Air & Space

KC-390 MILLENNIUM

From the outset, the KC-390 Millennium was designed to set a new benchmark in the medium-size military transporter segment. Developed with support from the Brazilian Air Force (FAB) and Brazilian Government, the largest and most complex aircraft ever built in the southern hemisphere has gone through a rigorous and challenging testing program, including 3,500 prototype flight test hours and close to 85,000 hours of lab tests. In March 2023, it received the coveted Full Operational Capability certification from the Brazilian Military Certification Authority (IFI – Institute of Industrial Development and Coordination), with the platform meeting or exceeding all requirements. This seal of approval, which is extremely difficult to attain, confirms the KC-390 Millennium is ready for full operational duties in all missions and showcases to the world its class-leading reliability, flexibility and performance.

#C390UnbeatableCombination c390foc.com/en/

Editor Simon Michell

Project Manager Group Captain Paul Sanger-Davies, Director of Defence Studies (RAF)

Editorial Director Barry Davies

Designer Ross Ellis

Managing Director Andrew Howard

Printed by Pensord

Front cover image: Cpl Hazel Reader (RAF)

Published by Chantry House, Suite 10a High Street, Billericay, Essex CM12 9BQ

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 1277 655100

On behalf of the Royal Air Force Ministry of Defence Main Building, Whitehall, London SW1A 2HB, UK www.raf.mod.uk

© 2023. The entire contents of this publication are protected by copyright. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. The views and opinions expressed by independent authors and contributors in this publication are provided in the writers’ personal capacities and are their sole responsibility. Their publication does not imply that they represent the views or opinions of the Royal Air Force or Global Media Partners and must neither be regarded as constituting advice on any matter whatsoever, nor be interpreted as such. The reproduction of advertisements in this publication does not in any way imply endorsement by the Royal Air Force or Global Media Partners of products or services referred to therein.

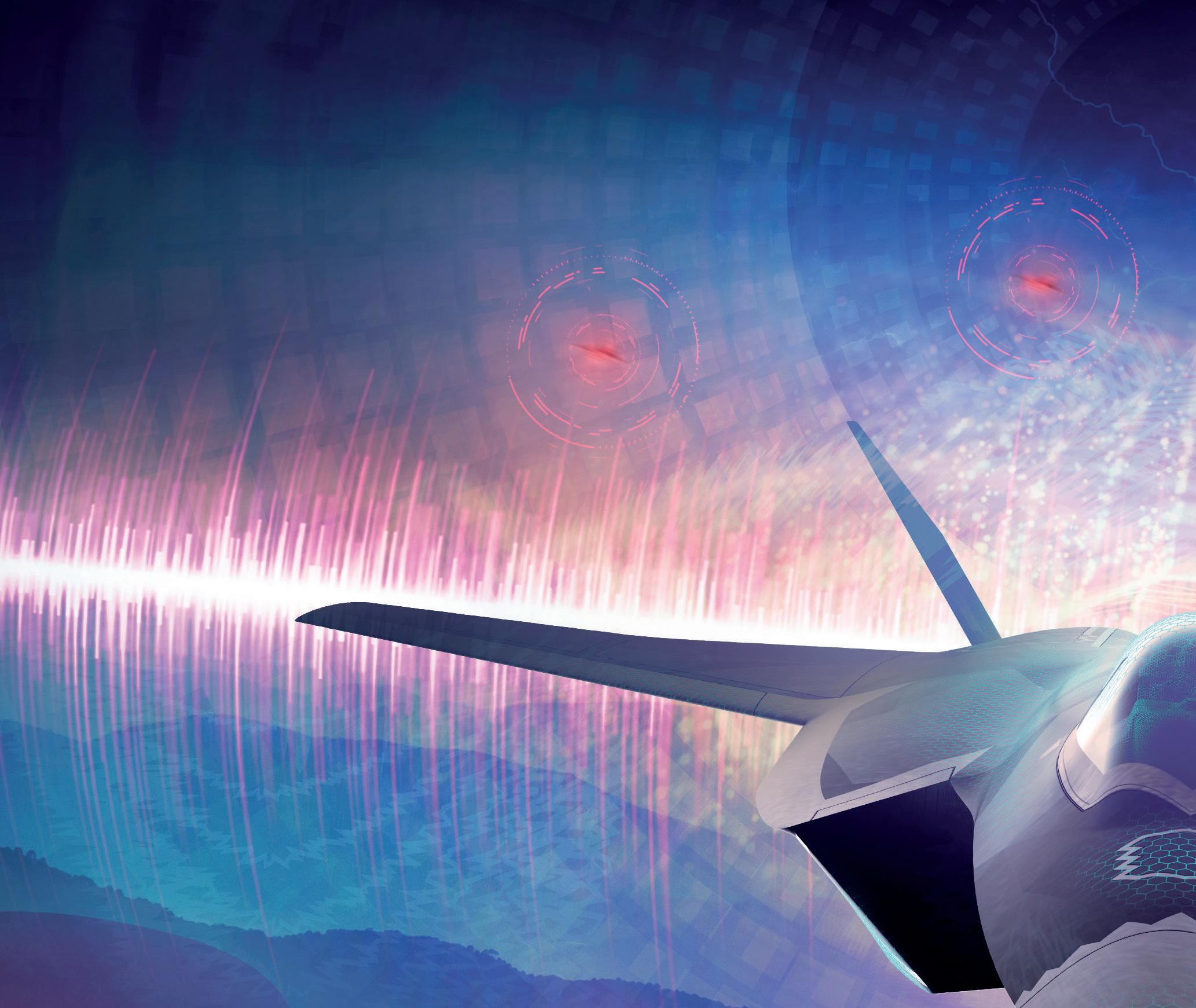

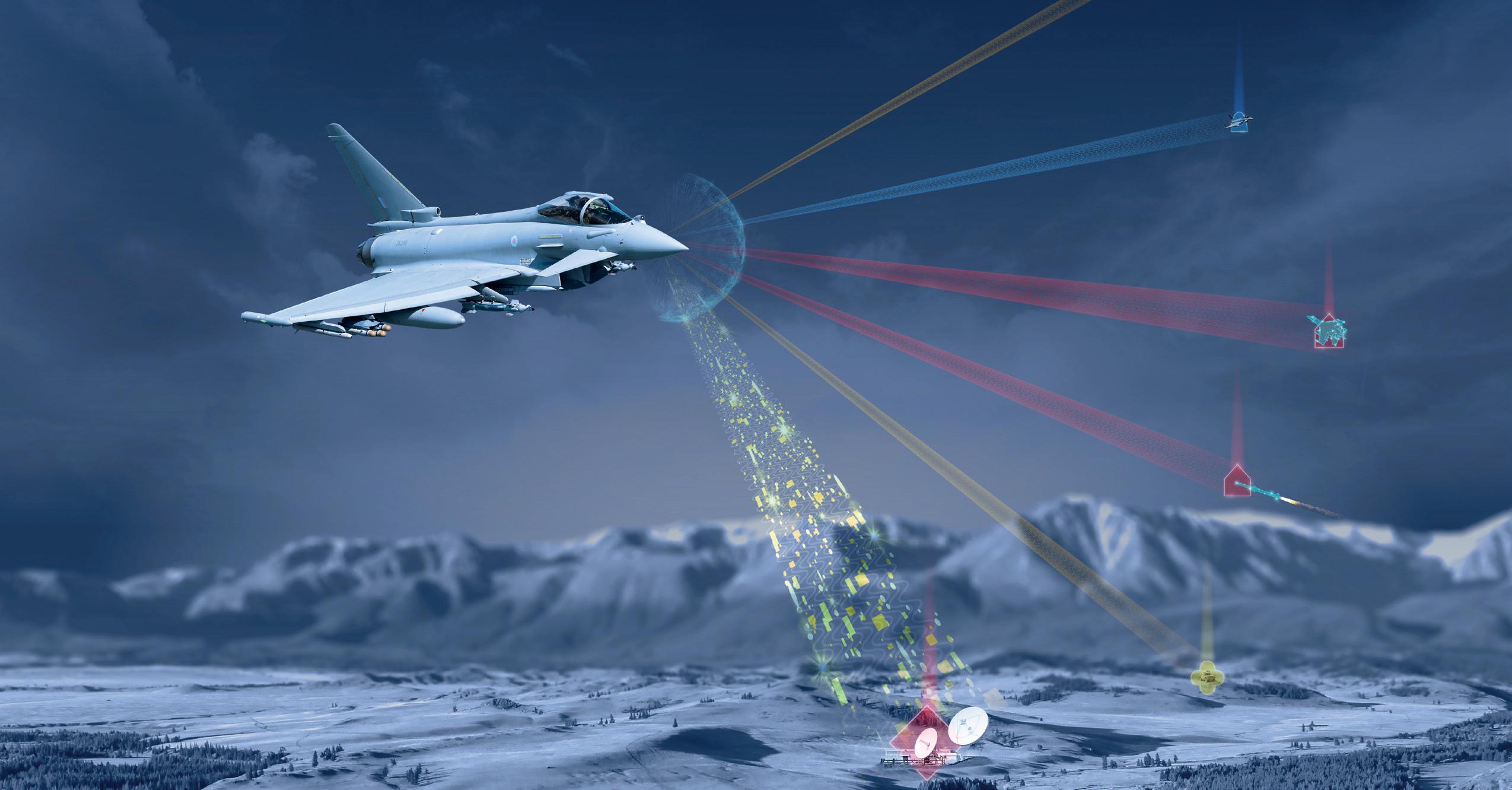

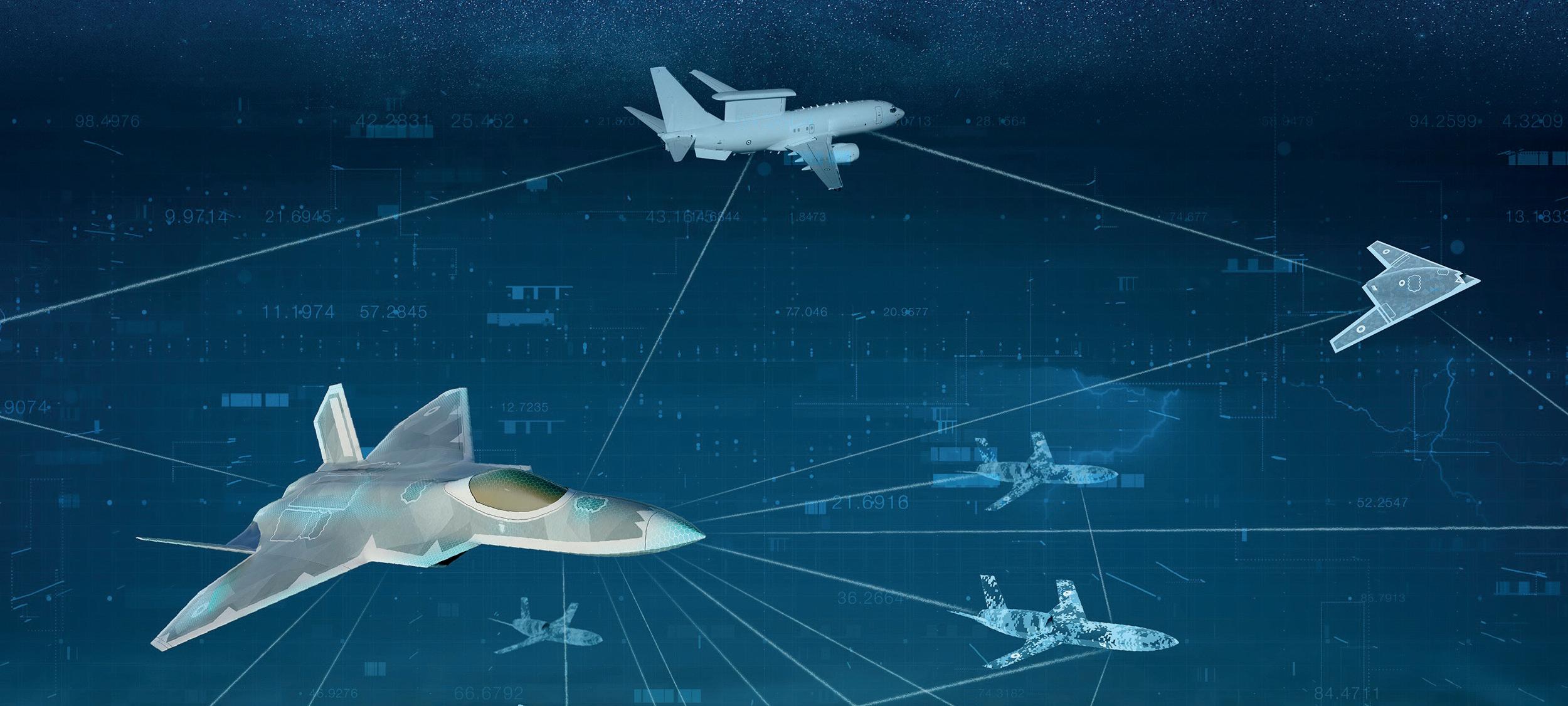

As a founding member of Tempest, Leonardo UK is helping to secure the RAF’s combat air advantage for future decades. In the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), Leonardo is the UK lead for the ISANKE (integrated sensing and non-kinetic effects) and ICS (integrated communications system) domain, meaning that Leonardo’s advanced electronics will be at the core of the future system’s combat capabilities.

Building on 100 years of heritage in advanced design and manufacturing in the UK, Leonardo’s work on this iconic project will galvanise future generations and contribute to the nation’s prosperity.

Chief Marshal Sir Richard Knighton

32 Lessons from Ukraine

Air Marshal (Retd) Greg Bagwell, President, Air & Space Power Association

33 Space capability integration: integrating with allies and partners

Air Commodore Adam Bone, Head of Space Operations, Planning and Training at UK Space Command, explains what needs to be done to deliver the requisite levels of integration

37 Providing advanced modern capabilities

Kevin Craven, Chief Executive O cer, ADS Group

38 Evolving global multi-domain operations

Northrop Grumman UK’s Paul Tremelling explains how global multi-domain operations will transform the speed with which decision-quality information is relayed to the e ector of choice for optimum e ect

40 ACE – Agile Combat Employment, delivered globally

Group Captain Jason Payne, No 11 Group’s Deputy Assistant Chief of Sta , discusses the development of the ACE concept, designed to enable the RAF to operate from a greater number of locations

Air Marshal Johnny Stringer, Deputy Commander of Allied Air Command at Ramstein Airbase, Germany, reveals how his command ensures the security of NATO territory

44 RAF strategic support to Ukraine and lessons learnt

Air Vice-Marshal Phil Robinson, Air O cer Commanding No 11 Group, on how UK support to Ukraine will inform the development of future RAF capabilities and doctrine

47 Global Enablement and future Force Protection

Air O cer Global Enablement, Air Commodore Jamie Thompson, explains how the Global Enablement Organisation will deliver enhanced security and capability to the UK

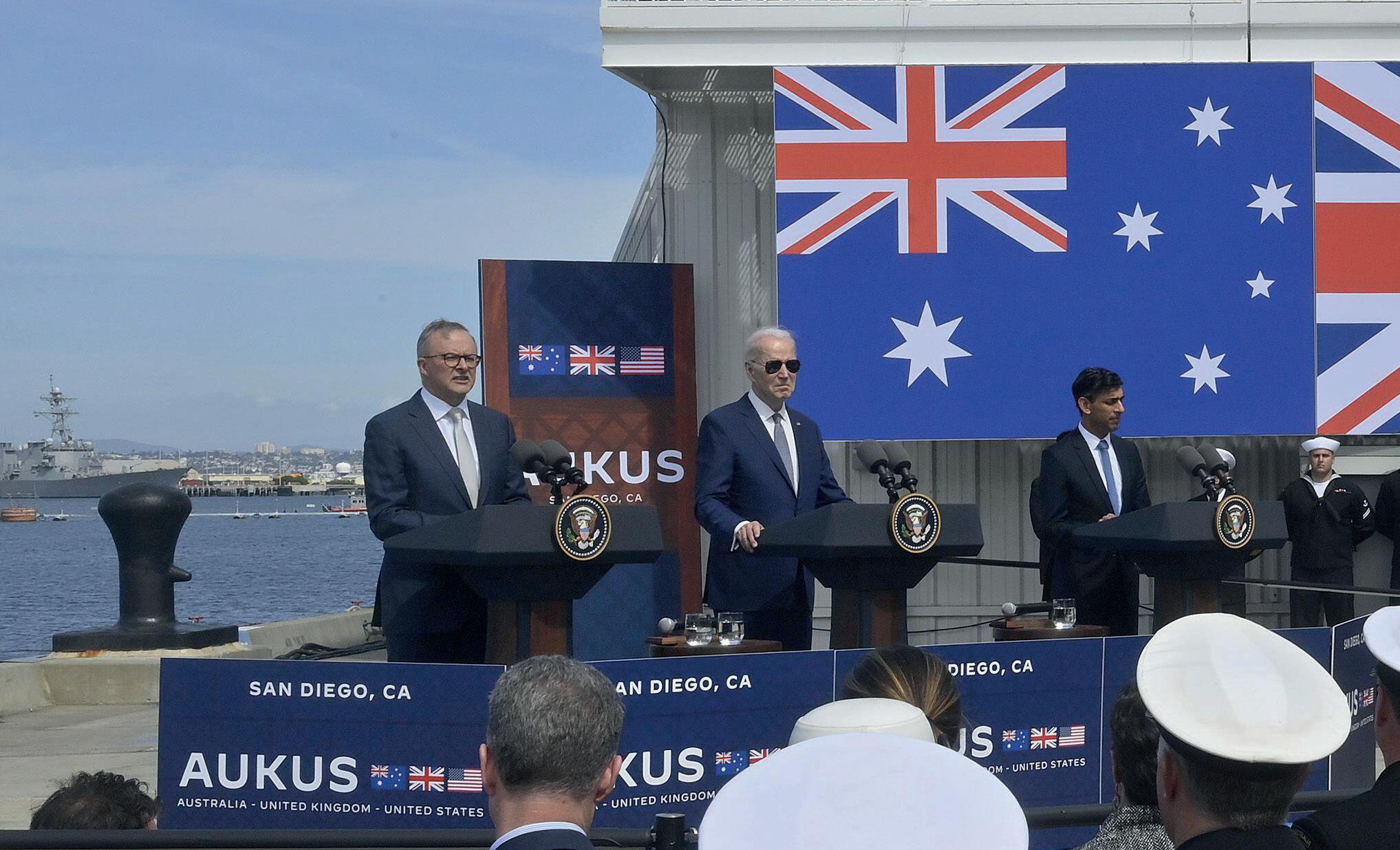

49 AUKUS strategic partnership

Air Vice-Marshal Simon Edwards, Assistant Chief of the Air Sta (Strategy), outlines the bene ts of the Trilateral Security Pact between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, which incorporates collaboration across a range of capability areas

52 Number 1 Group transformation

Air Vice-Marshal Mark Flewin explains how Number 1 Group is evolving to ensure that it can continue to deliver decisive air power across all its roles

55 RAF Lossiemouth: enhancing strategic importance

The RAF’s E-7A Programme Manager, Wing Commander Ben Fletcher, reveals how the arrival in 2024 of three new E-7A Wedgetail airborne early warning aircraft will enhance RAF Lossiemouth’s already signi cant strategic importance to UK defence

57 Projecting air and space power in the 21st century

Peter Round, President, Royal Aeronautical Society

58

Introducing Protector

Group Captain Rob Barrett, the ISTAR Force Headquarters Deputy Head of Capability, highlights how the MQ-9B Protector RG Mk 1 will complement the capabilities of the ISTAR Force from next year, when it is due to enter service

62

GLOBAL STRATEGIC PARTNER PERSPECTIVE

Lieutenant General Luca Goretti

Chief of Sta of the Italian Air Force

63 Typhoon radar capability upgrade

Air Commodore Ian ‘Cab’ Townsend, Assistant Chief of the Air Sta Capability Delivery Combat Air, outlines the outstanding bene ts of the Typhoon’s next radar system – ECRS2

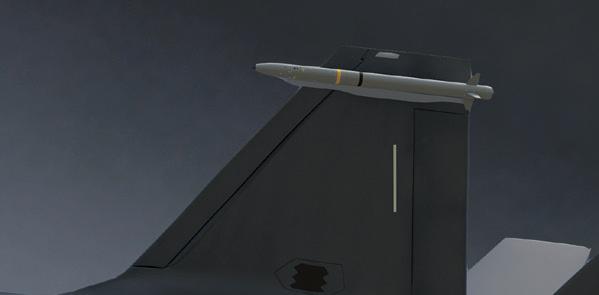

67 F-35 capability growth

Air Commdore Howard Edwards, the newly appointed Combat Air Force Commander, describes how the RAF is enhancing the combat capability of the F-35B Lightning

70 GLOBAL STRATEGIC PARTNER PERSPECTIVE General Shunji Izutsu

Previous Chief of Sta of Japan Air Self-Defense Force

71 Delivering mission readiness through training

BAE Systems’ Lucy Walton explains how the company is leading the development of technologies that will train the military forces of tomorrow

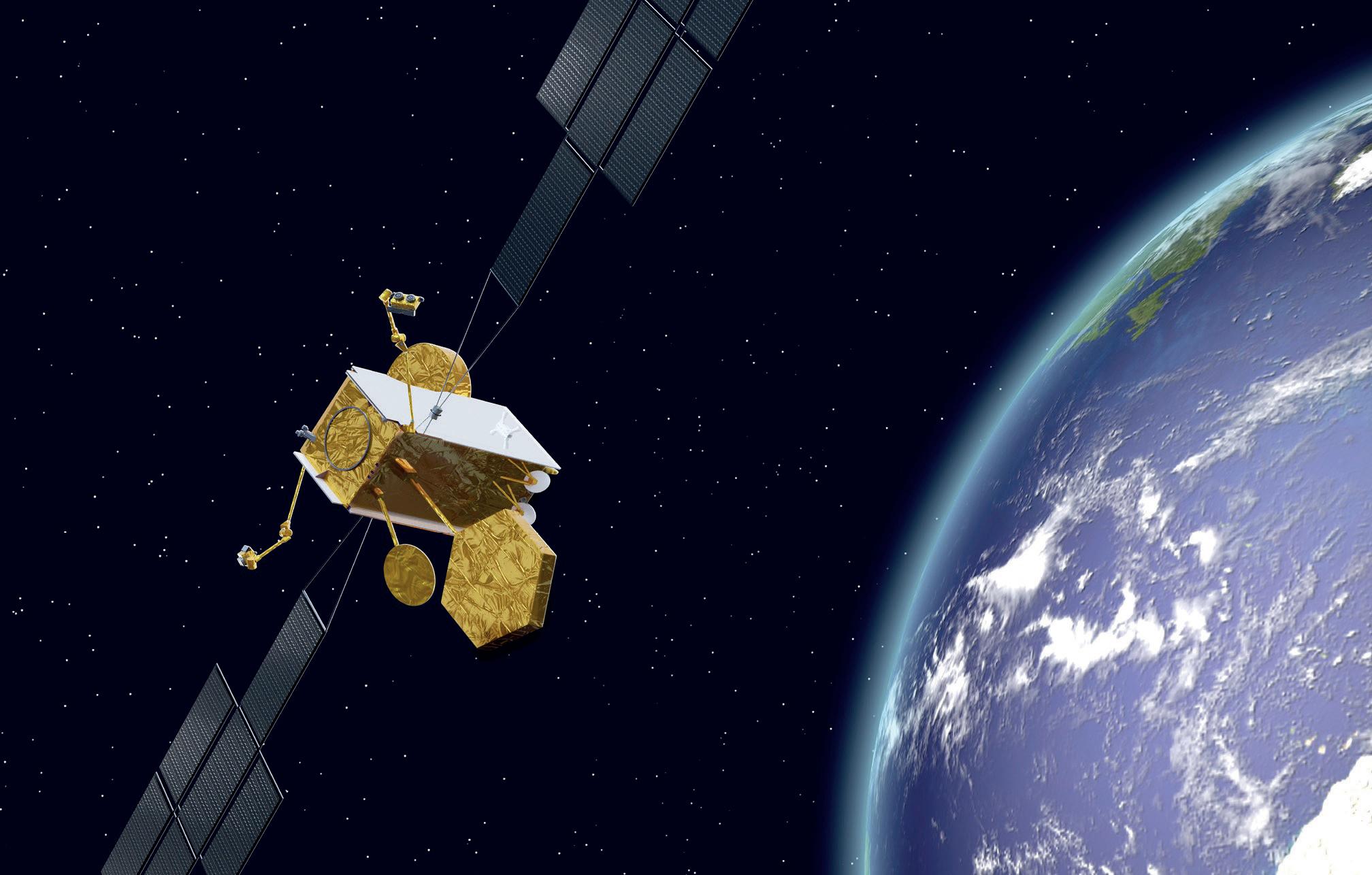

74 Driving more resilient and secure satellite communications

Hisham Awad, new Managing Director of Viasat UK, explains why an agile, adaptable development process is needed to procure satellite communication systems

76 The evolution of UK Space Command

Air Vice-Marshal Paul Godfrey, Commander of UK Space Command, talks about the Command’s expansion since it was established in April 2021

79 Strategic cybersecurity: partnership by default and the importance of a Whole Force paradigm

Air Vice-Marshal Tim Neal-Hopes, Director of Cyber Intelligence and Information Integration (DCI3), highlights how Russia’s cyber onslaught on Ukraine and its allies emphasises the need for a partnership and Whole Force approach to cyber operations

81 RAF technology and innovation strategy

Cecil Buchanan, the RAF’s Chief Technology O cer and Head of Science at the Rapid Capabilities O ce, explains his technological vision

84

Innovative by design and innovative by instinct

Wing Commander Matt Morris reveals how the RAF is embedding its innovation mindset to maintain its operational edge

87 Team Tempest – developing next generation capabilities

Interviewed prior to becoming Chief of the Air Sta , Air Marshal Sir Richard Knighton examines what the new trilateral partnership between the UK, Japan and Italy to develop the UK’s Tempest ghter aircraft means to the UK Defence community

90 GCAP – reducing cognitive burden

MBDA UK’s Chris Allard reveals how arti cial intelligence and machine learning are being used to reduce the cognitive burden of future pilots

92

AI-enabled air command and control and information management

Air Vice-Marshal Linc Taylor, Chief of Sta , Capability, and Chris Platt, Arti cial Intelligence (AI)

Experimentation Programme Leader at the Rapid Capabilities O ce, discuss progress towards the RAF’s future AI-enabled Command and Control capability

94 Gaining and maintaining digital and data dominance

The RAF’s rst Chief Digital Information O cer, Dr Arif Mustafa, talks about what his job entails and how he will enhance RAF capabilities

Creating the Combat Cloud –Nexus and Raven

Group Captain Ian Bews and Wing Commander Dave Collins reveal how two game-changing components of the UK’s Combat Cloud were developed

Cohering credible counter-UAS capabilities

Group Captain Gary Darby, Head of the Joint Counter-UAS O ce (JCO), describes how his team is developing counter-drone capabilities

Changing with the generations

Air Vice-Marshal Maria Byford, Chief of Sta Personnel, outlines how the RAF is driving forward attraction, recruitment and retention initiatives

Introducing DCDC

Air Vice-Marshal Fin Monahan, Director of the Developments, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC) at Shrivenham, outlines the role that the Centre plays in evolving UK Defence capability

105 Enhancing UKMFTS capabilities and the wider training pipeline

Group Captain Ryan S Morris, Assistant Director Plans at the Directorate of Flying Training, o ers up a reassuring account of the current state of UK military ying training and a compelling insight into its future

108 Cyber Reserve

Wing Commander Martin Smith of the Cyber Reserve Force explains how the RAF is tackling the issue of attracting su cient people to assure data and achieve information advantage

110

Group Captain Paul Sanger-Davies considers how the RAF can best develop its cognitive capabilities in order to outthink and out ght potential enemies

112

The Commandant of the Tedder Academy of Leadership, Group Captain Emma Keith, explains how she ensures that leadership and command education is accessible to everyone across the Whole Force

116 The next o set strategy

Honourable Group Captain Kevin Billings from 601 Squadron explains why it is the right time to double down on the RAF’s commitment to addressing climate change

has con rmed the criticality of maintaining world-class air and space capabilities, to deter our adversaries and, if required, to defeat them. The Integrated Review Refresh highlighted the epoch-de ning challenges we are facing, with Russia trying to rede ne the international order through force, and China challenging us using constant competition to create a new world order aligned with its own grand design.

We must have the means to defend what is ours and protect what we value. Our air and space capabilities are central to the UK’s ability to do this, providing the agility, precision and lethality we need. Quick Reaction Alert forms the backbone of the United Kingdom’s Air Defence, in safeguarding the security of our airspace. We are investing in our infrastructure to further enhance our operational resilience. Our Homeland Defence is being strengthened through the development of space-based

capabilities and airborne early warning and control aircraft. And our P-8 Poseidons are integrating seamlessly with the Royal Navy to ensure maritime security, both above and below the surface.

The proliferation of long-range and high-speed missiles, combined with the rising threat from a spectrum of drones, also means that we will have to integrate our sensors and kinetic capabilities seamlessly to protect and defend our Critical National Infrastructure.

We must prepare to ght for control of the air, and the electromagnetic spectrum, to ensure that our forces, and those of our allies, retain their freedom to operate e ectively.

We are continuing to provide our Ukrainian allies with the precision capabilities they need to turn the tide of Russian aggression and restore their territorial integrity. The airbridge we have established is maintaining a steady stream of lethal and non-lethal aid, while also bringing Ukrainian recruits to the UK to be trained by our Armed Forces, before returning to

ght for their freedom. And we are training Ukrainian pilots to use the NATO aircraft that will be critical in guaranteeing their longer-term security and protection from attack.

The indivisibility of defence and security across the EuroAtlantic and Indo-Paci c Regions is highlighted by our international partnerships. Our AUKUS Trilateral Security Pact with Australia and the United States is facilitating cooperation across a spectrum of emerging technologies, including the development of future capabilities.

The Global Combat Air Programme with Italy and Japan is creating a world-leading sixth-generation combat air system to protect our security and prosperity in the decades ahead. And such relationships will open opportunities for further international collaboration. Our Joint Typhoon Squadron with Qatar serves as an example of how we can build shared capability through cooperation and integration with other leading air forces.

Our F-35 deployments are providing fth-generation air power to NATO and Joint Expeditionary Force partners, focused upon the collective defence of the North and High North. We are already planning the return of our Carrier Strike Group to the IndoPaci c. And we demonstrated the agility and responsiveness of our rapid global mobility in Sudan recently, from where thousands of British Nationals were airlifted to safety at very short notice.

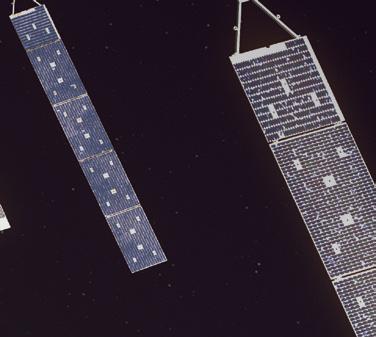

We are implementing the lessons from Ukraine, noting that pervasive commercial low-earth communication satellites have been a critical capability in the ght for freedom. As a result, we are focusing on increasing collection and enhancing coherence through the Space Operations Centre. We are playing a leading role in the Combined Space Operations Alliance, with our FiveEyes partners, plus France and Germany. And our agreements with Australia, Japan and the Republic of Korea are increasing

vital cooperation with like-minded space-faring nations. The accelerated delivery of our National Space Operations Centre is providing important integration across Government and with Industry, and we are looking into the space skills of our future workforce with the development of the UK Space Academy.

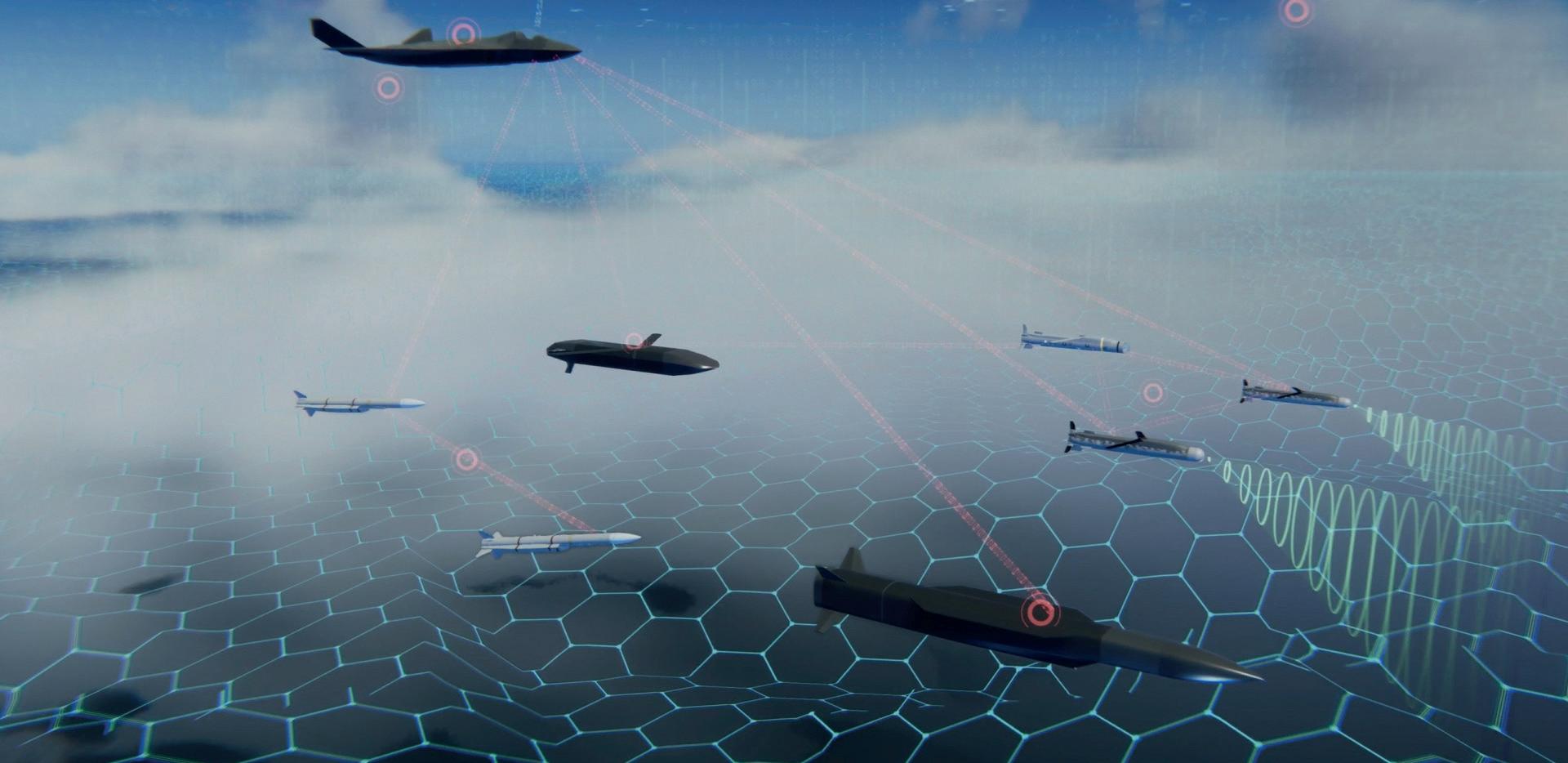

As we consider and prepare for the future evolution of air and space power, we must focus upon the threats and opportunities aligned with developments in missile technologies, so that we can better defend the United Kingdom using integrated defence and utilise the advantages of longer-range and higher-speed precision strike capabilities. Our complex weapons strategy is playing a critical part in strengthening our resilience, while ensuring long-term cost avoidance. We can enhance our capabilities further using greater numbers of uncrewed and autonomous systems, while bene ting from their persistence, survivability and increased combat mass. We must focus upon the enhanced operational e ectiveness that will be generated from increased levels of human-machine teaming and the novel application of emerging technologies.

The UK aerospace sector has accounted for 83% of the UK’s defence exports over the past decade. Our involvement and long-term investment in international programmes, including Typhoon and F-35, highlight the enormous potential of aerospace to enhance UK prosperity, while augmenting our industrial resilience and strengthening our operational independence. And the Global Combat Air Programme will allow us to share the technological innovation and creative energy of Italy and Japan throughout this century and beyond. This spectrum of capabilities and initiatives highlights how the United Kingdom remains very much one of the world’s leading global air and space powers.

As we celebrate 15 years of Ascent, we are proud to deliver the UK’s Military Flying Training System – creating the next generation of military aircrew.

Ascent’s integrated training solutions bring together classroom teaching, simulators, virtual reality environments and live flying. Producing the adaptable aircrews our customers need, and making our trainees’ dreams a reality.

See the UKMFTS fleet of training aircraft and meet some of our current trainees at the Ascent showcase at:

@ascentflighttraining ascentflighttraining.com @ascentflight

KCB ADC FREng, Chief of the Air Sta

KCB ADC FREng, Chief of the Air Sta

Welcome to this 2023 edition of Air & Space Power, the theme of which is ‘Global Air & Space Power’. As global air and space leaders, we are charged with defending our airspace and deterring aggression against our nations, our allies and our alliances. These roles are especially important as we witness states who seek to undermine the current international order by force, and others who are using constant competition to evolve the international system in their favour. This is why our collective actions going forward, including how e ectively we deter and defend against aggression and how actively we integrate and evolve our capabilities, will help to determine the relative peace, stability and prosperity of our nation and those of our allies.

As we examine the ongoing con ict in Ukraine, and Russia’s continuing aggression against its neighbouring sovereign state, we are continually evolving and re ning our perspectives of the value of air and space power. We must avoid the type of brutal, industrialised slaughter that is being prosecuted by Russia against our Ukrainian allies. We must do everything possible to ensure that Ukraine wins this bitter con ict and that unrelenting Russian aggression fails. And we must also do everything to ensure that such aggression will fail if it is ever used against us.

We will do this by focusing relentlessly on achieving our core mission of gaining, maintaining and sustaining control of the air, and of guaranteeing assured freedom of action for our capabilities across all of the operational domains, especially

the land and the sea. We will do this by integrating seamlessly across all operational domains and with our allies and partners, so that our collective capabilities are ampli ed, making any potential adversaries think twice before engaging us.

One thing is certain in our increasingly uncertain future –that the most agile and innovative air and space forces will win against our adversaries. So, in delivering global air and space power, we must focus upon increasing the agility of our air and space operations, by always staying ahead of our adversaries and e ectively complicating their strategic calculus.

We will do this, alongside our allies, using Agile Combat Employment and utilising dynamic deployments of our air, space and cyber capabilities across and around the globe. Our agility will be enhanced by evolving our global air and space capabilities using constant innovation in how we operate and ght. The increasing agility of our air and space forces will rely upon how e ective we are at adapting to and embracing the next generations of technological developments, so that we can incrementally enhance and

improve our current air and space capabilities, together with the supporting systems and personnel that operate them.

And most important will be the agility that we develop within the mindsets of our people, for many of the innovations, improvements and enhancements envisaged will only be successful due to the resourcefulness, resilience and mental agility of our aviators. This is why our focus on our people, their skills and the sustainability of our operations is so vital to our future success.

I am especially thankful to my fellow air chiefs from Italy, Japan and the United States for their contributions to this key air and space power publication. These highlight the signi cant value of our strategic partnerships in developing and delivering air and space power globally, which I am certain will endure throughout this century and beyond.

I hope that you enjoy this comprehensive and thoughtprovoking spectrum of articles from our aviators, senior civil servants and aerospace industry leaders. These highlight that developing and delivering world-class and world-beating air and space capabilities will only be achieved by working together as one team, cohesively and collaboratively, to protect what we value, using global air and space power.

Leveraging the United Kingdom’s world-class defence and aerospace capabilities, the RAF’s Protector RG Mk1 will provide unmatched awareness and multi-domain integration. Together, we make Protector the most advanced and versatile remotely piloted aircraft system ever built.

Supporting the UK Government’s Global Britain vision requires a military capability that is equipped, sta ed and trained to operate, often at a moment’s notice, almost anywhere in the world. Even the most casual of observers cannot miss the fact that, when immediate action is required, it is almost always the RAF that is in the vanguard of that response – be it delivering actual repower, humanitarian aid or evacuating those in danger.

The ability to step up to the mark instantly to whatever the task may be re ects a constant renewal and refocusing of air and space power. Air Marshal Harv Smyth reveals how this is achieved and the extent of this activity over the past year. Crucially, he highlights that a global capability requires a global network of allies, partners, suppliers, supporters and hosts. It also necessitates an ability to protect and sustain forces while on global operations – hence the RAF’s Global Enablement concept, which is expertly explained by Group Captain Jason Thompson in his piece on Agile Combat Employment, backed up by his namesake, Air Commodore Jamie Thompson, in his article on the reorganisation of the RAF Force Protection forces into a single ‘Global Enablement Organisation’.

Perhaps the most headline-grabbing activities with which the UK and, with it, the RAF have been associated over the past year or so are the AUKUS Trilateral Security Pact and the GCAP collaborative agreement. Air Vice-Marshal Simon Edwards reveals a far greater scope to the AUKUS agreement than is commonly expressed. Pillar 2 will see Australia, the UK and the

US collaborate on the vital emerging technologies of arti cial intelligence, cybersecurity and quantum computing. Mastery over these vital technologies will almost certainly represent the backbone of the RAF’s future ability to project global capabilities.

More recently, the signing of an agreement to design a sixth-generation ghter aircraft with Italy and Japan marks an astonishing milestone.

Having been established two years ago in April 2021, the UK’s RAFled Space Command continues to go from strength to strength, with over 500 sta members in place across the three armed services, industry and the civil service. Its Commander, Air ViceMarshal Paul Godfrey, highlights the growing responsibilities it is incorporating into its structure and its aspirations for the future.

Another new entrant into the RAF’s ranks is the Chief Digital Information O cer, Dr Arif Mustafa, who has been tasked with overseeing and implementing the digital transformation strategy that must provide the RAF with next-generation technologies and capabilities. This task will inevitably be reliant on an e ective cybersecurity infrastructure and capability, which is superbly explained by Air Vice-Marshal Tim Neal-Hopes.

As ever, we are indebted to those serving in the RAF, industry and elsewhere who give up their time to support this key RAF Air and Space Power publication. I have named but a few of them. I would also like to extend our gratitude to the Air Chiefs of Italy, Japan and the US, who have also contributed to this year’s issue.

The demands of military aviation in the 21st century leave no room for compromise – or outdated solutions. With cutting-edge technology and unrivalled build quality, the EJ200, installed in the Eurofighter Typhoon, has proven time and again to be the best engine in its class. To find out more about our market-leading design and unique maintenance concept, visit us at www.eurojet.de

The EJ200: Why would you want anything less?

The United States does not ght alone. We cannot deter alone or succeed alone. These truths are not new or novel, nor are they subject to doubt or change. What is changing, however – by necessity – is what ‘ ghting together, deterring together, succeeding together’ means in an age of strategic competition and multi-domain con ict encompassing cyber and space.

The successful practices of the past must adapt to meet the emerging threats and challenges in the Indo-Paci c and around the world. In short, we must integrate. Our alliances, cooperative agreements and partnerships must be modernised with increasing collaboration.

To succeed, we must innovate and accelerate, and we must do it together.

What does this mean? It means our e orts must be integrated by design, for one.

It means emphasising collective ‘capabilities’ along with raw ‘capacity’ to nd ways of merging systems, equipment, personnel and doctrines across all domains like never before. It means dictating conditions, so the totality of our combined forces present so many potential actions from so many avenues and domains, and with breathtaking speed, that no competitor can expect advantage or success. It’s a tall order, but I am optimistic.

One reason is the health of our alliances and partnerships, as well as the enduring cooperation and bond between the U.S. and United Kingdom.

NATO remains the standard by which alliances are measured. That truth has been validated – even strengthened –in the face of Russia’s brazen invasion of Ukraine. The same is true for our partnership with the United Kingdom.

Each of our nation’s air forces play an essential and instrumental part in maintaining – and enforcing, when necessary – the global rule of law and providing the backbone to our alliances and partnerships. By locking arms and working together

need to start with that approach at the beginning, versus building from our individual perspectives, then trying to gure out how we bring our allies and partners in. We are working hard across the U.S. Air Force to achieve this goal. While we have more to do, we can also point to progress. Our collaboration with Australia and the United Kingdom in developing the E-7A battle management, command-and-control aircraft is a good example of an ‘integrated by design’ opportunity. This e ort is predicated on a long-term partnership with the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal Air Force based on sharing information and experiences, as well as personnel.

as many of our nations have for generations, we underwrite peace, global stability and deterrence.

To sustain this history and performance, however, we must adapt our forces, our alliances and our partnerships to meet the challenges of today and those of the future. This is the reason I stress ‘integrated by design’.

To be integrated by design, we need to start at the beginning with the ‘end’ in mind. If the goal is to be integrated with allies and partners as a combined and credible force, we

The Royal Air Force and U.S. Air Force have sent operators and maintainers to train, assess and be on hand as the Royal Australian Air Force carries out the latest E-7 upgrade. We are using data shared by Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force testing to inform our own independent Air Force Operational Test and Evaluation Center assessments. Moreover, both the Royal Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force were invited to participate in the drafting of the U.S. Air Force’s Capability Development Document to help ensure that our path forward on this critical capability remains aligned. Another example is the F-35; designed by eight international partners, the fth-generation aircraft is the backbone of not only the U.S. Air Force, but 16 other nations ying

“To succeed, we must innovate and accelerate, and we must do it together”

a plane designed from the start to be interoperable with allies and partners.

The experiences and bonds gained from our E-7 and F-35 e orts, along with others, allow us to rapidly integrate current and new technologies in response to future threats as they emerge across the spectrum of operations, and we will continue to develop future capabilities with allies and partners in mind. While doing so brings important capabilities to all our forces faster, and at less cost, and makes us more interoperable, being integrated by design with allies and partners isn’t just about platforms and hardware – just as important is the way we develop our people, policies and processes.

We are extending the presence of exchange o cers and liaison o cers to help cultivate strategic dialogue and approaches to future operational challenges and expanding collaboration on such things as war games. We are ensuring the U.S. Air Force’s contribution to Joint All Domain Command and Control, known as Advanced Battle Management System, which is designed to maximise the Joint Force’s capabilities, choices and

decision-making, is built on a common foundation and compatible with allies and partners. We are reviewing policies and processes that may unnecessarily restrict information sharing with allies and partners, and encouraging our members to share information more broadly.

directs the Triangle Institute for Security Studies and the Duke University Program in American Grand Strategy, correctly concluded in a 2021 analysis: “Alliances... help create a sense of permanence and shared purpose in key relationships; they provide forums for regular

It’s complicated work, but we have adapted before, and our alliances and partnerships have evolved time and again to successfully meet new challenges and crises, sometimes in the face of daunting odds.

As Hal Brands, the Henry A Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global A airs at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and Peter B Feaver, who

interaction and cooperation; they conduce to deeply institutionalised exchanges (of intelligence, personnel, and other assets) that insulate and perpetuate friendly associations even when political leaders clash.”

That was true during both World Wars, during the Cold War and in con icts since. We have adapted and strengthened, and remained e ective and resolute, each step along the way. We will once again.

“Our alliances and partnerships have evolved time and again to successfully meet new challenges and crises, sometimes in the face of daunting odds”

The UK’s senior air and space war ghter, Air Marshal Harv Smyth, tells Simon Michell how the RAF is sustaining high-end operations and activities across the globe – west to North America, east to Australia, up in the High North and down in the South Atlantic from beneath the waves all the way up to geostationary orbit

By

2025,the Queen Elizabethclass aircraft carriers will have two front-line F-35 squadrons at their disposal

– 617 Squadron

‘The Dambusters’ and 809 NAS ‘The Immortals’ (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

“As the RAF’s senior war ghter, my job is to generate the required air and space forces according to our Command Plan, and deliver the appropriate decisive operational e ect across all operating domains – air, land, sea, cyber and space – from beneath the sea all the way through the air domain into geostationary orbit,” explains the RAF’s Air & Space Commander (ASC), Air Marshal Harv Smyth. To make that task even more challenging, all the capabilities and personnel at his disposal have to be delivered on a global basis – across the Atlantic to North America and the Falkland Islands,

over the deserts of the Middle East, into the heart of Africa and out to the furthest shores of the Paci c to Australia on the other side of the world. These operations are not restricted to a single type of activity, far from it. According to Smyth, “They encompass everything from protecting the homeland and UK overseas territories, to ensuring the safety of RAF equipment and people wherever they are based – so-called ‘Global Enablement’ –as well as delivering air support to current operations, including in the oft forgotten Iraq and Syria.” His role also covers elding the F-35 Lightning Force, not just from RAF Marham and other land bases, but also

from the Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, in whichever sea or ocean they are tasked to sail.

Also sitting under his remit is the delivery of humanitarian aid to those in regions hit by natural disaster, such as the recent earthquakes in Türkiye and Syria. And, as if that were not enough of a challenge, he has within his bailiwick all RAF bases and Space Command, which he helped to establish two years ago in his previous job as Director Space within the Ministry of Defence, and which now boasts over 500 personnel from across all three Services, the Civil Service and Industry on its roster. Without doubt, there are few people in the UK Defence community quite as busy as ASC.

Things are getting busier. In February 2023, his Air O cer Commanding (AOC) Number 11 Group, took over operational control for air activities based in the Middle East; these used to be run by the Chief of Joint Operations (CJO) out of Permanent Joint Headquarters (PJHQ) in Northwood, North London. This transfer of duties has been implemented to free up the CJO and PJHQ to concentrate on the ‘Big Picture’, while ASC and 11 Group can focus on what they are better suited to – managing and sustaining day-to-day activities – or what Smyth calls “getting down into the weeds of the implementation of air and space power.”

Of all these taskings, Smyth is quick to point out that his overriding priority is the defence of UK homeland and sovereign territory, wherever that may be. This is not just maintaining a Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) force of Typhoon jets at RAF Coningsby and Lossiemouth to be ready to deter Russian longrange bombers and rogue commercial airliners all day every day, it is also safeguarding UK critical national infrastructure such as undersea electricity and communications cables and gas pipelines, a role taken forward magni cently by the RAF’s new P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol force. ASC’s Poseidons are experts at hunting adversary submarines, alongside ensuring the nation’s continuous at sea deterrent (CASD) is not interfered with.

Smyth points out that, in essence, the defence of the UK is inextricably linked to the NATO Alliance and the defence of the transatlantic community, and so much of this work is a joint e ort. Testament to this axiom is the UK’s enthusiasm for partnerships. Beyond NATO, the RAF plays a leading role in the Joint Expeditionary Force comprising 10 nations from Scandinavia and the Baltics alongside Denmark and the Netherlands. The UK is also a major player in the Five Eyes group of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US, the origins of which predate NATO. In 2014, Germany and France joined a Five Eyes grouping to create the CSpO (Combined

Space Operations) initiative. This group keeps an extremely close eye on what is happening in space and is very active at the United Nations to reign back irresponsible behaviours. This work is vital to the security of the UK, as the protection of the country’s space-based assets is paramount, “Protecting a Skynet satellite in its geostationary orbit is every bit as important to this nation as protecting our aircraft carriers when they go on operations,” says Smyth.

Since independence, the relationship with Australia has always been very close and is getting strategically more important. Having been invited by the Royal Australian Air Force to participate in Exercise Pitch Black in the summer of 2022, Typhoons from 6 Squadron left RAF Akrotiri, accompanied by a Voyager air-to-air refueller and an A400M Atlas. After a successful visit, they returned home via India and Malaysia, undertaking a soft power engagement role to cement ties with those important partners in the Far East.

Pitch Black came on the back of the enhanced Trilateral Security Pact, AUKUS, announced in September 2021, that created a collaborative partnership between Australia, the UK and the US to supply Australia with a nuclear-powered submarine capability. “Pillar 2 of AUKUS will see us collaborate on areas such as arti cial intelligence, cybersecurity, electronic warfare, hypersonics and quantum computing,” Smyth highlights.

A quick scroll down Smyth’s Twitter feed (@HarvSmyth) highlights just how busy 2023 has been so far. The January Red Flag exercise in the US, which Smyth describes as “the hardest three weeks of ying any air crew will endure”, was extensively redesigned to enable the participants to simulate a war in the Paci c, the key factor being preparing for what ASC refers to as “the tyranny of distance”. By combining the air training ranges from Utah

to the west coast of the US, and projecting them a further 600 miles into the Paci c Ocean, it was possible to replicate the types of onerous 12-hour missions that a con ict in the Paci c would demand.

The Middle East has also seen plenty of spectacular activity, thanks in no small part to RAF Akrotiri on Cyprus, which serves as a hub for most of the activity in the region, and the Al Udeid base in Qatar, which houses 83 Expeditionary Air Group. Over the space of a week in February, Smyth visited Al Minhad Air Base in the UAE to drop in on the RAF’s 906 Expeditionary Air Wing, which had just played a critical role in enabling humanitarian aid delivery to earthquake victims in Türkiye and Syria. From there he jumped to Thumrait Air Base in Oman to be briefed on Exercise Magic Carpet, in which Typhoons and Voyagers were taking part. Next stop was Dhahran Air Base in Saudi Arabia to see how more RAF Typhoons were getting on as part of Exercise Spears of Victory. Although this was not quite as large or complex as the benchmark Exercise Red Flag, Smyth is very e usive with his compliments for this training module and foresees a time when it might become comparable.

Perhaps no other geopolitical event highlights ASC’s role and signi cance for UK Defence better than the UK’s response to the illegal invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Almost every aspect of Smyth’s capability portfolio has been involved in the e ort to shore up Ukraine’s ability to resist Russian forces and their Wagner Group paramilitaries. The Air Mobility Force out of RAF Brize Norton has ferried tens of thousands of rounds of ammunition to Ukraine, as well as equipment – helmets, body armour, night vision goggles and medical supplies. On their return journeys, these aircraft have brought back thousands

of Ukrainian recruits for training. The RAF Regiment has then helped to train these recruits, alongside their counterparts from the British Army. Once they have completed their training, the Air Mobility Force takes them back to Ukraine to join the ght.

Furthermore, the RAF Combat Air Force has patrolled NATO’s eastern borders as far down as the Black Sea. It should also not be forgotten that RAF reconnaissance and surveillance aircraft continue to patrol the skies adjacent to Ukraine, gathering vital intelligence that is then delivered to the Ukrainian forces. RAF intelligence analysts have been working at out, turning the “beeps and squeaks” that the RC-135W Rivet Joint electronic surveillance aircraft have swept up into actionable intelligence. “Make no mistake about it, these people are the silent heroes. In a world where information is key, our ISTAR Force is generating the information dominance that is such a game-changer. I take my hat o to them,” says Smyth.

When asked what value he thinks all this activity and capability adds to global security and stability, Smyth insists that it is not just hard power that makes a di erence – soft power has an equal role to play. “The convening power of the RAF is something to be immensely proud of,” he says. The Chief of the Air Sta ’s conference in London is an exemplar of this: last year, some 67 air and space chiefs from around the world were in attendance. And, in what was a global rst, more than 30 of them took to the stage at the Institution of Engineering and Technology to sign a declaration of intent on climate change collaboration to ensure that military aviators make a decisive contribution to ensuring the world remains a place in which humans can prosper. It is ASC’s job to sustain and maintain the RAF operations that will ensure they can do so in a secure and stable world.

universe of information can be collected, analysed and acted upon will hold a key to the e ective projection of force across domains that are becoming increasingly interconnected. E orts such as the UK’s Multi Domain Integration (MDI) are vital to ensuring our war ghters have the information they need to achieve their goals.

How can we move MDI from concept to reality?

Nick Cha ey Chief Executive UK, Europe and Middle East, Northrop Grumman Corporation

What lessons can military planners take from what we have seen in the Ukraine war?

I think one the biggest lessons we can take from Ukraine’s valiant defence of their country has been the impact of leveraging Information Advantage in the battlespace, and the advantages this can be bring when leveraged within a digital- rst mindset.

How Ukraine has achieved this has been remarkable. Since the invasion began last year, they have exploited the ubiquity of open-source information in a manner never before seen in con ict, alongside a proliferation of low-cost commercial platforms, like consumer-grade drones as information sources. The digital devices from which tactical information can be gleaned are in the hands of almost everyone in and around the battle eld, generating a constant ow of data –intentional and unintentional, accurate and false, from friends and from foes.

As allied nations look to future con icts, the myriad ways this new

What makes MDI such an essential pillar of future war ghting?

MDI is about developing a more holistic approach to meeting threats in the future battlespace. Intelligently connecting sensors to fuse information and then exploit the conclusions e ciently and e ectively through the optimal e ectors across every domain will result in a system of systems that can accelerate responsiveness and reduce costs without hindering the tactical exibility of the commander.

It will provide a new level of Information Advantage, allowing leaders to make smarter decisions, faster, and helping to keep our war ghters safe. It will also enable true interoperability across allies, by joining up of forces through the ability to seamlessly share information and capabilities.

MDI is about more than just making systems talk to each other. It enables a new way of operating across every area of the armed forces, from people and processes to procurement. It leverages the adoption of open modular architectures, to ensure that every new platform/system can be integrated into a common operating picture.

We think there is a clear path to accelerating the UK’s MDI position through taking advantage of tested interoperable capabilities that can help the UK leapfrog the challenges it faces today. Investment in proven, truly open, multi-domain architectures can provide the UK not just with a battle-ready system, but the framework and capability to proliferate this approach to other programmes.

A good example of this approach in action is IBCS: NG’s integrated air and missile defence battle command system, which recently began full rate production for the U.S. Army. As a fully open, modular and softwarede ned capability, it is the U.S. Army’s Programme of Record and serves as their chief contribution to JADC2.

More than just a smart piece of software, the system’s resilient, open, modular, scalable architecture is foundational to deploying a truly integrated network of all available assets in the battlespace, regardless of source, service or domain. It enables the e cient and a ordable integration of current and future systems, including assets deployed over IP-enabled networks, counter-UAS systems, fourth- and fth-generation aircraft, space-based sensors and more.

A digital- rst, software-de ned mindset empowers rapid and, crucially, e cient integration of new capabilities, regardless of service or manufacturer. It’s an approach that should de ne the future of defence capability and procurement for the 21st century.

Air Marshal Johnny Stringer, Deputy Commander of Allied Air Command at Ramstein Airbase, Germany, reveals how his command ensures the security of NATO territory, from the High North to southern Italy and from the Azores to eastern Türkiye

The unprovoked and illegal invasion of sovereign Ukraine by Putin’s Russia has upended the post-Cold War security consensus in Europe. NATO Allied Air Command, and the national air forces of Alliance members, have been on point since 24 February 2022 to keep our nations safe. What has that looked like, and how might it evolve in the future?

The most obvious manifestation of enhanced vigilance activities in the air domain were the 24/7 combat air patrols (CAPs) own on NATO’s eastern

ank at the start of the Russian invasion. Fighter aircraft from across the Alliance were operating from both forward and home bases, fully armed to ensure the defence of our airspace. Less obvious, but essential, were the air-refuelling tankers and airborne early warning (AEW) aircraft to keep them fuelled while on CAP, and to provide situational awareness to Alliance members and partners. The RAF has provided Typhoon and F-35B fast jets, either ying from home bases in the UK or deployed forward to other NATO nations, supported by Voyager tankers.

On the ground, forward-deployed surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries provided additional defence and reassurance. The entire enterprise was and is commanded and controlled (C2’d) by the standing Air C2 footprint that protects NATO airspace across from northern Norway to Sicily, and from the Atlantic Ocean to eastern Türkiye – in total, 81 million sq km. This is NATINAMDS, or the NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defence System. And we continue to maintain enhanced, rotational deployments to deter Russian aggression and reassure our populations.

Our aircraft have also been at the heart of NATO’s intelligence collection to understand what is going on in and around Ukraine. For the RAF, our River Joint intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft have made a vital contribution. The RAF’s P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft have also own operational missions to help secure our seas, as well as our skies.

For the past three decades, NATO’s air and missile defence shield was orientated towards an air policing mission, ensuring the peacetime integrity of NATO airspace. Like much of the Alliance, the reduced threat allowed reduced investment: we have seen this manifest in many ways (including

the ex-military bases in continental Europe now much favoured by the burgeoning cut-price airline sector). The past 15 months have, thus, been instructive in many ways, with the geopolitical and the technological posing challenges that we had hoped had been consigned to history.

The nature of the threat has expanded and proliferated enormously in the space of a decade. We must now conceive of Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) as being one of our most challenging tasks: from weaponised commercial and one-way attack drones, through a multitude of cruise missiles launched from land, sea and the air, to hypersonic air-launched missiles, such as the AS-24 ‘Killjoy’. This last weapon is actually an air-launched ballistic missile, illustrating how the boundaries between IAMD and Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) are becoming increasingly blurred. And with much of Russia’s tactical activity blunted by the heroic and imaginative Ukrainian Armed Forces, they have become more reliant on their stand-o missile systems.

How do we meet this ever-evolving and complex IAMD mission? We can see it through four elements. Firstly, we need the Capabilities

RAF Rivet Joint intelligence aircraft have been helping NATO monitor Russian activity in and around Ukraine

RAF Typhoon fast jets have been undertaking enhanced air patrolling of NATO’s eastern ank (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

that allow us to detect (or sense) and engage any threat coming at us through the air domain; for BMD, this includes space too. The radars and other sensors that allow us to develop the highest-quality Recognised Air Picture will be augmented and enhanced by a variety of new equipment being elded by NATO’s air forces, and its surface-based air and missile defence units.

Secondly, we are evolving the overall IAMD Architecture: how we link bases, units, C2 centres, radars and platforms, and across all domains too –this not just the preserve of the Air Component. We need to understand, decide and act faster than we’ve been used to, and within an extremely complex operating environment. This then speaks to ensuring that our Authorities (or permissions) continue to evolve to match the threat; like many things, this is a political and policy issue, as well as a military one.

Finally, we must ensure that how we posture our forces is optimised against our adversaries. As noted above, there are signi cantly fewer bases (and aircraft and SAMs) than during the Cold War. We need to be basing our assets, our logistics and our people where they can be most e ective... and most survivable too. Accordingly, signi cant conceptual and practical e ort is being put into Agile Combat Employment across NATO’s air forces. This is (far) more than a back-to-thefuture reprise of Cold War operations – although there are many valuable lessons from that era – and elsewhere in this journal you’ll nd AVM Phil Robinson’s insights on this key topic.

For now, NATO Allied Air Command maintains its 24/7 watch over the skies of our 31 nations, deterring and reassuring, yet ready to engage at a moment’s notice – as we have for over 70 years.

What kind of support does BAE Systems provide to the RAF’s frontline eet?

BAE Systems has a long history of providing support to the RAF’s frontline. Today, we support both Typhoon and F-35 eets, where our team ensure eets are ready when and where they are needed, whether that is to deliver on operations or securing the skies with Quick Reaction Alert. Maintaining operational readiness, often in complex and challenging environments, is key and we understand operational e ectiveness not only relies on the availability of equipment, but on welltrained people with the capability to operate and support the frontline.

How has BAE Systems played a part in supporting the UK’s response to heightened tensions in Eastern Europe?

The RAF’s Typhoon and F-35 eets have played a vital role in supporting NATO-led operations as part of the

response to the Russian aggression seen in Ukraine. Our teams at RAF Coningsby, RAF Lossiemouth and RAF Marham have been at the heart of the team that has responded to the ramp-up in operational tempo. Particularly across RAF Lossiemouth and RAF Coningsby, our teams have stood-up new maintenance capabilities to ensure the availability of the aircraft. We are proud of the way our people have brought their vast experience in fast-jet support to ensure Typhoon and F-35 continue to deliver as part of the NATO Alliance.

Our position at the centre of Typhoon’s development gives us a unique insight into the support and training requirements as the aircraft evolves and as we support the RAF and others transition to a sixth-generation

Training strategy, ensuring pilots are ready for the future battlespace. One example is the work we’re doing with leading innovative technology companies to create a collective training environment, enabling air, land, sea, space and cyber forces to plug in and train together. This knowledge will be essential as we work with the UK to determine the training requirements for Tempest.

What are you doing to prepare future support for Tempest?

We’re already looking at the support solutions that Tempest will demand and the increase of software capability that will be needed. We are also working alongside the RAF to use transformative technologies – from exo-skeletons to virtual reality, robotic ‘teammates’ and digital twinning – to meet the support demands of the future, as well as enhancing what we deliver now. The introduction of these

capability. Our support to the RAF Typhoon eet is underpinned by a long-term contract, the Typhoon Total Availability Enterprise (TyTAn), which is aimed at improving aircraft availability while reducing operating costs. This has generated £500m in savings, which have enabled further investment into additional capability development. Our pedigree on Hawk provides a solid foundation for our Next Generation

technologies can be used to reduce costs and improve the availability of the frontline forces, while improving safety.

As we develop the future support solutions we will need to consider how technology can help us to deliver capability and readiness at speed and lower cost, while developing the skills and knowledge to provide the right support for a complex sixth-generation combat aircraft such as Tempest.

“Our position at the centre of Typhoon’s development gives us a unique insight”

Air Marshal (Retd) Greg Bagwell, President of the Air & Space Power Association, explains how the war in Ukraine has reinforced the doctrine of air superiority and the value of investing in air power

Some have heralded this war as a portent for future wars, but to what extent is this true? What is clear is that, while this duel continues at the strategic level, we have seen minimal operational or tactical e ect of air attacks on the battlefront. Here, brutal urban and trench warfare readily demonstrates how land ghting descends to the visceral without the decisive e ect of manoeuvre and joint res, and the almost absence of e ective air strikes.

to the systematic suppression and, ultimately, destruction of the enemy’s ability to compete both in the air and, increasingly, from the ground.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is now well into its second year and Ukraine continues to defy the odds. Not least of Ukraine’s attributes is its heroic stoicism, but it has also become a master of information, deception and adoption. Of these, its adoption of a myriad of conventional equipment and, increasingly prominent, unfamiliar capability types, such as tactical drones, has been noteworthy. However, what has been most notable so far is the rather muted impact of air power on the con ict. This has been down to two reasons: the poor performance of the much larger and capable (on paper) Russian Air Force, and the prevalence of increasingly lethal ground-based air defence. In the absence of traditional dominant air power, drones and longer-range, faster missile attacks have become more commonplace. This has resulted in an aerial duel between these and the ground-based air defence systems of Ukraine –missile-on-drone and missile-onmissile. It has descended into a war of attrition in the air, as well as on the ground, one that has become a test of endurance of both will and munition reserves/manufacture.

The tactical, low-cost dronedelivered munitions have merely replaced or supplemented mortar or short-range artillery, rather than air power. It has become a highly e ective tactical tool, but one that is only truly e ective in a static, attritional stalemate, rather than one of fastpaced manoeuvre and o ensive action.

So, rather than demonstrate the end of air ghting as we know it, this con ict reinforces the doctrine of air superiority, as to ght without it is far more costly in lives, resources and, ultimately, the ability to triumph. One only has to war-game the outcome of this con ict if air power had become dominant for one side.

As I write, the much-awaited Ukraine counter-o ensive has just begun; if it is to succeed, it will do so because neither side enjoys air superiority, not because it is no longer relevant.

But to what extent is air superiority a reality with increasingly lethal air defences? Is it just a doctrine based on the suppression of the enemy’s ability to engage in the air or deny the domain e ectively? This requires the ability to operate within an initially hostile environment, through

When, and only when, air dominance is assured can true progress be made on the ground. Yet, while such capability does not come cheaply, its investment should be underpinned by the fact that the alternative is to plan for air stalemate or even stagnation, which requires counter investment in vast land mass to conduct long, attritional wars – this is not a cheap or a coste ective option. Also, it should be unpalatable for many reasons, not least of which is the political cost of engaging in such a protracted and bloody campaign. Indeed, the very attainment of an air superiority capability from the outset is likely to act as the main conventional deterrent to the start of such hostilities.

Much has been made in this con ict of Russian nuclear capability and possible thresholds for its use, but too little debate has been had about the value and bene t of a credible conventional deterrence –air superiority provides such an option. If Russia has learned one thing from its failure in Ukraine, it is that the air superiority capability and doctrine of NATO would result in abject failure, should they make the same miscalculation with the Alliance. More sophisticated drones and missiles may well enhance and increase the means by which air superiority is delivered and maintained in the future, but they don’t change the fundamental premise of freedom of action that air superiority confers.

Air Commodore Adam Bone, Head of Space Operations, Planning and Training at UK Space Command, explains what needs to be done to deliver the requisite levels of integration and the bene ts that this will generate for the UK

Nation-state reliance on the networked systems and capabilities that occupy space underpin a formidable global information-sharing medium and enable a functioning 21st-century society. From assured communication to critical intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) data, space enables precision military e ect in what is an increasingly congested and contested environment. Only through meaningful capability integration can we be sure to adequately protect and defend UK interests in space and exploit the growing potential to deliver multi-domain operational advantage.

Like us, our allies and partners are required to delicately balance their respective ambitions

for space sovereignty with the requirement of collaboration and integration with global neighbours. Greater integration with many existing and aspiring spacefaring nations has helped situate and secure the UK’s place in space as it reframes many of its previous astropolitical assumptions and invests in its international defence and security allegiances across Europe, the US, and the Indo-Paci c. Indeed, there are many mechanisms helping us better integrate with the global space enterprise for the bene t of the UK. Firstly, the Space Integrated Approach (SIA) is the UK’s primary mechanism for driving coherence across the UK/US space enterprise. The SIA focuses collaborative e orts across Command and Control, Operational Planning, Cooperative Capability

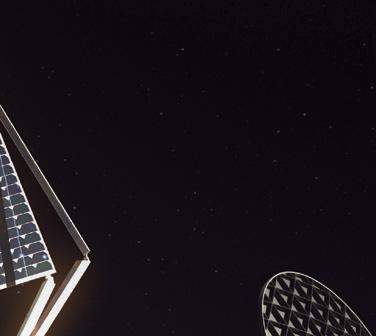

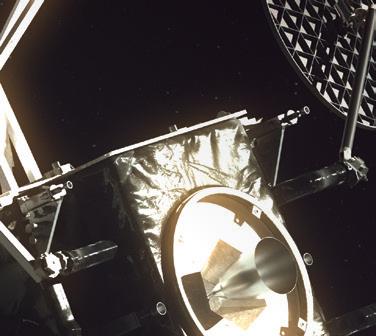

In a congested environment, space-based capabilities enhance military precision (PHOTO: MOD/CROWN COPYRIGHT)

While accelerating bilateral cooperation, the SIA is also working hard to explore options for greater integration with Australia and Canada. Bene ting from this close relationship has been the Five Eyes + France/Germany Combined Space Operations (CSpO) Initiative, where we have established agreements with seven CSpO nations, in addition to Japan and the Republic of Korea, with the expressed aim being greater interoperability and integration with our international partners.

With NATO’s recognition that attacks to, from or within space represent a clear challenge to the security of the Alliance, we continue to support the NATO space enterprise by providing operational products from the UK Space Operations Centre (UKSpOC), and space subject-matter experts to support NATO exercises. Signi cant opportunity also exists within the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) and Combined JEF (CJEF), both in terms of operational interoperability and training, and also in coherent and aligned capability and force development.

Both UK and French Space Commands are maturing at pace – alongside SPO Space Policy, UK Space Command jointly chaired the inaugural JEF Space Working Group in March 2023. Under the banner of CJEF, the connection is well established and optimised to enable mutual support. A bilateral Space Roadmap has been established to guide e orts

towards achievable goals and to better identify speci c areas of fruitful cooperation. The NATO Space Centre of Excellence, in which France and the UK are engaged, promises exciting possibilities for developing the space relationship within the NATO framework.

The UK SpOC is Defence’s Operational Level Command and Control Unit and is directed to support three missions at the operational level, from which several tasks are generated to provide services across Defence, HM Government and the commercial sector. These missions also provide the Ministry of Defence with the understanding of the space domain required to identify opportunities and threats to operations.

Space Command has developed an innovative approach to providing agile and iterative development of operational capability demonstrators as part of its embryonic Space Control research programme. This work has been based on the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl)’s broader Space Programme and in close collaboration with key space industries following the strategic guidance set out in the Defence Space Strategy to establish capabilities to Protect and Defend our existing capabilities and our freedom of manoeuvre in the space domain.

Space e ects within the Joint Force Space Command HQ, and those of the component commanders, are planned, generated and coordinated by a network of Space Liaison O cers (SpLOs) spread across each ghting domain. These o cers are

specialist operations o cers who assist in increasing the e ectiveness and e ciency of forces regarding ISR, missile warning, space and terrestrial weather impacts, communications, positioning, navigation & timing (PNT) and maximising the utility of spaceenabled technologies. Plans are being worked with UK Space Command to enable a UK Space Academy to grow space expertise and nurture a trained workforce capable of delivering the space component of multi-domain operations into 2040 and beyond.

national security and the needs of Defence: satellite communications, space domain awareness, ISR, command and control, space control, PNT and launch. By 2035, we will have transitioned to the next generation of Skynet, enabling provision of secure satellite communications. We will have robust spacedomain awareness through a system of systems, with a diverse mix of assured data sources. Our Low Earth Orbit multi-spectral ISTARI constellation will be a fully functional operational capability providing assured ISR

Space services will continue to proliferate worldwide as technological and cost barriers fall and international partnerships for space support grow. State, non-state and commercial actors will increasingly gain access to data and services emanating from space. The number of space launch companies and satellite service providers will expand at least through 2025. And with more groups – commercial, academic and even private –now able to reach orbit, the growth of satellites and debris in space is expected to increase. Therefore, e ective integration, and decon iction, is vital. Seven critical capabilities spanning the space domain have been identi ed to support UK

and a digital backbone – this will be critical to enabling the Integrated Force in the digital and data age. To fully enable the Integrated Force, UK Space Command will also develop Defence’s understanding of operating in a contested and degraded operating environment and strengthen defence and national PNT resilience through the development of alternative solutions.

UK Space Command will seek to enable the value and impact of Defence space capabilities to be greater than the sum of their parts. This will be achieved through ve themes in the management of our capabilities: exploiting capability synergies;

Integrating UK space capabilities with those of partners and allies will serve to deliver greater space awareness and enhanced security to all (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

“Space services will continue to proliferate... as technological and cost barriers fall and international partnerships for space support grow”

Plans are in progress to for a UK Space Academy to develop space expertise and nurture a trained workforce

(PHOTO: MOD/CROWN COPYRIGHT)

exploiting integration and connectivity bene ts between space capabilities; capitalising on dual-use opportunities across Defence and Civil space domains; ensuring value-for-money decisions across the enterprise when securing capabilities; coordinating collaboration with industry, academia, allies and other key partners; and cohering learning, development and knowledge spillovers across the enterprise.

The Commercial Integration Cell (CIC) was established to create a network for cooperation and collaboration between the Ministry of Defence, UK Space Agency and the commercial space sector. At present, seven commercial companies are members of the CIC, with three more in the process of joining. Future growth of the CIC will be key to delivering space domain awareness (SDA) as the domain becomes more complex and increasingly contested. Commercial members share information about their satellite operations and are briefed on pertinent threats to UK interests. Information can include electromagnetic interference detections, unattributed system anomalies, ephemeris (position and velocity) data and manoeuvre noti cations.

A Joint Task Force-Space Defence Commercial Operations (JCO) OCD is under way within UK Space Command, with IOC declared in April 2023. The US SPACECOM JCO initiative integrates commercial capability into military operations by contributing to SDA at the unclassi ed level to an unprecedented degree. Utilising commercial data from around the globe to provide indicators

and warnings of launch and nefarious on-orbit activity, it overcomes many of the limitations associated with threat information sharing in the highly classi ed Space domain.

Through greater integration and investment in initiatives, we aim to Protect and Defend UK space interests by:

– e ectively detecting space threats, accurately attributing malicious activity in space and communicating threats in space across Defence and to our allies and partners;

– maturing programmes spanning SDA, space-based ISR, command and control, and Space Control;

– establishing agreements with Combined Space Operations (CSpO) nations (and beyond) to improve interoperability with international partners;

– developing strategic space relationships – including with NATO – and focusing on integration across UK Government, industry and academia;

– nurturing a trained workforce capable of delivering the space component of multi-domain operations enabled by the delivery of a Defence Space Academy.

All of these will help us to meet UK Space Command’s enduring and exciting vision, to integrate seamlessly as one of the ve operational domains and ensure space is safe, secure and sustainable for all generations.

Kevin Craven, Chief Executive O cer, ADS Group, looks forward to UK defence companies continuing to support the RAF and strengthening ties with international partners

Government around closer partnership to help address the Armed Forces requirements for the future.

At the start of the year, I and many others were a little dismayed by the failed UK Space launch and the further news around the suspension of Virgin Orbit operations. However, our strong and agile UK space sector has so much to be proud of. We remain committed to increasing UK power in Space and becoming the leading provider of commercial small satellite launch in Europe by 2030. Our sector, collaborating with others, will continue to innovate, learn and deliver, and I look ahead with anticipation to the vertical launches planned from Scotland later this year.

February 2023 marked one year since the outbreak of war in Ukraine. I continue to be saddened at the sight of destroyed homes and hospitals. Since the outbreak of war, the UK has stood out for its staunch commitment in supporting Ukraine with advanced equipment and capabilities, and work continues through the International Fund for Ukraine. I have also noticed a marked culture change in defence, both in public opinion, but also in

The Integrated Review Refresh (IRR), published in March 2023, is a recognition of the importance of a strong domestic defence and security industrial base. In the years ahead, industry stands ready to accelerate its partnership with the Armed Forces and security services, providing advanced modern capabilities and strengthening relationships with international partners, including programmes like AUKUS and the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) with our strategic partners, Italy and Japan.

Undoubtedly, UK defence companies have the wherewithal to support the RAF in maintaining its leading edge, and continued partnership and investment will help our industries strengthen and grow. Including the uplift announced as part of the IRR, and the Chancellor’s Spring Statement, we will see a signi cant increase in defence spending over the next ve years. Furthermore, a Government aspiration over the longer term is to raise defence spending to 2.5% of GDP, when scal and economic services allow. This is welcome, and I await further details, including importantly a proposed timetable that will be essential in supporting industry to develop and deliver advanced next-generation capabilities.

For the UK’s Space power to continue to develop, it is essential for regional prosperity to be encouraged,

particularly where there are clusters of outstanding space organisations. ADS is exceptionally proud to be overseeing a pilot Space Technology Exploitation Programme (STEP), which, supported by the UK Space Agency, will enable SMEs in Northern Ireland to engage with large companies, and to use innovative, new solutions to overcome technology challenges – unlocking potential markets and building UK space capabilities.

To project the UK’s Air and Space power on a global stage, international ties must be strengthened at every opportunity. GCAP builds upon the substantial progress already made by the Team Tempest partners and presents a fantastic opportunity for the UK to drive innovation and technological development.

GCAP is expected to provide tens of thousands of skilled jobs in the UK, which are vital to high-value exports, and, as the project moves forward, ADS will work to ensure that our members, large and small, have access to the fullest range of opportunities for involvement.

Finally, throughout 2023 and beyond, I would like to see continued collaboration between industry, Government, the Armed Forces and security services, enabling the UK to project its advanced power. In September, I will be attending DSEI and look forward to welcoming international delegations to our United Kingdom Pavilion to show the very best of UK capability, able and ready to respond to an array of future threats.

Former naval ghter pilot Paul Tremelling, Business Development Director at Northrop Grumman UK, outlines how global multi-domain operations can be achieved and how they will transform the speed with which decision-quality information can be relayed to the e ector of choice for optimum e ect

As the con ict in Ukraine rages on, residents of the capital, Kyiv, have become grimly accustomed to air-raid sirens sounding across the city. The sirens sound as the Ukrainians search the skies and electromagnetic spectrum for indicators and warnings of impending attack, possibly in the form of sophisticated weapons such as the hypersonic Kinzhal missile.

While debate continues about how e ective speci c missile systems have been, their use, and that of many new or adapted approaches to warfare, allow an early look at the next generation of military capabilities. Aspects of Russia’s invasion have given military planners a glimpse of the future battlespace.

Many observations are being drawn from the Ukrainian con ict. Among them is the absolute necessity to understand and operate across the electromagnetic spectrum, in concert with physical and kinetic operations. This is, of course, neither surprising nor new – software has been famously ‘eating the world’ for decades already. But it does reinforce the importance of activities and operations that NATO and western alliances will have to master now and in the future if we are to survive to ght.

When the next ght comes, it will almost certainly involve multiple allied nations. The ability to instantly collaborate, share data and execute strategies among globally dispersed, multinational forces is

fast becoming an essential capability. The UK’s multi domain integration (MDI) initiative recognises this, calling for UK Defence to work seamlessly with its allies, and the US recently re-added a ‘C’ to its JADC2 (Joint All Domain Command and Control) moniker, standing for ‘combined’ and highlighting the need for interoperability with its international partners. Thankfully, the digital age is bringing notable advantages to interoperability and integration, across domains, but also allies. Whereas physical interoperability is only guaranteed by total commonality, in a more commoditised digital world small di erences can be surmounted by, for example, the use of gateways and translators. On top of this, technology has become cheaper and, therefore, more replaceable. The likelihood of taking the battle eld on consecutive days with a di erent 155mm cannon is zero. But using a di erent drone/tablet combination is now de rigueur

Digital compatibility also speeds up integrated capability. If air system mission software is ‘Pyramid compliant’ it is far easier to upgrade, as the reference architecture is established and available. Immediate integration with existing C2 tools becomes achievable, as is the employment of a common user interface. If our aim is to produce and upgrade readily certi able software applications, then the use of software factory methodologies is key. The actual applications and their use cases will not necessarily become apparent until a realtime demand signal is made – but the ability to pre-emptively certify the factory, as opposed to individual products, will massively speed up

elding, so long as assurers and accreditors are bought in from the earliest possible point.

The ‘so what’ to all of this is the prize of true, digitally enabled Agile Combat Employment, but this will only deliver the true bene ts it seeks if it is digitally enabled from the o . Dispersed and relocating forces must be able to access critical information at all stages of the ght, be that during tasking, programming, planning or when ghting. Multiple assured pathways will be required, including terrestrial and satellite communications and resilient data links. The providers of these services need to be as agile and survivable as the war ghters at the edge.

When we have achieved digital enablers that are as seamlessly integrated as a WhatsApp for mission planning, an Amazon for logistics and an Uber for friendly force disposition, we will be capable of dispersed operations that can strain and break the enemy kill chain across every domain, while at the same time reinforcing our own ‘survive chain’ and resilience. During peacetime, the prize is the ability to avoid vendor lock-in that has often plagued procurement e orts. This will hopefully allow nations to procure more con dently and consistently, in turn strengthening allied industrial bases for when they are really needed.

We all know that ‘don’t be there’ is a key tenant of survival and is being practiced every day in Ukraine. Achieving it at a global scale requires us to ensure that operations can occur from wherever assets are based, exing and adapting in real time as required. We now have the digital tools to enable this. We should put them to use.

MDI requires digital enablers that are seamlessy integrated across the entire force (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

The Agile Combat Employment (ACE) concept aims to enable the RAF to operate from a greater number of locations, providing increased agility, exibility and resilience. Group Captain Jason Payne, No 11 Group’s Deputy Assistant Chief of Sta , tells Jim Winchester how the RAF is developing ACE and how it intends to deliver it for operations

Typhoons deployed from RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus to an undisclosed base in the Middle East to test the ACE concept as part of Exercise Blue Dragon (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

In the last two years, the RAF’s Agile Pirate and Blue Dragon exercises have seen Typhoon fast jets deploying away from their main operating bases to Stornaway in the Hebrides and to a forward location in the Middle East. Group Captain (Gp Capt) Jason Payne explains: “It has basically been a crawl, walk, run approach to ACE, where we piggyback o existing exercises or deployments in order to be able to experiment with how we want to take ACE forward.” He continues, “We are