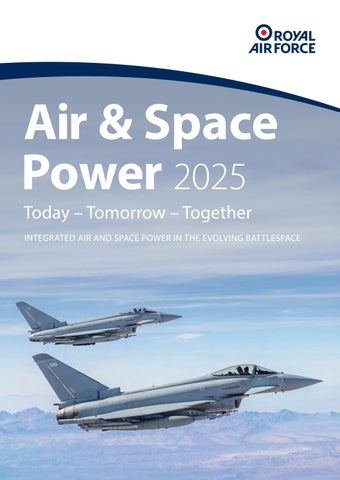

Power 2025

INTEGRATED AIR AND SPACE POWER IN THE EVOLVING BATTLESPACE

Ready to respond

Richard Hamilton, Managing Director Europe & International, BAE Systems, discusses the critical role that industry must play to respond to the ever-changing global threat and the importance of sovereign defence capability

Creating an F-35 culture

Lieutenant General André Steur, Commander of the Royal Netherlands Air and Space Force, highlights how the growing worldwide community of F-35 operators is creating an innovative culture of allies ready to ‘Fight Tonight’, ‘Fight Tomorrow’ and ‘Fight Together’

Integration – the right stu ?

Air Marshal Allan Marshall, the RAF’s Air and Space Commander, reveals how lessons from current con icts in Ukraine and the Middle East are helping the RAF to enhance its ability to defend the homeland and deliver operations overseas

Air Vice-Marshal Mark Flewin, Air O cer Commanding 1 Group (at time of writing), on the Typhoon Force’s readiness to deliver the UK’s Quick Reaction Alert tasking and ability to intervene at a moment’s notice

Air Marshal (Retd) Greg Bagwell, CB CBE FRAeS, President of the Air & Space Power Association, considers the advantages of integrating existing capabilities with tactics and innovation

Underhill:

airdrops in Gaza

Air Commodore Dan James, the RAF’s Air Mobility Force Commander, reveals the complexities of the aid operation to drop food and provisions to the people in Gaza and how it has evolved since the rst drop was made in March 2024

43

C-UAS at the Paris Olympics

Flight Lieutenant Ben Protheroe, Second in Command, 34 Squadron RAF Regiment, highlights the extraordinary Anglo-French collaborative e ort to counter drones during the 2024 Paris Olympic Games

46

Maximising cohesion and interoperability

Lieutenant General Simon Hamilton, Deputy CEO of Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S), outlines the organisation’s strategy for delivering integrated capability across air and space

48

52

Protector RG Mk 1 (MQ-9B) –introduction to service

The RAF’s ISTAR Force Commander, Air Commodore Nick Paton, o ers an update into the work being undertaken to introduce the Protector RG Mk 1 RPAS (MQ-9B) into service at RAF Waddington

UK air e ectors: now and the plan for the future

Air Commodore Alun Roberts highlights the requirement for a transformative planning and development roadmap in the crucial area of airlaunched missile systems and other air e ectors

55 The high-low weapons mix: a view from industry

Tom Wallington, head of the Air Domain for UK Sales and Business Development at MBDA, explains the opportunities that a high-low mix of weapons systems can deliver in terms of performance, time and cost

58

Spectrum warfare

Controlling, developing and using electro-magnetic technologies is one of the dark arts of modern warfare. Air Commodore Blythe Crawford, former Commandant of the Air and Space Warfare Centre, highlights the current status of the UK’s capabilities

Tomorrow – the changing character of war

62 The future operating environment

Air Vice-Marshal Mark Ridgway, Director Defence Futures, outlines the expected changes that will feature in the future operational environment and how UK Defence will need to adapt to address them

66

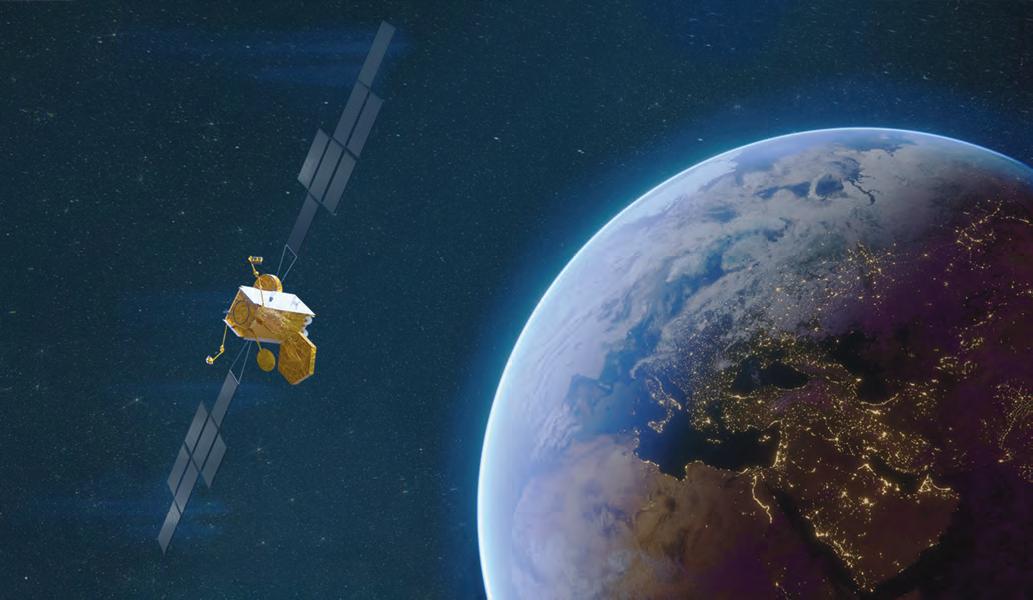

Creating the UK Defence space war ghter

As the UK continues to grow its space capabilities,

Air Commodore Jamie Thompson, Deputy Commander Space Command, highlights the qualities, aptitudes and expertise that the future space war ghter will need 70

Future control of the air

Air Vice-Marshal Jim Beck, the RAF’s Director of Capability and Programmes, outlines the future challenges in achieving control of the air and highlights the role that autonomous collaborative platforms and the NEXUS combat cloud might play 73

Ethics in global competition over military AI

James Black from RAND explains how advances in arti cial intelligence (AI) and related technologies are introducing complex ethical debates

76

Exploiting data to achieve control of the air

The RAF’s Director Digital, Dr Arif Mustafa, explains why the explosion in data acquisition and storage requires a step change in technological infrastructure and skill sets to ensure this huge resource can be used to gain operational and strategic advantage 78

The Strategic Defence Review –recognising industry’s key role

Kevin Craven, Chief Executive O cer of ADS, on how industry helped to formulate the Strategic Defence Review and will go on to support its implementation 82

Higher airspace operations

Brigadier General Alexis Rougier, general o cer in charge of very high altitude at the French Air and Space Force headquarters, considers a new strategic challenge for Defence – aerial vehicles capable of operating in the upper reaches of the atmosphere 86

Future infrastructure

Air Commodore Will Dole OBE, Head of RAF Infrastructure, explains the need for understanding, embracing and preparing for the changing character of war, so the RAF’s infrastructure can adapt in time

89 Ramstein Flag

Deputy Commander NATO Allied Air Command, Air Marshal Sir John Stringer, describes the purpose, ambitions and outcomes of this new training series, which rst gathered RAF Rivet Joint ISR aircraft and associated personnel in October 2024

92 Together – Pitch Black

Air Marshal Stephen Chappell, Chief of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), explains why Exercise Pitch Black is the RAAF’s most signi cant ying activity for enhancing its ability to work with partners

96 Operation Highmast

Rear Admiral Anthony Rimington highlights the ambitious deployment of UK Carrier Strike Group 2025 to the Indo-Paci c alongside international partners

100 Recruitment and Retention: where next?

Air Vice-Marshal Simon Edwards, the RAF’s Director People and Air Secretary, on the impact of changes to the RAF’s Recruitment and Retention processes

104 Ukrainian ying training

Air Vice-Marshal Ian ‘Cab’ Townsend, the Air O cer Commanding 22 Group, explains Ukrainian pilots’ training with the RAF’s 22 Group and the signi cance of the RAF’s support to the Ukrainian Air Force

108 A resilient edge: RAF Reserves at the heart of the Whole Force

Air Vice-Marshal Ranald Munro, Commandant General of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force, lays out the steps required to achieve the RAF’s vision of an integrated organisation that comprises regular and reserve aviators alongside civilian and industry personnel

Air & Space Power 2025

INTEGRATED AIR AND SPACE POWER IN THE EVOLVING BATTLESPACE

Editor Simon Michell

Project Managers Gp Capt John Shields, Director Defence Studies (Air); Wg Cdr Amanda J Scarth, Deputy Director Defence Studies (Air)

Editorial Director Barry Davies

Managing Director Andrew Howard

Printed by Micropress

Front cover image: Cpl Nathan Edwards

Published by

Chantry House, Suite 10a High Street, Billericay, Essex CM12 9BQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 1277 655100

On behalf of the Royal Air Force Ministry of Defence Main Building, Whitehall, London SW1A 2HB, UK www.raf.mod.uk

Lifetime engineering

We approach everything with a broader perspective. Forging close and committed partnerships with our customers, to deliver defence engineering that creates their big picture. Resulting in assets that work. And work hard. Year after year.

The Rt Hon

John Healey MP

Secretary of State for Defence

Making Britain safer: secure at home and strong abroad

Through the years, the RAF has defended the UK homeland, policed the skies above us and protected the Euro Atlantic with outstanding success and total professionalism.

Now our world is changing. The threat we face is more serious and less predictable than at any time since the Cold War. War in Europe, growing Russian aggression, emerging nuclear risks and daily cyber attacks at home. We are in a new era of threat, which demands a new era for UK defence.

The theme of this edition of Air and Space Power –integration in an evolving battlespace – is a timely one.

The recently published Strategic Defence Review (SDR) sets out a vision for the next decade and beyond for how UK Defence will transform to meet the challenges of a more dangerous world across every domain. In a landmark shift for

UK defence and deterrence, we are moving to war ghting readiness to deter threats and strengthen the Euro Atlantic. By committing the largest sustained increase in defence spending since the Cold War, we will end the hollowing out of our armed forces and, instead, lead in a stronger NATO.

The RAF gives us the capacity to strike anywhere, at any time. Yet – as the SDR states – over the next two decades, we and our allies will have to compete harder for air control and ght in a way not seen for over a generation, due to technological shifts.

With the return of state-on-state con ict in Europe, we must build greater war ghting readiness by exploiting the opportunities a orded by advanced technologies. The future of the RAF rests on adopting the latest innovation. That is why we will create the next-generation RAF, with F-35s, upgraded Typhoons and the Global Combat Air Programme.

The RAF has consistently and unwaveringly responded to calls to action – be that patrolling the skies of the eastern European ank or protecting our home waters from malevolent actors (PHOTO: MOD/CROWN COPYRIGHT)

To match the changing nature of warfare, we will transition to a combination of crewed, uncrewed and autonomous platforms. The introduction of StormShroud marks the rst of a new family of Autonomous Collaborative Platforms, which will give the RAF the advantage in the most contested battlespaces. We will increase our resilience by improving existing infrastructure. And our armed forces will be more lethal than the sum of their parts by implementing an Integrated Force model.

An unshakeable commitment to NATO

The UK’s strategic strength comes from our allies. Our unshakeable commitment to NATO means we will never ght alone. That’s why our defence policy will be “NATO rst”. The war in Ukraine has taught us whoever gets new technology into the hands of their armed forces fastest will have the advantage. In response, we will place Britain at the leading edge of innovation in NATO by doubling investment into autonomous systems to £4bn this parliament, investing more than £1bn in an integrated Digital Targeting Web and nancing a £400m UK Defence Innovation Organisation. The SDR also begins a new partnership with industry, innovators and investors that will enable the UK to continually innovate at wartime pace. For members of our RAF, this will mean they receive the kit they need to protect our nation, when they need it. And for communities across the UK, the government’s increased defence investment will be an engine for growth, bringing a ‘defence dividend’ in support for British jobs, business and innovation.

The SDR rightly recognises space as a domain of growing competition and increasing importance. Nearly 20% of our national economy is reliant on satellite services, while both Russia and China are expanding their satellite eets and seeking to weaponise the domain. We will enhance the resilience and develop the capabilities of our military space systems. And space will be an important technology portfolio for the National Armaments Director.

Technology is vital, but an Air Force is nothing without its people. As Defence Secretary, every time I have called on members of the RAF to act – whether to strike against the Houthis in the Red Sea or protect our waters from Russian spy ships – they have not only met the moment, but risen above it. They do our nation proud. In return, we must do better by them.

The SDR places people at the heart of defence plans. And this government is committed to renewing the contract with those who serve. That is why we awarded personnel the largest pay rise in two decades and why we are investing more than £7bn to improve military accommodation this Parliament. And in the coming years, we will do more and more to recruit and retain talent.

Britain has always maintained air power by staying ahead. We have everything we need to succeed in this more dangerous world – innovative technology, advanced tactics and the very nest people. Now we must evolve once more to make Britain safer: secure at home and strong abroad.

delivering game-changing capability across the raf

Our commitment to the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force faces increasingly complex engagement scenarios where there is no room for error. In this demanding environment you can count on our expert teams who are committed to bringing you cutting-edge, sovereign, combat-proven technology. ASRAAM, Brimstone, Storm Shadow, Meteor & SPEAR family are capabilities the RAF can rely on to meet the operational needs of the modern battlespace.

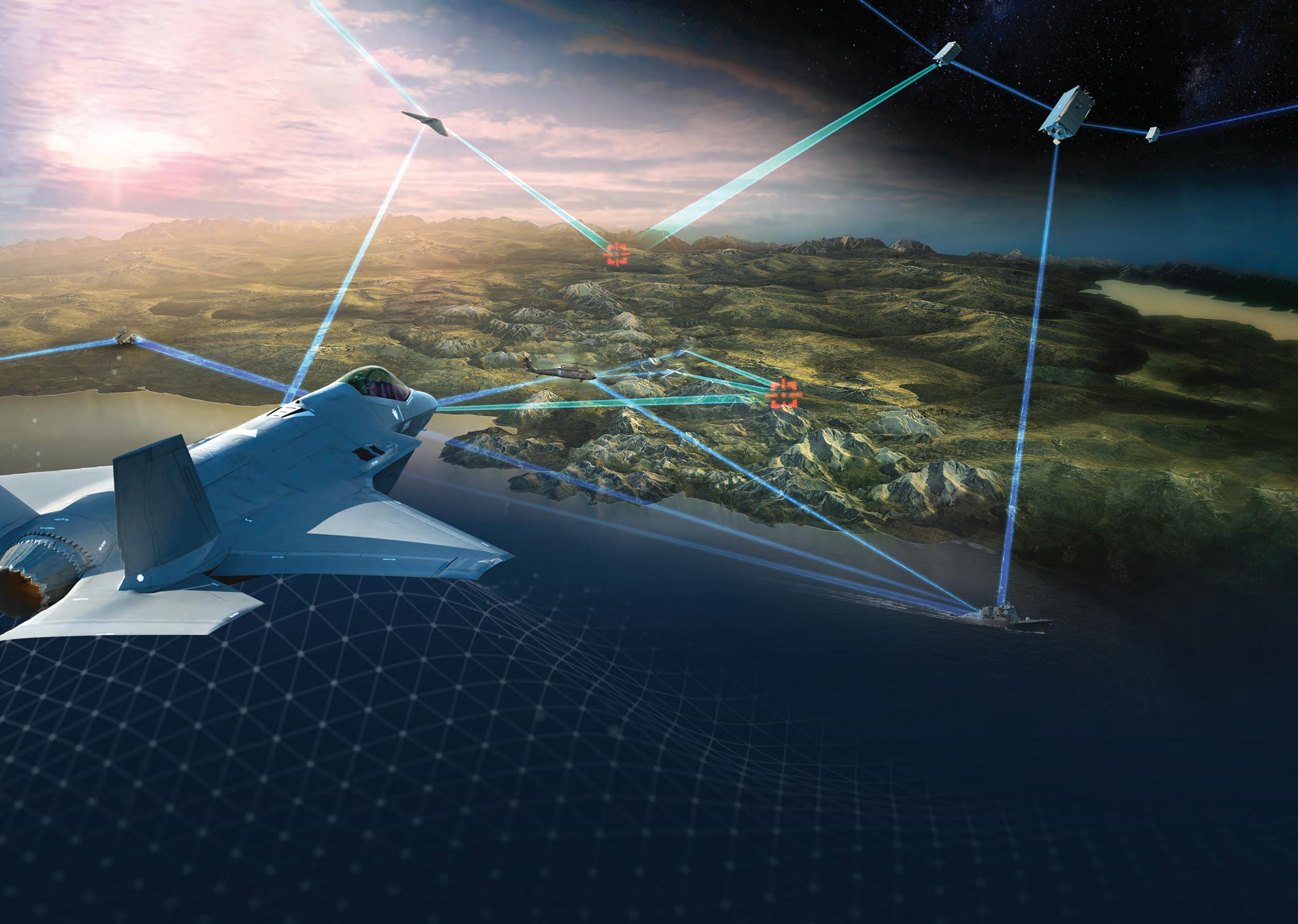

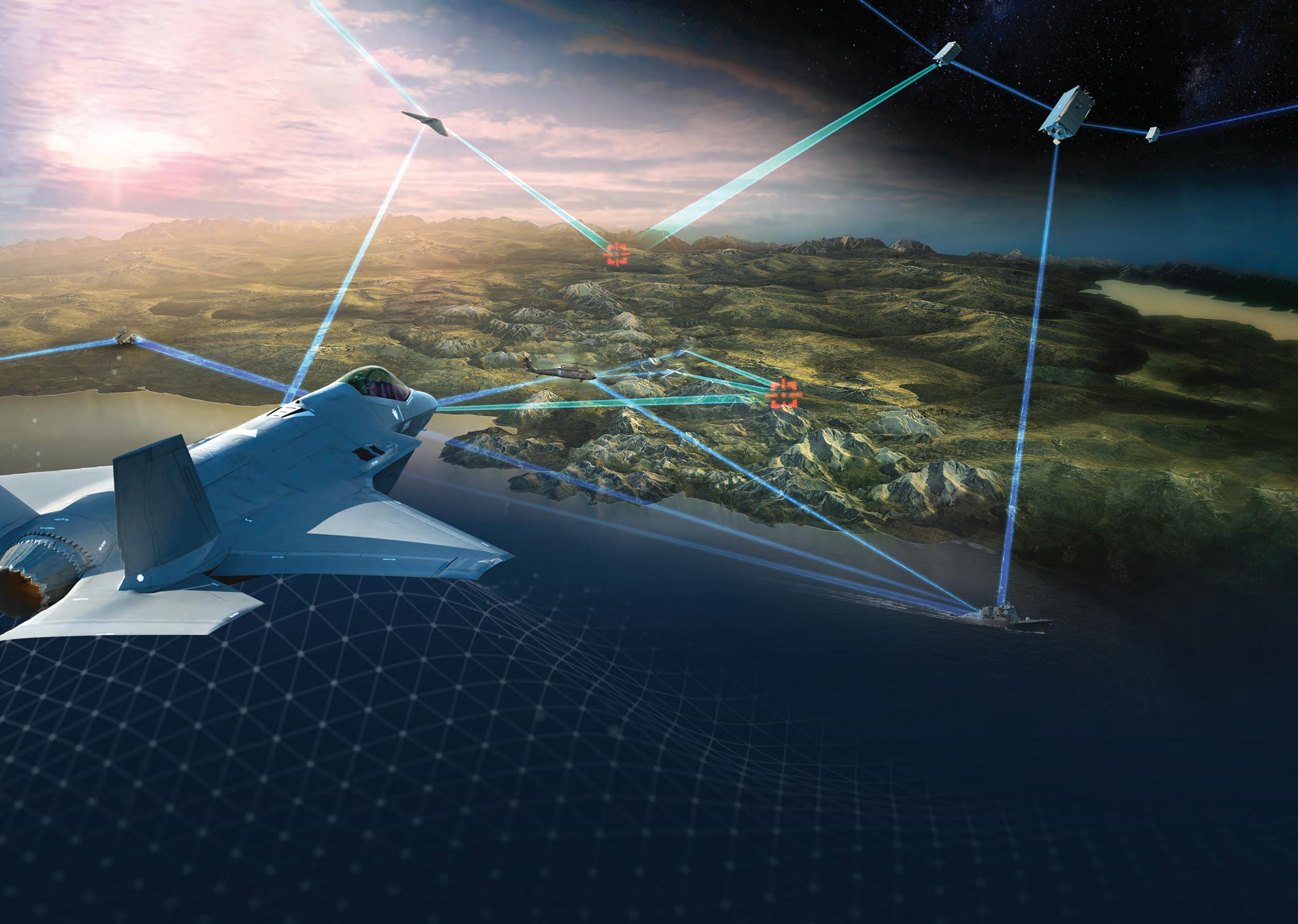

SEEING THE BIG PICTURE MEANS CONNECTING EVERY DOMAIN

The future battlespace calls for future-forward solutions.

Whether the battle takes place over land, on the sea, through the sky, in space or across cyberspace, the F-35 partner team of Lockheed Martin, BAE Systems, Northrop Grumman and RTX keeps you connected across every domain to help protect what matters the most.

Training solutions

Taking training to the next level –taking your people to their highest level

International turnkey solutions for mission-critical aircrew training

Come and see us and our UKMFTS training aircraft at the Royal International Air Tattoo

Design Develop

Deliver

Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard Knighton

KCB ADC FREng, Chief of the Air Sta

Today, Tomorrow and Together

Welcome to this, the 2025 edition of Air and Space Power, the theme of which is integrated air and space power in the evolving battlespace. This is an opportune moment to consider the need for even greater levels of integration in the air and space domains. We only have to watch our news outlets or look at social media feeds on a daily, if not hourly, basis to realise that the world is changing rapidly around us.

The threat we face today is palpable. However, the combined strength in both the quality and quantity of allied air power provides e ective deterrence and campaign-winning options for our collective security. It is the enduring need to integrate these constantly changing capabilities that delivers competitive advantage beyond the sum of its parts and demonstrates

allied cohesion. Consequently, as the nation’s rst responders, it is vital that we invest time, money and e ort to continually integrate air and space power to harness that strength and deliver the required e ects today, tomorrow and together.

Today

In 2025, the world remains a volatile place. Over the last 30 years, we have enjoyed the peace dividend born out of a Cold War victory and a focus on counterinsurgency operations, ghting far from home, with a secure home base, no existential threat to our nations, and with limited impact on the national purse. Today, we face multiple and multiplying threats. War has returned to the European continent, instability endures in the Middle East, and the US’s pivot to the Indo-Paci c

and its hard rhetoric are now unambiguous. The world has changed, and great power competition is back on the agenda. As the UK Prime Minister, Sir Keir Starmer, said recently:

“We must recognise the new era we are in, not cling hopelessly to the comforts of the past.”

Now, more than any other time in our careers, air and space power is needed to secure our nation, our interests and our way of life.

Tomorrow

Today’s RAF is the most modern and most capable it has ever been. Over the last decade, we have seen a major recapitalisation of our front-line capabilities. World-class capabilities, such as the F-35B Lightning, A400M Atlas, P-8 Poseidon and RC-135W Rivet Joint have all joined the front line, working alongside the combat-proven multi-role capabilities of Typhoon.

While the RAF will soon add E-7 Wedgetail and Protector to that front-line portfolio, there are no major equipment programmes planned for the next 15 years. We have what we have for the near and medium term. To stay ahead of the threat, we must continue to adapt and innovate to maximise our lethality. This is a de ning moment for our generation, but our nation and its allies and partners have been here before, and we are not starting from scratch. As the Italian air power theorist, Giulio Douhet, stated:

“Victory smiles upon those who anticipate the change in the character of war, not upon those who want to adapt themselves after the change occurs.”

We must continue to develop, deliver and eld campaign-winning air and space power capabilities that our allies and partners admire and our enemies fear. We have a eeting opportunity to make the necessary changes.

Together

We cannot do it alone. Air and space power are team games; they always have been, and it remains true both for today and tomorrow. In 2024, the RAF operated alongside 44 partner

nations. We continue to work together tactically, operationally, strategically and politically. In Australia last year, we put the sage advice of Adolf Galland, the German ghter ace, into practice:

“One of the guiding principles of ghting with an air force is the assembling of weight, by numbers, of a numerical concentration at decisive spots.”

The RAF deployed 8,500 miles to Northern Australia to participate in Exercise Pitch Black – a three-week largeforce employment exercise. We worked alongside 20 allied nations with over 140 aircraft and 4,500 personnel. This is only one of many exercises that we can exploit to enhance our ability to work together. Interoperability is more than just an overseas exercise; it is about a multitude of factors that we can bring to bear to make us y and ght better together. By working together, from aircraft cross-servicing to exchange tours to multinational procurement programmes, we create greater interoperability and provide ourselves with a greater chance of success in future con icts. We must remain integrated into one team to meet the challenges of the evolving battlespace. It is a never-ending quest for excellence.

Throughout the pages of Air and Space Power 2025, the challenges and opportunities will be explored in more detail. I hope it stimulates ideas, leads to debate and tangible concepts of how we can integrate more e ectively. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the French WW2 combat pilot, said:

“The time for action is now. It’s never too late to do something.”

We have the capability, the intent, the opportunity and, most importantly, the need to strengthen and focus what we have. Now is the right time to do something. I look forward to engaging with those responsible for developing, delivering and sustaining global air and space power today, tomorrow and together. Fight’s on!

POWERING RPA INNOVATION FOR THE WORLD’S TOUGHEST MISSIONS

We deliver remotely piloted aircraft innovation powered by experience, ingenuity, and performance — backed by world-class partners.

This means unmatched pole-to-pole strategic armed ISR from the multi-mission, longendurance Protector. For maritime requirements, a short takeoff and landing kit brings Airborne Early Warning capabilities to aircraft carrier operations in the form of Sea Protector. And for the best all-domain awareness deep within the battlespace, look to our jet-powered Gambit Series Autonomous Collaborative Platforms.

These next-gen solutions deliver affordability at scale for any mission anywhere. And they’re ready today.

With an unparalleled range of solutions – from networked platforms to advanced sensors and thermal management – weʼre equipping pilots with a distinct advantage, before the mission even begins.

Learn more at rtx.com

Simon Michell

Editor, RAF Air & Space Power 2025: Today – Tomorrow – Together

Facing multiple and multiplying threats

The purpose of the RAF Air & Space Power publication is not only to inform the readership about the RAF’s activities, but also to stimulate new ideas by delivering trusted information that enables informed discussion. Never in my lifetime has this been more important. In his foreword to this issue, the Chief of the Air Sta , Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Sir Richard Knighton, points out that as a nation and a founder member of NATO we face, “multiple and multiplying threats”. With a brutal and extraordinarily destructive war now taking place on European territory, the days of the peace dividend are well and truly over. In the words of the new NATO Secretary General, Mark Rutte, “We are not at war, but we are not at peace either”.

Fight Tonight, Fight Tomorrow, Fight Together

As the UK’s rst responders, the RAF is now being asked to patrol European skies from the arctic to the Mediterranean –an onerous task that is expertly explained by Air Vice-Marshal (AVM) Mark Flewin in his article on ‘Typhoon – long-range rst responders’. For the RAF, the Typhoon bears the heaviest burden in this tasking, but as the F-35 eet continues to

grow across the UK, Europe, the US and the Indo-Paci c, the Lightning is becoming absolutely critical to the defence of the western world. The Commander of the Royal Netherlands Air and Space Force, Lieutenant General André Steur, o ers an intriguing glimpse into the growing F-35 community and reveals how it is creating an innovative culture of allies ready to ‘Fight Tonight’, ‘Fight Tomorrow’ and ‘Fight Together’.

As instability in the Middle East threatens to spill over into the wider region, the con ict in Gaza highlights the need to be able to deliver humanitarian aid into contested and potentially hostile areas. Air Commodore (Air Cdre) Dan James’s fascinating article on how the RAF and partner air forces managed to drop food and medical supplies onto tiny strips of the Gazan Mediterranean shoreline is both inspiring and alarming.

It is proof, if proof were needed, that today’s con icts impact the civilian population as hard, perhaps even harder, than they impact the military. Ukraine is another example of this. Russia continues to target civilians in their homes and while they go about their daily activities. In truth, in today’s wars, nowhere is safe.

The drone-centric nature of the Ukraine con ict shines a light onto an evolution in warfare that no defence ministry can

The RAF’s ability to deliver humanitarian aid in times of crisis is a justi able source of pride (PHOTO: MOD/CROWN COPYRIGHT)

a ord to ignore. The battle of the drones highlights, in undeniable terms that, at times and in certain areas, control of the airwaves is equally as important as control of the air. This is critical, as AVM Jim Beck explains in his article on ‘Future Control of the Air’.

The established expectation that the RAF and its allies would enjoy air superiority in future con icts is an outdated notion. Control of the future airspace during times of con ict is likely to be local and eeting. Likewise, control of the airwaves will be di cult to achieve and retain. Air Cdre Blythe Crawford, former Commandant of the RAF’s Air and Space Warfare Centre, writes in his piece on ‘Spectrum Warfare’, “Whoever owns the spectrum, owns the battle eld. Essentially, those who are not adept at, and continually adapting and innovating, electronic countermeasures and spectrum warfare will always be on the back foot. This is a form of combat that needs to be at the very heart of every military capability.

Sharing future vision

The Chief of the Air Sta ’s Global Air and Space Chiefs’ Conference is at the forefront of cohering partner air forces and sharing ideas, concepts and future vision. As ACM Knighton reminds us, “We must remain integrated into one team to meet the

challenges of the evolving battlespace.” The emergence of a new exercise, Ramstein Flag, is testament to the continuing e ort to ratchet interoperability between allies up a notch.

At the other end of the world, another exercise – Pitch Black, which has been going for over 40 years – highlighted Australia’s strategy of ‘Denial’. Both exercises are covered in detail in this issue. Moreover, we are indebted to the Chief of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Air Marshal Stephen Chappell, for his excellent article on Pitch Black, as it not only explains Australia’s inaugural National Defence Strategy, but also how exercises like Pitch Black support and drive that strategy.

What these exercises also highlight is that an alliance of like-minded nations should always seek to nd new friends and welcome potential partners. The training of Ukrainian F-16 pilots by a coalition of the willing is a prime example of this.

Air Vice-Marshal Ian ‘Cab’ Townsend, the Air O cer Commanding the RAF’s 22 Group, highlights the e orts that the international community is making to help Ukraine defend its territory and airspace against a callous and brutal opponent. It is also an example of how the RAF, in particular, is ready to ght today, tomorrow and together.

The latest generation engine for latest generation fighter aircraft

The demands of military aviation in the 21st century leave no room for compromise – or outdated solutions. With cutting-edge technology and unrivalled build quality, the EJ200, installed in the Eurofighter Typhoon, has proven time and again to be the best engine in its class. To find out more about our market-leading design and unique maintenance concept, visit us at www.eurojet.de

The EJ200: Why would you want anything less?

Contemporary lessons of air power

Air Marshal Allan Marshall, the RAF’s Air and Space Commander, reveals how lessons from current con icts in Ukraine and the Middle East are helping the RAF to enhance its ability to defend the homeland and deliver combat and humanitarian operations overseas

TUncrewed systems, such as the SPEAR-EW airborne jammer (pictured), are now core e ectors on the battle eld and beyond

(IMAGE: MBDA)

he modern geopolitical context and recent con icts – from Ukraine to the Middle East and beyond – o er a wealth of insights and lessons across all war ghting domains. From an air power perspective, few of these are entirely new. However, many have been reinforced; the pace of technological change has outstripped expectations in several areas, and we are reminded of fundamentals that have somewhat fallen into abeyance due to the bias towards expeditionary operations in largely uncontested airspace over previous decades.

What is clear is that contemporary con ict has reasserted the pivotal nature of air power, which continues to deliver substantial e ect across all of its doctrinal roles. Among the plethora of lessons

available, this article will focus on some insights that are likely to shape future thinking on air power. Critically, it opens with an enduring lesson and a stark reminder of how wars unfold in the absence of control of the air.

Control of the air remains foundational, but is becoming more complex to achieve Control of the air has long been a prerequisite for joint operational success. It allows unhindered operation of air, land and maritime forces, providing signi cant advantage. The con ict in Ukraine serves as a clear case study to this e ect, where the inability of either side to truly control the air has severely impacted ground manoeuvre, reduced survivability and resulted in a relatively static and

highly attritional con ict. This lesson should serve as a clear reminder that control of the air is not just foundational for air forces, but across all domains. With increasingly sophisticated air-defence networks, proliferated sensors, longer-range e ectors, rapid advancements in uncrewed systems and a testing electromagnetic environment, achieving control of the air is becoming increasingly challenging. Adversaries are adapting quickly: developing technologies, integrating uncrewed systems and harnessing a wide array of sensors and data. Ensuring our decision advantage is therefore essential, and maintaining an overall advantage will demand relentless focus. Finally – and it has been said before –it may be necessary to accept that assured control of the air may only be achievable on a temporary basis in time and space, rather than on a persistent basis.

Uncrewed systems are increasingly ubiquitous, e ective and central

The rapid proliferation and technological development of uncrewed systems has already had a signi cant impact on the air environment. No longer novel or peripheral, these systems are now core e ectors conducting ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance), strike, electronic attack, deception, communications and more. The rapid development cycles alongside the a ordability and adaptability of uncrewed systems have made their employment appealing across the full spectrum of con ict. These factors have also somewhat ‘democratised’ the delivery of air power, a ording non-state actors access to a level of e ects previously only accessible to nation states. This proliferation provides defensive dilemmas in terms of countering such systems, as can be seen in Ukraine, where hypersonic weapons are integrated into the same attack as very low-cost systems in signi cant volume. There is also a necessity to counter uncrewed threats without expending expensive exquisite munitions. This will likely result in our use of uncrewed systems in a high-low defensive capability mix.

Concurrently, our air forces must also harness uncrewed technology to maintain operational advantage, delivering our ISR and o ensive e ects with creweduncrewed teaming, autonomous mission execution, and exploiting the potential to mass large swarms.

The importance of electronic warfare and spectrum dominance

Over recent decades, which were dominated by expeditionary warfare and a focus on counterterrorism, electronic warfare (EW) development and expertise was deprioritised in many nations. However, recent con icts with a higher level of contestation in the air have reminded

us of the criticality of this area of military business. The density of the electromagnetic environment in areas of Ukraine is beyond anything seen in previous con icts, severely challenging situational awareness and the ability to both defend and deliver o ensive e ect. From disrupting GPS signals to denying radar and C2 networks, spectrum operations directly impact mission success. The ability to jam, deceive or deny adversary systems is proving decisive; hence the ability to understand, operate within and a ect the EW environment is fundamental and a worthy priority for any air force.

Air defence alone is insu cient

The contemporary environment has seen air attack used routinely to disrupt, defeat, deter and/or coerce, including near-nightly attacks against Ukraine and episodic strikes within the Middle East. The breadth of the air-defence system that Ukraine has developed, ranging from mobile machine-gun teams through to Patriot missiles, combined with images demonstrating the impressive performance of Israel’s defensive systems, focuses the mind on the requirement for such capabilities. Many nations are prioritising enhancement in Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD); however, there is risk that this investment comes at the cost of the ability to deliver o ensive action to deter adversaries from launching or persisting with such attacks. So, while robust air defences are evidently necessary, on their own they are not enough to ensure strategic stability or operational success.

Israel’s Iron Dome air-defence system is an example to be emulated (PHOTO: DPA PICTURE ALLIANCE/ALAMY)

Agile Combat Employment skills are required in every modern air force (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

Massed drone and missile attacks can overcome or rapidly exhaust even advanced defensive systems, either through the scale of a single attack or the erosion of defensive stockpiles over time. Credible deterrence relies on the ability to impose cost, disrupt momentum and shift initiative – ie to ‘shoot the archer’ and not just to defend. The roles of strike, o ensive counter-air and suppression of enemy air defences therefore remain essential and must attract a healthy balance of investment.

The prevalence of adversary air attacks of recent years also reminds us to look to the past for best practice in terms of resilience and agility in war ghting. Camou age, concealment and dispersal are rightly back in vogue, and while airbases remain relatively resilient and can be repaired, modern air platforms appear to be becoming increasingly fragile and cannot as easily be repaired or replaced following damage or loss. The focus on Agile Combat Employment, across Europe and beyond, is therefore a necessity.

Endurance, stockpiles and scale matter

Recent experience has revealed that many modern forces lack the depth and resilience to sustain hightempo operations over time. Munitions shortages, limited spare parts and wider fragility have emerged as critical limitations, and the ability and timescales

for reactive replenishment from industry have often neither met assumptions nor demand. The rate and overall scale of munition usage in the Ukraine con ict, now over three years in, provides a salient reminder of the depth of magazine required, and highlights the unwelcome reality that wars often last longer than convenient assumptions might suggest.

Lessons about sustainment and resilience are far from new, but there remains a tendency for planners to focus on the opening stages of con ict, rather than the enduring campaign. Investment in an ability to endure is expensive and does not routinely have the appeal to generate political and public interest. However, it is non-discretionary and a determinant of strategic credibility and successful deterrence –therefore, sustainment deserves re-energised focus.

Integration – joint, international and industrial

Air power’s e ectiveness increasingly depends on its ability to operate seamlessly across all domains and with a broad spectrum of partners. Integration is required not only between air, land, maritime, space and cyber capabilities, but also across international and industrial boundaries. Synchronised operations enhance tempo and generate combined e ects greater than the sum of their parts.

Internationally, partnerships and alliances enable burden-sharing, aggregation of forces, collective deterrence and much more. Equally necessary is integration of defence industry, into planning cycles and capability development to ensure timely delivery and sustainment of cuttingedge technology. Adversaries are actively exploiting seams – whether between domains or nations, or within supply chains – making it essential that air forces are fully integrated from the outset. This is a strategic imperative that must be embedded in mindset, planning, procurement and practice.

Air and space power’s critical role

The contemporary operating environment has rea rmed air power’s critical role, while highlighting the need to adapt to evolving threats and technologies. Control of the air remains essential, but will require signi cant and persistent e ort to maintain advantage within an increasingly contested environment. The rise of uncrewed systems, the resurgence of electronic warfare and increased availability and exploitation of data must all be embraced, exploited and defended against. Crucially, resilience, agility, the ability to sustain operations and further integration in its many forms must also be prioritised to assure both deterrence credibility and war ghting success. These are not theoretical lessons – they are unfolding in real time.

Strengthening defence

Simon Barnes Managing Director, BAE Systems Air

Has the changing geopolitical environment changed the way in which you operate?

Yes, today’s uncertain world has underlined the importance of the partnerships we have with all our customer air forces. We take seriously our responsibility to meet the changing threat environment and evolve the range of products and services we o er to match our customer needs, and it is through our partnerships that we can do this e ciently and e ectively.

As an example, our response to NATO requirements in Eastern Europe saw us working alongside the RAF to bring forward immediate upgrades to its Typhoon eet, ensuring it has what it needs to remain the backbone of NATO’s response to Russian aggression.

As the war in Ukraine has demonstrated, uncrewed technologies are providing operational advantages, prompting the armed forces to prioritise this capability and its integration into existing air, land and maritime operations. We’re responding to these demands by increasing the pace and agility of the services we provide.

Through partnerships with SMEs and academia we can not only deliver capability, but also fuel innovation and elevate the UK’s position on the world stage. We provide the stability to manage complex projects with the agility of working with smaller companies, supporting defence resilience and bringing capability rapidly to the front line.

What role can industry play in ensuring the UK’s sovereign defence?

As one of the very few nations with the ability to design, manufacture and bring into service complex combat aircraft and capabilities, the UK recognises sovereign combat air as a strategic asset and a crucial advantage in an uncertain world. This military necessity is only as strong as the industry, innovators and investors that stand behind it.

Sovereign defence plays a vital role in defending our way of life, and we protect and sustain our sovereignty through a vibrant ecosystem with SMEs, academia and the wider industrial base, working with more than 1,400 UK suppliers. We are the critical partner in delivering and sustaining critical sovereign technologies and infrastructure that meet the objectives of the UK and its allies.

The signi cance of strong European defence has grown. Do you have a part to play there?

Absolutely, we’re truly embedded in European defence and securing its sovereignty through partnerships such as Euro ghter and MBDA, which sit at the heart of European defence collaboration. Euro ghter Typhoon provides the backbone of European air defence and defends NATO borders every

day. Euro ghter helps strengthen the political, military and industrial ties that are vital in Europe’s response to the changing environment and underpin over 20,000 jobs in the UK alone.

Through the Global Combat Air Programme we are partnering with Italy, alongside Japan, representing another opportunity to grow these strong mutually bene cial ties with European allies and further a eld. Interoperability with key allies remains a crucial part of European e orts to tackle increasing threats, strengthen NATO and boost security.

What other bene ts does strong sovereign defence capability bring to the UK?

Defence has been identi ed as a driver of economic growth by the UK Government and, as one of the UK’s largest employers, we’re committed to playing our part investing in boosting productivity, e ciency and prosperity. Through long-term investment in programmes such as Typhoon and Tempest we have also been able to drive e ciency. For example, our work on innovative support to the RAF’s Typhoon eet has increased availability, while also driving huge savings that have enabled investment elsewhere.

All of this contributes to the national growth agenda through a highproductivity sector with our productivity standing more than 15% over the UK average, boosting the nation’s global competitiveness. More than the physical equipment and services we deliver, sovereign capability creates a lasting ripple e ect, helping to contribute to economic growth, supporting international relationships and driving export bene ts.

Typhoon: long-range first responders

Air Vice-Marshal Mark Flewin, Air O cer Commanding 1 Group (at time of writing), highlights the Typhoon Force’s constant readiness to deliver the UK’s Quick Reaction Alert tasking, while also being able to intervene at a moment’s notice across the globe

Some 18 years since its rst assumption of Quick Reaction Alert duties, Typhoon continues reliably to excel in the RAF’s foundational and essential role of securing and defending the nation’s skies. Still second only to F-22 among western ghters in raw performance, the aircraft remains world-class in its air defence mission as it reaches midlife in RAF service. Whether intercepting Russian long-range aviation or non-

communicating airliners in crowded airspace, Typhoon has earned a deserved reputation for excellence as the UK’s rst responder to airborne threats.

Defending the homeland

Keeping aircraft and pilots poised for action at a moment’s notice at RAF Coningsby, RAF Lossiemouth and in the Falkland Islands is a considerable task, xing more resource than might be assumed. Yet

Typhoon has been heavily tasked overseas for much of its service, putting an early interim air-to-surface capability to highly e ective use during NATO’s Operation Uni ed Protector mission over Libya. Later, the hastily mounted Operation Luminous deployment to Akrotiri helped to deter Syrian aggression against the Sovereign Base Areas at the height of tension over abortive strikes on chemical weapons facilities. Mounting combat air patrols at the end of the transit from RAF Coningsby, and quickly conducting air defence integration exercises with French, US and Royal Navy ships operating in the area, Typhoon’s sudden and highly visible presence had the desired strategic e ect during its rst short operational visit to Cyprus.

Counter-Daesh operations in the Middle East

As the tenth anniversary of the Operation Shader detachment draws near, it is worth recalling that Typhoon’s long second stay on the island began as another rapid response. Six aircraft left RAF Lossiemouth at rst light after the dramatic latenight parliamentary vote to extend counter-Daesh operations into Syria, the strategic message reinforced by the Defence Secretary’s announcement of the Typhoons’ departure. Coalition combat air patrols deterred Russian and Syrian interference in counterDaesh activity, assuring freedom to operate for the o ensive support and reconnaissance missions that gave Iraqi and Syrian Kurdish ground forces their decisive edge in recapturing territory.

and attack drones. Responding to reports of air activity near the Al-Tanf Coalition base in Syria during a routine patrol on 14 December 2021, a pair of Typhoons identi ed a small drone and shot it down with an ASRAAM (advanced shortrange air-to-air missile as soon as it became clear that it posed a threat to Coalition ground forces. Typhoon’s rst operational air-to-air missile

“Recent years on Operation Shader have seen renewed emphasis on the air-defence mission in response to the proliferation of small reconnaissance and attack drones”

Typhoon’s mature multi-role capability enabled it to augment Tornado GR4 and Reaper in their o ensive tasks, conducting hundreds of Paveway IV guided bomb attacks while retaining the ability to swing to a defensive counter-air posture whenever required. Following Tornado’s retirement, opportunities to employ the newly integrated Storm Shadow and Brimstone missiles were taken just before Daesh lost its nal territorial foothold and reverted to insurgency. Typhoon weapons expenditure declined steeply thereafter in what could be considered a mark of the Coalition air campaign’s success.

Recent years on Operation Shader have seen renewed emphasis on the air-defence mission in response to the proliferation of small reconnaissance

engagement was executed with skill and professionalism against a target that was made extremely challenging to detect and identify by its diminutive size and slow speed, highlighting the importance of the pending Typhoon AESA (active electronically scanned array) radar upgrade.

Escorting Rivet Joint over the Black Sea

Serving as rst responder once again in February 2022, Typhoons mounted long-duration sorties from RAF Coningsby (to patrol over Poland) and from RAF Akrotiri (to patrol over Romania) within 24 hours of Russian forces entering Ukraine. Conducted under NATO command, these Enhanced Vigilance Activity missions continued for months, signalling

The presence of Typhoons in any region can have a noticeable deterrent e ect

(PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

Typhoon has come to symbolise UK power projection, in uence and strategic agility (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

the UK’s steadfast commitment to the Alliance and serving as a clear demonstration of NATO’s resolve in the face of Russian aggression.

Operation Aluminium notably added another facet to the RAF’s strategic jewel in the Eastern Mediterranean, using RAF Akrotiri for the rst time to project conventional power north into Europe. Escort of UK-based Rivet Joint aircraft conducting reconnaissance missions over the Black Sea was added to the RAF Akrotiri detachment’s rapidly lengthening task list. Deployment of additional Typhoons enabled Operation Shader missions to continue in parallel. 12 Squadron’s participation in the air defence of Qatar during the 2022 Fifa World Cup closed out a year of incredible success and diversity of output.

Increased NATO Air Policing detachment

Typhoon’s annual NATO Air Policing detachment has also increased in size and scope since the invasion of Ukraine. Expanded from four to six aircraft to provide opportunities for interoperability development with Alliance partners, the detachment conducts frequent small-scale redeployments to exercise the Agile Combat Employment (ACE) concept.

Technical interoperability between Alliance partners is another important contributor to agility and responsiveness, and good progress has been

made with support from the European Air Group. Typhoon has also resumed participation in the Tactical Leadership Programme’s ying course after a long absence, with a view to improving awareness and understanding of NATO procedures and partner capabilities among both pilots and technicians.

Neutralising the Iranian attack on Israel

Agility and responsiveness were both on show once again during April 2024 when the six Typhoons assigned to NATO Air Policing were relocated from Romania to Cyprus after Iran declared intent to mount its rst-ever direct attack on Israel. Typhoons were on patrol in Iraq and Syria and shot down several Iranian one-way drones, contributing to neutralisation of the attack and maintenance of regional stability. The six aircraft were redeployed back to Romania before any gaps in NATO task coverage could materialise.

Enabled by dependable Voyager air-refuelling support, Typhoon has come to symbolise UK power projection, in uence and strategic agility, while sustaining an assured defensive posture at home. With platform availability high and improving, pilot numbers growing and mature multi-role capabilities due to be improved by the Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar upgrade, Typhoon’s standing as the RAF’s longrange rst responder looks set to endure.

Quality is an obligation

Ralf Breiling Chief Executive O cer, EUROJET Turbo GmbH

Having joined EUROJET in July 2024, what are your key priorities for the next phase of product evolution and customer support?

My rst six months as CEO of EUROJET coincided with a marked resurgence of interest in the Euro ghter Typhoon fast-jet aircraft, which naturally resulted in the need for more of our EJ200 engines. Therefore, one of my priorities is to maintain our exacting standards in terms of performance, reliability and e ciency. EUROJET has always been dedicated to playing our part in ensuring the highest levels of the Euro ghter Typhoon’s weapon system and its fullest operational capability. We are fortunate that we have consistently enjoyed excellent feedback from our customers, with whom we are in constant contact. We work closely with the NATO Euro ghter & Tornado Management Agency (NETMA) and Euro ghter to keep a constant watch on the in-service behaviour of the engine, so that we can maintain the highest levels of performance and identify opportunities for improvement.

How does the EJ200 compare to other fast-jet power plants on the market? What are its key advantages?

One of the secrets of the EJ200’s excellent performance retention is its extremely high thrust-to-weight ratio, which makes it a signi cant benchmark compared to other fast-jet engines, especially when operating in harsh conditions. Another key aspect of the EJ200 is the digital control system, which takes away much of the burden of operating the engine from the pilot and ensures that the engine is not driven beyond any of its operating limits. This allows the pilot to fully concentrate on the mission at hand.

“We have consistently enjoyed excellent feedback from our customers”

Beyond these crucial factors, we also have state-of-the-art diagnostic and testing tools that enable us to reduce the maintenance burden. There is an Executive Lifing system that continuously monitors the usage of life-limited components. This allows the operators to make best use of the engine before components may need to be exchanged. We combine this with an exceptionally low-maintenance concept that relies on the actual condition of the engine and its components, rather than imposed regular interval inspections.

With a resurgence in interest in the Euro ghter aircraft, what plans are EUROJET making to ensure these new aircraft have the best possible power plant?

The remarkable spike in interest in the Euro ghter – with new orders from Italy and Spain and a potential order from Germany in the pipeline – is an opportunity for EUROJET to increase its production capacity and, in doing so, grow the supply chain and strengthen its resilience.

As you would expect, we are establishing plans to meet this new demand, alongside our industrial partner companies, to ensure that we can ful l every order. So, there is a full commitment to simultaneously supporting the needs of the core customer nations, as well as our export customers.

Can you o er an update on the long-term evolution of the EJ200 and how it will bene t operators, including the RAF?

As I mentioned, EUROJET is in constant contact with our customers and the feedback we are getting about the EJ200’s excellent performance has con rmed the high levels of current customer satisfaction, especially with the RAF. With the EJ200 still consistently delivering exceptional performance and exceeding customer requirements, the core nations have decided not to pursue the Long-Term Evolution package we proposed, expressing their con dence in the engine’s current capabilities.

The RAF ies in complex operating environments, which allows us to continuously assess and meet emerging needs. We are naturally fully committed to and aligned with their evolving requirements.

Ready to respond

Richard Hamilton, Managing Director Europe & International, BAE Systems, discusses the critical role that industry must play to respond to the ever-changing global threat and the importance of sovereign defence capability

On the day that Russia mounted its illegal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the need to secure Europe’s eastern border became a priority for the NATO Alliance.

Investment in combat air programmes supports growth and technology development

(IMAGE: BAE SYSTEMS)

The response of the Royal Air Force was immediate, and UK industry stepped up to support. Within hours of the invasion, teams from BAE Systems were working alongside their RAF counterparts to establish the upgrades needed and what could be accelerated to ensure its Typhoon eet was ready to respond.

Over the following days and weeks, multiple software and hardware upgrades were delivered to the front-line eet, and new weapons were tested in our integration rigs.

Since then, the need for speed to meet operational requirements at pace has not slowed within our teams supporting the UK’s critical role at the heart of NATO, whether through front-line support, engineering critical capabilities or delivering training to ensure readiness. We must not underestimate the powerful message that sovereign industry working closely with the military sends to potential adversaries about the strength of our capabilities.

Defence Acceleration Production Plan

The creation of the NATO-led Defence Acceleration Production Plan in 2023 underlined the vital role that industry plays in accelerating the production of equipment, boosting capacity and securing critical

supply chains, and this was further strengthened by NATO’s Industrial Capacity Expansion Pledge in 2024. All of this ensures we provide what our armed forces need to deter, defend and defeat and our people feel a huge sense of pride in the role they play.

BAE Systems today is the only sovereign advanced combat air provider in the UK and, as such, can act on behalf of the UK in times of need and crisis. It has been the custodian of generations of some of the most signi cant innovations in aviation history – indeed, history full stop. It was only the forward thinking of the likes of R J Mitchell and Sir Sydney Camm that gave us the Supermarine Spit re and the Hawker Hurricane. Today, a new generation of British engineers and designers are developing the aircraft that will make up the future of military aviation for both the UK and global partners.

Providing current and future options

Through investments in research and development (R&D), we are giving our international customers the options they need both now and in the future. We are evolving capability on Typhoon, investing in unmanned systems that will be integral in the future battlespace and developing the RAF’s nextgeneration combat aircraft, Tempest. The ability of industry to deliver capability across generations maximises the deterrent to our enemies.

But our R&D goes beyond platforms investing in areas, including data science and digital analysis exploitation, that will be vital to success in an increasingly contested future battlespace. This work brings capability and strengthens alliances. Collaborations, such as Euro ghter, partner the UK with NATO allies Germany, Italy and Spain, and beyond to the Middle East, and with Italy and Japan on the Global Combat Air Programme. At a political, military

and industrial level, we share a common aim and approach. The need to protect our national ecosystem, which provides this capability, has arguably never been so crucial and it delivers growth to our economy.

Supporting growth and technology

In the UK, investment in combat air has supported growth and advancement of UK technology and development of high-value skills and meaningful careers. Today our industry supports more than 48,000 high-skilled jobs across every part of the UK, in specialist areas such as design, ight testing, radar, engine and advanced weapons capability development, and complex systems integration.

The sector has an annual turnover of more than £6bn. It is responsible for more than 85% of defence exports; supporting the UK’s international relationships; ful lling agreements that underpin international security and defence with allies across NATO and beyond.

In 2018, the UK Government launched its Combat Air Strategy, outlining a vision, framework and timeline to assess options for the UK’s future combat air requirements, giving industry con dence to invest in research and development and transform business practices.

The years that have followed have seen us take huge strides, but we cannot a ord to let the pace of progress falter. Investment in sovereign combat air programmes, such as Typhoon and Tempest, stimulates the ecosystems that underpin our industrial base, ensuring the UK can continue to tailor its defence capabilities to meet evolving threats and operational requirements e ectively.

At BAE Systems, we are committed to responding to the needs of today and investing to meet the threats of tomorrow.

Collaborations on combat aircraft programmes such as Euro ghter Typhoon forge robust relationships with allies and partners (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

Celebrating 100 years of supplying advanced military engines

Jill Albertelli President, Pratt & Whitney Military Engines

This is a big year for Pratt & Whitney – what’s the signi cance of 2025?

This year marks Pratt & Whitney’s centennial anniversary. Our business began in 1925 with the invention of the R-1340 Wasp engine for the U.S. Navy. Today, Pratt & Whitney has more than 7,500 military engines elded, ranging in size from 150 to 50,000 pounds of thrust, with over 30 global operators.

Can you highlight some of the updates you are making to keep your engines war-ready?

Pratt & Whitney is committed to investing in the sustainment and modernisation of our engines. As more capabilities are tted to airframes, the engine plays a crucial role supporting those added requirements.

There are several examples of how we’re adding increased capability to our engines. The F100, which has been ying for over 50 years, is the only fourthgeneration engine o ering operationally proven fth-generation technologies. Our F119 engine underwent a software update, enabling increased thrust for the customer. And our F135 Engine Core Upgrade delivers the durability and performance needed to enable Block 4 capabilities and beyond.

What’s next for the F-35?

The F135 Engine Core Upgrade will help ensure the United States and our allies can maintain air superiority for decades to come. It is a drop-in upgrade that is retro ttable into all F-35 variants and is available to all F-35 operators. It o ers operators additional power and thermal management capacity needed to enable next-gen weapons systems and sensors.

With respect to the Engine Core Upgrade progress, our team completed a preliminary design review last July. We received a contract valued at up to $1.3bn in October to continue work, we have around 800 engineers and programme managers working fulltime, and we are progressing in line with the government schedule.

Looking to the future, where is propulsion technology headed?

We are working on incredible technologies. We are the propulsion provider for the sixth-generation B-21 bomber, which is undergoing ight testing and scaling into production. We are well positioned with propulsion

solutions for CCAs – whether that’s leveraging commercial-o -the-shelf solutions or scaling existing engines. And we are making phenomenal progress with our Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) o ering for the U.S. Air Force. With the successful completion of detailed design review in February, the next contract phase is under way to procure and assemble our XA103 prototype ground demonstrator, with testing expected in the late 2020s.

We’ve also seen in the past ve years how modern warfare has changed. How is Pratt & Whitney adapting to that evolving battle eld?

Contested logistics are now a reality, and we’re facing unprecedented threats to our defence ecosystems. And, as we develop engines, we need to factor these challenges in supplying and sustaining military operations when an adversary actively targets or disrupts those e orts.

Pratt & Whitney is facilitating resilience through the implementation of digital processes and additive manufacturing. Our digital transformation is resulting in improved e ciency and e ectiveness. We have established a collaborative digital environment, allowing for reviews that are more comprehensive as they provide direct access to digital artefacts and engineering tools that model our progress. And additive manufacturing is transforming the way we design and manufacture products, allowing for fewer parts, scalability, a ordability and manufacturing exibility.

Creating an F-35 culture

Lieutenant General André Steur, Commander of the Royal Netherlands Air and Space Force (RNLASF), highlights how the worldwide community of F-35 operators is creating an innovative culture of allies ready to ‘Fight Tonight’, ‘Fight Tomorrow’ and ‘Fight Together’

In a world where safety and e ectiveness go hand in hand, the F-35 is not just an aircraft, but a symbol of innovation and cooperation.

The culture that emerges around this is built on a number of key pillars: well-trained professionals working in a networked high-tech environment; a warrior mindset of not holding back and stepping

forward when needed; direct communication; team spirit; trust in each other on the ground and in the air; and, from the start of planning, rank is irrelevant.

But what exactly is this culture? Culture is not a xed entity, but a dynamic living phenomenon shaped by the interaction between people, traditions and circumstances.

An F-35A of the RNLASF ies during Exercise Ramstein Flag 25 (PHOTO:

Within the F-35 community – but, in a sense, this applies to the entire air force family – we build on a rich history of traditions, values and behaviours. In other words, we stand on the shoulders of our predecessors. That collective background is the foundation on which we build today. But we are aware that culture lives, moves and develops. In a rapidly changing world, organisational culture sometimes requires adaptation. We take the strong elements of the past, such as discipline, camaraderie and a sense of duty, and evolve them to meet the demands and circumstances of today. External in uences – such

as technological developments, societal changes or international missions – force us to re ect on: what do we keep, and what do we let go? The formation of culture within an organisation is, therefore, a conscious and important process.

Collaboration and innovation

In the F-35 community, this means that, on the one hand, we cherish traditions, and at the same time we create space for growth, collaboration and innovation. It’s not just about rules and ranks; it’s about shared values, role models, challenging each other and constantly improving.

“The lessons learnt from current and recent con icts show that gaining air superiority is essential for the freedom of action of our brothers and sisters at sea, on land and in the air”

Our focus is on ‘Fight Tonight’ and ‘Fight Tomorrow’. We are always ready to take immediate action when needed and to sustain it for as long as necessary. We believe in credible deterrence: credibility, capability and communication. Our capabilities, and the willingness to use them, provide a deterrent to our adversaries. In order to make the right decisions, we are constantly working to increase our situational understanding; we must always be aware of the latest developments and be able to react quickly to changes in the environment. We do not wait, but act – today, if we have to, with everything we have. We’re not doing this alone. ‘Fight Together’ is our motto. We collaborate nationally and internationally in multi-domain operations, combining our

capabilities to achieve maximum impact. We are increasing our e ectiveness by reaching out from the multiple domains of air, space, land, sea and cyber to achieve e ects in the cognitive, virtual and physical dimensions. The lessons learnt from current and recent con icts show that gaining air superiority is essential for the freedom of action of our brothers and sisters at sea, on land and in the air – even if it is sometimes temporary and local.

A transatlantic culture

But we are aware that Europe cannot face these challenges alone. We need the support and cooperation of our transatlantic allies to achieve our goals. At the same time, we are striving for a

The RNLASF joined the community of F-35 operators in 2019 with its rst F-35A (PHOTO: NETHERLANDS MOD)

more autonomous European Defence, in which we develop and deploy our own capabilities to protect our security and interests.

This is not a contradiction, but a necessary step towards a stronger and more resilient Europe. We need to join hands as European countries, but we also need to nurture the ties with our transatlantic allies to face the challenges of the 21st century together.

Working together

The F-35 culture promotes working as a team to achieve goals (PHOTO: NETHERLANDS MOD)

The F-35 culture is about creating a community in which everyone contributes his or her part to the greater whole. We strive for a culture where tradition and innovation meet, where we take our strength from the past and, at the same time, create space for new ideas and developments.

In this culture, there is room for everyone –not just for the veterans who share their knowledge and experience, but also for reservists and civilians, as well as those young, talented individuals who bring innovation and boundless energy. We’re a team, a family, a community working together to achieve our goals. One team, one task – small in number, large in deeds.

The F-35 culture is unique and dynamic. It is closely related to the Whole Air Force culture and builds on a rich history of traditions and values. We are proud of our culture and strive to preserve and develop it. By focusing on ‘Fight Tonight’, ‘Fight Tomorrow’ and ‘Fight Together’, we are always ready to respond to the challenges of the 21st century and to protect our security and interests.

F-35 – the world’s most advanced ghter aircraft

Paul Livingston Chief Executive UK & NATO, Lockheed Martin

How does the Lockheed Martin F-35B enable the RAF’s current air capabilities and how will it evolve for future operations?

As the world’s most advanced ghter aircraft, the F-35B is a critical component of the Royal Air Force’s air capabilities and serves as the backbone of its Carrier Strike capability. Flown from the UK’s Queen Elizabeth -class carriers and RAF Marham in Norfolk, the F-35B’s advanced avionics and sensor systems enable the RAF to gather and share critical information in real time, enhancing situational awareness.

The F-35 is the glue that connects the nation’s defence assets and is the only platform capable of collecting and disseminating data from satellites to the air, naval and ground forces of any ally, while at the same time protecting them from the air. In fact, last December, in partnership with the UK RAF Rapid Capabilities O ce, our Skunk Works® team

demonstrated the F-35’s ability to share live classi ed data via an open systems gateway with an RAF command and control system. As we look ahead, the F-35 was designed with upgrades in mind, allowing for additional capabilities to be added to meet evolving threats and ensure UK deterrence and security for decades to come.

What is the status of the RAF F-35B delivery programme and how else will Lockheed Martin contribute to the UK’s longterm prosperity and security?

We have delivered 38 of the rst tranche of the UK’s 48 jets, with the remainder expected by early 2026. Currently, the UK’s F-35s are contributing to the Carrier Strike Group 2025 (CSG25) global deployment, further demonstrating its unrivalled capabilities in complex operations.

“The F-35’s growing presence is a powerful example of alliance-based deterrence”

The F-35 is one part of Lockheed Martin’s impact in the UK. In addition to the more than 2,000 Lockheed Martin employees in the UK today, we also support over 25,000 UK jobs across aerospace and defence in every home nation of the UK and contribute an average of £1.9 billion to the UK economy every year.

Why is the Lockheed Martin F-35 important for enabling international partners to interoperate across the globe?

Today, in the UK and across Europe, the F-35’s growing presence is a powerful example of alliance-based deterrence. By gathering, analysing and seamlessly sharing critical data, the F-35 gives commanders unprecedented situational awareness and the con dence to act quickly. Multinational F-35 training and exercises, such as CSG25, have demonstrated the transformative e ect of a multi-country fth-generation aircraft eet. One F-35 is a force multiplier. More than a thousand F-35s is a global force of advanced, interoperable ghters that ensures allied nations will continue to own the skies.

How is Lockheed Martin embracing new technologies to ensure its defence systems can cope with evolving threats?

Across Lockheed Martin, we are embracing and leveraging new technologies to deliver the speed, agility and insights our customers need to stay ahead of rapidly evolving threats. One example is how we are using arti cial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to process, fuse and analyse tremendous amounts of data to give our customers actionable intelligence and a strategic advantage. In fact, our Skunk Works® team is bringing more than 80 years of innovative solutions to the UK Armed Forces through the TIQUILA intelligence, surveillance, tracking and reconnaissance (ISTAR) programme which is driven by AI technology.

Integration – the right stu ?

Air Marshal (Retd) Greg Bagwell CB CBE FRAeS, President of the Air & Space Power Association, considers the advantages of integrating existing capabilities with tactics and innovation

As many countries begin to reverse decades of lower investment in Defence, there is an understandable tension in what to spend that additional investment on. For many, it will be as simple as thickening what we already have, by building up stockpiles and increasing our resilience to sustained or surprise attack. Some will have gaps that need to be lled, now that the risk of their absence can no longer be tolerated. And most will be looking to the horizon and beyond to ensure that we have considered and embraced those technologies that confer a future advantage, and keep us ahead of our potential adversaries. And whatever strategy we pursue, we will all be looking at the lessons observed from recent con icts, and seeking to apply those that are relevant to the next one. They say that quantity has a quality all of its own, and the attritional and swarming attacks that we observe in both Ukraine and the Middle East could suggest that we need more mass to counter or deter such a war; there is some truth in this thesis, as weapon stockpiles and rearmament

manufacturing is placed under signi cant strain. Using a ludicrously simple mathematical formula, such a conclusion could result in an equation that looks something like this:

Stu + more stu + responsive supply chain = sustainable mass

In terms of a strategy, this means ghting re with re and seeking to make the cost to a foe like Russia too great to bear. That might deter an attack, yet we have seen Russia’s appetite for loss and hardship far outstrip that which western European countries might tolerate. So, pursuing such a strategy implies that we are prepared both physically and mentally to go toe to toe with a less morally-observant adversary. Thus, might we be in danger of extracting the wrong lessons from

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine

– a con ict that has turned into the horri c, static stalemate of trench warfare and war on a population?

A strategy that purely pursues mass as a means to win is not only an expensive one, but one that relies on sheer will and sustained public support to succeed. Thankfully, there is another way, and that is maximising the use of the capability you already have by multiplying its e ect:

Stu x tactics x integration = overwhelming e ect

Here, it’s the multiplying e ect of our ingenuity through optimised tactics and integration that can make up for a lack of pure mass, but it also seeks to avoid the type of attritional war that Russia believes exploits the weaknesses of modern democracies. However, in a time of

Exercising together to improve operational integration and interoperability is vital (PHOTO: MOD/CROWN COPYRIGHT)

uncertainty and doubt, we should also see better integration as a unifying power, as well as just a more e cient and e ective way of ghting.

I know that these equations oversimplify and inaccurately represent the true complexity of force design; and, anyway, the mathematical truth is that, while the second equation is compelling, your amount of ‘stu ’ still has a signi cant impact on the result. But the point my low-grade maths is trying to make is that it is the multiplying e ects of tactics and integration that is so important here, and buying more stu and strengthening supply chains takes time and money that we currently have so little of.

Air and space power inherently act as integrators, both in their own domains and even more vitally with the other domains. It is the force multiplier that is worth so much

“Air and space power inherently act as integrators, both in their own domains and even more vitally with the other domains”

more than the sum of its parts. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that recently the most noise from a belligerent Russia has come when the threat of more air or space power to Ukraine is on the table. Whether it be the provision of combat aircraft, satellite feeds or longer-range strike weapons, Russia is frightened by the prospect of western air and space power around or over its borders. It is frightened not just by the technological edge we still (just) enjoy, but by the way we ght, and the way we ght together. Integrated NATO airpower brings a dynamic to the

ght that Russia now knows it will nd hard to handle. That Ukraine has achieved so much with so little, should be all the warning signs that Russia needs.

So, as we seek to strengthen our defences by buying more stu , we should not forget that the continued development of our tactics and the design, exercising and maintenance of our integration is every bit as important as we seek to deter and, if necessary, defeat any future threats. Yes, we need more ‘stu ’, but integration is the ‘right stu ’ that makes it so much more e ective.

OPERATION UNDERHILL

Humanitarian airdrops in Gaza

On 24 March 2024, an RAF Air Mobility Force A400M Atlas cargo transporter dropped food and provisions to the people in Gaza. The RAF’s Air Mobility Force Commander, Air Commodore Dan James, reveals the complexities of this multifaceted aid operation and how it has evolved since that rst drop

The Air Mobility Force was tasked to deliver humanitarian aid into war-torn Gaza, resulting in the A400M’s rst-ever operational ‘air drop’ in RAF service on 24 March 2024. Highlighting the contemporary importance of Air Mobility capability, over six weeks RAF crews successfully delivered over 110 tonnes of life-saving aid with pinpoint accuracy onto extremely small, unmarked and uncontrolled Drop Zones. This support to Operation Underhill is a salient reminder of

Air Power’s enduring ability to deliver e ect at range. The forebears of 30 Squadron (now one of the two dedicated A400M squadrons) rst used air drop to resupply the besieged fort of Al Amara in Iraq with aid in April 1916, two years before the RAF was formed. However, since the rst air drop in Iraq over a century ago, modern Air Mobility operations have evolved considerably. During Operation Underhill, the key considerations were broadly typical of modern air operations: decon iction and planning

in a coalition; a change from scenarios normally used for training (in this case, the use of unusual Drop Zones); command and control; and the ability to rapidly replace critical stocks from industry.

Coordinating with allies

During Operation Underhill, the Air Mobility Force was tasked to prepare, plan, coordinate and conduct air drops alongside regional and global allies. Operating in a rapidly assembled bespoke coalition and underwriting safe decon iction from all other platforms can be challenging. At the height of the operation, crews from Belgium, Egypt, France, Germany, Jordan, Philippines, UAE, UK and USA were all involved.

On the two air drops over Eid on 9 and 10 April, a total of 17 aircraft ew in the formation. Alongside these Air Mobility aircraft, low-level rotary-wing tra c and small Unmanned Air System surveillance assets were operating in the same segregated area.

This airspace congestion required thorough planning to ensure each element of the air package was coordinated and decon icted to their designated – and di erent – Drop Zones. Speci c routing requirements, with strict time spacing, di erent formation operating procedures and di erent native languages, made this coordination a challenge for all the crews. From an RAF perspective, this re-enforced the value of honing skills on regular and frequent international exercises to learn to collaborate exibly with di erent partners.

Mitigating injury risks

Unlike the scenarios that the A400M crews normally used for training, the available Drop Zones were small, with restrictions due to the urban surroundings of damaged buildings and the dynamic nature of the con ict. In many cases, the beaches were the best option. However, given no ground forces were able to clear Drop Zones before use, the areas

Safety was paramount during each air drop

(PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

The highly versatile Airbus A400M (seen here on the tarmac in Amman, Jordan) is one of the RAF Air Mobility Force’s key assets (PHOTO: MOD/ CROWN COPYRIGHT)

were often busy with local people desperate for aid, which raised the risk of the humanitarian stores causing severe injury. That said, these risks were mitigated using surveillance feeds, Air command and control, and mission command.

Real-time communication

Before each drop, live overhead surveillance footage was monitored from the 603rd Combined Air Operations Centre in Al Udeid by the Deputy Air Component Commander to assess the risk of injury to civilians. Live satellite communication to the A400Ms permitted real-time communication, enabling a ‘Go/No Go’ decision by the Deputy Air Component Commander at 10 minutes before each drop.

If the decision was ‘Go’, the crew were cleared to continue preparing to drop, unless they felt the Drop Zone was compromised, or the safety of the aircraft or crew was at risk. However, in accordance with the principles of mission command, each A400M captain had the nal decision, with the safety of the vulnerable population to consider carefully in a short space of time, while operating their aircraft at low level.