No Significant Host-Plant Oviposition Preference

Observed in a Comparison Between Pieris rapae Oviposition and Larval Growth Rates Based on Optimal Oviposition Theory

Joseph, Glaxton; Ledford-White, Finn; Nabizai, Sahar; Pel, Kiana; Perkins, Theron

Abstract

Pieris rapae, known by their common name, the Cabbage White Butterfly, is an invasive pest species prevalent in the Americas, inhabiting 32 countries across the world. Their pestilent eating habits result in significant crop loss among many Brassica species (Ryan et al., 2018). Understanding the relationship between P. rapae host plant oviposition preference and the success of their offspring plays a crucial role in informing existing pest management research, allowing for more effective mitigation of their detrimental effect on Brassica crop yield. During reproduction, many insects display a phenomenon referred to as optimal oviposition theory or the “mother knows best” principle, which postulates that female insects oviposit preferentially, laying their eggs on plant species that will maximize the success of their offspring (Jaenike, 1978). This experiment aimed to determine if host plant preference for P. rapae supports optimal oviposition theory. To test this, butterflies were collected, set up in a cage with three different species of plants, Champion Collards (Brassica oleracea var. Champion), Dinosaur Kale (Brassica oleracea var. palmifolia), and Giant Red Mustard (Brassica juncea), left to lay eggs for 24 hours, and proportion of eggs laid on each variety of host plant was observed. Larval growth rates and pupal masses for individuals reared on each variety of plant were recorded in order to observe the relationship between oviposition preference and larval success based on offspring mass. Based on prior

studies, it was hypothesized that P. rapae would show a significant ovipositional preference for Champion Collards and larvae reared on this host plant would have accelerated growth rates. Though the data indicate that adult P. rapae show a trend toward ovipositing on Champion Collards, a chi-squared test did not support a statistically significant oviposition preference based on the data. P. rapae reared on Champion Collards did not display an accelerated growth rate, but P. rapae did show higher final larval mass than larvae reared on other varieties of hostplant. These findings are important because the observed trend toward ovipositing on Champion Collards in conjunction with the higher final larval mass observed on larvae reared on Champion Collards suggests a likelihood that if further trials of this experiment were conducted, a significant ovipositional preference could be observed and effectively related to optimal oviposition theory.

Introduction

P. rapae are an invasive species of butterfly that destroy the host plants they lay their eggs on (Ryan et al., 2018) Brassica varieties including plants such as collards, kale, mustard greens, and many other varieties of leafy greens are the most common host plants they lay their eggs on, also known as oviposition. Oviposition is a foundational aspect of optimal oviposition theory, the theory on which our research was centered. This theory is also frequently referred to as the “mother knows best” theory of oviposition and it suggests that female insects oviposit based on which hostplant will bring up the most successful offspring (Jaenike, 1978). We chose to focus on P. rapae specifically because they are phytophagous, meaning their offspring eat plants,

specifically the plants on which they were oviposited. This is relevant because optimal oviposition behavior is especially prevalent in phytophagous insects (Jaenike, 1978). Another factor that makes P. rapae a favorable species to use in this experiment is that extensive prior research has been done on P. rapae oviposition, making it easy to compare our findings with existing studies examining ovipositional choice and its relation to optimal oviposition theory. For example, one study examining optimal oviposition in P. rapae found that females of this species choose which host plant to oviposit on based on innate preference hierarchies like P. rapae’s inherent preference for plants with higher nitrogen content. This study found that oviposition preference is additionally impacted by adult butterfly learned experience. For example, female butterflies often sample their environment and focus their oviposition on the host plant that is most locally abundant (Petrén et al., 2021). A different study found that while Pieris rapae do not show an ovipositional preference for Brassica varieties that result in the highest survival-rate outcome, they do show a significant laying preference for host plants such as B. nigra that yielded caterpillars with statistically higher larval-weights compared to the other host plants in the study (B. montana, B. rapa, H. incana, S. arvensis, R. sativus, B. olercea, and A. thaliana), therefore supporting the “mother knows best” principle of oviposition preference (Griese et al. 2020). Based on this information, it was hypothesized that in this experiment, Pieris rapae larvae would have an accelerated growth rate and increased chrysalis mass when reared on host plant varieties that the adult Pieris rapae oviposited a higher proportion of eggs on.

Methods

Ovipositional Choice Methodology

P. rapae butterflies were collected from a variety of farms and gardens including Edmonds College campus farm, personal gardens, and Picardo Farm P-Patch Community Garden. They were collected with a net and transferred to a wax paper envelope using metal butterfly forceps. P. rapae were then stored in a cooler with an ice pack at approximately 7°C. In order to minimize damage to the organisms, butterflies were not placed directly on the ice pack or stored for longer than 5 days as this may have negatively affected their ovipository output or killed them. After butterflies were collected, a 24x15.7x15.7 inch butterfly cage was set up for each butterfly. Each cage contained one Champion collard (Brassica oleracea var. Champion) plant, one Dinosaur kale (Brassica oleracea var. palmifolia) plant, and one Giant red mustard (Brassica juncea) plant along with a 1-inch piece of sponge soaked in sugar water (1 part sugar, 4 parts water, boiled until sugar is dissolved). All plants were bought from Sky Nursery and repotted into 2.5-inch pots on the campus farm. Plants were arranged in a randomized order within the cage in order to limit the effects of P. rapae’s preference to oviposit on leaves exposed to more sunlight (Kingsolver, J. G., 2000). After a cage was set up in the campus greenhouse, a single female butterfly was released into the cage.

P. rapae, butterflies were then left to lay eggs for 24 hours (Watanabe, T., Nakamura, K., & Tagawa, J., 2018). After 24 hours, the butterflies were removed from the cage and the number of eggs laid on each plant was counted and recorded. If the butterfly was dead after the allotted 24-hour oviposition period, the data was not used. If no eggs were laid after the allotted 24-hour oviposition period, the data was not used. This process was repeated with 10 butterflies over the course of about 20 days. After all

oviposition count data was collected and recorded, the percentage of eggs laid on each plant was recorded on a per-cage basis (Nylin, Sören, & Janz, Niklas, 1993). This data was subsequently used to calculate the average percentage of eggs laid on Champion Collards, Dinosaur Kale, and Red Giant Mustard plants throughout all trials of the experiment in order to determine the host-plant oviposition preference of P. rapae butterflies. The average percentage of eggs laid was used as opposed to total eggs laid on each plant to account for the variation in the total number of eggs laid by each female (ex. One female may lay 150 eggs across 3 plants while another may only lay 30). Finally, data was used to perform a chi-squared test in order to analyze if there is a significant P. rapae oviposition.

Caterpillar Methodology

As a secondary experiment to our research on ovipositional choice we looked at caterpillar growth rate of the Pieris rapae butterfly based upon which plant variety it was laid on. Our plant varieties are Champion collards (Brassica oleracea var. Champion), Dinosaur kale (Brassica oleracea var. palmifolia), and Giant red mustard (Brassica juncea). We obtained our caterpillars from the oviposition trials we ran as described in the oviposition methodology. In order to allow us to more effectively associate ovipositional choice with growth rate, we reared the caterpillars on leaves from the same species of plant on which they were originally laid (Nylin, Sören, & Janz, Niklas, 1993). We randomly selected three caterpillars per plant from the ovipositional trial to perform our research. A total of 9 offspring per mother were used from which to collect data. The three selected caterpillars from each plant per mother were moved to a 6”

diameter petri dish where they were fed their respective plant variety until their 12th day of being in the lab. At that point, they were large enough to begin weighing and we separated the three caterpillars into three separate Petri dishes, feeding them their respective plant variety daily (D. Coley, P., L. Bateman, M., & A. Kursar, T., 2006). Within each petri dish, we used pieces of paper towels soaked with water to keep the leaves from dying prematurely. On the caterpillar’s 12th day of being in the lab, we recorded the mass of each caterpillar before putting them in their respective petri dish. From 12 days until pupation we recorded the mass of the caterpillars every other day, excluding weekends (no lab access). If a caterpillar was preparing to molt on a weigh-in day, we pushed back the weigh-in of that caterpillar to the next day to avoid the effect of molting on the caterpillar's overall growth. After each weigh-in, the caterpillar was replaced into its petri dish to continue the experiment (Griese et al. 2020). We stopped recording the mass of the caterpillars after their fifth instar. We ran 5 trials with each mother’s offspring counting as one trial. We have recorded the caterpillars' weight and averaged the weight of the caterpillars from each plant variety and then calculated the average difference in weight between the caterpillars of each variety at each weigh-in. We also determined the growth rates of the caterpillars based upon what plant variety they were raised on. As a final addition to our data of data, we also recorded the caterpillars’ pupal weight to see if there appeared to be any correlation between host plant variety and final pupal weight.

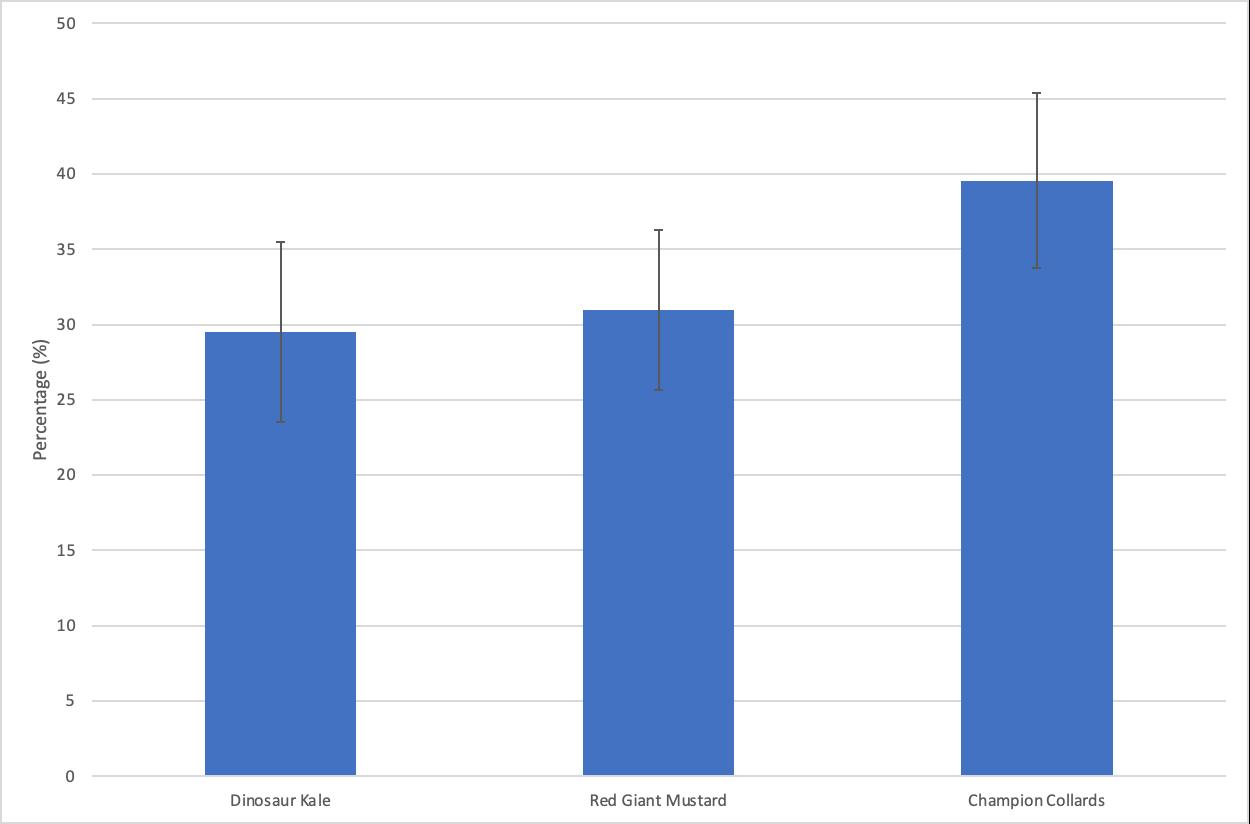

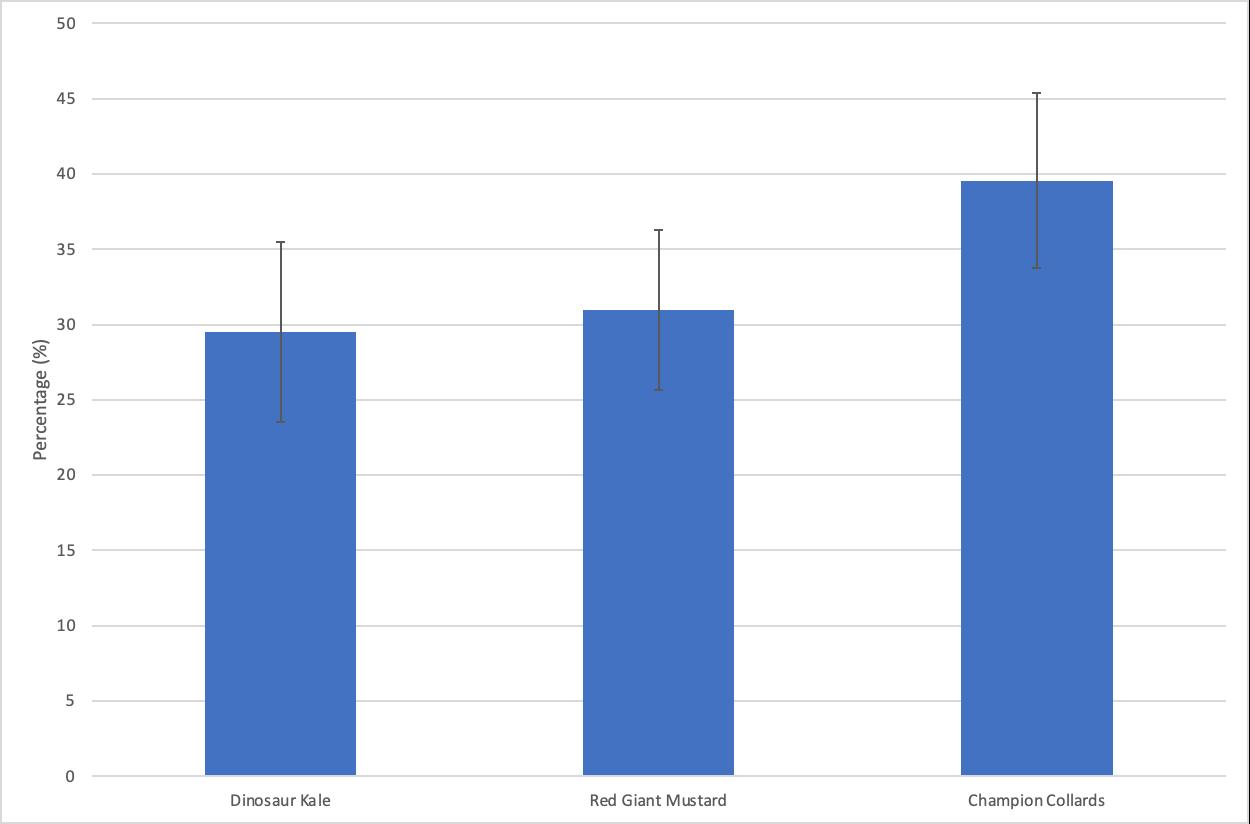

After collecting data from 10 cages, the data suggest an oviposition preference for Champion Collards as a host plant. Dinosaur Kale had the highest standard deviation. In contrast, Giant Red Mustard had the lowest standard deviation.

Results

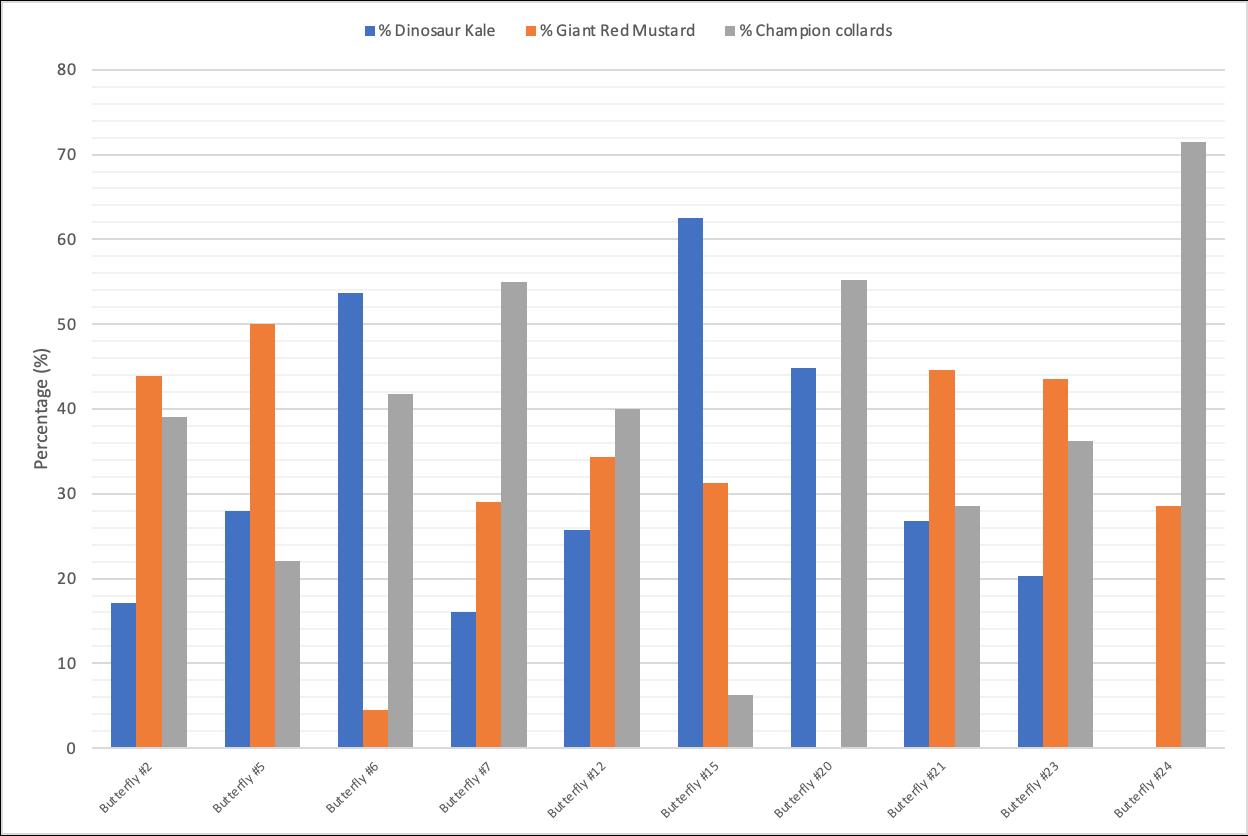

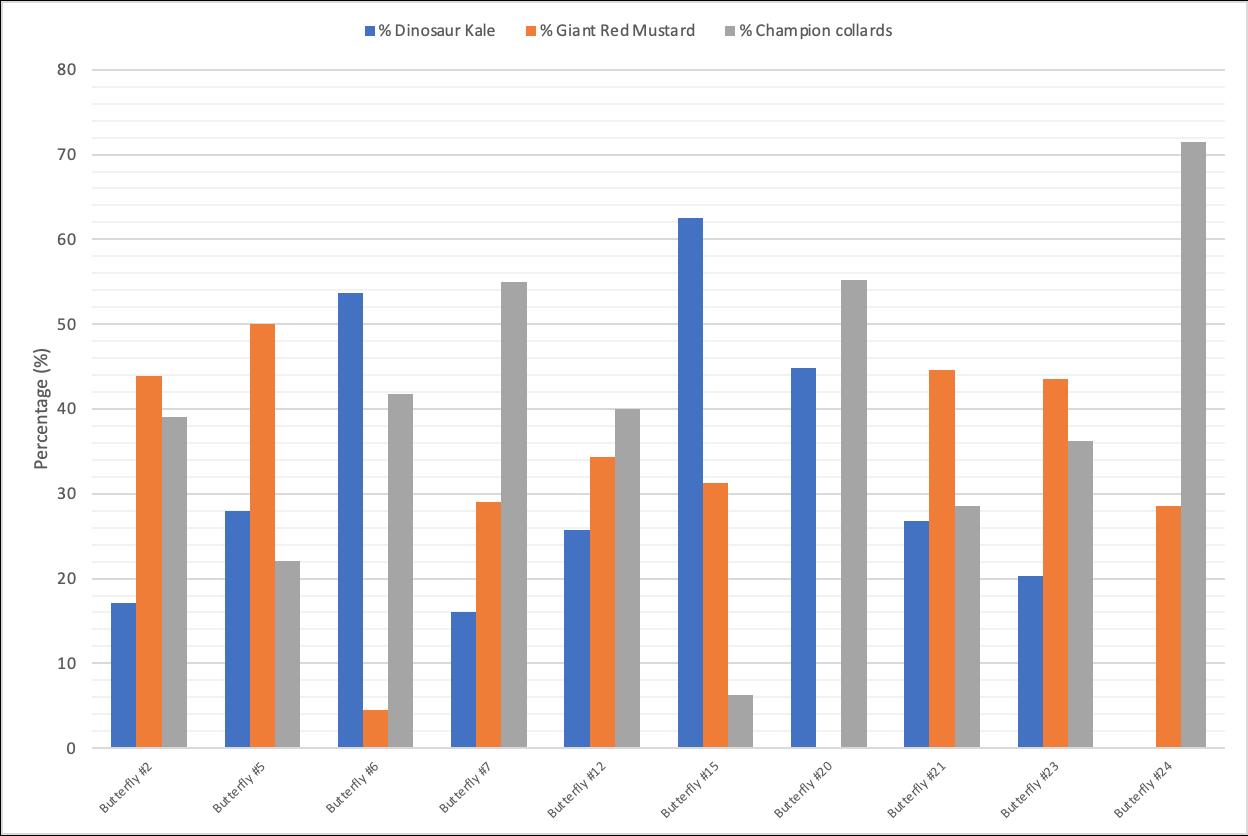

Figure 1: Host-plant ovipositional preference proportion by female P. rapae on Dinosaur Kale after 24 hours

Our data show that female butterflies oviposited 29.49% of their eggs on Dinosaur Kale as the host plant on average. On average, 30.96% of females oviposited on Red Giant Mustard. Female butterflies preferred to oviposit on Champion Collards, on average laying 39.55% of their eggs on this host plant.

Figure 3: Average host-plant oviposition proportion of P. rapae females on Dinosaur Kale, Giant Red Mustard, and Champion Collards after 24 hours

Figure 3: Average host-plant oviposition proportion of P. rapae females on Dinosaur Kale, Giant Red Mustard, and Champion Collards after 24 hours

Larvae reared on Dinosaur Kale and Red Giant Mustard Greens show a similar growth rate as the graph shows linear growth for these plant varieties between 12-14 days since hatching. Afterward, from 14-16 days since hatching, the change in mass begins to level out, with Dinosaur Kale having a higher final larval mass at 200.3mg compared

Time After Hatching Champion Collard Dinosaur Kale Red Giant Mustard 12 days 16.123 20.30 10.74 14 days 32.35 44.28 47.49 16 days 33.71 26.03 18.90

Figure 4a: Average larval masses of 45 (three per plant) P. rapae caterpillars laid by five different mothers in individual cage set-ups and reared on Champion Collards, Dinosaur Kale, and Red Giant Mustard over 12-16 days after hatching

Figure 4b: Standard deviations of points in Figure 4a in milligrams (mg)

to Giant Red Mustard’s final larval mass of 170.7mg. Larvae reared on Champion Collards, however, exhibit a slow exponential growth throughout, but at 16 days after hatching, the larval mass of individuals reared on Collards surpassed both the other plant’s with a final larval mass of 217.7mg.

Individuals reared on Red Giant Mustard plants displayed the largest average pupal weight, however, Red Giant Mustard and Dinosaur Kale displayed a similar standard deviation in pupal weight.

Discussion

We hypothesized that P.rapae larvae would have an accelerated growth rate on plants that the adult Pieris rapae preferentially lay on, based on the optimal oviposition theory. Our results showed a trend that P. rapae oviposited a higher proportion of eggs on Champion Collards than they did on Dinosaur Kale or Red Giant Mustard plants. We also found that the larvae reared on Champion Collard plants started with an initial growth rate that was insignificant but slower than the larvae on both the Red Mustard and Dinosaur Kale plants. However, on days 15-16, the mass of larvae reared on collards went up exponentially and surpassed the mass of larvae on the other two plant varieties, giving them the largest overall mass which was significantly larger than caterpillars reared on red giant mustard but not significantly larger than caterpillars

Red Giant Mustard Champion Collard Dinosaur Kale Average 175.2 157.8 155.4 Standard Deviation 29.69 11.03 31.33

Figure 7: P. rapae chrysalis mass 18 days after hatching in milligrams (mg)

raised on dino kale. While there was no significant difference in final larval mass between dino kale and collards, the final larval mass of dino kale caterpillars was significantly larger than the final larval mass of Mustard caterpillars. After performing a chi-square test, we determined that our data for oviposition preference for P. rapae was not statistically significant. Due to this analysis, we cannot accept our hypothesis. However, the trend towards laying eggs on Champion Collards may suggest that if we performed this experiment with a larger sample size of females, a significant preference for Collards could be observed. Our findings that suggest there could be a preference for Champion collards is somewhat out of line with what could be expected based upon other experiments. Research has shown that P. rapae use the presence of glucosinolates as a signal for oviposition and larval feeding (Martin de Vos et al. 2008). Based on this information, it would be more likely that P. rapae would show a preference for the Mustard plants rather than the Collards, since they have the highest glucosinolate content. In the future, we would perform more trials of this experiment which would allow us to test our hypothesis more accurately. An error that was made in this experiment was when we allowed the P. rapae in the first two trials to have 48 hours to lay eggs. These butterflies ended up dying before we came back to count the eggs, so we had to eliminate these trials from our data. We kept all future trials to 24 hours. Although it did not change the accuracy of our experiment, it left us with less data which may have led to our inability to obtain the significant results required to accept our hypothesis. Researching the correlation between P.rapae host plant choice and the growth rate of their larvae allows for better pest control in agricultural work. By

understanding what the invasive species prefers and avoids, gardeners and agricultural workers can lure them away from their crops, preventing destruction.

References

Watanabe, T., Nakamura, K., & Tagawa, J. (2018). Host-plant leaf-surface preferences of young caterpillars of three species of Pieris (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) and its effect on parasitism by the gregarious parasitoid Cotesia glomerata (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Eur. J. Entomol., 115, Article 25-29.

https://doi.org/10.14411/eje.2018.004

D. Coley, P., L. Bateman, M., & A. Kursar, T. (2006). The effects of plant quality on caterpillar growth and defense against natural enemies. Oikos, 115(2), 219–228.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.14928.x

Ryan SF. Global invasion history of the world. Global invasion history of the world’s most abundant pest butterfly: a citizen science population genomics study. 2018 December 26 [accessed 2021 June 12].

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/506162v1

Lund M. (2020) Predation threat modifies Pieris rapae performance and response to host plant quality. June 16 [accessed 2021 June 12].

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00442-020-04686-w

Griese, E., Pineda, A., Pashalidou, F. G., Iradi, E. P., Hilker, M., Dicke, M., & Fatouros, N. E. (2020). Plant responses to butterfly oviposition partly explain preference–performance relationships on different brassicaceous species. Oecologia, 192(2), 463-475. doi:10.1007/s00442-019-04590-y

Lytan, D. (2012). Effects of different host plants and rearing atmosphere on life cycle of large white cabbage butterfly, Pieris brassicae (Linnaeus). Taylor & Francis.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03235408.2012.711682

García-Robledo, C., & Horvitz, C. C. (2012). Parent-offspring conflicts, "optimal bad motherhood" and the "mother knows best" principles in insect herbivores colonizing novel host plants. Ecology and evolution.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3434947/.

Petrén, H., Gloder, G., Posledovich, D., Wiklund, C., & Friberg, M. (2020). Innate preference HIERARCHIES coupled with Adult experience, rather Than Larval imprinting Or transgenerational Acclimation, determine host plant use in Pieris rapae. Ecology and Evolution, 11(1), 242-251. doi:10.1002/ece3.7018

John Jaenike (1978) On optimal oviposition behavior in phytophagous insects, Theoretical Population Biology, Volume 14, Issue 3, Pages 350-356, ISSN 00405809, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(78)90012-6

Kingsolver, J. G. (2000). Feeding, Growth, and the Thermal Environment of Cabbage White Caterpillars, Pieris rapae L. Physiological & Biochemical Zoology, 73(5), 621. https://doi-org.edmonds.idm.oclc.org/10.1086/317758

Nylin, Sören, & Janz, Niklas (1993). Oviposition preference and larval performance in Polygonia c-album (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae): the choice between bad and worse. Ecological Entomology, 18(4), 394–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.13652311.1993.tb01116.x

Indole-3-Acetonitrile Production from Indole Glucosinolates Deters . Indole-3-Acetonitrile Production from Indole Glucosinolates Deters Oviposition by Pieris rapae. [accessed 2021 June 17].

https://academic.oup.com/plphys/article/146/3/916/6107338

Author Contributions

G.J, K.P, T.P, F.L.W, S.N all conducted the idea of this experiment, planned it all out together as a group. F.L.W did a lot of the organization when it came to the poster, collecting butterflies, meeting up, etc. T.P, F.L.W volunteered to do all of the weighings of the caterpillars and came in on time every day we had planned. G.J, K.P, T.P, F.L.W, S.N participated in catching butterflies and bringing them into campus. All of the members set up cages for the butterflies. G.J, K.P, S.N all aided in the cleaning of the lab tables as well as the cleaning of the Petri dishes after caterpillar weighing. Overall, all members contributed equally and thoughtfully to all aspects of the research.

Figure 3: Average host-plant oviposition proportion of P. rapae females on Dinosaur Kale, Giant Red Mustard, and Champion Collards after 24 hours

Figure 3: Average host-plant oviposition proportion of P. rapae females on Dinosaur Kale, Giant Red Mustard, and Champion Collards after 24 hours