Essays by Jennifer Samet

Dakin Hart

Berit Potter

Eric Firestone Press 2021

The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal

By Jennifer Samet

Beauty and danger coexist in Jeanne Reynal’s mosaics. As an artist formed by her Surrealist milieu, she was conscious of the charge garnered from harnessing these opposing forces. Her surfaces sparkle, ebb, and flow like topographies kissed by the elements. In order to convey these temporal realities, Reynal placed every stone, tile, and tessera into pigmented cement on a bias. Their sharp edges project out from the surface like a reminder that this work will not always sit still and behave.

From a young age, Reynal was conscious that she would not conform to societal and familial expectations. She was born into a wealthy family. Her mother was Adele Fitzgerald and her father Eugene Sugny Reynal. Notes that Reynal made for an autobiography make clear the tensions she felt as a young girl, and her often antagonistic relationship with her parents.1 She was educated completely by private tutors. She traveled extensively as a young person but went nowhere without a chaperone. Her father was known to be a severe, aristocratic man, who raised beagles and hunted. From him, Reynal inherited a love of animals and riding horses. Most importantly, she developed an adventurous spirit—a quality that radiates in her aesthetic and mosaic technique.

In 1927, Reynal was injured in a riding accident and sent to England to recuperate. This would set in motion the almost happenstance events leading to her work with mosaic. At a dinner party hosted by art collectors in London, she met Russian mosaicist Boris Anrep. Knowing that Reynal was on her way to Italy, he encouraged her to see mosaics in Torcello and Murano. 2 By 1930, Reynal

had joined Anrep in Paris where he was working on commissions for the floors of the Bank of England and the Greek Orthodox Cathedral, Bayswater, both in London. A worker in his atelier became sick, and Reynal was invited to take his place. She would spend the next eight years as Anrep’s apprentice.

By the time she returned to the United States in 1938, Reynal was resolved to create “a new art of mosaic, a contemporary and fresh look for this ancient medium.” 3 This goal was the catalyst driving her experimentation. Perhaps most importantly, she let go of the traditional “reverse method” of creating mosaics, in which stones were first glued to paper in a specific formation before being transferred. Reynal would work directly, by adding stones into the wet cement she mixed with powdered pigment. Improvisation, freedom, and intuition were hallmarks of her process and led to unexpected, singular works that radically challenge our expectations of mosaic.

Reynal hand cut all of her tesserae—the mosaic tiles— which were a mix of traditional Venetian glass, semiprecious stones, and pieces of shell. Next, she prepared a surface of pigmented cement and then scattered, or “seeded,” the tiles loosely, before using a leather hammer to embed them. 4 Hand cutting the tesserae would result in leftover dust from the cutting of the glass. She incorporated this dust by spreading it over the work.

In Paris, Reynal met and began to develop important friendships with Marcel Duchamp, as well as the Surrealist poets and painters, including André Breton and his wife, Elisa. This milieu was foundational to how Reynal would conceptualize her work. Breton, who was a trained

psychiatrist, published the Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, in which he advocated using free association and automatism to draw upon dreams and the private world of the mind. The resulting, unexpected imagery served as a rejection of traditional subject matter.

The tenets of Surrealism must have resonated with Reynal, in particular, the Surrealists’ desire to shed societal constructs and embrace unconscious thought. Her personal life was informed by her bold acts of rebellion from these very societal expectations. As a young woman, Reynal’s relationship with Anrep, which had developed into an affair, resulted in her father cutting off the allowance he provided her.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), (1915–23), one of Duchamp’s major works, is commonly considered an important precursor to Surrealism, with its suggestions of child’s play, intermixed with erotically charged forms, chance procedures, and a complete rethinking of material process. Reynal acquired Duchamp’s first perspectival study for The Large Glass —a drawing he made in 1913. 5 For her, applying the tenets of automatism to her work meant re-examining how mosaics were made.

In 1938, Reynal returned to the United States. Around the same time, at the onset of the Second World War, many Surrealists emigrated to the country as well. Reynal made a home for herself in San Francisco and began to develop her early work outside of the Anrep atelier. Her 1940s mosaics utilize a relatively structured composition and a flat placement of larger square tiles, as seen in Equation # 2 .

Equation #2 was among the works included in Reynal’s 1941 exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). By this time, both of her parents had passed away; her inheritance allowed her the financial and emotional freedom to fully pursue her work and her support of other artist friends. In a journal entry, she writes, “At first I was afraid of all this money—quite a generous amount—but soon I found out that I could help friends with it. Their needs were very similar to mine. Food, material, and a place to work was all that was needed.” 6

In this period, Reynal’s mosaics were mostly rooted in the functional and decorative tradition of the art form: she created mosaic tabletops and mantelpiece decorations, along with a mosaic floor, Great Field of Hands , in the outdoor garden of her companion Frederick Thompson’s property in Stinson Beach, California. She met and collaborated with Isamu Noguchi, as is discussed in Dakin Hart’s essay, in this volume. Her inheritance also allowed her to build a small house in Soda Springs, California, in the High Sierras. It is likely that some of the stones she used, such as obsidian, come from the volcanic earth of that region.

In 1946, Reynal went on a trip with André and Elisa Breton through the American Southwest, visiting Hopi, Zuni, and Navajo reservations. Reynal described this

experience—and the influence of Navajo sand painting— as formative in the development of her work:

I will never forget a six-week visit among the Navahoes in New Mexico, watching them create their images, from dawn until sunset, by dribbling colored sands through their palms and closed fingers, and varying the thickness of their lines according to how much they let their fingers open. So great was their concentration, and so involved were they in their work, they made very few errors and correction was virtually unnecessary. When sunset came, they wiped the whole thing out. From that moving experience, I learned to cut my material very small, whether it be minerals gathered in the desert, smalti from Venice, or marble or pumices from around the world. I discovered, incidentally, that the dust made in the cutting of stones or tesserae is of great use in intensifying background color.7

Indigenous art was of great interest to the Surrealists. For Reynal, it was an example of how intuition and spontaneity could play into her handling of tesserae. In 1946, she returned to New York, and the next year her

work was included in the infamous Bloodflames exhibition at the Hugo Gallery, where it was shown alongside that of Wifredo Lam, Roberto Matta, and Arshile Gorky, among other artists. The environment was designed by the radically innovative Austrian-American architect Frederick Kiesler, who created boomerang-shaped frames for Reynal’s work. The following year, Reynal was the subject of a solo exhibition at Julien Levy Gallery. Her pieces of this period, such as Young Friends (1949), utilize closely grouped tesserae, often from precious and semiprecious stones, where the outlines of anthropomorphic forms are captured as glittering lights and shadows. These works—often smaller in scale than those that would follow—were about discovery: the finding of form through a tactile, intimate process.

By the early 1950s Reynal was committed to using even smaller tesserae. She was influenced in this by Navajo sand painting, but the use of very small stones was also suggested by Gorky, who, along with his wife, Agnes “Mougouch” Gorky (née Magruder), had become a very close friend.

Reynal’s 1950s mosaics—such as Icarus Returned (1951) and Blue Window (1953)—unite a few major pictorial

frames

Frederick and Lillian Kiesler Private Foundation, Vienna

concerns. In her attempt to free mosaic from traditional associations with architectural decoration, she worked in a scale identified more often with painting, and created open forms across the surface. The curving, biomorphic forms are allusive but undefined, evoking figures, flora, animals, or motion. She also allowed the surface to be as much about the pigmented cement as it is about the tesserae. Some areas have no tesserae at all; instead she created color forms with troweled Sorel cement. Finally, Reynal established her work as rooted in the earth. The surfaces themselves are suggestive of topographies. The loose scattering of tesserae recalls the experience of walking on ever-shifting terrain. The very inclusion of hand-cut glass and stones collected on travels— embedded in such a way that they seem to thrust themselves toward us—is a concrete reminder that this all comes from the earth.

In this way, Reynal asserts her connection to painting, but also differentiates herself. While painting is an act that suggests a kind of alchemy—pigment (colored dirt) turned to image—Reynal privileges the earth as fundamental. Occasionally, entire large pieces of stone, particularly chunks of obsidian, serve to signify this.

Her 1950s mosaics, such as Now Is Winter (1951) and The Stallion Oat (1952), are rooted in mystery. We may sense the presence of certain elements, but these suggestions are left as open as the forms themselves. The act of discovery her works provoke in a viewer is reminiscent of the experience of observing Byzantine mosaics in dimly lit churches, where ever-changing patterns of illumination slowly reveal different pieces of the whole.

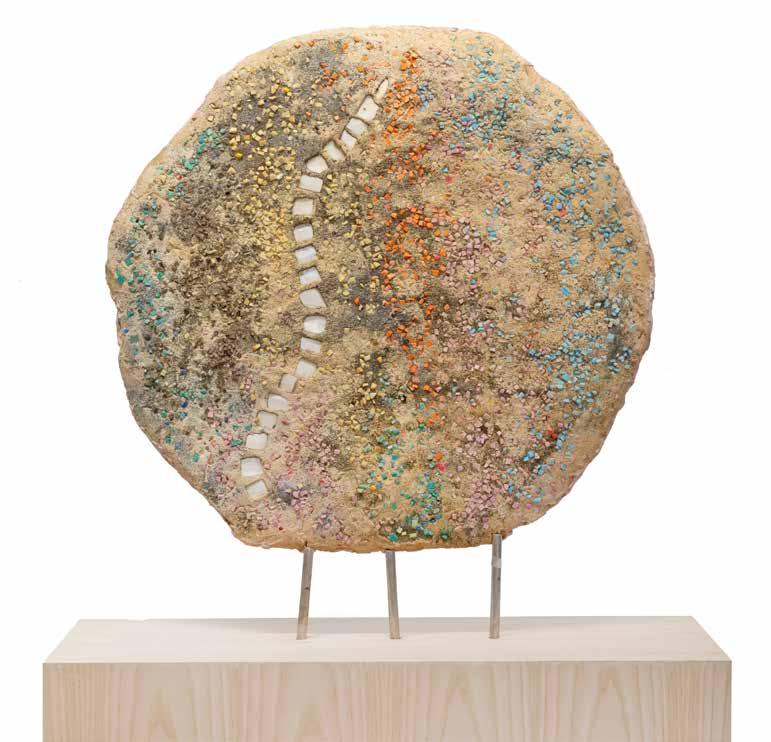

By the end of the 1950s, fields of primary monochromes replaced the somber earth tones of her earlier work. To achieve this, Reynal began using Portland cement, which gave her a whiter ground as a starting point. Her work became about the overall visual field, along with the shape of the support, and the play of light across the surfaces. These are “all-over” works, in the sense of Abstract Expressionism or Color Field painting. In 1959 she made Songs of the Tewa, a monumental hexagonal composition, and Rain Shadow, a diamondshaped work. They were exhibited at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York. These works were well ahead of their time in her use of shaped supports, which became popular in the art world in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

Shaped supports led Reynal in a new direction, to free-form disc mosaics. These, along with her shaped pieces, were exhibited twice in 1961. The first show was hosted by New York University’s Loeb Student Center. The second was held outdoors, on the property of sculptor Sidney Wolfson in Millbrook, New York. Marcel Breuer designed Wolfson’s home, incorporating a trailer

Jeanne Reynal with husband, the painter Thomas Sills, in front of a painting by Roberto Matta in their apartment, 1958. Photo by

into its structure. Reynal was connected to the area because she had lived there with her father after her parents separated, spending time riding her horses. This show provided an opportunity to explore the interaction between the mosaics and the outdoor landscape. Some discs were supported by natural rocks, away from walls. Outside, light was constantly shifting and often indirect. The surfaces became receptacles for light. Others were freestanding and double-sided. As Reynal worked with the circular shape, the discs gradually developed into concave and convex forms.

Early in her career, Reynal was concerned about how people categorized her mosaic. She saw her 1940s and ’50s works as paintings in stone, and she worked with complex figure-ground relationships and organizations of forms. By the 1960s, she moved more comfortably into mosaic as sculpture. In this way, she further untethered mosaic from the walls or the function of decorating surfaces.

Her 1969–71 totems are bold statements of the medium’s possibilities. She brought the craggy folds of her troweled cement into three dimensions with undulating columns, some more than ten feet tall. She incorporated large mother-of-pearl pieces. In the 1950s, Abstract Expressionists had intentionally freed painting from the limitations of the easel. Painting was theorized as an “arena in which to act” by Harold Rosenberg. 8 Reynal embraced this arena, including the weight, monumentality, and labor-intensive process of construction.

Reynal was a fearless artist, who continually reinvented her work. As her career progressed, her mosaics grew more monumental, more intuitive, more experimen -

Millbrook, New York. Curated by Sidney Wolfson, Outdoor View, 1961. Photographer unknown. Photo courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Library, Artist Files Collection

tal, and less attached to any preconceptions of the medium. In 1965, she was selected to create a mosaic for the State Capitol building in Lincoln, Nebraska. The experience is revealing of Reynal’s strong character. Her mosaic mural, The Blizzard of ’88 , was not well received by some members of the community—likely because of its abstraction. People even gathered to jeer at her while she worked to install the multi-panel piece. 9 And yet, she maintained her sense of the work’s importance and value. This was rewarded when she was invited, with the support of Norman Geske (the first director of the Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln) to contribute a second mural in 1967. Reynal was particularly pleased with this piece, The Planting of the Trees , saying it had “all the things I wanted in a mosaic: movement, light, and color, and a certain spiritual quality.” 10 She wrote in an autobiographical note, “It is a light and airy work, impressionist in feeling. Though the jeers continued, I felt remote from fear and worked with pleasure.” 11

In another autobiographical note, Reynal wrote, “Some of my best work comes from dreams. Others come while I work and dream. Anyone can gather that I am not an intellectual but depend entirely on feelings and animality for my statements in art, as well as life.” Reynal—buoyed by the philosophies of Surrealism

and Abstract Expressionism—channeled the forces of intuition and animality. As a result, her work is alive with risk and daring, light and effervescence. Hers is a singular contribution to modern art.

Notes

1. Toward the latter part of her life, Reynal had begun writing an autobiography, the drafts of which detail her upbringing, relationship with her family, and experiences as a member of the fine art community. These drafts were never published and were stored in Reynal’s personal archive.

2. Much of Reynal’s life was chronicled in the autobiographical section of her monograph, including her first encounter with mosaics through Anrep. Jeanne Reynal, “An Autobiographical Afterword,” in The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal (New York: George Wittenborn, Inc., 1964), 97.

3. Reynal, “An Autobiographical Afterword,” The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal, 98.

4. Mosaics: The Work of Jeanne Reynal, produced and edited by Paul Falkenberg (New York: 1968, 2020), digitized 16mm film.

5. For the image and more information on the work, see Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, vol. 2, 3rd ed. (New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 1997), 581. The date and circumstances of this acquisition or gift are unknown, although it was likely acquired by Reynal in the late 1940s. Michael Taylor, email to Jennifer Samet, 3 April 2021

6. Jeanne Reynal, draft of autobiography entry, Jeanne Reynal Archives.

7. Reynal, “An Autobiographical Afterword,” The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal, 99.

8. Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters,” ARTnews 51 (December 1952): 22–23, 48–50.

9. To these jeers, Reynal responded, “Why don’t Nebraskans know their history?” “‘Why Don’t Nebraskans Know History?’—Mosaic Installation Bothers Artist,” Omaha World-Herald, 17 December 1965.

10. The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal.

11. Jeanne Reynal, draft of autobiography entry, Box 14, Jeanne Reynal Archives.

Young Friends 1949

Winter Count 1963

Untitled 1959

60

Mother and Children Between Sun and Moon 1966

Africa: King and Queen 1970

121½

82

114

101½

By Dakin Hart, Senior Curator

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

What we know about the relationship between the sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) and the mosaicist Jeanne Reynal (1903–1983) is fairly thin. Noguchi’s glancing appearance in Reynal’s letters are, however, a useful source of information about him in the 1940s. From them we know, for example, that Noguchi stayed with her in San Francisco in the desperate, frenetic period following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941), when the sculptor became enmeshed in efforts to prevent, forestall, or weaken the impending onslaught of hysterical racism (official and unofficial) aimed at people of Japanese descent in the United States.1 Some of those activities, such as his co-organization of Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy in early 1942, took place in Reynal’s San Francisco studio. 2

Reynal was also one of Noguchi’s most important early patrons—a role she appears to have filled for many of her artist friends. Over the first decade of their acquaintance she amassed what was, at the time, the deepest and most varied collection of Noguchi’s work anywhere. The circumstances of those acquisitions are unknown, but they fit Reynal’s pattern of supporting her friends by collecting their work. The commitment her collection represented is important context for understanding her collaboration with Noguchi, which is probably more accurately described as a form of patronage. This impression is supported by a letter from Reynal to Agnes “Mougouch” Gorky, the wife of artist

Arshile Gorky, from December 1944. Noguchi appears to have cooked up a scheme—based on a then well-worn path in Nevada—to get Ann Matta divorced from her husband, the painter Roberto Matta, so she and Noguchi could marry, using Reynal’s money.

Isamu writes AGAIN that he wants to come west, get Ann divorced, spend some time in the mountains, make some tables and remarry or rather marry Ann. He adds by way of inducement that you and Arshile approve of this. I also approve highly, but I know it will cost more than the stipulated six hundred dollars or three tables (which I don’t want) and I am just not able to finance it. 3

Evidently, Reynal often measured repayment for loans and gifts of cash made to friends in terms of the number of artworks they might give her in exchange. 4 It is reasonable to conclude that all or some of the table bases Noguchi made for her before 1944 were produced as part of such an exchange.

Noguchi and Reynal appear to have made their first joint work in February 1942, when Noguchi was living with Reynal in San Francisco. On February 27, 1942, in a letter to Mougouch Gorky, Reynal wrote, “He [Isamu] has found the time to make a beautiful table base for me.” 5 Reynal’s motivation for wanting to work on a base by Noguchi is pretty clear. The pedestal base for The Lovers (1941), a

Jeanne Reynal, The Lovers, 1941. Reproduced in The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal (New York: George Wittenborn, Inc., 1964), 55 Isamu Noguchi and Jeanne Reynal, Table (no. 1), undated Jeanne Reynal, letter to Isamu Noguchi, sketch of Table (no. 1) 27 March (circa 1943). Photo courtesy of the archives of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York, NY

round tabletop she made a year earlier, looks like it could have been lifted from a tiki bar. Her exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art in the fall of 1941 also featured a table piece, Sausalito, executed on what looked like a generic piece of iron garden furniture.

The result of her first collaboration with Noguchi, which I will call Noguchi-Reynal table no. 1, must be the one listed in the exhibition brochure for Reynal’s March–April 1942 show at The Arts Club of Chicago. 6 It is almost certainly the one Noguchi then included a few months later in his exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art in July 1942.7 A sketch in a letter from Reynal to Noguchi dated March 27 provides definitive proof of the table’s shape and the top’s general design. The letter carries no year, but from internal evidence it can be dated with reasonable certainty to 1943. 8 In that same letter she offers to send him the table, so he can sell it in New York. Proof that she had already tried to sell it herself, as she had promised, has recently come to light in an advertisement she placed in the October 1942 issue of California Arts & Architecture

The physical form of Noguchi-Reynal tables no. 2 and no. 3 is more or less identical: low, three-legged things that look wings. (Table no. 2 is black while no. 3 is white.)

Noguchi-Reynal table no. 2 sold at Wright auction house in 2014 as “attributed to” Noguchi and Reynal due to a lack of documentation. 9 But a sheet recently found in Reynal’s papers that combines photographic prints of both black tables (nos. 1 and 2) on a single sheet of

typing paper offers strong evidence that the auctioned table is what it seems to be. And a whole series of advertisements Reynal placed in the November 1943, December 1943, and January 1944 issues of California Arts & Architecture would seem to settle the issue— although a difference in the copy between the first and final two ads opens the question of whether Noguchi made the table himself or only designed it.

The provenance of table no. 3—the example in the present exhibition, which features a multicolored mosaic—has always been considered secure because it remained with the Reynal-Sills family, from whom it was acquired by The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. A period photograph has recently come to light, in which it is jointly attributed to Reynal and Noguchi (again as the designer of the base) in a May 1944 trend piece in Architectural Forum on mosaics.10

Isamu Noguchi and Jeanne Reynal, Table (no. 2), circa 1942–45. Magnesite and mosaic tiles, 38 x 42 x 13 inches. Private collection Isamu Noguchi and Jeanne Reynal, Table (no. 3), circa 1942–45. Magnesite and mosaic tiles, 13 ¼ x 48 x 35¾ inches. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / ARS; museum purchase, 2010

The collaboration between Noguchi and Reynal seems to have taken the form Noguchi preferred, in which the collaborators do their parts independently, more or less without interference, and the result ends up being more than the sum of its parts. Noguchi made hyper-modern, bio-aerodynamic table bases. Reynal made neoclassical mosaic tops for them. The resultant tables evoke a notional futuristic Mediterranean culture existing in what Noguchi called, in the context of the theater, “timeless time.” 11 Reynal’s design for the top of Noguchi-Reynal table no. 1 falls somewhere between the octopus on a Mycenaean vase, a schematic of Loie Fuller’s flowing dance costumes, and a nebulous rendering of space-time. More importantly, it epitomizes, if only seminally at this stage in Reynal’s attempt to modernize mosaic, an artistic mission later explained by Noguchi, speaking of his Akari lanterns, as “the true development of an old tradition.” 12 In response to a question about what makes for successful collaboration, Noguchi once told an interviewer:

I think if what you do and what somebody else does happens to coincide so that your activities are needful of each other, differences become obliterated. I think my theater sets have been good collaborations. I’ve been very fortunate in the people who I’ve collaborated with. They did what I had hoped they would do. I hope I contributed what they hoped to get from me [ . . . ] When each contributes and gives something, that’s of course collaboration.13

This type of serial, parallel collaboration apparently worked well for Reynal too. Speaking with an interviewer later in life, she explained why she had never played with

Advertisements for NoguchiReynal Table (no. 2), California Arts & Architecture 60 (November 1943): 10

her four siblings: “I was remote. I read a great deal. The treehouse was too cooperative for my taste. In fact, all the games were too cooperative. I’ve always been a person who did things by myself.” 14

Noguchi wanted, as he often said, to enter the “stream of time,” 15 contributing to the accumulation of culture and civilization by collaboration. Much of his work consisted of trying to make beaches from grains of sand. “I don’t look at art as something separate and sacrosanct. It’s part of usefulness. It’s probably why I was able to do those things,” 16 he said in 1977, referring to his dance sets for Martha Graham. Noguchi understood that culture writ large is, by definition, the creation of a grand, pluralistic collaboration. His regular attempts to become anonymous, to merge so seamlessly into the culture as to become invisible (an oft-stated ambition) or, in other words, to become continuous with all of us, his collaborators in culture, were his most lasting contributions to the theory and practice of art making. That is nowhere more visible than in the toweringly modest ambition of the tables he made with his friend and patron Jeanne Reynal.

Notes

This essay is an abridged version of a Digital Feature by the same title on noguchi.org

1. Jeanne Reynal, letter to Agnes Gorky, 27 February 1942, Jeanne Reynal Papers, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York.

2. Isamu Noguchi, oral history interview by Paul Cummings, 7 November–26 December 1973, transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/ oral-history-interview-isamu-noguchi-11906#transcript.

3. Jeanne Reynal, letter to Agnes Gorky, 1 December 1944, Jeanne Reynal Papers, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York.

4. Jeanne Reynal, letter to Agnes Gorky, 15 May 1944, Jeanne Reynal Papers, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Reynal offers in this letter to lend the Gorkys $2,000, which they can repay over twenty years at zero interest, or with four of his paintings.

5. Jeanne Reynal, letter to Agnes Gorky, 27 February 1942, Jeanne Reynal Papers, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York.

6. Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal (Chicago: The Arts Club of Chicago, 1942). Exhibition brochure published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same title presented by The Arts Club of Chicago, 31 March–20 April 1942.

7. “Memorandum on Exhibition of IN,” 1942, MS_EXH_021_009, The Noguchi Museum Archives; San Francisco Museum of Art receipt of shipment, 10 September 1942, MS_EXH_021_011, The Noguchi Museum Archives.

8. Jeanne Reynal, letter to Isamu Noguchi, 27 March [circa 1943], MS_ COR_311_001, The Noguchi Museum Archives. This sketch has sometimes been used, inaccurately, to attest to the authenticity of Noguchi-Reynal table no. 2, which it does not resemble. It is unclear why Reynal felt the need to sketch the table, as if Noguchi would otherwise be confused. This could be taken as evidence that suggests other tables had already been made.

9. Wright, “Lot 154: Attributed to Isamu Noguchi and Jeanne Reynal, Coffee Table,” “Art + Design,” 23 September 2014, https://www.wright20. com/auctions/2014/09/art-design/154.

10. “Forum of Events: Mosaics,” Architectural Forum 80 (May 1944): 4.

11. Isamu Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World (London: Thames & Hudson, 1967), 123.

12. Isamu Noguchi, “Akari,” Arts & Architecture 72, no. 5 (May 1955): 31.

13. Isamu Noguchi, “A Conversation with Isamu Noguchi,” interview by Nancy Miller, 8 July 1977, transcript, MS_WRI_046_001, The Noguchi Museum Archives, 7.

14. Jeanne Reynal and Eleanor Munro, “Jeanne Reynal,” in Originals: American Women Artists , rev. ed. (New York: Da Capo Press, 2000), 180.

15. Isamu Noguchi, The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), 50.

16. Miller and Noguchi, “A Conversation,” 10.

By Berit Potter, Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum & Gallery Practices, and Museum & Gallery Practices Certificate Coordinator, Humboldt State University

When Jeanne Reynal moved to Montgomery Street in San Francisco in 1939, she forged an important relationship with the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, SFMOMA) and its director, Grace McCann Morley. While Reynal lived in San Francisco, and even after she moved to Soda Springs, California, near Lake Tahoe, she and Morley frequently exchanged letters that document their collaborations and close bond. The two fiercely independent women shared few similarities in terms of their backgrounds. Morley was raised in rural St. Helena, California, and traveled abroad for the first time when she received a scholarship to pursue doctoral work at the University of Paris. Reynal was born into a wealthy home in White Plains, New York, studied under a Cambridge-educated tutor, and experienced the luxury of travel, including summering in Palermo, Sicily, with her brother Eugene.1 Despite their differences, Reynal and Morley were united by their commitment to contemporary art and artists, and they each deeply benefited from their relationship. Morley expressed her dedication to fledgling artists by organizing exhibitions of their work, including Jackson Pollock’s first museum exhibition, and Reynal demonstrated her commitment by making significant purchases from artists, many of whom were her friends, such as Joseph Cornell, Arshile Gorky, Wolfgang Paalen, Alice Rahon, and countless others.

When Reynal moved to San Francisco, SFMOMA was a burgeoning museum; it had opened in its first permanent home, on the top floor of the Veterans Building behind San Francisco’s City Hall, just five years prior. While living in California, Reynal made

several important contributions to SFMOMA in the form of donations, but perhaps the greatest gift she gave the museum was the counsel she offered Morley. 2 Reynal was well connected with artists in New York and Morley had little time or financial means to make frequent trips to the East Coast. As Morley wrote to Reynal, “I am very glad to have you make suggestions of people you think especially interesting. We may not always be able to bring their work out immediately, but it helps to have opinions and to know about names. I naturally cannot get East as often as I should like.” 3 Morley trusted Reynal, solicited her advice, and described her to Peggy Guggenheim as “always a sensitive appreciator of others’ work.” 4 Reynal often approached Morley with exhibition ideas, such as a group show involving the work of Stanley William Hayter, Jacqueline Lamba, Roberto Matta, Wolfgang Paalen, and Alice Rahon. 5 While Morley was unable to organize the show as Reynal proposed, Morley exhibited every artist who Reynal recommended.

In addition to providing recommendations for exhibitions, Reynal made important gifts to the museum’s early collection. Together, Reynal and Morley acquired Jacqueline Lamba’s La Galere and donated it to the museum. Reynal also purchased David Hare’s Dead Elephant for SFMOMA.6

These gifts followed Reynal’s donation of Gorky’s Enigmatic Combat of 1936–37, which coincided with SFMOMA’s 1941 exhibition Paintings by Arshile Gorky. At the time, the museum possessed a small collection, no endowment, and extremely limited funds for acquisitions, which made Reynal’s gifts even more meaningful.

In 1945, Morley offered Jackson Pollock his first museum exhibition, but only after Reynal purchased Pollock’s The

Magic Mirror (1941) from Peggy Guggenheim and recommended his work. Morley wrote to Reynal requesting to see the painting: “Miss Guggenheim wrote me about Jackson Pollock. I do not know his work of course and I am very anxious to. She has promised to send me some photographs, but I shall count on your letting me see the one you purchased some time when you are in town.” 7 Reynal responded, “I must say I am interested in having your opinion. I cannot say that it has been liked. Though I continue to find it of interest,” and described “its iridescent pastel quality” in the morning sun. 8 Morley must have been impressed by The Magic Mirror. In addition to presenting the exhibition Jackson Pollock at SFMOMA, she utilized the museum’s limited Albert Bender Bequest Fund to purchase Pollock’s Guardians of the Secret (1943) for the collection. Since the museum lacked a strong permanent collection, Morley relied on local collectors like Reynal for important loans, including The Magic Mirror, which was included in Jackson Pollock . Writing to Reynal, Morley remarked, “We included your painting, and are very grateful [ . . . ] With yours [The Magic Mirror] included in local collections we have at least two good examples in the region from which we can draw.” 9

Exhibition announcement for Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal, San Francisco Museum of Art, 1941

San Francisco served as fertile ground where Reynal challenged the restrictions placed on her mosaic practice, and Morley supported her growth. Reynal exhibited her work at several Bay Area institutions, including the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Mills College Art Museum, and United American Artists’ Gallery, yet none more than SFMOMA. She regularly contributed work to San Francisco Art Association’s (SFAA) annual exhibitions, which were hosted by SFMOMA, but juried and curated by SFAA. Reynal exhibited in every annual between 1942 and 1946, but in 1944 she withdrew her mosaic after discovering that it had been accepted into the exhibition by the sculpture committee instead of the painting committee. By the time Morley learned about the mix-up, nothing could be done to remedy the situation. Reynal exchanged several letters with Morley on the subject, arguing that her mosaic should be considered “a painting in stone,” rather than a sculpture, and therefore should have been assessed by the painting committee.10 Through both letters and phone calls, Morley tried to convince Reynal to allow SFAA to exhibit the mosaic since its removal would be a loss to the exhibition, but Reynal decided that she could not “acquiesce to the showing of the mosaic in a category where I do not feel it belongs.” 11 Although somewhat “baffled by [Reynal’s] objections,” Morley advocated on her behalf.12 Ultimately, Morley agreed with Reynal’s assertion that “the classifications are outmoded and in consideration of the trend of contemporary art, even a little bit silly.” 13 Morley sent Reynal’s letters to Eldridge Spencer, SFAA’s President, and recommended that the association should “broaden

the wording” in reference to materials on its exhibition entry forms and artists should determine the media classification of their work.14 Reynal’s challenges to SFAA, which were supported by Morley, encouraged the association to reconsider the bounds of antiquated media categories in order to better support contemporary art and artists.

Morley’s representation of Reynal’s mosaics, oscollages, and watercolors through exhibitions at SFMOMA challenged the expectations of local art critic Alfred Frankenstein, especially his conviction in the limitations of mosaics as “applied art” and Reynal as a decorative artist. When Morley arranged Reynal’s first one-woman show, Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal, in 1941, Frankenstein did not offer the exhibition much attention in his column, aside from describing Reynal’s mosaics as “carefully and cleverly designed for homes and gardens, exploiting

highly sophisticated ‘modern’ designs . . . the integrity of the whole as decoration is always preserved.” 15 A year later, Morley’s assistant, Douglas MacAgy, included Reynal in his exhibition 50 Paintings by 10 Artists , and Frankenstein persisted in his appraisal of Reynal’s work as merely decorative. In his critique, Frankenstein referred to the artist’s “swiftly drawn abstractions” as “craft-like” and “in the decorative tradition of ‘applied art’ as befits one who has spent much time making mosaics for architectural ornament.” 16

In reviewing Paintings by Jeanne Reynal of 1943, however, Frankenstein’s evaluation of Reynal’s work shifted. He still noted her use of design, yet he described her new body of work, the “oscollages,” assemblages made from bone, as refreshing departures from abstractions made by her predecessors. According to Frankenstein, rather than creating “played out” representations of

“guitars, bottles, pipes and fruit dishes,” Reynal showed the viewer through her oscollages “how right the world may be in design if you only know where to look for it.” 17 For Frankenstein, Reynal’s watercolors were “full of invention” and her oscollage Mama Where is Papa?, “wherein the bones are stretched along a painted horizon,” had a “special tang.” 18

While Reynal’s work proved to Frankenstein that a mosaicist could move beyond so-called decorative art, his reappraisal also validated one of Morley’s guiding curatorial principles: “it is very helpful to have repeated appearances” of artists’ work “in different contexts” especially when exhibiting “unfamiliar material.” 19 Morley first exhibited Reynal’s mosaics alongside three additional exhibitions, Sculptures by Ruth Cravath, Paintings by Ellwood Graham , and a group show, San Francisco Painters . Presenting Reynal’s work in conjunction with three exhibits that showcased local artists assertively positioned her within the San Francisco art community and functioned as an important debut of her work at SFMOMA. 20 When Morley organized Reynal’s second solo exhibition at the museum, it followed Paintings by Jean Varda, a show representing the work of a fellow mosaicist and Surrealist affiliate, and was featured alongside the abstract and mystical transcendentalist landscapes of Agnes Pelton. No doubt this combination of exhibitions helped to both demonstrate and contextualize Reynal’s Surrealist connections, which Frankenstein alluded to in his article when he described the oscollages as akin to “the surrealists’ ‘found objects’ . . . half serious, half smiling affairs. . . .” 21 Through Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal and Paintings by Jeanne Reynal, and their companion exhibitions, Morley made clear to both Frankenstein and the museum’s public the strength and distinctiveness of Reynal’s work within the San Francisco art community, as well as Surrealism and its adaptations in the United States.

Reynal and Morley developed an important relationship in which they supported each other’s careers as well as other avant-garde artists and the museum. This shared collaborative sprit and commitment to contemporary art cultivated their friendship, which benefited their creative and professional endeavors as well as SFMOMA and its communities.

Notes

1. Remarkably, both Reynal and Morley authored their own autobiographies. Reynal’s is included in The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal and Morley describes much of her life and career in an extensive oral history conducted by Suzanne B. Riess. Riess, “Grace L. McCann Morley: Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art: An Interview” (Berkeley: University of California, General Library, Regional Cultural History Project, 1960).

2. Reynal’s financial contributions to the museum are documented through thank-you letters Morley sent to Reynal. See, for instance, Grace McCann Morley, letter to Jeanne Reynal, 3 June 1941, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 43, Folder 4, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

3. Morley, letter to Reynal, 20 December 1943, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 41, Folder 12, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

4. Morley, letter to Peggy Guggenheim, 3 October 1945, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 55, Folder 1, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

5. Reynal, letter to Morley, 28 February 1945, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 65, Folder 9, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

6. SFMOMA deaccessioned La Galere in 1976.

7. Morley, letter to Reynal, 20 December 1943, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 54, Folder 6, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

8. Reynal, letter to Morley, 7 February 1944, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 59, Folder 5, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

9. Morley, letter to Reynal, 4 October 1945, Office of the Director 1935–1958, Administrative Records, Box 65, Folder 8, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Research Library, San Francisco.

10. Reynal, letter to Morley, 11 September 1944, San Francisco Art Institute Archives, Archival Artists File: Jeanne Reynal.

11. Ibid.

12. In a lengthy letter Morley explained to Reynal that she would understand Reynal’s concern if SFAA had classified the mosaic as decorative art, however, since it was admitted as fine art and would ultimately be hung as a painting, the point Reynal was trying to make eluded her. Even so, she agreed that Reynal should be the one to determine the media classification of her work, not SFAA. Morley, letter to Reynal, 17 September 1944, San Francisco Art Institute Archives, Archival Artists File: Jeanne Reynal.

13. Reynal, letter to Eldridge Spencer, 25 September 1944, San Francisco Art Institute Archives, Archival Artists File: Jeanne Reynal.

14. Morley, letter to Spencer, 17 September 1944, San Francisco Art Institute Archives, Archival Artists File: Jeanne Reynal.

15. Alfred Frankenstein, “99 Pictures of a ‘Wonderous World,’” 11 May 1941, The San Francisco Chronicle , 27.

16. Alfred Frankenstein, “Solving Group Show Problems,’” 26 July 1942, The San Francisco Chronicle , 35.

17. Alfred Frankenstein, “Jeanne Reynal Replaces Guitars with Some Bones,’” 8 August 1943, The San Francisco Chronicle , 29.

18. Still, in the same article Frankenstein described Reynal’s use of French titles as “a bit snobbish.”

19. Morley, letter to Klaus Perls, 13 May 1944, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, Box 21, Folder 6, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Archives and Library, San Francisco. Morley, letter to José Gómez-Sicre, 21 April 1944, José Gómez Sicre Papers, Box 7, Folder 3, Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries.

20. Graham lived in Monterey County but frequently exhibited in San Francisco.

21. Frankenstein, “Jeanne Reynal Replaces Guitars with Some Bones.”

b. 1903 White Plains, New York

d. 1983 New York, New York

Education

1930–38 Boris Anrep Studio, Paris, France

Select Solo Exhibitions

2021 Mosaic is Light: Works by Jeanne Reynal, 1940–1970 , Eric Firestone Gallery, New York, NY

2009 Jeanne Reynal and Thomas Sills , Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, NY

1979 Some Animals , Bodley Gallery, New York, NY

1976 Of People , Two-Person Exhibition with Ethel Schwabacher, Bodley Gallery, New York, NY

1971 Jeanne Reynal Sculpture , Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, NY Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal , Newport Art Association, Newport, RI

1966 Dord Fitz Gallery, Amarillo, TX

1965–66 Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal, San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, CA. Exhibition traveled to Boston, MA; Montreal, Canada; Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, NE; and Amarillo, Texas

1965 San Francisco Museum of Art. Exhibition traveled to Boston, MA; Montreal, Canada; Lincoln, NE; and Amarillo, Texas

1964 PVI Gallery, New York, NY

1963 Jeanne Reynal and Thomas Sills, The New School, New York, NY

1961 Jeanne Reynal , Loeb Student Center, New York University, New York, NY

Outdoor View, Millbrook, NY

1959 Jeanne Reynal Mosaic Murals , Section Eleven, Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, NY

1957 Recent Mosaics , Mills College of Education Gallery, New York, NY

1956/54 Jeanne Reynal , Stable Gallery, New York, NY

1951 Jeanne Reynal , Iolas Gallery, New York, NY

1950 Jeanne Reynal, Hugo Gallery, New York, NY

1943 Paintings by Jeanne Reynal , San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, CA

1942 Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal , The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL

1941 Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal , San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, CA

1940 Walker Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

Select Group Exhibitions

2015 Soldier, Spectre, Shaman: The Figure and the Second World War, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2012 In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States , Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

2010–11 On Becoming an Artist: Isamu Noguchi and His Contemporaries: 1923–1960 , The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, Long Island City, NY

2010 Abstract Expressionist New York: Ideas Not Theories: Artists and the Club, 1941–1962 , Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2005 Betty Parsons & the Women , Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, NY

1979 Visual Arts Coalition Women Painters and Sculptors , Connecticut College, New London, CT

1977 Surrealism and American Art: 1931–1947, Rutgers University Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NJ

1976 Visual Artists Coalition, Cork Gallery, Lincoln Center, New York, NY

1973 Women Choose Women , Free Public Library, Fair Lawn, NJ

1971 Sculpture: The Artists Plus Discoveries , Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, NY

1965 Women Artist of America 1707–1964 , Newark Museum, Newark, NJ

1964 Artists For Core , Gallery of American Federation of Arts, New York, NY

1962 Community and Change: 45 American Abstract Painters , Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT

Seattle World’s Fair, Seattle, WA

1961 Survey of the Permanent Collection , Addison Gallery of American Art, New York, NY

1960 17 of the Women: Tops in Art , Dord Fitz Gallery, Amarillo, TX

1957 Annual Exhibition of Sculpture, Paintings, Watercolors , Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

1956 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Drawings (November–January), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Drawings (April–June), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

1955 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Paintings, Sculpture, Watercolors and Drawings , Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Painters of the Village , New School for Social Research, New York, NY

1954 XXVth, Anniversary Exhibition: Paintings from the Museum Collection , Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Drawings , Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, Watercolors and Drawings , Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

1951 Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America , Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

1947 Le Surrealisme en 1947, Paris, France Bloodflames , Hugo Gallery, New York, NY

1942–46 Annual Show, San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, CA

Selected Commissions

1967 Reredos for the Ss. Joachim and Anne Church, Queens, NY

1966 The Planting of the Trees , Mural for Nebraska State Capitol, Lincoln, NE

1965 The Blizzard of ’88 , Mural for Nebraska State Capitol, Lincoln, NE

1962 Convex wall, Moore and Salisbury, architects, Cliff House, Avon, CT Freestanding wall, Paul Damaz, architect, Our Lady of Florida monastery and retreat house, Palm Beach, FL

1960 Mural entrance piece, Mr. and Mrs. Maxwell McKnight

1959 Rosy Fingered Dawn , Ford Foundation Program for Adult Education, White Plains, NY

1941 Great Field of Hands , Garden floor, Frederick Thompson, Stinson Beach, CA

Films

1968 The Work of Jeanne Reynal , produced and edited by Paul Falkenberg, New York, NY.

1964 Chess Games with Marcel Duchamp , directed by Jean Marie Drot, Paris, France.

Bibliography

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1951.

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1952, cat. no. 49.

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1953, p. 12.

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1954.

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1956, p. 8.

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1956, p. 4.

Annual Exhibition: Sculpture, paintings, watercolors . Exh. Cat., The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1957, p. 33.

Ashton, Dore, “About Art and Artists,” The New York Times , March 1, 1956.

Ashton, Dore, “Jeanne Reynal’s Mosaics,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 16, December 1956, p. 23.

Ashton, Dore, “Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal,” The New York Times, January 1957.

Ater, Jean, “Lecture Saturday to Open Exhibit by Mosaic Artist,” Amarillo Globe-Times , December 1966.

Atirnomis, ARTS Magazine , March 1971, p. 59.

Betty Parsons & the Women . Exh. Cat., Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, NY, 2005.

Bittermann, Eleanor, Art and Modern Architecture (New York, NY: Forgotten Press, 2017).

Breuning, Margaret, “Jeanne Reynal,” Art Digest , Vol. 25, November 1, 1950, p. 21.

Calas, Nicolas, Bloodflames. Exh. Cat., Hugo Gallery, New York, NY, 1947, p. 15.

Campbell, Lawrence, “Jeanne Reynal,” ARTnews, Vol. 60, November 1961, p. 34.

Campbell, Lawrence, “Jeanne Reynal,” ARTnews , Vol. 70, March 1971, p. 60.

Campbell, Lawrence, “Jeanne Reynal: The Mosaic as Architecture,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 22, no. 4, 1962, pp. 16–19, 48–49, ill., cover image.

Campbell, Lawrence, The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal (New York, NY: George Wittenberg, Inc., 1964).

Clement, Helen, “65th Art Assn. Annual Opens at S.F. Museum,” Oakland Tribune , Sunday, November 11, 1945, p. 30.

Cotter, Holland, “An Artist and Dealer and the Women She Promoted,” The New York Times , July 13, 2005.

de Kooning, Elaine, “Jeanne Reynal: Mosaic Portraits,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 36, no. 4, August 1976, pp.32–35, ill., cover image.

de Kooning, Elaine, “Reynal Makes a Mosaic,” ARTnews , Vol. 52, December 1953. pp. 34–37, 51–53.

de Kooning, Elaine and Rosalyn Drexler, “Dialogue” ARTnews , January 1971, p. 63.

Drexler, Arthur, “Mosaicist,” Interiors, March 1950, pp. 80–85.

Edelson, Elihu, “Artistically Speaking,” The Sarasota Citizen , 1964. Entenza, John, “Mosaics: Jeanne Reynal,” Arts and Architecture , Vol. 61, August 1944, pp. 26, 39.

Feinstein, Sam, “57th Street,” Art Digest , Vol. 28, January 1, 1954, pp. 16–19. Fort, Susan Ilene, In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States. Exh. Cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, 2012.

Frank, Peter, “New York Art Round Up,” Columbia Daily Spectator, March 11, 1971.

Fremantle, Christopher E., “New York Commentary,” Studio , Vol. 147, April 1954, pp. 121–22, ill. p. 122.

Gabriel, Mary, Ninth Street Women (New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company, 2018), p. 128.

Genauer, Emily, “Abstract Mosaics,” Art Digest , Vol. 25, November 15, 1948, p. 40.

Gerdts, William H., Women Artists of America, 1707–1964. Exh. Cat., Newark Museum, Newark, NJ, 1964, p. 26.

Goodman, Jonathan, “Jeanne Reynal and Thomas Sills,” Art in America , March 2009, p. 143.

Guest, Barbara, “Jeanne Reynal,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 31, no. 3, June 1971, pp. 40–43, ill., cover image.

Hare, David, “Mosaics/Between Stones Is,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 39, April 1979, pp. 60–61.

Herrera, Hayden, Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003).

Jacobs, Jay, “Mosaicist,” The Art Gallery, March 1971.

Kafka, Barbara Poses, “Art and Architecture: Four Recent Commissions,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 28, January/February 1968, pp. 20–23.

Katz, Paul, Art Now: New York, Vol. 4, no. 1, March 1972.

K. L., “Jeanne Reynal and Thomas Sills,” ARTnews , Vol. 61, January 1963, p. 11.

Lindstrom, Charles, “News and Comment on Art, Jeanne Reynal Mosaics,” Architect and Engineer, Vol. 145, May 1941, p. 9.

Mellow, James R., “Jeanne Reynal,” Arts Magazine , Vol. 30, April 1956, p. 57.

Meyer, Arline J., “Jeanne Reynal,” ARTnews, Vol. 58, October 1959, p. 14, ill. p. 14.

Moesangl, Paul, “Jeanne Reynal Is Virtuoso of Mosaic Art,” The Baytown Sun , Vol. 30, July 30, 1954.

“More Art Than Money,” Vogue , December 1959, color ill.

“Mosaics,” Art and Architecture , August 1944, pp. 26–29, ill.

“Mosaics,” Architectural Forum , Vol. 80, May 1944, p. 21, ill. p. 21.

Mosaics by Jeanne Reynal . Exh. Cat., The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 1942.

Munro, Eleanor, Originals: American Women Artists (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979), pp. 178–88.

Negrosh, Leon, “Jeanne Reynal,” Craft Horizons , Vol. 31, April 1971, p. 54, ill. p. 54.

“New Mosaic Murals by Jeanne Reynal,” Interiors , October 1959, p. 12.

Porter, Fairfield, “Jeanne Reynal,” ARTnews , Vol. 52, December 1953, p. 41.

“Reynal Mosaics at S.F. Museum,” Oakland Tribune , May 18, 1941, p. 23.

Seckler, Dorothy, “Jeanne Reynal,” ARTnews, Vol. 49, April 1950, p. 46, ill. p. 46.

Sixty-Fourth Annual Exhibition San Francisco Art Association . Exh. Cat., San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, CA, 1944.

Slivka, Rose, “Craftsmen Since 1950,” The Britannica Encyclopedia of American Art , pp. 264–65, ill.

Stein, Judith E., and Ann-Sargent Wooster in Making Their Mark: Women Artists Move into the Mainstream, 1970–85 . Exh. Cat., Cincinnati Art Museum. New York, 1989, pp. 123, 291, colorplate 109.

Tallmer, Jerry, “Crackling Stones and Wrinkling Up Metal,” The Village Voice , 1979.

Tyler, Parker, “Jeanne Reynal,” ARTnews , Vol. 55, January 1957, p. 24. Tyler, Parker, Review of Jeanne Reynal at Stable Gallery, ARTnews , Vol. 55, March 1956, p. 54.

Von Lintel, Amy and Bonnie Roos, Three Women Artists: Expanding Abstract Expressionism in the American Wes t (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2021).

“‘Why Don’t Nebraskans Know History?’—Mosaic Installation Bothers Artist,” Omaha World-Herald , Friday, December 17, 1965.

Wolf Amy, On Becoming An Artist: Isamu Noguchi and His Contemporaries 1922–1960 . Exh. Cat., The Noguchi Museum, Long Island City, NY, 2010, ill. p. 84.

Women Choose Women . Exh. Cat., Women in the Arts, The New York Cultural Center, New York, NY, 1973.

Visual Artists Coalition Exhibition. Exh. Cat., Connecticut College Cummings Center, New London, CT, 1979, ill. p. 18.

Collections

Amarillo Museum of Art, Amarillo, TX

Denver Museum of Modern Art, Denver, CO

Ford Foundation, White Plains, NY

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

The Menil Collection, Houston, TX

Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

New York University, New York, NY

Oklahoma State University Museum of Art, Stillwater, OK

Phillips Academy, Andover, MA

Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, Lincoln, NE

St. Lawrence University, Richard F. Brush Art Gallery, Canton, NY

Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY

Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

We thank Kenneth Sills for his assistance in making this exhibition possible, for trusting us to exhibit this historic work, and for making the Jeanne Reynal archives accessible.

Thank you to Berit Potter, Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum & Gallery Practices, and Museum & Gallery Practices Certificate Coordinator, Humboldt State University; and Dakin Hart, Senior Curator, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, for their insightful essays on Jeanne Reynal, and for sharing important historical information along the course of the project.

Thank you to Amy von Lintel, PhD, Associate Professor of Art History, West Texas A&M University, and co-author with Bonnie Roos of the forthcoming book, Three Women Artists: Expanding Abstract Expressionism in the American West , which includes a chapter on Jeanne Reynal.

In addition, all of the following individuals and scholars shared knowledge and information, so that we could tell the story of Jeanne Reynal: Otis Coleman; Matt Mullican; Parker Field, Managing Director, The Arshile Gorky Foundation; Maro Gorky and Matthew Spender; Claire Howard, Assistant Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art. Thank you to several individuals at The Menil Collection: Michelle White, Senior Curator; David Aylsworth, Collections Registrar; and Lisa Barkley, Menil Archives. Thanks to Michael Taylor, Chief Curator and Deputy Director for Art and Education, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; Antoine Monnier and Séverine Gossart, Association Marcel Duchamp; Michael Duncan; Margaret Huang, Martha Hamilton Morris Archivist, Philadelphia Museum of Art; Abby Bridge, Special Collections Cataloguer, and Peggy Tran-Le, Archivist/Records Manager, both at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

I would like to personally thank the entire gallery staff for their tireless work to produce every aspect of this historic exhibition. None of this would be possible without them!

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

MOSAIC IS LIGHT: WORK BY JEANNE REYNAL, 1940–1970

January 28–April 10, 2021 on view at Eric Firestone Gallery

40 Great Jones Street, New York, NY

ISBN: 978-0-578-91658-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021910155

Cover: Reincarnation Lullabies, detail, 1959, see page 30

Frontispiece: Jeanne Reynal working at her studio on the property of Frederick Thompson, Stinson Beach, CA, 1941

Publication copyright © 2021 Eric Firestone Press

“Intuition and Animality: The Mosaics of Jeanne Reynal”

copyright © 2021 Jennifer Samet

“Jeanne Reynal and Isamu Noguchi: What Collaboration

Looks Like” copyright © 2021 Dakin Hart

“Full of Invention: The Friendship and Collaborations of Jeanne Reynal and Grace McCann Morley” copyright © 2021 Berit Potter

Unless otherwise indicated, all photos are courtesy Reynal Archive © Estate of Jeanne Reynal / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Reproduction of contents prohibited All rights reserved

Published by

Eric Firestone Press

4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937

Eric Firestone Gallery

40 Great Jones Street New York, NY 10012

646-998-3727

4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937

631-604-2386

ericfirestonegallery.com

Principal: Eric Firestone

Director of Research: Jennifer Samet

Project Management: Kara Winters

Principal Photography: Jenny Gorman

Copyeditor: Natalie Haddad

Design: Russell Hassell, New York

Printing: Puritan Capital, New Hampshire

MOSAIC IS LIGHT, JEANNE REYNAL

This short film produced by Eric Firestone Gallery about artist Jeanne Reynal (1903–1983) can be found on VIMEO through the QR code below. It features interviews with Maro Gorky and Matthew Spender, Dakin Hart, Matt Mullican, Berit Potter, and Kenneth Sills.

Directed by John Bergdahl and Adam Hurwitz.

Running time: approx. 13 min.

Eric Firestone