The Spokane County Firearm Violence Prevention Community Needs Assessment is a crucial and timely contribution to the health and well-being of our region. At Excelsior Wellness, we believe that every person deserves the opportunity to grow, heal, and thrive in a safe and supportive community. This assessment highlights that firearm violence remains an urgent public health issue, fundamentally connected to our mission of providing whole-person, integrated care for individuals and families.

Firearm-related injuries and deaths do not occur in isolation; they reflect broader systemic challenges, including limited access to mental health care, cycles of trauma, and a pressing need for more effective prevention strategies. The findings of this report reaffirm what we witness every day: communities are demanding deeper investment in behavioral health, early intervention, and culturally responsive care. These services are not just what we offer; they are the foundation of our mission.

I extend my gratitude to Excelsior Wellness’s Office of Research and Evaluation for their thoughtful and rigorous approach. This work not only amplifies the community’s voice but also establishes a clear path forward—one rooted in equity, healing, and actionable steps.

At Excelsior Wellness, we are committed to being part of the solution. As we continue to build integrated systems of care and expand access for underserved populations, we carry the insights from this report with us. To effectively prevent firearm violence, we must address its root causes with compassion, data-informed strategies, and a collective belief that a better future is possible for everyone.

With appreciation,

Andrew Hill President & CEO Excelsior Wellness

The Spokane County Firearm Violence Prevention Community Needs Assessment (CNA) is a groundbreaking effort. This comprehensive report focuses on Eastern Washington, particularly Spokane County, providing a deep dive into firearm-related incidents, deaths, injuries, and community perspectives to help shape evidence-based prevention strategies. Nothing like this has been done before at this scale, making it an invaluable resource for community-based organizations across our region. Between 2018 and 2022, Spokane County saw 348 firearm-related deaths. Firearms remain the leading cause of death in the county. There are significant racial disparities, with Black and Hispanic residents facing disproportionately high rates of firearm-related deaths. Youth firearm violence is a growing concern, with death rates for ages 0-24 in Spokane County consistently exceeding state averages. This assessment goes far beyond statistics. The team employed a mixedmethods approach to support not only salient statistics but also stories from our partners with lived experiences. Community members pointed to mental health access, suicide prevention, and domestic violence interventions as top priorities, and this report dives deep into each topic for Spokane County.

I would like to extend special thanks to Andrew Ogwang and Lauren Dodier, members of our Research and Evaluation team, for their leadership in productive community meetings, their tireless pursuit of data wrangling, and the time they devoted to assembling this complex document. I would like to thank Anastacia Lee and Malecka Nachtsheim for their support throughout this project. Finally, I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to Dr. Yunhee Bae, who created many of the data figures in this document and served as our data engineer. I sincerely thank all our community partners for their engagement and participation. Their voices and lived experiences are critical in developing practical and lasting solutions to improve the quality of life for residents of Spokane County.

Best Regards

Anna Tresidder, Ph.D.

Vice President, Office of Research and Evaluation

Excelsior Wellness, Office of Research and Evaluation

This project was funded by the generous support of the Office of Firearm Safety and Violence Prevention—Community Safety Unit within the Washington State Department of Commerce.

The Office of Research and Evaluation and Excelsior Wellness extend their sincere gratitude to all community partners who generously contributed their time, expertise, and valuable insights to the development of this community needs assessment report. We value your collaboration and eagerly look forward to our continued joint efforts in addressing the identified areas of concern and creating sustainable solutions that uplift and empower our community.

We strive to ensure that this report reflects the voices and concerns of our esteemed community partners, whose contributions have been instrumental in its development.

This report was authored by:

• Andrew Ogwang, MPH, FRSPH — Public Health Systems Administrator

• Lauren Dodier, BA — Research Assistant

With support from:

• Anna Tresidder, MPH, PhD — Vice President, Research and Evaluation

• Yunhee Bae, PhD –Senior Data Scientist

• Malecka Nachtsheim, M.Ed—Research Assistant

County Data Resource Partnerships:

• Spokane Regional Health District

• Spokane County Sheriff’s Office

• Washington State Department of Health, Office of Healthy and Safe Communities

• Washington Emergency Medical Services Information System

Excelsior Wellness is an integrated health and wellness organization dedicated to empowering individuals and families in the Spokane community. We offer a wide range of services that provide physical, mental, and behavioral health, ensuring holistic care for all those seeking care. Our team of compassionate professionals works collaboratively to provide personalized care, fostering wellness and resilience in every stage of life.

We believe that every person has the potential to be safer, stronger, and more satisfied in thelivesthey lead. Tothatend, weprovideequitableaccess to care, respect, and hope as we empower them to live and stay well.

Our vision is to serve a broad base of individuals and families with the primary aim of identifying goals and making positive steps towards accomplishing them. In ourcommunity, weare advocatesand hold fastto the belief that children and families have the potential to be safer, stronger, and more satisfied in the lives they lead.

This Spokane County Firearm Violence Prevention Community Needs Assessment (CNA) presents a comprehensive analysis of firearm-relatedincidents, deaths, injuries, andcommunity perspectives to inform evidence-based prevention strategies. Thisassessment utilizes extensive mixed-methods research, including quantitative and qualitative analyses from multiple sources. It highlights critical areas that need active intervention for Spokane County’s 553,170 residents.

From 2018-2022, Spokane County experienced 348 firearm-related deaths, representing a rate of 13.1 deaths per 100,000 residents. Firearms consistently caused the highest number of deaths in the county, with approximately 31-34 annual deaths from 2017 to June 2024. The analysis illustrates that suicides significantly outnumber homicides, with suicide rates peaking at around 54 deaths per 100,000 people in 2017. This assessment revealed significant racial disparities in firearm violence, with Black residents experiencing the highest rates of both homicides (15.1 per 100,000) and suicides (12.37 per 100,000), followed by Hispanic residents with homicide rates of 3.9 per 100,000. Males consistently exhibited substantially higher rates of firearm-related deaths compared to females, with male suicide rates reaching 16.54 per 100,000 from 2018-2022, while female rates remained around 3.5 per 100,000.

Youth firearm violence data shows trends with death rates for ages 0-24 in Spokane County generally trending higher than statewide rates, ranging from 5.8 to 10.9 per 100,000 people compared to Washington State’s 4.9 to 7.2 per 100,000 people. People aged 18-24 experienced the highest death rates, with 589 deaths at a rate of 17.3 per 100,000 people statewide and 43 deaths at a rate of 14.6 per 100,000 people in Spokane County from 2018 through 2022. The highest death counts for youth occurred in home settings, with 458 deaths statewide (50.2%) and 52 deaths in Spokane County (76.5%).

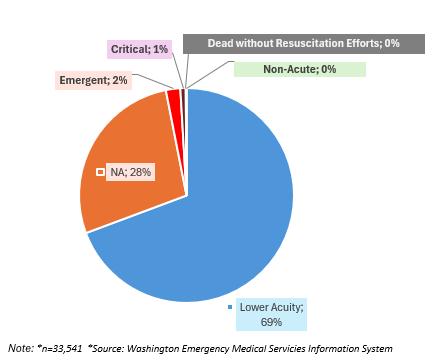

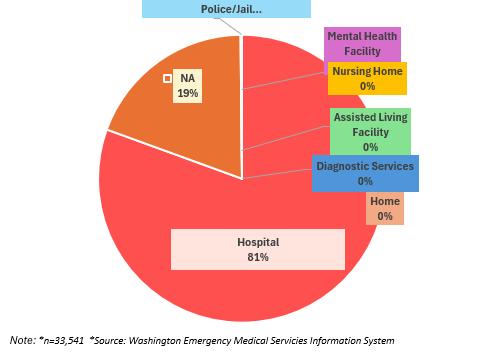

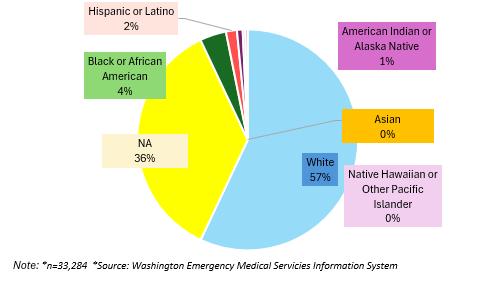

Emergency Medical Services data from 2018-2024 provides additional context, showing that 69% of firearm-related incidents were classified as lower acuity cases, while 2% required emergency response and 1% were critical cases. Approximately 81% of incidents resulted in hospital transport. The hospitalization data demonstrates notable racial disparities, with White Non-Hispanic patients showing the highest overall numbers but disproportionate rates affecting minority communities.

Through extensive community engagement, community partners identified mental health as the primary concern, with 82% of community partners ranking it as the top priority. They highlighted limited access to services and long waitlists, particularly for Medicare and Medicaid recipients. Suicide prevention emerged as the second highest priority at 71%, with community members emphasizing the need for improved

prevention strategies, including safe storage protocols and mental health support. Domestic violence ranked third at 53%, with community partners calling for enhanced support services and firearm relinquishment enforcement. Community members also expressed significant concern about school shootings and their impact on youth mental health.

Based on these findings, the CNA highlights four primary areas for intervention:

• Expanding access to behavioral health services including mental health, suicide prevention, and substance use treatment

• Implementing comprehensive safe storage protocols with education and access to safety devices

• Strengthening domestic violence prevention through enhanced firearm relinquishment processes and extreme risk protection orders

• Developing targeted educational initiatives and community-based violence prevention programs

These evidence-based recommendations will inform the development of a comprehensive Community Firearm Violence Strategic Action Plan in 2025, focusing on implementing strategies to reduce firearm violence and enhance community safety in Spokane County.

This assessment represents a crucial first step in understanding and addressing firearm violence through a data-driven, community-informed approach. The findings highlight the complex intersection of mental health, social factors, and access to firearms, emphasizing the need for collaborative, multi-faceted solutions to create lasting positive changes in community safety and well-being.

irearm violence is a serious public health crisis in the United States with devastating impacts on individuals, families, and communities. In June 2024, the U.S. Surgeon General declared an advisory on firearm violence.1 This advisory aimed to raise national awareness and mobilize a whole-of-society response to address this public health crisis. In 2022, over 48,000 people died from firearm-related injuries in the United States, with firearm suicides reaching the highest rate since 1968 2.3 . According to the American Public Health Association, the United States has a firearm homicide rate of 4.5 to 11 times higher than comparable high-income countries 4 . Firearm-related injuries are now the leading cause of death for children and adolescents. 5 Beyond fatalities, firearm violence causes lasting trauma, with 58% of American adults or their family members having experienced gun violence in their lifetime. 6 The economic cost is also substantial, estimated at $557 billion annually. 7 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that public health approaches to prevention should focus on addressing the risk factors (needs of people at greatest risk), promoting safe storage practices, and implementing evidence-based policies and programs to reduce firearm violence.8

Firearm violence the use of firearms to cause harm, often used interchangeably with “gun violence” describes both injuries and deaths from the use of firearms. A firearm is defined as any weapon that uses explosive force to discharge a projectile, including handguns, rifles, and shotguns. See Figure 1 below.

Source: History. (2023). Firearms. https://www.History.Com/Topics/Inventions/Firearms.

1 U.S. Surgeon General. (2024). Firearm Violence: A Public Health Crisis in America. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/firearm-violence-advisory.pdf

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Fast Facts: Firearm Injury and Death. Firearm Injury and Death Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/firearm-violence/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

3 Friar, N. W., MPH, Merrill-Francis, M., PhD, Parker, E. M., PhD, Siordia, C., PhD, & Simon, T. R., PhD. (2024) Firearm Storage Behaviors Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Eight States, 2021–2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 524–529.

4 American Public Health Association (APHA). (n.d.). Gun Violence Prevention Fact Sheet. In https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/gun-violence. American Public Health Association.

5 Goldstick, J. E., Cunningham, R. M., & Carter, P. M. (2022). Current Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 386(20), 1955–1956. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2201761

6 Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. (2024). When the Shooting Stops: The Impact of Gun Violence on Survivors in America. Everytown Research & Policy. https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-impact-of-gun-violence-on-survivors-in-america/

7 Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. (2024). The Economic Cost of Gun Violence. Everytown Research & Policy. https://everytownresearch.org/report/the-economic-cost-of-gun-violence/

8 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Preventing Firearm Injury and Death. CDC Firearm Injury and Death Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/firearm-violence/prevention/index.html

9 Kena, G., Ph. D., & Truman, J. L., Ph. D. (2022). Trends and Patterns in Firearm Violence, 1993–2018. In Special Report (NCJ 251663). https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/tpfv9318.pdf

In addressing firearm violence in Spokane County, we used a public health approach to violence prevention. A public health approach is a comprehensive strategy that focuses on improving the entire population’s health, safety, and well-being. It aims to provide maximum benefits for the largest number of people by applying scientific methods to prevent violence. This approach utilizes a four-step process rooted in public health to address and mitigate violence.10

The CDC’s public health approach has been adopted and used to provide guidance to Spokane County’s firearm violence prevention through four systematic steps:

Figure 2: A Public Health Approach to Firearm Violence Prevention

DefineandMonitor theProblem By collecting local data on firearm incidents, demographics, and trends.

1

4 Assure Widespread Adoption

IdentifyRiskand Protective Factors Specific to Spokane communities through data analysis and community engagement.

2

3 Through policy advocacy, community partnerships, and program evaluation.

DevelopandTest Prevention Strategies By implementing evidence-basedinterventions tailored to local needs.

The Spokane County assessment systematically collected data, identified risk factors, gathered community perspectives, anddeveloped evidence-basedstrategies following a comprehensive public health framework. 10 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). About The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention. Violence Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/violence-prevention/about/about-the-public-health-approach-to-violence-prevention.html

The social-ecological model (SEM) provides a comprehensive framework for addressing firearm violence prevention at multiple levels of society. According to the CDC, interacting factors are considered at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels.11 The SEM recognizes that violence prevention requires addressing factors at all levels, not just individual behavior.

Source: CDC. (2024). About Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violence-prevention/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html

The needs assessment addressedfirearms violence prevention through individual mental health, relationship dynamics, community collaboration, and societal factors-examining risk at every ecological level:

AttheIndividuallevel: By examining personal factors like mental health access barriers, substance use treatment needs, suicide risk factors, firearm safety education, and access to firearms.

AttheRelationshiplevel: Familysupportprograms andpeermentorshipinitiatives shouldbeestablishedat the relationship level through different organizations.

AttheCommunitylevel: Neighborhood watch programs (bystander awareness), school safety measures, local firearm storage programs, healthcare-community partnerships, and collaboration between law enforcement and community organizations should be strengthened through town hall meetings and coalitions.

At the Societal level: Supporting state and local policy initiatives like the WA state law initiative I-1639, city ordinance Gun Violence Prevention for Safer Spokane, conducting public education campaigns, and working with media outlets for responsible reporting of firearm incidents.

This approach aligns with including a broadarray of community partners who emphasize addressing upstream factors and immediate interventions.

11 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). About Violence Prevention. Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violence-prevention/about/index.html

Excelsior Wellness was awarded a grant by the Washington State Department of Commerce’s Office of Firearm Safety and Violence Prevention Community Safety Unit in December 2023 to facilitate community participation in addressing firearm violence in Spokane County. The project’s ultimate goal is to convene and facilitate Spokane County organizations interested in reducing violence to implement evidence-based strategies for firearm violence reduction, thereby developing a Community Violence Strategic Action Plan.

Excelsior Wellness utilized the public health expertise within their Office of Research and Evaluation (ORE) to collect and analyze data to define Spokane County communities’ most prominent areas of need related to firearm violence through data-driven initiatives. The ORE convened a Firearm Violence Prevention Planning Team (hereafter referred to as “community partners”) of representatives from diverse community organizations and concerned community members throughout Spokane County. The goal was to collaborate on producing project deliverables, including a Community Needs Assessment (CNA) in 2024 and a Community Violence Strategic Action Plan (SAP) in 2025. This CNA will inform the SAP by using evidence to demonstrate the root causes and impacts of firearm violence in the community and identify service gaps and barriers, which, if addressed using the SAP, will organize community resources to lower overall rates of firearm violence in Spokane County.

This list includes diverse community partners from law enforcement, healthcare, public health, mental health, domestic violence prevention, education, and community advocacy organizations. These multidisciplinary partners were essential contributors to the Firearm Violence Prevention Community Needs Assessment, providing critical expertise, community perspectives, and collaborative input to develop comprehensive understanding and solutions for firearm violence in Spokane County.

AnastaciaLee,MPH, Board Member, Asians for Collective Liberation in Spokane (ACLS)

Salliejo Evers, Regional Prevention Coordinator, Department of Homeland Security – CP3

Taffy Hunter, MSHS, HS-BCP, Interim Executive Director, Spokane Regional Domestic Violence Coalition

Melody Youker, Community Outreach, Prevent Suicide Spokane Coalition

BobLutz,MD,MPH,PublicHealth Physician

Sabrina Votava, Founder and Executive Director, Fail Safe For Life

Michael Van Dyke, DO, Pediatric Intensivist, Sacred Heart Children’s Hospital / Washington Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics

PaulDillon, CityCouncil Member, District 2, Spokane City Council

RobinBall,Retired, Sharp Shooting Indoor Range & Gun Shop

Rick Scott, Community Safety Partnerships Coordinator, GSSAC’s Prevention Center

Khris Thompson, Undersheriff, Spokane County Sheriff’s Office

DeniseMcCurdy,MBA,RN, Regional Nurse Manager Trauma Services INWA, Providence Hospital

AngelaSvastisalee, GrantCoordinator, Spokane Regional Domestic Violence Coalition

MiaParker,MPH,Fatality Review and Prevention Coordinator, Spokane Regional Health District

VirginiaRamos,LegislativeAssistant, Spokane City Council

JerrieNewport,LevelIIThreatAssessment Coordinator, North East Washington Educational Service District 101

VeenaSingh,MD,MPH,ChiefMedical Examiner, Spokane County Medical Examiner’s Office

Shayla Maxey, Assistant Program Manager, Carl Maxey Center/ Sandy Williams Justice Center

JohnathanWaldrop,Medical Examiner Operations Manager, Spokane County Medical Examiner’s Office

RumyanaKudeva,DSW,MPH, LICSW, Early Childhood Specialist, Spokane Regional Health District

HeatherWallace, SeniorProgramManager of Equity and Engagement, Better Health Together

Kami LaMoreaux, Violence Prevention Coordinator, Spokane Regional Domestic Violence Coalition

Dr. Deborah Svoboda, MSW, Associate Professor of Social Work, Eastern Washington University

JaredKiehn,Lieutenant, Investigative Division, Spokane County Sheriff

ChiefDavidEllis,SpokaneValleyPolice Department

During the CNA period, the community partners provided valuable feedback regarding where and how to collect data from their respective populations. They helped suggest additional community leaders and members for the focus groups. The community partners served as the ultimate source of feedback for editing this report, ensuring that the presented data represented diverse voices. Once the community partners approved the CNA in its final form it was shared with the community via paper and virtual options. Notably, the digital version of this document is more comprehensive and includes all supplementary information.

The work of the community partners and ORE will be shared with the Spokane County community at the 2025 Firearm Violence Prevention Conference to engage organizations with a shared goal and values from across the region in this work.

The methodology employed in this project reflects a systematic approach to community engagement, data collection, and collaborative planning across clearly defined phases. Beginning in January 2024, the project initiated quantitative data collection and established relationships with community partners to form a planning team. Over subsequent months, the team facilitated meetings, recruited additional partners, and conducted focus groups, culminating in the drafting and refining of the CNA with input from community partners.

JANUARY-MARCH2024

• Research: quantitative data collection

• Identified community partnersfor planning team and focus groups

• Second planning team meeting occurred in June with 13 participants

• Recruited 3 new community partners

•Created SharePoint for participants' ease of accesstoproject filesandresearch/resource submissions

• Identified focus group population

• First focusgroup meeting occurred in July with 13 participants

• Recruited 2 new community partners

OCTOBER 2024

• Complete initial draft of CNA

DECEMBER2024

• Produce final CNA

• Group assessment survev

APRIL-MAY2024

• Recruited organizations for planning team

• Scheduled first planning team meeting

• First planning team meeting occurred in May with 12 participants

• 8 Additional community partners identified through attendee referrals

• Second focusgroup meeting occurred in August with 9 participants

• Recruited 5 new community partners

• Began drafting CNA in September

NOVEMBER2024

• Community partners provide feedback on initial CNA draft

Mixed-methods research combines and integrates both qualitative and quantitative data in a single study.12 Qualitatively, this report includes listening sessions and focus group data to identify common themes and highlight areas of need for firearm violence prevention. Facilitators and scribes captured detailed notes, recordings, and transcripts of the listening sessions and focus groups, which were later analyzed using the qualitative analysis software tool NVivo. Quantitatively, this report incorporates survey data, peer reviewed research, and statistical analyses of relevant data metrics to provide measurable evidence and a broader context to the community partners’ experiences. The findings from both data types are presented individually and in tandem to highlight the large scope of this work.

The diagram in Figure 4 illustrates how we organized and categorized our qualitative findings:

This section describes how the project gathered information on firearm violence in Spokane County through surveys, focus groups, and data-sharing agreements with various organizations in addition to the limitations we faced. The purpose of this data is to gain insight into the impact of firearm violence and investigate viable harm-reduction strategies by collecting both professional insights and personal experiences from community partners and members.

Kajamaa, A., & Mattick, K. (2020). How

A series of surveys (see Appendix C: Community Survey and Appendix D: Professional Survey) were conducted by gaining insight into the more significant Spokane population’s attitudes and beliefs and those of our focus group respondents. The professional and community surveys were distributed via “snowballing” through community partners, posts on LinkedIn and Reddit (r/Spokane), and flyers containing QR codes posted around Excelsior’s main campus and the SRHD Community Health Department. Both surveys aimed to gain insight into the impact of firearm violence in Spokane County to investigate viable harmreduction strategies later.

The professional survey was designed for professionals who are concerned for or work with people impacted by firearm violence. It asks questions such as “What types of firearm violence does your work engage with?” and “What are some of the main challenges or barriers faced by you…or your organization to reducing firearm violence?” to learn how communities have been affected by violence and investigate potential solutions. The community survey was open to all Spokane County residents to report personal experiences with firearm violence, including how it has impacted friends or family. Professionals were allowed to respond to one or both of the surveys. Participants in the community violence survey (whether or not they reported experiencing violence) were provided with resources such as the national domestic violence hotline number, regional 24-hour crisis line, and the SRDVC community advocate’s contact information.

The activation period for both surveys began on June 24, 2024, and ended on September 25, 2024, allowing participants three months to submit their responses.

The project’s work group was formed through networking and outreach communications and was nearly identical to the Planning Team. The Program Director initially contacted 61 community organizations in fields related to the project’s target issues and formed a contact list of 15 community partners interested in joining the project’s planning team. Outreach began with organizations such as Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD) and law enforcement. Interested parties were encouraged to invite colleagues and professionals in related fields to join the work group. This group evolved as members navigated factors impacting their ability to participate; however, the work group had consistently strong participation as word spread of the project and additional community partners joined. The work group met four times between May and August.

The focus groups mainly consisted of the project’s pre-existing work group members and a few additional interested community partners. The first of two focus group meetings explored the topics of suicide, mental health, domestic violence, determinants of health, and substance use. In the second meeting, members returned to discuss mass and school shootings, community safety, news/media, public discourse, and safe storage options. Focus group participants were allowed to complete a follow-up survey after the meetings to provide further comments on each topic.

From July to August 2024, two focus group meetings were conducted at the Spokane Public Library— Hillyard to better understand the concerns and key findings of firearm violence in Spokane County. The July focus group meeting had 13 community partners in attendance, both in person and virtually. The group was subdivided into two, with different facilitators guiding the discussions using a formal interview guide (Appendix B: Community Partner Listening Session and Focus Group Questions). The August focus group met to finalize the remaining topics that were not completed in the first meeting, and the group used a formal interview guide (Appendix B: Community Partner Listening Session and Focus Group Questions).

The focus groups provided an opportunity for in-depth discussions on the topics from the listening sessions about their communities.

The facilitators used techniques to ensure that all community partners could participate in the discussion, which lasted about 120 minutes (about 2 hours).

In addition to data collected from public online sources, Excelsior entered into data-sharing agreements with the Washington Department of Health (DOH), the Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD), Spokane County Sheriff’s Office (SCSO), and the Washington Emergency Medical Services Information System (WEMSIS).

The Community Needs Assessment utilized current secondary datasets while engaging community partners to identify relevant topics and data sources for understanding firearm violence in Spokane County. Access to the WEMSIS data was delayed, and the medical examiner’s office data was unavailable for this report. The available data spans from 2002 to June 2024 and represents the region’s first comprehensive analysis of firearm violence. The assessment relied on non-partisan, routinely collected data, such as crime statistics, mortality rates, injuries, and hospitalizations. The demographic data collected from these sources categorized gender in binary terms (male and female), which limits our understanding of how firearm violence affects individuals across the full spectrum of gender identities. National data shows that 2020 had the highest firearm violence rates in two decades13 , with many cities experiencing increased violent crime14 , though analyzing 2020’s specific patterns was beyond this study’s scope. These limitations should be carefully considered when concluding the available data.

13Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. (2022). A Year in Review: 2020 Gun Deaths in the U.S. In https://publichealth.jhu.edu/gun-violence-solutions

14Braga, Anthony A., and Philip J. Cook, Policing Gun Violence: Strategic Reforms for Controlling Our Most Pressing Crime Problem (New York, 2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Jan. 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199929283.001.0001

This needs assessment explores firearm violence in Spokane County using various data sources, including mortality records, hospital data, emergency services data, and crime statistics. The analysis presents findings using standardized rates per 100,000 to facilitate meaningful comparisons across geographic areas, demographic groups, and time periods within Spokane County. Additionally, for each topic area (deaths, injuries, crimes, and EMS events), the assessment provides overall counts followed by detailed breakdowns of geographic distributions, demographics, and circumstances specific to Spokane County. Finally, the standardized rates are calculated and presented at various levels, including state and county-wide annual rates, multi-year average rates, geographic area-specific rates, and demographic-specific rates, which analyze disparities by race, gender, and age.

Population Density

Spokane County, Washington’s estimated 2024 population is 553,170 with a growth rate of 0.31% in the past year according to the most recent United States census data15 . Spokane County is the 4th largest county in Washington State.16

Race, Ethnicity, and Firearm Violence

Spokane County racial demographics17

• White: 80.96%

• Black orAfrican American:2.69%

• American Indian and Alaska Native: 1.31%

• Asian: 2.63%

Racial demographics and firearm violence:18

Washington

• NativeHawaiianandotherPacific Islander: 0.81%

• Some other race: 2.06%

• Multiracial: 9.29%

• Black people are2x morelikelythanwhitepeopleto die byfirearms

• White people are2x more likely than Black peopleto die by firearm suicide

• Black people are 9x more likely than white people to die by firearm homicide

National

• Black people are 2.7x more likely than white people to die by firearms

• White people are2x more likely than Black peopleto die by firearm suicide

• Black people are 12x more likely than white people to die by firearm homicide

Spokane County

• Total deaths 2018-2022= 348

• Rate per 100,000= 13.1

• Population= 541,125

15 United States Census Bureau. (2025). County Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2024. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-counties-total.html

16 Spokane County, Washington Population 2024. (n.d.). https://worldpopulationreview.com/uscounties/washington/spokane-county

17 Research, N. (2025). Spokane, WA Population by race & ethnicity. https://www.neilsbera.com/insiahts/spokane-wa-population-bv-race/

18 EveryStat - EveryStat.org. (n.d.). EveryStat.Org. https://everystat.org/#Washington|

As illustrated in Figure 5, from 2017 to June 2024, firearms caused the highest number of deaths in Spokane County, with approximately 31-34 death counts annually, with similar numbers across homicides, deceased, and categories of suspects/arrests. Motor vehicles were the second leading cause with about 12-13 death counts, followed by knife-related deaths at roughly 9-10 death counts. Approximately eight deaths occurred at various physical locations, including residences, unknown sites, jails, drug stores, doctor’s offices, hospitals, bars, nightclubs, and motels or hotels. Other causes showed lower frequencies, with “Other” atabout three deaths, drugs atapproximately threedeaths, andblunt objects causing about two deaths per year.

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than do does not show but rate shows calculated

*n=69

*Source: Spokane County Sheriff's Office

Figure 6 shows the average annual suicide deaths in Spokane County from 2004 to 2022. The data includes various categories, such as firearms, suffocation, poisoning, and other rates per 100,000 people. The data indicates fluctuating trends over the years, with firearms consistently accounting for a significant portion of death count cases in Spokane County.

100

0 0

-SumofCount

- Sum of Count

- Sum of Count Other-Sum ofCount Other - Average of Rate

- Average of Rate Suffocation-Average of Rate Firearm-Average of Rate

Note: *Population Multiplier: per100.000: Average across categories. *Count Sum across categories; Less than 10 shows neithercount nor rate. *n=1,570 * Data source: Spokane Regional Health District

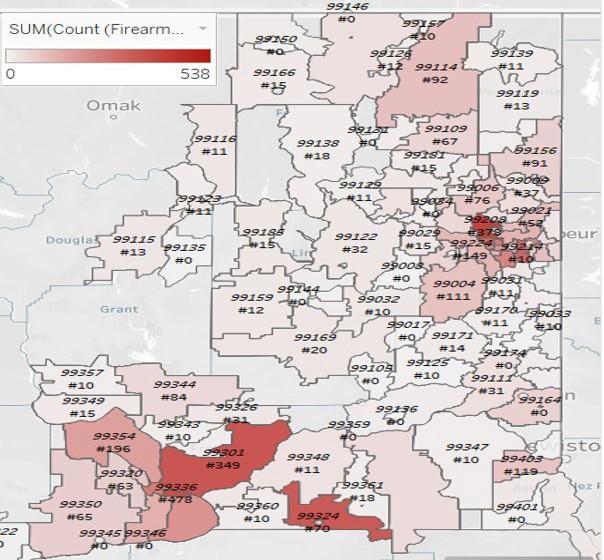

Geography of Firearm-Related Deaths per 100,000 People

The heat map depicted in Figure 4 displays all firearm injuries by ZIP code in Spokane County and surrounding counties from 2016 to 2023. The map uses varying shades of red to represent the concentration of incidents, with darker areas indicating a higher number of firearm injuries in specific ZIP codes. The numbers (#) displayed within each ZIP code region indicate the total count of firearm injuries reported in that specific area.

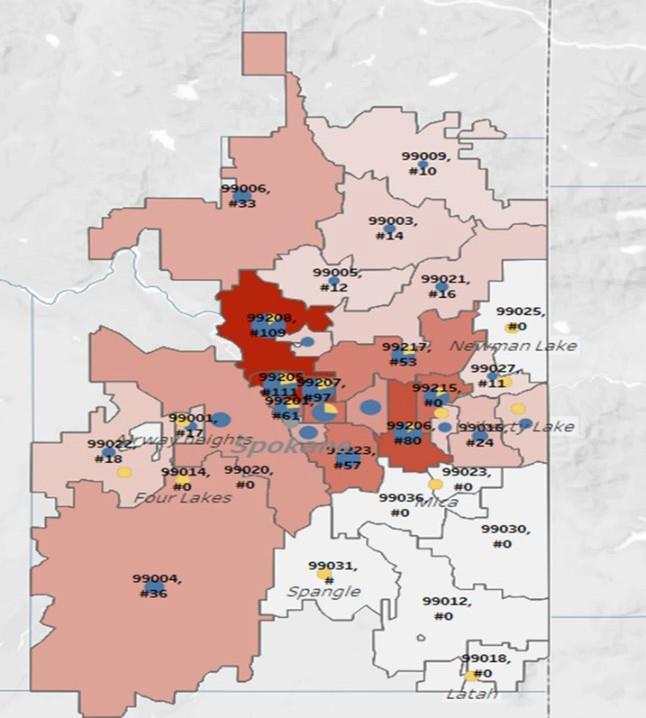

The map in Figure 8 shows firearm-related homicide and suicide counts by ZIP code in Spokane County (2013-2022), with darker red areas indicating higher concentrations of up to 111 incidents. Yellow dots represent assaults, while blue dots indicate self-inflicted injuries, showing clustering patterns across different ZIP codes.

n=1,063 Data source: Spokane Regional Health District

The data below highlights firearm-related deaths in Spokane County by race and ethnicity. Figure 9 reveals significant racial disparities from 2018 to 2022. The “Black Only Non-Hispanic” population experiences the highest rates of both homicides (15.1 per 100,000) and suicides (12.37 per 100,000). Followed by the “Hispanic” population, which has a homicide rate of 3.9 per 100,000. Additionally, “Native Americans and Pacific Islanders” report the highest suicide rates at 8.62 per 100,000. Meanwhile, “White Only NonHispanic” populations have the highest total number of firearm-related death counts (228) and elevated suicide rates.

Figure 9: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Race/Ethnicity in Spokane County from 2018-2022

Suicide - Sum of Count

Homicide - Sum of Count

Suicide-AverageofAge-AdjustedRate(per100,000)

Homicide - Average of Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death date is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=287

*Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VDRS)

Figure 10 presents trends from 2004 to 2024 in five-year intervals, demonstrating a general increase in overall firearm deaths while suicides have consistently outnumbered homicides over the last five years (2018-2022).

10: Average Annual Firearm-Related Death by All Races/Ethnicities in Spokane County

Suicide - Sum of Count Homicide-SumofCount

Suicide - Average of Age - Adjusted Rate (per 100,000)

Homicide -Average of Age -AdjustedRate (per 100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated. *n=1,052

"Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VDRS)

The following graphs show firearm-related deaths in Spokane County, comparing age groups and types of death (suicide vs. homicide). Figure 11 provides an age-group overview from 2018-2022, with Figure 12 and Figure 13 focusing on the 25-44 and 65+ age groups from 2004-2024. These differences might be attributed to increased exposure to high-risk situations, social dynamics, and lifestyle differences between working-age adults and seniors.

Suicide-SumofCount

Homicide -Sum of Count

Suicide-AverageofAge-AdjustedRate(per100,000)

Homicide -Average of Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000)

Note: *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

* n=315

*Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VDRS)

Figure 12 shows the 25-44 age group experiencing consistently higher rates of both suicide and homicide, with suicide rates peaking at 78 death count in 2018-2022.

Figure 12: Average

Figure 13 reveals that the 65+ age group has primarily suicide-relateddeaths (peaking at 73 death counts in 2018-2022) with nearly negligible homicide rates.

Figure

Figure 14 illustrates the average number of firearm-related deaths by suicide and homicide in Spokane County from 2004 to 2024. Figure 15 and Figure 16 show a breakdown by gender. Males exhibit significantly higher rates of both firearm-related suicides and homicides compared to females. From 2018 through 2022, there have been 233 male suicide death counts by firearms at a rate of 16.54 per 100,000 people, whereas female suicides reached a high of approximately 45 death counts at a rate of 3.5 per 100,000 people from 2014 through 2018. This substantial gender disparity may be attributed to factors such as higher firearm ownership rates among males19 , different chosen methods for suicide attempts, and varying rates of seeking mental health support between genders.20

Figure 14: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Gender in Spokane County from 2004-2024, Categorized by 5-Year Groups

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated. *n=1,130

*Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VORS)

19 Mitchell, T., & Mitchell, T. (2024). The demographics of gun ownership. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/06/22/the-demographics-of-gun-ownership/ 20 Griffith, D. (2024). Men and mental health: What are we missing? AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news/men-and-mental-health-what-are-we-missing

*n=124

*Source:

Figure 17 and Figure 18 show firearm-related deaths by homicides and suicides in Spokane County from 2004 through 2024 by gender. Figure 17 shows homicides increasing over time, with rates rising from 2.0 4.2 per 100,000 (22–52 death counts annually) for males from 2004 through 2022 and remaining relatively stable at around 0.6 per 100,000 for females.

Figure 17: Average Annual Firearm-Related Homicides by Gender in Spokane County from 2004-2024, Categorized by 5-Year Groups

-Sum of Count

- Sum of Count Female - Average ofAge-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000) Male-AverageofAge-AdjustedRate(per100,000)

Note:

Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-DRS)

Figure 18 depicts suicides, showing significantly higher rates among males (ranging from 15.3 16.5 per 100,000)compared to females (around1.7–3.5 per 100,000 people), withmalesuicides reachinga peakof 235 death counts from 2018 through 2022. Figure 18: Average Annual Firearm-Related Suicides by Gender

Figure 19 illustrates the average number of firearm-related death rates per 100,000 people over a ten-year period (2004-2024) for youth 0-24 in Spokane County compared to the statewide rates for Washington State. The rates for Spokane County, which range from 5.8 to 10.9 per 100,000 people, generally trend higher than those for Washington State, which range from 4.9 to 7.2 per 100,000. The most significant difference occurred around the years 2016-2017, when Spokane County reached approximately 9.9 per 100,000, while the statewide rate was closer to 5.9 per 100,000. This represents a difference of about four deaths per 100,000 people during that peak period.

Spokane County - Sum of Court Statewide-SumofCount

SpokaneCounty-AverageofAge-SpecificRate(per100,000)

Statewide - Average of Age-Specific Rate (per 100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=2,606

*Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VDRS)

Figures 20 – 21 illustrate the average number of firearm-related deaths and average rates per 100,000 people for specific age groups in Spokane County and Washington State over a ten-year period from 20042024. Figure 20 indicates that people aged 18-24 experienced the highest death rates, with 589 deaths at a rate of 17.3 statewide and 43 deaths at a rate of 14.6 in Spokane County from 2018 through 2022.

Figure 20: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Age Group for Ages 0-24 in

Spokane County - Sumof Court Statewide - Sum of Count

Spokane County - Average of Age-Specific Rate (per 100,000)

Statewide-AverageofAge-SpecificRate(per100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count:

Figure 21 presents trends from 2004 - 2024 for the 18-24 age group, showing that statewide rates consistently exceed those of Spokane County, peaking at 17.3 per 100,000 (589 death counts from 2018 - 2022).

Figure 21: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Age Group (18-24) in Spokane County Compared to Washington State from 2004-2024, Categorized by 5-Year Groups

Spokane County - Sum of Court Statewide - Sum of Count

County - Averageof Age-Specific Rate (per100,000) Statewide-AverageofAge-SpecificRate(per100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated. *n=2,211 *Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-DRS)

Figure 22 shows that from 2018 - 2022, the average male firearm-related death rates experienced a significant increase, rising from 6.9 to 12.1 per 100,000 people. During this five-year period, the number of deaths peaked at 54. In contrast, female firearm-relateddeath rates remained relatively low, at 1.2 per 100,000 people.

Figure 22: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Gender for Age Group 0-24 years in Spokane County from 2004-2024, Categorized by 5-Year Groups

Female -Sum of Count Male - Sum of Count

Female - Average of Age-Specific Rate (per 100,000)

Male-AverageofAge-SpecificRate(per100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=165

*Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-DRS)

Figure 23 compares the average firearm-related deaths and percentages among people aged 0-24 in Spokane County and Washington State from 2018 through 2023, categorized by the location of the incidents.Thehighestdeathcountsoccurredinthe “Home” category,with 458 deaths statewide (50.2%)and 52 deaths in Spokane County (76.5%). Additionally, there were 181 deaths in the “Other specified places” category, accounting for 19.8% statewide. Both areas show a declining trend in deaths when considering other locations, such as streets/highways and schools/institutions.

23: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Location for Ages 0-24 years in Spokane County Compared to Washington State from 2018-2023

AverageofAge-SpecificRate(per100,000)

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=955 *Source: Washington State Violent Death

System (WA-DRS)

Figure 24 presents a comparison of average annual firearm-related deaths by race and ethnicity for people aged 0-24 in Spokane County versus Washington State from 2018 to 2022. The highest death rate is observed among Black and Non-Hispanic people, with rates of 26.9 per 100,000 in Spokane County and 21.9 per 100,000 statewide. Additionally, American Indian/Alaskan Native and Hispanics exhibit higher death rates compared to White and Asian Only (Non-Hispanic). However, White Only (Non-Hispanic) had a higher total death count of 354; their rates were lower compared to the other racial and ethnic groups.

Figure 24: Average Annual Firearm-Related Deaths by Race/Ethnicity for Ages 0-24 years in Spokane County Compared to Washington State from 2018-2022

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=788 *Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-DRS)

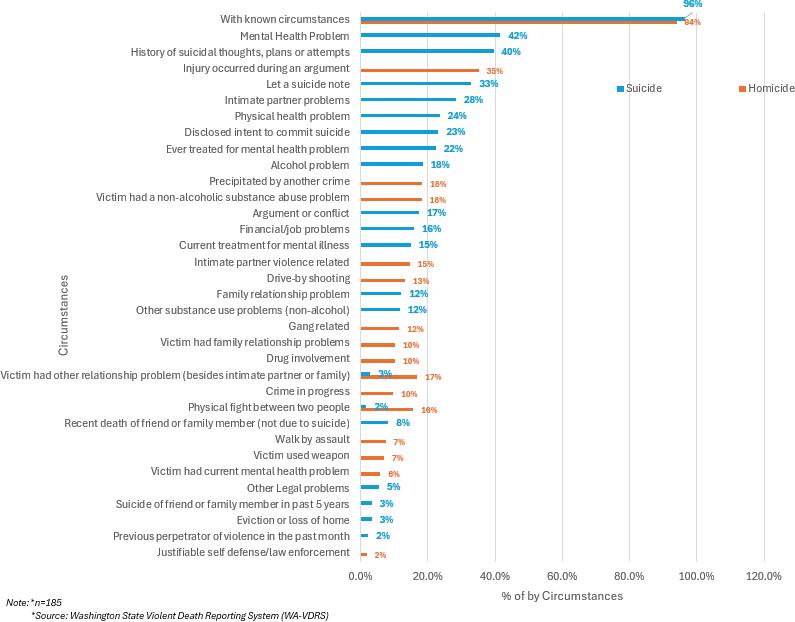

From 2018-2022, the average annual firearm-related deaths in Washington State shows suicide (96%) significantly outweighing homicide (94%) as the primary cause with known circumstances. Mental health problems (42%) anda history ofsuicidal thoughts, plans, or attempts (40%) are the most common circumstances for suicides, while injury that occurred during an argument (35%) is the leading factor for homicides, as shown in Figure 25.

Figure 26 shows the average annual firearm-related death circumstances by gun ownership from 20182022. The “Unknown” category shows the highest percentage, increasing from 67.9% in 2020 to 79.2% in 2021 and then declining. “Shooter” declined from 21% in 2018 to 9.3% in 2022. Other categories like “Friend/Acquaintance” and “Parent” remained relatively stable at lower percentages.

Figure 26: Average Annual Firearm-Related Death Circumstances by Firearm Ownership in Washington State from 2018 to 2022 per 100,000 People

Spouse / Intimate Partner Friend/Acquaintance

Note: *n=1,130

*Source: WashingtonState Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VORS)

From 2018-2022, data from Washington State in Figure 27 shows the average annual firearm-related deaths by three circumstances: hunting, weapon cleaning, and victims playing with a firearm when discharged. Deaths from victims playing with a gun when discharged dropped significantly from 0.5% to 0.0% from2018 to 2020 and peaked in 2021, while hunting and weapon cleaning deaths remained consistently low, never exceeding 0.1%.

27: Average Annual Firearm-Related Death Circumstances by Firearms from 2018 to 2022 per 100,000 People in Washington State

Victimplaying withgun when discharge WeaponCleaning

Note: *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

Sum across categories; Less than 10does not show butrate shows calculated. *n=15

In Figure 28, between 2018-2022 Washington State’s average annual firearm-related death data reveals that handguns were consistently the predominant type of weapon used, accounting for 75-80% of deaths by circumstances, with a peak of 84.3% in 2020.

28: Average Annual Firearm-Related Death Circumstances by Firearm Type from 2018 to 2022 per 100,000 People in Washington State

Note: *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated *n=30 *Source: Washington State Violent Death Reporting System (WA-VDRS)

Figure 29 highlights youth and school-related death circumstances in Washington State. “Firearm victims with known circumstances” rates were consistently highest (96.2-99.1%) from 2018 to 2021 and dropped in 2022, while other youth and school-related death circumstances remained low. Gang-related deaths showed moderate rates between 21.2-30.8%, peaking in 2020.

Figure 29: Average Annual Firearm-Related Death Rates among Youth and School-Related Incidents from 2018 to 2022 per 100,000 People in Washington State

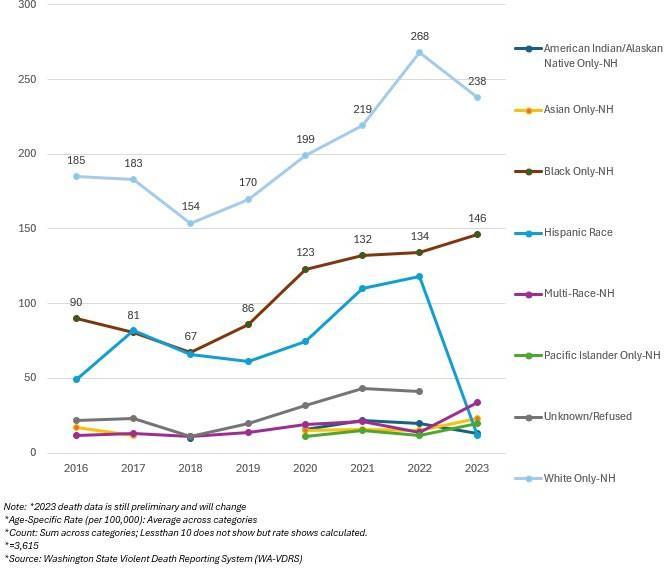

From 2016-2023, the average annual firearm-related hospitalizations in Washington State demonstrated notable racial disparities. White Only Non-Hispanic death counts remained the highest overall, climbing from 154 in 2018 to 268 in 2022. Hispanic death counts saw the most dramatic increase, rising from 49 in 2016 to reaching 118 in 2022 before declining. Black Only Non-Hispanic death counts increased steadily from 67 in 2018 to 146 in 2023, while Asian and Pacific Islander Only Non-Hispanic death counts stayed consistently below 50 per 100,000 people. Refer to Figure 30 for further details.

Figure 30: Average Annual Firearm-Related Hospitalization Cases by Race/Ethnicity from 2016 to 2023 per 100,000 People in Washington State

Suicide

Data from the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office shows a trend in the average annual firearm-related deaths by suicide from 2017 to June 2024. Of note, data from 2024 is still preliminary.

Figure 31 displays cases by age group (15-24, 25-44, 45-64, 64+); the 64+ age group experienced the highest death counts, with 7-19 deaths yearly, peaking at 19 in 2021. The middle-aged adults (25-64) showed fluctuating numbers between 7-19 cases, while the younger age group (15-24) maintained lower but persistent death counts.

Figure 31: Average Annual Firearm-Related Suicide Death Cases by Age Group in Spokane County from 2017 to (June) 2024

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=293

*Source: Spokane County Sheriff's Office

Group=15-24

Group=64+

Group=25-44 NA

Group=45-64

Figure 32 shows that nearly all cases involve adults rather than juveniles, with annual adult cases ranging from 24-45 and minimal juvenile cases (0-3).

Figure 32: Average Annual Firearm-Related Suicide Death Cases by Adult/Juvenile in Spokane County from 2017 to (June) 2024

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change *Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

From 2017-2024, data in Figure 33 shows varying patterns of firearm-related homicides across age groups in Spokane County for both victims and suspects. The highest victim counts appear in the age groups 25-44 and 45-64, with peaks in 2020-2023. For suspects/arrestees, there is a consistent trend in the 18-24 and 25-34 age brackets. The data suggests that while various age groups are affected, the 25-44 demographic is most heavily impacted by firearm-related deaths for both victims and suspects.

AgeGroup-25-44

#Suspect/Arrestee (blank) -#Suspect/Arrestee

Age Group=15-24#Suspect/Arrestee

AgeGroup=64´+ #Suspect/Arrestee

AgeGroup=45-64

#Suspect/Arrestee

AgeGroup=<15 #Suspect/Arrestee

Age Group-25-44- #Victim (blank) - #Victim Age Group=45-64 - #Victim

Age Group=15-24 -#Victim Age Group=64 + #Victim Age Group <15 + #Victim

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100,000): Average across categories

*Count Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated. *n=107

*Source: Spokane County Sheriff's Office

Figure 34 shows the average annual firearm-related suicide death cases in Spokane County by gender from 2017 to June 2024. Males consistently account for the majority of cases, with annual numbers ranging from 20-37 death counts, while female death count cases range from 3-9 per year.

Note: *2023 & 2024 death data is still preliminary and will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=293

*Source: Spokane County Sheriff's Office

In Figure 35, from 2017 to 2024 homicide cases in Spokane County showed higher rates for male suspects and victims compared to females. The number of cases peaked between 2019 and 2022, with 10 incidents involving males, followed by a sharp decline through 2024.

The data from the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office shows the average annual firearm-related suicide and homicide death count cases by race from 2017 to June 2024. Figure 36 shows that suicide death counts were predominantly among the White population, ranging from 22-42 cases annually, followed by the Black population.

Figure 37 shows that homicide death count cases had more variation across racial groups, with a peak of 13 White victims in 2022.

Data from the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office shows the average annual circumstances of suspect firearmrelated death cases from 2018 to 2022. Figure 38 illustrates the manner of death, showing that homicide by firearms consistently represents the highest percentage (peaking at 94% in 2021) followed by cases involving legal intervention.

Figure 38: Average Annual Circumstances of Suspects in Firearm-Related Cases by Manner of Death from 2018 to 2022 in Spokane County

Homicide

Legal intervention (by police orotherauthority)

Undetermined intent

Unintentional Firearm-inflicted byotherperson

Unintentional Firearm-unknown whoinflicted

Note: *Age-Specific Rate (per100.000): Average across categories *Count:Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated. *n=107

*Source: Spokane County Sheriff's Office

Figure 39 shows other circumstances, depicting a general declining trend across multiple categories, with “Contact with law enforcement in the last 12 months” by suspect peaking at around24.1% in 2019, followed by “Attempted suicide by the suspect.”

Figure 39: Average Annual Firearm-Related Cases by Other Circumstances of Suspects from 2018 to 2022 in Spokane County

Alcohol use suspectedby suspect

Attempted

Suicideby Suspect

Had contact with law enforcement inlast12 months

Had contact with law enforcement inlast12 months

Note: *Age-SpecificRate (per 100.000): Average across categories *Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated. *n=107 *Source: Spokane County Sheriff’s Office

From 2018-2022, Spokane County’s firearm-related cases show the category “Relationship Unknown” representing the highest percentage, reaching 60.8% in 2022, followed by “Injured by law enforcement officers.” Other relationships between suspects and victims, including “Acquaintances andcurrent/former partners,” remained relatively stable below 10% throughout the 5 years as shown in Figure 40.

Figure 41 shows that Spokane County’s firearm-related homicides were predominantly concentrated in residential areas, with 35 cases of suspects and 32 cases of victims atresidence/apartment and 20 cases of victims and 21 suspects on highways/roads/alleys between 2017 and June 2024. Public spaces like fields/ woods, hotels/motels, and other places collectively accounted for fewer than 5 cases.

Homicides Deceased

Suspect/Arrestee

Victim

Note: *2023 &2024 death data is still preliminaryand will change

*Age-Specific Rate (per 100.000): Average across categories

*Count: Sum across categories; Less than 10 does not show but rate shows calculated.

*n=70 *Source:Spokane County Sheriff’s Office

From May to June 2024, the Office of Research and Evaluation conducted two listening sessions with diverse community partners at two locations of the Spokane Public Library (Indian Trail and Hillyard). The sessions were organized with an introduction, remarks on the project’s background, and prepared questions (see Appendix B: Community Partner Listening Session and Focus Group Questions). An overview of the current firearm violence data in Spokane County was presented to the community partners by the ORE facilitators.

These meetings were intended to establish an understanding of the community partners’ perspectives on the root causes of firearm violence in the community and identify service gaps and barriers. Topics of interest identified in the first listening session are represented in the “word cloud” in Figure 42. The size of each word correlates with the frequency with which it was mentioned by the community partners.

42: Listening Session Word Cloud

The listening sessions revealed several areas of concern related to firearm violence, including domestic violence, mental health, mass shootings, survivor’s aid, safe storage, social and political determinants of health,gang violence,suicide,andschoolormassshootings.Afteridentifyingthesekey concerns,community partners were invited to complete a survey ranking the topics by level of importance to discuss in the focus groups. A hierarchy pyramid was created to show the percentage of community partners who ranked each topic as highly important to be discussed in the upcoming focus group (Figure 43).

Many community partners (82%) cited Mental Health as the top priority for the focus group discussion, followed by Suicide (71%) and Domestic Violence (53%). School shootings and Substance use were split evenly (41%), while Mass shootings (35%) and Gangviolence (12%) followed.

Six main topics emerged from the work group’s ranking, which informed the types of questions that were posed to the focus group. Between the two focus group meetings, participants discussed suicide, mental health, domestic violence, determinants of health, substance use, andschool/mass shootings. Additional topics of news and social media and public discourse were posed after participants requested a second meeting. The six key concerns and two additional topics are mapped in Figure 44 below. Focus group members’ comments were categorized by these key concerns and are accompanied by supplemental research in the following data presentation.

Figure 44: Qualitative Themes

Mental health was the primary topic that community partners desired to be addressed in the focus group discussion (ranked highly by 82% of participants). The community partners’ discussion on mental health in Spokane County revealed a complex intersection between firearm ownership, healthcare access, and treatment quality.

Community partners expressed concern for rising mental health disorders, especially among youth, with one observation that “there’s so many undiagnosed mental illnesses among youth aged 18-24 and on college campuses.” Abrams (2022) supports this, stating that “By nearly every metric, student mental health is worsening. During the 2020–2021 school year, more than 60% of college students met the criteria for at least one mental health problem, according to the Healthy Minds Study, which collects data from 373 campuses nationwide.”21 This highlights the need for mental health services on college campuses as well as accessible mental health care for non-students of the same age category.

Community partners also mentioned the need for better approaches to firearm control, with one stating, “We shouldn’t ban gun ownership for everyone with a mental illness, but certain conditions should prevent ownership. Total gun bans may further stigmatize mental health, and people may evade help, treatment, or diagnosis because they want to own a gun. Those who own guns don’t want a punitive response for reaching out to get help.” Under federal law, any person attempting to purchase a firearm from a licensed dealer must undergo a background check. The National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) is used to determine if an individual is prohibited from ownership due to certain criminal convictions or subjection to a protective/ restraining order. Current Washington laws and regulations prohibit gun ownership for individuals with a history of mental illness if they have been involuntarily committed for mental health treatment or were found not guilty of a crime by reason of insanity. State law also requires healthcare facilities to report involuntary commitments for mental health treatment to the NICS and local law enforcement agencies; however, under federal law, healthcare providers cannot disclose information regarding mental health status unless the patient poses an imminent threat of harm to themselves or others. Additionally, Washington’s Firearm Protection Order (FPO) law allows family members and law enforcement to petition for an individual’s firearms to be temporarily removed if they pose a significant danger to themselves or others due to mental illness. In most cases, individuals in Washington may petition in court to have their firearm rights restored, but they may remain disqualified under federal law.22, 23, 24, 25 There is a need for the effectiveness of these laws and regulations to be studied. If proven to be ineffective in preventing gun violence perpetrated by individuals with mental health disorders, further restrictions to gun purchase and ownership may be necessary.

21 Abrams, Z. (2022). Student mental health is in crisis. Campuses are rethinking their approach. https://Www.Apa.Org. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/10/mental-health-campus-care

22 Chow, C. (2024). Mental Health and Firearm Ownership in Washington – State Regs Today. https://www.stateregstoday.com/politics/gun-control/mental-health-and-firearm-ownership-in-washington

23 Petition to restore firearm rights. (2024). In Superior Court of Washington (pp. 1-3). https://www.courts.wa.gov/forms/documents/WS%20900_Pt%20to%20Restore%20Firearms%20Rights%202024%2001.pdf

24 Alexander Stoker. (n.d.). Firearms background checks Overview. https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/fact-sheet-firearm-background-check.pdf

25 RCW 9.41.040: Unlawful possession of firearms—Penalties. (n.d.). https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=9.41.040

The community partners also highlighted disparities in care quality and availability, with one participant pointing out a “...huge gap between the level of care the rich and poor can afford. Resources are often not available for the population that needs it most.” This gap emerged as a critical issue, particularly for Medicare and Medicaid recipients. As one community partner noted, “Medicaid patients trying to get mental health treatment face a long waitlist with unreasonable expectations to get off. They must call every day until a bed is available.” On a related note, insurance barriers were discussed extensively, with one insight being that “organizations may have their heart in the right place, but reimbursement rates aren’t sustainable to maintain staffing models and give adequate care.” This highlights a multidimensional deficit in healthcare, where the community’s need for mental health programs is in high demand, but the support necessary for organizations to provide care is lacking. Community partners noted that virtual programming can be effective for those with physical barriers to accessing care (such as transportation), but enrollment capacity of in-person counseling and inpatient treatment programs remains insufficient for the community’s needs.

Finally, community partners stressed the importance of collaborative, family-centered approaches to mental health care, especially for children. One community partner noted, “It takes adjustments to every factor of a person’s life to make a full change. People need support from services before, during, and after an episode of care.” This highlights the need for mental health services to target the family unit rather than just the individual. For children, collaboration between care teams working in and outside of schools could create more effective, well-rounded mental health treatment. As such, it is necessary for educators, school counselors, therapists, and other healthcare service providers to work together and communicate the child’s progress and continuing needs.

Overall, the community partners considered the need for a comprehensive, integrated approach to mental health care that addresses systemic barriers while promoting positive attitudes toward treatment and recovery.

Suicide was the second most important topic that community partners identified for the focus group discussion(rankedhighlyby71% of participants).Thecommunitypartners’discussiononsuicideinSpokane County revealed a complex intersection between lawful gun ownership, safe storage, and education for adults and children.

Community partners expressed concerns for the risk of suicide when firearms are present in the household: “Storing guns loaded with ammunition may increase suicide if impulsivity is involved.” Kellermann et al. (1992) support this claim, stating that, “Ready availability of firearms is associated with an increased risk of suicide in the home. Owners of firearms should weigh their reasons for keeping a gun in the home against the possibility that it might someday be used in a suicide.”26 One community partner highlighted fluctuation in risklevels, with an emphasis on the negative impact the presence of firearms contributes: “Suicide doesn’t occur in isolation; it builds up over time, reaching a peak that eventually deescalates. The risk increases when individuals have access to firearms during emergency situations.” This demonstrates that itis important for suicide risk levels to be assessed, both formally by mental health professionals and informally by friends or family members who may be able to provide timely intervention. The American Public Health Association (APHA) states that, “The most promising evidence-based strategies to reduce access to firearms during a period of high risk are (1) temporary relocation of household firearms away from home when [someone] is at risk for suicide, (2) safe storage at home if relocation is not possible, (3) working with leaders in the gun community to develop and implement messaging about [relocation and safe storage]...27

Several perspectives emerged on how to prevent firearm-related incidents involving children in the household.One partner calledfor a change in legal ownership laws, stating that, “If they can’t buy it, they shouldn’t have access to it even though legally [youth] can be gifted a gun at the age of 18. They can’t carry it, but they can have possession of it in their abode.” Stricterparametersongunownership,suchaseliminatingthe possibility of youth receiving weapons as gifts, may decrease the rate of gun violence perpetrated byyouth.

26 Kellermann, A. L., Rivara, F. P., Somes, G., Reay, D. T., Francisco, J., Banton, J. G., Prodzinski, J., Fligner, C., & Hackman, B. B. (1992). Suicide in the Home in Relation to Gun Ownership. New England Journal of Medicine, 327(7), 467–472. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199208133270705

27 American Public Health Association (APHA). (2018). Reducing Suicides by Firearms. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/28/reducing-suicides-by-firearms

Another community partner emphasized using a multi-layered approach, combining primary prevention through mental health support and family counseling with secondary and tertiary measures like trigger locks: “Often people who have guns in safes don’t realize that kids and others in the household know how to access it. Guns aren’t always safe being locked up. Have you ever tried to hide Christmas presents from your kids? They’ll find them.”

Two community partners strongly advocated safe storage as the most critical element, stressing the importance of parents recognizing its significance: “Too many parents think their kids can’t get to their gunsordon’tknow how touse them, but accessleadsto accidentsorunsuperviseduse.” Thisissupported by Monuteaux et al. (2019), who estimate that up to 32% of youth (ages 0-19) firearm-related deaths by suicide and unintentional firearm injury could be prevented if adults with youth in the home engaged in safe household firearm storage practices: “…storing all firearms locked as opposed to unlocked, unloaded as opposed to loaded, and storing all ammunition locked andseparate from firearms have each been associated with a reduced risk of intentional self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries.”28 Other community partners stressed the importance of parental involvement, with one partner asking, “What is [the] general practice like for talking with students who might be experiencing suicidal ideation?” A suicide prevention specialist replied that, “When we’re talking about suicide prevention at those ages, we really have to be talking to the parents.” Suicide can be a difficult topic to approach, especially for parents who want to provide their children with age-appropriate information. While mental health disorders commonly begin in teenage years, psychiatrists have observed children as young as six years old reporting suicidal thoughts. Thus, for children who are asking questions or are known to have heard of or witnessed a tragic event, it is important for parents to discuss suicide to dispel misinformation and provide early intervention. Resources such as the University of Utah’s age-by-age guide are available for those unsure of how to broach the subject of suicide with children. 29

The overall qualitative data suggests that safe storage, education, and limiting access to firearms could be effective suicide prevention strategies, as they seek to remove a highly lethal means during critical moments when an individual might act on suicidal impulses.

Domestic violence (DV) emerged as a critical third topic for the focus group discussion (rankedhighly by 53% of participants). The gravity of the situation was marked by a recent tragedy as mentioned by a community partner: “I know of a young woman in Spokane who was recently shot and killed in a domestic violence case.” The incident served as a reminder of the lethal potential of domestic abuse, particularly when firearms are involved: “Firearms are a huge component of DV threats,” one community partner noted, explaining thatwith “firearms presentduring DV, lethality increases by five-fold.” ResearchconductedbytheEducationalFundto Stop Gun Violence (EFSGV) supports this claim: “Over half of all intimate partner homicides are committed with guns… a woman is five times more likely to be murdered when her abuser has access to a gun.”30 There is a need to reliably identify perpetrators of domestic violence and remove firearms from the household to prevent fatalities.

28 Monuteaux, M. C., Azrael, D., & Miller, M. (2019). Association of Increased Safe Household Firearm Storage with Firearm Suicide and Unintentional Death Among US Youths. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(7), 657.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078

29 University of Utah Health. (2022). How to Talk to Your Child About Suicide: An Age-By-Age Guide. University of Utah Health | University of Utah Health. https://healthcare.utah.edu/healthfeed/2022/09/how-talk-your-child-about-suicide-age-age-guide

30 Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. (2020). Domestic Violence and Firearms. Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. Domestic Violence and Firearms - The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence (efsgv.org)

One community partner who operates a free legal clinic noted, “I see a lot of domestic violence issues come in, and I see a lot of intimidation by firearms come up.” Another community partner mentioned that “Little data is collected on the non-lethal effects of gun violence, but particularly in cases of domestic violence, intimidation is a major factor. Many youths are unaware of what domestic violence and intimate partner violence looks like and have trouble identifying various forms of abuse.” Research corroborates these claims, as “Around 4.5 million women in the United States have been threatened with a gun, and nearly 1 million women have been shot or shot at by an intimate partner.” 31 Furthermore, “…because guns can be lethal quickly and with relatively little effort, displaying or threatening with a gun can create a context known as coercive control, which facilitates chronic and escalating abuse.”32 This indicates the need for further data collection on the mechanisms of coercive control (such as firearm intimidation) that are frequently used in DV cases to prolong abuse.

Community partners mentioned the complications of identifying and intervening in DV situations, as “DV and child abuse symptoms aren’t always visible.” One community partner pointed to signs in children, such as unexplained stomachaches, inappropriate age tantrums, and declining school performance as covert markers of trouble at home. This invisibility often leads to a “lack of resources provided through CPS,” with community partners agreeing on the “need [for] someone to intervene at the gray area stage, identify problems, and refer to services that exist.”

One community partner who is a Domestic Violence Prevention Executive shared insights on their evolving approach, including “Law Enforcement Officers (LEOs) doing a lethality assessment protocol (LAP) with victim survivors to get a better DV picture and connect them with an advocate over the phone.” This initiative, part of a study with Washington State University (WSU), aims to enhance victim safety and support. The group also discussed the implementation of Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPOs) and the challenges of firearms relinquishment, noting that, “in WA state it has to be relinquished to specific locations, not just another family member.” In addition to relinquishment challenges, there is a need to study the effectiveness of DVPOs in Spokane County.

31 Sorenson, S. B., & Schut, R. A. (2018). Nonfatal Gun Use in Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 19(4), 431–442 https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016668589

32 Ibid

Prevention emergedas a key focus, with community partners emphasizing the need to “create an intentional message when spreading awareness.” This included maintaining “regular dialogue about the issue and spread[ing] messages that counter violent behavior and make it clear that it isn’t right or acceptable.” The group recognized that “not discussing the issue hides its prevalence.” In addition to spreading messages through awareness campaigns, conducting an open dialogue with someone experiencing active DV may serve as the most effective intervention for concerned friends and loved ones. It is important to note that providing support for victims of DV does not always require expertise. The Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence (WSCADV) states that three strategies anyone can employ to help a victim of DV are asking questions, actively listening, and staying connected. 33

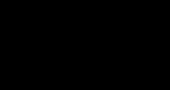

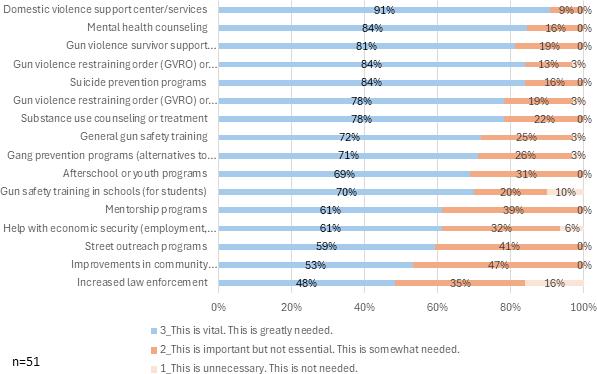

Asthe meeting concluded, community partnersagreedon the criticalneedto “bring all the coalitions together a couple times a year to share how they’re all working on prevention efforts.” This collaborative approach is essential to addressing the various challenges of domestic violence and creating safer, more resilient communities.