Issue | Putanga 22/2023

Efforts going to waste A weighty issue engineers can’t refuse

Beyond the foreseeable future Could futures thinking help your business?

All for four Engineering a shorter work week

Issue | Putanga 22/2023

Efforts going to waste A weighty issue engineers can’t refuse

Beyond the foreseeable future Could futures thinking help your business?

All for four Engineering a shorter work week

The business of survival

8 Engineering longevity The business of survival.

22 Taking on the tertiary sector This new university Vice Chancellor has his sights set on sustainability.

30 Creative thinking clears water An innovative Northland culvert replacement has reaped rewards, and a big award.

52 Secret life of engineers Outside of her day job, this engineer has fans that span generations.

PO Box 12 241

Wellington 6144 New Zealand

04 473 9444

hello@engineeringnz.org engineeringnz.org

Editor Jennifer Black editor@engineeringnz.org

Design Manager

Angeli Winthrop

Advertising sales advertising@engineeringnz.org

04 473 9444

Subscriptions

hello@engineeringnz.org

Circulation

Magazine 360° Circulation for the 12 months ended 31 March 2022.

New Zealand 13,749

Print ISSN 2537-9097

Online

EG online

ISSN 2537-9100

PDF versions of EG are available for members on our website or through our EN.CORE app.

Printing

Your cover is printed on Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) approved and elemental chlorine free (ECF) paper. The inside pages are Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) approved and elemental chlorine free (ECF). EG is printed using vegetable-based inks made from renewable sources. Printing and fulfilment by Printlink.

Please recycle your paper envelope – it’s 100% recyclable and made from PEFC accredited paper.

Disclaimer

Advertising statements and editorial opinions expressed in EG do not reflect the views of Engineering New Zealand Te Ao Rangahau, its members, staff, or affiliated organisations unless expressly stated.

This issue of EG was published in March 2023.

The former horse stables became J&D McLennan's factory when the McLennan brothers returned from WWII.

Photo: J&D McLennan, circa 1945.

8 Engineering longevity The business of survival.

16 Efforts going to waste A weighty issue engineers can’t refuse.

22 Taking on the tertiary sector This new university Vice Chancellor has his sights set on sustainability.

24 Recognising excellence Insights from our new Distinguished Fellows.

30 Creative thinking clears water

An innovative Northland culvert replacement has reaped rewards, and a big award.

36 Beyond the foreseeable future Could futures thinking help your business?

40 Reflecting on lessons learnt The legal team reflects on some of the biggest recent learnings in the engineering profession.

41 Driving force behind sector Why it’s a pivotal time for heavy vehicle certifying engineers.

42 A century-plus of consultancies

Why some of the country’s oldest engineering consultancies have gone the distance.

44 Embracing neurodiversity at work

The neurodiverse could be part of the solution to improving productivity and innovation for businesses.

46 All for four Engineering a shorter work week.

48 Who’s complaining? Most of the complaints Te Ao Rangahau receives are not for serious technical issues.

49 Intersection Crossing paths with engineers.

One of the loudest noises ever created. That’s what scientists’ calculations showed regarding the first launch of Saturn V, NASA’s heavy-lift launch vehicle that powered much of the USA’s space exploration programme in the 1960s and 70s. Until November 2022, when NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) launched the Artemis 1 mission, Saturn V held the title as the most powerful rocket ever successfully launched. Designing a rocket to send a human being to the moon was always going to require some serious engineering though. How much? Well, more than 400,000 engineers, scientists and technicians from more than 20,000 companies and universities contributed to the Apollo space programme’s success. To put that in perspective, there are around 77,000 engineers in New Zealand currently. Perhaps the next-gen SLS is already being dreamed up by one of New Zealand’s tamariki taking part in the Wonder Project Rocket Challenge?

2,800,000kg

weight of Saturn V – same as 400 elephants

US$6.4bn

cost of the Saturn V project in 1973 terms (US$44.8bn today)

3,000,000+ parts make up Saturn V 21h 36m

time spent by Apollo 11 astronauts on the moon’s surface, made possible by Saturn V

Yen

Engineering Envy #156 Chosen by Engineering New Zealand Te Ao Rangahau staff Engineering EnvyIt took humans from our cradle to another celestial body. The Saturn V rocket represents a pinnacle of engineering endeavour and it looks pretty damn cool too!

–

Comer-Hudson, Competence Assessment Advisor

Join us as we celebrate women in STEM who are ‘Shaping the Future’. The Association for Women in the Sciences (AWIS) and Engineering New Zealand are excited to welcome STEM professionals from across the globe at the 19th International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists. Through presentations, discussions, networking, and field trips, we’ll bring together global expertise to discuss key initiatives driven by women in STEM, and hear from keynote speakers including Professor Dame Juliet Gerrard and Associate Professor Siouxsie Wiles MNZM.

Engineer Furkan Kılıç established rapid response movement Earthquake Help Project immediately after the TurkeySyria earthquake using tech to help NGOs and rescue teams on the ground.

“We

University of Canterbury Civil Engineering Senior Lecturer Dr Tom Logan following devastating Auckland flooding in January.

“… trying to build a car in 12 months was never a smart or easy decision but now it’s all coming together, and I feel really confident in the car.”

University of Canterbury Motorsport team principal Kaenan Ferguson and club members aim for a world landspeed record in South Australia in March in a rocket-shaped electric car they’ve designed and built.

Nau mai koutou katoa.

This year has started with some devastating weather events and my thoughts are with all those who have been affected. Thanks to the many engineers central to the response, and rebuild. Engineering in New Zealand continues to evolve to meet society’s latest challenges and expectations. In this issue of EG we celebrate both the engineering longevity and legacy of many of our engineering firms, institutions and projects. For 109 years, Engineering New Zealand Te Ao Rangahau has been part of that journey. Its initial aims were to raise the status of the profession and promote continued education and professional development. It pushed for a system of registration that resulted in the Engineers Registration Act, 1925. These aims still have resonance and indeed one of our new ambitions is Professionalism. The irony is not lost on me that we are again working with government to reform occupational regulation of engineers.

and congratulate them on this recognition. One of the best things during my time as President was calling new Fellows with the good news.

I’m very excited about how engineering continues to evolve. Here, we showcase a number of enduring businesses that have achieved longevity in part because they’ve continued to adapt, including adapting to the ongoing challenges of Covid-19, climate change and supply chain disruption. We also share insights from engineer and futurist Dr Kristin Alford, a keynote speaker at the 19th International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists which Te Ao Rangahau is co-hosting in Auckland in September.

Former astronaut, engineer and fighter pilot Buzz Aldrin’s tweet after marrying his fourth wife, who has a PhD in chemical engineering.

We also build our engineering legacy through personal contributions, so it’s very satisfying to see Distinguished Fellows and some of our new Fellows recognised in this issue. I thank them for their service

When we reimagined our strategy last year, we considered current challenges and undertook foresighting work to anticipate what engineers of the future need to be. Our ambitions – Professional, Connected, Leading and Thriving – will enable us to evolve as we continue on our journey. Look out for the actions from Te Ao Rangahau in 2023 that will help make this happen.

Dr Tim Fisher FEngNZ President, Engineering New Zealand Te Ao Rangahau“We receive messages that people are being found in rubble and saved because of these applications.”

need to stop building in places that are at risk from natural hazards and also we need to stop building in places that make the flooding worse.”

“On my 93rd birthday... I am pleased to announce that my long-time love Dr Anca Faur & I have tied the knot.”

We make SEISMIC® reinforcing steel to a high standard. Then we put it through a rigorous testing regime to prove it.

All SEISMIC® products are tested in our dedicated IANZ-certified laboratory to ensure they meet the stringent AS/NZS 4671 Standard. Our products are designed for New Zealand’s unique conditions, by a team which has been manufacturing locally for 60 years.

That’s why we’ve been entrusted with some of the country’s most significant infrastructure and building projects, and why people continue to turn to us for strength they can count on. For assurance, confidence and credibility, choose SEISMIC® by Pacific Steel.

For more information, contact us at info@pacificsteel.co.nz or visit pacificsteel.co.nz

• 2022 Owners Cash Surplus = $559K

• Consistent sales growth, over 25% from 2021 to 2022FY

• Work from home business model (7 staff)

• Ongoing support from owner (up to 2 years neg.)

The business would be the ideal next step for a recently chartered Geotechnical Engineer who is wanting to control their own destiny and maximise long term income, or an experienced Engineer looking to do their own thing, providing excellent earnings without years of building up a client base.

To find out more, contact Alan Dufty from Barker Business Brokerage on 021 550 645 or aland@barkerbusiness.co.nz. Reference #3308

Engineers have played an important role designing and building New Zealand’s towns, roads, bridges and railways since colonial times. This year, Dunedin's Farra Engineering turns 160 and its history spans the gold rush, two World Wars, the Depression and two global pandemics. Other firms celebrating big birthdays in 2023 include Beca (103), Fulton Hogan (90) and Fraser Engineering (70). There are too many to list, but we pay tribute to just some of the firms that have made a lasting impact on this country – and are in it for the long haul.

WRITER | KAITUHI RACHEL HELYER DONALDSON

WRITER | KAITUHI RACHEL HELYER DONALDSON

Secret to Beca’s longevity? Our employee ownership model helps define our culture and underpins our values. We have longstanding relationships with clients and partners built on mutual respect, and we take pride in delivering innovative solutions.

How do you move with the times? Founded as an engineering practice, Beca has grown into a global multidisciplinary professional services consultancy. We’re also scientifically minded, naturally curious and open to embracing change.

How have the types of jobs you do changed? As the world has changed, Beca has evolved, too: from a small number of engineering disciplines to more than 75 diverse disciplines.

How has climate change affected your work? It’s an area our people have been technically knowledgeable in for decades. As awareness of its impacts grows, we can use our skills and experience to help clients.

How has your focus on sustainability changed?

A decade or two ago, sustainability was thought to be simply about protecting the physical environment. Today it’s more holistic and incorporates a Māori world view.

How has the role of women in the industry evolved?

Our industry is traditionally male dominated. We have a goal of achieving at least 40 percent women and at least 40 percent men, and 20 percent women, men and non-binary people across all levels of business by 2030.

Longest-serving staff member? 50-plus years.

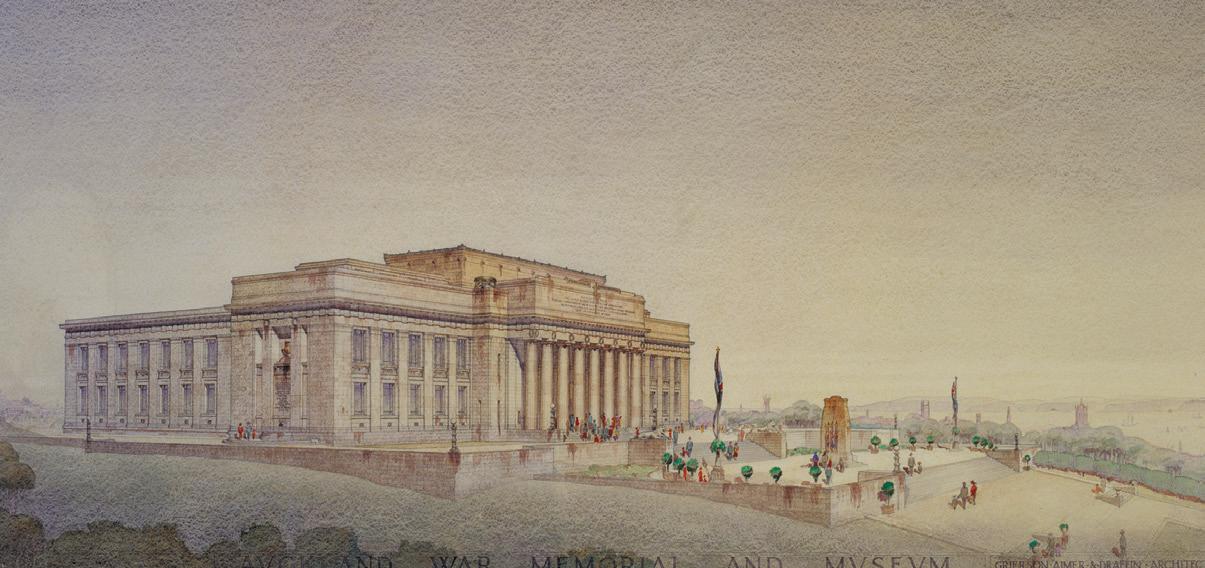

A major early project? Founder Arthur Gray’s structural design of Auckland War Memorial Museum in 1929.

Secret to Farra Engineering’s longevity? Continuous reinvention and adaptation to the changing markets, along with stability: we’re still owned by descendants of original founders Janet and Joseph Farra.

How do you move with the times? We’ve always invested in new capabilities and innovation in multiple new markets, as older markets reach the end of their attractive life. A creative approach, being staunchly local while focused on global markets is essential.

How have the types of jobs you do changed? We started out as tinsmiths, we’ve been auto assemblers and owned ships. These days key specialist areas include maintaining, repairing and overhauling plant infrastructure and heavy industry, contract manufacturing and production engineering.

How has climate change affected your work? It’s had little direct impact as yet, but we have seen more flood mitigation and infrastructure work.

How has your focus on sustainability changed? Hugely. Sustainability wasn’t really a thing back in 1863! But these days every investment we make has the environment in mind.

How has the role of women evolved? Historically it’s been male dominated, although women briefly worked in the factories in WW2. Over the past five years we have been on a push to correct that imbalance. Currently, more than 10 percent of our 110 staff are female, including five women in technical roles.

Longest serving staff member? 45 years.

Secret to your longevity? We’re an employee owned and operated organisation – people are at the heart of what we do and we genuinely care about the wellbeing and development of our staff. We empower them to do the technical work they love, and we keep great outcomes for our clients, communities, and the environment front of mind.

How do you move with the times? By staying focused on our vision of a “sustainable future”. We’re continually investing in our current strategies for better sustainability and increased digital and global connectedness. We’re always keeping an eye on new and emerging markets, trends and seeing how we can optimise and innovate.

How have the types of jobs you do changed? The work we do has expanded from specialist geotechnical engineering to being multi-specialist across geotechnical, water, environmental, civil, digital, and advisory. Our team across New Zealand and Australia work in different sectors including Energy, Industry, Land, Natural Hazards Resilience, Transport, Water and Waste.

How has climate change affected your work? T+T has always been strong in natural hazards and resilience work and because of climate change, our new service supporting adaptation and mitigation are in demand. We’ve also been Ekos-certified Zero Carbon since 2020.

How has your focus on sustainability changed? It’s been a journey. We added water services in the 1970s, environmental services in the 1980s, and developed Environmental Choice New Zealand certifications in the 1990s. Our current sustainability strategy launched in 2021 encompasses three key areas – economy and governance, society and culture, and the natural environment. Our sustainability approach aims to shape a future where the natural environment is valued and protected, and where all people are healthy, fulfilled and empowered to pursue their aspirations.

How has the role of women evolved? We were male dominated, but now we actively strive to foster a culture that embraces diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging. Currently, women make up 36 percent of our technical roles, 36 percent of our executive roles, and 44 percent of our Board. An improvement on the past, but there is still plenty of work to do!

Longest serving staff member? 47 years.

1959

A major early project? Auckland Harbour Bridge.

Auckland Harbour Bridge under construction, February 1959. Photo: Whites Aviation Ltd/ Alexander Turnbull Library Ref: WA-49308

Auckland Harbour Bridge under construction, February 1959. Photo: Whites Aviation Ltd/ Alexander Turnbull Library Ref: WA-49308

From manufacturing New Zealand’s first Ferris wheel to developing the world’s first automatic airbridge, Lower Hutt firm J&D McLennan Engineering has ensured its longevity with a willingness to constantly evolve and innovate.

The company was founded in 1945 by twins James and Duncan McLennan, after they returned from World War II. Initially, the brothers ran the fledgling firm from rented, dirt floor stables. But as the company grew, they bought land in the Hutt Valley and built their own factory.

Current Managing Director, Duncan McLennan CMEngNZ, who is James’s son, says the company has always embraced change.

“We’re still general engineers but we’ve also specialised to become more efficient and more cost effective.”

The post-War years saw J&D McLennan move into manufacturing road works components through to building entire asphalt plants. An early, one-off highlight was the production of the country’s first Ferris wheel, around the early 1950s.

In the early 1970s, the company won a contract to supply six airbridges to the new Auckland International Airport. Airport Equipment Ltd was established in 1974, with offices in Lower Hutt and Sydney. A third was set up in Auckland in 2015. It has 40 New Zealand staff and 10 in Australia.

Duncan says Airport Equipment is the only Australasian company to manufacture passenger boarding bridges. It has produced more than 400 airbridges throughout Aotearoa, Australia and the South Pacific. It’s also the only company in the world to offer a full service – designing,

installing and servicing – aircraft passenger boarding bridges. This offering allows the company to compete with cheaper overseas rivals.

With most of its work in aviation, Covid-19 had a major effect.

“Project work was cancelled and maintenance contracts were reduced to 20 percent of what they had been.”

However, since mid-2022, the amount of work is greater than what it was prior to the pandemic, Duncan says. But that has caused other issues such as an unavailability of materials and a “chronic” shortage of labour, “skilled or otherwise”.

As the world’s airports reopen for travel, current projects include two new airbridges in Papua New Guinea. In 2022, Airport Equipment began manufacturing 13 airbridges for the new Western Sydney Airport.

In 2021, it developed and installed the world’s first selfoperated airbridge, at Wellington International Airport. Thanks to smart cameras it can drive itself to, and dock with, the aircraft without operator assistance.

Duncan says J&D McLennan is “well structured” to move into the future with his three sons, Andrew, James and Cameron, in leadership roles.

So what’s the secret to the company’s survival?

“The key is honesty, manufacturing products you’re proud to have your name on and giving over-and-beyond service.

“It’s also about understanding technology changes and using that to be better at what you do.”

Workers in front of a J&D McLennan boarding bridge, circa 1976 (Duncan McLennan back left). Photo: J&D McLennan

Airport Equipment's innovative multi-deck boarding of an A380 aircraft at Christchurch International Airport.

Workers in front of a J&D McLennan boarding bridge, circa 1976 (Duncan McLennan back left). Photo: J&D McLennan

Airport Equipment's innovative multi-deck boarding of an A380 aircraft at Christchurch International Airport.

When John Fraser, the founder of J J Fraser Engineering in Lower Hutt, died in May 2022, the 95-year-old was still actively involved in the company he’d founded in 1953, as well as driving around in his Mercedes and designing products for the company.

“He was engineering until the day he passed away,” says Fraser Engineering General Manager Martin Simpson.

“He was amazing and the company was born out of his passion for manufacturing and technology and what that could do for the benefit of society.”

It seems John’s longevity genes also run in the family business, which celebrates 70 years this year. These days it’s jointly run by Martin, and John’s daughter Raewyn Fraser.

Fraser Engineering began when John developed an innovative fuel pump for BP. For almost half a century it was a “machine shop”, manufacturing components for everything from glass laminating machines to cellphone booster stations and ball valves.

Making nozzles for the fire service piqued Martin’s interest in the fire industry. In 2000, Fraser Engineering bought out fellow Hutt Valley firm Lowes Industries, a fire engine manufacturer, and established Fraser Fire and Rescue.

Its first contract to build fire engines was for the Australian Capital Territority (ACT) Emergency Services Bureau followed by the South Australia Metropolitan Fire Service and then New Zealand Fire Service. It builds for South Australia Country Fire Service, Victoria and Northern Territory, in addition to supplying airport firefighting vehicles to the likes of Fiji and Rarotonga International Airports.

The company has around 130 New Zealand staff in Wellington, and 10 people in its Adelaide office, which

was set up in 2018. It has more than 1,000 vehicles in service across Australasia and the Pacific. Fraser Engineering currently produces up to 150 fire engines annually, which Martin hopes to increase to 200-plus a year. The Adelaide branch, which currently focuses on service and delivery, is to expand its manufacturing work.

Making fire trucks “smarter, more ergonomic and reliable” is particularly crucial when dealing with Australia’s devastating bush fires.

Over the decades, Fraser Engineering has dodged the downturns that saw the demise of many Kiwi manufacturers.

“We recognised early on that the key is to take as many processes as you can, in house.”

Business is booming but Martin says the challenge now is finding good staff.

“The thing that really holds us back is a lack of an education system that is properly catering for manufacturing and engineering. We are always restrained by getting more quality people. I would hire 20 people today, if I could.

“But we’re always busy and there’s more opportunities for us now than there ever has been. The future is amazing.”

Dr Graham Ramsay FEngNZ (Ret.) is one of a number of engineers who have captured their extraordinary careers in a book. During 50 years as an engineer he saw many changes in the civil engineering profession and he uses a range of projects, including Dunedin's Abbotsford landslide and the Transmission Gully motorway, to illustrate these changes in technology, legislation and societal expectations. Find out more at writeshillpress.co.nz

We recognised early on that the key is to take as many processes as you can, in house.

– Martin Simpson

If you’re an Engineering New Zealand member, you can now choose how you receive EG magazine – delivered in print directly to your letterbox, or sent digitally to your inbox.

Log in to your online member portal at engineeringnz.org to update your preferences.

Aotearoa generates an estimated 17.49 million tonnes of waste annually. Around 12.59 million tonnes of this goes to landfill, according to data from the Ministry for the Environment, posing a risk to people’s health and the environment. But the efforts of clever engineers – and engineering – aren’t being wasted.

WRITER | KAITUHI RINA DIANE CABALLAR

WRITER | KAITUHI RINA DIANE CABALLAR

The Government is aiding the transition to a low-emissions circular economy through its waste work programme, proposing a new waste strategy and more comprehensive waste legislation, as well as investing in waste reduction schemes. Meanwhile, initiatives such as the Zero Waste Network, representing community enterprises across the country who are working towards zero waste, aim to minimise and ultimately eliminate waste, forging a path toward a zero-waste country. Beyond government intervention and citizen action, engineers are also rising to the challenge.

Shaping a circular plastics economy

In 2021, Aotearoa sent more than 300,000 tonnes of plastic to landfills. That’s a significant amount of waste –one that an interdisciplinary team from the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Engineering and Business School and the RMIT University in Melbourne intends to reduce through a circular market system for plastics. The fiveyear project was awarded an $11.7 million grant from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment's 2022 Endeavour Fund.

“We’re aiming to work towards New Zealand’s goal to be less reliant on virgin plastics and also reduce carbon emissions because if we recycle plastics more, we’re emitting less carbon dioxide,” said Dr Johan Verbeek CMEngNZ, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Auckland and Co-Director of the University's Centre for Advanced Materials, Manufacturing and Design.

Johan and Professor Simon Bickerton of the Faculty of Engineering are investigating how to take waste plastic and process it in a way that would produce better materials and keep it within a circular economy.

“We are researching how to use plasma to modify the properties of polymers, making it possible for us to recycle more materials in a cheap and environmentally friendly way. An example would be if you have a mixture of two or three plastics that’s difficult to separate. We’ll look at how we can use this plasma technology to make a blend that is so good that it can be used instead of virgin materials,” Johan says.

“That way, we can keep plastics in the circular economy for longer. It’s about how we apply material science and design into developing better products and better materials for those products.”

Meanwhile, Associate Professor Julia Fehrer of the Business School and colleagues from RMIT University will design digital tools and develop a digital infrastructure to enable businesses to participate and operate in a circular economy for plastics.

“It’s also about how to get businesses to adapt to, and actively engage in, a circular market,” says Johan.

The project is underway but is still in the initial stages of research, with the team actively recruiting students and staff with a background in mechanical engineering, chemical engineering or materials engineering.

“Because it’s such a transdisciplinary project, these people need to have design skills and practical material science skills, but also be able to understand how to apply materials in making products,” Johan says.

By creating a circular market system for plastics, Johan hopes to contribute to a zero-waste nation.

“Success would be if we can actually reduce the amount of plastic that goes to landfill.”

Compared to plastics, food waste comprises an even bigger part – more than 333,000 tonnes – of waste sent to landfills. In Auckland alone, an estimated 100,000 tonnes of domestic food scraps go to landfill every year. But that’s about to change.

“Auckland has a vision of zero waste to landfill by 2040,” says Parul Sood, General Manager Waste Solutions at Auckland Council.

“As part of that vision and the journey toward zero waste, we’re getting food scraps out of the rubbish bin and into a facility for processing.”

This facility is the Ecogas Reporoa Organics Processing Facility, in the central North Island, which will use anaerobic digestion – wherein bacteria break down waste in the absence of oxygen – to convert 75,000 tonnes of organic material into energy and bio-fertiliser.

“The anaerobic digestion plant will help us divert about 50,000 tonnes of organic material to start with from landfill, and everything that comes out of the plant will have beneficial reuse,” Parul says. She adds that the facility is the first and largest of its kind in the country dealing with kerbside food scraps.

Opposite: A plastic test sample is evaluated for mechanical properties.

Right: A student

Success would be if we can actually reduce the amount of plastic that goes to landfill.

– Dr Johan VerbeekAbove: Professor Simon Bickerton and Associate Professsor Dr Johan Verbeek CMEngNZ.

Local governments like Auckland Council face a number of challenges as they try to achieve zero waste.

“Waste is a systems problem and councils are normally at the bottom of that system,” says Parul. While producers manufacture products, consumers use those products and then waste gets generated, which is where councils come in to provide waste management services.

“It’s a challenge for local governments as we are one stakeholder, but we have to work with the system,” Parul says.

“We need support from the central government to make sure the legislation and rules are right so that producers and consumers do the right thing. For our part, we advocate for best practices so that the policies set in place are workable. All of us need to work together to change the system.”

Engineers also have a vital purpose in helping councils attain their zero-waste goals.

“Thinking beyond what we’ve got is what we would look to the engineering community to give us,” says Parul.

“Their innovation and scientific knowledge is so crucial, and being open-minded about solutions is critical as well.”

Landfills are an essential part of waste management. What started as open dumping progressed into controlled tipping with some protection measures in place, then evolved into sanitary landfilling where waste is disposed under highly controlled conditions.

According to Dr Sean Finnigan CMEngNZ IntPE(NZ), Director of Environmental Engineering at engineering firm Fraser Thomas, changes in landfill design and operationshave been prompted by more stringent regulations and consenting requirements, developments in landfilling practice, and increasing environmental awareness and public expectations.

“Good landfill design now is a multidisciplinary approach involving different fields of engineering, including geotechnical, civil and environmental, and supporting disciplines such as structural, electrical and mechanical for plants and structures,” says Sean.

He cites the North Waikato Landfill, also called the Hampton PARRC (Power and Resource Recovery Centre), as an example of good landfill design. Located at Hampton Downs and built on more than 380 hectares of former farmland, the facility began operating in 2005 and is consented to dispose of 30 million m3 of refuse.

“It’s engineered to modern landfill standards,” Sean says, which includes a fully engineered containment system; a full leachate drainage, extraction and removal system; a full landfill gas control, extraction and monitoring system with landfill gas used to produce electricity; and an engineered final capping system to contain the waste materials, minimise rainfall infiltration which generates leachate and restores the land to productive agricultural use.

As long as people generate waste, landfills will continue to play a role in managing waste.

“The unfortunate reality is that the modern New Zealand lifestyle produces a lot of waste, of which a significant portion still ends up in landfill,” says Sean.

“If we have to create new landfills, then they need to be modern, engineered facilities designed to a very high standard so as to minimise potential adverse effects on

Left: Parul Sood, General Manager Waste Solutions at Auckland Council. Photo: Auckland Council Opposite: Ecogas Reporoa Organics Processing Facility will convert organic material into energy and bio-fertiliser.human health and the environment.”

Site selection is a critical first step when building new landfills, as evidenced by the Fox River landfill disaster of 2019 on the West Coast, where flooding exposed an old landfill on the riverbank, washing thousands of kilograms of rubbish out to sea.

“Avoid natural hazard areas, such as sites located adjacent to rivers or coasts or on significant overland flow paths or floodplains, and sites with significant geotechnical constraints or on fault lines,” says Sean.

Another consideration is PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), manufactured chemicals found in everyday products such as cosmetics, non-stick cookware and stain-resistant fabrics.

“PFAS have been called the ‘forever chemicals’ because they do not break down in the environment,” Sean says.

“Future landfill design may need to consider providing dedicated cells for known PFAS-containing wastes and for appropriate management and disposal of leachate with low-level PFAS contamination.”

Most importantly, however, engineers must incorporate sustainability when designing new landfills.

“Assess climate change effects, including risks from rainfall increases, more intense floods, sea level rise, river scour and coastal erosion.”

Sean continues: “Maximise landfill gas capture and collection – mainly carbon dioxide and methane – and use it to generate electricity or destroy it to stop it from entering the atmosphere and contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.”

Better alternatives to landfills are emerging, and engineers are at the forefront of these innovations.

“Most of the alternatives to creating new landfills are based on the diversion of relevant waste materials to other uses,” Sean says.

“Key to this is sorting waste materials into different categories and minimising cross-contamination.”

For instance, electrical, mechanical and software engineers at green tech startup ARCUBED developed OneBin, an AI-powered recycling bin that recognises and sorts waste at the point of collection to reduce contamination. Meanwhile, digital platform CiRCLR, cofounded by a software engineer, connects businesses with other businesses that can use their waste as a resource, thereby reducing the amount of waste going to landfill.

Sean says “As an environmental engineer, I fully support moves toward a circular economy and the 3Rs – reduce, reuse, recycle – with disposal to landfill being the least preferred option of the waste hierarchy.”

New Vice Chancellor of Te Herenga Waka— Victoria University of Wellington wants to make the University sustainable well beyond his tenure.

With a 125-year history, Te Herenga Waka— Victoria University of Wellington welcomed its 10th vice-chancellor in January. For Professor Nic Smith FEngNZ, this is the fifth university he’s worked at and he’s delighted to be back on New Zealand shores after two and a half years at the Queensland University of Technology as Provost (Chief Academic Officer).

“I was particularly attracted to this role at Te Herenga Waka because of the University’s ability and capacity to connect,” says Nic.

This sense of connection centres not just on the University, its staff and students but also on Wellington, Aotearoa and the world.

“I can’t think of a more important place to be working in right now.”

Nic argues that central to this importance are the series of existential crises we face as a society – such as climate change, social cohesion, healthcare – all of which need vigorous and well-informed discussion.

“Universities are an absolute necessity for these discussions, so it’s an exciting opportunity to lead an institution that can make a really significant contribution.”

His career aspirations weren’t always aimed at the tertiary education sector. Through his undergraduate days at the University of Auckland, he loved – and

still loves – solving problems. He had a passion for maths and physics. Not just for the technicalities but also because they became a framework for him to understand the world.

After working as a professional engineer at Fisher & Paykel, Nic completed his PhD at the University of Auckland in 1999 doing exactly that: using mathematical models to understand blood flow in the heart. The project was followed by academic positions at the universities of Oxford, Auckland and King’s College London. For more than 10 years he led work in the health space to bring new tools to existing contexts.

person. In Oxford, I worked with computer scientists, physiologists, politicians. And so walking into the faculties at Auckland was a great opportunity to create a platform for people to take on the big, high-risk ideas.

Topics on the agenda for Nic’s tenure at Te Herenga Waka include working towards gender equity, equity of access, biculturalism and sustainability.

“The higher education sector in New Zealand is under huge pressure right now. The question of how we sustain our key institutions is front of mind. People need to be able to see and plan on a longer timescale than just six months or one

“I was always looking for ways to make a difference,” he says. For example, in London, in his work with multi-scale and multi-physics models, he says: “We were asking how we can give the right patient the right treatment at the right time to get better outcomes.”

Returning to New Zealand in 2013 as Dean of Engineering at the University of Auckland was pivotal for Nic, who is a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand Te Apārangi.

“I’ve always been this interdisciplinary

year. So many of the key challenges we face require bringing diverse views and talents together for a sustained period. Universities are uniquely able to fill this role if they themselves have a stable foundation.”

Tikanga Māori and te reo Māori are also important.

“I really feel that starting to learn te reo Māori and tikanga Māori has given me a whole new lens and a whole new way of thinking about how we do the things that are important for moving institutions

I was particularly attracted to this role at Te Herenga Waka because of the University’s ability and capacity to connect.

forwards. It’s been a gift and I don’t mean that with any exaggeration. To be able to understand our society and community through a thoughtful and empathetic partnership is really crucial.”

Nic has begun his tenure listening to and working to understand staff, students and other stakeholders.

“One of the recruiting Council members said to me that when she looks at the strategic plan, she knows it’s in some of the heads of the University, but it’s not using all of our hearts. It’s a common theme I’ve heard, so I’d like to embed a vision and strategy that’s in all of our hearts.”

To achieve this goal, Nic says people must be prepared to ask the hard questions and to connect the vast capabilities of the University in a way that is excellent and relevant.

"And it is also my role to do everything we can to create a revitalised environment which allows staff to pursue excellence in teaching and research.”

While Nic is clear he doesn’t have all the answers to either the current challenges for the university sector or society more generally, he does have ideas about the state of play of engineering education in Aotearoa.

“Engineering is about technical ‘nuts and bolts’, but it’s also about using those tools to do the things that are significant in creating impact, rationalising uncertainty, navigating complexity and communicating to diverse stakeholders.”

Congratulations to our Engineering New Zealand Te Ao Rangahau members who were recently promoted to Fellowship and Distinguished Fellowship in recognition of their valuable contribution to the engineering profession. Here, we celebrate our three new Distinguished Fellows. >>

John Hare is recognised for his inspirational contribution to technical and executive leadership, especially in structural and seismic design.

John's appointment to numerous technical committees, investigation teams and governance groups reflects the respect with which he’s held within and beyond the profession. He’s been particularly effective raising awareness of earthquake and structural engineering design standards, especially following the Canterbury and Kaikōura earthquakes. John is a Life Member of the Structural Engineering Society and New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering. He has spent most of his professional career with Holmes in leadership roles in New Zealand and international offices.

How have you pushed boundaries in your career?

I was fortunate enough to grow up in an environment (both personal and then professional) that taught me the only limitations are those you impose on yourself. With that view, there are few boundaries and the only bad idea is the one that’s not expressed. Great engineering is fuelled by creativity and we should always be prepared to ask what we are doing and why. Then to think laterally, whether the context is applied design, business management or systems review.

I’d like to think that I have been able to apply that thinking to each of those, whether through structures I’ve been involved in, from sculptures to large buildings, or less direct engineering problems.

What has surprised you the most about your career?

Firstly, the realisation that it is possible to influence matters beyond what I would ever have dreamed possible as a young graduate, starting out all those years ago. Secondly, that “luck” will see you through – provided you understand luck is 90 percent effort and you make your own!

What do you see as the most pressing issues for Aotearoa’s engineering profession?

To maintain our relevance and standing in a world that is changing rapidly, whether socially, environmentally or technologically. A lot of what engineers have historically done may fall by the wayside as technology develops, putting more emphasis on the creative and visionary aspects of our careers. This poses challenges and opportunities for the profession as we embrace different skillsets and ways of thinking, making traditional training and learning potentially redundant.

Great engineering is fuelled by creativity and we should always be prepared to ask what we are doing and why.

Dr Kēpa Morgan (Ngāti Pikiao, Te Arawa, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu) is recognised for his contribution towards including Māori culture (tikanga) and Māori knowledge (mātauranga) into engineering education, and in establishing ways in which Māori can succeed in delivering engineering to benefit the wider community.

In the 1980s, Kēpa incorporated Te Ao Māori principles into his work to design the sustainable development at Whenuakura for his whānau, long before low-impact design was considered in wider engineering practice. His innovations also include alternative construction systems like Uku (a flax fibre and reinforced earth composite). Kēpa has been a role model in bringing cultural change in engineering education. His work has been shared and referenced in many spheres, nationally and internationally. It has extended and strengthened engineering through successfully showing how to integrate matauranga Māori with western knowledge and methods to create solutions and decision tools responding to the needs of Māori and others. Kēpa devised the Mauri Model, a decision framework to assist discussions and decisions about municipal water use that incorporate cultural considerations.

How will this recognition help you inspire other engineers?

This recognition signals the profession’s acceptance of the relevance of mātauranga Māori and acknowledges the as yet largely unrealised potential contribution that hapū can assist us with. This affirmation is important for Māori and Pasifika, and the entire profession, in dismantling the stereotypes and other barriers that limit the contribution possible from alternative ways of knowing.

What makes you different from other leaders?

My father was fearless and generous, my mother fiercely proud to be Māori and committed to enhancing the mauri of papatuanuku. My tupuna and past leaders of the profession have provided the guidance and support to persevere in the face of broad opposition when much easier options and opportunities beckoned. I have been resolute in my stance regarding the value and relevance of mātauranga Māori within my profession.

How do you keep learning as an engineer?

I am continuously learning from those around me and the different ecological contexts my work places me into. I do this in a reflective way as an uri of my tupuna Te Hikapuhi o Te Arawa, whose weaving is on display at Te Papa Tongarewa. My intention is to fully understand my surroundings so I fulfill my obligations appropriately and my contributions result in an enhanced state of mauri.

What has surprised you most about your engineering career?

That I became an engineer and that it is becoming easier to align engineering to be more relevant to indigenous ways of knowing.

I have been resolute in my stance regarding the value and relevance of mātauranga Māori within my profession.

Mike Underhill (Ngāti Raukawa) is recognised for his contribution to the engineering profession and the country’s electrical energy sector.

During his long career, Mike has raised awareness and kept a focus on issues related to the supply, delivery and use of electrical energy. He has influenced and enabled the significant changes in government policy necessary to ensure energy supply keeps pace with energy needs in a way that responsibly deals with the impacts of this key infrastructure. He has held key chief executive roles in the private and public sector in organisations including Energy Direct, TransAlta, WEL Networks, and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority. In his retirement, Mike serves as a Director for Network Waitaki, Electra, The Lines Company and Wellington Water.

What does this recognition say about your work? Regardless of the engineering sector you commit to, there are always opportunities to show leadership and, most importantly, to make a difference.

What makes you different from other leaders?

I always believed that everyone who worked for me had something unique to offer. When people genuinely believe you value them, their commitment and engagement increase significantly.

How have you pushed boundaries in your career?

I have found that by being well-prepared, you can argue your case and push boundaries. I was always surprised by how many people were not well-prepared.

What keeps you motivated in your work?

My work is now mainly governance so it is the ability to mix and match your learnings and experience with new ideas and environments, providing useful governance judgement and advice.

How will this recognition help you inspire other engineers?

It’s about seeing a lifelong relationship with engineering which sometimes seems a challenge and can certainly be daunting to young engineers. As your maturity and experience grows, so too does your ability to deliver greater and wider outcomes and also to be recognised.

What do you see as the most pressing issues for Aotearoa’s engineering profession?

It’s not recognised for its very valid professional views on many of the major issues that New Zealand faces today. We need more authoritative leaders in our profession.

When people genuinely believe you value them, their commitment and engagement increases significantly.

Celebrating our engineers who go above and beyond.

6pm Friday 24 March

Banquet Hall, Parliament

Tickets on sale at engineeringnz.org/fellows

Reinstatement of a waterway that had existed prior to the construction of a causeway in the 1960s.

WSP, Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency, Fulton Hogan, Far North Roading Group, Spirals Drillers Ltd, BUSCK Prestressed Concrete Ltd, Aputerewa Marae – Helen Larkin, Kenena Marae – Lydia Lloyd Pukenui No. 2 Block Trust – Peter Kitchen

State Highway 10, approximately 2km south of Mangōnui in the Far North

May 2021 – April 2022

– 2022 IPWEA Annual Excellence Awards, Best Public Works Project $2M - $5M.

– 2022 IPWEA Excellence in Environmental Sustainability

– 2022 IPWEA Supreme Asset Management Excellence Award

– Shortlisted for CCNZ awards and NRC Environmental Awards

An innovative, collaborative project to replace a 1960s culvert has led to restored water flow, revitalised wetlands and flood reduction.

A causeway, built in the 1960s to replace a failing bridge on State Highway 10, had turned what was once a freeflowing river and food source for tangata whenua into a mangrove swamp. The tidal flow of Northland’s Mangōnui estuary was restricted, which reduced the quality of the marine environment, took land away from tangata whenua and blocked easy access to the water.

Three hapū were instrumental in bringing the deteriorating environmental condition of the waterway to the attention of Waka Kotahi. Discussions began between tangata whenua and Waka Kotahi to seek a solution to restore the natural marine waterway around State Highway 10 south of Mangōnui and to help the ecology to flourish once more.

At first, there were detailed designs to create a box culvert replacement solution. But discussions soon revealed the proposed culvert and channel clearing were not a practical solution and a bridge would be more effective.

“There was a cost-time challenge with this work,” explains Shaun Grieve CMEngNZ, Principal Geotechnical Engineer/Team Leader – Civil at WSP.

“There was a fixed budget, and construction needed to start by the end of August 2021 for the funding to be retained through the Provisional Growth Fund. We wanted this construction to occur with minimal disruption to the Far North community and maintain the level of service expected for a State Highway.”

The real breakthrough came, says Shaun, when the majority of the temporary works (to install the foundations for the originally planned culvert) became the solution for the permanent works.

“We had already dug a large hole and installed two retaining walls, below sea level. From there, through early contractor input (ECI), it was straightforward to construct a simple bridge, with a floating braced structure, using an existing supplier’s bridge deck to define the bridge length.”

Shaun, along with WSP Civil Engineer Kathleen McMullen MEngNZ and the company’s design management team were able to then quickly do the design checks required to ensure a fast turnaround.

The retaining abutments were changed from secant piles to sheet piles, meaning wins for cost, embodied carbon and reduced environmental risks.

“It took collaboration at every stage of this project to reach this innovative solution,” says Shaun.

“In a sense, the construction methodology was fairly standard, but it was the involvement of all parties –ourselves [WSP], Waka Kotahi, Fulton Hogan and the local community – at every stage of the project that makes this project so transformative.”

Sarah Whitehorn MEngNZ, Project Manager at Fulton Hogan, agrees, saying the success of the project was due to trusting relationships and open dialogue.

“This allowed ECI throughout the design, development and delivery stages. Everyone pulled together to improve constructability and an efficient programme for delivery.”

Within a couple of days you could see the mullet start to frolic, herring swimming upstream, and heron, shags and wading birds feeding.

– Sarah WhitehornAbove: The original culvert prior to construction of Tokatoka Bridge. Photo: WSP Right: Aerial view looking north. Photo: Aerial Vision

Another pivotal success factor was the partnerships with tangata whenua. The two local marae and the Pukenui No. 2 Trust (owning the quarry adjacent to the site) provided kaitiaki or guardianship throughout the project.

“Waka Kotahi held a hui before any design works commenced to understand the cultural narrative and to determine the best solution with the allocated budget,” says Kathryn O’Reilly, Senior Project Manager (Complex) at Waka Kotahi.

“We all had trust that everybody was doing their best to achieve a positive outcome for the project.”

The collaboration extended to the borrowing of materials and access to those materials, with one hapu allowing materials to be taken from their quarry and dredging materials to be placed at the site. The Trust’s future vision for this land includes a native plant nursery and whare wānanga to teach youth about mahinga kai in the area.

“The construction team shaped the quarry for this future vision,” says Sarah.

She says the project was approached with care from start to finish, with tikanga including daily karakia.

“The day we ‘broke through’ creating the connection for the tide under the bridge, nature’s response was almost immediate,” says Sarah.

“Within a couple of days you could see the mullet start to frolic, herring swimming upstream, and heron, shags and wading birds feeding.”

Iwi are most proud that after nearly 50 years, the mauri of the awa has been restored, bringing life back to the communities surrounding the Tokatoka awa.

“The final product seems to be attracting fish and preying birds, which proves that it is achieving its purpose,” says Mike Erihe from Aputerewa Marae.

“Thanks to all the staff involved, we now have a structure that will be an absolute asset for those who now can fish there.”

“The fish have returned to the awa,” says Kathryn. “It is a beautiful sight to see this after over 40 years of nothing. The awa has come back to life. There is an energy present, and it is wonderful seeing that after such a long time.”

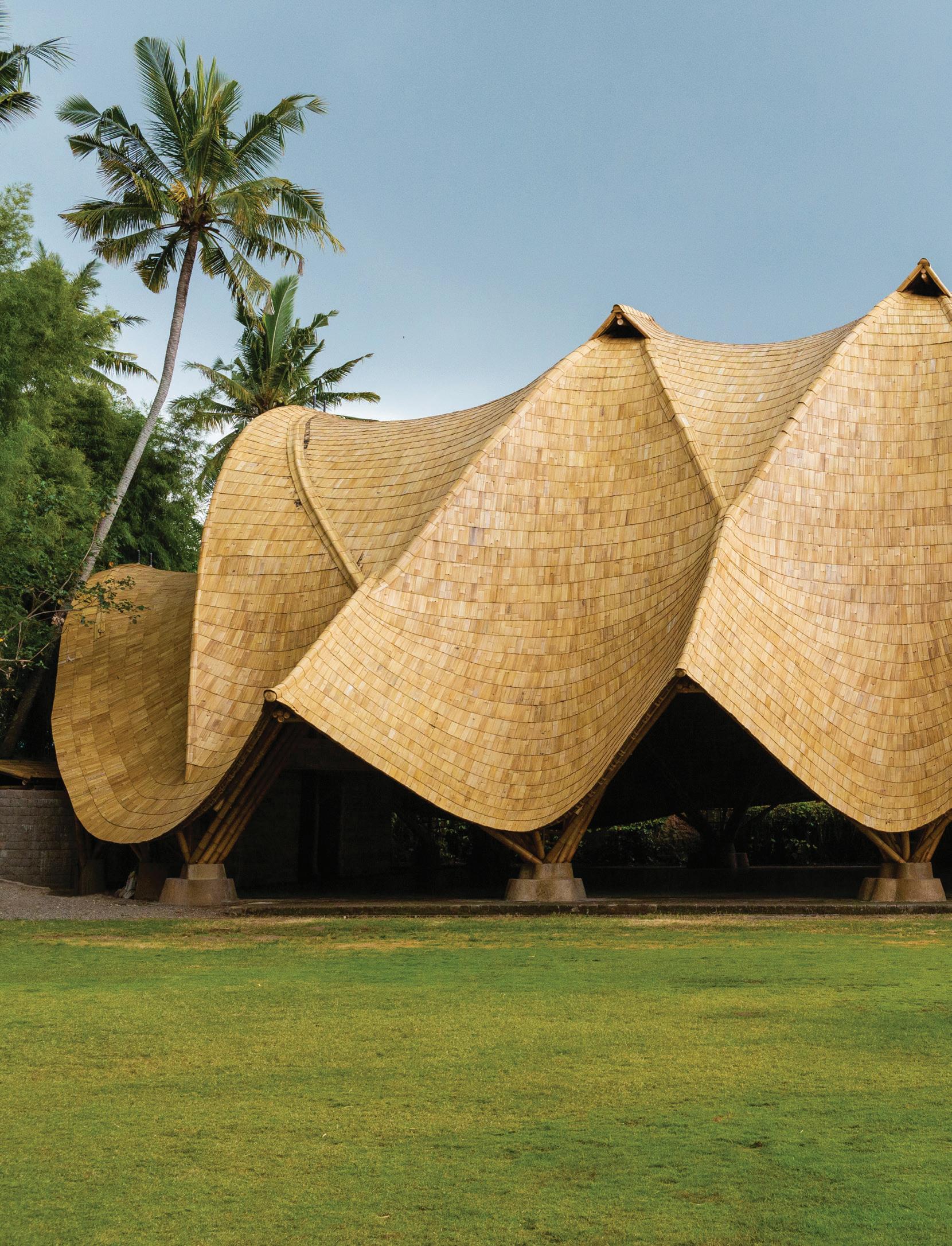

by Bamboo

School founders John and Cynthia Hardy's daughter Elora Hardy and her studio Ibuku, in collaboration with bamboo architect Jörg Stamm and structural engineering firm Atelier One, and constructed

bamboo, using its unique combination of strength and flexibility. Anticlastic shells span between 19m wide by 13m high arches, contributing to the structural spanning. The Arc was designed by Green

solutions. Green School Bali’s gymnasium, The Arc, won the Supreme Award for Structural Engineering

Excellence at the IStructE 2022 Structural Awards. The project demonstrates the structural use of

It sounds idyllic: a nature-immersed campus with no walls, set in the jungles of Bali, Indonesia, where “changemakers” aged 3–18 learn in a centre for experimentation, innovation and

Pure. Photo: Tommaso Riva

For many of us, imagining the future is fraught with such complexity it can be an overwhelming exercise laden with our own life experiences and biases. But for futurist and engineer Dr Kristin Alford, it’s a discipline where she can utilise her multifaceted background to interrogate, and help others plan for, possible futures.

“Futures thinking sits at the intersection of design and strategy,” says Dr Kristin Alford. “It is related to strategy, because you’re trying to anticipate future opportunities and look at how to bring those into the present, but it’s also related to design, because we’re thinking about how to create and work within constraints.”

With degrees in mineral processing engineering, philosophy and management, and her eclectic career in education, human resources, strategy and communications, Kristin led the vision, design, and delivery of the University of South Australia’s Museum of Discovery (MOD). It’s Australia’s first future-focused museum, and she is its inaugural Director. The museum aims to provoke new ideas at the intersection of science, art and innovation, acknowledging that STEM subjects – science, technology, engineering and mathematics – will be intrinsic to many jobs in the future.

“My particular interest is in helping to build people’s capability to do future thinking better. Our aim is to inspire young adults to be able to navigate not only their personal career futures, but also the type of world that they are moving into and creating.”

Kristin says moving from engineering to museums was a natural progression.

“It’s all about using processes and frameworks to engage people in ideas, thinking about inputs, outputs, change and transformation. And from my experience in people management, strategy and science communications, I’m focused on how to land some of those concepts with an audience and engage people in the ideas.”

Futuristic thinking is vital for the engineering profession, she says.

“Engineers are literally building the future, whether they’re creating processes that bring materials to life or designing buildings. It’s very important engineers are thinking about the types of impacts their work is going to have.”

Circumstances, however, often prevent such foresight.

“If you’re in an engineering firm or in government, you’ve got pressure to deliver, and to deliver now. You don’t always have a community understanding why you

might be talking about something that’s 20 years down the track.”

Does she recommend engineering firms engage a foresight consultant?

“I know a lot of construction companies that have active foresight units within them, to ensure buildings will be as fit for purpose in 40 years as they are today. There’s also an appetite for better future thinking in some of the resource companies, because as we phase out coal, we are looking at greater electrification and renewables and need to look ahead.”

She says future thinking is very important if you’re dealing with natural systems, such as forestry, where there are long-term impacts from the decisions that engineers are making today.

“We’ve seen rapid change in the past 10 years. So, what might the next 10 to 20 years look like? How do we make sure that our decisions are robust and going to last?”

She says: “By thinking through possibility, we can better anticipate disruption and we’ve got a better set of tools to be able to respond to disruption.”

In September, Kristin will address the 19th International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES19), discussing the future of work in science

WRITER | KAITUHI ALEXANDRA JOHNSONand technology, and the factors to consider as we seek to discover and develop innovative solutions. She sees huge value in women in STEM disciplines coming together to create large global networks.

“There’s enormous power in that, and in the shared experience.”

But she is also exasperated that the circumstances for women in STEM disciplines remains challenging.

“Women in STEM often end up working to increase diversity and not doing the actual STEM work. But it’s not a women’s problem, it’s a men’s problem – it’s the system that needs to change. When you see better diversity in certain organisations, it’s because it is treated as a priority, as something that’s actually going to drive business and sustainability.”

Kristin says: “I graduated 30 years ago but haven’t really seen the needle move. I’m still answering the same questions.”

She says the profession needs engineers who have global mindsets and who are as interested in complexity and in social and ethical issues as they are in the maths and science.

“Young women often have high marks across a wide variety of subjects

and might need a little bit more of encouragement to think about engineering, because they have a lot of choice. We need these types of people in the discipline.”

So as a professional futurist, what’s her main concern?

“It’s our inability to act fast on climate. For example, we’re worried about the immediate effects on people if we transition out of coal. But the effects on people in 10 years’ time are going to be horrendous if we don’t do it. We just don’t seem to be able to grasp that.”

She says to manage climate, a new system of capitalism is required.

“I’m a big fan of Kate Raworth and doughnut economics and thinking about how we live within our biophysical systems because that addresses all of those sustainable development goals and reorganises the way we think about value and money.”

What hope does she see?

“We recently did a workshop with MOD visitors and stakeholders and everybody said how broken everything is, the education system, capitalism and democracy, all seem broken.

“We are experiencing more viscerally that the system isn’t in service to us as humans. But there seems to be some thinking about regenerative economics and I think that is a really bright spark for the future.”

The 19th International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES19) will be held in Auckland from 3-6 September, co-hosted by Engineering New Zealand Te Ao Rangahau. Find out more and register at ICWES19.com

Engineers are literally building the future, whether they’re creating processes that bring materials to life or designing buildings.

With a new year now well underway, it’s a good time to revisit and reflect on the lessons we’ve learnt from the engineering profession in the past year and consider what they can teach us in the year ahead.

An all-too-common issue the legal team has seen is miscommunication around the scope of a job. It is critical to agree in writing where your role as an engineer begins and ends. Do not overpromise. Make sure you completely understand the client's needs. Prepare a written brief that is agreed by all parties and keep it on file. This will prevent a common complaint we see, where an engineer carries out work that does not go as far as the client expected. We suggest writing to your client outlining what the scope will not include, in case there is any future disagreement. Keep your scope clear and concise for clients – “engineering language” is not for everyone and you can avoid confusion by using simple, plain language. When you and the client have reached an agreement, formalise the scope in a legally binding contract. We recommend using the short-form agreement template free for you to access at engineeringnz.org

There has been a lot of change in the industry. Keep an eye on what is coming into force and how this may affect your work. You can complete a range of business and technical training for

a rich and diverse skillset that reinforces your competency. Te Ao Rangahau has excellent professional development resources, CPD opportunities and courses available. The Code of Ethical Conduct requires you to only work within your competence and ensure your knowledge and skills are kept up to date.

The work you do is important to the profession. If you see something that doesn’t look right, speak up. Last year, some significant disciplinary decisions arose from engineers who raised concerns about other engineers’ work. Without their curiosity and concern, it’s possible engineering errors could have gone unquestioned and the safety of the public could have been at risk. The disciplinary decision of Joo Cho is an example of this. From a street view, a graduate engineer spotted issues with Mr Cho’s work on an eight-storey office building. A council review found the work did not comply with the Building Code. Mr Cho has since been removed from the register. You can read the full decision on our website.

You are responsible for reporting any engineering matters that may have adverse consequences. This includes any risk of significant harm to people’s health and safety. Please fill out a Raising Concerns form on our website if you come across any work that poses a risk to the public or the environment. You should also consider alerting any relevant authorities.

If the complaint is about you: engage early and engage well

Having a concern raised about you with Te Ao Rangahau can be stressful. Take comfort, you’re not the first to go through this and you won’t be the last. We’re here to help you understand the process and we do that best when engineers engage early and engage well. Please respond to our emails, return our phone calls and try not to put it in the too-hard basket. We want to hear your side of the story. The quality of engagement by an engineer may factor into the severity of a disciplinary order. Being pre-emptive and proactive in the complaints process will also save you time and energy. Often, we can help you resolve complaints at an early stage if you are willing to be open and forthcoming. We strongly encourage you to accept any opportunities for mediation or alternative dispute resolution; this may help resolve matters before they reach a disciplinary stage. For more information, please see the Practice Notes and the Managing Complaints Handbook at engineeringnz.org

Laura Sturch is a Legal Advisor at Te Ao Rangahau.It’s a pivotal time for heavy vehicle certifying engineers. As the sector’s representative group works with its regulator to strengthen the operating environment, it’s also helping address a serious shortfall of people entering the profession.

Heavy vehicle certifying engineers are authorised by Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency to assess the safety of New Zealand’s heavy vehicle fleet. Heavy vehicles are classed as trucks, trailers, motor homes and buses weighing at least 3.5 tonnes, and there are roughly 150,000 of them on our roads. Hayden Ringrose MEngNZ, Chair of Heavy Vehicle Engineers (HVE), a Technical Group of Engineering New Zealand, is passionate about the work and says it offers good variety.

“You can be designing brand new stuff, pushing the envelope on trailer design to maximise payloads for people with complete trailer and truck setups. You could be heavily involved in the repair side of the industry or be involved in what is probably the most in-demand portion of the industry and delve into brake systems.

“The role could be mainly deskbound, nice and clean, or you can spend the day like I do – in overalls crawling around under trucks and trailers, working in workshops with tradesmen, sorting out repairs. I thoroughly enjoy the dirtier side of it.”

HVE works closely with Waka Kotahi, the profession’s regulator, on the development of standards and other regulatory requirements. Hayden, as HVE’s

Chair, and the group’s committee, have regular discussions with Waka Kotahi on regulatory matters and so they can attempt to get ahead of issues “before they turn into something bigger”.

“We’ve got a good line of communication with Waka Kotahi. While there are challenges, it’s a good working relationship and there’s an appetite within Waka Kotahi to approve practical solutions to the industry’s challenges.”

The conduct of several heavy vehicle engineers has put the spotlight on regulatory issues within the profession recently. In one more high-profile case, an engineer was removed from the Chartered Professional Engineers’ register and fined for designing and certifying a towing connection that led to a trailer separating from a truck travelling at speed along a highway. An Engineering New Zealand disciplinary committee found he breached the Code of Ethical Conduct by acting negligently. In 2018, an enquiry into Waka Kotahi over compliance concerns resulted in the suspension of several heavy vehicle certifiers. Hayden says Waka Kotahi’s response to the enquiry was to swing the pendulum from slightly too lax to too hard.

“In the past there has been quite a heavy-handed approach to regulation, and that has caused some problems for us. That’s starting to back off to a more reasonable approach to the oversight.”

A lack of engineers entering the profession is also causing concern. Numbering around 180, the pool of heavy vehicle certifying engineers

in New Zealand is already small. A good portion of that number is dedicated to specific manufacturers, leaving a limited number available to the wider transport industry and general public.

“We are massively under-staffed and our members are aging. A couple of years ago, HVE identified that our group demographic had more members aged over 55 than anything else. The attrition due to retirement was also looking quite scary.”

Hayden says while the number of people entering the sector has improved over the past few years “ ...we face quite a serious shortage of certifiers”.

The minimum requirement to enter the industry is a Diploma in Engineering (Level 6) and engineers will typically have an honours degree in Mechanical Engineering. HVE is working closely with Waka Kotahi and Engineering New Zealand on a programme to develop training material for people being certified.

“We’re developing an improved curriculum, training resources and modules that include all the base knowledge required to make entry easier. The programme guides new entrants into the industry along a pathway that will reliably allow them to become heavy vehicle certifiers.

Hayden says heavy vehicle engineering offers the full spectrum of work for people coming into the industry, including a variety of workplace environments, and not just in the main centres.

Since New Zealand’s oldest engineering consultancies opened their doors more than a century ago, they've seen huge social and economic change. To last the distance, they’ve adapted and grown, embracing both challenge and opportunity.

Beca traces its beginnings back to 1920 when William Arthur Gray, known as Arthur, returned from military service and purchased a structural engineering practice. For the first few years he worked as sole practitioner, taking on water reticulation, roading and drainage projects in the upper North Island region. Before the war, Arthur had completed a Master of Science in mathematics at Auckland University College and had worked as a civil engineering assistant for the New Zealand Railways Department. In 1920, when he began his business, anyone could set up shop as an engineer. The profession was unregulated, but this was soon to change. The forerunner of Engineering New Zealand, the New Zealand Society of Civil Engineers, was established in 1914, aiming to raise the status of the profession and promote continued education and professional development. The Society pushed for a system of registration. The resulting Engineers Registration Act 1925 created a Registration Board and the title “Registered Engineer”. To apply for registration, applicants had to have suitable qualifications and experience and be of good character and reputation. Arthur was a member of the Society and

was among the first engineers to be registered under the Act.

Some of New Zealand’s other longstanding construction and engineering consultancies trace their beginnings to the late 1940s–1950s. Urban expansion in the post-War period led to a building and infrastructure boom. Developments in dairy and forestry also provided opportunities for new players.

Fred Hawkins founded Hawkins Construction in 1946. The company’s first projects were housing contracts, but Fred’s heart lay in commercial building, and through the 1950s the company took on contracts for the NZ Co-operative Dairy Co and NZ Forest Products. By 1962, Hawkins had completed 10 dairy factories, three boiler houses at the Kinleith pulp and paper mill, and numerous other houses, shops, schools and factories.

Tonkin + Taylor was another company to grasp opportunity in the 1950s. Ralph Tonkin and Don Taylor met in 1956 and established Tonkin + Taylor, Consulting Engineers in 1959. Together they grew the company through the 1960s. Some of the company’s notable early projects include the lower Waikato River stopbanks, investigations for the Marsden Point Oil Refinery, and the Whau Valley Dam for Whangārei’s water supply.

The post-War period offered new opportunities for Beca too. It grew and picked up major projects such as the structural design for the grandstands at Eden Park and Ellerslie Racecourse, and the engineering design of the iconic

eight-storey, high-end retail and hospitality space at 246 Queen Street in Auckland.

The second half of the 20th century brought new challenges to the engineering profession. Growing environmental awareness from the 1960s placed new scrutiny on the work of engineers and forced the profession to turn a more critical eye upon itself. Conversations about engineers’ ethical, social, and environmental responsibilities began to resound throughout the professional body and grew in volume through conferences led by the New Zealand Institution of Engineers’ branch and technical interest groups. It was the beginnings of change more fully realised decades later with the passing of the Resource Management Act in 1991. Deregulation and the privatisation of many government agencies that employed engineers shook up the sector in the 1980s. The newly formed entities had to learn the balance between reinvention and building and retaining industry knowledge – a skill that long-established engineering consultancies had been honing for some time. The 1970s and 1980s were a time of change for private companies too. Beca and Tonkin + Taylor extended their business interests and expertise to international projects, and Tonkin + Taylor and Hawkins moved through different ownership models. Perhaps if there is one key to longevity it is adaptability.

Cindy Jemmett is Heritage Advisor at Te Ao Rangahau.

Neurodiversity is a term coined by Australian sociologist Judy Singer in the late 1990s to describe neurological differences in the human brain. To date, it has generally been viewed as a disability by the medical sector. But the neurodiverse could be part of the solution to improving productivity and innovation for businesses.

How our brains are wired impacts on how we process and experience the world around us. Different thinking and different emotions drive different types of behaviour. Everyone’s brain wiring comes from learnt experiences – what we are born with, our genetics and how we’ve developed over time. Even though we think we all live in the same world, we don’t. We all live in our world. We filter the world all the time based on our brain wiring. Ultimately, there is no “normal” brain wiring – we all have different brains and are all, to some degree, neurodiverse with a little “n”. When we understand how we tick, and what makes other people tick, this enables everyone to “get” each other, leading to higher performing teams.

Neurodiversity, differentiated here with a big “N”, includes ADHD, ADD, autism, dyslexia, OCD and many more, which do mean thinking and making decisions differently. It’s important to know that

approximately 40 percent of your current workforce will most likely be Neurodiverse. The good news is that what is good for the Neurodiverse is good for neurotypical people too.

When recruiting, we need to be aware of the challenges of this brain wiring as people may also have significant lifeinterrupting challenges. For example, difficulty reading and understanding social cues, which often leads to social awkwardness, social isolation, anxiety, depression and far too often, suicidal ideation. People can be sensitive to light, sound and touch, and might find strong foods or noises completely overwhelming.

Currently, many businesses recruit people who reflect themselves – we’re attracted to people who behave in a way that is familiar or useful to our world view. Therefore, we can often focus on the negative and discount people who don’t present in that traditional, expected way. We might dismiss a candidate who seems scruffy or vague, doesn’t maintain eye contact, has a limp handshake or makes us feel uncomfortable. But we could be turning down the next Steve Wozniak, or someone with autistic strengths making them gifted at analysis or with memory or learning or processing information.

It's World Autism Awareness Day

on 2 April, with the aim of recognising and spreading awareness of the rights of people with autism. Skills such as being data driven can come easily to people with autism, but they may be paired with controlling traits. It’s important to understand brain wiring and how the environment can support underused and overused strengths. Sadly, despite having amazing talents, autistic candidates are often either unemployed or underemployed, due to traditional recruitment methods.

In this competitive job market, traditional recruitment procedures can decrease your candidate and skills pool. Welcoming Neurodiverse candidates means a bigger and more productive (autistic brain wiring) and innovative (ADHD brain wiring) candidate pool. There are different barriers for job seekers depending on brain wiring, but removing these has significant benefits as JPMorgan Chase & Co demonstrated: autistic employees can be 40–138 percent more productive in a well-supported, neurodiversity-educated workplace, as they do not focus on social interactions. Autistic employees can also onboard in half the time of neurotypical employees with good systems and processes in place.

When we take an innovative and neurodiverse approach to recruitment,

we will ensure greater job and business success when we can identify best brain wiring for roles; write job descriptions and ads to attract Neurodiverse candidates; create assessments for this brain wiring while being conscious of biases; onboard in a way that best suits brain profile, ensuring greater retention and success for the individual, team and organisation.

The first step is to educate employees about neurodiversity. Like all change initiatives, to ensure success they must be driven from the top. This is what the NQ (Neurodiversity) Pledge divergenthinking. co.nz/nqpledge does. It’s a values-based undertaking for CEOs to visibly demonstrate commitment to creating true psychological safety, visibility and inclusion of Neurodiverse individuals in the workplace and community.

Then take a neurodiverse lens to your business strategy, KPIs, procedures, support tools and communication methods. The NQ Stocktake divergenthinking.co.nz/ nqstocktake can help you with assessment and recommend how you can foster a sense of belonging for all employees.

With 25 years in learning and development and a recent ADHD and dyslexia diagnosis, Natasya Jones co-founded DivergenThinking to create opportunities for neurodiverse people. divergenthinking.co.nz

Ultimately, there is no “normal” brain wiring – we all have different brains and are all, to some degree, neurodiverse with a little “n”.