NARENDRA MODI

THE INDIAN CENTURY

UK’S NUMBER ONE

DESTINATION

FOR LUXURY WATCHES & JEWELLERY

Proud supporters of The King’s Trust

Editor:

Christopher Jackson

Editor-at-large: Claire Coe

Contributing Editors:

Emily Prescott, Meredith Taylor, Lord Ranger, Liz Brewer, Dr Paul Hokemeyer

Advisory Board:

Sir John Griffin (Chairman), Dame Mary Richardson, Sir Anthony Seldon, Elizabeth Diaferia, Ty Goddard, Neil Carmichael

Management: Ronel Lehmann (Founder & CEO), Colin Hudson, Tom Pauk, Professor Robert Campbell Christopher Jackson, Curtis Ross, Julia Carrick OBE, Gaynor Goodliffe

Mentors:

Derek Walker, Andrew Inman, Chloë Garland, Alejandra Arteta, Angelina Giovani, Christopher Clark, Robin Rose, Sophia Petrides, Dana JamesEdwards, Iain Smith, Jeremy Cordrey, Martin Israel, Iandra Tchoudnowsky, Tim Levy, Peter Ibbetson, Claire Orlic, Judith Cocking, Sandra Hermitage, Claire Ashley, Dr Richard Davis, Sir David Lidington, Coco Stevenson, Talan Skeels-Piggins, Edward Short, David Hogan, Susan Hunt, Divyesh Kamdar, Julia Glenn, Neil Lancaster, Dr David Moffat, Jonathan Lander, Kirsty Bell, Simon Bell, Paul Brannigan, Kate King, Paul Aplin, Professor Andrew Eder, Derek Bell, Graham Turner, Matthew Thompson, Douglas Pryde, Pervin Shaikh, Adam Mitcheson, Ross Power, Caroline Roberts, Sue Harkness, Andy Tait, Mike Donoghue, Tony Mallin, Patrick Chapman, Amanda Brown, Tom Pauk, Daniel Barres, Patrick Chapman, Merrill Powell, Kate Glick, Lord Mott, Dr Susan Doering, Raghav Parkash, Marcus Day, Sheridan Mangal, Mark Thistlethwaite, Madhu Palmar, Margaret Stephens, John Cottrell, Victoria Anstey, Stephen Goldman, Patrick Timms, James Meek, Dominique Rollo, Tracey Jones, Alan Urmston, Duncan Palmer, James Slater, Charles Hamilton-Stubber, Catherine Wood, Guy Beresford

Business Development: Rara Plumptre, Khalid Dadoush

Design and Digital: Nick Pelekanos, Ankita Agrawal, D’Arcy Lawson Baker

Photography: Sam Pearce, Will Purcell, Gemma Levine

Public Relations: Pedroza Communications

Website Development: Eprefix

Media Buying: Virtual Campaign Management

Print Production: Marcus Dobbs

Printers:

Micropress Printers Ltd

Distribution: Emblem Group

Registered Address:

Finito Education Limited, 14th floor, 33 Cavendish Square, London W1G 0PW, +44 (0)20 3780 7700 Finito and FinitoWorld are trade marks of the owner. We cannot accept responsibility for unsolicited submissions, manuscripts and photographs. All prices and details are correct at time of going to press, but subject to change. We take no responsibility for omissions or errors. Reproduction in whole or in part without the publisher’s written permission is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. Registered in England No. 9985173

FOUNDER’S LETTER

Eighteen months ago, I was a guest for lunch at The Garrick Club. Although I am not a member of any club, I have been fortunate to be invited to a fair few over the years. This visit was more unusual, as from the moment I entered the main entrance, I was immediately whisked up the grand staircase by a sommelier who waxed lyrical about my host’s choice of vintage red wine from the cellar. You can imagine my growing excitement not to have a chance to ask whether he had tasted the wine before decanting, before being warmly greeted by Martin Landau holding forth in the Bar. Lunch was a banquet, and I was impressed by the 1982 Chateau Margaux. He was so interested in what Finito is doing, and I had to pace myself as the waiter took pride in topping up my glass.

It turned out to be a farewell encounter and one which I will never forget. I must have been away when the sad news of Martin’s passing reached me. We pay tribute to a giant of property and someone who did so much to give back to those less fortunate during his lifetime. In previous issues, we have championed bursary pupils from the Landau Forte College Derby, as they transition to the world of work. Those students will always remember his name. Hospice UK has been warning for some time about the challenges facing the community of more than 200 hospices it represents. The charity has warned of the worst financial year on record - and has been actively lobbying the new government. Hospices are set to take another hit when Employers

National Insurance goes up April, with no exemption offered by the Treasury. Just before Christmas, the government recognised the urgency of the situation, announcing £100m of capital funding for hospices in England. But the underlying position remains fragile, and Hospice UK is now looking to the government's NHS ten year plan to provide some long term security for these vital organisations.

With the highest predicated GDP growth of any major nation in 2023, India’s status as a global superpower is rising exponentially. In 2022 the country overtook the UK as the world’s fifth-largest economy. In 2023 its population overtook China’s. Since the dawn of the 21st century, global political and business leaders such as Amazon’s Jeff Bezos have identified this as India’s Century, just as Great Britain dominated the 19th century and the United States the 20th.

Narendra Modi is serving his third term as Prime Minister of India and recently stated that he has no reasons to worry that India-US relations would not prosper under Trump.

The advent of a UK-India trade deal could provide over 300,000 new jobs in this country and over a million in India. It takes courage from international business leaders with demonstrable record of achievement to get this over the line. One such man is Dinesh Dhamija, who has worked tirelessly to promote the benefits to our two nations. As a mark of our respect, we have titled this issue after his book which he authored which makes for compelling reading. If our politicians cannot get the trade deal done, I say “send for Dinesh.” His business leadership, resilience and diplomacy skills would ensure that a deal is finally reached.

If you have an idea for a front cover feature or other article, we would like to hear from you. A New Year toast to you all and absent friends.

ACCESSORIES BATHROOMS BEDS

CARPETS, RUGS & FLOORING

CURTAINS, POLES & FINIALS

FABRICS FURNITURE HARDWARE

KITCHENS LIGHTING

OUTDOOR FABRICS

OUTDOOR FURNITURE PAINT

TILES TRIMMINGS & LEATHER

WALLCOVERINGS

ABI INTERIORS ALEXANDER LAMONT + MILES ALTFIELD

ALTON-BROOKE AND OBJECTS ANDREW MARTIN

ARTE ARTERIORS ARTISANS OF DEVIZES AUGUST & CO

BAKER LIFESTYLE BELLA FIGURA BRUNSCHWIG & FILS

C & C MILANO CASAMANCE CECCOTTI COLLEZIONI CHASE

ERWIN CHRISTIAN LEE (FABRICUT) CHRISTOPHER HYDE

LIGHTING COLE & SON COLEFAX AND FOWLER COLLIER WEBB

COLONY BY CASA LUIZA CRUCIAL TRADING DAVID HUNT

LIGHTING DAVID SEYFRIED LTD DE LE CUONA DEDAR DONGHIA AT GP & J BAKER ECCOTRADING DESIGN

LONDON EDELMAN EGGERSMANN DESIGN ELITIS ESPRESSO

DESIGN FLEXFORM FORBES & LOMAX FOX LINTON FRATO

GALLOTTI&RADICE GEORGE SPENCER DESIGNS GLADEE

LIGHTING GP & J BAKER HAMILTON LITESTAT HARLEQUIN

HECTOR FINCH HOLLAND & SHERRY HOULÈS HOUSE OF ROHL

HUMA KITCHENS IKSEL DECORATIVE ARTS INTERDESIGN UK

JACARANDA CARPETS & RUGS JAIPUR RUGS JASON D’SOUZA

JEAN MONRO JENNIFER MANNERS DESIGN JENSEN BEDS JULIAN

CHICHESTER KINGCOME KRAVET KVADRAT LASKASAS LEE JOFA

LELIÈVRE PARIS LEWIS & WOOD LINCRUSTA LIZZO LONDON

BASIN COMPANY LONDONART WALLPAPER LOOM FURNITURE

MARVIC TEXTILES MCKINNON AND HARRIS MINDTHEGAP MODERN BRITISH KITCHENS MORRIS & CO MULBERRY HOME THE NANZ COMPANY NOBILIS OFICINA INGLESA FURNITURE

ORIGINAL BTC OSBORNE & LITTLE PAOLO MOSCHINO LTD

PAVONI PERENNIALS SUTHERLAND STUDIO PHILIPPE HUREL

PHILLIP JEFFRIES PIERRE FREY PORADA PORTA ROMANA QUOTE & CURATE RALPH LAUREN HOME RESTED ROBERT LANGFORD

ROMO RUBELLI THE RUG COMPANY SA BAXTER ARCHITECTURAL HARDWARE SACCO CARPET SAMUEL & SONS SAMUEL HEATH

SANDERSON SAVOIR BEDS SCHUMACHER SHEPEL’ SIMPSONS THE SPECIFIED STARK CARPET STUDIO FRANCHI STUDIOTEX SUMMIT FURNITURE THG PARIS THREADS AT GP & J BAKER TIGERMOTH LIGHTING TIM PAGE CARPETS TISSUS D’HÉLÈNE TOLLGARD

TOM RAFFIELD TOPFLOOR BY ESTI TUFENKIAN ARTISAN CARPETS TURNELL & GIGON TURNSTYLE DESIGNS TURRI VAUGHAN VIA ARKADIA (TILES) VISPRING VISUAL COMFORT & CO. WATTS 1874 WENDY MORRISON WEST ONE BATHROOMS WIRED CUSTOM LIGHTING WOOL CLASSICS ZIMMER + ROHDE ZOFFANY ZUBER

Product shown sourced from Design Centre, Chelsea Harbour. See www.dcch.co.uk/advertising-credits

THE HOME OF THE WORLD’S GREATEST DESIGN AND DECORATION BRANDS

THE ULTIMATE PRODUCT RESOURCE

ENGAGE WITH EXPERTS IN THE SHOWROOMS

DISCOVER WORLD-CLASS DESIGN

130+ SHOWROOMS OVER 600 INTERNATIONAL BRANDS ONE ADDRESS

Design Centre

Chelsea Harbour

London SW10 0XE

www.dcch.co.uk

A NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION

This isn’t a magazine dedicated to philosophy, but as 2025 kicks into gear there is no harm in considering the work of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). Swedenborg’s work continues to attract a small but dedicated following across the globe. The Swedish philosopher’s contemporaries knew him as a scientist, who made remarkable early predictions of the double helix structure of the gene, and described the function of the neuron well before his time. He also produced early prototypes of a flying machine and a submarine – among many other things.

But he is known now most of all for his theological work, especially Heaven and Hell (1758) which provides a description of what he calls a Heaven of Use. In short he states that everything - and therefore everybody – has been created for a reason. Our goal as human beings, it might be said, is to discover what another philosopher Wilson Van Dusen called ‘the gentle root of one’s existence.’

This is a very interesting question to ask oneself in respect of our careers, and in respect of our lives. What am I really created to do? To the frustration of many career-seekers, this can often be easier to discover in others than in oneself. This in turn is part of the power of mentorship: to shine a light on us which we can’t quite angle rightly towards ourselves.

Usually when somebody is discussing what they love, their voice becomes tender, and their expression changes. We all know the music-lover is different when they discuss music; the film-lover will gesticulate passionately when the Oscar nominations are talked about; and the born entrepreneur will be unusually animated when the conversation comes round to Elon Musk.

Yet despite the fact that the signals can often be reasonably clear, there are a remarkable number of people out there who don’t follow their passion. Sometimes this can be a question of sincerity: they never went inwards sufficiently really to ask themselves what usefulness might mean in their case.

In other instances, people are aware of what they love but the notion of doing it for a living seems almost too good to be true. They don’t pursue it out of some strange inner tendency to stymie themselves.

It is for this reason that Baroness Nicky Morgan when she was Education Secretary during the Cameron administration placed such emphasis on resilience. Sometimes, we can be strangely circumspect about what we love, and part of education should be to toughen ourselves mentally against the naysayers within as well those without.

And yet the real point of Swedenborg’s theory of use is that it needn’t always be glamorous. There is pleasure to be had in fulfilling a humble function. In fact banal tasks can be a good place to start in terms of performing use: clearing our work space, going through our emails, being sure to respond in timely and thorough fashion.

This might be why Morgan at a recent Finito event emphasised the importance of curiosity when it comes to our roles. How much better would the world have been had, say, Justin Welby performed his tasks with more thoroughness? How much better would it have been had Paula Vennells investigated with a real sense of her use what came across her desk?

It is a small point in the scheme of things but in each instance it would have been better not just for the victims but for Welby and Vennells too. We have all had to face up to the reality that

the Archbishop of Canterbury felt the appearance of his function was more important than the function itself.

Of course, all this works too at the political level. Democratic elections bequeath mandates and it is wise to see these as permission to conduct use. Too often hyperactive politicians go outside their mandate; when they do so it might be said they are breaching the laws of use.

We have seen in the past few months two clear examples of this. I can’t remember Donald Trump mentioning the potential American acquisition of Greenland with much volubility on the 2024 campaign trail. It took the presidential transition for that topic to come up.

Similarly, the Starmer administration is equally culpable when it comes to tax. Here again, the sudden post-election discovery of a so-called ‘black hole’ in the public finances led to large National Insurance rises on employers. Again, all this materialised as a prospect after and not before the election. This will mean that as the cost of borrowing escalates, and fiscal rules are inevitably broken, the electorate will be less likely to give the Chancellor Rachel Reeves the benefit of the doubt. She has violated the doctrine of uses.

The truth can sometimes be better, though often a bit more prosaic, than human beings tend to make it. Many human beings are very resourceful and smart: most likely the job in front of you at the moment is one you can do very well – and better than you could imagine if you were to give it your full respect and attention. But human beings also dream outside their scope – and insodoing limit their effectiveness.

To be quietly useful is therefore as good a New Year’s Resolution as any. Besides, not to be useful can come back to you quicker than you may imagine, as Reeves and Trump may well discover.

AGAINST IMMOBILITY

It’s quite difficult running businesses. It goes without saying that you have to sell a lot of whatever you’re selling, while also meeting tax requirements, keeping and ideally expanding your workforce, and creating a desirable workplace culture.

As the huge number of bankruptcies each year attest (around 2,000 per month in 2024), a lot has to fall into place for that to happen in the best of times. And these past years have, to put it charitably, not been the best of times. From Brexit to Covid to inflation and beyond, stuff keeps happening.

So spare a thought for those who try to do all the difficult things above – and also to do it with a

social conscience, and make sure they employ people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Finito World recently heard of a top recruitment firm in London which has always had a bursary scheme in place for recruiting people from impoverished backgrounds. It was part of the ethos of senior management to want to do this.

Now that Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner has mooted the notion of unfair dismissal on day one the scheme has had to be curtailed. The firm can’t take the risk of litigation which would undoubtedly ensue should they have to let people go . “It could be a week of poor performance and then a no-win no-fee lawyer. We

can’t commit to that,” the chairman told us.

Such are the unintended consequences of what is surely well-meaning legislation designed to promote the rights of employees.

At the heart of the issue is the question of trust. Can businesses be trusted to make genuine efforts off their own bat to tackle social mobility? The answer will be yes or no on a case by case business. But the suspicion remains that a bit of freedom can go a long way – and its curtailing usually means litigation. That will create, as night follows day, a society of lawyers. Sir Keir Starmer of all people might be expected to know that – he used to be one after all.

IN DEFENCE OF MOHAMED AMERSI

The other day we spoke to an employee of the philanthropist Mohamed Amersi. “Every day he does incredible things nobody hears about.” This magazine can attest from its long friendship with Amersi that this is true.

Amersi’s list of philanthropic endeavours is indeed extraordinary, and are detailed in his autobiography Why? which we review in our books pages in this edition.

But to read the mainstream media you’d not know that, since Amersi has for years now been regularly ambushed by Charlotte Leslie, Tom Burgis, David Davis and Margaret Hodge. He has had to watch himself be turned into a

caricature, though he hasn’t let up one bit in his hard work for the causes he believes in.

But is the tide beginning to turn? What makes Why? such an extraordinary read is Amersi’s absolute refusal to be polite. This puts him in breach of an unwritten rule of the British Establishment – and especially of the Conservative British establishment. It also makes the book stand out from all the careful and selfserving memoirs one ordinarily reads.

Here is a man who refuses to mince his words, and it’s refreshing. Amersi in fact comes across as a sort of quirky Hercules clearing the Augean stables. Insodoing he also shows the raw emotion which actually surrounds

power, and which is always simmering beneath the surface at Westminster. It couldn’t be more different from the genteel Etonian calibrations of those who until recently held the reins of power.

Kemi Badenoch could do a lot worse than read Amersi’s book: it shows a man who dearly wanted to do good, but who wasn’t prepared to put up with the nonsense that nowadays pervades the Establishment. It is immensely to his credit that instead of pretending it was all okay, as everybody else does, Amersi calls it what it was: a complete mess that needs to be fixed.

THIS ISSUE

p20 Fatima Whitbread MBE p36 Sir Michael Morpurgo

p114 Selena Gomez

Jimmy Choo

JON SOPEL

THE

LEGENDARY BROADCASTER ON JANUARY 6TH 2021, THE STARMER ADMINISTRATION – AND WHY HE LEFT THE BBC

Iam sometimes asked about why I left the BBC. I remember the corporation went through this spasm of asking themselves how to attract the young. The editor of the 6 O’Clock News was thinking about how we get more young people. Do we need younger presenters? Or do we need old people like me talking about young people’s issues? This was at a time when LPs were making a comeback. We sent a young reporter down to Oxford Street, and said to a teenager, holding up an LP: “Hello, I’m from the Six O’Clock News. Do you know what this is?” The teenager replied: “Yes, it’s an LP. What’s the Six O’Clock News?”

Thinking back to January 2021, I can’t forget the day after the inauguration when Joe Biden was finally President. Washington DC was a garrison town, the place was absolutely sealed off. There were rolls and rolls of barbed wire because of

what had happened on January 6th. I will never forget the shock of that.

January 6th is also inscribed on my mind. I’ve been in situations where I’ve faced greater personal danger, but I’ve never seen a day more shocking than January 6th when the peaceful transfer of power hadn’t happened. The Capitol had been sealed off by razor wire and I went as close as I could, and went live on the 6 O’Clock News. There were lots of Trump supporters around and they heckled me throughout. It soon morphed into a chant: “You lost, go home! You lost, go home!” I was trying to figure out what that meant. At the end of my live broadcast I said to this guy: “What on earth does this mean?" He poked me in the chest and said: “1776.” I thought: 'Do I explain that my family was in a Polish shtetl at that stage?"

Jon Sopel (Wikipedia.org)

“THEN YOU’D GET PESKY PEOPLE LIKE TONY BLAIR WHO COME ALONG AND REMIND THEM IT IS ABOUT POWER. ”

It’s always seemed to me that the Labour Party finds power a really inconvenient thing to happen. They much prefer it when they're forming Shadow Cabinets and discussing the National Executive. Then you’d get pesky people like Tony Blair who come along and remind them it is about power. The Conservative Party was always the ruthless machine of

government: there is an element in which the Conservative Party is in danger of going down the Labour Party route. It was the Conservative Party membership, for instance, who gave us Liz Truss, the patron saint of our podcast The News Agents. We launched in the week she became Prime Minister - and my God, she was good for business.

What would Britain look like if there were 10 years of Starmer? He’s done the doom and gloom, and how everything is the Conservatives’ fault. That's fine - but so far, he’s not set out what the future is going to look like under him. Is it Rachel Reeves’ vision of the growth economy? Or is it Rayner’s vision of increasing workers’ rights. I think Starmer is an incrementalist and simply doesn’t know. If he has any sense at all he will look at the centre of political gravity in the electorate and go for growth because that’s what the country needs.

Jon Sopel was talking at a Finito event given in aid of Hospice UK. To donate, go to this link: https://www.hospiceuk.org/support-us/donate

Meet the Mentor: SHERIDAN MANGAL

FINITO WORLD MEETS SHERIDAN MANGAL, A MENTOR WITH A PARTICULAR LINE IN CAREER CHANGE MENTORING

Can you talk a bit about your upbringing and early career choices and how they shaped your work as a mentor for Finito?

Born in 1961, I am what many would refer to as a baby-boomer, but also first UK-born from the ‘Windrush’ generation. Raised in East London, progressing through primary and secondary school was a bumpy ride, but was equally the origin of my developing interests and ambitions. Once I realised that being a striker for Chelsea FC required some football talent, I turned my attention elsewhere…the City.

So how did you make your way in your chosen field?

After doing well at Brooke House Secondary, the intent of a temporary summer job prior to sixth form education turned into a permanent career decision. A City opportunity arose and at 16 years wrapped in sharp suit, my 16 year career at the London Stock Exchange began. This presented many challenges regarding steep learning curves, but also the unpleasant social ills of the time that crept into the workplace. After some years and despite the work experience gained, it is here that I always felt few steps behind those entering via the graduate intake.

Notwithstanding the lack of confidence, I pressed on, supported by great parents. Effectively, they were my first mentors. As my career progressed, the challenges persisted, but maturity, experience and simultaneous education

enabled a response mechanism and positioned me as source of advice for others following.

This triggered my interest in mentoring. After many years of alliances with youth charities, schools and colleges, often deploying self-designed initiatives, my interest has never waned. Hence, my involvement with Finito, where I can draw on many personal and professional experiences that equate with entry-level candidates as they build and apply their career plans.

Did you have a mentor growing up or early on in your working life?

Apart from parental guidance, I had no mentor as such. Indeed the concept of mentorship was unfamiliar and unrefined compared to today. I often say my professional navigation of financial markets through the 70s, 80s and 90s was predominantly by combat rather than design: responding to ad-hoc opportunities as opposed to proactively seeking the next logical step.

Against this backdrop. I can certainly appreciate the benefits of guidance from someone who has already travelled my journey. It would have saved some considerable pain, particularly at the junctures of indecision and plain fear. The anxiety was debilitating. Hence, I am here today with Finito, offering my stories and knowledge that I trust can be useful to those who are apprehensive, lacking direction or facing obstacles that appear insurmountable.

You’ve worked for a long time in the financial and hedge fund sectors. What is it you think that mentees ought most to know about those sectors?

Understanding the dynamics of the securities industry is crucial. Heavily regulated and often driven on market sentiment, the financial markets space is broad and deep, with a variety of instruments and strategies for those of low to high risk appetites.

As an entrant, my advice would be to know the target sector’s current and emerging states and trends. This includes the leaders and their respective strengths, the established and rising boutiques and the general issues the chosen sector is facing.

This is particularly so with asset management. The adoption of AI and algorithmic strategies is pervasive as is the growth in passive investing. Regarding employment, candidates must be aligned with entry

Sheridan Mangal

programmes including ‘off-cycle’ routes.

Mentees should also ensure applications focus on value offered at the earliest opportunity, from the perspective of the employer. Furthermore, the objective shouldn’t be for a particular role, but to just get into the industry or sector and navigate to where your developing strengths are needed.

It’s astonishing to see your passion for the law come through on your CV. What is it that drives your passion for the law and your desire to keep on learning?

Further to my active interest in financial markets, I have always held a curiosity for the legal implications and general application of the law.

Quite late in my career, I decided to take this further and embark on my legal qualifications while working, culminating in my bar exams during Covid. There were several drivers; my increasing interest in commercial law, unpicking an issue with legal reasoning and the gravitas of becoming a lawyer. More importantly, proving to myself that I could actually do it was the strongest motivation.

The distillation of a problem into a legal case, concurs with my pattern of detailed thinking regarding outcomes, the inherent dependencies and viable strategies. Indeed I am always curious about a variety of subjects, incidents and histories, some exciting and astonishing, many quite dull, but revealing.

Nonetheless, I have a constant thirst for learning, teaching and testing myself, albeit through new formidable social and business challenges ….or simply the latest FT cryptic crossword while on the 0659 from Eastbourne to Victoria.

You’ve been doing a lot of mentoring for Finito. What’s the most common mistake you’re seeing when it comes to young people when they choose their career paths and start out on their career journeys?

I have been mentoring for over 20 years, recently with Finito. Socially, I remain active volunteering within the context of addressing youths within or vulnerable to negative lifestyles.

Concurrently, due to my varied experience and knowledge areas I am seen as a source for career advice. Within both settings however, there are similarities. Mentees often are unaware of their real value to an employer. Moreover, they know their abilities, but cannot translate them into something compelling for an employer. This shortfall often arises when networking and when writing to recruiters.

For example, the narrative is often, “I am good at workflow mapping as seen on project x”. This is incomplete. There needs to be the outcome in terms of “and this helped the company to achieve a faster compliance process”. Another mistake is goal-setting that tends to be too narrow.

Despite the submission of numerous applications, the candidates perceived success is the ideal one or two employers and/or seeking a post that is far too sophisticated for an entry-level candidate. This can dilute the positives and motivation for alternatives.

Career change mentoring is a huge growth area for Finito at the moment. What’s your sense on why that is, and what sorts of trends are you typically seeing in this area?

I look at my experience, having traversed financial markets, teaching/lecturing

and the law. Also, the voluntary aspects, including mentorship. Many changes in focus, that draw on different skillsets.

The bridges I have had to cross have not always been a choice, and the mix of excitement and trepidation was often difficult to grasp so guidance at these moments is invaluable.

In my view, career change mentoring is a growing need due to the pace at which industries are changing. This stems from changing work patterns, the abundance of AI architectures and the shift to platform based solutions.

Many candidates, young and more experienced are attuned to a better work-life balance and as such, are less hesitant to take a leap of faith and restart with something new. This is especially so for those wanting to start their own enterprise.

Who are your heroes who have most inspired you in your career?

These come from several perspectives. Generally I would call on historical figures who despite immense social challenges, took the helm and instigated positive change.

This served as a character building platform for fearlessness and pushing through. Career-wise, there were those with similar backgrounds to mine, that blazed a trail; footballer Viv Anderson playing for England in 1978 (one year after I began my City career), Baroness Patricia Scotland becoming Attorney General in 2007. Also Sir Damon Buffini in the 1990s, as a major force in private equity.

The underlying inspiration from these figures was collectively, their talent, drive and belief in achieving success.

COLUMNS

Our regular writers on employability in 2024

34 | GRACE HARDY: SPREADSHEET QUEEN

E2E’s Shalini Khemka CBE 19 Wikipedia .org

THE NETWORKER-IN-CHIEF

26 Wikipedia .org

BIT OF BEEF

Sir Ian Botham’s swashbuckling career

REMEMBERING STANLEY KUBRICK

Malcolm McDowell recalls the Clockwork Orange director

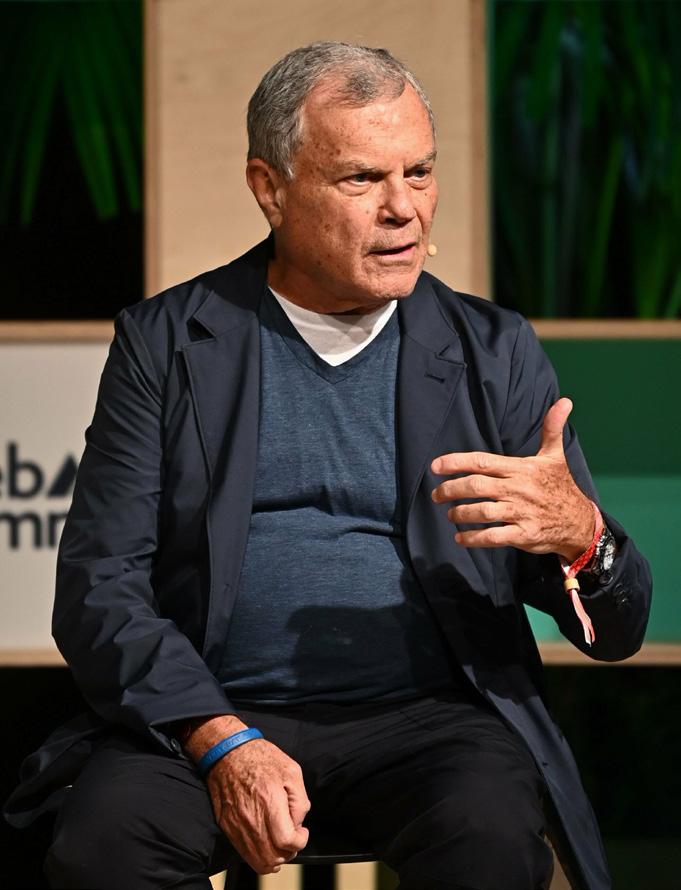

SIR MARTIN SORRELL

THE CHAIR OF S4 CAPITAL ON TRUMP – AND WHERE THE DEMOCRATS WENT WRONG

There were two clear issues in the 2024 US election: firstly, as James Carville put it, it’s the economy, stupid. Secondly, it was the immigration question, though there were some signs in the exit polls that the future of democracy was also important.

The Democrats got it wrong – and the pollsters did too. But then I think Trump, for the second time out of three, has conducted really tactically interesting campaigns. In 2016 he used a San Antonio agency called Giles-Parscale which was run by a guy Brad Parscale with only about 100 employees. It was the days of Cambridge Analytica and personalised data: they ran an extremely effective campaign in 2016.

In 2024, the Democrats outspent the Republicans very heavily. In 2016 they had new media; in 2024, they had a “new-new” media. They only had a staff of about four people; the Democrats had about 100. It’s ironic that the Democrats are left with a bill for £20 million for three celebrity concerts which they’re unable to pay for: I think Trump has offered to pay off the debt.

I thought Trump would win until the last few days. Then I thought the issue with the comedian Tony Hinchcliffe calling Puerto Rico an ‘island of garbage’ in the warm-up at the Madison Square Garden comment – I thought that wouldn’t go down well. I also wondered whether the comments he made about Liz Cheney would have a negative impact on his prospects.

But fundamentally, it doesn’t matter what Trump says. When he once said he could shoot somebody on Fifth Avenue and not lose any votes, he was right. In 2024, he hit the nail on the head over and again and was very disciplined, especially when he

repeated the Reagan line: “Are you better off than you were five years ago?”

He was also very disciplined on the advertising. The Democrats used the “new-old” media: Facebook and Instagram and so on.

Nevertheless, it was a surprise that Trump took the seven swing states, as well as the House and the Senate: it was the scale of the victory more than the victory of itself which came as a mild surprise.

All of this means that Trump is in a very strong position, particularly for the first two years, since there’s usually a reaction in the mid-terms. The stock markets have welcomed the win and Treasury yields have risen slightly and so there are some natural concerns now surrounding inflation. We’ll also see what the impacts of the proposed tariffs are going forwards.

On the Democrat side, I don’t know if it would have made a difference if Biden had pulled out of the race earlier, and if the Democratic Party had had an open convention. I don’t think Tim Walz was a good pick as Vice-President – Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro would probably have been better, but perhaps Kamala was worried about the competitive element there. She didn’t want a strong personality. Going down into the results a little, the Republicans managed to engage with Latinos, with young blacks, and with less college-educated young whites. The other surprise for me was that the Roe v Wade decision and abortion was not as prominent as we expected: women didn’t react as aggressively as we thought they would do.

Of course, Trump’s rallies and speeches were extremely dark. Kamala’s rallies were the opposite, with her smiling a lot – but there was a lack of content. That left a

gap for Trump to make some shrewd moves: to take tax off Americans living abroad; and to take corporation tax down from 21 per cent to 15 per cent as well as lowering income tax. All these were far more substantive than anything the Harris campaign said.

I saw a TikTok of a young black woman with a massive apple in her hand. She said to camera: “Do you know how much this apple costs?” It was a massive apple, about the size of a pomegranate. She said: “I thought it was one or two dollars – but it was seven dollars!”

At the end that was the thing which swung it: the economy.

And going forwards? Trump has put into place a Cabinet and advisors who very much represent what he was going to do.

People say he didn’t expect to win in 2016. This time around, it’s not a surprise and he has the four years of experience. He is somewhat controversial, to put it mildly. But he has firm views.

Whatever business said before the election, deep down they wanted Trump because he stands for low tax and low regulation. Overall, Trump is good for business and good for North America.

Sir Martin Sorrell

SHALINI KHEMKA CBE

THE CHAIR OF E2E ON WHY IT’S IMPORTANT FOR ENTREPRENEURS TO KEEP AN OPEN DIALOGUE

We live in a world where there’s always a route to market. A lot of entrepreneurs talk about experimentation: it’s important to explain what works and what doesn’t. It’s about execution, marketing, getting the funding in, and tenacity. Some people know how to build large businesses, and some are better at running smaller organisations.

Experimentation is so important: those who explore differing products, services and strategies do well, because they’re flexible and recognise that the world can change. Some entrepreneurs have a tendency to procrastinate and are quite stubborn as individuals: it goes back to being surrounded by the right people. You have to have a good community to talk to – and that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re all wired slightly differently, and so you’ll always get a fresh viewpoint.

It’s even simple things, and you might be doing a legal contract and talking to the right lawyer is important. The right legal advice – a small tweak in one clause in a particular contract – can make a massive difference. If you stay insular and stick with the same person you’ve always known, you might not be getting the breadth of advice you need.

Another example is that by listening to the right corporate finance boutiques a business might able to raise their sales price by 20 to 30 per cent. If they’ve experimented in the market they’ve managed to get a better price and better knowledge about how to exit. One of the things I’m really focused on is that we’ve got to be out there and not sitting behind a screen, especially post-Covid.

I think when it comes to selling, it’s about clarity and being honest with yourself as to whether it’s the right term. You have to ask yourself if you were to continue where could you take the business. You also need to be honest about whether you have the financing to do what you want to do, and whether you can get outside finance if you end it. Sometimes it’s worth riding that wave to take your company to the next level.

I find myself advising more companies at the moment. The lack of certainty around taxes, and especially capital gains tax, might make it more prudent to sell sooner rather than later. We’ve gone from 20 per cent to 24 per cent for bigger business, and from ten to 18 per cent for smaller – and I think it’s going to keep going up.

The message which the government is sending is: “The UK isn’t a good place to be wealthy.” A lot of our members are thinking about ways to go offshore and they’re already moving to Dubai and Saudi Arabia. With Trump coming in, I suspect many will move to America too.

On the question of outside investment, I’m very fortunate as I have amazing investors. They have more confidence in me than I have in myself. If you can do it through organic growth it might take a few years longer, but it's a much more straightforward journey on your own. If you’ve got a good enough product you should be able to sell it, and if you can sell it you should be able to make money.

It can be quite dangerous as you end up thinking you have more money than you actually do: you have to know if

your product is selling. One thing a start-up founder has to know is that their product is desirable and that the pricing is right. I remember talking to Gerry Ford, the founder of Caffe Nero. It was very interesting: he started his first shop in South Kensington and he didn’t open his second one until he knew the first one was making money, fully funded and making profits.

I’m a believer in going back to basics: don’t raise money if you’re not sure you can sell. Outside investment changes the dynamics and it changes you as a person: there’s a different level of stress when you have external funders. You’ve got other people’s money in your hands: it can be romantic at the beginning, but it’s a big psychological shift which entrepreneurs shouldn’t underestimate.

I would say it’s a good idea to accept money only once you’ve proven to yourself that you can sell – then you can go to other jurisdictions, with other products.

Shalini Khemka CBE

FATIMA WHITBREAD MBE

ONE OF BRITAIN’S GREATEST ATHLETES EXPLAINS HOW SHE GAINED AN EDGE IN COMPETITION

Looking back I was prepared to do whatever I could to gain an edge. First of all, you are what you eat. For me, when I was a competing athlete I was constantly working hard in the gym – three times a day training. I wasn’t that tall: I’m five foot three and most of my competitors were six foot. The important thing was I needed to be sure I was technically very sound.

I realised my diet had to be right – I was losing weight from the training and needed to maintain a certain weight. In the build-up to my being World Champion I was on a diet of about 8,000 calories a day. That’s a huge amount because on average women consume 3000 calories a day – but I was burning it all off. The diet I took was properly designed for me to have lots of iron: so I took in lots of offal, and had a special drink with raw eggs, banana and milk in a blender. I made sure it was all protein-based.

It was basically body-building and sculpting: it was about eating the right kinds of food – and then in training making sure you’re the right shape to maximise performance.

Back then we didn’t have the tools we have now. VHS was the main recorder. I would record everything I saw with regard to technique. I could analyse the footage mechanically and technically as to the different shapes and sizes of the different athletes I was competing against. I could observe their speed and velocity, their leg movement, the position of the hand, and the position of the javelin.. It all varies from athlete to athlete.

For me it was all about learning in that level of detail, and I suppose I was doing it way before my time. I really did my homework. When I’m passionate, I don’t hold back.

I always saw the javelin as a weapon of war: kill or be killed. When you step into the arena, you’re going back to Greek ancient times. The need to step on the runway was about claiming my territory: if I didn’t claim that and own that, then why was I there? The idea was to be able to know everything you needed to know and have a close affinity – a sort of love affair – with your javelin. It was a passion: to become the best in the world, you need to know everything that can be known about javelin-throwing and the disciplines you engage with.

I started as a pentathlete in the early days and trained very hard. I would sprint with Daley Thompson: as a young man, he was incredibly dedicated to his work. My mum was a javelin coach. I also did sprint training with our then golden girl Donna Hartley. It was a fantastic era for track and field, I suppose partly because it was a period when there was a lot of trouble with football and hooliganism. We became the number one sport.

It’s mind over matter. Ninety per cent of the mind application is based on preparation and training. As an athlete I understood there are two championships going on: with yourself and in the arena himself. Rory McIlroy at the 2024 US Open when he missed that crucial putt, was battling with himself. I could always sense what was going on in the arena in terms of psychological warfare: I never let that distract me. When you’re doing

sport at that level you have to have tunnel vision to keep your focus on what you’re doing.

You’ve got six throws and every throw counts. I taught myself the skill of being able to perform as well on my last throw as on my first: I might often win a championship on my last throw. Anyone can do an amazing throw – and suddenly perform out of your skin.

The press might tell you that you are number one and should win. But if you think like this, and start to wonder if you’re going to get gold, silver or bronze, you’re in the wrong mindset.

There’s always great expectation – from friends and family, from yourself and from the public. It’s fairly easy at the start of your career when nobody expects anything of you. Then the expectation and the pressure starts to creep in. The only way to cope with that is mind application and doing your preparation and being able to fall upon your experience.

Visit www.fatimascampaign.com

Fatima Whitbread MBE

SIR BERNARD JENKIN

THE VETERAN PARLIAMENTARIAN CHARTS

HIS ILLUSTRIOUS CAREER

Istartedmy career having decided I wasn’t going to be a musician. That was what I went up to Cambridge intending to do – but I got drawn into politics and in the end studied music for a year but took my degree in English Literature. I then went into business. I joined Ford Motor Company for four years and then spent six years in the fledgling private equity business.

A big influence in my life had been my father who had been in Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet. Much to his surprise I chose a political career. I got elected at the tender age of 33. I was keen, diligent and ambitious. I immediately ran into difficulty because I opposed the Maastricht Treaty, which didn’t endear me to the Major administration.

After a period in the Shadow Cabinet, including two years as Defence Secretary, I rather fell out with David Cameron. It was over the conduct of candidates: he was determined to bring in all-women short lists. I kept telling him: if you do this, you won’t get it through the party, and secondly it’s probably wrong in principle. We’re a Conservative Party.

Then I went on the Defence Committee and started a new phase of my career. After 2010, I became the chair of the Public Administration Select Committee. I’ve always been interested in Whitehall and why it doesn’t work as well as it should. In Defence, I had become interested in who writes the UK’s grand strategy. I had bumped into the Chief of Defence Staff at the time Jock Stirrup and I asked him that question. He said: “That's easy: nobody.” The first enquiry was into that question.

It got immediate pushback from the establishment. David Cameron said he didn’t want strategy, but wanted to remain flexible. He didn’t understand the difference between strategy and a plan. There’s the old adage: no plan survives first contact with the enemy. We did a series of reports in strategic thinking in government. There was increasing dialogue with the likes Cabinet Secretaries Jeremy Heywood and Mark Sedwill about how Whitehall can work better. In 2019, the House appointed me Chair of the Liaison Committee. To start with I was very wary – there was a degree of resentment over the manner of my appointment as I’d been appointed by Resolution of the House instead of being voted in by the Committee.

I had to tread carefully, but as my term progressed, people understood that I was being consensual. During this period I formed the Strategy Group, which I coshare with George Robertson the former NATO Secretary-General and former Labour Defence Secretary,

Much of the discourse about the civil service is negative and destructive. If you just call it a blob, frankly you just annoy everyone. I say to ministers: the system’s not going to work for you unless officials feel engaged in what they're doing, and if they feel undervalued and dismissed it won’t work. Margaret Thatcher wasn’t brilliant all the time at motivating the civil service to her advantage. In those days, before open recruitment, it was much easier to plan people’s careers. Ministers could make sure the right people were in the right place. Today there is a lack of continuity and expertise in Whitehall.

This engagement with the senior civil service led to another report on Strategic Thinking this time by the Liaison Commitee. This report, released just before the 2024 election, makes a number of recommendations to the government. So that the civil service can better understand the concept of strategy. This is what they do in the Armed Forces, which is one of the reasons they’re so effective.

You always get some pushback from the civil service when there needs to be change. Actually, there needs to be far more red-teaming and tabletop exercises of scenarios – and not just in foreign policy but in other areas too: in energy policy for instance, or education or health.

This idea that there is some magic policy that’s going to fix Whitehall is false. Many civil servants have seen it so many times. I’ve talked to civil servants who say: “New minister, new crisis – I just dust off the old paper I did five years ago!” Change will take time and patience, but it is achievable.

Sir Bernard Jenkin

AHPO, 115M, LURSSEN, 16 GUESTS

LUXURY travel REDEFINED.

WFRANCES D’SOUZA

THE FORMER SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS GIVES AN UPDATE ON THE SITUATION IN AFGHANISTAN

hat one doesn’t realise is how avid girls are for education. What we do at Marefat is to make sure that every now and then we have a Zoom meeting with our pupils in Afghanistan. We run empowerment sessions which are run by Aziz Royesh from Washington and the girls crowd into their rooms.

Recently we had the girls speak about what a difference being able to access education has made to them. It was emotional and heart-warming. These are girls aged 14 and 15, and they said things like: “We thought our lives were finished and we were going to be married off.” Now they have hope – and they know that hope is tied to education.

Our goal is to get these girls educated at secondary level and then put them up for scholarships, some of which Lord Dennis Stevenson may consider funding. The goal of Marefat is to educate a whole cohort of women so that they can come back and be in the major professions: Afghanistan needs journalists, lawyers and surveyors. In fact, quite a lot of them want to do engineering too.

Since the Taleban came back we aim to teach in cells – or cluster education as it’s called. That will be quite difficult – and especially difficult to teach science. The project envisages girls gathering at abandoned schools. It could be cost-effective because there won’t be expensive school buildings to maintain but textbooks and teachers’costs have to be covered.

Education is the magic bullet of development. If you can educate John Arlott (Wikipedia.org)

girls, you get development in terms of later marriage, and fewer children. Wherever you see education beyond the primary school level of girls you see significant change in that society.

Of course, the events of 2022 were devastating for these girls. But all is not lost. What some of these girls are doing is teaching their parents or their younger siblings how to read. If you educate a child, you educate a village.

More broadly, if you help someone, you don’t just help that one person: you help that entire ecosystem. We should be enjoining development agencies to support those strategies which people employ in vulnerable societies at times of hardship: these methods are typically highly intelligent and based on attuned survival instincts.

Often what we see in these societies is diversification of income. A woman I know in Southern Africa brews beer, grows crops and makes baskets for the market. She sends her children off to work and builds transactional relationships with relatives in nearby towns. This creative networking and pluckiness serves them in good stead.

We need to have respect for what works. We understand that it’s very important in these countries to teach the practicalities of life. What first attracted me to Marefat was its vocational training: there has always been this emphasis on mechanics and electrical engineering as there were some who didn’t go onto academic careers.

It’s important that we learn the lessons domestically. In the wider

world, we should all be supportive of apprenticeships. We must ask ourselves what the point is of our children going to a minor university and doing a degree in media studies. The experience of university might be useful, and it may teach you how to think. But it’s so much better to be an apprentice.

It really gladdens one’s heart to see children being able to take pride in creating and making things. We don’t have enough emphasis on this. Fashioning a ceramic pot is useful and non-useful. One thinks of the beauty of some pots – the attention to detail and the way the clay is treated. It is exciting to think about all there is to learn.

I sometimes think about how we teach beauty. Sometimes you see something and it’s complete and beautiful: everything’s in its right place. The world isn’t like that, as we know – but my passion is to do what I can to make it better.

Frances D'Souza

The Cricketer SIR IAN BOTHAM

SIR IAN BOTHAM’S JOURNEY OUGHT TO BE VERY INSPIRING TO THE NEXT GENERATION, WRITES GEORGE ACHEBE

Inperson, Ian Botham is utterly solid, calling to mind a rugby prop forward more than England’s greatest cricketing all-rounder. Botham is a famous wine enthusiast, and hunched over his lunch as if he could easily eat one’s own meal as well, it would be a lie to say one can’t see that he’s enjoyed himself from time to time.

Botham is one of those very few sportsman whose achievements carry across the generations. Sport is really to do with the dramatic maximisation of the present moment: we are rarely quite so conscious of life as when we watch closely to see whether a ball has nicked a bat. Especially because there is so much of it, little sticks in the mind.

1981 AND ALL THAT

Something about Botham did: it was to do with the fearlessness with which he played the game, allied always to a certain laddish humour which is still in evidence today. Especially Botham is known for the Ashes in 1981 now forever known as Botham’s Ashes, when Botham’s swashbuckling 149 not out at Headingley began an unlikely set of events. Not until 2005 would cricket come alive in this country to anything like the same extent.

When we think back on that test match, it should really be Bob Willis’ test, since it was Willis, who died of cancer in 2019, that took 8-43 to bowl out the Australians. Willis hangs over lunch, since Botham is here to raising money for the Bob Willis Fund which raises money for better prostate cancer research.

Botham tells a wonderful anecdote

about that storied day in 1981: “Australia needed a 130 to win. The Australians were 50-1. Bob comes on, and turns to Briers [Mike Brearley, the then England captain] and he said: ‘Any chance I could have a go down the slope with the wind?’ He steamed in and took 8-53.”

This led to an amusing administrative issue over the unexpected celebrations which Botham, as the world knows, enjoyed more than anyone. “We had this young lad – Ricci Roberts, a 140 year-

old: he was over from South Africa as a runner. I said to him: “Look we haven’t got any champagne, because obviously we thought we weren’t going to win the game.” The Australians thought they would. I said to Ricci: “Go and knock on the Australians door, and be polite and just say: ‘Could the England boys have a couple of bottles of champagne, please?” He did exactly that, but added on the end: ‘Because you won’t be needing them’.”

Ian Botham (Alamy)

“COULD THE ENGLAND BOYS HAVE A COUPLE OF BOTTLES OF CHAMPAGNE, PLEASE?”

The Australians may not have reacted well. Botham continues: “Ricci came through the door horizontal. He had one bottle in each hand and he didn’t spill a drop. Ricci Roberts went on to be Ernie Els’ caddie in all Ernie Els’ major wins. That was down to what we taught him –and how Bob taught him to pour a pint.”

THE TWO GEOFFREYS

At Lord’s, alongside the extraordinarily likeable Geoff Miller, Botham gave a jovial tour through his career, joking that Geoff Miller was ‘the livelier of the two Geoffreys I played with’ referring to his long-running grudge against Geoffrey Boycott, who Botham famously ran out in Christchurch in 1978. On that famous

occasion, Boycott was batting at his usual glacial pace when the situation required runs. Botham picks up the story: “I was asked by Bob, who was then the vicecaptain, to run him out and I said: “I’m playing my fourth game and he’s playing his 94th.” Bob replied: “If you don’t do it, you won’t play your fifth.”

It is impossible to not feel nostalgic about the fun of those times. Botham has come a long way. In fact, when Botham recalls his upbringing, as is usually the case with the extraordinarily successful, his story comes into focus in all its glory and improbability: “My father was in the services in the Navy and was serving in Northern Ireland on active duty. When his wife Marie, my Mum, was due to give birth, they sent us over to Heswall in Cheshire.”

CRUNCH TIME

The family then moved down to Yeovil and Botham, having shown exceptional sporting prowess, had a difficult decision to make by the age of 15. “I had to make a choice between soccer and cricket. Crystal Palace offered me an apprenticeship. I had just signed at 14

with Somerset – I registered with them and when it came to the decision, I sat down with my dad. He said: “You are by far a better cricketer”. I listened to him – for once.”

Botham then transferred to Lords for a year and half, before being called back to Somerset at 18. It didn’t work out too badly, did it? Botham smiles: “Not too bad.”

“THE WAY THEY DID IT IN THOSE DAYS – WELL, LET’S JUST SAY IT WOULDN’T HAPPEN

NOWADAYS.”

Botham recalls his first test match. “The way they did it in those days – well, let’s just say it wouldn’t happen nowadays. You’re driving down a motorway. At three minutes to 12 you turn into a layby and switch the radio on and wait for the 12 O’Clock News. And the

Ian Botham batting vs_NZ, February, 1978 (Wikipedia)

England team to play Australia is…And I thought: ‘Yes, I’m in’.”

That sent Botham up to Trent Bridge, where another lovely anecdote occurs. “We lined up at the start of the game and it was the Queen’s Jubilee. The Queen went down the England line, and wished me luck on my debut. Then she went over to the Australia line, and came to DK Lillee [the great Australian fast-bowler].

“Dennis pulled out of his back-pocket an autograph book. “Ma’m, would you sign this?” She said: “I can’t do that now.” But clearly the Queen had remembered the encounter. Botham continues: “When Lillee got home from the tour six or seven weeks later, through the letterbox there came this envelope with the Royal seal and there was a picture of the Queen. It now sits on his mantelpiece.”

MERV THE GREAT

It’s a lovely story – and the more time you spend in Botham’s spell, the more the stories keep coming. Merv Hughes

also gets the Botham treatment. “In 197778 we toured Australia, one of my first tours. We were sponsored by a company called JVC Electronics. They decided in their infinite wisdom that on the rest day morning at about 10 o’clock – when most of us had only been in bed 10 minutes – we’d go to a shopping mall in north Melbourne to mingle. None of us were particularly excited about that prospect.”

So what did Botham do? “I hid behind this tower. This young lad came up in a tracksuit and said: “Good day, Mr Botham. Mate, I want to be a fast bowler have you got any advice for me?” I wasn’t feeling great so I said: “Mate, don’t bother – go and play golf and tennis.”

Fast forward to 1986: the first test at Brisbane. Botham recalls: “Merv Hughes makes his Ashes debut in that game. In Brisbane, you could see this little black line, that in about 30 minutes became a thunderstorm – hailstones the size of golf balls. Hughes bounces it in, then the gigantic hailstones. Merv wasn’t happy as I’d hit him for 22. We weren’t

going to play anymore, the ground was covered with these golf balls.

“One of the lads brought me a beer. Merv comes out and I say: “Congratulations on your first Ashes.” He said: “You know we’ve met before.” I said: “No. Where?” “At the shopping centre in Melbourne.” I was that kid who came running up to you, and you told me not to be a fast-bowler but to play tennis and golf.” He said: “What do you reckon now?” I said: “I was bloody right.”

Beneath the swagger of the public persona, there is his immense generosity as a philanthropist and his life as a family man. His grandson, James, is following in Botham’s footsteps as a sportsman. Botham speaks with evident pride: “He’s had a couple of years with injuries. His confidence is back – he played very well against South Africa at Twickenham. James was born in Cardiff and said: ‘I’m playing for Wales’. He’s got a task on his hand and we’ll see.”

A DECISIVE DIFFERENCE

But it’s the philanthropy which really brings a tear to the eye. “I’m very proud of it,” says Botham. “In 1977, I was playing against the Australians and stepped on the ball and broke a couple of bones in my foot. In those days you didn’t stay with the England squad, you got sent back to your mother county. Mine was Somerset. So I get to Musgrove Park Hospital in Taunton, the club doctor’s waiting for me. To get to the physio department you had to go past the children’s ward.”

This turned out to be a fateful walk since it would change many peoples’ lives.

“You can see children who are obviously ill – tubes sticking out, and their feet up. There were four lads sitting round the table playing on the board games. I said: “Are these guys visiting?” He said: “No, they’re seriously ill.” I said: “But they look fine.” He replied: “You’ve got

eight weeks of intensive treatment to get it right for the tour. Those four lads in all probability will not be there when you finish your treatment. True enough at the end, all four of them had passed away.”

It made a deep impact on Botham who found he couldn’t stand by and do nothing. “What the hospital used to do was give them a party, whether for one of their birthdays or for Christmas. And they were so drugged up with painkillers. As I was leaving the hospital, I said: “Is there anything we can do to help?” He said: “Well, you’ve now seen four parties. We don’t get any funding for those.” I said: “I’ll stick my hand up and pay for the parties.”

By mid-1984, Botham wanted to do something more substantial. “I was flicking through a magazine which someone had left on the train – a colour supplement. There was an article about a certain Dr Barbara Watson, who lived on the south coast. Every summer she

would get on the train and go to the most northerly part of the UK, John O’Groats and meander back. I thought: “Right, I’m going to do a sponsored walk. I’m going to do John o’Groats to Land’s End. My geography wasn’t great. Four hundred miles to the English border, then 600 miles to the Land’s End.”

“BY THE END OF THE WALK WE GOT OVER £1MILLION. THAT WAS USED IMMEDIATELY TO BUILD A RESEARCH CENTRE OUTSIDE GLASGOW.”

It was a huge learning curve for Botham who had never walked like this before, but he managed to do the walk in 33

days. “You couldn’t do PayPal: you had to physically collect. By the end of the walk we got over £1million. That was used immediately to build a research centre outside Glasgow.” Then the conglomerates came behind us. “When we started the walk, there was a 20 per cent chance of survival for kids with leukaemia – a few years ago we announced it is now 94 per cent.”

It’s an astonishing story of how something so innocent as being good with a bat and ball can lead with the right heart and mindset to genuinely consequential change. Botham’s is a reminder to us all to start with what we’re good at – but to keep an eye out for what we might do for others along the way.

Lord Botham was talking at an event at Lord’s Cricket Ground in aid of https://bobwillisfund.org/ https://www.beefysfoundation.org

A Question of Degree DAVID LANDSMAN OBE

ARE LANGUAGE DEGREES USEFUL? DAVID LANDSMAN ARGUES THAT THEY’RE HIGHLY UNDERESTIMATED

In Britain we often like to play down our skills and achievements (except perhaps in sport). There’s nothing wrong with a bit of modesty. But I’m not sure we do ourselves – or the next generation – any favours if we end up boasting about how bad we are at something or another. We rightly admire those who have overcome, say, dyslexia to achieve academic success and a great career. But it’s decidedly odd how people make light of not being able to do maths (“not really my thing, thank goodness for calculators”). I’ve never heard anyone in Asia, for example, boasting about being functionally innumerate…

We’re also a bit too ready to shrug off

being monolingual in what is, without doubt, a multilingual world. Pretty well everywhere you go, you’ll meet people who take speaking multiple languages for granted. I once visited a village school in Eastern India: the schoolgirls, aged from 8-12, spoke to me in reasonable English, one of the five languages they could communicate in. In many countries, people speak one or two “home” languages, but I’m not sure our culture values these skills highly enough. I remember asking a South African lady how many languages she spoke. Her initial answer was “just a bit of French from school [in addition to English]”. After a few more questions, she admitted that she spoke a couple of African languages, but hadn’t thought it worth mentioning…

My own story with languages, like most, started at school, in my case with French and Latin, followed a year or so later by Ancient Greek. I recall my teacher saying that the best thing about the ancient languages was that they had no practical use – probably not the best motivational talk for a twelve-year-old boy!

But what I found exciting about Greek and Latin was their sheer “otherness”: new words, new grammar (and lots of it) and new ways of expressing yourself, for example in Greek you express the idea of “if only…” with a whole new piece of grammar (the optative mode for anyone who’s interested). The puzzles that you have to solve in order to decipher complex constructions are the classics’ answer to a tough computer game or Sudoku.

It was, in my case, the language puzzles rather than the ancient history or archaeology that persuaded me to opt for classics at university. But before starting my degree, I spent a few months in Greece, which without making me change my degree plans, ultimately changed everything. Within a minute of landing in Athens, I realised that the linguistic skills which had landed me my place at Oxford wouldn’t let me read most of the signs at the airport, still less order a beer.

That’s when I decided to spend as much as possible of my time in Greece learning the modern language which, apart from being of more use in the bar, also got me fascinated by how the language had evolved. I took this fascination with me to university where I studied philology (the history of languages) as part of my degree and with that went on to do a Masters

David Landsman OBE

and PhD in linguistics (the structure and behaviour of languages), focusing naturally on Modern Greek.

I can’t say that my languages were an essential part of my path to the Diplomatic Service, but they certainly helped me once there. The British Foreign Office doesn’t require candidates to speak foreign languages before they arrive, but instead uses a (pretty reliable) language aptitude test to find out who’s best suited to being trained in the most difficult languages.

In my own case I soon found myself being sent off to fill a gap in the Embassy in Greece, belying the old joke that if you speak Russian, they’ll send you to Brazil. Later I learned Serbo-Croat and Albanian for postings in Belgrade and Tirana; I also took a course to improve my French which is still a key diplomatic language; and have acquired along the way varying amounts of German, Turkish and Hungarian, though not as much as I would like.

Today, after over a decade in business, I’m still at it, trying to improve my German (an important wedding to attend next year) and taking an online course in Russian with a brilliant teacher, just because I can. I’m a strong believer in the BOGOF principle of languages: learn one, get another if not actually free, much “cheaper” as every language you learn trains your mind to learn the next one.

There are so many ways to learn languages, and different things you can be good at. I’ve got quite a good ear, so sometimes my pronunciation can be deceptive and give the (dangerous) impression I know more than I do. On the other hand, I’m no artist, which always put me off languages like

Chinese and Thai as I’m sure I couldn’t master the elaborate writing systems. You can learn by reading classic literature if you like, but if you prefer the news, or social media, or films, it’s your choice. My wife has to put up with me listening to songs in whichever language I’m focusing on at the time.

But is it really worth learning languages, when “everyone speaks English”? First, it’s good for you. There’s plenty of evidence that language learning staves off Alzheimer’s because it’s a great form of gymnastics for the mind, which makes sense even if you’re far too young to worry about losing your memory.

“IF YOU TALK TO A MAN IN A LANGUAGE HE UNDERSTANDS, THAT GOES TO HIS HEAD. IF YOU TALK TO HIM IN HIS LANGUAGE, THAT GOES TO HIS HEART.”

Languages are an excellent way to understand quite how differently it’s possible to think. Take colours, for example: some languages don’t distinguish between “blue” and “green” and have a single word covering both. On the other hand, Greek and Turkish have completely different words for light and dark blue. So if you’re speaking one of these languages, you’ll see light and dark blue as differently as we see, say, red and pink.

This opens up a new world of understanding difference, going well beyond colours to the essence of people and civilisations. And when you

understand better, you can communicate better. Nelson Mandela might have been talking to diplomats when he said: “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.” But it’s not just diplomats who need to communicate. As former German Chancellor Willy Brandt is reported to have said: “If I’m selling to you, I speak your language. If I’m buying, Dann müssen Sie Deutsch sprechen”. Prosperity depends on trade, and trade depends on dealing with abroad. Language learning isn’t just an academic exercise. I’d like to see more businesspeople, not just teachers, speaking up for language learning.

If I were back at school today, what would I want to study? To be honest, I’m not sure it would be classics (maybe my old teacher had a point). But perhaps it wouldn’t be a pure languages degree either. I was talking recently to students about languages at a secondary school in London and was struck by how many were thinking about taking a course combining a language with another discipline. There are many more such courses today and they look to be well worth exploring. You choose law or business or maths, while getting all the benefits of studying a language at the same time. You prove that you can acquire a valuable real-world skill while giving your mind two different types of gymnastics at the same time. And don’t worry if you can’t decide which language to study: once you’ve tried one, there’s always BOGOF (buy one get one free).

David Landsman is a former British Ambassador and senior executive. He is now Chair of British Expertise International and the author of the Channel your Inner Ambassador podcast.

DR VANESSA HERDER

THE VET WHO BECAME A SCIENTIST EXPLAINS WHY ACADEMIA IS A GREAT PLACE TO WORK

Kid,do what you like. Choose what you want.” This was the career advice my parents gave me during my last year at school. Ok, then. I want to become a vet. They were delighted and my mum painted pictures in her mind of me being the local vet in a small village somewhere. All neighbours would come and bring their pets to me and she could be involved in the romantic life of the female version of James Herriot. But it turned out to be very different.

Now as a scientist, my latest research project is studying the differences in the immune response of patients with a Covid-19-induced pneumonia. We investigated in SARS CoV-2-patients which immune response determines the disease severity. This study is a large collaborative project with scientists form the UK, Malawi, Brazil, USA, France

and Switzerland and published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. How can a vet be involved in this project?

“MY PASSION FOR STUDYING DISEASES WAS IGNITED.”

During my vet degree I realised quite quickly that my original idea of working with horses would not be happening. During my first lecture of pathology while learning about disease mechanisms in tissues my passion for studying diseases was ignited. On that day, I knew horses will always be a hobby for me. My fascination about understanding how diseases evolve in the body grew from day to day. Studying diseases does mean to understand what health is.

How a virus infects the host, causes damage and how the body is able to fight this infection successfully is not only interesting, it is dependent on the orchestration of so many factors. It fascinates me. I finished my first PhD studying virus infections in the brain and a second PhD followed to characterise a newly emerging virus infection in animals which caused stillbirth and brain damage in ruminants.

As a vet, I knew how close we are to our pets or farm animals, and my research always focussed on aspects of the OneHealth approach: Diseases which are transmitted from animals to humans. To strengthen my research I decided to stop doing diagnostic and teaching vet students and started a full time post as a scientist. For years, I was studying which immune reactions determine that some

Dr Vanessa Herder

hosts show a severe or lethal outcome in virus infections and why some show a mild course of disease. I developed all the tools to address this question, and worked in the high containment lab with a virus, which can only be handled under these conditions.

Then the pandemic hit, the government stopped all our virus work. Only SARS CoV-2 from now on. The joint and focussed research activities were used to study the pathogenesis of Covid-19. I applied all the skills I developed before the pandemic, including being trained for the high containment, on the Covid-19 response to contribute as much as I could. Visualising the virus in the lung, which had never been done before, was one of my tasks, and it was a tough one. It took several months. At this time, I realised how valuable it was that the PhDs I made not only taught me science.

Most importantly, the PhD teaches grit and endurance as well as creativity. The perseverance of starting and finishing a PhD, which lasts four years, requires scientific depth and dealing with all the challenges along the way. In short, you need to have a very long breath. This helped me to keep going with the initially unsuccessful virus detection attempts in the tissues. I finally made it and will never forget the sunny

afternoon on a Saturday during the hard lockdown, when the virus finally was visible in the lung.

Like all projects and publications in excellent research, the people involved are key to success. Interdependence of independent people working together is the heart of the work. Only efficient priorisation with well-developed communication and the perfect alignment of different expertise make it happen. In this study, every co-author of this manuscript did what she or he could do best and contributed it. The efforts were organised and managed from Brazil to Malawi, Switzerland, USA and France to the UK and required a smart project management system. Science connects people, cultures and experiences and this makes academia a beautiful place.

During my time in academia I had the pleasure to work with so many driven and smart students, which is a joyful experience and which taught me so many valuable life lessons. I am fortunate to have great mentors pushing me to do the best work, opening doors for others and myself and allowing me to see further with their experience. Thanks to the diversity of my work, I know people in so many countries of the world, who became friends and part of my life.

“SCIENCE CONNECTS THE DOTS OF KNOWLEDGE AND UNITES PEOPLE.”

And it’s the people who drive the research to the next level. The most rewarding aspect of working in academia is to be part of the career path of the younger generation, seeing them succeed and choosing the work they want. Eventually, progressing from a job to a profession leading to a passion. Each student is a special person in my life as they trusted me with being part of their academic career and there is nothing better than meeting these people after years again and reflecting together on our journeys.

“I AM LIVING THE ROMANTIC LIFE OF A SCIENTIST WHO CAN TRAVEL THE WORLD FOR PRESENTATIONS AND CONFERENCES.”

I am not living the romantic life of the female version of James Herriot. I am living the romantic life of a scientist who can travel the world for presentations and conferences, and works with researchers in places like India, Africa, Europe, USA, China and the Middle East. Basic research is the joy of answering questions in unknown territories combined with an unparalleled work ethic. Understanding diseases is understanding life – in animals and humans alike.

Dr Vanessa Herder

GRACE HARDY

CONSIDERING AN ACCOUNTANCY CAREER? SUCCESSFUL

ACCOUNTANT GRACE HARDY GIVES HER ADVICE

Growing up with dyslexia wasn’t easy. School was often a frustrating experience for me. I struggled with reading, writing and spelling, which made traditional learning environments incredibly challenging. I often felt like I couldn’t keep up with my peers, and my confidence took a hit.

The thought of spending another three or four years in a similar environment at university filled me with dread. I couldn’t afford to go to university without getting a job on the side and I was worried that doing a degree wouldn’t set me apart from others when I’d eventually have to find a graduate scheme after.

During this time of uncertainty, my mum introduced me to the world of apprenticeships. I’ll be forever grateful for her suggestion because it opened up a whole new realm of possibilities for me. The apprenticeship route appealed to me because it offered a different way of learning – one that suited my needs better. It promised hands-on experience, practical skills, and the opportunity of earning money while learning. Plus, the prospect of no student debt was certainly attractive!

“I SECURED AN APPRENTICESHIP WITH A TOP 10 ACCOUNTANCY FIRM, AND IT WAS A GAME-CHANGER FOR ME.”

I secured an apprenticeship with a top 10 accountancy firm, and it was a gamechanger for me. At 18-years-old I was on

a £20,000 salary; I was over the moon. This gave me the financial stability I had been craving. From the very first week, I was working on real client projects and given responsibilities that expanded my portfolio and experience. Despite having no prior accounting knowledge, the firm provided comprehensive training and created a nurturing environment for me to learn and grow.

As I progressed through my apprenticeship, I began to see the inner workings of different businesses. This exposure was invaluable and sparked my entrepreneurial spirit. I realised the skills and the knowledge I was gaining could potentially be used to start my own accounting practice one day.

After completing my apprenticeship and gaining my AAT qualification, I decided to take the plunge and start my own firm, Hardy Accounting, at the age of 21. It was a scary but exciting move!

The transition from employee

came