Essays

Moving On Up: The Rebels Are Too Busy Spraying It Not Saying It

Sacha Jenkins

For forever, New York City has been a haven for individuals looking to make their mark in society. And for some, New York City was the place where you could make your mark on society. Immigrants from the Old Country. Runaway slaves looking to make it in a “new” country. Gangsters, politicians, hustlers—all cut from the same cloth, all shaped from the same gingerbread man mold. Back then, some walked the streets with axes and machetes. Today, a quiet box cutter living in a back pack isn’t a shocking gesture. Some carried billy clubs, some still do today but it is a secondary tool of discipline. Seems like cops are quick to shoot you if you’re seemingly unstable and quick with the mouth. Quick to taze you with shocking volts of electricity. New York has always been unpredictable, and that remains true today, even with scores of gentrifier zombies running through the ‘hood, looking for a good latte fortified by a very particular brand of oat milk.

When Henry Chalfant moved to New York City in the early 1970s, he was a sculptor. An artist with a point of view, with influences that helped to inform his own expression. He hails from a small town that lives in the shadows of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—a rust belt city whose own collective belt has been snapped in half via American greed and general shortsightedness. Once on the streets of the Big Apple, Chalfant began to notice the handwriting on the walls. It was different from the political graffiti that was popular during that time, i.e. turns of phrase like OFF THE PIGS! Puerto Rico Libre! and Fuck The Draft! Names would appear over and over again—in spray paint and magic marker. Seemingly primitive tools that were employed by teenagers and some dare-devil pre-teens even. The names often appeared with numbers affixed to them. What did it mean? Who was responsible for it? Last but not least, WHY???!

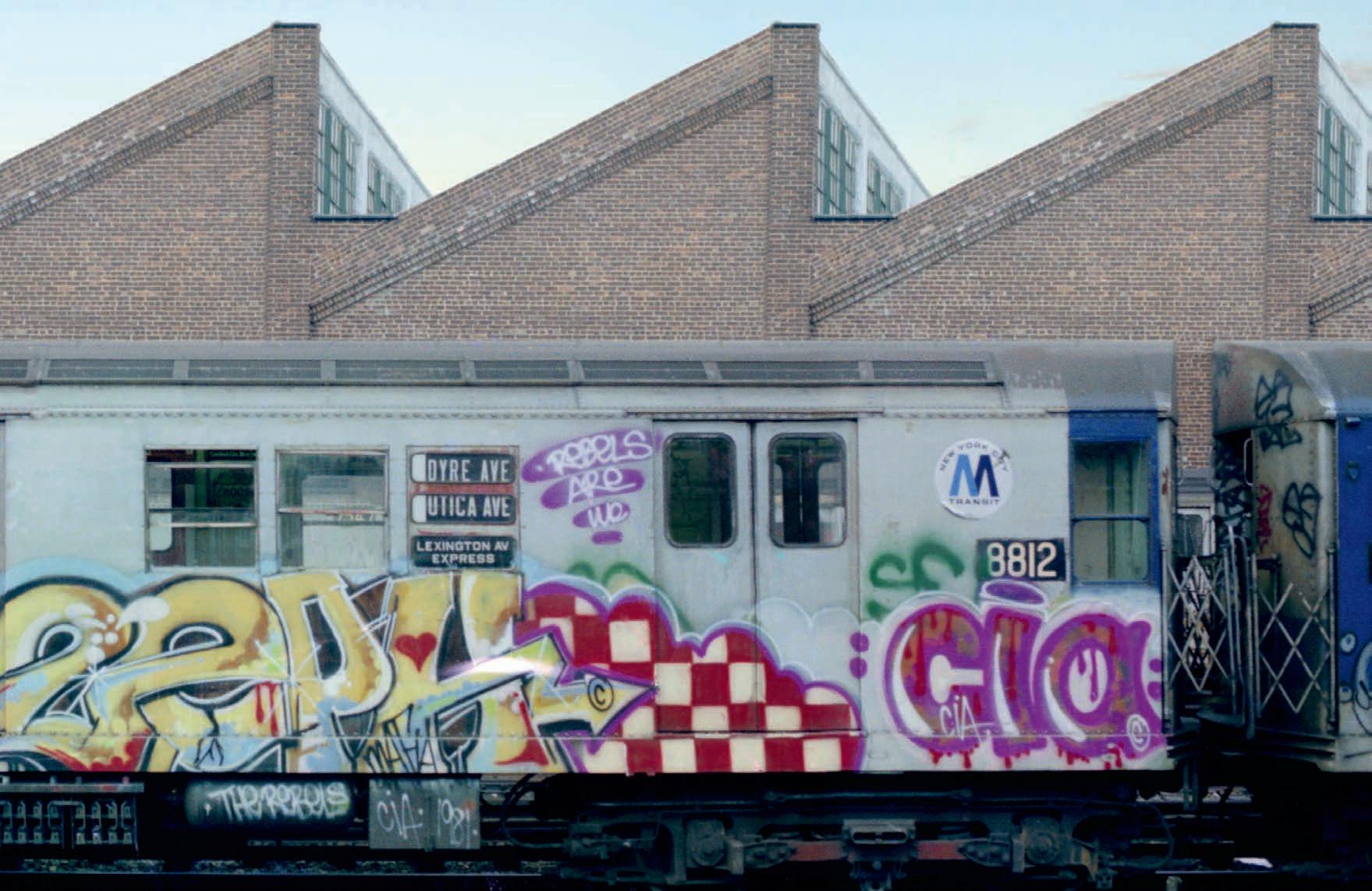

Chalfant would pick up a camera and document what he saw on the streets and on subway cars and busses. What he saw was a reflection of, and reaction to, the environment itself. Typically, outsiders who stumble upon, and are astute enough to recognize a “folk” culture want to come in and dictate where things should go and how it all should move. Henry, however, was more interested in being a fly on the wall and a student of the form. As an artist, he understood that the language these kids parlayed was high art in and of itself. Chalfant was mesmerized by the tools of choice (magic markers and spray paint) and knocked out by the surface of choice: a wild, runaway canvas that straphangers clung onto as they rode to work.

Before the information superhighway changed the way the world at large communicated, Henry Chalfant recognized that the youth of New York City were utilizing psychedelic drawings that moved to communicate ideas amongst one another. Painting trains was also a sport—competition was fierce, and it helped to inspire the “writers” to one up one another. Once the signatures flooded the insides of the train cars, the names floated onto the exteriors of the mammoths; when there was no room left there was no real option outside of painting the entire damn car. Name up there in big bright lights. Henry wasn’t looking to change what he saw in the outer boroughs and beyond. He was out to observe and preserve. He would go on missions by himself, anonymously snapping his photos. He knew no one in the community.

Eventually he would meet Mare 139 and Kel 1st, two Puerto Rican writers from the South Bronx who happened to be brothers. They would encourage other writers to meet the older white dude who wasn’t a cop, who took great photos of their work. The only other white people some of these youths had contact with were police officers and school teachers–two relationships where the power dynamic builds on a narrative of “supremacy”. Henry leveled the playing field. He was a fan, a supporter, a cultivator. A sympathizer. A friend.

Henry would open his studio in SoHo to the young writers of New York City. He initially used the space to craft his massive sculptures, so attendees would bare witness thick chains and various pulley systems. But the main attraction was his portfolios. Photographs of burners beautifully mounted on durable black matte sheets that were handled with the thump of a jackhammer. People of that era were accustomed to flipping through family photo albums. Writers were like WuTang Clan—a self made, self-governed body of wild misfits who had the gift of gab and a way with words. Flipping through Henry’s portfolios was a spectacle to witness.

Spirited disagreements might go down—“I was the first to do this. That dude is a toy!” (Toy being a euphemism for an inexperienced writer). Still, Kings got together made plans at Henry’s. Mapped out who would paint what where and when. There were no cell phones involved so you had to be a young man or young woman of your word. Show up when you’re supposed to. Even foes kept it chill at Henry’s. The place was a safe haven. The high ceilings of this industrial work space made you feel like a small giant. In this environment the artists had the opportunity to study contemporary works. A still study of contemporary works. It is nearly impossible to get the full effect of a subway painting when it is on the go, moving people to and fro. One might argue that the study that went down at Henry’s studio helped to advance the form.

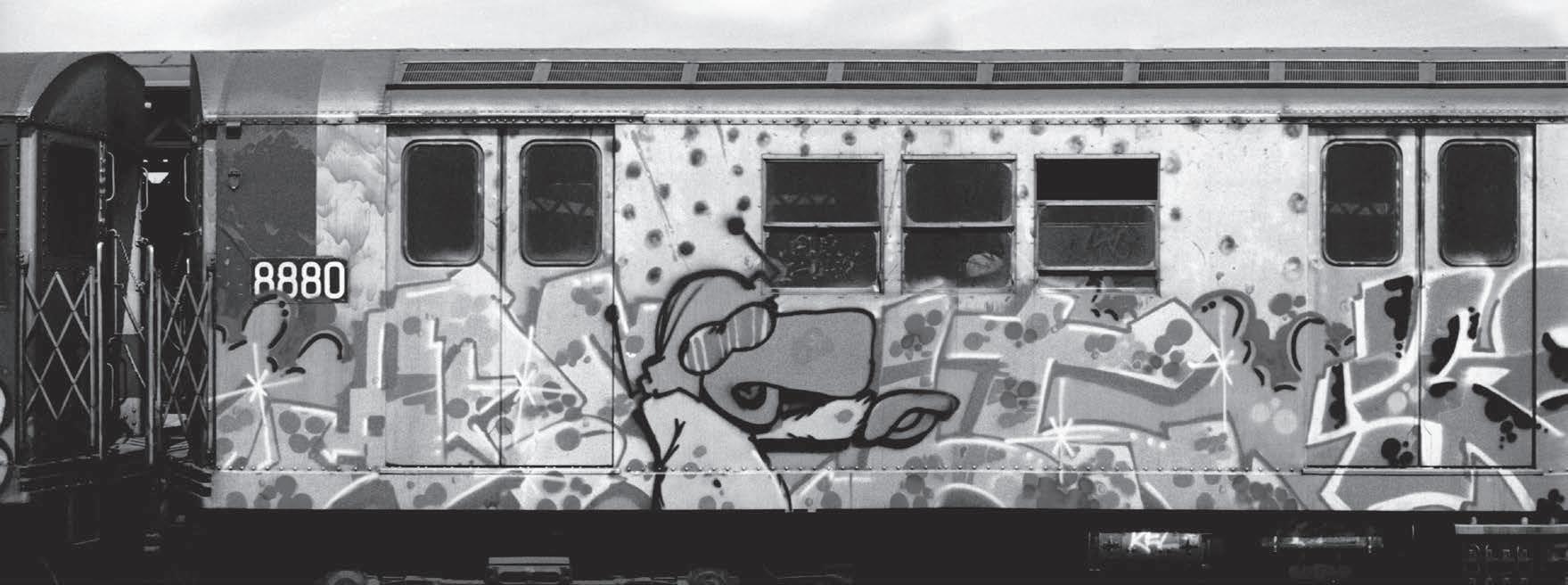

It should be noted that Henry—while in the process of trying to do the art justice– engineered an innovation in the realm of photography. Writers would document their works with the cameras that they borrowed from their moms and aunties. Those were typically of the 110 variety–110 being a somewhat primitive format that too often produced grainy, blurry, subpar images. These untrained photographers were essentially snatching snapshots—gathering images that basically said I was here, I did this. You were able to get a sense of what it was but really what you often saw was a detail-less blob.

Henry understood that the devil was in the details. It was the blues... and the yellows and greens and reds and the arrows and sharp lines and the white highlights and the drips and imperfections and the dirt and rust—everything that made the work human, Henry knew it was important to see it in an effort to feel it. He was an educated artist who understood the importance of art history. And anthropology. The people, places and things that had a hand in making it. Henry was interested in it all.

It wasn’t about an outsider assigning a value or defining the aesthetics of writing culture. Henry knew that there was a movement happening; a stampede of ideas and emotions was coming through like the number 2 express. He didn’t get in the way. The kids decided what was superior, what was inferior. Some of it

would be obvious to anyone who was a fan of art. But there’s a language baked into the words that one has to be seasoned and schooled to truly appreciate. Henry became fluent in the language. He was able to decipher what was important because he studied with masters.

Henry was well versed on train schedules and often knew where a train he was chasing would end up at the end of the day. So boom: Henry would go to one of his ideal spots for subway photography. He’d bust out the trusty 35mm camera. Get up close to the masterpiece in question, find the optimal position. From this vantage point it was impossible to capture an entire train. Once he snapped his photo from the optimal vantage point he would slide over x amount of feet to the right and snap again. He would repeat this process until he was able to capture the whole car. From there, once the photos were developed he would splice it all together and boom, there you had it. A photo with details so crispy you could feel the raised paint splats on the image.

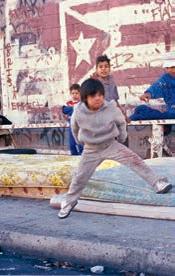

Henry’s camera eye also sees early hip hop culture fully realized—the bboys and break dancers, the deejays and emcees, the kids performing acrobatic stunts on pissy mattresses. He snapped it because it was fantastic. There weren’t too many people like him traveling through the South Bronx with cameras. It was great that he did what he did. Because folks in the community are often so wrapped up in what they’re doing that they don’t always see the marvel in what they’re doing.

Here he is again, rolling around Uptown, trying to catch up with trains. Only this time, the man doesn’t have to break a sweat: the trains Henry used to dart behind now have a place to live for a spell via this magnificent Art vs. Transit exhibition at the Bronx Museum. There isn’t a more fitting venue for such a deliciously Technicolor homecoming. The art created by kids in this very neighborhood has gone on to electrify the world; the electricityfortified third rail that continues to power every subway car in New York City has gone on to metaphorically charge writers with the spirit in every corner of the globe. Henry Chalfant’s work—by way of the classic tome Subway Art (with Martha Copper) and the seminal documentary film Style Wars (with Tony Silver) – would baptize apostles living in every knook of this formerly green marble.

Funny thing is, there was a time when graffiti was considered to be a black eye on any community. Nowadays, graffiti murals often signify “success” and upward mobility. Some bloodthirsty developers see it as a tool to further gentrification efforts. The South Bronx isn’t immune to said practice. However, the Bronx Museum’s willingness to give these raw, pure, original subway paintings a mainstream, institutional look is a major breakthrough and achievement that should be acknowledged. Artists like Dondi and Kel First and Crash and Sharp and Lady Pink and Daze and Futura and Dez and T Kid and Part and Noc 167 and Revolt didn’t paint trains because they wanted a deal on a condo adjacent to the projects. No way Jose.

Welcome to Art vs. Transit : an exhibition that conjures up the magic Henry Chalfant encountered long ago, in a New York land far, far away. Welcome back to a past that has had a heavy hand in how we see the future.

Moving On Up: The Rebels Are Too Busy Spraying It Not Saying It (ES)

Sacha Jenkins

Desde siempre, la Ciudad de Nueva York ha sido refugio de individuos que buscan dejar huella en la sociedad. Y para algunos, la ciudad era el lugar en donde podías dejar tu huella en la sociedad. Inmigrantes del Viejo Mundo, esclavos fugitivos que buscaban crear una “nueva” nación. Pandilleros, políticos, oportunistas—todos cortados con el mismo patrón, todos salidos del mismo molde. Por entonces, algunos caminaban por las calles con hachas y machetes. Hoy en día, una navaja para cortar cartón guardada dentro de una mochila ya no sorprende a nadie. Algunos llevaban porras, igual que algunos las llevan hoy en día como herramienta antidisturbios, parece que la policía es rápida en dispararnos si aparentamos inestabilidad o tenemos la lengua muy suelta; es rápida en neutralizarte con voltios de electricidad. Nueva York siempre ha sido impredecible. Y aún lo sigue siendo, pese a las cantidades de zombies gentrificados que corren por sus “barrios” en busca de un buen “latte fuerte” con una marca muy particular de leche de avena.

Cuando Henry Chalfant se mudó a la ciudad de Nueva York a principios de los años 70, era escultor. Un artista con un punto de vista, con influencias que le ayudaron a articular su propia expresión. Vino de un pueblo pequeño a la sombra de Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—una ciudad con un cinturón de óxido partido a la mitad por la codicia americana y la miopía generalizada. Una vez en las calles de la Gran Manzana, la caligrafía pintada en las paredes llamó poderosamente la atención de Chalfant. Era diferente al graffiti político popular en esa época con frases como: “FUERA LOS CERDOS!” “Puerto Rico Libre!” “A La Mierda el Reclutamiento!”

Algunos nombres aparecían una y otra vez en pintura de aerosol y marcadores de tinta. Estas herramientas, aparentemente primitivas, eran empleadas por adolescentes y hasta alguno que otro temerario pre-adolescente. Los nombres aparecían acompañados regularmente por números. ¿Qué significaban? ¿Quiénes eran los responsables? Y por último, pero no menos importante, ¿¿¿POR QUÉ???!

Chalfant tomaría su cámara y documentaría lo que vio en las calles, autobuses, y vagones del metro. Lo que vio fue un reflejo y una reacción al entorno mismo. Típicamente, cuando un forastero se topa con un elemento “folk” de cultura local y es suficientemente astuto como para reconocerlo, pretende involucrarse y dictar el orden y ritmo de las cosas. Henry, por el contrario, estaba más interesado en ser una mosca en la pared y ser un investigador de este sujeto estético. Como artista, comprendió que el lenguaje que estos chicos usaban de manera tan informal era una manifestación de las bellas artes y una obra de arte en sí. Chalfant quedó cautivado por la selección de herramientas (rotuladores y aerosoles) y hechizado por el soporte preferido: un forajido lienzo salvaje del que los usuarios del transporte público se colgaban camino para sus trabajos.

Antes de que la super-autopista de la información cambiara la manera en que se comunicaba el mundo, Henry Chalfant identificó la singular manera en que los jóvenes de la ciudad de Nueva York se comunicaban unos con otros a través de un repertorio de ideas utilizando dibujos psicodélicos en movimiento. Pintar trenes también era un deporte. La competencia era feroz y eso inspiró a los “escritores” a tratar de destacarse de entre los demás. Una vez que las

firmas inundaban las superficies del interior de los vagones, los nombres flotaban en los exteriores de estos mamuts; cuando se agotaba el espacio, no había más opción que pintar “todo el maldito vagón.” Los nombres aparecían por todo lo alto iluminados por luces brillantes.

Henry no aspiraba a cambiar lo que vió en los barrios de la periferia y más allá. Buscaba más bien observar y preservar. Organizaba misiones individuales y anónimamente tomaba fotografías. No conocía a nadie en la comunidad. Eventualmente, conoció a Mare 139 y Kel First, dos hermanos escritores puertorriqueños del South Bronx. Ellos alentaban a otros escritores a conocer al “viejo blanco” que no era policía, y que tomaba excelentes fotografías de sus obras. Las únicas personas blancas que algunos de estos jóvenes conocían eran policías o maestros. En ambas relaciones, la dinámica del poder se basaba en el discurso de “supremacía.” Henry niveló la cancha del juego. Él era un fan, un partidario, un cultivador. Un simpatizante. Un amigo.

Henry abrió su estudio en SoHo a los jóvenes artistas de la ciudad de Nueva York. Inicialmente utilizaba el espacio para crear sus masivas piezas entre gruesas cadenas y poleas. Pero la atracción principal eran sus portafolios. Fotografías finamente montadas en duraderas viñetas negras mate que eran manipuladas con el golpe sonoro de un martillo neumático. En ese entonces las personas estaban acostumbradas a ojear los álbumes de fotos familiares. Entre ellos se encontraban escritores como WuTang Clan—un grupo autodidacta y autónomo dirigido por un cuerpo de inadaptados salvajes con el don de usar ingeniosamente las palabras. Voltear las páginas de los portafolios de Henry era un espectáculo de admirar.

Agitadas discusiones se resumían en—“Yo fui el primero en hacer esto.” “Ese tipo es es un ‘toy’!” (Ser un ‘toy’ era un eufemismo que se refería a un escritor sin experiencia). Al final, los reyes se reunían en el estudio de Henry a hacer planes. Se asignaba quién pintaría qué, dónde, y cuándo. No existían los móviles así que tenías que ser una persona de palabra y llegar puntualmente. Hasta los rivales se mantenían en paz donde Henry. El lugar era un refugio. La doble altura de los techos industriales del espacio te hacía sentir como un pequeño gigante. En este entorno los artistas tuvieron la oportunidad de analizar obras contemporáneas. Era un estudio con piezas inmóviles, lo que permitía observarlas con detenimiento. Era prácticamente imposible recrear el efecto completo de un vagón pintado si estaba en movimiento transportando pasajeros. Podríamos argumentar que el ejercicio que ocurrió en el estudio de Henry fue clave en el desarrollo de esta forma de arte.

Cabe recalcar que Henry, en el proceso de reivindicar esta forma de arte, diseñó un mecanismo innovador en el campo de la fotografía. Los artistas hasta entonces solamente podían documentar sus obras con cámaras prestadas de sus familiares. Estos equipos, usualmente de formato 110 eran algo rudimentarios, produciendo imágenes borrosas, con granos, y de baja calidad. Estos fotógrafos sin entrenamiento estaban prácticamente tomando fotos sencillas para poder decir “estaba allí, yo hice esto.” Las imágenes solo proporcionaban una idea aproximada de la obra, pero generalmente lo que se observaba era una mancha sin detalles.

Henry sabía que la clave estaba en los detalles. Estaba en los azules… los amarillos, los verdes y los rojos, las flechas y líneas rectas, los detalles resaltados en blanco, las gotas chorreadas y las imperfecciones, la suciedad y el óxido, todo lo que humanizaba la obra. Henry sabía que era importante verla haciendo al mismo tiempo un esfuerzo por sentirla. Como artista instruido, comprendía la importancia de la Historia del Arte y la Antropología. Valoraba a las personas, los lugares, y los objetos creados por la mano del hombre. A Henry le interesaba todo.

Henry no era un agente externo asignando valor o definiendo la estética de la cultura del graffiti. Sabía que existía un movimiento en marcha, una estampida de ideas y emociones que se sentía venir con la fuerza y la velocidad de los expresos de la línea 2. No se interpuso. Los jóvenes fueron quienes decidieron qué calificaba como superior, y qué como inferior. Algunas apreciaciones son obvias para cualquiera que aprecia el arte. Sin embargo, hay un significado forjado en el lenguaje que se aprende a través de la experiencia o la instrucción para poder realmente apreciar esta manifestación. Henry se familiarizó con este sistema de significados al punto de dominarlo. Era capaz de descifrar lo esencial ya que había estudiado con los grandes maestros.

Henry conocía bien el horario de los trenes y a menudo sabía de antemano dónde terminaba el tren que perseguía al final del día. Y así, boom!: Henry se acercaba a alguno de sus puestos ideales para fotografiar el metro. Preparaba su confiable cámara de 35mm. Se acercaba a la obra maestra y decidía el ángulo óptimo para fotografiarla. Era imposible encuadrar un tren completo desde este punto. Una vez que tomaba su foto desde el mejor ángulo se desplazaba unos pies a la derecha y volvía a disparar. Repetía este proceso hasta que capturaba todo el vagón. De aquí, posteriormente revelaba las fotos, volvía a ensamblar la composición y boom! Ahí lo tenemos. Una imagen de alta resolución con detalles tan ricos que se podían palpar las leves protuberancias que resultaban de las salpicaduras de pintura.

El objetivo de Henry también observó la cultura hip hop ya plenamente articulada en su época más temprana—los bboys y los break dancers, los deejays y emcees, los muchachos haciendo acrobacias sobre colchones usados. Lo fotografió porque todo era fantástico. No había muchos como él atravesando el South Bronx con cámaras. Fue grandioso que lo hiciera porque los chicos de la comunidad habitualmente están tan involucrados en lo que hacen que no siempre ven las maravillas de lo que están haciendo. Aquí está de vuelta Henry por Uptown tratando de alcanzar un tren. Pero esta vez no necesita esforzarse: como por arte de magia los trenes que perseguía ahora tienen una residencia por medio de esta magnífica exposición Art vs. Transit en el Museo de El Bronx. No existe un mejor lugar para esta bienvenida en Technicolor. El arte creado por estos muchachos en esta misma comunidad ha electrificado al mundo; metafóricamente hablando, el tercer riel cargado de electricidad que suministra de energía a cada vagón del tren ha descargado su energía en los artistas alrededor del mundo. La labor de Henry Chalfant a través de su clásico volumen Subway Art (con Martha Copper)

junto a su obra documental Style Wars (con Tony Silver), ha bautizado apóstoles en cada rincón de esta pequeña canica anteriormente verde.

Lo gracioso es que hubo un tiempo en el que el graffiti era considerado el ojo morado de cualquier comunidad. Hoy en día, los murales de graffiti simbolizan “éxito” y movilidad social. Algunos empresarios ambiciosos lo ven como una herramienta para extender sus programas de gentrificación. El South Bronx no es inmune ante esta práctica. Sin embargo, la voluntad del Museo de El Bronx de dar una visión institucional y académica a estas obras originales pintadas en el metro en su estado puro, constituye un avance y un significativo punto de partida dignos de reconocimiento. Artistas como Dondi, Kel First, Crash, Sharp Lady Pink, Daze, Futura, Dez, T Kid, Part, Noc 167 y Revolt no pintaron a cambio de una oferta de copropiedad cerca de los edificios multifamiliares. “No way José.”

Bienvenidos a Art vs. Transit : una exposición que conjura la magia que Henry Chalfant encontró hace mucho, mucho, tiempo en un lugar muy, muy, lejano de Nueva York. Bienvenidos a un pasado que ha dejado un sólido legado en la manera en que vemos el futuro.

16 Blocks and 40 Years, From the Writers Bench to the Bronx Museum Sharp

The South Bronx is the spiritual home of the urban art diaspora, commonly referred to as graffiti art. 149th Street and Grand Concourse Avenue: the place where writers congregated on bench trains and shared stories. It is contextual that the Bronx Museum will host the retrospective of Monsieur Henry Chalfant. Many of the founding members of the culture call the Bronx home.

Mr. Chalfant, born into a family whose origins call from Pittsburgh, would become an unlikely protagonist in the history of New York. Just prior to Monsieur Chalfant’s decision to marry himself to the game, the first generation of writers would exhibit their works on canvas at the Razor gallery in New York. This would set the stage for the evolution of the Urban Art Diaspora’s cultural ascension.

Mr. Chalfant arrived in New York City in the mid-1970s. He hit the ground running, acquired a studio in SoHo and began to sculpt art. As he explored the city of Nueva York, a chance encounter with a painted subway car, the infamous Lee Quiñones “Christmas” train, changed his destiny. He immediately descended upon the train tracks to photograph this masterpiece. At risk of getting hit by a train, his desire to document the culture would supersede concerns for safety. This singular moment would change the course of Mr. Chalfant’s creative direction. At this moment, Mr. Chalfant outstretched his hand and got married to the game. Perhaps the kaleidoscope of colors released endorphins in his brain. There are euphoria blood vessels flowing in the brain, the soul of the viewer enveloped by the visual stimulation of a whole car. This retrospective shall encompass the entire body of work pertaining to the subway trains. Many are familiar with the photos of subway cars. Mr. Chalfant has exhibited his work globally, in France, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, and Asia. The book Subway Art is often referred to as a bible of sorts. Imagery of the culture disseminated globally would help spawn the worldwide movement. Over the years in talking to my extended family, I have heard and witnessed Henry’s philanthropic support of the protagonists of the movement. It is important to note that a subculture of children created perhaps the only true American art form. Pop Art reflects aspects of modern popular American culture. But the precursor is French minimalism. Warhol’s influence has its origins in the work of Duchamp. Two hundred or less prepubescent children coming from socio-economic depravity built this movement, with little to no formal art training. The majority of the spray paint was shoplifted or occasionally acquired through methods police refer to as Bee and E, or breaking and entering.

Henry dedicated his life to documenting this culture. His art studio became a meeting place. Take One from Rock Steady Crew often opted to hang in Henry’s studio, rather than attend school. Our parents did not approve of our clandestine maneuvers into the subterranean world of New York. The ethics of our parents were in direct conflict to bylaws of our lifestyle: Shoplifting in the day to illuminate the night. Henry’s vision was that of a pioneer. He saw the artistic, creative value in our art, when our parents and teachers were restricted by the puritanical approach to life. It was Henry who showed us by power of example that we had intrinsic value to ourselves and to our culture.

Take One introduced Henry to the world of B-boying. Henry organized the first performance of B-boying; the encounter between the downtown scene and the kids from the Upper West Side would be monumental. In the immortal words of Grandmaster Flash, “I don’t care who does it better, faster or whatever. First is forever.” Henry may not have been the first person to photograph the movement (we will give this title to Jack Stewart) but inadvertently, Henry’s contribution to the evolution of B-boying is an aspect of his vision that is often overlooked. Just as Henry answered the call to greatness when he started documenting painted subway cars, he knew that the dancing done by these young suns of the ghetto was a cultural phenomenon.

This was the first time the Young Sunz of the ghetto were compensated for the dancing and it planted the seed that there was the possibility to dance commercially as a profession. Henry facilitated Rock Steady Crew’s creativity by placing them in a context where they battled Dynamic Rockers at Lincoln Center and traveled outside of the city to perform at a Pete Seeger concert in upstate New York.

Within the lexicon of urban ideology, there are truths to be held selfevident. To be of the culture, one must paint, Deejay, dance, or rhyme on the mic. The individual who documents culture can be seen as a voyeur. Henry long ago established himself as a part of the essence. When I was 16 or 17 years old, Henry invited me to his studio to speak to a visiting class of Columbia College students. I had never spoken publicly about my creative process. He encouraged us, he gave value to our art by his tireless efforts to document the trains.

After painting trains, we would call his studio and leave messages in the middle of the night. Communicating the train line info, as well as which side of the train was painted was important, as some trains did a 360 degree turn when it arrived at the end of the line and some did not. To catch a photograph of a car, one could spend anywhere from two to six hours on a platform. Henry made us better photographers by creating the multi-photo platform shot, using the yellow line on the platform to help maintain your distance when capturing imagery from the opposite subway platform.

In the last 36 years, I have developed a relationship with Henry outside of the context of the art world or the Hip Hop movement. I am a friend of his. Having said that, this body of the work in the Bronx Museum is a homecoming of sorts. The Boogie Down is where all of the aspects of our history coalesce.

As writing on the trains eventually would have been lost for eternity, as our movement is ephemeral, it is obvious that New York history would have been forgotten had it not been for his commitment of thousands of hours standing on a platform over the course of several years. Henry was there at the ground level. I have traveled the world for the last 35 years participating in the evolution of the Italian and French hip-hop movements. All European writers were inspired to create as a result of subway art.

Subway Art is the most shoplifted book in the history of book publishing; that statement in and of itself speaks volumes. Outside of the print photography realm, Mr. Chalfant has many documentary films that will be on display during

the course of this exhibit. From Mambo to Hip-Hop explores the Latin connection of New York salsa to the culture. Flyin’ Cut Sleeves charts the history of New York gang culture and the eventual transformation of New York gangs, i.e. Black Spades Savage Skulls into crews like the Ex Vandals, the Rebels and the Ebony Dukes.

Like Legend Ruler King The Swing Swing, like Case 2 says, I’m the inventor, wisdom is the best thing to have, I’m the king of style, also known as Lord Supreme Justice Universal Allah. Technique, Case explains to the generation that came after, “One day you might have style that is better than mine.” Case believed in 2011 that he was already 100 years beyond his time. I submit to the reader that when Henry Chalfant married the game in 1976-1977, he was one hundred years beyond his time.

From subway lines to work on canvases, the artwork of the movement is in the permanent collection of museums in America and Europe, private foundations in Japan. The trains did not survive for posterity but our artwork in institutions shall invariably last long after we transition like legend Ruler King. Henry Chalfant influenced the children of this culture, who would ultimately change art history. We the writers of Nueva York, we salute you. Aqui en el Museo Del Bronx.

16 Cuadras y 40 Años, Desde La Banca de los Escritores Hasta el Museo de el Bronx (ES)

Sharp

El South Bronx es el centro espiritual de la Urban Art Diaspora, comúnmente conocida como el arte del graffiti. La calle 149 y Grand Concourse Avenue es el lugar en donde los escritores se congregaban en los bancos de los trenes a compartir sus anécdotas. Dentro de este marco contextual, el Museo de El Bronx será el anfitrión de la retrospectiva dedicada a la obra de Henry Chalfant. Muchos de los miembros fundadores de esta corriente conocemos El Bronx como nuestro hogar.

Chalfant, nació en una familia de Pittsburgh para luego convertirse en un singular protagonista en la historia de Nueva York. Justo antes de tomar la decisión de comprometerse con el juego, la primera generación de escritores exhibía sus obras sobre lienzos en el Razor Gallery en Nueva York, estableciendo las bases para el ascenso cultural de la Urban Art Diaspora.

Chalfant llegó a la Ciudad de Nueva York a mediados de 1970. En breve, consiguió un estudio en SoHo, y comenzó a esculpir obras. Mientras exploraba la ciudad, un encuentro fortuito con un vagón del metro intervenido— el infame “tren de Navidad de Lee Quiñones”—cambió su destino.

Inmediatamente bajó al nivel de los rieles del tren para fotografiar esta obra maestra. Corriendo el riesgo de ser atropellado, su deseo de documentar la cultura fue más fuerte que la preocupación por su propia seguridad. Este poderoso momento cambió el sentido de la dirección creativa de Chalfant. En ese instante, Chalfant extendió su mano y se comprometió con el juego. Quizás el caleidoscopio de colores hizo que su cerebro segregara endorfinas. Existen vasos sanguíneos que irrigan el cerebro asociados a la euforia que sobrecoge el alma de quienes contemplan el estímulo visual de un vagón pintado por completo. Esta retrospectiva abarca la obra completa relacionada a la temática de los trenes subterráneos del metro. Muchos conocen las imágenes de los vagones. Chalfant ha exhibido su trabajo alrededor del mundo en lugares como Francia, Italia, España, el Reino Unido y Asia. El libro Subway Art es reconocido como una especie de Biblia. Las imágenes de esta cultura diseminadas internacionalmente colaboraron en la creación de un movimiento mundial. Conversando con mi familia a lo largo de los años, he escuchado y he sido testigo de las ayudas benéficas con las cuales Henry ha apoyado a los protagonistas del movimiento.

Es importante resaltar que quizás el único estilo artístico verdaderamente estadounidense haya sido creado por la subcultura joven de la población. El Arte Pop refleja algunos aspectos de la cultura popular moderna norteamericana. Sin embargo, su precursor fue el minimalismo francés. La influencia de Warhol tiene su origen en la obra de Duchamp. Cerca de doscientos jóvenes provenientes de segmentos socio-económicos degradados forjaron este movimiento con poca o ninguna instrucción artística formal. La mayoría de las latas de pintura en aerosol eran robadas u ocasionalmente sustraídas mediante métodos conocidos por la policía como B & E (breaking & entering) o entrada forzada.

Henry dedicó su vida a la documentación de este movimiento cultural. Convirtió su estudio en lugar de reuniones. Take One, perteneciente a la agrupación Rock Steady Crew prefería estar en el estudio de Henry en lugar

de ir al colegio. Nuestros padres desaprobaban nuestras maniobras clandestinas en el mundo subterráneo de Nueva York. La ética de nuestros padres estaba en conflicto directo con los reglamentos de nuestro estilo de vida: sustraer artículos de las tiendas durante el día e iluminar durante la noche. La visión de Henry era la de un pionero. Descubrió el valor artístico y creativo de nuestro arte mientras nuestros padres y maestros nos restringían con filosofías puritanas de la vida. Fue Henry quien nos enseñó con su ejemplo, que poseíamos un valor individual y cultural intrínseco.

Take One introdujo a Henry al mundo del B-boying. Henry organizó el primer espectáculo de B-boying: el encuentro entre los miembros de la escena del Downtown y los muchachos del Upper West Side, fue monumental. En las inmortales palabras de Grandmaster Flash: “No me importa quién lo haga mejor, más rápido, o lo que sea. El primero es para siempre.” Henry pudo no haber sido la primera persona en fotografiar el movimiento (le otorgamos ese título a Jack Stewart) pero su contribución involuntaria al desarrollo del B-boying es un aspecto de su visión que en muchas ocasiones ha sido observada solo superficialmente. Cuando Henry fue reconocido por documentar las obras de los vagones del metro, ya sabía que la danza practicada por estas jóvenes estrellas del ghetto era un fenómeno cultural.

Era la primera vez que Young Sunz del ghetto era remunerado por bailar y eso plantó la semilla de la posibilidad de hacerlo profesionalmente. Henry le abrió las puertas a la creatividad del Rock Steady Crew enfrentándolos en un duelo a los Dynamic Rockers en el Lincoln Center y luego viajando fuera de la ciudad para presentarse en un concierto de Pete Seeger al norte del estado de Nueva York.

En la jerga de ideología urbana, algunas verdades caen por su propio peso. Para pertenecer al gremio cultural había que pintar, pinchar discos, bailar, o hacer rima frente a un micrófono. El individuo que se dedicaba tan solo a documentar la actividad cultural podía ser etiquetado de voyerista. Henry sin embargo, se estableció hace ya mucho tiempo como parte de su esencia.

Cuando tenía 16 o 17 años, Henry me invitó a su estudio para que hablara frente a los estudiantes de su clase de Columbia College. Nunca había hablado en público acerca de mi proceso creativo. Él nos motivaba, le daba valor a nuestro arte a través de sus incansables esfuerzos por documentar los trenes.

Después de pintar un vagón, llamábamos a su estudio y dejábamos un mensaje en la mitad de la noche. Le compartíamos la información sobre la línea a la que pertenecía el vagón, y qué lado del vagón intervenido era el importante, ya que algunos trenes hacían un giro de 360 grados al llegar al final de su línea y otros no. Capturar la imagen de un vagón podía tomar de dos a seis horas de espera en un andén. Henry nos hizo mejores fotógrafos al crear su tiro de andén multi-cuadros, utilizando la línea amarilla de la plataforma para mantener la distancia mientras tiraba la foto desde el andén del lado opuesto.

En los últimos 36 años, Henry y yo hemos madurado una relación fuera del contexto del mundo artístico y del movimiento Hip Hop. Soy su amigo. Dicho esto, considero que tener el cuerpo de su obra en el Museo de El Bronx

representa de alguna manera un retorno a casa. Todos los aspectos de nuestra historia se juntan en el Boogie Down.

Como escribir sobre los trenes eventualmente se perdería en la eternidad, ya que nuestro movimiento es efímero, es obvio que la historia de Nueva York sería ineludiblemente olvidada sino fuese por el compromiso de Henry y las miles de horas que dedicó a lo largo de los años a esperar de pie en un andén. Quizás Rock Steady hubiese ascendido a fenómeno mundial junto a Ruza Blue de todas formas. Pero Henry estaba allí desde abajo. He viajado por el mundo por 35 años participando en la evolución del movimiento Hip Hop en Italia y Francia. Los escritores europeos se animaron a crear inspirados por nuestras obras en el subterráneo.

Subway Art es el libro más sustraído de las tiendas en la historia de las publicaciones, este hecho en sí nos dice mucho. Fuera del ámbito de la fotografía impresa, Chalfant tiene muchos documentales que serán mostrados a lo largo de la temporada de la exposición. From Mambo to Hip-Hop explora la conexión latina de la Salsa neoyorquina con la cultura. Flyin’ Cut Sleeves esboza la historia de la cultura pandillera de Nueva York y su transformación. Por ejemplo, como los Black Spades Savage Skulls se transformaron en agrupaciones como los Ex Vandals, los Rebels, y los Ebony Dukes.

Legend Ruler King The Swing Swing, al igual que Case 2 dice, “soy el inventor, la sabiduría es la mejor virtud, soy el rey del estilo, conocido también como Lord Supreme Justice Universal Allah. Technique Case describe la próxima generación. “Algún día quizás, tengas un mejor estilo que yo.” Case creía en 2011 que estaba 100 años adelantado a su tiempo. Pongo a discreción del lector que cuando Henry Chalfant se comprometió con el juego en 1976-1977, también se adelantó a su época por un siglo.

Desde las líneas del subterráneo a los lienzos, las obras del movimiento son parte del acervo de las colecciones de museos en Estados Unidos, Europa, y fundaciones privadas en Japón. Los trenes no quedaron para la posteridad pero nuestras obras conservadas en instituciones indudablemente permanecerán por largo tiempo tras nuestra transición como la leyenda Ruler King. Henry Chalfant influyó en los hijos de esta cultura, cultura que al final cambiaría la historia del arte. Nosotros los escritores de Nueva York, te saludamos desde aquí, en el Museo de El Bronx.

A tribute to the vision of Henry Chalfant

SUSO33

Curator

Madrid, June 1, 2019

1 (Chalfant, 2015)

2 Chalfant majored in classical Greek at Stanford. He became a sculptor in New York City in the 70’s.

3 Henry’s photographs have a documentary character and were shot from the perspective of visual anthropology. Chalfant’s interest in alternative groups can be seen in other projects such as Queer City or Visit Palestine: Ten Days on the West Bank.

4 (Chalfant, 2015)

5 This was the reason behind the birth of La Ilegal (1994), the first store for graffiti artists in Madrid and the first distributor of Montana (the world’s first spray paint brand specialized on graffiti) outside Barcelona. Fanzines were distributed there in the most analog way: photocopies.

“So many wonderful things have happened since the uncertain beginning that consisted in leaving your name written on a train… Urban art has made it very far since graffiti proposed the rebirth of public art. Writing your name could have been the original intention, but to say something more than “I am here,” expressing deep wishes and passions, creating beauty, revealing the drama of life, having a political voice, is more difficult, and all that is possible today and it is happening everywhere.” Henry Chalfant.1

Art is Not a Crime 1977–1987 is the first great retrospective dedicated to the work of the photographer and documentary writer Henry Chalfant (United States, 1940), the most important ambassador of graffiti culture in the world. It was exhibited in 2018 in Europe, in Madrid, and for me it is now an honor to present his work in the birthplace of this international cultural movement.

It is hard to imagine a better place than the Bronx Museum to pay homage to the graffiti writers that with the ingenuity of a child, but wanting “to be noticed,” were able to create perhaps Art History’s most recent movement. A cultural wave that could exist and evolve thanks to the circumstances and events that took place in New York during the 70’s and 80’s.

Therefore, we have decided to include along with the exhibit that will be shown in Europe, a new space, specifically conceived for the Bronx Museum. Also, due to this reinterpretation of the first project, the show’s name has evolved and extended into: Art vs. Transit 1977–1987

The exhibit is born as a tribute to Henry and the first writers, recognizing the value of their legacy: graffiti as an artistic movement, which has transformed the urban landscape and contemporary culture in recent decades.

Henry is not a traditional artist and I am not a conventional curator. The drive behind the organization of this exhibit is the debt that many graffiti writers feel towards Henry for the influence that his work had in our lives. Henry made universal a culture that many young people embraced and adopted.

This project celebrates the 35th anniversary of the debut of his mythical documentary Style Wars and the release of the book Subway Art, which allowed hip-hop culture and the graffiti painted on the subway cars to be known around the world. Both changed forever the way to understand, experiment, and relate to the art of the city.

Henry’s approach to this culture is not academic, but anthropological and artistic, and it was always based on his own experiences. I have set the tone of the exhibit from this triple perspective, to which I have added my own knowledge and experience.

The careful assessment of this valuable photographic archive allows us to think about intercultural exchanges, immigration, and the enormous contributions of Latino and African American culture to global history, and a way to create “as a community.”

Subway Art and Style Wars

When analyzing Henry Chalfant’s work it is necessary to reference two milestones that transformed graffiti culture: the book Subway Art (1983–1984),

written by Henry with Martha Cooper, and the film Style Wars (1983), with director Tony Silver.

Subway Art is considered “the holy book of graffiti.” It not only documented the images of this new artistic expression and its protagonists, but also served as the movement’s manual of style, disseminating its poetry and visual language.

I started doing graffiti in the mid 80’s, when I was just 11 years old (in the tradition of beginning in childhood) when the movement was still evolving in Europe, before the boom it would enjoy in the following decade. Back then, nobody in my social circle knew about Subway Art nor Style Wars. That changed in 1987, when the documentary Style Wars was aired. I remember vividly the transformation I underwent the day after I saw the film that changed the course of my life and the lives of many of my colleagues. The documentary said that each writer had “his own arrow,” and we also wanted to have ours. I was not the only one to receive this impact and “illumination.” Style Wars, together with Subway Art, launched New York graffiti to the global arena.

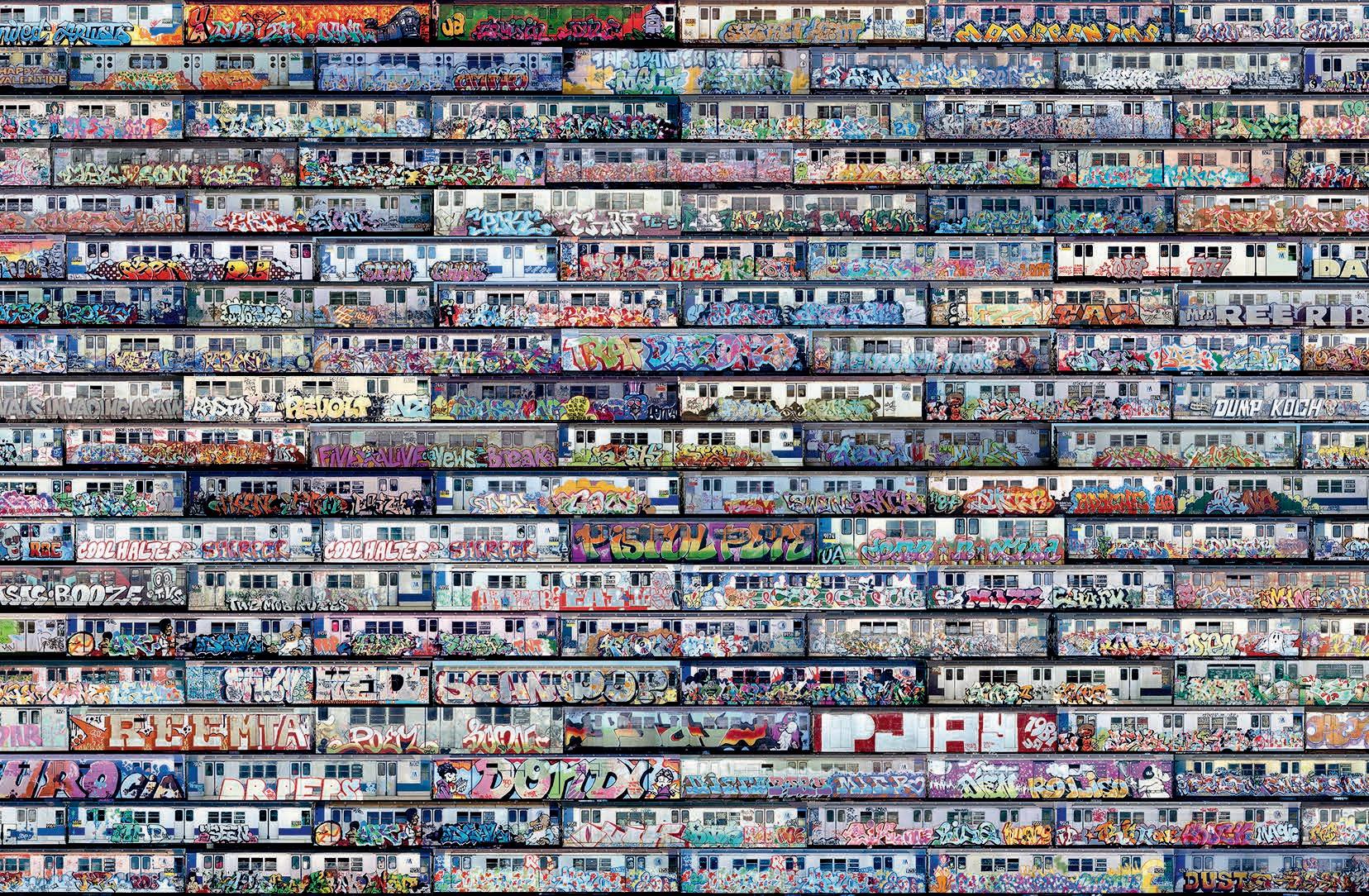

An exceptional photographic archive

Chalfant’s photographic archive is unique. With a collection of more than 800 photographs of painted subway cars and a few hundred more shots from an anthropological perspective, it constitutes the largest documentary archive of this ephemeral art form on the subway wagons and the people who painted them.

On his metro rides from home to his studio, the young sculptor Henry Chalfant noticed that something magical was unfolding before his eyes and decided to photograph it. He even built his own artifacts, which allowed him to shoot the complete train. I believe that various elements came together triggering Henry’s interest to discover who were behind the painted fonts that circulated around the city on the subway cars. Perhaps his interest on kinetic art or in open-air installations came together with his knowledge of calligraphy (he was trained as a philologist, specialized in classical Greek).2 His political commitment with the cause of civil rights, his attentive and empathetic personality with people in need, were key in turning Henry Chalfant in “the chosen one,” with the ability to see, feel, and transmit this culture to the world.

In a way, they were “kinetic paintings,” with sound and motion that appeared and disappeared in public space in a brief time of exposure under continuous lighting changes.

Diffusion and expansion

Since then, Henry travelled extensively to present his research and to understand firsthand and in rigorous manner the phenomenon’s creative expansion. He promoted it as an art form and shared his investigation first through Subway Art and Style Wars, and later with Spraycan Art (1987), together with Jim Prigoff, documenting its expansion at a global level.. In fact, he was one of the first to participate in talks and round tables around the world. (He visited Spain a number of times, Lee came with him in 1985).

This interest in the social dimension3 of graffiti is crucial in understanding that the art form is more than painting: it involves a life style and a sensibility from the margins. Everything around the act of painting is what makes graffiti special. The game, the competition, the social critique, the desire to be better… it all came together. It was a way to discover the world and feel part of it while painting.

Quality, quantity and “time of exposure”

Chalfant’s panoramic photos, made possible through a system he invented, are the best documents of the abundance and quality of the works that circulated in New York subway cars during those years. The trains had a brief and fleeting time of exposure. They disappeared from the station and would not return in less than three hours, making it difficult to appreciate the details of the works painted on them, making them even more enigmatic. People did not understand the visual noise created by the amount of signatures and works that decorated the trains from top to bottom and inside out. The intrigue to learn the identity of these artists grew. These first writers were actually embellishing a degraded city. Henry has narrated emotionally how the writers added color to a gray city: “In New York, graffiti writers grew up in the subway system, challenging a powerful urban environment of 600 miles of steel and machinery that ran through the city like blood vessels, echoing through tunnels and roaring on the elevated tracks that extended kilometer after kilometer above the debris zones of what used to be occupied apartment buildings in the past. The kids would scream out loud: “We are here and we will not be ignored,” lustering a destroyed city, while they transformed these ruins into magnificent canvases.”4 In this environment of novelty and fugacity, the writers did not have the means to document their works and Henry’s photographs helped them pin up details and learn the styles. In my biography, I agree with Henry in the importance of broadcasting5 and the necessity to transfer knowledge. I had the luck to have participated in many talks and round tables with him, which established the framework of our friendship.

“Telegraffiti” and “conditioners”

Henry Chalfant’s activity pioneered in what I call “telegraffiti.” In the present, urban art and the highly prolific “new muralism” cannot be understood without photography nor the diffusion on social media. Before the digital era, when nobody had a pocket camera, Henry made graffiti travel through time and space by means of photography and television. That was a great change. Moreover, as a good researcher, Henry blended in with graffiti writers and shared their environmental conditions: day, night, time of exposure... Very different conditions from the work in a studio. Mistakes are evidenced on the street. There are no intermediaries. Graffiti is a way to be in life, very useful in developing a rigorous methodology: make drafts, plan, “organize missions”6… Believe in it. Have faith.

An immersive exhibit

In order to assess the archive of Henry’s work, we need to consider different parameters: size, quality, quantity, and time of exposure.7 Attempts to transmit this idea have resulted in immersive exhibit designs that reproduce life-size photos of the trains under different types of illumination, including a space with sound effects that evoke the emotional situations around the act of painting graffiti.8

Another installation has been designed, Henry’s Gaze, a selection of photographs of the writers of these works, their social circle, and their role in the construction of the hip-hop movement. Henry shared time with them for decades. It is a selection of almost 300 photographs shot from an anthropological view, most of them never published before (including the ones from his visit to Europe in 1985).

The exhibit caters to different publics through the eyes and the body. The audience not acquainted with graffiti can identify, understand, and feel perhaps for the first time, some of the expressions that coexisted with them on the street every day. The ones familiarized with the movement would enjoy the winks, details, and relics prepared for the occasion: life-size photographs of mythical trains, unedited archival material, hand-written notes, and other objects and fetishes.

“Graffiti’s sacred book:” Subway Art, played a predominant symbolic role exhibited inside a case mounted above an Ionian column,9 next to the book’s original dummy especially brought for the occasion.

Henry's legacy

Besides being the writers’ confidant, they dedicated trains to him and gave him sketches in exchange for his photographs, Henry had an important cultural influence on these kids who had no formal education. Without him, they would have not approached art. Henry opened the door for creation for them. Many of us walked into a museum for the first time to see the photos from his book. Some cropped the pictures from the volume carving it to the bare spine. His books are simultaneously two of the best-sellers and the most stolen books in the history of art. Henry expressed very well at the door that graffiti meant for many: “The learning experience obtained from writing graffiti on subway trains and urban walls has led many young people to develop careers in graphic design, filmmaking, editorials, photography and fine arts.”10

Thank you, Henry, for being our teacher. Thank you for your dedication when documenting, your generosity when sharing, and your effort in broadcasting.

The enormous city turns small when you see the painted trains circulating. You feel free and you feel part of one big family at the same time. We also learned that from Henry, his photos, his documentaries, and his talks... that graffiti is a form of knowledge that transmits from hand to hand, therefore mentors are key. A lot of culture is needed to understand graffiti.

6 One of the exhibit installations designed having graffiti artists in mind (who would be the only ones able to understand its references and subtleties) is a vintage map of New York’s Metro system. Chess figures (such as pawns and kings) of the same color (the game was played within a single group) stained with paints of many colors were glued on it. The figures were placed in the city’s many areas claiming authority over territories and establishing hierarchies among “the warriors” and “the kings of the line.”

7 Occasionally, I have commented Henry about the metaphor of graffiti as an iceberg. At its submerged base are the many, the real, and the powerful graffiti writers (who underscore the amount of works in quantity and quality). Alongside are some of the renowned names in the art world, such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, who painted a few graffiti works. They are the tip of the iceberg that is identified and labeled in the history of contemporary art.

8 In fact, the idea of this exhibit in honor of Henry Chalfant, comes in part, from my wish to improve the video installation he made with his life-size photographs of subway trains for the 2015 Venice Biennial, including a space with sound, an element that thrilled Henry but it was not possible to get at that moment.

9 The Ionian column makes a symbolic/humoristic reference to the purported classicism that this book represents transformed into a mythical object, as well as to Henry’s relation with classical Greek… Coincidentally, in antiquity, all Greek architecture was painted with bright colors, just like graffiti.

10 (Chalfant, 2015)

Un tributo a la mirada

de Henry Chalfant (ES)

SUSO33

Comisario

En Madrid, el 1 de junio de 2019.

1 Henry Chalfant, «Spray Can Jams». SUSO33 ONe Line. Catálogo de la retrospectiva de SUSO33 en CEART, Fuenlabrada (Madrid), 2015.

2 Chalfant se especializó en Griego Clásico en la Universidad de Stanford. Comenzó como escultor en la ciudad de Nueva York en la década de 1970.

3 Las fotografías de Henry tienen carácter documental y están enfocadas desde la antropología visual. Y este interés de Chalfant por grupos alternativos se percibe en otros proyectos como Queer City o Visit Palestine: Ten Days on the West Bank

4 Henry Chalfant, «Spray Can Jams». SUSO33 ONe Line. Catálogo de la retrospectiva de SUSO33 en CEART, Fuenlabrada (Madrid), 2015.

5 Fue la razón por la que nació La Ilegal (1994), el primer store de escritores de graffiti en Madrid y primer distribuidor de Montana (la primera marca de pintura de spray a nivel mundial especializada en graffiti) fuera de Barcelona. Allí distribuíamos los fanzines de la manera más analógica: en fotocopias.

«Han surgido tantas cosas maravillosas desde ese primer incierto origen que consistió en dejar tu nombre escrito en un tren... El arte urbano ha llegado muy lejos desde que el graffiti se propuso hacer renacer el arte público. Dejar tu nombre puede haber sido el deseo original, pero decir algo más que “yo estoy aquí”, expresando anhelos profundos y pasiones, creando belleza, revelando el drama de la vida, teniendo voz política, es más difícil, y todo eso es hoy posible y está teniendo lugar en todas partes.» Henry Chalfant.1

Art is Not a Crime 1977-1987 es la primera gran retrospectiva dedicada a la labor del fotógrafo y documentalista Henry Chalfant (Estados Unidos, 1940), máximo embajador de la cultura del graffiti en el mundo. Se expuso en 2018 en Europa, en Madrid, y para mí es un honor que se presente ahora en el lugar que vio nacer este movimiento cultural internacional.

Es difícil imaginar un espacio mejor que el Museo de El Bronx para homenajear a los escritores de graffiti, que, con la ingenuidad de unos críos, pero con ganas de “hacerse ver”, fueron capaces de crear quizá el último movimiento artístico de la Historia del Arte. Un movimiento cultural que pudo existir y progresar gracias a las circunstancias y a los hechos que ocurrieron en el NY de los años 70-80.

De ahí que junto a la muestra que presentamos en Europa, tengamos en esta ocasión un espacio nuevo, concebido específicamente para el Museo de El Bronx. Y también debido a esta reinterpretación del primer proyecto, el nombre de la muestra evoluciona y se amplía con: Art vs. Transit 1977-1987. La exposición nace como tributo a los escritores de graffiti de esos años y a Henry, poniendo en valor su legado: un movimiento artístico, el del graffiti, que ha transformado el paisaje urbano y la cultura contemporánea de las últimas décadas.

Ni Henry es un artista tradicional ni yo soy un comisario al uso. El impulso que me ha llevado a organizar esta muestra es la deuda que tantos escritores de graffiti sentimos hacia Henry, por la influencia que su trabajo tuvo en nuestras vidas. Henry universalizó una cultura que muchos jóvenes adoptamos como nuestra.

Este proyecto celebra el 35 aniversario del estreno de su mítico documental Style Wars y de la edición del libro Subway Art, gracias a los cuales el mundo entero conoció la existencia del graffiti sobre vagones de metro y de la cultura hip-hop. Ambos cambiaron para siempre la forma de entender, experimentar y relacionarnos con el arte en la ciudad.

Hay que destacar que el acercamiento de Henry a esta cultura no es académico, sino antropológico y artístico, y siempre estuvo basado en sus propias experiencias. Desde esta triple perspectiva, a la que añado mis conocimientos y vivencias, he trabajado el tono de la muestra.

La observación atenta de este valioso archivo fotográfico nos permite reflexionar sobre la interculturalidad o los movimientos migratorios y la enorme aportación de la cultura Afroamericana y Latina a la historia universal de la cultura, y una manera de crear “en comunidad.”

Subway Art y Style Wars

Hablar de la labor de Henry Chalfant obliga a citar dos hitos que transformaron la cultura del graffiti: el libro Subway Art (1983-1984), realizado por Henry junto a Martha Cooper, y la película Style Wars (1983), junto al director Tony Silver. Subway Art está considerado «el libro sagrado del graffiti», y tiene la peculiaridad de que no sólo recopiló las imágenes de esta nueva expresión artística y de sus protagonistas: también funcionó como un verdadero manual de estilo del movimiento y dio difusión de su poética e imaginario. En mi caso, empecé a hacer graffiti a mediados de los 80, con tan sólo 11 años (en la tradición original de empezar de niño), en el momento de gestación del movimiento en Europa, anterior al boom que el graffiti experimentaría en la década siguiente. Por entonces, nadie de mi entorno conocía ni Subway Art ni Style Wars. Pero eso cambió en 1987, se emitía el documental Style Wars. Recuerdo perfectamente la transformación que sufrí el día después de ver la película, que cambió el rumbo de mi vida y la de muchos de mis colegas. El documental decía que cada escritor tenía «su propia flecha,» y nosotros también quisimos tener la nuestra. No fui el único que recibí este impacto e «iluminación.» Style Wars, junto con Subway Art, permitieron la expansión a nivel mundial del movimiento del graffiti que había surgido en Nueva York.

Un archivo fotográfico excepcional

El archivo fotográfico de Henry Chalfant es único en el mundo. Con una colección de más de 800 fotografías de trenes intervenidos y otros cientos con un enfoque antropológico, es el mayor archivo documental de esta forma de arte efímero sobre vagones de metro y de quienes los pintaban.

En sus trayectos de metro de casa al estudio, el joven escultor Henry Chalfant supo ver que algo mágico estaba ocurriendo ante sus ojos y decidió fotografiarlo, e incluso se construyó sus propios artefactos fotográficos para lograr capturar los trenes completos. Intuyo que varios factores se unieron para despertar en Henry este interés por descubrir quiénes estaban detrás de esas letras y pintadas que circulaban en los vagones atravesando la ciudad. Quizá su interés por la escultura en movimiento y por los ambientes instalativos en espacios abiertos, unido a su conocimiento de la caligrafía (su formación es de filólogo, especializado en Griego Clásico2 ), más su compromiso político con la lucha de los derechos civiles y una personalidad empática y atenta a las personas más desfavorecidas fueron las claves para convertir a Henry Chalfant en «el elegido» para ver, sentir y transmitir esta cultura al mundo.

De alguna manera, se trataba de «pinturas cinéticas», sonoras y en movimiento, que aparecían y desaparecían en un breve tiempo de exposición en el espacio público y sometidas a un continuo cambio de iluminación.

Difusión y expansión

Hay que destacar que Henry a partir de ese momento no paró de viajar para presentar sus investigaciones y captar de primera mano y de forma rigurosa la expansión creativa del fenómeno. Lo promovió como arte y compartió su investigación mediante Subway Art y Style Wars, primero, y después con Spraycan Art (1987) junto a Jim Prigoff, que documentaba la expansión a nivel mundial.

Incluso fue uno de los primeros en tomar parte en charlas y mesas redondas por todo el mundo. (Hizo numerosas visitas a España, incluyendo su visita con Lee en el año 1985.)

Ese interés en la dimensión social3 del arte del graffiti es crucial para entender que el graffiti no consiste sólo en pintar: implica una forma de vivir y de sentir desde los márgenes. Todo lo que rodeaba al acto de pintar es lo que hace el graffiti especial. El juego, la competición, la crítica social, las ganas de superación… se entremezclaban. Era una forma de descubrir el mundo y de sentirse parte de él pintando..

Calidad, cantidad y «tiempo de exposición»

Las fotografías panorámicas de Chalfant, gracias a un sistema que él mismo desarrolló, son el mejor documento que tenemos de la abundancia y de la calidad de trenes que circulaban por Nueva York en aquellos años. Esos trenes tenían un breve y fugaz tiempo de exposición. Desaparecían de la estación y no solían volver a pasar hasta pasadas tres horas, lo que dificultaba apreciar los detalles de las piezas en ellos pintadas, haciéndolas aún más enigmáticas. La gente no entendía el ruido visual que suponía la cantidad de firmas y de piezas que decoraban los trenes de arriba abajo, de adentro afuera. Y crecía la intriga por saber quiénes eran los autores de estas intervenciones. En realidad, estos primeros escritores estaban embelleciendo una ciudad degradada. Henry ha narrado con emoción cómo los escritores aportaron color a una ciudad gris: «En Nueva York, los escritores de graffiti se formaron en la red de metro, donde desafiaron a un poderoso entorno urbano de 600 millas de acero y maquinaria que atravesaba como un vaso sanguíneo la ciudad, resonando por los túneles y retumbando en un metro “elevado” que recorría kilómetros y kilómetros de zonas de escombros en las que en épocas pasadas se levantaban edificios de apartamentos. Los chicos gritaban: “Estamos aquí, no seremos ignorados”, haciendo brillar a una ciudad destruida, convirtiendo esas ruinas de subsistencia en magníficos lienzos».4 En ese ambiente de novedad y fugacidad, los escritores no tenían medios profesionales para documentar sus piezas y las fotografías de Henry les ayudaron a fijar los detalles y a aprender los estilos. En mi biografía, coincido con Henry en esta valoración de la difusión y en la necesidad de transmitir el conocimiento. Y he tenido la suerte de participar en muchas charlas y mesas redondas junto a él, surgiendo en ese marco nuestra amistad.

«Telegraffiti» y «condicionantes»

La actividad de Henry Chalfant es pionera de lo que denomino «telegraffiti.»

En la actualidad, el arte urbano y el tan prolífico «nuevo muralismo» no se entienden sin la fotografía y sin la difusión5 en las redes sociales. El graffiti, en la época analógica, cuando no todo el mundo tenía un capturador de imágenes en el bolsillo, gracias a Henry viajó en el espacio y en el tiempo a través de la fotografía y de la televisión. Eso representó el gran cambio. Además, como buen estudioso de su objeto de estudio, Henry se mimetizaba con los escritores de graffiti y compartía sus condicionantes: el día, la noche, el tiempo de exposición... Situaciones muy distintas a las del trabajo en estudio. En la calle se evidencian los errores. No hay intermediarios. El graffiti es una manera de

estar en la vida, muy útil para desarrollar una dura metodología: hacer bocetos, planificar, «planear misiones»…6 creer en ello. Tener fe.

Una muestra inmersiva

Para acercarse al archivo de obra de Henry hay que valorar diferentes parámetros: el tamaño físico a proporción humana, la calidad, la cantidad y el tiempo de exposición7. Esto se ha intentado transmitir optando por un diseño de exposición inmersivo que reproduce las fotografías de trenes a tamaño real con distintas ambientaciones lumínicas, incluyendo un espacio sonoro, evocador de las situaciones emocionales que implica hacer graffiti.8

También se ha diseñado la instalación La Mirada de Henry, una selección de fotografías de los escritores que realizaron estas piezas y de los que les rodeaban en la construcción del movimiento hip-hop, con los que Henry ha convivido durante décadas. Se trata de una selección de casi 300 fotos de enfoque antropológico, la mayoría inéditas (incluyendo las correspondientes a sus visitas a Europa en el año 1985).

El recorrido permite deambular con la mirada y con el cuerpo a públicos muy distintos. La audiencia no especializada en graffiti puede identificar, entender y sentir, quizá por primera vez, algunas de las expresiones con las que convive cotidianamente en la calle. Y los conocedores del movimiento disfrutarán los guiños, detalles y reliquias que se han preparado para la ocasión: fotografías a tamaño real de trenes míticos, material de archivo inédito, notas manuscritas, objetos y fetiches.

Cumpliendo un importante papel simbólico, sobre una columna jónica,9 en una urna puede admirarse «el libro sagrado del graffiti»: Subway Art, acompañado por la maqueta del original traída para la ocasión.

El legado de Henry

Además de ser el confidente de los escritores, que le dedicaban trenes y al que regalaban bocetos a cambio de fotos, Henry ejerció gran influencia cultural en estos chicos sin formación que sin él nunca se hubieran acercado al arte. Henry les abrió la puerta a la creación. Muchos de nosotros entramos por primera vez a un museo para ver las fotos de su libro. Algunos, para cortar las fotos hasta que el libro quedó en el esqueleto. Sus libros son dos de los más vendidos, y más robados, de la historia del arte. Henry ha expresado muy bien la puerta que supuso el graffiti para muchos: «El aprendizaje obtenido escribiendo graffiti en trenes y en los muros urbanos ha llevado a muchos jóvenes a desarrollar posteriormente una carrera en diseño gráfico, realización de películas, editoriales, fotografía y bellas artes.»10

Gracias, Henry, por ser un maestro para todos nosotros. Gracias por tu dedicación en documentar, tu generosidad en compartir y tu esfuerzo en difundir.

La inmensa ciudad se hace pequeña cuando ves circular los trenes pintados. Te sientes libre, y a la vez parte de una gran familia ( one big family ). Eso también lo aprendimos de Henry, de sus fotos, de sus documentales, de sus charlas... El graffiti es una forma de conocimiento que se transmite de mano en mano, de ahí que los mentores sean una pieza clave. Hay que tener mucha cultura para entender el graffiti.

6 Una de las piezas expositivas, diseñada pensando en los escritores (son los que podrán entender los matices y alusiones), es un plano del metro de Nueva York de la época. Sobre el plano, se sitúan figuras de ajedrez (peones y reyes), de un solo color (el juego era entre el propio grupo), manchadas con pintura de colores. Estas piezas se extienden por las distintas áreas de la ciudad y compiten por los territorios, marcando jerarquías entre «guerreros» y «los reyes de la línea».

7 En ocasiones he comentado con Henry la metáfora del graffiti como un iceberg en el que en la base sumergida estarían los potentes, numerosos y verdaderos escritores de graffiti (que anotan en cantidad y calidad el número de piezas), y junto a ellos, algunos nombres conocidos por el mundo del arte como JeanMichel Basquiat y Keith Haring, que habiendo pintado muy poco graffiti, aunque sí street art, son la punta del iceberg que se conoce y se nombra en la historia del arte.

8 De hecho, la idea de esta exposición homenaje a Henry Chalfant, en parte, surge de mi anhelo por mejorar la videoinstalación que realizó Henry de sus fotografías de trenes a tamaño real en la Bienal de Venecia de 2015, incluyendo esta vez el espacio sonoro, circunstancia que a Henry siempre le hizo mucha ilusión conseguir y en aquella ocasión no fue posible.

9 La columna jónica hace una referencia simbólico/humorística al clasicismo que supone este libro, convertido en pieza mítica; así como a la relación de Henry con la lengua griega antigua… Curiosamente, toda la arquitectura griega se pintaba en la Antigüedad con llamativos colores, igual que el graffiti.

10 Henry Chalfant, «Spray Can Jams». SUSO33 ONe Line. Catálogo de la retrospectiva de SUSO33 en CEART, Fuenlabrada (Madrid), 2015.

Seeing Us Being Us—

Through the Lens of Henry Chalfant

Carlos Mare

If my mind serves me, my first impressions of Henry may have been to ask if he was a cop, or why was this middle aged white man taking photos of our trains and what were his intentions with all the history he was recording?

My brother Kel met him first sometime around 1980 and befriended him, a bit suspiciously but he began to entrust him with friends and family and introduce him across our writing crews which included Cos 207, Shy 147, Dondi, Duro, Crash, Kase2, and other Style Masters of the era. We had heard of his large archive and portfolios filled with 35mm photographs of our painted whole car trains that were stitched together to capture its entirety. This became an Ah Ha moment for us! No one among us had the photography skills or innovation to document trains this way. At the time we were using the readily available 126, 110 or disc format cameras to document our trains, which were of poor image and paper quality.

This was his first influence on us: he gave us a mirror, a snapshot not just of our paintings but to our history and self analysis. He taught us the value of documenting and archiving. If we were to start there and understand the deeper implications of this, the consideration and commitment he took to recognize the movement.

While many of us considered ourselves artistic we were inherently criminal minded in order to make our art. The environment necessitated it and promoted it in every aspect of our governed life. He didn’t judge our sidewinding mischief instead he learned the code of the streets and continued to archive us, contextualize us as the potential avant-garde of our time during a period of high innovation and production on NYCs streets and trains.

His interest was partly influenced by both his artistic practice as a stone and marble sculptor and love of anthropology and art history. This would come to influence many of us to be more reflective of our efforts and what values it would carry over time and generations as chronicled in Henry's photo portfolios.

There was a sense of urgency in his archive which was in full display. Graffiti, like ghetto life, fades and weathers into the ether without much notice.

At the studio we would stop by the studio to claw through the archives or give him advance notice of productions, often times he would be on his own missions to photograph, many times writers would call him on the Henry hotline.

But it wasn’t just trains, he met me when I was a part of Rock Steady Crew the most notorious and famous of Bboy Breaking culture. It was he and Marty Cooper that introduced us to the Downtown scene with the first art and dance shows notably at the Kitchen and his photo show at the Ok Harris Gallery on West Broadway. This would come to be a mutually beneficial relationship over many years both creatively and personally.

Henry would soon introduce us to another ‘White Middle Aged’ man named Tony Silver who later became a close friend, mentor and collaborator. He had approached Henry about a novel idea to document the Graffiti trains. Henry pulled back the curtain to expose a whole generation of artists, painters and dancers, charlatans and misfits alike that make up the NYC Underground scene. Little did we know that Style Wars would change all of our lives and that

it would have a hand in democratizing modern art and culture worldwide. So when I speak of Henry particularly on the first point of affording us a mirror to reflect on our total existence and our conditions and our contributions to society, Style Wars would deeply change the way I looked at myself, my peers and our history, how I thought about it how I would come to investigate and speak of it, how I would challenge all of art history for the vantage of elevated subway tracks.

Most importantly Henry took me and my older brother Juan to the monumental Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1980. It is this show and period in my relationship with Henry where I would become a student of art history, how to articulate myself in relationship to it, moreover how to look at art, how to consider it critically. It was at this show where Guernica had the biggest impact on me as did the early Cubist works and metal sculptures with Julio González. I remember reconstructing my own stories into the works, the agony of war, the complexity of wild style in abstraction. At the time I was a student at the infamous High School of Art and Design where my favorite class was Art History so I had a familiarity with Master Picasso but not at this level and not with someone that could walk me through it.

It is our mutual love of culture and art history that bonded us. This would shape the artist and man I would grow into. In 1984 I took on metal sculpture and pioneered a novel approach and reconstructed it with metal. It was Henry who then would introduce me to some the worlds greatest sculptors: Anthony Caro, David Smith and most importantly Frank Stella in the mid-80s. While visiting his studio in the early 80s we would often go to galleries, one I frequented most was at 420 West Broadway, the Leo Castelli Gallery where I would study artists, notably Stella, Johns, and Rauschenberg. The proximity to so many art galleries near Henry's studio always made the trek from the South Bronx worth it! During this period Henry was moving away from sculpture and deeply committed to his documentation of the Hip-Hop community, so much so he would go to train yards with us to take photos. I managed to take an infamous photo of him painting an F train while played up in the tunnel. He not only observed he participated.

If you add up the impact of his archive, the books Subway Art, 1980, the documentary Style Wars, his lectures and diverse production of social justice films and activism it all adds up to an impactful life on the world around him.

Viéndonos, siendo nosotros, a través de la lente de Henry Chalfant

Carlos Mare

Si no lo recuerdo mal, mi primera impresión de Henry debió ser para preguntar si era un policía, porqué este hombre blanco de mediana edad estaría tomando fotos de nuestros trenes y cuáles serían eran sus intenciones con la historia que recopilaba.

Mi hermano Kel lo conoció en algún momento alrededor de 1980 y se hicieron amigos, con algo de recelo aún confió en presentárselo a la familia y amigos, y también a los “crews” de escritores entre los que se encontraban Cos 207, Shy 147, Dondi, Duro, Cash, Kase2, y otros “Style Masters” de la época. Habíamos oído hablar de su gran archivo compuesto de portafolios cargados de fotografías de nuestros vagones de trenes pintados, pegados uno junto a otro para capturar la imagen completa. ¡Este fue un momento revelador para nosotros! Ninguno de nosotros tenía la habilidad de fotografiar o la tecnología para documentar los trenes de esta manera. Hasta entonces utilizábamos para fotografiar nuestros trenes, las cámaras de formato 126, 110, o las de formato de disco disponibles, que eran de baja resolución y calidad de impresión.

Esta fue la primera influencia que tuvo en nosotros, nos proporcionó un espejo, un pantallazo no sólo de nuestras pinturas si no también de nuestra historia, además de un auto-análisis. Nos enseñó el valor de documentar y archivar.

Ahí comenzamos a comprender las implicaciones más profundas de este ejercicio, y el respeto y compromiso con los cuales Henry reconoció el movimiento.

Mientras algunos de nosotros nos considerábamos artistas, nuestra metodología para hacer arte era básicamente de corte delictivo. El ambiente lo requería y lo promovía en cada aspecto que gobernaba nuestras vidas. Él no nos juzgó por nuestras travesuras, por el contrario aprendió la ley de las calles, continuó archivando nuestro trabajo y lo contextualizó considerándolo como el potencial “avant-garde” de nuestra era durante un período de mucha innovación y producción en los trenes y calles de Nueva York.

Su interés estaba parcialmente influenciado por su práctica artística como escultor de piedra y mármol y su amor por la Antropología y la Historia del Arte. Esto tuvo mucho impacto sobre nosotros y nos hizo ser más reflexivos en nuestros esfuerzos y pensar en los valores que nuestro trabajo mantendría a través del tiempo y las generaciones, como en las crónicas fotográficas de los portafolios de Henry. Había un palpable sentido de urgencia completamente expuesto en su archivo. El graffiti como la vida en el ghetto, se deteriora y desvanece en el éter sin dejar muchos rastros.

En su estudio podíamos estudiar los archivos y le dábamos las primicias de nuevas producciones. Frecuentemente se encontraba en sus propias misiones para fotografiar obras. Otros escritores lo llamaban por teléfono a su “línea caliente”. No se trataba sólo de los trenes, lo conocí siendo yo miembro del Rock Steady Crew, la agrupación más famosa de la cultura Break y Bboy. Él y Marti Cooper nos presentaron a la escena del Downton con los primeros espectáculos de arte y danza en The Kitchen y con su exhibición fotográfica en Ok Harris Gallery en West Broadway. Se convirtió en una relación mutuamente beneficiosa a nivel personal y creativo durante muchos años.

Henry pronto nos presentaría a otro “blanco de mediana edad” llamado Tony Silver, quien también pasó a ser un buen amigo, mentor, y colaborador. Se le acercó a Henry con una idea innovadora de documentar el graffiti de los trenes. Henry abrió el telón y le presentó una generación entera de artistas, pintores, y bailarines, charlatanes e inadaptados que formaban parte de la escena Underground de Nueva York. Nunca anticipamos que Style Wars cambiaría nuestras vidas y tendría tanta relevancia en la democratización de la cultura y el arte moderno a nivel mundial. De manera que cuando hablo de Henry, particularmente en el primer punto acerca de proporcionarnos un espejo en donde reflejar la totalidad de nuestra propia existencia y nuestras contribuciones a la sociedad, Style Wars cambiaría profundamente la manera de verme a mí mismo, a mis colegas, y a nuestra historia, la manera de pensar, de investigar y de hablar sobre el tema, y de cómo desafiar toda la historia del arte realzando la obra de los trenes que corren sobre rieles elevados.