Social Production and its Discontents.

Glenn Mckerracher rooms+cities

Factory2

Figure 1 : Cover - Author’s Own, 2023.

“Factory2 : Social Production and it’s Discontents”

by Glenn Mckerracher

Studio: rooms+cities

Tutor: Dr Lorens Holm

A Master’s Thesis submitted to: School of Architecture Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design University of Dundee April 2024

In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Architecture (MArch)

word count: 5,650

01 : Lorens Holm, studio brief, ‘rooms+cities – a machine for organising people and knowledge in the public realm’ (12 09 23).

rooms+cities

02 : Lorens Holm, studio brief, ‘rooms+cities – a machine for organising people and knowledge in the public realm’ (12 09 23).

“Rooms + Cities - a machine for organising people and knowledge in the public realm”01

rooms+cities, a design research studio that resides within the University of Dundee department of Architecture. This year returning to Cumbernauld New Town as a site for testing new ideas around the role of architecture in society. The group research undertaken hoped to uncover questions and open discussions, which comprehensively contextualise the town centres current predicament.

This group research project examined Cumbernauld in three separate contexts. Cumbernauld as a place, the history of its conception and eventual demise to what is now a condemned building. Cumbernauld as a series of rooms, which viewed the town centre, as a matrix of components that when assembled, form a town centre. Finally, Cumbernauld as a city, placing the town back into its context as part of a peripheral landscape.

The individual design research project “Factory 2 : Social Production and its Discontents,” reacts to two key aspects of the initial group work to take new lines of enquiry from the conclusions formed:

01: The rooms study defined the town centre as a series of interchangeable components. The components of the centre, along with other social functions within the boundaries of an 800m central square are re-assembled into a singular built level of the inhabited boundary wall. Cumbernauld arranges the social functions of a town centre into a centralised stacked building whereas the Social Factory arranges these functions into a peripheral block.

02: The cities research resulted in a series of drawings that defined centric and non-centric landscapes in which the city centre was either present or absent. The Social Factory looks to inhabit the void left by these non-centric drawings, beginning with Cumbernauld and expanding to the other towns and cities of the central belt used within this drawing exercise.

“In rooms+cities, we identify problems in our thinking about settlements, and use architectural design as a research means and method to explore these problems.”02

II Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 2 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld’s now uninhabited penthouses, photographed on a group site visit to the town centre.

Figure 2 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld’s now uninhabited penthouses, photographed on a group site visit to the town centre.

IV

Glenn Mckerracher

3 : rooms+cities, 2024. Components of Cumbernauld in section identified in the rooms study and acted upon within factory2

0 5 25m

V Factory2

Figure

4 :

Figure

rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld centric plan.

Figure 5 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld non-centric plan

Figure 5 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld non-centric plan

Figure 6 : Tano D’Amico, 1977. The autonomous student movement Movimento del ‘77 pictured in Roma. The photographs of D’Amico’s depict social and political unrest in Rome, Florence, Milan, and other parts of Southern Italy between 1969 and 2019. His works contextualise the feeling of workerist organizations that Mario Tronti was engaged with.

Figure 6 : Tano D’Amico, 1977. The autonomous student movement Movimento del ‘77 pictured in Roma. The photographs of D’Amico’s depict social and political unrest in Rome, Florence, Milan, and other parts of Southern Italy between 1969 and 2019. His works contextualise the feeling of workerist organizations that Mario Tronti was engaged with.

Abstract

“The Social Factory”, a theory conceived by Mario Tronti, understands that the reach of capitalist production has now extended beyond the walls of the factory to the entirety of the urban realm. This has, in turn, brought new priorities for space, and resulted in the formation of a generic cityscape. Created through a loss of identity structured on historical principles of place to facilitate a more efficient means of production. Architecture is now reduced to a set of standardised components repeatable ad infinitum. This thesis studies “The Social Factory” as an urban landscape concerned with the production of a generic mental state for its inhabitants with profit-driven intentions. In turn, shining a light on the factory-like nature of the modern capitalist metropolis

Georg Simmel’s canonical essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life” seeks to unpack the reactions of the individual in the metropolis as they negotiate aspects of contemporary life, drawing links between the individual and the realm in which they inhabit. In his understanding, the way in which this is done is through the expression of a “blasé attitude,” a generic psychological reaction exhibited to shield the metropolitan from the “shock suffered in the city.”03 By revisiting this generic mental state, a twenty-first-century reboot will be exposed, the generic self.

This project depicts an interpretation of the “Social Factory”, the factory itself concerned with the production of the generic self. The productive output of the factory aligns with the three influences of the generic self; the mental, the built and the technological. Generic thought produced via an Edu Factory, generic buildings produced from a Typology Factory and surveillance capitalism generated within a Data Factory. These three lines of production combine to form a Social Factory. The condemned town centre of Cumbernauld will form the backdrop to provoke the questions set out within the text, an initial laboratory with intentions of further expansion to every large town and city within the central belt. An inhabited wall acts as a boundary to retain the functions of the “Social Factory” within the generic city centre. This serves as a tangible manifestation of societal industrialization, encapsulating the intertwined influences of social dynamics, the built environment, and technological advancements on contemporary urban experiences.

03 : Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Mass. u.a: MIT Press, 1977), 86.

Factory2 IX

“The social relation of capitalist production sees society as a means and production as an end: capitalism is production for production.”

Mario Tronti, Factory and Society.

the city as a social factory a city of production and consumption method statement the generic self clocking out 01 09 33 39 49 abstract IX content introduction 04 appendix image references bibliography 51 53 55

04 : Mario Tronti, “Factory and Society,” trans. Guio Jacinto, Operaismo in English, June 13, 2013, https://operaismoinenglish. wordpress.com/2013/06/13/factoryand-society/.

Method Statement

This design research project frames a “Social Factory” within the centre of Cumbernauld, removing centralised identity and facilitating production of the generic self within its boundary wall as an industrialisation of the central plane. This inhabited wall frames the lens which sharpens the distinction between factory and society, keeping factory within the centre and the remainder of society outwith, thereby creating two conditions. An internal condition of intense production and an external condition of consumption. The productive centre will conceptualise the thought of Tronti, as a literal realisation that “the whole of society lives as a function of the factory.”04

Sigmund Freud

the mental Civilisation and its Discontents

Edu Factory

The Social Factory

Typology Factory

the generic self product the technological

Rem Koolhaas the built

Data Factory

Surveillance Capitalism

Shoshana Zuboff

Figure 7 : Author’s Own, 2024. Diagram illustrating the influences of the generic self in relation to factory process which drive it.

01 Glenn Mckerracher

S,M,L,XL

The Generic Self

A reboot of Simmel’s blase metropolitan attitude, the generic self is the modern psychological reaction exhibited by those dwelling within large capitalist towns and cities. It suggests that inhabitants exhibit a generic mental state, one which is repetitive and indifferent to value, as a result of becoming a product of the city. The generic self has three key influences that define it; the built, the mental and the technological.

The Social Factory

An urban condition in which production extends beyond the perimeter of the factory to all of social life. The Social Factory designed within this project focusses its attention toward the production of a psychological reaction; the generic self. The combination of three factories, Edu Factory, Typology Factory and Data Factory, form the Social Factory envisioned in this project.

Edu Factory

The Edu Factory is concerned with directly influencing the mental state of its workers. It teaches lessons in how they should interact with other individuals within the Social Factory, and how to act in a generic manner.

Typology Factory

The Typology Factory produces a generic form of buildings. Typically modular these a-contextual cells are used by the modern architect to design the city.

Data Factory

The Data Factory generates products that predict future human behaviours which are in turn traded to large co-orporations to allow them to target workers with personalised bombardment of advertisements and information. This aspect influencing workers through technology. The data factory collects information of the workers daily life. Online, at work and at home.

02 Factory2

Figure 8 : Ricahrd Lagendorf, 1970. Cumbernauld Town Centre prior to peripheral development.

Figure 8 : Ricahrd Lagendorf, 1970. Cumbernauld Town Centre prior to peripheral development.

Introduction

As Fordism rose to dominate commodity manufacture, production turned from the creation of objects for capital gain to the production of humanity for capital gain. In the early 1960s, within his paper “Factory and Society”, Italian Workerist Mario Tronti, theorised the concept of the Social Factory. He understood an urban condition where production, initially considered as a process taking place solely within the factory, now extended to the entirety of social life. “At the highest level of capitalist development, the social relation is transformed into a moment of the relation of production, the whole of society is turned into an articulation of production, that is, the whole of society lives as a function of the factory and the factory extends its exclusive domination to the whole of society.”05 The prominent raw material used in production once natural resources, such as timber and brick, now uses the nature of humanity itself. “Factory and Society” provides the narrative to depict the city as a landscape in which every aspect of humanity is an economic tool. This thesis is concerned with the production of a generic mental state and with that degradation of identity as a critique of the global capitalist city, shining a light on the factory-like nature it possesses.

A Generic Plane

Identity is typically a defining component of both the individual and the city, established over a period of time due to the interactions with living, built or other components; the individual and the city can be perceived as ever-evolving organisms. Modern planning grapples with balancing the principles of identity, often prioritising profit over people and finding a common theme in the production of generic.06 The result of this is best described by Koolhaas in his essay “The Generic City” as “what is left when identity is stripped.”07 The visual implications of this are clear in the homogenisation of built aesthetics within architecture and planning on a global scale. With intentions to eliminate the identity defined by the past, in an attempt to create an alladaptable city with a never-ending set of interchangeable modules and functions. Typically history can be found in the central areas of towns and cities, hence it could be understood that “identity centralizes.”08 To eliminate the central area of the city creates a generic plane. This

05 : Mario Tronti, “Factory and Society,” trans. Guio Jacinto, Operaismo in English, June 13, 2013, https://operaismoinenglish. wordpress.com/2013/06/13/factoryand-society/.

06 : The etymology of generic can be traced to the Latin term genus, in turn meaning race or kind which could be understood as belonging to a large group of objects. Hence, referring to repetitive qualities typically possessed by modern building techniques. Koolhaas typically understands the generic city as being Singapore, however, this thesis understands the generic city applying to all scales of urban development.

07 : Rem Koolhaas, “The Generic City” in S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995) 1248.

08 : ibid 248.

04 Factory2

09 : Perhaps the first town or city to have its entire town centre demolished willingly by those who govern it rather than being demolished through war. The town centre attempted to gain listing in a last-ditch effort to preserve its history in 2022 and was refused. As a result, it will be demolished and replaced as part of a council-led regeneration project for the town.

10 : Reyner Banham, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1976), 16.

is the fate of the testing room of this project, Cumbernauld town centre.09 After tried and failed attempts to save the centrepiece of this twentieth-century New Town, “the most complete megastructure to be built”10 is now condemned. The decision to demolish a landmark so prominent in architectural and social discourse raises many questions around principles of identity.

Simmel in the Modern Metropolis

11 :Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Mass. u.a: MIT Press, 1977). 86.

12 : Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” in On Individuality and Social Forms: Selected Writings, ed. Donald Levine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 330.

13 : Ibid 324.

By examining the identity of built form in conjunction with the identity of a person, we can understand their interconnected relationship. In 1903, Georg Simmel’s canonical essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life” explores the response of the metropolitan individual as they negotiate contemporary life. In his understanding, the way this is done is through the expression of a “blasé attitude”, the psychological reaction used to overcome the “shock suffered in the city.”11 The essence of this consists in the blunting of discrimination, all objects appear in a “flat grey tone”12, no one object takes preference over the other. The metropolis in 2024, has followed a trajectory set out by Simmel and Tronti, as a result, the stimuli and interactions experienced in today’s metropolis have been further exaggerated in the time since the papers writing. “The eighteenth century may have called for liberation from all the ties which grew up historically in politics, in religion, in morality and in economics in order to permit the original virtue of man... The nineteenth century may have sought to promote, in addition to man’s freedom, his individuality.”13 Now, in the twentyfirst century, man looks to retract from society, as a result of becoming a product of the city. As an evolution of the city and the individuals within, a new mental state will be analysed within this thesis, a reboot

05 Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 9 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld Town Centre stripped of its identity, the megastructure.

of Simmels “blase attitude” and the product of the modern capitalist metropolis; the generic self.

The generic self will consider three key components that influence its composition: the mental, the built, and the technological.

- The mental, is the impact to ones mental state due to the influence of others; the influence of our upbringing and interactions on a human level.

- The built, in building techniques both of aesthetic and planning qualities.

- Finally, the technological impact which focuses within the realm of Surveillance Capitalism14 as a method of control over every aspect of human nature. Perhaps the most unknown element of influence and still ever-evolving, this contemporary sphere of influence was not featured in the writing of Simmel. The reason for such successful intervention into society as a capitalist tool for one reason? It is entirely unprecedented.

The factory-like conditions of the metropolis, act in a constant state of production. Using the individuals within it as the raw material by which profit is extracted. The condition created, not concerned with elements of place or identity, but a generic plane. The ideal environment for a high-profit landscape.

14 : Surveillance Capitalism is a contemporary economic system of the capitalist metropolis which collects and analyses personal data usually without the individuals knowledge. The data then utilised to predict future behavioural patterns

06 Factory2

Taxonomy of Peripheral Landscape Strips

07 Glenn Mckerracher Glasgow Edinburgh Paisley East Kilbride Livingston Dunfermline Hamilton Cumbernauld

Figure 10 : Author’s Own, 2023. Taxonomy of Peripheral Landscape Strips. Documenting 800m wide transects running from the centre to periphery of towns and cities in the central belt of Scotland with a population of over 50,000. Typically defining objects are found within the central areas and left behind on a journey to the periphery.

08 Factory2

15 : Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” in On Individuality and Social Forms: Selected Writings, ed. Donald Levine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 326.

16 : Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Mass. u.a: MIT Press, 1977). 86.

17 : Ibid.

18 : Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” in On Individuality and Social Forms: Selected Writings, ed. Donald Levine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 326.

19 : Ibid.

The Generic Self : A New Psychological Reaction

With the expansion of the city in the nineteenth century, rapid urbanization, and the emergence of novel subjective experiences, the phenomenon commonly referred to as the metropolis entered architectural discourse. In “Metropolis and Mental Life”, Georg Simmel suggests that the interactions between individuals that dwell within the metropolis are rational and calculated to psychologically cope with high stimulus that the metropolis generates. Thus the interactions experienced by a metropolitan are pushed to an area of mental process which is least vulnerable and most distant from the core of personality. This individual experiences situations akin to those present in the city itself; simultaneous overstimulation, facing a multitude of objects and people, balancing individuality within mass social relations and internalizing these social relations within themselves. “All emotional relationships between persons rest on their individuality, whereas intellectual relationships deal with persons as numbers, that is, as with elements which in themselves, are indifferent.”15 The architecture of the city is now a reflection of the people dwelling within the city, generic and rational. This rational nature is a product of capitalist, profit-driven cityscapes. Tafuri notes the nature described by Simmel and calls its exhibitor the “man without quality”16 who is “indifferent to value.”17 Economic conditions typically drive the form and evolution of a city, Simmel suggests, “the metropolis, identified as the seat of the ‘money economy”18 shapes not only tangible elements such as infrastructure, movement and form but also intangible components of the city such as the mental processes of its inhabitants. These cityscapes are now built from a set of interchangeable generic components. Their generic nature all but improves profit within the capitalist metropolis as “Money is concerned only with what is common to all.”19

The generic self sets out to modernise Simmels theory of the blasé attitude, through a close reading of the stimulus which is a cause for its conception.

- The impact of mental process is provided by an analysis of the writings of Sigmund Freud, taking on his ideas of the ego and the id as the complex which formulate the human psyche. An understanding of the psyche offers a comprehension of how and why people may be inclined to think and act in a certain way, and to understand how it may be possible to influence mental processes of others.

09 Glenn Mckerracher

- The influence of the built is examined through an analysis of modern architecture, understanding the city as a set of generic interchangeable cells where design becomes disassociated from function.

- Finally, a close reading of Shoshana Zuboff’s “Age of Surveillance Capitalism” modernises this attitude and provides the technological aspect of the generic self, a manifestation of how capitalism has conquered society by claiming the minute details of the individual and utilising them as a commodity. Permitted through a rapid progression of technology, sequentially developing a tool for gathering data on human behaviours and tendencies.

The amalgamation of these three spheres of influence encompass the generic self, a contemporary vision of the mental state induced by individuals inhabiting the modern metropolis as a result of capitalist factory society.

10 Factory2

The Mental Generic Lectures 01 Study 02 Examination 03 Graduation 04 Data Gathering 01 Data Analysis 02 Testing on an individual 03 Trading 04 The Technological Generic The Generic Self Raw Material Delivery 01 Component Assembly 03 Distribution + Delivery 05 Manufacturing Checks 04 The Built

Generic

Figure 11 : Author’s Own, 2024. Diagram illustrating the influences of the generic self in relation to factory process which drive it.

20 : Freud publishes an organ like ‘blob’ diagram in “The Ego and the Id” which sets to explain the way in which the ego represses the Id.

The Mental : Psychoanalysis of the City

The Freudian Psyche

Freud proposes three components that are used to formulate the human psyche, the totality of the human mind. The Freudian psyche encompasses both conscious and unconscious elements. The Id is the impulsive and entirely unconscious part of the psyche that responds immediately to basic human needs and urges. The personality of the human infant is primarily composed of the Id, only later do the other components develop. It is within the unconscious mind that the Id dwells. The unconscious can never be found specifically as the very act of doing so brings thought from unconscious to conscious, but it does show recognised symptoms.

The second component being the Ego, the part of the Id which has been modified directly by the influence of the external world on the person. The Ego is a conscious element of personality. The awareness of a person when they think to themselves and usually the way that they project toward others. In effect the ego is the image that I have of myself, which is not the same image held by others.20 The ego could be considered a ship, constantly surrounded by sea of unconscious.

The final component of the Freudian psyche and the last to develop, is the Superego which incorporates the values and morals of society by which the ego then operates, these behaviours are primarily absorbed from one’s parents.

11 Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 12 : Sigmund Freud, 1923. Structural Model of the Mind.

Reflections of the Self

Freud opposed the biblical commandment “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself”, the strongest defence against aggressiveness in human nature reinterpreting it as “love thy neighbour as thy neighbour loves thee.”21 In the generic city, you and your neighbour are urged to share the same ideals and shop for the same groceries. This generic capitalist city creates a production line for its raw material, the human psyche, to be manipulated. Now my neighbour who subconsciously views me as a mirror image of himself will represent themselves in the same way that I do. “My neighbour, if enjoined to love me as himself, will react exactly as I do and reject me for the same reasons.”22 Without knowing and perhaps without the will to do otherwise we find ourselves drawing comparisons between ourselves and those dwelling around us. Accepting the defined set of social norms. The metropolis plays a key role in the bringing together of neighbours. The reflection of ourselves in the generic city is perhaps not only in the mirror but also living across the street. One of Freud’s final notes, found shortly after his death translates to “Psyche is extended; knows nothing about it,”23 which is believed to describe how external space is understood as a projection of the internal psyche, the internal translated to a visual format. The French philosopher Jaques Derrida dwells on this note, “the spatiality of space, its exteriority would only be an outside projection of an internal and properly speaking psychical extension. In short, the outside would only be a projection!”24 Projecting the psyche as quantifiable elements which now ground it as physical manifestation which can be interpreted by others. The extension of the psyche in an unconscious manner. The generic qualities of human nature thereby can be represented within the urban realm.

The mental processes exhibited by a person share a clear and defined link to the environment in which they inhabit, so much so they could be considered one and the same. It is both the mental process of others and the environment of ones dwelling that define the way a person behaves and as a result, the reaction that they possess. The capitalist city could be considered to be a factory in which the psyche is produced, a constant conveyor belt taking human nature and influencing it in a particular manner. The inhabitants of the city influence the factory and the factory influences its inhabitants. Transforming the value of human nature from a subjective form to a purely objective existence.

21 : Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (New York: Norton, 1962), 59.

22 : Ibid. 60.

23 : Sigmund Freud, “Findings, Ideas, Problems (1941),” Standard Edition, 1971, 299–300.

24 : Jacques Derrida, On Touching, Jean-Luc Nancy (Stanford, Calif: Stanford Univ. Press, 2005), 43.

12 Factory2

Figure 13 : Author’s Own, 2024. Cumbernauld in Ville Contemporaine. Ville Contemporaine was the project to which Hochhausstadt was a response.

Figure 13 : Author’s Own, 2024. Cumbernauld in Ville Contemporaine. Ville Contemporaine was the project to which Hochhausstadt was a response.

14 : Ludwig Hilberseimer, 1924. Hochhausstadt perspective drawing

Figure 15 : Ludwig Hilberseimer, 1924. Hochhausstadt perspective drawing

Figure

Figure

The Built : Building Uniformity

Projecting the Psyche

An understanding of the Freudian psyche allows for the realisation that human nature is susceptible to influence from both individuals and objects within their immediate environment. The dynamic interaction between internal cognition and external expression unveils a correlation, vividly illustrated within the urban realm through the design of generic landscapes. This describes the conditions for the “blase attitude” that Simmel depicts. Further links between mental state and the external world can be drawn in Ludwig Hilberseimer’s project Hochhausstadt ,25 which is considered to embody Simmel’s metropolis. “It is true that Hilberseimer’s “city machine,” the image of Simmel’s metropolis, seized upon only certain aspects of the new function assigned to large cities by capitalist reorganization.”26 The rigid planning shown in this project allows for an infinite replication of cells27 embodying a Fordist style of production. This has created a generic city in its own right, not only in terms of built space but also the thought processes that exist within. “It is possible to interpret Hilberseimer’s drawings and projects as embodying what Simmel called the blase attitude.”28 Human nature is shaped by its immediate environment, a dynamic echoed within the city displaying the complex interactions between individual consciousness and societal influences. The modern architect is shown as the creator of single objects without the virtue of connecting the created objects in an urban manner. Through the lens of the generic, defined by uniformity and shared experience, the projection of internal thought onto external spaces perceives the unconscious impact of urban environments on human behaviour and thought processes.

Absolute Architecture

Though Hilberseimer’s project remained an unbuilt proposal, aspects of his design have been realised in the modern city, such as the creation of repetitive cells, a single type. Capitalist cities demand a generic form of building, arising from the need for impermanence in the city. An all-adaptable floor plan that prioritises flexibility over design. The aspiration for a generic plan allows for a variety of interchangeable functions to take place, therefore lacking the ability to commit to an identity. “The Generic City is fractal, an endless repetition of the same structural module”29 The standardised element, from the level

25 : Translated to High Rise City in English - the 1924 project was a critique of Corbusier’s Ville Contemporaine which he labelled as a model of flawed bourgeois thinking in turn not designing the contemporary city that the project set out to do. Hochhausstadt is a generic city with one typology, identical rooms with all buildings sharing the same language portrayed through a series of dystopian perspective drawings. His perspectives resemble something of a ghost town, where people cast no shadow and buildings are coloured in a uniform grey while the windows which puncture them are rendered with no frame in a dark black hatch.

26 : Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Mass. u.a: MIT Press, 1977), 107.

27 : Hilberseimer doesn’t use the term “typology” in his texts but instead describes cells. It is clear that his organisation of the city is dependant on a single unit. That of the cell.

28 : McEwan, Cameron. “Ludwig Hilberseimer and Metropolisarchitecture: The Analogue, the Blasé Attitude, the Multitude.” Arts 7, no. 4 (2018): 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/ arts7040092.

29 : Rem Koolhaas, “The Generic City” in S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995) 1251.

16 Factory2

30 : Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Mass. u.a: MIT Press, 1977), 125.

31 : Rem Koolhaas, “Typical Plan” in S, M, L, XL (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995) 346.

32 : Habraken, N. J. Supports: An alternative to mass housing. London: Architectural Press, 1972. 21.

of the room, produced on an “assembly line” as observed by Tafuri in “Architecture and Utopia.” Each element designed a single time to complete resolution, begins to dissolve into the city, absorbed by the generic qualities of the metropolis. “The architect is an organiser, not a designer of objects”30 Such machine like building processes, inundates the metropolis with homogenised goods. The impact of such general design work was drawn upon by Koolhaas in his essay “Typical Plan” offering the question, “Did the plan without qualities create men without qualities? ”31 The plan which demands nothing yet offers everything, produces a factory for the removal of identity reflecting the nature of society. Society, like a machine, operates most efficiently in the absence of particular influences, the introduction of such elements gives rise to intricacies and from there, variations that break the factory mould, cannot be avoided. “The results of the production line with which we have become so familiar make us accept as a matter of course that uniformity in objects is inescapable. The machine, that device which assumes the absence of man, overwhelms us with uniform products.”32 The pursuit for a streamlined production, reinforces the notion that uniformity in the objects it produces is inevitable. Overshadowing the human influence, in turn fostering a culture of conformity.

33 : Elements of the unknown in the city find themselves in a similar predicament to the alien in a sci-fi film, the instant reaction of humanity is to destroy what is different which in the case of most films results in a negative impact on society. The threat to our generic landscape is too much that instead of adapting to the existence of the particular we find it easier to remove the existence of the particular. Cumbernauld town centre is a key example of this.

The idea of a built generic landscape should, however, not be taken as a suggestion that all buildings are identical. Yet as a realisation of the inherent qualities passed from cell to cell. The architect, no longer the designer of buildings but the composer of a component based system. The design of repetitive cells has an unconscious impact on the psyche driving the self towards a predefined norm. The intention to create a warm culture of knowing as opposed to the fear of the unknown.33 The generic is comforting, we rely on its existence.

17 Glenn Mckerracher

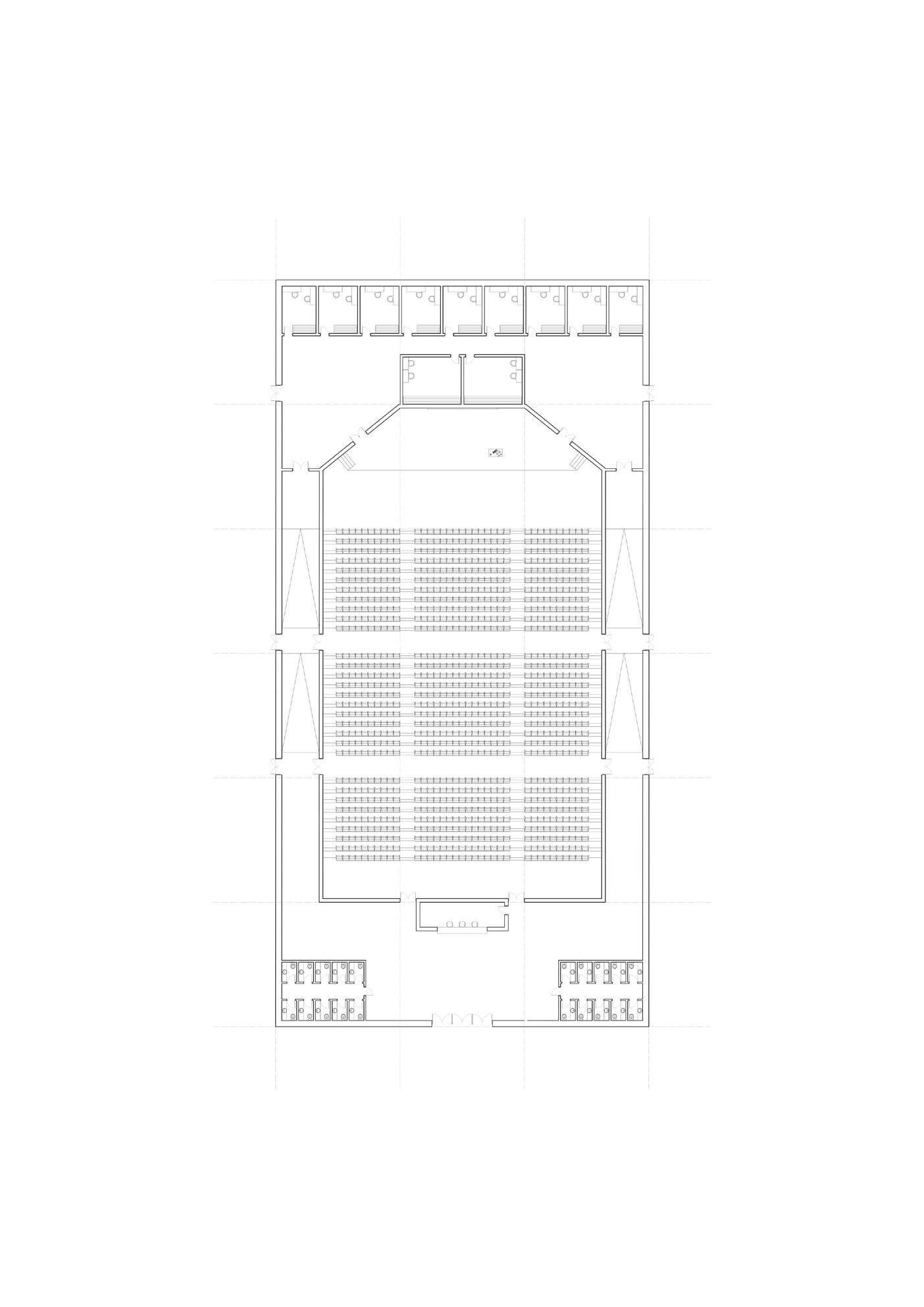

Figure 16 : Author’s Own, 2024. A selection of the typical plans which are used to compose the Social Factory.

The Cell.

Figure 17 : Author’s Own, Summer 2023. This project began its early moves on a trip to Singapore. The Generic City reffered to by Rem Koolhass within his essay.

34 : Mark Featherstone, “Apocalypse Now!: From Freud, through Lacan, to Stiegler’s Psychoanalytic ‘survival Project,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 33, no. 2 (May 12, 2020): 409–31, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11196-020-09715-8, 410.

The Technological : The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

35 : Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), 09.

A new form of individualisation was introduced with the rapid expansion and uptake of the internet, allowing individuals to explore their identity “beyond the limits of the material body.”34 A contemporary method of expressing the self, using the internet as a digital prosthetic. However, the freedom that the internet enabled brought with it hidden measures of control, the cyber realm capitalised on this new image of the self through means of surveillance capitalism. The term coined by Shoshana Zuboff in her book “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism” describes a contemporary economic system of the capitalist metropolis obsessed with the collection and analysis of personal data that is used for commercial purposes. This suggests that companies collate vast holdings of data from individuals’ online habits, behaviour and interactions, to analyse such content to create detailed user profiles. This is then used to predict future behaviours. Surveillance Capitalism turns human nature into a commodity by targeting individuals with highly personalised advertisements, products and services. “It revives Karl Marx’s old image of capitalism as a vampire that feeds on labour, but with an unexpected turn. Instead of labour surveillance capitalism feeds on every aspect of human’s experience”35 Surveillance Capitalism represents a development in the relationship between individuals, technology and the capitalist metropolis bringing to the forefront worrying ethical and societal questions regarding the means in which personal data can be used. The psyche is now in a constant tailored bombardment of capitalist advertisement in order to influence thought.

Capitalising on a Digital Prosthetic

36: Mark Featherstone, “Apocalypse Now!: From Freud, through Lacan, to Stiegler’s Psychoanalytic ‘survival Project,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 33, no. 2 (May 12, 2020): 409–31, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11196-020-09715-8, 411.

37 : Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020) 20.

The introduction of technology to the modern metropolis has transformed the ways in which the psyche of an individual develops. “The self is now a calculation.”36 Where Freud understood the influence of the external world on the ego deriving from tangible elements such as individuals and built forms. The commodification of data and its use to predict behaviours has exposed the human psyche to a new form of influence that is all but impossible to perceive, as it finds itself in a digital realm and influences the ego every day. The identity of a person finds itself endlessly uploaded and downloaded from a global database where it is transformed into valuable data. “If industrial capitalism dangerously disrupted nature, what havoc might surveillance capitalism wreak on human nature”37 Societies reliance on technology

21 Glenn Mckerracher

has eliminated any refuge from the influence of the capitalist city. Global technology corporations now have the ability to bombard the subconscious with targeted information to increase profits. Michael Hardt observes the influence of the digital realm on the individual within his paper “Affective Labour”, “Interactive and cybernetic machines become a new prosthesis integrated into our bodies and minds a lens through which to redefine our bodies and minds themselves.”38 These ‘Persuasion machines’ have been integrated into everyday life with the ability to directly influence people on everyday choices by impacting the ego in a bombardment tailored to suit the thought process of the individual. Surveillance Capitalism acts as a modern development of Tronti’s understanding of the Social Factory, it proves that production now encapsulates society. Even with the addition of new technology and ideas the capitalist metropolis will repeatedly find a way to create profit from every aspect of humanity.

The Big Other - from Lacan to Zuboff

Zuboff depicts Lacans Big Other

39 as the apparatus for which surveillance capitalism is the puppet master. The Big Other is the thirdparty adjudicator which passes symbolic judgement on behaviour, held collectively in the public imaginary. The theoretical eye for which we perform and are wary of. “Big Other combines these functions of knowing and doing to achieve a pervasive and unprecedented means of behavioural modification”40 Thus, possessing instrumentarian power equipped for the engineering of human behaviour. We are strictly organisms that react, seeking the ideal dictated by Big Other. The role of architecture provides a means of facilitation, generating a landscape of “certainty without terror.”41 Comfort in the knowing there is a norm set by the Big Other. The power to dictate this norm, held by the owner of production.

Figure 18 : Shosanna Zuboff, 2019. The cycle used by Zuboff to depict the production of surveillance capitalism.

38 : Michael Hardt, “Affective Labor,” boundary 2, Summer, 1999, Vol. 26 (1999) : 89-100.

39 : Often just Other as shown in the writing of Lacan, with the O capitalised to distinguish from the use of the word other in text.

40 : Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), 376.

41 : Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), 378.

22 Factory2

Surveillance Capitalism in the Typical Flat

Figure 19 : Author’s Own, 2024. Small flat type plan and elevation of the Social Factory inhabited wall showing the extents of Surveillance Capitalism.

23 Glenn Mckerracher

20 : Author’s Own, 2024. Methods of Surveillance within the Social Factory flat.

24 Factory2

for Profit The Law

Personalised

Surveillance

in Your Home

Advertisement

Figure

Andreas Gursky

: Photography of the Generic

The German photographer Andreas Gursky known globally for his large format images of architecture and the public realm could be considered to depict the generic self. A selection of three of his images visualise a the current standing of a generic psyche through global snapshots.

The Mental Generic PYONGYANG II (2007)

Figure 21 : Andreas Gursky, 2007. Individuals acting in a generic manner at the annual Arirang Festival. This acts as a realisation of city ten from Superstudios “Twelve Cautionary tales for Christmas” where the inhabitants were taught to suit the city.

The Built Generic MONTPARNASSE (1993)

Figure 22 : Andreas Gursky, 1993. The Built Generic, repetitive cells combine to form a wall of housing within Montparnasse, Paris

Figure 22 : Andreas Gursky, 1993. The Built Generic, repetitive cells combine to form a wall of housing within Montparnasse, Paris

The Technological Generic AMAZON (2016)

Figure 23 : Andreas Gursky, 2016. Within the warehouse of Amazon the forces of global capitalism are shown via the global online giant.

Figure 23 : Andreas Gursky, 2016. Within the warehouse of Amazon the forces of global capitalism are shown via the global online giant.

42 : Tronti was one of the first theorists to develop the term “Social Factory” published in the paper, Factory and Scoiety in the 1960’s. The paper was first published in the second edition of Quaderni Rossi, an Italian political journal founded by Tronti along with other like-minded individuals such as Raniero Panzieri and Antonio Negri.

43 : Mario Tronti, “Factory and Society,” trans. Guio Jacinto, Operaismo in English, June 13, 2013, https://operaismoinenglish. wordpress.com/2013/06/13/factoryand-society/.

The City as a Social Factory; The Social Factory as the City

A Factory-Society State

Connections between the capitalist metropolis and the factory commonly cross paths as profit takes priority over people in the city. For this reason, in his text “Factory and Society”, Mario Tronti42 looked beyond production and consumption as moments within the city and understood every function within the city as a process of constructing commodities. The theory was conceived by Tronti in the twentieth century, as the capitalist metropolis existed within a compact format. During this period, the dense factory-like conditions of the city shared a clear boundary with the countryside, since then the boundaries between city and nature have further blurred, as have the boundaries between factory and society. “We no longer have simply the means of production on the one hand, and the worker on the other, but all the conditions of labour, on the one hand and the worker, which labours, on the other; labour and labour-power opposed one to the other and both united within capital.”43 The conditions of labour now extend from the factory, into the entirety of the social plane which is inhabit by the worker. All of society lives within the factory, in turn, the factory extends its reach over the whole of society. Not only are goods produced within it, but social values and norms are produced and maintained across the civilization to support the capitalist system. From an urban outlook, the Fordist nature of the Social Factory

33 Glenn Mckerracher

represents the starting point in which every built aspect of the city, (factories, residential areas, and recreational spaces) along with urban functions (employment, residence, and leisure), are commodified and organized in alignment with the production system.

Advancements in the scope of factory production have allowed for the transformation of every element of human experience into a commodity, as a result, the perception of what constitutes economic value is now altered. Physical goods are now no longer the sole commodity but the human process of creating them and all stages in between also find themselves itemised. “For Tronti the main principle of capitalism’s power is thus its ability to conflate “living labour” (workers cooperation, the productive force that creates value) with dead labour (value in itself)”44 The merging of labour and value serves as the linchpin of the capitalist cities dominance, enabling a relentless extraction of surplus value from society, reinforcing the systematic top-down inequalities entrenched within modern capitalist structures. Hardt draws comparisons between industrialisation and the commodification of humanity, bluring the division between manufacture and society. “The processes of modernization and industrialization transformed and redefined all the elements of the social plane.”45 Putting to work the most generic qualities of human existence; to speak, to move, to think. These are to be considered

Figure 24 : Tano D’Amico, 1977. Women ready to resist the police when faced with the risk of eviction in a tin shed. His works contextualise the feeling within Italy during the time of Tronti’s writing. Also depicting workerist organizations that Mario Tronti was engaged with.

44 : Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture within and against Capitalism (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008) 33.

45 : Michael Hardt, “Affective Labor,” boundary 2, Summer, 1999, Vol. 26 (1999) : 89-100.

34 Factory2

46 : Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture within and against Capitalism (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008) 33.

the most generic qualities of human nature as they are common to all. In the Social Factory, the generic is not solely the consequence of its process; rather, the fundamental raw material manipulated by economic forces. “Referring to Marx, Tronti emphasized the two faces of capitalist production; production process and value process. In the first process, workers use the machines; in the second the machines use the workers”46 Machines are substituted for living labour. Within this condition, people are used to manufacture, not machines. In this sense, the role of architecture becomes liberated from programmatic or spatial duties serving society as a framework

35 Glenn Mckerracher

.

Raw Material Processing Production Assembly Quality Control Logistics Revenue

import of loose material to supply production.

The

of loose material

supply production.

The import

to

material

production. The import of loose material to supply production. The import of loose material to supply production. The import of loose material to supply production. 01 04 05 02 03 06

The import of loose

to supply

The flow of social production

The Social Factory

Figure 25 : Author’s own, 2024. Typical Flow of Factory Production.

No-Stop Factory

As the factory takes hold of the city in its entirety, its presence within society becomes indistinguishable. The boundary between the two becomes increasingly blurred, rendering it impossible to discern where one ends and the other begins. “When the factory seizes the whole of society—all of social production is turned into industrial production-the specific traits of the factory are lost within the generic traits of society. When the whole of society is reduced to the factory, the factory—as such—appears to disappear.” 47 As production reaches its pinnacle, it leads to a complete obscuring of social relations, in turn masking the true nature of power dynamics within society. The capitalist city transforms all social connections, their relationships obscured, blurring the lines between economic labour and everyday life. Archizoom’s theoretical project “No-Stop City” depicts the blurring of productive and societal processes through the infinite expansion of a capitalist city. The project, a realisation of capitalisms limitless growth in which architecture now ceases to exist, depicts the homogenisation of both production and value processes by replication of a grid. The grid only ever interrupted by symbolic walls and natural landscape features. Its infinite nature renders it impossible to recognise that you are within it.

47 : Mario Tronti, “Factory and Society,” trans. Guio Jacinto, Operaismo in English, June 13, 2013, https://operaismoinenglish. wordpress.com/2013/06/13/factoryand-society

36 Factory2

Figure 26 : Archizoom, 1972. No-Stop City Plan.

48 : This number selected as it is both current population of Cumbernauld and it bears a relationship to the group research project.

49 : Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 13.

A City of Production for Consumption

The Social Factory uses the most critical urban conditions as the basis for a design project. A city conceived as a factory dedicated to a sole purpose; the production of the generic self. In this sense, the city is what it does, a literal representation of modern society, consuming raw materials and producing commodities for further consumption. As referred to in the opening pages, the laboratory for this vision is the condemned Cumbernauld Town Centre. The centralised institution a social factory, taking its orientation from neighbouring towns and cities with a population greater than 50,000.48 The project is not so reliant on place but the peripheral relationship between places, represented as lines in the landscape. “The overall plan for the city that would link the form of city with its productive and economic forces and the definition of a single inhabitable cell”49 A new strategy for city centre design which reveals its true nature, in time to be phased out

39 Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 28 : Author’s Own, 2024. The connected expansion of the Social Factory across the central belt region of Scotland.

over the central belt, the UK, the globe. “Since these cells are elements reproducible ad infinitum, they conceptually embody the prime structures of a production line which excludes the old concepts of “place” or “space.”50 The project sets out to sharpen the distinction between factory and society in capitalist cities. Factory enclosed within the centre, a wall inhabited by factory workers creating a boundary and society consuming on the exterior of the wall.

50 : Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Mass. u.a: MIT Press, 1977) 105.

40 Factory2

51 : Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, Dogma: 11 Projects (London: Architectural Association, 2013) 12.

52 : Ibid. 05

The Wall as a Limit

The inhabited wall takes the form of a square, framing a lens to which the Social Factory will be revealed. “At the moment in which the premises to that project are no longer a (utopian) projection, but an acute and sarcastic analysis of the reality in which we live.”51 Using similar principles to Dogma in many of their city projects, the decision to use a square as a means of testing allows for more complex societal issues to be examined. “As the architects themselves have written, the choice of square has always seemed the easiest means by which to focus on larger, more pressing architectural issues...”52 Abstracting the reality of the city to a set of conditions, from which emerge architectural and urban design principles. Instead of unlimited urban expansion, as seen in projects such as No-Stop City, the project assumes an urbanism made of finite yet replicable forms who’s organization requires both architecture and planning to coincide.

53 : Pier Vittorio Aureli and Maria Shéhérazade Giudici, Rituals and Walls. the Architecture of Sacred Space (London: Architectural Association, 2016). 15.

The wall acts as both boundary and urban condition. Both a medieval city wall and a new means of urban grid, flipped on a vertical plane instead of on the ground. The nature of a wall is that its existence instantly creates two conditions; an internal and an external. Depicted in a similar way to Athanasius Kircher’s, Topographia Paradisi Terrestris. “A verdant garden clearly seperated from the arid territory beyond its walls, which is depicted as limitless and thus hostile.”53 Each condition finds itself with separate laws, norms and landscapes. Humanity often has a longing to be on the inside of the wall, comforted by the control that enclosure it provides.

41 Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 29 : Dogma, 2011. A Simple Heart.

Figure 30 : Dogma, 2008. Stop-City

Figure 31 : Athanasius Kircher, c1675. Topographia Paradisi Terrestris

Figure 29 : Dogma, 2011. A Simple Heart.

Figure 30 : Dogma, 2008. Stop-City

Figure 31 : Athanasius Kircher, c1675. Topographia Paradisi Terrestris

42 Factory2

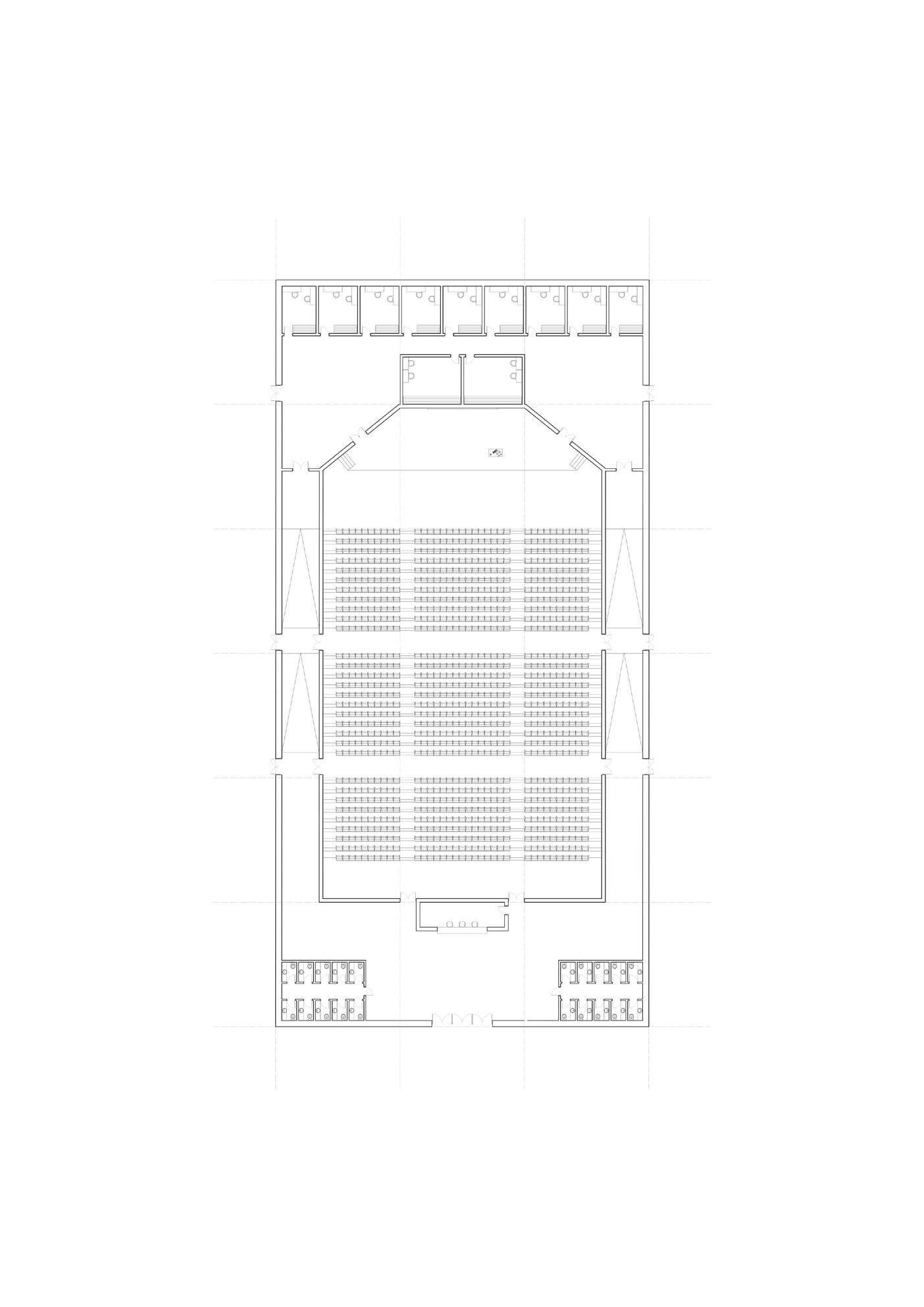

Figure 32 : Authors own, 2024. The Social Factory

Cycles of Production and Consumption

This interpretation of the Social Factory is concerned with the production of the generic self. Producing the three spheres that combine to influence such reaction, the Social Factory can be broken down into a series of three factories. The first, an Edu Factory, producing a generic mental state within its workers. Drawing inspiration from Superstudio’s “Twelve cautionary tales for Christmas” workers within this factory will be taught how to act and live within the Social Factory, a new education method. The work here is learning. “Instead of trying to suit the city to its inhabitants, like everyone else, he thought of suiting the inhabitants to their city.”54 The second factory, a typology factory concerned with the production of generic modular buildings. This will be the first factory to be built, initially used for building the wall in which the factory workers will live, then used to build the other two factories which combine to make up the Social Factory and finally will be used to aid the building of other social factories in the expansion of the project to other city centres. Finally, the data factory, producing human behaviour prediction material as a result of surveillance capitalism. Using data harvested from every aspect of factory workers existence from internal home surveillance to mobile phone use, the product will be traded to corporations to allow them

43 Glenn Mckerracher

54 : Peter Lang and William Menking, “Twelve Cautionary Tales for Christmas” in Superstudio: Life without Objects (Milano: Skira, 2003). 159.

Figure 33 : Cedric Price, 1966. Potteries Thinkbelt perspective drawing.

to target personalised advertisements to workers. Upon moving into the Social Factory workers will receive a copy of “The Factory Workers Manual” to assist them in navigating their workspace.

Just as within a factory assembly line, a conveyor belt will move raw material (building materials, people and data) along with factory workers from the beginning to the end of the productive flow. Taking the form of a metro line, this “belt” will run throughout the day and night to facilitate the factory process. Just as in factory production, the belt will not stop55. “Circulation does not simply move bodies, but subtly forces them to follow predefined trajectories. We no longer move from place to place but from A to B.”56 The belt transport system will run onwards from the factory to other Social Factories with the expansion of the scheme. Cedric Price’s proposal for the Potteries Thinkbelt utilised the rusting rail network of North-Staffordshire as a flexible connected network with the capacity to adapt and develop. The use of rail, similar to this project, allows the system to function as an enlarged campus, developing the Central Belt as a whole. An exposed archipelago of societal factories across Scotland’s central region.

55 : Production may stop for essential maintenance, in the event of this workers will be notified as soon as possible.

56 : Márquez Cecilia and Richard Levene, Dogma (2002-2021): Familiar/Unfamiliar (Madrid: El Croquis, 2021).

44 Factory2

57 : Ludwig Hilberseimer et al., Metropolisarchitecture (Gsapp Books, 2012). 335

Urban Radiography

58 : Oswald Mathias Ungers et al., The City in the City. Berlin: A Green Archipelago (Ennetbaden: Lars Müller Verlag, 1977), 31.

The project, neither a proposal for a new city nor a dystopian transformation of an existing one, is to be considered an X-ray of the existing capitalist metropolis in which the factory has taken hold of society. As with that of Hilberseimer in Hochhausstadt, it depicts a reality of the urban realm. “The urban atmosphere evoked by his drawings for the High-rise City is neither futuristic, nor dramatic nor dystopian. Hilberseimers images especially in his early work describe an urban atmosphere which is detached, harsh, precise and subtly disquieting.”57 This considered, exaggerated image of a modern metropolis looks to depict the bleak condition of the realm in which we inhabit. It’s intention more so to understand the current trajectory of the city under its existing conditions. “The point is not to change the world but rather to anticipate its necessary evolution, the utopian project suddenly assumes the speculative form of a scenario well suited to illuminating and intensifying an emerging reality.”58 The working shift within the Social Factory is never-ending, workers always on the clock. This vision depicts a method in production of commodities, be it known or unknown to the raw material from which they are produced.

45 Glenn Mckerracher

46 Factory2

Figure 34 : Author’s Own, 2024. View along the Data Factory Line.

35 : Author’s Own, 2024. Site Strategy Plan.

Figure

Figure

Figure 36: North Lanarkshire Archives, 1965. Cumbernauld Town Centre under construction.

Figure 36: North Lanarkshire Archives, 1965. Cumbernauld Town Centre under construction.

Clocking Out

The modern capitalist metropolis has created a generic condition for its inhabitants, with profit as the generator for this. The ideas of Mario Tronti, emerging from the Italian workerist movement, frame the perspective through which we can view the city in such condition. “Capital is able to capture, it in its own way, the unity of the labour process with the process of valorization”59 The city and the mind find themselves incredibly interconnected, as an internal cognition reflects the urban conditions of one’s dwelling. The exposed mental state modernises the thought of Simmel, as conditions of the city evolve. The generic self represents the response of the people to the grasp of the capitalist state. The influences highlighted can be described as the three key interactions of a person as they negotiate their daily life. An indiscriminate response to a highly commodified and profit-driven landscape. It is clear that society has followed a trajectory uncovered by Tronti and Simmel.

The worker serves as a metaphor for all inhabitants of the metropolis in its most extreme conditions. A metaphor for the subject who deliberately accepts the reality of the city, or perhaps is unable to know otherwise. Today living is reduced to mechanisms of production and reproduction. Free space subsumed by production creates a condition where living and working are one and the same. Mario Tronti’s insights underscore how every facet of the city, from physical infrastructure to social norms, is commodified to serve the capitalist system. This commodification extends beyond goods to encompass human labour itself, blurring the boundaries between living and dead labour and reinforcing systemic inequalities. “In political terms this is a realist strategy: institutions have to maintain the forces against them and not eliminate them in order to keep their political validity.”60 This vision of the city seeks to provide a theory of societal organisation in the form of an architectural project. Architecture is reduced to its essential form, in order to make this condition visible. Not a proposal for change but a scenario set out to highlight the reality of our urban landscape.

59 : Mario Tronti, “Factory and Society,” trans. Guio Jacinto, Operaismo in English, June 13, 2013, https://operaismoinenglish. wordpress.com/2013/06/13/factoryand-society

60 : Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, “A Simple Heart” in Dogma: 11 Projects (London: Architectural Association, 2013) 20.

50 Factory2

Appendix

A further two documents supplement this thesis project....

The Social Factory The Factory Workers Manual

The Factory Workers Manual

The guidebook for navigating work and life in the Social Factory presented to each worker as they move in to their flat.

51 Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 37: Author’s Own, 2024. The Factory Workers Manual Cover.

Project Design Journal

The development and design of the project showing the stages of change it took.

52 Factory2

Figure 38: Author’s Own, 2024. Design Journal Cover.

Glenn Mckerracher rooms+cities

Factory2

Social Production and its Discontents.

Design Journal.

Bibliography.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio, Gabriele Mastrigli, and Brett Steele. Dogma: 11 projects. London: Architectural Association, 2013.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio, and Martino Tattara. Living and working. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2022.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio, and Maria Shéhérazade Giudici. Rituals and walls. the architecture of Sacred Space. London: Architectural Association, 2016.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. The project of autonomy: Politics and architecture within and against capitalism. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008.

Banham, Reyner. Megastructure: Urban Futures of the recent past. New York: The Monacelli Press, 1976.

Carignani, Paolo. “‘Psyche Is Extended’: From Kant to Freud.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 99, no. 3 (April 27, 2018): 665–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207578.2018.1425876.

Cecilia, Márquez, and Richard Levene. Dogma (2002-2021): familiar/ unfamiliar. Madrid: El Croquis, 2021.

Derrida, Jacques. On touching, Jean-Luc Nancy. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 2005.

Featherstone, Mark. “Apocalypse Now!: From Freud, through Lacan, to Stiegler’s Psychoanalytic ‘survival Project.” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique 33, no. 2 (May 12, 2020): 409–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196020-09715-8.

Freud, Sigmund. Civilisation and its Discontents. London: Penguin Books, 2004.

Freud, Sigmund. “Findings, Ideas, Problems (1941).” Standard Edition, 1971, 299–300.

53 Glenn Mckerracher

Gandelsonas, Mario. X-urbanism: Architecture and the American city. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

Habraken, N. John. Supports: An alternative to mass housing: Translated from the Dutch by B. Valkenburg. Translated by B. Valkenburg. London: Architectural Press, 1972.

Hilberseimer, Ludwig, Julie Dawson, Richard Anderson, and Pier Vittorio Aureli. Metropolisarchitecture. Gsapp Books, 2012.

Holm, Lorens. Reading architecture with Freud and Lacan shadowing the public realm. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022.

Koolhaas, Rem, and Bruce Mau. S M L XL: OMA. New York: Monacelli Press, 1995.

Lang, Peter, and William Menking. Superstudio: Life without objects. Milano: Skira, 2003.

McEwan, Cameron. “Ludwig Hilberseimer and Metropolisarchitecture: The Analogue, the Blasé Attitude, the Multitude.” Arts 7, no. 4 (November 27, 2018): 92. https://doi. org/10.3390/arts7040092.

Simmel, Gerog. The Metropolis and Mental Life. In On individuality and social forms: Selected writings. Edited by Donald Nathan Levine. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1971.

Tafuri, Manfredo. Architecture and utopia: Design and capitalist development. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1979.

Tafuri, Manfredo. The sphere and the labyrinth: Avant-gardes and architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987.

Tronti, Mario. “Factory and Society.” Translated by Guio Jacinto. Operaismo in English, June 13, 2013. https://operaismoinenglish. wordpress.com/2013/06/13/factory-and-society/.

Ungers, Oswald Mathias, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Riemann, Hans Kollhoff, and Arthur Ovaska. The city in the city. Berlin: A green archipelago. Ennetbaden: Lars Müller Verlag, 1977.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books, 2018.

54 Factory2

Image References

Figure 1 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cover.

Figure 2 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld Town Centre penthouses.

Figure 3 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld component section. rooms+cities: book 02 - rooms.

Figure 4 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld centric plan. rooms+cities: book 03 - cities.

Figure 5 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld non-centric plan. rooms+cities: book 03 - cities.

Figure 6 : D’Amico, Tano. 1977. Movimento del ‘77 Roma. Accessed on Apr 20,2024. https://www.stsenzatitolo.com/st/exhibitions/tanodamico-disordini/

Figure 7 : Author’s Own, 2024. The influences of the generic self in relation to factory process which drive it.

Figure 8 : Lagendorf, Ricahrd. 1970. Cumbernauld Town Centre prior to peripheral development. North Lanarkshire Council Archives

Figure 9 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld Town Centre stripped of its identity.

Figure 10 : Author’s Own, 2023. Taxonomy of Peripheral Landscape Strips.

Figure 11 : Author’s Own, 2024. Influences of the generic self in relation to factory process which drive it.

Figure 12 : Freud, Sigmund. 1923. Structural Model of the Mind. Accessed on Jan 28, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/ Freuds-structural-model-of-the-mind-Freud-1923-1925-1961b_ fig1_237072290

55 Glenn Mckerracher

Figure 13 : Author’s Own, 2024. Cumbernauld in Ville Contemporaine.

Figure 14 : Hilberseimer, Ludwig. 1924. Hochhausstadt perspective. Accessed on Apr 20,2024. https://twitter.com/loouisfernandes/ status/692090753754009600 drawing.

Figure 15 : Hilberseimer, Ludwig. 1924. Hochhausstadt perspective drawing. Accessed on Apr 20,2024. https://www.artic.edu/ artworks/101044/highrise-city-hochhausstadt-perspective-view-northsouth-street

Figure 16 : Author’s Own, 2024. Typical Plans of the Social Factory.

Figure 17 : Author’s Own, 2023. Singapore Skyline.

Figure 18 : Zuboff, Shosanna. 2019.Behavioural Surplus cycle. Accessed on Jan 28, 2024. https://blog.uvm.edu/ aivakhiv/2020/06/29/we-are-surveillance-capital-stock/

Figure 19 : Author’s Own, 2024. Small flat type plan and elevation.

Figure 20 : Author’s Own, 2024. Methods of Surveillance within the Social Factory flat.

Figure 21 : Gursky, Andreas. 2007. Pyongyang III. Accessed on Dec 10, 2023. https://ocula.com/art-galleries/white-cube/artworks/andreasgursky/pyongyang-iii/

Figure 22 : Gursky, Andreas. 1993. Paris, Montparnasse. Accessed on Dec 10, 2023. https://www.andreasgursky.com/en/works/1993/parismontparnasse

Figure 23 : Gursky, Andreas. 2016. Accessed on Dec 10, 2023. Amazon. https://www.andreasgursky.com/en/works/2016/amazon

56 Factory2

Figure 24 : D’Amico, Tano. 1977. Donne e polizia. Accessed on Apr 20, 2024. https://www.avvenire.it/multimedia/pagine/mostra-l-alacreativa-del-movimento-del-77-nelle-foto-di-tano-d-amico-e-neidisegni-di-pablo-echaurren

Figure 25 : Author’s own, 2024. Typical Flow of Factory Production.

Figure 26 : Archizoom, 1972. No-Stop City Plan. Accessed on Jan 28, 2024. https://architectuul.com/architecture/no-stop-city

Figure 27 : Author’s Own, 2024. A view from a flat within the Social Factory.

Figure 28 : Author’s Own, 2024. The connected expansion of the Social Factory across the central belt region of Scotland.

Figure 29 : Dogma, 2011. A Simple Heart. Accessed on Jan 28, 2024. https://www.gizmoweb.org/2011/03/a-simple-heart/

Figure 31 : Kircher, Athanasius. c1675. Accessed on Apr 20,2024. Topographia Paradisi Terrestris. http://thecityasaproject.org/2011/07/ paradise/

Figure 30 : Dogma, 2008. Stop-City . Accessed on Apr 20,2024. https://socks-studio.com/2011/07/10/stop-city-by-dogma-2007-08/

Figure 32 : Authors own, 2024. The Social Factory site plan.

Figure 33 : Price, Cedric. 1966. Potteries Thinkbelt perspective drawing. Accessed on Apr 20,2024. https://morethangreen.es/en/ potteries-thinkbelt-by-cedric-price/

Figure 34 : Author’s Own, 2024. Perspective view along the Data Factory Line.

Figure 35 : Author’s Own, 2024. The Social Factory site plan.

Figure 36: North Lanarkshire Archives, 1965. Cumbernauld Town Centre under construction.

Figure 37: Author’s Own, 2024. The Factory Workers Manual Cover.

Figure 38: Author’s Own, 2024. Design Journal Cover.

57 Glenn Mckerracher

58 Factory2

Factory2 Glenn Mckerracher

A Master’s Thesis submitted to: School of Architecture

Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design University of Dundee

Figure 2 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld’s now uninhabited penthouses, photographed on a group site visit to the town centre.

Figure 2 : Author’s Own, 2023. Cumbernauld’s now uninhabited penthouses, photographed on a group site visit to the town centre.

Figure 5 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld non-centric plan

Figure 5 : rooms+cities, 2024. Cumbernauld non-centric plan

Figure 6 : Tano D’Amico, 1977. The autonomous student movement Movimento del ‘77 pictured in Roma. The photographs of D’Amico’s depict social and political unrest in Rome, Florence, Milan, and other parts of Southern Italy between 1969 and 2019. His works contextualise the feeling of workerist organizations that Mario Tronti was engaged with.

Figure 6 : Tano D’Amico, 1977. The autonomous student movement Movimento del ‘77 pictured in Roma. The photographs of D’Amico’s depict social and political unrest in Rome, Florence, Milan, and other parts of Southern Italy between 1969 and 2019. His works contextualise the feeling of workerist organizations that Mario Tronti was engaged with.

Figure 8 : Ricahrd Lagendorf, 1970. Cumbernauld Town Centre prior to peripheral development.

Figure 8 : Ricahrd Lagendorf, 1970. Cumbernauld Town Centre prior to peripheral development.

Figure 13 : Author’s Own, 2024. Cumbernauld in Ville Contemporaine. Ville Contemporaine was the project to which Hochhausstadt was a response.

Figure 13 : Author’s Own, 2024. Cumbernauld in Ville Contemporaine. Ville Contemporaine was the project to which Hochhausstadt was a response.

Figure

Figure

Figure 22 : Andreas Gursky, 1993. The Built Generic, repetitive cells combine to form a wall of housing within Montparnasse, Paris

Figure 22 : Andreas Gursky, 1993. The Built Generic, repetitive cells combine to form a wall of housing within Montparnasse, Paris

Figure 23 : Andreas Gursky, 2016. Within the warehouse of Amazon the forces of global capitalism are shown via the global online giant.

Figure 23 : Andreas Gursky, 2016. Within the warehouse of Amazon the forces of global capitalism are shown via the global online giant.

Figure 29 : Dogma, 2011. A Simple Heart.

Figure 30 : Dogma, 2008. Stop-City

Figure 31 : Athanasius Kircher, c1675. Topographia Paradisi Terrestris

Figure 29 : Dogma, 2011. A Simple Heart.

Figure 30 : Dogma, 2008. Stop-City

Figure 31 : Athanasius Kircher, c1675. Topographia Paradisi Terrestris

Figure

Figure

Figure 36: North Lanarkshire Archives, 1965. Cumbernauld Town Centre under construction.

Figure 36: North Lanarkshire Archives, 1965. Cumbernauld Town Centre under construction.