Kalkarindji/Wave Hill

Ancient Aboriginal rock art in Kakadu and Arnhem Land depict the Dreaming legends of the oldest living culture in the world.

Credit: Tourism NT/Let’s Escape Together

Take time out from busy adventuring to pamper yourself in one of the many thermal hot springs, like those at Mataranka.

Credit: Tourism NT/@helloemilie

The thundering spectacle of Kakadu’s Jim Jim Falls is best seen from the air during the wet season.

Credit: RAN - Historical Collection

In February 1942, WWII came to Australia’s shores at Darwin and affected many other towns in the Top End.

Take a cruise in the awe-inspiring Katherine Gorge and be amazed at this geological marvel of the Nitmiluk National Park.

Credit: Tourism NT/Elliot Grafton

Sculpted over 2500 million years, this ancient land is still evolving.

The Top End has a long and complex geological history. It began more than 2500 million years ago (mya) with the formation of Australia’s continental plate as part of the earth’s crust. The granites and gneiss that form this ‘basement’ layer are some of the oldest rocks on the planet. They underlie most of the area between the South and East Alligator Rivers north of Cooinda and are now exposed as small bare domes at the edge of the floodplains.

During 500 million years after its creation, the plate sagged creating the region’s main geological structure, a deep trough underlying 66,000sq km from Darwin south to Pine Creek and east to Milingimbi on the central Arnhem Land coast. This vast depression gradually filled with layers of sediment to a depth of 14km and was then intruded by seams of volcanic magma. One of these strata-bound layers contains most of the uranium deposits of the Alligator Rivers region.

Tectonic forces crumpled, fractured and uplifted the layer and changed some rocks into more granites through extreme heat and pressure. Yet more volcanic activity

overlaid a 22,000sq km sheet of dolerite and basalt up to 250m thick. This was later eroded back to a gently undulating plain with isolated hills and ridges up to 250m high.

The story doesn’t end there. About 1650 mya, hundreds of metres of sand and gravel were deposited across this eroded surface, to form what we know today as the Arnhem Land Plateau. For millions of years the Plateau’s 500km escarpment was a cliff against a shallow northern sea. This eroded to expose the spectacular sedimentary layers visible today in western Arnhem Land.

More recently, during the past 110 million years, more tectonic forces gradually pushed up the land, exposing the sandstone layers to weathering and erosion by massive rivers. These scoured, carved and moulded the Top End landscape into its present form. The rivers deposited sediment in the valleys and basins of the northern plains, creating a gently undulating alluvial lowland stretching from Darwin to Kakadu and into Arnhem Land. The estuarine mangroves and freshwater wetlands of the South Alligator system are distinctive features of this modern coastal fringe.

The complex geological history of the Top End has created a wide range of landscapes. Some of the more significant ones are described here in subregions.

Arnhem Land coast

Arnhem Land contains almost 96,000sq km of northeastern Northern Territory. Its coastline faces the Arafura Sea to the north and the Gulf of Carpentaria in the west. The Van Diemen Gulf borders the east Arnhem Land coast, which is heavily indented, especially around the Cobourg Peninsula The central north Arnhem coast is incised by the estuaries of the Liverpool/Mann River and the Cadell/Blyth River systems. The northeast coast around the Gove Peninsula is a series of bays guarded by numerous fringing islands and Groote Eylandt in the Gulf.

Arnhem Land Plateau

The Arnhem hinterland is one of Australia’s largest untouched wilderness areas, incorporating the rugged Arnhem Land Plateau. This sandstone massif straddles most of West Arnhem Land, with long talus slopes mantled by debris of massive rocks. Its highest point is Kub-O-Wer Hill (570m). The plateau surface has been stripped of soft rock and soil to expose bare pavements crisscrossed by joints, faults and dolerite dykes. These have deeply weathered into a maze of narrow valleys and gorges. The porous sandstone acts as a huge aquifer with springs that feed waterfalls along the escarpment. Many watercourses, including the Alligator Rivers, originate in this way.

Much of East Arnhem Land is relatively flat. There are some disconnected ranges which direct surface run-off to feed numerous watercourses. At 8280sq km, the Liverpool River catchment is the largest tidal river system in Arnhem Land. Joined by its two major tributaries, the Tomkinson and Mann Rivers, the estuary flows into the Arafura Sea, southwest of Maningrida. To the east, the Cadell and Blyth Rivers combine to inundate a 430sq km floodplain with over a metre of water during the wet season. The Goyder River begins as a spring at the base of the Mitchell Ranges, southwest of the Gove Peninsula, and meanders generally northward in braided channels that flow into the Arafura Swamp. This near-pristine wetland expands to 1300sq km by the end of the wet season, making it one of the largest wooded swamps in the Territory. The swamp is drained by the Glyde River into Castlereagh Bay.

The eastern border of the Kakadu National Park follows the sheer escarpment of the Arnhem Land Plateau and the western rim of the Bulademo Tableland (Marrawal Plateau). South of Jim Jim Falls, the park takes in the South Alligator River valley. Low undulating plains stretch from the Arnhem Land escarpment to Darwin, sloping gently northwards to the sea. A large number of roughly circular depressions (dolines) occur throughout the plains. Many of these form seasonal billabongs and permanent waterholes. The lowlands merge into an extensive floodplain system with wide swinging river meanders, oxbow lakes and billabongs. Wet season flooding may inundate these coastal plains for three to nine months, depositing a fresh layer of silt. Mangroves fringe mudflats at the mouths of tidal rivers and creeks.

These low-lying coastal plains are drained by several rivers, including the South and West Alligators, the Wildman, the Mary and the Adelaide, which flow north into the Van Diemen Gulf. All but the Mary and the Adelaide have headwaters in the sandstone plateau region to the east and south. Their upper reaches typically follow deep, narrow clefts and form spectacular waterfalls, such as Jim Jim and Twin Falls. After leaving the plateau, the rivers enter the low coastal plains. Here they broaden into braided alluvial channels and link billabongs, and during the wet they can overflow into adjacent swamps. Their estuaries are relatively narrow tidal channels reaching in from the sea, with banks formed by silty levee banks fringed by mangroves and monsoon rainforest.

The Mary River rises about 50km east of Pine Creek and, with its tributaries, drains a catchment of more than 8000sq km. Nevertheless, it only flows in the wet season and is little more than a series of pools and billabongs in the Dry. The Adelaide River originates in Litchfield National Park and flows 248km before discharging into Adam Bay on the Clarence Strait. The two rivers’ adjoining floodplains form a wetland covering 2700sq km known for its high concentration of saltwater crocodiles, barramundi and waterbirds. Bordering Kakadu NP, the East Alligator River rises in the northern part of the Arnhem Land Plateau and drains a catchment of almost 16,000sq km on its way to meet the Van Diemen Gulf in a huge tidal estuary at Point Farewell.

LEFT: Moonrise over Nourlangie Rock and the Arnhem Land escarpment (Credit: Tourism NT/@helloemilie) BELOW: Lowland floodplains (Credit: Tourism NT/Peter Eve)

Your

Careful preparation will help to maximise your enjoyment of this awesome experience.

The ‘6 Ps Principle’ — Proper Preparation Prevents Pretty Poor Performance — is a good rule of thumb to apply to an adventure in the Top End, which will take you into places that are exotic and exciting but also challenging and remote. Time spent in careful preparation will stand you in good stead and help maximise the enjoyment of this awesome experience.

Pre-trip research will yield lots of practical information and give you some insight into the region you’re about to explore. We’d like to think that the book you’re reading right now is the best general-purpose guide for the adventurous traveller. Other references can be found at your local library and in 4WD and outdoor sports stores. Tourist information centres and national park bodies can also provide brochures, maps and fact sheets, many of which are available online. Maps are invaluable in planning any trip and a portable resource to carry with you. As most travellers begin their journey to the Top End from the southern and eastern fringes of the continent, they might traverse some remote outback deserts along the way. Hema’s Great Desert Tracks series (1:1,250,000) provides vital track information to guide you through these amazing landscapes. Once you’re in the north, Hema’s Top End and Gulf map (1:1,650,000) has loads of useful information, including GPSsurveyed roads and tracks, magnified insets for Kakadu and

other national parks, camping areas, fuel stops, points of interest and contacts.

Your travel experience in the Top End can vary greatly depending on when you go. Broadly speaking, northern Australia experiences a hot, monsoonal wet season that can last from late-November to mid-April, followed by a long spell of mild, dry weather from around May to the ‘build up’ in October.

During the Wet, floodwaters will greatly restrict where you can travel. While main bitumen highways are generally open, many minor roads are closed and some places near the coastline are subject to tropical cyclones. Once the rains begin, it’s best to avoid muddy, out-of-the-way tracks. That said, the wet season can be very dramatic, with thundering waterfalls, masses of birdlife and widespread re-greening of the landscape. If you can tolerate the heat, humidity and mozzies, it can be quite spectacular and well worth the effort.

In April/May, there’ll still be plenty of water about and creek crossings will be deep. Make sure you have a wellprepared, high clearance vehicle and your driving abilities are up to the task. Some tracks and camping areas may remain closed until May/June and it’s a good idea to check opening dates on NT transport and national park websites.

Not surprisingly, most travellers head to the Top End during the Dry, and that’s certainly the most comfortable time

of year. The only real downside is the possibility of missing out on a camping site at some of the more popular spots, particularly in national parks. To avoid this, you’ll need to book well in advance (6–12 weeks in some areas), and steer clear of the Easter break and school holiday periods. By September, everything will have dried out a lot, temperatures will be climbing and most of the Top End will be accessible, including 4WD tracks.

Darwin is the most northerly of Australia’s capital cities, and yet getting to it is relatively easy. Regular interstate flights reach Darwin International Airport from other state capitals, and airports at Katherine and Tennant Creek are served by small domestic operators. Described as one of the world’s great rail journeys, The Ghan runs weekly between Darwin and Adelaide (almost 3000km) in a scheduled travelling time of about 53 hours, including extended stops at Alice Springs and Katherine allowing time for passengers to take optional tours. The Inlander passenger train operates twice weekly on the Great Northern line from Townsville to the mining city of Mount Isa, completing the overnight journey of 970km in a leisurely 21 hours. From Mount Isa, travellers wishing to continue their trip to the Top End must do so by road.

The Northern Territory is permeated by a network of roads, including two national highways, linked to adjoining states and connecting major territory population centres and tourist destinations. Away from the highways, bitumen roads are all-weather and passable year-round, except during brief periods of flooding. They are generally in good condition, although some may be narrow and have sharp, deep drops to gravel edges along the tarmac.

Off the beaten track, most minor roads are unsealed, although some sections may be paved with tarmac. Their condition will vary widely depending on the season, maintenance and usage. Some are well maintained with gravel surfaces, but it’s advisable to travel at reduced speed and carefully avoid any loose rocks on the road surface. Care should also be taken during the Wet when major flooding can occur. There’s no point attempting any journey on outback dirt roads if there has been recent rain.

While you may not necessarily need a 4WD to tackle some of these roads, they may make for a more comfortable ride over the rougher sections and through water crossings. Some of them are definitely not suitable for conventional vehicles or standard caravans. Whatever your choice of wheels, you will need to be prepared for isolation and lack of facilities. Travellers must be well prepared and carry extra water, food and fuel in remote areas.

When choosing a route for a journey to the Top End, be realistic about the allocation of time in your itinerary. The region is a lot bigger than it looks on a map. Think about the

LEFT TO RIGHT: Many unsealed roads are suitable for offroad-capable vans in the dry; The Tablelands Highway is a narrow sealed track across the Barkly region; Always give way to road trains (Credit: Chris Whitelaw)

degree of difficulty and the distances to be covered on a daily basis. If you’re considering a 4WD route, it’s time, not distance, that counts — it can take a lot longer to cover distances on unsealed outback roads than on bitumen highways. Factor in enough time to experience the country rather than trying to cram in too much. Be flexible, you may be so taken by a particular place that you decide to stay on a few extra days. Diesel and unleaded fuels are available at most towns and roadhouses in the Top End. Autogas is also available at Tennant Creek, Katherine, Mount Isa, Cloncurry and Camooweal. Plan fuel stops carefully on outback routes as remote communities that have it can be up to 800km apart. Some may not have unleaded fuel and LP gas is not widely available in the bush. Also, fuel outlets in some remote settlements, particularly Aboriginal communities, are not open every day and then only for limited hours. Check ahead for availability and opening hours or be prepared to cool your heels under a gum tree. Mechanical repairs and some emergency services are available throughout the region — mechanics in many small and remote centres can be amazingly versatile and helpful — but costs for these services may be high. Major vehicle servicing should be arranged at authorised dealers in larger towns, if possible.

To check road conditions and camping area closures inside Kakadu National Park: parksaustralia.gov.au/kakadu/access

For NT national parks: nt.gov.au/parks/regions > check if a park is open

For information about road conditions and closures outside Kakadu National Park (you can also download a dedicated app): roadreport.nt.gov.au/home Ph 1800 246 199

described in detail in Chapter 1 of this Guide.

Kakadu is also an internationally significant cultural landscape. Aboriginal people have lived in the region for about 60,000 years, establishing the oldest continuing culture in the world. It is thought that about 2000 Indigenous people lived there before the arrival of Europeans. Evidence of their occupation exists throughout the Park, in some of the oldest and best-preserved archaeological sites in Australia. Physical artefacts include stone tools, shell middens, earth mounds, scarred trees, grinding grooves, ochre quarries, burial sites and stone and bone arrangements. The sandstone plateau straddling Kakadu and West Arnhem Land contains more than 5000 rock art galleries that record one of the oldest and most spectacular artistic traditions on earth.

There are many sacred sites across the Park, some of which mark the journey or resting place of creation ancestors, while others are ceremonial sites for the performance of rituals, or traditional walking routes. Many of these sites are registered and protected by law.

The Aboriginal people of Kakadu are culturally diverse comprising some 19 clan groups who often speak different languages and, in some cases, practise different traditions. The Indigenous people in the north refer to themselves as ‘Bininj’ (Bin-ning) and in the south as ‘Mungguy’ (Moonggooy), which translate simply as ‘people’. They refer to non-Aboriginal people as ‘Balanda’.

There are several language groups in the Park. Each language is spoken by a number of clans and many Bininj/ Mungguy can speak at least two languages other than English. Gagudju was common until the early 20th century but is no longer widely spoken. The only three spoken on a

Snake Bay

Daly River

Wugularr

Warruwi/Goulburn Island

Australia’s largest parcel of Aboriginal land is largely untouched wilderness.

Covering about 97,000sq km in the northeast corner of the Northern Territory, Arnhem Land is one of Australia’s most remote and largely untouched areas of wilderness.

Its western boundary adjoins Kakadu National Park and runs north along the East Alligator River to the sea at Van Diemen Gulf. Arnhem’s north coast then lies generally along latitude 12 degrees south facing the Arafura Sea, from the Cobourg Peninsula to the Gove Peninsula, embracing many offshore islands. From Gove, the Arnhem coastline runs along the western shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria, including Groote Eylandt, to Port Roper. From here the southern boundary follows the Roper River inland to the Stuart Highway.

The region takes its name from the Arnhem, a vessel of the Dutch East India Company captained by Willem van Colster when he sailed around the Gulf in 1623.

Declared an Aboriginal Reserve in 1931, it remains one of the largest parcels of Aboriginal-owned land in Australia, vested in the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust on behalf of the Traditional Owners. Except for mission stations, white settlement in Arnhem Land was forbidden until the 1970s, and today it cannot be visited without a permit issued by

the Northern Land Council. Some areas of deep cultural significance to Indigenous people are off-limits even to those with permits.

Road access into Arnhem Land is limited to the dry season. In the northwest, the sealed Arnhem Highway enters via Cahills Crossing to become the unsealed Oenpelli Road as it passes through West Arnhem Land to Gunbalanya and beyond. This road can be rough and corrugated but is generally passable by conventional vehicles. In the south, the Central Arnhem Road leaves the Stuart Highway between Katherine and Mataranka and runs almost 700km to Nhulunbuy on the Gove Peninsula. Four-wheel drive vehicles are recommended due to highly variable conditions that include river crossings, washouts, causeways, corrugations, dust and sand. Fuel and supplies are available en route at Mainoru Community Store and Bulman. In southeast Arnhem Land, an unsealed road leaves the Roper Highway near Roper Bar for the remote settlement of Numbulwar on the Carpentaria Gulf. This road is not maintained, and permits are currently not issued for recreational purposes.

Basking in a tropical monsoon climate, Arnhem Land is a

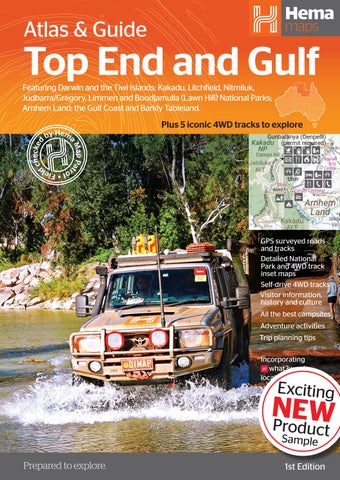

There are plenty of exciting 4WD opportunities in the Top End (Credit: Chris Whitelaw)

The Top End offers exciting four-wheel drive touring in a wide range of landscapes, in conditions that vary greatly with the seasons throughout the year. The 4WD trips presented in this chapter are by no means exhaustive. They represent some of the best offroad experiences to be found in different parts of the region. Some tracks are more challenging than others and they will all be difficult, if not impassable, after heavy rain or in the wet season. When conditions permit, feel free to explore beyond the mainstream tourist routes and discover the wild beauty and natural wonders of this magnificent region.

EASY

All-wheel drive and high range. Novice drivers.

MEDIUM

Mainly high range 4WD but low range required. Some 4WD experience or training required.

DIFFICULT

Significant low range 4WD with standard ground clearance. Should have 4WD driver training.

VERY DIFFICULT

Low range 4WD with high ground clearance. Experienced drivers.

(permit

Island

Island

Estuarine crocodiles

Remember that saltwater crocodiles are not only found in salty water So be careful around any water source including lagoons, swamps creeks and rivers, and always observe warning signs. Some simple precautions should be taken: Do not enter the water Always seek local advice. Never feed, or interfere with, crocodiles. Stay away from the water's edge: watch children and pets closely Clean fish away from the water's edge and remove all waste. If you are going to swim only do so in very shallow rapids Always swim in a group Move well away once you have collected water. When fishing, stand at least four metres from the water's edge and remain alert. Keep arms and legs inside any boat.

Island

Island

Island Grant Island Arnhem Land ALT

permit from the Northern Land Council is required to visit Injuluk Arts in Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) (ph 08 8920 5100, www.nlc.org.au).

(permit required)

(closed

Gunbalanya/Oenpelli (permit required)

(November to

many of the unsealed roads in Australia's northern regions are impassable. Never drive on 'closed' roads Road conditions change rapidly, so visitors should always check with local information centres and shire councils. Many businesses in these areas close in the wet season.

Crocodiles Saltwater (estuarine) crocodiles inhabit