MARCIA MARCUS

Role Play: Paintings 1958 - 1973

October 12 - December 2, 2017

ISBN 978-0-9844715-3-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956469

Marcia Marcus Role Play: Paintings 1958 - 1973

First published in the United States of America by Eric Firestone Press, 2017

Eric Firestone Press 4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, NY 11937 USA tel (631) 604-2386 ericfirestonegallery.com

All artwork © Marcia Marcus except pg 7: Alex Katz, Marcia, 1959, oil on linen, 49 x 50 in. Collection of the artist. © Alex Katz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY & pg 8: Gustave Courbet, The Artist’s Studio, a real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life Between 1854 and 1855, oil on canvas, 361 x 598 cm

Photograph on page 7, © Luc Demers

Photographs on pages 9 & 12, © Marcia Marcus, courtesy of the studio of Marcia Marcus and Kate Prendergast

Photograph on page 8, © RMN-Grand-Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Gérard Blot / Hervé Lewandowski

Photographs on pages 22 & 57, © Petegorsky / Gipe Photo

Photograph on page 25, © Whitney Museum, NY

Photographs on pages 36 & 38, © Ann Shelbourne

Photograph on page 21, © John Goodrich

All other photographs, © Jenny Gorman

Photographs on pages 6, 11, & 30 appear courtesy of the studio of Marcia Marcus, and Kate Prendergast

Design

by

Kristina Felix

Printed by Brilliant Graphics

400 Eagleview Blvd

Exton, PA 19341

Figure in the Practice Mirror: Marcia Marcus’s Role Play

by Jessica Bell Brown

“People would love to have paintings they don’t want to look at,” the artist Marcia Marcus once said provocatively in an interview.1 In this statement, she was pointing out that it is only through sustained looking that we achieve a greater understanding of art. The ease of narrative can foreclose complexities that exist visually. Marcus’s portraits and figurative paintings of the late 1950s through the 1970s defy expectations of clear-cut narrative and meaning. The people in her images will not reveal; rather, they demand to be contemplated.

Alex Katz, Marcia, 1959

Long before Cindy Sherman’s beguiling photographs of herself dressed as different fictional characters and “types” in various modes of costume, Marcia Marcus painted selfportraits exploring ideas of identity, representation and selfhood. For years, she herself would be a perennial focus, whether costumed as Medusa or Athena, embracing her husband, or playing the role of the artist in the commissioned portraits of her friends and acquaintances. Marcus’s intentional ubiquity begs the question: how is it that we come to define ourselves? For Marcus, the answer seems to lie as much within images of herself as those that she paints of others. As critic Hilton Als reminds us, “Like dancers, none of us gets over that figure we see in the practice mirror: ourselves.”2

Yoking together Als’ suggestion of a constant, unfinished interrogation of self, and Marcus’s own insistence of the primacy of our gazes in ascertaining knowledge, we can see a choreography of making and unmaking, of looking and being looked upon, and of radical self construction and deconstruction. In Self Portrait with Tights 1959, (p. 19), for example, Marcus resembles a harlequin or dancer. Save for a mere turn of the face, Marcus’s body, clad in only a belted turtleneck and tights, appears frozen, as if gesturing forward. Yet, her eyes return the

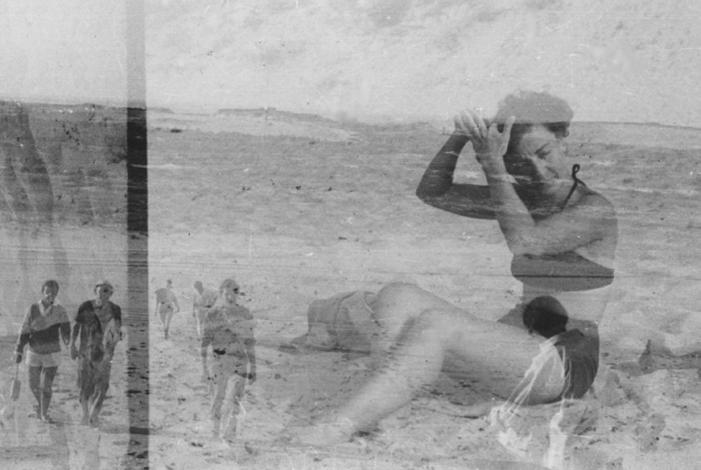

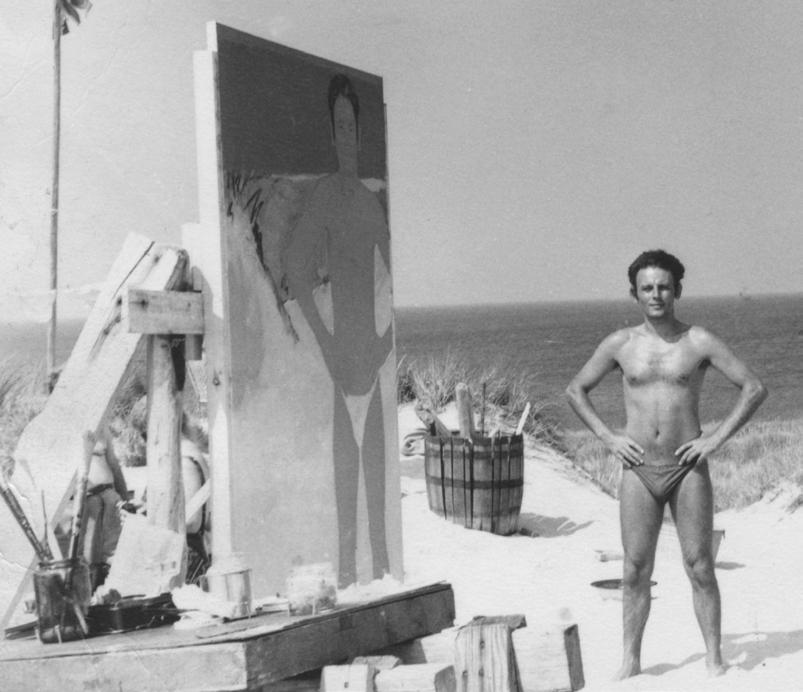

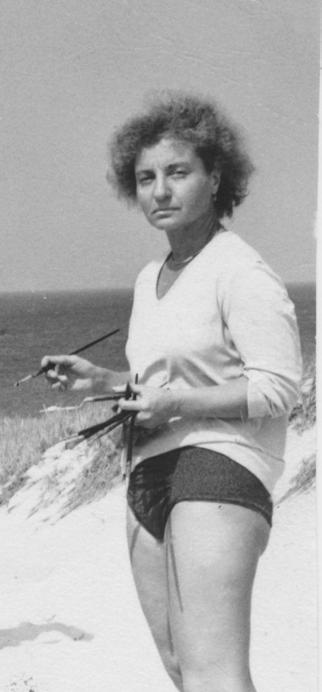

opposite page: Marcia Marcus on the beach, c. 1959

glare of the viewer. Marcus’s propensity for modernist flatness in her silhouetted figures was undoubtedly the influence of Edwin Dickinson, her teacher at the Art Students League of New York where she trained in 1954. At Cooper Union, in the early 1950s, at the height of Abstract Expressionism, where her peer was Alex Katz, Marcus turned not to abstraction, but towards herself as a subject of investigation.

Marcus showed a suite of perplexing portraits like these in the spring of 1959, after she and fellow artists Red Grooms and Bob Thompson were inaugural collaborators in the experimental artist-run space Delancey Street Museum, a boxing gym that Grooms had converted into a private studio and gallery space open to the public in lower Manhattan.3 During the run of the Delancey Street Museum and concurrent with her painting practice, Marcus went on to collaborate with Richard Bellamy, Grooms, and Thompson in one of the earliest happenings, In the Garden: A Ballet, a performance that she organized, incorporating balletic movement and poetry recitations.

Considering how artists imagine themselves within the history of art, it is no coincidence that Gustave Courbet’s L’Atelier du peintre (The Artist’s Studio) (1854-1855) was a great inspiration to Marcus. In this 19th century French masterpiece, patrons, painter, model, and Courbet’s own paintings all share the space of the frieze. Courbet saw himself as inseparable from the people who chose to represent. Marcus enjoyed the Courbet’s unabashed joy of representation, calling it an “impossible painting” but “passionate” and “full of intensity”. Take

Frieze: The Porch 1964, (p. 28) where Marcus adapts the allegorical and compositional structure of Courbet’s L’Atelier. From left, Marcus depicts her friends – literary critic Jill Johnston and painter Barbara Forst, at center a mature Marcus, draped in an elegant floral cloak, and on the far right, in juxtaposition, her father and herself as a young girl, reproduced from a family photograph now at human scale. There is little interaction between the women; instead they are in isolated poses, each confronting the viewer. Here Marcus positions herself as maestro of a universe that centers women as arbiters of cultural production. Folding time onto itself, she makes the canvas capacious enough to hold past and present together.

Gustave Courbet, L’Atelier du peintre, 1854, 1855

Art and the Family 1966, (p. 44) similarly traverses Marcus’s penchant for making onlookers hyper-aware of both the fabrication. of the picture and the artist’s desire to materialize her sphere of everyday life. In this work, Marcus combines collaged elements like a found image of James Baldwin, a Rene Magritte reproduction, ancient ruins, and gold leaf, with phrases clipped from newspapers like “family security,” “Daddy,” “Your wife,” “ego,” and “the endless war.” These words swirl around a depiction of Marcus’s nuclear family. At center Marcus lovingly embraces her husband Terence. Yet she split the canvas nearly in half for the children to picture themselves, embellishing the painting with their doodle-like marks and sketches.

Art and the Family coincides with Betty Friedan’s groundbreaking treatise The Feminine Mystique, published just two years prior in 1964, and the bourgeoning second-wave feminist movement. Marcus demonstrates a deep and radical awareness of social upheaval, from the Vietnam war to women’s liberation, to the ways in which gender constructions penetrate how we come to understand family structure. “She is not painting on the inclines of definition, but is rather, directly involved,” Valerie Petersen wrote of Marcus in a 1960 review of the Young Americans show at the Whitney Museum. 4 By picturing herself in the context of her family, and in the context of her circle of artist and literary peers and friends, a notion of relational self-hood comes into relief.

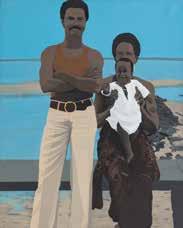

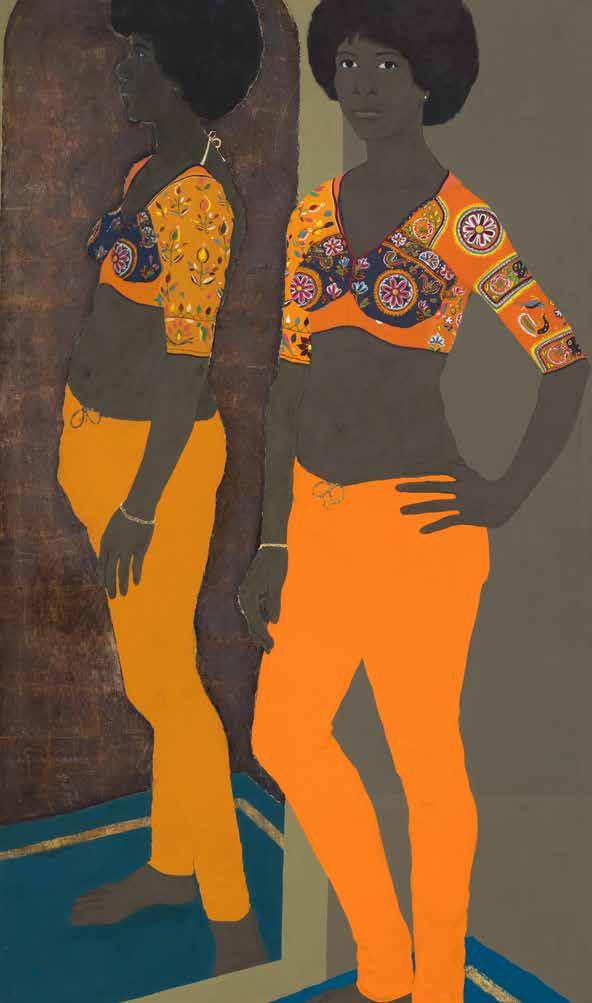

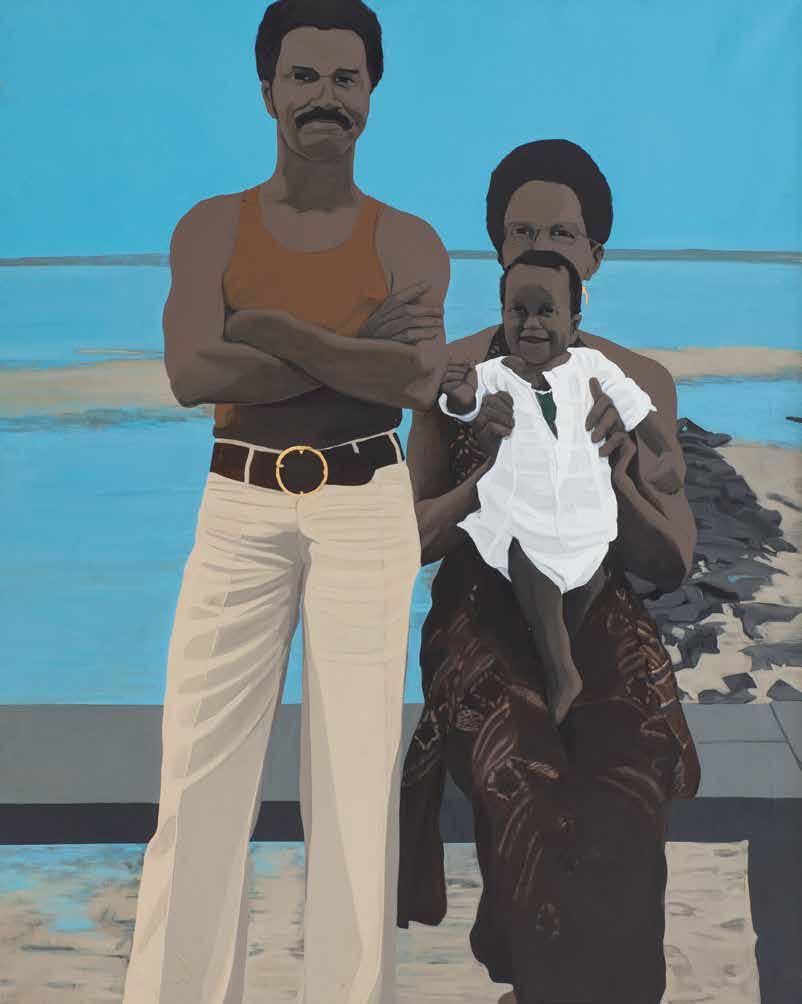

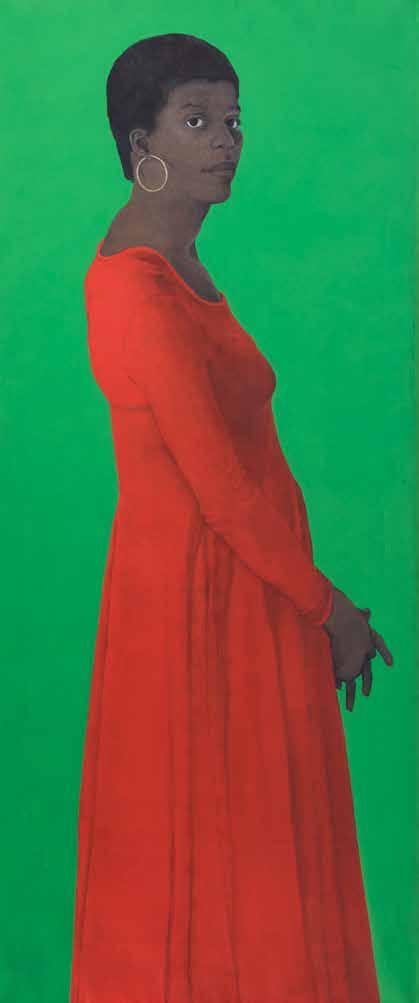

Other aspects of identity, like race, were not above complication for Marcus. While one could surmise that Marcus’s performative self-portraits make space for a deconstruction of white womanhood through her practice of masquerade and masking, she viewed her subjects with an empathetic and generous lens, as seen in lesser known works like her vibrant portraits of black sitters, families and women in particular. At a time in the post-civil rights decade where American society may have been viewed as staunchly black and white, she seemed to thrive in the gray areas of life. Stunning images of friends like Anna 1973, (p. 62) and Renoir 1968, (p. 49) are a testament to the expansiveness of her liberal creative community. Renoir, who occasionally babysat for Marcus, appears “twinned” in a splendid navel orange pants and a patterned crop-top. Marcus captures Renoir with two starkly different energies, straightforward and vulnerable, and guarded as a

Marcia Marcus, self-portrait with mother and daughter, 1960

reflection in the mirror. With this trope of a split perspective, Marcus hedges against any reductive consumption of her subject’s personhood; the mirror here is allegorized as a site for projection and possibility. Marcus portrayed everyday people with the same tenderness and dignity as she did her family and circle of artist friends, as evidenced by an exuberant portrait of a young African American family, Tyna and Alvin, and their young baby Marcus created in Provincetown, where she summered and made works for two decades.5 Though little is known about her friendship with the family, Marcus depicted an alternative image of black families that ran counter to stereotypes of brokenness and poverty plaguing popular culture and perpetuating cycles of social and economic inequity, opting instead for a radical ordinariness in her treatment of black bodies. She depicted the family together, prideful and joyful against a backdrop of the Cape’s familiar cerulean blue sky.

Seemingly, Marcus’s ambition was to deconstruct the ways in which we come to see and imagine selfhood, pointing us back to its inextricable tie to those around us. Though on occasion labeled “unrelentingly theatrical,”6 or narcissistic and deadpan, hers was a pursuit of human interest, the notion that our humanity is tied to not only how we imagine ourselves but how we come to understand our connection to those around us. Critics did not anticipate a sea change in which an artist like Marcus could use the facticity of these conflicting roles as a mother, wife, friend, and citizen as fertile ground for conceptual play, social critique, and a constant desire to reflect that figure in the practice mirror.

1 As quoted from an archival interview transcript with the artist by a student of Marcus, c. 1980s, received from Kate Prendergast, September 5, 2017.

2 Hilton Als, White Girls, 2013, McSweeney’s: New York, p49.

3 For a history of the Delancey Street Museum and other artist-run cooperatives and galleries in New York, see by Melissa Rachleff’s Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 published by New York, NY: Grey Art Gallery, New York University; Munich ; London; New York, NY: DelMonico Books, an imprint of Prestel, 2017.

4 “Young Americans Seen and Heard at the Whitney Museum” in Art News, Volume 59 Issue 56, November 1960, p36.

5 Tyna, Alvin, and Baby, 1970/71, acrylic on canvas.

6 See Phyllis Derfner’s review, “Marcia Marcus at ACA.” Art in America 63, no. 2 (March–April 1975): p89.

opposite page: Marcia Marcus, double exposure photograph of a proto-Happening, Provincetown, 1954

Tyna, Alvin, and Baby, 1970/71

“A recent reviewer had the perception to realize that my Athena has an implication of sexuality. I believe even goddesses should be complete women.”

-

Marcia Marcus, Art: A Woman’s Sensibility / ed. Miriam Schapiro, 1975

PLATES

Marcia Marcus self-portrait, c. 1953

Medusa, 1958

oil and gold leaf on canvas

50 x 40 inches

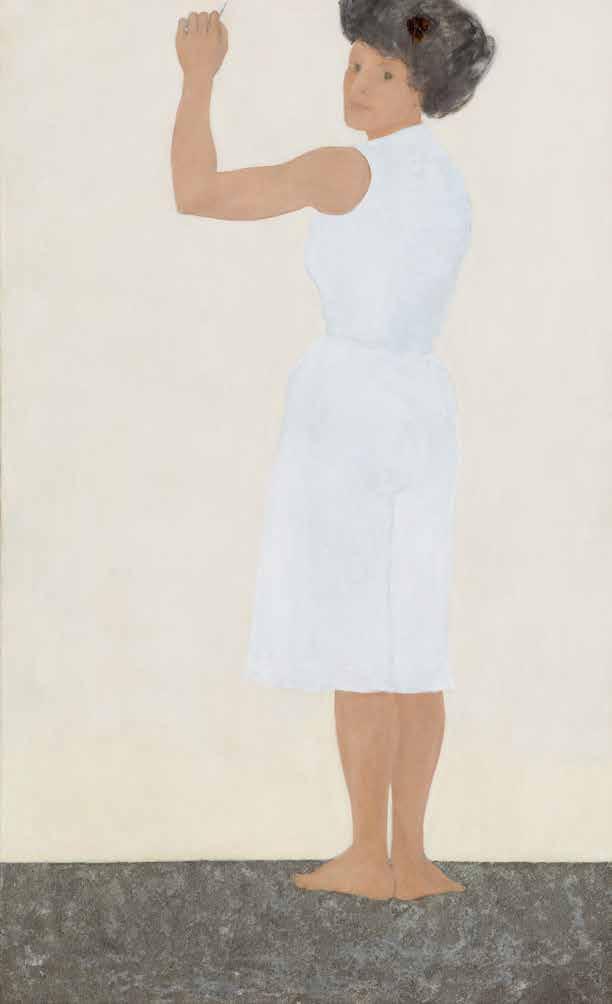

Self-Portrait in White Dress, 1959 oil, sand, and collage on canvas

60 x 37 inches

Self-Portrait with Tights, 1959 oil and collage on canvas

57 1/4 x 40 inches

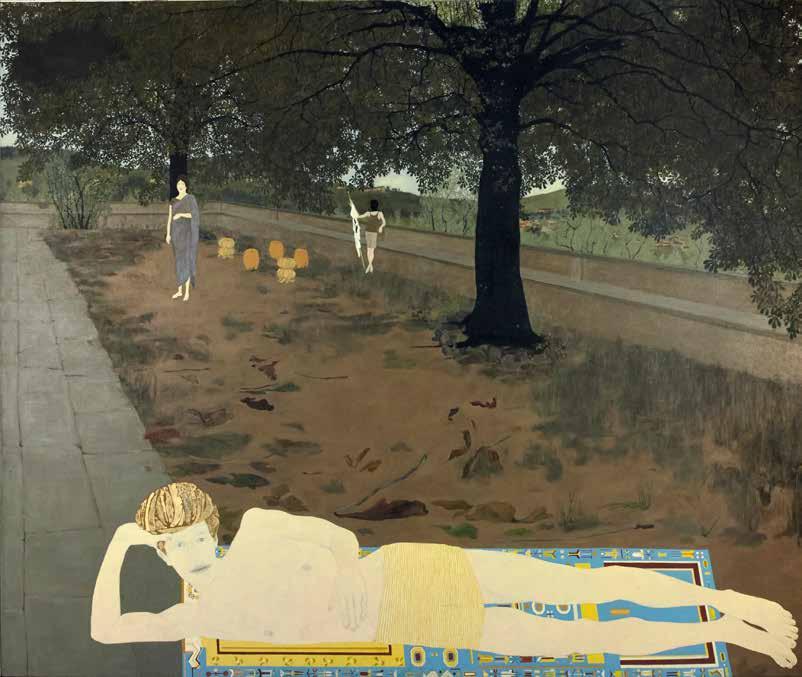

Florentine Landscape, 1961 oil on canvas

78 1/2 x 94 1/2 inches

Collection of the Neuberger Museum of Art

Double Portrait, 1962 oil on two canvases

68 5/16 x 78 1/8 inches

Collection of the Williams College Museum of Art

Nancy and Leaves, 1963 oil and acrylic on linen

38 5/8 x 38 1/2 inches

Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art

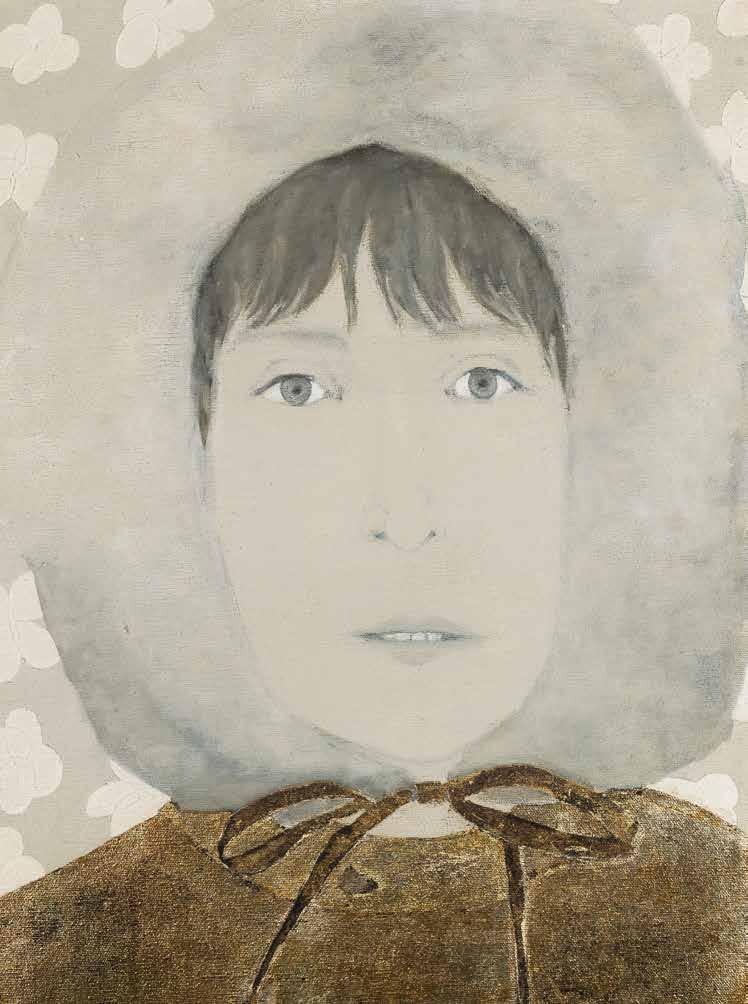

24 3/4 x 16 inches

Jack, 1964 oil on canvas

Frieze: The Porch, 1964 oil and collage on canvas

77 x 115 inches

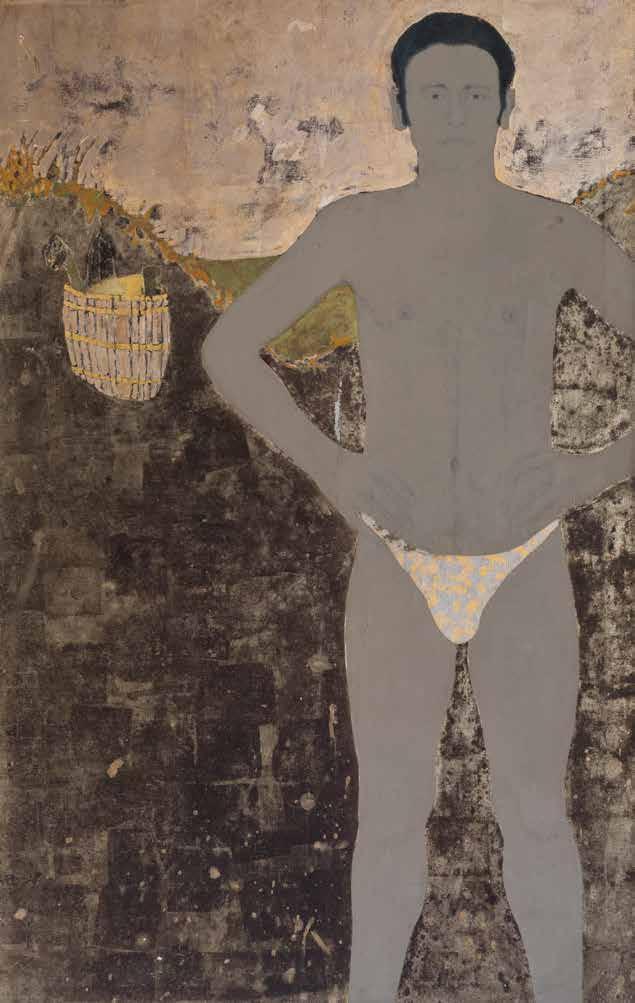

Marcia Marcus painting Lucas Samaras in Provincetown, 1965

Lucas in the Dunes, 1965 oil on canvas 53 x 35 inches

Private Collection

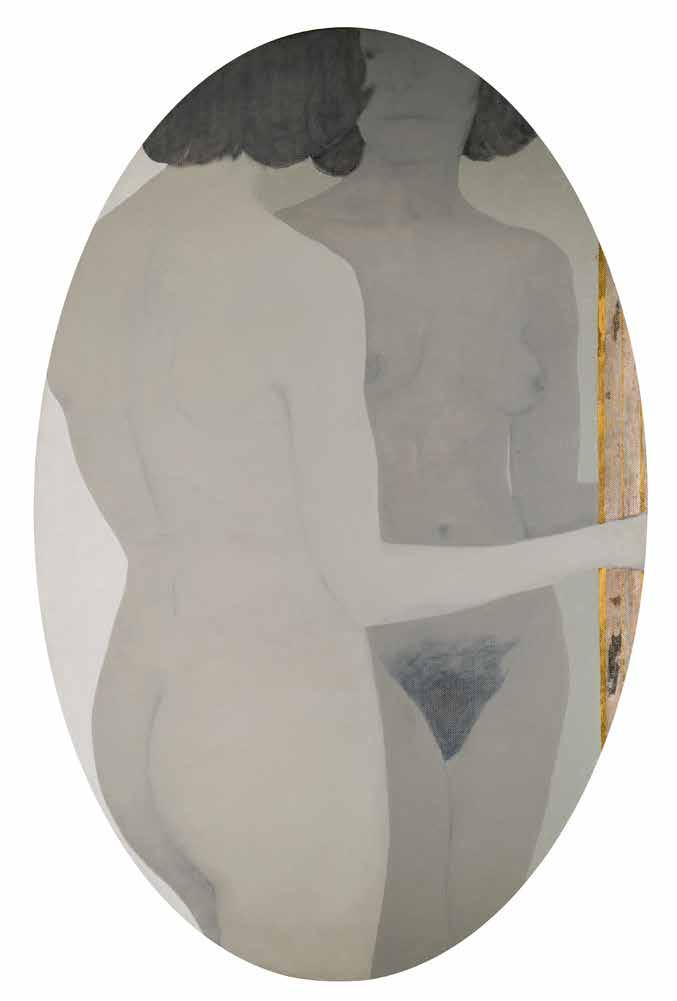

Nude (Judy), 1965

oil and silver leaf on canvas

23 1/2 x 48 inches

Nude with Mirror, 1965 oil and gold leaf on shaped canvas 47 1/2 x 30 1/2 inches

Private Collection

20 x 15 inches

Chippy Irvine, c. 1965 oil on canvas

Private Collection

50 x 50 inches

Hazel, 1966 oil on canvas

Emily, 1966 oil on canvas

48 x 25 inches

Art and the Family, 1966 oil and collage on canvas 77 x 132 inches

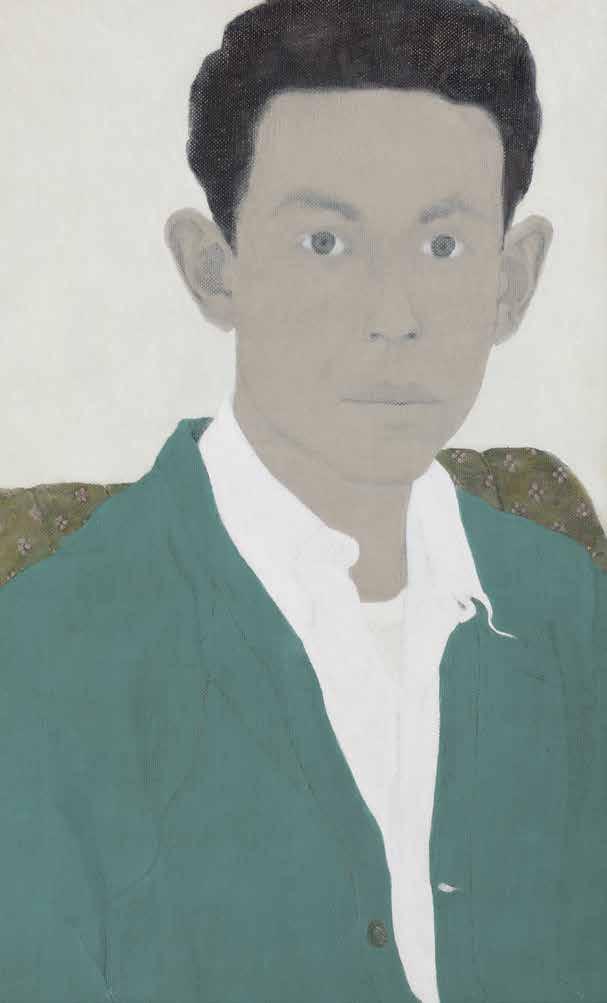

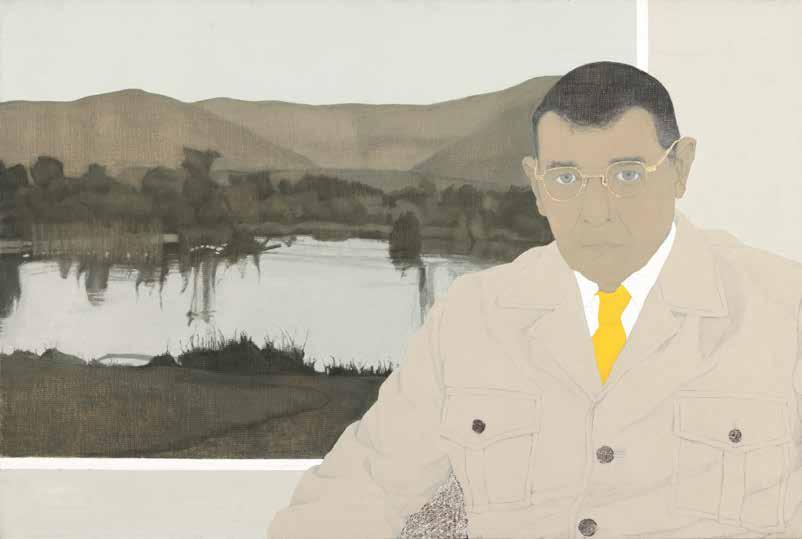

Henri Zerner, 1967 oil on canvas 30 x 18 inches

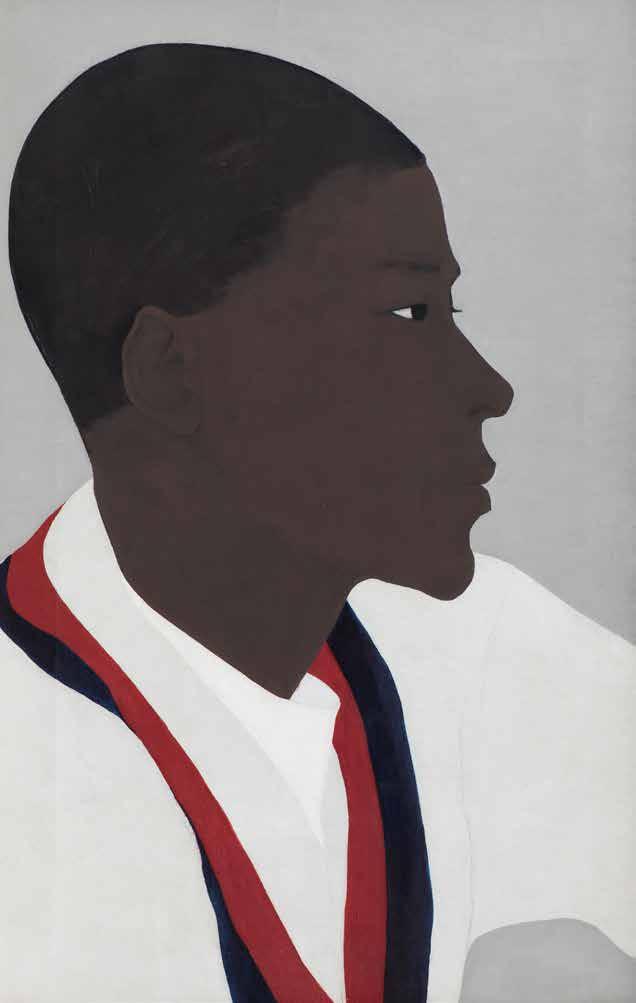

, 1968

71 3/4 x 42 inches

Renoir

oil and silver leaf on canvas

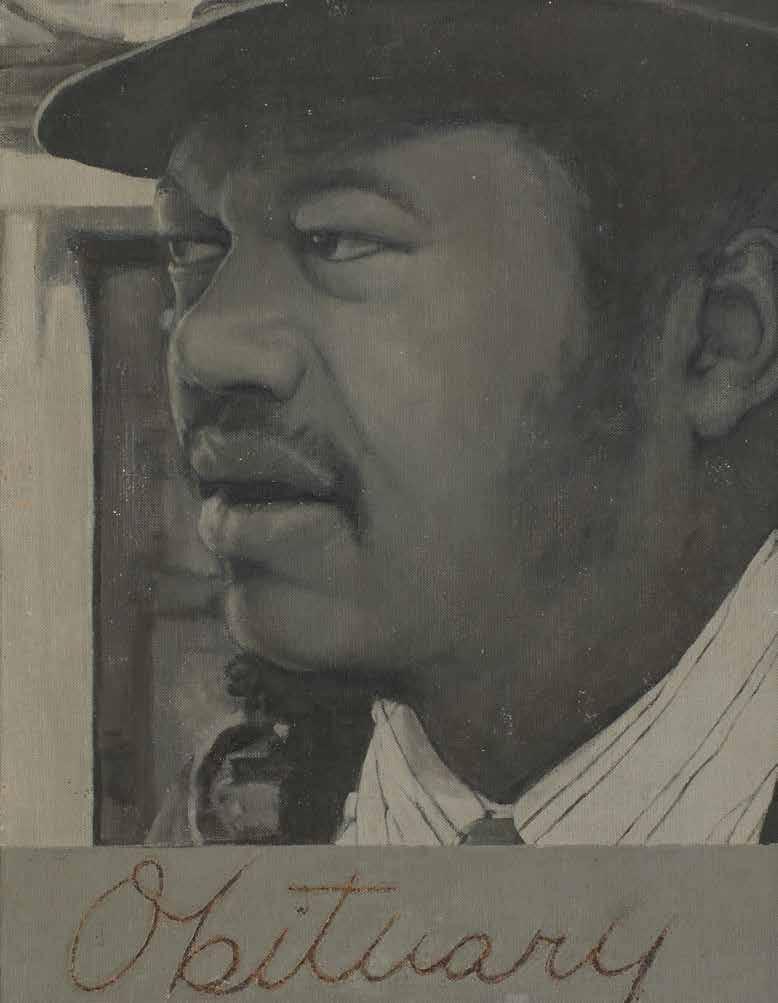

Obituary (Bob Thompson), 1968 oil on canvas

16 x 10 inches

Private Collection

Family II, 1970

acrylic and gold leaf on canvas

70 x 95 inches

Tyna, Alvin and Baby, 1970/71 acrylic on canvas

49 3/4 x 40 inches

24 x 36 inches

Portrait (Lawrence H. Bloedel), 1971 oil on canvas

Collection of the Williams College Museum of Art

Kitty II , 1971 oil on canvas

24 x 10 inches

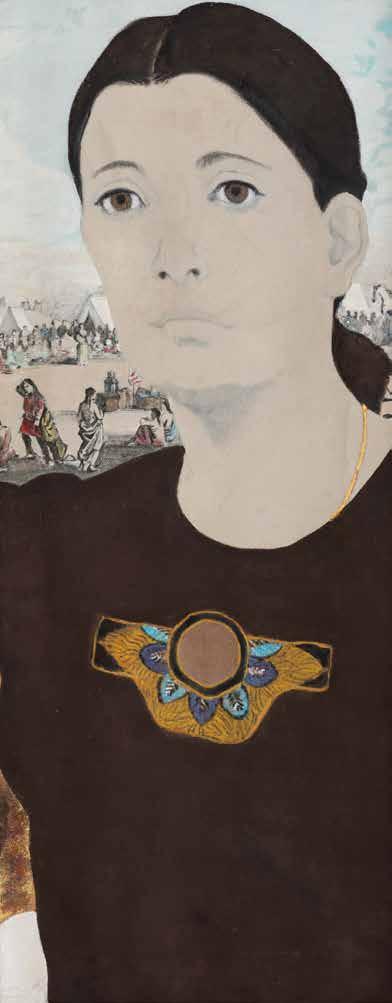

Portrait of Rachel Giese, 1972 oil on canvas

41 x 31 inches

Private Collection

72 1/2 x 30 inches

Anna, 1973 oil on canvas

Medusa, 1958

oil and gold leaf on canvas

50 x 40 inches

Self-Portrait in White Dress, 1959

oil, sand, and collage on canvas

60 x 37 inches

Self-Portrait with Tights, 1959

oil and collage on canvas

57 1/4 x 40 inches

Florentine Landscape, 1961

oil on canvas

78 1/2 x 94 1/2 inches

Neuberger Museum of Art

Purchase College, State University of New York

Gift of Roy R. Neuberger 1975.16.28

Double Portrait, 1962

oil on two canvases

68 5/16 x 78 1/8 inches

Williams College Museum of Art

Bequest of Lawrence H. Bloedel, Class of 1923

Nancy and Leaves, 1963

oil and acrylic on linen

38 5/8 x 38 1/2 inches

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchased with funds from an anonymous donor 63.43

Jack, 1964

oil on canvas

24 3/4 x 16 inches

Frieze: The Porch, 1964

oil and collage on canvas

77 x 115 inches

Lucas in the Dunes, 1965

oil on canvas

53 x 35 inches

Nude (Judy), 1965

oil and silver leaf on canvas

23 1/2 x 48 inches

Nude with Mirror, 1965

oil and gold leaf on shaped canvas

47 1/2 x 30 1/2 inches

Chippy Irvine, c. 1965

oil on canvas

20 x 15 inches

Hazel, 1966

oil on canvas

50 x 50 inches

Emily, 1966

oil on canvas

48 x 25 inches

Art and the Family, 1966

oil and collage on canvas

77 x 132 inches

Henri Zerner, 1967

oil on canvas

30 x 18 inches

Renoir, 1968

oil and silver leaf on canvas

71 3/4 x 42 inches

Obituary (Bob Thompson), 1968

oil on canvas

16 x 10 inches

Family II, 1970

acrylic and gold leaf on canvas

70 x 95 inches

Tyna, Alvin and Baby, 1970/71

acrylic on canvas

49 3/4 x 40 inches

Portrait (Lawrence H. Bloedel), 1971 oil on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Williams College Museum of Art

Bequest of Lawrence H. Bloedel, Class of 1923

Kitty II, 1971 oil on canvas

24 x 10 inches

Portrait of Rachel Giese, 1972 oil on canvas

41 x 31 inches

Anna, 1973 oil on canvas

72 1/2 x 30 inches

CHECKLIST

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Eric Firestone Gallery wishes to thank the family of Marcia Marcus, and particularly Kate Prendergast, daughter of Marcus, for their dedication to Marcus’s work. Kate’s organization, enthusiasm, and willingness to assist with every aspect of research, planning, and production has made this exhibition possible.