In the late 1950s, the Washington D.C. area was a focal point of racial tension and civil rights activism. The city, like much of the United States, was grappling with the legacy and reality of segregation African Americans in the capital were fighting for desegregation in schools, public facilities, employment, and housing. It was a time of hope and frustration, as progress was slow and met with resistance.

In Glen Echo Park history, the summer of 1960 is often referred to as the “Summer of Change,” because it was then that a group of Howard University students organized themselves as the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG) to combat racism and segregation in the D.C. area and chose the now-defunct Glen Echo Amusement Park as one of their first protests

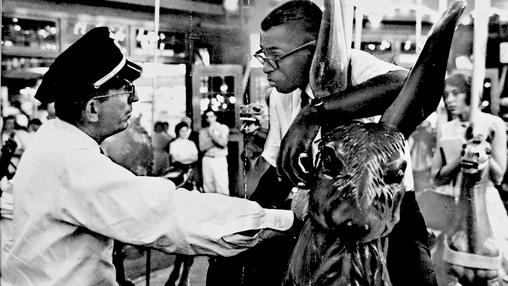

The protest began on June 30, when thirteen NAG members, both Black and White, crossed through the entrance of the privately-owned, segregated Glen Echo Amusement Park the students seated themselves on the carousel animals. Seeing that there were Black students in the group, the carousel operator refused to start the ride This launched a standoff; two and a half hours later, five Black students were arrested for trespassing

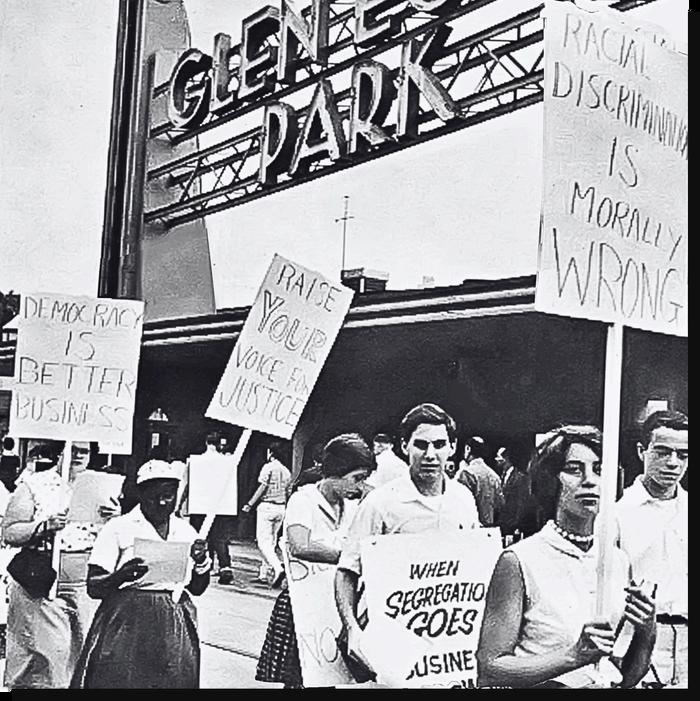

White community members from the nearby Bannockburn neighborhood were already challenging the amusement park’s segregation rule, so when NAG activists returned the following day, their numbers were quickly boosted by local residents. Union members from the national labor movement also joined the cause. The picket line continued every day that summer, with numbers ranging from 25 to hundreds. Protesters endured 90 degree heat, threats of violence, and a counterprotest organized by George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi Party.

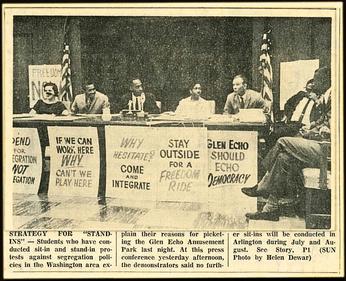

Throughout the summer, local press wrote articles that helped publicize the protests and attract more supporters By August, celebrities and national figures began to speak out. What began with a few young members of NAG, now was a powerful movement that echoed protests in North Carolina, Atlanta, and New Orleans.

The Glen Echo Amusement Park protests ended on September 11, when the park closed for the season. Over that winter, U S Attorney General Robert Kennedy intervened, and by March 14, 1961, the private owners of the Glen Echo Amusement Park had abandoned their segregation practices When the park opened again for a new season in the summer of 1961, it was open to all, and it remained so until the permanent closing of the amusement park and its rides in 1968

Inspired by protests in Greensboro, North Carolina, a group of students at Howard University formed NAG to combat racism and segregation in Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. Many of the students became Freedom Riders, riding buses to segregated states to participate in sit-ins and other protests.

The protestors from NAG included:

Gwendolyn Britt** (née Green) was a Howard University student and went on to become a Maryland State Senator for Prince George’s County (District 47)

Dion Diamond was a Howard University student who became a Freedom Rider and was arrested many times as part of his activism; later, he was a consultant on race relations for several government agencies.

Reverend Laurence Henry was a divinity student at Howard University and led a number of desegregation efforts in Montgomery County; he later became pastor of Christ Community Baptist Church in Philadelphia

Joan Trumpauer Mulholland had been a student at Duke Univeristy when she joined the Howard University Students in NAG She went on to become a Freedom Rider and help plan the March on Washington.

Michael Proctor** was a Howard University student who went on to lead protests at segregated lunch counters in Northern Virginia

Hank Thomas was a Howard University student who went on to become one of the original 13 Freedom Riders who traveled on buses throughout the South in 1961; he is featured in the National Park Service's International Civil Rights Walk of Fame at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site.

Marvous Saunders** was the Howard University student featured in a famous photo (below) speaking with an amusement park security guard on June 30, 1960, when the protests began.

Bannockburn was a nearby neighborhood formed by Catholic and Jewish families who had experienced discrimination in the housing market. The neighborhood had a strong communal atmosphere, and many of the families joined in the protest.

Bannockburn protestors included:

Esther Delaplaine was an activist working to bring about a public accommodations law in Montgomery County. She often brought her children to the protest.

Hyman Bookbinder was a Washington lobbyist and a champion of Jewish causes and social justice.

Sally and Edmond Rovner brought their two young children to join the picket line.

Tina Clarke, along with her family, was refused entrance to Glen Echo Amusement Park when she was a child, and she joined in NAACP protests at the park. She went on to become a teacher in the Montgomery County Public Schools and the first Director of the Montgomery County Office of Human Rights.

Edith Bryant Shorts was 12 years old when she marched on the picket line and longed to enter the park and ride the carousel She went on to work in employee development for the federal government

This is not a full list of protesters. There were many more individuals who joined the cause and picketed for the rights of Black Americans to participate in the activities of the amusement park. p y y Saunders speaks with an amusement park security guard on June 30, 1960; Far Left: Mug shot of Dion Diamond when he was arrested as a Freedom Rider in Jackson, Mississippi

**One of the five students arrested on June 30, 1960

Park Entrance: The Glen Echo Amusement Park protests took place just outside the amusement park’s main entrance, which is now one of two entrances to Glen Echo Park. This entrance has the same iconic neon sign that protesters marched in front of in 1960

Dentzel Carousel: The 1921 Dentzel carousel that Black students attempted to ride in defiance of the privately-owned amusement park’s segregation policies is still the jewel of the Park. The carousel is open to the public from May through September.

Sit where history was made! Ride the same animals the protestors rode during their sit-in.

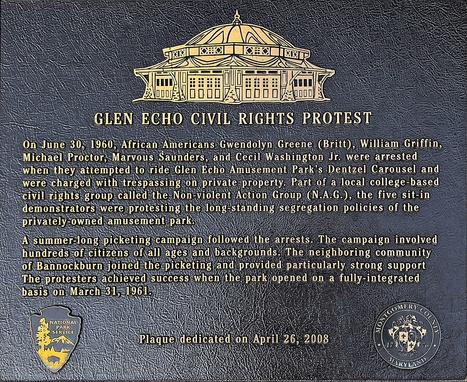

Commemorative Plaque: Dedicated in 2008, a plaque to commemorate the protests sits on a large rock across from the carousel entrance.

The Glen Echo Park Partnership for Arts and Culture is supported in part by the Maryland State Arts Council and also by funding from the Montgomery County Government and the Arts & Humanities Council of Montgomery County All programs are produced in cooperation with the National Park Service and MontgomeryCounty,Maryland

For many years, the Glen Echo Park Partnership for Arts and Culture and our major partners have been proud to commemorate the protests and tell this important story

2005 | “Summer of Change” Protesters

Reunion (45th Anniversary)

2008 | Installation of a Plaque dedicated to the protesters in front of the carousel

2010 | 50th Anniversary event commemorating the “Summer of Change” protests

Unless otherwise indicated, photos in this

2023 | Juneteenth “Freedom Festival” honoring the protesters (63rd Anniversary)

are from the

A film about the protests Ain’t No Back to a Merry-Go-Round by award-winning filmmaker llana Trachtman is currently being shown in documentary film festivals throughout the country

Learn more about the film and where it’s showing at aintnoback.com

In 2025, the National Park Service developed a Glen Echo Park Civil Rights & History Tour that is presented on the first Saturday of each month. Learn more at glenechopark.org/majorpartners.

Download this brochure and find more information on the park’s civil rights story at glenechopark.org/civil-rights

Our major partners: National Park Service Montgomery County, Maryland