Celebrated Film CODA Highlights the Need for Deaf Cinema: Breaking Free from the “Hearing Gaze”

5/23/2023 by FINN LEDFORD-WHITEDeafness isn’t a burden. Inaccurate representation is.

According to the National Research Group, “68% of Deaf viewers say that it’s generally obvious to them when a Deaf character has been written by a hearing person.” This holds true for the celebrated 2022 Academy Awardwinning film CODA.

CODA’s story follows Ruby, a 17-year-old girl with a passion for singing. As the only hearing member in her Deaf family, Ruby takes on the responsibility of interpreting for her family—navigating the balance between her dreams and familial responsibilities.

In many ways, CODA doesn’t conform to typical mainstream representations of deafness. The film discusses deaf culture and Deaf actors play the Deaf characters. Deaf folks and CODAs (children of deaf adults) have praised the

film for these reasons, hoping it is a step toward improved recognition and more deaf representation in Hollywood.

This choice to cast deaf actors cannot be attributed to the casting director, however. Marlee Matlin, the phenomenal Deaf actress who plays Ruby’s mother, threatened to quit if the dad and brother characters weren’t also played by Deaf actors.

“I

Though CODA shows some improvement in deaf representation, there are still ways that this film feeds into harmful mainstream interpretations of deafness. Most notably, the film depicts deafness as a burden for the family and a barrier to Ruby achieving her dreams.

It is typical for mainstream portrayals of deafness to pathologize it as a burdensome disability or something that should be “fixed.” This perspective is perpetuated in film and rooted in a history of bigotry and eugenics targeting Deaf people. Feminist disability studies rightly oppose this view and “scrutinize how people with a wide range of physical, mental, and emotional differences are collectively imagined as defective and excluded from an equal place in the social order.”

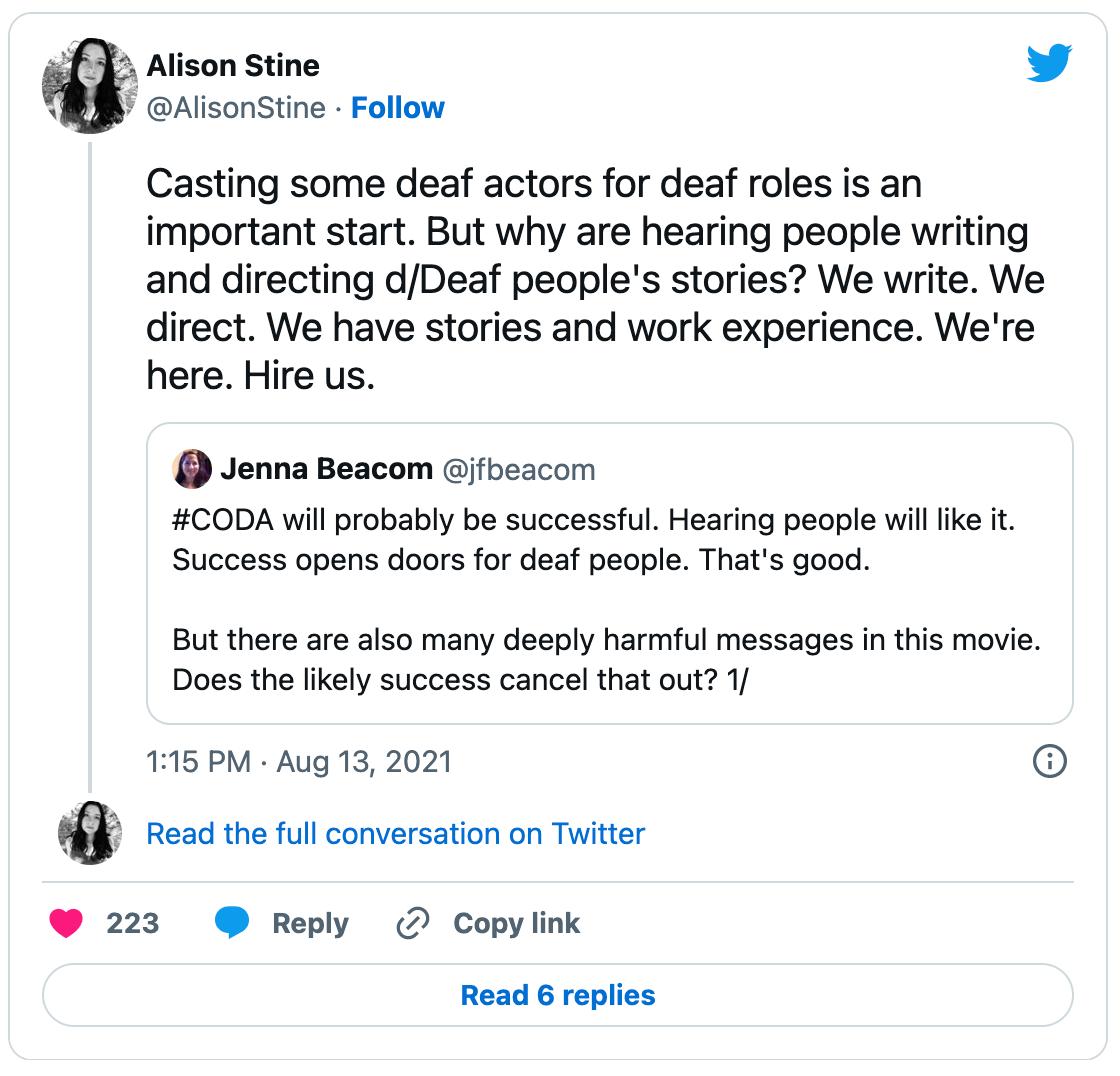

The damaging messages about deafness present in this film can be partially attributed to the fact that CODA was directed by Sian Heder, a hearing woman. The hearing authorship of this film is evident to Deaf viewers. In an interview for the New York Times, Leala Holcomb, a 34-year-old Deaf and nonbinary individual, declared:

Many other Deaf folks agree with this assessment, including Jenna Beacom, a deaf writer and activist. In her notes on the film, she points out many details that show CODA is made by a hearing person for hearing people. These details are examples of how CODA perpetuates the “hearing gaze.”

Similar to the male gaze in feminist film analysis, the hearing gaze refers to when Deaf people in film are viewed through the eyes of a hearing person.

said: time out. This is not right. It’s not authentic and it’s not going to work. If you go down that route, I’m out, because I don’t want to be part of that effort of faking deaf. I’m glad they listened. ”

-Marlee Matlin in an interview for The Guardian

“It’s so obvious that the movie is not written by a Deaf person.”

This can be intentional—like the scene in CODA with a joke about herpes geared toward non-signers. The joke implements inauthentic ASL that is overdramatized and oversexualized so hearing viewers can get a laugh out of how funny the sign looks— even though it is nothing like the real sign for herpes. Though this joke appeals to hearing viewers, it may fall flat or disappoint Deaf viewers, as it did for Beacom.

Other instances of the hearing gaze are unintentional, coming from a lack of education about Deaf people and the Deaf community. For example, there is a scene in CODA where Ruby’s father touches her throat as she sings, insinuating that this will give him a better sense of what Ruby’s singing is like. According to Beacom— this is an absurd suggestion. Touching someone’s throat would not tell a Deaf person about the quality of someone’s singing.

Another way the film shows the hearing gaze is by overlooking the public accommodations mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 Despite the film’s modern-day setting, this act doesn’t seem to exist in the world of CODA— as evidenced by the scene where Ruby is interpreting for her mom and dad at the doctor’s office. The Americans with Disabilities Act mandates that interpreters be provided at doctors' offices and many other businesses. Perhaps Heder was trying to point out that interpreting services aren’t always provided efficiently, so sometimes CODAs will interpret as a last resort, but the film did not suggest that was the case in any capacity.

Not only did the film have a stark lack of professional interpreters, it hardly showed any alternative means of Deaf communication like lip reading, smart device tools, video relay services, or writing. If Ruby was not there to interpret, they were rendered incompetent. Painting Deaf people as wholly incapable of communicating if they don’t have a hearing interpreter to save the day is an incredibly inaccurate and harmful notion that perpetuates stereotypes widely held by hearing people.

Since hearing people (like me and the director of CODA) have not experienced what it’s like to be Deaf or part of Deaf culture, we are especially prone to accidentally perpetuating the hearing gaze. That’s why it’s so important to consult Deaf people, incorporate their perspectives, be receptive to Deaf critiques, and support Deaf writers and filmmakers.

“It’s such a hearing frame!”

In response to the lack of films with deaf representation, especially representation that projects the hearing gaze, the Deaf community created Deaf Cinema. According to two Deaf filmmakers, Wayne Betts Jr and Chad Taylor:

“Deaf cinema means stories told through the Deaf lens, through Deaf eyes, edited from a Deaf sensibility, and a feel for Deaf rhythm. It is telling stories through a Deaf person, a signing person, or from a Cultural view. In writing a story from a Deaf perspective, you check if it has those characteristics, and if the answer is yes to all, then that is Deaf cinema.”

Deaf Cinema directly opposes the overbearing force of the hearing gaze and allows Deaf stories to be told authentically. If you want to watch a movie involving deafness, watch Deaf Cinema. That’s the best way to ensure you consume accurate and constructive depictions of deafness.

Some Deaf Cinema films you should check out are Deafula, Universal Signs, and Lake Windfall. You can also engage with Deaf Cinema by checking out

Deaf film festivals in your area. This is the perfect way to support your local Deaf filmmakers.

If you enjoy Deaf Cinema or the acting in CODA, keep an eye out for the actors’ latest work. Marlee Matlin recently made her debut as one of the first Deaf directors in mainstream television with her episode of Accused. This 2023 crime drama series was just renewed for a second season. Matlin directed an episode called “Ava’s Story.” The episode follows a surrogate mother who gives birth to a Deaf child and intervenes when she finds out the parents plan to give the child a cochlear implant.

Troy Kotsur, who played the father in CODA, has been cast in an upcoming Disney+ sports drama series about the Cubs Football team, an all deaf team that reined undefeated in 2021. This series’ title and release date have yet to be announced, but we know that Kotsur will play a lead role as the coach of this outstanding team.

Daniel Durant, acting as the brother in CODA, also has some future projects in the works. This February, he hinted at a major upcoming project and told fans to look out for an upcoming film role.

Despite its shortcomings, I hope CODA and its talented Deaf cast have cleared the path for future mainstream films about deafness so that the many skilled deaf filmmakers, directors, writers, editors, and cinematographers can share their art.