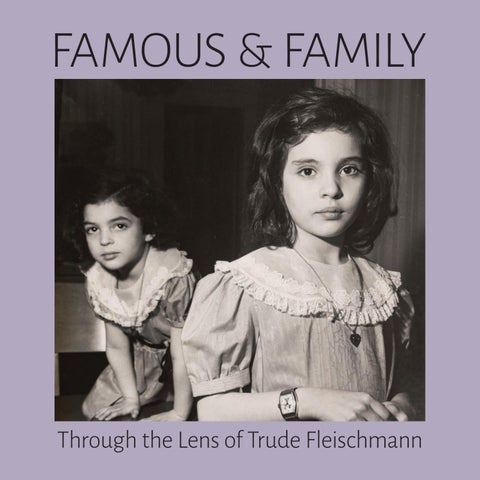

FAMOUS & FAMILY

Through the Lens of Trude Fleischmann

Through the Lens of Trude Fleischmann

May 2 - July 26, 2025

We are so pleased to present this landmark show of over 100 photographs by the Austrian-born photographer Trude Fleischmann (1895-1990), one of the most accomplished female photographers of the 20th century. The show, the first solo museum exhibition of the photographer’s work to be presented in the United States, highlights Fleischmann’s groundbreaking career in Vienna during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as her influential work in the United States after her emigration in 1939. The exhibition features never-before-exhibited works from the Fleischmann/Rosenberg, Haas, and Cornides family collections, as well as the family collection of her student and life-long friend, photographer Helen Post (1907-1979). Together, these works provide an unprecedented and intimate view of the photographer’s personal and professional legacy.

Three years ago, Barbara “Bobbie” Rosenberg Loss popped into my office with the exhibition catalogue from the Trude Fleischmann retrospective, A Self-Assured Eye, held in 2011 at the Wien Museum in Vienna. She asked if I would be interested in curating and presenting an exhibition of Fleischmann’s photographs. After a glance at the remarkable body of work I replied, “Absolutely!” Bobbie has been my co-curator and intrepid partner as we have spent the last three years seeking out examples of Fleischmann’s famous portraits and other work for this exhibition. As she explained at our first meeting, she could supply us with something that no other previous exhibition has had access to: an enormous trove of photographs of Fleischmann’s friends and family. Bobbie has kept in touch with all of them over the years, and as we met with them together, I was able to hear their stories of time spent with Fleischmann, and select those works that I felt truly provided the most insight into her personal life and artistic practice.

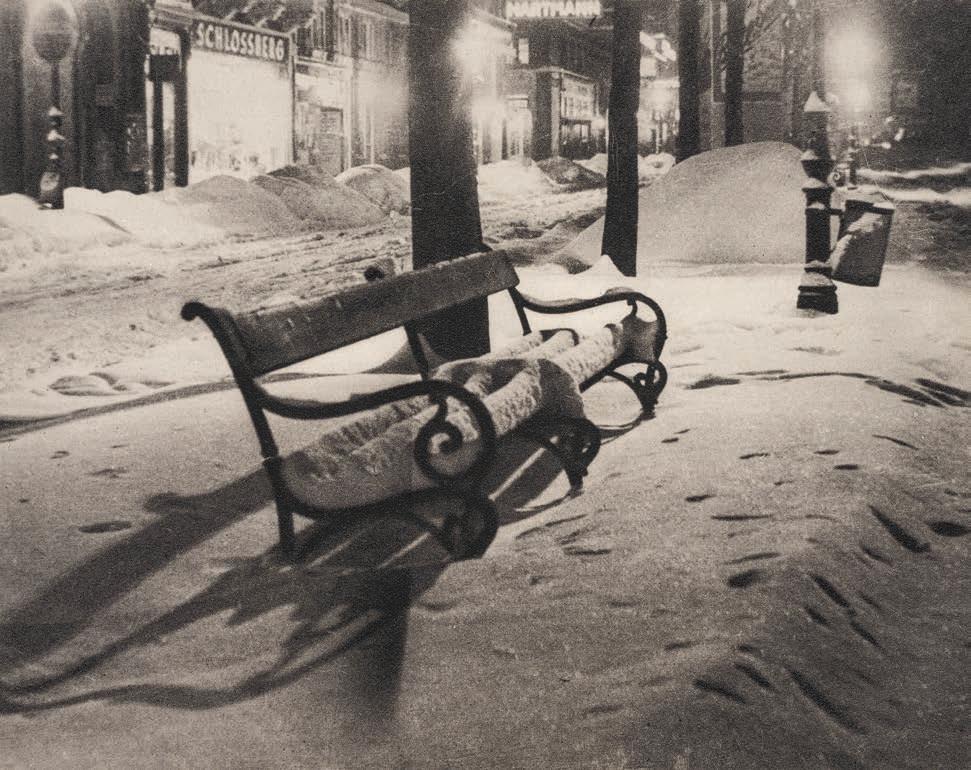

It has been a remarkable journey reconstructing Fleischmann’s career for this exhibition, both through her photographs and with some of the ephemera kept and collected by her extended family. The exhibition opens with her earliest success in Vienna, as a portrait photographer to the cultural elite. This period in Vienna is also captured in her photographs of close family friends Josef and Hermine Cornides and their two sons, as well as images of the Rosenberg family: her aunt, uncle, and cousins. Her intimate photographs of Helen Post also begin in Austria, represented by Helen both at work and relaxing on vacation at a favorite farm in Gössenberg, Styria. While Fleischmann is remembered primarily as a portrait photographer, she was so much more than that. Also included in the exhibition are stunning photographs of the landscapes and cityscapes of her beloved Austria, many of which appeared in calendars and other publications, showcasing the breadth of her talent and the fullness of her artistic practice.

In late 1938, with the help of Helen and Marion Post, and at their urging, Fleischmann was able to get out of Austria and made her way to New York City. She set up a portrait studio there in 1940 and picked up where she had left off. On weekends she visited most frequently with the Rosenberg family in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and with the Post/Modley family in Sharon, Connecticut, but also with many of her clients, who became close friends, as well as fellow immigrant artists including Lisette Model. It is in this section of the exhibition that numerous photographs that have never before been exhibited are found, including those showing her beloved cousins and friends as they grew up in her company. These intimate images reveal Fleischmann using many of the same techniques that she employed in her famous studio portraits, cityscapes and landscapes. She often found a way to shoot her subjects from above, so they are often looking up, sometimes at her. She also always managed to put her sitters at ease, and often included her subjects’ hands in her photographs – make sure to note the different arrangements of the fingers! These were not posed, but simply captured at the right moment.

We are very grateful to the many lenders to this exhibition without whom it would not have been possible. We thank the Wien Museum, Vienna, for their generosity in making this loan possible for us, their curator Frauke Kreutler (who will present the exhibition’s opening night lecture), and their Registrar Andrea Glatz. We would also like to thank the New York Public Library and their curator Elizabeth Cronin (who will present a program on Heimat or “Homeland” photography in conjunction with the exhibition). The “family” of the exhibition’s title provided the majority of the loaned material: these include Barbara Rosenberg Loss and her brother Dr. Henry Rosenberg (Trude Fleischmann’s cousins), Peter Modley (son of Helen Post), Joanna Rueter (granddaughter of Hermine Cornides, daughter of Otto Cornides), and Miriam Haas (daughter of Robert Haas). We are deeply appreciative of their trust as they each lent numerous artworks, which are also the repository of important family memories. Finally, we must thank the private collectors Terry and Melissa Wallace, and Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg for their important contributions to this exhibition.

Heike Herrberg wrote the informative biographic essay on Trude Fleischmann which follows in this catalogue, and which informs many of the wall labels. She will also present a gallery talk with Bobbie Rosenberg Loss and Henry Rosenberg on the topic of Fleischmann as a family photographer the day after the opening. These are invaluable parts of this exhibition and its programming. Herrberg’s essay is the most comprehensive English language biography of Fleischmann to date, and we thank her for writing it for us.

The exhibition is further enriched by the 2019 documentary In nackter Gesesllschaft (The Naked Gaze), which is being screened in the gallery with special permission from the filmmakers Katherina Lochmann and Pogo Kreiner. This film was informed by Anna Auer’s exclusive interview with Trude Fleischmann at her home in retirement in Lugano, Switzerland – the only audio interview ever recorded with the artist. The film brings to life Fleischmann’s Vienna photo studio and its elite clientele during the 1920s and ’30s.

Thanks as always go to the exceptional Museum team for their hard work in bringing this exhibition and its associated programming to life: Michelle DiMarzo, Curator of Education and Academic Engagement; Megan Paqua, Museum Registrar; Heather Coleman, Museum Assistant; and Elizabeth Vienneau, Museum Educator. We are grateful for the additional support provided across the University by Erin Craw, Susan Cipollaro, and Dan Vasconez, as well as by our colleagues in the Quick Center for the Arts, the Media Center, the Center for Arts & Minds, and Design & Print.

~ Carey Mack Weber Exhibition Curator

Frank and Clara Meditz Executive Director

In 1920, at the age of 24, Trude Fleischmann opened her photo studio in Vienna near the Town Hall in the first district on the Ebendorferstrasse, where the rent was quite costly. After a very brief apprenticeship in the studio of the famous Dora Kallmus, Atelier d’Ora, and three years at Atelier Schieberth, the young Trude started her own business. Her training included one semester of art history studies in Paris and three years at the Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt in Vienna, the most important educational institution for photography, where women had only been allowed to train since 1908.

Trude Fleischmann had grown up in the bourgeois-liberal environment of a Jewish merchant family and had their full support, especially that of her mother Adele Rosenberg Fleischmann. To truly grasp the significance of the photographer’s achievements, it is critical to consider the historical context in which she lived.

The First World War was over, and the military collapse had marked the end of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. The multi-ethnic state with its linguistic diversity dissolved into its national components: Bohemia and Moravia, Galicia and Bukovina, Bosnia and Herzogovina, Croatia, Slovenia … Vienna, once the capital of a large empire with different cultures and 54 million people, now remained as a far too big metropolis for the rest of a very small Austria with only 7 million people. At the time, the city was also experiencing immense economic problems, causing citizens to suffer from hunger and poverty. Despite such hardship, the energy in local pubs and coffee houses was increasingly lively. The war had loosened bourgeois mores and Vienna celebrated its downfall in cabarets and at carnival parties to the rhythm of the shimmy, Charleston, and foxtrot.

“Vienna feasts, Vienna dances, Vienna amuses itself, Vienna sings and plays waltzes and more nonsensical operettas than ever before. And the same Vienna is wasting away, is dying, is full of reparations, commissions, and its political leaders are traveling all over the world to ask for help,”1 the journalist Milena Jesenská wrote.

The elections in 1919, when women were allowed to vote for the first time, had brought a comfortable majority for the Social Democratic Party. Vienna was thus governed by the Social Democrats, while the federal government was Christian Social. Consequently, conflicts were inevitable.

In social-democratic “Red Vienna,” many diverse lifestyles were possible. The city was leisurely but cosmopolitan, and there was a lively exchange with other metropolises. The psychoanalytic scene in particular became increasingly international in the mid-twenties. In the American avantgarde, it was fashionable to be analyzed overseas, in the hometown of Sigmund Freud, and many European intellectuals also came to the capital of psychoanalysis for this purpose.

But above all, Vienna in the twenties was a city of art. This made it unique among other prominent European capitals of the time including London, Paris, and Berlin. The culture around actors and actresses had survived the war and mass unemployment. The stars of the theater were more popular in town than politicians or rich elite. Music and theater were the most beloved pastimes of the Viennese society. Those who couldn’t afford even a standing ticket for the opera or Burgtheater, read the reports in the newspapers in one of the numerous coffeehouses the next day. Portrait photos of the stars were enthusiastically collected, exchanged, and sold. The flair attracted artists and anyone who wanted to be part of the scene from the old imperial and royal monarchy to the Austrian capital.

That time of the First Republic was also especially exciting for women, who like Fleischmann, influenced the artistic milieu of the city like never before. Die Bühne (The Stage) was founded, a weekly magazine that addressed the modern, open-minded bourgeoisie and reported on the world of theater and opera, on premieres, nude dancers, winter fashion, and summer travel. The overall magazine market was booming, and with it photography, as the picture editors needed suitable material. Since the medium did not yet have a long tradition, many women interested in art and technology took advantage of these opportunities. The number of professional women photographers grew significantly, not just in Vienna. Most of them remained unmarried and childless. This was also true of Fleischmann, for whom photography was the most important thing in life.

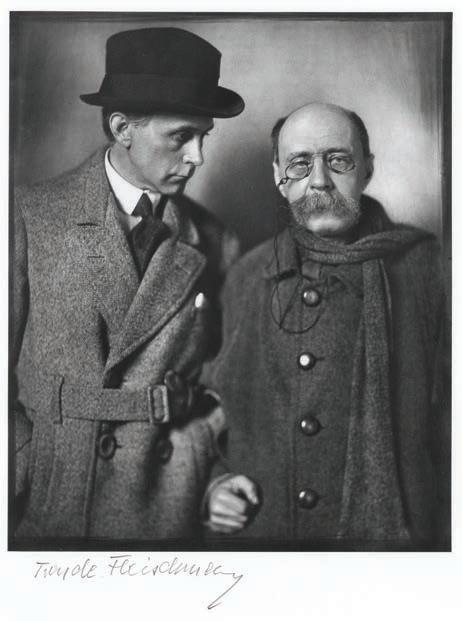

“You must find yourself! … Be whoever you are, no more, no less, but be perfect,” Peter Altenberg had told her and this became her life’s motto. The double portrait of the well-known Viennese poet and the architect Adolf Loos (Cat. 1), created together with her colleague Ilse Pisk, was one of Fleischmann’s first assignments. It brought her into contact with cultural circles that were decisive for her later career.

1 »Wien praßt, Wien tanzt, Wien amüsiert sich, Wien singt und spielt Walzer und unsinnigere Operetten als je zuvor. Und dasselbe Wien siecht dahin, stirbt, ist voller Reparationskommissionen, und seine politischen Führer reisen in der ganzen Welt herum, um Hilfe zu erbitten.« Milena Jesenská: Alles ist Leben. Feuilletons und Reportagen 1919–1939. Frankfurt 1996, p. 15.

Atelier of the Famous

Her studio was unique from those of her colleagues. She did not have walk-in customers and didn’t offer the usual repertoire of wedding, baby and christening pictures. She wanted to develop a personal rapport with her clients and could rely on her large circle of friends and acquaintances who shared her artistic interest. The studio became their meeting point and was also a popular training place. “In her atelier in Vienna, Trude was always surrounded by young men and girls,”2 remembered Robert Haas (Cat. 123), a renowned printer who became her photography student in 1930 and who later became a colleague and friend.

Trude Fleischmann actively advertised for customers and was a brilliant networker. Studio parties, Atelierfeste (Cat. 3), exhibitions, social gatherings – on all these occasions the photographer gained new customers, which exemplified her extraordinary gift of connecting with people of all backgrounds. Seemingly without effort, she could engage with the other person on whatever level of conversation was offered. Her approachable nature and inquisitiveness directly contributed to her remarkable success as a photographer. “She made people feel comfortable when she photographed them, she had incredible empathy and an unobtrusive, very charming manner,”3 explains, like many others, Catherine Haas Riley (Cat. 122), one of Robert Haas’ daughters. “She was interested in everything and was incredibly open and curious,”4 said Lily Munford, whose mother was a cousin and close friend of Trude Fleischmann. “She had guests every evening, for whom she cooked, always without a recipe! She simply attracted people. And they were often free spirits like herself.”

2 „In ihrem Atelier in Wien war die Trude immer von jungen Männern und Mädels umgeben.“ Anna Auer, Fotografie im Gespräch. Passau 2001, p. 160.

3 Phone call, 22.8.2010.

4 C onversation in Pleasantville, 13.5.2009.

Trude Fleischmann was also a media professional, working for the press and publishing regularly in all the important Austrian society, fashion and cultural magazines. Soon her photos also appeared in other German-speaking countries, such as in the highly circulated Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. In these interwar years, no other Viennese female photographer, apart from Dora Kallmus, was as widely present in illustrated magazines as Fleischmann. Though, unlike Kallmus who had firm commitments with some newspapers, the younger colleague worked only by commission. This way, she had personal freedom working according to her own artistic ideas. One of Fleischmann’s notable connections was with the Theater in der Josefstadt, which in 1924 was under the directorship of Max Reinhardt, one of the most important directors of German-language theater in the 20th century. Fleischmann’s portraits were also highly treasured in the Burgtheater, the Deutsche Volkstheater, and the Viennese Opera.

Soon celebrities from music, theater and dance were gathering in her studio. With some of them she developed a personal friendship, like the actress Sybille Binder (Cat. 2), the dancer Tilly Losch (Cat. 7), or the actors’ family Thimig (Cat. 10). Another friend was Alban Berg (Fig. 21), the composer of operas such as Wozzeck or Lulu.

“Then on Christmas Eve 1935 came the news that Alban Berg had died. I had an invitation for that evening, but I was called to photograph the dead Alban Berg. He was in some hospital, I can’t remember which one. I went there with my camera and the spotlights and photographed the dead Alban Berg (Cat. 22) who actually looked like a dead angel. Afterwards I went to this invitation, but I was so distraught that I couldn’t enjoy anything anymore. It was a terribly sad thing!5”

5 „Dann kam am Weihnachtsabend 1935 die Nachricht, daß Alban Berg gestorben sei. Ich hatte für den Abend eine Einladung, wurde aber angerufen, ich möge den toten Alban Berg fotografieren. Er ist in irgendeinem Spital gelegen, ich weiß nicht mehr in welchem. Mit meiner Kamera und den Scheinwerfern bin ich dann hingegangen und hab‘ den toten Alban Berg fotografiert, der eigentlich ausgesehen hat wie ein toter Engel. Nachher bin ich noch zu dieser Einladung gegangen, war aber so verstört, daß ich gar nichts mehr genießen konnte. Das war eine furchtbar traurige Sache!“. Anna Auer, Fotografie im Gespräch, p. 107.

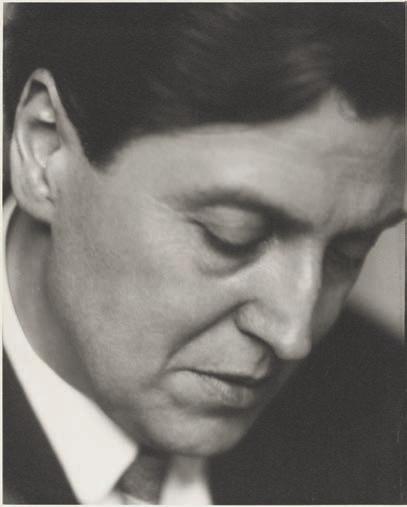

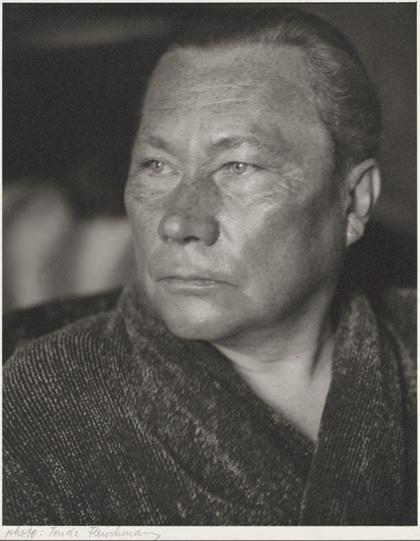

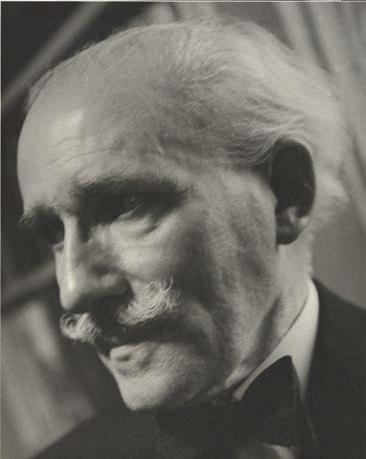

Her studio was also often visited by Wilhelm Furtwängler (Cat. 12), the famous German conductor and composer, with whom she was friends, and by the German-born Bruno Walter (Cat. 25), who later after his emigration became chief conductor of the New York Philharmonic. The German stage and film stars Conrad Veidt and Paul Wegener (Cat. 23) also found their way to the Ebendorferstrasse when they had guest performances in Vienna. Other wellknown customers were the writer Stefan Zweig, the actor Oskar Homolka, the singers Alfred Jerger (Cat. 20) and Michiko Meinl as well as the actresses Lil Dagover (Cat. 9), Luise Rainer, and Dolly Haas.

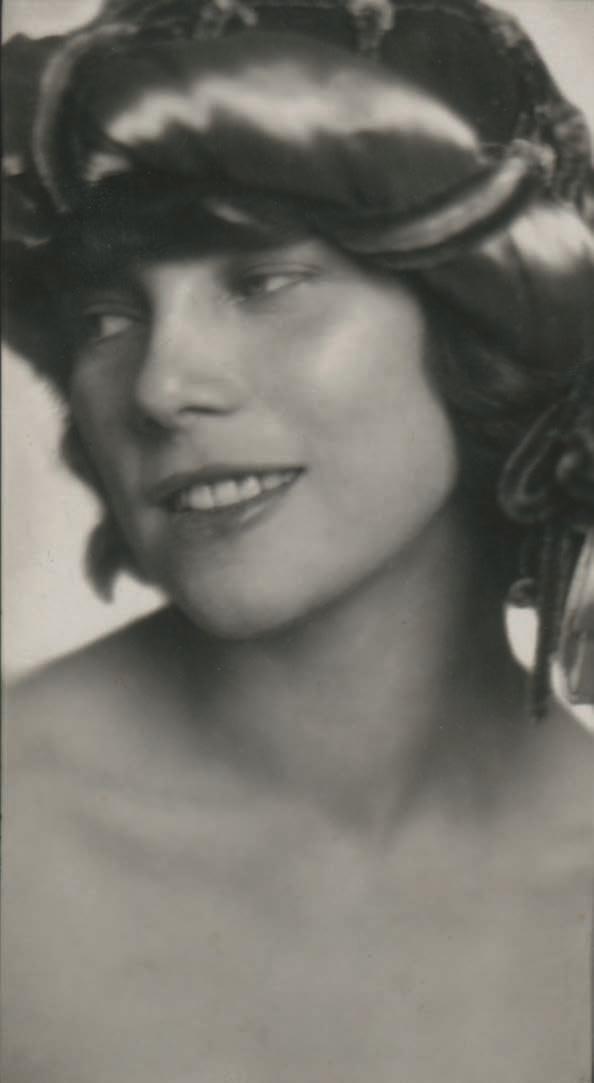

One of the photographer’s early discoveries was Hedi Kiesler, who publicly announced when leaving secondary school her intention to go into film. She eventually became world-famous in Hollywood under the name Hedy Lamarr (Cat. 16). Apart from this, the technically gifted Lamarr developed a radio remote control for torpedoes in 1940/41 to support the American troops’ fight against the Nazi regime. For this she only received public recognition in the 1990s.

Trude Fleischmann was an eager visitor of the lectures and talks of Karl Kraus (Cat. 18), editor of the satirical journal Die Fackel. Like his friend Adolf Loos who was committed to a non-decorative architecture, Karl Kraus, the literary enfant terrible and language philosopher, was fighting for a lean style in literature, one without embellishment. This aspect of reducing things to the essentials attracted Fleischmann. She focused on achieving a sense of distinctiveness with her photographs, working out the uniqueness of a face and the individuality of the person she portrayed. This resulted in large-scale facial and intensive body studies, which became one of her specialties.

Vienna was one of the international centers of modern dance in the first third of the 20th century. Many of the dancers, often from Jewish families, were enormously popular, and they sometimes founded their own dance schools and worked as choreographers.

‘If you want a really good dance photo, you have to go to Fleischmann’, it was said. The photographer documented the dance boom and was herself thrilled with the performances. “I was a great admirer of Grete Wiesenthal. She was for me, and is still today, the best dancer who ever existed. She had so much confidence and naturalness in her dance. She was a dream. Absolutely unbelievable.”6 Even before the First World War Grete Wiesenthal had emancipated herself from the rigid forms of ballet and had developed her own approach to the Viennese waltz. Her international performances had taken her to numerous countries and already in 1912 to New York City.

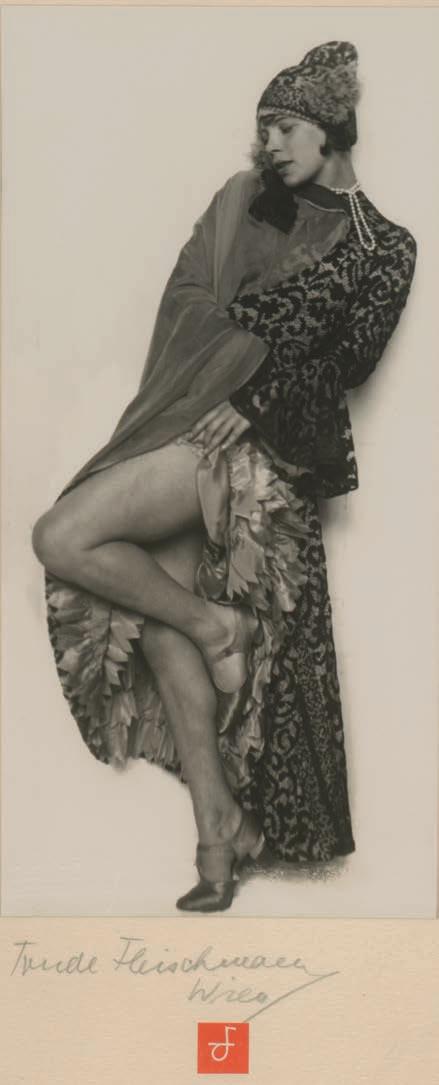

Trude Fleischmann shot most of her dance photos in her studio, composing the scenes down to the last detail. The dancers were not really moving, but simulated it for the camera. The studies were great in demand and dancers like Mila Cirul (Cat. 6), Tilly Losch (Cats. 7, 11), or Katta Stern (Cat. 8) often had their photos taken by Fleischmann. Sometimes she also worked outside, as with Toni 6 „Ich war eine Verehrerin von der Grete Wiesenthal. Sie war für mich, und ist’s noch heute, die beste Tänzerin, die es je gegeben hat. Es war etwas so Selbstverständliches, so viel Natürliches in ihrem Tanz. … Sie war ein Traum! Absolut unglaublich!“. Anna Auer, ibid.

Birkmeyer and his ballet (Cat. 15). The spectacular pictures Fleischmann produced were great publicity for both the dancers and the photographer.

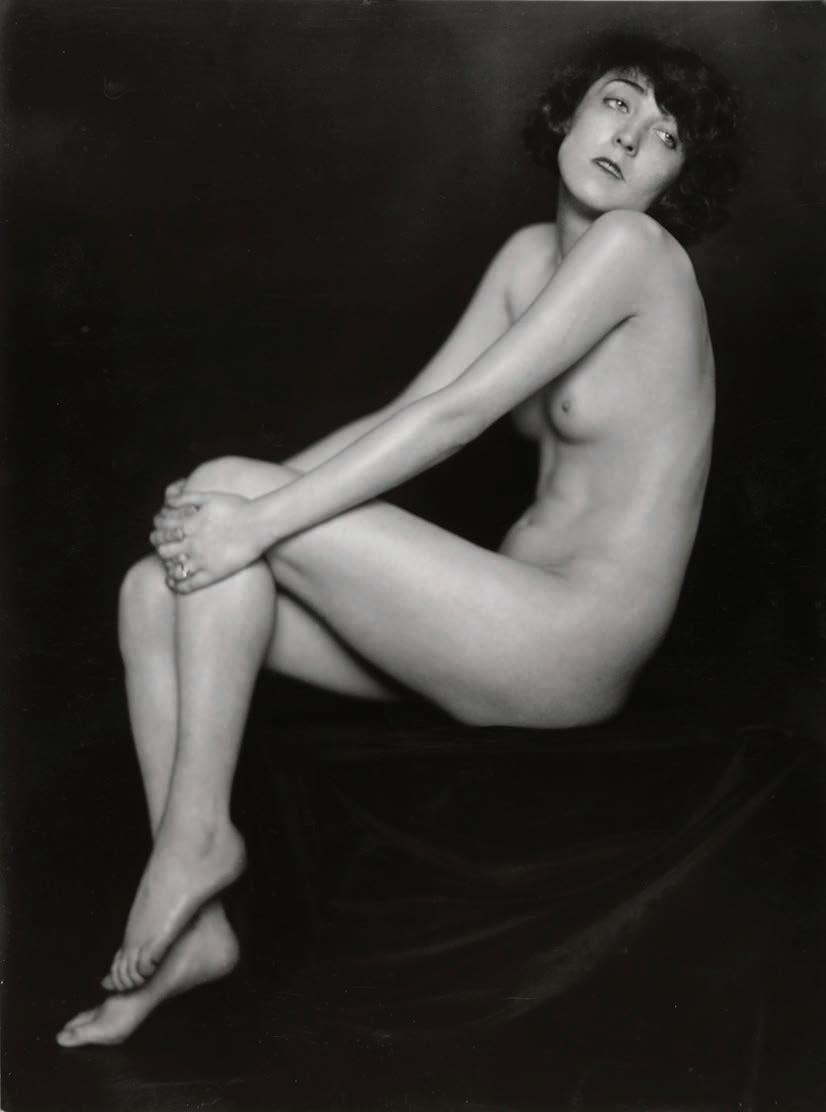

In that heyday of modern dance, dance photography was a genre of its own, with fluid transitions to nude photography. This was not necessarily seen in an erotic context but rather as a liberation from the constraints of society and a closeness to nature. Fleischmann was fascinated by both kinds and soon became the most important photographer of nudes in Austria. For models, she preferred dancers with trained muscular or sculpted bodies, strong women who did not correspond to the cliché of the weaker sex. These pictures also showed her interest in progressive people, especially in emancipated women and unconventional lives. Her close connection to the German dancer Claire Bauroff (Cat. 4), who made headlines in the twenties with her nude appearances on stage and in films, played a significant role in this development. In 1925, when Bauroff had a performance at the Admiralspalast in Berlin, Fleischmann’s photos were on display in the showcase, which caused a riot. A district attorney confiscated them. The justification: too scandalous!

With the global economic crisis and the bank collapse in 1931, unemployment again reached catastrophic proportions, the rich became poor, speculators became inflation millionaires. In 1933, the Austrian Parliament was dissolved. After Hitler came to power in Germany the same year, Jewish artists flocked to Vienna. But just one year later, the antisemitic slogans in Fleischmann’s homeland became louder, reforms were reversed, democratic committees were dissolved, and the progressive press was banned. A civil war broke out in 1934. In three days, social democracy was crushed. For many intellectuals, this was a warning to leave, a signal to make preparations for a life in exile. Fleischmann’s friends warned her to leave the country because they already recognized the upcoming danger for Jews in Austria.

Trude Fleischmann was at the peak of her career, but within a short time, clients were missing, including a great many of Jewish heritage who either had already emigrated or who were in the process of emigrating. For a time, she tried to save her studio, but ultimately recognized the seriousness of the situation, left all her possessions behind, including her well-equipped studio, almost all her cameras, and her pictures. She took only a selection of negatives with her, as well as an album with photographs, and a camera. First, she went to Paris, then on to London. There she applied for a visa for the United States of America. Three months later, in March 1939, she boarded a passenger liner in Southampton to New York.

When she disembarked in Manhattan on April 4, it was Helen Post Modley, a former student and friend, who met her (Cats. 99-106). “She picked me up from the ship and took me straight to her country house, which was about two hours

away from New York City.”7 The cottage was deep in the woods on the edge of the small town of Sharon, Connecticut, with two simple rooms, a water pump and a small washroom in the yard.8 Helen and her husband Rudi Modley (Cat. 96), who came from a Hungarian-Jewish family, had built it in 1936 and used it in the summer and at weekends. In their townhouse on Lexington Avenue (Cat. 92), the couple also often housed Jewish refugees from Austria and Germany, for whom they assumed an affidavit, noting full responsibility for their material existence. Helen had inherited two houses in Manhattan and sold one of them, so she was financially independent.

The two women had known each other for over ten years since Helen Post – and later her sister Marion Post Wolcott (Cat. 67), who became a well-known photographer, working for the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression – had studied photography with Fleischmann in Vienna. Helen and Trude had a close relationship, and according to both Peter Modley, Post’s adopted son (Cats. 108-110), and also Robert Haas, for a while they had a love affair.9 In the late thirties and early forties, Helen Post documented the lives of Native American peoples in the west and southwest of the USA, lived with them for a time and learned their languages. In 1940, she published a book about this with the anthropologist and Pulitzer Prize winner Oliver La Farge.

Helen’s mother, Marion (“Nan”) Hoyt Post (Cats. 65, 114), became a mother figure to Trude. As her grandson Peter points out, she was an activist for progressive causes, a kind of suffragette. She had divorced her husband in the early 1920s and moved to New York’s Greenwich Village, campaigned for women’s right to contraception and was against racial segregation.10 She had a circle of bohemian friends, enjoyed going to the theater and loved classical music. Once she received a letter from Fleischmann, signed with: “Have a wonderful birthday, dear Mom, stay as you are, young and warm and beautiful.”11 On the note, she had printed two photos of a solar eclipse, highlighting one of Fleischmann’s favorite subjects –astronomy. “She often said she would give her life if she could fly to the moon and look at the earth from above,” recalls her cousin Barbara Rosenberg Loss.

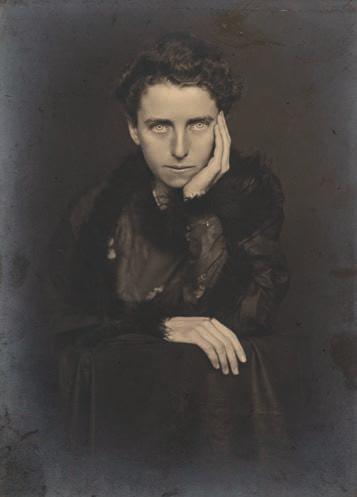

At the end of 1939, the Center for European Immigrants’ Art and Handicraft organized a Christmas sales exhibition in the Empire State Building, where Fleischmann offered her portraits of prominent stage artists, for which she had been famous in Vienna. Eleanor Roosevelt visited the

7 „Sie hat mich vom Schiff abgeholt und gleich in ihr Landhaus gebracht, das etwa zwei Stunden von New York City entfernt lag.“ Anna Auer, p. 108.

8 Interview with Peter Modley on May 21, 2009 in Bethesda, MD. Information on Helen Post, unless otherwise noted, ibid.

9 Anna Auer, p. 160.

10 Paul Hendrickson, Looking for the light. The Hidden Life and Art of Marion Post Wolcott, New York 1992, p. 20 ff. Information on Marion Hoyt Post, unless otherwise noted, ibid.

11 C ollection of Peter Modley. Cat. 92

exhibition and did much of her Christmas shopping there.12 First Lady Roosevelt was known for her progressive thinking and political commitment, which in those years also repeatedly focused on refugees from Europe. It was likely here that the First Lady met Trude Fleischmann, who a few years later took a series of very personal portraits of Mrs. Roosevelt at the country estate in Hyde Park, north of New York (Cat. 39). Pulitzer Prize winner Richard W. B. Lewis and Nancy Lewis chose one of these photos in 1999 for their book American Characters from among “several others that were very distinctly impressive but a trifle more formal and public.”13

At the time that the Germans occupied Paris and threatened London with their bombs, the competition among creative professionals, many of whom were refugees from Europe, was enormous in the American media. Trude Fleischmann now was fighting for her survival like so many others. In this situation, it certainly helped that she was hardly interested in material things. She dressed humbly and didn’t need jewelry or expensive clothes.

In 1940, at the age of 45, she opened a studio in midtown Manhattan on 56th Street, which she initially ran together with Frank Elmer, a colleague from her days in Vienna. The 40-square-meter space was also her apartment, located in the vibrant theater district, between 5th Avenue and Broadway, just behind Carnegie Hall. However, at that time, she also went outdoors more often to take photos, knowing that in the States she would not be successful with studio work alone. In May 1941, some of her fashion photos, taken on the street and the Brooklyn Bridge, were published in Vogue (Cats. 94-95; Vogue Shoot May 15, 1941). And Cipe Pineles, art editor of the fashion magazine Glamour from 1941 and the first woman to be named art director for the magazine, in the following year, hired “the best artists she could find, including photographers Andre Kertesz [...] and Trude Fleischmann; [...] of the many European refugee artists and designers living in New York at that time.”14

In 1941 and ’42, references to Fleischmann’s work appeared sporadically in The New York Times. For example, an exhibition of her photographs was announced in a new gallery on 46th Street, a “Fleischmann Show” at the New School for Social Research or “Camera Studies.”15 At some point, the photographer introduced an anglicized spelling of her name – Fleischman – perhaps after she was granted American citizenship in 1942, and potentially an indication of how connected she felt to the new country.

14 Mar tha Scotford, Cipe Pineles: a Life of Design, New York and London 1999, p. 43.

15 S ee NYT, 18.4.1941, 12.4.1942, 15.4.1942

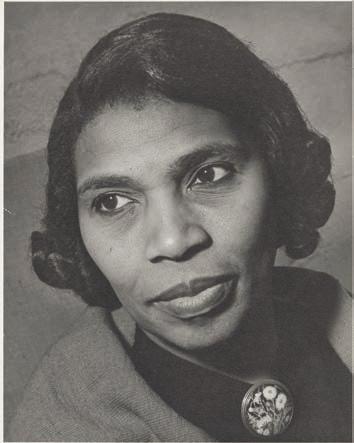

“When we visited Trude, she often told us that she was going over to Carnegie Hall in the evening for a concert or to take pictures of the artists there,” says Barbara R. Loss (Cats. 73, 75, 78), a cousin, who cares deeply about the legacy of her ancestor. One of those artists was Marian Anderson (Cats. 44, 46). The African-American singer was celebrated in many European concert halls in the 1930s. In her own country, however, she was not allowed to perform in Constitution Hall in Washington D.C. in 1939 because of her skin color. With the support of Eleanor Roosevelt, she then gave an open-air concert at the Lincoln Memorial, which was attended by over 70,000 people. Fleischmann had heard the singer for the first time at the Konzerthaus in Vienna –“it must have been in 1932 or ’34” – and was thrilled: “absolutely superb.”16 Marian Anderson was the first Black artist to perform in the Metropolitan Opera in 1955. Trude heard her again and photographed her at her farewell concert ten years later, at Carnegie Hall.

Arturo Toscanini, who had praised Anderson’s voice as the talent of the century, was also a customer of Trude Fleischmann. They knew each other from Vienna and the Salzburger Festspiele, and after the conductor had emigrated to the United States in 1937, Fleischmann took pictures of him on several occasions (Cats. 36-38). She was impressed by the open manner of the maestro, who also invited her to his home in Riverdale, New York. In 1957, she was even allowed to take his photo on his deathbed.

16 L etter to Henry Rosenberg, 5.11.1970.

Helen Post’s son Peter Modley remembers that his mother’s friend often visited her “models” spontaneously. “She simply went there with her camera, knocked, for example, on the door of Albert Einstein (Cats. 42-43) and said: ‘I’m here to take a photo of you.’” Judging by the number of pictures Trude Fleischmann took of the Nobel Prize winner in Princeton, he was quite cooperative. He may have reacted in a similar way as he did to her Berlin colleague Ruth Jacobi: “‘So, so,’ he considered, ‘if you will accept me as I am, without any further ado, even in my slippers, then I am completely at your disposal.’”17 Fleischmann was enchanted by Einstein’s manner. “That was such an experience!,” she still raved years later. “You can’t imagine that: This great man was so unpretentious and tolerant!”18 In 1980, Andy Warhol used one of those photos she had taken in the late forties and early fifties for his Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century 19

Fleischmann loved nature, the Austrian mountains, which in emigration she missed so much, and was fascinated with skiing and hiking. She was an enthusiastic traveler, be it to Italy or Hungary, to Yugoslavia or to cities like Paris or London, where she had friends. And she also enjoyed traveling in the United States.

17 „‚So, so‘, überlegte er, ‚wenn Sie mich aufnehmen werden, so wie ich bin, ohne weitere Umstände, auch in meinen Pantoffeln, dann stehe ich vollkommen zu Ihrer Verfügung.

‘“ Ruth Jacobi, Aufzeichnungen, in: Aubrey Pomerance (ed.), Ruth Jacobi. Fotografien, Jüdisches Museum Berlin 2008, p. 17–57, here p. 42.

18 „Das war ein solches Erlebnis! Das kann man sich gar nicht vorstellen: Dieser große Mann war von einer Einfachheit und Toleranz!“ Anna Auer, p. 106.

19 The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco: www.thecjm.org

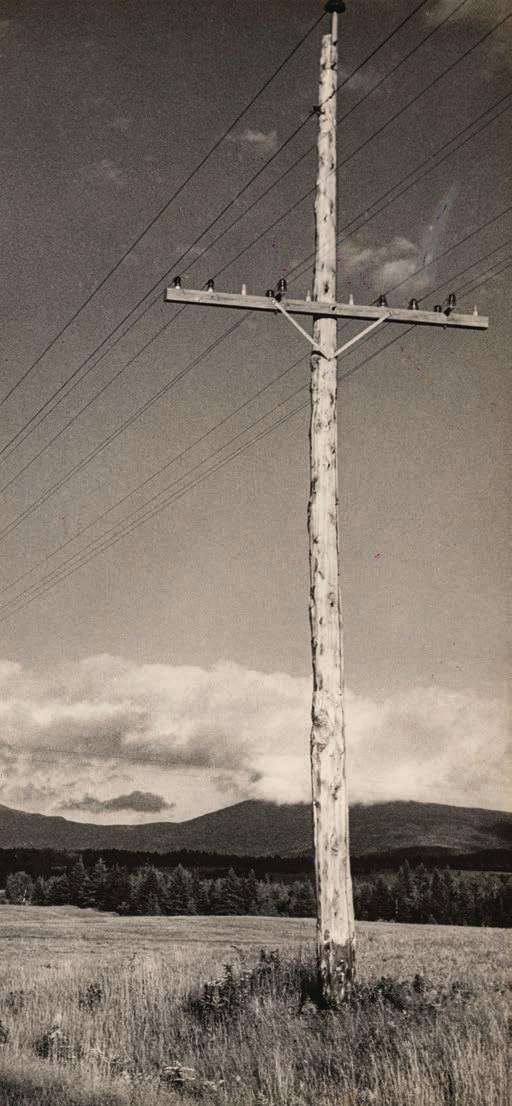

Every summer, she traveled up to Rangeley, Maine, for several weeks. The small town is surrounded by forests and lakes that are perfect for swimming, fishing and hiking. Trude sent photos to relatives and friends and often wrote vacation cards (Cats. 124131). Sender: general delivery. Nobody knew her address. There are indications that she regularly met a man in Rangeley with whom she had been in love for many years, but who didn’t want to separate from his wife.

In the early sixties, she went to Mexico in a Peugeot with her nephew Stefan Carrell and ten-year-old cousin Henry (Cat. 91). Henry Rosenberg later wrote: “In 1962 no one in the U.S. or Mexico had ever heard of a Peugeot. Stefan did all the driving.” Then Trude took the wheel – and was promptly stopped by a state trooper for drifting too far into the oncoming lane. But she “managed to charm him into a warning instead of a ticket. And this in a Peugeot with New York plates.”20

The photographer also had bold dreams about space travel. “If I were young, I would fly with you to the moon,” she wrote to her cousin Henry Rosenberg in 1969. “People are complaining about costs of space travel. Of course, it’s a lot of money. But would they ever use it for reasonable matters? Oh no, they would not build hospitals or art centers or old people’s homes. Some crooks would get richer and richer and decent people will starve anyway. So, let’s fly to the moon!”21

The photographer’s private and professional lives went hand in hand. As she was friends with a lot of her clients, she often took photos of them and their families – after all, she always had her camera with her. In Vienna she had a close relationship to the Cornides family (Cats. 47-54), especially to her friend Hermine Cornides, a physician, and the two sons Otto and Wilhelm. With Otto she remained connected all her life, they visited each other and went skiing together. His daughter Joanna was her “UpsideDown Girl” (Cats. 68-70).

Robert Haas and his family (Cats. 118-123) also remained important to her life, and she often took photos of her colleague and friend, his wife Maude, and their daughters Catherine and Miriam. A lively correspondence and a lot of photos illustrate how close she was with the families of her first cousins Hans Rosenberg (Cats. 58-59, 62-63) and Madeleine Buchsbaum

20 Letter from Henry Rosenberg to Pierre Galarneau, 19.12.1993. 21 Letter to Henry Rosenberg, 24.1.1999. Cat.129

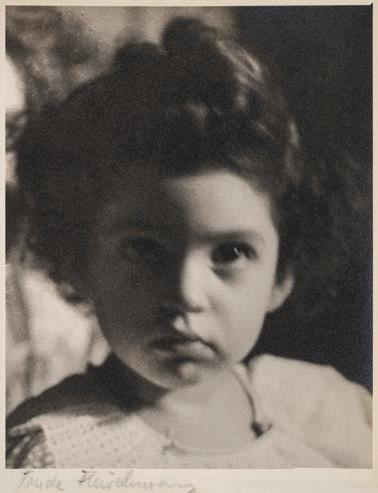

(Cats. 57, 63), whose parents, Heinrich (Cat. 61) and Paula Gewitsch Rosenberg (Cat. 60), had not been able to escape Vienna in time, and had been murdered by the Nazis in 1940. Hans and Madeleine (Cats. 57-58, 63), like their cousin Trude, had managed to flee. Among her very first known photos were those of Hans and Madeleine as little children in 1915.

Hans, his wife Ernestine, and their daughters Sandra and Barbara as well as their son Henry, became some of Trude Fleischmann’s favorite private models (Cats. 71-91). At age 100, Madeleine Buchsbaum still remembered the experience of being photographed with her own teddy bear. She said that her cousin always took very little money for her photos, none at all from the family.

“In our eyes, Trude was always very unconventional, very independent, a bohemian,” says Barbara R. Loss. The bohemian lifestyle also included not worrying about issues like the future, retirement provision or inheritance. The photographer was never really interested in monetizing her archive. “She often had no realistic idea of what things cost,” explained Madeleine Buchsbaum. “When she wanted to move to Switzerland, she was shocked that she had to show a fortune of 7,000 dollars to get a visa. I thought that was rather cheap.”

At the age of 75, Trude Fleischmann moved back to Europe, from the big city of New York to the tranquil Swiss town of Lugano. And she left the States with mixed feelings. “If I can’t stand it over there, I’ll come back to you. Thank you for giving me this reassuring feeling,”22 she wrote to her cousin Hans Rosenberg in Connecticut in January 1970, shortly before her departure. She had added a photo showing her at a lecture in December 1969 at the Austrian Institute, the cultural institute on 52nd Street, which had organized a farewell exhibition.

From February 1970, she lived in Viganello, a small community near Lugano. She often spent time here in the company of her close friend Otto Ashermann, a playwright, continuing to hike and ski. But she increasingly suffered from poor hearing. She often argued with Robert Haas, who was almost blind in old age, about what was worse: going deaf or going blind.

For Trude Fleischmann’s upcoming 90th birthday, the Austrian Institute once again presented her photographs and flew the photographer in from Switzerland. “It was wonderful and I really enjoyed America and N.Y.C. again. Everything is so generous, including the people, very different from Europe!,”23 she wrote to Madeleine Buchsbaum afterwards. As she became increasingly frail, her nephew Stefan Carrell brought her back to the US, caring with his partner Pierre Galarneau for her in Brewster, NY, until her death in 1990.

22 “Wenn ich es drüben nicht aushalte, komme ich zu Dir zurück. Sei bedankt, dass Du mir dieses beruhigte Gefühl geben kannst.“ Letter from 29.1.1970, collection Barbara R. Loss.

23 „Es war herrlich und ich habe Amerika und N.Y.C. wieder sehr genossen. Alles ist so großzügig, auch die Menschen, ganz anders als in Europa!“ Letter from 18.10.1984, collection Barbara R. Loss.

An exhibition catalog in 1983 stated: “She never considered the historical importance of her photographs. She certainly recognized the renown of her clients. Nevertheless, she was too modest…too humble, to foresee the value of her collection. Consequently, her collection remained her private treasure…actually her very biography.”24

~ Heike Herrberg, 2025

1895 Born December 22 in Vienna, Austria to an affluent Jewish family. Her father Wilhelm was a salesman originally from Hungary. He and her mother Adele (Rosenberg) Fleischmann were major financial and emotional supporters of her early career.

1904 Receives a much-wanted first camera as a gift.

1916 Graduates from Lehr-und Versuchsanstalt f ür Photographie und Reproduktionsverfahren (Imperial-Royal Teaching and Research Institute for Photography and Reproduction Processes), Vienna. This vocational college, founded in 1888, first admitted women in 1908.

1916 Becomes an apprentice photo-finisher in the studio of well-known portraitist Madame d’Ora (Dora Kallmus) – for just two weeks.

1917 Begins to work with photographer Hermann Schieberth, whose clientele she greatly admires.

1919 Becomes a member of the Viennese Photographic Society.

1920 Opens her studio at EbendorferstraBe 3 in Vienna, with financial assistance from her family. At the age of 24, she is likely the youngest woman to have opened a studio in Vienna pre-1920.

1925 Achieves international fame after a Berlin district attorney confiscates her nude photographs of dancer Claire Bauroff for indecency during an exhibition at a local theater.

1928 Meets American Helen Post who is visiting Vienna. Post begins studying with Fleischmann, marking the start of their lifelong friendship.

1938 Flees Vienna after the Nazi Anschluss, and is assisted in getting to the United States via Paris and London by Helen Post.

1939 Arrives in New York City and moves in with Helen Post and her husband Rudi Modley in their home at 142-144 Lexington Avenue.

1940 Opens a studio in her new apartment at 127 West 56th Street. Continues her portrait practice but supplements it with occasional fashion work for American Vogue and other publications.

1940- Photographs the family and friends seen in this exhibition during frequent weekend visits from New York City 1968 to Connecticut and Westchester.

1969 Retires to Lugano, Switzerland after fifty years of work as a portrait photographer.

1987 Returns to New York City from Lugano to live with her nephew once independent living becomes too difficult.

1990 Dies on January 21 in Brewster, New York.

This exhibition, Famous & Family: Through the Lens of Trude Fleischmann is the first solo museum exhibition of the artist’s work to be presented in the United States.

Solo Gallery Exhibitions in the United States

1942 Trude Fleischmann Just Photos, Solo exhibition at New School for Social Research, New York, NY, April 12-29, 1942

1969 Trude Fleischmann Photographs, Austrian Institute, New York, NY, 1969

1981 Trude Fleischmann, Vintage Photographs, Solo exhibition at Braunstein Gallery, San Francisco, CA, March 3-April 4, 1981

1983 Trude Fleischmann Photographs 1918-1946, Retrospective exhibition at Thorpe Intermedia Gallery, Sparkill, NY, November 6-December 4, 1983

1984 Trude Fleischmann Photographs, Marcuse Pfeifer Gallery, New York, NY, October 9-November 15, 1984

1984 Trude Fleischmann Photographs 1918-1939, Austrian Institute, New York, NY, September 11-October 4, 1984

1990 Trude Fleischmann, Retrospective exhibition at YMYWHA of Bergen County, Township of Washington, NJ, March 18-April 30, 1990

1994 Faces of Women by Trude Fleischmann, One-person exhibition at J CC on the Palisades, Tenafly, NJ

1996 Vintage Photographs 1922-36 by Trude Fleischmann, Solo exhibition at Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, East Hampton, NY, June 15-24, 1996

Select Group Exhibitions in the United States

1994 Women on the Edge – Twenty Photographers in Europe, 1919-1939, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, March 11-May 29, 1994

2021 The New Woman Behind the Camera, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, July 2-October 3, 2021

2021- The New Woman Behind the Camera, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, October 31, 2021-June 30, 2022

2022

Famous Europeans & Scenic Europe

1. Peter Altenberg (1859-1919), Writer and Adolf Loos (1870-1933),

Architect, Vienna, 1918, printed 1988

Gelatin silver print

9 3/8 x 7 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

Created with photographer Ilse Henriette Pisk

2. Sybille Binder as “Mary Dugan,” Vienna, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 x 6 ¾ inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

3. Atelierfest März Album [Studio Fest Album]

Self-Portrait in Hungarian Costume, 1923

Gelatin silver print

4 3/8 x 3 ½ inches

Album containing 11 gelatin silver prints

7 3/8 x 5 inches (album size)

Image sizes variable

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

4. Action Study of Dancer Claire Bauroff (1895-1984), Vienna, 1924

Bromoil gelatin silver print

14 x 10 ½ inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

5. Anna Bahr-Mildenburg (1872-1974), Singer, Vienna, ca. 1925

Gelatin silver print

8 ¾ x 6 ½ inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

6. Mila Cirul (1901-1977) Dancer, Vienna, ca. 1925

Gelatin silver print

5 ¼ x 6 ¾ inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

7. Tilly Losch (1903-1975), Dancer, Vienna, ca. 1925

Gelatin silver print

7 7/8 x 4 3/8 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

8. Katta Stern (1897-1983), Dancer, Vienna, ca. 1925

Gelatin silver print

9 ¼ x 3 3/8 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

9. Lil Dagover, 1926

Gelatin silver print

4 7/8 x 3 3/4 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

10. Helene Thimig, 1926

Gelatin silver print

4 7/8 x 3 ¾ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

11. Tilly Losch (1903-1975), Dancer, Vienna, 1927-1928

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 x 6 7/8 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

12. Wilhelm Furtwängler, 1928

Gelatin silver print

4 ¾ x 3 1/4 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

13. Action Study of Dancer Maria de las Nieves, Vienna, ca. 1929

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 x 6 5/8 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

14. “Frau Gusti S.,” Vienna, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 x 6 7/8 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

15. Toni Birkmeyer Ballet in “Cancan,” Vienna, 1930

Gelatin silver print

7 ¼ x 6 7/8 inches

Collection of Michael Mattis & Judith Hochberg

16. Hedy Lamarr, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 7 5/8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

17. “Ralf,” Vienna, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

8 5/8 x 5 ¾ inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

18. Karl Kraus (1874-1936), Writer, Austria, 1930, printed 1988

Gelatin silver print

9 3/8 x 7 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

19. Hugo Thimig, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

5 x 3 ¼ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

20. Alfred Jerger, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

5 x 3 ¼ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

21. Alban Berg, ca. 1934

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D.

Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

22. Alban Berg, Dec. 24, 1935

Gelatin silver print

8 x 9 ½ inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D.

Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

23. Paul Wegener, 1936

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

24. Oscar Kokoschka, London, 1939

Gelatin silver print

7 ¼ x 9 3/8 inches

Lent by Terry and Melissa Wallace

25. [Bruno Walter], 1937

Gelatin silver print

5 x 3 ¼ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

26. [Paula Wesseley], ca. 1935-1938

Gelatin silver print

4 ¾ x 3 1/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

27. [Harvest], 1930

Gelatin silver print

40 x 39 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

28. Near Schladming, Styria, 1930

Gelatin silver print

40 x 39 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

29. Plein Air (Madrina di Stugnano, Italy), 1930

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 x 6 7/8 inches

Collection of Michael Mattis & Judith Hochberg

30. [Schloss Mirabell, Salzburg], 1930

Gelatin silver print

4 ¾ x 3 3/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

31. Sculpture in Hellbrun, Salzburg, 1930

Gelatin silver print

4 7/8 x 3 3/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

32. [Residenzbrunnen, Salzburg], ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

4 x 3 7/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

33. Upper Salzburg, At the Festival, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

7 ½ x 7 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

34. [Interior Decoration, Festung HohenSalzburg, Bas Relief Depicting Archbishop Keutschach, Salzburg], ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

7 13/16 x 7 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

35. [ Vienna Under Snow], ca. 1930s

Gelatin silver print

6 ½ x 5 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

The Famous in America

36. Arturo Toscanini, 1943

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 5/8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D.

Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

37. Arturo Toscanini with his Wife and Photographer Robert Haas, 1946

Gelatin silver print

8 ¼ x 7 7/8 inches

Lent by the Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

38. Arturo Toscanini, n.d.

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 x 7 ¾ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

39. Eleanor Roosevelt (Hyde Park), 1944

Gelatin silver print

10 x 8 inches

Lent by Terry and Melissa Wallace

40. Gian Carlo Menotti, 1946-1947

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D.

Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

41. Sinclair Lewis, n.d.

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 7 7/8 inches

Lent by Terry and Melissa Wallace

42. Albert Einstein, 1947

Gelatin silver print

9 ¾ x 7 7/8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D.

Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

43. [Albert Einstein], ca. 1947

Gelatin silver print

13 ¾ x 10 ¾ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

44. Marian Anderson, 1952

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 8 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

45. Loewenguth Quartet, 1953

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 7 inches

Lent by the Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

46. Marian Anderson, 1964

Gelatin silver print

5 5/8 x 3 13/16 inches

Printed in Lugano, Switzerland

Lent by Dr. Henry Rosenberg

Austrian Friends & Family

47. Josef Frederik Cornides, ca. 1915

Gelatin silver print

9 ¼ x 6 ¼ inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

48. [Dr. Hermine Stahl Cornides], 1924

Gelatin silver print

8 x 6 ¼ inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

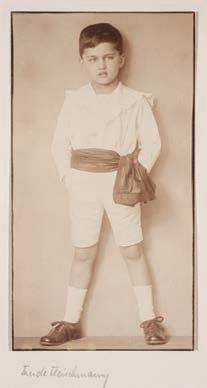

49. [Otto & Wilhelm Cornides], 1921

Gelatin silver print

7 5/16 x 6 6/16 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

50. Otto Cornides, Age 3, 1921

Gelatin silver print

8 x 5 1/4 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

51. [Otto Cornides Smiling], ca. 1931

Gelatin silver print

8 ½ x 6 1/2 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

52. Otto Cornides, New York, 1968

Gelatin silver print

10 x 8 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

53. [ Wilhelm Cornides as a Young Boy], 1924

Gelatin silver print

9 x 6 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

54. [ Wilhelm Cornides as an Aviator], 1936

Gelatin silver print

9 x 6 ½ inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

55. From S.S. to Monk Pater Augustine, 1938

Gelatin silver print

4 ½ x 3 ¼ inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

56. Father Augustine Cornides First Mass, New York City, 1953

Gelatin silver print

5 x 3 3/16 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

57. [Anna Madeleine Rosenberg with Teddy Bear], 1915

Gelatin silver print

9 x 5 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

58. [Hans Rosenberg in White], 1915

Gelatin silver print

7 1/16 x 10 5/8 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

59. [Hans Rosenberg Holding a Book], 1923

Gelatin silver print

9 x 6 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

60. Paula Gewitsch Rosenberg, 1926

Gelatin silver print

9 ¼ x 5 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

61. Heinrich Rosenberg, 1921

Gelatin silver print

13 x 10 3/4 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

62. Hans Rosenberg, ca. 1930

Gelatin silver print

8 ¾ x 6 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

63. Anna Madeleine and Hans Rosenberg, ca. 1935

Gelatin silver print

6 ½ x 8 7/8 inches

Lent by Dr. Henry Rosenberg

64. [Robert Haas Portfolio with Seven Photographs of Helen Post], n.d.

Gelatin silver prints

Variable dimensions

Lent by Peter Modley

65. “Nan Post,” Atelier Trude Fleischmann, Wien, 1935

Gelatin silver print

8 9/16 x 7 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

66. [Helen Post on the Balcony at the Farm], 1933

Gelatin silver print

8 x 6 ¾ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

67. [Marion and Helen Post in Vienna], 1930

Gelatin silver print

4 x 5 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

American Friends & Family

68. [ Joanna Cornides as a Baby], 1949

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

69. “My Upside-Down Girl,” 1958

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 8 ¼ inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

70. [ Joanna Cornides Nomer in Flower Girl Dress], 1957

Gelatin silver print

10 x 8 inches

Lent by Joanna Rueter

71. [Ernestine Rosenberg], ca. 1944

Gelatin silver print

8 ¾ x 6 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

72. [Sandra Rosenberg in a Hat], 1945

Gelatin silver print

7 x 4 7/8 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

73. [Barbara Rosenberg with Lace Collar], ca. 1948

Gelatin silver print

4 7/16 x 3 9/16 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

74. [Hans Rosenberg with Daughters Sandra and Barbara], 1946

Gelatin silver print

8 7/16 x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

75. [Barbara Rosenberg on the Bed], ca. 1948

Gelatin silver print

7 9/16 x 9 5/8 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

76. [Ernestine Rosenberg with Daughters Sandra and Barbara], ca. 1948

Gelatin silver print

7 ¾ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

77. [ The Piano Lesson: Sandra and Barbara Rosenberg], 1949

Gelatin silver print

7 ½ x 9 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

78. [Barbara Rosenberg and Sandra‘s Peggy Doll], ca. 1948

Gelatin silver print

10 13/16 x 7 7/8 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

79. [Sandra and Barbara Rosenberg with Golden Heart Necklaces], 1951

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

80. [Hans, Sandra and Barbara Rosenberg with the Record Player], ca. 1950

Gelatin silver print

7 x 9 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

81. [Hans and Ernestine Rosenberg], ca. 1952

Gelatin silver print

7 ½ x 8 ¾ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

82. [Rachelle and Hermann Rosner], ca. 1952

Gelatin silver print

9 5/8 x 7 11/16 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

83. [Henry Rosenberg Holding onto Mommy’s Skirt], 1952

Gelatin silver print

7 ¾ x 8 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

84. [Barbara, Sandra and Henry Rosenberg in the Backyard], ca. 1953

Gelatin silver print

7 7/16 x 9 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

85. [Barbara and Ernestine Rosenberg], ca. 1953

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 9/16 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

86. [Sandra Rosenberg as a Flower Girl], 1954

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

87. [Ernestine Rosenberg with Straw Hat and Handbag], ca. 1959

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

88. [Henry Rosenberg Behind the Couch], 1959

Gelatin silver print

9 ¾ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

89. [Barbara Rosenberg with Zalathiel Vargas Painting], 1961

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 ¾ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

90. [Sandra Rosenberg with Circle Pin], ca. 1961

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 7 13/16 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

91. [Henry Rosenberg in Mexico], 1962

Gelatin silver print

9 ¼ x 7 5/8 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

92. [Helen Post in her Apartment at 142-144 Lexington Ave.], ca. 1940-1945

Gelatin silver print

9 ¾ x 7 9/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

93. [Brooklyn Bridge], 1940

Gelatin silver print

8 x 7 5/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

94. Fashion Photo N.Y., ca. 1941

Gelatin silver print

13 7/8 x 11 inches

Lent by Terry and Melissa Wallace

95. Fashion Photo, Vogue, 1941

Gelatin silver print

13 7/8 x 11 inches

Lent by Terry and Melissa Wallace

96. [Helen Post and Rudi Modley], ca. 1940-1945

Gelatin silver print

7 3/16 x 8 1/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

97. New York City, n.d.

Gelatin silver print

4 ½ x 3 11/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

98. 127 W. 56 St. N.Y.C., n.d.

Gelatin silver print

4 13/16 x 3 5/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

99. [Helen with Uncle Siegfried], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

4 ½ x 3 9/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

100. [Helen Post with Camera and Flash], ca. 1940-1945

Gelatin silver print

8 1/8 x 7 7/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

101. [Helen Post on Raft], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

7 7/16 x 9 7/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

102. [Helen Post’s Legs], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 x 7 7/16

Lent by Peter Modley

103. [Helen Post Holding her Ears], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

5 5/8 x 3 7/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

104. [Helen Post at the Beach], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

7 5/16 x 8 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

105. [Helen Post at the Beach with Shadows], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

7 9/16 x 8 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

106. [Helen Post in the Trunk of Her Car], ca. 1945

Gelatin silver print

8 ¼ x 7 ¾ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

107. Self-Portrait, n.d.

Gelatin silver print

9 ¾ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Terry and Melissa Wallace

108. [ The Photographer’s Hands with Cigarette and Ashtray], ca. 1940-1945

Gelatin silver print

8 x 6 7/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

109. “Who Can Make A Funnier Face,” 1945

Gelatin silver print

6 3/16 x 4 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

110. [Peter Modley in Carriage], July 1946

Gelatin silver print

5 ½ x 4 7/8 inches (image)

Lent by Peter Modley

111. “Mom you talk too much,” 1946

Gelatin silver print

9 x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

112. Milkweed, Connecticut, 1945

Gelatin silver print

9 11/16 x 7 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

113.[Peter Modley], ca. 1956

Gelatin silver print

7 3/8 x 8 ½ inches

Lent by Peter Modley

114. [Marion Post and Marion Modley], ca. 1950-1955

Gelatin silver print

8 9/16 x 7 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

115. [Marion Modley], n.d.

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 5/8 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

116. [Phyllis and Peter Modley], ca. 1965

Gelatin silver print

7 9/16 x 9 9/16 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

117. [Helen Post with a House Plant], ca. 1965

Gelatin silver print

10 x 13 inches

Lent by Peter Modley

118. [Robert and Miriam Haas], ca. 1965

Gelatin silver print

8 15/16 x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Miriam Haas

119. [Robert Haas], ca. 1945

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 9/16 inches

Lent by Miriam Haas

120. [Miriam Haas], ca. 1961

Gelatin silver print

7 ½ x 9 inches

Lent by Miriam Haas

121. [Maude Daube Haas], 1946

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 7 ½ inches

Lent by Miriam Haas

122. [Robert and Catherine Haas], 1948

Gelatin silver print

4 ¼ x 3 5/8 inches

Lent by Miriam Haas

123. [Robert Haas in his Studio], ca. 1943

Gelatin silver print

3 13/16 x 3 5/16 inches

Lent by Miriam Haas

124. [Goat Christmas Greetings from Lugano], ca. 1969

Postcard

4 x 6 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

125. [Rangeley Maine Tree], 1967

Postcard

5 ½ x 3 ¼ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

126. Pictures Taken during the Eclipse, July 20, 1963

Postcard

3 4/5 x 7 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

127. [Mexican Head (Man on the Moon)], ca. 1969

Gelatin silver print

5 x 3 3/4 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

128. [Icarus from Rangeley, Maine, August], ca. 1965

Postcard

4 x 6 inches

To Hans Rosenberg

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

129. [ Telephone Pole, Rangeley, Maine], 1964

Postcard

9 3/16 x 4 3/5 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

130. [Sunset, Rangeley, Maine], 1967

Postcard

5 ½ x 3 3/4 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

131. [Bears in Yellowstone Park], 1948

Postcard

4 x 6 inches

Lent by Dr. Henry Rosenberg

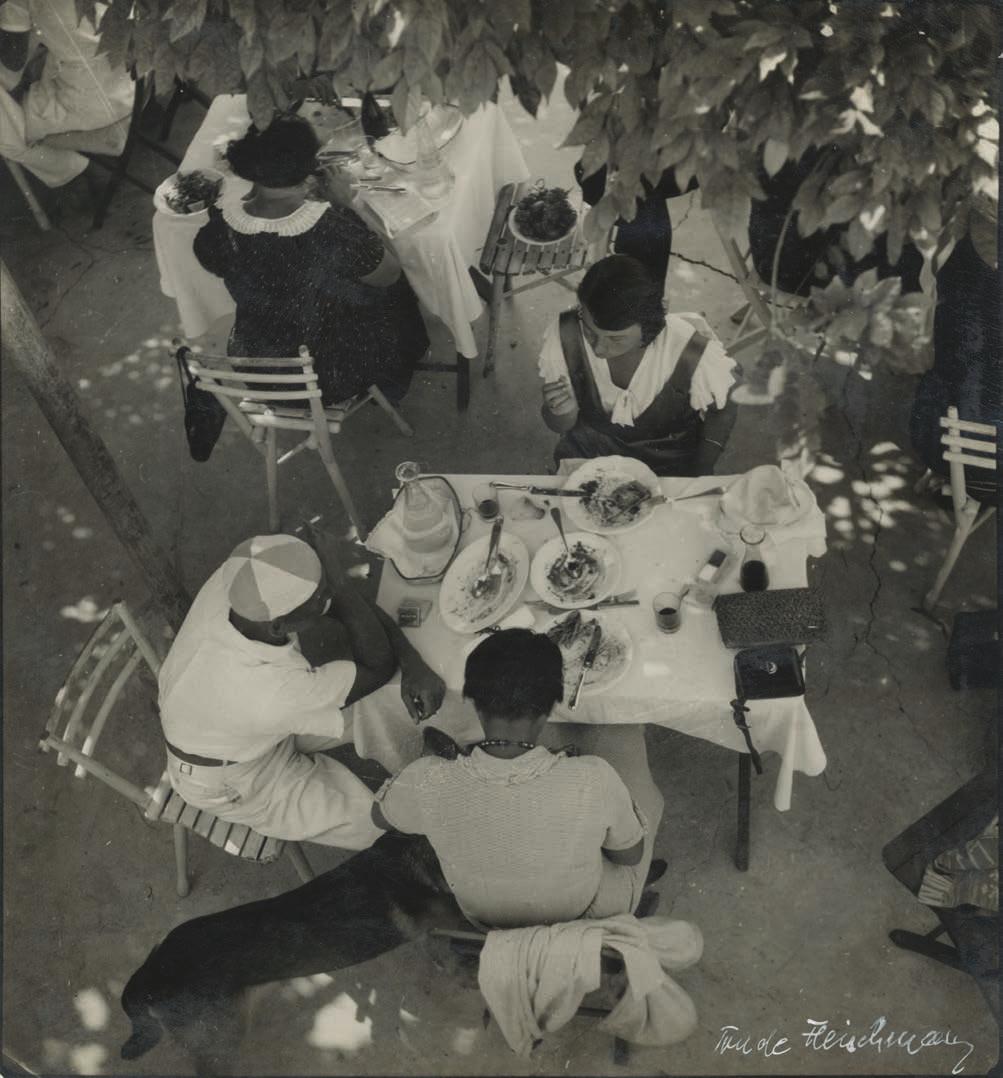

132. Die Bühne Magazine, September 1937

Dejeuner in Italy

Magazine

11 ¾ x 9 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

133. Beautiful Austria calendar, 1946

8 ½ x 7 x ½ inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

Includes 35 photographs by Trude Fleischmann

134. Beautiful Austria calendar, 1947

Published by Paramount Publishing Co., New York, NY

8 9/16 x 7 ½ x 1 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

Includes 13 photographs by Trude Fleischmann

135. US Camera Magazine, 1941

Nude

Magazine

12 5/8 x 11 ¾

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

136. The World As I See It [Portrait of Albert Einstein], n.d.

Book with gelatin silver print mounted on first page

7 ½ x 4 7/8 x ¾ inches (book)

6 11/16 x 4 9/16 inches (photograph)

Lent by Dr. Henry Rosenberg

137. Furtwängler Recalled

Book

8 1/8 x 5 ½ x 1 inches

Lent by Barbara Rosenberg Loss

Events listed below with a location are live, in-person programs. When possible, those events will also be streamed and the recordings posted to the Museum’s YouTube channel.

Thursday, May 1, 5 p.m.

Opening Lecture: Famous & Family: Through the Lens of Trude Fleischmann

Frauke Kreutler, Curator, Wien Museum, Vienna, Austria

Part of the Edwin L. Weisl, Jr. Lectureships in Art History, funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation

Dolan School of Business Event Space and streaming

Thursday, May 1, 6-8 p.m.

Opening Reception: Famous & Family: Through the Lens of Trude Fleischmann

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries and Great Hall With live Viennese-inspired music by a string quartet

fairfield.edu/museum/trude-fleischmann

All works © Trude Fleischmann unless otherwise noted.

All works lent by the New York Public Library, images are courtesy of The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library.

All works lent by the Wien Museum, images are courtesy of the Wien Museum.

Page 7, Cat. 1: © Trude Fleischmann; Photo: Birgit and Peter Kainz, Wien Museum

Page 13, Cat. 18: © Trude Fleischmann; Photo: Birgit and Peter Kainz, Wien Museum

Page 17, Cat. 13: © Trude Fleischmann; Photo: Birgit and Peter Kainz, Wien Museum

Friday, May 2, Noon

Gallery Talk: Heike Herrberg, Barbara Rosenberg Loss, and Dr. Henry Rosenberg Discuss Trude Fleischmann as Family Photographer

Bellarmine Hall, Bellarmine Hall Galleries Note: this event is in-person only and will not be recorded

Saturday, May 10, 12:30-2 p.m. and 2:30-4 p.m.

Family Day: Gold and Glitter in Vienna! Bellarmine Hall, Museum Classroom Arts and crafts for ages 4-10. Space is limited; registration required

Thursday, June 12, 5 p.m.

Lecture: Heimat Photography and the Art of Trude Fleischmann

Elizabeth Cronin, Robert B. Menschel Curator of Photography, Wallach Division, The New York Public Library

Bellarmine Hall, Diffley Board Room and streaming

Cover: Cat. 79

Title page: Cat. 112

Back cover: Cat. 127

The Fairfield University Art Museum is deeply grateful to the following corporations, foundations, and government agencies for their generous support of this year’s exhibitions and programs. We also acknowledge the generosity of the Museum’s 2010 Society members, together with the many individual donors who are keeping our excellent exhibitions and programs free and accessible to all and who support our efforts to build and diversify our permanent collection.

Hazeltine Trust