BEY ND THE GAME

A Strategic Mobility Network in Stadium Districts for Urban Vibrancy

A Strategic Mobility Network in Stadium Districts for Urban Vibrancy

UNIVERSITY OF DETROIT MERCY SACD FALL 2024 - WINTER 2025

MASTER THESIS STUDIO ARCH 5100-5200

THESIS RESEARCH METHODS ARCH 5110-5210

THESIS STUDIO ADVISOR: VIRGINIA STANARD

THESIS RESEARCH METHODS ADVISOR: CLAUDIA BERNASCONI

EXTERNAL ADVISOR: ALEXANDER WRIGHT

A Strategic Mobility Network in Stadium Districts for Urban Vibrancy

Copyright © 2025 by Giovanni Zora. All rights reserved.

The contents of this publication are protected under copyright law. No part of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

I, Giovanni Zora certify that I have not used Generative Al in any way to write this Thesis Book.

This thesis book was submitted to the Graduate Program in Architecture at the University of Detroit Mercy to fulfill the academic and professional requirements for a Master of Architecture degree.

Printed by Lulu Press Inc., in the United States of America.

To God, for providing me guidance throughout this journey and having impeccable timing, reminding me that at the right moment, everything comes to fruition just as it was meant to. My heartfelt thanks go to my family for their immense understanding and patience during this long journey. I appreciate all my advisors: Virginia, for the endless resources and for always being available to answer my questions; Claudia, for pushing me to strive to learn alongside her insightful guidance; and Alex, for taking time out of his busy schedule as the co-owner of Detroit City Football Club to provide me with insight into their stadium development process. I appreciate everyone who has played a part in this journey, whether they answered one question for me or took hours out of their day to help.

Landmarks are physical objects that serve as public reference points, and considered to be mostly external to the observer (Lynch, 1960). In The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch elaborates on the concept of landmarks as essential components in urban environments, classifying landmarks as one of the five key elements required within a city. A structure that often serves this role is a stadium, shaping how we perceive and connect with the city around us. Stadia, the Latin plural of stadium, are the foundation of any major urban city. Characteristically, a stadium is a venue designed for hosting sporting events and entertainment. New stadia are intended to serve as billboards for their hometowns and accelerate urban redevelopment. Another aspect Kevin Lynch highlights is the importance of paths, which is an additional key element required within a city. He describes paths as “the channels along which the observer customarily, occasionally, or potentially moves.” These channels may be streets, boulevards, and avenues, as well as waterways, railroads, or any other means used for moving through the city.

Efficacious urban planning can help mitigate operational and social vulnerabilities, balance and optimize complex human-space relationships, and facilitate the vibrancy of urban systems (Chen & Huang, 2024). Addressing the economic and social needs of the community requires a symbiotic approach, where elements interact harmoniously to create a cohesive and responsive urban fabric. Pedestrian-friendly streets have long been a contender for strengthening this synergy. Contextual factors of structure and space influence the built

environment, suggesting that there must be a scale at which planning and architecture coalesce.

Spatial heterogeneity refers to the variation in the uneven distribution of economic, social, and environmental impacts experienced by different communities as a result of the presence of a sports stadium. It highlights how effects such as changes in property values, economic benefits, or social dynamics are not uniform across all neighborhoods but instead vary significantly based on factors like proximity to the stadium, local infrastructure, and community characteristics (Ahlfeldt & Maennig, 2010).

The socioeconomics of stadiums in urban planning are often questioned. According to a Stanford economist, sports stadiums do not generate local employment or per capita income growth (Noll, 2015). The skepticism surrounding the socioeconomics of stadiums highlights the relationship between urban planning and community well-being, which is enforced through the built environment. The lack of evidence supporting positive economic outcomes raises concerns about their actual impact. In many cases, professional stadiums disproportionately benefit investors, and large corporations, increasing the values of the sport franchise (Zimbalist, 2023). John Mozena, president of the Center for Economic Accountability, wrote, “a dollar spent by a fan at a subsidized stadium is a dollar they are not spending at some other business in the community,” indicating that local businesses are hindered by stadium

development. With more inclusive dialogue among stakeholders, urban planners can better align stadium projects with broader socioeconomic goals, ensuring that they contribute to a more equitable and vibrant urban environment.

A survey conducted in 2022 by the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University found that 60% of respondents viewed professional sports teams as necessary cultural components of communities, highlighting the ongoing demand for stadiums, despite the negative economic impacts they may bring. A stadium’s atmosphere on game day promotes excitement and experience that shapes peoples’ perception and understanding of their own city; event-free days pose challenges. Traditional sports and entertainment venues are fading as teams and entertainment entities strive to move toward more diversified entertainment districts. To be successful, future developments must be dynamic centers of interconnectedness, which adapt to seasons and even time of day to reach optimal year-round use.

This thesis, however, does not focus primarily on changes in property values or economic benefits alone. Instead, it emphasizes the movement of people and the various forms of mobility integrated into cities and neighborhoods, which contribute to the vibrancy of stadium districts. The flow of individuals within these areas can enhance accessibility, promote social interaction, and stimulate local economies in ways that extend beyond traditional economic measures. The goal

of this thesis is to develop a strategic mobility network for stadium districts, leveraging the movement of people to strengthen urban connectivity and vibrancy.

Stadium development primarily occurs in its city’s center, which is why teams are pushing for moves closer to downtown. Architecture firms, such as Rossetti, Populous, Sasaki, and HOK, are at the forefront of designing the influx of new stadiums, emphasizing the integration of these venues into the urban landscape. The relevance extends not only on a global scale but is particularly significant for Detroiters. A new stadium is currently under development in the Corktown neighborhood, set to be the future home of Detroit City Football Club (DCFC), Detroit’s current and only professional soccer team. In line with the growing trend of sports teams relocating nearer to their downtowns, Detroit City FC is also following suit, moving closer to their city center.

The Detroit City Football Club (DCFC), colloquially known as “Le Rouge,” is a professional soccer team based in Detroit, Michigan. Established in 2012, Detroit City FC has steadily risen in prominence within American soccer, having joined the United Soccer League Championship (USL) back in 2022. The league, which serves as the second tier of the United States soccer league system, just below Major League Soccer (MLS), features a membership of 24 clubs from across the continental United States. Upon Detroit City FC’s entry into the USL Championship, former USL president Jake Edwards stated, “It’s hard to find a better example of bringing a community together [than] through soccer. We welcome the DCFC community and its famed supporters into the USL family, and we look forward to seeing this next phase of the club’s evolution.” Edwards’s praise reflects the unique connection DCFC has cultivated with its passionate fanbase and the Detroit community. The

organization has earned widespread applause for its commitment to building a vibrant soccer culture and enhancing community engagement. This reputation underscores DCFC’s standing as more than just a team—it is a symbol of pride and unity within Detroit’s rich culture.

Le Rouge pays homage to the region’s rich French heritage, reflecting Detroit’s founding in 1701 and its historical connection to the French language. The club colors, rouge, symbolize strength, passion, and resilience, while the gold represents the value placed on unity, excellence, and pride. The team’s crest also incorporates The Spirit of Detroit statue. Erected in 1958, the statue depicts a figure holding a glowing orb and a family, symbolizing the city’s strength, unity, and commitment to both individual empowerment and community solidarity.

Keyworth Stadium, a 7,933-seat multi-purpose facility in Hamtramck, Michigan, has been home to Detroit City FC since the 2016 season. Owned by Hamtramck Public Schools, the stadium underwent significant renovations after the Detroit City Football Club launched a crowd-based investment campaign. Notably, the campaign, whose slogan was “save history, make history,” spanned 109 days and ultimately raised $741,250 from nearly 500 verified Michigan investors. The improvements included structural grandstand repairs, bleacher refurbishments, and upgrades to locker rooms, restrooms, and lighting. Subsequently, after several volunteer opportunities during which supporters helped to paint bleachers and clean up the stadium, the team hosted its inaugural match on May 20, 2016. The home opener against AFC Ann Arbor, which drew 7,410 supporters, marked a new era for the club and its dedicated fanbase.

Hamtramck, located within the Detroit metropolitan area, is known for its diverse community and large immigrant population, embracing the slogan, “The World in Two Square Miles.” Early in its history, Hamtramck was home to German immigrants. Then, in the early 1900s, Polish immigrants moved into the area, imprinting it with their heritage for most of the 20th century. To this day, Hamtramck remains synonymous with Polish culture, although the population has significantly decreased. Today, the city—recognized as the most diverse and dense in Michigan—is made up predominantly of Bangladeshi, Yemeni, and Southeastern European immigrants, all drawn to its small, close-knit nature, low taxes, and multi-family unit homes.

Keyworth Stadium in Hamtramck wasn’t always home to Le Rouge. On May 12, 2012, Detroit City Football Club played its first National Premier Soccer League (NPSL) match at Cass Tech High School in Detroit, a stadium with a capacity of 3,000. Sean Mann, co-owner of the team, says that the second half of the 2014 season saw an average attendance of nearly 2,900. An article posted by the Detroit Free Press states, “The club originally played at Cass Tech, paying $125 a game to use the field, before moving to Keyworth Stadium.” Now, the club, which has grown to include a women’s team and youth teams across metro Detroit, will finally have a home of its own. With their rapid, exponential fanbase growth, the need to expand beyond Cass Tech became clear, and this phenomenon is happening once again. Keyworth Stadium, opened by former President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936, will no longer be DCFC’s home as the club continues its remarkable growth.

As alluded to, DCFC is set to move to a new home, with the goal of opening a soccer-specific stadium by the club’s 2027 season. The news released on May 16th, 2024 that the USL championship club acquired the site of the former Southwest Detroit Hospital at the corner of Michigan Ave. and 20th Street, near I-96 and I-75, a few blocks away from Ford’s newly restored Michigan Central Station (Figure 1.5). “The Southwest Detroit Hospital opened back in 1973 as the first Detroit hospital to hire and accredit African American doctors and nurses, which was uncommon in the United States then. The building has been abandoned for over 18 years. The original hospital existed only 17 years; in 1991, it closed and declared bankruptcy,” per detcityfc.com.

However, the club’s ambitions did not end there, co-owners Sean Mann and Alex Wright are also sitting on a total of 15.25 acres in Corktown with close

proximity to the former hospital (Figure 1.6). For instance, Detroit City purchased the vacant 45,000-square-foot former Cornbelt Beef Corp. warehouse for $2.55 million (Figure 1.7), with the intent of adaptively reusing the building and activating the road directly adjacent to the stadium.

Activating 20th Street offers a wide range of possibilities, from integrating dynamic performance or play-based designs to establishing a vibrant space for events leading up to and following gameday, complete with a lively array of bars and restaurants. This transformation could create a dynamic atmosphere where fans and visitors fully immerse themselves in the excitement of the gameday experience. Corktown, directly bordering downtown Detroit, benefits from its prime location, placing the future stadium site just a 2 mile drive from the city center (Figure 1.9). With the City of Detroit, Ford, and DCFC as

key entities driving its growth, Corktown is more vibrant than ever. The new stadium development will serve as the permanent home for soccer in Detroit.

As previously mentioned, Corktown is the city’s oldest existing neighborhood. To escape the Great Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s Irish immigrants began moving to the westside of downtown Detroit, now known as Corktown, which is said to be named after Cork, Ireland. In fact, according to the Detroit Historical Society, "by the early 1850s, half of the residents of the 8th Ward (which contained Corktown) were of Irish descent." After World War II, "city planners proposed demolishing large swaths of the neighborhood for factories," eventually resulting in 75 acres of Corktown homes and businesses demolished, as well as

hundreds of residents displaced, according to the Detroit Historical Society. Additionally, "urban renewal, construction of the Lodge Freeway, and business district encroachment" led to the neighborhood's suffering. In July of 1978, the remaining residential section of Corktown became part of the National Register of Historic Places, but it was not until the early 2000s that the neighborhood had its comeback. While Corktown cherishes its Irish heritage, it has evolved into a melting pot of cultures over the years. The neighborhood's diversity is reflected in its residents, who hail from various ethnic backgrounds, contributing to a rich tapestry of traditions, languages, and customs. This diversity adds to the neighborhood's allure, fostering a sense of inclusivity and creating an environment where different perspectives are celebrated. Along with key landmarks such as Michigan Central Station, Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church, and the Detroit Police Athletic

League’s (PAL) Corner Ballpark, formerly Tiger’s Stadium, a notable feature of the neighborhood is the main corridor of Michigan Avenue. This thoroughfare retains its historic character, with the brick cobblestone street that evokes a sense of the past, while blending with contemporary shops and dining

establishments (Figure 1.8). With news of the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) planning to remove the bricks on Michigan Avenue, two Corktown residents exclaimed, "We love the bricks, they add history to our neighborhood," a sentiment echoed by many other Corktown residents.

Stadium moves further from city center

Stadium moves closer to city center

1.10 - United Soccer League (USL) Championship stadium re-locations in the last fifteen years.

The following chapters and explorations utilize a post-positivist framework, which assumes reality is objective, separate, and probabilistically knowable as the primary lens. This is complemented by a contextual framework, which situates reality within its context as a secondary perspective. This thesis will be grounded in measurable, data-driven analysis while acknowledging that absolute certainty is unattainable. It will also ensure that the analysis remains responsive to human experience, cultural influences, and localized urban conditions, allowing for a more nuanced understanding beyond purely quantitative measures.

Rooted in the understanding that stadiums are not standalone objects but catalysts for urban interaction, this thesis redefines the traditional journey to the stadium as an essential component of the city’s spatial and social fabric, with streets acting as the threads that guide this journey. The approach advocates for a network of roads through pedestrian-friendly streets and multi-modal pathways that foster a vibrant, connected district. A network is a system of streets that promotes various aspects of mobility and transportation, offering direct, parallel, and alternative routes to accommodate different environmental conditions, all represented by the open space between buildings. This, in turn, creates urban vibrancy—the dynamic activity within a city. (Chen & Huang, 2024).

Henceforth, this thesis is predicated on the revolutionary Woonerf (pronounced VOO-nurff) design, developed by Dutch traffic specialist Hans Monderman. Woonerf is a Dutch term for "living street" and refers to a new way of designing streets to be people-friendly open spaces. These shared spaces are created through community; community is a group connected by shared social interactions and spatial relationships within a defined area (Wilkins, 2016). Essentially, this approach addresses the challenges of urban environments, creating spaces where pedestrians and vehicles can coexist in an optimal balance.

Vibrancy is the dynamic social and cultural activity within a city, characterized by the liveliness of its public spaces, diversity of land use, frequency of human interactions, and balanced allotments for greenspace (Chen & Huang, 2024) (Grant, 2007). The two writings, Achieving Urban Vibrancy Through Effective City Planning: A Spatial and Temporal Perspective by Zheyan Chen and Bo Huang along with Mixed-Use in Theory and Practice: Canadian Experience with Implementing a Planning Principle by Jill Grant were paramount in the discovery of the term 'urban vibrancy'. In an urban context discovery of the term 'urban vibrancy'. In the urban context is where vibrancy

thrives. Urban vibrancy is not incidental, but rather the result of deliberate spatial configurations and policy decisions. It emerges through the layering of uses, the calibration of public space, and the continuity of pedestrian-scale interactions. Understanding urban vibrancy in this way positions it as both a measurable outcome and a design objective, one that requires attention to context, timing, and the nuances of human experience (Fite, 2021).

Paths naturally intersect, forming nodes that function as essential stopping points and interaction points for pedestrians along their journey. The design of pathways extends beyond a single well-designed street. As Lynch states, “Nodes are the conceptual anchor points in our cities” (Lynch, 1960). He further explains, “If a break in transportation or a decision point on a path can be made to coincide with the node, the node will receive even more attention. The joint between path and node must be visible and expressive, as it is in the case of intersecting paths” (Lynch, 1960). With the convergence of these paths resulting in nodes that define open urban spaces, the design of these intersections becomes crucial in shaping the relationship between the built environment and positive space.

In Redefining the Role of Civic Nodes in the Urban Fabric, Desai explains, “Nodes have the capacity to be a point of concentrated activities and can be used as reference points” (Desai, 2020). These spaces serve as vital hubs where communities gather, experiences are shared, and energy is vibrant. “Highly vibrant places often foster a higher quality of life through social interaction and active participation, contributing to overall well-being and shaping the character of places” (Grant, 2002). To reiterate, urban vibrancy is the dynamic social and cultural activity within a city, characterized by the liveliness of its public spaces, diversity of land use, frequency of human interactions, and balanced allotments for greenspace. “In practice, several planning principles, such as mixed land use, high-density neighborhoods, and small blocks, have been proposed to promote urban

vibrancy, as vibrant urban spaces are believed to contribute to public health and safety outcomes” (Braun & Malizia, 2015) (Woodworth & Wallace, 2017).

Since nodes occur at junctions where activity points are concentrated, they create a more vibrant space, which, according to scholars, contributes to safety outcomes. By integrating nodes around the stadium district, the urban environment can improve street activity and encourage safety, ultimately benefiting a diverse range of users. Eran Ben-Joseph in his paper, Changing the Residential Street Scene: Adapting the Shared Street Concept to the Suburban Environment, states “Shared streets are more than transportation channels; they are places suited for pedestrian interaction, as people choose to pause and socialize on the street” (BenJoseph, 1995). Enforcing the notion that streets and nodes should be designed as active social spaces rather than channels for movement. Bilal Caliskan’s

findings in Factors Making a Street a Vibrant Place compares active street locations—Main Street, Fort Worth, Texas, USA and Inonu Boulevard, Sivas, Turkey—which were selected as case study areas. He starts by stating “street design is a necessary but not sufficient factor affecting pedestrian activities, and that local activities and destinations for meeting daily needs play a stronger role in generating a desirable street life. However, in the American case, design factors do play a stronger role than in the Turkish case, while in the Turkish case, the diversity of local activities and destinations serving the daily needs of individuals and the community, is more meaningful” (Caliskan, 2017). Urban streets have a significant function for keeping a city livable and vibrant. They are one of the most vital parts of cities not only because they serve urban transportation, but also because they are critical elements of the public realm that people use to go to meet daily needs and interact with others.

Stadiums serve as landmarks within a city. However, unlike other landmarks, this typology is often designed in isolation. In The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch lists characteristics associated with landmarks. Some include distinctive shapes, unique functions, proximity, contextual relationships, visual exposure, and symbolic significance (Lynch, 1960). While these characteristics are considered in stadium design, designers often prioritize form and function and neglect contextual relationships. These elements contribute to how landmarks are perceived and how they interact with their surrounding environment. A stadium, as a prominent urban feature, becomes a defining element of the cityscape. The term spatial prominence, as used by Lynch, refers to a landmark's ability to stand out and compellingly capture attention through its size, shape, or location (Lynch, 1960).

Architects and designers are often more concerned with aesthetics than with the spatial integration of these stadiums. The Stadium and the City by John Bale also highlights the divide between stadia and street while exposing the stadium as a major element of the modern urban scene.

Clare Cooper Marcus, an architect and pioneer in open space design, in her work People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space, outlines design guidelines specific to various types of urban open spaces. The seven types she discusses include

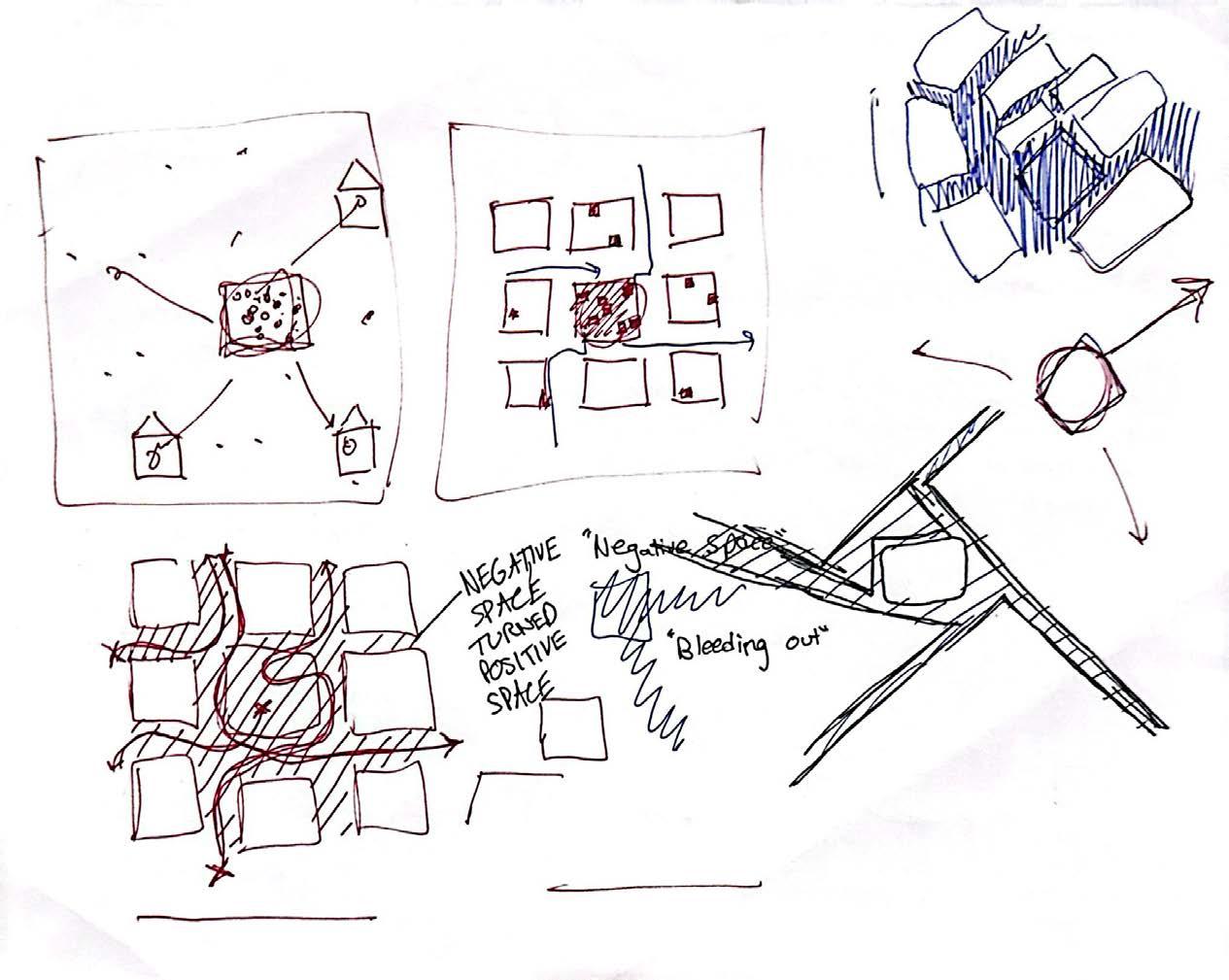

urban plazas, neighborhood parks, miniparks, vest-pocket parks, campus outdoor spaces, outdoor spaces for the elderly, and child-care outdoor spaces. However, notably absent from this list is the consideration of streets as a distinct type of urban open space. Inherently, when a landmark occupies space within a city, it generates negative space around it, which subsequently transforms into pathways, or urban open space. While this phenomenon is somewhat inevitable, urban planners have the ability to control the type of pathways that emerge. More often than not, these pathways are designed primarily as roadways for vehicular travel, rather than accommodating pedestrians, cyclists, or even playful children after school.

Negative space, in the context of urban design, refers to the residual, often overlooked areas within a city that exist between built structures and active spaces, providing opportunities for connection and the integration of diverse functions within the urban grid. “Through a negative space connective tissue, [stadiums] in urban centers could ‘spread the load’ and ‘share the gain’ simultaneously” (Guaralda & Kowalik, 2011). The term “negative space” is somewhat misleading; it should instead be regarded as “positive space,” representing the connection and comprehensiveness streets start to create when designed as a network. As Lynch notes, “the lines of heavy flow become the key paths, regardless of other visual characteristics” (Lynch, 1960). According to Lynch, streets, as paths, essentially represent negative space through which people traverse the city. These negative spaces often

lack openness, have limited connectivity with surrounding structures, and generally exhibit low architectural vitality, leading to numerous negative impacts on individuals and the urban environment (Meng, Zhu, Wen, 2020; Thilakaratne, 2019). The goal of this thesis investigation is to use the Detroit City Football Club’s future home ground as a testament to what can be achieved when stadiums are designed as part of a connected network of positive spaces, rather than existing in isolation.

Architecture firm HOK’s, sports, recreation, and entertainment sector released an article regarding the creation of vibrant cities through sports-anchored districts. “Decades ago, arenas were often enclosed black boxes that engaged with audiences only within the building. When the event ended, fans headed straight to their cars and home. This practice conflicts with creating a great neighborhood and leveraging a venue for catalytic development. Arenas should be a beacon connecting a community, encouraging foot traffic and activity throughout the district, and supporting fluidity to nearby neighborhoods. Sports-anchored districts should also establish multi-modal connections in the neighborhood, including walking, driving and public transit. These connections should provide easy, comfortable access for all those living in, working in, or visiting the area. Strategically placed transit stations enhance connections, while parking garages on less active edges of the

district encourage quick movement into the district without disrupting areas for development. This adds to the vitality of a city.” HOK’s philosophy aligns with the idea that a well-designed stadium district should generate a spillover effect that extends beyond game-day activity. Their emphasis on connectivity and multi-modal access reinforces the idea that the district’s design plays a critical role in shaping its influence on the surrounding city.

Two colleagues, one from MIT and the other from Northwestern University, conducted a study titled, Do Local Businesses Benefit from Sports Facilities? The Case of Major League Sports Stadiums and Arenas. Their research examines the spillover effects of major league sports facilities on nearby businesses, revealing that while baseball and football stadiums generate significant economic activity for food, accommodation, and retail establishments, basketball and hockey arenas exhibit no statistically significant net spillovers. As the authors conclude, “The results indicated positive spillovers from baseball and football stadiums that are concentrated largely in entertainment-related businesses in the closest proximity to the facilities. On the other hand, [they] find that the spillover estimates for basketball & hockey arenas are not statistically significant. While the positive spillover effects of basketball and hockey arenas can be detected in the inner-most area around the facility, they come at the cost of reduced visits to businesses located further away, so the net effect is ambiguous.” (Abbiasov & Sedov, 2023). The concept of spillover effects can inform my thesis investigation. Some

may argue that the economic benefits of stadiums are limited or even negligible for certain sports. The counterargument suggests that a lively stadium district does not inherently generate economic value for its host city. However, these findings are based on existing stadium models rather than a network of pedestrian-centered streets designed to function cohesively and offer diverse mobility options. Furthermore, the intent of a mobility network within a stadium district is not solely to serve game-day crowds but to create an environment where neighborhood users can navigate freely with multi-modal travel options.

Sports are a unifier for any city, and a civic spirit is uplifter. A case study performed by Olivia Viorst, in her thesis, Impact of a Sports Stadium on a Neighborhood, this was not the case. The development of Navy Yard in Washington D.C. has experienced changes to the community’s cohesion and identity. The dramatic demographic and economic shifts in Navy Yard contributed to major changes in community identity (Eckstein & Delaney, 2002). The dichotomous experiences of residents and their conflicting interpretations of the community self-esteem are reflected in the older resident’s attitudes towards utilizing the space in the neighborhoods. The Washington Post wrote, “she (Rhonda Hamilton, community organizer) and other community advocates have banded together to push developers into considering the entire community

—not just the affluent renters and tourists who visit the Wharf or the ballpark — when making decisions about the use of space and commercial tenants” (Lang, 2021). Moreover, urban planners must navigate the diverse needs of various user groups, ensuring that affluent newcomers and visitors are considered without overlooking the needs of existing residents. While stadiums inherently generate energy, excitement, and engagement, the challenge lies in extending these qualities beyond the stadium itself. A design approach that blurs neighborhood boundaries through the use of a street network and reinforces a strong sense of place can create deeper community connections and a more inclusive, vibrant district.

As a result of stadium design, spatial chaos often ensues at the urban scale. The overflow of large impervious surfaces around the stadium, combined with streets primarily designed for vehicular travel, contributes to this imbalance. Consequently, the spatial efficiency of these streets is frequently compromised and overlooked. In his research paper Woonerfs and Other Experiments in The Netherlands, J.H. Kraay discusses the Dutch concept of Woonerfs, meaning "living street" or "shared space." This design concept creates a safer, more interactive, and pedestrian-friendly urban environment. The shared street layout establishes a pedestrian orientation by giving pedestrians primary rights, making drivers feel like intruders. This

integration of pedestrian activity and vehicular movement on one shared surface promotes a more balanced and dynamic public space. Under this approach, the street is primarily designed to serve as a residence, a playground, and a meeting area, with the additional functions of carrying access traffic and providing parking spaces. However, it is not designed for intentional through traffic (Ben-Joseph, 1995). Typically, the various types of activity within spaces are categorized based on user types—such as residents, commuters, or tourists—and user behaviors, including activities like communication, watching, walking, sitting, and standing (Cooper, 1976). After analyzing these sources, user experience within streets themselves becomes increasingly plausible. Building on the Dutch ideology, shared streets will be strategically incorporated into the mobility network in proximity to the stadium, facilitating a broader range of activities and interactions.

Additionally, the negative effects of car traffic on urban environments have been widely discussed. Buchanan's 1963 book Traffic in Towns: A Study of the Long-Term Problems of Traffic in Urban Areas summarizes how car traffic has annexed streets once used by children for play and is encroaching on recreational spaces in modernist developments (Moughtin & Shirley, 2005; Rychlewski, 2013). Urban design and street network layout influence transportation and spatial usage (Forsey, 2013). The dominance of car traffic in urban environments not only disrupts social and recreational spaces but also diminishes the overall walkability and accessibility of city streets. A welldesigned urban street network can mitigate these issues by prioritizing multi-modal transportation and fostering environments that support pedestrian and cyclist activity.

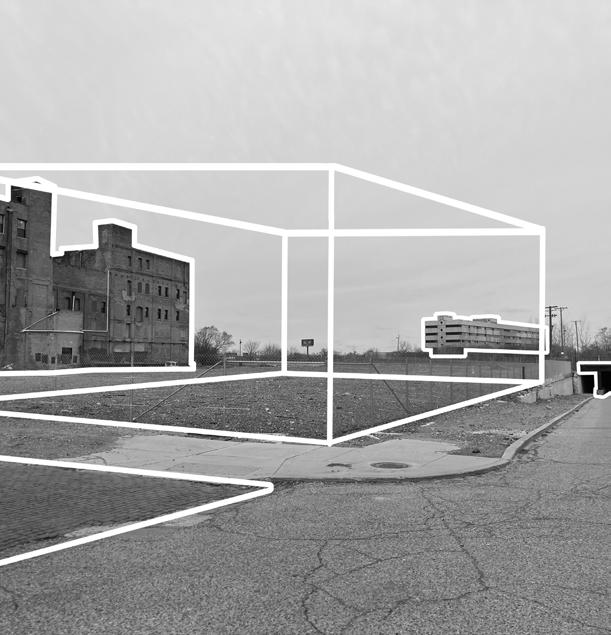

Being in close proximity to the future Corktown stadium district, it becomes relevant to examine District Detroit, a more established sports-anchored district in the city. The case study begins with on-site observations, walking the area and analyzing the experiential qualities of the space. These observations include the number of people on the street, the intentional turns pedestrians make, the routes often avoided, and other spatial behaviors. District Detroit serves as a critical reference in understanding how another stadium district, just two and a half miles away, could begin to take shape. Following the on-theground analysis, an aerial investigation is conducted to better understand spatial relationships, such as the width of streets between buildings and the distance from one public space to another, or in some cases, the absence of these connections. District Detroit is not a perfected district. Among Detroit residents, there is often a negative

perception and connotation of the plan due to its many unfulfilled promises. When examining the timeline proposed by the Ilitch family for new buildings and streetscape improvements, repeated inconsistencies emerge. These gaps become even more apparent when mapping the area, which reveals numerous empty parcels where largescale developments were initially promised but never delivered. Despite these shortcomings, the physical proximity of the stadiums suggests that the district holds potential to become something more integrated and vibrant—comparable to a place like Wrigleyville in Chicago, where the stadium exists seamlessly with its surrounding streets and neighborhood scale. The findings from District Detroit present both opportunities and challenges, which become especially evident through the initial methods of on-site observation and spatial analysis. Photographing and diagramming the district further clarifies positive and

negative spatial traits. Observing vehicle speeds in person, for example, provides insight into where traffic calming measures could be implemented in the Corktown site. Monotonous and uninspired crosswalks are highlighted in the photographs, suggesting a need for more engaging and safer pedestrian environments. Most notably, the lack of people throughout the district is difficult to ignore. In one image, taken just two hours before a Detroit Pistons home game, only a few pedestrians are seen near Little Caesars Arena, with little to no fan activity in nearby bars and restaurants. The intention is not to replicate District Detroit. Instead, this case study serves to outline how public life and spatial engagement can be scaled more appropriately. The investigation emphasizes the importance of user experience, placing district vibrancy and connectivity at the forefront of future design considerations. It is also important to acknowledge the distinct differences in

scale between the arenas, which informs how design responses should be tailored. In conclusion, the findings from District Detroit provide a framework for evaluating how a stadium can shape and be shaped by its surrounding streets. While the specific context of Corktown presents unique conditions, the insights from this case study offer applicable lessons for similar urban scenarios. Further research should examine how sports-anchored districts shape patterns of use, movement, and everyday life in their surrounding neighborhoods.

The 243-acre entertainment district, centered around Little Caesars Arena, Comerica Park, and Ford Field, has a key thoroughfare in Woodward Ave. Streets like Columbia Street and Sproat Street encourage pedestrian activity with retain, dining, and entertainment. However, the district lacks urban vibrancy Clifford Street and Montcalm Street mostly serve parking and service functions. Despite its potential, Detroiters argue developers have yet to fulfill their promises, citing a lack of affordable housing, insufficient infrastructure, and low multi-modal connectivity.

The 243-ac Park, and F and Sproat district lac service fun their promi multimodal

BOUNDARY STADIUMS

STREETS

PERSPECTIVES

BOUNDAR

STADIUMS STREETS

PERSPECTIVES

The 243-acre entert ainme Park, and Ford Field, has and Sproat St. encourage district lacks urban vib service functions. Despi their promises, citing a multimodal connectivity

Between Little Caesars Arena and the residents of Brush Park, the dense street section leaves no room for a dedicated bike lane. Additionally, the streetscape lacks vibrancy. However, the QLine offers a mass transit option for Detroiters to use at the cost of no expense.

MONOTOUS CROSSWALK

UNINVITING

On a Detroit Pistons game day just two hours before tip-off, the crowd is underwhelming. The few pedestrians who are present are using Park Avenue, now a newly designed greenspace, as a corridor to pass through, rather than as a leisure area.

The 471-foot-long, 50-foot-wide pedestrian-only street is lined with restaurants and retail. Its herringbone brick pattern, framed by multi-story buildings, invites people in towards Comerica Park.

Streets for People Mission Statement:

"The City of Detroit now has a Streets for People Plan to make it easier and safer for all Detroiters to be mobile throughout the city. The transportation plan prioritizes improving safety for all Detroiters, especially our most vulnerable residents, and identifies clear implementation and design strategies for street improvements. Most importantly, the plan was created with the input of thousands Detroiters. This initiative includes the Streets For People Plan, Street Design Guidelines, and the Comprehensive Safety Action Plan."

The Streets for People plan, developed by the City of Detroit’s Department of Public Works, provides a foundation for this thesis investigation. By focusing on improved mobility and safety throughout the city, particularly for residents most at risk, the plan supports a more inclusive and thoughtful approach to urban street design. Its guidance on implementation and street improvement strategies contributes to a clearer understanding of how streets can function as spaces for interaction and movement rather than being limited to vehicular use. The plan, shaped through input from a wide range of community members, emphasizes the importance of local perspectives in shaping public space. The statistics reflect resident input, guiding design through lived experience. These elements influence the development of values within the investigation, encouraging a street network that supports pedestrian activity, balances different modes of travel, and promotes everyday use by a variety of users.

SFP is rooted in five values.

1. Safety First: Safe streets for all Detroiters - zero crashes, zero deaths

2. Equity, Dignity, and Transparency: Transparent planning and rigorous community engagement

3. Access for All: Easy mobility throughout the city, no matter age or ability

4. Economic Opportunity: Access to jobs, empowerment and neighborhood support

5. Public Health: Safe mobility options to improve health and reduce pollution

Number of Survey 1,037

19% of responses mentioned the need for safety improvements on their streets. Of these, there were 102 specific references to the safety of pedestrians and cyclists.

11% of responses mentioned wanting streets that are inviting, well designed and encourage people to be outside! For example, one respondent hopes for "less lanes and more room for walking, biking, outdoor dining, and congregating".

The number 1 survey response from 28% of all responses, was directed at addressing speeding on Detroit's Streets! "Live on local streets with long straight stretches that give drivers the opportunity to speed".

7% of responses mentioned the need for improved pedestrian facilities. These responses touched on the full range of pedestrian improvements including fixing cracks in sidewalks, adding crosswalk striping, and installing blinking flashing lights.

93%

7%

5% of responses want complete streets with "more space for walking, biking and open activity. More priority for public transit".

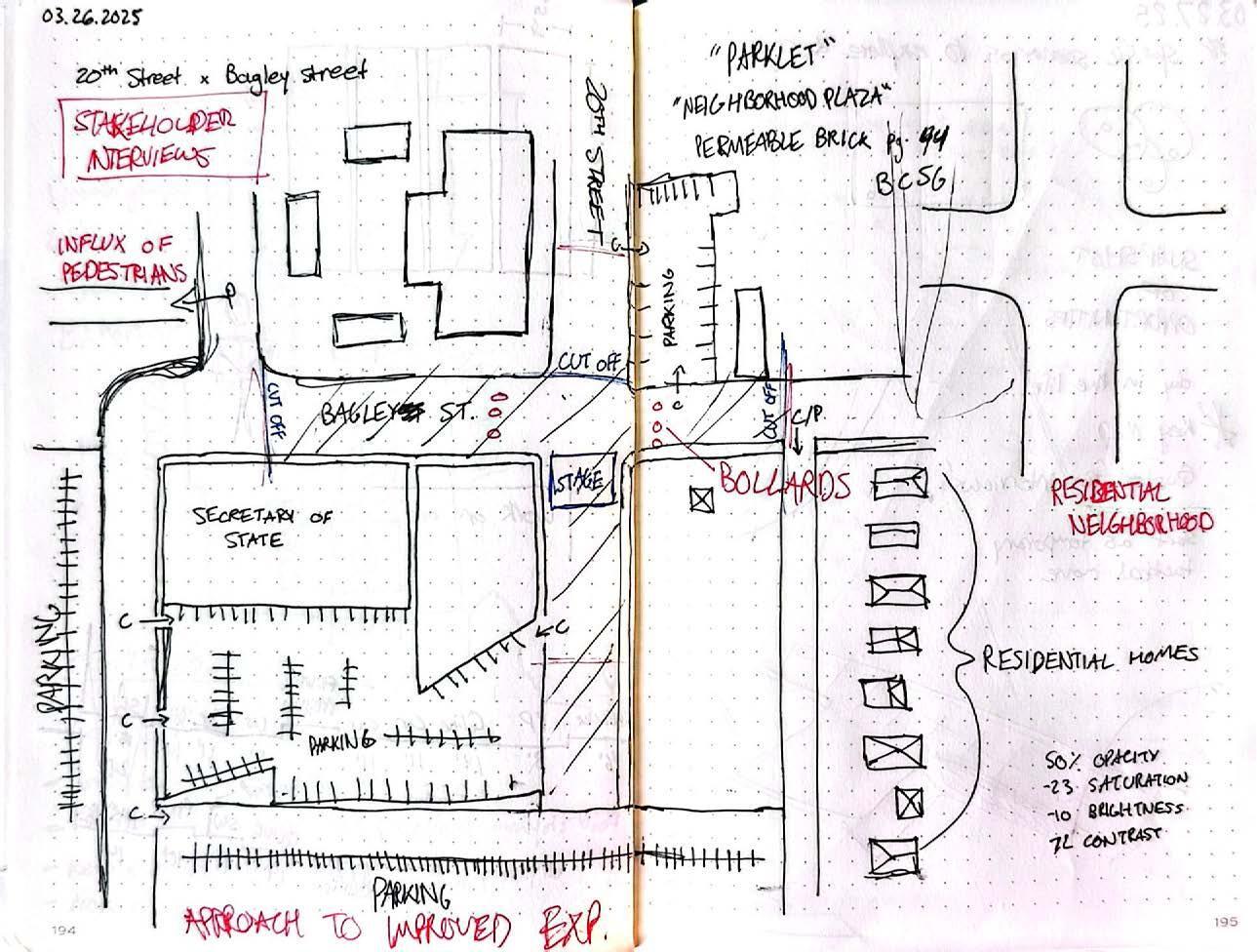

Corktown residents express a strong sense of pride in the neighborhood’s historic character. The culture and community it fosters are highly valued, especially given its close proximity to Downtown. A recurring topic of discussion is the brick pavers embedded in Michigan Avenue. While some view these as a point of contention, Corktown residents strongly support their preservation. During a site visit along Michigan Avenue, two young women in a white Jeep initiated a conversation and asked about the work being done. After explaining the project focused on documenting the journey to the former Southwest Detroit Hospital, the discussion shifted to the neighborhood. They voiced concern over how much of Corktown is changing without local input. When Michigan Avenue was mentioned, they immediately brought up the bricks, emphasizing their

importance to the community and frustration with MDOT’s plan to rebuild the two-mile stretch from Interstate 96 to Campus Martius. Their concern centered on whether the bricks would be preserved and why residents were not more involved in the process. Similar sentiments appear in conversations with other residents. The message is consistent: Save the Bricks. This phrase also serves as the name of a campaign led by locals who advocate for protecting Corktown’s heritage while calling for transparency and proper planning. The same brickwork appears near the proposed stadium district, particularly along Standish Street. More importantly, the community’s unity reflects a deep connection to place. Recognizing this culture and history is essential when designing a mobility network that reflects local values and earns public trust.

Much of the foundational work already exists. The Greater Corktown Framework Plan serves as a key contributor to understanding the identity, priorities, and concerns of the community. Launched in 2019 by the City of Detroit, the initiative engaged residents in shaping a vision for inclusive growth while preserving the distinct character and heritage of Detroit’s oldest established neighborhood. The planning effort adopted both a contextual and co-constructed lens, allowing participatory research to play a central role. Residents from North Corktown, Historic Corktown, as well as portions of Core City and Hubbard Richard were actively involved through interviews, public workshops, and stakeholder meetings. Among the plan’s key takeaways was an emphasis

on "improved street connectivity—for vehicles, pedestrians, and bicyclists— through enhanced roadway design and extended sidewalks". This directly informed the early design considerations for the site (Figure 3.2). Because the plan concluded in 2019, it left open the opportunity to expand its vision and apply it to areas not explicitly addressed—specifically, the site of the former Southwest Detroit Hospital. Notably absent from the original framework was a focus on entertainment and experiential engagement. Based on the voices of stakeholders and documented community input, the concept of experience emerged as a significant, yet previously overlooked, dimension of urban mobility. As walkability and connectivity serve as primary drivers of

this thesis, the intent became to enrich the pedestrian journey—not merely facilitate movement, but elevate the process of getting to a destination. The city’s community engagement efforts were critical in shaping this objective. With limitations on outreach scale, relying on large-scale city-led engagement served as a reliable proxy. The visuals included in the planning documents supported an architectural understanding of the spatial qualities desired by the community, such as the activation of vibrant and human-scaled streets (Figure 3.3). These insights resulted in a refined design proposal: a mobility network that reconciles the residential atmosphere of North Corktown with the commercial and historic identity of Historic Corktown, while also supporting the integration of the emerging stadium district as a connected and active piece of the urban fabric. Special attention was given to

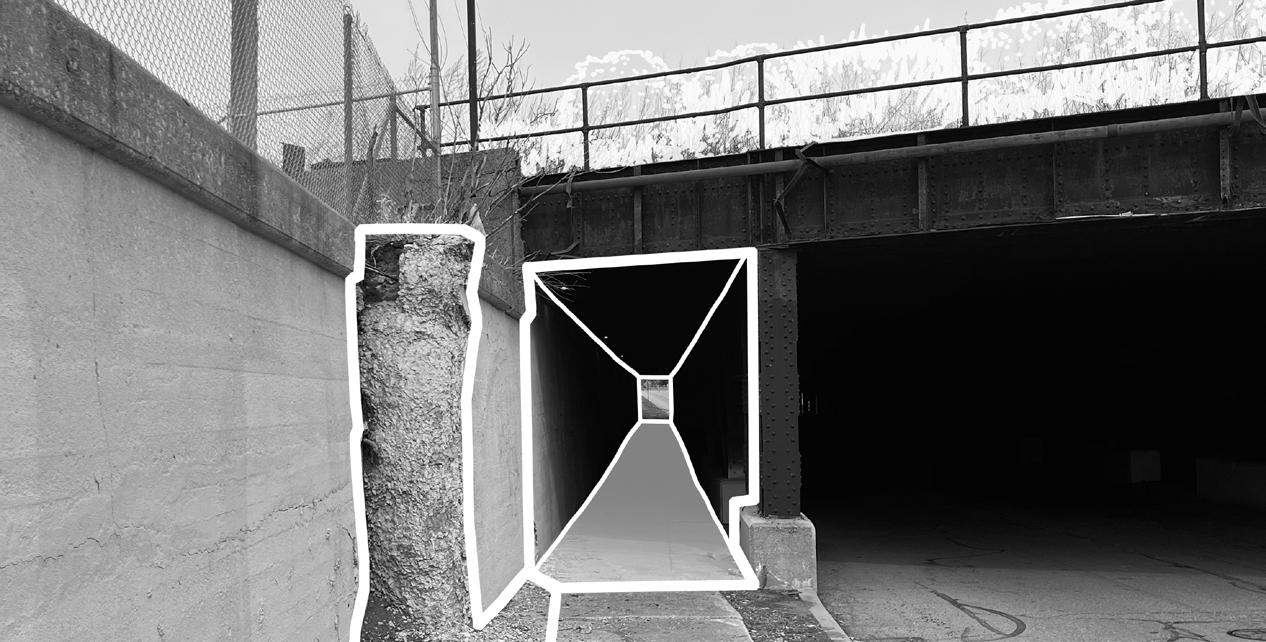

14th Street and its overpass, which is used daily by residents and commuters alike, as a point of physical and symbolic reconnection. The construction of I-75, which once fractured the fabric of Corktown, continues to define neighborhood identity on either side of the freeway. This condition required a deliberate approach to mend disjointed areas and rethink circulation through a community-focused lens. The proposed network centers the walk to the stadium as a way to connect neighborhoods, shaped by how people actually move through and experience the area.

Kevin Schronce serves as the Design Director for the City of Detroit, where he brings a deep focus on urban areas that have experienced disinvestment and inequitable planning, particularly in legacy cities. He engages daily with stakeholders and community members to ensure development efforts remain inclusive and community-driven. Schronce also acts as a primary point of contact for the City’s work in the Corktown neighborhoods, including the redevelopment and planning of the Michigan Central Station Innovation District.

As part of this role, he leads efforts within the Greater Corktown Planning Framework, an initiative launched by the City of Detroit in partnership with the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation. The framework aims to guide the inclusive growth of Detroit’s oldest established neighborhood, while preserving its cultural heritage, unique character, and community integrity.

- “Most pressing, comment, concern, piece of input that came up was mainly around antidisplacement and the housing affordability.”

- “A framework is meant to be flexible. Providing an array of amenities to try to continue to stabilize residential population, which an entertainment district or soccer stadium would do.”

- “Preservation of community character and urban character is important. However there is a little concern from folks losing the character from new people and new uses. Respecting the past, but also forging a new future.”

Alex Wright serves as the external advisor for this thesis. Known more broadly as a founding owner of Detroit City Football Club, Wright is a Detroit native and the club’s Chief Creative Officer. His responsibilities include overseeing broadcast and marketing operations, design, and story development, along with serving as the club’s main contact for public relations and media.

Together with Sean Mann, Wright leads the development efforts for Detroit City FC’s new stadium in Corktown. As a University of Michigan alumnus, Wright helped found the club in 2011 alongside four partners. His insights into the vision for the stadium and expectations for Corktown’s growth provide a direct link between the design ambitions of the club and the evolving character of the neighborhood.

- “The DPW Yard adjacent to us, will most likely get decommissioned and turned into a neighborhood which would be a great connection between Michigan Central and our stadium.”

- “We want as many people as possible to access this place by bike or on foot; the closer the greenway path is to the stadium area, the better.”

- “The close proximity to downtown could be an opportunity for mass transit.”

As Head of Place at Michigan Central, Melissa Dittmer directs all visionary aspects involved in shaping the 30-acre tech and culture hub. Her responsibilities include strategy, planning, architecture, design, construction, development, placemaking, and programming. With a background in architecture and a focus on long-term impact, her work reflects a commitment to building places and environments that endure across generations.

Dittmer identifies a clear connection between the Michigan Central Ford Campus Innovation District and the Detroit City Football Club Stadium District. Both areas hold the potential to serve as anchors for surrounding neighborhoods while preserving local character. She notes the emotional response people have when engaging with Michigan Central, recognizing how design and development can resonate deeply within a community.

- “Corktown is experiencing a moment of regenerative urbanism, driven by Michigan Central and Ford’s innovation-focused initiatives that encourage thinking outside the box.”

- “Parking is a frequent topic of discussion, and we are working to establish shared parking hubs designed to support revenue generation.”

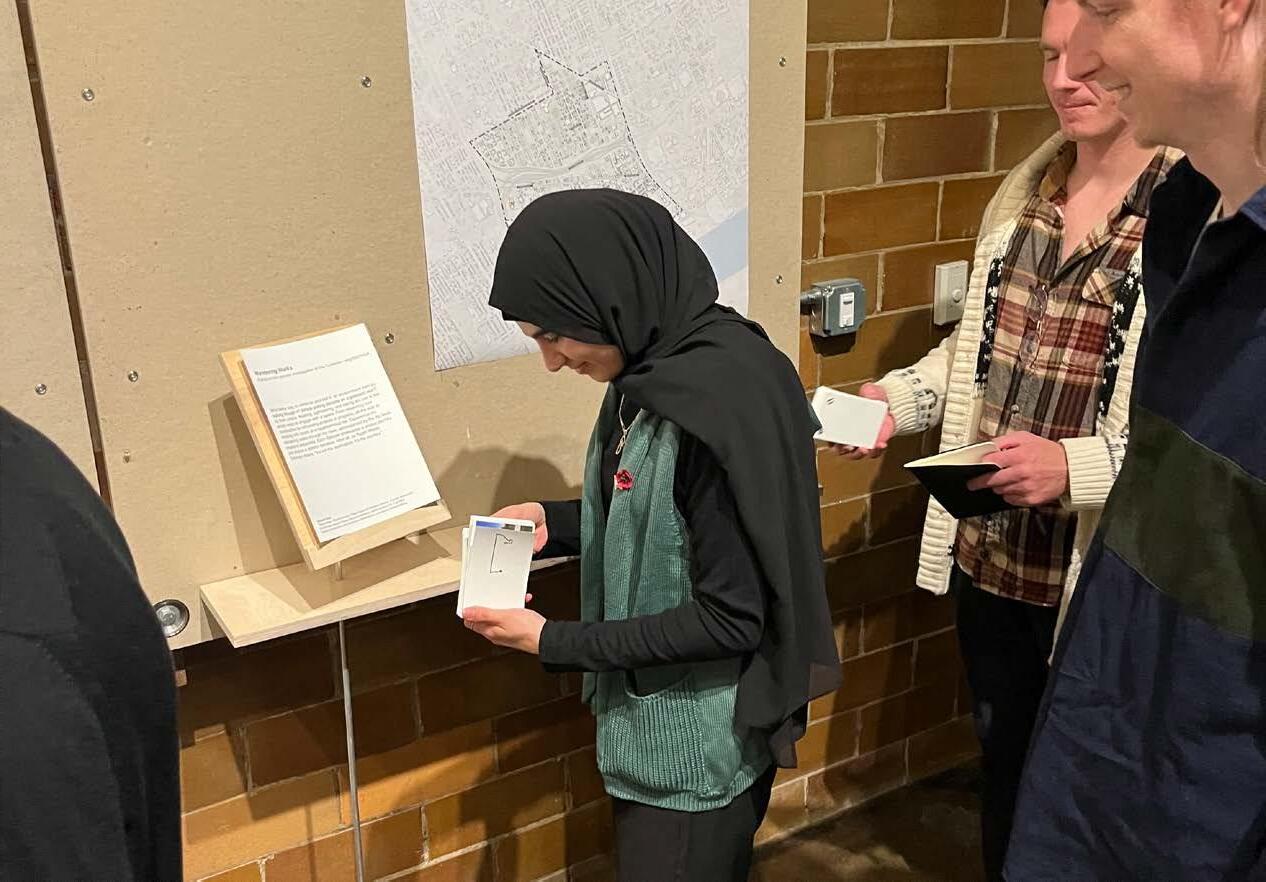

Conducting on site observations plays a major role in this thesis investigation. It enables a direct understanding of the streets and supports a perceptual reading of the neighborhood. Through repeated site visits, ranging from walks in below freezing temperatures to summer strolls in 70° weather, the neighborhood begins to reveal itself in layers. One of the early exercises titled Sketch Problem I prompts students to engage in research through making. This took the form of a boots-on-theground investigation of the Corktown neighborhood. Walking remains one of the most immediate ways to study a place. Images alone cannot capture the full experience. Walking, observing, and dining become means of interacting with and learning from the environment. These activities offer real time feedback on how space is used and perceived.

Each walk was documented in a flipbook. The flipbooks present distinct journeys, each with its own narrative, providing not only a visual record but also a deeper understanding of how individuals move through and connect with Corktown. These insights support the broader goals of the thesis by grounding the design proposal in lived experience. The results of this immersive research directly inform a mobility strategy that reflects the layered identity of the neighborhood. This work reinforces the value of walking as both a method of research and a tool of design. The process demonstrates that effective urban interventions emerge from repeated, engaged observation. As American writer and philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson notes, "it is not the destination that matters, but the journey".

Moving parallel to the weathered red brick of Michigan Avenue, he rounded the corner onto Trumbull, drawn by the mouthwatering aroma drifting from McShane’s Irish Pub. The sunny day beckoned a break, so he stopped for a hearty burger and a chilled beer before continuing on. Once finished, he returned to Michigan Avenue, his eyes following the brick and the steady flow of traffic threading through the corridor leading him toward the future venue.

The greenery lining Roosevelt Park’s paths led him toward Michigan Central Station. In the park, Children’s laughter rang out as couples strolled hand in hand. An elderly couple sat on a bench, their peaceful presence contrasting with the lively park. After passing through the park’s vibrant energy, the walk to the destination felt quick and uneventful, the activity fading into the background.

The hectic construction and imposing fencing of the riverfront set the tone for the walk, immersing him in anticipation. As the journey continued, obstructed sidewalk after obstructed sidewalk was encountered. The industrial vibe persisted, especially along the train tracks on Newark Street. Beneath the tunnel, darkness swallowed him, eerie and stretching nearly 400 feet until the distant arrival came into view.

Urban planner Roger Trancik’s principle, Linkage Theory, informs the conceptual circulation of recreational activities by emphasizing the reconnection of fragmented spaces. This approach supports the creation of a comprehensive network by addressing the empty and underutilized areas between buildings. By identifying breaks in spatial continuity, these gaps can be bridged through thoughtful integration of built elements or amenities, resulting in an interconnected open space that supports movement, interaction, and opportunity.

4.43 - Linking sequential movement for a student.

The final phase of the investigation focuses on implementing the findings into the spatial design of the stadium district’s streets. The process begins with the examination of current conditions through annotated photography of selected nodes and corridors within the Greater Corktown area. During the mapping of the district, key intersections emerge as critical nodes where movement concentrates and opportunities for activation are most pronounced. Stakeholders such as Detroit City Football Club, Ford Motor Company, and the City of Detroit frame the district and play a central role in shaping both the identity and functionality of the streets. The presence of the Joe Louis Greenway and the proposed May Creek Greenway, which intersect Newark and Bagley Streets, further establishes a foundation for a connected and layered mobility network. These infrastructural assets contribute to a broader system that ties the local street network into a citywide framework of movement and access.

The street network is organized through a hierarchy of corridors, where 20th Street becomes the primary spine for activity and circulation. This corridor is envisioned as the most dynamic and active component of the district, hosting the highest intensity of pedestrian and vehicular traffic. Streets like 14th, which intersect or run adjacent to 20th, function as secondary corridors that support and extend the programmatic potential of the network. These streets are designed to accommodate a range of uses and crowd conditions, offering flexibility and continuity between nodes. The nodes themselves serve as key opportunity points for public space

programming, temporary events, and community interaction. Visual material embedded in the book supports these ideas but is not a substitute for articulating the strategy in writing. The design proposal responds to the need for integrated and intentional planning by repositioning the streets as essential public infrastructure capable of supporting daily life as well as episodic events like match days.

This work positions stadium districts as active components of the urban fabric rather than isolated destinations defined solely by episodic events. Streets within these districts are proposed as positive space that contributes to the everyday life of the neighborhood while also supporting crowd dynamics on event days, as well as, non-event days. The findings emphasize the importance of a strategic mobility network defined by layered infrastructure, stakeholder coordination, and street-specific programming. While the investigation is grounded in the context of Corktown, the framework presented is applicable to other postindustrial urban areas where large civic institutions shape surrounding development. Future research should examine the governance structures necessary to maintain such networks and explore how temporal fluctuations in use patterns can inform street design. This thesis establishes a foundation for re-imagining the role of streets in stadium districts as integral to urban vibrancy, equity in access, and longterm resilience.

The following diagram has been referenced and alluded to in part throughout the thesis book. This is the integral design approach that has been created and used to inform design moves in regard to the Corktown stadium district. The plan creates a new paradigm for how the Corktown neighborhood can reinforce connections between stakeholders, programming, and guiding principles, with a multi-helix design approach to the cohesive network, where the community and larger society are more involved in, and benefit from, relevant street qualities and engaging activities. The outer cyan circles represent the guiding principles, stakeholder priority, and programming emphasis. The size of the inner white circles reflects the weight of framing concepts, user involvement, and street qualities. The guiding principles were derived from literature and foundational urban design theories to establish the framing concepts; stakeholder input was gathered through interviews with various user types along with the Corktown Framework Plan; and programming decisions were informed by precedent analysis to determine optimal street qualities. An additional layer of meaning is embedded within the diagram through the use of lighter gray dashed lines that weave between the inner white circles. These lines symbolize the interdependencies and interactions between the various elements, illustrating that no single component functions in isolation. Instead, each icon represents a concept that must operate in conjunction with others, reinforcing the necessity for an integrated and vibrant design approach.

Stadium District Stadium District

FRAMING CONCEPTS

URBAN PLANNING

Figure 5.1 - Multi-Helix design approach

INHOSPITABLE VISUAL BARRIER

NO LANDSCAPE MEDIAN

EXISTING SOUTH VIEW

POORLY DESIGNED PEDESTRIAN BRIDGE

CREATION OF NODE EXISTING EAST VIEW

CONFUSING LEFT HAND TURN

HOUSING OPPORTUNITY

NEW CONSTRUCTION NO LANDSCAPE ON ISLAND

EXISTING SOUTHEAST VIEW 3

MICHIGAN CENTRAL LANDMARK

EMPTY PARCELS

ABUTTING STOREFRONT TO SIDEWALK

FORMER FACTORY

POOR PLANNING

MISMATCHING SIDEWALK

ABANDONED BUILDINGS

EXISTING SOUTHEAST VIEW 1

EXISTING SOUTH VIEW 3

ABANDONED BUILDINGS

PROPERTIES FOR SALE NEED

NEED FOR RECREATIONAL ACTIVITY

WIDE STREET WITH LOW TRAFFIC VOLUME NO DISTINCT PARALLEL PARKING

EXISTING NORTHWEST VIEW 2

Figure 5.12 - Existing northwest view.

ACCESS FROM MICHIGAN AVE

VIEWS DOWN 20TH STREET CROSSING

5.14 - Proposed plan.

EXISTING NORTHEAST VIEW 1

EXISTING NORTH VIEW 2

GRAFFITI WALL

MINUTE WALK TO STADIUM

5 MINUTE WALK TO MAY CREEK GREENWAY

VIEWS TO STADIUM

DCFC OWNED PROPERTY

GATEWAY BRIDGE

HISTORIC BRICK DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL

EMPTY LOT ABANDONED BUILDING

POSSIBILITY FOR MARKET

5.23 - Proposed plan.

UNWELCOMING BARRIER LARGE INTERSECTION VIEWS TOWARDS AMBASSADOR BRIDGE

LACK OF PEOPLE EXISTING SOUTH VIEW

SLOWING DOWN TRAFFIC

WIDE ROAD WITH NO MARKINGS

CREATE AXIS WITH 20TH STREET

EXISTING NORTH VIEW

VERY FEW STREET TREES

Imagine the final whistle blows at the stadium. Now what happens across the streets surrounding it? Too often, stadium districts are designed with a focus on pre-game excitement and direct access to the venue, while the moments that follow are overlooked. This investigation challenges that limited scope by proposing a strategic mobility network that transforms the area into a continuous and adaptable urban experience. The design framework emphasizes the importance of streets as more than conduits for foot traffic. Streets are organized into a clear hierarchy, where primary corridors like 20th Street carry the weight of concentrated movement and activity, while secondary streets such as 14th Street serve as flexible connectors that support various tempos and uses. These corridors operate together as a network that remains relevant before, during, and after an event. The inclusion of planned public infrastructure like the Joe Louis Greenway and the May Creek Greenway strengthens this network, introducing opportunities for long-term vibrancy and pedestrianoriented mobility. The proposal positions the stadium not as an isolated destination but as one component within a broader urban field shaped by spatial logic, behavioral patterns, and infrastructural rhythm. The investigation frames streets as adaptable spaces that encourage lingering, movement, and engagement across different time frames. Public space within the district must respond not just to episodic crowds but also to the everyday needs of residents, workers, and visitors. The design approach responds to multiple temporal conditions by creating layered experiences that accommodate varying

levels of activity. Rather than fading into inactivity after the final whistle, the district can transition smoothly into a post-event phase of dining, strolling, or gathering. This strategic approach challenges the idea that stadiums are single-purpose destinations and instead supports the development of streets as a framework for urban life. Evidence supports the importance of rethinking these environments. According to a study published by OneFootball, 23 percent of Premier League fans leave matches early. In a broader context, a survey reported by 102.7 MIX FM reveals that 80 percent of people in the United States have left a major event early to avoid traffic. These behaviors highlight a missed opportunity in the current planning of event-based districts. They reveal a need for streets that can hold attention and function as more than exit routes. While the design proposal focuses on Corktown, the underlying framework applies to a wide range of urban contexts. Future work should explore how mobility networks can continue to evolve alongside shifting patterns of urban movement and public space use. The findings argue for a new understanding of the stadium district, where vibrancy is not bound to the game but carried forward by the streets themselves.

6.1 - Conceptual framework.

J.H. Kraay (1986) Woonerfs and Other Experiments in The Netherlands

Alain Chiaradia, Jorge Gil, & Noah Radford (2007) Space Syntax: The Role of Urban Form in Cyclist Route Choice in Central London

Jill Grant (2007) Mixed-Use Theory and Practice: Canadian Experience with Implementing a Planning Principle

Giuseppe Buttazzo, Aldo Pratelli, & Sergio Solimini (2009) Optimal Urban Networks via Mass Transportation

Dominique Wilkins (2016) The Effect of Athletic Stadiums on Communities, with a Focus on Housing

Scott Ralston & Bill

and

(2018) Creating Vibrant Cities through Sports-Anchored Districts

Olivia Viorst (2023) Impact of a Sports Stadium on a Neighborhood

from Maine

6.2 - Methodological framework.

Sim, David. Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life. Foreword by Jan Gehl, Island Press, 2019.

Boston Transportation Department. Boston Complete Streets Design Guidelines. Designed by Toole Design Group and Utile, City of Boston, 2013.

City of Detroit. Greater Corktown Neighborhood Framework Plan. Planning and Development Department, 2020.

Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. 1960.

Abbiasov, Timur, and Dmitry Sedov. "Do Local Businesses Benefit from Sports Facilities? The Case of Major League Sports Stadiums and Arenas." Regional Science and Urban Economics, vol. 98, Jan. 2023.

Ahlfeldt, Gabriel, and Wolfgang Maennig. "Stadium Architecture and Urban Development from the Perspective of Urban Economics." Urban Studies, vol. 34, no. 5, 2009, pp. 629646.

Chen, Zheyan, and Bo Huang. “Achieving Urban Vibrancy through Effective City Planning: A Spatial and Temporal Perspective.” Cities, vol. 152, Sept. 2024.

Cottrill, Ben. "Rethinking the Relationship between Stadiums and Public Space." Journal of Urban Design, vol. 22, no. 1, 2023, pp. 1-51.

Danko, Aaron. "Walkability 2.0: A Specific Focus on the Reintroduction of Walkability in Detroit." Thesis, 2023, pp. 1-89.

Fite, David N. "Detroit: Revitalizing Urban Communities." Masters Theses, 2021, thesis 1046.

Guo, Xiao, and Yimin Sun. "A Thermal Comfort Assessment on Semi-Outdoor Sports Stadiums Located in 3 Different Climate Zones in China." Building and Environment, vol. 183, 2020, pp. 1-24.

Kim, Hyun Yong Erick. "Stadium City: A Modern Re-imagination of the Sports Complex." Journal of Urban Architecture, vol. 45, no. 4, 2022, pp. 1-57.

Jones, Calvin, et al. “Can Regional Sports Stadia Ever Be Economically Significant?” Regional Science Policy & Practice, vol. 2, no. 1, June 2010, pp. 63–78.

Kingsley, Karen. "New Orleans Architecture: Building Renewal." Journal of Architectural History, vol. 94, no. 3, 2020, pp. 716-725.

Lefever, Zach C. “Sustainable Architecture in Athletics: Using Mass Timber in an Old-Fashioned Field.” Masters Theses, 2023, thesis 1301.

Pramod, Gopika. "Stadium Design: Guidelines and Impact on the Urban Level." The Architects Diary, 21 Dec. 2023, thearchitectsdiary.com/stadiumdesign-guidelines-and-impact-onthe-urban-level/.

Uchida, Atsuhiko, Taishin Kameoka, Takeshi Isec, Hidetoshi Matsui, and Yukiko Uchida. "Social Factors of Urban Greening: Demographics, Zoning, and Social Capital." Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 38, 2019, pp. 1-12.

Schmid, Franziska, Anna Hersperger, Adrienne Gret-Regamey, and Felix Kienast. "Effects of Different Land-Use Planning Instruments on Urban Shrub and Tree Canopy Cover in Zurich, Switzerland." Land Use Policy, vol. 67, 2017, pp. 1-10.

Viorst, Olivia. "Impact of a Sports Stadium on a Neighborhood." Thesis, 2022, pp. 1-48.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, 1961.

Nelson, Arthur C. "Prosperity or Blight? A Question of Major League Stadia Locations." Economic Development Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 3, 2001, pp. 255–265.

Luo, Su. "A Brief Analysis of the Economic Impact of Major Sporting Event on the Host City." Accessed 9 Oct. 2024.

Ben-Joseph, Eran. "Changing the Residential Street Scene: Adapting the Shared Street (Woonerf) Concept to the Suburban Environment." Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 61, no. 4, Autumn 1995, pp. 434-446.

Raford, Noah, and David R. Ragland. "Space Syntax: An Innovative Pedestrian Volume Modeling Tool for Pedestrian Safety." 11 Dec. 2003.

Beyard, Michael D., et al. Developing Retail Entertainment Destinations. 2nd ed., ULI – the Urban Land Institute, 2001. (First Edition Title: Developing Urban Retail Centers)

Luo, Su. "A Brief Analysis of the Economic Impact of Major Sporting Event on the Host City." Accessed 9 Oct. 2024.

Euchner, Charles C. Playing the Field: Why Sports Teams Move and Cities Fight to Keep Them. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, p. 65.

Figure 1.1 - Detroit City Football Club players celebrating with their supporters (2021). Credits: Sports Illustrated

Figure 1.2 - Approaching Keyworth Stadium on Goodson Street at the south west entrance (2024).

Figure 1.3 - Purchasing tickets after entering the gate 2 entrance off of Roosevelt Street (2024).

Figure 1.4 - Looking at merchandise tents and concession stands (2024).

Figure 1.5 - Watching the DCFC host Indy 11 while sitting in the northern, city admission stand (2024).

Figure 1.6 - Former Southwest Detroit Hospital (2024). Credits: Urbanize Detroit

Figure 1.7 - 15.25 Acres of land acquired by Detroit City Football Club in Corktown (2025). Credits: Google Earth

Figure 1.8 - Cornbelt Beef Corp. a building acquired by the DCFC (2023). Credits: James C. Ritchie

Figure 1.9 - Sidewalk on Michigan Avenue lined with shops and restaurants (2023). Credits: Let's Detroit

Figure 1.10 - United Soccer League (USL) Championship stadium re-locations in the last fifteen years.

Figure 2.1 - A lack of urban vibrancy on Michigan Avenue in Corktown due to the inability to utilize empty space (2024).

Figure 2.2 - Street signage for Michigan Avenue and 20th Street, node at which the future stadium rests (2025).

Figure 2.3 - Intersection and node of 20th Street and West Vernor Street (2025).

Figure 2.4 - Intersection and node of 20th Street and Bagley Street (2025).

Figure 2.5 - One out of nine principles in the book Soft City | Credits: Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life Principles.

Figure 2.6 - Street section of Woodward Avenue outside Little Caesars Arena and Brush Park diagrammed.

Figure 2.7 - District Detroit site plan.

Figure 2.8 - The positives and negatives street and public space qualities of Woodward Avenue outside of LCA.

Figure 2.9 - Image of Pistons fans and pedestrians using Park Avenue merely as a corridor to pass through.

Figure 2.10 - Plan view of space alloted for game day activities on Sproat Street.

Figure 2.11 - Standing on Columbia Street's vehicle-free, pedestrian friendly street with views towards Comerica Park.

Figure 2.12 - First quality on Columbia Street.

Figure 2.13 - Second quality on Columbia Street.

Figure 2.14 - Third quality on Columbia Street.

Figure 2.15 - Statistic of respondents that want streets that are safe (2020). | Credits: Streets For People

Figure 2.16 - Statistic of respondents that want streets that are vibrant and inviting (2020). | Credits: Streets For People

Figure 2.17 - Statistic of respondents that want streets that are free of speeders (2020). | Credits: Streets For People

Figure 2.18 - Statistic of respondents that want streets that are accessible on feet (2020). | Credits: Streets For People

Figure 2.19 - Statistic of respondents that want streets that are complete (2020). | Credits: Streets For People

Figure 3.1 - Streetscape of Michigan Avenue with man biking on the red brick pavers (2024).

Figure 3.2 - Greater Corktown Study Area. | Credits: City of Detroit

Figure 3.3 - Intersection of Bagley and 10th Street looking west on Bagley Street. | Credits: City of Detroit

Figure 3.4 - Kevin Schronce. | Credits: Linkedin

Figure 3.5 - Alex Wright. | Credits: Linkedin

Figure 3.6 - Melissa Dittmer. | Credits: Linkedin

Figure 4.1 - Obstructed sidewalk on the corner of Michigan Avenue and 20th Street outside the future stadium (2024).

Figure 4.2 - Students views flipbooks during sketch problem I presentation (2024).

Figure 4.3 - Sidewalk view outside of McShane's Irish Pub (2024).

Figure 4.4 - Random page of flipbook two from sketch problem I (2024).

Figure 4.5 - On pathway of Roosevelt Park outside of Michigan Central Station (2024).

Figure 4.6 - Claudia flipping through flipbooks during sketch problem I presentation (2024).

Figure 4.7 - Overlooking construction near the Ralph C. Wilson Centennial Park (2024).

Figure 4.8 - Flipbook image A. (2024).

Figure 4.9 - Flipbook image B. (2024).

Figure 4.10- Flipbook image C. (2024).

Figure 4.11 - Flipbook image D. (2024).

Figure 4.12 - Flipbook image E. (2024).

Figure 4.13 - Flipbook image F. (2024).

Figure 4.14 - Flipbook image G. (2024).

Figure 4.15 - Flipbook image H. (2024).

Figure 4.16 - Flipbook image I. (2024).

Figure 4.17 - Flipbook image J. (2024).

Figure 4.18 - Flipbook image K. (2024).

Figure 4.19 - Flipbook image L. (2024).

Figure 4.20 - Flipbook image M. (2024).

Figure 4.21 - Flipbook image N. (2024)

Figure 4.22 - Flipbook image O. (2024).

Figure 4.23 - Flipbook image P. (2024).

Figure 4.24 - Flipbook image Q. (2024).

Figure 4.25 - Flipbook image R. (2024).

Figure 4.26 - Flipbook image S. (2024).

Figure 4.27 - Flipbook image T. (2024).

Figure 4.28 - Flipbook image U. (2024).

Figure 4.29 - Flipbook image V. (2024).

Figure 4.30 - Flipbook image W. (2024).

Figure 4.31 - Flipbook image X. (2024).

Figure 4.32 - Flipbook image Y. (2024).

Figure 4.33 - Flipbook image Z. (2024).

Figure 4.34 - Flipbook image AA. (2024).

Figure 4.35 - Flipbook image AB. (2024).

Figure 4.36 - Flipbook image AC. (2024).

Figure 4.37 - Flipbook image AD. (2024).

Figure 4.38 - Flipbook image AE. (2024).

Figure 4.39 - Flipbook image AF. (2024).

Figure 4.40 - Flipbook image AG. (2024).

Figure 4.41 - Flipbook image AH. (2024).

Figure 4.42 - Flipbook image AI. (2024).

Figure 4.43 - Linking sequential movement for a student.

Figure 5.1 - Multi-Helix design approach

Figure 5.2 - Corktown map.

Figure 5.3 - Existing south view.

Figure 5.4 - Existing east View.

Figure 5.5 - Existing southeast view.

Figure 5.6 - Proposed section.

Figure 5.7 - Proposed plan.

Figure 5.8 - 14th Street and West Fisher Service Drive during winter (2025).

Figure 5.9 - Connection between Northern Corktown and Corktown designed for cyclists and improved circulation.

Figure 5.10 - Existing southeast view.

Figure 5.11 - Existing south view.

Figure 5.12 - Existing northwest view.

Figure 5.12 - Existing northwest view.

Figure 5.13 - Proposed section.

Figure 5.14 - Proposed plan.

Figure 5.15 - For sale property on 20th Street across future stadium, zoned M4 Industrial (2025).

Figure 5.16 - Vibrant scenes as tailgaters gather around the stadium.

Figure 5.17 - Existing northeast view.

Figure 5.18 - Existing north view.

Figure 5.19 - Existing northwest view.

Figure 5.20 - Existing southwest view.

Figure 5.21 - The Corktown community forms as families shop at and enjoy the markets.

Figure 5.22 - Proposed section.

Figure 5.23 - Proposed plan.

Figure 5.24 - 20th Street and Newark Street sidewalk conditions (2024).

Figure 5.25 - Existing south view.

Figure 5.26 - Existing west view.

Figure 5.27 - Existing northeast view.

Figure 5.28 - Existing north view.

Figure 5.29- University students experience a concert performance at the end of 20th Street.

Figure 5.30 - Proposed section.

Figure 5.31 - Proposed plan.

Figure 5.32 - 20th Street and Bagley Street views toward the Ambassador Bridge (2025).

Figure 6.1 - Conceptual framework.

Figure 6.2 - Methodological framework.

Figure 6.3 - Process sketch diagramming negative space shaping into positive space.

Figure 6.4 - Sketch of 20th Street and Bagley Street redesign.

Figure 6.5 - Final review of Beyond The Game (2025). | Credits: Virginia Stanard

- FLIPBOOK 1

Giovanni - Okay so yeah um... the project we'll start with that. I guess it's changed a bit since I last spoke with you. It's,... I guess, less centered around an architectural aspect of the stadium and its components, but more centered around an urban aspect, I would say. Kind of this term that I'm using is urban vibrancy, which is the dynamic, social, and economic activity within a city characterized by the liveliness of its public spaces, diversity of land use, and then the frequency of human interaction. So kind of trying to bring that urban vibrancy with a stadium as the component or like landmark there. So that's kind of where I'm at with it now, trying to understand the way people kind of move about a city, interact with massing and voids within places, how people cross paths with each other and interactions. So just kind of starting off with that, so you kind of know where I'm at, I don't know if there's anything that you have heard or talked about with, is it with progressive, your architects on board?

Alex - Yeah, they're still leading the design for sure.

Giovanni - Yeah, yeah. Is there any talks about urban concerns or constraints or is it primarily site-focused [with ProgressiveAE].

Alex - Mostly, well, so the progressive is like the building, like actual building, and Smithgroup is sort of like the consultant on like the, let's just say the campus, right? Like the space around it. Umm, let me see if I can find [the renderings so you know what I'm talking about]

Giovanni - Yeah that'd be cool.

Alex - Um, for the most part we're focusing on that property where the stadium will be, but like the development includes more parcels, right. Parcels which are still assembling, but in terms of like the look of it there hasn't been much, I would say, like in terms of the um space, like there's been some conversation around like the entrance and exit and like what's the best way to, um, let me see.

Giovanni - Yeah, I'm sure there's like street improvements. Like, I don't know if you've seen, I'm sure there's some looking into Michigan Central's plan and kind of Ford's plan.

Alex - Right.

Giovanni - And kind of connecting [Michigan Central Station] and having the relationship with either Roosevelt Park or even the station itself. Like along 15th Street, I believe, they have like that whole walkway that's kind of developed. And I could see something with, I think on like 20th Street.

Alex - Yeah, this is, I'm not sure how this is for this specific conversation, (shows Giovanni a diagram produced by Smithgroup) but like sort of like what I mean by the spaces is like. So that's Michigan Avenue.

Giovanni - Yep.

Alex - And, like this is going to be parking and maybe something on top of it, and then this is stadium. And then this! So like this is viaduct, right. So it's like this because if folks are going to be

coming up on 20th [street] or this way from the trains station, like this is an important space for that.

Giovanni - Yes, an important node.