For details of which spaces will be open on the date of your visit, please see: http://collections.etoncollege.com/whats-on/weekend-openings

Eton College, Windsor, SL4 6DW

Telephone: 01753 370590

Website: https://collections.etoncollege.com

Blog: https://collections.etoncollege.com/blog

Twitter: @EtonCollections

Registered charity number 1139086

2023

EXPLORE

OF ANTIQUITIES

HISTORY MUSEUM MUSEUM OF ETON LIFE SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS

Museums and Galleries of Eton College OPEN WEEKENDS, 2:30-5PM, FREE ADMISSION

MUSEUM

NATURAL

The

18

04

Eton’s First Folio

From the Provost

tradition sadly ended, all illustrated by the lucky survival of a ‘black jack’ beer jug which probably once graced the table in College Hall.

08

Pouring Through History

14

The Captain,

This Journal starts with a magisterial article by Michael Meredith discussing Eton’s First Folio of Shakespeare, part of the astonishing legacy by Anthony Storer, whom his fellow Old Etonian Horace Walpole claimed to have converted from being a ‘Macaroni’ – a fashionable young man interested only in dancing – into a fellow antiquarian. If he did, he did his old school an enormous service: the Storer bequest of his magnificent collection of books and prints transformed the College’s library. The First Folio of Shakespeare must rank in any list of the top ten most important books ever published in the west – perhaps in the world. No one is better fitted to describe our copy, with its intriguing double frontispiece and extraillustration at the end than the greatest of modern Eton’s bookmen.

Do note the advertisements for the Verey Gallery exhibitions – present and forthcoming. Until April, you can see the fascinating exhibition of Japanese Imperial Waka Poetry centred around Eton’s own collection, given us by Crown Prince Hirohito when he visited. Next up in May will be a celebration of a great, lost Eton tradition – the procession Ad Montem which will include unique, conserved examples of the costumes the boys used to wear.

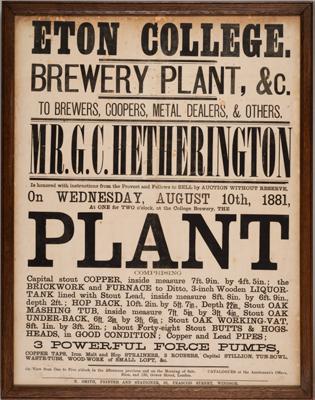

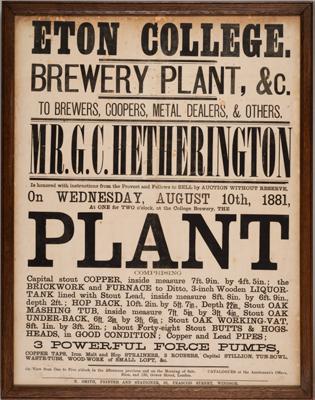

Rebecca Tessier gives an interesting brief history of brewing at Eton, from its origin at the foundation to 1881 when the

Familiarity with it can often make us forget that Eton has one of the most spectacular collections of modern glass anywhere in England in the Hone and Piper windows in College Chapel. Lynn Sanders reminds us that we might have had two more Evie Hone widows, had her health allowed it. The sketches Lynn presents here show that they would have been magnificent. But we got Piper instead – as the result of brave and not-uncontroversial decisions taken by the Provost and Fellows of the day – so we did well in the end.

Cosmo Le Breton, who left last year, will surely become a force to reckon with in the environmental world. George Fussey and he show in a powerful essay how loss of biodiversity is going hand in hand with the loss of indigenous cultures. They illustrate this with examples partly from the splendid gift to Eton by Robin Hanbury-Tenison OE, the co-founder of Survival International, of so much of his collection. They show how intrinsic to the local cultures are the beautiful headdresses which they have researched from Amazonia among the artefacts Robin so generously gave us, together with one from Papua New Guinea equally generously donated by Sarah-Jane Bentley (who teaches English at Eton) and her husband Tobias.

Abigail Allan from Oxford University has, am delighted to say, shepherded Eton’s fine collection of Greek vases into the international Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, which is attempting to catalogue in one database all Greek vases. She recounts the debt we owe to Captain Copeland, the 7th Duke of Newcastle, and Sir Leonard Wooley.

We are very grateful to Abigail for shedding such a vivid light on the origins of Eton’s important collection of Greek vases. A later sale of one of our finest vases causes me pain whenever I think of it, as does our sale (for £1000!) of the two magnificent Assyrian reliefs now in the Fitzwilliam. No proper deaccessioning policies had been written in those days!

Charlie Barranu’s article introduces us to the enormous power of modern scientific techniques in rescuing obliterated writing in mediaeval manuscripts, illustrating it with ultraviolet analysis undertaken at the British Library on a 12th century manuscript of great importance in our Library.

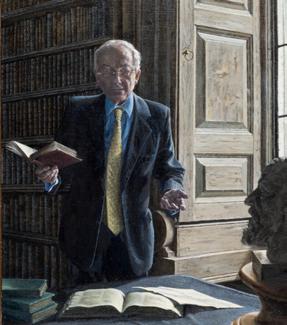

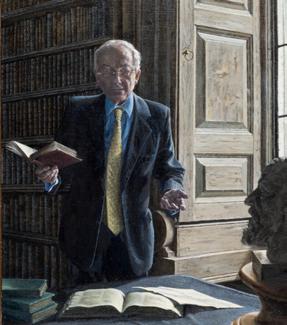

Then comes the winning essay in our new Collections Prize, by Alfred Russell (IRS). Writing with great maturity he celebrates, and rightly so, Henry Hine’s watercolour of Cissbury in Sussex from 1865. Hine was a new name to me and Alfred’s championing of his work seems to me entirely just. There is much more which it would be redundant of me to describe, but it is with great satisfaction that we can thank generous donors for some excellent new acquisitions. Among these, it gives me particular pleasure that Eton is adding to its holding of Roger Wagner OE’s painting, a portrait by him of Michael Meredith – who was Roger’s tutor – which will hang in the Library. And as so often, the Friends have come up trumps with their assistance in buying a long-lost manuscript describing the (not very satisfactory) state of education at Eton in the 1740s.

The Collections, under Rachel Bond’s leadership, and with the help of the fine team she leads, are thriving. May they continue to flourish!

Lord Waldegrave of North Hill

eton college collections Contents 02 Contents eton college collections From the Provost 03 03 From the Provost Features

Eton’s First Folio

Pouring Through History

Evie Hone’s Unrealised Designs for Windows in College Chapel

Exploring Interrelationships of Culture and Ecology in the Natural History Museum

The Captain, the Duke, and the Archaeologist: Collectors of Eton’s Ancient Greek Vases

Old Books, New Technologies

04

08

10

12

14

16

Collections Prize

Collections in Action 20 Engaging with the Collections 22 Caring for the Collections 24 What’s New Friends of the College Collections 26 Friends Review

Essay: Henry Hine’s Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset, 1865

c.470-450 BC0 (ECM.5946-2017)

Cover Image: Attic red-figure vase fragment painted by the Leningrad Painter,

the Duke, and the Archaeologist: Collectors of Eton’s Ancient Greek Vases

Eton’s First Folio

William Shakespeare’s First Folio is celebrating its quatercentenary this year. Published in 1623, only seven years after his death, it is today one of the most sought-after rare books in the world, being the first collection of all his plays, brought together by two of his actor friends. It contains 18 plays unknown elsewhere.

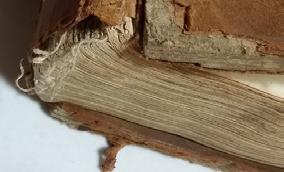

Every one of the 240 surviving copies has its own personality and unique features, whether it be the binding, ownership or annotations. Many are incomplete, some just fragments of a once-great book; others are ‘made-up’ copies with facsimile leaves or with missing pages added from elsewhere. All have been loved, treasured and sometimes altered by their owners, and each has its own story to tell.

Eton College Library’s copy is no exception. It has two unusual additions, neither of which has ever been satisfactorily explained. The first is at the beginning, where there are two title pages, one by its different paper clearly a facsimile. Bound in at the back of the book is a second enigma: 99 prints, depicting portraits and views relating to Shakespeare and his plays. No other copy has such illustrations, and one must ask why they are there and what exactly they represent.

To answer these questions, we need to know something about our Folio’s provenance. It was left to Eton in 1799 among the books of an Old Etonian bibliophile, Anthony Morris Storer, who had died that year. He bequeathed nearly 3000 books and several thousand prints to College Library, the product of a life spent collecting with discrimination. One unusual feature of his gift was that he had extra-illustrated a sizeable minority of the books.1

Extra-illustrating or ‘grangerising’2 books became fashionable among rich book-collectors towards the end of the 18th century. It meant finding appropriate prints, and even small watercolours, thematically linked to the text of a particular volume, inserting them at appropriate places and then having the ‘improved’ book beautifully rebound. Storer extra-illustrated different types of books in his library, his favourites being histories, biographies and travel books, just as his favourite prints were portraits and topographical studies.

Among other books Storer collected were Elizabethan, Jacobean and Caroline plays. He amassed 388 quartos by his death, including 20 by Shakespeare, among them the very rare first quarto of Troilus and Cressida. The late 18th century was the

time of ‘bardolatry’, when the greatness of Shakespeare was first widely recognised, and Storer was among his devotees. He also bought copies of the Second and Third Folios and modern editions of the playwright’s works, all of which are now in College Library. In 1793, towards the end of his life, Storer was given a 15-volume edition of Shakespeare’s complete works by the editor, his friend and fellow Old Etonian George Steevens. This work can be claimed to be the ne plus ultra of 18th-century Shakespearean criticism, with a commentary that incorporates the best work of previous editors. It is also well printed on high quality paper, which persuaded Storer to grangerise his gift.

Interest in extra-illustration had spread by then, and was no longer just the pastime of wealthy print collectors like Storer. It was now possible to buy sets of cheaply produced prints on selected subjects as ‘kits’ to assist the less affluent bookcollector, who would have neither the money nor time to look for and buy the originals.

An enterprising book and printseller, Edward Harding, seems to have originated the idea in the early 1790s, together with his brother Silvester, who was an artist. Edward chose and researched a selected topic, and Silvester then copied portraits or scenes from original works of art. These were then engraved and printed by a small family team working from Harding’s shop in Fleet Street. Storer began by purchasing two sets from Harding, one depicting the actors from Shakespeare’s company and a second showing characters and scenes from his history plays; to these he added a number from his own collection including portraits of some of the scholarly commentators mentioned by Steevens. From another printseller and publisher, Isaac Taylor, he bought scenes from many of the plays, engraved from paintings by Robert Smirke and Thomas Stothart. The result of this extra-illustration is most impressive, though the early volumes are more profusely illustrated than the later, and the final play, Othello, has only one illustration. To the modern eye Storer’s choice of print emphasises the historical over the theatrical, which gives the volumes a high seriousness, when the plays themselves require a more varied and dramatic illustration, which was then readily available. Perhaps he was deliberately following Steevens’ rigorously academic approach to Shakespeare?

It is likely that Storer bought his First Folio about this time. It was in poor condition, battered and bruised, but contained the text of all the plays. It had lost its front cover and most of its preliminary pages were marred or missing. The pages on which the first four plays and the final play were printed had serious damage to their margins, either through rodents or mould. Nevertheless, it was an almost complete First Folio, just needing the attention of a good paper restorer and binder. Storer found both, probably at the London firm of Staggemeier and Welcher. The tattered leaves were repaired and the whole book washed. Several preliminary pages were laid on fresh paper, and a missing leaf was replaced by one from a copy of the Second Folio (1632). To complete the work the first two leaves were recreated in facsimile. One of these was the title page with Shakespeare’s portrait, beautifully worked afresh by a contemporary artist and engraver with the initials ‘J. A. B’t.’3

It seems that Storer already had a genuine 17th-century print of the Shakespeare portrait4 mounted on another reproduction of the title page. It is cleverly rubricated, the red line masking the joins where the portrait had been inlaid. Storer added this to his Folio, before the facsimile of the same page. His motive is likely to have been aesthetic – to enable future readers of the book to compare an original print with the facsimilist’s remarkably fine copy.5

But what are today’s readers to make of the group of miscellaneous prints bound in after the Folio’s text? The choice and ordering suggest that Storer may have had the idea of extra-illustrating his First Folio. The largest proportion of these prints comes from Edward Harding’s shop and these are identical to the two sets Storer used in the Steevens edition. Placed among these utilitarian prints are 15 of superior quality by engraver-artists like Wenceslaus Hollar and George Vertue. Harding was working for a mass market, but his best work, like the view of the ruins of Flint Castle for Richard II, can be atmospheric and completely acceptable.

Together, the 99 prints illustrate the Folio’s preliminary pages and the history plays, in chronological order as printed, from King John to Henry VIII. There are indications that this was merely work in progress. There is a print of Dunsinane, presumably intended for use illustrating Macbeth, and an impressive four-view portrayal

04 05

eton college collections

Features

eton college collections

Features

The ‘doctored’ title page of Eton’s First Folio (ECL-Sa2.3.1)

George Vertue, an engraving of John, Duke of Bedford, to illustrate Henry VI, Part I

of Dover by Hollar, likely to have been selected to illustrate King Lear. From Harding come some portraits based on coins, illustrating Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra, classified by the Folio editors as tragedies, as well as a picture of Herne’s Oak for use with the comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor. It seems, therefore, that the extra-illustrating venture was broken off, or simply abandoned. Possibly Storer realised that the task was so big that many hundred prints would be needed if he were to illustrate all the plays. This would mean splitting the book into three volumes, which would defeat his purpose in purchasing the iconic Folio. More likely, his health was the real reason. As early as 1786, Storer was described as an invalid and he suffered from increasingly poor health until his death 13 years later. He had faltered in completing the later volumes of his Steevens edition, so it is possible that the magnitude of the Folio task was beyond his strength. We can never be sure of the real reason, nor why he instructed the binder to place the incomplete selection of prints at the back of this Folio.

It is even possible, though unlikely, that the Folio in its late-18thcentury binding was completed posthumously, and that Storer never saw it as it is today. If he did, it was in the final years, or months, of his life, and he would have had little time to show it to his bibliophile friends with its twin title pages and its bound-in

prints. So it has been left to the Folio’s afterlife – so far 223 years in Eton College Library – to entertain, challenge and even mystify thousands of readers.

Michael Meredith Librarian Emeritus

1. An article by Laura Carnelos on another of these books, a 1502 edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, appeared in the Collections Journal Summer 2022 issue

2. A term derived from James Granger, English clergyman and print collector, who published A Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution in 1769. This consisted of lists of portraits of men and women from British history in chronological order. It became a major reference work for print-collectors and extra-illustrators

3. As yet unidentified. It was a practice for 18th and 19th century facsimilists to indicate the nature of their work by initialing or printing their name in very small type

4. It is the third state of the Martin Droeshout engraving, with additional shading added to Shakespeare’s collar and lights in his eyes

5. An alternative explanation might be a misunderstanding between owner and binder, Storer intending the page with the original portrait to replace the facsimile

Verey Gallery, Eton College

24th November 2022 - 16th April 2023

The Nijūichidaishū

Japan’s Imperial Waka Poetry Anthology

This exhibition centres around a Japanese object in the Eton College Collections: a lacquer box containing a copy of The Nijūichidaishū (‘Collections of Twenty-one Reigns or Eras’). It is an anthology of poetry, called waka, compiled by imperial command between the 10th and 15th centuries. The collection was given to Eton by the Japanese Crown Prince Hirohito (later Emperor Shōwa) after his visit to Eton in 1921.

The exhibition focuses on the Crown Prince’s visit to Eton College, Japanese courtly culture and waka poetry through objects from the Eton College Collections, and loans from the Ashmolean Museum, the British Museum and the Ezen Foundation.

Explore the Museums and Galleries of Eton College, open weekends, 2:30pm-5pm, free admission

For more information scan QR code or visit collections.etoncollege.com

eton college collections Features 06

A print of the ruins of Flint Castle, published by Edward Harding to illustrate Richard II

Pouring Through History

This leather jug painted with the Eton shield is one of the more unusual objects in the Museum of Eton Life, yet one of the most intimately connected with the space in which it is displayed. The museum, established in 1985, is housed in the undercroft below College Hall that formerly served as the cellar for wine and the beer brewed in the adjacent brewhouse. Large pitchers such as these were used to serve beer to boys dining in the hall above in times when private brewing as a source of sterilised beverages was common. Leather drinking vessels were gradually replaced with other materials over the centuries, and being of everyday materials, not many were preserved. The survivor in the museum probably dates from the late 17th century.

Leather vessels have been used in many cultures, and in England since Neolithic times. There was a resurgence of their production in the Middle Ages, and their use continued through to the Tudor period, as leather was cheaper and more plentiful than pottery or glass, and could be easily shaped and waterproofed. While their popularity diminished over the years, leather tankards and jugs were still in use up to the mid-19th century.

Tankards like this one were known as black jacks. There is a theory that the term comes from the tankard’s distinctive shape, a silhouette similar to a defensive jacket known as a jack in the Middle Ages. However, the generally accepted origin of the term comes from the way the jug is formed: when wet leather air dries, it is known as ‘jack leather’, and to waterproof the vessel black pitch (such as tar or bitumen) or pine tar resin was often used, hence ‘black jack’.

The black jack was created by the stitching of two pieces of thick leather together forming the body including handle and base, then hardening the leather using an early technique called ‘cuir bouilli’, which translates as ‘boiled leather’. The leather was immersed in hot water then moulded and set with hot stones, resulting in the leather firming akin to wood. Finally, it was waterproofed as described above.

Depending on their size, these tankards could also be known as bombards. A black jack tended to be used for individual drinking and was a smaller vessel; larger jugs that were used to pour beer out into cups were known as bombards. This example would be at the upper end of the size scale for a black jack, and depictions of the vessels lining the long tables in College Hall imply that they were, at times, used communally.

It seems that the survival of this black jack, although not unique, is fairly rare, and likely accidental. Archival records in a number of historic colleges and schools, Eton included, confirm the purchase of leather vessels, though not many of them remain within those institutions. A number of the jacks in private collections can be traced to their original sites by coats of arms sometimes added to them as decoration. Eton’s example shows such decoration painted onto the leather on the body of the jug. Whether this one survives by virtue of being kept intentionally as an example or by being hidden at the back of a cupboard is impossible to know. The question remains as to when, and why, did the black jack fall out of use at Eton College? The answer may lie in Eton’s brewing

history. The original statutes of the College called for a brewer and Henry VI’s will indicated that a brewhouse was to stand on the north side of the outer court; the Brewhouse is recorded in the audit books from 1445. Eton College had access to water from the Thames, its own hop yard, and malt received in the form of tithes: all the ingredients for brewing quality beer and ale. To students, the black jack served a weak ‘half ale’, also known as ‘small beer’. This was a sweet beer, weakened by successively brewing the mash. The first brewing produced strong beer, the second ordinary beer, which was served to adult staff and visitors. The College Archives record sales of Eton’s beer to a number of places, including Windsor Castle. The archives even record four hogsheads of beer sent in 1646 to Charles while he was confined at the castle by Oliver Cromwell. During the 17th century brewing was one of the main industries in Windsor, where there were several established breweries, some of which served the castle. For Eton to also be providing beer for the court suggests there was a high opinion of Eton’s beer. This reputation, however, had waned by the end of the 18th century and Eton was not alone; in the late 19th and 20th centuries many of Windsor’s breweries were bought out, usually by larger, London breweries, or closed down.

The falling quality of beer was compounded by a fire that devastated the Brewhouse in 1874. Following a decision to discontinue producing beer on site, Eton’s brewing equipment was auctioned off. It is highly likely that in subsequent years, as water quality improved, that the black jack fell out of use. No longer were the tables in College Hall lined with jugs of beer for King’s Scholars’ meals – the black jack was not needed. The fact that this jug has remained at Eton at all is testament to Eton’s centuries-long

tradition of dining in College Hall; that the jug resides in the very place it was originally used is a fitting turn of fate.

Rebecca Tessier Museum Officer

08 eton college collections Features

Black jack (MEL.690-2014)

Charles Walter Radcliffe (1817-1903), The Hall, 1844 (FDA-E.517-2013)

eton college collections Features 09

Auction poster recording the sale of brewing equipment, 1881 (MEL.798-2022)

Evie Hone’s Unrealised Designs for Windows in College Chapel

The stained-glass East Window of Eton College Chapel: The Last Supper and the Crucifixion, designed and made by Irish artist Evie Hone (1894-1955) and completed in 1952, is often considered amongst the greatest examples of the artist’s work. However, the commission to replace the old east window, damaged by a bomb in 1940, was not the only stained glass that Hone had been asked to design for Eton in the early 1950s. The College Archives contain rarely seen preliminary pencil and gouache studies for two more windows; one either side of the East Window itself.1

Evie Hone was born in 1894 in County Dublin. Her childhood was thrown into turmoil when she became ill with infantile paralysis aged 11, and poor health was to challenge her throughout her life. Confined to her bed for much of her childhood, she turned to drawing and thus began her great love affair with art. She studied, first in London, and then from 1920 in Paris under the tutelage of

André Lhote (1885-1962) and later, with a leading exponent of cubism, Albert Gleizes (1881-1953). During the 1920s Evie Hone was amongst the leading proponents of the modern abstract movement, and exhibited her paintings in Paris, London and Dublin.

In 1933 Hone turned her attention to the making of stained glass, a medium that put her painterly skills to good use, while also allowing her to express her deeply held Christian beliefs. Always intensely religious, Hone converted to Catholicism in 1937. She was inspired by the expressionism of George Rouault (1871-1958), early Irish sculpture and the great medieval windows of Chartres and Le Mans Cathedrals. Her early successes in stained glass included windows for the Jesuit College in Tullabeg, Co. Offaly and the parish church at Kingscourt, Co. Cavan, which were to prove instrumental in persuading the authorities at Eton that she was the artist they were looking for to design a new east window for College Chapel. The decision to commission her was not without controversy, but in October 1949 Provost Claude Elliott (18881973) and the Fellows confirmed her appointment and it was agreed that the 18-light window would consist of the two scenes we see today, the Last Supper in the lower half of the window and the Crucifixion in the upper half, with a wealth of symbolic imagery in the traceries.

As soon as the East Window was complete in the spring of 1952 it was proposed that Evie Hone be asked to also create the two flanking windows. Hone suggested that ‘what is needed in these two windows is good colour and not much distraction’2 and, at the College’s request, she produced the studies reproduced here, as two possible alternatives; one with a variety of symbols in the main part of the window and the other, a more abstract design with some symbolic or figurative elements in the tracery. The glass was to be in rich, deep colours to harmonise with the East Window itself. In November, it was confirmed that design 2 had been approved, although it was agreed that the top lights would be darker than shown in the original sketch. It was then assumed that Hone would further develop the accepted study and begin making cartoons.3

How much further Evie Hone progressed with the work in her studio is uncertain, however, no further sketches or cartoons were presented to the authorities at Eton and by January of 1954, concern was being expressed at the lack of progress. There was some anxiety that a disagreement over the final sum paid for the East Window may have upset Hone, with the Provost suggesting

that ‘she appears very much aggrieved with us’4; and an additional payment was made to the artist to try and settle the matter

fairly. However, what seems likely is that, following the success of her work at Eton, new commissions including stained glass

for All Hallows Church in Wellingborough and a window for Washington Cathedral in the US had been taking up her time. More significantly, Evie Hone’s health was now failing. The Provost wrote on 23 November 1954:

“I have been wondering whether I was too diffident about pressing her to let us have at least some detailed designs at an early date, but she looked so frail and tired, and was so definite about her promise to Wellingborough, that I felt it would have been brutal to have argued with her.”5

On 13 March 1955, Evie Hone died while attending mass at her parish church. Her loss was keenly felt by her many friends and also by those at Eton who had championed her work. It was left to artist John Piper, himself a great admirer of Hone, to design a magnificent new scheme for the side windows in College Chapel, four either side of the East Window Hone’s studies for the flanking windows were bequeathed to the College in 1958 by her sister Nancy Connell who had expressed the wish that they be included in an exhibition of her sister’s work in Dublin later that year - a wish the Provost and Fellows were happy to grant. Preliminary as they are, the sketches are a fascinating clue to Evie Hone’s unrealised vision for the east end of College Chapel.

Lynn Sanders

Assistant Keeper Fine & Decorative Art

1. Eton College Archives (ECR 65 0940A & ECR 65 0940B)

2 Meeting of the Standing General Purposes Committee, Saturday 17 May 1952, Agenda Item No. 5 (ECA COLL B SF 14 6 B)

3. With thanks to Dr Joseph McBrinn, Ulster University, for his advice on material in the Evie S. Hone Archive, private collection

4. Meeting of the Provost and Fellows, Saturday 27 March 1954, Agenda Item No. 8, (ECA COLL B SF 14 6 B)

5. Letter from Provost Elliott to Sir William Holford, 23 November 1954 (ECA COLL B SF 14 5)

eton college collections Features 10 eton college collections Features 11

Evie Hone (1894–1955), Studies for a Window of Eton College Chapel: Design 1 & Design 2 1952, pencil and gouache (ECR 65 0940A; ECR 65 0940B) © DACS 2023

Evie Hone in her studio at Rathfarnham, near Dublin c.1952 Fáilte Ireland. “Evie Hone- Stained Glass.” Digital Repository of Ireland. Dublin City Library and Archive, December 9, 2020. https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.qr474g626.

Evie Hone (1894–1955), East Window of Eton College Chapel: The Last Supper and the Crucifixion 1952, stained glass (FDA-A.398:1-2017) © DACS 2023

Exploring Interrelationships of Culture and Ecology in the Natural History Museum

Hanging on the wall on the first floor of the Eton Natural History Museum, six headdresses overlook an ethnographic collection including spears, daggers and exquisitely carved hornbill casques. Birds are captured and kept semidomestically by indigenous cultures worldwide. Birds also contribute nutritionally to community diets and they are used in tribal medicine. The feathers may be used to make stunning headdresses, such as those on display, worn to denote status and enhance personal identity. They can function to mark rites of passage as well as representing hunting prowess and qualities of leadership. This article explores the cultural and ecological relationships intertwined in each headdress.

Global biodiversity decline has resulted from a number of anthropogenic causes including the climate crisis1. In some of the most remote regions on the planet, loss of biodiversity has gone hand in hand with loss of indigenous cultures – in terms of land, territories and natural resources. The headdresses from indigenous cultures in our museum represent this clearly. Understanding ways in which indigenous peoples interact sustainably with their local environments is something that the museum has sought to explore in the last decade. When the Robin Hanbury-Tenison (RHT) collection was given to the museum in 2013 it presented a golden opportunity to highlight some of the challenges faced by indigenous communities, and in particular the extreme pressure that the natural environment was under in places such as Amazonia and Papua New Guinea. Robin Hanbury-Tenison OE (AKW, RDFW ’54) had led the way as a co-founder, Chairman and President of

the charity Survival International. In 2018, the five Amazonian headdresses in the RHT collection were beautifully complemented by the donation of a headdress from Papua New Guinea by Tobias and Sarah-Jane Bentley. We have recently been able to analyse the headdresses in the museum collection to learn more from these objects. For accurate species-level identification, the headdresses were taken in May 2022 to the Natural History Museum at Tring where they were examined by two senior curators of the Bird Group in the Department of Life Sciences. The bird skin collection in Tring is the national collection, with 750,000 bird skins and the largest bird egg collection in the world; it was an incredible experience to look behind the scenes.

The headdress from Papua New Guinea (NHM.832:1-2018) was given to Tobias Bentley by the South Fore Tribe in the Eastern Highlands whilst he was working for the Medical Research Council’s Prion Unit2. Headdresses were worn by the South Fore people until the 1950s, when Australian colonial forces established control of the Fore region, but were retained for special occasions. With feathers that look like pastel blue enamel and brittle to touch, birds of paradise are clearly represented in this example, along with the lorikeet diversity for which New Guinea is famed.

At Tring we established that the blue feathers belong to a male King of Saxony Bird of Paradise (Pteridophora alberti), with the fused feather barbs creating an ‘enamelled’ or ‘plastic’ effect. Used for courtship displays, these feathers are very unusual in that they are actually occipital feathers emerging from the crown of the bird, twice as long as the body. They function as ‘head-wires’ and are waved around as part of the display. Feathers from Lawes’s Parotia (Parotia lawesii) are also included in the headdress. A bird with irises that change from blue to yellow depending on its mood, it also has delicate occipital feathers in the form of black wires with barbs at the tip. Lorikeets – distinguished by their brush-tipped tongues which are used for collecting pollen and nectar from numerous species of flowers, are represented in the headdress by the Fairy Lorikeet (Charmosyna pulchella). Given that these three species are all found in mountainous forests, this

riverbanks, and water spirits form a centre point of mythology. Indeed, Hanbury-Tenison described visiting a Kamayura village which was located besides a lagoon full of fish where he was presented with a headdress (NHM-HT.95-2014) after the local tribespeople danced the ‘fish dance’.3

Another headdress (NHM-HT.134-2014) is dominated by the large blue feathers of the blue-and-yellow macaw (Ara ararauna) as well as brown and white barred feathers. The latter feathers are from the curious and highly sexually dimorphic bare-faced curassow (Crax fasciolata). Living in gallery forests and in the flooded Pantanal and Cerrado regions of Central Brazil, they are one of the most eccentric and niche-specific birds of South America, consisting of a number of species that have non-overlapping distributions. The other headdresses also highlight trade patterns, with feathers of the green billed toucan (Ramphastos discolorus) as well as the Amazonian oropendula (Psaracolius yuracares). Both species have ranges that do not overlap with the Upper Xingu region where the headdresses were made, suggesting the importance of trade across the Amazon region. Many of these tribes were displaced from the Lower Xingu by Portuguese colonists from the 18th century onwards, and fled upstream into what is now the Xingu Indigenous Park, so species assemblages in tribal headdresses will have changed over time.

headdress clearly highlights the isolation of the highland South Fore communities, which have access to some of the rarest and most unique feathers in the animal kingdom.

The headdresses from the RHT Collection were presented to him on his expeditions to Brazil in the 1960s. The species assemblages in these examples reveal a wealth of information about tribal culture and trade patterns in a region that remains poorly known by outsiders. Using skins from the research collection, many of the feathers in the Brazilian headdresses were identified to species level. This allowed an analysis comparison of their distributions, which enabled trading links between regions to be determined. Given by the Yawalapiti, Waura and Juruna tribes, all five of the headdresses were made in the Upper Xingu region, an area defined by a major southern tributary of the Amazon. Clear to see were the black and white feathers of the Orinoco Goose (Neochen jubata), a species limited to wet savannah and riverine ecosystems which surround the Yawalapiti who live beside Lake Ipavu. Hunted across the Amazon basin, the Orinoco Goose overlaps with the distributions of the other species represented in these headdresses. Water plays an intrinsic role in these communities – men paint their bodies before ceremonies on

The six headdresses in our collections all feature vibrant feathers from some of the world’s most iconic and behaviourally complex birds. With habitat destruction devastating these species worldwide, it is no wonder that cultural traditions that have evolved alongside them are likewise being threatened with extinction. In many cases these headdresses represent a fading chapter of indigenous history and we are eager to share their story.

Cosmo Le Breton (PAH ‘22) and George Fussey, Curator, Natural History Museum

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the professional advice of Mark Adams and Hein van Grouw, Senior Curators of the Bird Group in the Department of Life Sciences at the Natural History Museum, Tring.

1. Almond, R.E., Grooten, M. and Peterson, T., 2020. Living Planet Report 2020-Bending the curve of biodiversity loss. World Wildlife Fund

2. Alpers, M.P., 2008. The epidemiology of kuru: monitoring the epidemic from its peak to its end. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363 (1510), pp.3707-13

3. Hanbury-Tenison, R., 2012. Beauty Freely Given: A Universal Truth Artefacts from the Collection of Robin Hanbury-Tenison. Garage Press

12 13 eton college collections Features eton college collections Features

Xingu headdress containing Orinoco Goose and Scarlet Macaw feathers (NHM-HT.133-2014)

Kamayura headdress containing Scarlet Macaw, Green Billed Toucan, Amazona sp., and Amazonian Oropendula (NHM-HT.95-2014)

The Captain, the Duke, and the Archaeologist: Collectors of Eton’s Ancient Greek Vases

In March 2022, researchers from the University of Oxford visited Eton on behalf of the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum (CVA). The CVA is an international research project cataloguing ancient Greek painted vases, overseen by the Union Académique Internationale and, in Britain, the British Academy. By cataloguing and photographing these vases, they are made available to researchers all over the world.

These vases were made throughout the Mediterranean from the tenth to second centuries BC by culturally and linguistically similar peoples who recognised themselves as Greek. They were typically made in the black-figure technique (black silhouettes painted onto the vase surface with incised details and slip added) and red-figure technique (figures reversed with the background and details painted). Eton’s vases will form two CVA fascicules, one cataloguing its whole vases – over 50 of them – and the other its 452 fragments, variously made in Athens, South Italy, Corinth, and Etruria. Eton will join Winchester and Harrow as the only British schools represented in CVA publications. Although Eton’s Greek vase collection is relatively extensive, it is outnumbered and somewhat overshadowed by the school’s collection of around 2,600 Egyptological items, which this CVA will amend, bringing Eton’s vases international recognition.

This article concerns the vases’ journeys to Eton. It is an abridged version of the forthcoming CVAs’ Collections and Display History, which will be published with full references and bibliography. Eton’s Greek vases are part of the School’s broader antiquities collection, housed in the Museum of Antiquities, which incorporates the Myers Collection, named after its donor, Major William Myers (1858-99), an Old Etonian (1871-75) and Adjutant to the rifle volunteers (now the Eton Combined Cadet Force) who bequeathed his collection of Egyptological items in 1899 as a teaching aid. Eton’s Greek vases, however, do not relate to Myers. They come from three other sources: Captain Copeland; the 7th Duke of Newcastle; and Sir Leonard Woolley.

Captain Copeland

The Copeland Collection, donated by Captain Richard Copeland’s widow in 1857, became Eton’s first collection of Greek vases and antiquities. It comprised 35 items, of which 20 are vases. Born in 1792, Copeland became a naval captain in 1825 and immediately commanded a survey of the Eastern Mediterranean and archipelago until his retirement in March 1836. At least some of his items were collected there, including a decorated skyphos (a two-handled deep

drinking cup) from Aegina (ECM.5380-2017) and some glass bowl fragments from Milos (ECM.3936-2017).

Copeland was not an Old Etonian but when he retired he lived in Slough and Windsor, and after his death, his widow’s pension was paid to the Windsor post office. This led a previous curator to speculate that the couple ‘had made friends with Etonians’ and so had decided to leave their antiquities to the School.1 An example of a skyphos in Eton’s collection, likely collected by Copeland, is shown here (ECM.3165-2017).

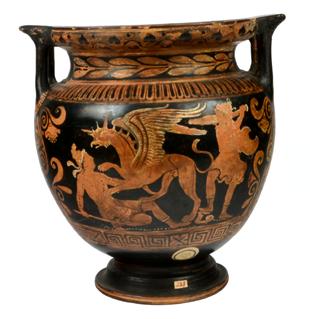

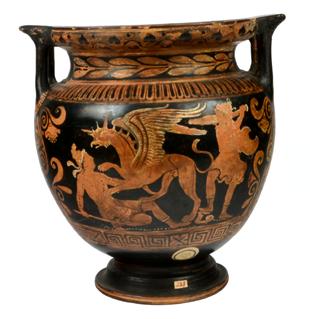

The 7th Duke of Newcastle Eton’s second group of vases was donated by the 7th Duke of Newcastle, Henry PelhamClinton (1864-1928), an Old Etonian, in 1917. He and his younger brother, Lord Francis Hope (1866-1941), were the greatgrandsons of Thomas Hope (1769-1831), an art collector and connoisseur, who in 1801 had acquired part of Sir William Hamilton’s second collection of vases. Hamilton (17301803) had been instrumental in increasing the desirability of Greek vases in Britain towards the end of the 18th century. In 1798 he had shipped his second vase collection from Naples to Britain but lost one-third when the ship wrecked off the Scilly Isles. Hope purchased the remaining two-thirds, and by 1806 owned more than 1500 vases, selling and acquiring them throughout his lifetime. As both Hamilton and Thomas Hope are key figures in the history of British Greek vase collecting, Eton’s former Hope vases are art-historically important. One of the Hope vases now at Eton is pictured; it depicts a griffin clawing an Amazon, a mythical warrior woman (ECM.6254-2017).

The vases came to Eton after being sold at Christie’s in 1917 by Lord Francis, indeed the lot number 144 is still visible today. Eton, however, did not purchase the vases – instead, Henry Pelham-Clinton purchased them from his brother’s sale and ‘put [them] aside for Eton.’2 Henry presumably wanted to give something back to his school, perhaps inspired by the presence of the Copeland and Myers collections: ‘objects attract objects’.3

Leonard Woolley

Eton’s third group of vases are 452 fragments and a selection of damaged bowls decorated with birds. These were excavated from Al Mina under Sir Leonard Woolley (1880-1960) in 1936. An Iron

Age port, Al Mina (today in Turkey) was probably the earliest of the new Greek settlements or trading posts in the Eastern Mediterranean, and is our best and earliest source of information about the Greeks overseas. Unlike Eton’s other Greek vases, these are fragmentary as they came from a settlement context rather than from a sealed tomb, where the whole vase tends to be preserved.

Part of the 1936 finds were offered to Eton that autumn via Sir Neill Malcolm (1869-1953), an Old Etonian and friend of Woolley’s. The 1936 season was funded by private subscribers through Malcolm’s initiatives, alongside a contribution from the Ashmolean and the British Museum Trustees, who had conceived the excavation; it was common for institutions and individuals to ‘subscribe’ to a dig in return for a portion of the finds. As Malcolm had contacted funders, he asked Old Etonian supporters ‘whether they would be willing

1. COLL B SF 029 05, Letter from George Tait to Dr M H

2. Ibid.

3. N. Reeves, ‘Ancient Egypt in the Myers Museum’, 2003

4. Eton College Archives, COLL P 09 060 61

to pass on their souvenirs to Eton’, a suggestion which was well received.4 Eton’s Head Master gladly accepted the finds, commenting on their utility for ‘getting boys interested in such things and as a help to their teaching’. The British Museum and Ashmolean had been given first choice as institutional supporters but nonetheless there were ‘plenty left to make a most interesting and important contribution’ to Eton’s collections. Eton’s Al Mina fragments can therefore be considered, in terms of quality, on par with those of these institutions, and are of extreme interest archaeologically. Some of Eton’s fragments are even by named painters, meaning scholars recognise the painter’s hand across multiple vases. Possibly the College’s finest example of red-figure is a fragment by the ‘Leningrad Painter’, dated c. 470-450 BC (ECM.5946-2017). Additionally, despite the relatively poor black-figure finds at Al Mina, there are some wonderful examples at Eton, such as a fragment of an oil-vessel or jug (an alabstron or olpe), with scale patterns, dated c. 650-640 BC and attributed to the Chigi Group (ECM.3593-2017).

Eton’s Greek vases, which came from three sources variously related to the school, are an exciting collection of importance both to the history of the College and Old Etonians, and to the history of Greek vases, with some fine examples deserving of further study.

Abigail Allan

Probationer Research Student in Classical Archaeology, University of Oxford

14 eton college collections Features

Balance, September 1967

Corinthian black-figure skyphos with added purple, C6th BC, (ECM.3165-2017)

Lucano-Apulian red-figure column krater with added white, late C4th BC, (ECM.6254-2017)

Attic red-figure vase fragment painted by the Leningrad Painter, c.470-450 BC, (ECM.5946-2017)

eton college collections Features 15

Corinthian black-figure vase fragment with scale patterns, c.650-640 BC, (ECM.3593-2017)

Old Books, New Technologies:

multispectral imaging and the provenance of a 13th century manuscript in College Library

When Henry VIII decided to appropriate all possessions of English monasteries as the new Head of the Church of England, many books were relocated to new homes and owners. Some volumes were conserved and others recycled; many were destroyed or lost to time. As the king fashioned himself as the leader of a new religious institution during the 1530s and ‘40s, medieval books sometimes show traces of this transition. Usually, these appear in the form of erasures of any remnants of the Church of Rome: the word ‘saint’ next to the names of particular individuals like Thomas Becket, or the mitre in illuminations portraying the pope. In practice, the dissolution of the monasteries also marked a shift in ownership, meaning that volumes that bore inscriptions of monastic or similarly institutional affiliations were scraped off and forgotten. That is, until new technology can bring them back to light.

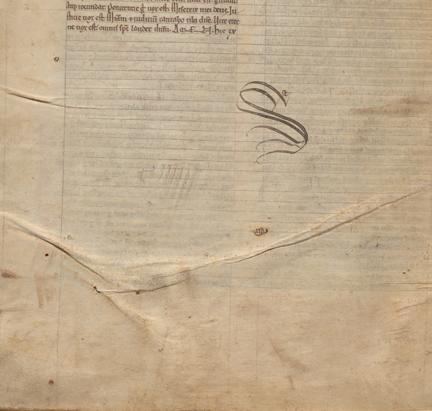

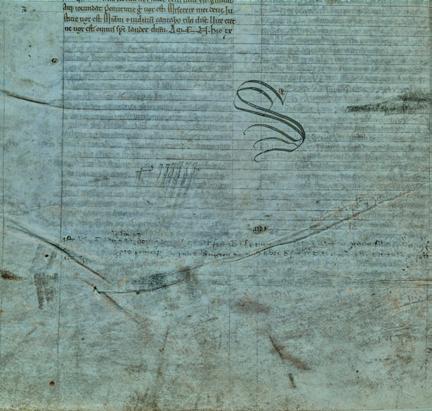

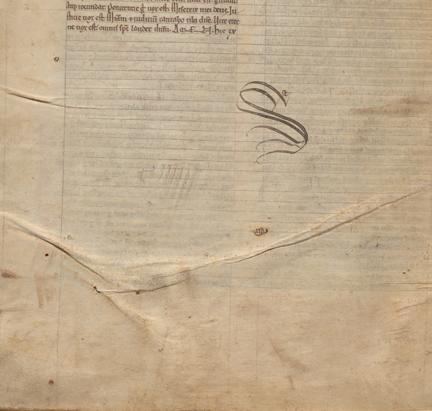

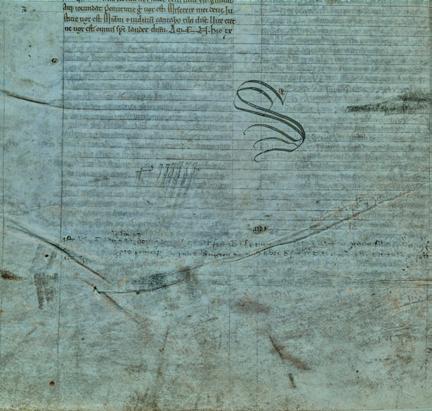

Eton College Library has a rich collection of medieval manuscripts from the 10th to 15th centuries. One of them, MS 9, is a commentary on the Psalms by Peter Lombard, a famous 12th-century scholar who became Bishop of Paris. His writings encapsulate medieval theological thought and were found in many monastic libraries. Eton’s volume dates from the first half of the 13th century, but it is not clear how it came to the College, founded two centuries later. The manuscript presents an erasure, however, that seems to have been an old mark of ownership.

A note regarding this erasure is recorded in the most recent catalogue of College Library, written by the esteemed palaeographer Neil Ker. Palaeography is the discipline

dedicated to the classification and reading of ancient handwriting (from the Greek ‘palaios’, old, and ‘graphein’, to write), and helps us not only to understand ancient texts but also to date them. Incidentally, Ker had been to school at Eton, but he was not interested in College Library as a pupil. He became curious about medieval literature and manuscript culture when attending university, growing into a passionate antiquarian and influential scholar of the Middle Ages. When he came back to Eton to produce a catalogue of its manuscripts in the 1970s, he used a black light to attempt to read the erased inscription in MS 9, which

were found and how knowledge was transmitted across Europe and beyond. Although scholars have been studying these objects meticulously for decades, the books still surprise us by continuing to provide new information about their function, owners and the time in which they were

ultraviolet (UV), white, and near infrared (NIR) lights to investigate the erasure.

In natural light, the photographed page shows damage to the parchment where the ownership inscription used to be, likely scraped off with a knife rather than washed away. Some ink blotches are also visible.

he inferred began with ‘Iste’ (Latin for ‘this’). Upon second inspection in 2022, a new attempt at reading the same inscription showed ‘Iste liber de sa...’ (i.e. ‘this [is] the book of sa...’). It therefore seemed likely to be a volume that once belonged to a religious institution – an exciting discovery in the field of medieval studies.

While the historians and bibliographers of the last two centuries focused on extant manuscripts to identify which texts survived from pre-modern Europe, current scholarship is increasingly orientated towards recovering where these texts

used. For instance, particular photographic techniques allow us to analyse handwriting under the full spectrum of light, exposing different faded inks trapped in the parchment. It is also possible to merge images shot with different wavelengths to combine all traces of the ink that is no longer visible to the naked eye, a process called multispectral imaging.

Eton College, like most heritage institutions in the UK, does not house the specialist equipment to carry out this photographic assessment. Therefore, MS 9 was taken to the British Library, where a senior imaging technician shot the manuscript with

‘fluorescence’. By contrast, the parchment reacts (at atomic level) by emitting a bluish light, which creates a contrast with the ink that makes it easier to read.

NIR rays are much longer than UVs and penetrate much deeper into the material to highlight different layers of use. The photographs shot with NIR light did not reveal any hidden text, suggesting that Peter Lombard’s work was the only text that was ever copied on these sheets. On the other hand, exposing the page to the UV rays for two minutes showed not only the inscription beginning ‘Iste liber’ but also a few others which were revealed to be similar ownership marks. Since the inks used in medieval books are carbon- or iron-based, they do not react or ‘glow’ when they are exposed to UV rays – a phenomenon called

Parts of the inscriptions are still very difficult to read, partly due to surface damage to the parchment or excess ink covering words. The two-line inscription that first caught Ker’s attention shows a script called Anglicana, which presents features typical of the 14th century. Although the knife has completely erased some of the inscription, parts of it can still be deciphered: the word ‘le longe’ or ‘le logge’ has been added above the first line, while the word beginning ‘sa’ seems to be standing for ‘sacerdo[…]’ or ‘priest’. It could be that the volume was owned by a priest whose name was completely erased. The UV also highlighted two other inscriptions: one that is contemporary with the text, as it is written in the same 13thcentury ‘protogothic’ script, and a later signature, written in a secretary hand that suggests it was written in the 15th century. The dating of all of these notes is made possible by palaeographic analysis, as some handwriting features only appear in particular periods in England. The UV finally showed the presence of copious notes written in plummet – a material similar to graphite, giving the impression of a modern pencil. The length of these inscriptions suggests that they were not ownership marks but perhaps discursive notes on the content of the volume; alternatively they may have been prayers or proverbs, all of which are common finds in medieval manuscripts.

The use of multispectral imaging shows that, as technology evolves and improves, we can continue to discover new aspects of the history of objects that are hundreds of years old. This time, we found out that the book was used by different readers across three centuries and it continues to be studied today.

Charlie Barranu Library Curator

16 17

eton college collections Features eton college collections Features

Eton College Library MS 9, f.183v in natural light

Eton College Library MS 9, f.183v under UV light, 2-minute exposure

Collections Prize Essay: Henry Hine’s Cissbury , Sussex, at Sunset, 1865

The inaugural Collections prize competition ran in 2022. Open to boys in C Block (lower sixth), this annual prize encourages engagement with objects in the Collections. The winner was Alfred Russell (IRS) for his essay on Henry George Hine’s watercolour Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset (FDA-D.290-2010). An abridged version of that essay appears here.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the rise of watercolour painting as a serious artistic endeavour progressed hand in hand with the growing acceptance in Britain of ‘landscape’ as an appropriate subject for painting. Henry George Hine’s Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset, painted in 1865, expresses the atmospheric ambiguity that the watercolour pigment offers, and in this article, I will discuss how Hine, a coachman’s son from Brighton, was able to combine ideas from the best British landscape painters to culminate in a magnificent depiction of his home county of Sussex.

The watercolour might be considered by some to be a preliminary ‘drawing’ for artists who work in oil, acrylic or gouache, but watercolour painting is one of the hardest techniques to master. Hine chose this unforgiving and unpredictable medium to reflect the complexity of the natural world. The painting highlights the difference between watercolour used quickly to capture an

idea, and watercolour used to paint a finished work intended for sale. Hine’s watercolour contains precise detail and a harmonious use of colour, contrasting with Ruskin’s Capri, 1841, also in the College Collections (FDA-D.461-2010). The form of Capri is created with a simple blue and grey watercolour wash. The fluidity of the paint requires the steadiest of hands, and the inability to correct mistakes provides a challenge that pencil drawing or oil painting does not.

In Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset, Hine captured the breathtaking, mystical nature of the South Downs with a Turner-esque golden sunset that illuminates the quiet paths weaving through the curvilinear hills. There is a strong sense of atmospheric perspective, and Hine uses the technique first developed by Leonardo da Vinci, who observed that as a landscape recedes from the viewer, its colours and tones should become less saturated. This effect can be achieved in a painting by establishing gradual tonal changes between foreground and background, thus creating an impression of space that approximates that seen in nature. The hazy blue of the central hill in the painting is almost impressionist in style, and the blurred horizon develops a sense of ambiguity in this heavenly portrayal of Hine’s homeland.

The glorified nature of Hine’s painting suggests there is a deeper immaterial element; the heaven-like glow, the delicate stratus clouds, and the solitary man with his dog reflect the harmonious cosmos. Measuring only 20.6cm by 47cm, it is small for a landscape, yet Hine manages to recreate a level of detail comparable to Jan Van Eyck, down to every whisper of the clouds. The sliver of the moon in the golden-pink sky might represent the immortality of the natural world, which is in harmony with the sky, and the dog has connotations of loyalty, much like the allegiance Hine must have felt towards Brighton and his home. My interpretation

is that the landscape painting represents the unclear journey of life: the rugged path that leads into the misty, ambiguous horizon, and the silhouette of the dark hill represents both an obstacle and an opportunity for adventure beyond it. There is a sense of ambiguity to the identity of the silhouetted man; is it Hine himself, or is he representative of mankind and the viewer? Alternatively, Hine may have painted the scene en plein air with the simple intention of recording the beauty of the English countryside.

The influence of Copley Fielding (17871855) can be felt throughout Hine’s work,

and the painting of Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset is no exception. Fielding taught his craft to the promising young artist Henry Hine, and it was from this that Hine developed into a sophisticated artist. Fielding was a painter of much elegance, taste and accomplishment and has always been highly popular with purchasers, and it is interesting to note that Fielding painted from Hampstead, where Hine lived for most of his later years. Another painting where we can draw similarities is A Sunny Morning (FDA-D.244-2010), where Fielding uses aerial perspective and rolling hills that appear blue in the distance, just like Hine’s work. Perhaps inspired by JMW Turner’s world-renowned depictions of the sea, Fielding and Hine also produced many watercolour seascapes, epitomising the flexibility and range of their talent.

Henry Hine’s paintings go somewhat under the radar when considering 19thcentury watercolour, but his depiction of Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset reflects the artist’s understanding of light, as well as his mastery of the watercolour technique. An implicit theme in the painting is of belonging, and despite minimal recorded information surrounding his work or life, there is a mystical feeling of familiarity and connectivity in the simple, unspoilt countryside scene.

Alfred Russell (IRS)

18 eton college collections Features 19 eton college collections Features

Henry George Hine (1811–95), Cissbury, Sussex, at Sunset 1865, watercolour with scratching out (FDA-D.290-2010)

John Ruskin (1819–1900), Capri 1841, pencil and wash (FDA-D.461-2010)

Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding (1787–1855), A Sunny Morning, pencil and watercolour with scratching out (FDA-D.244-2010)

Collections in Action

Engaging with the Collections

Shelley Bicentenary

As part of a special event to mark the bicentenary of the death of the Romantic poet and Old Etonian Percy Bysshe Shelley, we welcomed members of the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association as well as students and staff from Eton and Holyport College to view a display of related materials from College Library and College Archives. Highlights included manuscripts and first editions, Shelley’s Latin thesaurus from his schooldays and a watercolour of Casa Magni at Lerici made just weeks before the poet’s death there by drowning.

In October, to coincide with our special exhibition on Joseph Banks, the Collections hosted a cross-curricular study day for upper sixth form students of biology, economics, geography and/or history. It was attended by pupils from Eton and seven state secondary schools, who heard from and asked questions of eminent speakers from the University of Cambridge, the Natural History Museum in London, Kew Gardens and the University of Sheffield. Attendees also had the opportunity to visit the Eton Natural History Museum and the Banks exhibition.

Digitisation of Illuminated Manuscript

Eton’s 14th-century copy of Dante’s Commedia has been digitised for the Illuminated Dante Project. Our beautiful MS 112 will appear on the online database of 280 illuminated manuscripts, the largest ever of its kind. It will be a valuable addition to this comprehensive research tool, created in commemoration of the 700th anniversary of the death of the poet.

Visiting Primary Schools

The 2021-22 school year saw the highest level yet of primary school engagement with the Collections. Following the end of pandemic restrictions, external schools eagerly returned to onsite teaching, with some coming for repeat visits as well as new schools visiting for the first time. In addition, we continue to deliver online teaching sessions when a school’s financial, staffing, time or other constraints make a virtual lesson preferable to one in person. In recent months we have developed a popular new creative writing lesson and also a session on climate change; these have now joined our standard menu of school sessions.

Collections on Tour

In May 2022, four items from Eton’s Natural History Museum travelled to an exhibition at the West Berkshire Museum in Newbury, where they feature in a year-long exhibition on The Age of Dinosaurs. Paintings from our Fine & Decorative Art collection by G.F. Watts and John Singer Sargent may be seen, respectively, in the current and forthcoming exhibitions The Legend of King Arthur: A Pre-Raphaelite Love Story (Falmouth Art Gallery: 17 June 2023 –30 September 2023) and Sargent and Fashion (Boston Museum of Fine Art 2 Oct 2023 – 15 January 2024; Tate Britain: 21 February 2024 – 7 July 2024).

eton college collections 20 21

Collections in Action

eton college collections

Collections in Action

Study Day

Caring for the Collections

Gallery Lighting

Special exhibitions are looking especially sharp following the installation of new lighting in the Verey Gallery. For conservation reasons, we upgraded to a system that allows us to control light levels much more precisely and accurately. The stable output of the new LED lights allows us to calculate and control light exposure to museum standards, ensuring that each object is lit appropriately and that fading and degradation are minimised. The new LED lighting does not give off heat in the way that halogen lights do, which helps to maintain a stable environment in the gallery and reduces energy consumption.

Montem Costumes

Articles of fancy dress worn in the 19th century by boys taking part in Eton’s Montem procession have been returned to their former glory through remedial treatment by specialist textile conservators. Flamboyant jackets, plumed velvet caps and slashed silk breeches have been treated to support their innately acidic and fragile fabric. Unravelled braids and strained seams of countless alterations have been supported with semitransparent overlays, while stains have been softened by spot cleaning. These costumes, conserved thanks to the Friends’ special Montem Appeal, will be on show in the forthcoming special exhibition Ad Montem

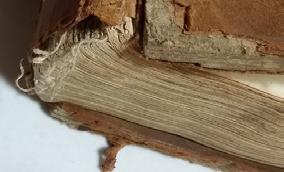

Audit Books Project

In 2019, the College Archives set out to conserve the College’s audit books dating from 1505 to 1899 (ECR 62 1-36). These books were compiled by centuries of College Bursars and record all manner of income and expenditure, from rents and tithes received to stipends paid to staff, from the purchase of food and wine to repair of buildings. Twenty-one volumes that showed signs of deterioration due to age and frequent handling were sent to an external conservator for repair. We are pleased that this project to conserve and rehouse the collection is now complete and all of the audit books are back in the Archives.

Royal Portraits

Pendant portraits of King Charles I and his Queen Consort Henrietta Maria returned from a London conservation studio following repair and cleaning. They date from the reign of Charles I and are painted after works by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), almost certainly from his own studio. Labels discovered on the reverse indicate that they were formerly in the collection of Lady Mountbatten at Broadlands, Hampshire. The results of the recent work are particularly noteworthy for the brightening of the portraits following the removal of badly yellowed varnished layers.

Deep Clean of College Hall

At the end of August, College Hall was deep-cleaned, ceiling to floor, removing layers of dust (and balloons!) from out-of-reach areas. It took a week to complete, with help from the Buildings Department, who kindly detached and moved the fixed tables and benches to enable access via scaffolding. The cleaning of the canopy within the hall was a particular highlight: its assortment of Provosts’ coats of arms is looking particularly impressive.

22 23 eton college collections Collections in Action eton college collections Collections in Action

Collections in

Action

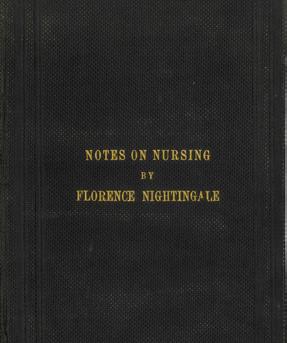

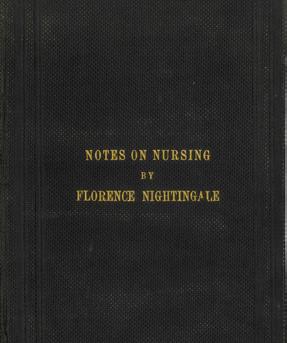

Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing

College Library has acquired a scarce first edition of Florence Nightingale’s landmark work Notes on Nursing (1860). Addressed primarily to caregivers, with the broader aim of effecting social and institutional change, the book sets out Nightingale’s famous instructions for ‘fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet’. This appeal proved highly popular, selling 15,000 copies within two months of its publication.

Joseph Banks in Print

Despite writing tens of thousands of letters to scientists around the world, the naturalist Joseph Banks published remarkably little. The Natural History Museum recently acquired a copy of the third edition of William Curtis’s book Practical Observations on the British Grasses (1805), which contains an appendix written by Banks about blight, a fungal disease of wheat and corn that had a devastating effect on the harvest in 1804.

‘Lost’ Manuscript on Teaching at Eton

Thanks to the generous support of an Old Etonian, as well as of the Friends of the Collections, the College Archives has acquired a fascinating 18th-century manuscript, Considerations concerning the present state of Eton School…. This controversial survey of ‘the state of Eton School’, was written around 1745 by John Burton, a Fellow (and later Vice-Provost) of Eton College, and a distinguished educationalist. This unpublished ‘Essay on Projected Improvements in Eton School’ was previously assumed to be lost.

A Fixture of College Library

Michael Meredith (MCM), former College Librarian, House Master and English Master, is still very much a presence in College Library as Librarian Emeritus. Indeed, his image is now a feature of the interior there. A portrait of Michael was recently completed by Roger Wagner (MAN ‘74), a celebrated painter, mainly of religious subjects. Wagner depicts his friend and former tutor standing before a table, where objects and archives relating to Michael’s scholarly focus, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, are arranged. The sitter is caught in an animated pose as he elucidates the material, his gesture familiar to many old boys and staff who have had the pleasure of Michael’s expert teaching.

Portrait by Eton Drawing Master

William Lorimer (PH, NAR, ‘75), a Friend of the Collections, has presented a portrait oil sketch of his cousin, Michael MeyseyWigley Severne (ACB-R, ‘40) as a boy at Eton. The work is by Wilfrid Blunt (1901–87), senior Drawing Master at the College from 1938. The completed work is in the collection of the Watts Gallery, Compton, where Blunt later served as curator. The sketch was presented by Lorimer in memory of both his cousin, Michael, and brother, Andrew Robert Lorimer (RDM ‘72), who spent some of their happiest hours in the Drawing Schools at Eton.

24 25 eton college collections Collections in Action eton college collections Collections in Action

Collections in Action What’s New

Friends Review

In June we were blessed with glorious weather for our ‘Garden Party’ event. Though what had been a sold-out event was affected by a rail strike, 32 intrepid Friends made it to Eton for a carousel of three talks followed by a delicious tea in Election Hall. In the Provost’s Garden, Philippa Martin, Keeper of Fine & Decorative Art, spoke about the history of that garden and the adjacent King of Siam’s Garden, established by Prajadhipok (Rama VII; at Eton 1908-10), as well as about the important sculptures there. In the Tower Gallery, George Fussey, Curator of the Natural History Museum, introduced the Friends to the Old Etonian Sir Joseph Banks, who accompanied James Cook on his first voyage around the world on HMS Endeavour and later became unofficial director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. He highlighted items in the exhibition To Botany Bay and Back and in the Banks Garden at Queen’s Schools, planted with species collected by Banks on the Endeavour voyage. In College Library, Archivist Georgina Robinson spoke about the Eton Master Henry Elford Luxmoore and the history of the garden he established on Tangier Island. Friends also had the opportunity to go on special tours of Luxmoore’s Garden and the Banks Garden.

Most unluckily, another rail strike struck in October on the day the Friends gathered for an evening celebrating Montague Rhodes James (1862-1936), Provost of Eton, medieval scholar and ghost story writer. Andrew Robinson of Eton’s history department gave a magnificent lecture on James’s life and writings. This was interspersed with readings by Peter Broad, actor and English beak. Afterwards, the Friends had an opportunity to explore an absorbing special display of manuscripts, photographs, books and documents relating to James’s ghost stories, his scholarly work as a medievalist, and his time at Eton as a boy and later Provost. As a further treat, the present Provost welcomed the Friends into his lodge to view some of his own collection of M.R. James material alongside the portrait of James painted by Gerald Kelly.

The Keeper of Fine & Decorative Art was also on hand to explain the background to this arresting portrait (also discussed in an article in the Summer 2022 issue of the Collections Journal), as well as related items from the College’s art collection.

On 8 February, 32 Friends joined an online event to hear two experts, Dr Monika Hinkel (SOAS) and Dr Thomas McAuley (University of Sheffield) introduce Japanese poetic and artistic traditions linked to the Niju¯ichidaishu¯ Japan’s imperial waka poetry anthology dating from the 10th to 15th centuries. Guests learned that waka was the most prodigious and influential literary form throughout the premodern period, that waka embodied the state’s cultural power and that the tradition is still evident in Japanese culture today. It is perhaps not surprising that a manuscript copy of this anthology was chosen as a gift to send to Eton by the Japanese Crown Prince Hirohito after visiting the College in 1921. We also learned that this poetry inspired visual and decorative artists, who even incorporated poems into their works on hand scrolls, album leaves, folding screens, kimonos and in many other forms. The authoritative and beautifully illustrated talks are available as a recording for Friends who were unable to attend the webinar live.

We are delighted that the Friends, along with a generous Old Etonian, were able to make possible the acquisition of a remarkable manuscript documenting teaching at Eton in the 1740s, previously thought to be lost (see page 25). In addition, the costumes conserved thanks to the Friends’ 2020 Montem Appeal have triumphantly returned to the College (see page 22), ready for display in the forthcoming Ad Montem exhibition, which will feature in the Friends’ next event in the summer. We hope to see many of you there.

Friends of the Collections Committee

Ad MonteM 8

11th May – 15th October 2023, Verey Gallery, Eton College 8

Montem, a peculiar and spectacular Eton ceremony, was celebrated for centuries until it was abolished in 1844. First recorded in 1561, by the 19th century it had become a grand pageant, in which Etonians processed in elaborate ceremonial and military dress from the College to Salt Hill in Slough.

This exhibition traces the traditional event through historic artwork, archival records and rare surviving examples of ornate Montem costume.

For information about visiting please see https://collections.etoncollege.com/visit-us/

The Richard H. Amis Bequest

The art collection of Richard H. Amis (K.S. ‘50) was recently bequeathed to Eton College and an exhibition of highlights is currently being prepared. Exhibits will include watercolours by significant British artists, such as a study of beech trees by J.M.W. Turner, J.R. Cozen’s view of the tomb of Cecilia Metella, near Rome, and a Cumbrian coastal scene by David Cox. An eclectic mix of further works on paper and oil paintings will also feature.

The exhibition will be at Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, St James’s, London, 14 - 27 September 2023, before relocating to the Verey Gallery, Eton College, in October 2023.

eton college collections Friends of the College Collections 26

Charles Turner (1774-1857), Lord Ingestre and Mr Mitford in Montem Costume, drawing, c.1820 (FDA-D.580-2010).

17th century-style costume, (MEL.451-2010).