ESSAYS

FLYING HIGH: THE ACHIEVEMENT OF JOE OVERSTREET

by Barbara Rose

JOE OVERSTREET: A MODERNIST LINEAGE by

LeRonn P. Brooks Ph.D

Joe sitting next to his Malcolm painting, c. 1960

FLYING HIGH: THE ACHIEVEMENT OF JOE OVERSTREET by Barbara Rose

There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.

-Mark Rothko, Joint statement with Adolph Gottlieb, 1943

At age 84, veteran painter Joe Overstreet would perhaps not strike one as a revolutionary figure. Yet, if we follow the evolution of his art over the course of time, the artist reveals himself not only as a quiet, thoughtful, non-violent revolutionary, but also as a committed fighter for his beliefs and convictions.

Born in the rural Southern hamlet of Conehatta, Mississippi, Overstreet, like his contemporaries Sam Gilliam and Elvis Presley — both coincidentally born in nearby Tupelo, Mississippi — grew up in a rigidly segregated racist society. In 1946, the Overstreet family moved to the Bay Area, settling in the college town of Berkeley, California. Because his father was a stone mason, young Joe was exposed early to architectural construction, which is reflected in his tightly constructed paintings of the 1960s. He had not yet decided to pursue art as a career when he attended Oakland Technical High School, so he joined the Merchant Marines. He quit in 1953 to become an art student at the California School of Fine Arts, pursuing an art career the next year at the California School of Arts and Crafts.

Overstreet soon became a central fixture in the Beat Generation scene of the North Beach section of San Francisco, with its cofee houses, jazz clubs, and galleries. He was a lively and curious young man; in addition to art, his many interests included poetry, religion, literature, and playwriting. Eager to spread the message of a new art that disdained academic convention, he published a journal titled Beatitudes Magazine from his studio.

Part of the progressive Bay Area art scene that included artists like Nathan Oliveira and Richard Diebenkorn, Overstreet had a studio on Grant Street near that of Sargent Johnson. Johnson advocated that African-American artists look to their ancestral legacy for aesthetic sources and inspiration. This message resonated with the young Overstreet searching for an authentic identity.

From 1955 to 1957, Overstreet, like so many gifted California artists including Craig Kaufman, worked as an animator for Walt Disney Studios in Los Angeles. In 1958, he moved to New York City with his friend, Beat poet Bob Kaufman. Like Warhol, Johns, and Rauschenberg, he designed displays for store windows to earn a living. Quickly becoming a part of the New York art scene, Overstreet met many of the Abstract Expressionist painters like Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Larry Rivers, with whom he shared a passion for jazz. “I got more out of the Cedar Street Bar than anywhere,” he remarked

of his move to New York, where the galleries and museums showed the best of the contemporary avant-garde. But it was an attitude rather than a style that influenced him. “Looking at Hofmann reminded me of how I saw things naturally,” he commented, “And looking at Pollock reminded me of how I could do things naturally.” De Kooning was among the first to recognize his talent and commitment and gave Overstreet some of his works to sell as he settled in to the New York art scene.

In 1962, Overstreet moved downtown to Manhattan’s Lower East Side. During that period, the Lower East Side was a hotbed of creativity and experimentation in all the arts. Overstreet became familiar with the mostly white avant-garde art scene although he kept his connections to the AfricanAmerican community in terms of theater, literature and jazz, the lingua franca of the downtown art world. The only authentically American art form, jazz in its many forms was invented by the descendants of African slaves brought to the United States in chains, gradually becoming the basis for indigenous American music not based on European sources. It remains to this day the principle root of American popular music.

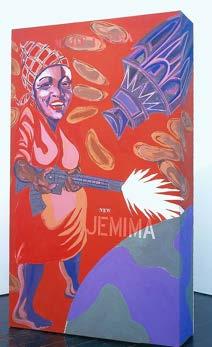

In 1964, he made a large painting titled “The New Jemima.” Larry Rivers saw it, and said that if Overstreet enlarged it, he would include it in the “Some American History” exhibition at Rice University. This exhibition of Rivers’ work, along with others he selected, was commissioned by the Menil Foundation to animate aspects of race within American history and support the desegregation of the university, begun in the 1960s. Overstreet made a three-dimensional wooden armature so that the painting would resemble a pancake box in this revised version of the work. He felt the new world of space travel deserved a New Jemima, who wields a machine gun shooting pancakes rather than flipping them.

His invention of a new image for women recalls the “Future Eve” invented by a fictionalized Thomas Edison in Villiers de L’Isle Adam’s novel; this androidwoman also does not take orders and threatens

Joe Overstreet, The New Jemima, 1964/1970

the hegemony of the ruling patriarchy. Clearly Overstreet was searching for a way to give painting content and meaning at a time when only formalism was considered significant art by the academy and museums. He found an answer in his signal 1965 painting Strange Fruit, which includes the image of a rope diagonally across the canvas.

The title “Strange Fruit” is taken from Billie Holiday’s 1940 recording of Lewis Allan’s song about the lynchings of black men in the South. The daring image of dangling legs may also refer to the three civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner – killed in 1964 in Philadelphia, Mississippi, not far from Overstreet’s home town. The presence of the image of rope was intentionally political. At the same time, as Ann Gibson suggests, this painted cord unifies the composition by crossing diagonally from edge to edge, recalling a compositional device that art theorist Jay Hambidge suggested to unify paintings. 1 Hambidge’s system of diagramming paintings was widely taught and influenced both Thomas Hart Benton and his student Jackson Pollock.

Overstreet has said that The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry was a major influence on him as well. He was specifically interested in Hambidge’s discussion of the Harpedonaptae, the rope-stretchers of Egypt who discovered the principles of dynamic symmetry and used them to lay out temple plans. He recalls that his father was interested in the Egyptian rope stretchers, and how masons used rope lines to determine the perspective, pitch and level of the earth.

During this period, Overstreet worked with playwright and poet Amiri Baraka, who preached the gospel of the Black Power movement, as set designer and Art Director of Harlem’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre and School in Harlem. Overstreet had met Ishmael Reed, the poet, writer, and political activist, who was formulating his Hoodoo (Haitian voodoo) aesthetic as a literary method in 1963. Suddenly, previously discredited or described as “primitive,” tribal art became a source for fresh new ways to invigorate modernism, whose roots, ironically, were often stylized tribal forms.

The avant-garde dialogue about creating a radical new art and his own experiences as a widely traveled African American provided the dual sources of Overstreet’s work: high art modernist painting on the one hand, and the intense, dramatic, emotional content of the growing Civil Rights Movement. His refusal to abandon either elegant, logical abstract form or painful social content gives his work both authenticity and impact and is a hallmark of his unique style.

Overstreet was among the first to make shaped canvases in the late 1960s, but again the inspiration was dual. On the one hand, popular abstractionist Frank Stella was inspiring a generation of American artists like Neil Williams and Larry Zox to quit the rectangle for more radical formats. The history of the shaped canvas is complex and also involves a new interest in Native American rugs, hangings and designs. Artist Tony Berlant collected these artifacts and sold them to other artists, inspiring some

Joe Overstreet, Strange Fruit , 1964

like Ed Moses and Alan Shields to remove the canvas from the stretcher and let the cloth hang freely on the wall. The bold and striking jagged zigzag geometry of these rugs and hangings influenced many artists, especially Williams, who was in fact a full blood Navajo.

It is within this doubly revolutionary context—of a need to reconfigure formalism and the fundamental tenets of painting together with a rising consciousness of African art and its connection to African-American identity—that Overstreet matured. Class consciousness, formerly a forbidden subject, was coming to a head in the unsettled atmosphere of the Sixties in both the United States and Europe. This political crisis corresponded with a crisis in abstraction that called for new solutions to the problems of painting, redefining its relationship to its bourgeois architectural setting. Overstreet responded to both crises with his own individual solutions.

Part of his solution was to change media and technique as well as format. Like many American artists fascinated with new media, he stopped working with oil in 1964 and began painting in acrylic, a new water-based plastic pigment which dries faster and is cheaper than oil. The problem was that Western art was rectangular in format to fit the frame. To change that rigid structure was in itself a radical gesture, meant to challenge the past history of the medium as an ornament for first royal and then bourgeois interiors, and ultimately the white cube of International Style architecture.

Overstreet’s shaped canvases referenced the volatile political climate of the Vietnam war with titles such as “Agent Orange.” He began to look to the world at large instead of only Europe as a source of inspiration and began studying not just the forms, but also the iconography of Native Americans and East Indians, of Oceania and Africa. Using wooden dowels shaped with a jigsaw and hand tools to make intricately cut out stretchers that were eccentric and not rectangular, he painted stylized jagged flat figures.

His unstretched “Flight Pattern” paintings of 1970 assumed the condensed flat imagery of the circular mandala, considered sacred in many religions. Overstreet was interested in Tantric yoga, as well as in the Navajo rituals of sand painting that inspired Pollock. He wished to combine features taken from a variety of cultures, defining art as a “coming together of expression, cultures crossing.” There is no aggressive bitterness in Overstreet’s worldview; on the contrary, he wishes to use his art to bring people together.

The mandala was the perfect form for his objectives. We owe the re-introduction of mandalas into modern Western thought to Carl Jung, the Swiss analytical psychologist. Buddhism was of interest generally in New York beginning in the early Fifties, but the publication of a full color book on Tantric mandalas in the early Sixties changed the direction from Zen to Tantric Buddhism. Among its adherents were Kenneth Noland, Richard Serra and Phillip Glass.

For Jung, the urge to make mandalas emerges during moments of intense personal growth. Apparently this was their function in Overstreet’s life as well. Around 1970 he was able to synthesize his various preoccupations, and use abstraction to communicate empathy and symbolic meaning, in addition to a purely aesthetic statement. Mandalas are commonly used by Tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation. The mandala is regarded as a place separated and protected from the ever-changing and impure outer world. By contemplating its hypnotic form, one finds nirvana and peace. The form has parallels in Eastern and Mesoamerican cultures, as well as Mayan calendars. Overstreet painted his geometric mandalas, which were not centralized, but instead stretched like hides and attached to the wall with grommets, in brilliant, often tropical colors.

As we have observed, by 1970, Overstreet was done with the idea that paintings had to be flat rectangles on the wall. The fact that he was the set designer for the Amiri Baraka’s Black Repertory Theater may well have played a role in giving up the conventional rectangular format for painting, which, in its frontality, was like the proscenium stage. Baraka’s Slave Ship, a radical in-the-round presentation first produced in Harlem in 1967, rejected the separation of audience and actors imposed by the proscenium stage and placed the actors directly in the space of the audience. In the same way that the audience filled the space, Overstreet allowed his expanding constructions to come of the wall to be tethered to the ceiling and floor, as if floating freely in space as opposed to caged in a frame.

One of the innovative elements of Baraka’s play is the encouragement of audience participation. During the final sequence, actors step down from the stage and invite audience members to participate in a celebratory dance. As Baraka had animated the entire space of the theater, Overstreet began to take over the entire gallery space filling it with swooping canvases attached to the ceiling and floor in free flight.

It was a revolutionary period in both art and politics and understandably art reflected that atmosphere. Overstreet began to make paintings that were tentlike at first for a practical reason:

Joe Overstreet, Institute for the Arts, Rice University, 1972

he could roll them up to transport them from place to place. Then he began to enjoy the idea of painting as a nomadic art that could assume diferent configurations. Suddenly nothing, not even the stable unchanging rigid rectangle, was sacred. The installation of the “Flight Pattern” series, with its freedom from past restraints, may stand as a powerful metaphor for the liberation and freedom that minorities and women were fighting for in the revolutionary atmosphere of the late Sixties and early Seventies. The canvases of the “Flight Pattern” series, which float in space, free of the conventional rigid rectangular canvas attached to the fixed flat wall may be interpreted as a metaphor for liberation in general. The point is that though they are abstract, they do not lack expressive content, thus answering Rothko’s demand.

Earlier, Rauschenberg had used cardboard to make painting constructions that came of the wall into the room. However, filling the entire space projected that innovation still further, invading the viewer’s space with more intimate confrontations. That the paintings had variable and not fixed forms related them not to previous installations but rather to the latest preoccupations of New York postminimalism, the Paris-based Support-Surface group and Italian Arte Povera in their investigation of unstable, mutable unfixed forms. The idea that the support was soft cloth and not rigidly attached to stretchers was of interest in general to the younger avant-garde such as Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg and Alan Shields; Overstreet was very much part of this dialogue.

Overstreet identified with the homeless nomads to be seen everywhere, saying he was interested in maintaining the most appealing feature of nomadic structures: “their tendency, like birds in flight, to take of, to be lifted up, rather than be held down by the ropes that suspended them.” Overstreet has noted that he felt like a nomad himself. It is important to note that the conditions of nomadism are those of poverty, and poverty was the glue that held the authentic art community of the Lower East Side together. The art community of that time was too marginal to be racist. The audience for art was other artists. They were all very poor, meaning they had more in common with each other than with the uptight bourgeois world.

In the early 1970s, Overstreet taught in California but he returned in 1973 to New York where he met his wife Corrine Jennings, who was born into a family of artists. Her mother was a Yale graduate and painter, and her personal art collection contains her parents work, as well as that of other AfricanAmerican artists. Her father, the artist Wilmer Jennings, studied with Hale Woodruf and Nancy Elizabeth Prophet at Atlanta University. Together with Samuel C. Floyd, the Overstreets established Kenkeleba House, a gallery with lofts for artist studios at 214 East Second Street, bringing attention to both under-recognized and emerging artists.

Years later, when asked if he saw any conflict between his belief in the universality of art and his socially-themed paintings of the 1960s, Overstreet responded, “...I think when you look at Catholic Christian art, that’s universal, isn’t it? When you look at Michelangelo, sixteenth-century art, is that not universal? Isn’t that social?...”2 Overstreet’s aim was to strive for universality by uniting features from many traditions.

Overstreet said, “My paintings don’t let the onlooker glance over them, but rather take them deeply into them and let them out – many times by diferent routes. These trips are taken sometimes subtly and sometimes suddenly. I want my paintings to have an eye-catching ‘melody’ to them –where the viewer can see patterns with changes in color, design and space. When the viewer is away from the paintings, they will get flashes of the paintings that linger in the mind like that of a tune or melody of a song that catches up on people’s ear and mind.”

In 1970, I wrote the first cover story in a major art magazine on black art, in which I illustrated Overstreet’s work along with that of Sam Gilliam, Mel Edwards, Al Loving, William T. Williams, John Dowell and Bob Thompson.3 I did not distinguish between abstraction and figuration because I did not think it was necessary for artists to illustrate the black experience for African Americans to make important art.

However, it is true that figurative artists like Romare Bearden were included, usually as tokens, in museum shows, while abstractionists like Norman Lewis, who participated in the landmark symposium organized in 1950 by his friend Ad Reinhardt and Robert Motherwell at Studio 35 in New York, went unnoticed until recently. Although it is not the case today, among African-American artists in the 1960s and 1970s, there was a decided division between figurative and abstract painters. Overstreet’s achievement was to give to abstraction powerful content based on his own emotions and complex experiences.

1 Ann Gibson, “Strange Fruit: Texture and Text in the Work of Joe Overstreet.” In Joe Overstreet: Works from 1957 to 1993, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, 1996. Exh. cat., 27.

2 Joe Overstreet, in “Joe Overstreet: Light in Darkness,” Interview by Graham Lock. In The Hearing Eye: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art. Eds. Graham Lock and David Murray (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.).

3 Barbara Rose, “Black Art in America,” Art in America, September-October 1970, cover, 54-67.

JOE OVERSTREET: A MODERNIST LINEAGE

by LeRonn P. Brooks Ph.D

Joe Overstreet was born in 1933, in Conehatta, Mississippi, a small town located near the heart of the state. In the Mississippi of his youth, segregation provided stark realities. Black people and white people could not be born in the same hospital or be buried in the same graveyard. They could not share the same classrooms or the same jail cell, and of course, public libraries and schools were as segregated as the art museums, galleries, art schools, literary forums, and journals that purported to show the best of American art and therein, the canon. In short, the field of American art and criticism was perpetuating the same lie of African-American invisibility, silence, and inferiority as the entirety of our democracy, as evidenced in the country’s legal and social realities. These circumstances necessitated the tradition of African-American art and that tradition’s equation of creative rights with civil rights. Overstreet is a living part of this tradition. So what, then, does it mean for a black man born into these circumstances, under the shadow of Jim Crow, to dream of creating fine art?

Overstreet was the inheritor of a political and aesthetic lineage long before the Black Power movement of the 1960s and his work with Amiri Baraka’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School and Kenkeleba House. During the 1920s and 1930s, African-American painters and sculptors established a New Negro modernism which set the terms for Overstreet’s generation that followed and matured during the late modernist and Abstract Expressionist era beginning in the mid-1950s. The post-World War I generation of artists—such as Overstreet’s friend, the painter Hale Woodruf, who founded the art department at the Atlanta University Center in 1931—created self-afirming imagery which conveyed the eforts of post-Emancipation African Americans to form and maintain independent communities while declaring their agency in American media, popular culture, and politics. Scholar W.E.B. Du Bois described this period as a crucial moment of collective self-examination, selfconsciousness, self-realization, and self-respect, in which a group of artists

Joe Overstreet and North Star, 1968

played an important part in defining the realities of an emergent community. New Negro political and cultural workers challenged demeaning caricatures of their race. These visual artists, writers, and academics demonstrated complex representations of African-American life and culture for a purpose. As historian John Hope Franklin recalls:

[New Negro leaders] consistently and bitterly resented the systematic eforts to misrepresent their role in history or to deny the black community membership in the human family, to say nothing, of first-class American citizenship.1

The arts were a route to mainstream acknowledgment but engagement with the black community preceded concerns for that acknowledgment. Against the backdrop of racist and demeaning imagery in popular culture and fine art, emergent race leaders, institution builders, and intellectuals like Du Bois and Booker T. Washington countered misrepresentations of the race by championing images of proper middle-class archetypes. Overstreet’s own The New Jemima (1964) is itself a militant ideological descendant of these initial eforts.

Overstreet’s interest in and use of symbolism from the black diaspora has deep roots. Traditional African art laid the foundation for modern art and African-American artists use of African motifs gave the socially oriented concepts within these traditional forms new tread by aligning the political eforts of New World artists of African heritage with their antecedents. It was a complex modernity which did not rely completely on the idea of formal innovation for its significance or more simply its right to be seen as experimental or ingenious. Overstreet, and his small cadre of younger African-American artists influenced by the New Negro racemen from the prior generation, saw their explorations in the diaspora as a matter of understanding who they were through the lens of cultural inheritances as civil rights protested for a more representative democracy, their artwork represents the cultural and aesthetic possibilities of what should be a more representative and truthful art historical canon.

After leaving Mississippi, Overstreet’s family relocated five times before arriving in northern California (Oakland and then Berkeley) in 1946. His personal journey was a ripple in a much larger sea of dramatic change between the wars as people of African descent migrated en masse around the world. Black people in the diaspora were forming revolutionary and anti-colonial platforms informed by cross-hacked nationalities that were often transferred into aesthetic forms. Their work opened spaces in which black culture disputed race and class-based expectations of identity—spaces where Santería could be mixed with Surrealism (such as with Wilfredo Lam), or, with Overstreet, where Native American and African symbols commingle. Overstreet’s bold abstract paintings of the late

1950s through the 1960s reflect this sense of brashness and self-authentication. Literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt comments that artists who embody a culture allow us, as viewers and readers, to enter the “cultural patterns” of these cultures and the ways they manifest identities:

We respond to a quality, even a willed or partially willed quality, in the figures themselves, who are, we assume by analogy to ourselves, engaged in their own acts of selection and shaping and who seem to drive themselves toward the most sensitive regions of their culture, to express and even, by design, to embody its dominant satisfaction and anxieties. 2

In the United States, there was a major movement toward urban centers in the Northeast, the Midwest, and the West Coast from Southern states. There was also a confluence of African peoples from Africa and the Caribbean to Europe and the U.S. On a smaller scale, such encounters would also occur for African-American artists who traveled abroad and would spark an intellectual and cultural resurgence as artists such as Hale Woodruf, who had studied in France, and Sargent Johnson, who had studied in Mexico, returned to the States to teach in black colleges or informally in studios. (Both Woodruf and Johnson would go on to befriend and mentor Overstreet.) Overstreet’s use of African-American and African symbolism in shaped paintings such as North Star (1968), Evolution (1970), and Untitled (1970), reflects both Woodruf and Sargent’s influence and the feeling of the migratory cultural practice of his elders as well as the late Modernist formal practices of peers such as Frank Stella, Adolph Gottlieb, and Al Loving. But it is also his ability to improvise and implement his empathic connection to multiple traditions that separates Overstreet from his peers.

During the first half of the twentieth century, artists such as Lam, Aaron Douglas, Edna Manley, and Lois Mailou Jones, created work that adjoined African, African-American, and Afro-Caribbean nationality, religion, history, and class into the modernist discourse. Such modern and revolutionary activity included breaking in part with histories of racist representation and Eurocentrism by aligning themselves with the influence and fluidity of black people in, and over, popular culture and modernist aesthetics. This reckoning set a precedent for Overstreet’s generation; it provided for a complex mesh of identities and forms of representation to their community and was at the same time concurrent with the modern world and modern painting. Avant-garde practice had been too long fixed to Western aesthetics. The interests and influences of artists of African descent reflected an ever expanding world in Western aesthetics was one influence amongst many. Overstreet, therefore, is part of a complex and diverse modernist tradition connected to the African diaspora and seeded with truths. This is an important aesthetic lineage--a history of late Modernity, social engagement, and cultural ties speaking to the urgency of this very moment.

Installation view: Joe Overstreet, Innovation of Flight: Paintings 1967 - 1972

1 John Hope Franklin, “The New Negro History,” The Journal of Negro History /42, no. 2 (April 1957), 93.

2 Stephen Greenblatt, Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare (Chicago: Chicago UP, 2005), 6-7.

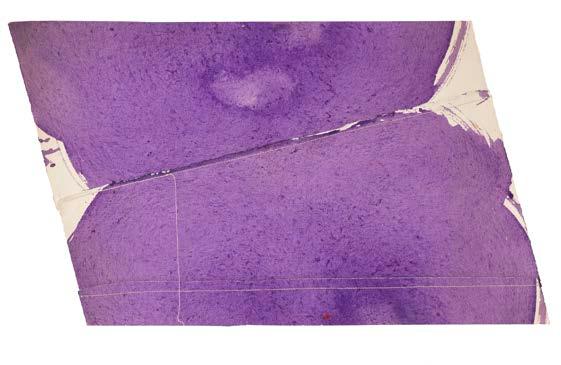

Purple Flight, 1971

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope

canvas: 66 x 101 x 25 3/4 inches

For Happiness, 1970

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 91 x 60 x 31 inches

Untitled, 1972

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 80 x 163 x 35 inches

Untitled, 1971

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 102 x 116 x 37 inches

St. Expedite II, 1971

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope

canvas: 61 x 111 x 22 inches

HooDoo Mandala, 1970

acrylic on canvas, metal grommets, and cotton rope

canvas:: 90 x 89 1/2 x 1/4 inches

Mandala, 1970

acrylic on canvas, metal grommets, and cotton rope canvas: 93 x 89 inches

Untitled, 1972

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 34 x 49 x 28 inches

Untitled, 1970

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 75 x 40 x 31 inches

Untitled, 1970

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 42 1/2 x 39 x 35 1/2 inches

Untitled, 1972

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 88 x 98 x 23 1/2 inches

Untitled, 1971

acrylic on constructed canvas, with metal grommets and cotton rope canvas: 72 x 72 x 16 inches

CHECKLIST

Untitled, 1970

acrylic on canvas, metal grommets, and cotton rope

canvas: 34 x 20 1/4 inches

North Star, 1968

acrylic on canvas construction

93 x 85 x 3 inches

Untitled, 1972

acrylic on canvas

92 1/2 x 83 1/2 inches

Untitled, 1972

acrylic on constructed and sewn paper

22 x 30 inches

Study for Boxes, 1970

acrylic and watercolor on Arches paper

22 x 30 inches

Study for Expedited Space, 1972

watercolor on Arches paper

22 1/2 x 30 inches

Study for Emerging Surface, 1972

acrylic and watercolor on Arches paper

22 x 30 inches

JOE OVERSTREET

b. 1933, Conehatta, Mississippi

EDUCATION

1951-52 Contra Costa College, San Pablo, CA

1953 California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco

1954 California College of Arts and Crafts, Berkeley, CA

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

1954 The District, Oakland, California

1955 Vesuvio’s, San Francisco, California

1956 Cousin Jimbo’s Bop City, San Francisco, California

1958 International Gallery, New York, New York

1961 Tea Gallery, Miss Smith’s Tea Room, San Francisco, California

1965 Spanierman Gallery, New York, New York

Hugo Gallery, New York, New York

1969 Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, New York

1970 Joe Overstreet: Stretch Paintings, Berkeley Art Center, Berkeley, California

1971 Joe Overstreet, Living Art Center, Dayton, Ohio

Joe Overstreet, Ankrum Gallery, Los Angeles, California

Flight Patterns, Dorsky Gallery, New York, New York

1972 Joe Overstreet, De Luxe Black Art Center, Houston, Texas Institute for the Arts, Rice University, Houston, Texas

1976 Kenkeleba House, New York, New York

1988 The Storyville Series, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

1990 The Storyville Series, Vaughan Cultural Center, St. Louis, Missouri

1991 Recent Paintings, Wilmer Jennings Gallery, New York, New York

1992 The Storyville Series, Montclair State College Art Gallery, Montclair, New Jersey

Joe Overstreet, G.R. N’amdi Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan, Columbia, Ohio

1993 Facing the Door of No Return, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

1996 (Re) Call and Response, Everson Museum, Syracuse, New York, New York

Joe Overstreet: Works from 1957 to 1993 , New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey

Watercolors, Aljira Contemporary Art Center, Newark, New Jersey

1999 Recent Paintings, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

2001 Silver Screens, Wilmer Jennings Gallery, New York, New York

2003 Meridian Fields, Wilmer Jennings Gallery, New York, New York

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2008 The Storyville Series, City Gallery East, Atlanta, Georgia

2012 Navigator Paintings, CW Post, Long Island University, Brooksville, New York

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1958 Artists Cooperative, San Francisco, California

1958 Dilexi Gallery, San Francisco, California Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

1959 City College of the City University of New York, New York, New York

1962 Tenth Street Aegis Gallery, New York, New York

1963 Allen Stone Gallery, New York, New York

Tenth Street Aegis Gallery, New York, New York

1964 Gordon Gallery, New York, New York

New York Public Library, Countee Cullen Branch, New York, New York

Allan Stone Gallery, New York, New York

1967 St. Mark’s Church on the Bowery, New York, New York

1968 Black Artists in America, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, New York

1969 University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Allen Stone Gallery, New York, New York

The Real Great Society, Tompkins Square Gallery, New York, New York

The Brooklyn Madau Museum, New York, New York

The New York Public Library Countee Cullen Branch, New York, New York

Pan American Building, New York, New York

Perls Gallery, New York, New York

Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, New York

1969-70 New Black Artists, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, Columbia University, New York, New York; Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts, Dorchester, Massachusetts; University Gallery, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida; Kirkland Gallery, Millikin University, Decatur, Illinois; Reading Public Museum and Art Gallery, Reading, Pennsylvania

1970 Afro American Artists New York and Boston, The Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, The Museum of Fine Art, Boston, Massachusetts

Dorsky Gallery, New York, New York

1971 William Zierler Gallery, New York, New York

Black Artists: Two Generations, Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey

O f The Stretcher, The Oakland Museum, Oakland, California

Ben Jones and Joe Overstreet, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, New York

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1971-72

Some American History, Rice University, Houston, Texas

1972 Black American Artists, University of Iowa, Illinois Bell Telephone

1973 California State University, Heyward, California

Berkeley Museum, Berkeley, California

1974 MIX: Third World Painting/Sculpture Exhibition, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

West Coast 74: Black Image, Crocker Art Gallery Association, E.B. Crocker Art Gallery (Crocker Art Museum), Sacramento, California

1977 Richard Allen Center, New York, New York

1979 New York Artists, 22 Wooster Gallery, New York, New York

Another Generation, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, New York

Black Artists/South, Huntsville Museum, Alabama, Oakland Museum, California

West Cost Invitational: The Black Image, Crockett Museum, Sacramento, California

New York Public Library, Countee Cullen Branch, New York, New York

1980 Aspects of the 1970s: Spiral, National Center of African American Art, Boston, Massachusetts

Boston Artists of Today’s Lower East Side, Islip Town Council, Islip, New York

Summer Show, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

1982 Artists: New York/Taiwan, The Hatch-Billips Collection, American Institute in Taiwan, Kaohsiung, National Taiwan University, Spring Gallery

1983 Jus’ Jass, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

1984 Since the Harlem Renaissance, Bucknell University, Lewisberg, Pennslyvania

Stereotypes, Balch Institute, Philadelphia, Pennslyvania

1985 Celebration VI, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, New York

Free Expressions, AC-BAW Gallery, Mt. Vernon, New York

The Gathering of the Avant Garde: The Lower East Side, 1948-1970, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

Art Works In City Spaces, The Tweed Courthouse, New York, New York

Images of Jazz, The Wilson Arts Center, Rochester, New York, New York

Henry Street Arts for Living Center, New York, New York

Af irmations of Life, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

1986 Contemporary Afro-American Artists, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Pennslyvania

Twentieth Century African American Artists, The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey

Tradition and Conflict: Images of a Turbulent Decade, 1963-1973, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, New York

1986 Harlem Transitions: The Afro-American Artist, The Bergen Museum of Art and Science, Paramus, New Jersey

A View From Harlem, Smithtown Arts Council, Smithtown, New York

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1986 13 Black Artists, Hudson River Guild, New York, New York

In Honor of Greatness, Essex County College, West Caldwell, New Jersey

1987 Made in the USA , University of California at Berkeley, California

Evergreen Gallery, Brooklyn, New York

Alitash Kebede Gallery, Los Angeles, California

1989-90 The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernsim, Washington Project for the Arts, Washington, DC; California Afro-American Museum, Los Angeles, California; Museum of Art, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; Blaefer Gallery, University of Houston, Houston, Texas; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, New York

1990 The Color of Jazz, The Rye Art Center, New York

1991 African American Art in the U.S., Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago, Chile

The Spirit Made Visible, John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, California

In The Tradition, Part I, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York

African American Invitational, St. Louis Artist’s Guild, St. Louis, Missouri

1992-93 A/CROSS CURRENTS: Synthesis in African American Abstract Painting, National Center for Art & IFAN Museum, Dakar Biennale, Dakar, Senegal; French Cultural Center, Libreville, Gabon; GRAFOLIE Festival, Abidjan, Côte D’Ivoire

1992-94 DREAM SINGERS, STORYTELLERS: An African American Presence, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey; Fukui Fine Arts Museum, Fukui-City, Japan; Tokushima Modern Art Museum, Tokushima-City, Japan; Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya, Japan

1995 The Fifties, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, New York

1996 Abstractions, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

1997 The Art of Jazz, Dell Pryor Galleries, Detroit, Michigan

1998 Space, Time & Object: Black Abstractionists, City University of New York, New York

1999 When the Spirit Moves: African American Art Inspired by Dance, National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce, Ohio

1999 African American Artists in the Collection of the New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey

1999 Slave Routes, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

2001 Artists of the 1950s, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, New York

African American Abstraction, City Gallery East, Atlanta, Georgia

The Act of Drawing, Tompkins College Center Gallery, Cedar Crest College, Allentown, Pennsylvania; Rush Arts Gallery, New York, New York

The Politics of Racism, Fire Patrol No. 5 Art, New York, New York

Public Voices/Private Visions: African American Artists @ 2000, Rockland Center for the Arts, West Nyack, New York

19th and 20th Century African American Artists, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, New York

Tenacious Beauty, Delaware College of Art and Design, Wilmington, Delaware

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2002 Math Art/Art Math, Selby Gallery, Sarasota, Florida

2003 Group Show 2003, Peg Alston Fine Arts, New York, New York

Abstraction: No Greater Love, Jack Tilton Gallery, New York, New York

2004 Something to Look Forward to, Philips Museum of Art, Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennslyvania

Rhythm of Structure: The Mathematical Aesthetic, Wilmer Jennings Gallery, New York, New York

2005 Back to Black, Art, Cinema and the Racial Imaginary, Whitechapel, London, United Kingdom

2006-07 High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967 - 1975 , Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greesnboro, North Carolina; American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, Washington, D.C.; National Academy Museum, New York, New York; Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, Mexico; Neue Galerie Graz, Graz, Austria; ZKM | Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, Germany

2007 a point in space is a place for an argument, David Zwirner Gallery, New York, New York Paintings from New York, 1967 – 1975, Galerie Kienzle & Gmeiner, Berlin, Germany; Galerie Thomas Flor, Dusseldorf, Germany

2008 Harlem of the West Revisted, Jazz Heritage Center, San Francisco, California

2009 Harlem of the West: Jazz, Bebop and Beatnik, California African American Museum, Los Angeles, California

2010 From the Permanent Collection, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, New York

Rehistoricizing Abstract Expressionism in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1950s-1960s, Luggage Store Gallery and San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, California

2011-12 Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960 – 1980, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, California

2011 Americans At Play, Sullivan Goss Gallery, Santa Barbara, California

From Page’s Edge: Water in Literature and Art, Payne Gallery, Moravian College, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, Vergennes, Vermont; Albany Institute of Art, New York, New York

African American Contributions to a Shared Vision, Prints from the Cochran Collection, Lamar Dodd Art Center of La Grange College, La Grange, Georgia

African American Abstract Masters, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, New York; AS Art Foundation, Jim Thorpe, Pennslyvania; Opalka Gallery, Sage Colleges, Albany, New York

2012 Visual Rhythms, California African American Museum, Los Angeles, California

Reflections of Monk: Images of Music and Moods, Wilmer Jennings Gallery, New York, New York

2012 The Countryside in Southern Literature and Art, AS Foundation, Pennsylvania

2013 American Renaissance Art, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, New York

2013-14 Large and Small, Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, New York

2014 Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, The Brooklyn Museum, New York, New York

2015 The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom

I Got Rhythm: Kunst und Jazz Seit 1920, Stifung Kunstmuseum, Stuttgart, Germany

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2015 Art of the 5, I’ll Take Manhattan, Intra-church Center Gallery, New York, New York

Master and Pupils, Rye Art Center, New York, New York

2016 Abstract Masters of the 1950s, (Where were the Mistresses?), Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York, New York

The Color Line, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France

2017-19 Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

2018 Picturing Mississippi, Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson, Mississippi

Way Bay, University of California Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archives, Berkeley, California

AWARDS

2016 Joan Mitchell Foundation Creating a Living Legacy Award (CALL)

2018 Governors Award for Excellence in Visual Art from the Mississippi Arts Commission

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York

Everson Museum, Syracuse, New York

Newark Museum of Art, Newark, New Jersey

Oakland Museum, Oakland, California

University of California Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archives, Berkeley, California

Crockett Museum, Sacramento, California

New Jersey State Museum at Trenton, New Jersey

The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas

Cochran Collection of Works on Paper, Stone Mountain, Georgia

Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson, Mississippi

COMMISSIONS

1968 The New Jemima, The Menil Foundation, Houston, Texas

1982-7 Environmental installations in tunnels A & C, San Francisco International Airport, San Francisco, California

Installation view: Joe Overstreet, Innovation of Flight: Paintings 1967 - 1972