A signi cant part of the Elkhorn Slough Foundation’s work as a land trust involves making connections. By linking conservation lands we create corridors that help native plants thrive and wildlife roam freely.

At another level, ESF builds connections through community outreach, place-based learning, and volunteer programs that inspire conservation.

By bringing local youth and their families to explore the wild places in their own backyards, ESF inspires a sense of connection to the land and links a legacy of land conservation to the future.

People rely on these watershed lands to sustain the sheries, farms, and ranches that support our economy and feed us. We rely on the land to replenish our drinking water, to spark our imaginations, refresh our spirits, and to quench our thirsts for exploration and adventure.

Likewise, the land relies on people — those of us who live and work here, who visit for inspiration and recreation, and who explore and enjoy its diverse habitats and wildlife. Successful conservation starts when we recognize people as a part of the land, not apart from it. Our actions and decisions directly impact the health of these watershed lands, for better or worse.

Your support of the Elkhorn Slough Foundation helps conserve nearly 4,000 acres, spanning from the ridgelines to the tidelines. e following highlights illustrate a 3-mile stretch of ESF-conserved land — part of an area we call the Northern Crescent — wrapping around Elkhorn Slough and its freshwater source, Carneros Creek.

While ESF occasionally acquires properties in pristine condition, most of our lands require considerable restoration and time to heal — and all require thoughtful long-term stewardship to ensure they remain protected now and for future generations.

Located in the northern region of ESF-protected lands, the 330-acre Porter Ranch embodies the history of California and the West. Cattle graze the rolling coastal prairie as they have since the time of Mexican land grants, decades before 1864 when Monterey Customs O cer John T. Porter purchased a substantial part of the Rancho Bolsa de San Cayetano land grant from the family of General Mariano Vallejo.

(continued on page 4)

Slough Foundation

Anne Olsen

President

Robert Hartmann

Vice President

C. Michael Pinto

Treasurer

Bruce Welden

Secretary

Judith Connor

Past President

Gary Bloom

Ed Boutonnet

Terry Eckhardt

Sandy Hale

Kent Marshall

Murry Schekman

Anne Secker

Laura Solorio, MD

Tara Trautsch

Mark Silberstein

Executive Director

e mission of the Elkhorn Slough Foundation is to conserve and restore Elkhorn Slough and its watershed.

We see Elkhorn Slough and its watershed protected forever— a working landscape, where people, farming, industry, and nature thrive together. As one of California’s last great coastal wetlands, Elkhorn Slough will remain a wellspring of life and a source of inspiration for generations to come.

PO Box 267, Moss Landing California 95039

tel: (831) 728-5939

fax: (831) 728-7031

www.elkhornslough.org

“I’m passionate about taking care of Elkhorn Slough: our own special wetland.”

— KERSTIN WASSON, ESNERR RESEARCH COORDINATOR

Scott Nichols, Editor

Elkhorn Slough Foundation

On a warm May evening in Washington, D.C., surrounded by the beauty of the United States Botanic Gardens, the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve’s Dr. Kerstin Wasson stood among seven other conservationists being honored by the Environmental Law Institute. Kerstin received the prestigious National Wetlands Award for Science Research, recognizing her extraordinary commitment to the restoration and conservation of our nation’s wetlands.

For more than 18 years, Kerstin has distinguished herself as a researcher, conservationist, and mentor at the Reserve, and as a leader of projects within and beyond the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) system. She does the amazing job of coordinating the Reserve’s long-term monitoring program, and engages volunteers in every aspect of the work — from collecting water quality data to counting migratory shorebirds to tracking nesting at a heron rookery.

rough her support of citizen science e orts, our volunteers Ron Eby and Robert Scoles began systematically monitoring sea otter ecology and behavior. Kerstin’s guidance and encouragement led these citizen scientists to publish their peer-reviewed study in an esteemed scienti c journal.

“A lot of the joy in my work comes from being part of a collaborative network of folks who are passionate about their special wetlands,” states Kerstin who, with her counterpart from Narragansett Bay NERR in Rhode Island, led the synthesis of data from 16 coastal marsh sites to evaluate their ability to survive sea level rise.

Kerstin’s personal research focuses on restoration of native oysters in California bays and estuaries. On many days you can nd her wearing waders at a research site, placing settling structures made of clamshells in the slough to recruit oyster growth.

“Restoration is certainly an art but it can simultaneously be a science,” said Kerstin as she accepted the National Wetlands Award. “By setting up restoration projects experimentally, we can most powerfully learn from them, to inform our own future work and that of others in similar wetlands.”

When she’s not studying oysters or guiding citizen scientists, Kerstin can be found waist deep in the mud working with graduate students, monitoring Blue Carbon (see Tidal Exchange, Summer 2015), or conducting experiments at the Hester Marsh Restoration project (see Tidal Exchange, Spring 2018).

We join the Environmental Law Institute in celebrating Kerstin’s commitment to excellence in wetland conservation. Above all, we are deeply grateful she does her extraordinary work here at the Elkhorn Slough. ■

Invasive blue gum eucalyptus are thirsty trees, depleting groundwater needed by native plants and amphibians. In the past year, Elkhorn Slough Reserve’s oak restoration project cleared 13 acres of non-native eucalyptus, opening habitat for the recovery of coast live oak woodlands. Where eucalyptus provide important habitat for nesting birds, the groves were left intact and protected.

ough less than 1/3 of the Reserve’s eucalyptus groves were removed, land stewards knew disposing of the felled trees would require signi cant planning and e ort. Reserve stewards considered their options — they could leave the wood to decompose, chip and compost it, or burn it to ash — yet each of these methods would release a signi cant amount of the carbon into the atmosphere.

While pondering the challenge, stewardship specialists had a spark of inspiration. What if, instead of burning the wood to smoke and ash, they could convert it to something useful — biochar.

“Biochar is basically charred organic matter, in this case eucalyptus, burned in a way that reduces greenhouse gas emissions and creates a natural soil amendment,” says Stewardship Specialist Bree Candiloro. “ e process captures up to 50% of the carbon that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere and locks it up for centuries.”

To create biochar, the Reserve splits and cuts the wood into standard rewood lengths, then dries it to less than 20% moisture content. Reserve stewards, interns, and trained volunteers stack the seasoned wood in earth kilns and open piles — 4’ x 4’ stacks topped with lots of dry kindling — and burn the piles from the top down, a method that reduces the smoke to almost nothing. As the piles burn, the teams stack more wood on top, limiting the oxygen available to the wood below. When the moisture, resins and sugars

in the wood burn o and only carbon remains, Reserve stewards extinguish the re with water. By burning wood with little or no oxygen, a process called pyrolysis, they create biochar — a highly stable form of carbon.

ough itself nutrient poor, biochar has a highly porous structure that holds water and nutrients, and harbors bene cial microbes that make these nutrients available to plants. “Biochar improves the soil in the way coral reefs enrich the ocean,” says Reserve Stewardship Coordinator Andrea Woolfolk. “It provides structure where bene cial microorganisms can ourish, supporting living soils beneath our feet.”

At least two student researchers are now using biochar in their marsh planting experiments. At the Hester Marsh restoration site, Reserve researchers are studying the e ects of adding layers of soil blended with small quantities of biochar, and of mixing biochar with soil for restoration plantings.

“As a research reserve, we’re in an ideal position to study how converting restoration waste to biochar can reduce carbon emissions while enhancing soil and water quality,” says Andrea. “We look forward to sharing our results with the larger community of scientists and stewards.” ■

(continued from cover)

Ranching was principally an economic enterprise for these early landowners. Today, these are conservation lands as well as working lands — lush with coastal prairie grasslands, wild owers, and endangered species including Yadon’s rein orchid and Santa Cruz tarplant — where managed grazing serves as a holistic land management tool that bene ts both rangelands and ranchers.

Cattle are moved between pastures according to the habitat and the seasons, clearing tall grasses so spring wild owers like California poppies, sky lupine, and owl’s clover can compete for sunshine, water, and nutrients. Properly timed grazing also supports the federally listed Santa Cruz tarplant, in the sun ower family, which blooms in late summer and fall. After the tarplants go to seed, cattle clear the thatch, work the soil, and enhance the germination of a plant found in fewer than a dozen known locations.

When the Porter family donated these lands for conservation, they established a legacy of connecting people with the land.

In coming years, ESF sees the historic Porter Ranch House as a center for community engagement. ese days, the site often serves as a staging ground for wild ower walks and art workshops, volunteer projects, and history talks.

Just across the marsh, another ESF-conserved property tells a story that contrasts with that of Porter Ranch. ough its name evokes romantic images of coastal scrub and chaparral, El Chamisal was riddled with erosion and piled with trash when ESF purchased the land in 2002.

Decades of poor farming practices left behind a degraded landscape — slashed by gullies — measuring up to 20 feet deep, 60 feet wide, and 600 feet long. Sandy soils ran through the gullies and choked Carneros Creek downstream.

From these damaged hillsides, ESF removed more than 180 tons of trash: piles of plastic, farm barrels, abandoned cars — even a school bus. e Elkhorn Slough Foundation healed the scarred slopes and planted thousands of native plants to hold the soil in place.

Today, El Chamisal lives up to its name. Where gullies once slashed the hillsides, coastal scrublands now ourish. Where trash once wrecked the views, grasslands and wild owers greet the eye. Where runo once choked Carneros Creek, water now replenishes the landscape.

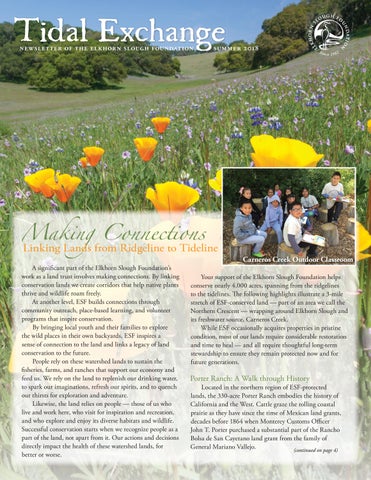

Not far upstream from El Chamisal is the Foundation’s Carneros Creek Outdoor Classroom — a living learning space situated where ESF-conserved properties meet the banks of Carneros Creek.

During the school year, crossing guards from Hall District Elementary guide children safely across the road to hold classes at the Outdoor Classroom. Across the street yet worlds away from their schoolrooms and desks, the students reach their destination — the shade of a majestic oak.

As the students step under its canopy, their talking gives way to a reverent hush. ere is magic in this place, a magic felt by each of the young naturalists sitting in its dappled shade. Volunteer educator Kenton Parker leads the students and teachers on an exploration. e students learn about mountain lions, tiger swallowtail butter ies, and microscopic stream critters called water bears.

Here, the students can study nature in a hands-on fashion: creating “pitfall traps” to discover what types of insects live at the streamside, woodland, and grassland.

Without reluctance or resistance, these young naturalists are applying the scienti c method to study the natural wonders in their own backyard. And they are awed by the magic.

Renteria and Brothers Ranches are among ESF-conserved lands that converge at Carneros Creek near the Outdoor Classroom, then ascend in long valleys to ridges overlooking Elkhorn Slough.

Coastal scrub and oak woodlands dominate the shaded north-facing hillsides, where thickets of maritime chaparral clutch the ridges and adjacent patches of rocky soil. On the south-facing hillsides, well-drained soil and the mild Mediterranean climate provide ideal conditions for row crops, especially strawberries.

Conservancy grant in June 2016. ESF stewards have cleared mountains of farm plastic, planted cover crops and re-contoured the land to reduce erosion on the steep slopes, and have engaged dozens of community volunteers to restore habitat by planting oaks and willows.

Sand Hill Farm is now recharging groundwater and protecting habitat, rather than silting the adjacent wetlands with runo . Yet there is still much work left to be done — large caches of farm plastic to remove, a sustainable organic farm footprint to create, and acres of native habitat to restore. E ective land restoration takes years of time and e ort, and we thank you for supporting ESF’s vision for the future of this key piece of the conservation puzzle.

ese ESF properties honor the farming history of the area and support models for sustainable organic farming. We collaborate with farmers to balance economically viable farming with ecologically healthy lands. Every grower on ESF land uses best practices that conserve natural resources, limit erosion, and protect sensitive habitat. is is a connection that shows the possibilities for farming and conservation to bene t one another.

On the other side of the ridgeline from Renteria and Brothers, the 107-acre Sand Hill Farm links Carneros Creek to the wetlands of the Elkhorn Slough Reserve — protecting the watershed from ridgeline to tideline.

e Foundation has made tremendous progress since purchasing the property with support from a State Coastal

In 2010, a study published by researcher Alison Gee showed improved water quality in the estuary adjacent to ESF-restored lands. e waters and wetlands of the slough depend directly on the health of the surrounding uplands.

ESF’s work is making a di erence — acre by acre — establishing connections, integrating working lands with conservation values, providing corridors for native plants and wildlife, and helping future generations build a relationship with the land.

e Elkhorn Slough Foundation is connected to this land and our community, and our connection to you makes us stronger. ■

is year, the Elkhorn Slough Foundation awarded the James Rote Scholarship for Coastal Science and Policy to graduate student Paulina Salinas-Ruiz who is researching the e ects of climate change on the abundance and distribution of sh and invertebrates along the sea oor of the California coast. Her research builds on studies that suggest warming waters are changing the composition of ocean ecosystems,

causing unprecedented increases in sightings of marine organisms outside their normal ranges.

“Larger predatory sh and bigger schools of sh are staying around later in the year,” observes Salinas-Ruiz. “In some cases, non-native species that have never been documented as far north as California have found their way here, and have the potential to invade and displace native species.”

In her current research, Salinas-Ruiz is crowdsourcing imagery of rare sh and invertebrates taken by recreational and scienti c divers statewide, to be hosted by the California Undersea Imagery Archive at CSU Monterey Bay — along with associated data including species, location, depth, time and date, and attribution. By analyzing this information in context of climate change, she hopes to leverage community science to document ecological changes resulting from warming coastal waters, as well as provide early detection of invasive species and other issues of concern to coastal sheries.

e ESF James Rote Scholarship for Coastal Science and Policy awards $5,000 to graduate coastal research and policy students. e award honors the late educator, scientist, and policy advisor Dr. James Rote — one of the chief architects of the plan to create the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and a founding CSUMB faculty member who wrote extensively about bridging the gap between science and policy.

e Elkhorn Slough Foundation also supports the ESF Conservation Education Scholarships with the Les Strnad Award, established to expand opportunities for local youth to explore the coast and wonders like the Elkhorn Slough.

Former ESF Board member and wetlands advocate Jim van Houten passed away on May 10, 2018. Jim was a former ESF Board member and the lead engineer of the Kirby Park trail. Jim and his wife of 65 years, Ellie, were in the Elkhorn Slough Reserve Docent Class of 1988.

After retiring from a distinguished career in the Navy and as a civil engineer, Jim brought his leadership and professional expertise to conserving the wetlands of the Monterey Bay — from the coastal blu s of La Selva to the freshwater wetlands of Watsonville to the tidal salt marshes of the Elkhorn Slough. Jim was especially proud of his work in the design and construction of the Kirby Park trail and boardwalk — the only wheelchair-accessible trail along the shoreline of the Elkhorn Slough.

“Jim was well loved and respected here in the Cosmic Center of the Universe,” said ESF Executive Director Mark Silberstein. “His work is a lasting legacy for future generations, and he will be deeply missed.” ■

Les Strnad was an early champion of the Reserve and co-founded the local environmental education program Camp SEA Lab. is year, in cooperation with Community Housing Improvement Systems and Planning Association (CHISPA), the Les Strnad Award provided needbased funding for 18 young scientists to explore the wonders of our estuary through Camp SEA Lab’s “Elkhorn Slough & You” summer day camp.

For more information on how you can support ESF’s Conservation Scholarships, please contact our Development team at 831.728.5939.

Dash Dunkell, ESF Stewardship Director

The 2019 Elkhorn Slough Calendar Photo Contest runs through September 7, 2018. Submit your best photos — landscapes, wildlife, plants, or people — taken in Elkhorn Slough watershed within the past two years.

We’ll feature winning images in our full-color wall calendar. All proceeds from the Elkhorn Slough calendar benefit ESF’s work to conserve and restore the Elkhorn Slough and surrounding lands. Visit elkhornslough.org for details — and give us your best shot! ■

e Elkhorn Slough is a very special place to me. At 35 years old, I don’t have many strong memories of what I learned in second grade at Bayview Elementary in Santa Cruz. However, vivid images of a eld trip to the slough have stuck with me throughout my life: pulling up the trawl net to see what we had captured, hiking along the pickleweed, and peeking into the laboratory. Since that time, from my Master’s research in Hawaii to work in Colombia and Chile, my life has revolved around the protection and restoration of sensitive ecosystems. It is a dream come true to be able to return home and help steward the most important conservation properties in the Monterey Bay.

I look forward to guiding and continuing the excellent land stewardship e orts of the Foundation. In my short time, I’ve been impressed with how restoration of degraded former farmlands has returned this amazing place to native habitat while creating opportunities for sustainable organic farms and holistic grazing. I look forward to engaging the community in our work with a variety of volunteer events and opportunities. Most of all, I’m excited to return to my roots to care for these remarkable lands and to protect the health and diversity of our watershed.

See you at the Slough!

Newly hired ESF Stewardship Director Dashiell Dunkell was born and raised in Santa Cruz. He earned his B.S.in Aquatic Biology from UC Santa Barbara, and his M.S. in Natural Resources & Environmental Management from the University of HawaiiManoa. Before coming to ESF, Dash worked as Conservation Director for the Ventura Land Trust.

Join Dash for a sunset stroll on ESF-protected lands on Sunday, September 9 — register today at elkhornslough.org!

P.O. Box 267

The Elkhorn Slough Reserve is open to the public Wednesday through Sunday, 9 am to 5 pm. Visit elkhornslough.org for event details and registration. See you at the Slough!

Every Saturday & Sunday: Reserve Tours

Join knowledgeable docents for tours of the Reserve at 10 am & 1 pm.

First Saturday of every month, 8:30am: “Early Bird” Walks

With local birding expert Rick Fournier. Meet at the Reserve at 8:30 am.

Wednesday-Friday through August 17: Weekday Reserve Tours

Enjoy special weekday tours of the Reserve Wednesday–Friday at 11 am, through August 17.

September 9: ESF Sunset Stroll with Dash

Join new ESF Stewardship Director Dash Dunkell for a sunset walk on ESF-protected lands.

September 22: Elkhorn Slough Reserve Open House

Celebrate National Estuaries Week with walks, talks, and crafts at our annual Open House.

September 28–30: 2018 Monterey Bay Birding Festival

Register for Elkhorn Slough eld trips and lectures with our partners at montereybaybirding.org.

October 6: ESF Fall Kayaking

Enjoy a morning paddle on the estuary with expert guide and citizen scientist Ron Eby.

October 6–7: Arts Habitat Open Studios at ESF’s Porter Ranch

See the work of four local artists, including Elkhorn Slough Artist-in-Residence Denise Davidson.

October 27: Birding the Fall Migration with Rick Fournier

Spot birds of the fall migration on conserved lands with expert local birding guide Rick Fournier.

Moss Landing, CA 95039 Visit ElkhornSlough.org