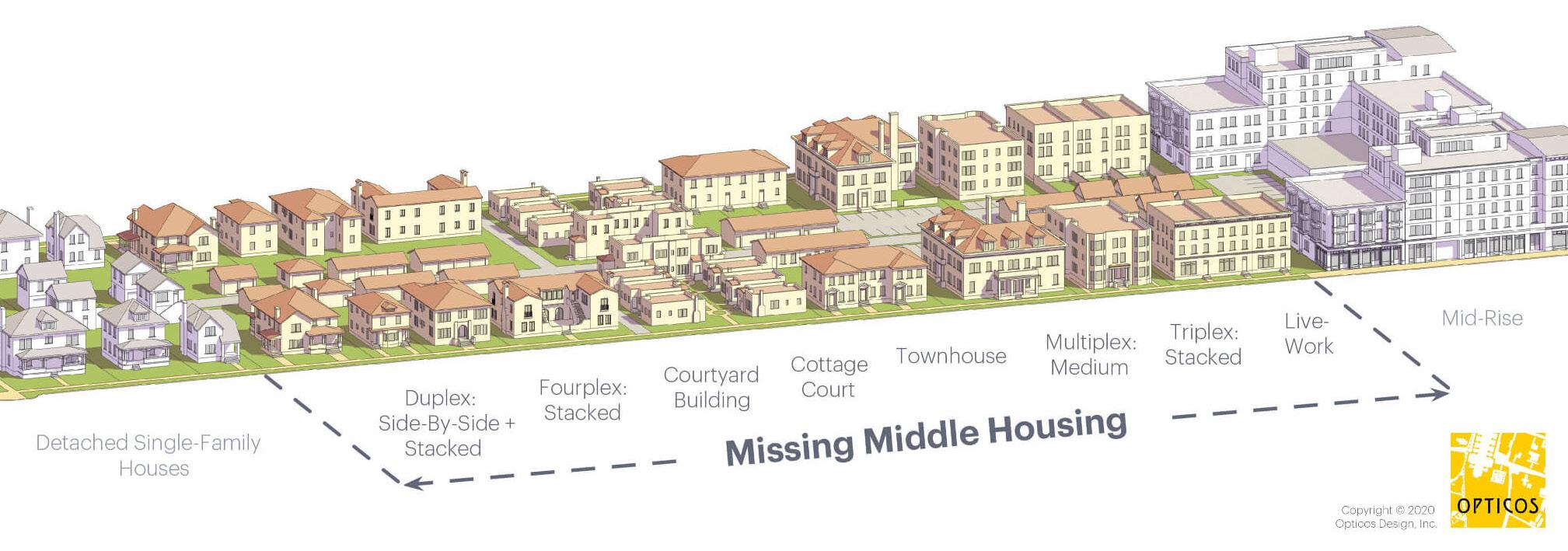

This project breaks down the current expectations for the sustainable suburb: increased affordable housing for growing populations, equitable homeownership opportunities, and a solution with a smaller carbon footprint. The “Missing Middle” model, gaining popularity in suburban towns, allows homeowners and developers to construct multi-family homes in traditionally single-family zones. Facing backlash from suburban-loving homeowners afraid to lose the neighborhood spirit while receiving support from those who cannot afford to live in the city, the plan’s effects can be controversial. Analyzing the current “Missing Middle” model that city planners are increasingly using, and creating a comparative study to projects of similar scale and context, this paper attempts to consolidate the ideas into a comprehensible guide for the architect to design with regard to economic, social, and environmental sustainability to better serve their communities. The result is a city with affordable housing for an aging population and those of varying tax brackets, a range of property sizes and values, and limiting developers to seize the market and gentrify communities. To better understand the Missing Middle results, existing obstacles in suburban development will be identified and sustainable approaches to redesign will be provided.

Keywords: suburb, urban regeneration, desuburbinize

Note: I grew up in the Halls Hill neighborhood of northern Arlington, Virginia. My family has lived in the area for over 22 years and I have experienced the division that the “Missing Middle” plan has recently caused in the community.

Introduction

The suburb- “a town or other area where people live in houses near a larger city”1 or “an outlying part of a city or town”2 is up to interpretation. The definition of a suburb lacks the necessary parameters for a consistent description and, subsequently, characteristics of a suburb. The broad and varying specifications of what constitutes a suburb can influence a researcher’s findings,3 providing an obstacle to city planning. A suburb is generally considered a place with low-density and single-family homes surrounding a large metropolitan area. However, there is no set definition that the US Census provides for housing studies, complicating studies for city designers and planners, leading to the improper selection of improper urbanization planning in American cities. For this essay, a suburb will follow the “typology” definition, which examines the population density, housing density and age, and tract properties, also recognized as the “suburban feel.”4 Based on the work of Thomas Cooke and Sarah Marchant, this definition was coined while researching the “changing geographical distribution of high-poverty neighbourhoods... both between and within American metropolitan areas between 1990 and 2000.”3 Selecting a particular definition to follow prior to arguing for the urbanization of a particular area helps identify target areas for city planners, such as population distribution and needs, as well as frame expectations when designing for change. The most significant generator of suburban sprawl, Euclidean zoning, deliberately separates building zones by use and building type. This zoning strategy requires a considerable amount of land resources and creates a separation that requires more tangible resources to maintain.5 Named after a Supreme Court case6 and now used as precedent throughout the United States, Euclidean zoning is being challenged by residents of suburban areas like Euclid, Ohio, seeking to challenge the authority in place through existing zoning and redesign their communities. The environmental, economic, and social costs are challenging to overcome,

1 The Britannica Dictionary, “Suburb.”

2 Merriam Webster, “Suburb.”

3 Airgood-Obrycki and Rieger, “Implications of Different Suburban Definitions,” 6.

4 Cooke and Marchant, “Changing Intrametropolitan Location,” 1971–1989.

5 Hall, “Divide and sprawl,” 916.

6 Durchslag, “Village of Euclid V. Ambler Realty Co,” 665.

given the legal obstacles created when a Euclidian zoning plan takes effect. Regardless of the difficulty of rezoning and the tactical undoing of Euclidian zoning, some cities in the United States and abroad are actively planning to do so in the name of sustainability. The city of Greater Adelaide in Australia1 has drafted a sustainable redevelopment guide for city planners, developers, and designers. This structured plan outlines goals for sustainable change in current public infrastructure, future building code amendments, procedural expectations, and result documentation. Sustainable redevelopment opposing Euclidian zoning is perceived as essential for resilience to climate change and improving livability for the community.

A metropolitan suburb in Washington, D.C., is a recent example of the fight against Euclidean zoning. Most notable for having national attractions such as the Pentagon and the National Cemetery, Arlington, VA, has recently been making headlines for being selected as Amazon’s winning bid for HQ2, the second headquarters of the e-commerce company. With Amazon’s corporate headquarters creating 50,000 new jobs in the area, the suburban county is racing to provide more housing opportunities where restrictions limit construction to only single-detached housing. In 2020, Arlington County Board began a “Missing Middle Housing Study” to “increase housing supply and diversify housing types” in response to the predicted population boom following Amazon’s HQ2 construction. As the first LEED-certified community in the United States,3 Arlington, VA, is trying to ensure a sustainable lifestyle for its residents. The rare title was given to the county in 2017, following its “suburban boom,” or a population surge in a single-family neighborhood. Arlington’s landscape consists primarily of single-family detached homes, has a population surpassing 200,000, and is only 26 square miles.4 Despite the population density of 9,179 people per square mile, it still falls under the typology definition of a suburb. Suburbia holds negative connotations: excessive use of resources, “cookie cutter houses,” and car dependency are a few of the issues that come to mind regarding the sustainability of normative housing. With criticism, there have been attempts to redesign the suburb by retrofitting commercial areas for community spaces, increasing walkability, and, most importantly, increasing building density.

The premise of the “Missing Middle” zoning plan in the continental United States is to create more equitable homeownership opportunities and increased housing solutions for growing populations by allowing the construction of multi-family homes in traditionally singlefamily home zones. Similar rezoning plans include Chicago’s Cabrini Green5 and Washington D.C.’s Columbia Heights.6 The Arlington County Board has been pushing this plan during city council meetings for over two years, unable to pass the ordinances due to heavy resident opposition. Initially introduced as a proposal to amend zoning ordinances in Arlington, Virginia, the zoning plan addressed expected housing needs following the construction of Amazon’s

1 Government of South Australia, “The 30 Year Plan for Greater Adelaide,” 14.

2 DeVoe, “Amazon Unveils Plans for Futuristic, Nature-Inspired Phase 2 of HQ2.”

3 United States Census Beureau, “ 2020 QuickFacts.”

4 Komar, “Arlington Earns Nation’s First LEED.”

5 Miller, “The Struggle Over Redevelopment At Cabrini-Green.”

6 Hyra, “Race, class, and politics in the Cappuccino City,” 8.

second headquarters, HQ2, in the area. The goals presented are to create more equitable homeownership opportunities and increased housing for growing populations by allowing the construction of multi-family homes in traditionally single-family home zones.1 This paper aims to analyze Arlington County’s proposed “Missing Middle” plan and compare so to other widely-accepted suburban planning methods designed to counteract the unsustainable effects of the outdated Euclidean zoning. The subsequent design project will ultimately consolidate the ideas into a comprehensible guide for the architect and craft a fulfilling response to new city planning rules and guidelines and better serve their communities.

Designing for Communities

Designers should respond to government-decided guidelines by creating a project that favors the existing neighborhood, contributes to the welfare of the community’s residents, and increases neighborly relationships. “Clumsy Cities,”2, a more modern attempt at urban planning developed by Hartmann and Schmitt of the University of Vienna, combines the broader planning practices from urbanist Jane Jacobs3 and sociocultural theorist Mary Douglas. Clumsy Cities by Design are amalgams of the successful pieces of postEuclidian urban planning theories for diversity, highlighting the importance of pleasing residents, providing liberty to designers, and preventing gentrification in just design. Clumsy Cities acknowledge the importance of Jacobs’ work in pursuing diversity in city planning and creating communities in the urban landscape utilizing multiple ideologies. Design is a shared responsibility within the community. Urban planning is a message delivered by a planning authority to the community through the design responsibility lies with the architects, who can design something for the community, “the ethical dimension in practice cannot be separated from the ‘physical’ dimension of the city (i.e., urban design, technology, architecture, and related fields).”4 Property owners have delegated the responsibility of city planning to the county board through the electoral system, who then decide how to amend ordinances that they believe are best for the community. The approved legislation becomes guidelines for architects and urban designers to follow with a client’s opinion. Legislation is not equivalent to design decisions. The designer should use the city code and guidelines to supplement their design process, placing the community’s ethical and moral values first.

2 Schmitt and Hartmann, “Clumsy City by Design,” 42-50.

3 Kidder, “The Urbanist Ethics of Jane Jacobs,” 254.

4 Perry, “We didn’t have any other place to live: Residential Patterns in Segregated Arlington County, Virginia,” 415.

Similarly structured is the idea of the three pillars of sustainability: economic, environmental, or social, with Euclidean zoning falling short in all three categories. The application of the “three pillars of sustainability” should be worked into the “Missing Middle” plan to optimize results for the betterment of the community: economic sustainability regarding the cost-benefit analysis of maintaining the community as well as affordability, environmental sustainability about reduction of resource consumption and increasing green space, and social sustainability relating to advocating for social justice and preventing gentrification. Folding in differing concerns regarding the different branches of sustainability will create a more diverse plan for the community. Like community members, the three pillars of sustainability are co-dependent, only functional when the results are not detrimental to each other. Cross-comparing sustainable relationships leave us with three relationships applicable to urban planning: socioeconomic, socio-environmental, and enviro-economic.

Planning is a practice that generates revenue for the county government; thus, changing single-family home zones to multi-family home zones allows the local government to increase property tax revenue. The Missing Middle plan would successfully increase funding for public infrastructure maintenance costs such as winter road salting, storm waste clean-ups, and emergency sewage repair. This strategy for increasing funding is economically sustainable, ensuring that an inevitable increase in residents will contribute to county maintenance costs. However, on the socioeconomic level, the proposed Missing Middle planning practices will generate revenue indirectly derived from the displacement of others. Designers can break this unjust cycle by using their talent to reinterpret guidelines in favor of the existing community. The neighborhoods of Shaw, U Street, and Columbia Heights are historically black and a part of Washington, D.C. that has suffered an atypical form of gentrification caused by the expansion of the commercialized redevelopment of Downtown D.C. inviting an affluent population seeking a diverse and “authentically black experience” in the city and pushing out the black population.1 This neighborhood’s experience is particularly relevant to Arlington, VA, given the proximity and the similar historical background.

Arlington is no stranger to gentrification; the remains of a wall that divided the Halls Hill neighborhood from the adjacent segregated community still stand today. This neighborhood was one of two segregated neighborhoods in Arlington before 1970, with 84% of the population surveyed as black.1 Today, that number has decreased to an estimated 23%.2 Longtime homeowners frequently receive offers from housing developers, an attempt to demolish the older home and construct one twice its size in its place for a hefty profit. In this community, rezoning means opening up the market to foreign developers who threaten the affordability of living in a neighborhood where residents were born and raised. This “laissez-faire”or libertarian

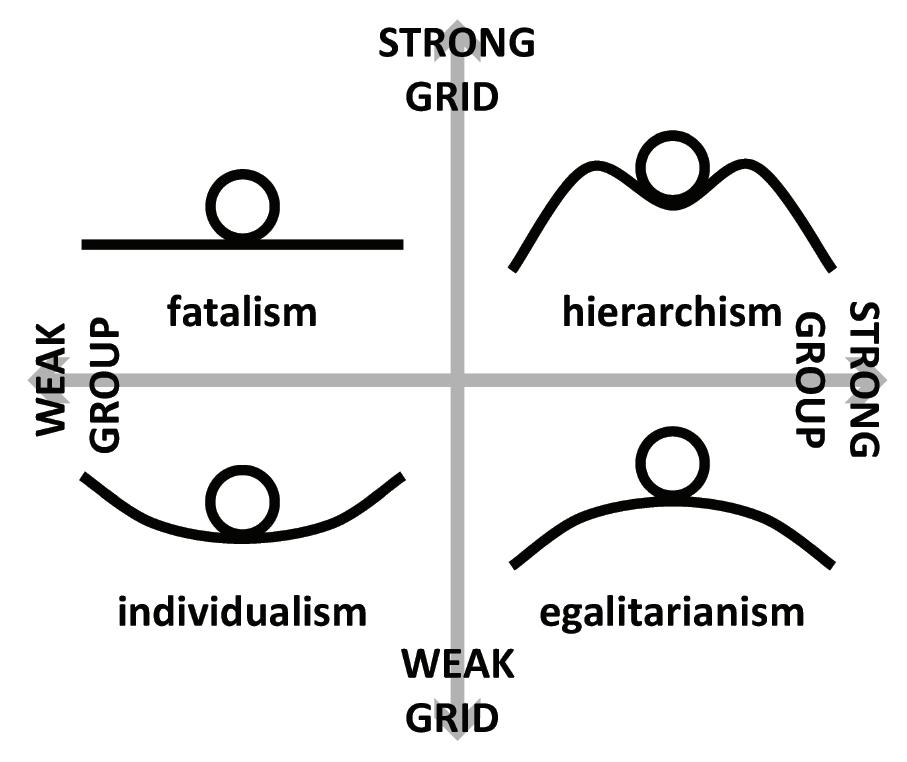

The rationalities for Cultural Theory (Source: Schmitt and Hartmann, 2016)

method of city planning is highlighted in Douglas’ Cultural Theory diagram as “individualism,” part of the weakest part of the group grid.1 This is because there is a lack of collaboration, making the method impractical for city planning and possibly detrimental to the community. If local governments were to enact rezoning without proper protections for current residents, they would leave the market open to developers and invite gentrification into communities like Halls Hill.

Designing for the Environment

Suppose the urban planner needs to include proper protections for current residents at risk of being displaced by urban renewal. In that case, the task of designing for the community falls on to the architect. An architect’s design decision affects the homeowner-client and the community surrounding the construction. For example, a high-tech facade system might feel out of place and invite other architectural styles that can increase property prices and give incentive to landlords to raise rental rates; not following the previous building set back requirements could create a street section that is uninviting or uncomfortable for pedestrian mobility; and an oversized building can create uncomfortable living conditions for neighbors. This previously mentioned concept of shared responsibility in design, a shared sentiment by Clumsy Cities, is fundamental to sustainability. A designer’s response, if uninformed, can have unfavorable impacts on the community and affect the other two pillars of sustainability. Environmental sustainability, the larger encompassing group of the three pillars, can benefit from the Missing Middle plan, as it is supposed to increase population growth while maintaining the current green spaces on private property. This proposed well-being to the community has raised concerns by local organizations such as “Arlingtonians for our Sustainable Future,” a group dedicated to sustainable development for the Northern Virginia suburb that identifies lacking proper infrastructure for population growth. Infrastructure, a physical obstacle, is a visible pollutant in our communities, creating car exhaust that affects the air quality, constructing nonpermeable surfaces that increase stormwater runoff, and overflowing sewage waste contaminating local streams. Amending the current Missing Middle plan without adding stipulations like LEED energy requirements and protections for mature trees reveals greenwashing by the local government planning commission. Not including LEED-like design guidelines can lead to overconsumption of non-renewable energy sources. Removing mature trees can result in tree canopy loss and

leave wildlife without homes. These two stipulations are the bare minimum, a better, more descriptive set of legislative guidelines is the California Building Standards Code, Title 24 of the California Code of Regulations (Title 24)2

Highlights from the state of California’s building standards code include amendments to the California Electrical Code for “energy-efficiency based electrical requirements in the California Energy Code” as well as “California Green Building Standards,” 5 pages of amendments to measures to be taken by architects and planning commissions regarding housing and community development. The Commonwealth of Virginia lacks building code specifications similar to California’s. The responsibility of consciously designing for the environment falls on the architects and city planners without any expectation to do so. If Arlington, Virginia, could adopt a set of building requirements like Title 24 at the local government level, or at least include them in the requirements for Missing Middle redevelopment, there would be less risk of environmentally unsustainable practices occurring in the upzoning process.

The most remarkable similarity between intersectional sustainability and Davis’ cultural theory is the creation of solid relationships amongst differing ideas. For a sustainable suburb, the people’s needs (socioeconomic) impact the resulting environmental differences. For a diverse suburb, a group willing to govern social justice (egalitarianism and hierarchism) will prove results approved by most community members. Conceptually reinterpreting the proposed Missing Middle plan in Arlington, Virginia, benefits the architect and the community.

Conclusion

In her analysis of urbanist Jane Jacob’s1 work, Katherine King highlights the possible damages caused by redevelopment and instead encourages neighborhood reinvestment as “disinvestment in a community (to clear the way for extensive redevelopment of land) rather than fostering the local reallocation of buildings and land uses would also break up existing social relationships.”2 There is no correct methodology for city planning, demonstrated by the variations in Missing Middle models across the country. Referencing Cabrini-Green and Columbia Heights, these plans faced issues affecting long-time residents and the pre-existing community specific to the local environment. Amalgisms of planning theories, whether specific to city-planning or broad social theories, can strengthen the plan for urban development at the suburban level. Socially accepted concepts, like the three sustainability pillars, ensure acknowledgment of more than physical planning. Theories traditionally developed for other fields like anthropology and sociology, like Cultural Theory, can bring light to new ideas in planning development. Referencing existing guidelines for the built environment, like Building Codes from other states, ensures the redevelopment is forward-thinking and surpasses current expectations set in the United States. An amalgam of ideas advocates for community building, promoting diversity in not only the population but ideas from the beginning of the planning process. Diversity in thought renders diversity in planning, ultimately what is needed to satisfy community desires and effectively plan for the suburb’s future.