goldsmiths.co.uk Discover the world of luxury watches and jewellery from the Watches of Switzerland group with multibrand showrooms across Watches of Switzerland, Mappin & Webb and Goldsmiths. Our

watches-of-switzerland.co.uk

mappinandwebb.com

Discover the world of luxury watches and jewellery from the Watches of Switzerland group with multibrand showrooms across Watches of Switzerland, Mappin & Webb and Goldsmiths.

Our expert teams are here to guide you to find that perfect piece.

watches-of-switzerland.co.uk

mappinandwebb.com

goldsmiths.co.uk

Editor: Christopher Jackson

Editor-at-large: Claire Coe

Contributing Editors:

Emily Prescott, Meredith Taylor, Lord Ranger, Liz Brewer, Dr Paul Hokemeyer

Advisory Board:

Sir John Griffin (Chairman), Dame Mary Richardson, Sir Anthony Seldon, Elizabeth Diaferia, Ty Goddard, Neil Carmichael

Management: Ronel Lehmann (Founder & CEO), Colin Hudson, Tom Pauk, Professor Robert Campbell Christopher Jackson, Curtis Ross, Julia Carrick OBE, Gaynor Goodliffe

Mentors:

Derek Walker, Andrew Inman, Chloë Garland, Alejandra Arteta, Angelina Giovani, Christopher Clark, Robin Rose, Sophia Petrides, Dana JamesEdwards, Iain Smith, Jeremy Cordrey, Martin Israel, Iandra Tchoudnowsky, Tim Levy, Peter Ibbetson, Claire Orlic, Judith Cocking, Sandra Hermitage, Claire Ashley, Dr Richard Davis, Sir David Lidington, Coco Stevenson, Talan Skeels-Piggins, Edward Short, David Hogan, Susan Hunt, Divyesh Kamdar, Julia Glenn, Neil Lancaster, Dr David Moffat, Jonathan Lander, Kirsty Bell, Simon Bell, Paul Brannigan, Kate King, Paul Aplin, Professor Andrew Eder, Derek Bell, Graham Turner, Matthew Thompson, Douglas Pryde, Pervin Shaikh, Adam Mitcheson, Ross Power, Caroline Roberts, Sue Harkness, Andy Tait, Mike Donoghue, Tony Mallin, Patrick Chapman, Amanda Brown, Tom Pauk, Daniel Barres, Patrick Chapman, Merrill Powell, Kate Glick, Lord Mott, Dr Susan Doering, Raghav Parkash, Marcus Day, Sheridan Mangal, Mark Thistlethwaite, Madhu Palmar, Margaret Stephens, John Cottrell, Victoria Anstey, Stephen Goldman, Patrick Timms, James Meek, Dominique Rollo, Tracey Jones, Alan Urmston, Duncan Palmer, James Slater, Charles Hamilton-Stubber, Catherine Wood, Guy Beresford

Business Development: Rara Plumptre

Design and Digital: Nick Pelekanos, Ankita Agrawal, D’Arcy Lawson Baker

Photography: Sam Pearce, Will Purcell, Gemma Levine

Public Relations: Pedroza Communications

Website Development: Eprefix

Media Buying: Virtual Campaign Management

Print Production: Marcus Dobbs

Printers:

Micropress Printers Ltd

Distribution: Emblem Group

Registered Address:

Finito Education Limited, 14th floor, 33 Cavendish Square, London W1G 0PW, +44 (0)20 3780 7700 Finito and FinitoWorld are trade marks of the owner. We cannot accept responsibility for unsolicited submissions, manuscripts and photographs. All prices and details are correct at time of going to press, but subject to change. We take no responsibility for omissions or errors. Reproduction in whole or in part without the publisher’s written permission is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. Registered in England No. 9985173

I always remember with a good deal of pride the Head of City of London School reporting exceptional A level examinations results and University entrance offers to parents. One pupil had turned down both Cambridge and Oxford Universities to gasps of surprise from a packed audience. In a beautifully choreographed moment, the Head then let slip that the pupil was fortunate to have been offered a place at Havard. The Trump administration's plan to bar Harvard University from enrolling international students would be a blow to those who seek higher education in the United States.

For someone who helps others to find employment, I realise that I prefer working for myself. I have been told that I am unemployable. Taking an entrepreneurial route comes with great risks and is not for everyone. Having said that, we are getting more enquiries from school and college leavers and graduates who do not want to work for others and are keen on setting up their own businesses. To cope with this demand, our mentors will soon be providing support to those who wish to furrow their own path. I hope that we will be able to share some success stories in the same way that we feature candidates who secure meaningful careers.

When we started this magazine in the early days of Covid lockdown,

it was unlike any other publication launch. We did not raise money for this publishing venture and fourteen issues later we still have not had a celebration event. Everything we have done has been with slow organic growth, gaining the trust of world leaders, politicians, business leaders and advertisers. The move to a bimonthly edition is in our growth plan.

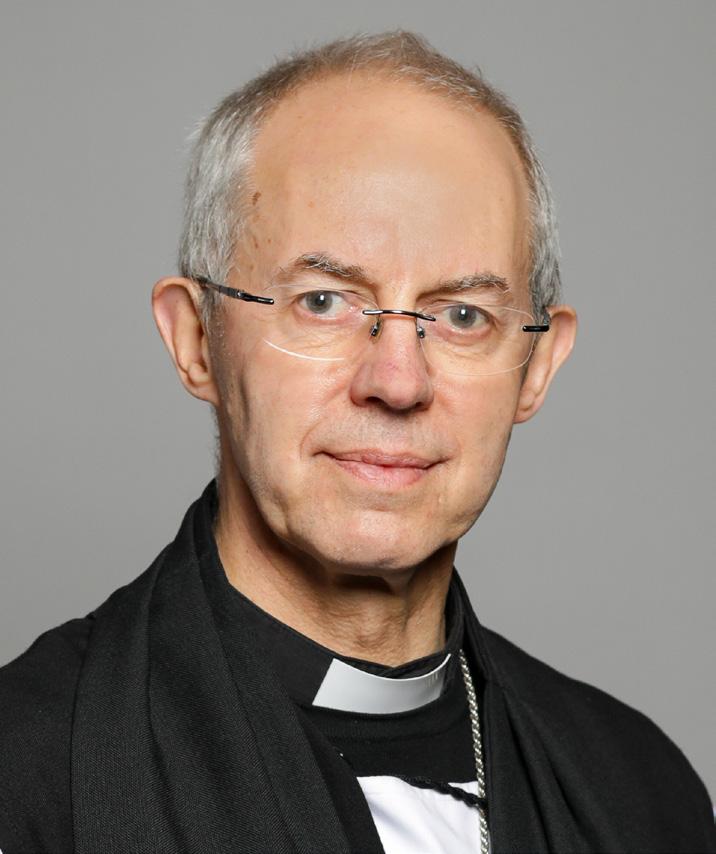

Recently, one of our revered business leaders, Richard Oldfield, felt that we had been unduly harsh in a Leader column about former Archbishop Justin Welby and the Makin Report. Our immediate response was to extend an invitation for the submission of an opinion piece to provide a balanced viewpoint. This was immediately published online and appears now in the magazine.

In contrast, Charlotte Leslie, a former Member of Parliament, subjected us to not one but two Subject Access Requests over two years, asserting that we have been processing significant amounts of her personal data.

Freedom of expression is sacred and the way that responsible publishers deal with complainants, is to invite contributions, not be subjected to vexatious actions.

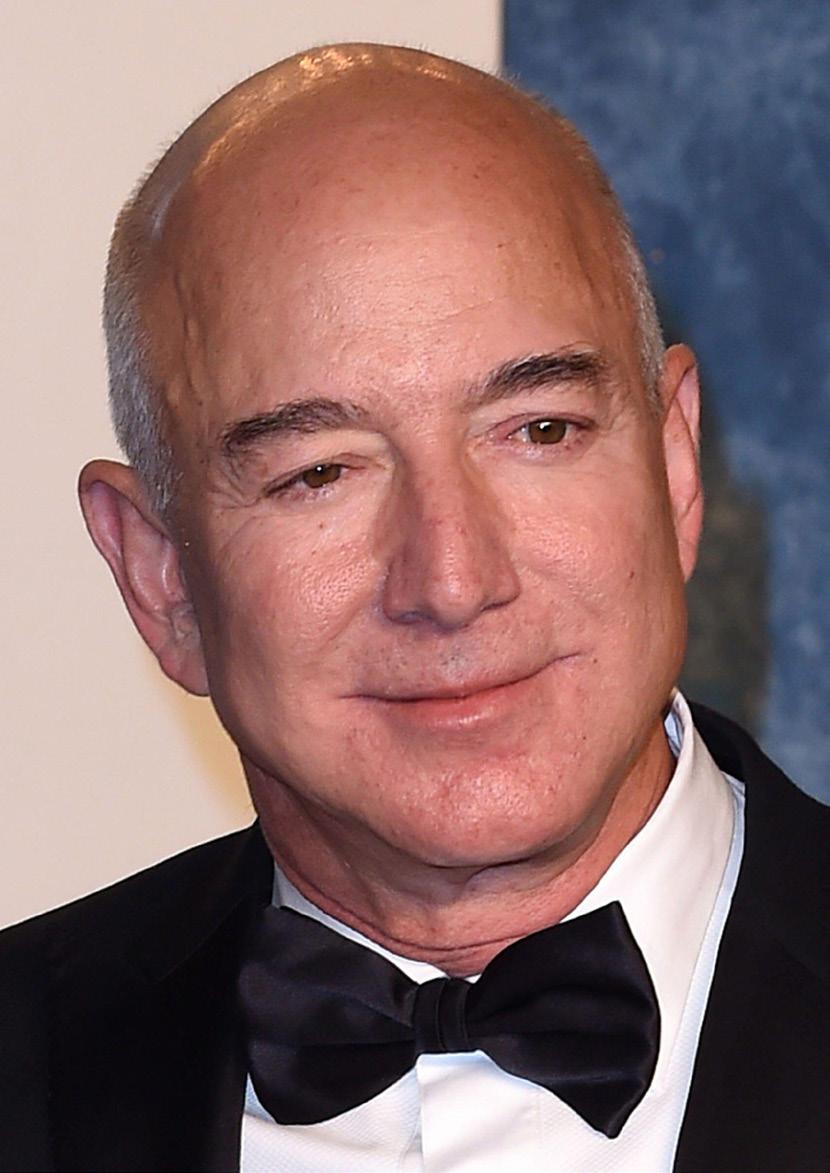

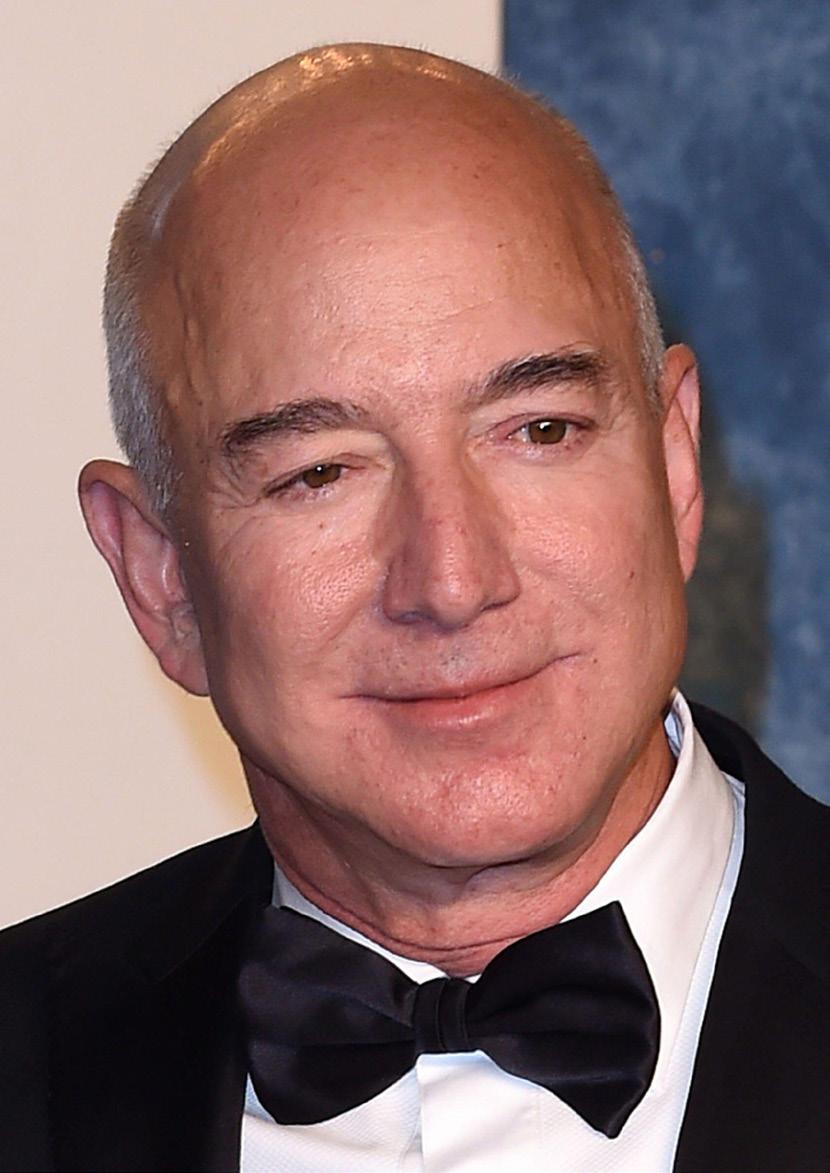

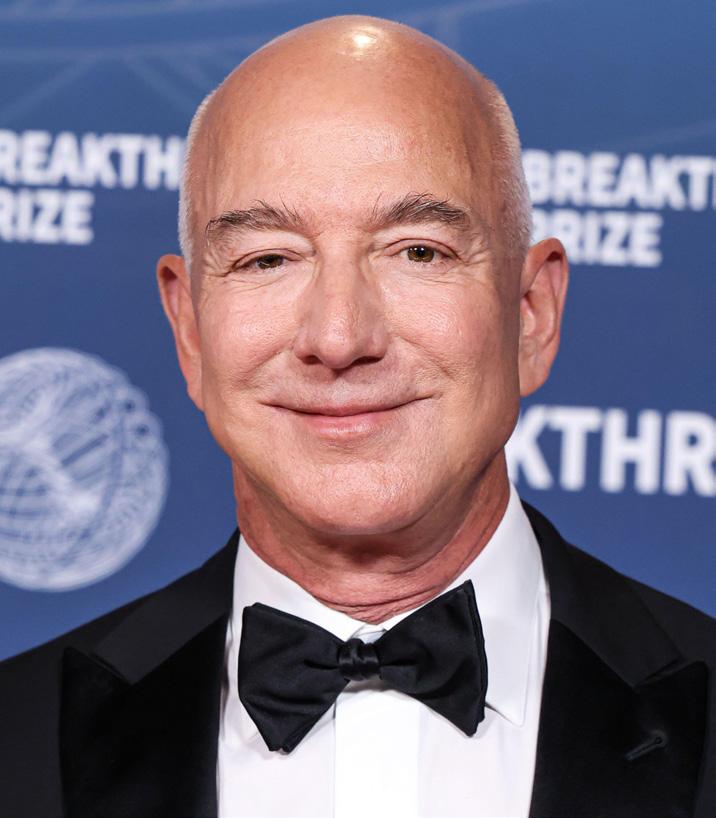

We have always sought to celebrate pioneers who inspire the next generation. Jeff Bezos is one such person. His own “1-hour rule” is simple: no screens, no rushing, just an intentional tech-free start to the day, yet the impact of Amazon is so profound and felt across the world. It may be that we will be revering Greg Meredith, who appears on page 68 in the same vein. Remember that you read about F1R3FLY here first.

As the new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) gets into full swing, Elon Musk appears to have overtaken President Donald Trump as the least popular American from the Democrats’ perspective. But as interesting as the items being cut from the federal budget is Musk’s methodology: as before at Twitter, he is giving a lot of power to very young people.

What’s interesting is that a hierarchy that has nothing to do with age suggests meritocracy. Among Musk’s team are Akash Bobba, 21, Ethan Shaotran, 22, Luke Farritor, 23 – and the youngest of them all, Edward Coristine, aged 19.

Some news outlets have expressed dismay at the youth of the people now called in to mark the homework of seasoned civil servants. But it’s a reminder that the middle-aged don’t necessarily have a monopoly on intelligence. Take Farritor as an example: he won part of a $700,000 prize in 2024 after using AI technology to help decipher a 2,000-year-old document, which was thought to be burnt beyond repair.

The traditional view is that human beings begin in ignorance and therefore need to be educated. Naturally, this is the case with children, but when does it cease to be true?

Well, even then, received wisdom says, eighteen-year-olds might all have varying degrees of intelligence, and some of them may be very smart indeed – but even then, the argument runs, wisdom still won’t have been generated. That takes decades of lived experience. Leadership roles are therefore better

assigned to people of a certain age, who have attained the higher level of being that this implies - usually brought on by such things as marriages, children, divorces, and not easily being able to ascend stairs.

Very often, that view of life will prove true. We rightly consider some of our great leaders to have brought to the table the additional perspective that the years bring. Sir Winston Churchill is frequently lambasted for being the architect of the Gallipoli disaster, among many other things, but his long service made him the Churchill who stood firm in 1940: we revere him because he learned from his mistakes.

In America itself, there are signs that this has gone too far. The image of the father – as in the Founding Father – is woven into the fabric of the nation and reaches its perfection in the mysterious figure of Abraham Lincoln. But over the years, the notion that wisdom can only emanate from the old is beginning to look somewhat tired. Nobody was ever certain that Ronald Reagan was at his sharpest during his second term; Joe Biden was almost certainly in no state to govern from day one of his presidency. This makes Musk’s band of waste-cutters a timely symbol of a new chapter.

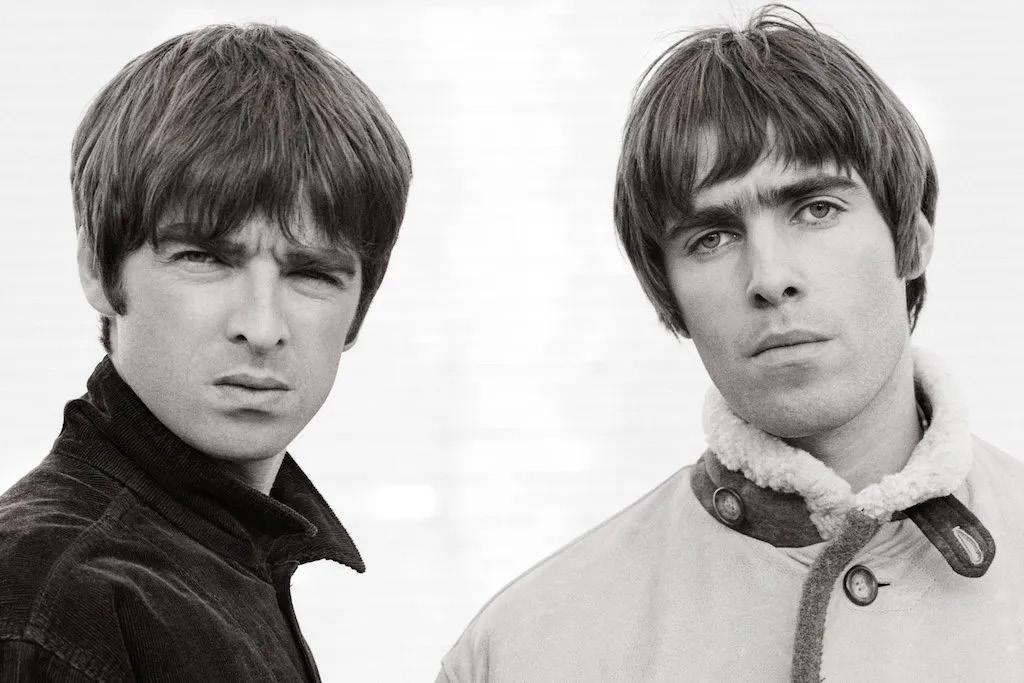

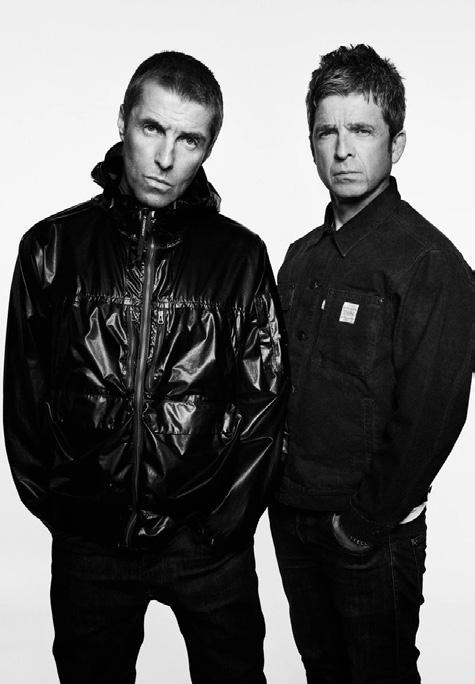

What can we learn from this in our own business lives? The young, of course, bring an energy that the middle-aged know all too well doesn’t come twice. We see this most particularly in popular music, where to be 30 is to be past one’s sell-by date. Taylor Swift, cheered last year at American football, was booed this year. The switch doesn’t always flip quite so

swiftly as it does for the mega-famous. It was Sir Kingsley Amis who said he hated reading the young because they were saying: “The world’s not like that anymore; it’s like this.” We’re aware of a privilege that the young have: to define their own generation and, in so doing, to issue some sort of rebuke to the previous one.

Rigid hierarchy can lead to the ossification of any collective structure. Energy gets trapped low down in the organization. Whatever one thinks about Musk, there is something to be said for the way in which he is prepared to use the best people he can find for the job. Another tech giant, Jeff Bezos, has spoken in the past about the importance of the least senior person in the meeting being the first to speak. “You want to set up your culture so that the most junior person can overrule the most senior person if they have data,” he says.

The enemy of creativity and imagination is groupthink, and very often, groupthink emanates from the limits we place on ourselves because of how we appear to one another, whether that be age, gender, or skin color. We may not like what Musk is cutting, and we may even sometimes wonder if he’s not a bit bonkers, but a cursory look at Tesla and SpaceX will tell you he gets results. As productivity in the UK continues to dawdle miserably along, we’d be foolish to claim we have nothing to learn from him.

To be quietly useful is therefore as good a New Year’s Resolution as any. Besides, not to be useful can come back to you quicker than you may imagine, as Reeves and Trump may well discover.

Inthe usually choreographed world of Oval Office meetings, the recent heated exchange between Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and former President Donald Trump provided a rare glimpse of authentic political discourse.

As CNN reported, “the tense meeting quickly escalated into an argument about the ongoing war in Ukraine,” with Trump reportedly telling Zelensky, “I don’t think you’re doing enough to achieve peace,” while Zelensky responded that Ukraine was “fighting for its very survival.”

There was something oddly refreshing about this diplomatic departure from script. In an era where political interactions are meticulously stagemanaged, seeing genuine emotions surface – frustration, conviction, even anger – reminds us that behind the polished facades of international relations are actual human beings grappling with complex problems.

The Washington Post noted that “staffers appeared visibly uncomfortable” as the discussion grew heated, with one aide describing the exchange as “brutally

honest in a way we rarely see in diplomatic settings.” Marco Rubio looked like he wished the sofa he was sitting on contained a trapdoor. Yet this discomfort itself speaks to our collective aversion to confrontation, even when it might serve a productive purpose.

As in our personal and professional lives, political confrontations need not spell disaster. Psychotherapist Esther Perel observes that “conflict is growth trying to happen,” and perhaps the same applies to international relations. After the initial heat of argument comes the cooling-off period, where reflection can occur and new understandings may emerge.

The New York Times reported that following the meeting, both men “appeared to have reached a better understanding of each other’s positions, though significant differences remained.” This trajectory – from confrontation to reflection to potential progress – mirrors healthy conflict resolution in any context.

In our professional lives, we often avoid necessary confrontations. Management consultant Peter Bregman points out that

In“avoiding difficult conversations is actually increasing your stress, not reducing it.” We fear damaging relationships or creating awkwardness, yet skillful confrontation can strengthen bonds through honesty.

Leadership expert Susan Scott puts it succinctly: “The conversation is the relationship.” By this measure, the frank exchange between Zelensky and Trump may have actually improved their relationship by establishing authentic communication.

While decorum has its place in diplomacy, occasionally breaking through the veneer of politeness allows for genuine engagement with the high-stakes issues at hand. As philosopher Hannah Arendt noted, “Politics is based on the fact of human plurality,” which necessarily involves disagreement and its expression.

Perhaps we should view such moments not as diplomatic failures but as rare instances of political truthfulness –uncomfortable, messy, but ultimately more productive than perfectly staged photo opportunities that mask fundamental disagreements.

May, Finito World once again played host to an important national conversation - this time on the subject of food in schools. The venue was the Gielgud Theatre, a place of imagination and storytelling, but also of timely seriousness, as Tim Clark launched his fourth school improvement report.

This latest offering, supported by Finito and introduced by Sir Anthony Seldon, stands out for its courage. Rather than simply listing reforms, Clark invites rigorous debate. Are free school meals the responsibility of the state or

parents? Should we fund breakfast clubs more effectively? Can school meals realistically impact national health, when children spend most of their lives beyond the school gate?

These are not easy questions - but Clark does not shy away from complexity. His report examines everything from the inconsistencies in FSM eligibility across the UK to the troubling correlation between food insecurity and children in alternative provision. The tone is pragmatic, never polemical, and always child-focused.

Clark’s work highlights a central truth: food in schools is not just about nutrition, but about dignity, equity, and opportunity. With NHS obesity costs hitting £11.4 billion, the economic case is there. But more important is the moral one.

In bringing this to the fore, Tim Clark is performing a vital public service. His voice - thoughtful, questioning, persistent - is one our education system needs now more than ever. We at Finito World salute his clarity, his courage, and his commitment to the next generation.

3 FOUNDER'S

6 LEADERS

10 DIARY

Baroness Morgan of Cotes

12 MEET THE MENTOR

Matt Thompson on guidance that matters

20 THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER

Boris Johnson on leadership, legacy, and levelling up

21 THE ANGLICAN

Richard Oldfield defends Welby

22 THE CEO

Karen Jones on the highs and lows of running a business

24 THE DIPLOMAT

Baroness Ashton of Upholland on Syria and global diplomacy

26 A QUESTION OF DEGREE

Tom Dawson on reshaping the school day

28 RELATIVELY SPEAKING

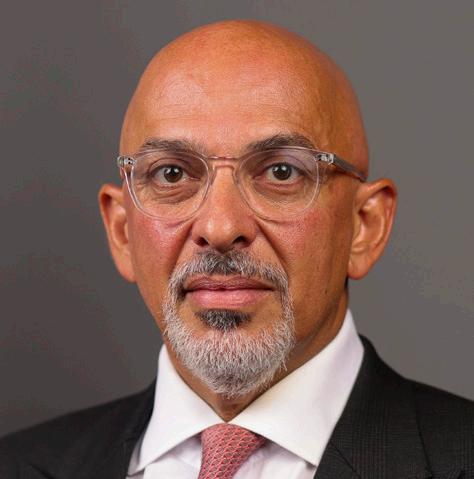

Nadhim Zahawi’s journey from Baghdad to Britain

30 TOMORROW’S LEADERS ARE BUSY TONIGHT

Zaf Bhunnoo and the future of e-scooter racing

32 10,000 HOURS

Sandro Forte’s extraordinary career in financial planning

34 THOSE ARE MY PRINCIPLES

Kamran Razmdoost on inclusive leadership

36 EVENT REPORT

A one-way ticket to Antigua

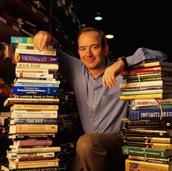

46 THE BEZOS BLUEPRINT

How Jeff Bezos mastered the long game

64 AMAZON AGE

Inside the empire that changed the world

68 INTRODUCING F1R3FLY

Ancient wisdom for modern success

78 BUDDHA’S GUIDE TO WORK

Ancient wisdom for modern success

86 EDUCATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST

How the Gulf is leading the way in EdTech

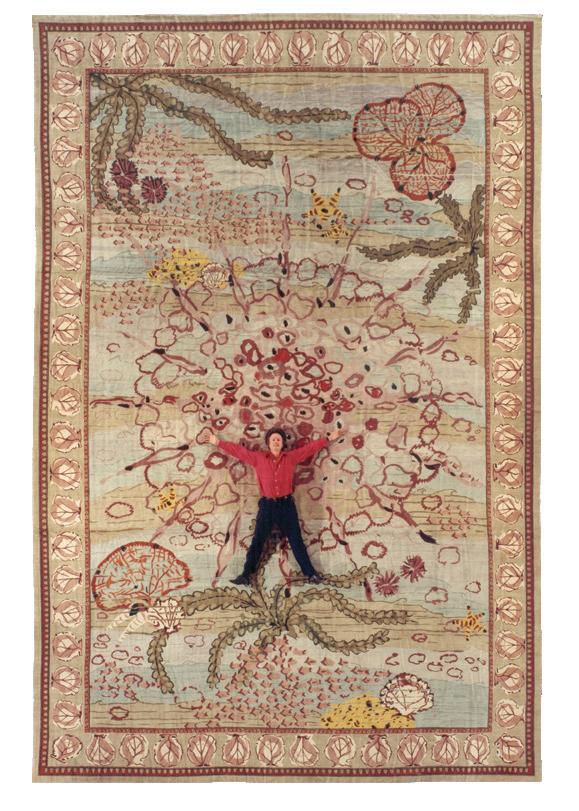

90 SIMON CUNDEY

Heritage cut with precision

LUNA BENAI

Jewels with depth and daring

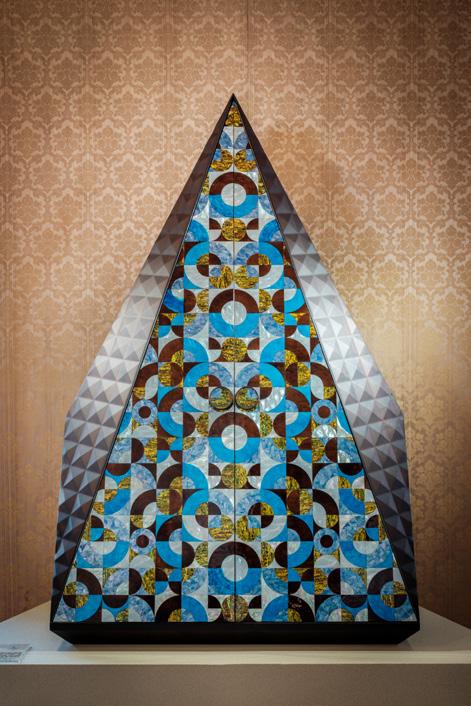

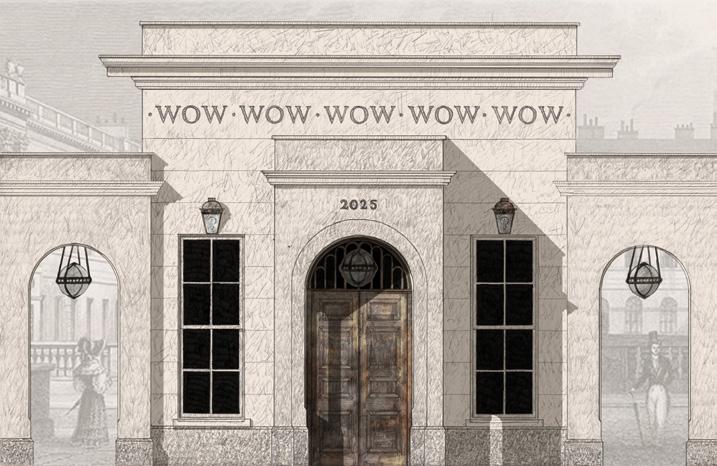

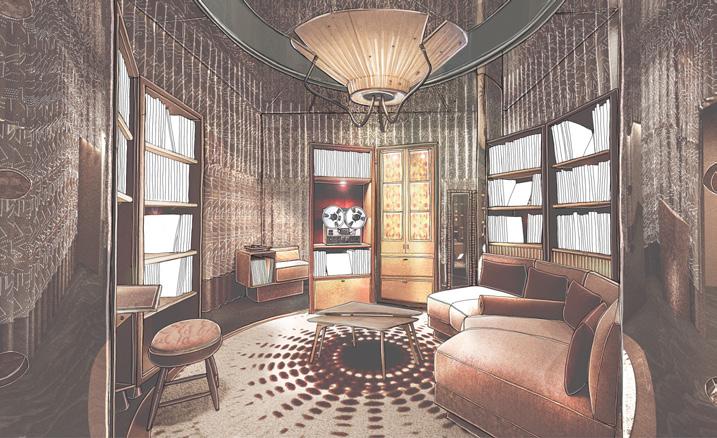

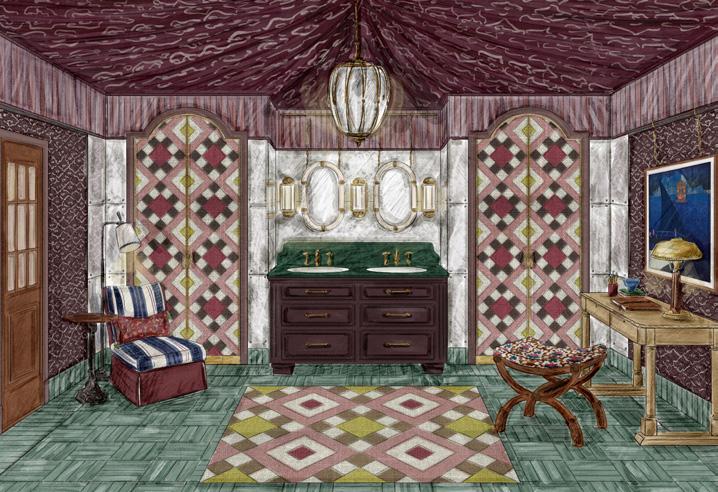

98 DESIGN CENTRE CHELSEA

Where interiors find their voice

102 A ROYAL LEGACY

How King Charles’ charity is shaping the next generation

104 BACKING BRIGHT FUTURES

Ollie Nicholls on the power of bursaries to change lives

108 LETTER FROM IRAN

Lord Lamont’s reflections on a changing Middle East

110 LETTER FROM NORTHERN IRELAND

Lord John Alderdice on the region’s uncertain future

The peculiarities of official paperwork mean I remain "Mrs. Morgan" on a variety of documents. While I’ve long since transitioned away from frontline politics, certain things are easier left unchanged. Much like the title, I continue to navigate multiple roles: non-executive director, media commentator, and now Chair of the Advertising Standards Authority. Each day is a patchwork of engagements - some political, some corporate, and occasionally, the odd foray into public speaking about careers and governance.

One of the great blessings of 2025 is that it will be a year free from general election speculation. For those running businesses, sitting on boards, or simply trying to lead a quiet life, this stability allows for proper planning. The question facing this government, however, is straightforward: can they get a grip? They had ample time to plan, yet the execution appears patchy. A more orderly No.10 is a step in the right direction, and Sir Chris Wormald’s appointment as Cabinet Secretary should provide much-needed discipline in decision-making.

With France in turmoil, Germany facing economic headwinds, and America consumed by its own dramas, the UK has the chance to position itself as a rare beacon of stability. The Investment Summit last October demonstrated that global businesses are still eager to bet on Britain - provided we offer a clear, credible strategy for growth. Whether we seize that moment remains to be seen.

Asubject close to my heart, the education system remains in flux. The government’s curriculum review is underway, and while change is necessary, it must be handled carefully. Young people today need an education that prepares them not just academically, but for the realities of modern work. Meanwhile, renationalisation is back - at least in the world of rail. The hope is that this will finally lead to trains that run on time. Skepticism is healthy, but infrastructure decisions send signals far beyond passenger experience. If we can’t run a punctual rail service, what does that say about broader governance?

Few were surprised that Donald Trump won the U.S. election. Electorates worldwide are fed up with politicians over-promising and under-delivering. The business world has long known that results matter, yet governments have been slow to grasp this principle. Trump’s re-election raises questions about America’s role in global security, particularly in relation to NATO and Ukraine. European nations are finally realising they must invest in their own defence. Whether NATO emerges stronger or fractured will be a defining issue of 2025.

Jon Sopel (Wikipedia.org)

Wikipedia.oeg

highlights global unease. The online world has evolved into an unregulated social experiment, reshaping attention spans, mental health, and even democratic discourse. How we manage its impact on future generations will be a defining challenge for policymakers, tech firms, and parents alike.

IOf there’s one issue I remain deeply invested in, it’s online safety for young people. The Online Safety Act was a significant step forward, but enforcement and adaptation remain challenges. Australia has banned social media for under-16s - an approach that raises logistical questions but

ne of the more surreal moments of my career transition came in late 2019. After a Thursday night spent dissecting the general election, I assumed I was done with front-line politics. By Friday morning, I found myself on Have I Got News for You. By Monday, I was taking my teenage son Christmas shopping when Boris Johnson called. He asked if I would continue as Culture Secretary and move to the House of Lords - so much for my carefully planned exit. Lesson learned: when asked to serve, always be prepared to say yes.

Empower your school community with innovative digital tools that support teachers, engage students, and help every learner reach their potential - an essential solution in today’s world, where technology complements teaching, not replaces it.

WITH A BACKGROUND SPANNING MARKETING, AUTOMOTIVE, AND LEADERSHIP, MATT THOMPSON BRINGS CLARITY, WARMTH, AND HARD-WON INSIGHT TO HIS WORK AT FINITO. HERE, HE REFLECTS ON THE ROLE OF PASSION, THE PITFALLS OF MODERN RECRUITMENT, AND THE QUIET POWER OF MENTORING

Q: What is your educational background and early career history?

A: Growing up, we had to count every penny. I was fortunate to gain an Assisted Place at Loughborough Grammar School, where I made lifelong friends - an opportunity that later led me to study Modern History at UCL. University was free back then, which made a huge difference. My education gave me an early understanding that success is rarely achieved alone; it takes hard work, smart choices, a good team, and sometimes, a little luck.

Q: Was there a clue early on that you’d end up in the sector you’re in?

A: My other lifelong passion, even as a child, was cars and trucks. I had a sizeable Matchbox collection and could identify almost every vehicle on the road - something I can, rather embarrassingly, still do. That early interest stayed with me and later became the foundation of a career in the automotive industry.

Q: Tell us a bit about your career and what’s shaped you.

A: Professionally, I’ve worked across multiple businesses in marketing roles - covering cars, tyres, and trucks -

both in the UK and abroad. My early years with the Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM) gave me structure and professional confidence. Looking back, I’d say the qualities that shaped my career were simple: curiosity, ambition, a willingness to listen, and the courage to make bold choices - even if they didn’t always work out.

Q: What role has passion played in your success?

A: One constant through all of this was passion. My love for the automotive world provided a thread of continuity across six different organisations and helped me through challenging periods. Passion doesn’t just sustain you - it often powers your best ideas and unlocks the most successful moments.

Q: How do you approach mentoring at Finito?

A: That’s something I try to pass on in my mentoring at Finito. I encourage candidates to identify what really excites them. Passion makes people memorable in interviews. It fuels preparation. And more importantly, it tends to lead to a more fulfilling career. Helping young people find that internal compass is central to what we do.

Q: Did you have mentors in your own career?

A: I’ve had mentors throughout my life - some formal, many informal. In truth, the most valuable mentors weren’t always the ones assigned to me. They were directors, colleagues, even friends, who gave their time generously and offered real-world insight. Mentorship, to me, is about engagement. It’s not about having all the answers - it’s about listening, asking the right questions, and tailoring advice to the person in front of you.

Q: How do you define mentoring success?

A: That’s especially important at Finito, where no two candidates are the same. Everyone arrives with their own

background, ambitions, and challenges. A one-size-fits-all model doesn’t work. The key is patience, and above all, good listening.

Q: What do you think about the state of marketing today?

A: My work in strategic marketing has also shaped how I guide candidates. I believe today’s marketing landscape suffers from an obsession with digital tactics - clicks, impressions, ROAS - often at the expense of the bigger picture. We’ve lost sight of foundational elements like brand development, customer insight, and long-term value creation. “Digital” should be an important part of the story - not the whole story.

Q: What advice do you give to young people interested in marketing?

A: I try to help candidates think about marketing in three parts: first, diagnose the problem strategically; second, build a tailored strategy; and only then, third, execute tactically. Most people jump to tactics, skipping the crucial first two steps. The best marketers strike a balance between analytical thinking and creativity - and that balance is more important now than ever.

shows up in the over-reliance on tools and metrics, and the under-emphasis on customer empathy, long-term thinking, and strategic creativity. For candidates who do understand those things, it’s a real opportunity to stand out.

Q: What common mistakes do you see from young job seekers?

A: One of the most common mistakes I see in early career paths is over-reliance on “easy apply” platforms like LinkedIn or Glassdoor. Clicking a button is not a strategy. If a job really matters, the application process should reflect care and thought. You need to research the company, understand their values, and clearly articulate how you can contribute. It’s amazing how rare that is.

Q: If you could go back and advise your younger self, what would you say?

A: If I could go back and offer one piece of advice to my younger self, it would be this: don’t try to map your entire career in advance. Life doesn’t work that way. Careers evolve, sometimes unexpectedly, and that’s a good thing. I wish I’d travelled more. I wish I’d been more strategic in balancing spontaneity with long-term thinking. But mostly, I’d remind myself: it’s not about knowing every step - it’s about staying curious, staying open, and following what energises you.

That’s still how I try to live - and how I try to mentor, too.

What challenges do you see in the field today?

A: One growing concern is the number of people in marketing without formal training. In the U.S., less than 30% of people working in the field have studied marketing. That

Q: What do you think about the current state of recruitment?

A: Recruiters, too, need to improve. Too often, candidates hear nothing back. That’s not just rude - it damages a company’s reputation. We wouldn’t treat potential customers this way. Why do we treat job applicants differently?

Q: How can tech help - not hinder - the recruitment process?

A: I believe technology, including AI, should help humanise the recruitment process - not replace it. Simple things like acknowledgment emails, realistic timelines, or even basic feedback can make all the difference. Respect goes a long way.

BORIS BIKES AGAIN? Johnson on comebacks, cock-ups, and 2028

KEEPING UP WITH THE JONES Karen Jones on business battles, burnout, and bouncing back

THE SYRIA FILES Baroness Ashton’s advice to young diplomats

FLAGSHIP STORE LONDON

Second Floor, South Dome, Design Centre, Chelsea Harbour, London, UK

london@turri.it / Ph +44 0208 067 9111

IT A LIAN PERFECTION. SINCE 1925

Looking back on it all, I was very lucky. When I was first asked to be Mayor of London, I said no. Why would I do that? I had the safest seat in the country, I was enjoying being an MP, why would I want to? But I was told, no, you would win it - and I did. Being Mayor of London was a fantastic experience. We brought real change to the city - policing, transport, infrastructure, and of course, the 2012 Olympics, which was an extraordinary triumph for the country.

The idea of levelling up, the potential of the UK is everywhere, but the concentration of wealth, power, talent, productivity is overwhelmingly still in London and the South East. And in that respect, the UK is unlike many other major economies - we are much more imbalanced. That is why I wanted to take this vision nationwide. The whole country has talent, but we need to make sure opportunities are spread fairly.

I was very lucky. All politicians have those ‘could have, would have, should have’ moments. But actually, I then spent 15 years in frontline politics - whether at City Hall, the Foreign Office, or Number 10. I was able to do a lot of the things I really cared about, so I can’t complain.

They basically thought, well, old Johnson bangs on about it so much, and he seems to have a view about what it should be - let’s give him a go. Brexit was in deadlock when I took over in 2019. We told the public we were going to deliver it, but we couldn’t, and Parliament wouldn’t do it. We had basically got ourselves into

a total jam. So they turned to me, and we got it done.

The problem now is that today, you’ve got an absolutely appalling situation - classic situation engendered entirely by this Labour government - in which the bond markets are starting to demand ever higher yields on British gilts because they can see no clear economic strategy.

It’s a wonderful job. But in politics, it’s a Darwinian process. If you fail to manage your backbenchers, as I probably did, you’re going to come a cropper. You’ve got to have all the things lined up.

People ask me if I’ll ever return to frontline politics, but my chances of becoming PM again are about as good as being blinded by a champagne cork, locked in a disused fridge, or decapitated by a frisbee.

That said, it’s the job of people like me to try to be useful. If I can contribute ideas, if I can help push forward the things I believe in - then that’s what I’ll do.

The only point that the Conservatives need to make, and Kemi needs to make between now and 2028, is that if you want to end this socialist madness, this craven left-wing high-taxing nonsense, there is only one way to do it, and that is to vote Conservative.

I like Kemi Badenoch’s intellectual impatience. I think she’s got a lot of energy. Let’s face it, she’s got a massive opportunity.

People keep asking about Reform UK and Nigel Farage, but my view is, when you’re in a political contest, you don’t talk about your rivals. You talk

about yourself and what you can offer the country.

I competed against the party you mention in one guise or anotherwhether it was UKIP or whatever - for decades as an MP. They didn’t even stand against me in London, I don’t think, and they were on zero per cent or less than 3% when I was PM. Even right at the end, they were nowhere. Don’t talk about them, don’t escalate them.

We should talk about ourselves. What are we going to do? How are we going to fix the immigration problem? What are we going to bring to government? The UK depends hugely on international investment in our debt. The bond markets can see there is no real economic plan from this government. That’s where Conservatives are strong, and that’s where we should be thumping every single day.

The Makin Review, which led Justin Welby to resign as Archbishop of Canterbury in October, is a horror story. John Smyth beat young men with ferocious violence over several decades. Smyth’s victims suffered appallingly and many continue to suffer. But the editorial comments on Welby in the last edition of Finito are unfair, particularly about the necessity to ‘face up to the reality that the Archbishop of Canterbury felt the appearance of his function was more important than the function itself’.

Few people who know him would doubt that he worked extraordinarily hard, did his best to hold together an unholdable-together Church of England and Anglican Communion, and had a very high view of his personal responsibility in everything he did.

Welby himself has acknowledged, most recently in his interview with Laura Kuenssberg, that he ‘got it wrong’, ‘needed to resign’, is ‘utterly sorry and feel[s] a deep sense of personal failure’. He also apologised immediately for the idiotic ad lib comment in the House of Lords that his diary secretary was the one to pity: stung by his vilification to make this valedictory speech, he should have stuck carefully to a proper script.

Senior churchmen – with the admirable exception of the Bishop of Dover, Rose Hudson-Wilkin – have not defended him from being on the receiving end of limitless blame and opprobrium. In their behaviour towards him they seem anxious to protect the institution of the Church– ironically an accusation that the Makin Review makes about

the Church’s conduct – rather than to behave justly.

Makin made criticisms of Welby under three headings: first, that having known Smyth in the 1970s he must have known what he was up to; second, that he did not enquire vigorously enough about the investigation into Smyth once the horrible saga was reported to him while Archbishop in 2013; and third that he should have agreed to meet victims earlier than he did.

The first of these is speculative. Welby attended several of the Iwerne camping retreats at which Smyth was one of the leaders. As the Smyth victims rarely told anyone what was happening it is perfectly credible that others around at the time did not know – especially at the Iwerne camps where apparently Smyth did not abuse boys as he did on the fringes of Winchester College. The Makin Review concludes at one point that ‘on the balance of probabilities, it is the opinion of the Reviewers that it was unlikely that Justin Welby would have had no knowledge of the concerns regarding John Smyth in the 1980s in the UK’; but later concedes: ‘That is not the same as suspecting that John Smyth had committed severe abuses.’

The second rests largely on Makin’s finding that, although Smyth was reported to the police in 2013, this report was inadequate – it was just a ‘referral’ – because those reporting were not given a crime number. Makin noted that Welby was told by his staff in 2013 that ‘the matter is being dealt with, the Police have been notified and a letter has been sent to the appropriate Bishop in Cape Town’ (where Smyth now was living). With the benefit of hindsight

Welby says that he ‘should have pushed harder’. But it was reasonable and proper for him, having been told that it was in police hands, to expect them to get on with it without interference. Welby should have met victims earlier, and was badly advised that to do so might get in the way of the police investigation. Some feel a sense of personal betrayal on that count. He should not have had to resign, but it became almost inevitable on the morning of an avalanche of adverse editorials and opeds. He was then treated disgracefully, above all by The Christian Society which publicly announced that it could not accept the Welbys’ personal Christmas donation, as though Welby were himself Smyth. He was not responsible for the horrors inflicted on Smyth’s victims, and he did not cover up. His resignation should be regarded as a reflection of his integrity rather than the reverse.

THE CEO OF CITYWEALTH GIVES HER TIPS ON HOW TO BE A CEO – AND HOW NOT TO BE

BUSINESS: A BATTLE WORTH FIGHTING?

Let’s start with a scene: the Luddites raging against the machine, plug-pulling protestors, the endless battle of business in a world that rarely plays fair. If you’ve ever been in business, you know this fight intimately. It’s a game of endurance, resilience, and - let’s be honest - a touch of madness. As I celebrate twenty years as a founder, it felt time to deconstruct the mirage that it’s all fun at the top.

THE POOL OF HELL: WHY YOU SHOULDN’T JUMP IN THE DEEP END

You wouldn’t leap into a pool if you couldn’t swim, would you? Yet, time and time again, bright-eyed entrepreneurs hurl themselves into business ventures without the lifeline of deep pockets or even a basic understanding of cash flow. I can attest to this being me. And so, they drown. The survivors? They learn the discipline of business, that the tax man is all powerful, that paperwork can gather dust, but it won't go away and that preparation along with permanent, risk horizon scanning helps. As well an acute awareness that even those with deep pockets can lose it all. Fearlessness, unreasonable and unfounded positivity and a large dose of stupidity also help.

In the words of Mike Tyson, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.” It is a famous and perhaps throw away quote now but being in business sometimes feels like being repeatedly punched in the face. And business will punch you. Hard. The key? Get up. Again and again, wipe the

blackboard clean and prepare a new set of chalk. You learn to structure your business like a military operation and learn to know when to retreat -you can't win 'em all, and understanding that “collateral damage” often means staff morale, failed products, or investments that should have stayed ideas. A sound bit of advice a coach once charged me a lot of money for was "have less ideas." I only wish I could have listened.

Malcolm Gladwell and Thucydides knew it - humans love a good story, especially if it justifies failure. Sales not happening? It must be the product. Database is wrong? No, it’s the software not the lack of care. No one asks, “What if it’s me?” Instead, blame is shuffled like a deck of bad poker cards. The truth? Sometimes the problem isn’t what you think. Instead of assumptions, just say, “I don’t know. Let’s find out.” I read a book called The Tools some time ago and it was eye opening in that humans have a predilection to find an answer to every situation - to fit a round story into the square hole. Once you know this, it means research and investigation into almost everything as well as "ask the client" feedback forms, then, actually doing something about it, not just listening to another set of stories to maintain inertia. How anyone actually makes any money in business can sometimes be one of life's great mysteries.

Ah, the siren call of innovation. Businesses pile up software, systems, and shiny new tools like dragon hoarders, convinced

they’ll use them all. They won’t. The mirage of the CRM system, the analytics, the payment software, all golden ground to improve your business. Well, that would be the case if they didn't have downtime; such complicated ways of working that expensive talent and skills are what you really need, not more software and integrations that rarely work together. The nonsense that some of the software systems present as fact is also one of life's great mysteries. You realise that they, as you, are indeed, just running a business with all the punches that it entails.

You start with wild dreams, JV partnerships that never materialise, and a belief that funding is the answer. But soon, you’re just another worn out business leader, chasing money, battling taxes, and realising that cash flow is a cruel mistress. Feast and famine cycles drain creativity. Even your accountant, who should be an ally, simply asks, “Are you doing this again next year?” (Translation: Do you still have the stomach for it?). Founders are cool right? Well, get a bunch of them in a wine bar and they all sing from the same song sheet entitled 'it's lonely at the top'. There are not many people who understand the balancing act, the plates spinning and how to catch them when they frisbee off. Clue, it usually entails scraped knees.

Business is personal. Shutting down a product people love? Heartbreaking. But some things don’t work, and sentimentality is a luxury you can’t afford although often afford it you do, for way longer than makes any sense. The same goes for some

staff ideas - brilliant on paper, costly in reality. Worse still, when things go wrong, responsibility is rarely claimed, but pay rises and bonuses are still expected. I read an interesting article in Harvard magazine some years ago which nailed this exact problem. The essence was that once an investment in a product hits a tipping point it's hard to turn back because of the money that will be 'lost' and emotional investment, but they recommend, losing it immediately, cut your losses and get out as fast as you can. Take the hit and get over it. Fine to say but relighting the fire in a team who see it as personal failure, takes a lot of pushing the rock up and over the hill again.

Ever wonder why artists are remembered but business people aren’t? Perhaps because success in business is a mirage, constantly shifting, never truly within grasp. The assumption that money flows endlessly - ask Al Pacino or Muhammad Ali - has seen even the greats go broke. And women? They face a different battlefield almost, it could be called modern-day slavery while they are apparently 'having it all' - working all hours god sends and then balancing the burden of home with children, animals and elderly relatives, and still with unequal pay. Founders of course can create their own schedule but paying yourself does come with ups and downs as you ride the business pony and sometimes have to tighten your belt. It can also kill relationships, make you exhausted and never seem to have an end point. I always say, 'it will still be there in the morning' of working late. And if that work isn't then, sure enough some other work will soon arrive.

So, what’s the key? Structure. Reputation. A ‘good enough’ point, where perfection gives way to practicality. I learned that at London Business School and it is

something I live by. Don't endlessly fiddle with projects, get them out and refine them along the way. When dealing with staff, listen - not just to the loudest voices but to all. And always remember to laugh at yourself, even I think physically laughing can reset a mood. Make friends with fellow business owners in the same boat for morale support and to provide key advice that you can trust implicitly at key moments of frustration or difficulty. Have long lunches with them with plenty of good wine so that the boat rights itself. I also flip a coin if I find myself procrastinating. A decision is a decision, it is off the desk and you can always revisit it, if the decision was crap. Celebrate. It's easy to get too much tunnel vision, to feel like you are always in the weeds. A walk outside to the local park, a few hours in a bowling alley or on a mini golf course can really change the atmosphere and help you see people in a different light - it lifts the darkness.

I have found women, generally, not to be very good at lunch, always late to arrive, leaving early and eating not very much. They can really learn a lesson from men who have generally thought they've had a very good day in business if they have a long lunch with a few glasses of something. They really know the marathon not a sprint phrase. Problems are natural in business but giving them plenty of time is also helpful. What do I mean by that? Buy time, say you will investigate and double any response time so instead of tomorrow say next week and usually the problem will have the heat taken out of it or solve itself in a way that you can accept. I did exec' management at Said Business School and was always fascinated by their classification of problems in three ways. Small, medium and large. Small - you can solve it. Medium, you need a third party to solve it and large, you probably will never solve it and nor will anyone else. Third parties or suppliers can create their own problems, but I find sticking to them generally a better method than the Goldman Sachs idea that you change

all your advisors every 5 years. Strength in family. Although I am not Goldman Sachs, nor never will be, so best not listen to me.

After twenty years in the trenches, one thing is clear: business is not for the faint-hearted. It’s a relentless cycle of wins and losses, highs and lows, breakthroughs and breakdowns. The mirage of success shifts constantly, and the reality is often far grittier than the polished surface suggests.

But if you’re still standing - if you’ve learned to take the punches, adapt to the chaos, and let go of what no longer works - then maybe, just maybe, it’s a battle worth fighting. Not for the money, the title, or the illusion of control, but for the challenge itself. For the sheer, maddening, exhilarating test of endurance. Because at the end of the day, the only real victory in business is the ability to keep going.

It’s a relentless cycle of survival, from forgetting friends and family birthdays to battling bills, fighting fires, and navigating the unbearable weight of responsibility. A key moment not to mention here, of course, was the Covid shut downthrowing a totally unreasonable set of extra problems at one's business. But, despite that and all my complaints, if you’re still in the game, you’ve already won the first battle: you’re still standing. And sometimes, that’s good enough.

THE LEGENDARY DIPLOMAT SURVEYS THE AFTERMATH OF CHANGES IN SYRIA AND HAS SOME ADVICE FOR PEOPLE STARTING OUT FOR ENTREPRENEURS TO KEEP AN OPEN DIALOGUE

Diplomacy is both an art and a science, requiring patience, pragmatism, and, above all, an unwavering commitment to peace. Nowhere is this more evident than in Syria - a conflict that has spanned more than a decade, reshaping the Middle East and challenging the very principles of international diplomacy. For young diplomats, Syria represents a sobering lesson in the complexities of global affairs, the limits of intervention, and the enduring necessity of dialogue. Many of the challenges we see in

Syria today stem from what I would call unfinished business. I recall my meetings in Damascus over a decade ago with President Assad, discussing the issues Syria faced and beginning the process of engaging with European and transatlantic colleagues on how to support the people’s demands for change. What followed, however, was fragmentation and disintegration. What started as calls for reform quickly descended into conflict, with factions emerging, dividing the country into battle zones. For young diplomats, one of the first lessons in dealing with

a crisis like Syria is the importance of understanding the situation before drawing conclusions. As I often tell those entering this field, take your time to observe, to listen, and to analyse before determining the best path forward. Syria is not an isolated crisis. It has significant implications for the broader Middle East. Its proximity to Lebanon, and the influence of Hezbollah, ties its stability to the interests of Iran and the wider region. The disruption of supply chains, the movement of armed groups, and the involvement of various external powers - from Russia

to Turkey - make Syria not just a local conflict but a geopolitical flashpoint. If you look at where key players stand, you see a shifting balance of power: Israel, Iran, Russia, and the United States all with vested interests, all calculating their moves. But what has been missing from many discussions is the role of Europe. Where does the European Union fit into this puzzle? What should be its approach, and how can it engage constructively in the future of Syria?

One of the stark realities of diplomacy is that crises do not remain contained. The ripple effects of a conflict like Syria extend far beyond its borders. The humanitarian crisis alone has forced millions into displacement, creating a refugee crisis that has affected neighbouring countries and beyond. Terrorism, economic instability, and moral responsibility all come into play. No country can afford to turn away from Syria without consequence. The notion that problems in distant regions can be ignored is a fantasy. Eventually, they will reach all of us in some form - whether through migration, security threats, or economic ramifications.

Another key aspect missing from many conversations is the role of multilateral systems. Where is the UN in all this? What influence does the Organisation for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE) have in shaping Europe’s policy on Syria? And what of NATO and other international coalitions? These institutions, built to uphold international order, must find ways to remain relevant. I often describe them as tankers at sealarge, slow-moving, covered in rust and barnacles, yet vital in carrying the ideals and values that underpin global stability. In contrast, we also have the smaller, more agile coalitions that can respond rapidly to crises but often lack longevity. Diplomacy needs both - the weight and experience of established institutions and the speed and flexibility of new alliances that can address emerging challenges. The world is changing, and with it, the

way we approach foreign policy must evolve. The war in Ukraine has already demonstrated how historical alliances are being reassessed. Countries that were once reliable partners may now choose to pursue their own interests differently. We can no longer assume that the coalitions that once supported Western ideals will continue to do so unchallenged. In Syria, and in broader Middle Eastern affairs, this shift is particularly evident. Nations are recalibrating their priorities, sometimes stepping away from traditional alignments, and this requires a fresh diplomatic approach - one that acknowledges these changes and seeks to build new, effective partnerships.

"SYRIA SHOULD SERVE AS BOTH A WARNING AND A CALL TO ACTION. IT IS A REMINDER OF WHAT HAPPENS WHEN DIPLOMACY FAILS, WHEN DIVISIONS ARE ALLOWED TO FESTER."

For young diplomats, Syria should serve as both a warning and a call to action. It is a reminder of what happens when diplomacy fails, when divisions are allowed to fester, and when human suffering becomes secondary to political manoeuvring. But it is also an opportunity - a chance for a new generation of diplomats to engage with greater urgency, deeper understanding, and an unwavering belief in diplomacy as the most powerful tool for change.

The challenge ahead is not just about resolving the immediate crisis in Syria but about preventing future conflicts of this nature. This requires investment in

Unsplash.com

diplomacy at every level, strengthening international institutions while also fostering new networks of cooperation. The task is not simple, and the timeline is long. Syria’s reconstruction, whenever it truly begins, will take generations. Trust, once broken, is not easily restored. Diplomacy is not about quick fixes but about sustained commitment. It requires perseverance, the ability to stand firm in the face of adversity, and an unwavering focus on the people whose lives depend on these efforts.

I urge those entering the field of diplomacy to see Syria not as a hopeless case but as a test of their resolve. The path to peace is always complex, but it is never impossible. Diplomacy remains the best hope for Syria and for the world. The question is whether we are willing to invest in it for the long term, knowing that the rewards may not come in months or years, but decades.

THE SUNNINGDALE HEADMASTER DISCUSSES HOW WE MIGHT RETHINK THE TYPICAL SCHOOL DAY TO BETTER PREPARE OUR CHILDREN FOR THE WORKPLACE

Educationis at a crossroads. In schools across the UK, we are faced with increasing demands, limited resources, and a system that seems to be constantly shifting direction. Yet, amidst these challenges, one thing remains clear: we need to reimagine the structure of the school day to better serve our students, teachers, and society as a whole.

One of the most pressing issues in education today is time - or rather, the lack of it. Our students have packed schedules, and yet we struggle to fit in everything they need, both academically and beyond. I have long been fascinated by the idea of extending the school day, an approach trialled in Wales with promising results. If state schools finished at 4pm instead of 3pm, and that extra hour was dedicated to sport, music, or other extracurricular activities, it could be transformative.

“AT MY SCHOOL, WE DEDICATE AN HOUR AND A HALF EACH DAY TO SPORT.”

At my school, we dedicate an hour and a half each day to sport. The benefits are tangible - better physical health, improved concentration, and higher levels of engagement in the classroom. Imagine if every student in the country had that opportunity. Not only would it give them access to activities they currently don’t have time for, but it would also support working parents, alleviating the pressure

of what to do with their children after 3pm.

Of course, any proposal to extend the school day raises a fundamental question: how do we pay for it? Schools are already struggling with funding, and additional hours would require more resources, staff, and infrastructure. The unions would undoubtedly have concerns, and the government would need to commit substantial investment. Yet, the longterm benefits - healthier, more engaged students, and a system that better accommodates modern family lifesurely make it an idea worth exploring. Contrast this with what is happening in some schools today. In my area, a

local comprehensive has had to cut its school day down to 1pm due to budget constraints. While there are after-school activities, they are no substitute for a full academic day. If we are serious about raising educational standards and supporting families, we should be moving in the opposite direction - not reducing school hours, but making them more meaningful and effective. Another challenge we face in education is recruitment. There is always a shortage of good teachers, particularly in certain subjects. Teaching is not an easy profession - it requires long hours, dedication, and a genuine passion for helping young people. Yet, for all its

challenges, it remains one of the most rewarding careers imaginable. A great teacher is not just someone who delivers a syllabus; they inspire, they ignite curiosity, and they equip students with the tools they need for life beyond school.

“TEACHING IS NOT AN EASY PROFESSION - IT REQUIRES LONG HOURS, DEDICATION, AND A GENUINE PASSION

We need to do more to encourage the next generation to consider teaching as a viable and attractive career path. This starts with improving teacher training, providing better support, and ensuring that schools are environments where talented educators want to stay. If we don’t address this soon, we risk losing some of our best teachers to burnout or disillusionment.

One of the things I value most about working in a small school is the flexibility it offers. Unlike in many larger institutions, we don’t rigidly separate students by year group. Instead, we use a ‘ladder system’ that allows boys to progress at their own pace, moving up as they develop individually. This approach fosters a more tailored education, ensuring that no child gets left behind.

Sadly, individuality is increasingly under threat in education. Schools, particularly in the state sector, face mounting regulations and standardised expectations that limit their ability to innovate. The system is bogged down by ever-changing policies, with each new education minister bringing a different set of priorities. What we lack is a long-term vision - a

coherent, well-researched strategy that isn’t abandoned every few years in favour of the next political trend.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of the education system is the lack of consultation with those who actually work in schools. There are brilliant people in education - teachers, heads, support staff - who deeply understand what students need, yet they are rarely given a voice in shaping policy. Instead, we see sweeping changes implemented from the top down, often without a clear understanding of how they will play out in practice.

“IT SHOULD BE A PLACE WHERE THEY DISCOVER THEIR PASSIONS, DEVELOP CHARACTER, AND GAIN THE SKILLS THEY NEED TO NAVIGATE LIFE BEYOND THE CLASSROOM.”

Rather than reacting to the latest fad, we need to step back and ask fundamental

questions: What does a great school day look like? What skills should students leave school with? How can we create an education system that nurtures curiosity, resilience, and independence, rather than just focusing on exam results?

At the heart of all this is a simple truth: education is about more than just academics. A school should not just be a place where students memorise facts and pass exams. It should be a place where they discover their passions, develop character, and gain the skills they need to navigate life beyond the classroom.

This is why I believe in finding a child’s ‘spark’ - that one thing that truly excites them. Whether it’s science, music, sport, or drama, school should be a place where every student gets the chance to explore their interests. That’s why I would love to see more opportunities embedded within the school day - gardening, sustainability projects, creative workshops - things that enrich a child’s experience beyond the core curriculum.

We may not have all the answers yet, but what’s clear is that the current model is not working as well as it could be. It’s time to be bold, to rethink the school day, and to ensure that our education system truly serves the needs of students, teachers, and families alike.

Let me start at the beginning. The book I have been writing did not begin as a plan, nor as a long-held ambition, but as a nudge from a good friend. When I was Secretary of State for Education, I met Neil Blair, an extraordinary literary agent whose reputation in publishing is legendary. His stable includes J.K. Rowling, and he was instrumental in shepherding her career from debut author to global phenomenon. Over coffee one day, he suggested I should write a book. “Get me a contract,” I quipped, and within weeks, he had.

HarperCollins won the bidding war, and Charlie Redmayne, its CEO, saw something in my story worth telling. But first, I had to get permission. As a sitting Secretary of State, I had to run the idea past the Cabinet Secretary, Simon Case. Initially hesitant - after all, politicians usually wait until they leave office to pen memoirs - he later agreed. “This is a remarkable story,” he said. “A Kurdish boy, arriving in Britain with no English, growing up to serve in government. It’s a testament to this country.” The only stipulation? No politics.

That’s how I found myself revisiting the past: the escape from Iraq, the cold pavements of my first British winter, and the long road to Downing Street. It became a book about resilience, the kindness of strangers, and the importance of education.

I was born into a country ruled by fear. My father, a businessman, refused to join the Ba’ath Party, Saddam Hussein’s nationalist political machine. That refusal cost us dearly. In Iraq, even innocent conversations at the breakfast table could be dangerous. At school, children were asked what their parents

had said over morning tea. A careless answer - mentioning discontent with the regime - could lead to disappearances.

So we fled. Arriving in the UK as a child, I had no idea what awaited me.

My first concern, like any eleven-yearold, was leaving my friends behind. The cold was shocking, the language alien, and I found myself sitting at the back of a classroom, unable to understand a word. Yet resilience is a funny thing. Children adapt. Within a year, I spoke fluent English. Within two, I was debating history with my teachers. Looking back, I see the fine margins between success and struggle. A childhood friend of mine was, by all measures, more talented than I wasbrilliant, charismatic. Yet, his life took a

darker turn, consumed by addiction. His story could have been mine. These are the moments that make you appreciate how easily life can shift in one direction or another. It reinforced my belief in the power of education and mentorship. We talk a lot about social mobility, but often, what it really comes down to is whether someone takes an interest in you at the right moment.

My father was a dreamer, a trait that both inspired and troubled him. He was the type of man who would wake up believing in an idea so passionately that he would bet everything on it. One such idea was a revolutionary cleaning product - an American invention that promised to clear drains without chemicals. He was convinced it was the

next big thing. He remortgaged our home, invested everything, and thendisaster. The product failed. The house was repossessed.

Yet, without his dreams, I wouldn’t be here today. His decision to leave Iraq, to take the risk of starting over in a foreign land, is why I stand in Britain today, privileged to have served my country. This is why I believe in entrepreneurs - because I saw firsthand that without risk-takers, the world stands still.

When I was young, I was drawn into the orbit of Jeffrey Archer. If he had not been a politician, he would have made an extraordinary football scout - he had an eye for talent and an instinct for leadership. His house in Lambeth became a hub for young, ambitious Conservatives. Among them were people who would go on to become cabinet ministers, including Priti Patel and Robert Halfon.

Archer himself was a complex character, deeply flawed but undeniably charismatic. Writing about him was tricky. I knew I had to be honest, and so, before publishing, I sat down with him. I wanted him to read what I had written. To his credit, he didn’t change a single word.

Boris Johnson was the politician who changed my career. While Theresa May

first appointed me to ministerial office, it was Boris who elevated me to cabinet. He saw something in me, and I will always be grateful for that.

“YOU’RE GOING TO BE MY BEAVERBROOK,” HE SAID. “YOUR COUNTRY NEEDS YOU.”

I remember the phone call vividly. It was a weekend, and my phone flashed with “No.10” on the screen. “Yes, boss,” I answered. “You’re going to be my Beaverbrook,” he said. “Your country needs you.”

He asked me to lead the vaccine rollout, a task of enormous pressure. The role came with a warning - friends texted me to say, “Do not take this job. It will destroy your career.” But for me, public service was never about selfpreservation. We were in the middle of a crisis, and I had seen first-hand how good Britain is at responding to challenge. What followed was one of the most intense periods of my life, working with extraordinary people, including Brigadier Phil Prosser, who ran military logistics for frontline operations. He

taught me the principle that “lateness costs lives,” a motto that drove us to deliver vaccines at a record pace.

Writing about my resignation from cabinet was painful but necessary. I wanted to set the record straight. Mistakes were made, but not in the way many assumed. The issue with my tax affairs arose from decisions made over 24 years ago regarding my company, YouGov. HMRC concluded that I should have structured my shareholding differently. I accepted their ruling, paid the fine, and moved on. But in politics, perception is everything. I should have been more explicit about the settlement from the outset.

“IF YOU DON’T TELL YOUR STORY,” HE SAID, “SOMEONE ELSE WILL TELL IT FOR YOU.”

Sir Brandon Lewis advised me to write about it. “If you don’t tell your story,” he said, “someone else will tell it for you.” So I wrote, not to rewrite history, but to present it truthfully.

If there is one lesson from this book, it is that there are no superhumans in life or politics. Whether it’s my father, my friend who lost his way, Jeffrey Archer, or Boris Johnson, they were all deeply human - capable of greatness but also of mistakes. And that’s what makes public life fascinating. We shouldn’t demand perfection from those who serve; we should demand integrity, resilience, and a willingness to learn.

As I put the final words on the page, I reflect on one thing above all: I am grateful. For this country, for its opportunities, for the people who believed in me when it mattered most. And for the chance to tell my story, in the hope that others might find in it something of their own.

I spent nearly two decades in real estate, working with some of the biggest names in property development, but my transition into the world of e-scooter racing has been one of the most exciting shifts in my journey.

I started my career working with British Land, Aviva, and Royal Mail before joining Blackstone. It was an intense and challenging time, but after a few years, I felt the pull toward entrepreneurship.

I wanted to create an accessible way for people to rent in London, especially those who struggled with affordability. That’s what led me into co-living - micro-apartments designed with financial accessibility in mind.

Despite the challenges - planning, politics, and everything in between - I persisted. I built a company managing 500 units, but ultimately, my cofounder and I parted ways. It was a tough learning curve, but I took the lessons and kept moving forward.

Balance Out Living was my next venture, built on the pillars of wellness, sustainability, and community. I had worked myself to the bone and felt completely imbalanced. I wanted to create spaces where people could live their best lives - physically, financially, and socially.

We had backing from Oaktree Capital, but by the end of 2022, they changed their fund strategy and pulled their investment. Suddenly, I was at a crossroads.

I cycle to work regularly, and I started to explore electric vehicles as an alternative. That’s when I came across e-scooter racing on Instagram. It was

fast, exciting, and - most importantly - gender inclusive. I saw a woman standing on the podium, competing against men, and thought: this is something different.

“I CAME ACROSS E-SCOOTER RACING ON INSTAGRAM. IT WAS FAST, EXCITING, AND - MOST IMPORTANTLY - GENDER INCLUSIVE.”

I went down a rabbit hole, researching the sport, and eventually connected with the founders - veterans from Formula E, Le Mans, and Formula One. At first, they thought I was just interested in sponsorship. But I told them, no, I want to own a team.

By December 2023, my team, XPRS Racing, took the starting line in Dubai, competing against teams from the UK, US, Middle East, India, and the Far East. One of the other UK teams was owned by Anthony Joshua. I was in great company.

XPRS Racing is built on inclusivity, integrity, and authenticity. It’s not just about winning races; it’s about building a movement.

E-scooter racing is still in its early

days, but it’s gaining traction fast. We were meant to race in 2024, but geopolitical tensions put events on hold. Now, we’re looking to scale up in 2025.

I want to establish a UK Championship, with grassroots events around the country leading to a major final in London. I’m in talks with venues like King’s Cross, the ExCeL Arena, and even sites near Buckingham Palace. This needs to be a sport for everyone, from commuters to professional athletes.

At the elite level, our scooters hit speeds of 140 km/h. These aren’t just rental scooters - they’re highperformance machines. But we’re also creating an entry-level category for new riders, racing at 80-90 km/h, so there’s a clear progression path.

There’s a stigma around e-scooters. People associate them with street crime, reckless behaviour, and poor infrastructure. That’s why regulation is so important. The federation is working with governments to implement safe policies for city use.

Paris banned rental e-scooters because they weren’t properly managed. But if done right, micro-mobility can be a game-changer for urban transport. We need better infrastructure and clear rules.

As a team owner, I generate revenue through sponsorships, prize money, and merchandising. We narrowly missed the podium in Dubai, but we were competitive. Sponsorship is a big focus moving forward. We’re already in discussions with major brands.

Some of my fellow team owners are social media influencers, but for me, this isn’t a side project - it’s a serious business and a long-term passion.

I’m also speaking with a former Team GB rugby player and other influential athletes who align with our values. This isn’t just about racing - it’s about changing the narrative around

inclusivity and sustainability in sports. Could e-scooter racing be an Olympic sport one day? Probably not. The Olympics favor non-powered sports. But freestyle kick scootering is being lobbied for inclusion, which is promising.

“MY REAL VISION IS TO MAKE E-SCOOTER RACING A MAINSTREAM PHENOMENON.”

My real vision is to make e-scooter racing a mainstream phenomenon. Formula E started as an experiment and is now a major motorsport. We’re at that same starting line.

I come from a working-class immigrant family. My parents sacrificed a lot to give me opportunities, and now I want to create something that opens doors for others.

That belief extends to my team. My riders aren’t just competitors; they’re role models. They show young people that they can break into this sport, regardless of their background.

As I reflect on my journey, I know this is just the beginning. If we can build a sport that is fast, exciting, inclusive, and sustainable - why wouldn’t we?

From real estate to e-scooter racing, I’ve always tried to stay ahead of the curve. And as XPRS Racing gears up for its next challenge, I’m not slowing down anytime soon.

Ten Thousand Hours

Inever set out to be a financial adviser. As a teenager, I had no grand vision of guiding people toward financial security. If anything, I entertained the usual childhood ambitions - actor, teacher, police officer, even surgeon. But life has a way of shaping us, often through hardship, and my journey into financial planning was no exception.

I was just nine years old when my father passed away from cancer. He was a successful restaurateur, part of the renowned Forte family, and ran a hotel and two restaurants in Westonsuper-Mare. But despite his success, my family was left in financial ruin when he died - no life insurance, no will, no financial planning. My mother was made bankrupt, and from that moment, financial insecurity was woven into the fabric of my life.

At 13, I was helping my aunt run the family business, trying to keep things afloat. Those early years instilled a work ethic in me that never left. I went to university, still unsure of my path, but upon graduation, the realities of needing to pay off my student overdraft led me to take a temporary admin role at an IFA firm. That was when everything clicked.

I quickly realized that my family’s financial struggles were not unique. There were countless others like my father - hardworking, successful

even, but wholly unprepared for life’s uncertainties. The financial world, at the time, was transactional. The focus was on commissions, on selling products rather than providing advice that truly mattered. That didn’t sit right with me.

After four years of working under someone whose approach to financial planning was purely sales-driven, I took a leap of faith. It was a terrifying year - getting married, buying a house I couldn’t afford, and welcoming twins into the world - all while walking away from the security of employment to

start my own business. I set up shop in a converted garage next to my house with a radical idea: financial planning should be about long-term relationships, service, and integrity, not transactions.

It was an uphill battle. A 25-year-old preaching about customer service and holistic planning in an industry built on commissions and quick sales was met with skepticism. But I stuck to my principles. I introduced a guaranteed service charter - something unheard of at the time. Slowly, people started to listen. Thirty years on, the industry

has changed, and while I won’t claim to be a thought leader, I take pride in knowing I was ahead of the curve.

One of the most pivotal moments in my career came two years after starting my firm. I finally convinced my stepfather - my mother had remarried - to become a client. It took courage. No one likes the thought of rejection, especially from family. But he agreed, and in December 1991, we set up his financial plan. Two months later, he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of stomach cancer. Within four weeks, he was gone.

It was a devastating blow, but it reinforced my purpose. I had seen firsthand what happened to families left unprepared. My mother had lost everything after my father’s death. Now, here I was, watching history repeat itself. That solidified my passion: ensuring that no family suffered the way mine had.

“62% OF

People don’t like to think about their own mortality. It’s why 62% of the UK population doesn’t have a will. We delay, believing we have time. But financial planning isn’t just about preparing for death; it’s about making life better now. It’s about security, education, choices. I help clients set up trust funds for their grandchildren because I know what it’s like to have no lasting legacy. I ensure people understand their finances so they can enjoy their lives, not just scrape by.

The lack of financial education in schools is something that deeply frustrates me. We teach algebra, but not how to manage debt. We expect

young people to sign up for mortgages and pensions without understanding interest rates or inflation. When I left university, no one had ever explained the difference between a repayment and an interest-only mortgage to me - I had to figure it out myself. That’s unacceptable.

Financial illiteracy isn’t just an inconvenience; it has real consequences. I meet clients who proudly tell me they’re earning 2% interest on their savings while holding debts that cost them 7%. They don’t realize that simply reallocating their funds could transform their financial future. People rush into investments - buy-to-let properties, stocks - without understanding the risks, drawn in by hype and emotion rather than logic. And then, when things go wrong, they find themselves in financial distress, forced to rely on family or the state for support. It doesn’t have to be this way.

The truth is, good financial planning isn’t about picking the right stocks or chasing the highest returns. It’s about adaptability. Life changes - marriages, divorces, new jobs, redundancy, illness. What works today may not work tomorrow. I operate on what I call the “1-100 Rule” - in one year, your financial situation will be 100% different than it is today. That’s why ongoing advice matters. It’s not enough to set up an investment or a pension and forget about it. Plans need to evolve.

I recently dealt with a client whose investment, sold to them by a major bank in 2011, had dwindled to just 25% of its original value. No one had checked in. No one had advised adjustments based on inflation, market shifts, or their changing needs. They now face running out of money within four years. This isn’t an isolated caseit’s a systemic failure of transactional financial services.

That’s why I advocate for continuous, proactive financial planning. A simple concept like the “safe withdrawal limit” can make all the difference. If a client sells their business and needs to turn capital into income, we work on a sustainable 4% withdrawal rate - enough to maintain their lifestyle without depleting their savings. Factoring in inflation, market performance, and long-term sustainability is crucial. Yet, so many people don’t receive this kind of structured guidance, and they suffer for it.

“IT’S NOT ENOUGH TO SET UP AN INVESTMENT OR

A PENSION AND FORGET ABOUT IT. PLANS NEED TO EVOLVE.”

I’m on a mission. Not just to advise my clients, but to change the way people think about money. To educate, to empower, to ensure that no one experiences the financial hardship my family did. Financial security isn’t about being wealthy - it’s about having control, peace of mind, and the ability to enjoy life without constant worry.

So, no, I didn’t wake up at 13 dreaming of being a financial adviser. But I did wake up to the reality that financial planning changes lives. And that’s what drives me every day.

In the context of today’s everevolving and dynamic business landscape, inclusive leadership has never been more important. At its core, inclusive leadership isn’t just about avoiding discrimination or bias (although that’s clearly essential), it’s also a mindset that prioritises authenticity, empowerment, and innovation. Inclusive leadership goes beyond isolated initiatives; it concerns every moment a leader makes a decision or interacts with others. Business leaders increasingly recognise that this approach isn’t just better for your employees - it’s critical for building resilient, high-performing businesses.

Fostering inclusive leadership promotes diversity and produces tangible business results. Zheng et al. (2023) found that teams led by inclusive leaders are 17% more likely to report high performance, 20% more likely to make high-quality decisions, and 29% more likely to collaborate effectively. These numbers speak for themselves.

Inclusion is a priority for the next generation of employees. Gen Z is the most diverse generation in the workforce, and they are demanding greater diversity and inclusion in the workplace. In fact, more than half of Gen Z employees would not accept a job without diverse leadership and for good reason. Inclusive teams make better decisions 87% of the time and are up to 36% more likely to have above-average profitability. Gen Z reject top-down decision-making, instead welcoming diverse approaches and ways of thinking. They look for leadership approaches that value all opinions.

This raises an important question: if the evidence that inclusive leadership attracts top talent and drives better business results is so strong, how can we develop more inclusive leaders?

As Dean of ESCP Business School in London, the challenge for me is clear - to create environments where our students not only learn about inclusive leadership but also practice it in ways that prepare them for the realities of the modern business world. Every year, ESCP welcomes 11,000+ students from 136 different nationalities. A diverse international community is an essential part of our education. By embedding diversity and inclusivity into our curriculum and ways of learning, we actively empower the next generation