ARTIST PASS

CONVERSATIONS FROM THE BOOKS THAT DEFINE ROCK

SONG WRIT ING

In the 140 years that separate Tin Pan Alley and Taylor Swift, popular songwriting has grown into a gargantuan industry, yet at its core the song – and its connective purpose –remains the same. But is it art or craft?

A question of discipline or being ‘in the flow’? Best as a solo endeavour or stronger in a partnership? In truth, there are no songwriting absolutes, instead, as many different methods as there are songs themselves. However, all the greats have a preferred practice, be it writing in the car, as Chuck D does or, for Paul Weller, late at night. As to motivation, from Jimi Hendrix’s experiencing of emotions as colours to Brian Wilson’s loneliness and John Lennon’s sheer joy of creating, all writers give life to the aeons-old, universal communication that is the song.

1 How Can It Be?

2 The Beach Boys

3 Wembley or Bust

4 Classic Hendrix

5 Back Beyond

6 Magic: A Journal of Song

7 Livin’ Loud

8 A Guide to the Labyrinth

9 Sunshine of Your Love

10 I Me Mine

11 Thin Wild Mercury

12 Love That Burns

13 Love the One You’re With

14 Definitely

15 Days & Summers

16 The Beatles Anthology

17 Whatever It Takes

18 Bon Jovi Forever

19 Transformer

20 Mr Fantasy

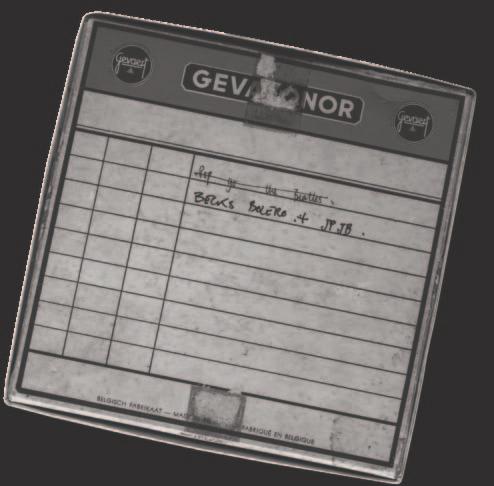

PAUL McCARTNEY Sometimes I’ve got a guitar in my hands; sometimes I’m sitting at a piano. It depends, whatever instrument I’m on I write with. Every time it’s different. 16

JOHN LENNON Usually one of us writes most of the song and the other helps finish it off, adding a bit of tune or a bit of lyric. If I’ve written a song with a verse and I’ve had it for a couple of weeks and I don’t seem to be getting any more verses, I say to Paul, and then we either both write, or he’ll say, ‘We’ll have this, or that.’

It’s a bit haphazard. There’s no rules for writing. We write them anywhere, but usually we just sit down, Paul and I, with a guitar and a piano, or two guitars, or a piano and a guitar and Geoff (that’s George). 16

PAUL McCARTNEY Crediting the songs to Lennon and McCartney was a decision that was made very early on, because we aspired to be Rodgers and Hammerstein. The only thing I knew about songwriting was that it was done by people like them, like Lerner and Loewe. We’d heard these names and associated songwriting with them, so the twoname combination sounded interesting. 16

JOHN LENNON We wrote together because we enjoyed it a lot. It was the joy of being able to write, to know you could do it. There was also the bit about what they would like. The audience was always in my head: ‘They’ll dance to this,’ and such. So most of the songs were oriented just to the dances. And also they’d say, ‘Well, are you going to make an album?’ and we’d knock off a few songs, like a job. Though I always felt that the best songs were the ones that came to you. 16

PHIL COLLEN There are so many different ways to write songs and I like using all of them. There’s the hack songwriter approach, where you just dial it in as a mathematical process. And then there’s a purely artistic approach, where you let an idea flow and grow. Being a guitar player, I sometimes start with a guitar part or bass riff. Or it can be an interesting word or phrase that sparks things off. I’m fascinated by the whole creative process. 14

RONNIE WOOD I used to sit up in my bedroom and write songs. It was a pleasurable challenge at the time, like moulding from a piece of clay. Keith Richards said he was doing the same thing at the time, but described his technique as grabbing songs out of the air. 1

BRIAN WILSON I thought of my room as my kingdom. It was somewhere I could lock out the world, go to a secret little place and think, be, do whatever I wanted. The early song everyone wants to point to as being about loneliness is ‘In My Room’. I felt a little lonely at times, but I also knew that it made for good songs. Loneliness was something that everyone felt but was afraid to talk about. That was something I learned from The Four Freshmen. They always had an ache in their songs – not just in their voices but in the things they were singing about. 2

JEFF LYNNE Loneliness is an easy emotion to put into a song because everybody knows what it feels like. I don’t always write lonely songs, though I’ve done quite a few. Del Shannon wrote the same sort of songs and Roy Orbison, too, but Roy’s did have happy endings sometimes. You know, the girl comes back; she turns around and walks back to him at the end of the song. 3

JIMI HENDRIX Some feelings make you think of different colours. Jealousy is purple; I’m purple with rage, or purple with anger, and green is envy. 4

YUSUF / CAT STEVENS I love ‘Into White’ because I love colours, and every major hue is mentioned. I learned one time that if you were to spin a disc with all the colours on it, they all turn into white.

I imagined I was writing the song together with Van Gogh. I love the vibrant colours in his art and I just wanted to use every one that I could in the lyrics. The listener can submerge themselves in those images and those sounds, just as I submerge myself in art.

The greatest thing is to sit down and write lyrics. I can write a song anywhere, but I have to be by myself. 5

PAUL WELLER Late at night is always the best time to write. I like that sense of peacefulness and isolation where you think you might be the only person who’s still awake. You don’t get that during the day in my house. I’ve got lots of recordings on my phone where I’ve had an idea and the only way I can get any peace and quiet is by shutting myself in the toilet. 6

YUSUF / CAT STEVENS For me, it’s great to write in a car. If I’m being driven somewhere in a taxi, I find that my mind is being constantly taken over by new views which I haven’t got the time to get lost in; consequently my ideas are continuously changing. Then you have to create the song again in the studio. It’s never the same as when you first wrote it, so you have to make it real in the ‘moment’. 5

CHUCK D I’ve written my best records while driving, ever since the first in 1986. It’s an energy I continue to use. The number one thing is to be safe and keep your eyes on the road, but I still keep a pad and a pen in the car for when I’m driving and an idea comes. 7

YUSUF / CAT STEVENS Inspiration for songs comes to me when I’m not thinking, when I’m absolutely flowing, and just being. I may write some lyrics down, but mostly I just get the melody, and the words follow. I write songs in different ways. It might start with a whistle or an old traditional record, listening and suddenly getting an idea. It can be talking or it can be just a word. To be a creator you must be able to make something breathe. What I’m doing is just taking something that is already there from whatever I see and remember. I use it and I send it out again – my way. 5

ROBBY KRIEGER I never, ever had a song just come to me. I did a lot of stealing, musically. There’s nothing new in music. Maybe Jim Morrison subconsciously heard those first melodies that he sung to Ray on the beach and they got into his brain somehow, but you never know. I wasn’t lucky enough to be able to just wake up from a dream and think, ‘I’ll write that down.’ It was always more work for me. To me, the words were secondary. To Jim, the music was secondary. 8

JIM CAPALDI Songwriting sometimes comes easy; sometimes not. Once I’ve got good lyrics or written something which I feel is good it’s not long before the music comes. It’s getting the idea and the lyrics which is the most difficult part. Music is music but a song is a very personal thing. It’s music and it’s also something being said by somebody. The music and the lyrics, if it’s a good song, they go so well together that they can’t be parted but it’s still two separate things in reality – the lyric and the melody. 20

1 How Can It Be?

2 The Beach Boys

3 Wembley or Bust

4 Classic Hendrix

5 Back Beyond

6 Magic: A Journal of Song

7 Livin’ Loud

8 A Guide to the Labyrinth

9 Sunshine of Your Love

10 I Me Mine

11 Thin Wild Mercury

12 Love That Burns

13 Love the One You’re With

14 Definitely

15 Days & Summers

16 The Beatles Anthology

17 Whatever It Takes

18 Bon Jovi Forever

19 Transformer

20 Mr Fantasy

CHUCK D The thing that attracted me to hip-hop in 1976 was the technical aspect. The DJs – Frankie Crocker, Hank Spann – they all had their own style, like the great sportscasters. When hip-hop came around I saw it as a combination of the worlds of music and sport.

Way before doing the He Got Game soundtrack in 1998, I’d slip sports metaphors into my lyrics. I would practise my sportscaster voice and intonations either in my room at home playing some dice sports game or down at Roosevelt Park where the summer league basketball legends dwelled. I could get any of those voices down. 7

PAUL WELLER My early songs were basically copies of Beatles songs, really. I just changed them a little bit here and there. We bought The Beatles Complete, which is a big songbook that came out in the early Seventies, and simplified all the songs, probably using the wrong chords, as well as simplifying the chord patterns. We’d steal and adapt. Everyone does this when they start. Like the Fabs did, like Bob Dylan did, like everyone when they start out. You can only use the tools you’ve got at that time. This plus all your influences get fed into what you’re trying to write. 6

JON BON JOVI Songwriting didn’t come easy for me. To figure it out you first play other people’s songs, then you try to emulate a song you’ve heard – really you’re ripping it off –and then to make it your own you change the rhyme scheme from O to A. So ‘Hey Joe’ becomes ‘Hey John’. Then you have to put a chord progression to it, figure out a simple arrangement and work it up with a band. Through trial and error somehow it starts to make sense. The model isn’t that hard to understand. It’s doing it well that’s magic.

MICK ROCK One thing that connected me with Lou Reed was the fact that I had a classical English education and Lou had studied literature at Syracuse. Delmore Schwartz was one of his teachers, which was very inspirational for him. Lou was highly literate, so I could talk to him about various writers and he actually knew what he was talking about. That wasn’t true of all rock and rollers. 19

JORMA KAUKONEN I have no doubt that Janis Joplin was self-conscious about her lyric writing. This was still the beatnik time, so the written word was very important to us. But lyrics don’t need to be complicated to be powerful. Some of the best writing is the most simple and minimalistic.

Janis always had a book with her. I find it interesting today that there are people who try to be artists who don’t read, because to be a good writer you have to be a good reader. You can’t give away what you don’t have. 15

PETER ALBIN Janis’s raw, emotive quality touched a lot of people, particularly women. There’s something about Janis that will never die. This strong woman has shown generations of female singers, entertainers and actresses that you’ve got to put your heart out there. You might have to do some healing later on, but that’s OK. 15

CHRISTINE McVIE Being one of a few women in such a highly testosterone filled world was an odd situation. Although there were only a handful of women songwriter/singers, I don’t think I was really conscious of that at the time. I actually loved that world and thankfully was treated with friendliness and respect for the most part. 12

ERIC CLAPTON People think I wrote ‘After Midnight’ and ‘Cocaine’ because I’ve made them my own, but J.J. Cale’s are the versions that I really like. I can play like that til the cows come home. 9

PERRY FARRELL Jim Morrison told the most incredible stories through his songs, because he was living an incredible life. So, when I write, my bullseye is Jim Morrison. I start out by telling myself, ‘Do not shame Jim Morrison.’ 8

DAVID FRICKE I was interested in the way Jim Morrison challenged the barriers of language. His writing style was about calling up images and fragments of stories – real short, sharp shocks that led you to question what language could be. Say what you mean, mean what you say and say it in a way that opens your mind, your heart and your life to the next possibility. The fact that he had everything else made him extremely popular at the moment that the culture actually needed it and could respond to it. 8

JIM MORRISON I thought I was going to be a writer or a sociologist, maybe write plays. I never went to concerts – one or two at most. I saw a few things on TV, but I’d never been a part of it all. But I heard in my head a whole concert situation, with a band and singing and an audience – a large audience. Those first five or six songs I wrote, I was just taking notes at a fantastic rock concert that was going on inside my head. And once I had written the songs, I had to sing them. 8

ROBBY KRIEGER I realised that Jim was obviously different from other rock and roll writers, except for maybe Bob Dylan, but he didn’t flaunt it so you didn’t think of him that way. At the time, I was too dumb to realise how great his stuff was. I knew it was good, but I didn’t think of him as a genius. I do now. 8

HENRY DILTZ Dylan was one of the first to write original music, along with The Beatles, and then everybody started doing it. There was a change in the air, like the air was blowing in from a different direction. Everybody started expressing their thoughts and feelings in their own words and music. Instead of there being the songwriters and the singers, now they were one and the same. 13

GEORGE HARRISON I have never really thought about myself as someone who writes songs as a craft. Many songwriters do. I suppose I have seen it that way without being conscious of it, but not often. Mainly the object has been to get something out of my system, as opposed to ‘being a songwriter’. 10

OLIVIA HARRISON As I have found with other songwriters, George didn’t give much away when explaining his lyrics. Wasn’t it enough that he laid his emotions and thoughts on the line for everyone to hear? I finally stopped asking George what his songs were about because his answers never seemed to satisfy my questions. ‘Liv, I just needed something to rhyme with “love”, so I used “glove”.’ 10

JOE ELLIOTT Some lyrics sound good but read badly; others read like beautiful poetry, but when you try to sing them they’re just nonsense. You’ve got to find the middle ground. 14

GEORGE HARRISON The note that you use makes you think in a certain way. Listening to a sitar, for example, you think in those terms, anyway some people write riffs to which you can go out and bebop and some compose good stuff that is wellplanned and thought out and musical. It seems to me that for a certain type of writer, it is not so much what he feels or stories about what he is going through, but it is more like a craft 10

PHOTOGRAPHY

p.60 Paul McCartney and John Lennon by Mike McCartney, taken from Mike McCartney’s Early Liverpool

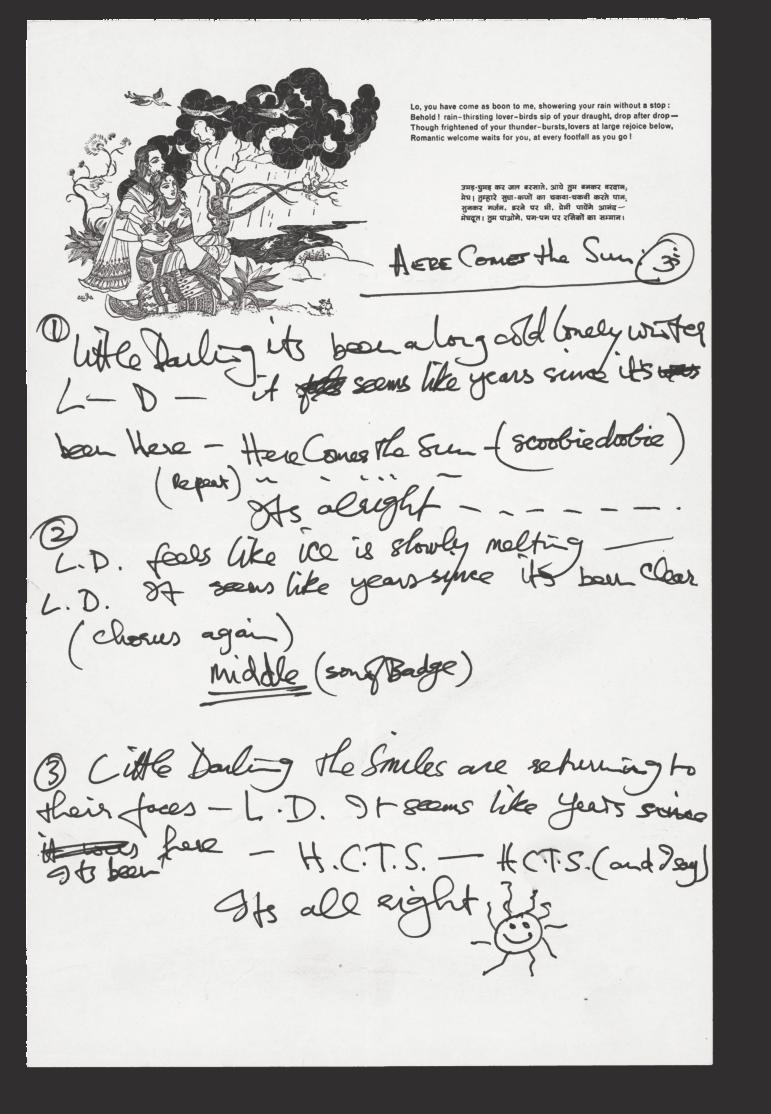

p.66 Handwritten lyrics by George Harrison, taken from I Me Mine

BRIAN WILSON I can write through understanding others. The surf songs are a simple example of that – I have never surfed, but I was able to feel it through Dennis. I find it possible to spill melodies, beautiful melodies, in moments of great despair. This is one of the wonderful things about this art form – it can draw out so much emotion and it can channel it into notes of music in cadence. 2

PAUL WELLER Every song matters to me. I think as a writer you’ve got to keep your tools sharp. The world is full of people who made great records and then tailed off, but maybe I care more now because I wasn’t as good as they were when I started. With me it’s probably worked in reverse. Having said that, there are some performers who have been around a long time and are still doing great work. 6

DAVID CROSBY We had strong value systems and what mattered to us was very essential stuff. We weren’t writing ‘June, moon, spoon’. We were writing about stuff that really mattered. 13

TOM MORELLO At Harvard, I formed a band called Joey Thunder and the Electrical Storm. We were Ivy League dudes in full spandex regalia. We were trying to write songs that sounded like Dokken and Mötley Crüe, as opposed to writing about what I was really interested in. I would try to sneak in songs about the apartheid but it just didn’t mesh with the spandex. 17

PAUL WELLER I’m a very selfish writer in some respects. A song has to get past me before I’m willing to share it with anyone else. I think you have to please yourself first and foremost. Social injustice interested me, politics, the English class system. I’m not sure I was doing anything that different from other bands like The Specials. Thatcher got into power in 1979, and that made a huge difference to people’s lives and needed to be written about. Things very quickly became extreme, and battle lines were drawn. We were all arriving at the same conclusions, and a lot of us still hold the same opinions. 6

YUSUF / CAT STEVENS I think that my songs give an element of hope. If you look at songs like ‘Peace Train’, ‘Morning Has Broken’, ‘Changes’ and ‘Can’t Keep It In’, they all project a sense of optimism about the future and the journey that we’re on. 5

PERRY FARRELL My children are coming up as musicians now. We sit and listen to music and critique it together for hours. It’s the greatest. My son’s beginning to write lyrics and some of them are terrible; they’re silly and goofy, and they’re trying to get a rise out of people. I tell him, ‘Listen, man, your lyrics are really important because once you’ve put them out there you can’t take them back.’ 8

BOB DYLAN I don’t know how I got to write those songs … those early songs were almost magically written. 11

JOHN DENSMORE At times it did feel magical. When Robby sang ‘Light My Fire’, I went, ‘Oh my God’, and when Jim sang ‘This is the end, beautiful friend, my only friend,’ it was like a love ballad. It was just so heartfelt. 8

PAUL WELLER I can be scratching around at home on an acoustic guitar, or singing a funny little idea into my phone, and all of a sudden it becomes a beautiful, fully fledged song. And I’m asking myself, how did we do that again? I still find that fascinating. It’s magic. 6

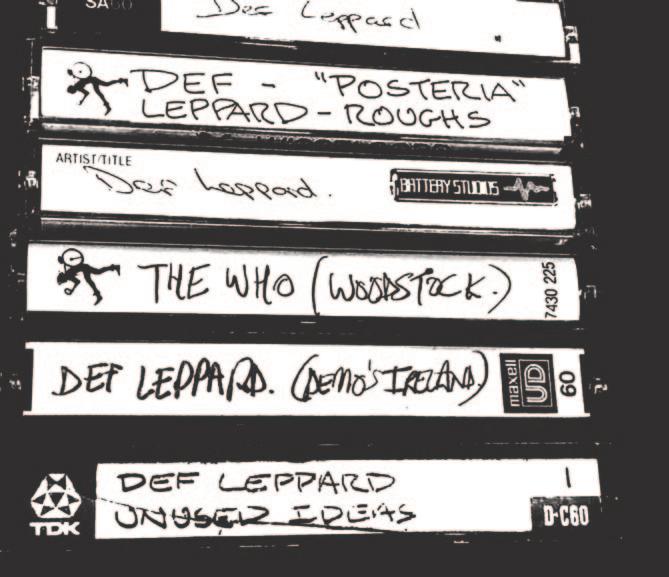

RECORDING

The immense impact of technological advancement on recording is undeniable, from the non-mechanical process pioneered by Western Electric 100 years ago to today’s DAWs-driven home studios. Pivotal to music making, recording affords myriad different studio set-ups and methodologies, whatever a musician’s preference. Brian Wilson enjoyed being able to correct or enhance his music via computer; Alice Cooper believes ‘records now are just too mechanical’. Decamping to isolated stately homes or another country, as Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones famously did, may have fallen out of favour but the aim remains largely the same – to capture a mood and spirit. Which explains Neil Young’s habit of recording around a full moon – ‘because that’s when I feel something happening’.

1 Love the One You’re With

2 Exile

3 Maximum Who

4 Faces, 1969–75

5 The Beach Boys

6 The Producer Tapes

7 I-Contact

8 A Guide to the Labyrinth

9 Definitely

10 Jimmy Page: The Anthology

11 This Is Our Life

12 Love That Burns

RAY MANZAREK To actually be in a recording studio for that first time is an existential moment. It only happens once in your life and if that doesn’t energise you nothing will. 8

NEIL YOUNG When I record I’m always conscious of the Moon. If I can, I’ll start a project about three days before the full Moon, then let it go until a day or two afterwards. Then there’s always a bottoming-out period that happens right after that. So if I’m going to record for four or five days with some people, I’m going to put it together during that time of the month every time. Because that’s when I feel something happening.

And to tell you the truth, when I walk outside I like to see the Moon. It’s gotten to be a friend of mine over the years, so I like to see all of it. Of course, I’m not saying everybody should shut down and forget it unless the Moon’s full, but I’m going for moments in time, captured on record. So, for me, these things are important. 1

MARSHALL CHESS All the records during my regime with the Stones would follow the same process. We would rent a house and a studio, and in the case of Nellcôte the house was the studio. We would rent it for a minimum of a month and we would rent it for 24 hours a day, so it was ours anytime day or night. We’d use our own engineer and look at the studio layout and see what equipment we needed. Most nights they’d begin to jam. The amazing thing about The Rolling Stones was that they may not have seen each other for nine months or so, but within an hour of being together in a recording studio it would be like they’d been rehearsing every night for hours. So most of the tunes would come from jams. They’d get into a groove or riff or backbeat and we’d record it. All of a sudden there would be four distinct tracks and they’d go back and craft these. And sometimes, when another musician like Nicky Hopkins or Billy Preston would come and add their parts, the song would change. The dynamic of an outsider coming in could change the melody line or format. 2

KEITH RICHARDS I can’t sit around on a song too long. I like to get in the studio and write it there. Mick, on the other hand, likes to have it all worked and rehearsed before he goes in. That’s the basic difference between us: I get bored quicker. 2

MICK JAGGER I wouldn’t call it spontaneous if you’ve been there for ten hours on one riff. He just goes in there with a riff and if nothing happens he goes back the next day. It’s all right for him. I have to write the tune! 2

CARL WILSON Everyone that goes into a recording studio wants their music to sound as perfect as they can get it. However, if we have two takes of a song and we have to choose between the one that’s technically accurate and the one with the better feel, we’ll undoubtedly go for the one with the better feel. At a session, we always let nature take its course and, as far as this band is concerned, that seems to be the right approach. 5

RICK SAVAGE A lot of bands go in the studio and try to make it sound as live as possible, whereas we try to make the best recording possible. If that means spending loads of time doing different backing tracks, then that’s how we’d rather do it. We want people to listen to our albums in ten years’ time and think, ‘Well that still sounds pretty good.’ When you’re playing live you can’t replicate everything you can do in the studio, but there’s an energy on stage that makes up for it. On the other hand, when you’re in the studio it’s very hard to recreate the energy that you get from playing live. The two are totally different things. 9

ANDY SUMMERS I think rock and pop should be recorded with a certain rush of energy. They just seem more alive. I never understood how bands could stay in a studio for a year or even three months. I get studio crazy after a while. 6

GERED MANKOWITZ I always enjoyed being in the recording studio, but unless you’re involved in the action it can become pretty boring. There are long periods of inactivity, and photographically it can be quite repetitive. 7

BILL WYMAN There was very little of the songs before we went into the studio. There were never any lyrics. I don’t remember any song that actually had lyrics before we started it. There might have been one or two, but I can’t recall which ones. These were very few and would probably be the ones that Mick was more involved in creating. If Mick came in with a song idea he would have some words and the basic chord structure, whereas Keith would just have riffs, out of which we’d then create a song. 2

GLYN JOHNS The first session I did with [The Who] I, and everyone else, was completely blown away. I’d never heard anything quite like that. The last time I’d seen them play they were The High Numbers, doing Motown covers. They were the most energetic band I’d ever recorded at that point. It was interesting – that whole era was very much a trial and error period. No one had ever had to record anything loud before. Immediately prior to this, even when rock and roll started, it was fairly tame in comparison to what British groups turned it into. With the early Bill Haley records and that kind of thing, there was an upright bass and a drummer playing very quietly, but it was still called rock and roll. Even if you listen to an early Elvis Presley record, the rhythm sections are not very loud at all, everyone was actually sort of tip-tapping about. And so The Who were one of the first bands to really start laying it down a bit heavier. They later became unbelievably loud, by using more powerful amps and speakers. But in the early days that wasn’t available to anybody – it was new territory. For them and for me and others like me. It certainly wasn’t difficult to do, it was fun trying to figure it out. 3

1 Love the One You’re With

2 Exile

3 Maximum Who

4 Faces, 1969–75

5 The Beach Boys

6 The Producer Tapes

7 I-Contact

8 A Guide to the Labyrinth

9 Definitely

10 Jimmy Page: The Anthology

11 This Is Our Life

12 Love That Burns

RONNIE WOOD Glyn Johns and I used to argue a lot in the studio at Olympic in Barnes. I used to have certain ideas that I wanted to come across, and he’d come down on me and we’d get physical. And there’d be the Stones in the next studio or David Bowie in Studio 3. So if I was fed up with the session, I’d walk into the next room … I played on a few of David’s albums; I’d just walk into the next studio and he’d say, ‘Hey, Ron, play on this for me.’ 4

KENNEY JONES [The Faces] never, ever used any sound effects. There were no harmonisers on voices, there was nothing like that. Just mic everything up, play it – bang! 4

ALICE COOPER The truth about records that come out today is that they are just too mechanical. They sound like they’re being pushed out through a computer and there’s no heart to it. The artist is losing the real voice because of technology. 6

BRIAN WILSON It’s not like it was in the Sixties when we didn’t have computers. Why I like it better now is that we have more time to examine the sound of the voices, to get the voices to sound right. Recording now you can also correct the pitch, extend the bars longer, and you can do so many new things. 5

JIMMY PAGE I liked the idea of doing home experiments. If I hadn’t a home studio, I probably wouldn’t have been able to illustrate all the parts and orchestration of ‘Ten Years Gone’ or ‘The Rain Song’ or the instrumental ‘Swan Song’. Having my own studio gave me the space to stretch out and extend the orchestration. 10

BRIAN WILSON I had a den in my house on Bellagio Road where we built a recording studio in 1967. It was a fantastic studio. 5

BRUCE JOHNSTON I assume, for Brian, it was a softer landing to work in his home. I have a memory of Brian’s wife, who would endlessly chase us all out of the kitchen for raiding her huge fridge! 5

ROB BAKER Going away someplace where you live and record creates a natural focus. It’s a sacrifice, but everyone’s making the same sacrifice so you feel like a team. 11

MICK FLEETWOOD I always loved the idea of having a music studio under my own roof. My first attempt at creating one was when I lived in a small apartment on Kensington High Street in London with my girlfriend, Jenny Boyd. Andy Silvester from Chicken Shack had rented the room upstairs, and he helped me configure my tiny spare room into a studio. We put up egg cartons and carpet on the walls for soundproofing. Andy set up tape recorders. We used it more as a rehearsal room than a studio. I remember working on ‘Jigsaw Puzzle Blues’ and ‘World in Harmony’ in there. Later on, Fleetwood Mac would emulate the bigger bands like Traffic and Led Zeppelin by recording out in the middle of nowhere in old country houses. 12

JIMMY PAGE By our fourth album I had the idea that we should find a residential location, somewhere quite isolated, where bands rehearsed in the past without neighbours complaining about the noise. If it was a place where you could actually stay in residence, theoretically we should be able to come up with a really substantial body of work, namely an album. And that album would contain all the concentrated energy of the particular time and place.

I was told about a house in Hampshire called Headley Grange where Fleetwood Mac had rehearsed, but no one had actually recorded there. I thought, well if you can rehearse without complaints, then recording shouldn’t be a problem either.

As well as becoming our studio and home, Headley was also a really productive workshop. We created so many songs from scratch there, like ‘Rock and Roll’, ‘The Battle of Evermore’, ‘Misty Mountain Hop’ and ‘Going to California’. We only had a certain number of days booked, so when we weren’t playing we’d be having our meals, then sleeping, then getting right back to playing. That work ethic of eat, sleep, music was something that I applied to later albums, particularly Presence.

If that fourth album had been recorded anywhere other than Headley Grange, it would have sounded completely different, and the material would have been substantially different, too. Things turned out just as I hoped they would; the character of the house was imbued in the recordings. We used all manner of sonic dimensions of the rooms, even putting amplifiers in cupboards and things like that. The whole house was really invaded and we must have left some energy behind, that’s for sure. 10

DAVE ‘BILLY RAY’ KOSTER

One of the reasons [The Tragically Hip] bought the Bathouse was to be able to make records without having to rent a studio, which cost so much money. But by the time Music @ Work rolled around, the convenience of being only 20 minutes away from home, not having to spend the night away, being able to go out and get milk and a loaf of bread, meant that home life was beginning to intertwine with work life in a big way. Instead of there being a group of guys on a mission to make a record, now families came into play and trying to get everyone on the same page became more and more difficult. Being in your own studio, the clock wasn’t ticking like it would be if you were renting a studio for 12 days, and that wasn’t great for productivity.

It got to a point where they had to start going to other studios again. If the lid’s not on the pressure cooker, then the meal’s not getting cooked. You’re just blowing steam into the air all day long, every day. 11

JOHNNY FAY The first couple of records we did in Bath were good, but it started to become just too convenient. Sessions didn’t start until twelve o’clock and then that turned into one, then two, then three. When we finally got started, we only had an hour before dinner and we really didn’t get as much work done as we had hoped. Going away is always the best. You’re in the studio at eleven and tracking by twelve and then you’re on your way. 11

GORD DOWNIE

We had concerns, obviously, about how we would respond without a referee, nurse, psychiatrist, doctor, ship captain – whatever you want to call a producer. We were afraid maybe about ego concerns and certain problems. And, in fact, it was the opposite. We really enjoyed the individual responsibility. I think something that most musicians can relate to is, after a certain amount of time, you really enjoy responsibility. We really responded and we worked really hard. 11

ROB BAKER We were lucky because we had Mark Vreeken, who was a world-class, topof-the-line engineer, so we didn’t have to worry about that end of it. But it did unleash a bit of a beast. When you get into self-production, someone has to make the calls. The reason bands have producers is so that no one in the band has to take that role, because whoever does take it ends up getting resented and other people feel sidelined. You need that outside voice – someone whose ego is not involved in the creative process in the same way that yours is – to say what’s working and what’s not cutting it. 11

1 Love the One You’re With

2 Exile

3 Maximum Who

4 Faces, 1969–75

5 The Beach Boys

6 The Producer Tapes

7 I-Contact

8 A Guide to the Labyrinth

9 Definitely

10 Jimmy Page: The Anthology

11 This Is Our Life

12 Love That Burns

MICK TAYLOR We moved to France in the early part of 1971. I had only joined The Rolling Stones in June 1969. For most of 1970 I seem to remember that we were in the studio or on the road. And when we went to France, we all rented big houses, and the biggest house by far was Keith’s. So somebody came up with the idea to do an album there, which ultimately became Exile on Main St. 2

BILL WYMAN It certainly was an unbelievable place to make a record. We did look for other places before we decided to do it at Keith’s. I personally went to two or three farms, looking for somewhere where we could set up a recording studio. And some of the others went to other places at various times, too. We found some interesting places that could have been used, but I think Keith in the end didn’t want to go anywhere else. 2

DOMINIQUE TARLÉ Ian Stewart had a very strong personality, a very different way of life, and we didn’t see much of him. He had his bedroom at Nellcôte and would look after the instruments. Ian had a job to do. If anyone had any trouble with guitars, drums, amplifiers or anything, they would need his assistance.

He came to the South of France to make the studio as efficient as possible, especially as far as the sound was concerned. Keith had decided that maybe it would be possible to fit the studio downstairs, but because all the rooms in the cellar had some kind of echo, we had to put carpet all over the walls, the ceiling and the floor. So, once he got all the equipment back from the British tour, Ian started to put it all together. In the Volkswagen bus he would go to one of the big stores between Nice and Cannes and buy carpet. It was like buying carpet for a whole house. People were very surprised that we were buying so much. We weren’t buying it for the colour or design but for its thickness. And the very cheapest. 2

MARSHALL CHESS Ian Stewart was pivotal, a major cog in their wheel. He was a steady, calming element in The Rolling Stones. He was a Rolling Stone. 2

MICK McKENNA I was working at Olympic Studios when the idea for the mobile studio was conceived. Essentially, the Stones gave it to Ian Stewart as his project.

The Stones knew for a while that they would have to be tax exiles down in France. They also knew that they had to make an album and that there were virtually no studios in that part of the world. So the need to build a mobile studio came about. There was also a feeling within the band that they needed to get away from the nine-tofive studio routine.

The studio itself was specifically designed on the system used at Olympic. It had a Helios console. These were highly regarded because the electronics were simple, and everyone loved the clean sound that came from the desk. The monitors were four whopping great Tannoy speakers, each about four and a half foot tall, situated in the very narrow width of the truck. 2

ANDY JOHNS It was very difficult communicating with the studio outside while we were downstairs in the house. A few times during the night we’d go up to the mobile studio to listen back to the recordings. That was one of the worst parts of it, being in such a confined space in the basement playing music all night and then having to go into an even more confined space afterwards to listen back to it. I never used to like listening back, not straight afterwards, because it’s too intense. 2

MICK TAYLOR I think only The Rolling Stones could have got away with making a record like that, and certainly the idea of having a mobile studio and taking it wherever you wanted was quite appealing. 2

MICK McKENNA When it was finished, the mobile was a brand-new product and some of Sticky Fingers was recorded on it. There was nothing like it in Europe. It was acoustically treated, had a custom-built console, air conditioning and all the bits and bobs. My personal viewpoint is that the sound that came out on Exile on Main St. was in part due to the set-up of the mobile, to the brilliant engineering of Andy Johns and of course to the ambient sound that came up from the basement in Nellcôte. Without being too scientific about it, I’m not sure exactly how much screening was used down in those rooms, but the resulting Exile sound is almost certainly the product of natural recording of instruments blending together rather than having them individually recorded and mixed together into a mishmash later. 2

PHOTOGRAPHY

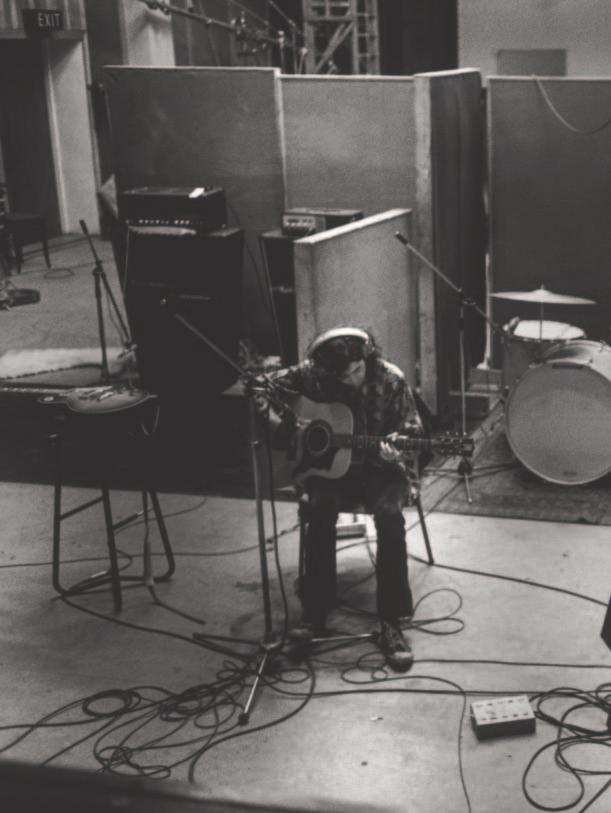

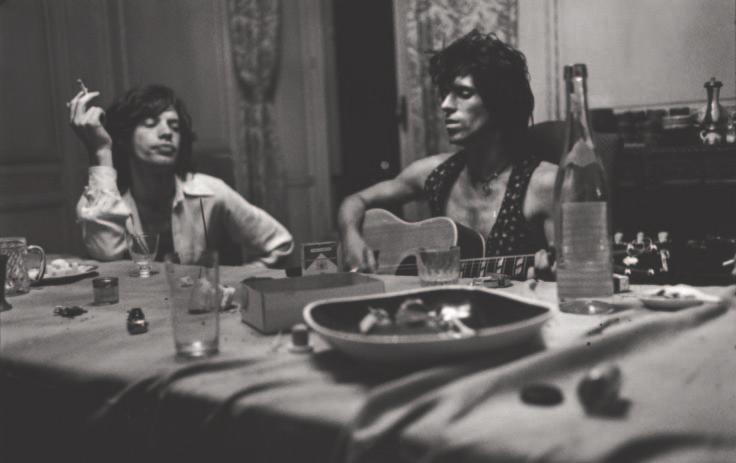

pp.200–201 Jimmy Page in the studio by Dominique Tarlé, taken from Jimmy Page: The Anthology pp.206–7 & 209 The Rolling Stones at Villa Nellcôte by Dominique Tarlé, taken from Exile

KEITH RICHARDS The instrumental work is pretty well the live sound that we got when we recorded the songs in my basement. Except for the little things here and there, the vocals were the only things that we put on afterwards. 2

MARSHALL CHESS Sometimes Mick would write scratch lyrics – like with ‘Good Time Woman’, which later became ‘Tumbling Dice’. And sometimes during breaks Mick and Keith would go off and write lyrics and come and put the vocals on later. 2

ANDY JOHNS When the time came to make the Exile record, I was told it would take about six or seven weeks. So I thought to myself, ‘That will be three months!’ At that time I was working with Eric Clapton on the second Dominos record. He had fired the band but was soldiering on by himself. I didn’t want to stop. So I said to him, ‘I’ve got to do this thing with the Stones. It’ll take six weeks, I reckon.’ It was a little over a year later when we finished. And in those days nobody took a year to do an album. Nobody likes spending three weeks to mow a lawn, if you know what I mean. 2

MICK TAYLOR There was a lot of fun – and frustration, too. There were lots of drugs and I don’t think anybody would be allowed to be that self-indulgent these days and carry on forever and ever making a record.

I knew a lot of the things we were doing were good, but I knew that we were wasting a lot of time as well, and I can’t recall at which point somebody said, ‘That’s it, we’ve got an album,’ and I think we were quite lucky to end up with a double album. For me personally it was a period when the Stones and I got to know each other.

As a record, Exile is quite rough, a bit raw, some of the songs are excellent, some are a little sloppy. But it certainly is a unique album and captured the mood and spirit of that period. It really did. 2

DOMINIQUE TARLÉ When Exile on Main St. came out, the reviews weren’t good. Everyone had expected something like Sticky Fingers with all the instruments perfectly recorded and separated in perfect studio conditions. But out of nowhere came this essentially live album with all the raw energy and sound of a garage band – captured against all the odds in a truck outside a magnificent mansion from the depths of the hot dark cellar below. No one was expecting that from The Rolling Stones.

Now, many followers of the Stones believe this to be their finest hour. For Exile more than any other album holds the most fascination and mystery. 2

DOMINIC LAMBLIN

1 Love the One You’re With

2 Exile

3 Maximum Who

4 Faces, 1969–75

5 The Beach Boys

6 The Producer Tapes

7 I-Contact

8 A Guide to the Labyrinth

9 Definitely

10 Jimmy Page: The Anthology

11 This Is Our Life

12 Love That Burns

When it was released, Exile on Main St. was a total flop. And now it’s said to be the best Stones album ever. We shipped a lot of records by French standards. Nobody wanted it. Firstly, it didn’t have a hit record, because ‘Tumbling Dice’ was a great record, a great song, but not a hit. Remember we were just coming off ‘Brown Sugar’ and ‘Bitch’ off Sticky Fingers. Secondly, it was a double album, which was very unusual then and it made it significantly more expensive. Thirdly, the cover was horrible – then. We’d had Sticky Fingers, the most outrageous and one of the greatest covers in rock and roll history, and then with Exile we had those rather strange photographs which didn’t mean anything to anybody. And then all our communication and promotion was based on the picture of the guy with three eggs in his mouth – the T-shirts, the posters, everything was based on that, so that didn’t help. Exile took almost 20 years to fully mature – like good old English cheddar. 2

PROD

UCING

That George Martin was dubbed ‘the fifth Beatle’ says much about the increased importance and recognition of a producer’s role in record making at the time. Joe Meek was also acknowledged as a pioneering pop artist in his own right and was highly in demand, as was Phil Spector, whose Wall of Sound became a unique feature of his style. Given free rein and an artist’s confidence, a good producer will not just help them realise their vision but also advise as to how their music might be clarified and enhanced, offer fresh perspectives and ward off self-indulgence. However, plenty of artists across the genre spectrum now opt to self-produce, whether with a home set-up or in a professional studio, with software technology making the former ever more popular.

ALICE COOPER I think a producer is the kind of guy that can understand the music, doesn’t get in the way of the band, but has enough authority to be able to tell a John Lennon or a Paul McCartney that something is just going on too long. That takes a lot of nerve.

When you respect a producer, you have to let them have the last word. And the producer has to also be able to back off and realise that it is the artist’s record. It’s not a George Martin record, it’s a Beatles record. 5

RAY COLEMAN Classically trained in composition, conducting, harmony and counterpoint at the Guildhall School of Music, the 36-year-old Martin had also, coincidentally, been taught oboe by Margaret Asher [the mother of Jane Asher, Paul McCartney’s girlfriend/fiancée, 1963–8] . His broad taste would help Paul both practically and inventively to realise the best, and the most innovative, twists of sound on many songs. 8

1 Summer of Love

2 Jimmy Page: The Anthology

3 Faces, 1969–75

4 Definitely

5 The Producer Tapes

6 Words of Love

7 The Beach Boys

8 McCartney: Yesterday & Today

GEORGE MARTIN Musicians today take it for granted that if they are overdubbing, their basic track never varies in its tempo; but [when I was recording with The Beatles] our rhythm track would vary even from one bar to another! It was not much out of time, but enough to make life hell if you were trying to fit something to it. Having said all that, I believe that Ringo’s drumming on [‘Strawberry Fields Forever’] is some of his best. His quirky figures accented it in exactly the right way from the outset, complementing John’s phrases beautifully throughout all the changes the song underwent.

Mixing a four-track master really should not be too difficult. These days, with 48 tracks as the norm, mixing becomes as much of a performance as the original recording, and it can take longer. But with four tracks, basic balances have already been achieved in the recording and dubbing processes. We had been mixing our chosen best tracks as we went along. With all the variations that ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ had thrown up, though, John could not make up his mind which of our performances he preferred. He had long since dismissed the original statement of the song on Take 1, and was now torn between the slow, contemplative version and the frantic, percussive powerhouse, cello and brass arrangement of Take 26.

Ever the idealist, and completely without regard for practical problems, John said to me, ‘I like them both. Why don’t we join them together? You could start with Take 7 and move to Take 20 halfway through to get the grandstand finish.’ ‘Brilliant!’ I replied. ‘There are only two things wrong with that: the takes are in completely different keys, a whole tone apart; and they have wildly different tempos. Other than that, there should be no problem!’ John smiled at my sarcasm with the tolerance of a grown-up placating a child. ‘Well, George,’ he said laconically, ‘I’m sure you can fix it, can’t you?’ Whereupon he turned on his heel and walked away. I looked over at Geoff Emerick and groaned. Every time I go on about the primitive state of recording technology in the midSixties, I feel like Baron von Richthofen describing the Fokker Triplane to a group of Concorde pilots. The standard equipment used for recording Sgt. Pepper included Studer four-tracks, made in Switzerland, with one-inch wide tape mixed down on BTR twin tracks. We had Fairchild compressors that we still have today – awfully good and valve-operated. Neumann microphones were used where possible because they were just coming out then. And, of course, the old, antiquated EMI desk in Studio Two, which was primitive, but the main thing was that it was clean. 1

RAY COLEMAN A man with such an orthodox background in music might have found The Beatles’ primitive instincts abhorrent, for they challenged all traditional approaches to record-making from the start. But Martin’s response was always patient, his benign style concealing a quicksilver mind. His willingness to adapt was valued by The Beatles. 8

CILLA BLACK George Martin is an icon. He really is a national treasure. He reigned at the top and he’s had such a varied career, not only in music. I think he’s just a wizard of talents, he’s just so multifaceted. He makes the best of everything. He’s incredibly British, terribly still, stiff, stiff upper lip. No, not frightened. You know, who dares wins? And he said he certainly did. He dared and won. It’s fantastic. 5

ALICE COOPER To a rock band George Martin is the standard. Everybody is compared to George Martin in the way bands are compared to The Beatles. So working with George Martin may be one of the most nerve-racking things I’ve ever gone through. 5

ELTON JOHN When you think of producers you automatically think of George Martin, at least I do, maybe followed by Phil Spector. But George Martin is probably the greatest record producer that ever lived. And he’s been around from the Fifties onwards. He was the person that I trusted. And he’s a man who I knew would get it. 5

JIMMY PAGE In 2011, I received an award from the APRS [Association of Professional Recording Services] for my work as a producer, at an event hosted by Sir George Martin. It’s an honour to be given any award and they all have their own significance but this one meant a great deal because it came from my peers. And, in the recording world, they don’t come much higher than Sir George Martin. It was an honour sitting with Sir George and Lady Judy Martin. In my acceptance speech I paid tribute to producer Glyn Johns, who was present at the event: for his assistance, putting me forwards for sessions in the early years, and for the exemplary job he did on the engineering of Led Zeppelin’s first album. 2

KENNEY JONES In The Small Faces we produced everything and Glyn Johns was the engineer so we worked closely with him. By the time we got to The Faces, Glyn was a well sought-after producer, producing The Eagles, Clapton and various other bands. 3

IAN McLAGAN He’s amazing to work with. Glyn Johns was a big part of our sound and not to be forgotten. It was difficult to replicate a live sound in the studio. But when Glyn Johns started producing us on the last two albums he found a way. He would walk into the studio and listen to the drums, the bass, the guitar and the piano, and he would tweak the amp a little bit or he would say, ‘Turn that down.’ And he would move the mics, on the drums particularly, so that it sounded like the drums he’d just heard live. That’s really his secret: he stands behind the drummer to hear how the drum set sounds in the studio and replicates that. A lot of engineers and producers try to get a sound in the control room that they haven’t even heard yet. But Glyn would ask, ‘How does it sound out there? Why does the drummer play like that?’ His way of mic-ing drums is now a standard; it’s known as the ‘Glyn Johns Method’. It’s quite mathematic and exact and involves only four mics. 3

GEORGE MARTIN Nowadays getting massive volume on a track is simply a matter of pushing up a fader; in those days it was a real problem. The louder you could make that type of pop record, the more impact it was likely to have, and of course the better it was likely to sell. A disc jockey would put on one of these roaring records, and it would knock his socks off. You, the listener, would hear it over the radio for the first time and it would knock your socks off. Out you would go to the record store and buy it. That’s the business.

Getting maximum volume out of those grooves became my major preoccupation. I used to wake up in the middle of the night, thinking about it. Volume! That great sound! I did succeed in getting some of that loudness into the early Beatles records, but I wanted more, much more. And the boys were snapping at my heels. They could hear the difference in the US imports just as well as I could. ‘Why can’t we get it like that, George?’ they would chorus. ‘We want it like that!’ Well, why couldn’t I get it like that? It was because of things like cutting the bass sound on to a disc in such a way that the needle stayed firmly in the groove when it was played but gave you plenty of thump; it was getting the correct equalisation of frequency (eq) between the guitars, drums and bass. It was miking the drums well, too: before The Beatles many groups didn’t put a microphone on the bass drum. They would put a mic about four feet away from the drums, pointing in the general direction of them, and hope for the best; ditto the bass

1 Summer of Love

2 Jimmy Page: The Anthology

3 Faces, 1969–75

4 Definitely

5 The Producer Tapes

6 Words of Love

7 The Beach Boys

8 McCartney: Yesterday & Today

guitar (there was no direct injection of the guitar into the recording console then, of course). Paul insisted that we get a really good bass sound, and I realised that we would have to make sure and mic his bass up much better, much closer than was normal practice then. So we taught each other what was required, The Beatles and I. We groped our way jointly towards an exciting sound. 1

JERRY ‘J.I.’ ALLISON Buddy Holly was a great record producer. He was a talented dude. I mean, he discovered Waylon [Jennings] and produced some of his records. 6

PETER ASHER Buddy was fascinated by the making of records and very innovative in the studio. The records, especially the self-produced ones, feature quite abnormal drum parts. They’re so cool. A typical producer’s instinct would have been to put regular old rock and roll drums on any of those songs, but he persisted in an original aesthetic for his whole career. 6

EDNA GUNDERSEN He recorded the vocal and doubled up the tape for ‘Words of Love’ so it thickened the vocal, a studio technique that made the sound richer. It made the recording match the sound he had in his head, it was like what he did with reverb and echo in the studio. This was primitive equipment, too, so he was very smart in making the most out of what you could with the simplest of recording tools. 6

DESMOND CHILD As a producer I come from the Phil Spector school of the Wall of Sound, so my records sound enormous, which makes making a record that has few elements but feels complete difficult. That’s what Buddy Holly was an expert in; every part was perfect. He mastered the art of reduction to the simplest elements and that’s one of the things that makes his music so extraordinary. 6

MIKE LOVE Phil Spector was one of the first to realise the difference between a great song and a great record, his goal being to create an ecstatic aural experience in the studio through the unconventional blending of instruments. 7

BRUCE JOHNSTON Back when I first worked with Phil Spector in the late Fifties, I knew he was unique and plugged into the pop music future. He’d play demos of his songs for me and Sandy Nelson. Phil was a ‘beyond brilliant’ kind of talent. The only other West Coast person in that early Sixties rarefied atmosphere was Brian Wilson. These two became beyond as good as it gets. 7

BRIAN WILSON I learned by watching engineers and watching people produce, but I think I learned the most from listening to Phil Spector’s records. I still give Spector the credit for being the single most influential producer. He’s timeless. He makes a milestone whenever he goes into the studio. 7

MIKE LOVE Brian was invited to Gold Star to watch Spector, a five-foot-seven ball of rage who bullied his singers relentlessly. Brian thought Spector was scary, but he also held him in awe as a man who had redefined the producer’s role: the producer, not the singer or the lyricist, was the star. 7

BRIAN WILSON I was unable to really think as a producer until I got familiar with Spector’s work, then I started to see the point of making records. You’re in the business to create a record. So you design the experience to be a record rather than just a song. It’s great to take a good song and work with it, but it’s that record that counts. It’s the record that people listen to. 7

ANDY SUMMERS For me, a really good producer should be a great musician first. You’ve got to be better than an average musician. Then you’ve got to be totally on top of studio techniques. 5

STEVE CLARK Mutt Lange is one of the best producers in rock. Most producers can’t explain something from a musician’s point of view. Mutt is a trained musician himself and he will change an arrangement around himself if it’s not right. At the same time, he is able to put himself into a record buyer’s position. When you’re working with Mutt you come out of the studio a better musician. This helps when you’re playing a concert because now you know the songs inside out and as a result it makes your guitar playing much better. 4

PHIL COLLEN Working with Mutt is like going into a class where someone’s letting you in on all these amazing secrets. He’s the most intelligent person I’ve ever met in my life. You wouldn’t know it immediately. It’s like peeling an onion. He’ll start talking quite normally and then he’ll go deeper and deeper until you start thinking, ‘Shit! This is above my pay grade.’ He’s a huge fan of all kinds of music. He grew up in South Africa and he made pop music there. He’d done AC/DC albums and he’s always loved country music, so he would combine all these different styles. Mutt taught us to hear the thread connecting Top 40 songs of different eras. I still do it now – picking out the themes that link The Jonas Brothers, Ariana Grande, Drake or whatever to the hits I used to love in 1973. It’s knowing how to listen without prejudice. 4

GEORGE MARTIN The way we worked, the creative process we always went through, reminds me of a film I once saw of Picasso at work, painting on a ground-glass screen. A camera photographed his brushwork from behind the screen, so that the paint appeared as if by magic. Using time-lapse photography you could see first his original construction, then the complete change as he applied the next layer of paint, then the whole thing revitalised again as he added here, took away there. It reached a point where you thought, ‘That’s wonderful, for heaven’s sake stop!’ But he didn’t, he went on, and on. Eventually he laid down his brush, satisfied. Or was he? I wonder how many of his paintings he would have wanted to do again. It was a fascinating film of a great artist, of a brilliant creative mind at work. And I have often thought how similar his method of painting was to our way of recording. We, too, would add and subtract, overlaying and underscoring within the limitations of our primitive four-track tape. There were many things we abandoned or taped over: the first take of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ is a good example. It was great, but we ditched it outright. It could be greater still. Then there is the end section of the orchestrated version of the song, where the rhythm is too loose to use. In spite of all our editing, I just could not get a unified take with complete synchronicity throughout. The obvious answer would have been to fade out the take before the beat goes haywire. But that would have meant discarding one of my favourite bits, which included some great trumpet and guitar playing, as well as the magical random mellotronic note-waterfall John had come up with. It was a section brimming with energy, and I was determined to keep it.

We did the only thing possible – we faded the song right out just before the point where the rhythm goes to pieces, so the listener would think it was all over, then gradually faded it back up again, bringing back our glorious finale. It was our own little bit of Picasso technique, a dab on the canvas that we managed to rub out, leaving behind an exotic touch of colour. 1