The

Additional

The PePPer Family FoundaTion

MARCH 14-17 2023

ESO’s annual Ainsworth Concerts for Youth are made possible with support from the S.E. (Stu) Ainsworth Family.

This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

support for this project is provided by ComEd, an Exelon Company, and a Fall 2022 Farny R. Wurlitzer Foundation Fund Grant found at DeKalbcf.org.

TEACHER GUIDE

Welcome back to the Hemmens Cultural Center!

Thank you for sharing incredible music with your students, our community, and your Elgin Symphony Orchestra at the Ainsworth Concerts for Youth. This Teacher Guide is intended to help you prepare your students for the concert, and to help maximize their understanding, excitement, and curiosity.

Symphonic Storytelling

What do you think of when you imagine great storytelling?

The art of storytelling goes far beyond the words, the plot summary, or the narrative twists and turns though these elements are important, too. Great storytelling both paints a clear picture and allows for individual interpretation; it hits the sweet spot between being painfully literal and confusingly vague. A great story puts you, the audience, in the world of the story with vibrancy and detail in color, sound, feel, even smell and taste.

Just as storytellers evoke this suite of images and episodes through words, composers do through sound. (And both use well-placed silences, too!) Each choice of pitch, rhythm, timbre, and dynamic makes a difference as these elements come together to tell a story through music. What if Prokofiev had used the saxophone instead of the bassoon how might that have changed our impression of Grandfather? Or, if Respighi had utilized a fuller orchestration with trombones and tuba, might the brilliance of springtime been lost?

In exploring these two magnificent pieces, I hope your students will start to see the possibilities not only of composing, or of storytelling, but of cultivating their sense of curiosity and wonder while interacting with music, art, and the world around them. Utilizing metaphors of storytelling and visual art, we aim to give young musicians the tools to start uncovering more details and insights into the music they hear both at these concerts and every day.

As always, the objective isn’t for them to get it right away; it’s to spark inquisitiveness, give students the tools to engage with art, and to experience a spirit of expert noticing of the world around them. No matter where they are in their musical lives (or where they go next), this will help them create meaning from the world around them. And if they ascribe different meaning to art than you or I do? Great! We’ll embrace that ambiguity and messiness, knowing that it’s in exploring and grappling with meaning that we can grow and learn the most.

Thank you for partnering with your Elgin Symphony Orchestra as we explore Symphonic Storytelling.

See you in March!

Matthew Sheppard Education Conductor, ESO msheppard@eyso.org

Dear

January 2023

teachers,

TEACHER GUIDE: A User’s Manual

1. Get to know the music. Before diving in with specific strategies and concepts, take some time familiarizing yourself with repertoire that’s new to you. Just as you would with any other piece that you’re teaching, listen a few times and develop your own relationship with the music before introducing it to your students. When you’re passionate about it, they’ll know.

Look for the links, or find your own on Spotify and YouTube

2. Choose (and use) what works for you. You know your students best! Think of this guide as a way to jump-start your creativity and imagination, rather than a one-stop-strategies-shop. Try to view it as an open-ended set of possibilities, rather than a prescribed curriculum and lesson plan from start to finish.

3. Make it your own. Do you see connections to repertoire and concept you’re studying? Great run with it! Teaching this music works best when it’s integrated with your classroom work, rather than as a separate break out. If you find yourself saying “OK, now it’s time to put our music away and prepare for the ESO concerts,” there may be more opportunities to make connections with your music.

4. Listen in class. Students aren’t rehearsing this music in class every day they won’t just “get to know it” organically without intentional listening during class. Choose a few targeted moments of Trittico botticelliano each day to listen to and unpack, or learn a new theme from Peter and the Wolf every day for a week. A longterm, multi-week exploration will go a long way.

5. Don’t feel the need to do it all. Be targeted in your approach: go deeper with one piece or concept, rather than feeling the need to get to everything. The objective of this guide is to maximize the student experience, but that might mean different things for your students. Can you take the concepts of timbre and apply them to a piece you’re singing/playing right now? Do it, and leave one of the other concepts for the concert in March.

Concepts

Look for this box with the 30,000 foot overview for each piece

6.Remember: there’s no expiration date. This Teacher Guide doesn’t go bad at the end of March keep using it if it works for you. It can be especially meaningful to return to these concepts after your students have heard the entire piece live.

7. Talk to other teachers. There are a few targeted “cross-curricular hints” in this guide; you’ll certainly uncover more possibilities. Find a cross-curricular connection that works for you? Let me know, and we’ll spread the word Building with and on the work of our colleagues benefits our students.

8. Trust the music. This music is compelling, exciting, and captivating. The Teacher Guide includes a few introductory strategies to alleviate possible friction points, but ultimately, the best ambassador for the music is…well, the music. If you find yourself spending more time listening and unable to cover all the strategies and concepts, that’s a win. Remember, we’ll explore this together in March, too.

And as always, stay in touch.

Did you discover something new that really worked for your students? Want to get clarity on a concept or go deeper on a piece of music? Looking to talk shop about music and education? Let me know; I’d love to hear from you.

Ottorino Respighi

July 9, 1879 (Bologna, Italy) – April 18, 1936 (Rome, Italy)

Trittico botticelliano (Botticelli Triptych) I. La Primavera (Spring)

A MUSICAL PAINTING

For centuries, music and visual art have had a powerful symbiotic partnership. Drawing their inspiration from the colors, stories, and characters that artists depict, composers paint with a sonic brush, bringing a new dimension to paintings, drawings, sculptures, and ideas. These new aural masterpieces take on their own unique flavors and colors through sound.

One of the most colorful, vibrant, and glorious examples of the synthesis of visual and sonic art comes from Italian composer Ottorino Respighi. His Trittico botticelliano (Botticelli Triptych) was inspired by three paintings by Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510). Each movement takes its title from a specific painting by Botticelli. At our concert, we’ll explore the first movement: La Primavera, or Spring. (The second and third movements The Adoration of the Magi and The Birth of Venus would be great to explore in your classrooms, too!)

Asking big questions…

1) How can something we see relate to something we hear? How can a painting inspire a sound?

2) Does it work in the opposite direction: can something we hear inspire a visual image, even in our imagination? When you close your eyes and listen to music, do you “see” something? What about the sounds inspire that image?

NEW POSSIBILITIES

In the early 20th century, composers across the world were exploring with the new possibilities unleashed by a torrent of innovation in both composition and technology. New modes of travel created opportunities for travel and cultural exchange as never before, and the increasing reliability of both visual and audio recording devices allowed for more authentic reproductions in both mediums. Burgeoning fields of archeology and new methods of excavation and preservation were leading to tremendous discoveries particularly in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East that helped paint a picture of life before the present: a picture more vivid and vibrant than ever before. And, in the musical world, advances in instrument technology coupled with adventurous new compositional techniques to offer the most varied palette imaginable for composers such as Ravel, Debussy, Rimsky-Korsakov, Stravinsky, and of course, Ottorino Respighi.

Hint: this is a great opportunity to make cross-curricular connections. Check in with the classroom teacher: are they exploring different cultures through geography or history? Ask how today’s technologies allow us to experience worlds beyond the one we can physically touch.

Ottorino Respighi

LOOKING

Introducing the painting

This painting is filled with color, movement, texture, and hints of storytelling: it’s captivating to look at and uncover new details and intricacies.

There are so many ways to use it as you explore Respighi’s sonic canvas:

1) Show the painting to your students before you listen to La Primavera. Have them speculate: what kinds of sounds might be present at this scene? Focus on the affect and feeling of the scene, rather than Respighi’s specific musical depiction, and don’t worry about limiting it to music yet. Is it…

a. Loud or soft?

b. New or old?

c. Bright or dark?

d. Simple or busy?

e. Moving or still?

f. Monotone or colorful?

g. Slow or fast?

h. And add your own!

2) Examine the elements of motion, form, and color within the painting:

a. How does Botticelli create a sense of motion within a still painting?

b. How are ideas and images grouped together within the bigger picture. With so many ideas in one painting, how does Botticelli keep it from being a jumbled mess?

c. Are certain colors more prominent than others? How do they work together in foreground and background within the painting?

Primavera, Sandro Botticelli (late 1470s or early 1480s)

Primavera, Sandro Botticelli (late 1470s or early 1480s)

3) Zoom in on one particular part of the painting. While we see it mostly in small scale, it’s actually huge in real life: over 10 feet wide and 8 feet tall! What details are revealed with a closer look? Try using some of the images and insights from this website to take a closer look here’s one to get started:

4) Have a creative crew this year? Ask them to create their own soundtrack to this painting Give them some tools and a time limit, and see what they come up with. Make sure to ask them how their soundtrack relates to the painting does a sound reference a specific image/idea, or is it a general feeling/mood?

The Adoration of the Magi, Sandro Botticelli (1475-76)

Since he lived in the 15th century, Botticelli didn’t leave us with any selfies…but we still have an idea of what he looked like. In his painting The Adoration of the Magi, Botticelli inserted many different characters into the stable scene: members of the wealthy Medici family who sponsored the painting, as well as himself Hint: invite a local artist or your school’s visual art teacher to present with you!

Close-up, presumed to be Botticelli himself

LISTENING

Introducing the piece

This movement is positively bustling with energy, activity, and color it’s a joyful and fun listen for kids. Many of the strategies you employed in looking at the painting can be similarly used in listening:

1) Have your students close their eyes and listen to the opening 30 seconds of La Primavera. What words, ideas, and emotions came to mind as they listened? Is it…

a. Loud or soft?

b. New or old?

c. Bright or dark?

d. Simple or busy?

e. Moving or still?

f. Monotone or colorful?

g. Slow or fast?

h. And add your own!

2) Take it to the next level by asking students to back up their answers with evidence from the music. Ask them to describe what makes it bright and moving rather than dark and still.

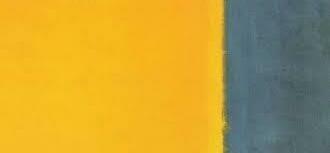

3) Begin to make connections between sound and image: have students choose one color from a color wheel or set of crayons and draw what they hear. It doesn’t need to be an elaborate scene focus on the color and the texture. Did anyone choose brown, or dark blue? What about yellow, red, orange, and pink? Why and why not?

Which comes first, the music or the painting?

Do you start by introducing your students to the music or to the painting? Just like with the chicken and the egg, there’s no right answer. (OK, maybe ask your science teachers about that one.) Ultimately, it comes down to what you want your students to learn, and which order and strategies will best help you reach your outcomes.

If you already do a lot of listening with your students, they may already be primed to listen to La Primavera and conjure up images. Then, you can compare their images with those of Botticelli: what themes (motion, color, etc.) hold true to both? If listening to and describing music is a newer skill for your students, you can help prime them for this by looking at the painting first it can be a little easier to imagine in that direction.

OK…but do I even need to show the painting?

One of the joys of art is that it continually refreshes both us and itself by revealing new layers of meaning. Does Respighi’s music stand on its own without the painting? Absolutely! Is Botticelli’s painting worth looking at without Respighi’s soundtrack? Of course! But multi-layered, richly crafted art offers new meaning, insight, and discovery with every visit. That’s what keeps us coming back: the opportunity to widen our world of possibilities not just to “get it” and move on.

By exploring how the two relate to each other, we celebrate the capacity of learning, creativity, and wonder within each one of us. In 10 Lessons the Arts Teach, Elliot Eisner reminds us that “The arts make vivid the fact that neither words in their literal form nor numbers exhaust what we can know. The limits of our language do not define the limits of our cognition.” In exploring these multiple perspectives, we celebrate the possibilities of learning and art within multiple domains, and we allow our students to see themselves within it.

INSTRUMENTS FAMILIES AND COLORS

Respighi’s use of timbre and instrumental color in La Primavera is absolutely fabulous. (That’s true in much of his music, in fact.) We can use his colorful choices to draw connections between sound and story, as we explore the affect of these specific compositional choices.

THE STRINGS

From the very first notes, Respighi uses the strings as the framework for the story within the painting. They’re rarely the main characters…but without their supporting hustle and bustle, the music lacks energy and motion.

Trills and bird calls

To frame the fantastic celebration of spring that is La Primavera, Respighi uses the strings to depict the ultimate expression of the springtime: birdsong! Do a quick compare and contrast of these two videos:

• the opening 30 seconds of La Primavera

• this video of a chipping sparrow chirping Respighi nailed it. Use this close-up trill video to show how string players actually do this, and then have your students try it, sans instruments.

1) Hold both hands up, palms facing outward

2) Wiggle your fingers as fast as possible, bending at the knuckle but not moving your wrist

3) Make a “C” with your left thumb and index finger, and clamp it around your right wrist

4) Rapidly lift and place your fingers just like in the video

How would YOU have done it?

What other ways can you think of to imitate the quick-paced trilling of birds? Have students experiment with different possibilities:

• Rolling their Rs

• Whistling

• Quickly tapping on their desks with pencils/pens/triangle beaters

• Whatever else they come up with!

What worked best…and what didn’t work so well? Why or why not? What are the characteristics of a sound that make it seem like bird call? (Rapid fluttering, high pitch, non-perfect symmetry/evenness, _____)

THE BRASS

The French horn and trumpet play prominent roles in the opening as the “callers.” These fanfare instruments gather everyone together, letting us know that the festivities are about to start!

Here’s a great video demonstration of the French horn to help students see and hear the sound. Compare that with this video of a traditional hunting horn. What images and ideas come to mind when you hear these sounds. How does that align with our story for Respighi’s La Primavera?

A chipping sparrow

A chipping sparrow

The TA-DA effect

Have students demonstrate the increasing intensity of the hunting call that Respighi imitates:

• Divide the class into groups, and have each group stand in a different part of the room

• Teach the whole class to sing “Ta-Da!” Aim for a perfect fifth, with great energy and articulation!

• Have each group sing “Ta-Da!” three times, then pass to the next group. The next group has to try and out-do them in intensity. Make sure the first group doesn’t start too loud, and encourage them to use more than just dynamics! Try pitch (higher = more intense), articulation, and increasing the length of the “Da”, just like Respighi

THE WOODWINDS

Respighi’s use of the woodwinds evokes ancient times: his “antique” music starting here is a great example of how he does this. Using the trio of oboe, clarinet, and bassoon, he begins a new idea: a gentler, softer, more delicate dance than the tumultuous festival that began the piece.

MUSICAL MAPS

What about the woodwinds?!

We spent less time focused on the woodwinds in the Respighi, but don’t worry Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf will give you and your students ample opportunities to explore them, too!

While it is programmatic, Respighi’s La Primavera is quite different from Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. The inspiration for Prokofiev’s masterpiece is a specific story: a musical depiction of specific events, at specific times, and in a specific order that must be followed for the story to make any sense.

La Primavera is inspired by visual art, which leaves and leads to all sorts of different possibilities. Have your students think back to the painting: were they able to detect color, form, and motion in it, with your help? These are all inherent to the painting and the music…but there isn’t a specific story or narrative that must be followed. This means that our musical imaginations are totally freed, and we have the space for our imaginations to take flight!

1) Have students create a color map of the piece. Give each student a piece of paper and a set of crayons/colored pencils. Have them divide the paper into 4 main sections, which reflect the following moments in the Philharmonia Orchestra of London’s YouTube recording:

a. Call to Dance (to 1:40)

b. Ancient Music (1:41-2:54)

c. Layering/Building Music (2:55-4:58)

d. Bird Calls (4:59-end)

Encourage students to choose colors, making choices both left to right and vertically (just like you would read a score) that reflect what they hear.

2) Create your own story. Though Botticelli and Respighi didn’t have a specific story in mind, that doesn’t mean your students can’t. Using what they’ve uncovered about instrumental timbres and colors, what images and stories appear in their imagination?

3) Your very own soundtrack. Try two different techniques to encourage composer creativity in your students:

a. Using Botticelli’s painting, encourage students to craft their own sonic depiction of this painting. Encourage them to be creative with the tools they have at hand: their bodies, musical instruments, and even items in the room.

b. Ask students to use images you provide and create their soundtrack to these. This is a little harder: they have to make connections and transfer the ideas about timbre and color from La Primavera into something new.

c. Have students find their own image and either 1) create a soundtrack or 2) describe using musical language how their soundtrack would sound. (e.g. “Starts loud, high, and loud with the violins and flutes, then drops low, slow, and soft to the brass”)

Tip: give them a timeline for their soundtrack to make it more manageable!

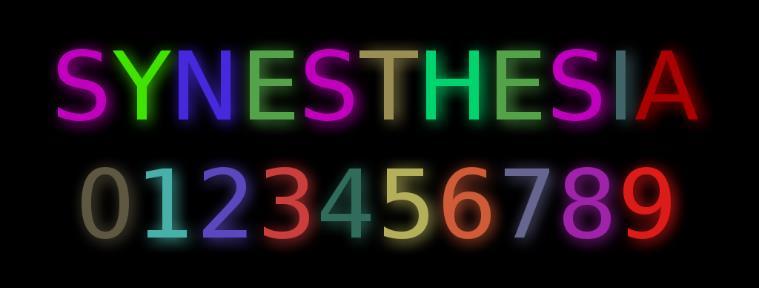

WORD OF THE DAY

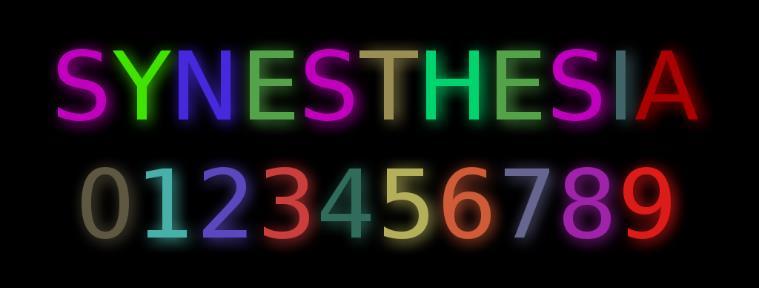

Synesthesia (n): a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory of cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory of cognitive pathway. Examples include association of:

• Numbers and colors

• Colors and sounds

• Tastes and colors

• Sounds and numbers

• Locations and time (1980 is further away than 2000)

Chromesthesia (n): a type of synesthesia that specifically connects sensation of sound to that of color.

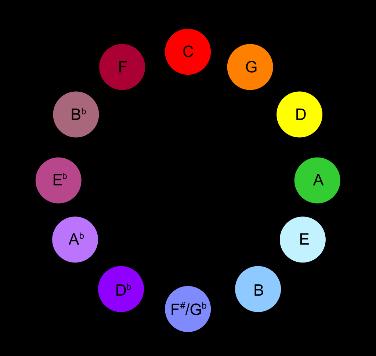

Famous composers reporting synesthesia include:

• Aleksander Scriabin

• Olivier Messiaen

• Franz Liszt

• Amy Beach

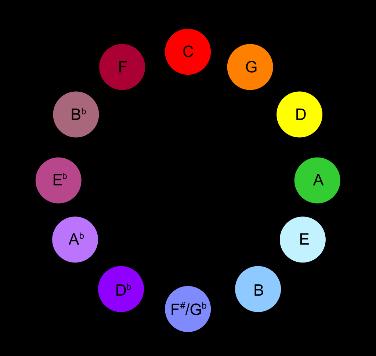

Scriabin’s sound/color associations

FURTHER STRATEGIES AND ACTIVITIES

Sounds and colors

• Draw associations between specific sounds and colors. Start with instrument timbres and harmonies, and have the class debate. Why does the piccolo sound bright yellow and the tuba sound dark blue? Mythological associations

• Botticelli’s painting is chock-full of mythological characters: Cupid, Zephyrus, Cloris, Mercury, Venus, the Three Graces, and more. Examine their mythological associations can you hear them written into Respighi’s music? Neo-whaticism?

• Much of Respighi’s music is influenced by the past: Botticelli’s paintings from 500 years before his time, the three suites of Ancient Airs and Dances, and his Roman Trilogy. This trend of incorporating the past into your present art continues to this day. Can you find examples in contemporary music/art of an artist referencing the past?

OTTORINO RESPIGHI

Primarily known for his spectacular use of orchestral timbres and colors in both the large scale (Pines of Rome) and in smaller chamber-sized works (Trittico botticelliano), Ottorino Respighi was a leading composer and musicologist in early 20th-century Italy. Having studied with master orchestrator Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov in his twenties, Respighi returned to Rome where he began a series of transcriptions of works from the 17th and 18th centuries. His twin passions of composition and musicology fed on each other, and much of his oeuvre reflects the synergy of the two.

Respighi was an international presence in his lifetime, having toured both South America and the United States, along with much of Europe and near Asia. Trittico botticelliano was premiered in 1927 while Respighi was concertizing and teaching in Brazil, and it bears a dedication to his American patron and sponsor, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge.

Concepts Instruments Storytelling

Empathizing across time and space

STORIES AND STORYTELLERS

Sergei Prokofiev

April 27, 1891 (Donetsk region) – March 5, 1953 (Moscow, Russia)

Peter and the Wolf A Symphonic Fairy Tale for Children

As perhaps the single best-known piece of classical music written for children, Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf has captured the hearts and imaginations of children for nearly a century. Written in 1936, the piece was specifically tailored to this setting: a children’s concert at the Central Children’s Theatre in Moscow, where Prokofiev’s music would help introduce young Russian children to the instruments of the orchestra. Written entirely by Prokofiev music and text in just over three weeks, the simple tale feels timeless, with music perfectly paired to the text, mood, and narrative.

And, note for note and word for word, this symphonic fairy tale has continued to enamor audiences across the globe since its premiere. It has been translated into over a dozen languages, been recorded more than 400 times, spawned dozens of productions (movies, live-action, puppets you name it!), and had such notable and varied narrators as David Attenborough, Mikhail Gorbachev, Bill Clinton, Eleanor Roosevelt, Sean Connery, Patrick Stewart, Alice Cooper, and Sting. This story has some serious staying power

It’s a pretty simple story, on the face of it: “Boy captures wolf with aid of animal friends, despite his grandfather’s strict prohibitions,” reads the description in Daniels’ Orchestral Music Handbook. But, just as in any great story, painting, or composition, it’s the details and colors that make it such a timeless masterpiece.

Asking big questions…

What was life like for a kid like Peter in 1936 Russia (Soviet Union)? How was it different from your day-to-day life…and just as importantly, how is it the same?

Have your students research what life might have been like for someone outside their community. Think widely: consider different times, places, and cultures. Aim to find similarities this is the real joy!

You can make connections directly to Peter and the Wolf in a couple different ways:

• Listen to a recording in a different language. Can you still follow along in the story?

• Imagine a performance in a different time/place/culture. How is it the same/different? Have your students be specific!

Hint: this is a great opportunity to make cross-curricular connections. Check in with the classroom teacher: are they exploring different cultures through geography or history? Ask how today’s technologies allow us to experience worlds beyond the one we can physically touch.

Explore these common sayings together: 1) “Kids will be kids” and 2) “Nothing new under the sun.” What do they mean, and how do they apply to this story?

Though both phrases are sometimes used in frustration, there is a real power in thinking about how these phrases connect us through our humanity. What do these two phrases mean, and how do they help us understand our place in a wider human family?

What are some of the common traits of stories across multiple cultures? Can you identify archetypes—recurring characters, traits, plot points, or values—that transcend culture and time?

Ask students to share stories they learned when they were younger. What are some of the common themes across those stories? Make a day of it: share a few different stories, and then diagram on the board what things those stories held in common.

Hint: ask your classroom or language arts teachers to share in this! It gives your students a template or schema they can use when approaching new stories.

Connecting to current events

Prokofiev was born in the Donetsk region an area in Europe that was at the time under Russian control. In the later part of the 20th century, it became part of Ukraine, and today, it is one of the regions of Ukraine that Russia is trying to return to its control through its war.

The story of Peter and the Wolf is agnostic about geopolitics. It speaks to broader human values the joyful possibilities of childhood compared to the relative risk-aversion of adults, our dueling desires for adventure and safety, and our celebration of creativity in problem solving as well as in art. This is common in art: a desire to transcend political or power struggles and celebrate our shared humanity. (Though, of course, art and music can be and have been used as political tools for centuries.)

Far from existing in a vacuum, art and music are a part of our lived experiences. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, many Western orchestras responded by replacing Russian artists and composers on their programs. Yet, we celebrate Peter and the Wolf and many other works as ways to transcend time, place, and cultures.

This is a conundrum, and the conversations around these ideas are often complex and fraught. But, in the safety of your classroom, consider helping students develop tools for thinking about these ideas, and for having thoughtful, informed, and respectful conversations about the role of art and music in a broader world.

WHY THIS CHOICE?

Peter and the Wolf is filled with opportunities for great learning outcomes. One of my favorite outcomes stems from a question: “why THIS choice?!” It’s a great opportunity to go beyond labeling what Prokofiev does and start speculating as to not only why, but what the effect is on the audience.

Sound Affects

Help students make connections between SOUND and AFFECT as they listen to Peter and the Wolf. For example, in each of character’s themes ask your students to consider how the theme evokes a sense of that character. Prokofiev captured these characters in three main ways:

• Imitating the sound of the character the actual sound that character would make in real life. This is the highpitched trilling of the bird, the low and slow enunciation of Grandfather, and the duck-like sonority of the oboe.

• Capturing the motion of the character how it would travel in space. This is the march-like rhythm of the hunters, the quick flittering of the bird, and the stretching/slinking intervals of the cat.

• Evoking the feeling of the character the way that WE, the listeners, feel about the character. This is the terror of the wolf through dissonance, or the joyful sense of adventure in Peter’s jaunty theme.

Bad composer

Show how apt Prokofiev’s choices were by showing how terrible mine would have been! Timbre and instrumentation are the most obvious and straightforward, but there are all sorts of possibilities when you head down this path. Try these steps to get started:

1) Play each theme on the piano or via Wikipedia’s midi recordings. What do the characters lose without the instrument Prokofiev assigned?

2) Play the bird and/or duck two ways: with the grace notes/trills/articulations, and without. (Any instrument is fine.) What do Prokofiev’s markings add?

AFFECT (v), AFFECT (n), and EFFECT (n), OH MY!

How does a composer affect (v.) the affect (n.), and what’s the effect (n.) on the listener?

What we do affects (v.) others: this is at the core of Newton’s Third Law of Action and Reaction. The choices like instrumentation that Sergei Prokofiev makes in Peter and the Wolf affect what we hear and feel.

The affect (n.) of a piece speaks to its artistic qualities: the world it outlines, and its ability to, as Leonard Bernstein wrote, “make you an inhabitant of that world the extent to which it invites you in and lets you breathe its strange, special air.” That air? It’s the affect.

Of course, the affect (n.) of a piece has an effect (n.) on our students, the listeners. What’s the effect? Well, to complicate matters further, it often lives in the affective realm: the internal landscape, the “education in emotions…values, opinions, desires, wishes, personal knowledge, self-awareness, empathy, and understanding of others” as described by master educator Randy Swiggum. It’s in the affective that music shines.

Learn more about the power of affective music education through CMP, both in Illinois and where it all began in Wisconsin

3) Change the tempos of each character: slow bird but fast cat, or fast grandfather and slow Peter. How do the characters feel different now?

4) Try switching it up with whatever instrument you have on hand. What’s different when the grandfather is played on violin, the hunters on flute, or the bird on saxophone?

Tip: invite your school’s band/orchestra director or some advanced students to help you out with this so you don’t have to play all the instruments!

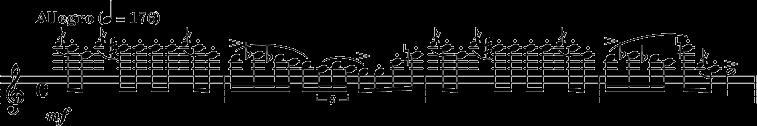

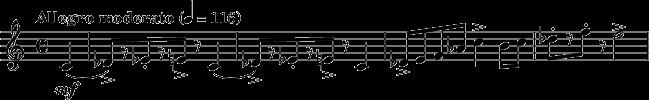

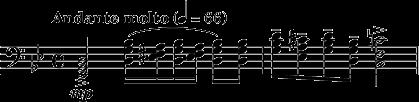

CAST

OF CHARACTERS

Scored for a chamber orchestra, this 25-minute work is as economical as it is colorful. Each instruments is introduced as a soloist, then interacts with others to tell the story just as convincingly as the words themselves.

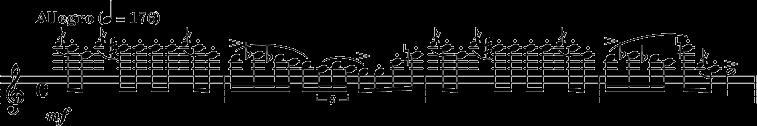

Bird / Flute

Bright, brilliant, and cheery, this flute solo is reminiscent of the trilling birds from Respighi’s La Primavera.

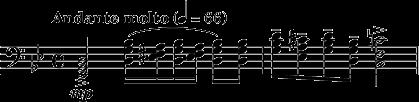

Duck / Oboe

With its unique timbre, slower tempo, and curly-cue melodic contour, the duck is a gentler and more elegant creature at home making circles in the water.

Cat / Clarinet

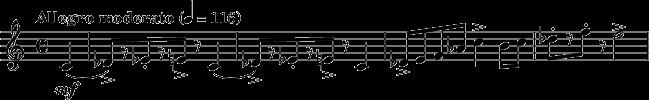

Its slinking and stretching theme is sneakily pitched in the low register of the clarinet…but always ready to pounce with an accent!

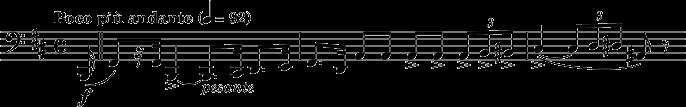

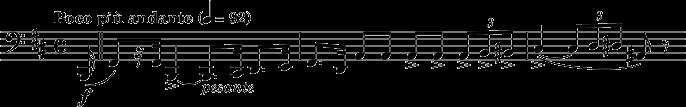

Grandfather / bassoon

Marked pesante with ponderous dotted rhythms in the low register of the bassoon, the heft of this character is unmistakable. Note the repeated pitches: a finger wag if I’ve ever heard one.

Wolf / French horns

Evoking our feeling about a wolf rather than its own sound or motion, this French horn passage snarls through dissonance, close harmonies, and a quivering repetition that seems to represent our tremors more than the wolf

Hunters / trumpet

The square, heavy, march-like footsteps of the hunters moving in lockstep are punctuated by the powerful shots of their rifles, played by the timpani, of course!

Peter / strings

With a jaunty buoyancy, Peter’s theme springs from one note to the next like a child—and appropriately so! Note the short articulations, punctuated accents on weak beats, and repetition of small motivic units.

BEYOND THE THEMES

Although this story is told through words and themes, the real joy is in how Prokofiev employs them. There are some truly wonderful moments of musical invention that go beyond simple restatements of theme. Here are a few samples that you could explore with your students to set the stage for the performance. Use these, or find your own the music is chock-full of them!

Lasso

As Peter lets his lasso down from the tree branch to capture the wolf, we hear the most fabulous unspooling of sound in the violins (who represent Peter).

Cat climbs the tree

When the wolf appears, the cat quickly scampers away and climbs up the tree and we hear it as the clarinet retreats quickly!

The zoo

The waltzing, carouseling 3/8 rhythm as Peter and his friends take the wolf to the zoo echoes brilliantly the fairground/carnival music of Russia.

Triumphant procession

As Peter and the wolf process into town, we hear Peter’s theme triumphantly recast in a different instrument the French horns! Why might Prokofiev have chosen this as Peter leads the wolf?

How much should we share before the concert?

Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf is so evocative, so clear, and so well written that it hardly needs an introduction. With such a brilliant piece, it’s immediately accessible and obvious to audience members and Prokofiev even gives us an introduction of the themes before the performance begins so that the “who’s who?” is perfectly clear. Do you need to listen before the performance?

No. This music is wonderfully accessible, and with the fabulous musicians of the Elgin Symphony Orchestra bringing it to life, you’ll hardly need an introduction.

But, as is so often the case, a little bit of pre-concert listening and exploration can help reveal new layers and depth to the story. And there is so much richness in Prokofiev’s score that we can come away with new information and emotions every time we listen. That’s the power of great art: every time we revisit it, something new is revealed, and we leave it slightly different than when we came to it.

It is multi-layered, richly crafted art that offers new meaning, insight, and discovery with every visit. That’s what keeps us coming back: the opportunity to widen our world of possibilities not just to “get it” and move on. Part of Peter and the Wolf’s staying power is that transports us from wherever we may be into the world of Peter, the young child and that’s true whether you’re enjoying it for the first time of the four hundredth.

WORD OF THE DAY

Leitmotif (n): a recurring theme within a composition (musical, visual, or literary) that is associated with a specific person, idea, place, or item. Examples include:

• Prokofiev’s use of themes in Peter and the Wolf

• John Williams’s approach in the Star Wars movies, such as

o The Force

o The Imperial March / Darth Vader

o Yoda

o Princess Leia

o And so much more as documented by musicologist Frank Lehman of Tufts University

• Richard Wagner’s use in his operas, most famously in The Ring Cycle

o Thoroughly documented

o Helpful described and demonstrated by the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra

• The Marvel Cinematic Universe, in this excellent video compilation

o Note #1: there description of the YouTube video gives you some additional options

o Note #2: the comment section is fascinating in that so many people identify and also desire more powerful connections between music and story

o Note #3: these movies are typically rated PG-13 please be aware if you use them with your students

FURTHER STRATEGIES AND ACTIVITIES

Your turn!

• Have students composer their own musical themes, either to Prokofiev’s characters or something of their own choosing (ideas/characters). Encourage them to develop at least two different themes/ideas, to compare and contrast possibilities. Students can perform their themes for the class, or they can write a description (i.e. what instruments / tempo / dynamic / harmony it would have) and share it. Encourage students to share both the theme and to explain how and why it is connected to their idea/character.

Peter and the Wolf 2023

• Prokofiev’s original is timeless…but that doesn’t mean it wouldn’t be different if it were written today. How might a storyteller and composer create an updated version of Peter and the Wolf in 2023?

Alternative takes

• There have been scores of adaptations of Peter and the Wolf a remarkable achievement for a relatively young fairy tale. Here are some possibilities to explore:

o Disney’s classic 1946 animated adaptation (difficult to find except on VHS—try your local libraries)

o The soundtrack to Disney’s storybook, and the storybook itself

o A humorous audio-only adaptation by Weird Al Yankovic

o A comedic adaptation of the text (only) by P.D.Q. Bach (aka Peter Schickele) called Sneaky Pete and the Wolf, which treats the story as a Western.

o Peter and the Wolf: A Special Report by NPR, in which famous NPR reporters and announcers treat the story as if it is a developing news event, alongside the music

SERGEI PROKOFIEV

Prokofiev’s gift for storytelling extended far beyond Peter and the Wolf and his educational work. With seven operas, eight ballets, and multiple film scores, he honed the craft of creating image and story through sound across his career, leaving us with such gems as Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella, and film scores to both Lieutenant Kijé and Alexander Nevsky, among many others.

A contemporary of Shostakovich (who was fifteen years younger), Prokofiev was forced to navigate the challenges of creating art in the Soviet regime for much of his life after having grown up with greater artistic freedom. With a well-established international reputation secure at the start of the Russian Revolution, Prokofiev left for France and then the United States, where he spent much of his adult life. Not until 1936 did he return to the USSR the very year he composed Peter and the Wolf. (Though this story is surrounded by tragedy: the work was commissioned by Natalya Sats, who was, by the time of the U.S. premiere in 1938, serving time in the Soviet gulags.) His initial forays into film scoring were wildly successful, as he captured the ethos and spirit of the Soviet propaganda.

Though persecuted less harshly than many of his younger colleagues, Prokofiev nevertheless suffered denunciations of formalism in the late 1940s. His death on March 5, 1953 was overshadowed by the death of Joseph Stalin on the very same day

STUDENT GUIDE: Concert Day!

1. Take your seats early. Watching a world-class orchestra like the Elgin Symphony Orchestra warm-up, tune, and get ready for the concert is a thrill. Don’t miss it! This is your chance to ask last-minute questions of your teacher, your classmates, and maybe even members of the orchestra.

2. Get comfortable. Do what you need to do to be ready for the concert: make sure your jacket and backpack are where they need to be, and that you’ve used the bathroom or gotten a drink of water. You won’t want to miss a minute of the performance, and you don’t want to distract other members of the audience, either.

3. Don’t pollute! Wait…what? Try to avoid “noise and visual pollution” during the concert. Think of it this way: if you went out into the forest on a wilderness expedition, you’d want everyone to be able to focus on…well, the wilderness, right? Talking would make it impossible to hear nature. Or, think of how hard it is to see the stars in downtown Chicago with all the lights. Help everyone else in the audience “see the stars” by keeping your lights under control. (This doesn’t mean don’t move just be thoughtful about when and how you do it.)

4. Take a device break. Leave your devices in your bags, off, or on silent or better yet, leave them at home that day. Devices are big polluters in the concert hall, and they make it hard for everyone to concentrate.

5. Watch the conductor. The conductor sends all kinds of secret messages to anyone watching carefully. Watch long enough, and you’ll start to pick up on the secret conductor/orchestra language; things like:

• Indicating which instruments should be most prominent

• Encouraging the orchestra to play louder/softer/faster/slower

• Leading to the big arrival points in the music

• Inspiring different “moods” from the orchestra

6. Listen! OK, this is an obvious one, but it’s important! Remember, orchestral music (like lots of art) benefits from deep, repeated listening. Have you heard these pieces before in class? Great what do you discover that’s new when you hear it live? Are you hearing them for the first time today? Awesome what surprised you the most about this experience?

7. Let the orchestra know you’re excited—applaud! There are lots of traditions in classical music concerts, but at our Ainsworth Concerts for Youth, you should applaud when the music stops and you want to show your enthusiasm and appreciation. You can also cheer on the musicians as they enter and exit the stage.

8. Talk about the concert when it’s over. This is sometimes my favorite part of a concert: the “post-concert chat” with other audience members. Ask them what they felt/noticed/experienced, and see how it compares to what you did. Remember, there isn’t a right or wrong answer each experience can be unique.

Questions? Ask your teacher or the ushers. They’re here to help!

Enjoy the concert!

Matthew Sheppard

Now in his third season with the Elgin Symphony Orchestra, Matthew Sheppard is thrilled to be on-stage for live performances at the Hemmens combining his twin passions: music and education.

As the Artistic Director of the award-winning Elgin Youth Symphony Orchestra (EYSO), Sheppard leads a team of dedicated educators in providing a comprehensive music education to 300 students and families annually. The comprehensive curriculum explored each year is designed not only to help student musicians develop artistically and technically, but also to prepare them for a future of complex ideas, creative risktaking, and leadership as global citizens. This hallmark “expert noticer” approach to music led to EYSO being named Youth Orchestra of the Year for 2020 by the Illinois Council of Orchestras, and to Sheppard being awarded Conductor of the Year in 2021.

Outside of Elgin, Sheppard serves as the Artistic Director of the Hyde Park Youth Symphony, as well as Music Director of the University Chamber Orchestra at the University of Chicago and the Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Company of Chicago. This year, he is the Guest Resident Conductor of the Northwestern University Symphony Orchestra, where he both directs and teaches conducting. He has guest conducted orchestras in North and South America, including the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional del Paraguay, the Champaign Urbana Symphony Orchestra, the Lake Geneva Symphony Orchestra, and the Blue Lake International Youth Symphony.

As a teacher, Sheppard inspires students to nurture a deep love and understanding of music and performing through his own passion, musicianship, and conducting. Sheppard is a committee member for the IL Comprehensive Musicianship through Performance (IL CMP) project as they encourage teaching with intention, and performing with understanding.

Sheppard studied with Donald Schleicher as a doctoral candidate in orchestral conducting at the University of Illinois, and before that earned his master’s degree in orchestral conducting under Gerardo Edelstein at Penn State University. During that time, he held appointments as Orchestra Director at Juniata College and Assistant Conductor of the Central Pennsylvania Youth Orchestra. Sheppard holds bachelor’s degrees in Liberal Arts, Music Education, and Violin Performance from Penn State where he studied with Max Zorin.

Elgin Symphony Orchestra

The Elgin Symphony Orchestra is one of the preeminent regional orchestras in the United States. Since its founding in 1950, the organization has developed a reputation for artistic excellence, innovative programming, and a deep commitment to the social advocacy and economic development of the diverse communities that it serves

Named “Orchestra of the Year” an unprecedented four times by the Illinois Council of Orchestras, (1988, 1999, 2005 and 2016) and winner of a 2010 Elgin Image Award, the Elgin Symphony Orchestra is respected for exceptional performance, innovative education programs, and community outreach initiatives.

Believing music and the arts have the power to inspire individuals, support communities, and enrich society, the ESO launched Elgin: Home for the Holidays, and has partnered on other events with Rotary International, Feeding Greater Elgin, Sherman Hospital, Downtown Neighborhood Association, and the Elgin Area Chamber of Commerce. In 1987, the ESO began Kidz Konzertz, now called Ainsworth Concerts for Youth, a children’s program that currently draws nearly 9,000 youth from nearly 60 communities. The ESO’s Musicians Care program, which began in 2010, takes musicians out of the concert hall and into the public and patient spaces of Advocate Sherman Hospital in Elgin every Thursday, including holidays, from 12-2 pm. In addition, our musicians visit Advocate Good Shepherd Hospital in Barrington every first and third Wednesday from 12-2 pm. In 2014, the ESO partnered with Gail Borden Public Library to provide free Family Concerts, and extended its Listeners Club to the Greenfields of Geneva.

Primavera, Sandro Botticelli (late 1470s or early 1480s)

Primavera, Sandro Botticelli (late 1470s or early 1480s)

A chipping sparrow

A chipping sparrow