Migraine solutions for women

n n A third of the nearly 20 million women who participated in a national health survey reported migraines during menstruation, and of them, 11.8 million, or 52.5%, were premenopausal. The analysis was conducted by researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center and Pfizer, Inc., which makes a migraine medication.

“The first step in helping a woman with menstrual migraine is making a diagnosis; the second part is prescribing a treatment; and the third part is finding treatments patients are satisfied with and remain on to reduce disability and improve quality of life,” says the study author, Jessica Ailani, professor of clinical neurology at Georgetown University School of Medicine and director of the MedStar Georgetown Headache Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital.

“As a headache specialist in the U.S., I know I can do better for women in my clinic, but what can be done for the millions of women who don’t get into a headache clinic? That is our true next step,” says Ailani. “If you have migraines related to your menstrual cycle, discuss this with your gynecologist or neurologist. There are treatments that can help, and if the first treatment tried does not work, do not give up.” n

To date Georgetown’s program has supported over 800 Haitians living with HIV.

Photo: xxxxx

By Jane Varner Malhotra | Design By Sofia Velasquez

In July 2024, Georgetown welcomed Norman J. Beauchamp Jr. as the new executive vice president for health sciences at the Georgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) and executive dean of the School of Medicine. In addition to the medical school, GUMC includes the School of Health, School of Nursing, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Biomedical Graduate Education, and an extensive research portfolio. He also shepherds Georgetown’s academic health system partnership with MedStar Health. Beauchamp replaces Edward B. Healton, who concluded nine years of service in June.

A neurointerventional radiologist with an interdisciplinary background who specializes in stroke diagnosis and treatment, Beauchamp brings his clinical, educational, and research experience combined with extensive work leading major academic health systems. He has served as a department chair, medical school dean, president of a practice plan, executive vice president of health sciences, medical director of a free clinic, and chair of a university faculty senate.

Caring for others

Growing up on his family’s farm and observing his mother’s career in community health led him to follow a calling in values-based medical leadership.

“Until I was seven, we lived in a suburb of Boston,” Beauchamp recalls. “Then my parents decided to raise my brother and sisters and me on a farm,

to further our work ethic and values. We moved to St. Johns, Michigan—my father’s home state—to a farm with 30 acres, 200 chickens, 20 cows, and four horses. And my parents said, ‘We’re going to work, and you all are raising cows, horses, and chickens.’” Beauchamp is grateful for all he learned in that environment and the sacrifices his parents made for their children.

“I so appreciate my parents. My dad worked in aerospace and retooled to work for the state of Michigan. My mom was a community mental health worker.” Beauchamp would go to work with his mother, often witnessing people suffering. When you see people struggling, his mother insisted, it’s important to do something about it.

“And that’s what led me to want to go into medicine.”

Innovation at the intersection of disciplines Beauchamp studied biology at Michigan State University. His decision to remain there for medical school was guided by a conversation with his philosophy teacher, E. James Potchen.

“He asked if I wanted to see what he did when he wasn’t teaching philosophy. He was a lawyer, horticulturist, philosophy teacher, economics teacher, family medicine doctor, and the chair of radiology—an inspirational Renaissance person. His passion for learning was only exceeded by his dedication to teaching others,” Beauchamp recalls. Potchen committed to helping him get a

scholarship for medical school at Michigan State “if I promised that half of what I read, for the rest of my career, would be from outside of medicine.”

Since that time, Beauchamp has been especially drawn to the intersection of disciplines, because he believes that is where advances in medicine take place. During his career, for example, he has served as a principal scientist of applied physics, and a professor of industrial engineering, neurosurgery, neurology, and neuro-radiology.

“I realized that by learning about these different disciplines, I’d be best prepared to make a difference.”

Expanding the window for stroke treatment

After medical school, he continued on to Johns Hopkins University for his residency in radiology. Seeking to find ways to lessen the impact of diseases of the brain, he did a fellowship in neuro-radiology. During his fellowship, Beauchamp determined that he would focus his work on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. “Strokes can take away a person’s ability to interact with their loved ones and the world in an instant, and I wanted to help make better outcomes possible.”

The mandate for just care, to bring hope and healing to all, expanded my focus to transforming health and health care delivery.

Following his fellowship, he joined the faculty at Johns Hopkins. “We quickly established a highly collaborative, interdisciplinary team: physiologists, physicists, linguists, neuroradiologists, and neurologists.”

Their goal was to discover and implement ways that would make it possible for more of the people stricken with an acute ischemic stroke to be treated safely. Specifically, the goal in treating an ischemic stroke is to return blood flow to the brain as quickly as possible. “It used to be that in order to safely remove the obstruction, guidelines mandated that treatment had to be initiated within three hours from the time the stroke occurred. However, it is very difficult for patients stricken with a stroke to recognize what has occurred to them, and then to get from home to the hospital, be evaluated, diagnosed, and treated in three hours. That happens for only about 4% of stroke patients. We recognized that in helping to invent a new way to image the human brain, we could extend that out to six hours or 12. That was our work.”

He pursued a second fellowship in neurointervention, seeking the opportunity to further improve stroke outcomes. “With the new diagnostic methods in hand, I wanted to now help develop and deliver the indicated treatments. Using intravenous r-TPA to retrieve or dissolve clots via catheters placed directly into the arteries of the brain, we sought ways to optimize the devices and techniques.”

Beauchamp then expanded his work to look at systems of care. “As we began to provide care that led to better outcomes for those who could access our care at Johns Hopkins, our attention appropriately extended to those that could not access our care. The mandate for just care, to bring hope and healing to all, expanded my focus to transforming health and health care delivery.“

Receiving a grant to attend Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, he obtained additional training. Beauchamp used statistical methods to drive improvements at Johns Hopkins, including expanding access to care, removing inefficiencies

Photo: Art Pittman

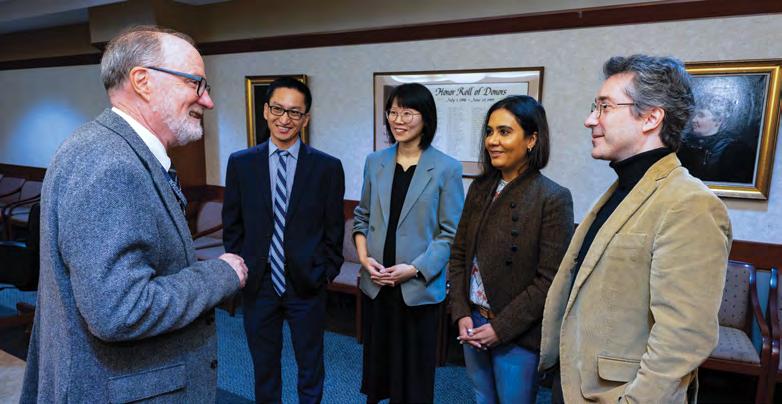

Beauchamp spent his first months on a listening tour, meeting here with Dan Merenstein, M.D., professor of family medicine in the School of Medicine and professor of human science in the School of Health.

and waste, and lowering health care costs. He emphasized a “culture of caring built on a foundation of trust” that, when combined with quantitative approaches, empowers care team members, patients, and families. The work earned him a role as the vice chair of clinical operations in 1999.

Deepening care and widening the reach

In 2002 he moved to Seattle to join the University of Washington as department chair in radiology. It was a large department serving five hospitals. He also had the opportunity to serve as president of the University of Washington Clinician Practice. “One of the things that brought me to the University of Washington was that they were the only medical school for five states, so they had an incredible reach. In serving a department and across the practice, we could integrate discovery, education, and clinical care across all the areas of medicine and bring patient- and family-centric care to a vast number of people.”

He also saw a need for more connection between the medical school and the rest of the university. Discovery, teaching, and bringing healing and health to all requires insights and effort from every college in a university, notes Beauchamp, from the arts to social sciences to policy, basic sciences to agriculture, psychology, economics, built environment, and industrial engineering. Participating in shared governance enabled forming necessary collaborations. As vice chair and then chair of

the faculty senate, he helped lead a number of initiatives that brought the university together, including securing a $210 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to create an Institute for Population Health.

Beauchamp also sought opportunities to contribute through volunteerism. He helped launch and served as founding medical director for a free clinic. “The homeless, the underinsured, and the uninsured population is so underserved. A group of us came together to help lessen their struggle. We got permission to use a professional basketball arena for six days so we could establish a clinic with tremendous capacity.” They enlisted 100 dentists and set up 100 dental chairs, brought in hundreds of interprofessionals to deliver medical care and social services, and provided free items including socks, shoes, and eyeglasses.

“Importantly, our efforts were guided by listening to and learning from those we served. We focused on people feeling supported from the moment they arrived on site to recommendations for follow-on care. Our providers were from every profession. We had translators, social workers, support animals, and dedicated volunteers from the community. We treated 4,000 people in four days and then we asked our patients: ‘How did we do? Did you feel cared for?’ 97% said they did. Health care, done correctly, is about all people feeling cared about and not feeling alone.” The successful Seattle/King County Clinic continues to this day.

During Medical School Reunion in October, Beauchamp engaged with alumni about advancing medicine at Georgetown.

Returning to give back

Beauchamp returned to Michigan State in 2016 as dean of the College of Human Medicine, in part to fulfill a promise to his mother to help make health care better in Michigan. He also wanted to give back to his alma mater. He focused on growing the school’s human health research, expanding the clinical practice, and driving health care innovation.

He also led the effort to address structural and reporting issues in the university’s medical system, eventually creating and leading the Office of Health Sciences, which includes the university’s clinical practice, College of Osteopathic Medicine, College of Allopathic Medicine and Public Health, and the College of Nursing. The efforts in restructuring were urgently called for in response to an ex-physician who, for at least 14 years of his career as the team doctor for the USA Gymnastics and an osteopathic physician at Michigan State University, abused children and young adult athletes. The failures that allowed a predator to persist were structural and cultural, notes Beauchamp, therefore restructuring, addressing issues of power, being trauma-informed, establishing

chaperone and reporting policies, and empowering all voices was imperative. A culture of caring and healing drove the work enabling institutional transformation.

During his tenure there, Beauchamp also served as coarchitect alongside leaders at Henry Ford Health in establishing a 30-year partnership between MSU Health Sciences and Henry Ford Health. The venture included a $2.5-billion-dollar initiative in Detroit for a new academic medical center, a research building that will focus on health disparities, a neurofibromatosis institute, and affordable housing in partnership with the Detroit Pistons. In addition, he led the establishment of a 675,000-square-foot health innovation hub in Grand Rapids to advance human health research and innovation, and to diversify sources of funding. MSU was also the first responder to the Flint Water Crisis, Beauchamp notes, working with the community to provide resources and programs in health.

Listening and envisioning with Georgetown Beauchamp and his wife, Kristina, approach their lives with mission in mind. For both of them, coming to Georgetown and the nation’s capital felt like the right next step.

Photo: Lisa Helfert

Beauchamp visited with volunteers at the student-run HOYA Clinic including Eileen Moore, M.D., associate professor and assistant dean for community education and advocacy and one of the clinic’s medical directors.

“We talked together about how we take what we did at a state level and try to bring it to the nation and the world,” he says. “Being in the nation’s capital enables connections and partnerships to individuals and institutions dedicated to improving the human condition.”

His faith also attracted him to the country’s oldest Catholic university, founded on Jesuit principles including expanding the common good, being people for others, and cura personalis, or caring for the whole person. “Health care and faith are about people feeling cared for, people not feeling alone in their time of need. The opportunity to align those efforts is powerful.”

During his first months at Georgetown, Beauchamp set up a listening tour around the Medical Center and beyond, gathering a first sense of Georgetown’s strengths as well as opportunities to expand and deepen impact. His goal was to find areas that would bring together the strengths across the university in a way that could do the greatest good for the most people.

“I asked how we are creating opportunities for students to learn and be involved in discovery such that they can realize the goals that brought them to Georgetown. Similarly, I sought to discover how we empower and support the staff and faculty in their missions of impact. I also looked at what areas of focus would allow us to fully realize the potential of being an academic health system, possible because of the extraordinary 50-year partnership between Georgetown and MedStar, a world-class health system with over 400 sites of care delivery. Finally, I asked people to think about a great unmet need in our world and how we at Georgetown are best able to respond to that need: where we are passionate, where we can be preeminent, and how we can uniquely lessen the struggle of those we serve.”

Georgetown is a place with an unparalleled concentration of individuals and groups committed to helping others and with countless areas of excellence.

Excellence and caring for the common good

“Indeed, the listening tour confirmed that Georgetown is a place with an unparalleled concentration of individuals and groups committed to helping others and with countless areas of excellence,” Beauchamp shares.

He identified five areas of convergence: cancer, restoring brain function, health equity, global health, and the establishment of an innovation district.

“One area of growth for us is in human health research, specifically NIH-funded research. To bring health and healing to more people, we have to discover new ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease and to ensure our graduates are imbued with this knowledge. There is extraordinary work ongoing; the goal is to support and further expand those efforts.”

Cancer research and care excel at Georgetown, notes Beauchamp.

“Our work in oncology is really extraordinary. Recognized as an NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, Lombardi is a treasure. We have an opportunity to make advanced care and participation in clinical trials even more accessible to all. Fundamentally, we want to bring the very best in cancer care to where people live. The support of family and community is a key element in ‘caring for the whole person’ during cancer treatment.”

Another strength he’s identified is in his area of clinical expertise: stroke. He observed a tremendous expertise in the treatment of stroke and in rehabilitation care. Moreover, the depth and breadth of research in return of function is also unparalleled, he adds.

“Bringing together these strengths, along with those in basic science and neuroengineering, would allow us to create and deliver support to those stricken by stroke. Importantly, emphasizing return of function will also build on and support work being done in neurologic disorders and trauma.”

“After a stroke or after a significant trauma, there’s all this energy around the hospitalization. But when people go home, they wonder, ‘Where’s my support? How do I try to

Georgetown leaders including Beauchamp met Pope Francis on a visit to help support the Pope’s Global Alliance for the Health and Humanitarian Care of Children.

get function back?’ At Georgetown we have some of the best research in return of function that I’ve seen anywhere. How do we make the most of this?”

Global health is an enduring standout strength at Georgetown, notes Beauchamp, particularly its emphasis on building sustainability or capacity in country. His first months at Georgetown included an audience with Pope Francis in September, as part of an initiative with Georgetown’s Global Health Institute to support a worldwide network created by the Vatican that provides medical care to children and supports health care workers in the field.

Beauchamp will continue prioritizing health equity as a Georgetown value, addressing health disparities through overcoming barriers to health and expanding pathway programs, increasing community engagement, and promoting human dignity.

Opportunities ahead

As the academic health system partnership with MedStar Health enters its 25th year, Beauchamp plans to deepen the relationship. In 2017, Georgetown University and MedStar Health finalized new long-term agreements that span a 50-year

My overwhelming takeaway from the first 90 days is gratitude. People here are deeply committed and inspired. I am so blessed to be able to join this community.

term, reaffirming the joint commitment to the partnership. Another important area of focus for Beauchamp is the university’s expanding health and medical presence at the Capitol Campus downtown. Home to the Georgetown University Law Center and the McCourt School of Public Policy, the location offers health and medical students, faculty, and staff

Beauchamp in conversation with Anthony Fauci, Distinguished University Professor in the School of Medicine’s Division of Infectious Diseases, an academic division that provides clinical care, conducts research, and trains future physicians in infectious diseases.

Photo: Elman Studio

the opportunity to immerse themselves in a learning environment with close proximity to other policymaking people and institutions.

Programs at the Capitol Campus include the Center for Global Health Practice and Impact, the Center for Global Health Sciences and Security, the Health Justice Alliance, and the Georgetown-Howard Center for Medical Humanities and Health Justice. Both the School of Health and the School of Nursing plan to offer courses and research endeavors there in the coming year.

Back on the Medical Center campus, Beauchamp sees opportunities to improve the physical infrastructure. “Part of the work is to create spaces that are more appropriate for our faculty to do research, and spaces to better educate our students.”

His long-term vision will include innovation districts like the one he shepherded in Detroit, enhancing Georgetown’s position as an academic incubator. He sees an opportunity to more fully integrate innovation with Jesuit values, fostering collaboration among students, faculty, government, and

industry to drive cutting-edge research and clinical excellence. Innovation districts also create jobs, economic resilience, healthy environments to live and play, and access to education for all, he notes. “If we are to improve health, we have to address the social determinants of disease.”

Finally, he is committed to boosting philanthropy and diversification of funding in order to support these efforts, as well as to substantially reduce the debt load for Georgetown nursing, health, biomedical, and medical graduates. “For our education to be accessible to all, we have to find ways to lower the cost of a Georgetown degree. We also have to lessen the debt they graduate with so that the path they follow and the communities they serve are defined by the impact they seek to have, not the debt they need to resolve.”

“My overwhelming takeaway from the first 90 days is gratitude. People here are deeply committed and inspired. I am so blessed to be able to join this community. My commitment is to continue to listen and learn and to do all I can to support the great people of this institution as we together hasten the pace to bring hope and healing to all.” n

Beauchamp meets with regional representatives and youth ambassadors of Hyundai’s Hope on Wheels, one of the largest nonprofit funders of pediatric cancer research in the country.

Illustration: iStock

By Lauren Wolkoff

When Jill P. Smith gets frustrated by the lack of medical breakthroughs in pancreatic cancer, she derives motivation from the collection of pins on her white coat.

Each of what she calls her “angel pins” represents a patient who has passed away from the disease. Smith, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at the School of Medicine is impatient to be able to offer her patients something beyond what is currently available.

“My patients need more than what we can currently offer them. They tell me, ‘Dr. Smith, please don’t give up, keep trying,’” says Smith, who sees patients at MedStar Health and the DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center. “They really want us to participate in the research, even if they realize it won’t benefit them personally.”

As a physician-scientist who maintains an active research portfolio, Smith is passionate about ensuring scientific discoveries do not remain in the lab. This means working tirelessly to advance scientific discoveries to clinical trials with the goal of helping improve patients’ prognosis and survival.

If caught early, pancreatic cancer can be curable, but it is often diagnosed too late. Around 90% of precancerous lesions of the pancreas are not seen on routine imaging scans because they are microscopic, leading to more cases being diagnosed at stage 3 or later, when the cancer has spread.

“If we just go with the flow of what everyone else is doing, we will not shift the field,” Smith says. “There have been no major breakthroughs in

pancreatic cancer in 50 years, no new drugs in over 10 years, and very little improvement in overall survival. We need to be looking for the next big thing.”

CRADLE OF INNOVATION

Universities and other academic institutions are often thought of as cradles of scientific innovation, with vast amounts of federal funding coming in to support research.

Nearly 83% of the total budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds extramural research at universities and other research institutions. In fiscal year 2023, the NIH allocated nearly $35 billion for extramural research funding.

Yet while ideally situated to pursue big ideas, universities are not set up to fully translate discoveries into products or drugs that can be manufactured and commercialized at a large scale.

Ensuring academic discoveries can have a broader impact on human health requires a process known as technology transfer—or the translation of scientific discoveries together with industry partners into a marketable product or service. At Georgetown, all technology transfer functions are housed in the Office of Technology Commercialization (OTC), which was created over 20 years ago to help researchers protect their discoveries and, hopefully, move them into the licensing and commercialization phase.

“Universities are innovation engines where researchers are free to explore their passions and their ideas to tackle the world’s problems,” says Tatiana Litvin-Vechnyak, vice president of

| Design by Shikha Savdas

technology commercialization at Georgetown. “We want to understand the mechanism of disease, but we are not in the business of manufacturing products at a global or even a national scale.”

That’s where industry comes in. The OTC works closely with researchers to build that bridge—beginning once a discovery is made to protect that intellectual property through patenting, copyrights, or trademarks, and then moving through the process of commercialization via partnerships with private companies.

The steepest learning curve for researchers who work in academia is to regard their discoveries as potentially valuable intellectual property, and not just matters of scientific interest. The OTC works to ensure that they disclose any potential intellectual property prior to going public with their findings, for example, in a journal or at a conference.

“Intellectual property is absolutely the key to all of this. Once an idea is out in the public domain, we are no longer able to protect it through patenting,” Litvin-Vechnyak says. “It’s a real culture shift that we are working on with researchers.”

A LEGISLATIVE AND CULTURAL SHIFT

To understand the scope of scientific advancements at Georgetown, one must first look back 45 years.

In 1980, the landmark Bayh-Dole Act was enacted, prompting a seismic shift at universities and research institutions across the United States.

Formally known as the Patent and Trademark Act Amendments, the law established a federal policy that enabled universities to identify and effectively work with potential industry partners interested in moving discoveries of new drug targets and devices into commercial development. The government reserves a royalty-free, non-exclusive license to use any such invention for government purposes.

Before this law’s passage, universities were not able to own or outlicense research innovations made possible by federal funding. Therefore, few inventions were actually commercialized—meaning the impact of federal funding did not reach the public.

“The Bayh-Dole Act transformed our space so that universities, research institutions, and companies could own their intellectual property,” Litvin-Vechnyak explains. “With that has come the responsibility to advance those discoveries to make sure they end up benefiting the public. This is also core to Georgetown’s mission and values.”

With a surge in university-driven innovations, universities began to create dedicated offices and roles to respond to the new demands of technology transfer. Over the decades since, the space has become increasingly multidisciplinary, attracting professionals in law, science, and business.

The OTC’s 10 staff members, led by Litvin-Vechnyak, who is trained in pharmacology, include experts in biotechnology, biochemistry, intellectual property law, mechanical engineering, data sciences, marketing, and business entrepreneurship.

The team’s remit includes evaluating inventions, navigating the patent and copyright process, pursuing licensing, and supporting the establishment of startup companies, among other needs. These steps can take years—establishing a commercial relationship is just the beginning.

“It’s not like you set it up, hand it off, and forget about it,” says Litvin-Vechnyak. ”We often work with companies for a very long time.”

CULTIVATING AN ENTREPRENEURIAL MINDSET

Samir N. Khleif, a professor of oncology and director of the Center for Advanced Immunotherapeutic Research at Georgetown’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, says he has an entrepreneurial mindset within the academic environment. Moving towards spinning out companies from his inventions has been a “natural progression” over the years, as his research in developing novel immunotherapy drugs for cancer has evolved. This has led to the launch of two therapeutic biotechnology companies.

Khleif’s research forms the basis of three clinical trials currently underway at Georgetown, testing new ways of combining three drugs to treat immunotherapy-resistant cervical, ovarian, lung, and pancreatic cancers. His goal is to understand how to improve a tumor’s response to immunotherapy, which despite much progress, is still effective in only about 15% of patients with advanced cancer.

For one of the trials, Khleif’s team forged a unique collaboration with three different pharmaceutical companies: Janssen

(From left to right) Tatiana Litvin-Vechnyak, Ph.D., vice president of technology commercialization; Jill P. Smith, M.D., professor; Spiros Dimolitsas, Ph.D., senior vice president for research and chief technology officer

Photo: Art Pittman

Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Targovax. Each company had one of the drugs needed for the proper treatment, but none had all three.

“Because we are able to take this highly unusual route, we have been able to translate some of the findings that we have had in the lab into patient care,” he says.

Adopting an entrepreneurial mindset creates much wider avenues for impact, Khleif adds.

“You can invent, and you can publish. But finding a way to translate this into patient care is the difference between universities that foster discoveries to benefit humanity and those that are essentially cemeteries for invention,” he says.

A WHOLE ECOSYSTEM APPROACH

The OTC launched the Faculty Entrepreneurship Academy in Spring 2024 to explore the fundamentals of translating research discoveries into business ventures.

The sessions bring expert speakers to support and educate faculty on the process of commercialization and entrepreneurship.

According to Litvin-Vechnyak, the academy encourages faculty cohorts to explore questions such as whether their discovery can become a viable product, if the market actually needs the proposed therapy or device, and what the regulatory approval process entails. The sessions are also an opportunity to bring awareness of Georgetown’s research portfolio by inviting people from local and regional agencies, such as the Maryland Department of Commerce and the District of Columbia Deputy Mayor’s office.

“As we look at our opportunities for translation of our research for broader impact, it takes all these entities in the ecosystem to help us advance it,” she said.

Faculty also learn how industry works, including topics such as why companies operate the way they do, how they think about fundraising, milestones, and reporting, and the importance of shareholder obligations.

Georgetown innovation at a glance

260+

Technologies under management

Active licenses and options; exclusive and non-exclusive

662

Intellectual Properties (issued and filed patents in the US and foreign countries)

13 80+

Active startups

Select Georgetown successes

Historic discoveries at Georgetown have yielded important technologies that are translating into improved outcomes for patients.

• Whole-body CT Scanner

• BluVector

• T-wave Alternans Diagnostic

• Technology leading to the first HPV Vaccine (Gardasil 9)

• Oncolytic Viral Therapy (IMLYGIC)

• Allegra®

• HPV Diagnostic

• Conditional Programming

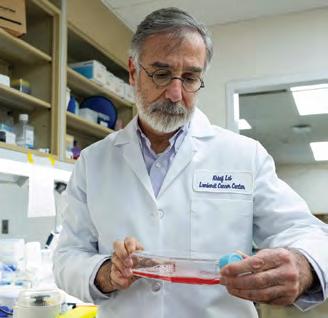

Samir N. Khleif, M.D., biomedical scholar professor, conducts research that forms the basis of three clinical trials at Georgetown, testing new ways to treat cervical, ovarian, lung, and pancreatic cancers.

Photo: Phil Humnicky

“The idea is that they’ll be better informed about the players and the white space that might exist for them to bring something new forward,” Litvin-Vechnyak says.

FROM THE BEDSIDE TO THE BENCH

Two collaborators, basic scientist Anton Wellstein and transplant surgeon Alexander Kroemer, attended the Faculty Entrepreneurship Academy this past October—their interest piqued by their own experience working to commercialize their joint discoveries.

Wellstein, a professor of oncology and pharmacology at Georgetown Lombardi, and Kroemer, a transplant surgeon at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital and director of the Center for Translational Transplant Medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, have uncovered a new way to detect problems in a transplanted liver as early as the time of transplant. By offering an important indication of whether and where something has gone wrong, their discovery holds promise for pinpointing liver tissue failure—and ultimately improving the viability of liver transplant procedures.

While translational research often goes from “bench to bedside,” in this instance the researchers are working from the bedside to the bench—taking blood samples from Kroemer’s liver transplant patients and analyzing them against a “library” of cell fragments called cell-free methylated DNA developed in Wellstein’s lab.

The researchers are working to identify a partner to commercialize their technology and develop it for clinical use, Wellstein said. At the same time, the team is continuing to dive deeper to identify more subtypes of liver cells for more

precise diagnoses, as well as looking to apply the technology to organs beyond the liver.

Despite their success, Wellstein and Kroemer have seen that the road to commercialization is not always a straight line.

“Having great science does not guarantee that you will have great success commercially,” Kroemer says. “If you want to move towards commercialization, you realize how many other elements are required.”

Wellstein agreed, and noted that he has been sharing insights he has gleaned about the process with his graduate students.

“I want them to understand that it’s not enough to sit in an ivory tower thinking beautiful thoughts and making beautiful discoveries,” Wellstein said. “We have a societal responsibility to make our research useful and available.”

REAL-WORLD IMPLICATIONS

In her lab focusing on pancreatic cancer and liver disease, Smith is also acutely aware of the importance of shaping the next generation of researchers—particularly in connecting the dots between their work in the lab and the real-world impact on human health. She stresses that even the tiniest miscalculation can have even graver consequences than pancreatic cancer.

“When I lecture graduate students who are conducting research, I emphasize to them over and over again to be meticulous in their work, all the way from cell culture up to human clinical trials,” Smith says. “Even one decimal point error in your work could cost the lives of patients if it gets to the clinic.”

Smith feels she is fighting the clock to commercialize her lab’s findings so that more patients can beat the disease.

“It’s not enough to sit in an ivory tower thinking beautiful thoughts and making beautiful discoveries. We have a societal responsibility to make our research useful and available.”

—Anton Wellstein

Basic scientist Anton Wellstein, M.D., Ph.D., and transplant surgeon Alexander Kroemer, M.D., Ph.D., stress that patience and consistency have been the keys to their successful collaboration looking at early markers of liver transplant failure.

Photo: Phil Humnicky

Her lab has identified a receptor that, while normal in non-cancerous pancreases, is over-expressed in pancreases with cancer. This target is receptive to a drug called proglumide, which was originally developed 30 years ago for peptic ulcers. Smith and collaborators have also developed a fluorescent biodegradable nanoparticle that can selectively bind to the receptor—making cancerous cells visible through existing technologies and also offering the possibility of targeted therapies.

These findings, though published in top-tier journals, have been challenging to commercialize because of pancreatic cancer’s status as an orphan disease. An orphan disease is one that affects fewer than 200,000 people in the United States, and which most companies do not consider profitable and thus are reluctant to invest in development.

Proglumide now has received orphan drug designation for pancreatic cancer, a status that affords certain incentives to companies, and a company called CCKr Therapeutics has recently licensed the innovative technology along with the corresponding intellectual property.

Smith is hopeful about the opportunity to change the narrative around pancreatic cancer as an orphan disease. Having received support through the Georgetown University Medical Center Gap Fund, established in 2021 through a $1 million gift from Bill (C’54) and Ruth Baker (Parents ’80, ’84, ’88) to support innovative biomedical research initiatives, as well as through the Ruesch Center for the Cure of Gastrointestinal Cancers at Georgetown, Smith says her breakthroughs demonstrate that it doesn’t always take an enormous investment to make a difference.

“I may be out on a limb, but I’m feeling hopeful that we’re making real progress, and that this will bring a change in this disease’s terrible record,” she says.

Martha D. Gay, assistant professor of medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine, is inspired by watching Smith navigate the intersection between basic science and clinical research. Smith is lead mentor on Gay’s Mentored Research Scientist Development Award from the NIH for early-career investigators.

Gay’s passion lies in the lab—she studies the mechanism of action of drugs to treat metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), an advanced stage of fatty liver disease that includes inflammation and fibrosis. Yet having worked on two phase 1 clinical trials, she admires Smith’s focus on ensuring that her research can benefit patients as soon as possible.

“I love being in the lab, but I also need to be connected with who I’m doing this work for,” Gay says. “It helps me stay focused and remain rigorous in my research when I know that there is a person behind that petri dish.”

She also enjoys spending time working in the community, particularly among underrepresented minority populations, communicating about the importance of scientific research and clinical trials. She views this as a different type of translational research—translating her research and that of her colleagues for the general public.

These interactions remind Gay of the people at the other end of the research continuum.

“Sometimes experiments require extensive troubleshooting, you don’t get accepted by that top-tier publication, or you don’t get the grant. But my pursuit of facilitating and improving liver health outcomes through my research keeps me working towards my overall goal—to enhance the health of those impacted by MASH.” n

Martha D. Gay, Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine at Georgetown’s School of Medicine, enjoys going out into the community to connect with people who stand to benefit from her research on fatty liver disease.

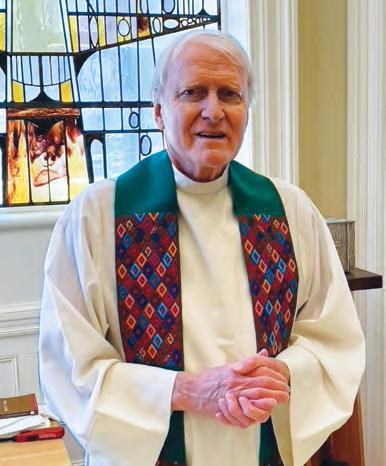

rom an early age, Katie Skelton (N’75) knew she wanted to become a nurse. When her older sisters went off to college in Washington, DC, she visited them frequently—falling in love with the city and setting her sights on Georgetown as the perfect place to study nursing.

Although only a high school sophomore, she requested an appointment with Rose McGarrity, then dean of the Georgetown School of Nursing, to speak about the educational opportunities offered at the school.

“She actually met with me, which was remarkable,” Skelton says. “She encouraged me to continue pursuing my interest in Georgetown. I look back now and think, ‘What an amazing woman she was.’”

Rising through the ranks to become vice president of patient care services and chief nursing officer at St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California, Skelton has been in a position to pay forward the support she received as a high schooler from Dean McGarrity. Most recently, she joined the faculty at Azusa Pacific University as an adjunct, teaching a nursing leaders course. Skelton also works as a health care consultant at Force 10 Partners.

In advising young professionals seeking health care leadership roles, Skelton emphasizes that, along with clinical skills, business knowledge is essential. She is among a growing number of clinicians—many Georgetown alumni included—who have earned advanced business degrees.

“You need to pick up an additional skill set on the business side if you want to be successful in an executive role or as a patient advocate,” says M. Joy Drass (M’73, R’74), executive vice president and chief operating officer for MedStar Health, who

holds an MBA from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School along with her medical degree from Georgetown.

At the same time, Georgetown-trained practitioners in particular bring to their leadership roles a dedication to cura personalis, balancing financial imperatives with patient needs.

“What I take from my experience at Georgetown is that Jesuit tradition of compassion,” says Nicholas Holmes (C’89, M’93), president of the Benioff Children’s Hospitals of the University of California San Francisco. “In each and every decision I make I know that, yes, it’s a business decision, but having been a clinician I know how that decision impacts the patient, as well as the parents and other caregivers.

“It allows me to keep the patient at the center, striving to make the best decision not only for the hospital but also for the patients who seek care here.”

ADDING VALUE

While the percentage of U.S. universities offering MD/MBA programs increased from 26.4% in 2002 to 60.9% in 2022, it’s still relatively rare for health care administrators to have clinical backgrounds. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimates that only 5% of hospital CEOs are physicians. (At children’s hospitals, Holmes notes, that figure is much higher, at 30%.)

Universities across the U.S. have responded by developing innovative programs tailored specifically to prepare clinicians to assume leadership roles. At Georgetown, in addition to a joint MD/MBA program between the School of Medicine and McDonough School of Business, the medical school offers a well-established Healthcare Leadership Track (HLT), overseen by former dean Ray Mitchell (W’86, MBA’13, Parent’15) (see sidebar).

The School of Health has developed a renowned valuesbased Master of Science in Health Systems Administration as well as an Executive Certificate in Clinical Quality, Safety, & Leadership. This past year, the McDonough School launched an MBA Certificate in the Business of Health Care.

Skelton decided to attend a program for nurse executives at Wharton relatively early in her management career. “At that time, clinical leaders were being thrust into much bigger roles than directors of nurses had historically been. The finance piece of it was probably the most uncomfortable part of my early work, and I knew I needed that background,” Skelton says.

“It was a three-week intensive program on campus and I had to commit to bringing my boss for several days, who agreed to come. It was a great, great opportunity for me.”

Similarly, Holmes completed a business of medicine certificate program at Johns Hopkins University’s Carey Business School while serving in the U.S. Navy. Both Skelton and Holmes went on to earn their MBAs.

When advising current medical students contemplating a health care leadership role, Drass stresses that while a business skill set is essential, it’s best to start off in clinical practice.

“You have to experience the joy of practicing medicine first,” she says. “That’s why you went to medical school. What comes from that experience is an understanding of the dynamics between physician and patient—the human part, but also the complex operational systems that are foundational to the delivery of care.

“Having that understanding is where you can add real value, both in your journey as a leader and also in your advocacy for patients.”

THE LANGUAGE OF BUSINESS

Drass went into clinical practice after graduating from Georgetown School of Medicine in 1973—where she was one of only 10 women in a class of 115—and completing a residency and critical care fellowship. She worked for 13 years as an intensivist in the surgical intensive care unit at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

She then made the decision to attend Wharton’s MBA program. “I went to business school at a time when there was a lot of disruption in health care,” she says. “Initially, it was not about how it would change my career, but more that I couldn’t be a good patient advocate if I didn’t understand the financial realities.”

At Wharton, she took only one course specifically focused on health care. “My thought process was, I’m not here for you to teach me health care—I know health care. I’m here for you to teach me business,” she says. “So I really stretched myself into the more core business courses. And I think in retrospect that was the right decision.”

After earning her business degree in 1991, Drass didn’t intend to move immediately into an administrative role.

Kenneth Samet, then president of MedStar Washington Hospital Center and now CEO of MedStar Health, offered her a position as vice president for professional services and associate medical director. “It was a terrific opportunity that I couldn’t pass up, so I made the transition more quickly than I might have.”

In that position, Drass played a crucial role in establishing the Georgetown/MedStar Health partnership. She went on to serve as president of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital for nine years before moving into her current job.

As she took on successively more challenging responsibilities, Drass continued to draw on her business training. “What business school gave me was language and skills so that I could bridge the gap between clinicians and administrators. I often tell people that my main job every day

is translating what the clinicians are trying to say to the administrators and translating what the administrators are trying to say to the clinicians, because not infrequently, they’re on the same page but they just don’t know it.

“I think our North Star, both with MedStar as a whole and at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, is to provide high-quality, safe care to every single patient. Decisions are made through that lens,” she says. “As we become more and more evidence-based in our practice of medicine, that’s helpful. We’re better at understanding what treatments help which subset of patients.”

She thinks Georgetown and MedStar are particularly well-positioned to comprehensively address the complexities of the U.S. health care system.

She cites as an example the Georgetown Health Justice Alliance Perinatal Legal Assistance & Well-being (LAW) Project, which provides legal services to pregnant and postpartum patients receiving care at MedStar Washington Hospital Center. The project is part of the larger MedStar Health’s Safe Babies/Safe Moms initiative supported by the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation.

“I love the Georgetown MedStar partnership. What we learn from the things we do, we share,” she says. “When you

Photo: Courtesy of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals

put the two organizations together, with care delivery, education, and research, it’s a pretty powerful force for change.”

LEADERSHIP AS A DISCIPLINE

Like many clinicians who transition to executive leadership, Drass views her position as an extension of her previous responsibilities providing direct patient care. “I don’t feel like I left the world of care delivery,” she says.

Nicholas Holmes shares that perspective. “I can take care of one patient at a time being a physician or surgeon, but being a leader in health care, I’m responsible for thousands of patients,” Holmes says. “I can really make an impact in changing people’s lives, not just on an individual level but on a macro level.”

A pediatric urologist, Holmes served as senior vice president and chief operating officer at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego before moving into his current position in March 2024. In addition to overseeing UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals, he is responsible for all pediatric clinical services across the health system—encompassing six affiliated hospitals, 12 specialty satellites, and more than 180 primary care pediatricians.

Holmes credits his Georgetown education for starting him on his current path. “Being at medical school at Georgetown really gave you the opportunity to be hands-on. We used to have this phrase, ‘See one, do one, teach one’—that made you be active in how you engaged in the workplace. It opened my eyes to what it’s like being a leader of teams.”

After medical school, Holmes served as a physician in the U.S. Navy for 15 years, rising to the rank of commander. “The Navy really honed those leadership skills. As I got older, I realized that leadership was a discipline, just like being a surgeon,” he continues.

It was then that Holmes decided to pursue opportunities for advanced executive training, first in the Johns Hopkins certificate program, then in the Physician Executive MBA program at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Attending business school also enabled Holmes to pair leadership training with the necessary financial education. “It’s absolutely paramount if you’re going to be a leader in health care that you understand the financial side,” he says.

That knowledge is especially vital because the health care payment system is unique, Holmes says. “We’re the only industry where what we charge is not what we get paid nor does it reflect the value of what we provide.”

Pediatric care presents an additional set of challenges, he adds. “A lot of what we do in pediatrics doesn’t contribute to the bottom line. You have to weigh that all the time, because many of the activities that aren’t revenue-generating are absolutely critical in childhood development—especially related to psychosocial support and also the support we provide to families that’s essential to the way kids heal.

“We keep our programs open to anyone regardless of their socioeconomic status, so it forces us to be creative in what we do. We’re so fortunate to have philanthropic support as well as community support. And sometimes it’s better that you don’t lead, but you instead collaborate with an organization that may have more support and more assistance.”

From his undergraduate years at Georgetown to his current position as hospital president, Holmes sees service as a throughline in his life.

“I went to Georgetown for the academics, but the spirit of Jesuit education and service really spoke to my soul. I just didn’t realize it at the time,” he says. “I think that was pivotal in forming who I am as an adult and as a leader in health care.”

PRACTICING EQUANIMITY

Katie Skelton found her calling as a health care leader while working at City of Hope comprehensive cancer center in California. “I loved oncology nursing, but as it turned out, I really loved taking care of oncology nurses,” she says. “I saw my calling as creating systems and processes that support nurses in the work that they do.”

Moving into management at City of Hope, she eventually was appointed chief nursing officer. In that position, she succeeded in integrating all clinical departments into cross-functional teams.

Soon after accepting an executive position at St. Joseph’s Hospital, she made the decision to attend the Wharton School nursing executive program. A decade later, she enrolled at Claremont Graduate University, where management education pioneer Peter Drucker had developed one of the country’s first executive MBA programs for working professionals.

“I very carefully picked where I wanted to go to graduate school. I spent three years learning the Drucker method of leadership and I think it helped me form my own philosophy of how to lead,” Skelton says.

“Lobbying for resources and supporting the frontline versus being a team member in the executive suite, that is a balancing act. There’s a lot of give and take,” she says. “It’s the people connection that makes a difference—you’ve got to have relationships and communicate well.

“Everywhere I’ve worked, I’ve always had advisory councils of frontline staff nurses. And I made it a point to round on days, on nights, so I wasn’t afraid to know what was going on,” Skelton adds.

“There’s a word—‘equanimity’—that means something isn’t necessarily good or bad. Say you need to merge with an organization—there are plenty of people who just jump to ‘that’s terrible,’ or ‘oh my gosh, that’s wonderful.’

“In that situation, equanimity is an important word to keep in mind. You have to say, ‘We’re going to move in this direction, I’m going to have all your input, we’re going to see how this works, we’ll tweak it, we’ll revisit it, and do it so it works.’ It’s moving forward with an understanding that perfect is the enemy of the good.”

Skelton was able to apply that leadership approach during a financial crisis at St. Joseph

Hospital when an entire service line was moving to another hospital. “We gave every department a challenge—how do we do work with 10 to 15% fewer resources? The frontline came to us with many more opportunities than we had ever hoped for.”

As a teacher and mentor, Skelton emphasizes that leadership requires self-knowledge. “Spend time defining your own values. In leadership, you are constantly challenged to make sure that what you’re creating—or dismantling—is consistent with your values.

“I always asked my leadership group, ‘Would all of us still want to work here after we make these changes?’ I think it’s helped some nonclinical people especially to rethink things they were advocating for.”

Above all, she says, strive to be a servant leader. “It’s all about the common good and caring for the individual—mind, body, spirit. I was fortunate to work at City of Hope, where their mission stated: ‘There is no profit in curing the body if you destroy the soul.’ That went along with my upbringing, my training, my Georgetown education.

“I am grateful every day for the education I received. The experience at Georgetown made me the leader that I am today.” n

Photo: Phil Humnicky

When students enroll at Georgetown School of Medicine, they have the opportunity to augment their coursework by participating in a four-year longitudinal academic track that explores subjects ranging from population health to spirituality in medicine.

Among the most popular, with more than 130 participants, is the Healthcare Leadership Track (HLT). Directed by former dean for medical education Stephen Ray Mitchell, HLT enables students to gain a broader view of real-world medicine, with the goal of equipping them to be agents of change as physicians. There are three concentrations: health care innovation, health care strategy, and patient quality and safety improvement.

In the health care innovation concentration, small groups of students develop either a product or service that represents an innovation in health care. “They create a complete economic model of how it would work, and then they enter a pitch competition run by the business school,” says HLT student leader Griffith Gosnell (M’26).

As student leader, Gosnell has been instrumental in arranging speaker engagements for the health care strategy concentration. “Our goal is to connect students with leaders in different executive positions—the CEO of OrthoVirginia, people from Capitol Hill,” he says.

“We recently had a fascinating discussion with a private practice plastic surgery owner. He drafted out all the factors I’ve never thought about as a medical student, like showing how practice in an academic center breaks down in terms of cases per hour and the benefits of partnering with a surgery center if you’re in private practice.”

As a capstone project, Gosnell explains, all students in the concentration are required to initiate contact with a health care leader in a job that they would want one day. “The primary objective is to ask them, ‘How did you get into this? Is it something you love? What is your life like day-to-day?’” From this initial contact, students can potentially gain long-term contacts and valuable career mentorship opportunities.

“The beauty of the capstone is that you can go in any direction,” says Gosnell’s fellow student leader Madeline Karsten (M’25). For her own capstone in patient safety and quality improvement, Karsten is expanding on an earlier research project examining how the pandemic and the rise of telehealth has impacted people living with HIV in the local area. “I’m focusing on systems, analyzing how virtual medicine is both helpful and a hindrance to care.”

Karsten credits the concentration’s faculty advisor—Carole Hemmelgarn, program director of the Executive Master’s in Clinical Quality, Safety & Leadership at the School of Health and senior director of education for the MedStar Institute for Quality & Safety—for enabling her to gain a systemwide perspective.

“She lost a child due to medical error, and she’s committed her life to advocating for improved policies,” Karsten says. “It really struck a chord for me, helping to contextualize the importance of having effective workflows and policies in place to keep patients safe.

“Thinking about hospital systems and health systems through that lens will certainly stay with me for the rest of my career.”