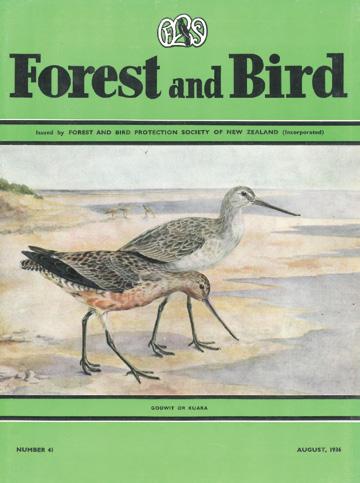

NEW ZEALAND’S INDEPENDENT VOICE FOR NATURE • EST. 1923 SPECIAL ISSUE Centennial TE REO O TE TAIAO ForestBird and № 387 AUTUMN 2023

COVER

PAPER ENVELOPE

EDITOR Caroline Wood E editor@forestandbird.org.nz

ART DIRECTOR/DESIGNER Rob Di Leva, Dileva Design E rob@dileva.co.nz

PRINTING Webstar www.webstar.co.nz PROOFREADER David Cauchi

ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES Karen Condon T 0275 420 338 E karen.condon@xtra.co.nz

MEMBERSHIP & CIRCULATION T 0800 200 064 E membership@forestandbird.org.nz

Thank you for supporting us! Forest & Bird is New Zealand’s largest and oldest independent conservation charity.

Join today at www.forestandbird.org.nz/joinus or email membership@forestandbird.org.nz or call 0800 200 064

We hope you enjoy this bumper 100th birthday issue with eight extra pages of centennial storytelling. Every member receives four copies of Forest & Bird magazine a year.

Forest & Bird is printed on elemental chlorine-free paper made from FSC® certified wood fibre and pulp from responsible sources.

SHOT Kākā Lily Daff circa 1931. Forest & Bird archives/Alexander Turnbull Library

Pīwauwau rock wren. Jeremy Sanson RENEWAL Pepe para riki common copper butterfly. Donald Laing

Forest & Bird is published quarterly by the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand Inc. Registered at PO Headquarters, Wellington, as a magazine. ISSN 0015-7384 (Print), ISSN 2624-1307 (Online). Copyright: All rights reserved. Opinions expressed by contributors in the magazine are not necessarily those of Forest & Bird. Contents ISSUE 387 • Autumn 2023 Editorial 2 Celebrating our first century 4 Letters + competition winners News 6 Big Birthday Bash and other centennial events 8 Twin causes for celebration 10 Bat boost, Vote Nature 2023 12 Biodiversity project, lifelong legacy, New Caledonia calling, fundraising heroes Cover 14 Back in black 17 Hope in action Freshwater 20 Bring back wetlands 27 Restoring the Ngaruroro Special report 22 Our remarkable southern kaurilands Predator-free NZ 28 Give a Trap! 48 Let’s not forget mice Centennial stories 30 Green shoots 33 Cherish our heritage 45 Perrine Moncrieff’s play Focus on flora 36 Back from the brink Forestry 38 Stop forestry slash Branch project 40 Shorebird sanctuary 52 Plague skinks Opinion 41 Right to repair 64 The degrowth revolution 14 30

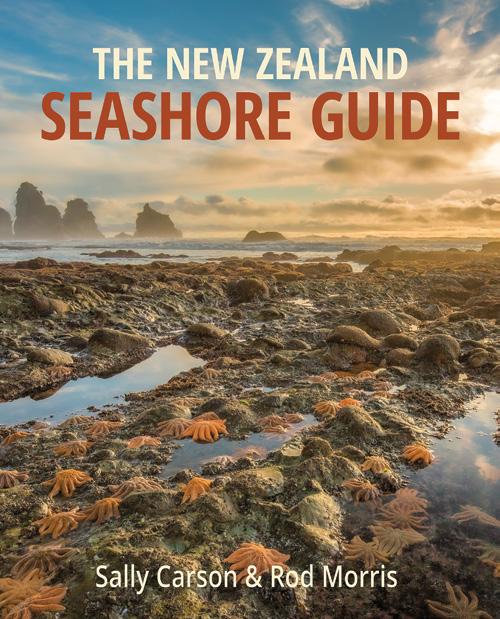

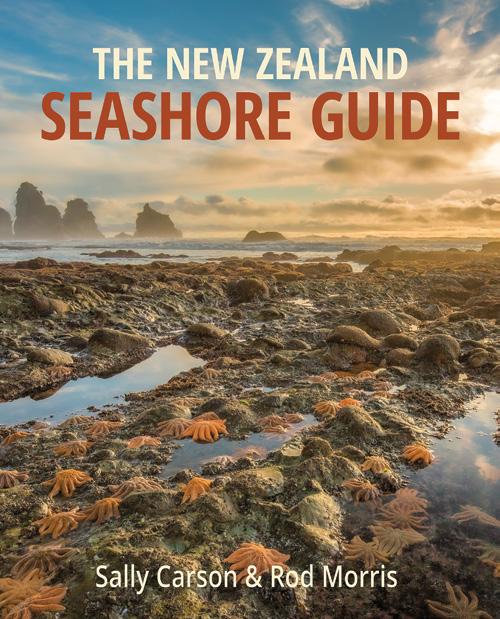

Marine

42 Sponges – seashore treasures

50 New Zealand sea lions

Biodiversity

44 Restoring Rotoiti reserves

46 Falcon family

58 Radical connections

International

50 Time to protect 30%

Birdlife

51 Spotted shags, masters of air, land & sea

CONTACT NATIONAL OFFICE

Forest & Bird National Office

Ground Floor, 205 Victoria Street

Wellington 6011

PO Box 631, Wellington 6140

T 0800 200 064 or 04 385 7374

E office@forestandbird.org.nz

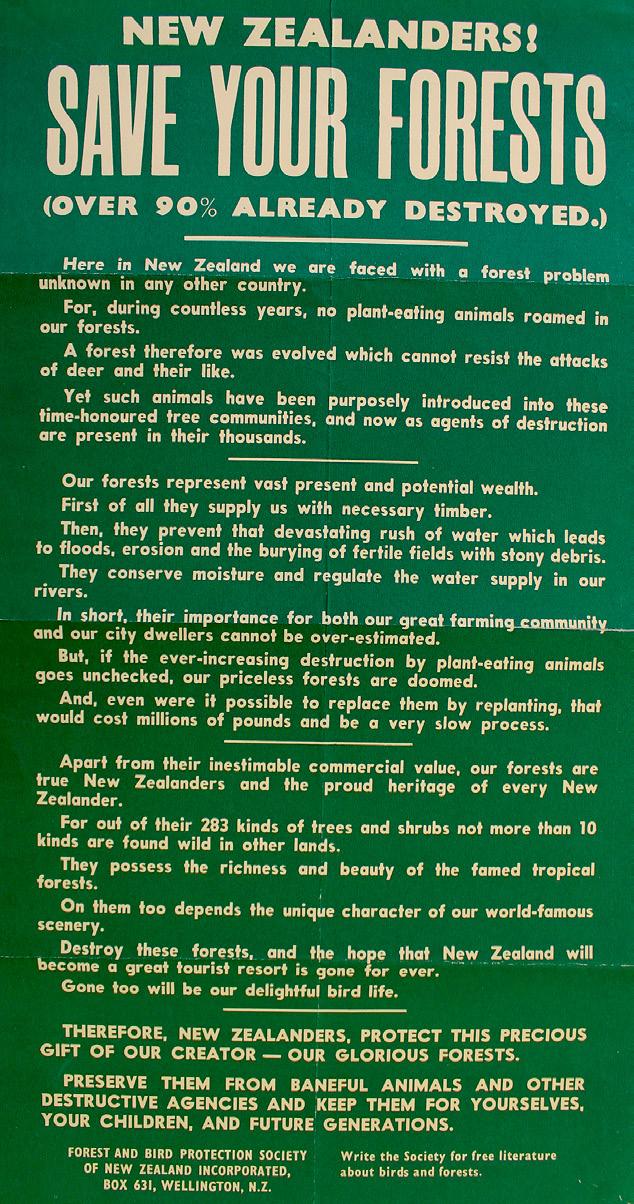

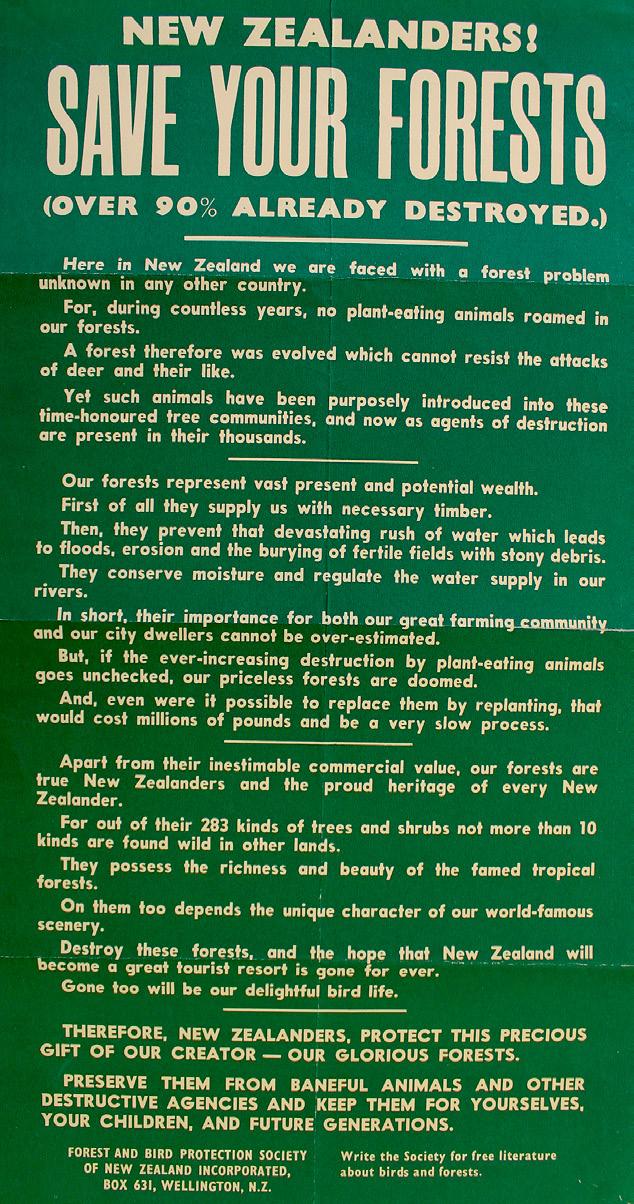

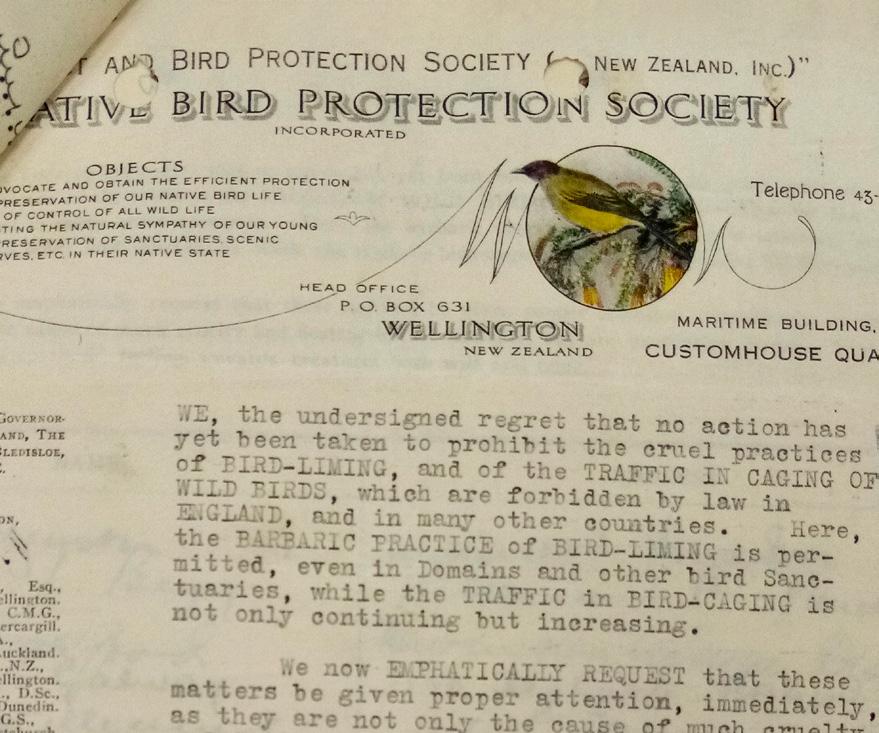

W www.forestandbird.org.nz

CONTACT A BRANCH

See www.forestandbird.org.nz/ branches for a full list of our 50 Forest & Bird branches.

www.facebook.com/ ForestandBird

@forestandbird

@Forest_and_Bird

www.youtube.com/ forestandbird

Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand Inc. Forest & Bird is a registered charitable entity under the Charities Act 2005. Registration No CC26943.

PATRON Her Excellency The Rt Honourable Dame Cindy Kiro, GNZM, QSO Governor-General of New Zealand

CHIEF EXECUTIVE Nicola Toki PRESIDENT Mark Hanger TREASURER Alan Chow BOARD MEMBERS Chris Barker, Kaya Freeman, Kate Graeme, Richard Hursthouse, Ben Kepes, Ines Stäger CONSERVATION AMBASSADORS Sir Alan Mark, Gerry McSweeney, Craig Potton DISTINGUISHED LIFE MEMBERS Graham Bellamy, Ken Catt, Linda Conning, Philip Hart, Joan Leckie, Hon. Sandra Lee-Vercoe, Carole Long, Peter Maddison, Sir Alan Mark, Gerry McSweeney, Craig Potton, Fraser Ross, Eugenie Sage, Guy Salmon, Lesley Shand

the field

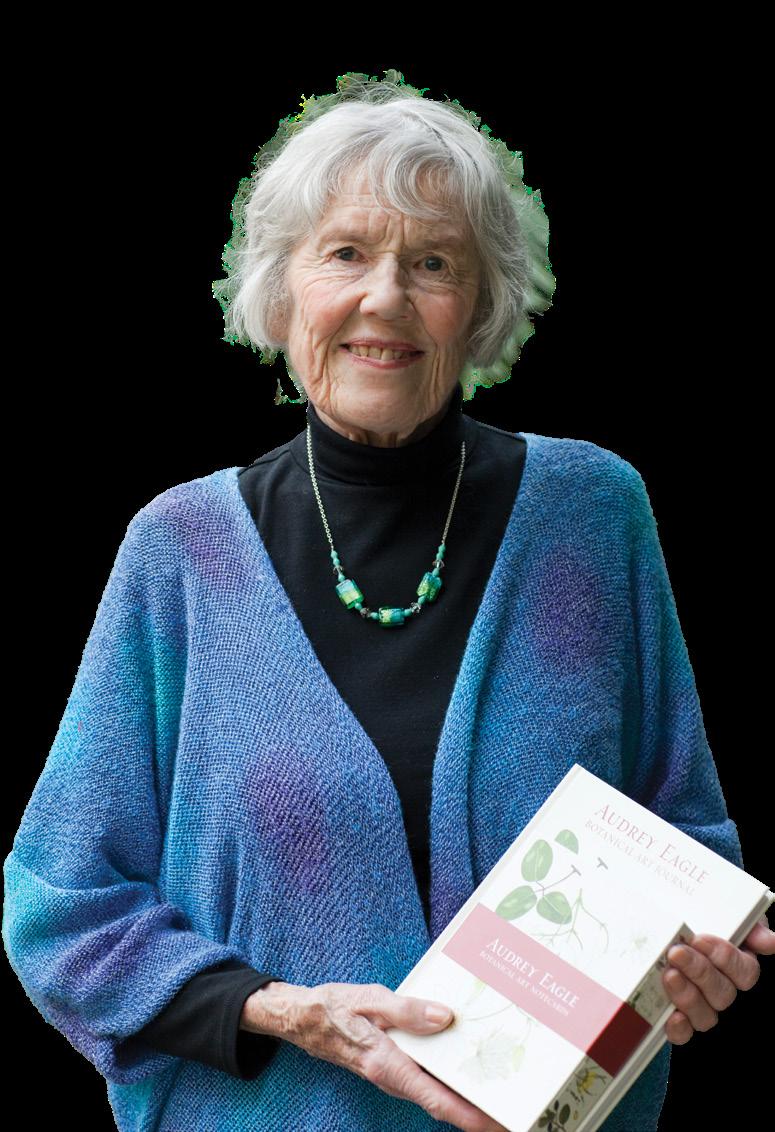

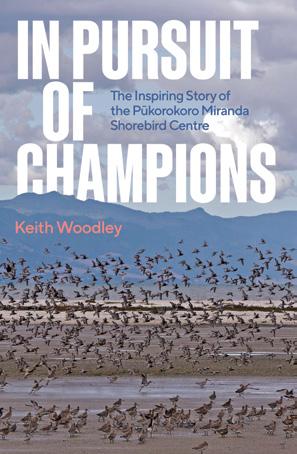

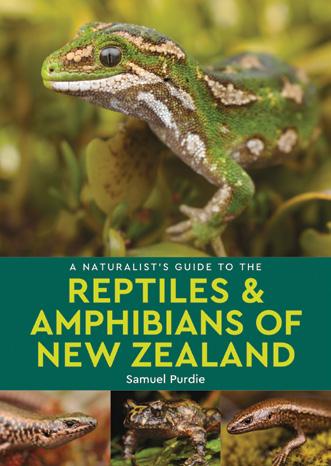

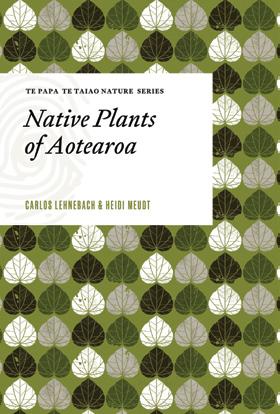

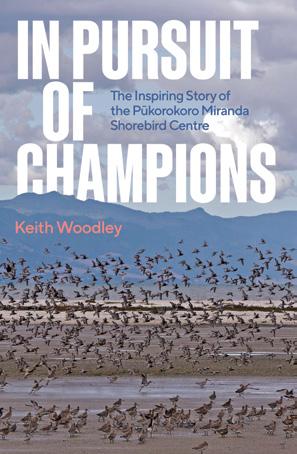

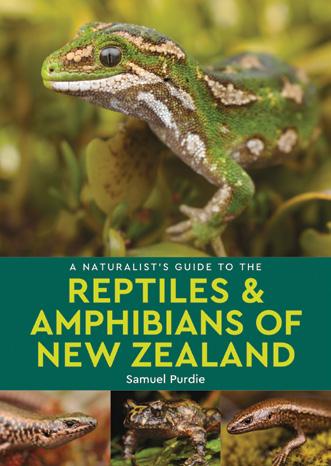

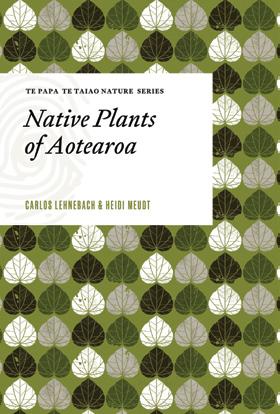

Native cockroaches Our partners 62 Investing in a better planet Forest & Bird project 63 Lenz Reserve: Summer in the Catlins Going places 66 A grand Fiordland tour Obituary 68 Audrey Eagle Books

Autumn book round up Market place

Classifieds

word

Kiwi rescue

shot

Poaka

stilt 42 54

In

54

69

70

Last

72

Parting

IBC

pied

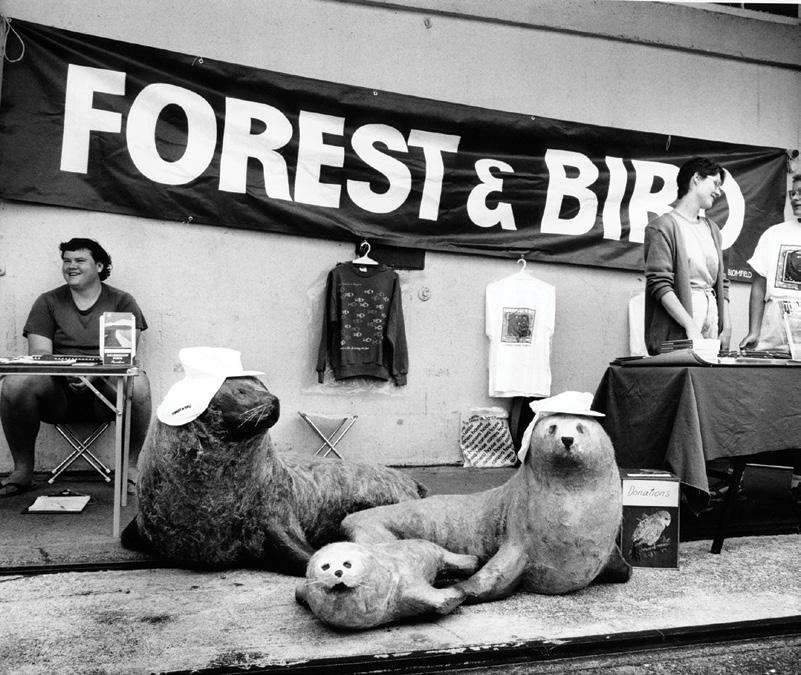

CELEBRATING OUR FIRST CENTURY

Forest & Bird turns 100 later this month, and I’m looking forward to acknowledging the thousands of New Zealanders who have helped achieve so much for nature over the past century.

Without you – and the five generations of donors, volunteers, and staff standing behind you – we wouldn’t be where we are now, a powerful and effective conservation voice.

Since 28 March 1923, we have been working together to advocate strongly for the protection, restoration, and enhancement of Aotearoa New Zealand’s natural heritage.

Earlier this year, I travelled around the country with a tour group from the UK. It was humbling to show them project after project that Forest & Bird has initiated, enabled, or grown in every corner of the motu.

The list included conservation projects at Boyle River, central Canterbury, the Makarora Valley, Otago, Ark in

the Park, Tāmaki Makaurau, the Lake Hatuma Bittern project, Hawke’s Bay, and the Violet Bonnington Reserve, Rotorua.

Many of our projects and reserves have existed for decades. All demonstrate Forest & Bird “walking the talk” – showing how it’s possible to protect and restore nature in our own backyards.

These at-place projects show how our volunteers can make a tangible difference for local flora and fauna – by trapping, planting, and weeding.

The dedicated volunteers who led the society in its early years were able to adapt with the times and change direction when needed to maximise their effectiveness.

This is just as important today. It’s vital to keep the end goal in mind, whether it’s of a practical project or a national environmental campaign. This may mean rapidly changing direction in the light of new challenges or technologies.

I know from personal experience how easy it is to become immersed in a project and keep on doing the mahi without pausing to step back every so often to evaluate progress.

The numbers of predators or pest plants removed are measures of hard work. They are not proof that objectives are being achieved.

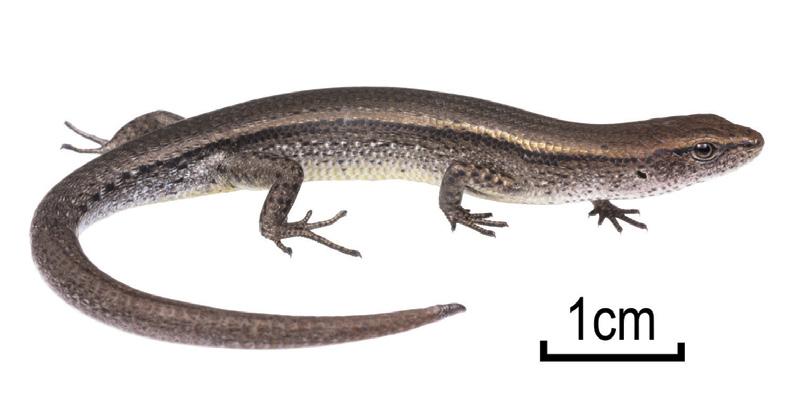

Instead let’s measure positive outcomes – the breeding success of birds, the density of rare lizards, the diversity of tree seedlings, floral abundance in the canopy, or bat sightings per unit of time.

Measures like these can help us evaluate just how valuable our voluntary conservation work is for Aotearoa.

I’m looking forward to coming together in the coming year to celebrate our collective wins, pay tribute to Forest & Bird’s donors and volunteers, and ensure our conservation mahi is fit for purpose for the years ahead.

I hope you enjoy this bumper centennial magazine. Whāia te iti kahurangi, ki te tuohu koe, me he maunga teitei – seek the treasure that you value most dearly, if you bow your head, let it be to a lofty mountain.

EDITORIAL

Ngā manaakitanga

Mark Hanger

Forest & Bird President Perehitini, Te Reo o te Taiao

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 2

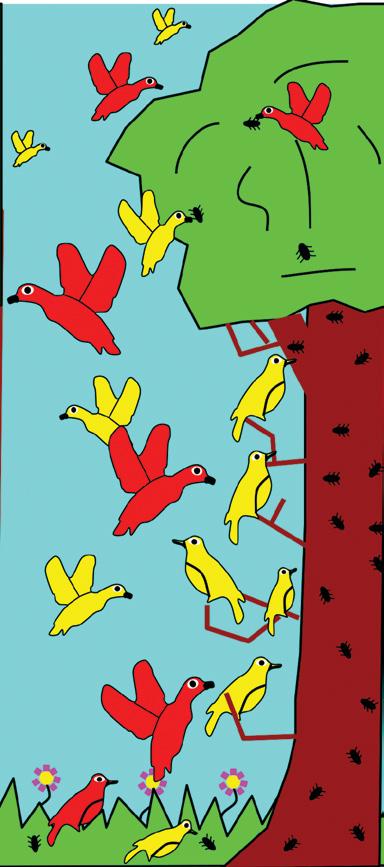

Red and yellow crowned kākāriki. Lily Daff for Forest & Bird, circa 1933

WILDERNESS

JOIN NEW ZEALAND’S EXPEDITION CRUISE PIONEERS EXPLORING THE FURTHEST REACHES OF OUR BACKYARD ON A BUCKET LIST ADVENTURE

Heritage Expeditions are pioneers in environmentally-responsible small ship expedition cruising and industry leaders in sharing stunning natural wonders, incredible cultural exchanges, unforgettable wildlife encounters and wilderness adventures, and exploring historic sites with intrepid travellers. Travel is aboard our purpose-built, luxurious 140-guest expedition flagship Heritage Adventurer and 18-guest expedition yacht Heritage Explorer where guests enjoy sophisticated accommodation, gourmet fare and carefully crafted, unique itineraries led by a renowned team of botanists, ornithologists, naturalists, geologists, historians and experts.

• Snares Crested Penguins, Snipe & Flightless Teal

• Flowering fields of megaherbs

• Sea Lions, Albatross & Coastwatchers history

• Includes excursions & house drinks with lunch & dinner

8 days, 20 Dec 2023

$9,275pp*

• Ports Adventure & Pegasus

• New Zealand’s Amazon Lords River & Paterson Inlet

• Predator-free Ulva Island

• Quirky town centre Oban

• Pearl, Anchorage & Noble Islands

• Granite Domes & Tin Range

• Includes excursions & house drinks

8 days, 10 May, 26 Oct & 2 Nov 2023

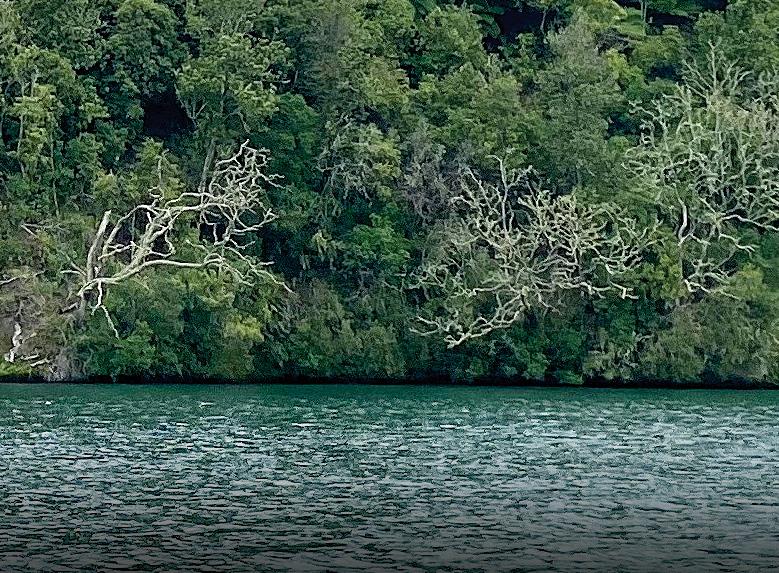

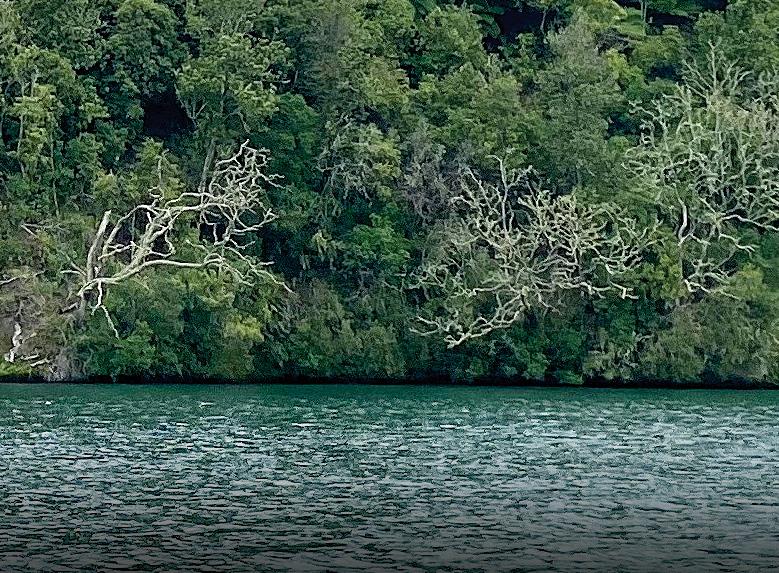

• Milford, Charles, Caswell, Breaksea, George, Doubtful and Dusky Sounds

• Alice Falls, Acheron Passage, Chalky and Preservation Inlets

• Includes excursions & house drinks

10 days, 20 & 30 May, 10 & 20 Jul, 14 & 24 Sep &

3 Oct 2023 $9,495pp**

See our website for more incredible Kiwi adventures! WWW.HERITAGE–EXPEDITIONS.COM

Freephone 0800 262 8873 info@heritage-expeditions.com

© M.

FORGOTTEN ISLANDS ALL OF THE FIORDS

Potter

©

UNSEEN STEWART ISLAND Based on Deck 4 Superior twin share aboard Heritage Adventurer, based on Salvin’s twin share aboard Heritage Explorer.

AWE-INSPIRING

ADVENTURES © L.Thorpe

T.Kraakman

Auckland

Te

$7,195pp** © L.Wilson Queenstown

Anau

LETTERS

YOUR FEEDBACK

Forest & Bird welcomes your thoughts on conservation topics. Please email letters up to 200 words, with your name, home address, and phone number, to editor@forestandbird.org.nz, or by post to the Editor, Forest & Bird magazine, 205 Victoria Street, Wellington 6011, by 1 May 2023. We don’t always have space to publish all letters or use them in full. Opinions expressed on the Letters page are not necessarily those of Forest & Bird.

ROCKIN’ WRENS

A while ago I was reading a book on New Zealand birds, and the section on the rock wren caught my attention – it struck me as such a modest, plucky little bird. As I had grown up in the Mackenzie Country, its habitat appealed. I was delighted at the rock wren’s choice as Bird of the Year 2022 and wrote a couple of poems in celebration. The first a light-hearted piece, the second a representation of the eternal, seasonal patterns of life of high country birds alluding to the threat of introduced predators.

Joanna Fahey, Auckland

You can read Joanna’s ode to hurupounamu On the Rocks right.

MORE GIANTS

BEST LETTER WINNER

There are a couple of giant old rātā right on the Heaphy Track, a few hundred metres downstream of the Heaphy River and Lewis River confluence. They’re well known to DOC and the thousands of people who’ve passed by, pics are easy to find via Google. After reading Giant Discovery (Summer 2022 issue), I checked out the New Zealand Tree Register that was mentioned in the article. I guess that has limited reach as not only are the Heaphy trees not listed but there are no trees at all from northern Westland. The Heaphy rātā are giants too and of course there could be many more away from any tracks. One looks to me to have a 3m+ but maybe not 4m trunk like your Tautuku tree. The other tree leans over and there are no angles to get a good pic of it, but from memory it looks quite a bit bigger and older. It looks similar to your pics of the Tautuku tree.

Tony Ward-Holmes

CAT CONTROL

I’ve read the Time to Talk about Cats article last year and would be very grateful if Forest & Bird would lobby for a Cat Control Act. We have so many cats in our street (suburban Auckland), many not collared, all of them wandering and hunting, that it’s a wonder any birds survive. Our own cat, now dead, and collared

WRITE AND WIN

The best contribution to the Letters page will receive a copy of Ahuahu: A conservation journey in Aotearoa New Zealand by David Towns (Canterbury University Press, RRP $79.99)

when alive, wiped out the copper skinks we had on our property. I was regularly finding them belly up with puncture wounds on their abdomens. The neighbour’s cat frequently killed birds including a tūī and several tauhou silvereyes.

Mike Lloyd, Auckland

FIT FOR FELINES

My cousin keeps her cats contained in the cat garden she built at her home. She also puts them on a harness and takes them for walks. There is no reason to ever let cats roam. She also built a cabin for them to go into in wet weather, joined by a tunnel to the house, to give them a choice. It would be a great business for people to build purpose-built cat gardens.

Gillian Pollock, Nelson-Tasman

EDUCATE DOG OWNERS

As a part time resident of Takapuna, I read with sympathy the letter about dogs on Cheltenham Beach (Summer 2022). Takapuna is a “dead” beach with no wildlife other than the odd fish-and-chip-seeking seagull. It is Queen Street for dogs and the numbers seemed to increase markedly over Covid. No bird would risk trying to breed there – it would be certain death. Sad to hear Cheltenham is heading the same way. I have to accept that Takapuna is beyond repair, but why is there no concern, campaign or education about the damage off-leash dogs can do to wildlife. Dog owners always think their lovely dog would never do any damage. We all like to think that but it is not true. Perhaps people should purchase their dogs with more realistic wildlife friendly/outdoor access expectations from the start. Could the SPCA, dog breeders, vets etc help inform prospective dog owners of their responsibility to the wider environment? Then it won’t be a surprise to them that National Parks and some beaches are out of bounds. Seems obvious that we start at the start and educate rather than, much too late, mitigate.

Karen Grimwade, Auckland

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 4

FUNDING DOC

I’m an ex-farmer and a commercial builder/investor with strong environmental beliefs. Currently in retirement, we have 117 acres that had nearly every invasive weed known and every introduced pest when we bought it 10 years ago. While we continue to have incursion of invasive plants and animals, the property is fundamentally pest-free. If there was something profitable to mine on the property, I would open a mine. There would be a financial reserve kept to reinstate the mine at the end of its life. All profits would be spent on conservation efforts. To my mind, the Department of Conservation should not be funded by the taxpayer (who are terribly overtaxed) but should fund themselves through tourism, having areas of sustainable milling of native trees, mining, and facility leases. I’m sure purists will be weeping blood and gnashing their teeth from my comments, but I say those people are so heavenly minded they are of no earthly use. Profits on conservation land could be huge, that could in turn fund huge conservation efforts. I’m embarrassed as a Kiwi when I see weed and pests on conservation land during my tramping and mountain climbing trips.

Peter Jackson, Franklin

ON THE ROCKS

BY JOANNA FAHEY

Our name is hurupounamu, feathers like greenstone. Which is nice.

Some people call us rock wren –wrong on the wren part, but right on the rock. We’re actually unique. We live in high places: mountains, snow, grass, rocks. Keep to ourselves. We don’t fly much (not much in the way of tail feathers – and it’s dangerous out there) but we flit and bop and hop on grass and rocks –rock, bop, rocketty, rocketty, rock, bop, bop. And if you want to know –our secret name is Xenicus Gilviventris. Which is pretty cool for a very small bird. We rock.

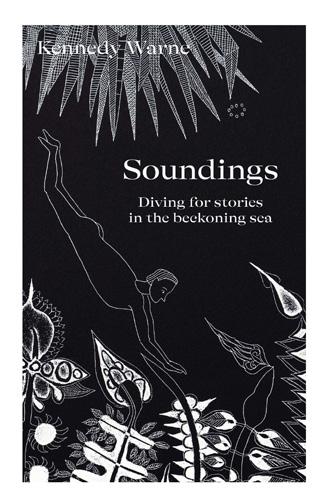

BOOK GIVEAWAY

We are giving away two copies of Soundings, diving for stories in the beckoning sea by Kennedy Warne (Massey University Press RRP $39.99). Warne draws on more than 20 years of fieldwork for National Geographic to share stories about our relationship with the world’s oceans.

To enter, email your entry to draw@forestandbird.org.nz, put SOUNDINGS in the subject line, and include your name and address in the email. Or write your name and address on the back of an envelope and post to SOUNDINGS draw, Forest & Bird, PO Box 631, Wellington 6140. Entries close 1 May 2023.

The winner of our Bumper Book prize pack of 10 new titles published by Potton & Burton was Sue Martin, of Mt Maunganui. The winners of Raising our Chicks by Cushla Thomson McCaughey were Alexander Murphy, of Auckland, and Ross Wilkes, of Wellington.

5 Autumn 2023 |

Rock wren hurupounamu. Jeremy Sanson

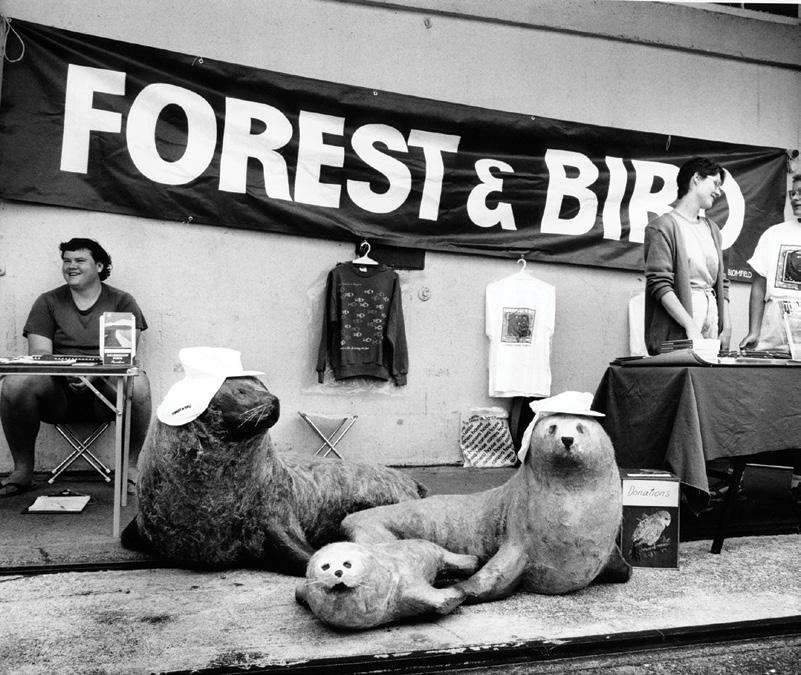

BIG BASH Birthday

Forest & Bird is launching its centennial celebrations with three birthday parties across Aotearoa over the weekend of 25–26 March –we can’t wait to see you there!

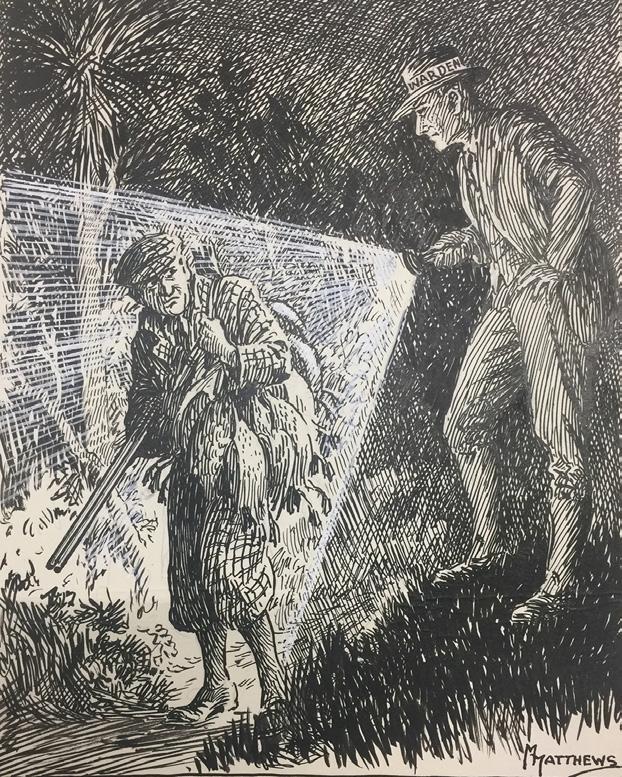

The Big Birthday Bash will be held almost 100 years to the day since a small group of men and women established the Society in Wellington on 28 March 1923.

We will be hosting parties at three of our major projects: Bushy Park Tarapuruhi, Whanganui, Pelorus Bridge Scenic Reserve, Marlborough, and the Lenz Reserve, in the Catlins.

There will be lots for the whole whānau to do, including scavenger hunts, tours of local Forest & Bird reserves, photo competitions, and eating lots of birthday cake.

“The birthday bashes are an opportunity for Kiwis to come together and reflect on 100 years of conservation mahi,” said Forest & Bird’s chief executive Nicola Toki.

“It’s a privilege to share stories about our whakapapa and acknowledge what has been accomplished by so many dedicated volunteers and staff over the past 100 years.

“From Forest & Bird’s earliest days until now, five generations of conservation volunteers have been protecting and restoring our wild

places and wildlife.

“That’s why Forest & Bird is launching Conservation Heroes later this year – as a tribute to nature volunteers past, present, and future.”

Nominations will open in June during National Volunteer Week, and we will be asking you to share the stories of conservation heroes of all ages in your branch or local community that deserve a thank you.

As well as celebrating our 100-year whakapapa, we will also use this big birthday as an opportunity to look forward to the future.

“We are a nation whose lives are shaped by our relationships to the natural world. Te taiao nature is ingrained in New Zealanders’ DNA,” added Nicola.

“Forest & Bird has been at the forefront of hundreds of successful campaigns over the past century that have helped protect our vital connections with the whenua land, awa rivers, and moana oceans.

“Working together will

be critical if we are to find solutions to the two most-pressing global challenges of our generation –climate change and biodiversity loss.”

LATER IN THIS MAGAZINE

• The day Forest & Bird helped buy an island to protect the world’s rarest bird from extinction – see page 14.

• Nature’s heroes – we publish every Old Blue award winner since 1987. Do you recognise any of their names? See page 19.

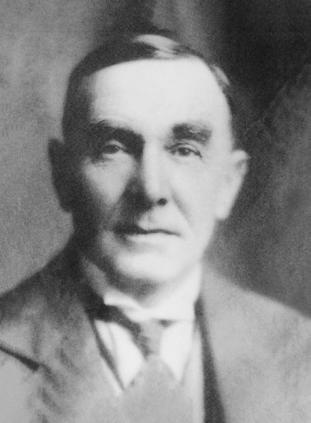

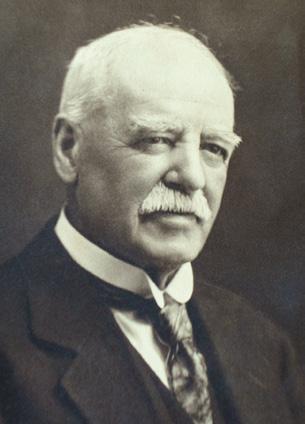

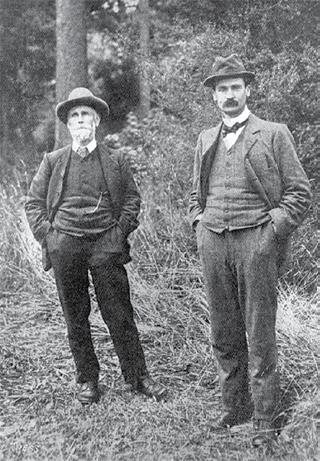

• Sanderson snapshots: the life and times of Val Sanderson, Forest & Bird founder and grandfather of the modern day conservation movement – see page 30.

• Early advocacy and wins: what conservation battles did Forest & Bird fight during its first 25 years –check out page 33.

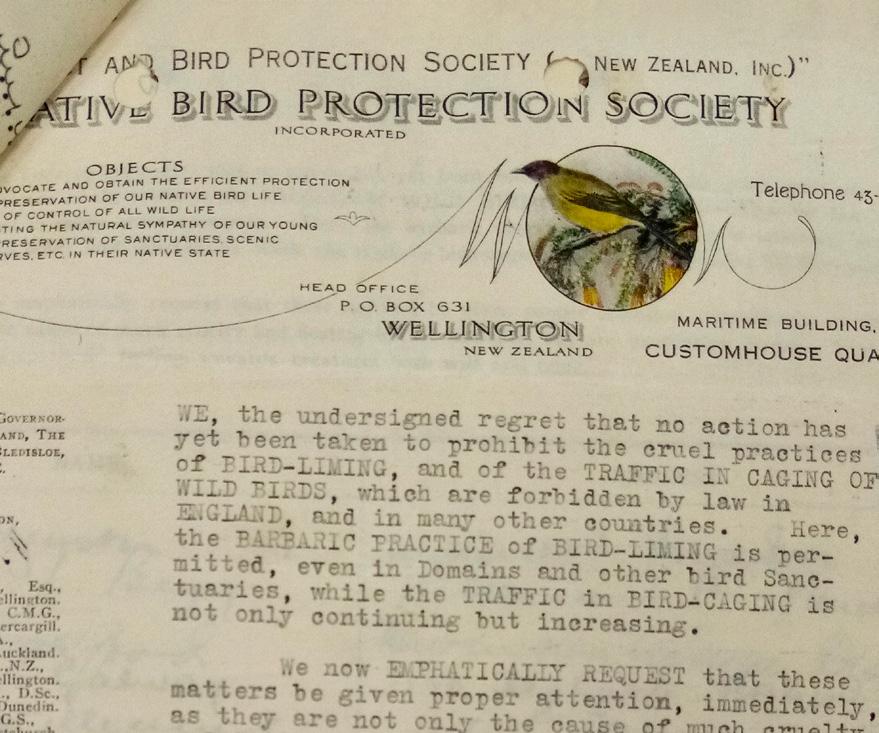

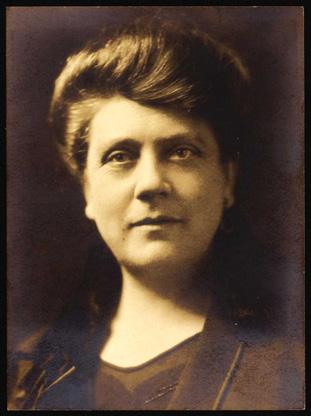

• Forest & Bird founding member and early Force of Nature Perrine Moncrieff is the focus of a new one-woman play –go to page 45.

SAT 25 –SUN 26 MARCH 2023 YEARS 1923–2023 CELEBRATING

NATURE NEWS | Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 6

Korimako bellbird. Tony Whitehead

DATES FOR YOUR DIARY

FORCE OF NATURE CONCERTS

Inspired by Forest & Bird’s work, eight New Zealand composers take us on a journey through our beautiful but fragile natural world. Buy your tickets today!

• Premieres 17 March at the Auckland Arts Festival – see www.aaf.co.nz/ event/force-of-nature

• 2 April, Wanaka Arts Festival –see www.festivalofcolour.co.nz/ programme/force-of-nature

• 3 April, The Piano, Christchurch –see http://bit.ly/3Icf6yV

BIG BIRTHDAY BASH

Join us for a fun nature-themed day out at Bushy Park Tarapuruhi, near Whanganui (Saturday 25 March)

| Pelorus Bridge Scenic Reserve, Marlborough (Sunday 26 March) |

Lenz Reserve, the Catlins (Saturday 25 March). Keep an eye on your inboxes for more information.

SPEAKER SERIES

Forest & Bird will be hosting a monthly in-person conservation speaker event that will also be streamed online. Each month will feature a different nature-related topic, and the series kicks off on 21 March with an event marking International Day of Forests. The speakers will share their expertise and stories about our native forests.

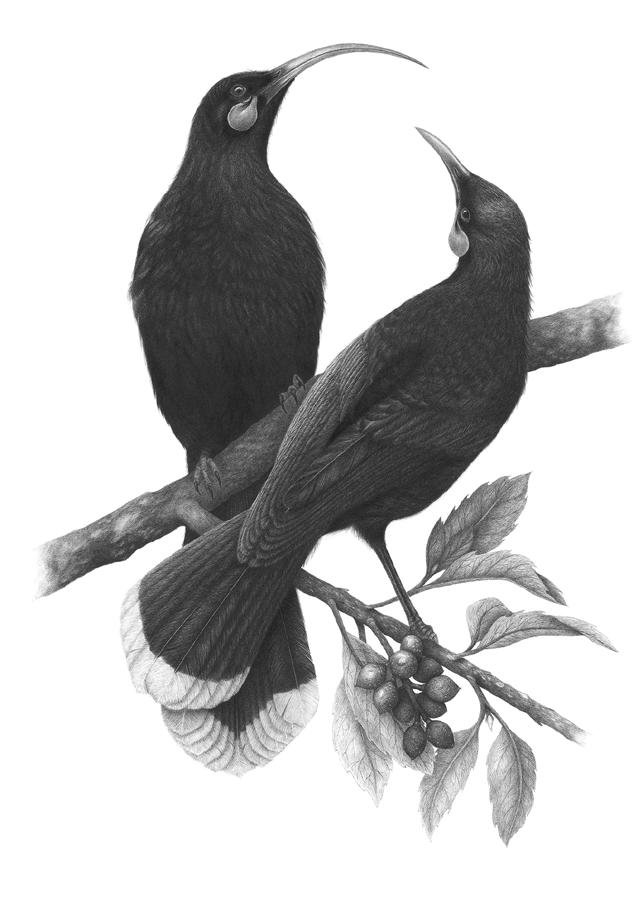

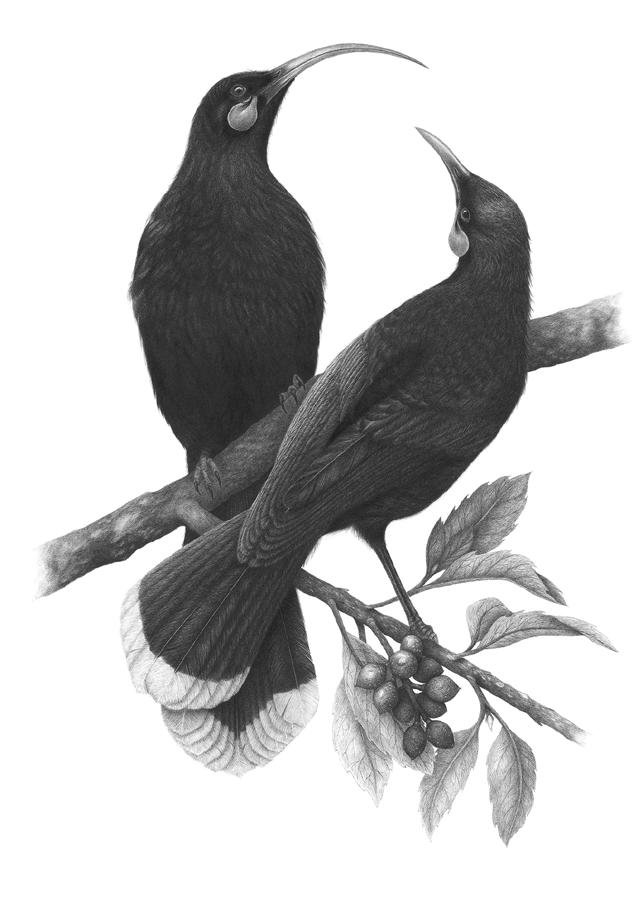

CENTENNIAL STAMPS

NZ Post will launch four stamps and merchandise to celebrate a century of conservation. Created in collaboration with Forest & Bird and Wellington wildlife artist Rachel Walker, the stunning designs feature four landscapes and their flora and fauna. The official launch takes place on 5 April at Otari Wilton Bush, once home to Forest & Bird VicePresident Dr Leonard Cockayne.

SANDERSON WAY & EXHIBITION

The Paekākāriki community and our chief executive Nicola Toki will be gathering at St Peter’s Hall on Saturday 29 April to pay tribute to Captain Ernest “Val”Sanderson, who lived in the village. Part of the local restored Waikākāriki wetland will be renamed Sanderson Way, and a sign about his life will be unveiled. The weekend exhibition (29-30 April) Inspired by Sanderson is a collaboration with the Paekākāriki Station Museum and local conservation groups. We’d like to acknowledge Paul Callister and members of Ngā Uruora for initiating this project.

CENTENNIAL CONFERENCE

After a hiatus of three years, Forest & Bird’s annual conference will be back bigger and better than ever. Join us on Saturday, 29 July 2023 at Te Papa, Wellington, to celebrate a century of conservation mahi and look forward to the next 100 years.

7

Keep up to date with the many centennial events coming up and find out how to get involved, at www.forestandbird.org.nz/centennialcelebrations

Forest & Bird’s staff are looking forward to a year of centennial celebrations. George Hobson

TWIN CAUSES FOR CELEBRATION

New fishing rules are set to be introduced at three coastal marine hotspots in Northland following legal action by Forest & Bird, hapū, and Bay of Islands Maritime Inc.

Two areas will be acknowledged as rāhui tapu, with fishing prohibited around the Mimiwhangata Peninsula, north of Whangārei, and between Maunganui Bay and Oke Bay, in the Bay of Islands. A third area, around Rākaumangamanga Cape Brett, will see a bottom trawling and purse seining ban.

“The newly protected areas will leave a positive legacy of recovery at the exact time when resilience is needed most from a changing climate and ocean,” said Dean Baigent-Mercer, Forest & Bird’s Northland conservation manager.

An Environment Court ruling in November supported a rāhui for both locations. Another court decision finalising the rāhui details was expected at the time of writing.

In 2017, Forest & Bird’s legal team swung into action when Northland Regional Council’s Regional Plan was publicly notified but but lacked sufficient rules to fully protect marine biodiversity.

In appealing the Plan, Forest & Bird worked with kaumātua of Ngāti Kuta and Te Uri o Hikihiki, as well as Northland-based community group Fish Forever.

Our lawyers used precedents established in the Bay of Plenty by the Motiti Rohe Moana Trust’s case, which ruled that regional councils can protect significant native biodiversity in the sea out to 12 nautical miles.

Our campaign to stop new mines being built on conservation land has taken a huge step forward with new legislation on the horizon.

Last year, we called on then Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to fulfil the Labour government’s 2017 promise to end all new mines on conservation land.

Together with our friends at Greenpeace and Coromandel Watchdog, we took a giant yellow banner on a tiki tour around Aotearoa to places threatened by new coal and gold mines.

Your donations helped us reach hundreds of thousands of people and made your voices heard through a powerful combination of lobbying MPs, widespread media coverage, billboard and poster campaigns, and a mass mobilisation on social media.

We’re thrilled to announce everyone’s efforts have paid off. In February, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins committed to drafting a Bill that will put an end to new mines on conservation land.

“This is a huge victory, but our work is far from done,” says George Hobson, who has been coordinating the No New Mines campaign for Forest & Bird.

“At the time of writing, Prime Minister Hipkins had yet to announce when this law will come into effect.

“Forest & Bird remains steadfast in our commitment to carry on reminding the government that New Zealanders want conservation land protected for future generations.”

NATURE NEWS

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 8

Thanks to your generous donations and support, we are delighted to report two recent wins for nature on land and in the ocean.

Maunganui Bay kelp forest. Paihia Dive

9 to 16 Jan 2024

check out our website for additional tour dates

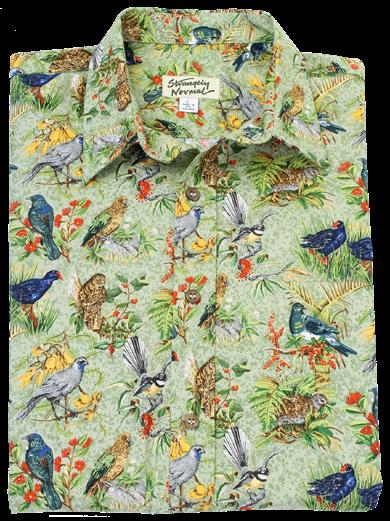

CHATHAM ISLANDS

Highlights

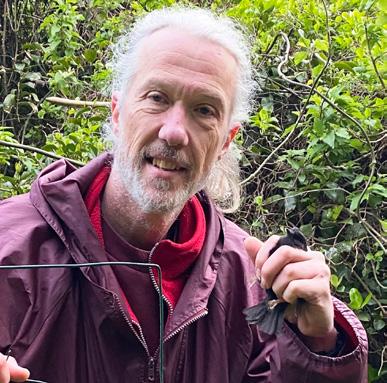

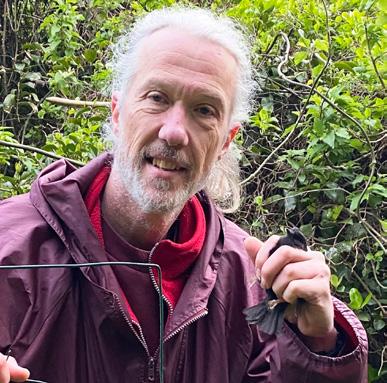

8-day guided tour with ornithologist and conservationist Mike Bell

Discover unique people, history, culture, geology, flora and fauna

Visit Pitt Island nature reserves

Explore outer islands, including SE Island and Mangere from the water

Learn about the Chatham Island Taiko Trust

Price from $7,175pp*.

*The current price per person twin share in NZD. Includes return air travel on Air Chathams, seven nights' accommodation, all meals including continental breakfast / picnic lunches / buffet dinners, all sightseeing and entry fees as per itinerary. Refer to website for full price inclusions & single traveller pricing - www.wildearth-travel.com. Wild Earth Travel has regular Chatham Islands tours throughout the summer season - dates, prices and itineraries will vary.

w w w . w i l d e a r t h - t r a v e l . c o m i n f o @ w i l d e a r t h - t r a v e l . c o m

Mike Bell

TOUR GUIDE

9 Autumn 2023 |

Over the past five summers, Forest & Bird’s Te Hoiere Bat Recovery team has been carrying out monitoring at Pelorus Bridge Scenic Reserve, Marlborough, leading to several exciting discoveries of roost trees.

In January, our field team decided to search for pekepaka maternity roosts, where mothers collectively care for their young, in neighbouring Rai Valley reserves.

Lo and behold, a significant number of roosts were discovered in Ronga Recreation Reserve, with some also found in both the Carluke Reserve and Brown River Reserve areas.

Forest & Bird’s national conservation projects manager Mandy Noffke is thrilled about this significant discovery.

“All indications are that we have two social groups in Te Hoiere Catchment – one in Pelorus and another that frequents the Rai Valley area,” she said.

“Many more years of data are going to be needed to have a better understanding of the

BOOST Bat

population dynamics, but the fact there are multiple thriving colonies is incredibly exciting.”

Pekapeka have long been in decline all over Aotearoa because their habitats are threatened by land use changes, loss of habitat, fragmentation, weeds, and predators.

The 18ha Ronga Reserve is a little known enclave of native bush north of Pelorus Bridge. It’s one of the last remaining podocarp lowland forest remnants to have survived logging and farming.

Led by Michael North,

volunteers from the Nelson Tasman Weedbusters and Forest & Bird’s Nelson-Tasman and Marlborough Branches have been carrying out restoration plantings and weed control there.

The large mature mataī and rimu trees provide ideal roosting habitats, as the monitoring team found out when they went there at night in search of the notoriously difficult-tofind roosts.

At the time of going to print, there were eight confirmed maternity roosts in Ronga, five in Carluke, and two in Brown River. The team

NATURE NEWS | Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 10

Colin Donnell

A colony of pekapeka has been discovered in the Rai Valley, Marlborough, bringing hope for this rarely seen species. Lynn Freeman

Pekapeka long-tailed bat. Ian McGregor

Jen Waite (left) and Grant Maslowski take body measurements and sex the bats. Connor Wallace

Bats were fitted with transmitters so they could be tracked.

also found evidence of bats frequenting the Opouri Valley, 5km from Ronga and high in the Mt Richmond Forest Park.

Unfortunately, this story of hope comes with a significant “but”. One of the roosts filmed using thermal imaging detected two rats on a tree watching as the bats were emerging. Despite their best efforts to catch and kill their prey, this time the rats failed.

Plans are afoot to roll out more predator control to protect these newly discovered roosts, which are located on public conservation land.

Forest & Bird would like to thank the many generous individuals and organisations helping support our bat restoration work at Pelorus, including Marlborough District Council, Jobs for Nature, Lottery Environment and Heritage Committee, Evergreen Trust, and Transpower. We also acknowledge Te Hoiere Project, Kotahitanga mō te Taiao Alliance, and Ngāti Kuia for their continuing support for pekapeka protection in Te Tauihu.

For the past century, Forest & Bird has been the impartial voice for nature in general election years, reminding all political parties of the urgency of protecting our environment.

Nature is at a critical point, and our elected leaders need to take immediate action to save the incredible species and ecosystems that define our national identity.

This election year, Forest & Bird will be working to keep climate, biodiversity, and freshwater issues at the forefront of everyone’s minds, especially those of our political candidates. Join us in our mission to be a voice for nature, and protect the beauty and diversity of our nature heritage for future generations.

Forest & Bird’s Te Hoiere Bat Recovery Project has been working for nearly two decades to protect the precious remnant long-tailed bat population at Pelorus Bridge, in Marlborough.

The Society’s former Top of the South regional manager Debs Martin first stumbled across the bats when she was camping at the Department of Conservation’s picturesque Pelorus Bridge Scenic Reserve campground. Then, in 2005, local Forest & Bird branches started looking for bat populations in the area.

Forest & Bird commissioned a bat survey of the top of the South Island to pinpoint the best location for a restoration project. It discovered only three populations of pekapeka, including the one at Pelorus, which was the most viable. In 2008, the Society launched its first conservation project focused solely on bat recovery.

Since then, local volunteers, including members from our NelsonTasman and Marlborough Branches, have managed a dedicated trapping network at Pelorus to protect and restore bat habitat and breeding sites.

“Working together we can make our environment a priority at this election,” says Geoff Keey, Forest & Bird’s strategic advisor. “Talking to your family and friends, sharing our tweets, Facebook, and Instagram posts, and going to meet candidates or attending election meetings are all ways to make a difference.” Forest & Bird staff will also be supporting branches and youth to organise local “meet the candidates” event focusing on conservation issues.

Forest & Bird’s election campaign will be kicking off soon – keep an eye on your emails. Over the coming months, we will also be providing election resources directly to branches.

11 Autumn 2023 |

Monitoring for long-tailed bats.

Debs Martin

E-DNA DISCOVERY PROJECT

Do you help look after a stream, wetland, or river in a Forest & Bird reserve or project site?

We have some free Wilderlab e-DNA kits to give away and are seeking expressions of interest from branches keen to find out what is living in their freshwater backyards.

Environmental DNA is genetic material shed from living things into water, air, or soil. Samples can be taken from a local river, beach, or reserve and sent to a lab for analysis.

Over the past three years, eDNA has been quietly sparking a change in conservation – and Wilderlab has been at the forefront of making the technology more accessible to New Zealanders.

The company’s eDNA sampling kits and lab-testing service are allowing more conservationists to discover the full range of species living in local waterways, including land-based animals.

This e-DNA project has been generously funded by two of Forest & Bird’s donors who are as passionate about protecting and restoring our streams, wetlands, and lakes as we are!

Forest & Bird’s major projects are taking part too, with kits going to Ark in the Park, Southeast Wildlink, Bushy Park Tarapuruhi, Te Hoiere Bat Project, and the Otago Seabird projects.

We will be sharing the exciting finds in future issues of this magazine.

To register your interest and find out more, email freshwater@forestandbird.org.nz. You can read about Wilderlab’s eDNA technology in our Summer 2022 issue at www.forestandbird.org.nz/resources/poweredna

LIFELONG LEGACY

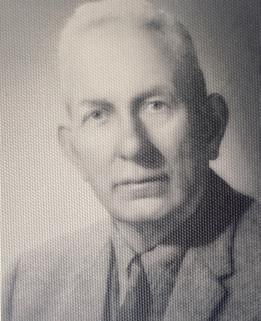

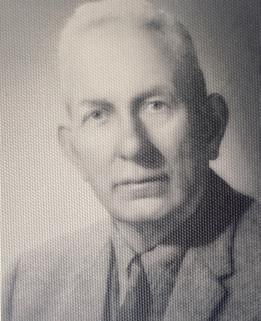

In 1965, Geoff Harrow made a startling discovery that set him on a quest to save a very special seabird endemic to Kaikōura.

A conversation with Kaikōura local, Ivan Hislop, led Geoff, who was a keen mountaineer, to organise an expedition into the remote Kaikōura ranges.

There, at the head of the Kōwhai Valley, he found Hutton’s shearwater breeding burrows. He made it his lifelong mission to better understand and protect the species.

Over following years, Geoff returned to the ranges to discover more tītī shearwater nesting sites and hundreds of thousands of burrows.

In 2008, Geoff established a charitable trust to raise funds to establish up a new nesting site on the Kaikōura Peninsula, working with Whalewatch, Te Runanga o Kaikoura, and the Department of Conservation.

Geoff was a long-standing Forest & Bird supporter, having joined the Society in 1936 aged 10. He received an Old Blue award in 2007 (aged 81) for his outstanding contribution to conservation.

A decade later, he received a Queen’s Service Medal for services to conservation and mountaineering spanning 70 years.

At 88, he said he wanted to “retire gracefully” so he could “wallow peacefully remembering 50 wonderful years with Hutton’s shearwaters”.

Geoff passed away on 16 January in Christchurch, aged 96.

NATURE NEWS

Geoff Harrow in the Kōwhai Valley. Ailsa McGilvary-Howard

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 12

Hutton’s shearwater chick.

NEW CALEDONIA CALLING

Nouméa has all the features you might expect from tropical islands – white sands, blue lagoons, and graceful palms – and is also home to some amazing plants and wildlife.

Never been? Why not join experienced tour guide and naturalist Mark Hanger on a conservation trip of a lifetime to New Caledonia this October while also supporting Forest & Bird.

Mark, who is our President, is running this 14-night Forest & Bird fundraising trip to Nouméa, departing 31 October 2023, plus an optional two-day extension to Île des Pins.

Unlike many Pacific Islands, New Caledonia is an ancient fragment of Gondwana and considered one of the world’s most botanically important hotspots. It is also home to a rich indigenous Melanesian culture.

The island is known for its abundant conifers belonging the ancient plant family Araucariaceae There’s also the chance to see inland rainforests, giant ferns, and a host of endemic birds including the cagou, New Caledonia’s national bird.

The tour includes a visit to a marine sanctuary, where you will explore some fabulous underwater “forests” and time exploring what used to be the world’s largest chromium mine. It’s being restored as a haven for the endemic plants that have evolved to live in the island’s inhospitable mineral-rich soils.

Mark is also running Forest & Bird fundraising tours to West Australia (September 2023), Latitude 42 in (October 2023), Alpine Aotearoa (January 2024), and Te Ao o Tāne (April 2024).

Find out more by contacting Mark Hanger at markhanger@naturequest.co.nz and requesting a brochure.

FUNDRAISING ARTIST

Abig shout out to everyone who supported Te Araroa Trail artist Sarah Adam, who generously donated 20% of proceeds from her recent exhibition at the Depot Gallery, Devonport. Sarah created a painting a day while walking the trail and sold 96 artworks last December, raising a whopping $3,460 for Forest & Bird.

Meanwhile, Alexander Bezzina aka “The lost Hobbit” is running the length of New Zealand (3000km) and aiming to raise $10 per kilometre. All proceeds from his epic run will go towards Forest & Bird’s conservation work, and Alex is aiming to raise $30,000. Please support his incredible efforts here www.givealittle. co.nz/fundraiser/the-lost-hobbit-for-aotearoanzbirdsand-wildlife. You can find out more about why Alex is running for the birds of Aotearoa at www.thelosthobbit.run

Le Poulet (the hen) rock formation near Hienghene. New Caledonia Tourism

Le Poulet (the hen) rock formation near Hienghene. New Caledonia Tourism

13 Autumn 2023 |

BACK IN BLACK

The first translocation of Chatham Island black robins in 20 years is the latest in long-running efforts to ensure they have a bright future.

Holly Taylor and Caroline Wood

Forty years ago, a female Chatham Island black robin called Old Blue held the future of her whānau in her wings. The story of how she helped bring her species back from the brink of extinction became a symbol of hope for nature lovers around the world.

In the 1970s and 80s, conservationists used daring and creative methods to help the species survive and recover, including moving birds between islands and using a foster species to incubate Old Blue’s eggs.

Led by the legendary threatened species expert Don Merton, the successful mission showed how Aotearoa New Zealand could lead the world in island restoration and bird recovery.

Forest & Bird is proud to have played a role in Old Blue’s story,

radius, the largest of which are Chatham Island and Rangiauria Pitt Island.

Black robins, known as karure in ta re Moriori and kakaruia in te reo Māori, currently live in the forest on two small islands.

Rangatira South East Island has about 270 robins, with stable

COVER

Karure | kakaruia | Chatham Island black robin.

Rēkohu Chatham Island

Rangiauria Pitt Island

Rangatira South East Island

Little Mangere

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 14

Mangere Island

Mangere robins, along with the fact that the only other population is near capacity, means a high risk of extinction.

The Department of Conservation decided to launch a recovery effort to secure the future of the species by translocating healthy female robins from Rangatira to Mangere in the hope it will boost the maledominated population.

story of black robin recovery.

“I’ve been involved in reintroductions for 30 years but had never been to the Chathams before, so to be a part of this was a bucket list moment for me,” he said.

The other members of the team included translocation expert Dr Kevin Parker, who led the project, Dr Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes, Erin Patterson, Jemma Welch, Cassidy Solomon (all from DOC’s Chatham Island office), and Bruce Harrison of Auckland Council.

The first nine days of their trip was spent on Rangatira Island, where the team fed and trained the birds, using meal worms to coax them into the traps to get them accustomed to the process.

Given the time of year, the females were constantly pestered by the males, making it difficult for them to feed, and many were initially wary of the traps.

the past two breeding seasons.

“This taonga species represents not just the identity of the entire Chatham Islands community but also a world example of the effort for saving species at risk of extinction.”

Translocations are highly risky for individual birds due to the stresses involved.

Planning began in 2021 with a community and expert workshop held on Rēkohu Wharekauri, the main Chatham Island, which confirmed the need to assist the Mangere population through a topup translocation of 10 females.

A model of the Mangere population developed by ecologist Dr Liz Parlato was a critical component in this process as it showed how, without any intervention, the species could be functionally extinct at this site within four years.

Last September, a specialist team, including Professor Emeritus Doug Armstrong, of Massey University, carried out the first translocation of the species in 20 years to help secure their future survival.

Doug, who is also Oceania Chair of the International Union for Conservation of Nature Conservation Translocation Specialist Group, says it was special to have a role in the world-famous

The female birds were identified using the band colours on their legs. Several months earlier, the juveniles were sexed using DNA extracted from feather samples.

The team managed to catch the 10 females within the first two hours, making for an easier transfer onto the boat for the 45-minute trip to Mangere. The birds were released by early afternoon on the same day.

“The birds we were translocating were descended from Old Blue,” said Dr Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes, who has been monitoring the robins for

After the translocation, the Mangere population was monitored daily, with seven of the 10 translocated females being seen regularly, which is a good sign. Two recently arrived females successfully bred with local males and, at the time of writing, each was raising two chicks.

As Forest & Bird turns 100, Old Blue’s story of survival and recovery resonates as much today as it did half a century ago.

“This black robin was at the centre of one of the most remarkable conservation efforts ever attempted in the world,” said Nicola Toki, Forest & Bird’s chief executive. “It caught the imagination of bird lovers here in Aotearoa and overseas, and showed the power of hope and action in nature conservation.

→

Kevin Parker, Jemma Welch, Cassidy Solomon, Bruce Harrison, Erin Patterson, Doug Armstrong, Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes.

Professor Emeritus Doug Armstrong

The team boarding the robins onto the boat from Rangatira South East Island. Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes

15 Autumn 2023 |

Enzo RodriguezReyes with a Chatham Island black robin.

“Like many New Zealanders, I was incredibly inspired by the story of the black robin when I was growing up, and this story reminds me on a daily basis why we must never give up when it comes to conservation challenges.

“Everyone involved left a huge legacy, and I’d like to pay particular tribute to the Wildlife Service team and the Society’s former presidents Roy Nelson and John Jerram, who were determined to stop this bird going the way of other species that had already become extinct on Rēkohu the Chatham Islands.

“Their courageous actions,

RECHARGE IN THE WILD

Escape the hustle of modern life and sail into the serene on a remote, bespoke adventure into Fiordland. The Breaksea Girl your home in the wild, has all the creature comforts, a small family of expert guides and hosts a collection of multi-day adventures customised to get you closer than ever before.

taken half a century ago, are part of Forest & Bird’s whakapapa, and I’m looking forward to sharing more stories like this as we celebrate 100 years of conservation action all over Aotearoa New Zealand.”

DOC and the local community would like to “rewild” karure | kakaruia to other islands in the future – returning them to places where they once thrived 150 years ago.

It will take time and funds, but the seeds of this ambitious programme were sown with this recent year’s translocation.

experts and the community agreed to progress the establishment of new black robin populations on Rēkohu and Rangihaute Pitt Island. This will reduce the risk of extinction and increase community connection to the species. Before further translocations can happen, one or more sites on the islands must be properly prepared.

This includes setting up predator-exclusion fences and mammalian pest eradications, as well as seeking agreement from the DOC’s treaty partners and community.

It’s an ongoing process in the long continuing fight for population recovery of the black robin. But, with the dedication of the experts involved and the support of the community, the future is looking brighter for Rēkohu black robins.

Let’s buy an island to save a species: Forest & Bird’s role in saving the Chatham Island black

wildfiordland.co.nz

COVER

→ | Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 16

Transporting the robins to Robin Bush, Mangere Island. Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes

KAYAK . SAIL. SNORKEL. FREE DIVE HIKE. WINE. DINE. UNWIND.

Doug Armstrong

HOPE IN ACTION

Once widespread throughout the Chatham Island archipelago, by the late 1870s the endemic black robin was confined to two small islands –Mangere and Little Mangere.

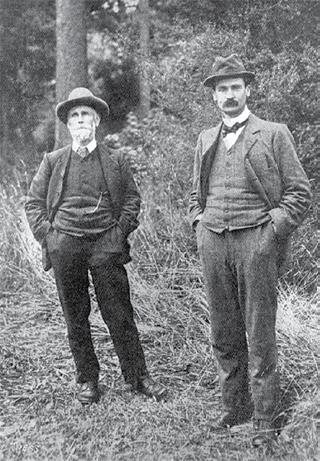

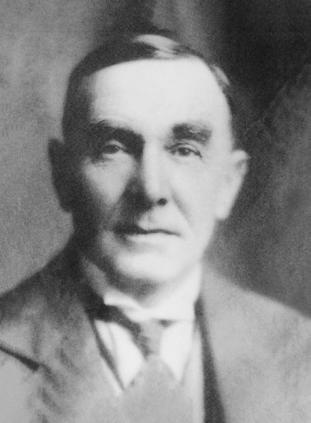

In 1938, a young Charles Fleming was one of the first to raise the alarm about the perilous state of the robins following a visit to Little Mangere Island accompanied by fellow Auckland University student Graham Turbott.

During a death-defying climb up the cliffs of the island, known as Tapuaenuku in Moriori, Fleming and his colleagues “rediscovered” a karure | kakaruia population but estimated there were only 20–35 pairs of black robins left.

They also documented other

rare birds, including Forbes’ parakeet. But there was no sign of the Mangere rail, Chatham Island fernbird, or Chatham Island bellbird, all of whom had already joined the extinction list.

Fleming, who was a great supporter of Forest & Bird’s work and went on to have an illustrious career as an ornithologist and conservationist, proposed protection status for Little Mangere. His series of scientific papers on the birds of the Chathams, published in 1939, remains a major contribution to knowledge of that area today.

In 1956, Forest & Bird published a four-page article in its journal Vanishing Species on the Chatham Islands, written by one of its members, who had visited the previous year.

Dr John Findlay alerted readers to the poor state of flora and fauna unique to the remote archipelago. Much of the damage was being caused by grazing farm stock.

He finished his article by saying “...most Chatham Islanders are nature lovers and would welcome any measure that would help save their wildlife heritage”.

Forest & Bird’s President Roy Nelson penned a strongly worded

editorial next to Findlay’s article listing the plant and bird species that had already become extinct. He called for more botanical reserves to be established.

He also noted the New Zealand Wildlife Service had also raised concerns and recommended at least two areas be set aside “to preserve for all time some of the unique flora found there”.

In 1961, Rangatira South East Island was gazetted a nature sanctuary and became sheep free. Once the browsing mammals had been removed, the indigenous habitat bounced back, showing it was possible to restore the bird’s habitat once pests were removed.

Meanwhile, on Mangere Island, “bush birds and petrels” had almost disappeared, according to a Lands and Survey Department report, most likely victims of the cats that had been liberated to control rabbits.

Roy Nelson wrote to Lands and Survey in 1963 setting out the many grounds that existed for making Mangere Island a wildlife sanctuary that could potentially receive transfers of endangered birds, including black robins, from Little Mangere.

He offered to help fund the island’s purchase, and, after some negotiation, Forest & Bird donated £2,000 (the equivalent of nearly $100,000 in today’s money).

Fearing the Chatham Island robin was in perilous danger, three generations of conservationists battled to save them. Caroline Wood

The view toward Little Mangere Island from the summit of Mangere

Island.

→

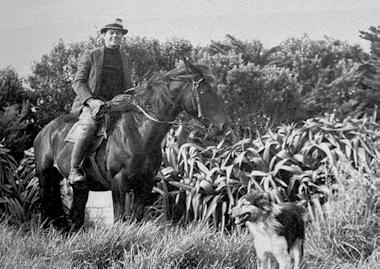

Charles Fleming at Tuku Farm, Chatham Island, 1938. Courtesy Jean Fleming

Roy Nelson

17 Autumn 2023 |

Mangere Island with Little Mangere top right in 1969. The slope centre and left is where the main tree planting was done in the 1970s. Forest & Bird Archives

In 1963, the Crown bought Mangere Island for £3,454, including a generous contribution from the Society’s supporters, and it became a protected flora and fauna reserve, although cats remained a problem.

Next, Nelson offered to help the government buy more land on neighbouring islands, but the money was not needed. The government bought a 240ha plot known as the Glory Block in the centre of Rangiauria Pitt Island that contained relatively unmodified rat-free forest.

Nelson also attempted to buy Tapuaenuku Little Mangere Island so it could become a protected bird sanctuary, but he failed and it remained in private hands.

By 1969, there were only 15–20 pairs of black robins remaining on Little Mangere. Then, in the early 1970s, it was reported that cats had killed off 12 species of birds on Mangere.

The last two populations of Chatham Island black robins on Earth were in serious trouble.

Brian Bell, a leading ornithologist and threatened species conservationist who was working for the Wildlife Service, approached Forest & Bird with a plan to save them.

In 1975, the society’s president John Jerram agreed to mount a fundraising appeal

to help save the black robin. Jerram undertook to raise enough money in donations to plant 50,000 hardy Chatham Island akeake (Olearia traversi) over five years.

Once restored, the plan was to translocate the last seven remaining birds from Little Mangere to the larger more accessible Mangere Island.

Bell even suggested a slogan for the appeal “Save the black robin –adopt a tree at 50 cents”.

The society’s branches swung into action, seeking donations from all over the country, and the appeal was a resounding success, raising more than double the target amount in 1976.

The $14,000 supported the purchase and planting of 120,000 plants on Mangere Island. In 1981, wildlife photographer Rod Morris visited and reported the plants had grown above head height, providing shelter, leaf litter, and insect habitat for the robins and other species.

But the fate of the black robin was still hanging by a thread. By 1980, there were just five birds left and only one breeding pair – Old Blue and Old Yellow.

It was up to Bell and his team, which included Don Merton, to save the species. They knew it was a race against time, having recently witnessed the loss of three unique species.

In 1964, the pair had been part of a heroic but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to save the last South Island snipe, the greater short-tailed bat, and the New Zealand bush wren from a rat invasion on Big South Cape Island, near Rakiura.

The black robin is a slow breeder, so Merton decided to try a cross-fostering programme using Chatham Island

warblers and tomtits as foster parents. This allowed the robins to produce more than one clutch per season. The success of this world-leading technique was spectacular – by the end of the 1984/85 breeding season, the number of robins had increased to 38.

Old Blue produced the entire first generation of robins born on Mangere Island, securing her a place in the annals of New Zealand conservation. Her offspring prospered. She was the mother of six chicks and grandmother to 11.

In 2010, Don Merton received an Old Blue award from Forest & Bird for his outstanding contribution to conservation. He led the black robin recovery programme for more than a decade and played a key role in saving tīeke South Island saddleback and kākāpō. Today, there are about 300 adult black robins, and the akeake forest planted with the aid of Forest & Bird donations is flourishing.

This article includes previously unpublished stories collected by Forest & Bird’s Force of Nature history project with funding from the Stout Trust.

Brian Bell in 2012.

Brian Bell in 2012.

COVER

Don Merton with a Chatham Island black robin.

A plaque on Mangere Island commemorates Old Blue's legacy. Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 18

This is how the akeake trees funded by Forest & Bird look today. Enzo Rodriguez-Reyes

LEAVING A LEGACY

Thirty-five years ago, Forest & Bird launched its Old Blue awards named after the Chatham Island black robin “mother” who saved her species from extinction. Since then, 201 men and women have been awarded an Old Blue in recognition of their huge contribution to nature protection in Aotearoa New Zealand. Here we publish a full list of the winners in tribute to all conservation volunteers – past, present, and future.

OLD BLUE AWARD RECIPIENTS 1987–2022

1987: Fraser Ross, South Canterbury |Rod Buchanan, West Coast | Nancy Payne, Central Auckland 1988: Philip Woolaston, Minister | Stan Butcher, Lower Hutt | Frank & Audrey Gamble, Southland | Jan & Peter Riddick, Central Auckland | Keith & Brenda Chapple, King Country | Lesley Shand, North Canterbury | Alan Ross, DOC 1989: David Appleton, Napier | Stan & Kath Ayling, Upper Coromandel | Bill Ballantine, Auckland | Helen Coulson, staff | Linda & Peter Daniel, DOC | Paul Every, Dunedin | Earle Norris, Waitaki 1990: Ron Freeston, Lower Hutt | Josie Driessen, South Auckland | John Findlay, Southern Hawke’s Bay | Fergus Sutherland, Southland | Cath Wallace, ECO 1991: Nina & Ken Spencer, Tauranga | Theo Simeonidis, Freshwater Anglers | Eric Geddes, North Shore | Ruth Mander, Tauranga | Ken Mason, Dunedin 1992: Christine Henderson, Southland | Ivan Green, Kapiti | Helen & Adrian Harrison, EBOP | Hugh Barr, FMC | Doug Heighway, Wairoa | John Staniland, Waitakere 1993: Ian Wilson, Far North | Debbie McLachlan, West Coast | Isabel Morgan, Napier | Alan Webster, Gisborne | Ines Stager and Peter Keller, South Canterbury 1994: Kevin Prime, Northland | Mike Kearns, Northern | Jim Howard, Rangitikei | Judy & Arn Piesse, Upper Coromandel | Dave Peebles, Lower Hutt 1995: Cathryn Ashley-Jones, Executive | John Black, South Canterbury | Kirsty Hamilton, Greenpeace | John Cuthbert, North Shore 1996: Betty Harris, South Auckland | Isobel Thompson, Central Auckland | Muriel & Ronald Ericson, Southland | Mabel Roy, Southland | Jim Holdaway, Auckland Conservation Board | Jim McMillan, Stop the Wash | Peter Maddison, Waitakere/Executive 1997: Betty Bockett, Central Auckland | Hugh Stewart, Rangitikei | Jean Luke, Kapiti | John Turnbull, Upper Clutha | Jocelyn Bieleski, Upper Coromandel | Bill Carlin, DOC 1998: Ken Catt, Waitakere | Delphine & Jack Cox, Lower Hutt | Fay Craig, Taupo | Joe Crandle, Mid North | Bett Davies, Taupo | Darrell Grace, Whanganui 1999: Don Chapple, Hauraki Islands | Michael Winch, Far North | Graham Falla, South Auckland | Christine and Brian Rance, Southland | Jenny Treloar, Te Puke | Ron Greenwood, benefactor 2000: Claire Stevens, North Shore | Valerie Campbell, North Canterbury | Roy Peacock, Hastings | Jan Butcher, Franklin | Nicky Hager, Wellington | Fensham Crew, Wairarapa 2001: Rosemary Gatland, South Auckland | Graham Petterson, Kāpiti | Dr Colin Meurk, North Canterbury | Noeline Sinclair, Ashburton | Jean Espie, Nelson-Tasman | Colin Ryder, Wellington 2002: Bill Gilbertson, Nelson-Tasman | Jo-Anne and Alan Vaughan, Golden Bay | Linda Conning, Eastern Bay

Of Plenty | Herman van Rooijen, South Waikato | Margaret Hopkins, Southland | John McLachlan, Kāpiti | Barry Wards, Upper Hutt 2003: Barry Lawrence, Upper Clutha | Philip Hart, Waikato | Gary James, Wellington | David Lawrie, Franklin | Edith Smith, Ashburton | Barry Dunnett, Kaikōura | Shaun Barnett, writer 2004: Bill Garland, outside Forest & Bird | Allan McKenzie, outside Forest & Bird | Basil Graeme, Tauranga | Raewyn Ricketts, Hastings/Havelock North (KCC) | Ruth Dalley & Lance Shaw, Southland (campaigning) 2005: Gary Bramley, Far North | Ken Lake, Central Auckland | Pete Lusk, West Coast | Betty Normington, Te Puke | Murray Hosking, outside Forest & Bird 2006: Peggy & Rob Snoep, Southland | John Talbot, South Canterbury | John Sumich, Waitakere | Jim Lewis, North Shore 2007: Karen & Maurice Colgan, North Shore | Carole Long, Bay of Plenty | Peter Howden, Ashburton | Arthur Cowan, Waikato | Bill Moore, Kāpiti | Geoff Harrow, Christchurch 2008: Liz Slooten, Executive | Ann Graeme, KCC coordinator | Geoff Park, ecologist | Bill Milne, Lower Hutt (posthumous) | Alan & Glennis Shephard, Upper Hutt| Muriel Fanselow, Dorothy Wernham & Rona Wark, North Shore KCC founders | Gillian Pollock, Nelson-Tasman | John & Pixie Marsh, Rangitikei 2009: Craig Carson, Southland | John Kendrick, bird call recordings | Dorothy Mutton, Te Puke | Queenie & Peter Balance, Nelson/Central Auckland | Tina Morgan, Upper Coromandel | 2010: Tom Hay, North Canterbury | Dave Kent, F & B magazine designer | Eddie Orsulich, Tauranga | John Topliff, Kāpiti/ Mana | Chris Bindon, Waitakere/Kaipara | Don Merton –issued by Executive under special circumstances in 2010 2011: Andy Dennis, Nelson | John Groom, Bay of Plenty| Mike Joy, Kāpiti | Alex Kettles, Lower Hutt | Jon Wenham, Waikato 2012: Eleanor Bissell, Christchurch | Anne Fenn, Central Auckland | Anne & Jack Groos, South Auckland | Maryann Ewers & Bill Rooke, Nelson-Tasman | Helen Campbell, Nelson-Tasman 2013: Hermann Frank, South Canterbury | Susan Millar, Upper Hutt | George Mason, New Plymouth | Rosalie Snoyink, Canterbury | Rod Morris, Otago Peninsula | Arthur Hinds, Waikato 2014: Nikola Hurring, Dunedin | Hugh Wilson, Banks Peninsula | Wilma & Ian McDonald, South Otago | Ian Noble, Hastings/Havelock North | Robin Chesterfield, Wellington 2015: Craig McKenzie, Dunedin | Julie McLintock, Nelson Tasman | Rod Brown, Kerikeri | Sylvia Jenkin, Wellington 2016: Roger Grace, Auckland | Neil Sutherland & Sheryl Corbett, Leigh | Laura Dawson, Taupō 2017: Glenys Mather, West Auckland | Bill Kerrison, Bay of Plenty | Margaret & Malcolm McPherson, Timaru | Wanda Tate, Porirua | Dr Jan Wright, Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment| Russell Bell, Lower Hutt 2018: Roger Williams, Warkworth | Neil Eagles, Napier | Graeme Loh, Dunedin 2019: Jenny Campbell, Southland | 2020: Liz Carter, Napier | Pat Heffey, Northland | 2021 and 2022: No Old Blues awarded.

19 Autumn 2023 |

Old Blue. Don Merton

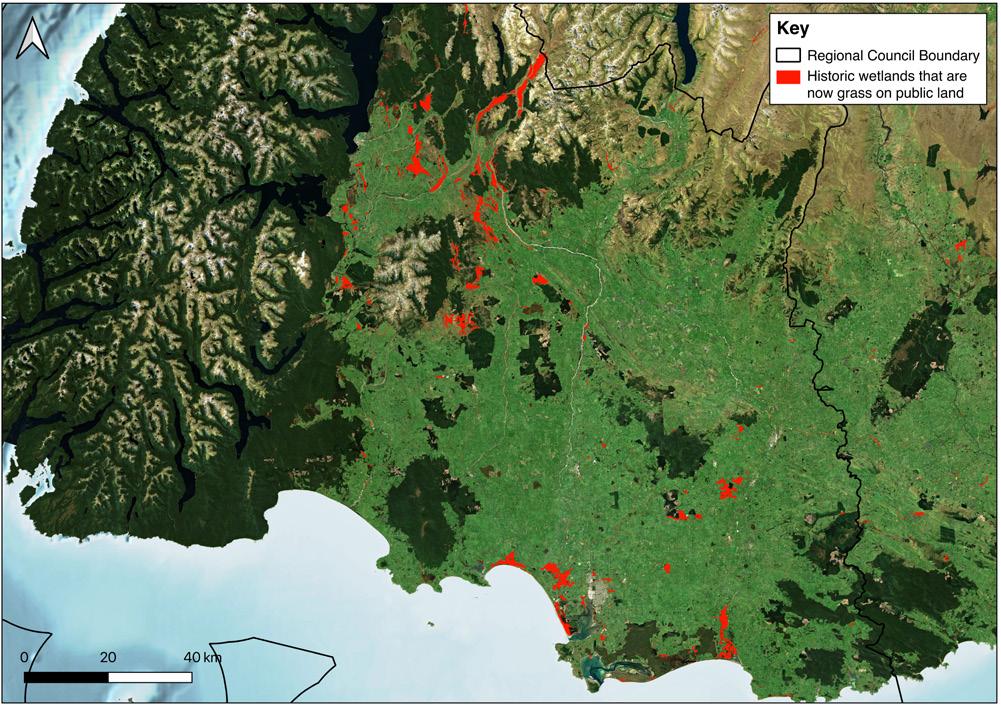

BRING BACK WETLANDS

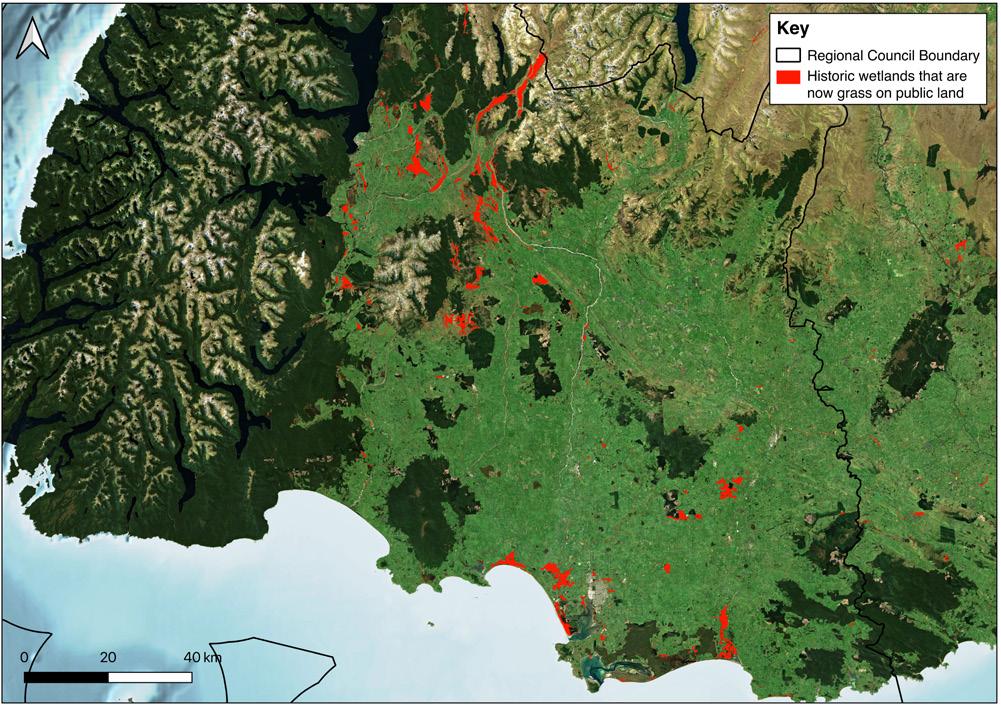

A new report commissioned by Forest & Bird has revealed thousands of drained wetlands could be brought back to life.

Sadly, 90% of Aotearoa New Zealand’s wetlands have been lost over the past 100 years after being drained and built on or turned into farm pasture, parks, mines, or quarries.

But the wonderful thing about wetlands is they have the potential to be rewetted, providing valuable new habitat for native species and helping mitigate climate change impacts.

You may have seen examples of this in this magazine recently with community-led wetland restoration projects in Coromandel and Southland.

Last year, Forest & Bird decided to find out how much former wetland was still in public ownership and therefore could be more easily restored by agencies.

We asked GIS mapping analyst Paul Hughes to identify historic wetlands across the country that could be brought back to life. We launched the findings in February on World Wetlands Day.

Forest & Bird’s freshwater advocate Tom Kay says about 125,000ha of river and stream margins, farmland, conservation land, parks, and other areas in public ownership could be considered for wetland restoration.

“These spaces have been cleared or drained and are now grassed, but there is a golden opportunity for councils and the government to restore many back to wetland ecosystems,” said Tom.

“Using Geographical Information System (GIS) software, we overlaid maps showing historic wetlands with other maps from the Central Record of State Land, the Land Cover Database, as well as maps from other sources.

“What we’ve discovered is a significant area of public land – in slivers, pockets, and larger areas – that were historically wetlands and could be again.”

The largest land holdings are managed by Pāmu Farms (29,000ha), the Department of Conservation (21,000ha), Land Information New Zealand (20,000ha),

Cate Hennessy and Caroline Wood

Southland Regional Council (3800ha), and the University of Canterbury (3400ha).

Forest & Bird hopes these organisations and local councils can build on our analysis and identify potential areas for wetland restoration. A couple have already contacted us to ask for our report and maps.

Several wetland restoration projects are already under way on public land, including:

n Kopurererua Valley wetland restoration and stream realignment (Tauranga City Council)

n Te Pourepo o Kaituna wetland creation (Bay of Plenty Regional Council, Department of Conservation, Tapuika, and Ngāti Whakaue)

n Queen Elizabeth Park wetland restoration as a permanent carbon sink (Greater Wellington Regional Council)

n Te Kuru wetland restoration and stormwater basin (Christchurch City Council)

n Fred Burn wetland protection and restoration, Southland, (Pāmu).

“The wetland restoration projects already happening around Aotearoa show what is possible,” added Tom.

FRESHWATER

Kaituna wetland restoration. Bay of Plenty Regional Council

Historic wetlands in Southland (marked in red) that may have the potential to be restored.

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 20

Forest & Bird

“More and more councils and community groups are recognising the value of wetlands for carbon storage, climate resilience, biodiversity, and recreation.

“While some of the places identified in our report might not be suited to restoration, others would be ideal.”

Restoring wetlands will help the government achieve its climate, emissions, and biodiversity targets.

Forest & Bird hopes Ministers and council officials will use the findings contained in our new report Every Wetland Counts: Mapping the restoration potential of historic wetlands in public ownership as a starting point in identifying local sites for restoration.

Southland region has the most historic wetland still in public ownership (28,000ha), followed by the West Coast (20,000ha), Canterbury (18,000ha), Northland (16,000ha), Manawatū-Whanganui (11,000ha), and Waikato (10,000ha).

“Adding local data plus insights from iwi and community groups, it should be possible to prioritise potential projects all over the country,” said Tom. “We hope these findings will help communities start having these conversations.”

For more information about wetland restoration, see www.worldwetlandsday.org.

SHOW SOME AROHA FOR WETLANDS

Watching our country’s biggest-ever climate events unfold earlier this year in Auckland, Northland, Tairāwhiti, and Hawke’s Bay was heart-breaking.

Many of us felt helpless watching water pouring into homes and businesses, and landslips and storm surges destroying homes and roads. The two cyclone-related storms of January and February brought fear into the hearts of many.

But we are not helpless. We can take action. There’s so much good we can do by working together to protect and restore New Zealand’s life-giving wetlands, including in urban areas.

They can be our shield in helping protect against further flooding and other worst-case-scenario climate events.

“Communities experience massive benefits when local wetlands are restored,” says Tom Kay, Forest & Bird’s freshwater advocate.

“There’s enormous potential for central and local government to identify and prioritise new wetland

restoration projects, and we hope our report and maps will help them do this.”

Please take a stand and show your love for our wetlands by making a donation today. Together, we can help our precious natural wetlands keep nature and communities safe.

Donate today at www.forestandbird.org.nz/saveour-wetlands.

SEVEN BENEFITS OF RESTORING WETLANDS Revive biodiversity | Filter and replenish water supply | Store carbon | Blunt the impact of floods and storms | Improve livelihoods | Boost eco-tourism | Enhance wellbeing

WHAT IS FOREST & BIRD DOING?

Forest & Bird is campaigning for stronger wetland protections in Aotearoa while also working to restore wetlands in our own reserves.

Last year, Forest & Bird launched a new campaign called Every Wetland Counts | He Puipuiaki Ia Rohe Kōreporepo.

The campaign has six asks, including doubling natural wetland extent by 2050 and developing a national wetland restoration plan.

Our freshwater team is due to give an oral submission on our wetland asks to the government’s Environment Committee later this year.

As well as national advocacy, Forest & Bird’s branch volunteers look after wetlands in a string of reserves

from Northland to Southland.

These include a rare dune lake ecosystem at Forest & Bird’s Arethusa Lodge, in Northland, the Fensham Reserve, in the Wairarapa, home to many rare plant species, and the Fleming wetland, in our Lenz Reserve, the Catlins, where spotless crake were recently discovered.

For decades, our volunteers have also helped restore wetlands on conservation and privately owned land in their communities.

This includes the Waitangi Regional Park wetland restoration (Napier Branch), the Waiū wetland restoration, Wainuiomata (Lower Hutt Branch), and Poukawa Stream (Hastings-Havelock North Branch).

21 Autumn 2023 |

Heart of Voh mangrove wetland, New Caledonia. Shutterstock

OUR REMARKABLE SOUTHERN KAURI-LANDS

The magnificent kauri of the Waikato may not be as famous as some of their northern cousins, but they are vital to the future of the species, being almost free from kauri dieback disease. In the first of a two-part series, Dr Bruce Burns, one of New Zealand’s leading kauri academics, looks at the importance of our southern kauri forests and what makes them unique. Despite the threats they face, he is hopeful that, with a little human help, they can and will thrive into the future.

SPECIAL REPORT

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 22

Giant kauri at Waiomu, Coromandel. Ian Preece

Kauri have charisma. Their imposing columnar trunks rule over the forest, and their spreading greygreen canopies are open enough to provide a light and uplifting ambience to the forest understorey. Kauri are extreme trees in many ways – extreme in potential size, life expectancy, effects on the forests they inhabit, values they provide, and cultural importance.

As a botanist, I am always excited when I venture into a kauri forest, as it creates an unusual environment providing habitat for rarely seen plants. For example, the fan fern and the kauri greenhood orchids are almost solely restricted to kauri forests, with many other species having similar strong associations with kauri, including Archey’s frog. But it’s not only about individual species, being in a kauri forest stimulates all the senses at a more fundamental level – one can feel the presence of these giant trees around, reigning over the forest and its denizens.

Although kauri encompass the northern third of the North Island, narratives of kauri forest often focus on Northland and Auckland, where their abundance and influence on landscapes are undoubted. The influence of kauri in the southern third of its range, however, has been somewhat neglected. Here, I want to delve into the story of kauri at its southern reaches – the kauri of the Waikato, Coromandel, and Kaimai Ranges. In these areas, kauri is equally special, has its own ecological signature, and provides historically and biologically fascinating stories with similarities and differences to the north.

Kauri extend from North Cape to its southernmost natural stands on or close to 38°S latitude just south of Kāwhia. That puts about one-third of its distribution south of the Bombay Hills in the Waikato region (including the Coromandel), with a few stands still occurring in the far northwestern corner of the Bay of Plenty region around Katikati. In the Waikato, kaurilands now cover about 94,000ha in a range of ecological scenarios, but, similar to other parts of their distribution, this represents a shadow of its former territory.

23 Autumn 2023 | →

Dr Bruce Burns is an Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland. Academic references for this article are available on request.

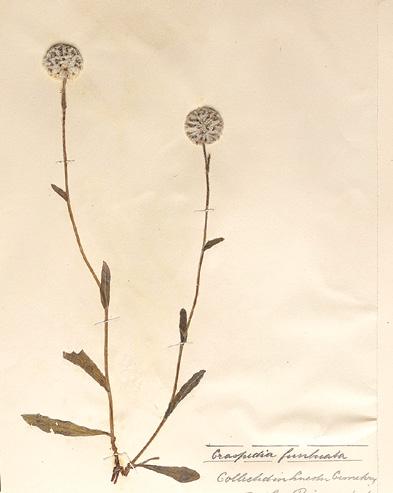

Kauri greenhood orchid. Biosense

Fan fern Schizaea dichotoma Jacqui Geux

Archey’s frog. Mahikarau Forest Estate

After the extensive exploitation for kauri timber that occurred from the mid-19th to the early 20th centuries, the area in mature kauri forest nationwide is now estimated at only a few percent of its original extent, with a greater but still relatively small area in younger regenerating kauri stands that were mostly initiated after the logging. Interestingly, much territory that originally supported kauri has not regenerated with kauri after its removal. It is not clear why this is so, but it is probably because logging was so effective that it removed any potential kauri seed sources and that logged sites were usurped by other tree species at the key time when kauri regeneration could have occurred, making them unavailable for kauri regeneration even if seed did eventually arrive.

In its southern range, notable stands of oldgrowth kauri still exist and include the high-altitude kauri on Te Moehau, giants in the Manaia Forest Sanctuary saved from logging in 1972, stands of mature kauri in the headwater valleys of the Third Branch of the Tairua River (which were inaccessible to exploitation), Whenuakite, Waiau Kauri Grove, Waiomu, Mt William, Tuahu, Pukemokemoke, Miranda Scientific Reserve, and Te Kauri Park near Kāwhia.

Many of these surviving mature stands still include some amazingly big and very old trees. The Manaia Forest Sanctuary on the Coromandel Peninsula was established to protect its superb old-growth kauri and holds many trees greater than 2m in diameter, including the sixth-largest known kauri, Tānenui. This tree was measured with a diameter of 3.5m and standing at 49.7m tall in 1976; it will be larger now. In 1987, Moinuddin Ahmed and John Ogden measured 25 old-growth kauri stands across Aotearoa, and the stand at Manaia had the largest basal area (a measure combining density and tree size) recorded anywhere. It also had the oldest trees, with one reliably estimated at 1527 years old.

Large kauri also occur in other parts of this southern domain. In 2002, former New Zealand Forest Service ranger Max Johnston provided details of 31 massive kauri that he and his colleagues had discovered and measured in the last few decades of the 20th century. These include the well-known Hamon Kauri, Square Kauri, Cookson Kauri, Tairua no 1, Waiomu no 1, and Tuahu trees. The amazing exploits of Johnston and his friends in searching out these large kauri in the Coromandel are not unique, and others continue to go into the hills in search of trees and other artifacts of the kauri logging era. Other kauri of interest are those that have paired up to form two large trunks side by side. These include the Siamese Kauri of the Waiau Grove and the Twin Kauri just north of Tairua.

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 24 →

Siamese Kauri, Waiau Forest, 309 Road, Coromandel. Ian Preece

Although large trees still exist in our kauri forests’ southern range, even larger giants that now no longer exist were recorded in the past. The 19th century botanist Thomas Kirk measured a kauri at Mill Creek, Mercury Bay, near Whitianga, at 7.3m in diameter. This giant tree was known as “Father of the kauri”, “Father of the forests”, and “King of the kauris” by local iwi in the area. An enormous tree was also reported in the upper reaches of the Tararu Stream, near Thames, in the late 1800s, with a diameter of approximately 4.5m, while local lore reports that kauri loggers and gum diggers used to have dances on a kauri stump 4.2m in diameter near Dancing Creek in the Kauaeranga Valley. By comparison, the largest surviving kauri tree in Aotearoa, Tāne Mahuta, is approximately 4.9m in diameter, according to a 2009 measurement in the New Zealand Tree Register.

As a species, kauri (Agathis australis) is ancient. It has been in New Zealand for most, if not all, of the time Aotearoa has been a separate fragment of the former Gondwana supercontinent. Kauri were once distributed more widely in New Zealand than now, with kauri fossils found throughout New Zealand, including in Southland. More recently (geologically speaking) during the last ice age, kauri were probably limited to small refuge areas in the Far North before spreading south to their current distribution, starting around 7000 years ago.

About 3000 years ago, Kauri reached their current boundary, a line around 38°S latitude joining Kāwhia Harbour on the west coast with Tauranga on the east coast, with no evidence of further southward movement since then. This line is referred to as the Kauri Line and has been identified as a major zone of discontinuity in the distributions of many other native plant and animal species.

The question of why kauri only grow naturally north of this line in modern times has been the subject of conjecture among scientists for many years. A key early hypothesis was that seedling kauri are killed by frosts and this line marks the point moving southwards where frosts are too common for kauri seedlings to survive. Nevertheless, kauri planted in more southern areas seem to survive and grow well, albeit in sheltered sites, with individual kauri planted as far south as Rakiura Stewart Island. As well, stands planted around Wellington and New Plymouth are known to produce persistent seedlings, bringing the frost hypothesis into question.

Alternative hypotheses for the location of the Kauri Line focus on historical or environmental explanations. One historical rationale is that the Kauri Line coincides with the furthest probable extent of continuous forest during the height of the last glaciation. A hypothesis based on this coincidence suggests this landscape pattern has persisted into modern times, with kauri present in this continuous forest zone during glacials but outcompeted when the opportunity arose to colonise more southern sites that became available to

forest species when the current interglacial began. In terms of an environmental explanation, a 2020 analysis by PhD student Toby Elliott pointed out the height of the land above sea level generally increases abruptly as one moves north to south across the Kauri Line, and this sudden elevation increase may make kauri colonisation to the south difficult.

Kauri have always been important to the human inhabitants of its southern range. To iwi, kauri was and is a taonga species and the king of the forest. Many large war canoes were made from specially selected kauri logs, and kāpia (kauri resin) was used to provide a tattoo pigment, used as a fire-starter, and chewed as a treatment for stomach upsets. The earliest encounter by Europeans of kauri was undoubtedly when Captain Cook and his crew

25 Autumn 2023 | →

n Southern kauri forests are found in the Waikato region.

landed at Mercury Bay, in the north-eastern Coromandel, in November 1769. These and other early European explorers were impressed with the kauri as potential ship masts and spars, and kauri were first cut and exported in numbers for this purpose, many from the harbour at Whitianga.

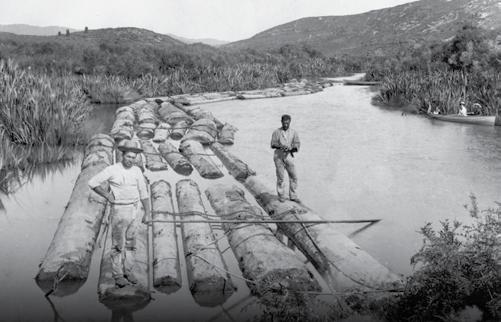

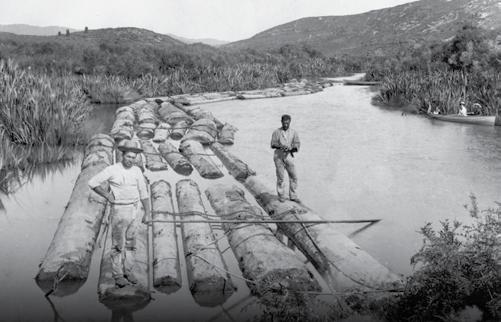

By the middle of the 19th century, the high quality and quantity of timber that could be gained from logging kauri led to the establishment of a substantial industry, a key factor in kickstarting the New Zealand economy. Bushmen were employed to extract the often giant logs from forests wherever kauri occurred, and their efforts live on as part of the pioneering lore of New Zealand.

Nowhere were the ingenuity and engineering skills of the kauri bushmen used with more ruthless efficiency than in the steep terrain of the Coromandel Range, including the Kauaeranga Valley. The valley was logged for kauri from the 1870s to the 1930s, and during this time approximately 450,000m3 of kauri timber were removed, enough to construct 20,000 three-bedroom houses. The result of this extreme activity has left scars on the landscape that are still observable, and the forest is still recovering.

The last areas in Aotearoa to be logged extensively for kauri were generally in the south. The last kauri “dams” built to move logs downriver were those in the Kaimai Range near Katikati in the early days of World War II.

As well as timber, kauri also produces kāpia or kauri gum. In some ways, “gum” is a misnomer, as the exudate produced from kauri is not actually a gum in a strict sense but a plant resin, and fossilised kauri resin can be considered amber. Kauri resin accumulates in soil currently or formerly occupied by kauri forests, and the mining of such deposits fuelled an extractive industry almost as important as the kauri timber industry in 19th century New Zealand.

Although most kauri resin was extracted in Northland, gum digging also occurred on the Coromandel and a few other sites in kauri’s southern range.

Once it became difficult to find gum in soil, it was discovered that it could be obtained by “bleeding” trees, by purposefully cutting notches in trunks. The practice of bleeding kauri was employed on the Coromandel Peninsula, and many of today’s large trees exhibit scars resulting from such actions.

This may make them more susceptible to disease in the future, although the gum sought by the bleeders but still on the trees could now be protecting these giants from further decline by acting as a natural Band-aid.

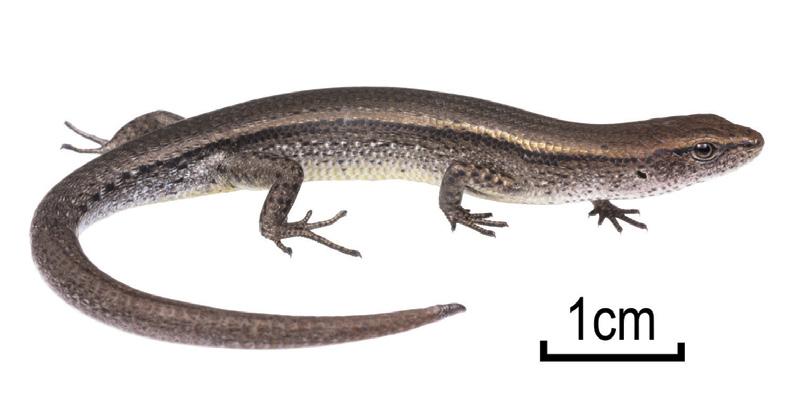

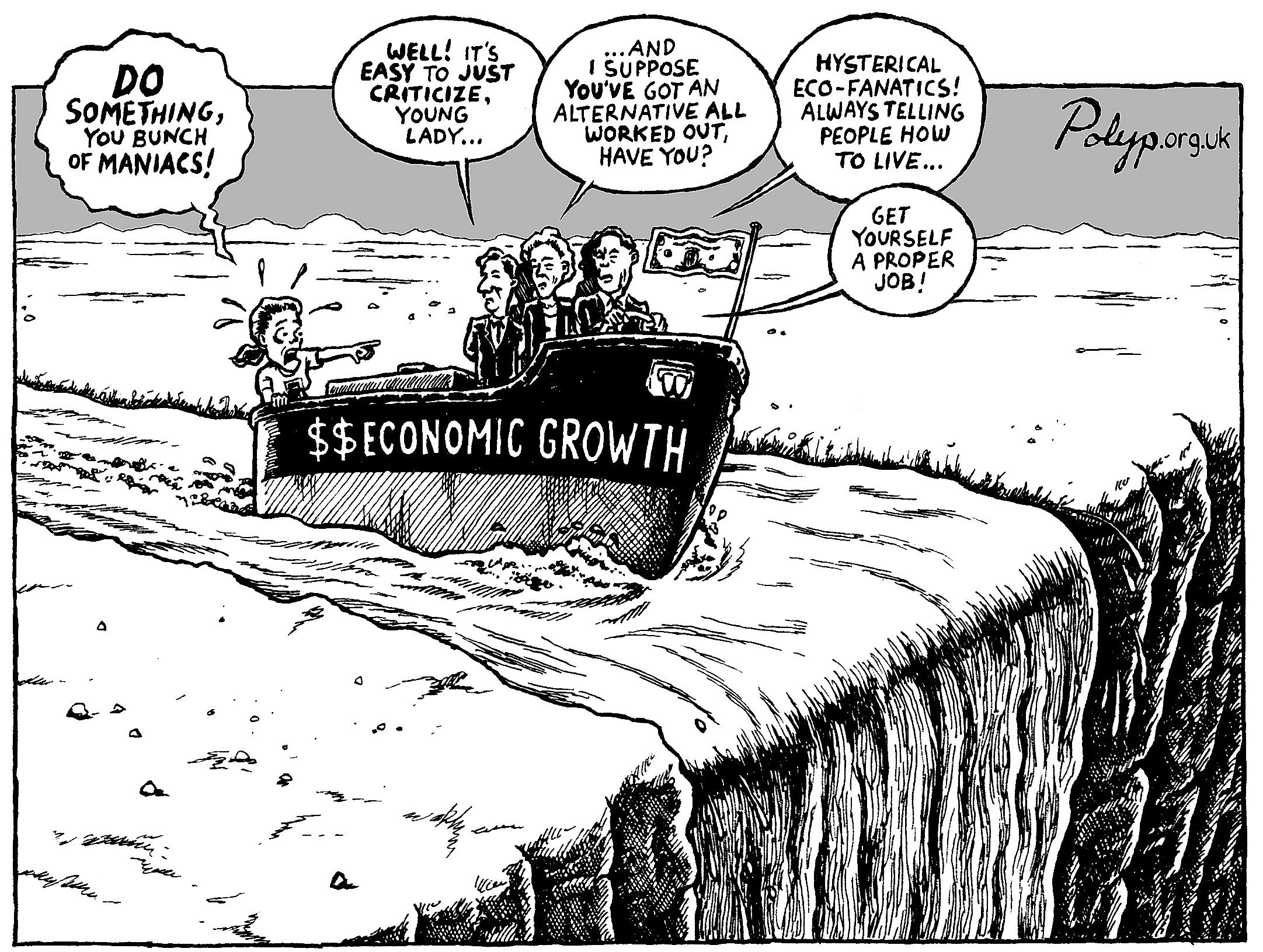

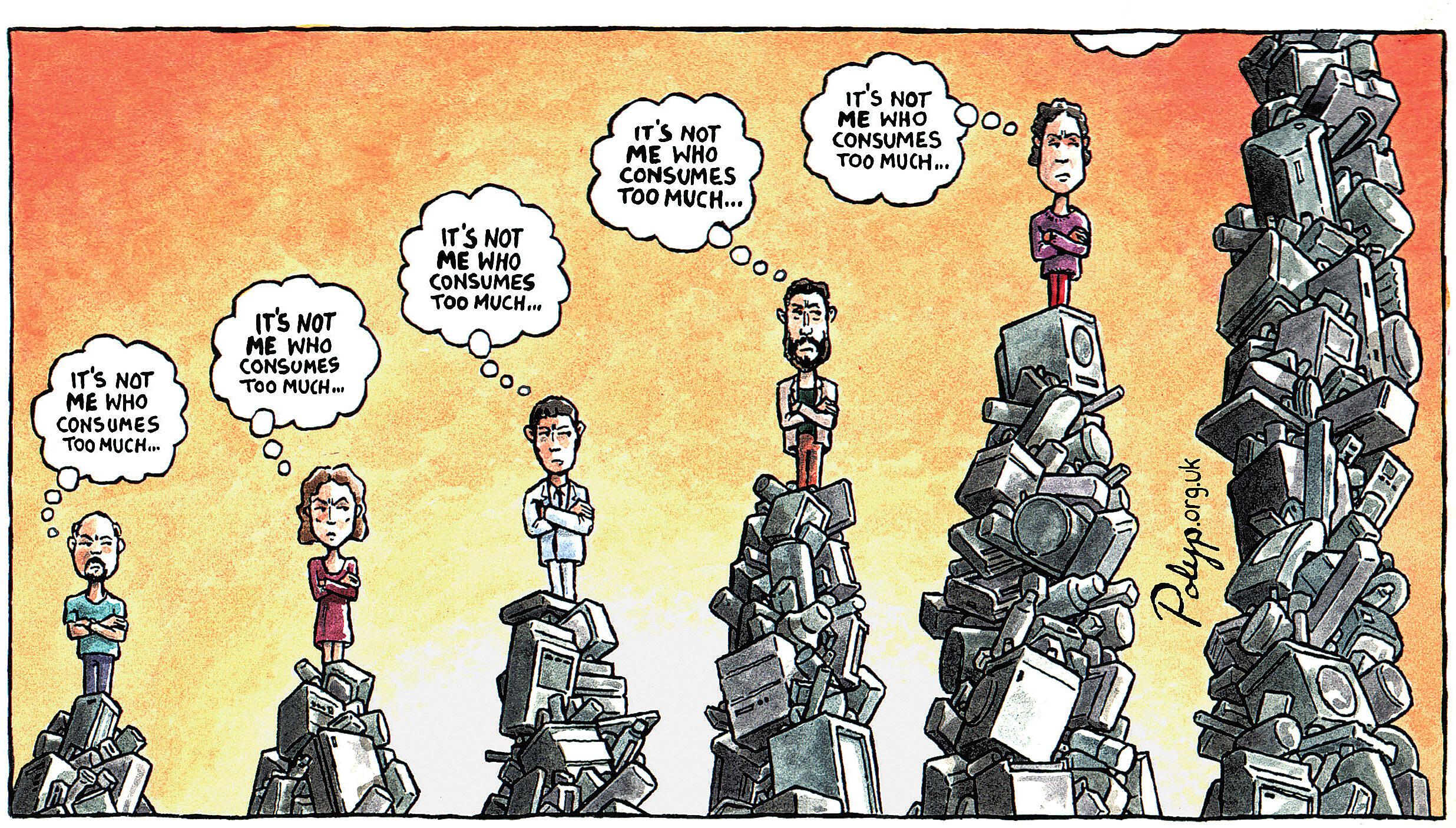

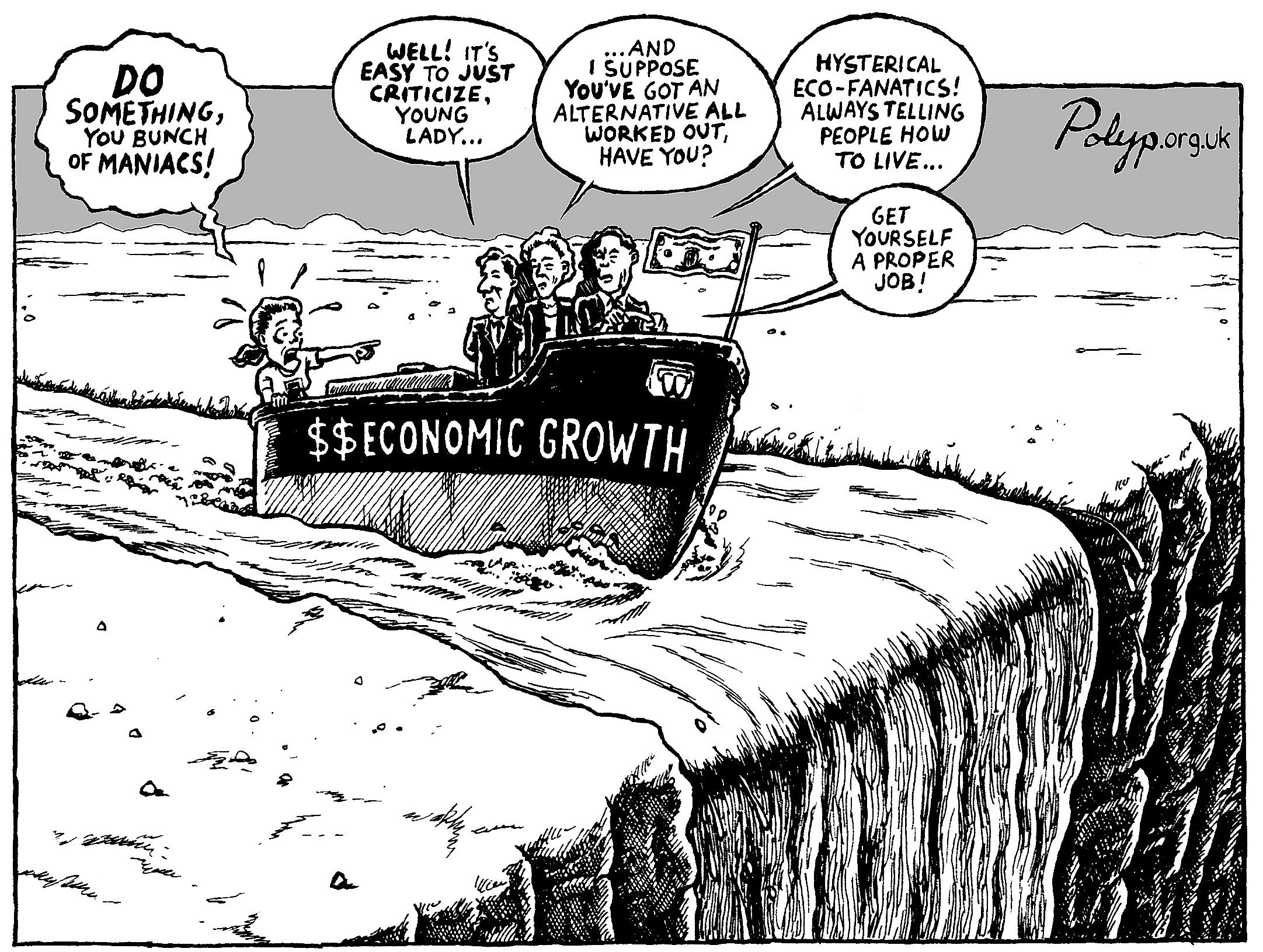

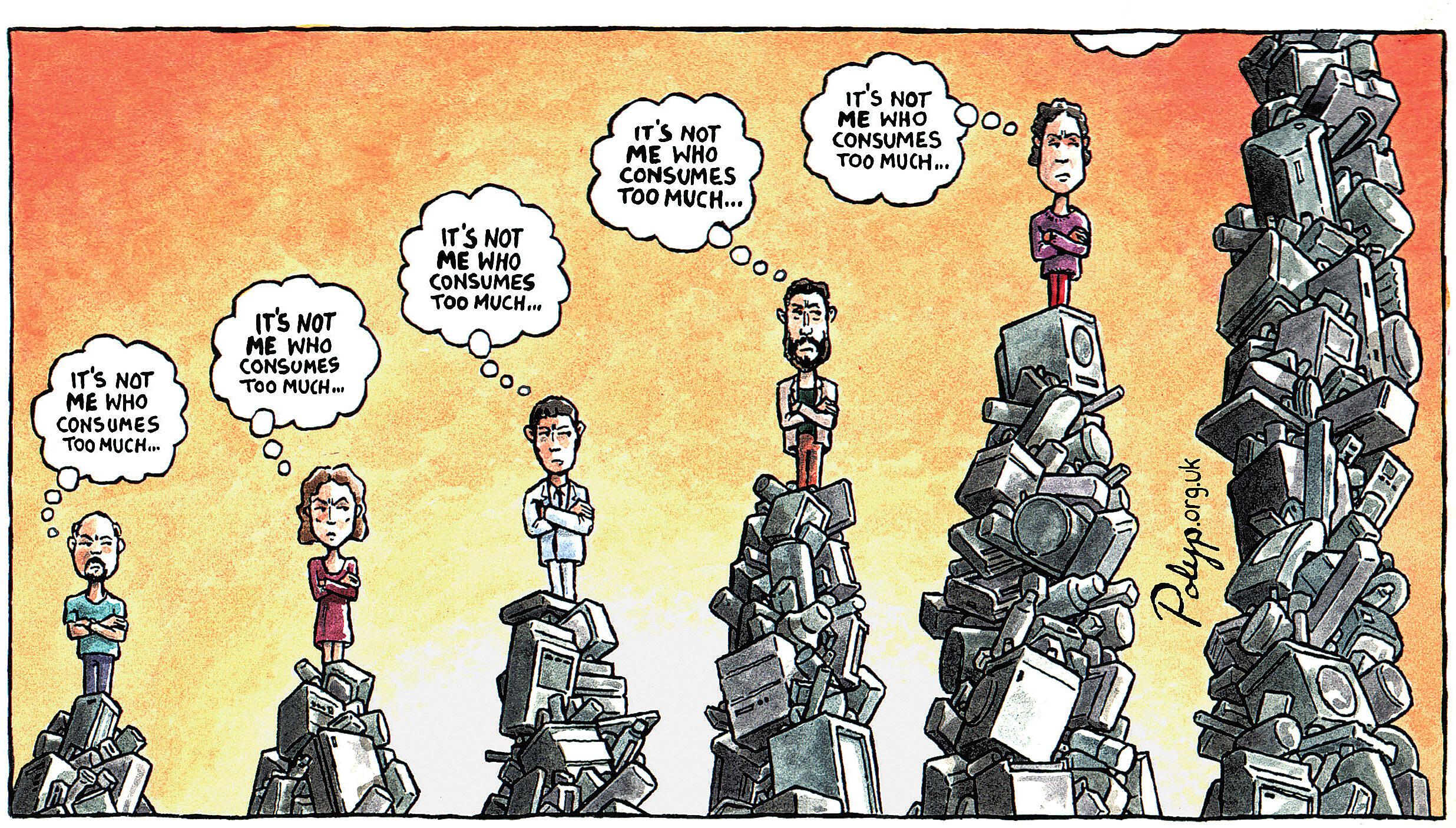

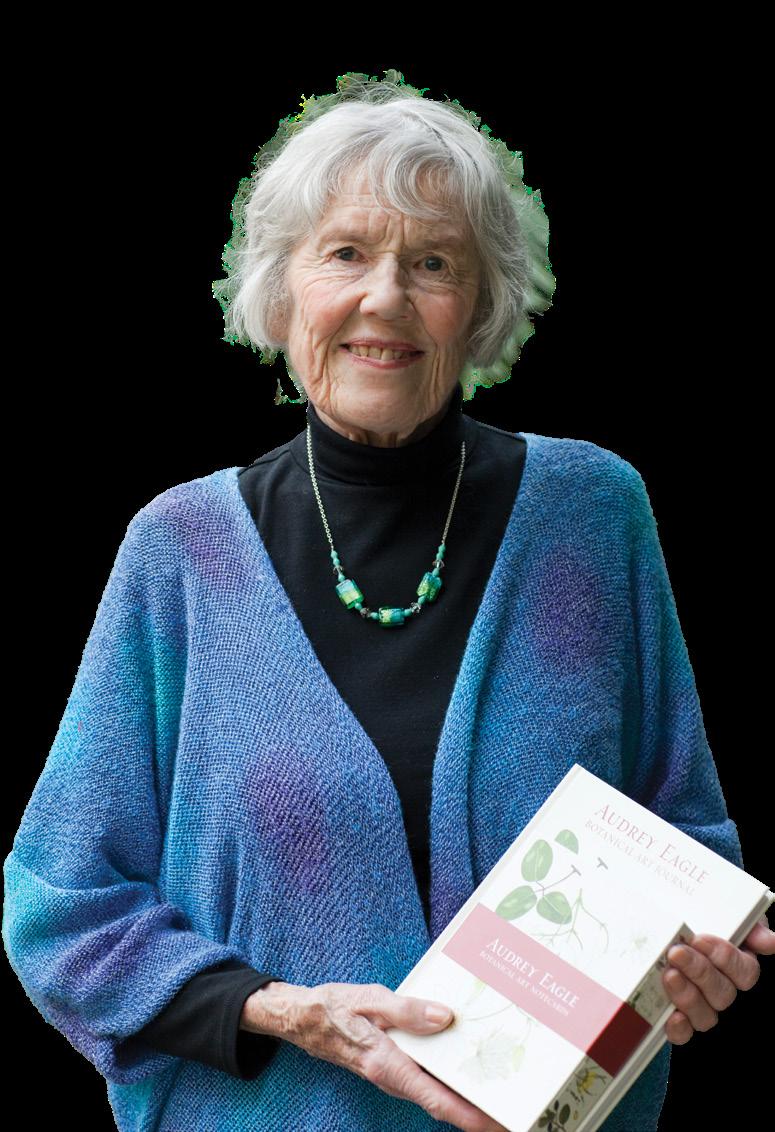

This article was commissioned by Waikato Regional Council with the support of Tiakina Kauri, the Kauri Protection Agency. In the next issue: Bruce Burns looks at the unique ecology of Waikato’s kauri forests and the threats they face from kauri dieback disease and climate change.