Flesh Walls: Tales from the 60s

Flesh Walls: Tales from the 60s

Eric Firestone Press 2018

Eric Firestone Gallery wishes to thank Martha Edelheit and her family for entrusting us with the responsibility and privilege of showing the work she made in the 1960s, and assisting the gallery with every aspect of this exhibition and catalogue. Thank you to Melissa Rachleff for an insightful and thorough essay about the work, as well as her enthusiastic, rigorous scholarship of the last ten years, which has brought the work of Edelheit and others to our attention. Dr. Andrew Hottle, Professor at Rowan University, has also made this exhibition possible through his extensive research and involvement with Edelheit’s work. We also thank the entire gallery staff and everyone involved with the catalogue design and production.

11 ¼ x 8 ¾ inches

By Melissa Rachleff

Martha Edelheit was part of the rule-breaking downtown Manhattan art scene of the late 1950s and early 1960s. She exhibited with Jim Dine, Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg, Lucas Samaras, and Robert Whitman, all of whom challenged abstraction’s dominance with their constructions, environments, and performances. Sensuality was frequently a theme downtown, and Edelheit’s explorations expanded beyond the boundaries set by her male colleagues. Her artwork is direct, exquisitely detailed, and frankly humorous. Combining diaries, dreams, fairy tales, and myth, Edelheit’s drawings and paintings reversed masculine tropes of power. “I’m against anything that seduces me into shallow water,” she wrote in her daybook in 1969, underscoring an uncompromising, radical vision that, because it operated on the margins of even the most adventurous art, was difficult to situate at the time. Her 1966 exhibit at the Byron Gallery brought Edelheit’s work to a broader public. But the show shook the complacency of New York’s sophisticated cultural audience, and tested their comfort with an eroticized female gaze. The nudes and fantasies in her early 1960s work anticipated debates about sexual identity, representations of the body, and eroticism, but not in the coolly conceptual mode of the 1960s and 1970s. Rather, Edelheit’s work aligns with the intensities and criticality of identity and representation in the 1980s. Her art was prescient in its unabashed confrontation with self-making and erotic subjectivities—a message to the future (fig. 1).

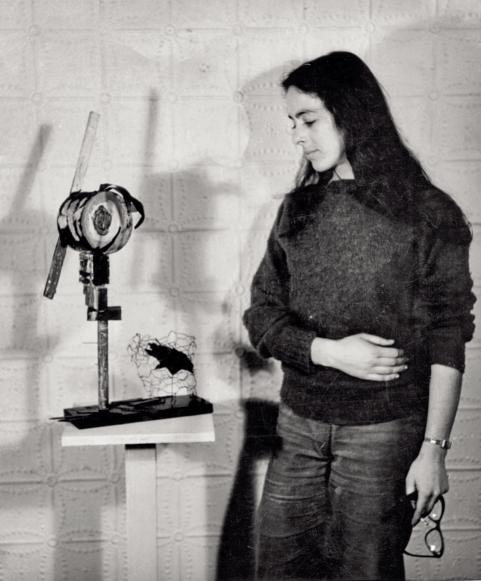

Born in 1931, Edelheit grew up in New York City and graduated from the prestigious High School of Music and Art in 1949. She completed two years of undergraduate studies at the University of Chicago, where she met medical student Henry Edelheit, whom she married in 1951. Returning to New York, Edelheit enrolled at Teacher’s College, Columbia University, and graduated in 1956 with a degree in early childhood education, while “Hank” became a psychoanalyst affiliated with the renowned New York Psychoanalytic Institute. At Columbia, Edelheit took classes with art historian Meyer Schapiro, but it was her subsequent apprenticeship with painter Michael Loew in the principles of geometric abstraction that gave her a sense of direction as a visual artist. However, Loew’s rigidity was ultimately unfulfilling. While on vacation in 1959 the Edelheits met a dynamic couple, the mathematician David Miller and artist Renée Rubin Miller, friends of Allan Kaprow. Renée Rubin Miller introduced Edelheit to Kaprow’s “action collages,” where the traditional

rectangular canvas was expanded and distorted in response to materials, from paint to scraps, from destroyed artwork to found objects. For Kaprow, such extension meant the artwork generated an environmental feeling, where nothing is fixed and space is not alluded to, it is actual. Edelheit began expanding in form and scale. “I wanted to draw a line across a wall and not have to cover the whole wall,” she wrote later.1 Her canvases contained materials that referenced her biography—newspaper clippings from the Yiddish press read by her grandparents, a license plate from one of her romantic trips with her husband, literature—and an explosion of brightly hued, painted canvas shapes, lined with wood or metal (fig. 2).

In fall 1959, Rubin Miller and her sister Anita collaborated with Kaprow on opening the Reuben Gallery, using the biblical spelling of the sisters’ last name, and Edelheit joined the gallery along with Dine, Oldenburg, Samaras, Rosalyn Drexler and others. Her first solo show opened in May 1960, and in 1977 she recalled this was a period of transition: “In the years ’58–’60 I had been trying to break away from the conventions of the ’50s and earlier, one way was to attack the rectangle (Motherwell called it a ‘window.’) [. . .] still using Cubist generated space and expressionist brushwork.” 2 Edelheit’s paintings in her Reuben solo show incorporated found materials and constructions that also meditated on the circle, a symbol of femininity.

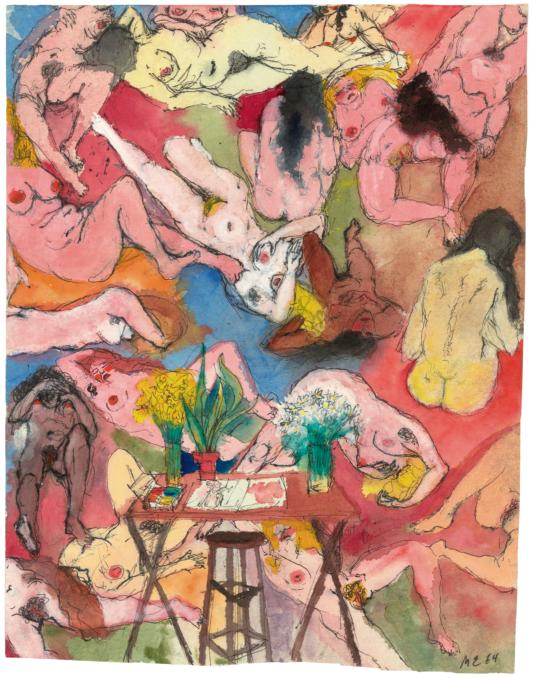

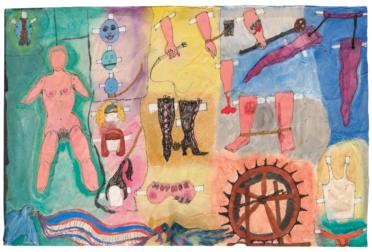

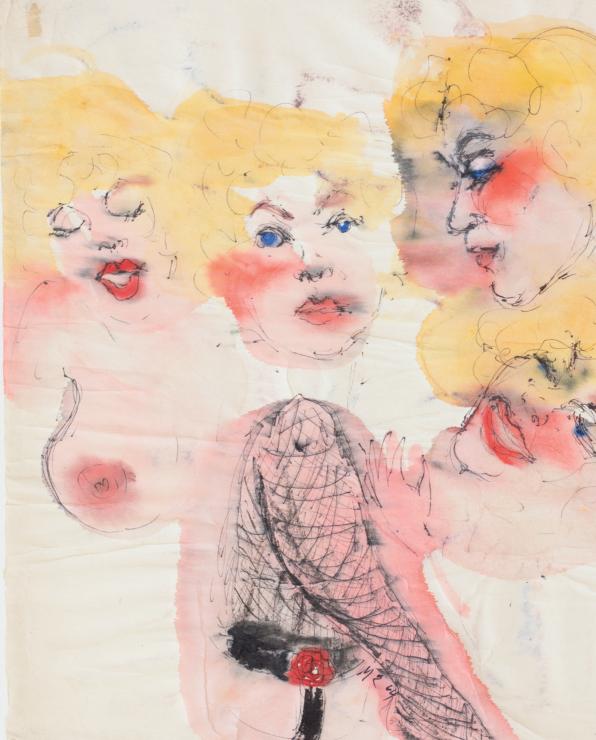

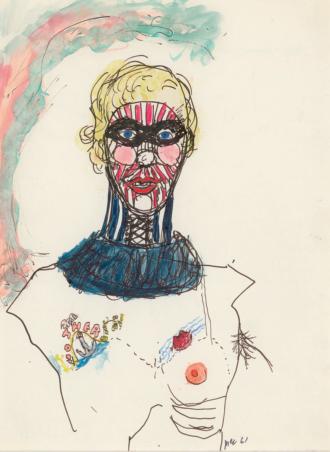

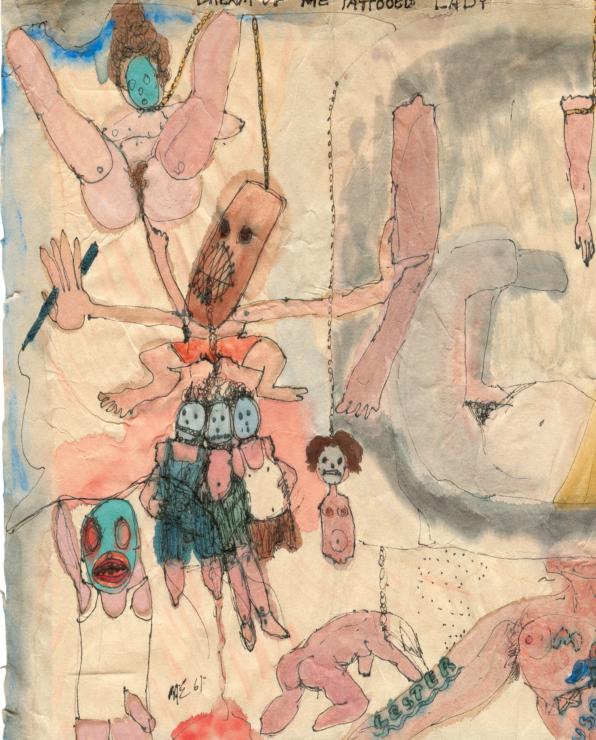

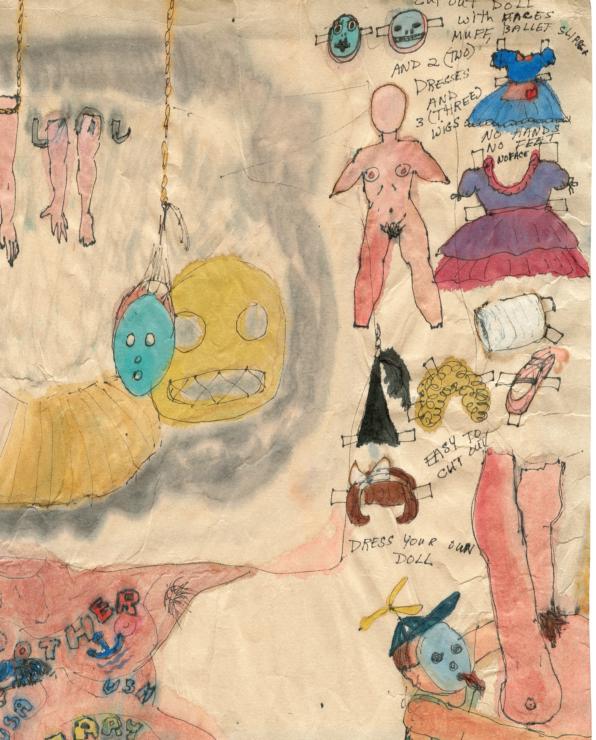

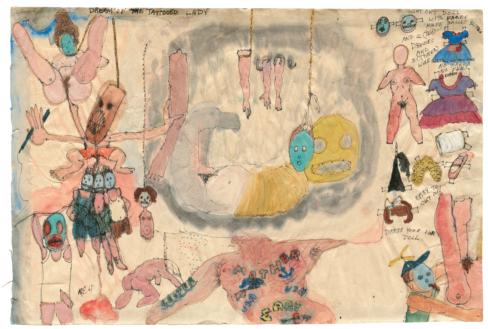

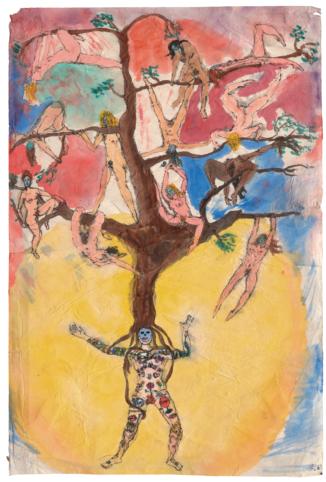

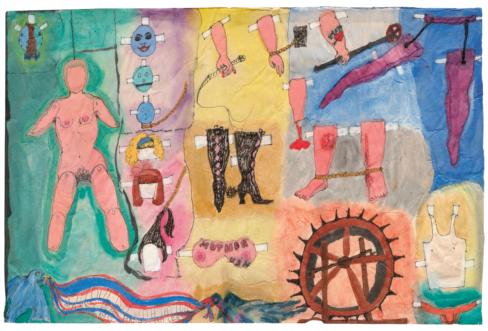

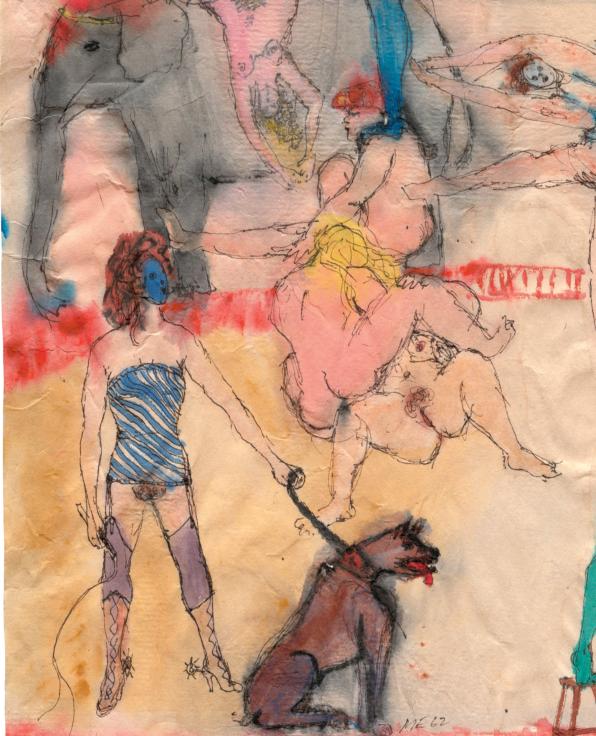

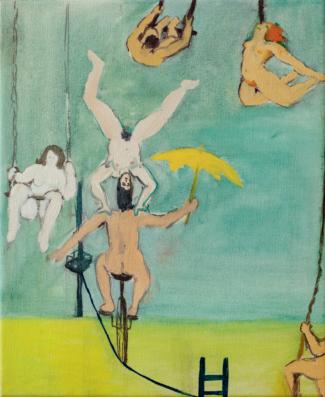

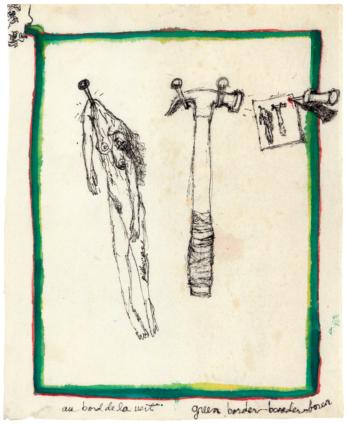

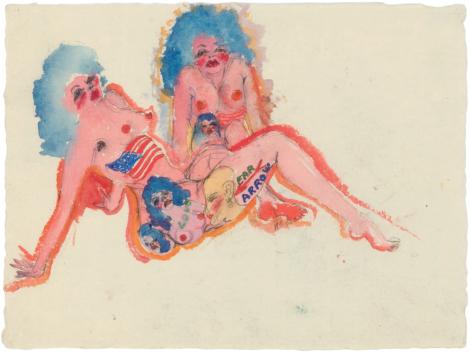

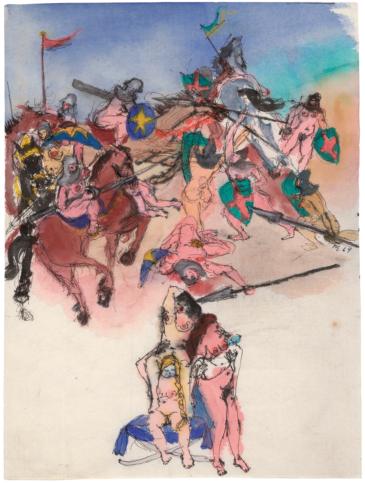

An extension painting from the Reuben was selected for the watershed New Media, New Forms exhibit in June and September 1960 at the Martha Jackson Gallery. However, Edelheit didn’t stay in the Cubist “new forms” arena for long. By the end of that year, she had made a series of watercolor and ink drawings that reverted to representational form, suitable for narrative. In this format she approached the canvas with an uninhibited, identifiable subject rendered in a style that was freely associative. “I did a whole group of ‘letters to the moon,’ and make believe ‘writing’ of letters,” she recalled. In these more literary works, Edelheit kept her collage method active, experimenting with objects found on the street and surface textures, including mixing sand, powders, glue, and cheesecloth with pigment. “It was out of my searching for my personal imagery as well as my internal dialogue battle with those I considered my peers (the boys) and competition (the boys) and the art historical past.” 3 Her quest for belonging led to a simultaneous series of ink and watercolor drawings on rice paper that portrayed tensions about gender roles and sexual dominance replayed as myth, fairy tales, circuses, games, and tattoos, influenced in part by an erotic Japanese “pillow book” that mathematician David Miller shared with her. Initially, her drawings expressed her reaction to the graphic images she encountered (fig. 3). These small works absorbed the artist’s energy in fantasies that sometimes migrated into her moon-themed work.

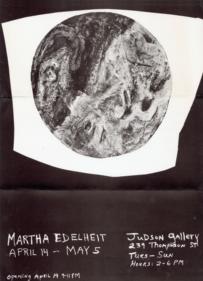

In his capacity as curatorial adviser, Kaprow invited Edelheit to exhibit this series at the Judson Gallery in April–May 1961 (fig. 4). Critics noted her shift away from extension paintings. Art News ’s Jill Johnston suggested Edelheit was “working out several private concerns” and had “no use for esthetic niceties.” Johnston might have meant that abstraction’s compositional rules no longer concerned Edelheit. And Johnston astutely picked up on the circular motif and enumerated its recurrence “as head, moon, female,” all set within the artist’s signature “compositional ballast.”4

After the exhibit closed, the Edelheits toured France, Italy, Greece, and Turkey, and fulfilled Martha’s wish to gain a much longed-for art history education. The tour, she wrote later, “completely revolutionized my vision of what art was about,” 5 and she began to make ink and watercolor images of sensual scenes that mined classical ideals. “I was never intending to show them to anyone,” Edelheit wrote to a colleague, “but [Lucas] Samaras saw them and liked them and in 1964 showed them to [dealer] Ivan Karp and he showed them in Provincetown [MA] at his first O.K. Harris [gallery].” 6 There is no surviving record of how the drawings were received, but in 1973 art critic Rosemary Mayer encapsulated that series, which culminated in 1966, as “depicting the adventures—sexual and otherwise—of different female heroines.” Mayer noted that, unlike the work of other female artists of the time, the drawings “had the intensity one associates with some of the startling art of the insane. Her attempt at depicting narrative brings to mind religious narrative painting of the saints.” 7 Mayer’s insight into Edelheit’s fevered intensity is apt; such overt passion commonly fell outside of advanced contemporary art of the sixties. 8

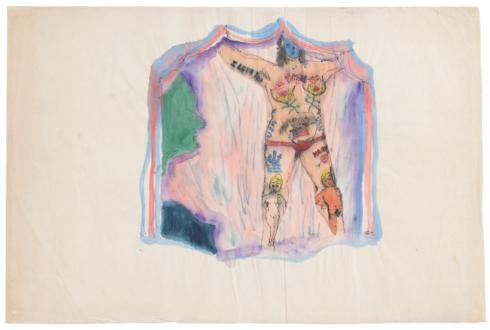

After the closing of the Reuben and Judson galleries in 1962, Edelheit, like many other female artists, was left without a venue to show her work at a transitional moment. No longer interested in abstraction and desirous of parsing what she had learned from her European studies, Edelheit began to study the figure, striving for technical mastery. She began by making self-portraits set within the confines of a feminized space, using mirror reflections as a trope. In the two-panel Chrysanthemum Wallpaper of 1962, a gold-framed mirror provides a 360-degree view of an interior space awash in an irregular pattern of yellow-orange chrysanthemum blossoms against a vibrant red background. It could be a “drawing room,” both metaphorically and actually, a gendered space where society women gathered. The dominance of the red makes the space oppressive, if not repulsive, the opposite of a “room of one’s own.” Similarly, in Edelheit’s 1963 Tattooing Yellow Rose Wallpaper, the mirror offers the full view of a room, this time the artist’s studio (where a tin of paintbrushes and pots of paint are situated on the left side, with a playgirl calendar on the wall),

Two nude female figures, one with dark hair and one bald, are pictured in the mirror. The bald figure, an artist, is gazing up, not at the viewer, but at herself, reflected in the act of tattooing. Across a table a dark-haired figure lies prone, her back to the viewer. On her left shoulder is a star tattoo and, across her lower back, dotted lines referencing fruit (a still life perhaps?). The skin is a map for an elaborate tattoo in progress. The bald figure grips a tattoo needle; the tip points at a heart with

“ME,” the artist’s initials set in the center. “ME” is a self-reference, a double self-portrait of Edelheit literally and figuratively. The figures are the artist; and the artist is captured in double acts of self-making. Similar to the chrysanthemums, roses proliferate in the background, flattening the field, contrasting with the mirrored scene. These large-scale paintings, some as wide as seven feet, were inquisitive confrontations the artist was having with her own subjectivity in her private studio, circumscribing new territory; they were not strictly autobiographical and not strictly figurative. 9

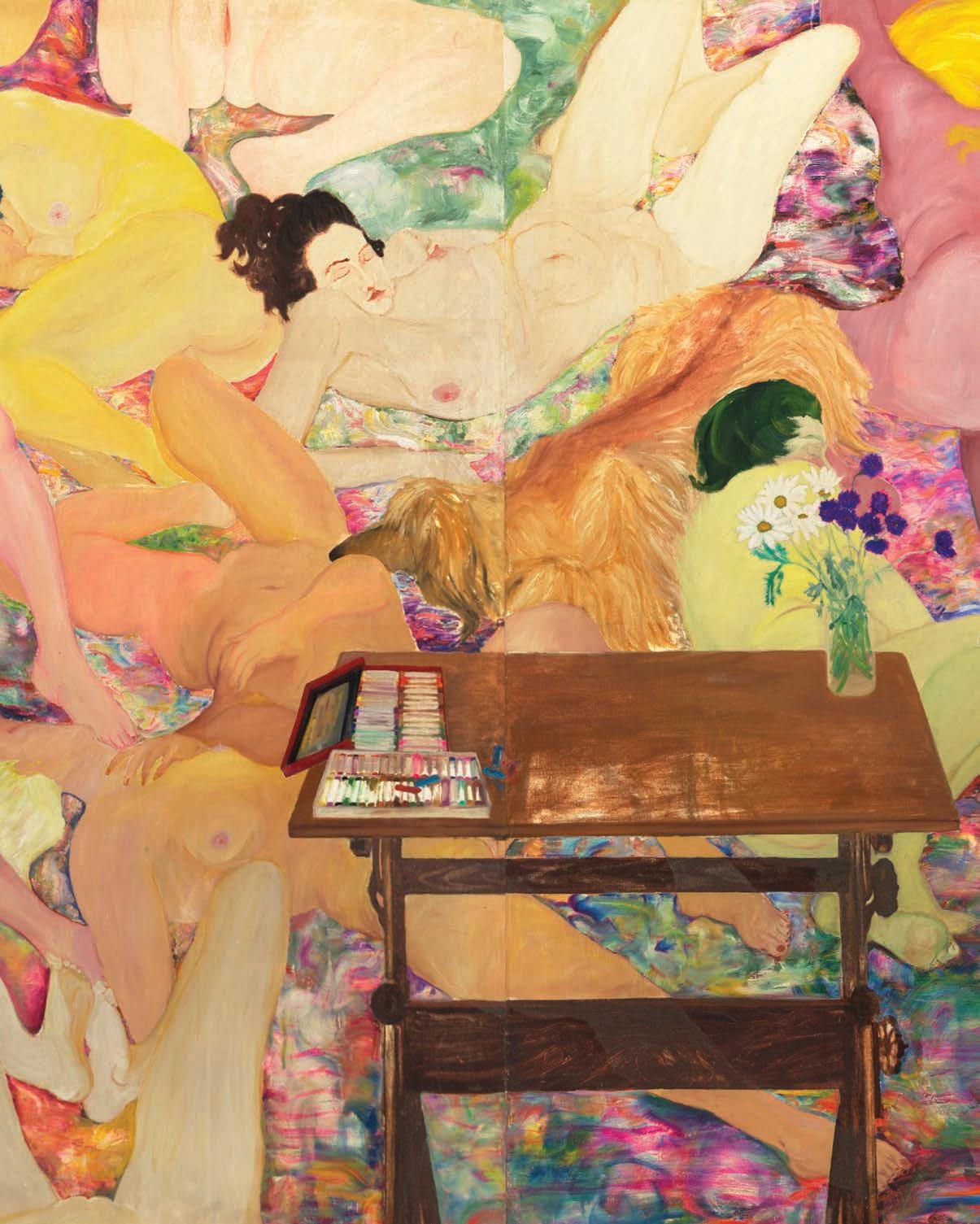

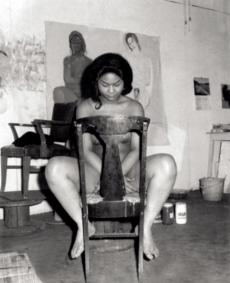

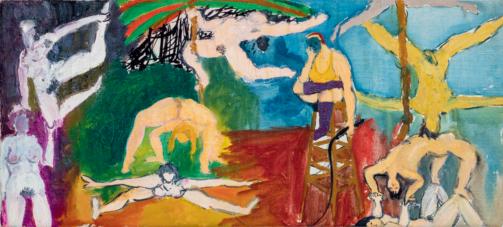

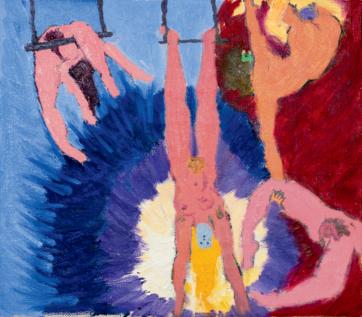

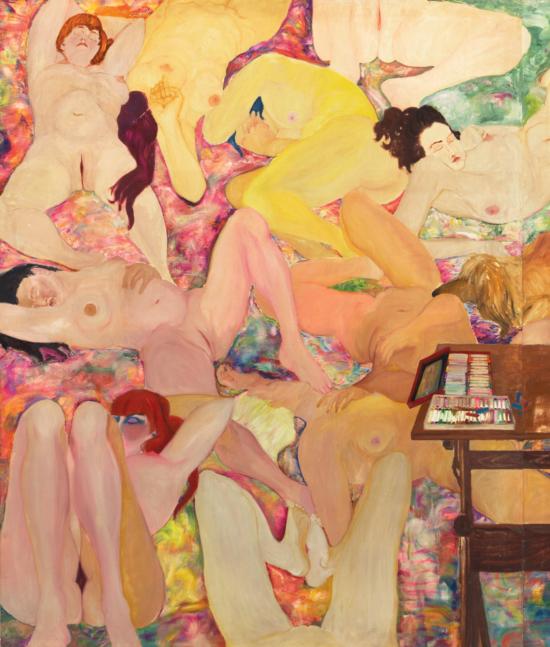

This layered balance continued in her next series, all made from working with live models, male and female, begun in 1963 (fig. 5). The models were nearly all high school students, the children of her friends and her husband’s associates. In the sanctity of her rented studio in the Upper East Side’s then declining Hotel Wales, Edelheit worked with one model at a time. The paintings depicted nudes in groups, yet each was constructed from many individual studies. “Each time I do a painting and work from a model,” she recorded in her daybook, “I have to teach myself to see again. My hand-eye never moves automatically. Each line, each relationship is a new disaster, a new discovery. Any piece of art is not spaces or separations, but the relationship between them. In a

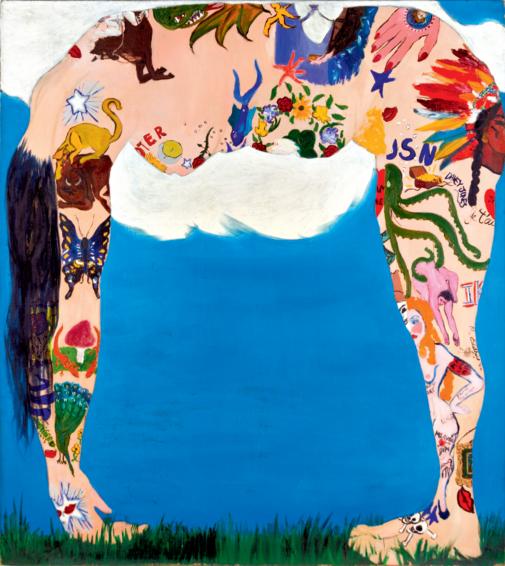

painting there is as much force in a box, a chair, a face, a cunt—all objects are equal. Only some are more equal than others.” 10 The paintings did not convey such detachment. Much like in her watercolors, exuberance and fantasy operate throughout the picture plane. Bodies fall, float, relax with knees bent, genitals peeking through, or lounge on their sides, sleepily gazing at some point in the distance but not quite at the viewer, and not at one another. The nudity becomes playful, not unlike the wallpaper in the self-portraits. Because she used live models who had to sit for hours, there is a quality of contemplation interior to each figure. She called these tableaux “flesh walls,” a loose reference to an off-color joke made by W. C. Fields that she enjoyed in college. Indeed, the work was intended to convey both pleasure and humor, to draw viewers into the wonders of color, flesh, and play. “All ooze is encased in some kind of skin—transparent, osmotic, porous,” Edelheit wrote about the role flesh plays in human anatomy. But her thoughts were deeply connected to the painting process and figurative representation. “What we see is skin-enclosed structures, and the relationships between them. If the skin (surface) is treated with sensitivity and sensuousness— delicacy—it creates the work.” 11

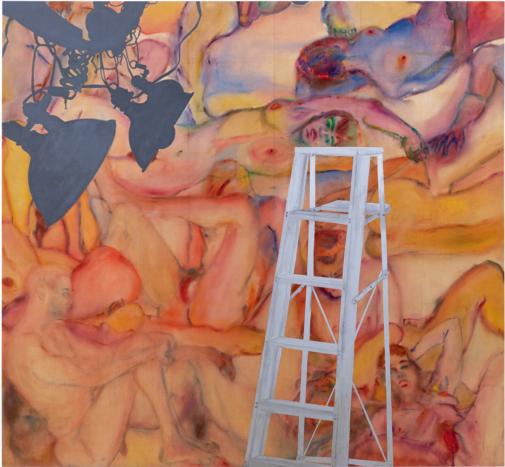

During the mid-1960s, Edelheit mostly segregated her paintings by gender; female models were not part of the tableaux she created for the males. And while the bodies—her “flesh walls”—were supple, Edelheit recorded signs of her own presence, her authorship of the situation. These areas are sometimes set off by a black-and-white palette or by the use of realist perspective in an otherwise difficult-to-determine space. Like the wallpaper paintings, the nude bodies become part of an imaginary sphere; they are decorative. The incorporation of the studio space itself allows the viewer to decode the situation as constructed. For those familiar with the history of art, Edelheit’s “flesh walls” reference Renaissance painters (especially Rubens and Michelangelo) as well as Byzantine-era church paintings and classical Greek sculpture, an aspect explored by art historian Andrew D. Hottle (see pages 64–73).12

Visitors to Edelheit’s studio in the mid-1960s would have been struck by the scale and ambition of her “Flesh Walls.” A friend, the food writer Barbara Kafka, recommended Edelheit to an uptown dealer she knew, Charles Byron, a specialist in Surrealism who had recently opened a gallery on Madison Avenue. At the time, most uptown galleries based their businesses in the secondary market, or work acquired from estates and consignment. This meant that the galleries that supported current art, or the primary market, were a small group that included Richard Bellamy’s Green Gallery, Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery, the eponymous Leo Castelli, Sidney Janis, and Martha Jackson galleries, and a few others. However, that was beginning to change. The extraordinary rise and commercial success of Pop Art beginning in 1962 prompted many secondary market galleries to include younger, adventurous artists in their programs not because they felt it would be lucrative, but because living artists generated more excitement, which helped the galleries’ visibility.

This was most probably the case with the Byron Gallery, founded in 1962 at 1018 Madison Avenue near Seventy-eighth Street.13 Byron selected Edelheit’s drawings for a 1964 group show, and several sold.14 He also included Edelheit (along with more than fifty other artists) in his wellreceived February 1965 Box Show. Her contribution merged the tattoo motif and (in a nod to Byron) a surrealist gesture: Edelheit transformed a mannequin bust into a curiosity cabinet. She painted the front of the form with an array of birds, flowers, butterflies, lips, and other insignia associated with tattoos; the back of the form incorporated more impressionistic tattoos that surround the artist’s self-portrait. Splitting the torso in half, from shoulder to waist (a violation of sorts), the dismembered female form opened like a book. Lined with a fine metal chain, the open view revealed organs, including a painted anatomical heart, and a place to hide relics from prying eyes (fig. 6).15 When the show closed, Charles Byron invited Edelheit to show her Flesh Wall paintings and new drawings—a series loosely based on legendary female pilot Amelia Earhart—in April 1966. She commanded the entire space (there was a concurrent show in the back room of small paintings by George Sakier).

As Rachel Middleman’s Radical Eroticism reveals, 1966 was a cultural break from the past, the year galleries “intersected with the cultural phenomenon of the sexual revolution and the surge of interest in erotic art.” Moreover, exhibiting art that was overtly sexual “opened up a space in which artists could publicly contest and reshape visual representations of sexuality with profound social consequences.” 16 However, the vast majority of the work exhibited was made by men, conceived for a straight-male gaze. Such open erotic expression reverberated through the late 1960s, ushering in the 1967 summer of love, and in 1968 sexual liberation joined the antiwar movement. Later this was framed as a new youth culture, but it reinforced stereotypes about gender. Middleman’s contextualization of Edelheit includes the chauvinism of the era and is not solely aligned with the erotic art trend. Her more expansive view shares a sensibility with populist writings like Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl, which advocated for female financial independence and sex before marriage (thanks in part to the pill), but did not necessarily challenge the social order—just its mores. Brown’s partial advocacy was easier to assimilate socially than the opinions of theorists like Simone de Beauvior, who persuasively argued that women were conditioned to accept male dominance. “I tried de Beauvoir’s Second Sex [1949] in the late 50s, or early 60s and it nearly destroyed my marriage, so I stopped trying to read it. I identified with everything she wrote,” Edelheit remembered, but during the early 1960s she was conflicted about the women’s movement. She wanted to be an artist, not a “woman artist.” “It created a lot of pain and conflict.” 17 Nonetheless, Edelheit’s refusal to be marginalized was expressed through a carnal female subjectivity coupled with a desire to master classical technique. This formed the core tension in the Flesh Wall paintings.

Byron Gallery framed Edelheit’s series not as a reckoning with female sexuality but as “a major contribution to the current American painting of the figure.” In their definition, this new type of “figure painting” moved from the postimpressionist influence of 1950s figuration toward a more clinical, direct approach best epitomized by Philip Pearlstein. The muted emotive range better fit the cool Pop sensibility, and the gallery ascribed such detachment to Edelheit’s large-scale paintings. They were on firmer ground with the Flesh Wall’s physical impact, noting that the “numerous figures” within each painting “continued into the environment beyond,” the frame. And linking the mammoth scale to Pollock, the gallery aligned the paintings with “the all-over” compositional approach: “The resulting fusion of an acute sense of human reality with the physical properties of paint is strong and original.” 18

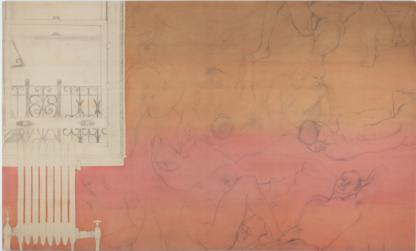

This abstraction of Edelheit’s project into themes of scale and paint kept the sensuality of the work at arm’s length. All together, there were forty-seven artworks in the show, including small sculptures from mannequin parts, drawings, and watercolors. Four of Edelheit’s human-scale Flesh Wall canvases dominated the gallery, and the effect was architectural; they transformed the space into a lusty environment (figs. 7 and 8). Two of the canvases, Flesh Wall with Table and Flesh Wall with Pigeon, comprise female nudes; one painting, Flesh Wall with Ladder, has male figures on

the bottom frame. Only Flesh Wall with Window includes solely male nudes (fig. 9). It is also the only painting done nearly monochrome, with an understated quality that the female paintings avoid. Edelheit was deliberate in differentiating the male nudes “in pencil with wash—very pale and pastelly compared to the female brashness, and always there has been an ironic sense underneath.” 19 The ironic part, however, was missed by most critics, who tended to literalize the difference and question its appropriateness. One critic did pick up on the layered nuances of the series. The titles were the giveaway; they referenced Edelheit’s presence, particularly the materials she had used to make the paintings. The reviewer for Arts Magazine described Flesh Wall with Table as incorporating a “superimposed black-and-white ‘snap-shot’ of the artist at work,” which brings the artist “pictorially within the realm of her canvas.” 20

Vitrines placed in the center of the Byron Gallery held some of Edelheit’s works on paper, finely detailed, narrative watercolors including Amelia Departs, acrylic on aluminum foil, in which the heroic female, masked and nude except for cape, belt, and boots, steps into a helicopter (fig. 10). The reflective foil creates an underwater, otherworldly aura befitting the subject. This Amelia Earhart is reborn from her crash into the Pacific Ocean as an action figure. Her nudity is a form of power and confidence, not despite her gender but fully inhabiting female power. In resituating

Earhart as not a woman in a man’s world but a woman in control of the world, the drawing functions as recompense for the aviator’s tragic demise. The artist Lil Picard, writing for the Village Voice, noted Edelheit’s affinity for Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt in her pursuit of “a sex-dream-world fantasy” and her attraction to reflective surfaces.

Edelheit extended the use of shiny paper to her invitation design for the show. Using a drawing depicting a mannequin leg in fishnet stockings, Edelheit had printed the image onto shiny pink paper, the same type used to wrap stockings in department stores (fig. 11). The gallery staff “thought it so ‘sleazy,’ which was exactly what I wanted,” she recalled. Edelheit explained the invitation’s message: “The drawing is of a dummy’s leg I had in the show. It was covered with the fine steel mesh chain, a ‘knight in armor’ stocking, byzantine, sick porno and high fashion combined.” 21

Not surprisingly, the exhibit engendered debate. While some critics thought the erotic turn was part of a commercial ploy, the latest trend spurred by galleries, others were troubled. There was not yet a language for describing female artists who explored sexual themes in their work. “I was aware of the intense sexual sensual context of the idea—it was like creating a private harem of women for myself,” Edelheit remembered. For some, Edelheit’s work was outré. Her paintings

were characterized as a curiosity, not as a new figuration. “They never seemed to see it was about portraiture and perception,” she wrote. 22 But at issue was not merely perception as a working method. Perception in terms of the public experience meant a confrontation with a fully actualized female artist who refused to submit to patriarchal rules concerning the body. No one was ready for that in 1966.

One of the most important areas of cultural liberation today is sex,” Allan Kaprow wrote in a spirited defense of Edelheit’s Byron Gallery show in the Village Voice, framing the Flesh Wall series as part of the burgeoning counterculture. 23 However, his interpretation overemphasized sex and overdetermined gender, circumscribing Edelheit (and other women artists) by describing them as having a female essence. While she appreciated his support, she did not agree, and most especially did not see herself operating solely as a female artist. Her source material was far broader and more nuanced. “It was not until 1969–70 that I started (reluctantly) to get involved in the women’s movement,” Edelheit wrote. “It created the same kind of revolution in my head that the trip to Europe had done earlier. If the work preceded the movement by ten years, the movement clarified and made conscious to me what I had been doing and experiencing, and has nurtured and provided a support system for me that never existed previously.” 24 By 1969, after a decade of exhibiting in New York City’s most adventurous venues, Edelheit found a place better aligned with her ideas and sensibility. New downtown galleries hospitable to women artists emerged, including SOHO20, which Edelheit joined. She also found, as did many other women artists, that experimental film and video were somewhat more welcoming due to their relatively brief history; the form did not belong exclusively to men. Edelheit explored and extended her art with cinema and produced several films, including the renowned Hats, Bottles, and Bones: A Portrait of Sari Dienes in 1977. The 1970s were a time for forging and renewing alliances with artists Joyce Kozloff, Maria Lassing, Carolee Schneemann, Miriam Schapiro, among others. But that era is a different chapter.

Edelheit’s work of the 1960s suspends tension between sensuality and the principles of painting. Her project remains radical because it resists easy assimilation into conventional art historical categories. And that is why her art retains its immediacy and relevancy fifty years on.

1 Martha Edelheit, draft letter to Carolyn Staughton, Women’s Studies Program, Cornell University, October 1977. Martha Edelheit papers, private collection, Sweden.

2 Edelheit, draft letter to Staughton.

3 The moon was a frequent image in art of the early 1960s, due to the national enthusiasm for Kennedy’s plans for space exploration. Edelheit, draft letter to Staughton.

4 J[ill] J[ohnston], “Martha Edelheit,” Art News 60, no. 3 (May 1961): 64.

5 Martha Edelheit to Carolyn Staughton, Women’s Studies Program, Cornell University, October 12, 1977. Edelheit papers.

6 Edelheit, draft letter to Staughton.

7 Rosemary Mayer, “Erotic Art Gallery,” Arts Magazine 47, no. 6 (April 1973): 76.

8 Another context that should be investigated for its correlation with Edelheit’s erotic artwork was the proliferation of edgy, underground comix artists like R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson, whose visionary strips similarly prodded mainstream mores and unabashedly pursued psycho-sexual visions, but unlike Edelheit, did so from a decidedly heterosexual male perspective.

9 This is an area of exploration by Lucas Samaras, and a future exhibit should compare these artists, as they were extremely cognizant and supportive of each other’s work during this period.

10 Quote in Edelheit’s typed document “Daybook Notes.” This passage is from an excerpt from 1966. Edeheit papers.

11 “Daybook Notes,” 1968. Edelheit papers.

12 Andrew D. Hottle, “Martha Edelheit, Womanhero ,” in The Art of the Sister Chapel: Exemplary Women, Visionary Creators, and Feminist Collaboration (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014), 229–242.

13 Byron’s clients included art patrons Brooke Astor and Adelaide de Menil, financier John D. Murchison of Dallas, Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun, and food empire chairman Henry J. Heinz II, who purchased a sculpture by Edelheit. Folders: Byron Gallery, Invoices Artists C-N, 1963–66, and Invoices, Byron Gallery Artists N-O, A-C, 1963–1967, Box 15, Byron Gallery records, 1959–1991. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

14 Byron Gallery records indicate that drawings were sold to collectors Henry J. Heinz II and Gerald Le Roux. Folder: Byron Gallery, Edelheit, Martha (B3.11), Box 3, Byron Gallery records. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

15 Other artists in the show, predominantly male, included Walter De Maria, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Lucas Samaras, and Robert Watts. Folder: Box Show [2] Scrapbook 1965 B12.1, Box 12, Byron Gallery records. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

16 Rachel Middleman, “Figures of Fantasy,” in Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 76, 1.

17 Edelheit, draft letter to Staughton.

18 Folder: Byron Gallery, Edelheit, Martha (B3.11), Box 3, Byron Gallery records. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

19 Edelheit, draft letter to Staughton.

20 Colta Feller “Martha Edelheit,” Arts Magazine 40, no. 8 (June 1966): 49.

21 Edelheit to Staughton, October 12, 1977.

22 Edelheit, draft letter to Staughton.

23 Allan Kaprow, “Female Art: No Games,” Village Voice , April 28, 1966, 12.

24 Edelheit to Staughton, October 12, 1977.

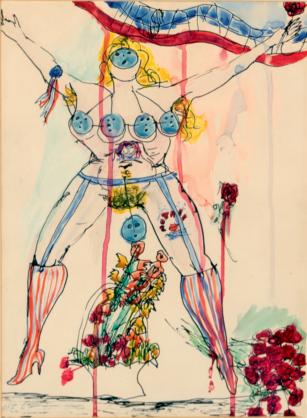

Miss America . . . 1961

Ink and watercolor on paper

11 x 8 ⅛ inches

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

11 ¾ x 17 ½ inches

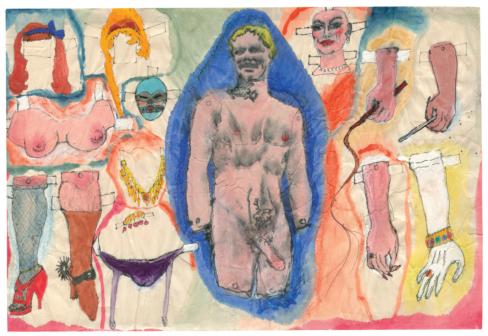

Mr. America’s Cut Out Dream 1961

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

11 ¾ x 17 ¼ inches

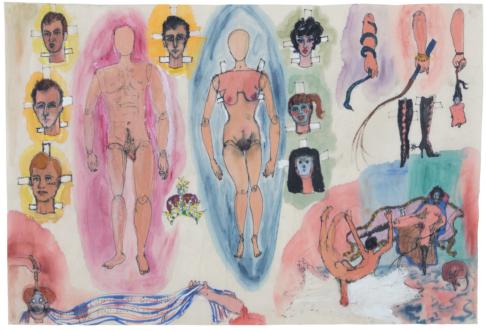

The Life and Loves of the Lizard 1962

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

11 ⅞ x 17 ½ inches

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

17 ¾ x 12 inches

12 x 18 inches

50 x 50 inches

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

11 ¾ x 17 ½ inches

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

12 x 17 ½ inches

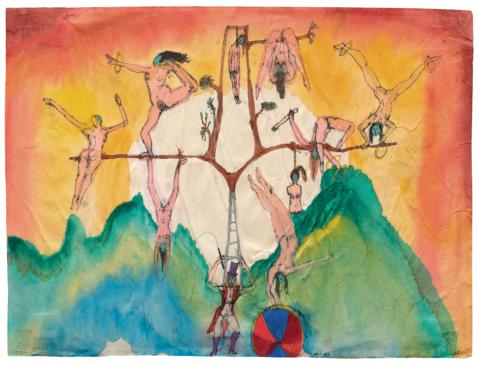

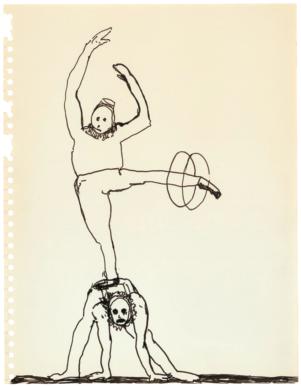

Balancing Acts 1963

O il on unstretched canvas

20 ½ x 9 ¼ inches

O il on unstretched canvas

15 ¾ x 13 ⅛ inches

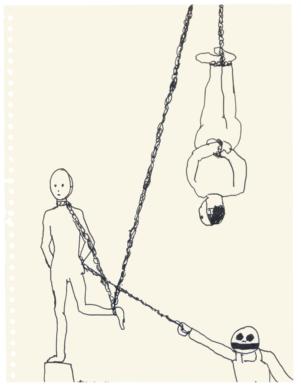

On the Ropes 1963

Oil on unstretched canvas

8 x 7 ⅞ inches

O il on unstretched canvas

8 x 9 ½ inches

8

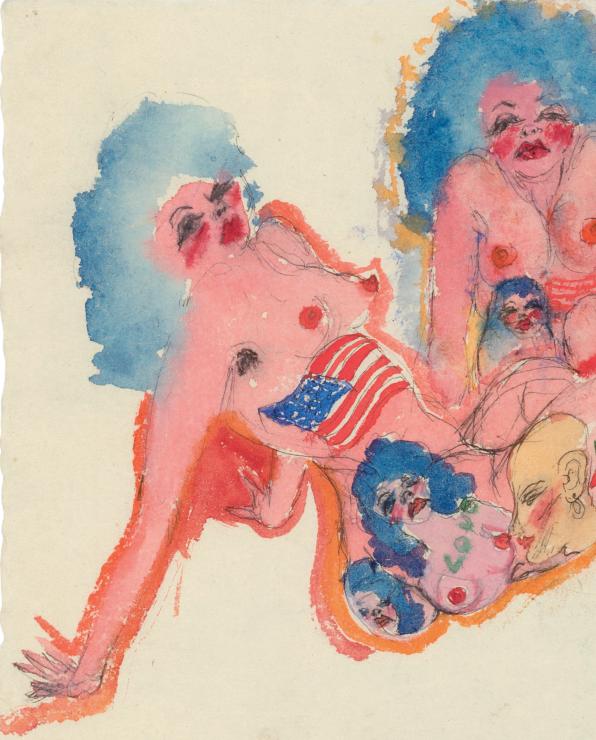

Mrs. America 1962

Ink and watercolor on paper

10 ½ x 7 ¾ inches

Children’s Games Series 1 960

Ink on paper

10 ⅞ x 8 inches

Children’s Games Series 1960

Ink on paper

11 ⅞ x 8 ⅜ inches

Children’s Games Series 1960

Ink on paper 11 x 8 ½ inches

Quintuplets 1964

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

9 ¼ x 12 ½ inches

Elizabeth Taylor Masked 1963

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

9 x 11 ⅞ inches

The Sisters Dream of Battle 1964

Ink and watercolor on rice paper

11 ⅞ x 9 inches

‹ Flesh Wall with Table 1965

O il on canvas

3 p anels

8 0 x 195 inches overall

Flesh Wall with Window 1966 ›

Acrylic and pencil on canvas 85 x 141 inches

Education

1956 B.S., Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY

1955–56 School of General Studies, Columbia University, New York, NY

1954 New York University, New York, NY

1954–56 Michael Loew (Studio classes)

1949–51 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Select Solo Exhibitions

1960 Reuben Gallery, New York, NY

1961 Judson Gallery, New York, NY

1964 OK Harris, Provincetown, MA

1966 Byron Gallery, New York, NY

1973 Artists Space, New York, NY

1974 Evanston Art Center, Evanston, IL

1975 Wilson College, Chambersburg, PA

1982 Rutgers University, Douglass Library, NJ

1984 Women’s Interart Center, New York, NY

A.I.R. Gallery, New York, NY

1986 SOHO20 Gallery, New York, NY

1987 Atelier 2000, Vienna, Austria

Galerie Carinthia, Klagenfurt, Austria

1988 SOHO20 Gallery, New York, NY

1991 SOHO20 Gallery, New York, NY

Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland

1992 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland

1996 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland

1998 Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden

1999 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland

Galleri Hovet, Gamla Ishovet, Stockholm, Sweden

2000 Medborgarhuset, Smedstorp, Sweden

2001 Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden

2002 Galleri Strömbom, Uppsala, Sweden

2003 Konstpaus, Ekerö, Sweden

2004 Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland

Galleri Cupido, Stockholm, Sweden

2007 Villa Landes, Kimito, Finland

SARKA Museum, Loimaa, Finland

BE’19, Helsinki, Finland

2008 SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2009 Piteå Konsthall, Piteå, Sweden

2014 Artifact Gallery, New York, NY

Select Group Exhibitions

1961 New Forms, New Media , Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, NY

1964 Figure Show, Wadsworth Atheneum, CT

1965 Box Show, Byron Gallery, New York, NY

11 from the Reuben , Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

1972 Humor, Satire, and Irony, New School Art Center, New York, NY

1973 Women Choose Women , NY Cultural Center, New York, NY

JB Cobb, Martha Edelheit, Ree Morton , Artists Space, New York, NY

Erotica Show, New School Art Center, New York, NY

Erotic Garden , Women’s Interart Center, New York, NY

1975 Sons and Others , Queens Museum, Queens, NY

Three Centuries of the American Nude , New York Cultural Center, New York, NY

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, MN

Campbell Gallery, University of Houston, TX

Works on Paper, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

1978 The Sister Chapel , P.S.1, Long Island City, New York

1979 The Sister Chapel , State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY

1984 BLAM! Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Artist Space, New York, NY

1996 Helsinki Art Hall, Helsinki, Finland

1997 Konst Massan , Galleri BE’19, Sollentuna, Sweden

Member Artists Group Show, SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2004 SELF_ISH , Kazuko Gallery, New York, NY

2005 FallOut , SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

Small Works , SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2006 Self Portraits, Ideas, Images, Structures , SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2009 INPLACE: The Annual Exhibition of SOHO20 Artists , SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2010 Between the Lines: Exhibition of SOHO20 Member Artists , SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2011 Folles d’Hiver, SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

Cluster–A Group Exhibition: Object and Space (Alexis Duque, Martha Nilsson Edelheit, Peter Janssen), AG Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

Groundbreaking: The Women of the Sylvia Sleigh Collection , Rowan University Art Gallery, Glassboro, NJ

Affordable Art Fair, New York, NY

2012 Art in Boxes 2012 , AG Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Always/Never, SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2013 Relational Ground: Defying the Status Quo , SOHO20

Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2014 From the Other Side , SOHO20 Chelsea Gallery, New York, NY

2016 Annual Group Exhibition: Part 2 , SOHO20, Brooklyn, NY

The Sister Chapel: An Essential Feminist Collaboration , Rowan University Art Gallery, Glassboro, NJ

2017 Annual Group Exhibition , SOHO20, Brooklyn, NY

Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 , Grey Gallery, New York University, New York, NY

2018 Currents: Abortion , A.I.R. Gallery, New York, NY

Eric Firestone Gallery, New York, NY

Films

1973 The Albino Queen and Sno White in Triplicate , Super 8, 22 min. Petzel Gallery, New York, NY Camino Real , 16mm, 3min.

1975 Sno-White (Crimson), 16mm, 7min.

1977 Hats, Bottles, & Bones: A Portrait of Sari Dienes, 16mm, 22 min. Selected screenings from 1977 to 2017 at Albright Knox Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Anthology FIlm Archives, New York, NY; Brooklyn Museum, NY; Graz Museum, Austria; Grey Art Gallery, New York University, NY; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Museum of the City of New York, NY; Portland Museum, OR; University of California, San Diego, CA

Selected Writings

Martha Edelheit, “Georgia O’Keeffe: A Reminiscence,” Painters on Paintings , August 6, 2015, https://painterson paintings.com/ martha-edelheit-on-georgia-okeeffe-a-reminiscence/

Martha Edelheit, “Georgia O’Keeffe: A Reminiscence,” Women Artists Newsletter 3 , no. 6 (December 1977): 3, 8–9.

Martha Edelheit, “Some Thoughts about My Work and My Self,” in Art: A Woman’s Sensibility, ed. Miriam Schapiro (Valencia: California Institute of the Arts, Feminist Art Program, 1975): 19.

Martha Edelheit, “The Loves of Rosa Bonheur” (1976, unpublished), lecture presented at College Art Association, Chicago, IL, Jan. 1976; Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, MD, Oct. 1976; A.I.R. Gallery, New York, NY, Nov. 1976.

Exhibition Catalogues

Martha Nilsson Edelheit: Erotic Circus , Artifact Gallery, New York, NY, 2014 Essay: Rachel Middleman

Martha Nilsson Edelheit , Konsthallen Piteå, Sweden, 2009 Essays: “Grannens flock med Gotlandsår” by Christian Chambert and “Martha Nilsson Edelheit in Sweden” by Andrew D. Hottle

Martha Nilsson Edelheit , Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland, 2007 Essay: “Martha Nilsson Edelheit’s Vibrant Pastures” by Andrew D. Hottle

Martha Nilsson Edelheit , Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, 2000 Essay: Sara Lidman

Martha Nilsson Edelheit , Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland, 1999 Essay: Bengt af Klintberg

Martha Nilsson Edelheit: Paintings and Drawings, 1988–1998 , Heland Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, 1998

Martha Nilsson Edelheit , Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland, 1996 Essay: “Between Heaven and Earth: About Weightlessness in Martha Edelheit’s Pictorial World” by Ragnar von Holten

Martha Ross Edelheit: String Masks and Paintings , Galleria BE’19, Helsinki, Finland, 1996 Essay: “Masks of Beauty and Despair” by Leena-Maija Rossi

Selected Bilbiography

Rachel Middleman. Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018): 64–88. Jennifer Krasinski, “Exploring New York’s Century Boom of Artist-Run Galleries,” Village Voice , February 28, 2017, https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/02/28/exploring-newyorks-midcentury-boom-of-artist-run-galleries/ MARTHA NI

Blake Gopnik, “Martha Edelheit, Another Postwar Talent Left Out of Art History’s Storyline,” Opinion, Artnet News , February 1, 2017, https://news.artnet.com/opinion/martha-edelheitgreygallery-840995

Ariella Budick, “When Artists Ruled: The Fearless Spirit of 1950s and 60s New York,” Financial Times , Visual Arts, January 13, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/0de70c44-d750-11e6944be7eb37a6aa8e

Holland Cotter, “When Artists Ran the Show: ‘Inventing Downtown,’ at N.Y.U., New York Times , January 12, 2017, https://www. nytimes.com/2017/01/12/arts/design/when-artists-rantheshow-inventing-downtown-at-nyu.html

Melissa Rachleff, Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 (New York: Grey Art Gallery, New York University, 2017).

Andrew D. Hottle, The Art of the Sister Chapel: Exemplary Women, Visionary Creators, and Feminist Collaboration (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2014).

Rachel Middleman, “A Feminist Avant-Garde: Martha Edelheit’s ‘Erotic Art’ in the 1960s, Konsthistorisk tijdskrift/Journal of Art History (2014): 1–19.

Joyce Kozloff, “Maria Lassnig in New York, 1968–1980,” Hyperallergic , November 8, 2014.

Gail Levin, “Censorship, Politics and Sexual Imagery in the Work of Jewish–American Feminist Artists,” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues 14 (Fall 2007): 63–96.

Richard Meyer, “Hard Targets: Male Bodies, Feminist Art, and the Force of Censorship in the 1970s,” in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution , ed. Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 362–383.

Joan Arbeiter, “Chance and Change in the Art of Sari Dienes,” Woman’s Art Journal 7, no. 2 (Autumn 1986–Winter 1987): 27–31.

Grace Glueck, “Artist and Model: Why a Rich Tradition Endures,” New York Times , June 8, 1986.

Barbara Haskell and John G. Hanhardt, Blam! The Explosion of Pop, Minimalism, and Performance, 1958–1964 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1984).

Eunice Golden and Kay Kenny, “Sexuality in Art: Two Decades from a Feminist Perspective,” Woman’s Art Journal 3, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 1982): 14–15.

Joan Semmel and April Kingsley, “Sexual Imagery in Women’s Art,” Woman’s Art Journal 1, no. 1 (Spring–Summer 1980): 1–6.

Sandra L. Langer, “The Sister Chapel: Towards a Feminist Iconography, with Commentary by Ilise Greenstein,” Southern Quarterly 17, no. 2 (Winter 1979): 28–41.

Judith E. Stein, “Women Artists ’78,” Art Journal 37, no. 4 (Summer 1978): 332–333.

Gloria Feman Orenstein, “The Sister Chapel: A Traveling Homage to Heroines,” Womanart 1, no. 3 (Winter/Spring 1977): 12–21.

Judith K. Brodsky, “Notes from the Women’s Caucus for Art,” Art Journal 35, no. 4 (Summer 1976): 396–398.

Tiiu Lukk, “Profiles,” Super-8 Filmaker 3, no. 5 (October 1975): 46.

Lynda Crawford, “Sitting on Botticelli’s Face,” Bitch 1, no. 2 (March 1974): 8–9, 23.

Peter Frank, “On Art,” Soho Weekly News , December 13, 1973.

Maryse Holder, “Another Cuntree: At Last, a Mainstream Female Art Movement,” Off Our Backs 3, no. 10 (September 1973): 11–17.

Donald B. Kuspit, et al., “The 61st Annual Meeting of the College Art Association of America,” Art Journal 32, no. 3 (Spring 1973): 271–283.

Rosemary Mayer, “Martha Edelheit,” Reviews: New York, Arts Magazine 47, no. 6 (April 1973): 75.

Jane Gollin, “Martha Edelheit,” Reviews and Previews, Art News 65, no. 4 (April 1966): 15.

Colta Feller, “Martha Edelheit,” In the Galleries, Arts Magazines 40, no. 10 (June 1966): 49.

Awards

1984 2nd Prize, Juried Invitational, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA

1978–86 NYSCA Grant, The New York State Council on the Arts, New York NY

1974–77 NYSCA and NEA Matching Grants, The New York State Council on the Arts, New York NY and the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, DC

Select Public Collections

New York Public Library, New York, NY

Piteå Commune, Piteå, Sweden

Rowan University Art Gallery, Glassboro, NJ

Teaching

1980 Montclair State College, Montclair, NJ (Guest Lecturer–Film)

1977 New School, New York, NY (Guest Lecturer–Film)

1976 Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Artist in Residence)

1975 University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH (Artist in Residence)

1975 Wilson College, Chambersburg, PA (Artist in Residence)

1973 California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA (Visiting Artist)

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

MARTHA EDELHEIT

Flesh Walls: Tales from the 60s

October 17–December 15, 2018 on view at Eric Firestone Gallery

4 Great Jones Street, New York, NY

ISBN 978-0-9844715-5-3

Cover: Flesh Wall with Table, 1965, detail (see p. 64)

Publication copyright © 2018 Eric FIrestone Press Essay copyright © 2018 Melissa Rachleff

All artwork © Martha Edelheit

Reproduction of contents prohibited All rights reserved

Published by Eric Firestone Press

4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937

Eric Firestone Gallery

4 Great Jones Street, 4th floor New York, NY 10012 917-324-3386

4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937 631-406-2386

ericfirestonegallery.com

Principal: Eric Firestone

Director of Research: Jennifer Samet

Project Management: Kara Winters

Design: Russell Hassell, New York

Printing: Puritan Capital, New Hampshire