November 1, 2024 – January 10, 2025

Interviewed by Maddy Henkin in New York City, January 28, 2025

Edited by Jennifer Samet

Maddy Henkin:So, Walter, what made you want to become an artist?

Walter C Jackson: I’m not really sure when I decided I wanted to become an artist, but I grew up creating things, drawing, and painting. I had an uncle who was a very creative person. I followed in his footsteps, in a sense, because I wanted to do the things that he was doing.

MH: And what was your frst memory with art? Was there a light bulb moment?

WCJ: One of the important steps along the line was winning a state high school art competition. It was s onsore y ac son tate ollege an on frst prize. To an extent, that was a light bulb moment, because it was validating. This was in 1959, at a time when Mississippi was segregated. Jackson State was, and still is, an HBCU school. So, we’re talking about competition between Black high school students throughout the state. It was a competition that a ene e ery year an i yo on frst ri e yo were awarded college tuition. If you were majoring in art, that was your entry. And I ended up going to Jackson State.

MH: Did you have any hesitations about pursuing this path?

WCJ: Oh, absolutely not.

MH: When did the transition happen between painting and sculpture?

WCJ: I started moving into sculpture in graduate school at the University of Tennessee. I felt my paintings didn’t have the structure I was looking for, and I couldn’t quite do the things I wanted to do with paint. I felt I needed something more tactile. After t at frst class t ere as no going ac . ne it as what I wanted to do. In the 1970s, there was a lot of experimental work that involved light, movement, and sound. I gravitated toward that because my initial work in welded steel was very gestural. I thought of them as writing in space. They had movement, and a quality of evolution that comes from the twisting and turning of shapes.

It was an easy transition to move into kinetic and light work. I was always interested in science. One of the things that intrigued me was how the sensory system worked–the movement of neurons in the dendritic system of the body. I imagined this visually, and that led to pieces involving ping pong balls, air pressure, voice control, and touch switches. I did a number of these works in the early to mid 1970s. Gradually my interests evolved from science to philosophy, and how they interact, along with religion. By the late 1970s and 1980s, this became a focus, and I felt less of a need to work with movement and light.

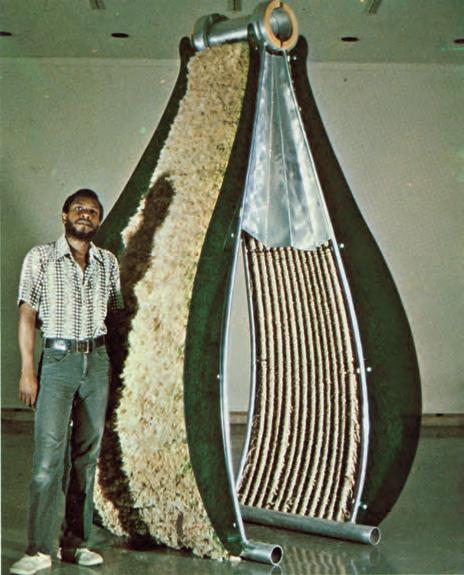

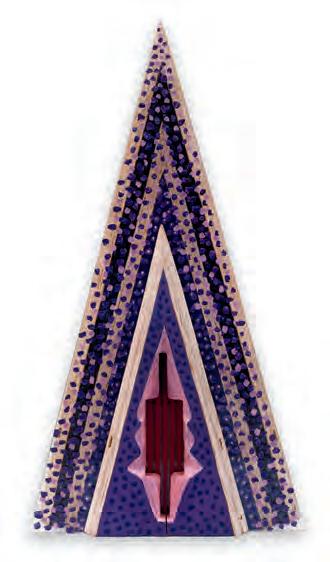

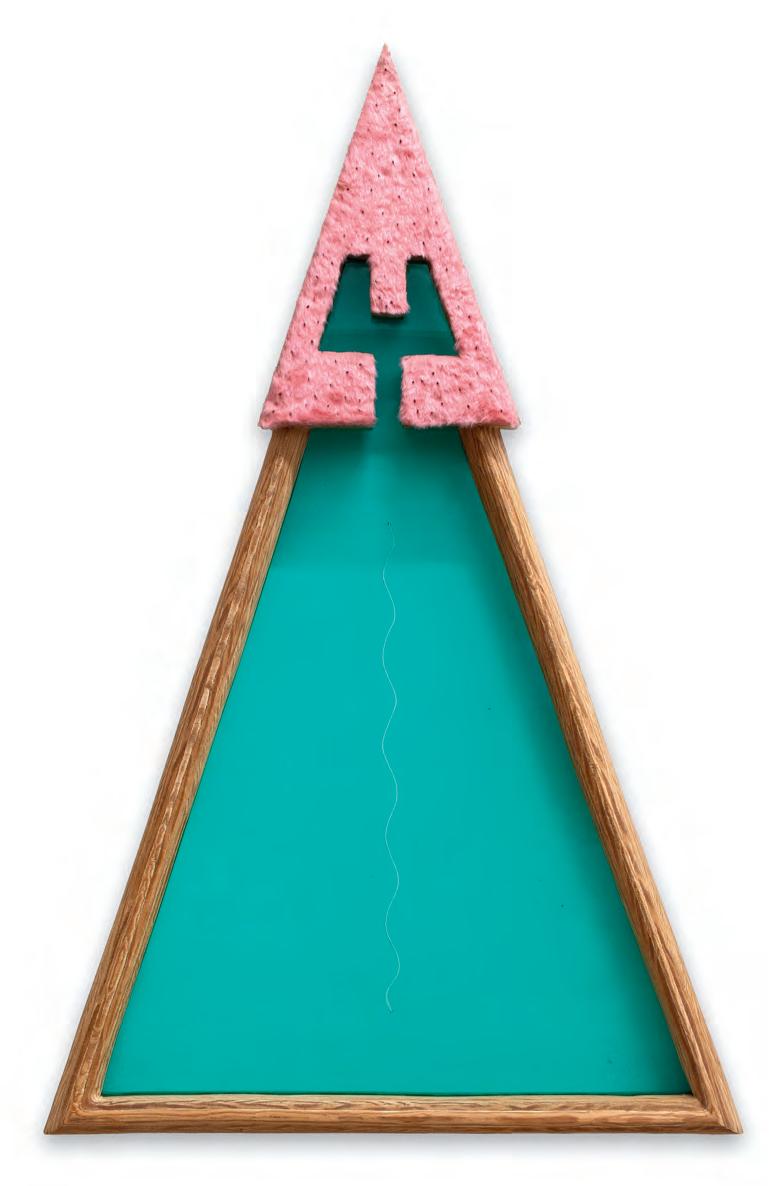

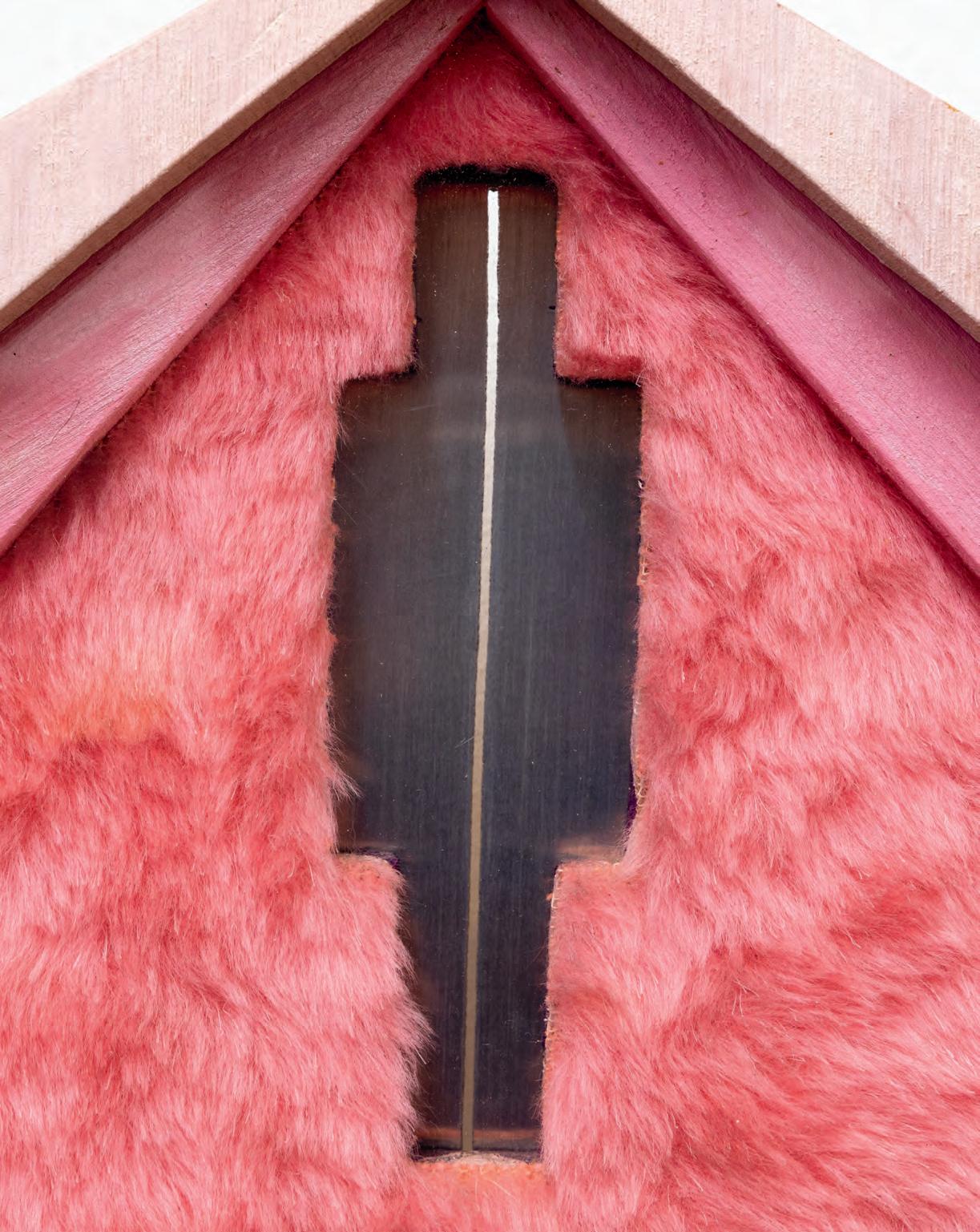

MH: Our exhibition included two works from 1976, both titled Spirit Keeper. Could you talk about the evolution that brought you to these works?

WCJ: I was thinking about folklore, religion, and philosophy. I had been doing a lot of reading on Eastern

religion, and I was intrigued by the notion of a unity of opposites. The work explores this. My materials included metal, wood, and plastics. I saw that as a culmination of time: past, present, future. I was thinking about communal memory, more than anything else. I was considering images that related to growing up in the South, and the stories that I heard, especially from my uncle. I was thinking about their spiritual nature. It was a natural evolution: I had been reading about various cultures, and now I was thinking about those in relation to the culture of my own childhood.

MH: Throughout your career, you’ve used a lot of di erent materia s and o ten materia s that either are industria or ha e an industria a earan e hy are they a ea in to you?

WCJ: For me, industrial material is very human, because it speaks to a certain kind of need. The question became how to make a statement about that need. I was considering the combination of nature, my childhood stories, and current technology. So I began to incorporate recognizable industrial objects, like automobile exhaust pipes. The exhaust pipe represents an interesting dichotomy. It is part of something that moves you from one place to another, including on an industrial scale. I have always found big trucks very beautiful. However, that beauty can be destructive. The exhaust from a large truck can be deadly. Destructive things can have beauty. How do you combine it all, and put it together to create a conversation?

At that particular time, I was also using plastic. For me, plastic was about the future, and not in the sense of that line from the movie The Graduate. I was thinking about how plastic was becoming a very permanent thing in the environment. It is everywhere and people use it for all kinds of things, some positive, some negative. The materials of wood, metal, and lastic eac s ea to i erent times an i erent developments. The combination spoke to ideas of continuity and time.

MH: n that note has the way that you iew this wor rom the s throu h the s han ed or you o er time?

WCJ: For the most part, I still see it in the same way. Of course you always think, “Maybe I would have done t is a little i erently t in general en loo ac at it, I’m quite happy with the results.

My materials included metal, wood, and plastics. I saw that as a culmination of time: past, present, future.

I think about one of my favorite sculptures, titled Goddess. The idea for it came very easily. I sat down, did a couple of sketches, and—boom—it was there. i n t a e to fg t it it. ome o my sc l t res s ent time fg ting it c anging a ing an ta ing away. But Goddess just happened, almost automatically e ce t or t e ery la or intensi e f er element. The intensity of that drove me crazy. But otherwise, t e act al constr ction as almost e ortless. lo e it for that reason. It had the impact, the immediacy, that I like my work to have. At the same time, there should be enough to hold you for a while.

MH: Would you talk a bit about the development of your Gothic series? Did the other portal works in that series also have this sense of an immediacy, or a di erent ee in ?

WCJ: They were scaled down and handled more as totems coming out of a Western religious sensibility, whereas Goddess was more related to African art. Dogon cosmology was important to me.

MH: ha e a re ated uestion whi h is a out o on and the relationship to your identity. In the 1980s, you mostly exhibited at Black cultural spaces. You had a residency at the Studio Museum in ar em you showed at the hom ur enter or Research in Black Culture, the African American Art Museum, Hempstead, NY, Kenkeleba House,

and Just Above Midtown. Were you thinking that your Black identity was particularly essential in your work of that period? Looking back, do you consider that your legacy was circumscribed within Black artistic traditions?

WCJ: I don’t think of my work as circumscribed within a s ecifc lac artistic tra ition. o o e er t in of it as being circumscribed within the communal Black experience. In the 1970s I didn’t feel that there was one particular aesthetic direction of the Black Arts Movement. However, it is true that the places I was showing were Black institutions. This came out of my residency at the Studio Museum. That residency was very important to me. I had moved to New York in 1980 and I got that residency in 1982.

The residency gave me the opportunity to meet an interact it many lac artists o i erent generations, that I didn’t know previously. Some were younger than me, and some were older. Some I had heard about before and others I didn’t even know. It was important in broadening my knowledge of what was happening in the city, and as a result, it led to opportunities with other venues. These interactions made my transition to New York easier and my experience more expansive.

MADDY HENKIN is Associate Director of Eric Firestone Gallery. She co-curated the exhibition Spirit Keepers with Jennifer Samet, the gallery’s Senior Director.

Interviewed by Portia Cobb in Oakland, CA, September 19, 1986

Excerpted from Connecting Conversation: Interviews with 28 Bay Area Artists, 1988

Marie-Johnson-Calloway lives on top of a hill in East Oakland. Though the day of my visit was overcast, her home had a feeling of vast openness, serenity and sunlight. Johnson-Calloway’s presence is warm and responsive. We discussed our mutual admiration for the work of another woman artist, Faith inggol o nson allo ay is s ecifcally interested in Ringgold’s mother’s participation in the art of her daughter. We began with a tour of JohnsonCalloway’s home, looking at examples of her work and the work of her family members. There are four generations of artists in her family: her mother, Marie Edwards, who is in her nineties, Johnson-Calloway herself, and Johnson-Calloway’s daughter and grand-daughter. I was intrigued with her large-scale assem lages. ac a er ect an ignife re resentation of people in community–laborers, elders and school children walking hand in hand with care givers. There were spirit houses and jewel boxes that held exquisite interiors of “found” objects. She said her family lovingly dubbed her “Madame Houdini” because she was always collecting junk from thrift stores and other sources and transforming them into her art.

Portia Cobb: You mentioned that you are from a timore and that your wor re e ts some o the s enes o a timore s enes rom your hi dhood

arie ohnson a oway I was born in Baltimore and during that time the Black community was totally separate from the white community, except for maybe the corner grocery store, so that we all went to allBlack schools. All of our teachers were Black. We lived in a Black world which was not only Black, but poor and separate. And yet, I feel that when I am doing my most meaning l or it re ects my e erience an that kind of community where I sense the connection with the people who are like me. I found out after I left Baltimore that this experience was still an integral part of me. It still keeps coming back into my work.

PC: n you arti i ated in the amous e ma A a ama ar h with r artin uther in r ow did that ome a out and how did it han e your art?

MC: Concurrent with that time, I had gotten interested in civic activities in San Jose. I realized that even though California had many more opportunities, there was, and still is, a great deal of racism. We discovered

You work with the kind of material that you have at hand, and what I have at hand is my own life.

it in San Jose in the schools, in the curriculum and in the housing. I became the President of the NAACP there. That was just at the time that the Selma March came about, and this all contributed to my incentive to go down there. I felt that I had to be down there. e frst nig t got t ere t ey ere oing a emonstration—walking down by the mayor’s house. He had written into an ordinance that day a law that said that there could be no parading down his street. When we got down to the end of the street, we were all arrested, put into a school bus and put in jail overnight. This was my introduction to Selma. I had just gotten there! That experience made me decide to do a turnaround in my art. It was interesting because I was working on my master’s at the time at San Jose State in painting and I had been a little ambivalent about using Black subject matters in my work because everyone would say, “Oh that’s too personal, you’re not being universal.” I decided that what I had experienced in Selma was as universal as anything. Once I had that clear in my head, I knew just what I had to do. I focused my whole master’s show on portraits and assemblages about Black people. As soon as the faculty knew what I had to do, their attitudes changed, and they helped me and encouraged me to do the best I really could. This was a very momentous period in my life.

PC: Had you experienced any opposition to your work as an artist prior to this?

MC: I had lots of it prior to that. Any time you would put the least bit of anything that said something about your people, then it became political. As soon as the fg res in yo r iece ecame lac t en t ey sai “You’re being too personal.” I don’t hear that anymore. There were no Black faculty people then. There was no one, to whom you could relate, who was experiencing what you were experiencing as a Black artist.

Announcement for Marie Johnson-Calloway’s solo exhibition at Brockman Gallery, 1971. Brockman Gallery Archive, Los Angeles Public Library Special Collections.

PC: As a Black woman artist, you had to have a lot o oura e to ma e that frst ste

MC: Yes. I had to get my own security together. I think going down to Selma really helped me to do that. I think it’s a continuous battle to try and convince the art world that what you’re doing is valid, not just because it’s Black, but because it’s about the same things that apply to all people—dignity, motherhood, faith, hope, work, courage, birth and death. You work with the kind of material that you have at hand, and what I have at hand is my own life.

PC: You mentioned that there are four generations o artists in your ami y

MC: Yes, four generations that have evolved. I think that I had not known of any other artist before I became interested in art. But since that time my daughter decided that she would be an artist and my granddaughter is also an artist. At eighty years old, my mother became interested in art when I started taking her to museums. She had never been to one before. When she saw the “Early California Junk” art show, she said “Aw, I can do that.” And so she started doing it. My son occasionally does ceramics, and, more recently, video and computer graphics.

PC: I see similarities between your work and your mother’s just as I see with Faith Ringgold and her mother. Her mother was also a seamstress.

MC: We grew up with the sewing machine and we learned to make all our clothes. My daughter grew up next to my mother too. She’s had a very strong in ence on my li e not only in terms o t e se ing t some real frm al es a o t ac ie ing and overcoming.

PC: When did you decide to become an artist?

MC: I don’t know. I taught elementary school for several years and then I came out on maternity leave with my second child. During that period, you had to stay out until your child was two years old. My former husband, a physician, had a patient who came by the house one time and saw me doing some sketching and said, “You should be an artist.” I had not really thought about it before. But he and I started talking about it. He was doing some kind of art. We would compare notes and he got me interested. At that time, i n t a e my college egree. a fnis e o in eac ers ollege a t ree year sc ool an at t at

time they didn’t give a degree. Most of us had to go back to school and get that fourth year of college. I chose Morgan College. What is interesting is, at that time, schools were still so segregated that we Blacks couldn’t go to the University of Maryland. We could get money to go to any school we wanted to as long as we didn’t go there. About four years ago when Forever Free, the traveling Black women artists’ show, went to the University of Maryland, they invited me to come back and be on a panel. I couldn’t resist saying to them that when I lived in Baltimore I couldn’t even walk on that campus. It was really an experience to be brought back as a panelist on that program.

PC: What was your experience like in college as a Black woman artist?

MC: Morgan was a Black college. It starts with my experiences before I ever got into college—growing up in Baltimore and being a victim of the most serious kinds of discrimination, not only in schools and housing, but in stores. If I wanted to try on a coat, to try it on we’d have to go to New York or Philadelphia. The humiliation of that is something I believe is embedded in all of us and yet what amazes me is that I am not bitter. I am bitter about the idea of discrimination and prejudice but I refuse to let it consume me to the point where I can’t be creative. No matter how abstract or into nature my work sometimes goes, it’s always going to come back to that Black consciousness.

PC: n your home the wor dis ayed re e ts a variety of media—watercolor, acrylics, the assemblages and collages.

MC: I am a many-faceted person. I think I come from all kinds of backgrounds and mixtures. I’ve had my foot in the white world and Black world, always balancing the two. Many Black people have had to diversify their lives in order to adapt to life in the United

States. So it’s only natural that there would be a lot of diversity in my work. I’ve lived in the ghetto and the slums of Baltimore and yet here I live up on this beautiful hill in Oakland. There’s a contradiction right there. So when I go down on East 14th and MacArthur Boulevard in Oakland, I’m back on Pennsylvania Avenue in Baltimore (laughs).

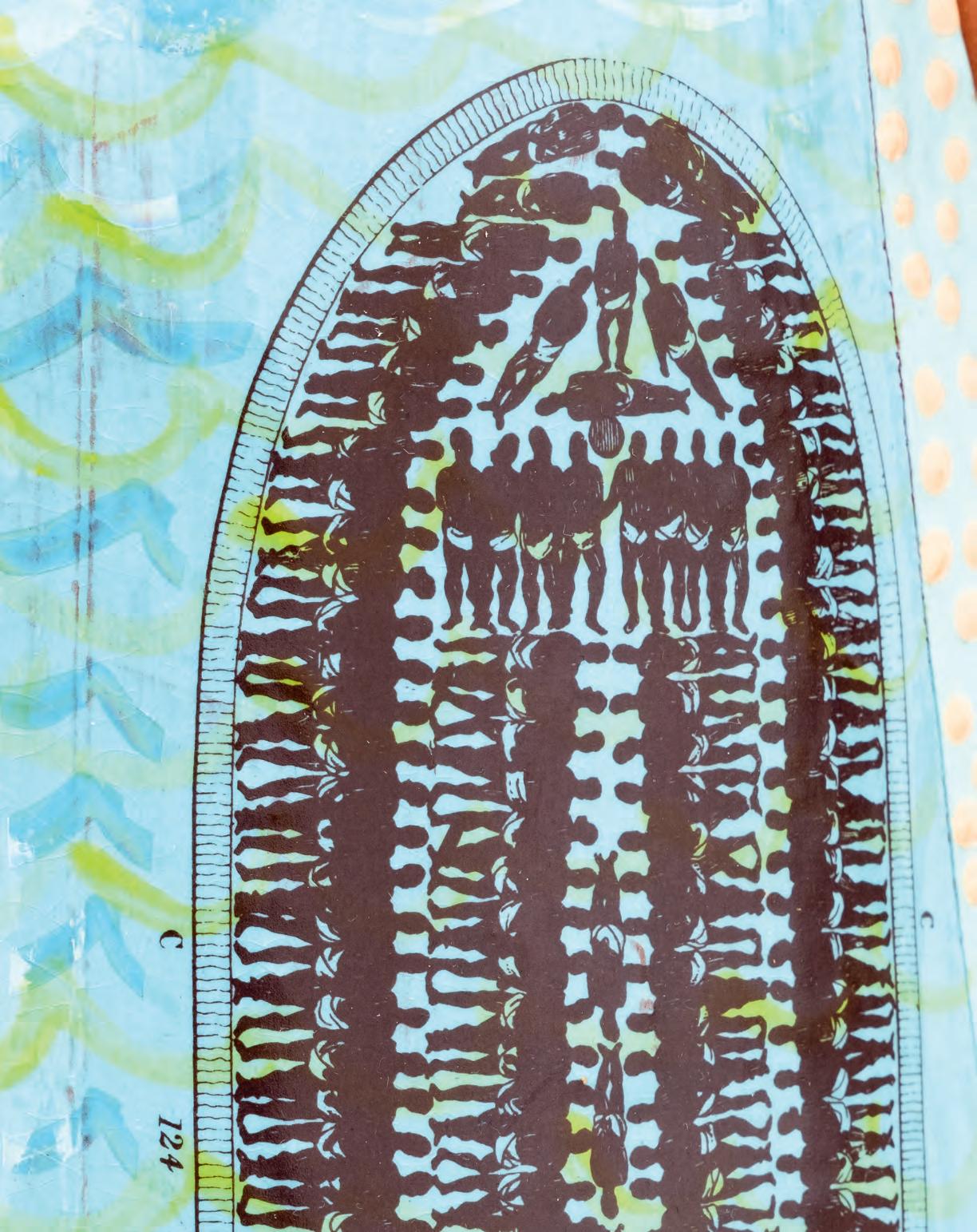

PC: Let’s discuss the Hope Street assemblage.

MC: Well, Hope Street started with one piece. That’s the old man in the window with the canary in the bird cage. The day I went to this old building-materials lace to fn t at in o t e ol man o as walking me around couldn’t understand why I wanted one that was so beat up. I explained that I wanted it to look old and used, and while we were talking, I looked down on the ground and there was this street sign that said “Hope Street.” He gave it to me and for several shows I showed that window with just the sign. Last summer I was invited to be a participant in a f e artists e i it at t e se m o rican merican Art in Los Angeles which was put together by Betye Saar. She was the guest curator. The whole theme of the show was s aces so eac o t e f e artists was asked to create a space and I thought, “I’ve got all these people here, why don’t I put them into the kind of space they should be in?” That’s when I got the idea of doing this installation of a street scene in which I have painted tableau-like back settings for the people. So then the title of the whole piece became Hope Street. What I was trying to show is how people, who are surrounded by hopelessness and who have had to live in very depressing and oppressive kinds of environments, have been able to maintain their hope and their dignity and to go on living. That’s what Hope Street is all about.

Interviewed by Maddy Henkin in New York City, December 19, 2024 as a public program in conjunction with the exhibition at Eric Firestone Gallery

Edited by Jennifer Samet

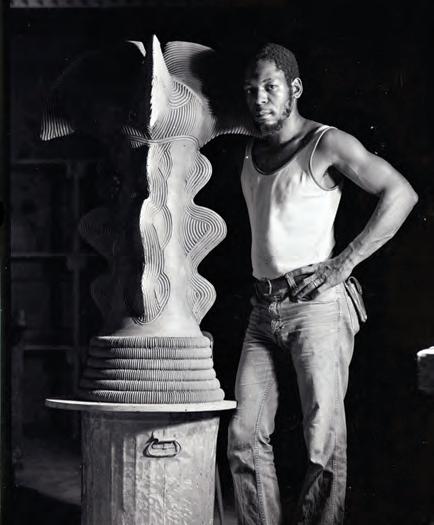

Maddy Henkin: David, how did you begin making art?

David MacDonald: Well, I’m the third oldest in a family of nine children. I remember when we lived in the house with our grandparents, there was a cabinet shop down the street. We would rummage through their dumpster, getting pieces of wood from which we could make guns. That’s when I discovered that I enjoyed making things.

I grew up in public housing. I remember that my mother would go grocery shopping every Friday in the late afternoon. I was the only one who wanted to go with her. When you’re shopping for nine children, you have to use a lot of grocery bags. Once we got the groceries put away at home, there were a lot of paper bags left over. This is why I wanted to come along. I would carefully open up the bags along the seams to create a large piece of paper. I used that to draw on for the week. I enjoyed it, but I didn’t realize I was making art.

Growing up, I shared not only my room, but also the bed, with two of my siblings. I realized that I enjoyed solitude. I enjoyed being alone with my thoughts. Art allowed me to create my own little universe, my own private space that I could control.

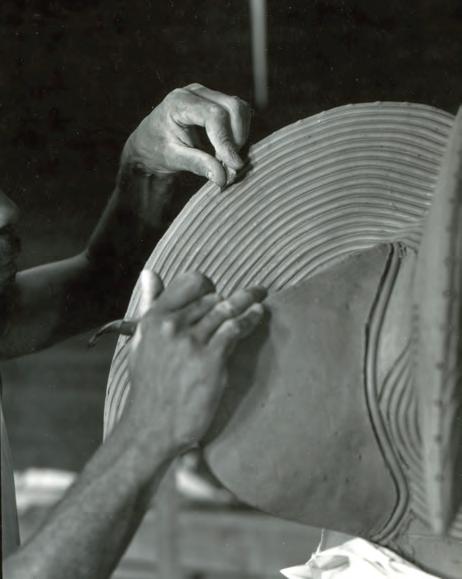

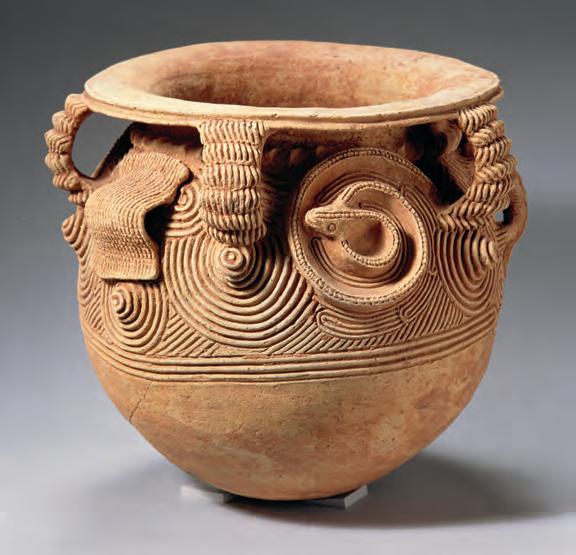

I fell in love with ceramics for a number of reasons. It was very physical. I was an athlete, and I enjoyed mixing and wedging clay and lifting kiln shelves. But the most important aspect of working in clay had to do with its utility.

y e i any came a ter com lete t e frst assignment in my Introduction to Ceramics class. The assignment was to make a cup. I realized that Mr. Gilliard, our ceramics professor at Hampton, was unloading the kiln while I was on my way to my educational psychology class. I decided to peek into the ceramics st io to see i my c s r i e t e fre. Mr. Gilliard put all the cups out on the table. He pointed out my cup and said, “That’s a really nice cup you made. You can use it in the dorm when you’re staying up all night studying for exams."

Now, I grew up in public housing. In public housing, your dad doesn’t have a workshop in the garage or in the basement. Nothing you consume is handmade. If you needed something, you went to a store and you bought it. It came from a factory. I loved that I could take this material—clay—that has no intrinsic value, and through the miracle of ceramics, turn it into something both beautiful and useful. en too ome aintings a ter my frst year o painting, I showed them to my parents. They looked

at them and complimented me. But I had to explain to them which side was up, and what they were about. However, when I brought home my pots, that wasn’t a problem at all. There is a universality to pottery, of making vessels; it is part of human culture. Much of what we know about ancient cultures is based on their pottery. So I just fell in love with clay.

That day, instead of going to my educational psychology class, I went back to the dorm to put Mr. Gilliard’s premise to test. I made myself a cup of instant co ee an t my eet on my es . ran t e c o co ee an sai to mysel is is t e feeling I want to have again.” From that point on, the only question I had of my academic professors and a isors as at o a e to o to ee ma ing pots?” That led me on my path.

MH: How do you refer to yourself? Do you see yourself as an artist, or a ceramist, or a potter?

DM: en eo le as me t at estion tell t em m a potter. And I think that’s important, because everything I make is a vessel. Most of the work I make starts out on the potter’s wheel. It has always fascinated me that when you are making a pot and working on the wheel, you’re not only shaping a wall, but you’re also shaping a volume inside. In many instances, the way that volume is shaped is more interesting than the appearance of the outside.

I do make a distinction, because some people use the term functional and utilitarian interchangeably. ere is a i erence et een t e terms. ainting has a function, but a painting is not utilitarian. A utilitarian object has a purpose beyond its own existence:

to hold something, to dispense something, to contain something else than what it is itself. That notion has always been important to me, and that’s why I prefer to be called a potter.

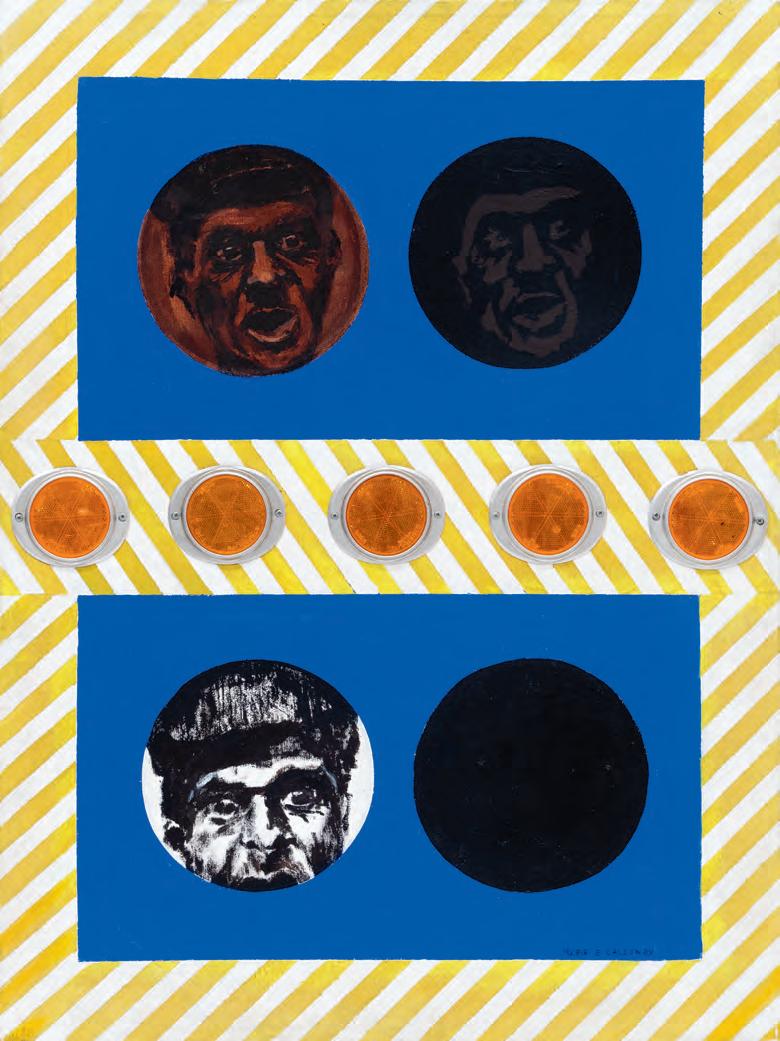

MH: Would you please tell me about the work “Violence is as American as Mom’s Apple Pie” (pl. 33)?

DM: Yes. It was in my MFA thesis show. The title is a response to the Black Panthers talking about how they were willing to defend their neighborhoods even if it resorted to violence. A congressman in Washington DC said he was appalled by the idea that these people, these people, were willing to resort to violence. H. Rap Brown, the Black Panther, responded, “Violence is as American as mom’s apple pie.”

The history of America is one of violence. The land was violently taken from Native Americans. Africans were violently brought here. And when we have a disagreement with another country, we go to war.

This piece was a reaction to the fact that Americans still have to come to grips with the idea that their culture—our culture, because I’m an American myself—is built on violent acts. Unfortunately this culture of violence, as Malcolm X said when JFK was assassinated, “is just the chickens coming home to roost.”

A utilitarian object has a purpose beyond its own existence: to hold something, to dispense something, to contain something else than what it is itself.

MH: How did you move from the more overtly political imagery in your work to the more abstract imagery in “Family Totemic” (pl. 32) and “Beaded Nyama Form” (pl. 27)?

DM: When I was hired at Syracuse University, my work was overtly political and in-your-face. I had a one person show at the Community Folk Arts Center in Syracuse, which I helped to found, and which was an extension of the African American program at SU. The s o as flle it images o anger an r stration. I was at the opening reception, just absorbing all the compliments. I noticed that there was an elderly white

lady, who I had seen at other cultural events, who wanted to talk to me. Towards the end of the reception, she saw her opportunity. She came over and told me she really loved the craftsmanship of my work, and how articulate it was in terms of expressing ideas.

But then she asked, in a soft voice, “Do you mind if I ask you a question?” I thought she was going to ask, “Who do I make the check out to?” But instead she asked me, “Is there anything positive about being Black in America? Or is it just a daily insult and frustration and anger?”

I don’t remember my response. It was a question that had never been asked of me before. The question

plagued me for a number of months. I began to realize t at my or as a o t getting isse o an sing that anger, and that energy, to catalyze making things.

I started thinking about my legacy: the legacy from which I come, but also the legacy I was leaving my children. Do they want to be the children of a pissedo ol man starte t in ing a o t con ersations had with my professor, Robert Stull, at the University of Michigan, who was also African American. Many of these conversations were about Africa and our African heritage. We discussed how that should be incorporated into our view of ourselves. It was about drawing upon the heritage of a millennia of advanced cultures.

I was considering how to celebrate the fact that we, as descendants of African slaves, found a way to survive and thrive in an environment that was incredibly hostile. We have overcome, or are in the process of overcoming. From there, my work started to celebrate my African heritage . I discovered that painterly part of me—the interest in surface, the interest in decoration, the interest in geometric patterning— was manifesting itself again. And in this case, it was inspired by my investigation of African culture and African decorative traditions.

3

8

10

11

(detail opposite)

14

Walter C Jackson

PORTAL NO. 4, 1985

painted wood, plastic, and fabric

24 × 24 × 4 inches

(detail opposite)

15

PORTAL NO. 1, 1985

wood, plastic, and fabric inc es

16

Walter C Jackson

PORTAL NO. 3, 1985

painted wood and plastic

24 × 24 × 4 inches

CEO, 1984

(detail opposite)

are it ea s an oc ing

Scarifcation Plate, 1985 glazed stoneware inc es

Scarifcation Plate, 1985

glazed stoneware inc es 30

David MacDonald

Scarifcation Plate, 1986

glazed stoneware inc es

24 × 13 × 8 inches

(detail opposite)

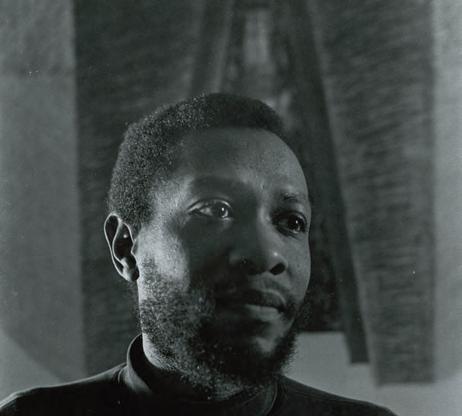

b. 1940, Holmes County, MS

Lives and works Edmeston, NY

Walter C Jackson during his residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, March 1982.

EDUCATION

1971 University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, Master of Fine rts c l t re

1963 Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, Bachelor of cience rt cation

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

1992 X-Ponent ron i er rt allery

1991 io esleyan ni ersity ela are

1990 en all allery e or

1989 Imprint, African American Museum of Nassau County, em stea

nts oint c l t re ar ron

1984 On the Wall or ollege amaica

1981 or ol tate ni ersity or ol

1979 c l ng se m no ille nitarian allery no ille

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2024 Spirit Keepers: Walter C Jackson, Marie JohnsonCalloway, and David MacDonald, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York, NY

2023 Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2019 RAiR at 50: Beyond the Gift of Time, Roswell Museum,

2008 RAiR at 40: Beyond a Gift of Time, Roswell Museum,

2001 The Politics of Racism, ABC No Rio; Lowe Gallery, the Hudson Guild, New York, NY

1994 Five Artists: Works in Progress os ell se m

1992 7 Rooms/7 Shows o . . ong slan ity Art in the Park ros ect ar roo lyn

1990 Hunts Point Sculptors allery or s ron

1989 ong oo rt enter ron 9 Uptown arlem c ool o t e rts e or University of Tennessee, Knoxville

1987 In the Spirit of Wood, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, NY

1986 The Artist’s Language: Conceptualizations Traditional and Modern, African American Museum of Nassau County, Hempstead, NY

Sculpture Dialogue, Visual Arts Center of Alaska, Anchorage

Joining Forces, Gallery 1199, New York, NY

Other Points of Departure, the Sculpture Center, New York, NY

1985 Carnival: Ritual of Reversal, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, NY

1984 eal rt ays art or

Technics: Art and Machines, The Alternative Museum, New York, NY

1983 CAPS Sculpture Grantees, City Gallery, Department o lt ral airs e or

Five Sculptors ita le allery e or

Painting and Sculpture, the Berkshire Museum, ittsfel

From the Studio, The Studio Museum in Harlem, e or Gallery 200, Knoxville, TN

Atlanta Life Insurance Company Fifth Annual National i ition an om etition

1982 What I Do for Art, Just Above Midtown Gallery, New or

1981 The Monumental Show 1981, Gowanus Artyard, roo lyn

1980 Dimensions and Directions, the Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson

Captured Light, Forest Avenue Consortium, Atlanta,

1977 Distinguished Artists Series, Jackson State ni ersity

1976 Tennessee Bicentennial Exhibition, Tennessee State se m as ille

1975 43rd Southeastern Semi-Annual Exhibition, o t eastern enter or t e rts inston alem

1995-98 Executive Director, Bronx River Art Center, NY

1984-86 Assistant Professor, York College, City University of New York, Jamaica

1971-80 Assistant Professor, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

n erson se m o ontem orary rt os ell

tlanta i e ns rance om any tlanta e or lic i rary c om rg enter e or t io se m in arlem e or se m o ologra y e or

Tennessee Museum of Art, Nashville, TN

2001 ROTUNDA GALLERY/BCAT Media Residency, roo lyn

1993– Artist-in-Residence, Roswell Museum and Art Center, 94

1991 Visiting Artist, Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware, OH

1989– rtist in esi ence ron i er rt enter

90

1987 e or o n ation or t e rts

1986 Outdoor Installation/Visiting Artist, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

1985 Workshop Residency, Museum of Holography, e or

1983 ello s i e or

1982 Artist-in-Residence, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY

1978 or s o isiting rtist arlottes ille

1977 Faculty Research Grant, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

AP. Ironcloud, “‘Spirit Keepers’ Showcases Three Black Artists’ Vivid Invocations to Other Realms,” Artnet. November 19, 2024.

L. G. Bryant, T. Jean Lax and L. Rocia Taboada, eds., Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces. New York: Museum of o ern rt . .

“Walter C Jackson,” The History Makers ecem er .

V. Raynor, “A Show of Shapes, from 10 Sculptors,” New York Times ly .

M. LaPalma, Technics: Art and Machines. New York: The Alternative Museum, 1984.

“Exhibit at New York College,” New York Voice. November 19, .

G. Glueck, New York Times ril .

From the Studio: Former Artists In-Residence. New York: The t io se m in arlem ril .

Southern Association of Sculptors all .

E. Fine, The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity. New or olt ine art an inston .

b. 1920, Baltimore, MD

d. 2018, Oakland, CA

Marie Johnson-Calloway, c. 1960s.

1976 San Francisco State University, Doctoral Equivalency

1969 Stanford University, CA, Experienced Teachers Fellowship

1968 San Jose State University, CA, Master of Fine Arts

1952 Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, Art Education

1939 Coppin Teachers College, Baltimore, MD

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2015 Marie Johnson-Calloway: Legacy of Color, Museum of African Diaspora, San Francisco, CA

2006 Homecoming: Marie Johnson Calloway, Past and Present, James E. Lewis Museum of Art, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD

2000 Shorenstein Building, San Francisco, CA

1999 Marie Johnson-Calloway On Stage: A Retrospective, 1950–1999, Triton Museum, Santa Clara, CA

1997 Bomani Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1996 Hope Street Revisited, Oakland Museum Sculpture Court, CA

1987 Hope Street, Oakland Museum, CA

1979 Selma Burke Art Center, Pittsburg, PA

California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA

1977 ni ersity o acifc allery toc ton

1975 Selma Burke Art Center, Pittsburg, PA

1974 Howard University, Washington, DC

1973 Triton Museum, Santa Clara, CA

1971 Marie Johnson, Brockman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

William Sawyer Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1968 San Jose State College, CA

1964 Lucien Labaudt Gallery, San Francisco, CA

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2024 Spirit Keepers: Walter C Jackson, Marie JohnsonCalloway, and David MacDonald, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York, NY

2023 West Coast Women of Abstract Expressionism, Berry Campbell Gallery, New York

2022 The Long View: California Women of Abstract Expressionism 1945–1965, Modern Art West, Sonoma, CA

2019 Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA

2011 Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA

1999 Artistic Diversity in American Art, City Hall, Mountain View, CA

1997 Face to Face: Looking at You Looking at Me, Triton Museum, Santa Clara, CA

A Visual Heritage 1945–1980, Triton Museum, Santa Clara, CA

1996 Family Matters, Bedford Gallery, Walnut Creek Civic Art Center, CA

1994 Rooms for the Dead, Center for the Visual Arts, Yerba Buena Gardens, San Francisco, CA

Odu’n De’, Odu’n De’, California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland

Domestic Landscapes, Falkirk Cultural Center, San Rafael, CA

1993 A Room with a View: Installation by Five Women, Gallery Concord, Concord, CA

1991 11 at 111, New California Sculpture, Oakland Museum Sculpture Court, CA

Viewpoints, 8 Installations, Richmond Art Gallery, Richmond, CA

li inatin efnition , San Francisco Craft and Folk Museum, CA

1990 Oakland Artists, 90’, Oakland Museum, CA

Beyond Fragments: After the Earthquake, Pro Arts Gallery, Oakland, CA

1989 Masks, Monkeys, Magic and Memories, Pro Arts Gallery, Oakland, CA

City Sites: Artists and Urban Strategies, California College of Arts and Crafts, San Francisco

1985 Spaces: Looking In/Looking Out, Museum of AfricanAmerican Art, Los Angeles, CA

1984 East/West: Contemporary American Art, California Museum of African-American Art, Los Angeles, CA

1983 Two Visions: Artwork by Marie Johnson-Calloway and April Watkins, Grand Oak Gallery, Oakland, CA

1981 Forever Free, Art by African American Women 1862–1980, Center for the Visual Arts, University of Illinois; Josyln Art Museum, Omaha, NE; Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, AL; Gibbes Art Gallery, Charleston, SC; The Art Gallery, University of Maryland, College Park; Indianapolis Museum of Art, IN

1977 Marie Johnson/Betye Saar, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA

1976 20th Century Black Artists, San Jose Museum of Art, CA

Other Sources: An American Essay, San Francisco Art Institute, CA

1974 Directions in African American Art, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

A Third World Painting/Sculpture Exhibition, San Francisco Museum of Art, CA

West Coast ‘74: The Black Image, E.B. Crocker Art Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1973 Black Mirror, Womanspace, Los Angeles, CA

USA Now, New York Cultural Center, NY

1972 Three Assemblage Interpretations: Noah Purifoy, Dale Davis, Marie Johnson, Brockman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

Eleven from California, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY

1970 Thirteen from San Francisco, Expo 70, Osaka, Japan

1968 New Perspectives in Black Art, Oakland Museum of California, Kaiser Center Gallery, CA

Alameda County Art Commission, Oakland, CA

The Brooklyn Museum, NY

California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA

The Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

James E. Lewis Museum, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD

The Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, SC

Kaiser Permanente Hospitals, CA

North Dakota Museum of Art, Grand Forks

The Oakland Museum of California

San Francisco Art Commission, CA

San Francisco General Hospital, CA

San Jose State University, CA

Santa Clara Civic Center, CA

Triton Museum of Art, Santa Clara, CA

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

1973– Associate Professor, Art Department, San Francisco 83 State University, CA

1969– Assistant Professor, Ethnic Studies and Art

73 Department, San Jose State College, CA

1969– Assistant Professor, California College of Arts and 70 Crafts, Oakland, CA

1969 Art Specialist, Santa Clara School District

1960– Owner and Manager, Mecca Art Gallery 61

1954– San Jose School District

1939– Baltimore School District

1993– West Oakland Senior Center

94

1992 Mama’s Room, San Francisco City College, CA Passages, Oakland Convention Center, CA

1989 Mt. Pilgrim Baptist Church, Mills College, Oakland, CA

1974 San Francisco General Hospital

AWARDS

2001 Lifetime Achievement Award, National Women’s Caucus for the Arts

2000 Florsheim Art Foundation, Tampa, FL

1994 San Francisco Library Foundation Award in the Arts

1987 Distinguished Work and Achievement Award in Sculpture, San Francisco Art Commission

1982 Pioneers of African American Art, Oakland Museum

BIBLIOGRAPHY

P. Ironcloud, “‘Spirit Keepers’ Showcases Three Black Artists’ Vivid Invocations to Other Realms,” Artnet. November 19, 2024.

J. Seed, “Unearthing a Treasure Trove of Bay Area Women Abstract Painters,” Hyperallergic. September 1, 2022.

“Marie Johnson Calloway,” Hella Charged & Lit. February 2018.

K. Jones, Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980. Los Angeles, CA: Hammer Museum, 2011, pp. 254–55, 262.

R. C. Smith, “California Assemblage: Art as Counterhistory” in The Modern Moves West. Pennsylvania, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, p. 147.

G. McNatt, “Artist Calloway Makes a Career of Coming Home,” The Baltimore Sun. November 19, 2006.

L. E. Farrington, Creating Their Own Image: The History of African American Women Artists. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 142.

V. Johnson, ed. Voices of the Dream: African American Women Speak. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books, 1996, pp. 18, 42, 65, 89, 104.

S. Lacy, Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1995, pp. 246–47.

S. Moore, ed., Gumbo Ya Ya: An Anthology of Contemporary African-American Women Artists. New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 1995, pp. 122–23.

an aa e e en rinci les Grapevine Visitacion Valley, Issue 66. January 1992.

S. Lewis, African American Art and Artists. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990, p. 205.

M. Roth, Connecting Conversations: Interviews with 28 Bay Area Artists. Oakland, CA: Eucalyptus Press, 1988, pp. 100–107.

M. Stainer, “Voices of Experience” in Beyond Power: A Celebration. San Francisco, CA: Southern Exposure Gallery, 1987, pp. 33-34.

C. Orr-Cahall, Hope Street. Oakland, CA: The Oakland Museum, January 1987.

. in eisc Art Collectors in and Around Silicon Valley Cupertino, CA: De Anza College, 1985.

A. Alexander Bontempts, ed., Forever Free, Art by African American Women 1862–1980. Normal, IL: Center for the Visual Arts, University of Illinois, 1981, pp. 92-93.

A. Frankenstein, “Unique Sculptures that Elicit Pathos” San Francisco Chronicle. April 4, 1977.

E. Honig Fine, The Afro-American Artist. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1973, pp. 58–60.

S. Lewis and R. G. Waddy, Black Artists on Art, vol. 2. Los Angeles, CA: Contemporary Crafts, 1969, pp. 176–77.

b. 1945, Hackensack, NJ

Lives and works Syracuse, NY

EDUCATION

1971 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Masterof Fine Arts

1968 Hampton Institute, Hampton, VA, Bachelor of Sciences

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2016 Vessels for Use and Contemplation: Ceramics of David MacDonald, Clayscapes Pottery, Syracuse, NY

2011 The Power of Pattern: New Work by David MacDonald, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

2010 Mostly Bowls: The Recent Work of David MacDonald, Williams-Insalaco Gallery, Finger Lakes Community College, Canandaigua, NY

2007 Sawtooth Arts enter, Winston-Salem, NC

2006 Hampton University, Hampton, VA

Edgewood Gallery, Syracuse, NY

Armstrong/Slater Gallery, Hampton University, VA

2004 Ceramic Road Show Conference, Riverside, CA

David MacDonald: Calabash & New Works, Chameleon Gallery, Cazenovia, NY

Diversity and Unity: Contemporary African American Ceramics, Baltimore Clayworks, MD

2003 Transcending Integration, Baltimore Clayworks, MD

Vessels for the Human Spirit, Schenectady Museum, NY

2002

David MacDonald, Works in Clay, Multiple Choice Gallery, Montgomery County Community College, Blue Bell, PA

Alternative Vessels, Mosely Gallery, Maryland State Arts Council, Baltimore

2001 Queens College, Charlotte, NC

David MacDonald: Recent Ceramics, North Carolina Wesleyan University, Rocky Mount

1999

David MacDonald: Recent Ceramics, Daura Gallery, Lynchburg College, VA

1998 David MacDonald, Ceramic Works, List Gallery, Swarthmore College, PA

Manchester Craftsman’s Guild, Pittsburgh, PA

1996 Munson Williams Proctor School of Art, Utica, NY

Decorative and Functional Work by David R. MacDonald, Eureka Crafts Gallery, Syracuse, NY

1994 Mostly Plates, Fosdick-Nelson Gallery, New York College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Alfred

1993 Rome Art Center, NY

Recent Ceramics by David R. MacDonald, Wilson Art Gallery, Le Moyne College, Syracuse, NY

1992 David MacDonald: Recent Ceramics, Tyler Art Gallery, State University of New York at Oswego

1991 Objects Ceremonial and Mundane, University Museum, Hampton University, VA

1989 Objects: Ceremonial and Traditional, Gallerie LaTaj, Alexandria, VA

Objects: Ceremonial and Mundane, Wells College, Aurora, NY

1988 Martha Gault Gallery, Slippery Rock University, PA

Manchester Craftsman’s Guild, Pittsburgh, PA

1987 Plate Forms, Hanover Gallery, Syracuse, NY

1986 Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, Utica, NY

1984 Gallerie LaTaj, Alexandria, VA

Rome Art Center, NY

1982 David MacDonald: New Works in Ceramics, Hanover Gallery, Syracuse, NY

Green Mountain College, Poultney, VT

1980 Cayuga Community College, Auburn, NY

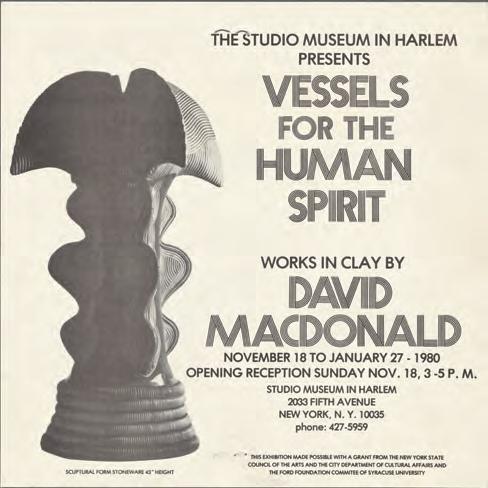

1979 Vessels for the Human Spirit, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY

1978 Gallery Seven, Detroit, MI

1975 David R. MacDonald: Stoneware Sculpture, Picker Art Galleries, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY

List Art Center, Kirkland College, Clinton, NY

1974 Kirkland Art Center, Clinton, NY

1973 Gallery Seven, Detroit, MI

Community Folk Art Center, Syracuse, NY

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2024 Spirit Keepers: Walter C Jackson, Marie JohnsonCalloway, and David MacDonald, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York, NY

50th Annual Pottery Show, The Art Show & Zakin Gallery at Old Church, NY

The Art of Craft, View Arts Center, Old Forge, NY

2019 Art at King’s Oaks, King’s Oaks, Newtown, PA

2018 The Very Mirror of Life: Ceramics at the Everson, 1968–2018, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

2017 A Century of Collecting: Ceramics at the Everson from 1916 to the Present, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

2015 Holiday Group Show, Gandee Gallery, Syracuse, NY

2014 In Touch with the Spirit, Ohio Craft Museum, Columbus

2015 Holiday Group Show, Gandee Gallery, Syracuse, NY

2013 Cousins in Clay, Bulldog Pottery, Seagrove, NC

2012 Enlightened Earth: The Ceramics Invitational, Arts Center Gallery, Nazareth College, Rochester, NY

2009 Contemporary Craft Masters, Community Folk Art Center, Syracuse, NY

2006 Ceramics Retrospective, Manchester Craftsmen Guild, Pittsburgh, PA

Roots, Schenectady Museum, NY

Inspired and Inspiring, Madelon Powers Art Gallery, East Stroudsburg University, PA

2002 Visions: An African American Journey in Clay, The Clay Studio, Philadelphia, PA

1999 Earth and Pigment, Stone Quarry Hill Art Park, Cazenovia, NY

Lubin House Gallery, New York, NY

1998 Contemporary African-American Ceramics, Irving Art Center, TX

Challenges of the New Millenium, Community Folk Art Gallery, Syracuse, NY

1997 Syracuse Anagama, Eureka Crafts, Syracuse, NY

David MacDonald & Jack White, Michael C. Rockefeller Arts Center Gallery, State University of New York, College at Fredonia

1993 Uncommon Beauty in Common Objects: The Legacy of African American Craft Art, The National AfroAmerican Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce, OH

Black on Black, Twelve Room Minus Two Gallery, Syracuse, NY

Georgia Southern University, Statesboro

Old Forge Art Center, NY

Founder’s Exhibition, Community Folk Art Gallery, Syracuse, NY

1992 Clay Heritage: African American Ceramics, Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, Philadelphia, PA

1991 Adams Art Gallery, Dunkirk, NY

Bertha Lederer Gallery, State University of New York at Geneseo

Marks of Vision, Lightner Art Gallery, Keuka College, Keuka Park, NY

1990 Spirits in Clay, Schweinfurth Memorial Art Center, Auburn, NY

Fine Arts Gallery, State University of New York at Oneonta

In Our Own Voices, Bevier Gallery, Rochester Institute of Technology, NY

1989 Pyramid Art Center, Rochester, NY

n ence onte orar rican erican rt, Hood College, Frederick, MD

era ic ra ition t ent r rican erican Art, Euphrates Gallery, Kansas City, MO

1988 Steuben Gallery, Utica, NY

Kirkland Art Center, Clinton, NY

1987 oice ro erican era ic , Community Folk Art Gallery, Syracuse, NY

1985 African American Crafts Invitational, The Torpedo Factory Arts Center, Alexandria, VA

ra ition an on ict a e o a r lent eca e 1963–1973, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY

1984 Containers as Form, Gallery Association of New York State, NY

New Vistas in Ceramic Arts, Pewabic Pottery, Detroit, MI

1983 Alternatives in Clay, Ruth Dowd Galleries, State University of New York at Cortland

Works of Clay, Oswego Art Guild, NY

1981 ro erican traction , Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

Coming Together, Cazenovia College, Cazenovia, NY

1980 Plate Show, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

1979 Contemporary African American Crafts, Brooks Memorial Gallery, Memphis, TN

1978 omet ing i erent omm nity ol rt allery Syracuse, NY

Hanover Gallery, Syracuse, NY

1976 Functional Ceramics Invitational, Art Center Museum, College of Wooster, OH

1975 Exposure 4, Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, NY

Kirkland College, Clinton, NY i ta ro erican rt, Fisk University, Nashville, TN

Second Ceramics Invitational Exhibition, Tyler Art Gallery, State University of New York at Oswego

1974 Radial 80, Xerox Corporation, Rochester, NY

Fingerlakes Invitational Exhibition, Memorial Art Museum, Rochester, NY

1973 Northern Illinois University, Dekalb Van Vechten Gallery, Fisk University, Nashville, TN

1971 Sixteen Artists, Gallery Seven, Detroit

1970 First Black Artist Exhibition, Sill Gallery, Eastern Michigan University

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Brooklyn Museum, NY

Community Folk Art Center, Syracuse, NY

Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

Newark Museum of Art, NJ

Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey, NY

Palmer Museum of Art, Center County, PA

Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

2024 Workshop Instructor, Strictly Functional Pottery National, Lancaster, PA

2023 Panelist, The Art of Craft, View Center for Arts and Culture, Old Forge, NY

2020 Juror, Unprecedented: Art Responds to 2020, View Center for Arts and Culture, Old Forge, NY

2015 Artist-in-Residence, Union Project, Pittsburgh, PA

2002 Lecturer, Wescott Community Center, Syracuse, NY

Lecturer, Ceramic Supply of NY and NJ, Lodi, NJ

Lecturer, Baltimore Clayworks, MD

Workshop Instructor, Pete’s Valley Craft Center, Layton, NJ

Workshop Instructor, Guilford Handicraft Center, CT

Lecturer, Community Folk Art Center, Syracuse, NY

Lecturer, Schenectady Museum, NY

Lecturer, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond

2001 Demonstration, Hazard Branch Library of Onondaga County, Syracuse, NY

Lecturer, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC

Lecturer, North Carolina Wesleyan University, Rocky Mount

Visiting Instructor, Tougaloo Art Colony, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS

2000 Visiting Instructor, Penland School of Crafts, NC

1998 Visiting Instructor, CraftSummer Program, Miami University of Ohio, Oxford

Visiting Instructor, Summer Arts Academy, Slippery Rock University, PA

Lecturer Craftsmen’s Guild, Pittsburgh, PA

Workshop Instructor, Slippery Rock University, PA

Workshop Instructor, Southwest Crafts Center, San Antonio, TX

Panelist, African Aesthetic in New World Clay, National Conference on the Education of the Ceramic Arts, Fort Worth, TX

1997 Visiting Instructor, Summer Arts Academy, Slipper Rock University, PA

Visiting Instructor, CraftSummer Program, Miami University of Ohio, Oxford

1996 Visiting Instructor, Penland School of Crafts, NC

Featured Artist, Fourteenth Annual WCNY Art Invitational Auction, WCNY-TV, Syracuse, NY

Lecturer, Clemson University, SC

1994 Visiting Instructor, Touchstone Center for the Crafts, Uniontown, PA

Visiting Instructor, CraftSummer Program, Miami University of Ohio, Oxford

1993 Artist-in-Residence, National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce, OH

Demonstrator for o ar efnition n a ination of African Craft Art Symposium, National AfroAmerican Museum and Cultural Center, Lila WallaceReader’s Digest Fund, Dayton, OH

S ea er at S o i ear o ontri tion a ton ni er it , Hampton University, VA

Lecturer, Lemoyne College, Syracuse, NY

Lecturer, East Texas State University, Commerce

Lecturer, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX

Lecturer, Norfolk State University, VA

Lecturer Georgia Southern University, Statesboro

1992 nstr ctor it fring or s o o c stone enter for the Crafts, Uniontown, PA

Instructor, Summer Arts Academy, Slippery Rock University, PA

Juror, Awards for WCNY-TV Exhibition, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY

Lecturer, State University of New York at Oswego

Lecturer, Hampton University, VA

1991 Adams Art Gallery, Dunkirk, NY

Lecturer, State University of New York at Fredonia

Lecturer, e elo ent o Per onal or , Cazenovia College, NY

Lecturer, State University of New York at Oneonta

1990 Lecturer, Rochester Institute of Technology, NY

Instructor, Touchstone Center for the Crafts, Uniontown, PA

Lecturer, So rce o n iration Conference, New York State Art Teachers Association, Cazenovia

1980 Judge, ent nn al rt an ra t air, Downtown Committee of Syracuse, NY

1974 Visiting Professor of Ceramics, Kirkland College, Clinton, NY

1971– Professor, Syracuse University, NY 2008

1970 Instructor, Ann Arbor Potter’s Guild, MI

1969– Teaching Fellow, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 71

P. Ironcloud, “‘Spirit Keepers’ Showcases Three Black Artists’ i i n ocations to t er ealms Artnet. November 19, 2024.

. . c ee mista icentennial ele ration or ll erican rt o rnal. Summer 2024.

“Emeritus Professor David R. MacDonald to Receive Honorary egree at ommencement S rac e ni er it . May 11, 2023.

a i ac onal ings a s Kings Oak Art. 2019. rt at ings a s Kings Oak Art. 2019.

C. Mellor, “Everson Museum displays its history for 50th nni ersary S rac e e i e , December 19, 2018. ont l era ic rt orea, volume 263. February 2018.

. c a i ac onal n ence ommitment an ntegrity era ic ont l . Jun./Jul./Aug. 2017.

. ellor e lay s t e ing S rac e e i e February 1, 2017.

“MacDonald and Mayes Honored as Trailblazers,” Syracuse Manuscript, vol. 2, no. 5. Spring 2017.

M. Eisenstadt, “Syracuse artist started his career as ‘an angry black man,’ but staying mad was hard,” Syracuse.com November 23, 2016.

C. Malone, “PBS Series Salutes Ceramist David MacDonald’s Work,” Syracuse New Times. November 23, 2016.

M. Tuskes, “The Pottery of Syracuse Ceramist David MacDonald to be Featured on Season Debut of PBS Show,” WAER. November 23, 2016.

D. Weisberg, “Clay Celebration Hopes to Fire Up Passion for Pottery,” Trib Total Media. 2015.

“Gandee Gallery,” Syracuse New Times. January 7, 2015.

M. Johnson, “Retired Syracuse University art professor David MacDonald, who has a solo show at Everson, says he backed into career as an artist in clay,” Syracuse.com. June 23, 2011.

Z. Dunn, “The Power of Pattern: New Work by David MacDonald.” June 2011.

K. Rushworth, “Vessels as Vehicles,” Central New York Magazine. July/August 2009.

“Celebrating an Artist’s Contributions,” The Post-Standard. February 4, 2007.

“African-American Artisans,” Home & Garden Television March 2001.

L. Bien, “Syracuse Artist on HGTV Special,” Home & Garden 2001.

Z. Bédy, “Studio Arts Professor Makes Current Cover of Ceramics Monthly,” Syracuse Record. October 14, 1996.

R. Zakin, “David MacDonald,” Ceramics Monthly. October 1996.

. . c ster e ections on rica rtist a i ac onal Fills Empty Vessels with Cultural Meaning,” Arts & Leisure 1993.

L. Oakley, “Ceramist Brings his Heritage to Oswego,” The Oswegonian. February 6, 1992

“This week at SUNY-Oswego,” The Palladium Times. January 30, 1992.

Clay Heritage: African American Ceramics. Philadelphia, PA: The Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, 1992, n.p.

O. Lukaszewycz-Polon, “Marks of Vision Exhibit to Open,” The Chronicle-Express February 6, 1991.

D. Roach, “David McDonald,” The Collector of Antiques and Art. October 1989.

S. McCorkle, “Guest Artist Spins His Wheel,” The Daily Mississippian. April 1, 1985.

“Ceramists Featured at Art Guild Exhibit,” The Palladium Times October 7, 1983.

“Show Depicts ‘Clay Vessels that Speak’,” 1983.

“Times Table,” Syracuse New Times. June 8, 1983.

“The Calendar,” Syracuse New Times. October 27, 1982.

T. Piche, “Earthly Origins Expressed in Ceramic Display,” Syracuse Herald. November 7, 1982.

“Oswego Artist to Judge Syracuse Crafts Fest,” The Palladium Times. June 30, 1980.

“The Studio Museum Brings Together Black Achievements in Art,” The Harlem Weekly. 1980.

“Sculptor Shapes His Life in Clay,” The Harlem Weekly January 2, 1980.

Vessels for the Human Spirit. New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, November 1979.

“Tyler Presents Ceramics Exhibition,” The Oswegonian. October 16, 1975.

r t an s go frst an oremost to t e artists o ma e t is show possible. Thank you to Walter C Jackson, David MacDonald, and the family of Marie Johnson Calloway: April Watkins, Heather Watkins, and Jasmine Williams for entrusting us with this work. It is a privilege to work with all of you. We are grateful to David for his public talk at the gallery during the show, and to Walter for his interview. Thank you to Portia Cobb for allowing us to publish her thoughtful interview with Johnson-Calloway from 1986. We are grateful for the various curators who shared their research with us as we put together this exhibition: Elizabeth Dunbar and Garth Johnson of the Everson Museum; and Lauren Hanson and Frances Lazare of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. For their assistance with image reproductions, we thank David, Walter, Heather, Jasmine, Angi Brzycki of Los Angeles Public Library, Emily Smith of the Oakland Museum of California, and Connie Choi and Habiba Hopson of The Studio Museum in Harlem. Lastly, thank you to the whole team at Eric Firestone Gallery for making all of this happen!

— Eric Firestone

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

Spirit Keepers: Walter C Jackson, Marie Johnson-Calloway, and David MacDonald

November 1, 2024 – January 10, 2025 on view at Eric Firestone Gallery 40 Great Jones Street, New York, NY

ISBN: 979-8-9885944-7-5

LCCN: 2025902906

Flyleaf, front: Detail of David MacDonald, Middle Passage Vessel, see pl. 31

Page 20: Detail of David MacDonald, Scarifcation Plate, see pl. 28

Flyleaf, back: Detail of David MacDonald, ea e a a or , see pl. 27

Interview with Marie Johnson-Calloway by Portia Cobb published in “Connecting Conversations: Interviews with 28 Bay Area Artists,” 1988. Reprinted with permission of the interviewer.

ery reasona le e ort as een ma e to supply complete and correct credits.

Publication © 2025 Eric Firestone Press

Exhibition photography © 2025 Sam Glass All artwork © the artist or artist’s estate

Reproduction of contents prohibited All rights reserved

Published by Eric Firestone Press 4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937

Principal: Eric Firestone

Managing Partner: Kara Winters

Senior Director: Jennifer Samet

Associate Director: Maddy Henkin

Research Assistant: Alabel Chapin

Photography: Sam Glass

Design: Isabelle Smeall

Printing: GHP

Eric Firestone Gallery 40 Great Jones Street New York, NY 10012

646-998-3727

4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937

631-604-2386

ricfrestonegallery.com