Tidal Exchange

A vision of regional connectivity for Elkhorn Slough

Taylor Honrath, Deputy Director

Three watersheds converge at the geographic center of Monterey Bay—the Pajaro River to the north, the Salinas River to the south, and Elkhorn Slough perched between. With its headwaters in the upper reaches of Carneros Creek, west of San Juan Bautista, the Elkhorn watershed is a hotbed of biodiversity. In short succession, a tapestry of ecosystems unfolds, from ridgelines of maritime chaparral

Elkhorn Slough Foundation

board of directors

Hon. Susan Matcham

President Tara Trautsch

Vice President

David Warner

Treasurer

Becky Suarez Secretary

Gary Bloom

Judith Connor

Terry Eckhardt

Emmett Linder

Mi Ra Park

Anne Secker

Laura Solorio, MD

Bruce Welden

Mark Silberstein

Executive Director

The mission of the Elkhorn Slough Foundation is to conserve and restore Elkhorn Slough and its watershed.

We see Elkhorn Slough and its watershed protected forever— a working landscape where people, farming, industry, and nature thrive together. As one of California’s last great coastal wetlands, Elkhorn Slough will remain a wellspring of life and a source of inspiration for generations to come.

PO Box 267, Moss Landing California 95039

tel: (831) 728-5939

fax: (831) 728-7031

elkhornslough.org

Tidal Exchange

Ross Robertson, Editor

2025 Elkhorn Slough Foundation

John Battistoni, Elkhorn Slough Reserve Manager

After nine months as Acting Reserve Manager, John Battistoni became Manager of the Elkhorn Slough Reserve on July 1, 2025.

I’ve always had a special place in my heart for Elkhorn Slough. I grew up in Fresno, and my family vacationed out here a lot when I was a kid. My wife and I both love the ocean; we kayaked Elkhorn Slough on our honeymoon.

So when Dave Feliz started talking about retirement, I was immediately interested in learning more. The more I got to know this place over the last nine months, the more incredible it became. People here are dedicated. Seeing how much Elkhorn Slough means to this community really made me want to invest more of my time here.

I’ve always been drawn to land stewardship. For the last nine years, I supervised the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s San Joaquin Valley–Mojave Desert Ecological Reserve Unit. I was a Field Biologist with the same unit for eight years before that. As unit supervisor, I was working at the 10,000 foot level, managing a bit under 55,000 acres at 21 properties across five counties. Now, I’m looking forward to focusing on just one property and one suite of species.

I love wetlands and wetland species—one of my first projects as a CDFW Field Biologist was conducting an inventory of vernal pools, which are the Central Valley’s version of the seasonal wetlands we have out here. And I’m excited to learn more about the marine species and habitats at Elkhorn Slough.

More than anything else, I want to make sure we keep conserving everything that makes Elkhorn Slough unique. Through CDFW’s longstanding partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Elkhorn Slough Foundation, I know we’ll continue to do great things. n

PARTNERS

continued from cover

to native oak woodlands, grasslands, tidal salt marshes, mudflats, and all the way down to the depths of the Monterey Canyon.

Drop a pin at the Moss Landing Harbor mouth and draw a ten-mile radius around it, and you’ll encircle an area that supports thousands of species. For more than 300 species of birds, this is a critical stopover on the Pacific Flyway that spans the length of North and South America, from Alaska to Patagonia. Sharks, seals, and sea otters ply the channels of the slough. Endangered amphibians gather to reproduce in seasonal freshwater ponds. Rare endemic plants with names like Santa Cruz tarplant and Yadon’s rein orchid pepper its valleys and hills.

But the spiderweb of roads, farms, ranches, and residential communities that surround Elkhorn Slough also fragments the landscape, making wildlife movement more hazardous. UC Davis reports that every year in California, collisions with cars kill roughly 100

mountain lions and 48,000 deer; 5,000 Pacific newts die annually on a single road near Los Gatos.

One of the keys to ecological health is landscape connectivity—the ease or difficulty of movement between resources and habitats. Movement is essential to life. From one of California’s last remaining large carnivores, the mountain lion, to the tiny Santa Cruz long-toed salamander, wildlife migration, foraging, breeding dispersal, and gene flow can all be impeded by habitat fragmentation. As climate change accelerates, these problems compound, because climate adaptation requires movement, too. That’s why Elkhorn Slough Foundation (ESF) is embracing the challenge of regional connectivity.

Over the last 43 years, our vision for Elkhorn Slough conservation has expanded with our successes. Building (continued on page 5)

continued from page 3

on work by The Nature Conservancy and others in the 1970s, ESF’s efforts in the 80s and 90s were focused on protecting wetlands in the core areas of the Elkhorn Slough Reserve. Then in 1997, we became a land trust to begin conserving and restoring critical lands outside the Reserve where excessive erosion, groundwater overdraft, and polluted runoff were having outsized impacts on the health of the estuary.

Sand Hill Farm is a good example of this. Thanks to restoration work supported by ESF donors and volunteers, the property went from shedding ~11,000 cubic yards of sediment into Elkhorn Slough during the El Niño rains of 1997–98 to no erosion whatsoever during the comparably heavy atmospheric rivers of 2022 and 2023.

Now at the halfway mark of the 30x30 initiative in California—a statewide commitment to protect 30% of our lands and coastal waters by 2030—ESF is expanding its horizons once again. The logic is clear: The more we knit our network of conservation lands into the fabric of protected ecosystems beyond our watershed, the more the watershed itself can adapt and thrive in the face of a changing climate.

As my colleague Kevin Contreras likes to say, ESF’s land acquisition strategy has always been to create “a network, not a patchwork” of conservation properties. In zip codes under this much development pressure, with land this expensive, conservation is always a balancing act. It’s not often possible to set aside contiguous linear corridors for wildlife to move through, but building pathways of “stepping stone” habitats that link larger core areas is often effective.

The more we knit our network of conservation lands into the fabric of protected ecosystems beyond our watershed, the more the watershed itself can adapt and thrive in the face of a changing climate.

We’ve set our sights on crucial native habitats in need of protection, like the freshwater wetlands of Elkhorn Highlands Reserve and the rich coastal prairies of Porter Ranch. We’ve moved further and further up Carneros Creek toward the headwaters of Elkhorn Slough, restoring riparian corridors and ephemeral ponds while also preserving sustainable organic farms like Triple M Ranch. We’ve deepened our ties in neighboring communities like Las Lomas, where we nurture students, families, and nature alike at the Carneros Creek Outdoor Classroom.

The two biggest core habitat areas in the region are the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Gabilan Range. Elkhorn Slough is located right along the western edge of the more developed area between the two. That makes our portion of northern Monterey County, with its relative scarcity of parks and open space, something of a bottleneck for wildlife—and lends the protected areas of the Elkhorn watershed added significance.

While landscape connectivity is not a new concept, it remains an underused tool in conservation planning. This needs to change. Alongside the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County and many others, we’re part of the working group for the “Santa Cruz Mountains to Gabilan Range Linkage” project, which seeks to maintain biodiversity and improve habitat quality for wildlife by promoting regional connectivity.

Highways are the biggest barriers to movement

(continued on page 8)

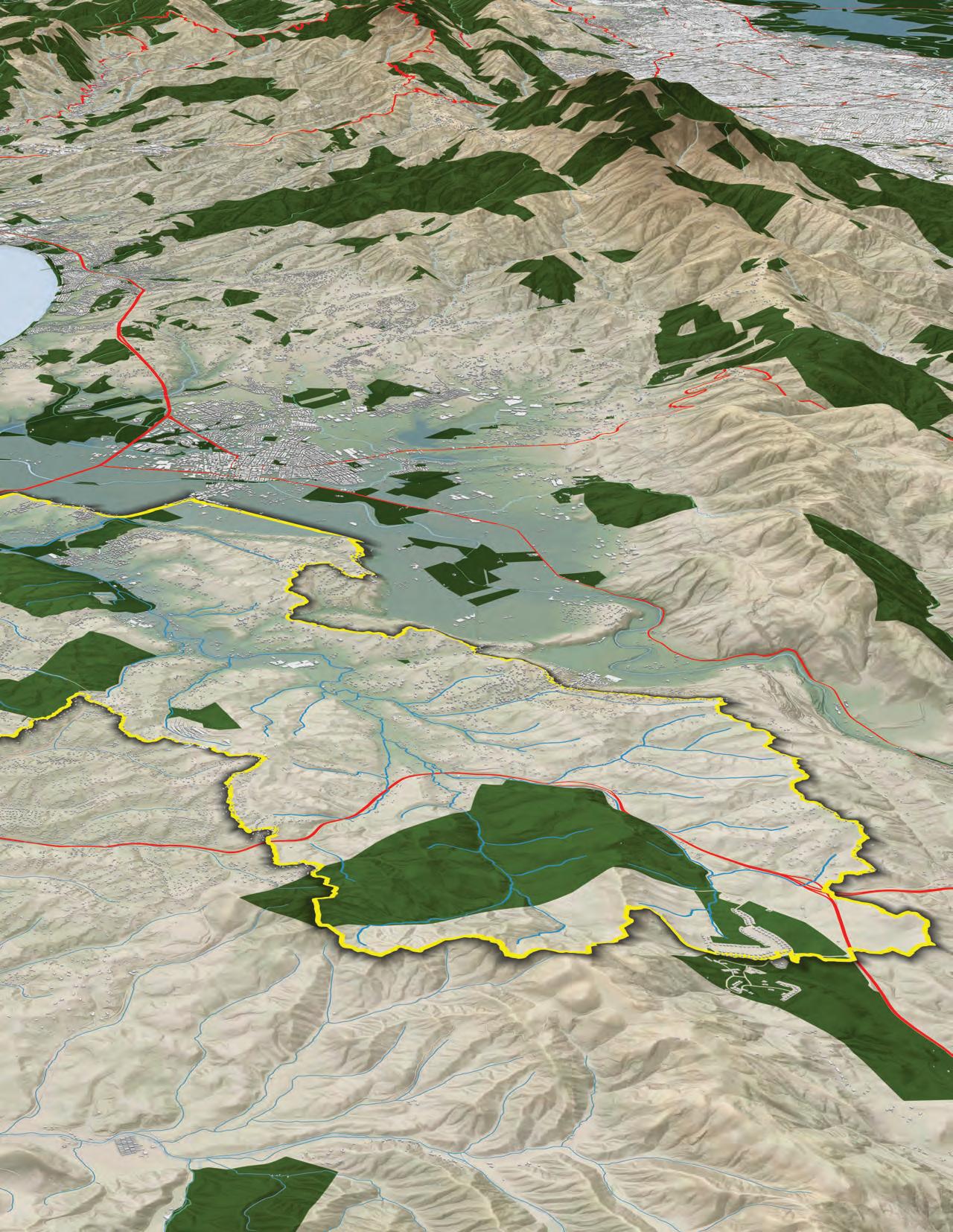

EXPANDING

Protected Lands

Elkhorn Watershed Boundary

East-West Wildlife Corridor

North-South Wildlife Corridor

Map by Charlie Endris. Basemaps: ESRI, USGS, NASA.

continued from page 5

between these mountain ranges. Similar to the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing currently under construction in the Santa Monica Mountains northwest of Los Angeles, we’re participating in collaborative efforts here to lay the groundwork for wildlife crossings of Highway 101 in the upper Elkhorn watershed.

In recent years, we know of at least three mountain lions killed by vehicle collisions along Highway 101 in the Aromas Hills—and many more deer, badger, bobcat, and coyote. All of these mammals are considered keystone species because their presence safeguards the surrounding ecological community.

Protecting keystone species protects whole ecosystems. When a famous marine keystone species, the southern sea otter, returned to Elkhorn Slough in the 1980s, it triggered a “trophic cascade” of positive impacts, including the dramatic recovery of declining eelgrass beds and the stabilization of eroding marsh banks. The same may be true, but in reverse, if terrestrial keystone species disappear due to habitat fragmentation.

“Mountain lions exert such a substantial impact on

In his quest to track mountain lion movements and design optimal corridors for connectivity, CDFW’s Zach Mills has a simple request: “Let us know if you see lions.”

Speed is usually the difference between a lion being collared or being long gone. So if you encounter a lion or see one on a porch camera, please fill out an incident report right away— within hours if possible:

the environment,” the Cougar Conservancy writes, “that the number of songbirds, fish, amphibians, reptiles, rare native plants, and butterflies would potentially diminish if this apex predator were lost. When we protect mountain lions, we protect other animals too.”

Requiring up to 100 square miles of home range per adult, mountain lions are currently a candidate for listing under the California Endangered Species Act. Physical signs of inbreeding depression have already been documented in Santa Cruz Mountains populations, early indicators of a developing extinction vortex.

To improve gene flow between the Gabilan Range and the Santa Cruz Mountains, our partners at California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) have deployed camera traps on ESF properties to identify mountain lion movement patterns and inform the placement of Highway 101 wildlife crossings. When they detect lions, they attempt to bait, trap, and fit them with radio collars.

Ultimately, improving landscape connectivity for mountain lions has benefits beyond conservation.

“There is substantial evidence that more space for large carnivores reduces the occurrence of human-wildlife

(continued on page 10)

native ecosystems

Facing page: CDFW sets up camera traps on ESF-protected lands.

continued from page 8

conflict,” says CDFW wildlife biologist Zach Mills. “And Elkhorn Slough Foundation’s protected lands are the most intact and appropriate habitats for lions west of Highway 101.”

As we grow the organization to encompass regional conservation priorities, ESF’s longtime focus on native species and habitats remains steadfast. We’re now in the process of removing 80 acres of invasive eucalyptus from the hills surrounding Elkhorn Slough, making way for the large-scale restoration of functional native ecosystems across the watershed— from historical oak woodlands to endangered coastal prairies.

We also remain focused on water itself. We’re restoring the network of freshwater wetlands that enables isolated amphibian populations to freely move and interbreed. We’re building new groundwater recharge basins at properties like Brothers Ranch to shore up our aquifers and prevent saltwater intrusion. And thanks to generous ongoing support from an anonymous family foundation, we’ve identified areas where year-round water sources can be developed on ESF properties, to

provide wildlife with freshwater and prevent species from leaving our protected lands to seek water on neighboring farms or residential areas.

Having recently completed a successful multimillion-dollar conservation campaign, Elkhorn Forever, we now have more than just a vision for regional connectivity—we have the resources to make it a reality. We’re already having conversations with multiple landowners in the upper Elkhorn watershed to add more

“Elkhorn Slough Foundation’s protected lands are the most intact and appropriate habitats for lions west of Highway 101.”

stepping stones to a new conservation corridor extending up Carneros Creek, across Highway 101, and into the Gabilan Range. With a little luck, a lot of elbow grease, and the incredible philanthropy of our community, the Elkhorn watershed will be a regional nexus for wildlife for generations to come. n

Thanks to the generosity of our community, the Elkhorn Forever campaign has been a resounding success. Campaign funds are already being put to work, from powering large-scale habitat restoration to acquiring high-conservation-value properties. Though Elkhorn Forever has ended, this is truly just the beginning.

We would like to thank all of our supporters for helping us with this transformative leap forward. From people who attended campaign events and helped spread the word to those who gave gifts of $5 or more, this achievement—and the conservation success stories that will surely follow—belongs to all of you.

We also thank our fellow members and honorary members of the campaign committee for dedicating their time, talents, and resources to propel this campaign to a successful conclusion. Similarly, this would not have been possible without ESF’s forward-thinking Board of Directors, the enthusiastic efforts of the staff, and the guidance of our consultants.

We’re proud of what our community has accomplished. The staff looks forward to sharing future progress made possible by this campaign. Thank you for sharing the vision of protecting Elkhorn Slough forever, and for making that vision a reality. n

Thanks to you, we successfully completed Elkhorn Forever, our campaign to conserve more land and restore critical habitat around Elkhorn Slough.