Gender norms and resistance to change in African education

Cases of Burkina Faso, DRC, Sao Tome and Principe and Chad

Authors

This study was supported by IDRC and KIX-GPE. However, the ideas and opinions presented do not necessarily represent those of these organizations.

The study was carried out as part of a partnership between the African Educationalists Forum (under the supervision of Dr. Bity DIENE) and Research Laboratory on Economic and Social Transformations (under the coordination of Pr Rokhaya CISSE) under the KIX Gender Norms project.

List of authors

Dr Koly FALL, Sociologist

Ms Binta Rassouloulah AW, Pedagogue, Education Inspector

Mr Pathé DIAKHATE, Statistical Engineer and Economist

Ms Binta DIEDHIOU, Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist

Ms Mame Diarra Bousso NDIAYE, Community Health Specialist

Pre Rokhaya CISSE, Sociologist

Pr Abdou Salam FALL, Socio-anthropologist

Acknowledgements

Warm thanks are extended to the various Ministries of Education in the four countries: Burkina Faso, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo and Sao Tomé & Principe, for their institutional support in carrying out this study.

We are grateful to FAWE's national offices in Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sao Tomé & Principe and Chad for their participation, support and facilitation.

Our thanks also go to the country researchers: Dramane Boly from Burkina Faso, Lotus Nzosa from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Edson Da Costa from Sao Tomé and Principe, and Robertine Dénodji from Chad, who took part in the various phases of the study.

Acronyms and abbreviations

AME Association of Mothers Educationalist

APE Parents' Association

CESA Continental Education Strategy for Africa

DME Deprivation and Marginalization in Education

FAWE Forum for African Women Educationalists

IFAN Black Africa Essential Institute Cheikh Anta Diop

UIS UNESCO Institute for Statistics

LARTES Research Laboratory on Economic and Social Transformations

ODD Sustainable Development Objectives

PTF Technical and Financial Partners

GROUND FLOOR Democratic Republic of Congo

STP Sao Tomé and Principe

TBS

Gross enrolment rate

UCAD Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

VBGMS Gender-Based Violence in Schools ‘GBVS’

List of charts

Chart 1: Operating framework for the concept of social gender norms 7

Chart 2: Proportion of girls enrolled in school in surveyed students' households (%) 21

Chart 3: Proportion of students surveyed who feel their access to school was difficult/easy (%)

Chart 4: Factors making it difficult for girls to go to school, according to students (%)* 23

Chart 5: Proportion of parents stating that girls have more difficulty than boys in accessing school (%) ................................................................................................................................25

Chart 6: Proportion of parents encouraging their daughters to go on to higher education (%)27

Chart 7: Top-performing pupils at school according to parents of pupils surveyed (%).........29

Chart 8: Main factors that prevent girls from staying in school, according to the students surveyed (%)* ..........................................................................................................................31

Chart 9: Proportion of parents who agree that social norms in their community promote gender equality at school (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 10: Proportion of parents reporting that social gender norms influence women's career choices and aspirations (%).............................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 11: Students' and parents' assessments of the burden of household chores (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 12: Proportion of students who say housework affects their performance at school (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 13: Teachers' perceptions of favoritism towards girls/boys, according to students surveyed (%) ...................................................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 14: Proportion of students surveyed who feel free to express themselves in class (%) .........................................................................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

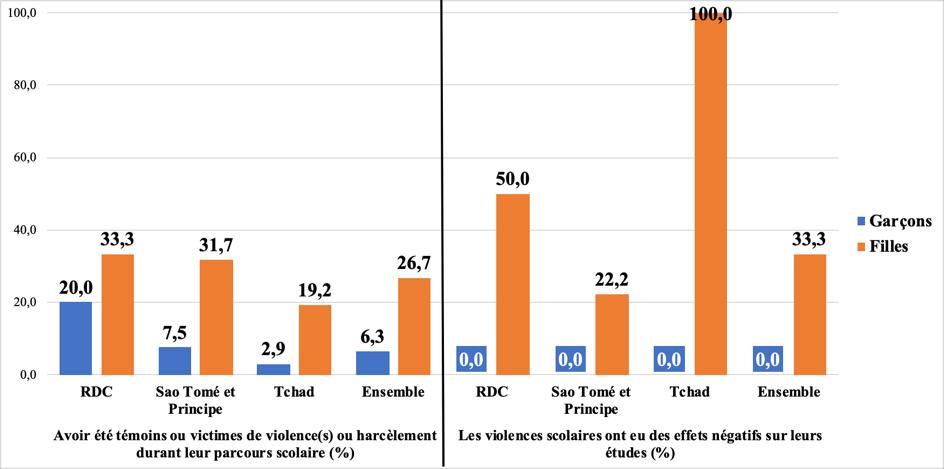

Chart 15: Proportion of students surveyed declaring :....................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 16: Proportion of parents surveyed who say there are unfavorable norms for girls' schooling (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 17: Proportion of students surveyed stating that their community's beliefs are unfavorable to girls' schooling (%) .....................................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 18: Proportion of students surveyed who say that domestic chores keep girls out of school (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 19: Proportion of students surveyed who say it's more important for a girl to get married at a young age than to continue her studies (%)..............................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 20: Proportion of students surveyed who agree that girls and boys have equal access to education in their community (%)...................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 21: Proportion of parents who think girls should have the same educational opportunities as boys (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 22: Proportion of students surveyed who say that teachers encourage them to participate more in class (%).............................................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 23: Proportion of students surveyed reporting participation in boys' and girls' empowerment clubs (%)..................................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Chart 24: Proportion of parents surveyed stating that girls should hold positions of responsibility at school (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

List of appendices

Appendix 1: Socio-demographic profile of surveyed students (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Appendix 2: Socio-demographic profile of surveyed parents (%)..Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Appendix 3: Proportion of surveyed girls who say they don't attend school during their period (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Appendix 4: Top-performing pupils at school according to parents of surveyed pupils, by gender (%) Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Appendix 6: Proportion of students who say that girls' and boys' empowerment clubs have a positive impact on their studies and their lives (%) ........................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Appendix 7: Proportion of surveyed students who say teachers encourage them to participate more in class (%), by gender...........................................................Erreur ! Signet non défini.

Abstract

The present study, carried out in Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Sao Tomé & Principe and Chad, aims at generating knowledge on gender norms and the driving of sustainable behaviorial change in favor of girls' education. The methodology combines a qualitative and quantitative survey with as main targets pupils, parents, school and institutional stakeholders, technical and financial partners (TFPs), etc.

In Burkina Faso and Sao Tomé & Principe, the quantitative survey covered 100 pupils per country, with a majority of girls: 52.0% and 60.0% respectively. In addition, 200 parents were interviewed in both countries. In the Democratic Republic of Congo and Chad, 96 and 108 pupils respectively were surveyed, with the proportion of girls at 59.4% and 58.3%. In addition, 199 parents werequantitatively surveyedin both countries. Atotal of404pupils weresurveyed, 57.4% of them girls, while 399 parents were interviewed, 33.6% of them women. For the qualitative component, 45 semi-structured interviews and 6 life stories were conducted in each country. In addition, 24 focus groups were organized with students (girls and boys) and community players (APE/AME), with an average of 6 participants per group. A total of 1,151 people were interviewed, both quantitatively and qualitatively, in the four countries.

To measure the effects of social gender norms on girls' education, the analysis focused on three main indicators: (i) girls' access to and retention in school, (ii) the interaction between gender norms and girls' education, and (iii) factors influencing behavioral change within communities.

With regard to the first indicator, the results reveal improvements in access to education for girls from the surveyed households, with 63.4% of them all enrolled in school. However, there are disparities between countries. In Sao Tomé and Principe, 77.4% of all school-age girls in surveyed households are enrolled in school, compared with just 7.1% in the DRC. Despite progress, 11.0% of girls, including 24.4% in Chad, consider that their access to school has been difficult. Obstacles identified include families' lack of financial means (77.8%), the high cost of schooling (66.7%) and lack of family support (5.6%). Parents, especially women, are the main supporters of keeping girls in school. Indeed, with 93.2% of women and 89.2% of men expressing their support for girls to continue their studies up to higher education level.

As for the second factor related to interactions between gender norms and girls' education, the overall dynamic is positive, with 67.1% of men and 61.0% of women believing that their

communities promote gender equality at school. Nonetheless, challenges remain, as 22.8% of men and 13.6% of women consider that norms influence women's career choices. This perception is much more widespread in Chad, where it is shared by almost half the respondents. Furthermore, the existence of social norms unfavorable to girls' education is recognized by 14.6% of men and 22.0% of women. Among students, 19.0% of boys and 26.7% of girls felt that their community's beliefs hindered girls' schooling. When it comes to the effects of domesticchores,only8.0%ofboysand11.3%ofgirlsconsiderthattheyhindergirls'schooling. Similarly, 11.4% of boys and 14.3% of girls feel that domestic chores have a negative impact on their school performance.

Finally, with regard to the third indicator, it is worth noting that the positive perception of girls' right to education is high overall. Around nine out of ten students (91.1% of boys and 88.8% of girls) believe that girls and boys have the same rights of access to education. Although incentive-based teaching practices are well perceived by 91.3% of girls and 91.8% of boys, student participation in empowerment clubs remains low.Only6.0%of girls and10.1%of boys report taking part in such clubs in their schools. Yet girls' empowerment at school is overwhelmingly supported by parents, and is seen as a favorable factor for behavior change.

Ultimately, despite the progress noted in girls' access to education, challenges remain in terms of household poverty compared to the high cost of schooling, early marriage and pregnancy, lack of family support and overloaded domestic chores. In addition, the results underline the importance of taking cultural specificities into account in the design and implementation of education policies. Finally, it is essential to encourage the active participation of students, particularly girls, in empowerment initiatives.

Access and success for girls in and through education is one of the major challenges facing African countries in the 21ste century. Indeed, Africa's socio-economic transformation requires that girls and boys, women and men alike, be guaranteed an education that empowers them to become a new African citizen, with a view to the continent's sustainable development. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences have marked a decisive turning point in the evolution of education systems, mainly in Africa. As a result, UNICEF and the African Union Commission launched a wide-ranging consultation on the issue of "Transforming education in Africa". The resulting report calls for a rethinking of education. It highlights the progress made and points to persistent challenges, notably the issues of equity and quality. The issue of equity in education in Africa is complex and manifests itself, in different forms, in all areas of education systems.

Intermsofaccess, childrenstilldonothavethesameopportunitiestoaccesseducationservices, due to a lack of suitable infrastructure and safe school environments, especially for girls. In terms of quality, rural and remote areas are still disadvantaged in terms of materials, qualified staff, working hours and supervision, with repercussions on school performance. In terms of governance, discrimination and inequality persist in many areas, especially in rural areas, while few countries devote more than 20% of their budgets to education services.

As a result, many girls drop out of school due to early marriage or pregnancy, overloaded domestic chores and the absence of safety measures (against violence and harassment) or menstrual hygiene management (water, separate toilets, readmission of student mothers to school). In terms of school inclusion, many children with disabilities, nomads, refugees or from marginalized minorities are still out of school for lack of infrastructure, qualified staff or educational services adapted to their needs.

However,theright to education,particularly forgirls, is reaffirmedin international andregional commitments (MDGs 4 and 5, Education 2030, CESA 16-25, and its gender equality strategy, Agenda 2063). Countries such as Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sao Tomé and Principe and Chad have all included gender equality and the promotion of girls' success at school in their priority education sector plans. However, despite the priority given to girls' education and success in school in the policies and interventions put in place, the results obtained are still mixed. According to UNESCO's DME data, disparities persist in all African

countries, and under-schooling is more noticeable among girls than boys. In addition, the UIS indicates that girls make up 54% of the 97 million out-of-school children, adolescents and young people in sub-Saharan Africa. These gender disparities become more noticeable as one progresses through the education system, resulting in a drop in the number of girls progressing from primary to lower secondary school, and an even sharper drop in the number of girls progressing from lower to upper secondary school.

Inaddition, someexclusions (social,cultural, systemicandstructural)continueto act as barriers to girls' access, retention and success at school. Indeed, even today, school seems to be a socialization space that reproduces or reinforces social gender norms and gender inequalities. This state of affairs stems from the fact that education in general, and girls' education in particular, is not exclusively an economic, political or technical concern. It has a social, cultural and community dimension, which means that tackling it requires an ecosystemic approach and a synergy of actions based on evidence and in-depth analysis of education policies, with a view to bringing about sustainable behavioral change. It is in this perspective that this study on improving knowledge of gender norms is being carried out, with a view to better understanding resistance to change in order to promote gender equality and the success of girls at school.

The study was carried out in four countries: Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sao Tomé and Principe and Chad. It is divided into three main parts. The first part is devoted to a reminder of the objectives, a presentation of the methodology and the socio-demographic profile of the respondents. The second part presents the main results of the study in the four countries. Finally, the third part draws lessons from the study and proposes recommendations for greater gender equality and inclusion of girls in school.

1. Study objectives and methodology

This section presents the research objectives, data collection methodology and theoretical framework for analyzing the results.

1.1 Study objectives

The main aim of this research is to generate knowledge about the interaction between gender norms and the driving ofeffective change to enable girls to goto school, stay there and succeed. Specifically, and in the four countries, the study aims to:

- Generate evidence on gender norms and resistance to change,

- Analyze educational policies and propose relevant capacity-building strategies,

- Capitalize on innovations in gender equality and girls' success at school.

1.2 Methodology

This synthesis report is the culmination of a multi-stage process. To begin with, a literature review was carried out on the educational contexts and policies of the four countries, through an in-depth analysis of educational institutional frameworks, the issues and challenges of girls' education, and resistance to change. To this end, a researcher was recruited in each country. These researchers were trained by LARTES teams in qualitative and quantitative survey methods and gender-sensitive research methodology. Following the literature review, a research protocol was drawn up. It describes the different methodological approaches used, the sampling, the collection strategy and the stages of the survey. It also contains the qualitative and quantitative data collection tools consolidated from the results of the literature review. In addition, the data collection tools were pre-tested in each country, enabling us to compare them with the realities of different contexts. Finally, the research protocol was validated by a scientific committee made up of academics and specialists in gender and education.

In addition to the literature review, four national education system diagnostic workshops were organized. These four-day workshops mobilized 30 participants per country (directors/inspectors of education, gender units, planning departments, school heads, statistical institutes, PFTs) with a view to carrying out an in-depth analysis of national education systems and understanding the major challenges facing girls' education. To this end, a participatory diagnostic tool was developed and made available to stakeholders. This tool, comprising 200 evaluation indicators, is structured around five sections:

- Regulatory and legal framework: focused on the existence and application of laws relating to gender, girls' education and child protection,

- Architecture and financing: including indicators on education financing, gendersensitive budgeting, the level of implementation of educational programs and ministry staffing levels,

- Curricula and programs: assessing the extent to which curricula and programs take gender into account,

- School environment: analyzes the learning environment for pupils, with a focus on equipment, menstrual hygiene management, safety, etc.

- School results: highlighting student performance from a comparative perspective between boys and girls.

The results of these participatory diagnostic workshops were statistically analyzed. This made it possible to evaluate the school indicators of the education systems in the four countries. In addition, the participatory diagnosis will enable the development of a visualization tool on the situation of the education systems.

Finally, datacollectioncombinedquantitativeandqualitativeresearch.Onthequantitativeside, we administered questionnaires to 404 students and 399 parents in the four countries. The questionnaires were harmonized across all countries, with a view to collecting comparable data on the experiences of stakeholders, identifying specificities and drawing lessons. They cover relevant research questions and indicators on social gender norms in the family and school environment, girls' enrolment and success at school, and factors influencing behavioral change. In addition, a school collection sheet was used to gather data on key school indicators (school environment, gender-sensitive pedagogy, academic performance, etc.) from the schools where the study was conducted. Quantitative data were collected using the CommCare application. The data was then centralized and exported to Excel. Finally, processing and analysis were carried out on STATA 17, using flat and cross tabulations.

For the qualitative component, we carried out 180 semi-structured interviews, 24 focus group discussions and 18 life stories with a variety of target groups, including school and institutional players, technical and financial partners, parents, pupils and out-of-school girls. The qualitative corpora were recorded using dictaphones and transcribed in full onto Word. They were then corrected and processed on NVIVO 14 using a harmonized analysis grid. In this way, verbatims were produced on the most significant results with regard to the research objectives and questions. Ultimately, in each country, the surveys were carried out in urban and rural areas, with variations in the number of respondents depending on the targets1

1 For the number of people surveyed in each country, see the country reports available on the LARTES-IFAN website via the following link: https://lartes-ifan.org/fr/normes-sociales.

1.3 Theoretical framework for analysis

This study is a contribution to the search for effective mechanisms for sustainable behavior change in favor of girls' education and gender equality at school in terms of access, retention and success. Our theoretical framework is based on the theory of social change. It starts from thepremisethatinequalitiesbetweengirlsandboysintheschoolenvironmentresultfromsocial constructions inherent in gender roles assigned on the basis of biological differences. It highlights how girls and boys are socialized and influenced by the values and socio-cultural norms of their communities.

In this respect, our theory of change explores in depth the implications of social gender norms on girls' education. On the one hand, it underlines the interactions between gender and schooling, highlighting the specific challenges girls face in the quest for inclusive education (Sow, 1997). On the other hand, it points to the importance of girls' education as a driver of social change and deconstruction of gender stereotypes to promote gender equality in education (Adichie, 2012). Finally, it highlights the repercussions of education policies by highlighting the structural obstacles to equitable access to education for girls (Traoré, 2003) in the context of West Africa in particular.

Girls' education is therefore a fundamental lever for transforming established norms to promote a more equitable and inclusive educational environment. It involves the mobilization of a wide range of players: educational and institutional players, TFPs, families, parent-teacher associations, civil society, traditional chiefs, and so on. These actors, by virtue of their position and social roles, haveadefiniteimpact onchangingeducational practices (Fall andCissé,2017) and community behavior towards girls' education. They are capable of driving lasting change by deconstructing stigmatizing perceptions due to gender norms that devalue the role of women in society. They also have the power to eradicate attitudes that reproduce gender inequalities and promote inclusive educational practices through gender-sensitive pedagogy or recognition of women's role in improving living conditions. This recognition leads to a positive perception of girls' education and their empowerment through education. Ultimately, promoting gender equality and behavior change requires a cross-sectoral approach that takes into account the multidimensional nature of girls' education.

2. Socio-demographic profiles of respondents

The quantitative survey was carried out among students and parents. However, the survey sample varied by country and gender (Table 1). In Burkina Faso (52.0% girls) and Sao Tomé and Principe (60.0% girls), 100 pupils were surveyed. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Chad, 96 and 108 pupils respectively were surveyed, with 59.4% and 58.3% girls. This distribution shows a good representation of girls in the student sample.

As for the sample of parents, there were variations, with men being more representative. In Burkina Faso and Sao Tomé and Principe, we surveyed 100 parents, with 37.0% and 35.0% women respectively. In theDRC,97parents were surveyed,38% ofthemwerewomen.Finally, in Chad, we surveyed 102 parents, 24.5% of whom were women.

Overall, these analyses reflect a good distribution of the survey sample among students. The average age is around 15, with many more respondents in lower and upper secondary school (Erreur ! Source du renvoi introuvable.). A similar distribution was observed in the survey sample of pupils' parents. They are predominantly monogamously married (68.3% of men and 50.0% of women), live in rural areas (67.9% of men and 51.5% of women) and have an average age of around 45 (Erreur ! Source du renvoi introuvable.).

3. Analysis of national indicators for the education systems of the four countries

The analysis of education system indicators focused on the environmental situation and school results in the four countries. The data presented in this section come from the analysis of the results of the participatory diagnoses and deals with 2021-2022 school year. These diagnoses were based on statistical yearbooks and data from national agencies2 . Data for some indicators are not available for all countries. However, indications are provided in the country reports based on data collected in the surveyed schools.

3.1 School environment

The school environment data analysis for the four countries reveals significant variations between countries in terms of access to education, safety in the school environment, and protective measures for pupils, particularly girls (Table 2). Indeed, in terms of the distance pupils travel to school, the data reveal significant variations between countries. DRC is in a worryingsituation, with 70.0%ofits primary school pupils travelling morethan5km to school, while Burkina Faso and Chad each have a much lower proportion of 1.5%. Long distances remain a major challenge to access to education in DRC.

Burkina Faso has the highest number of non-formal training centers for teenagers, with 561 establishments. This number reflects the Burkinabe government's commitment to offering alternative educational opportunities to teenagers and young people who have been excluded or have not attended the conventional school system. Burkina Faso is followed by Chad, with a total of 290 non-formal training centers, while DRC has just 166 establishments, despite

2 The detailed results of the participatory diagnostic workshops are presented in the form of a visualization tool accessible online, on the LARTE-IFAN website, via the following link: https://lartes-ifan.org/fr/normes-sociales.

having a larger population than the other countries. Sao Tomé and Principe registers just 12 non-formal training centers for teenagers.

In terms of equipment and access to basic social services, there are variations from country to country. Nationally, Sao Tomé and Principe scores best, with 86.0% of schools electrified, 88.0% fenced, 87.0% with regular access to drinking water and 80.0% with separate toilets for girls and boys. Bycontrast, in BurkinaFaso, 34.4% ofschools are electrified, 22.3%arefenced, 69.3% have access to running water and 51.0% have separate toilets for girls and boys. In turn, DRC has a low proportion of schools (11.0%) with access to electricity. However, data show that 68.7% of the country's schools are fenced, 43.4% have regular access to drinking water and 65.0% have separate toilets for girls and boys. Finally, in the case of Chad, data on access to basic social services are not available for the 2021-2022 school year. This may hinder planning and decision-making to improve the educational environment for children, especially girls.

In addition, in our analysis of the school environment in the countries covered by the study, we focused on the phenomenon of safety and, above all, violence in the school environment. However, the diagnosis shows that very little data is collected or available in the countries. As a result, many cases of violence committed against pupils, particularly girls, go unnoticed or are not dealt with in the relevant countries. This can have major repercussions on girls' school retention and performance. This is only the case in Burkina Faso, where 2,806 cases of major violence against pupils have been recorded in schools for the 2021-2022 school year. For its part, and although data is not available for the relevant period, 221 cases of gender-based violence were reported in Chadian schools in the first half of 2023.

With regard to pregnancies in the junior high and high school cycles, the country recorded around 121 cases per 10,000 girls, compared with 164 cases actually recorded in Sao Tomé and Principe. Only Burkina Faso and the DRC have set up school readmission schemes for girls after pregnancy. However, these schemes are often not functional, and do not take in student mothers.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023), data from participatory diagnoses

These analyses reveal a series of challenges and disparities between countries in terms of the school environment. These disparities vary according to the priorities assigned to each component, and reflect the urgency or necessity of providing a safe environment to ensure the retention and success of girls and boys in school in general.

3.2. School results

National statistics on school results also reveal marked disparities between the four countries. In terms of girls' access to school, Burkina Faso has a gross primary school enrolment rate of 86.4% (

Table 3). In junior high/college and secondary/high school, these rates are 48.5% and just 20.0% respectively by 2021-2022. In Sao Tomé and Principe, national enrolment rates for girls are 98.0% at primary level, 95.0% at junior high and 69.0% at secondary/high school. In Chad, the net enrolment rate for girls is 44.6% at primary level, 38.7% at middle/college level and 32.6% at secondary/high school level. In the case of DRC, these statistics were not available at the time of the survey. In Burkina Faso and Chad, girls account for 53.9% and 25.9% respectively.

When it comes to keeping girls in school, Sao Tomé and Principe records the highest completion rates for girls at primary (92%), middle (98.0%) and high school (72.5%). Conversely, Chad has the lowest rates, with 40.2% in primary school, 13.3% in junior high and only 10.3% in high school. In Burkina Faso, the completion rate for girls is 66.5% at primary level, 36.1% at junior high and 17.3% at high school. In the DRC, the rate is 72.5% at primary level and 30.9% at middle and high school.

Similarly, Sao Tomé and Principe has the highest transition rate for girls between primary and secondary school, at 98.0%. This is followed by the DRC, where the transition rate for girls from primary to secondary school is 81.0%. In Chad, the rate drops from 68.4% between primary and junior high school to 58.2% between junior high school and high school. In Burkina Faso, the transition rate for girls fell by almost half between cycles over the same period. In fact, it dropped from 51.5% from primary to junior high to 27.8% from junior high to high school3

Finally, when it comes to girls' success at school, there are also disparities between the four countries and according to level of education. At primary level, Sao Tomé et Principe (97.0%) and Chad (68.5%) have the highest success rates for girls in 2021-2022. They are followed by Burkina Faso with 61.8%, while the DRC comes last with 43.0%. A similar trend can be seen at secondary school level, with a girls' school success rate of 83.0% in Sao Tomé and Principe, 82.2% in Chad, 41.6% in the DRC and 37.9% in Burkina Faso. At high school, the situation is more or less reversed, with Chad recording the highest success rate for girls at 83.6%. This is followed by Sao Tomé and Principe (70.0%), Burkina (43.2%) and the DRC (40.5%).

3 National transition rates from middle school to high school for Sao Tomé & Principe and the DRC were not available at the time of diagnosis and data collection.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023), data from participatory diagnoses

Analyses of school results show disparities between countries and levels of education. In fact, the data show that girls' school indicators fall as one progresses through the education systems of the different countries. However, Sao Tomé and Principe has the best indicators in terms of girls' access to and retention in school. However, despite Chad recording the lowest rates for school access, completion and transition, the country boasts high rates of school success for girls. In other words, when they do access school, Chadian girls perform very well. Thus, the main challenge for girls' education in Chad lies in their access to school, whereas in the other three countries, the need seems to lie mainly in maintaining (in Burkina Faso and the DRC in

particular) and improving performance. In addition, the absence of national data on some indicators such as enrolment or school transition rates can pose a major challenge to the overall assessment of the student retention situation and understanding of the factors contributing to school drop-out.

4. School indicators for surveyed schools

The data presented in this section come from the field survey. They were collected using the school data collection form administered to all the schools where the study was carried out. The focus is on three indicators: teaching staff, the school-based gender-based violence management system (GBVMS) and the academic results of the schools surveyed.

4.1. Population and teaching staff

Across the four countries, 46 schools were surveyed, including 13 elementary schools and 33 middle and secondary schools. However, the number of classrooms varies significantly from one school to another. Sao Tomé and Principe had the best results, with a total of 13 classrooms per school, while Burkina Faso had the lowest average, with just 7 classrooms (Table 4). These figures could reflect variations in elementary school capacity between these countries. Moreover, we note that the number of pupils per classroom varies significantly, with Sao Tomé & Principe offering a more individualized experience with an average of 33 pupils per classroom, while Burkina Faso and Chad have higher averages (77 and 67 respectively). In addition, Sao Tomé and Principe and the DRC stand out for their high percentages of girls in schools (47% to 52%). In terms of teaching staff, the DRC has the lowest average (13 teachers, 46% of whom are women), while Sao Tomé & Principe has the highest number of teachers, with 16 teachers, the majority of whom are women (69%). In Chad, only 26% of elementary school teachers surveyed are women. Finally, although the average teacher/pedagogical class ratio is balanced in most countries, Burkina Faso has a ratio of 2.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

In terms of middle and secondary education, Sao Tomé & Principe again stands out with a high average number of classrooms (18), suggesting potential investment in secondary education (Table 4). It is followed by the DRC (15 classrooms) and Burkina Faso (13 classrooms), while Chad has the lowest average with 8 classrooms. However, the average number of pupils per classroom is significantly higher in Burkina (64), followed by Chad (54) and DRC (50). Unlike at primary level, the average number of female teachers at junior and secondary level is low overall. Thus, out of a total of 32 teachers in the schools surveyed in Burkina, only 25% are women. In the DRC, women account for 23% of the total number of teachers in the schools surveyed at middle and high school level, while in Chad, the proportion is just 12% for a total of 20 teachers. These data underline the variations between countries in terms of infrastructure,

studentdemographicsandteachingstaff.Theyhighlightthedifferencesineducationalpriorities and challenges specific to each country.

4.2. GBVGMS management system

Analysis of the management of Gender-Based Violence in Schools (GBVMS) reveals significant variations in the efforts made by the schools surveyed in the four countries to deal with it. At primary level, the schools surveyed in Burkina Faso reported no pregnancies recorded during the 2021-2022 school year, while in the schools surveyed in Chad, the number of pregnancies recorded was 6. Furthermore, none of the elementary school surveyed in the four countries had set up a functional readmission scheme for girls after pregnancy, suggesting a need for improvement in this support measure. This state of affairs reflects the lack of data on cases of violence perpetrated against pupils in the school environment.

In terms of GBV alert and reporting systems, Burkina Faso stands out, with 50.0% of schools having a functional system, while the DRC and Sao Tomé & Principe have none. Similarly, with regard to the integration of gender into school curricula, Burkina Faso leads the way with 100.0%ofprimaryschoolshavingrevisedcurriculaintegratinggender;asituationthatcontrasts with those of the DRC and Sao Tomé and Principe, as shown in Table 5. Nevertheless, DRC stands out with a high proportion (61.5%) of teachers trained in the use of gender-inclusive textbooks in schools, while Burkina Faso has a more modest proportion (21.4%).

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Still following the data in Table 5 ; 40.0% of junior and secondary schools surveyed in Burkina Faso have a functional readmission system for girls after pregnancy. By contrast, DRC (11.1%) and Chad (25.0%) have relatively low proportions, while in Sao Tomé and Principe, none of the schools has such a system. With regard to the existence of GBVMS alert or reporting systems, Chadhas thehighest proportion (37.5%)ofsurveyedschools with a functional system, followed by the DRC (33.3%), Burkina Faso (20.0%) and Sao Tomé et Principe (0.0%). As for the integration of gender into school curricula, Chad stands out with a high proportion (75.0%) of schools surveyed in the junior and secondary cycles. Conversely, Sao Tomé and Principe

boasts the lowest proportion of schools surveyed in junior and senior high school with revised curricula incorporating gender. Finally, 93.3% of teachers surveyed in the DRC are trained in the use of gender-integrated teaching manuals. In Chad, the proportion is 26.3%, compared with 0.0% in Burkina Faso.

These results highlight significant differences between countries when it comes to managing GBV in schools. Indeed, while Sao Tomé and Principe has the best results in terms of infrastructure and the number of teachers and pupils, its scores are alarming when it comes to managing gender-based violence in the schools surveyed. Conversely, Chad appears to be making efforts to provide a safe environment for girls and boys, despite challenges in terms of infrastructure. These results highlight the importance of strengthening protection, awareness and gender mainstreaming measures to ensure a safer and more equitable educational environment.

4.2 School results

In terms of school results, the study reveals significant inequalities, both between countries and within different levels of education. At primary school level, the schools surveyed in Sao Tomé and Principe had a completion rate of between 95.9% and 99.9%, while Chad recorded the lowest rate, between 40% and 60% (Table 6). Similarly, completion rates for girls vary, with Sao Tome and Principe recording the highest rate (96.8% to 97.0%), followed by Burkina Faso (85.0%), the DRC (48% to 53%), and finally Chad (30% to 33%). In terms of exam pass rates, the primary schools surveyed in the DRC stood out for their high rates, varying between 92% and 95% (including 39% and 51% for girls). Burkina Faso and Sao Tomé and Principe also show encouraging pass rates, while Chad has more modest results. Drop-out rates vary considerably from country to country. The schools surveyed in the DRC (1% to 3%) and Sao Tomé & Principe (2.9% to 3.5%) have relatively low rates. However, DRC has the highest dropout rate among girls at primary level, ranging from 27% to 55%.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

At middle and high school level, completion rates vary considerably from country to country, with a fairly wide range for the schools studied in Burkina Faso (30% to 95%) and Sao Tomé and Principe (61.5% to 90%), as shown again in Table 6. DRC and Chad as for them, show more homogeneous results. Examination pass rates also vary, with DRC standing out for its

high rates (70% to 95%), while the other countries show a greater diversity of results: 30% to 60% in Burkina, 52% to 81.5% in Sao Tomé and Principe and 63% to 95% in Chad. Finally, in terms of drop-out rates, the schools studied in Burkina Faso and Sao Tomé & Principe had moderate rates, while DRC and Chad had the highest.

All in all, the above analyses give an overall picture of the environment in the schools where thestudywas carriedout. Theyshowsignificantvariationsintermsofpopulation,gender-based violence management systems and school results. These variations are broadly attributable to factors such as education policies, access to education, quality of teaching and the specific challenges faced by each country in promoting girls' education and gender equality.

5. Main results of the study

This section is devoted to presenting the key findings of the study in the four countries. The focus is on girls' access, retention and performance in school, the interaction between gender norms and girls' education, and the factors that promote and impede behavioral change.

5.1. Girls' access to and retention in school

This section looks at two key indicators. These are girls' access to school and their retention and performance in school.

5.1.1. Girls' access to school

The analysis of girls' access to school in the four countries was based on three key indicators. These include the enrolment of girls from the households of the pupils surveyed in school, pupils' assessment of girls' access to school, and difficulties in accessing school according to pupils.

Overall, girls from the surveyed households have significant access to school. Overall, 63.4% of girls from surveyed households are enrolled in school (Chart 2). This proportion is followed by households in which three quarters of girls are enrolled at school, with 18.8%. In addition, almost one in ten households of pupils surveyed (9.7%) have more than three-quarters of their daughters enrolled in school. However, it should be noted that 5.4% of households have less than half their daughters enrolled in school, while 2.7% have no girls at all. These proportions vary considerably from country to country.

In the DRC, the proportion of households where all girls are enrolled in school is just 7.1%; 28.6% have more than three-quarters of girls enrolled in school, while 64.3% have less than three-quarters of girls enrolled. These statistics reflect the persistence of the challenge of girls' access to school in the Congolese context, and confirm the national trend highlighted in the participatory diagnosis data. Conversely, in Sao Tomé and Principe, 77.4% of surveyed households have all their daughters in school. This is followed by the proportion with 50-75% of girls in school, at just 8.6%. It should be noted, however, that 4.3% of Santomean households surveyed had no girls at all in school. Finally, in Chad, 63.4% of households have all their daughters enrolled in school; 12.7% have more than three quarters and 22.8% have between half and three quarters of girls enrolled, as shown in the chart below.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Despite the differences noted in terms of the proportions of girls attending school in surveyed households, the study shows that access for girls is becoming less and less difficult. Indeed, 89.0% of girls in all countries surveyed said their access to school was easy, compared with 88.9% of boys (Chart 3). However, a sizeable proportion of girls (11.0%) say their access to school is difficult. Sao Tomé and Principe (97.5%) and Burkina Faso (95.2%) respectively had the highest proportions of girls who said their access to school was easy. Paradoxically, Chad (24.4%) and the DRC (11.1%) have the highest proportions of girls who feel their access to school has been difficult. Overall, this situation shows that, despite the progress made, girls' access to school still faces constraints, particularly in Chad and the DRC. However, it should

be noted that in the DRC, the proportion of boys (27.5%) who consider that their access to school has been difficult is higher than that of girls.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Anumberoffactorsareidentifiedbystudents as hinderinggirls' access to school. Theseinclude financial barriers; lack of family support and the long distances students have to travel to get to school. In all four countries, lack of financial means (77.8%) and the high cost of schooling (66.7%) are the main factors making it difficult for girls to attend school (Chart 4). Long distances (5.6%) and parental or family disapproval of girls' schooling (5.6%) were also mentioned by surveyed students. These trends vary slightly between countries.

In Burkina Faso, the high cost of schooling (50.0%), insufficient financial means (50.0%) and parental disapproval (50%) remain the main obstacles to girls' access to school. However, a significant proportion of students (25%) emphasized the barrier posed by the existence of a family member unfavorable to girls' education. In addition, during the workshop to complete the participatory diagnostic tool in Burkina, the closure of schools due to the political and security crisis was mentionedas afactormaking it difficult forgirls to access andstayin school. As for the DRC, 64.3% of the students surveyed mentioned lack of financial resources as the

main reason for girls' inability to attend school. However, 14.3% mentioned difficulties related to the high cost of schooling and disagreement with family members.

On the other hand, in Sao Tomé and Principe, although lack of financial means remains the main obstacle (66.7%), one in three students surveyed (33.3%) stressed that the problem of documentation makes it difficult for girls to attend school. Similarly, community disagreement about girls' schooling (33.3%) and long distances (33.3%) are also mentioned as obstacles. Finally,inChad,thehighcostofschooling(50.0%)andinsufficientfinancialresources(50.0%) are identified as the main obstacles to girls' access to school. It should also be noted that in the Chadian context, one pupil in four (25%) believes that early or child marriages prevent girls from gaining easy access to school. Overall, these analyses show that financial constraints and the low value placed on girls' education by the community (attitudes of parents or an unfavorable community member) are major challenges to girls' access to school.

*Multiple-choice question

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

However, beyond the cost of schooling and the financial difficulties of households highlighted in the quantitative survey, the comments of stakeholders reveal that social gender norms and the gendered distribution of social roles are not always favorable to girls' education. Indeed, early marriages and the low importance attached to girls' education mean that they are often not

enrolled in school, or are forced to abandon their studies to look after their households, as we can see from the interview extracts below.

"The causes that prevent girls from going to school are early marriage and parents, who think that a girl's place is in the kitchen. Early pregnancy also prevents girls from going to school. Parents think girls should stay at home and cook, not attend school" (student, girl, Chad).

"Our parents think that a girl's place is at home. She has to stay at home to learn how to prepare [...]. There are others who leave girls at home too because they want to teach them how to look after a family" (student, girl, Burkina Faso).

Parents, especially women who have been victims of the effects of gender norms, experience non-enrolment or dropping out of school as a difficult situation that has had a negative impact on theircareerpath. This situationis furthercomplicatedin somecountries bythelackofschool infrastructure, particularly in rural areas where girls have to travel long distances to study. This has a negative impact on school performance and encourages repeated delays and/or absenteeism, which usually leads to dropping out. And yet, when they don't study, girls are confined to performing domestic chores and looking after the household, with no possibility of taking up jobs that might empower them, as we can see from the following comments.

"We don't send girls to school. Why does the girls go to school? School is for boys and a Sara (southern people) thing. And then there are the schools that are too far away. Since 2021, we've even been looking for a school, but we can't find one. It's good to go to school, but now it's difficult when you get older and have children. If I get the chance, I'll go and learn the alphabet from A-Z. The fact that boys attended school and I didn't go hurts me" (woman, parent, Chad).

However, realities differ from one country to another. In Sao Tomé and Principe, for example, girls' access to school is seen as being more a matter of parents' and communities' willingness and ability to bear the costs of educating their children. This is easy to understand when you consider that, according to the results of the literature review on the four countries, Sao Tomé and Principe has the highest girls' enrolment rates (LARTES, 2023). This also reflects the efforts made by Sao Tome authorities to improve the school map and reduce the long distances travelled by pupils, especially girls, to study. As a result, gender norms are no longer seen as a constraint or obstacle to girls' access to school, as emphasized by a parent in the interview extract below.

"In my opinion, the community environment or cultural practices have no effect on girls' schooling. This used to be the case; there were several factors that constituted a barrier to girls' schooling, including the distance between schools and places of residence, the habits of our grandparents, and the devaluation of women's social status. In the past, because of the distances involved, it was necessary to have means to pay for school transportation, and for this reason, many parents refused to enroll their daughters in school. Nowadays, we have schools very close by, at all levels, from kindergarten to high school, so there are no factors or barriers preventing young people, girls and boys alike, from studying" (parent, woman, Sao Tomé).

In all cases, the study data show that girls face greater difficulties than boys in gaining access to school. This fact, which reflects the persistence of gender inequalities in access to education, is highlightedin Chart5.Indeed, ofall parents surveyedin the fourcountries, 68.7%ofwomen and 59.3% of men felt that girls had more difficulty accessing school than boys. However, these proportions vary significantly from country to country. Chad has the highest proportion of parents (88.0% of women and 85.7% of men) who say that girls have more difficulty accessing school than boys. Burkina Faso (83.8% of women and 63.5% of men) and the DRC (70.3% of women and 60.0% of men) share this view. Sao Tomé and Principe has the lowest proportion of surveyed parents who consider girls' access to school to be more difficult.

Source:

In addition to the lack of financial resources mentioned above and echoed by some of the players, it should be noted that girls living in single-parent families (due to divorce or the death

of one of the parents) seem to face constraints that make their schooling more difficult. They are generally exposed to the risks of early or forced marriage, and to the overload of domestic chores that can act as a barrier to their schooling or the pursuit of their studies, as highlighted in the interview extract below. As might be expected, this situation is generally more marked in countries such as Chad, due to insecurity and the presence of jihadist groups.

"Poverty prevents girls from going to school. The death of parents also has an effect on girls' schooling. In these circumstances, no one supports them. If the mother doesn't have the means to send the children to school, she sends the boys to school and the girls stay at home to help with the chores. Girls work a lot at home on domestic chores. As long as they don't finish their chores, they can't go to school" (Parent, Chad).

Quite often, the situation described above is compounded by difficult living conditions. This is the case for some girls, particularly in the DRC, as described by this parent. Girls in these situations are much more likely to drop out of school, marry early or engage in incomegenerating activities to support their parents.

"I can list one or two difficulties that girls face compared to boys. First of all, their parents' lack of means is really the first factor. And the second factor can be housework, although girls are sent to school, but in relation to their homes, in their small families, it's as if girls are caught up a lot in housework" (DRC parents).

Finally, analysis of girls' enrolment in the schools surveyed reveals significant variations. In fact, the data reveal that the problem of girls' access to school is less acute in Sao Tomé and Principe and Burkina Faso than in Chad and the DRC, where challenges persist, particularly due to poverty and the low value placed on girls' education by communities. This state of affairs is also explained by distorted perceptions of the division of social roles, assigning to girls the responsibilities linked to motherhood and household management, and considering boys as the heir and provider of family resources.

5.1.2. Student retention and performance

Keeping girls in school and ensuring their success is a priority for all countries. This is reflected in the definition of national strategies to promote girls' education and the installation of gender units in ministries of education. However, the study data show that, despite the overall positive trends, the situations in terms of girls' school retention and performance differ between the four countries where the survey was carried out. More specifically, the efforts made by parents to keep girls in school are not the same.

Overall, the majority of parents surveyed, 89.2% of whom were men and 93.2% women, said they supported their daughters' education up to tertiary level, as shown in Chart 6. Thus, women seem to be more inclined to support their daughters' retention and success in school. These proportions are generally high in all four countries.

In the DRC, all parents surveyed (100% of both men and women) said they supported their daughters in continuing their studies up to higher education level. In Burkina Faso, almost all parents surveyed (100% of women and 96.4% of men) encourage their daughters to continue their studies up to higher education level, while in Sao Tomé and Principe these proportions deal with 98.5% of men and 97.1% of women. Finally, Chad records the lowest proportions of parents (67.4% of men and 76.9% of women) encouraging their daughters to go on to higher education.

Source:

In the view of some stakeholders, the academic performance of pupils, especially girls, does not depend exclusively on parental incentives or cultural barriers. For them, girls' performance at school is linked on the one hand to their parents' financial ability to cover school fees, and on the other to their family learning environment. In other words, parental sensitivity,

awareness of the importance of girls' education and family support are essential to maintaining and improving girls' school performance.

"In my opinion, it's not a question of cultural beliefs or practices, but rather of the type of family environment in which girls or boys are inserted. In my opinion, it's not a question of beliefs or cultural practices, but rather the type of family environment in which the girls or boys are inserted. If you're in a family where you've never had support from your parents or relatives, it's not going to cause you to drop out of school, but it can weaken your performance" (parent, woman, Sao Tomé and Principe).

Moreover, the retention and success of girls in school has a personal dimension, making them the main players in their own education. This calls for a willingness and awareness on the part of girls of the importance of their success in school, with a view to their empowerment and active participation in the development of their communities.

"If the girl forces herself and works hard at school and manages to graduate and earns a job, she will be able to look after herself, her children and also help her parents" (Woman, parent, Burkina).

"We're here just to raise awareness among our daughters. Every time there are gatherings of parents at school to raise awareness of the benefits of education in general, because we live in a world where it's really important to get everyone moving forward and to help girls get ahead in their studies" (DRC parents).

In the same vein, the perceptions of surveyed parents of the academic performance of girls and boys at school differ from country to country. Overall, 32.8% of parents maintain that girls perform better at school, against 30.1% who say the opposite, while 37.1% say there is no difference (Chart 7). In Sao Tomé and Principe, two out of six parents surveyed (40.0%) said that girls performed better at school, compared with 20.6% who said boys did. A similar trend is noted in the DRC, with more parents maintaining that girls (27.8%) do better at school than boys (20.6%). Conversely, in Burkina Faso, 31.0% of parents believe that girls perform better, while 35.0% consider that boys do better. The same is true in Chad, where 37.2% of parents say that boys perform better at school, compared with 32.4% who say it's girls.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

A number of factors can explain students' performance at school. One of these is the amount of timedevotedtolearningoutsidetheclassroom. However,whenitcomestothisindicator,trends vary very little, as shown in Table 7. The overall data show that boys devote slightly more time (2 hours) than girls (1.9 hours) to learning outside the classroom. In the DRC, the average number of hours spent studying outside the classroom is 1.8 for boys and 2.0 for girls. In Sao Tomé and Principe, boys spend an average of 1.5 hours on learning outside the classroom, compared with 1.6 hours for girls. In Chad, the trend is the opposite, with boys spending 2.7 hours on learning outside the classroom, compared with 2.2 hours.

Looking at the data in Chart 6 and Table 4 below, we can see a causal relationship between students' academic performance and the amount of learning time spent outside the classroom, particularly for girls. Thus, in countries such as Sao Tomé and Principe and DRC, where girls spend more time learning outside school hours than boys, they are more likely to perform better at school. Paradoxically, in countries where girls devote less time to learning outside school hours, they are thought to perform less well at school, as is the case in Chad. This state of affairs highlights the need for parents to set aside more time for girls to learn at home, in the same way as boys, in order to promote their retention in school and improve their academic performance.

At the other end of the scale, a variety of reasons were mentioned as being unfavorable to girls' retention and success at school. Among all thestudents surveyed,57.9% felt thatearlymarriage was the main factor preventing girls from staying in school. This proportion is respectively followed by insufficient financial means (21.7%) and family support (18.4%), as shown in Chart 8. However, it should be noted that the factors mentioned are not the same from one country to another.

In the DRC, gender-based violence in schools (10.4%), early marriage and pregnancy (9.4%) and lack of financial resources (8.3%) were identified as the main factors preventing girls from staying in school. In Sao Tomé and Principe, early marriage (94.0%), lack of family support (31.0%) and insufficient financial means (25.0%) are mentioned in order of importance as obstacles to keeping girls in school. In Chad, early marriage (67.6%) was the main factor, followed by lack of financial means (30.6%) and lack of family support (16.7%). These results reveal that the pressures of marriage and early motherhood, household financial constraints and insufficient family support are the major challenges to keeping girls in school. In the case of the DRC, this is compounded by the problem of gender-based violence in the school environment.

*Multiple-choice question

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

In the same perspective, early marriage and its corollaries, notably teenage pregnancy, are mentioned as one of the main factors preventing girls from staying in school. Indeed, when they marry early, girls are forced to combine their studies with their domestic responsibilities and household management. In cases where pregnancy is contracted outside marriage, girls are often rejected by their community. They are therefore forced to work to meet their immediate needs, to the detriment of their studies.

"There's no doubt about it, the first factor is early pregnancy. When a girl gets pregnant, everything becomes complicated and studies are always put aside. I have a friend who got pregnant, she was kicked out of her parents' house, she was forced to give up her studies to start a married life and also to work. As far as school failure is concerned, I can say that it's more associated with family problems, family breakdown or lack of support. Normally, 90% of girls drop out of school because of early pregnancy" (student, girl, Sao Tomé and Principe).

In addition to the effects on their retention and performance at school, early marriage poses a health risk forgirls, particularly minors.Also, theoverloadofdomestic chores leads to repeated lateness and/or absences, with direct consequences on school performance. This state of affairs

is accompanied by a low value placed on girls' education, as can be seen from the comments below.

"If she marries young, she can lose her life. It's a loss for the family and the country. I want to see an end to early marriage. For some mothers, if the daughter doesn't finish work, she doesn't go to school. If time passes, she's absent or she's always late. She doesn't have time to study. If she's even studying, mom sends her, and she has no right to refuse. Mothers often say that as a girl, what can school give you? You're going to get married and your husband will take care of you. I haven't studied myself" (student, girl, Chad).

"I'd like to start by saying that at home, in my family, Dad favors my older brother, with the little he earns. Even at school, there are teachers who criticize us, saying that you girls will end up getting married, and besides, a woman doesn't run a country. So all you have to do afterwards is look for a good husband" (girl student, DRC).

An analysis of the indicators on girls' access to and retention in school, and an assessment of their performance at school, reveals that the situations and realities in different countries are not the same. More specifically, the data show that countries where girls are thought to have more difficulty accessing school, and where they spend less time learning at home, are also those where they are considered to perform less well at school than boys. Conversely, in countries where women are considered to have easy access to school and devote more time to study outside the classroom, their academic performance is thought to be better than that of boys. In other words, beyond the economic factor (insufficient financial means), geographical obstacles (long distance) and barriers linked to gender-based violence, the home learning environment and family support play a decisive role in promoting girls' education and improving their school performance.

5.2. Gender norms and girls' education

This section is devoted to analyzing the interactions between social gender norms and girls' education in the four countries where the study was carried out. First, the focus is on actors' perceptions of gender norms. Secondly, the analysis focuses on interactions in the school environment, with an emphasis on the feelings of pupils, particularly girls, in the classroom.

5.2.1. Perceptions of gender norms

Theanalysisofperceptionsofgendernormsbeganwithanassessmentoftheirimpactongender equality in schools. In this respect, the study data reveal a generally positive dynamic, with relatively wide variations between countries (Erreur ! Source du renvoi introuvable.). Indeed, among all parents surveyed, 67.1% of men and 61.0% of women believe that social norms in their community are favorable to gender equality at school. These proportions are particularly high in theDRC,where100.0%ofwomenand84.2%ofmenshare this assessment.

In Burkina Faso, 89.3% of men and women (66.7%) said their community's social norms favored gender equality at school. Proportionally, Burkina is followed by Chad, where the shares of men and women believing that their community's gender norms are conducive to gender equality at school are 67.4% and 69.2% respectively. Paradoxically, Sao Tomé and Principe recorded the lowest proportions sharing this opinion. In fact, 52.3% of men and 54.3% of women in Sao Tomé and Principe maintain that their community's gender norms are favorable to gender equality at school, as illustrated in the chart below.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

A number of factors can explain students' performance at school. One of these is the amount of timedevotedtolearningoutsidetheclassroom. However,whenitcomestothisindicator,trends vary very little, as shown in Chart7. The overall data show that boys devote slightly more time (2 hours) than girls (1.9 hours) to learning outside the classroom. In the DRC, the average number of hours spent studying outside the classroom is 1.8 for boys and 2.0 for girls. In Sao Tomé and Principe, boys spend an average of 1.5 hours on learning outside the classroom, compared with 1.6 hours for girls. In Chad, the trend is the opposite, with boys spending 2.7 hours on learning outside the classroom, compared with 2.2 hours.

Looking at the data in chart 6 and Table 4 below, we can see a causal relationship between students' academic performance and the amount of learning time spent outside the classroom, particularly for girls. Thus, in countries such as Sao Tomé and Principe and the DRC, where girls spend more time learning outside school hours than boys, they are more likely to perform better at school. Paradoxically, in countries where girls devote less time to learning outside school hours, they are thought to perform less well at school, as is the case in Chad. This state of affairs highlights the need for parents to set aside more time for girls to learn at home, in the

same way as boys, in order to promote their retention in school and improve their academic performance.

At the other end of the scale, a variety of reasons were cited as being unfavorable to girls' retention and success at school. Among all the surveyed students, 57.9% felt thatearlymarriage was the main factor preventing girls from staying in school. This proportion is respectively followed by insufficient financial means (21.7%) and family support (18.4%), as shown in Chart 8. However, it should be noted that the factors cited are not the same from one country to another.

In the DRC, gender-based violence in schools (10.4%), early marriage and pregnancy (9.4%) and lack of financial resources (8.3%) were identified as the main factors preventing girls from staying in school. In Sao Tomé and Principe, early marriage (94.0%), lack of family support (31.0%) and insufficient financial means (25.0%) are cited in order of importance as obstacles to keeping girls in school. In Chad, early marriage (67.6%) was the main factor, followed by lack of financial means (30.6%) and lack of family support (16.7%). These results reveal that the pressures of marriage and early motherhood, household financial constraints and insufficient family support are the major challenges to keeping girls in school. In the case of the DRC, this is compounded by the problem of gender-based violence in the school environment.

*Multiple-choice question

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

In the same perspective, early marriage and its corollaries, notably teenage pregnancy, are mentioned as one of the main factors preventing girls from staying in school. Indeed, when they marry early, girls are forced to combine their studies with their domestic responsibilities and household management. In cases where pregnancy is contracted outside marriage, girls are often rejected by their community. They are therefore forced to work to meet their immediate needs, to the detriment of their studies.

"There's no doubt about it, the first factor is early pregnancy. When a girl gets pregnant, everything becomes complicated and studies are always put aside. I have a friend who got pregnant, she was kicked out of her parents' house, she was forced to give up her studies to start a married life and also to work. As far as school failure is concerned, I can say that it's more associated with family problems, family breakdown or lack of support. Normally, 90% of girls drop out of school because of early pregnancy" (student, girl, Sao Tomé and Principe).

In addition to the effects on their retention and performance at school, early marriage poses a health risk forgirls, particularly minors.Also, theoverloadofdomestic chores leads to repeated lateness and/or absences, with direct consequences on school performance. This state of affairs

is accompanied by a low value placed on girls' education, as can be seen from the comments below.

"If she marries young, she can lose her life. It's a loss for the family and the country. I want to see an end to early marriage. For some mothers, if the daughter doesn't finish work, she doesn't go to school. If time passes, she's absent or she's always late. She doesn't have time to study. If she's even studying, mom sends her, and she has no right to refuse. Mothers often say that as a girl, what can school give you? You're going to get married and your husband will take care of you. I haven't studied myself" (student, girl, Chad).

"I'd like to start by saying that at home, in my family, Dad favors my older brother, with the little he earns. Even at school, there are teachers who criticize us, saying that you girls will end up getting married, and besides, a woman doesn't run a country. So, all you have to do afterwards is look for a good husband" (girl student, DRC).

An analysis of the indicators on girls' access to and retention in school, and an assessment of their performance at school, reveals that the situations and realities in different countries are not the same. More specifically, the data show that countries where girls are thought to have more difficulty accessing school, and where they spend less time learning at home, are also those where they are considered to perform less well at school than boys. Conversely, in countries where women are considered to have easy access to school and devote more time to study outsidetheclassroom, theiracademicperformanceis judgedto bebetterthanthatofboys. In other words, beyond the economic factor (insufficient financial means), geographical obstacles (long distance) and barriers linked to gender-based violence, the home learning environment and family support play a decisive role in promoting girls' education and improving their school performance.

5.2. Gender norms and girls' education

This section is devoted to analyzing the interactions between social gender norms and girls' education in the four countries where the study was carried out. First, the focus is on actors' perceptions of gender norms. Secondly, the analysis focuses on interactions in the school environment, with an emphasis on the feelings of pupils, particularly girls, in the classroom.

5.2.1. Perceptions of gender norms

Theanalysisofperceptionsofgendernormsbeganwithanassessmentoftheirimpactongender equality in schools. In this respect, the study data reveal a generally positive dynamic, with relatively wide variations between countries (Chart 9). Indeed, among all parents surveyed, 67.1% of men and 61.0% of women believe that social norms in their community are favorable to gender equality at school. These proportions are particularly high in the DRC, where 100.0% of women and 84.2% of men share this assessment.

In Burkina Faso, 89.3% of men and women (66.7%) said their community's social norms favored gender equality at school. Proportionally, Burkina is followed by Chad, where the shares of men and women believing that their community's gender norms are conducive to gender equality at school are 67.4% and 69.2% respectively. Paradoxically, Sao Tomé et Principe recorded the lowest proportions sharing this opinion. In fact, 52.3% of men and 54.3% of women in Sao Tomé and Principe maintain that their community's gender norms are favorable to gender equality at school, as illustrated in the figure below.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

These analyses indicate that gender norms are more likely to promote gender equality and women's empowerment in the DRC and Burkina Faso. However, these perceptions need to be put into perspective, as in countries such as the DRC, girls still face a number of difficulties in

accessing and remaining in school, as mentioned above. Nevertheless, this is a positive and encouraging dynamic that promotes gender equality. Indeed, perceptions of the positive effects of social gender norms on gender equality at school reflect a dynamic of change within communities. This dynamic is largely due to the empowerment of educated women, who increasingly occupy positions of responsibility hitherto reserved for men.

"In the past, cultural values were a factor that prevented girls from succeeding at school, as they were simply reduced to organizing domestic work and family affairs. But nowadays, this kind of thinking or mentality is no longer verified. To illustrate my opinion, I can say that nowadays, wherever you go, you're going to meet women, in all public and private sectors, I have to congratulate that. So, I think it shows that cultural beliefs and values encourage and support girls' schooling. If our cultural practices had negative effects on girls' schooling, as is the case in many African countries, we wouldn't have seen girls and women occupying important positions as we see them today" (parent, Sao Tomé and Principe).

This change is all the more encouraging in that it is an ongoing process. It is the result of a growing awareness of the importance of girls' education and their role in improving living conditions in their communities.

"In recent years, there has been a tendency to put girls and boys on an equal footing. A girl who succeeds at school can help her parents better than a boy. It used to be ignorance, but today there's a clear evolution. At some point, some parents regret not sending their daughters to school. Girls take better care of their parents if they do well at school" (parent, Chad).

Nevertheless, challenges still persist, highlighting the influence of gender norms on the career paths and aspirations of women/girls in particular. For example, of all parents surveyed, 22.8% of men and 13.6% of women said that gender norms influenced their career choices and aspirations (Chart 10). However, these proportions vary considerably from country to country. They are highest in Chad, where more than two out of five men (45.7%) and almost one out of two women (46.2%) say that gender norms have an impact on their career choices.

Chad is followed by Sao Tomé et Principe, with 16.9% of men and 5.7% of women believing that their community's gender norms influence women's career choices. In the DRC, these proportions are 15.8% for men and 0.0% for women. Finally, Burkina Faso records the lowest proportions, with only 3.6% of men believing that gender norms have an influence on women's professional careers. Finally, it's worth noting that men are more likely to perceive the effects

of social gender norms on women's careers. This recognition reflects the challenges to women's empowerment posed by socio-cultural barriers, particularly in Chad.

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

Source: FAWE and LARTES-IFAN (2023)

The significant effect of social gender norms on women's empowerment and professional careers in Chad is confirmed by the comments of stakeholders. In Chad, gender norms reproduce the gendered division of social roles and are an obstacle to the development of women's empowerment and girls' education programs. So, when one of the sexes takes up an activity that is supposed to be reserved for the other, it comes as a shock, as can be seen in the interview extract below.

"Cultures influence the success or failure of programs. As an example, a colleague who wanted to show images to deconstruct task performance by showing an image of the man turning the ball. The room emptied, starting with the women. For them, the man can't come and sit down to turn the ball. We had to intervene to get them back into the room" (man, local actor, Chad).

However,someactorsaredrawingattentiontothediminishinginfluenceofsocialgendernorms on women's empowerment and career trajectories. Girls' education is seen as one of the key