THE HEALING POWER OF ART

Meet Aida Murad, the current artist-inresidence exhibitor at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Winter 2023

Two new schools, one common thread Hands-on healing Bridging health care and the environment WINTER 2023 12 6 18

From the Archives

This anatomy/physiology textbook was used by Alice Catherine Scales, a dental hygiene student in the 1930s. The first women in Georgetown’s dental school were a part of this yearlong program. Though some are now online, textbooks continue to be an important teaching tool. Last year, Georgetown professors Cindy L. Farley, CNM, Ph.D., FACNM, and Edilma L. Yearwood, Ph.D., PMHCNS-BC, FAAN, co-edited textbooks that were recognized with American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year awards.

6 12 18

Editor’s Letter Check Up News & Research Student Point of View On Campus Alumni Connections Book Corner Reflections on Health Robyn Begley, DNP, R.N., NEA-BC, FAAN (NHS’77) 3 2 28 26 36 39 40

Photo: Lynn Conway, Georgetown University Archivist

Editor’s Letter

Among the thought-provoking profiles in this issue of Georgetown Health, you will meet Samantha Ahdoot, M.D. (M’99), who serves as Environmental Health Champion for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In her conversation with Georgetown writer Bhriana Smith, Ahdoot mentions a book called Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy, by Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone. This notion of “active hope” doesn’t require optimism so much as a realistic and creative response in the face of sometimes overwhelming problems.

Ahdoot points out that many Georgetown students exhibit active hope when faced with a daunting challenge. “The students see a problem,” she says, “and they develop a path that through their own particular circumstance can make things better.”

I recently had a conversation with another alumnus, Bill Licamele, M.D. (C’68, M’72, R’74, W’76, Parent’01, ’04, ’07), who shared a similar observation about Georgetown students: they work together to find solutions. He pointed out that students wanted to better foster connections with peers, alumni, and faculty so they started Learning Societies. He is proud of student-driven innovations, like the new longitudinal academic track in environmental health. “At Georgetown, we look out for each other,” he says.

It is great to see Georgetown students fighting for what they believe in. Their tenacity has been on Bill’s mind as he battles liver cancer. (On the last page of this issue, you can read about the BellRinger bike team that rode in his honor.)

In another feature, meet Aida Murad, the current artist-in-residence at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. When faced with a health condition that made it difficult for her to hold a paintbrush, she started using her hands and arms instead. Now her art—as well as her resiliency—is bringing comfort to patients, families, and caregivers alike.

This issue also provides an opportunity to hear from the leaders at the new School of Nursing and School of Health. In true Georgetown spirit, they are demonstrating active hope as they listen to what students and faculty want to accomplish and plan for future programs that address, among other goals, the need for greater health equity.

There’s much to explore in these pages, with stories that take you from Georgia to Wisconsin, Argentina to Ukraine. We hope they leave you feeling inspired and hopeful.

In October 2022, the Hoya community lost Lori Wilson, M.D. (C’88, M’94). Dr. Wilson was the subject of the Reflections in Medicine section in our Summer 2022 issue. “It’s so import ant to give back,” she shared. “I am committed to servant leadership, and try to do God’s work by taking care of our brothers and sisters.” We mourn her passing but celebrate the spirit of a life well-lived.

Office of Advancement

R. Bartley Moore (SFS’87) Vice President for Advancement

Amy Levin

Associate Vice President for Communications Erin Greene Assistant Vice President of Creative

Georgetown Magazine Staff

Camille Scarborough, Editorial Team Lead Jane Varner Malhotra (G’21), Features Editor Elisa Morsch (G’20), Creative Director

Editorial Team

Gabrielle Barone, Karen Doss Bowman, Colin Carlson, Kate Colwell (G’20), Michael Miller, Patti North, Sara Piccini, Bhriana Smith, Karen Teber, Heather Wilpone-Welborn, Lauren Wolkoff (G’13), Kat Zambon

Design Team

Wanda Felsenhardt, Ethan Jeon, Shikha Savdas Project Manager Hilary Koss

University Photographer Phil Humnicky

Georgetown Health Magazine 2115 Wisconsin Ave., NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20007-1253

Feedback and story ideas: healthmagazine@georgetown.edu

Address changes: alumnirecords@georgetown.edu

Winter 2023 | Georgetown Health Magazine

Georgetown Health Magazine is distributed free of charge to alumni, parents, faculty, and staff. The diverse views in the magazine do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editors or official policies of the university.

Georgetown University provides equal opportunity in employment for all persons, and prohibits unlawful discrimination and harassment in all aspects of employment because of age, color, disability, family responsibilities, gender identity or expression, genetic information, marital status, matriculation, national origin, personal appearance, political affiliation, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, veteran’s status, or any other factor prohibited by law. Additionally, the university will use good-faith efforts to achieve ethnic and gender diversity throughout the workforce. The university emphasizes recruitment of women, minority members, disabled individuals, and veterans. Inquiries regarding Georgetown University’s nondiscrimination policy may be addressed to the Director of Affirmative Action Programs, Institutional Diversity, Equity & Affirmative Action, 37th and O Sts. NW, Suite M36, Darnall Hall, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20057, or call 202-687-4798.

© 2023 Georgetown University

2 Georgetown Health

—Camille Scarborough, Editorial Team Lead

Photo: Courtesy of Lori Wilson, M.D.

Event focuses on teens and social media

journalists before testifying at an October 2021 hearing of the Senate Commerce Committee.

“What Facebook has found is that if you take a brand-new Instagram account and you follow moderate topics like healthy recipes, the algorithm will amplify that interest until you are led to eating disorder content,” Haugen said.

n n Frances Haugen, the former Facebook project manager turned whistleblower, discussed “How Social Media Impacts Teen Health” at a virtual event hosted by the Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development earlier this year.

“It may take us years to get the social media that we deserve as a society,” she said at the event. “But I think there is an opportunity for young people to claim their agency by supporting or mentoring each other.”

With previous stints at Google, Pinterest, and Yelp, Haugen was recruited to be a project manager for the civic integrity team at Facebook. Over time, she says, she became concerned by Facebook’s business practices regarding safety, including a pattern of prioritizing profits over the mental health of its users.

After contacting a law firm that represents whistleblowers, Haugen shared her story with members of Congress and

Algorithms that favor engagement-based content ultimately promote content that is more extreme and polarizing, and less likely to draw attention to the work of content creators from diverse backgrounds, she explained.

“If you do not think about these issues, your algorithms will reinforce the biases of your society,” Haugen said. “So if content from African Americans gets clicked on less than content from people who are not racial minorities, the algorithm will steer attention away from them. There are real problems there around equity.”

Haugen’s future plans include helping young people build resiliency networks and creating open source tools that allow users to report misinformation posted on Facebook and track the company’s response.

“We must use our power as a group to responsibly achieve honesty, transparency, and accountability on how social media is managed moving forward,” said Lee Jones, M.D., dean for medical education at the School of Medicine. “Jump in and be involved. Get your kids, get your brothers and sisters involved.” n

U.S. News & World Report ranked MedStar Georgetown University Hospital as one of the top 50 cancer programs in the nation for 2022–2023. This designation recognizes the outstanding clinical and research excellence provided by MedStar Georgetown and Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

WINTER 2023 3

CHECK UP

iStock

Photo:

Improving cancer detection for dense breasts

n n A two-pronged approach to imaging breast density in mice, developed by researchers at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, resulted in better detection of changes in breast tissue, including spotting early signs of cancer. The researchers hope that this approach will be translated from mice and improve breast imaging for people.

“Having a means to accurately assess mammary gland density in mice, just as is done clinically for women using mammograms, is an important research advance,” says Priscilla A. Furth, M.D., emerita professor of oncology and medicine at Georgetown Lombardi and corresponding author of the study that appeared recently in the American Journal of Pathology. “This method has the benefit of being applicable across all ages of mice and mammary gland shapes.”

An innovative analytic computer program, developed by Georgetown alumnus Brendan L. Rooney (C’20) while working as an undergraduate in Furth’s lab, allowed for sorting of mammary gland tissue to one of two imaging assessments.

“The idea for the analytic program came from routine visual observations of tissue samples and the challenges inherent in observing differences in breast tissue with just a microscope. We found that visual human observations are important, but

having another read on abnormalities from optimal imaging programs added validity and rigor to our assessments,” says Rooney, the lead author of the study. “Not only does our program result in a high degree of diagnostic accuracy, it is freely available and easy to use.”

Rooney notes that he could not have done this research without Furth’s mentorship, starting as early as his first year at Georgetown. “The support that I received from Dr. Furth enabled me to introduce an idea and execute the project from start to finish—it provided an unparalleled experience in hands-on learning,” he says. n

Targeting brain cancer biomarkers

n n Biomarkers that could be targets for novel drugs to treat glioblastoma brain tumors have been identified by investigators at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Currently, the drug most often used to treat glioblastoma, temozolomide, is uniquely able to cross the blood/brain barrier to attack the tumor, but resistance develops rapidly, and many patients do not survive for more than a year after diagnosis. This new finding provides early evidence that there may be a benefit in targeting specific alterations in cancer cells with newer agents once a patient’s tumor becomes resistant to temozolomide.

“As a field, we have struggled to deal with the short-term effectiveness of temozolomide, as many of the drugs used successfully in other cancers are disappointing when they are subsequently tested in glioblastoma clinical trials. One way to

deal with this problem is to learn enough about how we can target features that help drug-resistant glioblastoma survive,” says Rebecca B. Riggins, Ph.D., associate professor and associate director of education and training at Georgetown Lombardi and co-corresponding author of the study that appeared in the June 2022 issue of Science Advances

“We focused on the details of how temozolomide damages DNA to help radiation treatments work better. Our team found that temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma relies on a protein called CLK2, and that inhibiting the activity of CLK2 could cause widespread confusion, leading to cancer cell death.”

The investigators are now undertaking studies in small animal models, where they will test to see if the novel CLK2 inhibitor can efficiently enter the brain and shrink temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma. n

4 Georgetown Health

iStock CHECK UP

Photo:

On the nose

n n The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has awarded a Georgetown University Medical Center research team $23.6 million in research funding to study treatments for acute rhinosinusitis. The study is led by Dan Merenstein, M.D., professor of family medicine at Georgetown’s School of Medicine and professor of human science at the School of Health.

Every year in the U.S., one in seven adults is diagnosed with acute rhinosinusitis, an inflammation of the nose and sinus passages. One in five adults are prescribed antibiotics, though nasal sprays such as intranasal corticosteroids (INCS), over-the-counter supportive treatment, or saline nasal irrigation (SNI) may also help improve symptoms.

“Acute rhinosinusitis leaves people feeling miserable and desperate for relief, and their care providers eager to help,” says Merenstein, director of research programs for Georgetown’s Department of Family Medicine. “Unfortunately, in the absence of clinically proven treatments, providers often prescribe antibiotics. We want to know if there’s a better way to treat patients and alleviate symptoms more quickly, while also figuring out who really benefits from antibiotics.”

Nawar M. Shara, Ph.D., director of biostatistics, informatics and data science at MedStar Health Research Institute and associate professor, is co-investigator for the study. The research collaboration also involves the University of Washington, UCLA, Virginia Commonwealth University, Penn State, and University of Wisconsin.

Together, the investigators will recruit more than 3,700 people diagnosed with acute rhinosinusitis for the largest clinical trial of its kind. The randomized clinical trial will compare outcomes among treatments with antibiotics, INCS, and antibiotics plus INCS. Some arms of the study will include a placebo. Merenstein’s award has been approved pending completion of a business and programmatic review by PCORI staff and issuance of a formal award contract. n

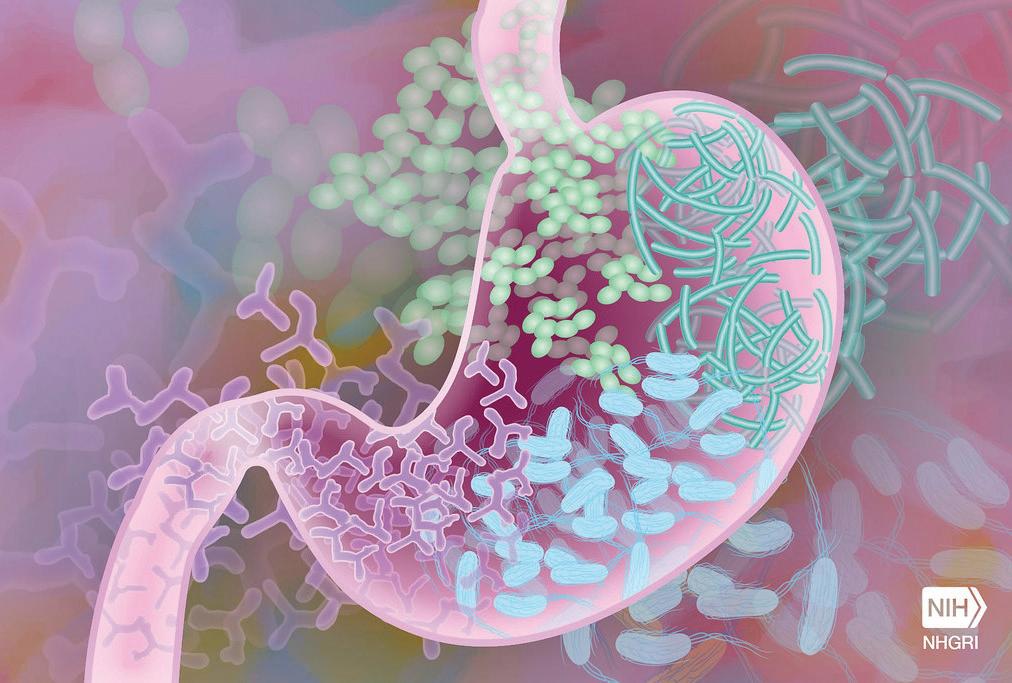

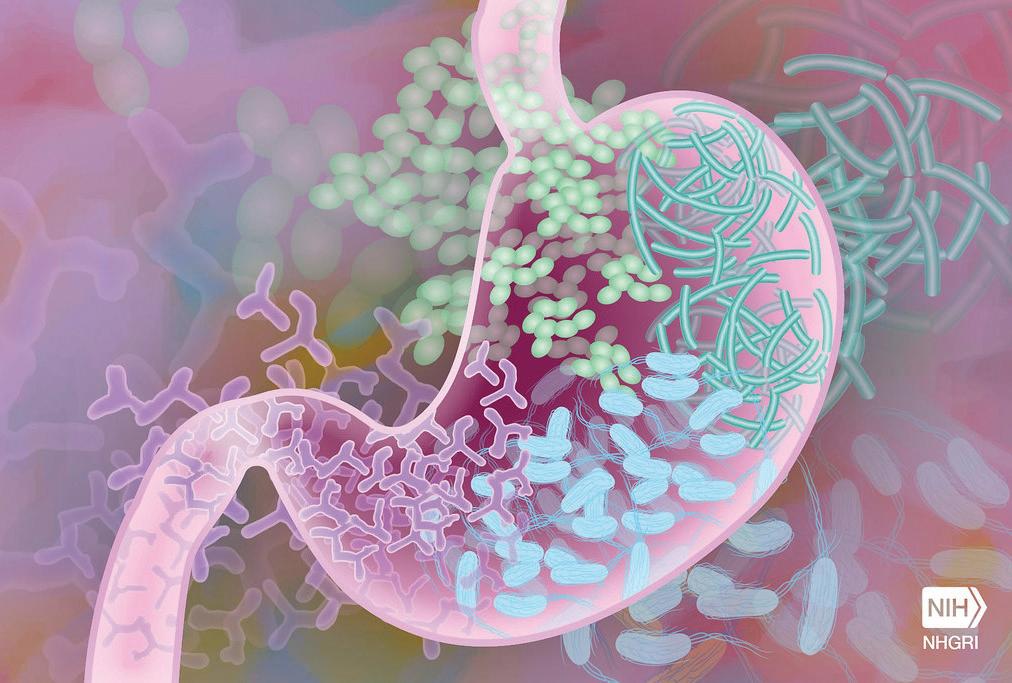

Heart failure’s relation to gut health

n n Some people who experience heart failure have less biodiversity in their gut or have elevated gut metabolites, both of which are associated with more hospital visits and greater risk of death, according to a systematic review of research findings led by Georgetown University School of Nursing.

The gut microbiome is a delicately balanced ecosystem composed primarily of bacteria as well as viruses, fungi, and protozoa. It can affect cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of death in the United States.

The investigators looked at seven years of genetic, pharmacologic, and other types of research from around the world to generate a wide perspective on how the microbiome can influence heart failure. The investigators zeroed in on one harmful metabolite, trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), that can be produced by churning gut microbiota when full-fat dairy products, egg yolks, and red meat are consumed.

“There is now an appreciation of a back-and-forth relationship between the heart and elements in the gut,” says Kelley Anderson, Ph.D., FNP, CHFN, associate professor of nursing at Georgetown and corresponding author of the study. “We are currently developing a forward-looking study to evaluate the microbiome in patients with heart failure.

The analysis, which appeared in June’s Heart Failure Reviews, was also authored by Emily Couvillon Alagha, Emma Mykityshyn, and Casey French at Georgetown and Erin P. Ferranti and Carolyn Miller Reilly at Emory University. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to the study and no outside funding. n

WINTER 2023 5

Photos: iStock / Darryl Leja, National Human Genome Research Institute, NIH

6 Georgetown Health

Photos: Phil Humnicky

TWO NEW SCHOOLS ONE COMMON THREAD

By Lauren Wolkoff | Design By Wanda Felsenhardt

Georgetown’s commitment to health—to improving the human condition—has taken many forms over the course of the university’s history.

The list is long and the roots are deep, beginning with the establishment of the School of Medicine 171 years ago. In 1903, the university founded the original School of Nurs ing, which became the School of Nursing & Health Studies (NHS) in 2000.

This year, in a bid to reimagine what health sciences can look like both in and out of the classroom, Georgetown took a bold step by sunsetting NHS and establishing two new and distinct schools: the School of Health and the School of Nursing. The move culminated a process of nearly three years of consultation and strategic planning. Both schools officially launched July 1 of this year with a renewed focus on health equity.

“Having two schools launched at the same time really speaks to the extraordinary nature of this moment and the value that Georgetown places on the health sciences,” says Edward B. Healton, M.D., MPH, executive vice president for health sciences at Georgetown University Medical Center. “We now have an unprecedented opportunity to define a new era in health and fully live out our Jesuit values of social justice and health equity.”

With this new direction comes new leadership. Roberta Waite, Ed.D., PMHCNS, R.N., MSN, ANEF, FAAN, a professor of nursing who brings decades of experience work ing to advance health equity, was announced as dean of the

reconceptualized School of Nursing. Christopher J. King, Ph.D., MHSc, FACHE, associate professor and former chair of the department of health systems administration in NHS, was named the inaugural dean of the School of Health.

In announcing the plan for the schools, Georgetown Presi dent John J. DeGioia emphasizes the university’s long-standing focus on improving health, calling it “integral to our mission as a Catholic and Jesuit institution.”

“This next phase of our work enables us to deepen our com mitment to the largest health care profession—nursing—and develop new interdisciplinary and collaborative opportunities across the domains of health—both within our Medical Cen ter, and also across our Main Campus and Law Center—to emphasize a shared focus on creating healthier communities,” DeGioia says.

From cells to society: a health equity lens Georgetown’s investment in expanding its health footprint comes at a pivotal time. As COVID-19 nears the end of its third year, the pandemic is a “powerful reminder of the chal lenges we face and the urgency of envisioning new respons es to health education, service, policy, and equity issues,” DeGioia says.

The glaring health inequities revealed by the pandemic underscore the need to reassess how health education and research infrastructure can better serve everyone. Healton says the Medical Center specifically, and the university more broadly, view the two schools as a powerful vehicle to

WINTER 2023 7

strengthen health from “cells to society”—or from research laboratories out to the community. Both schools aim to develop curious, empathetic learners and lifelong scholars who are committed to creating the conditions for health equity, and taking a systems approach to health.

“This transformation of the health sciences will foster more cross- and interdisciplinary collaboration that, ultimately, will train health professionals who are extremely well equipped to tackle the equity challenges we face,” Healton says.

The founding of the two new schools furthers Georgetown’s work at the intersection of health equity and racial justice through university initiatives such as the Health Justice Alli ance, Racial Justice Institute, and the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities. Healton says he anticipates great opportunities for collaboration in research, scholarship, and training with the School of Medicine, as well as George town’s clinical partner MedStar Health, along with other schools and programs across the university doing important work in advancing health.

Both new deans have been on a listening tour, meeting with those around campus to identify possible avenues for collaboration. They have also met with MedStar Health lead ership to explore opportunities in training and research.

Stephen R. T. Evans, M.D., MedStar Health’s executive vice president for medical affairs and chief medical officer, says MedStar Health sees tremendous opportunity to leverage the strengths of the School of Health and School of Nursing.

“As an academic health system, we want clinical leaders who are writing the textbooks, and not just reading them— people who are at the cutting edge of learning in creative and innovative ways,” Evans says. “With the two new schools we see enormous potential for collaboration in education, train ing, and furthering community health.”

Evans also notes that a strengthened partnership between MedStar Health and the university benefits medically under served communities.

“It’s a much different model to deliver care to a severely diabetic person with heart failure in an underserved area of Washington, D.C., who might have challenges related to transportation, food, or housing insecurity, than the model we would use with patients who do not face those challenges,” he says. “The academic partnership offers us infinite opportuni ties to further our work in all the communities we serve in a smart, thoughtful, and effective way.”

School of Nursing: where tradition meets innovation

Under Waite’s leadership, the launch of the nursing school reflects Georgetown’s renewed commitment to the largest health care profession—and to strengthening the school’s

equity lens. As a psychiatric and mental health clinical special ist, nurse educator, and nurse leader, Waite has dedicated her career to creating healthier communities.

Previously, she worked as the executive director of Drexel University’s Stephen and Sandra Sheller 11th Street Family Health Services, a nurse-managed community-based orga nization operated in partnership with Family Practice & Counseling Network. That experience informs her approach to leadership, in which she hopes to define the brand of the nursing school as an organization that is responsive to the needs of its community.

Waite is ever mindful of the paradox of creating something brand new that is also steeped in tradition, given the 120-year history of nursing education at Georgetown.

“What we need to appreciate is that, while we are a new school of nursing, we are a new school with a long, rich history,” Waite says. “You can’t extricate us from that history because it’s gotten us to where we are now, and people feel strongly connected to different phases of that journey.”

In particular, Waite sees how Georgetown’s Jesuit identity and values continue to define the school. The Jesuit credo of cura personalis, care of the whole person, is something faculty, staff, alumni, and students speak of consistently.

She wants to challenge the School of Nursing to “walk the talk” when it comes to embedding Jesuit values—including reckoning where efforts to be more inclusive, diverse, and equitable have yet to be fully realized.

“Change and growth take place when you’re in uncomfort able places,” Waite says. “No matter what degrees you have or position of power you may hold, it’s important to always be in a learner’s stance.”

Through on-campus and online/distance-learning nursing programs that span the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral lev els, Waite says she is excited to develop and cultivate nursing leaders who are “committed lifelong learners” with a focus on strengthening community, health, and humanization of all, while applying a racial and social justice lens.

“Nursing is about promoting health, and creating a culture of accountability, trust, and respect with communities,” she says. “Providing acute care is hugely important, but we also need to look at fostering well-being for individuals, families, and communities, while appreciating social and structural factors that shape health.”

Advancing the practice of nursing science is also a key goal, and Georgetown’s new Ph.D. in Nursing program with a concentration on health equity and ethics will continue the university’s mission to enhance its research endeavors.

Carrie Bowman Dalley, Ph.D., CRNA, serves as vice chair of executive faculty and program director in the Doctor of

8 Georgetown Health

Nurse Anesthesia Practice Program in the School of Nursing. Having been on faculty for 16 years, she appreciates how the formation of an independent nursing school is challenging her and her colleagues to break down silos and think creatively about how to work across academic units. The new school is creating a platform for heightened unity across nursing spe cialties, and a sense of shared identity.

“We need a stronger and more unified nursing voice to respond to some of today’s serious needs in health care,” she says. “There are many critical problems, but we all agree the most urgent is the pervasive racial inequity in health outcomes.

“An independent school of nursing allows us to take a highly focused, deep dive into these issues from the nursing perspective.”

While change can be uncomfortable for some, Bowman Dalley says it’s the optimal time for this shift.

“We’re not at the same place we were 20 years ago,” Bow man Dalley says. “We now have more than 900 students in a wide array of degree programs, and we’re eyeing further growth. To do this strategically, we need a strong, nursingfocused infrastructure—and a sharper focus than ever before.”

School of Health: charting a new path

As the new dean of the School of Health, King loves when peo ple ask him about the school’s name, which was intentionally conceived to leave room for evolution. It’s a conversation starter.

“People are intrigued by the name alone,” he says. “I see it as an opportune moment to share our ambition: to be trans formational, to be interdisciplinary, to be a world-class aca demic destination for advancing health.”

The new School of Health comprises three departments that were previously a part of NHS: health management and policy (formerly health systems administration), global health (formerly international health), and human science. The departments will continue to function in the same way,

and students will carry on with their programs of study without disruption.

Behind the scenes, however, an ambitious effort is under way to establish the new school’s distinct footprint. A design task force—comprising some 20 members from the School of Health and all corners of Georgetown University—has been working since July to shape options for the school’s identity and mission.

This collaborative process provides an opportune moment for those whose work or scholarship touches health to inform the architecture of a brand-new enterprise, according to King.

“We already know that health lives in different spaces across campus. How do we pull it all together in a thoughtful, meaningful way to advance knowledge and provide students with unique educational experiences that are responsive to contemporary times?”

The answers to this question are at the heart of the work of the design task force, which King co-chairs along with David Edelstein, Ph.D., vice dean of faculty in Georgetown College and a professor in the department of government, the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, and the Center for Security Studies.

While Edelstein’s background may seem an unconven tional fit for a task force focused on health, he has a deep understanding of Georgetown, including a track record in managing similar complex exercises.

“I am approaching this as a challenge we need to solve together, with all the people at the table who need to be there from a variety of disciplines,” Edelstein says. “This is something I have prioritized doing over the course of my career at Georgetown. As an outsider, I hope I can offer a fresh perspective to help guide this process.”

As one of its first actions, the task force did a comprehensive inventory of where health lives across the Georgetown campus. They found that Georgetown houses over 130 initiatives in the

WINTER 2023 9

“Nursing is about promoting health and creating a culture of accountability, trust, and respect with communities”

Roberta Waite, Ed.D., PMHCNS, R.N., MSN, ANEF, FAAN

Photo: Phil Humnicky

health space: 10 undergraduate programs; 40 graduate degree programs, and 80 centers, institutes, and other initiatives. King says this discovery process was eye-opening.

“This task force has been an incredible vehicle for us to learn about where we might be seeing duplication, and where we see resources or expertise that we weren’t tap ping into,” he says. The final definition of the school will be determined once the group submits its final report to DeGioia in Spring of 2023.

While the next chapter has yet to be written, the new school will draw on the best of NHS while also carving out something new, says Jan LaRocque, Ph.D., vice chair of

executive faculty at the School of Health, and associate pro fessor in the Department of Human Science.

“Building something new doesn’t mean we need to disman tle what we have completely,” LaRocque says. “To the con trary, we can see what we already have that is working well, see where we might enhance that, and build new streams to complement what we have.”

LaRocque sees an opportunity to position the School of Health as Georgetown’s hub for interdisciplinary collaboration around health.

“Having an independent School of Health makes sense to bring all this work together under one umbrella,” she says.

10 Georgetown Health

1851 1903 1970 2000

Georgetown Milestones in Health

“Georgetown’s focus on health has been, and will continue to be, about more than just health care as a medical construct.”

Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center authorized School of Nursing established School of Medicine established

Christopher J. King, Ph.D., MHSc, FACHE

Nursing school becomes the School of Nursing & Health Studies

1991

Edmund D. Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics established

Photo: Phil Humnicky

The new school will also continue and deepen the focus on health equity issues under King’s watch.

“Georgetown’s focus on health has been, and will continue to be, about more than just health care as a medical construct,” King says. “We approach our work understanding that there are populations that have historically been marginalized and disenfranchised. If we can fix the system for those populations, focusing on those who are most in need, everyone will benefit.”

King says the pandemic reminded everyone that we are a global society—what affects one community affects us all. To fix what ails the health care system more broadly, emerg ing health professionals need a strong equity lens, which the School of Health will help nurture.

Collective strengths

The decision to launch a School of Health and School of Nursing originated with the 2019 announcement of George town’s Health Sciences Strategy Initiative (HSSI) to deter mine future directions of health sciences at Georgetown.

Through the HSSI work, it was determined that establishing two distinct schools could capitalize on and contribute to Georgetown’s interdisciplinary strengths and better support Georgetown’s ambitions for research and education in nursing and health. A structural planning committee then engaged dozens of faculty and staff from across the Medical Center, main campus, the Law Center, and beyond to

imagine a broad range of opportunities for the future of health at Georgetown.

Both Waite and King look forward to potential collabora tions with other Georgetown schools to enhance their pro gramming. For example, nursing students may wish to start a business after becoming a nurse practitioner, and Waite envisions a future where they can also earn a master’s in busi ness administration from the McDonough School of Business.

In the School of Health, students and faculty might col laborate with the Law Center around medical-legal aspects of health, or with the McCourt School of Public Policy on health policy issues.

The possibilities for these types of collaboration are virtu ally limitless.

“One of our guiding principles throughout this process has been that health and health sciences should not just be the province of the Medical Center,” Healton says. “To the contrary, we expect this new direction will have ripple effects across campus that will reshape how we approach the most complex health problems.” n

O’Neill

Global Health Initiative launched, leading to 2022 Global Health Institute. Clinical partnership with MedStar Health renewed and expanded

School of Nursing and School of Health launched

2007 2016 2017 2022 2019

Health Justice Alliance established

Health Sciences Strategy Initiative begun to identify future directions of health sciences at Georgetown

WINTER 2023 11

Institute for National and Global Health Law launched

Photo: Lisa Helfert

Photo: Lisa Helfert

Hands-on healing

How Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center uses art for cura personalis

By Gabrielle Barone | Design by Ethan Jeon

Atypical day in the studio finds Aida Murad, the current artist-in-residence exhibitor at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, up to her elbows in paint—literally. After a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis left her temporarily unable to move her fingers or hold a paintbrush, the artist persevered by using her hands to apply paint to the canvas. The method opened Murad to a transformative healing experience, and she has continued to paint this way ever since.

Healing through art is a key value of Georgetown Lombardi, which aims to care for the whole person physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. Cura personalis extends beyond the patients to their whole network of families, health care providers, and visitors.

Murad’s paintings were installed at the cancer center in September 2022 as part of the Lombardi Arts & Humanities Program, established over 30 years ago to promote care of the whole person through music, visual arts, expressive writing, and dance. This year’s artist-in-residency exhibition by Murad, sponsored and envisioned by a former patient, is just one of many arts programs that Lombardi offers.

“Our basic premise in the beginning was to take art to the patients and the staff and the students and the medical providers, and infuse their days with creativity,” says Julia Langley, director of the Lombardi Arts and Humanities Program and an instructor at the School of Medicine.

Over the years, through philanthropic support, the program has expanded to offer a variety of art opportunities, including stretch breaks, collages, beadwork, poetry, narrative writing, and live music.

Musicians play in the cancer care waiting area and visit patients in their rooms at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

Langley notes that beyond the musical performance, the program is about relationship building. “The musicians have this wonderful ability to intuit what kind of music patients might need. Sometimes patients are able to discuss their preferences, and they have a really meaningful connection, which often ends with them talking for hours. If a patient is

nonverbal, the musicians check the monitors and look at blood pressure, heart rate, and breath rate, and observe how the patient responds to the music. Sometimes they’re tapping their fingers or moving their feet, and then the musicians know that they are communicating with the patient.”

Technology has opened new opportunities, too. Musicians now venture into rooms via iPad to play songs and interact with patients in a COVID-19-safe way, and art classes are offered online. Many of the attendees, Langley says, are actually based in areas other than Washington, D.C., across many different states and countries.

Bringing arts into the patient areas at Georgetown Lombardi offers people a contemplative respite from the sometimes overwhelming concerns they may experience in cancer care. Whether it’s a cello and hammered dulcimer duet in the lobby, an artist at a craft table with supplies for anyone to explore, or the calming, inviting, colorful works of Murad on the surrounding walls, the goal is to create an environment of care and well-being that appeals to the senses.

Langley believes having rotating, ever-changing art exhibitions is particularly important since people may come back for treatment or monitoring over a period of years or decades. “We want patients to see different facets of the clinic and how it continually evolves,” Langley says.

“From what we’ve heard, people really appreciate coming into Lombardi and seeing different works of art. They feel comforted by the fact that there’s lots of color and it’s clear that somebody cares about the space.”

WINTER 2023 13

Creativity and cura personalis

Murad also aims to offer that sense of care and compassion in her work.

“What Aida’s bringing is this soft, floating, flowing sensibility,” Langley says. “And I think the canvases are full of depth and breadth and possibility, which we really need these days.”

Noting that “it’s very easy” to connect the arts to cura personalis, Langley says that “the whole point of what the Lombardi Arts and Humanities Program is trying to do is to apply non-pharmacologic therapies to not only patients, but everyone in the hospital, because especially right now, everyone’s hurting.”

Creating an environment of positive, healing energy is a large part of Murad’s own artistic process, and also what she focuses on in her career as a spiritual artist, bringing in reiki and meditation to her creative undertakings.

She paints layer by layer, working on multiple projects at a time, to get in the right headspace for each painting.

Murad also brings this intention to her art process,

allowing the tone of the painting to determine how, where, when, and in what atmosphere she creates it.

She knows firsthand the impact that art can have in soothing a stressful process, as her headphones gave her a lot of comfort after being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

“What kept me sane during that time was my headphones, because music was my escape,” Murad says. “It was also my protection. It reminded me that there's still life, still color. Unfortunately there was no real visual art in the hospitals that I went to. So now with my second chance at a healthy life, I aim to create a healing and nourishing experience that I wished I had. I try to connect the art that I do with what patients are seeking.”

Bringing this mentality to her work, she created one piece that was all about fun, even if it didn’t fit with traditional expectations of art found in a hospital.

“Each painting represents a different intention, from the lightness of the sun to the struggle of climbing a mountain,” Murad says. “But one is about fun. That’s what people need also, to remember there’s still fun out there to experience.”

14 Georgetown Health

“Beyond adding art to the walls, I’m excited about giving this deep sense of belonging.” –Ami Aronson

Photos: Lisa Helfert

Art and admiration

Cancer survivor Ami Aronson took this philosophy, and Murad’s practice of art’s healing qualities, to heart during and after her treatment of Stage 3 melanoma. Working with the Lombardi Arts & Humanities Program, she wanted to bring Murad’s work to the walls of the cancer center at Georgetown.

“For cancer care, Georgetown is the embodiment of everything I was looking for,” Aronson says. “Cancer isn’t just a physical disease—it’s complex. And we need to be in a place where we feel safe. Here at Georgetown I feel safe and loved and treated with the best care. I couldn't have asked for a better experience.”

She took comfort in her local connections to Georgetown: her brother was born at the hospital, and her father went to undergraduate and medical school here. “I never thought I’d go to Georgetown for a cancer journey, but honestly, I can't imagine being anywhere else.”

During the treatment process, Aronson also connected with her doctor, Michael Atkins, M.D., over their shared interest in art and photography.

Atkins’ creative, indefatigable approach to his work resonated with Aronson. “It just reminds you that an environment like Georgetown is a petri dish of learning and innovation and imagination,” Aronson says. “Not only does it reflect the caliber of talent that Georgetown attracts, but it reminds you that beyond treating the body, there’s a show of dignity.”

After her remission, Aronson began thinking of a lifelong goal: climbing up Mt. Kilimanjaro. It was a goal that suddenly went from dream to reality when a friend called, wanting to know if she was interested in climbing with an all-female team she was putting together.

Aronson agreed to join the group, and on top of that, she decided to use her climbing campaign as a way to crowdfund Georgetown Lombardi’s artist-in-residency, in honor of how the program contributed to her continued healing.

“Having cancer during the pandemic, there was so much uncertainty, so much mental paralysis, spiritual paralysis. What better way to galvanize, inspire, and lead by example?” She hoped to add more art to the center, and show support to others going through the same difficult experience she went through.

WINTER 2023 15

Philanthropist and cancer survivor Ami Aronson (facing) collaborated with artist Aida Murad on this piece.

“Beyond adding art to the walls, I’m excited about giving this deep sense of belonging,” says Aronson. “Any cancer patient and I understand that need, and 18,000 cancer patients come through those doors every year. Imagine if the art could be an embrace, a welcome, a comfort, a feeling of belonging and also unity, because Aida’s work isn’t just one piece of art. It’s a companion series, and a reminder that as we go through cancer, it’s very personal, yet we’re not alone.”

Aronson is pleased to contribute to the atmosphere of healing at Georgetown Lombardi. She had years of experience in donor giving, and had met Murad and seen her work. The idea of the Georgetown Lombardi Artistin-Residency with Murad eventually fell into place.

“Art is really important to me,” Aronson says. “As we navigate our way through a curious, complicated world with so much uncertainty, it’s nice to feel like we belong somewhere and Georgetown Lombardi is a place where everyone belongs.”

Thanks to exponential support, the climbing campaign raised over $100,000, more than five times the original goal. “I had never felt more loved in my entire life,” Aronson says,

and it served as a reminder that “sometimes the most painful things can be the most purposeful things.”

“To me, this art is a single exhibit, but may it elevate the best practice of what it means to integrate art and science. There may be no perfect way to measure the impact, but I hope it gives cancer patients hope, inspiration, and a deep sense of calm for those moments of quiet reflection.”

Aronson also hopes the residency and climbing campaign will inspire others to support the center.

“This is an invitation to join us in integrating the arts in supporting and celebrating all that Georgetown has to offer. I can't say enough good things about Georgetown, and I plan to spend the rest of my life supporting this program.”

Murad is also focused on offering support through her art. She recognizes that there’s a lot of things to balance when creating art for people who are in such a vulnerable place. “You want to create art that helps people feel safe, courageous, hopeful, but calm at the same time. This has been such a humbling project.” n

Jane Varner Malhotra contribued to this article.

16 Georgetown Health

Photos: Lisa Helfert

“Each painting represents a different intention, from the lightness of the sun to the struggle of climbing a mountain.” –Aida Murad

Georgetown study demonstrates importance of visual intelligence in health care

Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) students were trying to determine if a shark attack victim would survive.

They weren’t huddled around a hospital bed, however: they were at the National Gallery of Art, looking at Watson and The Shark, a 1778 oil painting by John Singleton Copley.

Students visited the gallery as part of a visual intelligence study, led by Peggy Slota, DNP, R.N., FAAN, director of Doctor of Nursing Practice Graduate Studies at the School of Nursing. The study, published in July–August 2022 edi tion of the Journal of Professional Nursing, examines the impact of art observation and visual thinking strategies as a way to develop perception and critical thinking in patient assessment. Other Georgetown faculty contributors to the two studies include Maureen McLaughlin, Sarah Vittone, Julia Langley, and Nancy Crowell, and the team collaborated with National Gallery of Art educator Lorena Bradford.

Slota was inspired by book club guest lecturer Amy Herman, author of Visual Intelligence: Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life

The study had two goals: for students to observe, and for them to be able to describe what they’re perceiving.

“In the beginning, some students are thinking, ‘Why are we going to an art gallery when we’re in nursing graduate school?’ Afterwards, they see that this whole experience really opened their eyes,” Slota says.

“Communication is one of the leading root causes of med ical errors in health care,” Slota says. “It’s so important to be able to describe exactly what you see and not miss any nuances. This is a different way of helping students see more details and be able to communicate them in very descriptive language.”

One part of the research study included assessing photo graphs of patients and describing illnesses they observe. Another has students working with partners to draw a portrait. The catch: one student had to draw the paint ing without sight, only directed by their partner’s verbal description.

“The students realized that how you describe what you’re seeing really makes a difference to the other person who’s hearing it,” Slota says. “They’re understanding what’s present. For example, they’ll forget to mention that something’s in the foreground. Or they’ll fail to describe the shape. And this is really applicable to patient assess ment, because you often are describing what you’re see ing in a patient to someone who hasn’t seen the patient.”

Photo: Peggy Slota

By Karen Doss Bowman | Design by Shikha Savdas

18 Georgetown Health

Photo: Rafael Suanes

WINTER 2023 19

Photos: iStock

For Ruba Omeira (M’24), a single grain of rice illustrates the staggering consequences of climate change.

During a biology course Omeira took as a pre requisite for medical school, the professor discussed the impact of climate change on rice crops. The Earth’s rising levels of carbon dioxide are gradually altering the biochemical composition of rice, increasing its carbohydrate content and eliminating essential nutrients— particularly protein. With more than two billion people worldwide relying on rice as their main food source, this can cause a dramatic increase in nutrition-related diseases.

“Before that classroom session, I didn’t realize that a macro problem like climate change could be diluted down to one particular food that can affect so many people’s protein intake and ultimately result in

medical problems,” Omeira says. “It was so interesting that I wanted to learn more about these issues. It was really eyeopening for me to learn how the environment’s health trickles down to people’s nutrition and medical care.”

Climate change has the potential to affect every organ system within the human body, as well as mental health. That means health care providers increasingly encounter patients affected by environmental factors. And yet, this broad topic rarely is woven into preclinical curricula at medical schools.

Omeira and Vasalya Panchumarthi (M’24) wanted to change that at Georgetown. Their vision resulted in the School of Medicine’s new Environmental Health and Medicine longitudinal academic track, which allows medical students to receive additional training to address these issues. Those admitted to the track learn how to take patient histories that include environmental factors affecting health, educate patients about environmental risks, advocate for patients affected by climate change, and explore strategies for reducing the environmental impact of medical facilities.

“For the most part, medical students and professors understand that environmental health is an important topic, but we get so busy in training that it’s not active on our minds,” says Panchumarthi. “But as we recognize more and more health impacts of climate change, we see that it really needs to be integrated within the medical school curriculum.”

20 Georgetown Health

“It was really eyeopening for me to learn how the environment’s health trickles down to people’s nutrition and medical care.”

—Ruba Omeira (M’24)

Omeira and Panchumarthi

Photos: Courtesy of Ruba Omeira and Vasalya Panchumarthi / iStock

The biggest threat to humanity

Climate change is the “single biggest threat to humanity,” according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The global crisis affects every factor necessary for sustaining life: clean air, safe drinking water, food supply, and safe shelter. WHO estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change-related health problems— such as malnutrition, malaria, and heat stress—will cause about 250,000 additional deaths per year.

Given these projections, training future health care providers to recognize the connections between health and climate change is essential. In June 2019, the American Medical Association (AMA) announced a new policy advocating for the integration of climate health topics into medical education curricula. Georgetown is a member of the Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education, launched at Columbia University in 2017 “to unite health pro fessional training institutions, health societies, and regional health organizations to create a global climate-ready health sector.”

Despite the urging of numerous health care asso ciations like the AMA and intergovernmental agencies such as the United Nations, “medical school curricula have not kept pace with this urgent need for targeted training,” according to an article co-authored by Caroline Wellbery, M.D., Ph.D., adjunct professor in the department of family medicine. The 2018 manuscript, “It’s Time for Medical Schools to Introduce Climate Change Into Their Curricula,” was published in Academic Medicine, the journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“Taking the broad view, everything is health,” says Wellbery, whose interests include preparing future health professionals to advance climate change solutions through patient education and advocacy, as well as developing sustainable practices in the health care sector. “For a long time, there was little interest in or awareness of these issues. Now, there’s this momentum because it’s generally accepted that climate change is real, and that climate change is dangerous. People understand that it threatens the health of future generations and of the planet.”

Enriching the academic experience

With the addition of the Environmental Health and Medicine longitudinal academic track—which wel comed the inaugural cohort in Fall 2021—Georgetown School of Medicine now offers nine of these facultyrun, scholarly experiences. Other track topics are Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Medicine; Health

ALUMNI IN THE FIELD

Instilling hope for action through pediatric care

Samantha Ahdoot, M.D. (M’99), has a special inter est in the environmental effects of health in children. Joining the Pediatric Asso ciates of Alexandria in 2003, Ahdoot is a Board Member of the Virginia chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) where she serves as Environmental Health Champion. She is lead author of the AAP Policy Statement and Techni cal Report on Climate Change and Children’s Health.

Her work at the state level to influence key poli cies has helped position Virginia as a national leader in clean energy policy. Ahdoot is chair of the Virginia Clinicians for Climate Action (VCCA), an organization that strives to bring the clinician voice to climate change advocacy in the state. Through education, advocacy, and community outreach, the VCCA has built a network of over 450 clinician advocates for local and statewide climate change solutions that protect the health of patients and communities across Virginia.

Ahdoot says she always wanted to work with children, recalling a memory from her childhood when she told her parents at a tender age that she wanted to be a “baby doctor.”

“I took a lot of detours along the way, pursuing other interests, but I ultimately came back to my expressed interest as a five-year-old,” she recalls.

One of her detours was becoming a serious trumpet player. She notes that music was instru mental to her studies while in medical school.

“I played in the Georgetown undergraduate orchestra and the Georgetown Jazz Ensemble, and I loved those experiences,” she said with a smile.

Ahdoot’s connection to Georgetown goes beyond her medical studies and trumpet-playing. It is the place she met her husband Kenneth Ahdoot, M.D. (G’95, M’99), a practicing obstetrician, in her micro biology class.

WINTER 2023 21

continued

on next page

Photo: Courtesy of Samantha Adhoot

“The pediatrician-obstetrician partnership works,” she laughs. “He delivers the babies and then passes them to me.”

Ahdoot notes that physicians generally do not receive much training on environmental health when studying traditional medicine.

“Freedom from exposure to toxic materials is vitally important to the health of every child,” says Ahdoot. “As threats to the environment become more pervasive, physicians are increasingly realiz ing that changes in the environment are affecting the health of our patients in very real ways.”

Environmental conditions like air pollution, for example, cause lung growth to diminish in children, Ahdoot explains. A champion in her field, she notes that pediatricians are leading the effort across the United States integrating environmental health into medical education.

While changes addressing the problem of envi ronmental degradation are incremental, building awareness has a significant impact.

“We’re in the midst of a tremendous, adolescent mental health crisis, which obviously has many roots and many complex causes,” she says. “As our adolescent patients learn about environmental health, they’re also watching how we respond. A lack of response generates a sense of helpless ness and betrayal.”

Ahdoot notes that her focus as a pediatrician is to give young adults opportunities to help make things better. It is an approach she references as “active hope,” her guiding principle extracted from the book Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy by Chris Johnstone and Joanna Macy.

“Active hope doesn’t require optimism,” she states. “It just requires recognizing a problem, finding a path forward that can help address that problem, and then taking action to make advancements towards that goal.”

Ahdoot states that the School of Medicine’s newly established Environmental Health and Medicine Track is a prime example of young adults with active hope.

“The students see a problem, and they’ve devel oped a path that through their own particular circu m stance can make things better.”

—Bhriana

Smith

Justice Scholar; Health Care Leadership; Literature and Medicine; Medical Education Research Scholar; Population Health Scholar; Primary Care Leadership; and Spirituality in Medicine.

The longitudinal academic tracks reinforce attitudes and skills for self-directed lifelong learning and career development. The programs strive to promote intel lectual curiosity, appreciation of scholarly inquiry, interprofessional collaboration, and cura personalis

The tracks are optional, and interested students may apply during their first year of medical school. Those who successfully complete all track require ments and maintain good academic standing graduate with distinction.

“The tracks introduce some individualization to the medical school experience,” says Mary Furlong, M.D. (G’91, M’95, R’00, Parent’21, ’25), senior associate dean of curriculum and director of the Office of Medical Education. “Students are choosing to dive deeply into topics they feel passionate about, meet people in the field, and potentially carry that knowledge and experience into their residencies, or into whatever specialties they end up choosing.”

in the Field continued 22 Georgetown Health

Alumni

From club to curriculum

Georgetown medical students are passionate about understanding the connections between environmental conditions and human health. Throughout their lives, this generation of students has been exposed to widespread media coverage and public debates about the causes and adverse impacts of climate change. Most take seriously their personal roles in mitigating environmental harms.

In 2019, Aditi Gadre (G’18, M’24) worked closely with Wellbery to establish the Georgetown Climate Health and Medical Sustainability Club (CHMS). This club helped lay the groundwork for the longitudinal track. The organization’s members had ambitious goals: they not only wanted to influence curriculum changes, but also were interested in forming community partnerships and building advocacy networks. Realizing that was a lot to take on at once, Gadre says the group decided to focus on integrating climate and health topics into the pre-clinical curriculum.

“As we become more knowledgeable about the impact of environmental changes on human health, we can not only communicate about them to our patients, but also advocate within our hospital systems, which contribute to carbon emissions,” says Gadre, the CHMS founding president.

“These are things we can directly ameliorate. The growing body of research helps us understand the intricacies between climate change and human health. Educating students is such a big part of the process of chipping away at this problem that’s been so persistent.”

CHMS members developed around 30 slides that have been used by Georgetown School of Medicine professors. These materials cover a wide range of topics, including pharmaceuticals and the environment, the impact of wildfires on asthma and other respiratory conditions, and the role of rising temperatures on the cardiovascular system.

“We found that faculty members can be amazing climate champions,” says Gadre, who is completing the Health Justice Scholar longitudinal academic track. “They really care about these issues, but it’s not something that most of them were taught during their training. It’s been helpful to have that co-development and co-creation aspect within the curriculum. This has been a life-changing aspect of my education.”

The work of CHMS has expanded in recent months. Wellbery currently is working with the group on another project: creating patient-friendly brochures about environ mental health to distribute to primary care offices.

“The growing body of research helps us understand the intricacies between climate change and human health. Educating students is such a big part of the process of chipping away at this problem that’s been so persistent.”

WINTER 2023 23

—Aditi Gadre (G’18, M’24)

Photo: iStock

‘Absolutely no one should die of asthma’

Many people with treat able health conditions end up in the emergency room because they lack access to primary care and cut ting-edge medications, says pediatric pulmonol ogist LeRoy Graham, M.D. (M’79, Parent’04). He often describes this situation to explain the drag health disparities can create on the entire health system.

In addition to serving in leadership positions for medical boards, Graham has dedicated his career to providing good health care and health awareness to young children and their families.

After completing his fellowship in pediatric pul monary and critical care, Graham began serving in the military—a career that included being a bri gade surgeon with the First Infantry Division during Operation Desert Storm in 1990. After retiring from the military, Graham went into private practice as a pulmonary specialist in Atlanta, Georgia. He recalls spending a lot of time with children with asthma, which piqued his interest in environmental impacts.

“Many of my minority patients lived in substan dard housing in urban environments, clustered around central traffic quarters, where auto pollu tion was a big factor,” he says. He sought to increase his patients’ awareness of environmental health and help them advocate for change.

Graham founded a nonprofit, Not One More Life, where he utilizes community strength by partnering volunteer medical providers with faith-based orga nizations to educate and empower particularly poor minorities. Many of the churches have health minis ters, who often bring a professional background in health work to the role, offering a powerful bridge for communication, information, and care.

“We try to inculcate in patients a sense of aware ness and control, so that they can become knowl

edgeable and feel empowered to make changes beyond just the medicines,” notes Graham.

The nonprofit has been particularly successful in Black communities. Most notably, Graham found that working with faith communities and other pro active community organizations drew a high rate of people coming out to be tested. They wanted to learn how to self-manage respiratory diseases.

“I began to appreciate shining a light on the envi ronmental impact of social injustice,” says Graham.

He and a team of scholars conducted a study on asthma hospitalizations in Atlanta’s Grady Hospi tal, before, during, and after the 1996 Olympics. He noted that during that event, city leaders were suc cessful in getting most people in the area to stop driving and to use public transportation. As a result, the city saw some of the lowest levels of transpor tation-related pollutants in its history. He noted there was a dramatic decrease in both emergency room visits and hospitalizations for asthma, partic ularly among children.

“The study made me realize that particularly minorities and poor urban dwellers tend to be clustered around central transit corridors,” notes Graham. “They are disproportionately impacted by auto pollutants.”

Graham has testified before a congressional sub committee on transportation, elucidating the health impacts of the environments where poor people and minorities live.

“We’re affected by different types of pollution and violence—as well as stress related to these things,” he notes. “Just the stress of living in a violent neigh borhood, of having to rely on public resources for transportation, and the unpredictability of these factors feed into an accentuation, if you will, of the fight-or-flight mechanism in our body.”

Graham has since retired from his practice, and lives in Florida with his wife.

—Bhriana Smith

24 Georgetown Health

ALUMNI IN THE FIELD

Photo: Courtesy of LeRoy Graham

These pieces will provide basic information on the potential harms of climate change and ways to improve one’s health.

“We’ll study to what extent these brochures have an impact on a patient’s interest and awareness, to help create a link between the health care office and the public,” Wellbery explains. “That helps us determine whether or not the health care office is a good place to disseminate climate information to patients in a way that is accepted and relevant.”

To better serve patients

Before they envisioned and proposed the new longitudinal academic track, Omeira and Panchumarthi served in CHMS leadership positions, carrying the torch Gadre ignited. Both created slideshow presentations. Omeira, for example, was inspired by the rice grain lesson to develop slides on the dietary implications of rising CO2 levels.

Wanting to create something more permanent, Omeira and Panchumarthi wrote a proposal for the Environmental Health and Medicine track, recruited a faculty director, and presented the concept to four committees. Just weeks before the deadline for students to apply to join tracks, their idea was approved.

“We were really passionate about this track,” Panchumarthi says. “I don’t know how we did it within such an ambitious timeframe. Ruba and I made a really good team, and we kept each other going. Everyone we presented the proposal to was

very supportive. They wanted this track as much as we did because they recognized the importance of climate health.”

The track has featured lectures and workshops on envi ronmental history taking, the environment’s impact on rheumatoid arthritis, environmental injustices, pharmaceuticals and the environment, and the effects of wildfire on respiratory health. Advocacy and action are also key components of the track, with opportunities for students to learn how to write op-eds and how to lobby. During their fourth year, students in the track must complete a capstone project, such as a case study or a public awareness campaign.

The selection of speakers and topics are driven by student interest, allowing them to explore issues that may impact their future practices, says track director Shiloh Jones, Ph.D., associate professor and director of medical gross anatomy. In the long run, that will help them better serve their patients.

“It’s apparent that there are changes happening to the climate,” says Jones. “Temperatures are increasing, and that’s having impacts that weren’t even considered decades ago. It’s getting warm in places that weren’t warm before, and that’s bringing diseases to new areas. We’re finding new pathogens in places where they never existed. Droughts and bizarre weather patterns are impacting people’s health. Climate change in general is such a polarized topic, and there’s some data suggesting people are more likely to trust their physicians on the issue.”

Changing the practice of medicine

Today’s medical students not only will serve on the front lines of caring for patients affected by climate change—they also will be called upon to create solutions to medicine’s sustainability problems. The U.S. health care sector contributes an estimated 8.5 percent of carbon emissions through energy use, toxic chemicals, and waste. And according to a report by the nonprofit Health Care Without Harm, “The global health care climate footprint is equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 514 coal-fired power plants.”

Future health care workers must be prepared to take action on decarbonization—from devising new methods to manage the health care supply chain to prescribing more environ mentally friendly asthma inhalers. By exposing medical students to the full spectrum of climate change impacts, Georgetown is preparing them to mitigate climate change.

“The Environmental Health track, as well as CHMS, tries to strike a balance to make sure all medical students get a good dose of consistent information that’s up-to-date and relevant,” Omeira says. “We all will eventually become doctors and hopefully, we’ll integrate this knowledge into our clinical practices every time we see a patient. Climate and environmental health will change the way we practice medicine—it’s inevitable.” n

WINTER 2023 25

“We all will eventually become doctors and hopefully, we’ll integrate this knowledge into our clinical practices every time we see a patient.”

Photo: iStock

—Ruba Omeira (M’24)

By Michael Simms Jr. (G’19, ’24) | Design By Wanda Felsenhardt

As the world continues to steadily emerge (and gather the pieces, as it were) from the numerous stages of the global pandemic, we would be remiss to go without acknowledging June 22, 2020: the 100 -year anniversary of Dr. Edmund Pellegrino’s birth.

26 Georgetown Health

Photo: Courtesy of Michael Simms Jr.

The author smiles with Dr. Pellegrino in 2013.

STUDENT POINT OF VIEW

Dr. Pellegrino—after whom Georgetown’s Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics is named—enjoyed an illustrious, legendary career as a physician and administrator. He passed away in 2013, having served Georgetown in a number of leadership positions over several decades, including his latest post as Professor Emeritus of Medicine and Medical Ethics. Through his numerous books, articles, and academic papers on topics ranging from bioethics to the physician-patient encounter, and his indispensable faith in Jesus Christ and the Catholic Church, he has offered messages that still challenge and animate the medical community, specifically concerning the telos of medicine.

Though the Greek word telos is employed in philos ophy to signify an end (or an ultimate aim), my begin nings with Dr. Pellegrino came by way of another physician and mentor: Dr. Leonard Morse, himself a living icon in the fields of public health and epide miology. I met Dr. Morse during my undergraduate experience at the College of the Holy Cross, and he encouraged me to make contact with his friend and colleague at Georgetown.

I first visited Dr. Pellegrino’s office at the Kennedy Institute of Ethics in Spring 2011. He had just arrived back from teaching an ethics class to a group of under graduate students. I held a half-read biography of Albert Schweitzer, and conflicting notions about my experience as a double major in the humanities (clas sics and music), my challenges with pre-med classes, and my desire to better ascertain the nature of the medical profession.

Dr. Pellegrino kindly and boldly engaged with my reflections, with the curiosity of a new acquaintance and the familiarity of an old friend. Over the next two years, I would make visits to his office (announced and unannounced), where “gratitude” and “amaze ment” hardly express my surprise at finding him, over and again, willing to entertain my queries and support my journey to study health and medicine. I would join him at the hospital’s Bioethics Clinic, and I was heartened to receive his encouragement concerning my interest in the well-being and equitable treatment of older adults.

In the years since Dr. Pellegrino’s passing, espe cially as I wrestled with key issues surrounding the philosophy of medicine and health care economics for

the M.S. in Aging and Health at Georgetown I com pleted in 2019, I have engaged in a kind of conversa tion with him through his written works. Especially as recent trends in bioethics scholarship have shifted towards virtue ethics, I have found Dr. Pellegrino’s writings on the topic to be no less fresh and rewarding.

Dr. Pellegrino has centered the physician profes sional ethic on the physician-patient encounter, as all of health care is to build from it. With this as the end (i.e., the telos , the purpose), economic considerations in themselves are means, which render the managed care ideology and its myriad manifestations especially worrisome.

Of particular note are Dr. Pellegrino’s concerns about what are now generations of young physicians being fed a social construct where numerous nondollar costs profoundly affect the quality and satisfac tion of the “care” provided. How sobering is his obser vation that the carefully constructed patient history and physical examination have become a scarce commodity!

From Dr. Pellegrino we can therefore receive a cautious reminder that what we as a people consider “worthwhile” speaks to the sort of people we desire to be.

In having the opportunity to celebrate Dr. Pellegri no’s life and legacy, together with having experienced a recent global health crisis which served to further indicate and amplify these concerns, may we find hope in pursuing the telos, and in such a pursuit, to better discover the good. n

Michael A. Simms Jr. is currently pursuing a Master of Science in Clinical and Translational Research—with a concentration in Health Disparities and Community Engagement—at the GeorgetownHoward Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (GHUCCTS). He also completed a Master of Science in Aging and Health at Georgetown in 2019.

His interest in finding sustainable solutions to the immi nent demographic shift to an aging population has him delving into various, seemingly disparate topics, ranging from social cohesion and the political “culture of contempt” to health care financing and the Danish concept of hygge.

WINTER 2023 27

Gift supports child, adolescent, and family mental health

By Kate Colwell

The J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott (JWASM) Foundation has pledged $3 million to establish the Marriott Endowed Chair in Child, Adolescent, and Family Mental Health, the first endowed chair in the Department of Psychiatry and the latest in a long line of investments by the JWASM Foundation in Georgetown University and MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in support of childhood mental wellness.

The inaugural Marriott Chair is Matthew Biel, M.D., M.S., whose work addresses the impact of adversity and stress upon under served children and families, reduces health disparities, improves access to mental health care, and develops clinical interventions.

Biel and his team seek to holistically understand and support children in the context of their families. The Marriott Chair provides an infrastructure for Biel and his teammates to create a future center focused on improving mental health for children and families—and in doing so, transform communities.

“Mentally healthy kids are the cornerstone of a healthy society,” Biel says. “Brain development is so profound and significant in early childhood. When we create environments that promote healthy relationships and healthy brains, our children will be in a much better position to flourish throughout their lives.”

The future center will provide an umbrella structure for expanded clinical programs for children, adolescents, young adults, and their parents and families, as well as research and scholarship, educational and training, and community engagement and advocacy.

The JWASM Foundation has a long history of supporting MedStar Georgetown University Hospital through the Medical/Surgical Pavilion and grants to the Early Childhood Innovation Network (ECIN), which

Biel co-directs with Lee Ann Savio Beers, M.D., of Children’s National Hospital. ECIN is a citywide collaborative of health and education providers, community-based organizations, researchers, and advocates in Washington, D.C., that has brought clinical services, parenting classes, and mental health resources to more than 6,000 families.

Through the Marriott Chair, Biel can recruit promising scholars in child and family mental health to the Georgetown faculty, acquire new tools to improve patient experience, develop clinical programs for caregivers and young children, expand the size of translational research efforts to support family mental health, and deepen trusting relationships with community partners. ECIN prioritizes collaboration with local partner organizations that have community expertise.

“As a funder, it is critical that we ask and listen to those in the community about what they need as opposed to entering any environment assuming our answers are the right ones,” says Mieka Wick, executive director of The JWASM Foundation. “Dr. Biel’s leadership at ECIN has always put the community and its constituents at the center.” n

28 Georgetown Health Photo: iStock

ON CAMPUS

Georgetown’s research earns “gold standard” classification

By Gabrielle Barone

An R1 Carnegie Research Classification, given out every three years by the Carnegie Classifications of Institutions of Higher Education, isn’t easy to earn. Universities must score highly in a research index, spend at least $5 million on research, and award 20 research opportunities per year. In 2021, Georgetown received its ninth R1 designation, putting it on an ever-narrowing list of schools.

“The R1 classification is really the gold standard for a research university,” says Anna Riegel, Ph.D., interim vice president for biomedical research and education. Out of the 3,900 institutions included in the 2021 update, only 137 schools—3% of the total—attained R1 status. The Medical Center contributes 70% of the research dollars at Georgetown University overall. “We are proud of the pivotal role the Medical Center plays in maintaining R1 status,” Riegel says.

Caleb McKinney, who co-leads the cross-campus Georgetown University Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (IMSD) training program, believes that Georgetown’s size allows researchers to collaborate more. “The wave of the future, with the cross-pollination of ideas across disciplines, is really driving our ability to solve the world’s most complex biomedical and health-related problems,” McKinney adds.

Georgetown’s scientific graduate programs feature incoming cohorts focused on a variety of topics, and university research has been awarded multiple T32 training grants for projects across biology, pharmacology, chemistry, physics, biochemistry, neuroscience, and tumor biology. Riegel believes a thriving campus environment with varied research can lead to continued educational expansion.

“No research can exist in a vacuum,” Riegel says. “Graduate students and postdoctoral fellows are the foundation of our research at the Medical Center. The best thing for them is to be in a challenging but nurturing environment. The more you foster that atmosphere, the more excellent people it will attract.” n

Required summer reading for med students