Introduction and Prelude

Creating an Exhibition History

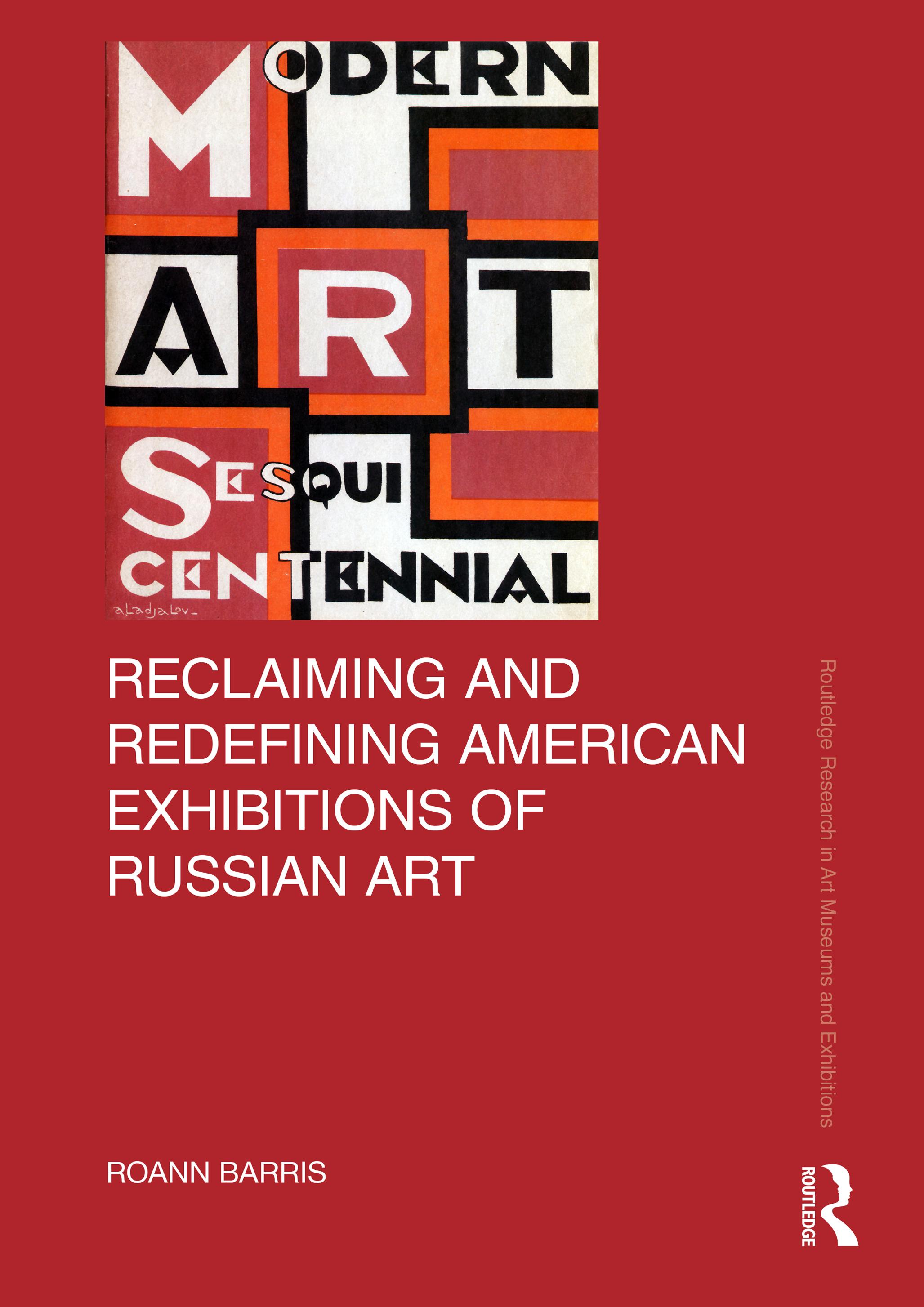

Where does one start a history of a century of exhibitions of Russian art in the U.S.? And why does it matter – does it reflect the history of museums in the U.S.? Or tell us something about the meaning of exhibitions? Perhaps both, but before trying to answer those questions, it might be useful to know why the first question is more interesting than we might suspect.

This project had two beginnings: this researcher’s attempt to explain the apparent influences of Russian art on late 20th century American art,1 when opportunities for those artists to encounter Russian art in English language publications and museums were still rare, and a more accidental beginning when a speaker at a workshop hosted by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the New York Public Library nonchalantly referred to an exhibition of Russian art at the gallery in the Grand Central Palace in 1924. On one level, I wanted to know whether the connection between Daniel Flavin and VladimirTatlin was deeper than the title of one of Flavin’s works. Or, in the same vein, why did artists like Alice Aycock and Miriam Schapiro make visual and conceptual references to Russian constructivist theater? Could it be argued that Camilla Gray’s book was not the only source of information about Russian avant-garde art for late 20th century American artists? The second motivation, the one that more directly culminated in this work, reflected my astonishment in learning about the relatively unknown 1924 exhibition.

I was astounded on two counts: although a New Yorker, I did not know that there had ever been an art gallery in Grand Central station, and in my own study of Russian art, I was unaware of any exhibitions preceding the last quarter of the 20th century. As early as the 1920s? My opening question suddenly seemed to hold the key to knowing why it mattered. But this would involve more than simply chronicling the dates of these exhibitions. It would be necessary to know what art was included, where these exhibitions were located, who arranged them, who saw them, and what impact they had on the public. Clearly, my first question is not as straightforward as it might seem to be as it implies that the resources to do such a study exist. But do they?

In search of an answer to at least one of these questions, I turned to the encyclopedic multi-volume work by Bruce Altshuler, Exhibitions that Changed Art History.2 Because volume one preceded volume two by several years and had an earlier chronological focus, the first volume Salon to Biennials seemed to be a good starting point. A unique compendium of exhibitions with archival sources and photographs when possible, it is unmatched as a history of exhibitions. The catch, however, is the phrase “that changed

art history.” That assessment might be difficult to make, if not too subjective and timelimited to attempt to make it, but it also tells us before we open the book that Altshuler will begin his history with exhibitions that did not take place in museums or even at the Salon or official expositions. The artist-organized, independent exhibition is the beginning of a change in how the institutionalized history of modern art will be told, a change that would have been much slower to come without the challenge to the Salon and the Academy of Art. Although a more monumental history than the one I seek to uncover, it does suggest that my early reluctance to look to international expositions in the mid-19th century may have been misguided. Were the palaces of art at these fairs the earliest stages of an attempt to use art to influence the American reception of Russian culture?

If we return to Altshuler’s history of exhibitions, we find that it is premised on some basic changes in exhibition types.3 Traditionally, he observes, exhibitions were based on the collections of the founder of the museum. Over time, they began to be focused on movements or styles as someone, a critic or curator, wanted to make a statement about changes taking place in the world of art. It isn’t until the 1970s or thereabouts that exhibitions began to be organized by theme, selecting and using artworks to communicate an idea or concept that might not have been on the artist’s mind. The thematic exhibition driven by the curator’s conception becomes a driving force in the world of museums, biennials, and art fairs for several decades at the end of the 20th century. This will not be met favorably by many artists. As Daniel van Buren wrote, “More and more, the subject of an exhibition tends not to be the display of artworks, but the exhibition of the exhibition as a work of art.” Buren was not the only one to hold this view, and it wasn’t only artists who felt that their work was being misused. Critics also began to describe exhibitions in comparable terms. Thomas McEvilley wrote about an exhibition in Venice that it was “a kind of megapainting[sic] by the curator, incorporating the works of others as colors on its palette.”4 Will this description be true for some of the mega shows of Russian art mounted by the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan museums in the last decades of the 20th century? Perhaps less applicable to my exhibition history, these changes in the nature of the exhibition reflected another change in curatorial practices. Rather than selecting artworks to include in a show, curators were increasingly inviting artists to contribute. Although it is not clear that we can speak of curating when discussing expositions, the change from art works to artists as a method of selecting work may be notable. In either case, exposition or museum, the curator or organizer did not necessarily see the works until they were all delivered and the installation of the show may have become a collaborative event. Clearly, some artists were more comfortable with this approach than others. This development is accompanied by another one in which the exhibition may be taking place in multiple locations at once and lasting only for one day, and the catalog is the primary vehicle for experiencing the entirety of the exhibition. This last change is something we will observe as we follow Russian art exhibitions through the century. We will also observe some developments that did not enter into Altshuler’s overview: the intrusion of governmental organizations in determining what works can and will be exhibited, along with a decidedly political overtone to certain exhibitions. One incomparable resource for this feature of my exhibition history is unquestionably Treasures into Tractors: the Selling of Russia’s Cultural Heritage, 1918–1938. 5 Without going into this development in depth at this point in my narrative, the one thing we want to note for future exploration is how the attempt of the Soviet government to create an international market for Russian art and antiques influenced, if not outright determined, what Russian art would be available for American exhibitions when my history reaches the 1920s.

But before reaching that part of my history, I return to one of my opening questions: the first exhibition of Russian art in the U.S.. Presumably not as complicated a question to answer as the more subjective question of where we start, especially if we can agree on the meaning and boundaries of exhibitions, but that, too, may not be as straightforward as one expects. Indeed, we may not even agree on the meaning of Russian art. As Rosalind Blakesley and Susan Reid ask in the introduction to Russian Art and the West, what is subsumed by the phrase “Russian art”?6 For my purposes, the first question that arose was the use of “Russian” versus the use of “Soviet,” especially when both can meaningfully be used in the same sentence. Whereas that question might be resolved by referencing the dates of the works in the exhibition or the name chosen by the curator or museum, doing so may have more value to art historians today than it did in the early years of this exhibition history. As the introduction to Treasures into Tractors tells us, after the revolution, the Soviet government’s concern was the creation of an international market for Russian arts and antiques. Exhibitions may have functioned primarily as a means of generating interest in items that could be sold, and the choice between calling something Soviet or Russian would probably have been based on something other than the date of the exhibition or the curator’s preference.7 The second question was more troublesome. Given that my initial focus was exhibitions of the avant-garde, a term which is not easily delimited and that excluded exhibitions of most pre-revolutionary art and religious art, and therefore many of the earliest exhibitions of Russian art, I had to determine whether my interest was the exhibitions themselves or artistic encounters with the avant-garde.8 After recognizing my true focus and having decided not to exclude art that wasn’t avant-garde, the question about Russian versus Soviet was still not resolved. Was it as simple as saying anything before 1917 would be called Russian and after that date Soviet, knowing that it might not correlate with how the Soviet government labeled art? Or do we decide to use the term that the artists, collectors or curators used when talking about their art, perhaps eliminating one source of confusion? What to do, then, with a collector like Christopher Brinton? He began his collection with a 17th century Russian icon, and because he believed that changes in art reflected an evolutionary process, rather than one of revolutionary change, it is not likely that he would have been inclined to change the name of his collection from Russian to Soviet. The distinction of concern to Brinton appeared to be one of nationality; thus, the artists who had emigrated to the U.S. were Russian émigrés, whereas the artists who remained in the Soviet Union were Soviet artists, a distinction that will be important in the exhibitions he helps curate.9 Whether émigrés or not, the artists themselves were not consistent in their use of Soviet or Russian, a decision that might reflect propagandist goals, reasons for emigration,10 and/or geographic location of the artist. Some of the artists traditionally called Russian were actually from regions that were now republics in the Soviet Union but had been provinces in the days of the Russian empire.11

Then, of course, there is the question of what does the term exhibition subsume. Should we, for example, include exhibitions in a Russian pavilion at a world’s fair in the U.S.? Does an exhibition of artworks that were somehow lost, stolen, and intended to be sold count? If the person illegally trying to sell art works calls his 1906 sale “Russia’s First Fine Arts Exposition in America,” does this count? Do we have any restrictions on genres or media in this comparison? Do the actual art works have to be present or are photographs and reconstructions acceptable? Even a question that would seem to be straightforward and easy to answer is as provocatively challenging as any study of exhibitions and museums. But when these exhibitions involve art from a country that was

ruled by a tsar, until the revolution to overthrow him finally succeeded, and the country where these works will be displayed does not clearly acknowledge the existence of the country that presumably owned the art works, finding the answers may require rejecting any that at first seem to be obvious and correct. There is yet one more question that may be as challenging and potentially the most intriguing of all: What motivations lay behind these early exhibitions? What role does art play in promoting or instigating international dialogue, if that was ever a goal?

To preview some of my findings, this research shows how curatorial goals often determined which artists were associated with which movements, even when these associations may be contradicted by historical fact. To a large degree, official Soviet agencies and American commercial dealers were often more influential than curators or specialists in Russian and Soviet art. Indeed, goals for the earliest exhibitions had less to do with the art works than with such issues as raising money for presumably starving artists and promoting a bridge between two cultures. To be sure, sales of Russian art were often written about in the newspapers, often included in a lengthy column that named several exhibitions and sales roughly occurring at the same time and in the same location. Whereas some curators strove to associate the avant-garde with spirituality or to rouse public support for starving Russian artists, dealers, on the other hand, were often buying fakes or at the very least promoting their collections as representing periods and types of art incorrectly. Collectors, of course, might do the same as dealers, albeit for different reasons. Robert C. Williams, in his research on the interactions between Russia and the U.S., observes that sales of Russian art, and in some cases European art owned by Russians, took place before the Russian revolution and continued long after, largely motivated by the monetary needs of either merchants or the government. By the 1920s, the goal of sales appeared to change slightly to a more diplomatic goal, although economic goals remained.12

Whether sales or exhibitions, these events received widespread newspaper coverage. The role of art as a political tool in shaping one country’s perceptions of another becomes surprisingly relevant, especially when government agencies control sales and loans of art works, as was the case in the Soviet Union. To be sure, the political use of art will not be as prevalent in the early 20th century as it will be later, although it might be an oversight to ignore the deliberate use of culture in shaping public opinion at any point in time. Other questions emerged as my study progressed. What role was played by magazines such as the Little Review and the graphic artists who worked for them? How did émigrés fit into this growing history? Despite Alfred Barr’s early travels to the Soviet Union, the newly formed Museum of Modern Art did not become a leader in the sphere of Russian art until recently, and even now, it might be said that its limited contribution to this exhibition history is perplexing. Thus, I ask, what goals and beliefs provided the groundwork for these exhibitions, and in particular, the early ones? How did this exhibition history shape American understanding of the Russian avant-garde, and one might boldly say, of Soviet and then Russian culture?13 Once again, it is unlikely that there will be a simple or single answer to questions such as these. For comparison, we might look to Eleonory Gilburd’s recent and provocative study of Soviet perceptions and interpretations of western culture primarily but not exclusively during the Thaw.14 In an interesting inversion of the 19th century American critical response to Russian art of the 19th century, Gilburd tells us how the Russian spectator and critic alike believed that abstract art of the mid20th century signified capitalist degeneration and American crudeness so serious it could only be considered a barbaric, viral infection. Gilburd and Kiril Chunikhin both show us

Introduction and Prelude 5

how the Soviet Union’s reception of the American artist Rockwell Kent was directly contrary to his reception in his home country.15 The dichotomous reactions to realism and abstraction in the late 20th century cannot of course be compared to American responses to realism in the 19th century, when, as we shall see, viewers believed that Russian art was seen to confirm the cultural backwardness and barbaric nature of the Russians, but the tendency to see in art a reflection of the level of culture in a foreign country may actually tell us more about spectator responses to art than about the country that produced the art.16 Still, we might want to reckon with the negative Soviet attitude toward abstraction, whether their own or from another culture, that doesn’t seem to go away.

Before turning to the exhibitions, we should note that all of the previous questions will be problematized by the reality of changes in museological theory and the role of governments in facilitating or complicating intercultural cooperation. As a result, this story is far more complex than a chronological listing of exhibition names and art works. If, however, we choose the chronological beginning, and we don’t eliminate non-museum exhibitions, we begin with American expositions in the 19th century. One question can be answered: this is not a history of museums. They will be important but the earliest exhibitions in this history did not take place in museums.

Prelude

Russia participated in two world’s fairs held in the U.S. in the 19th century: the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 and the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Unlike the rather more preposterous events we will find associated with the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, where Russia did participate although not on an official basis, these earlier fairs received art works that were primarily the works of the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers) artists. The selection of works for international expositions was generally organized by the Imperial Fine Arts Academy. Initially, representatives of the Academy selected art works, rather than artists; by 1876, they were approaching artists and giving them the opportunity to select works of their own for the exhibition. By 1878, the year of the Universal Exposition in Paris, the Academy focused its invitations on the Peredvizhniki who refused to participate in that exposition. In their place, private collectors such as the Tretiakov family offered to lend works from their own collection. For the Chicago Columbian expo in 1893, Tsar Alexander III offered works from his collection. Sales of works were not the motivation behind Russia’s involvement as many of the works that were included already belonged to private or imperial Russian collectors who agreed to lend their works to the exhibition planning commission. Indeed, Russian participation in these expositions was not usually based on the belief that it would help business or trade, regardless of whether the involvement was in the area of machinery, agriculture, or art. In general, motivation for participation seemed to be the belief that this would help Russia’s image abroad. In the weeks leading up to the Philadelphia Centennial exposition in 1876, Russia was not prepared to participate but reversed its decision after receiving an invitation from President Grant (sent to all potential participating countries) and after Great Britain was seen to be encouraging the Ottomans to avoid a peaceful settlement with the Balkan Slavs, making participation a diplomatic step in building relations with the U.S.. Newspaper articles in popular papers along with the Ministry of Finance’s communication with the Tsar ensured in both cases that participation was not recommended as a means of helping industry but to provide evidence of Russia’s friendly attitude toward the U.S.17

Of the three American expositions with Russian involvement, the number of Russian exhibitors in Chicago far exceeded those in Philadelphia or St. Louis. Although the international Paris expo of 1900 had the largest number of exhibitors, Chicago was the only American expo that approximated the numbers in the other European expos. However, it is not always possible to determine from the numbers of exhibitors if these refer to art exhibitors or other types of exhibitions in the fairs.18 Because the Philadelphia expo was recognized as a celebration of a national historical landmark, the Chicago expo may have more to tell us about the organization of fine arts at these expos. I will therefore proceed slightly out of chronological sequence.

Although these are the earliest documented exhibitions of Russian art in the U.S., they were not the first occasions of Russian involvement in international expositions. In the period covered by David C. Fisher in his study of Russian involvement in worlds’ fairs, Russia participated in 11 international fairs during the period from 1851 to 1900, including the American expositions. In the case of both Philadelphia and Chicago, a member of the Council of the Ministry of Finance served as the general organizer for the Russian department at the fair, while the Fine Arts Academy was responsible for organizing the fine arts section. In fact, in the Fine Arts section of the Chicago Exposition catalog, the Russian section is titled “Russia. Exhibit of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts.” Of 131 works listed on these pages, 15 were sculptures, 2 were carvings, and 3 were watercolors. This breakdown of media was apparently not different from earlier expos: oil paintings generally dominated the art works, while the number of art works largely outnumbered exhibitions of machinery.

The fact that the Imperial Academy not only organized the Russian selection but considered it an exhibition of the Imperial Academy would explain the dominant presence of Wanderers in the 1893 exposition as they were leading artists and newly appointed professors in the Academy at that time.19 Of course, they may have regretted their refusal to participate in the previous Paris expo and wished to make up for that decision. When asked if they wanted to participate, artists were informed that they would have to deliver their art works to the Academy for a special exhibition prior to the selection of those works that would be sent to Chicago at the expense of the Academy. Anna Zavyalova, in a rare study devoted to the Chicago exposition, suggests that the art works sent to the fair were chosen to counter negative images and views of Russian life propagated by journalistic accounts such as those recently published in George Kennan’s 1921 book on Siberian exile.20 Without accessing and reading the correspondence of artists to the selection committee, it is difficult to know precisely why each artist chose the works they did and what might have been overlooked. The decision was largely in their hands and may have reflected little more than the artist’s ability to borrow a work from the present owner and get it to the Academy in time for shipping. Certainly, some of the letters and documents that Zavyalova read in the Russian archives do not point to a deliberate attempt to counter what was believed to be negative propaganda about Russia.21 Siemiradzky, a Polish artist who studied and became an academician at the Russian Imperial Academy, ranked his preferred paintings for the exhibition by value, based on size and subject, which in most cases was either classical or biblical. His first two choices were apparently deemed less valuable by him than the two paintings that were sent.

Many of the works that did make it to Chicago featured historical events, but in some cases they were paintings that focused on the abolition of serfdom.22 The English language catalog prepared for the fair emphasized, when possible, how such paintings could be seen as displaying improvements that had been made in the lives of peasants.

The Russian commission’s goal of displaying a high level of Russian art along with an image of Russian life as not being uncultured and semi-barbaric may not have been precisely what American critics perceived. Critical responses were mixed, focusing in some cases on what could be intuited from the subject matter and in others on insulting comments about the artists’ techniques. These factors did, apparently, become intertwined as those critics who did not like the subject matter, finding it grotesque and uncivilized, did not like the paintings. All the same, before looking in greater depth at these reviews, it must be noted that the exposition as a whole, while a huge popular success, was not unambiguous about the place of non-American and non-western European cultures. Thus, although these expositions may have been among the earliest acquaintances of Americans with Russian art, they may have been clouded with biases that are somewhat less likely to predominate at a museum exhibition.

Judging from the floor plan of the Palace of Fine Arts, France may have had more contributions to the Palace than any other country, including the U.S. The U.S., Great Britain, and Germany, all had a comparable amount of space. A block of the same size as those countries had was divided among Russia, Spain, Japan, and Holland. Thus, the long rectangular hall that displayed Russian art may have been crammed with paintings that were unjustly (or deservedly) accused of being excessive in size and were perhaps no larger than the paintings included in the more spacious rooms for art of the U.S. As noted previously, the catalog lists 131 art works, most of which were oil paintings, plus a smaller number of water colors, sculptures, and wood carvings in 2 galleries. The English-language Russian version of the catalog lists each artist with his works, identifying the present owner, and occasionally including a narrative explanation of the scene. In some cases, these were historical scenes but in others, the paintings with descriptions were landscapes or architectural monuments. More than a page is given to a detailed description of the history and architectural style of “interior view of the Cathedral of our Saviour[sic] in Moscow” by Feodor Andreievitch Klagess[sic].23

Of the critics cited most often for their comments on this exhibition, Hubert Howe Bancroft was inclined to focus largely on subject matter, often providing detailed descriptions of what he saw, with some additional comments about the artist’s palette and overall technique, which, for Bancroft, was closely tied to the descriptive commentary. He begins his discussion of the Russian section of his book with a critique of size and some relatively condescending remarks about how the Russians might judge quality:

To say of a collection of paintings that it is marred by excess of strength may appear somewhat of a paradox; yet, if the truth be told, this is what must be said of the Russian paintings, another fault in which is their phenomenal dimensions, so that looking for the first time on these mammoth canvases, we are thankful the exhibit is a small one, for a few such should have exhausted the entire space at the disposal of the management. The best feature in the collection … is that it deals largely with national subjects, and if only it dealt with them in a true artistic spirit …. From a Russian point of view it is doubtless of excellent quality; but art is universal ….24

While seeming to imply that therefore, we should all agree on the artistic quality of a work, this did not appear to be the case as Bancroft continues to criticize modeling and color in many of the paintings while praising them for their realistic approach, devoting six pages to detailed descriptions often accompanied by reproductions of the art works. Indeed, perhaps we might question Bancroft’s approach to art criticism as relying too

much on description. He could not write about each of the more than 100 works but did write about many, providing elaborate descriptions that included his reading of the narrative and the emotional quality that the artist was, according to Bancroft, trying to convey. Thus, some artists appeal to our sympathies, while other artists communicate a noticeable air of sadness even in those scenes that are portraying cheerful moments. He writes that “in ‘Sunday in a Village,’ by Dmietrieff Orenbursky, when peasants are trying to make merry, we can see that they are only trying, and with indifferent success.”25 This does not read as criticism from Bancroft but as praise. The Chicago exposition was large and important, particularly from the perspective of its architecture and implications for urban planning. It did not appear to be a failure with respect to the exhibition of fine arts, and it is likely that the Russian galleries were well visited. Popular magazines did have occasional articles about Russian art, and Bancroft was not the only American to write about the Russian art section, although it is difficult to track these materials today. More are available in Russian archives. Overall, Zavyalova’s article is probably the most complete discussion of Russian involvement at the Chicago expo that we have today – as she observes, Russian writers contributed to the various sections of the larger expo catalog, attempting to explain scenes to the American audience and probably romanticizing the narratives. Bancroft and several other American writers may have been influenced by this tendency to explain and romanticize, rather than analyzing the art work from a more complete art historical perspective, if one were desired. Marian Shaw was more concise than Bancroft but essentially provided a paragraph long, descriptive walk-through. Her comments begin by observing that “Russia’s display is a marvel and a revelation to those who have looked upon the vast empire of the Czar[sic] as but one remove from barbarism” and goes on to commend several paintings for their luminous and lovely effects. A journalist rather than an art critic, she defers to the critics’ assessments of the works in this “superb collection” from the Imperial Academy and one work (a painting by Repin) from the emperor, “pronounced by the critics the artistic gem of the collection.”26

At most fairs, fine arts were never as popular as machinery and other parts of the fairs. Among the arts, painting was the most important at all the fairs, although not always the most popular. At the earliest expos, the organizers for each country initially focused on living artists only, until they began receiving complaints from the owners of art works that were lent to the expos time and again. This was soon remedied by the inclusion of art by artists no longer alive making art the only part of these expos that sanctioned an exploration of the past – a factor that may have detracted from the interest of audiences who wanted to know the present-day worlds of the cultures included in the expositions. If not overwhelmingly popular with the average spectator, they were not more so with artists. Paul Greenhalgh suggests that the influence of the fine arts palaces at the world expositions on new and professional artists was very slight; this may have been the effect of including a large amount of recent academic art in comparison with a more limited amount of work by old masters; they did, however, introduce many artists to visual arts and ethnographic displays from countries that were not usually seen in museums.27 Philadelphia, an exceptionally large fair, had three buildings for art: the Art Gallery (Memorial Hall, the Philadelphia Art Museum today), the Art Annex, and the Photographic Hall. Apparently, the organization of the art gallery was unusual, seemingly not only using American art as the most central in the plan but giving space to foreign art works that were owned by American collectors. The floor plan for the main gallery was divided into numerous small rectangular spaces of which some countries received more than one. Russia is indicated in this plan, although not in the annex that was also

Introduction and Prelude 9 subdivided into more than 40 spaces. The first international exhibition of art in the U.S., 20 countries submitted work, not quite half of the total number of countries that participated in the fair. Several countries submitted several 100 works apiece; Russia submitted 91. Although Rydell does not discuss the layout of Memorial Hall, he does note that exhibits in the main building were organized by race. “The United States, England, France and Germany were given the most prominent display areas,” which does appear to be true of the art building as well. Remaining spaces in the main building were divided between countries and colonies representing the Latin races, Teutonic, and Anglo-Saxon. The division of space in the art gallery, with the exception of the large spaces in the central hall, appeared to be divided with no apparent reference to the races as described above. Kelsey Gustin attempts to account for the unorthodox lay-out of Memorial Hall giving more attention to it than Rydell does, eventually concluding that “the resulting plan for the Art Annex created an incidental equalizing effect between nations,” enabling visitors to pass easily from one country to another. This might appear to be true given that the Annex was divided into seven horizontal rows intersected by nine vertical rows, creating a large number of small spaces before some were joined together to give certain countries more space. Russia was not included in the annex, perhaps because it did seem to have a smaller number of works in the exposition than many of the other countries. Although Russian-applied arts and jewelry were highly praised in Philadelphia, it is difficult to find reviews or critical writing about the art works in the fine arts part of the 1876 exposition. One might guess that given the importance of the centennial date to the U.S., writers were more likely to address the overall importance of the event or works that likewise celebrated the centennial and the American spirit.28

The Louisiana Purchase Exhibition of 1904 was the largest international exposition yet, far surpassing Chicago. Rydell discusses the expression of themes of American imperialism at this fair but for a discussion of the unusual incident related to Russian art, a key source at this time is the work of Robert C. Williams. Russia’s participation in this exposition was disrupted to some degree by the Russo-Japanese war that prevented full and official Russian participation, although 600 works did arrive too late to allow for a well-planned installation. It contributes little to our exhibition history for several reasons. The collection of 600 paintings was large, focused primarily on the Wanderers but included some of the emerging World of Art and art nouveau artists, the space was again too small but in this case over-shadowed by the pavilion next door to the Russian pavilion. The events that followed the exposition complicate its place in this exhibition history. Edward Mikhailovich Grunwaldt, the Russian councillor of Commerce who had arranged the exhibition, guaranteeing complete coverage for any lost objects and the return to St. Petersburg of work that was not sold, subsequently arranged to have an exposition on Fifth Avenue in New York City for a sale he called “Russia’s First Fine Arts Exposition in America.” Due to the dishonest representation of this event that had been intended not as an exhibition but as a sale, the works were seized by the U.S. government and placed in storage where they languished as unclaimed merchandise for approximately six years. Before they were seized, some were auctioned off at low prices but no duties were paid. Eventually, a series of complicated transactions involving numerous people led to a few sales, many damaged paintings, and the placement of some of the art in museums. The upshot of this event was a contribution to the clogging of channels between American and Soviet traders and buyers and no further American exhibitions of Russian art until the 1920s.29 Williams identifies 1924 as the year when these exhibitions begin, although in fact the Brooklyn Museum exhibition of Russian art was held in 1923,

as he also notes. Wiliams’ differentiation here appears to be between exhibitions or sales that were supported or initiated by the Soviet government or officials, and intended to encourage trade and recognition of the Soviet Union (the 1924 exhibition), as opposed to exhibitions and sales organized and promoted by Americans (1923).

Despite the unfortunate circumstances surrounding the New York event, the so-called exposition was not ignored by all writers, one of whom (Keyser, as we have seen) wrote about the shipping problems faced by Russia and the art that may or may not have been in the exhibition since he wrote in advance of the opening. Coming at the same time as the exposition was a visit of the Russian Symphony Orchestra and other cultural groups. Taken together, Christian Brinton found this an auspicious moment to write “an informing and sympathetic article,” as the Literary Digest described it, for Appleton’s Booklovers’ Magazine. 30 The suggestion by the unnamed author of the note in the Digest as to Brinton’s inspiration may need to be seen in light of the fact that Brinton had become acquainted with Grunwaldt, the Russian Commerce Minister who not only arranged the original St. Louis Event but had invited Brinton to a diplomatic dinner for the exhibition.31 Brinton began his article with a discussion of Russian literature, history, and an overview of the horrifying events that did not suppress the beauty and radiance of Russian art and life before he turns to an explanation of how the St. Louis exposition of Russian art found its way to New York. The substance of his article is more of a cultural history with occasional reference to some of the paintings in the exposition than a critique of the exposition itself. Some of the paintings received detailed descriptions of the scene and narrative as understood by Brinton, several are accompanied by reproductions of the art works, before he concludes his largely appreciative study of Russian culture by saying that the anarchy caused by the Mongol invasions of recent months will not suppress or obliterate the culture of the country. Although his motive appears to be other than that of acknowledging the legacy of the St. Louis expo, it did address the expo before proceeding to celebrate the realist tradition of Russian art and asserting its connection to the values and instincts of the Russian people. Near the end of his lengthy discussion, he writes that “the salvation of Russian art, as of all art, lies in a saving sense of nationalism. It is particularly true of Russia that her best expression flows direct from the sap of popular life and legend.”32 Brinton’s conclusions about the presumably or socalled first Russian exhibition of fine art in the U.S. may have more to tell us about his own theories of art than the exposition itself. Because Brinton did not have any involvement in the planning or installation of this exhibition, we cannot look at this as an example of how a collector may have influenced the picture of Russian art that is conveyed by the exhibition. But Brinton will have a hand in several exhibitions that come soon in the early period of actual exhibitions located in museums. What other conclusions can we take away from this event? Although some of the works were purchased, these purchases did not seem to be the start of a strong interest in Russian-American trade in the arts, and accurate valuation of the art works involved seemed less important than the avoidance or collection of tariffs. The Soviet government did want to cultivate American sales but the 1920s was disappointing in this respect.

In contrast to the 1920s, when exhibitions in museums and galleries do take off, the period of world expositions can be ambiguous with respect to the interpretation of goals and the identification of which artists and art works were included. Whereas it may be too facile to assume that these questions will ever be easy to resolve, the abundance of reviews, paperwork, and relevant resources make the decade of the 1920s the true beginning to a history of American exhibitions of Russian and Soviet art. Thus, although the

Introduction and Prelude 11 prelude rightly ends in the first decade of the 20th century as we turn to the contributions of first, Christian Brinton, and second, Katherine Dreier, and then the Soviet government for what can truly be called the beginning of the history of a century of exhibitions of Russian and Soviet art in the U.S., another consequential factor has entered the picture: the role of governments in planning exhibitions and sales. Whereas the Soviet government did want to create an international market for Russian art and antiques, and did initially encourage exhibitions as a means of generating interest in these products, marketability is a different motive for exhibition planning than cultural relations. Many of the items chosen for sale were not necessarily Russian to begin with and rarely reflected avant-garde developments.33 The early interest of Soviet agencies in planning exhibitions for travel ends in the 1920s, although the interest in sales continues. Nonetheless, the lack of involvement of Russian museums in planning American exhibitions undoubtedly impacted the range of works that could be seen in this country, but was it exclusively for the worst? The answer to that question remains to be seen. Yet, it must be noted that through the efforts of VOKS, recognized as the USSR Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, the goals of scientific and cultural relations exceeded sales and led to a variety of exhibitions in the period between 1925 and 1928. Forty exhibitions in the arts were held, with an emphasis on posters, printing type, and books, among other media, but most of these were in European countries, with Germany and England recipients of more than other countries named in the report from October 1928. A Modern Art Exposition in America is also mentioned and the 1928 International Press Exhibition traveled from Cologne to four other cities, including New York.34 The role of VOKS and the friendship societies formed in other countries obviously is important and cannot be overlooked.

Notes

1. The use of Soviet versus Russian is the subject of a later paragraph. On my use of “American,” I refer only to the United States.

2. Bruce Altshuler, ed., Salon to Biennial – Exhibitions that Made Art History, Vol. 1: 1863–1959 (New York and London: Phaidon Press, 2008).

3. Introduction, Biennials and Beyond – Exhibitions that Made Art History, Vol. 2: 1962–2002 (New York and London: Phaidon Press, 2013), 11–24.

4. Exhibitions, p. 15 for both quotations.

5. Anne Odom and Wendy R. Salmond, eds., Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia’s Cultural Heritage, 1918–1938 (Washington, DC: Hillwood Estate and Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009). Treasures into Tractors preceded by only a few years the English language version of a comparable study of the disasters tracked in Odom and Salmond’s book: Natalya Semyonova and Nicolas V. Iljine, eds., Selling Russia’s Treasures. The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art, 1917–1938, translation from Russian by Andrew Bromfield and Howard M Goldfinger (Paris: M.T. Abraham Center for the Visual Arts Foundation, 2013). It is perhaps most significant that the contributions of each book to understanding the extent of Russian cultural losses are unique and non-duplicative.

6. Introduction, “A Long Engagement: Russian Art and the ‘West’,” Blakesley and Reid, eds., Russian Art and the West (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007), 3–20.

7. Preface to Treasures into Tractors, xiii–xv.

8. See an early article by John E. Bowlt, “Art in Exile: The Russian Avant-Garde and the Emigration,” Art Journal, 41: 3 (Autumn 1981), 215–221 for discussion of the various uses and meanings of avant-garde and why the term may be useful or obfuscating.

9. Brinton will be of interest later in this chapter, as will the tenuous distinction between Soviet and Russian. For his interest in evolutionary theories, see Mechella Yezernitskaya, “Christian Brinton: A Modernist Icon,” Baltic Worlds, XI: 1 (2018), 58–64, and Andrew J. Walker,

“Critic, Curator, Collector: Christian Brinton and the Exhibition of National Modernism in America, 1910–1945,” dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1999.

10. Although emigration will obviously be an important and influential concept in my study, it will not be a major focus for my work as it deserves and has received book-length studies. These include Marilyn Rueschemeyer, Igor Golomstok, and Janet Kennedy, Soviet Emigré Artists: Life and Work in the USSR and the United States (Armonk, NY and London: M. E. Sharpe Inc., 1985); Christopher Flamm, Henry Keazor, and Roland Marti, eds., Russian Emigré Culture: Conservatism or Evolution? (Cambridge Scholars Publisher, 2013).

11. Irene R. Makaryk, April in Paris: Theatricality, Modernism, and Politics at the 1925 Art Deco Expo (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018) addresses the confusions inherent in this distinction and how they played into the response to Russian and Soviet work at the expo. As far as I can tell, there is no single or simple answer to this question; whenever possible, I will use the terminology as it was used in the exhibition I am discussing.

12. Williams, Russian Art and American Money, 1900–1940 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), 27.

13. In most cases, exhibitions after the 1917 revolution will refer to Soviet art but exhibitions of art made before 1917 will usually say Russian art. In some cases, the distinction is one that is made by the curator or museum and does not always have a clear reference to a date. I try to conform to the terminology used in the exhibition.

14. Eleonory Gilburd, To See Paris and Die; The Soviet Lives of Western Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), see especially chapter 5, “Barbarians in the Temple of Art.”

15. K. Chunikhin, “At Home among Strangers; U.S. Artists, the Soviet Union, and the Myth of Rockwell Kent during the Cold War,” Journal of Cold War Studies, 21: 4 (Fall 2019), 175–207.

16. An unusual and very detailed article that focuses on the “infancy” of Russian artistic culture as an explanation for some disappointing art works was not based on an exhibition but written in anticipation of the forthcoming St. Louis exposition for a Chicago magazine that no longer exists: E. N. Keyser, “Russian Art: Its Strength and Its Weakness,” Brush and Pencil, 14: 3 (Jun 1904), 161–173.

17. David C. Fisher, “Exhibiting Russia at the Worlds’ Fairs, 1851–1900,” dissertation, Indiana University, 2003, 86–87. For a different approach to the role of World Fairs in establishing national identity, see Anthony Swift, “Russian National Identity at World Fairs, 1851–1900,” in Josephy Theodor Leerson and Eric Storm, eds., World Fairs and the Global Moulding of National Identities (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2022), 107–143. Swift’s focus is on Russia’s use of the Russian style, rather than industrial advances to create its brand.

18. Fisher, “Exhibiting Russia,” p. 70. In a table of Russian participation, Fisher notes 648 exhibitors in Philadelphia, 1048 in Chicago, and fewer than 400 in St. Louis where other complications intervened. His numbers, we will see, do appear to include all types of exhibitors. The undeniable value of this work is its usefulness as a guide to resources on and responses to the fairs. Unfortunately, Swift focuses only on European expos and does not discuss the American fairs.

19. One source for Russian participation in Chicago is Anna Zavyalova, “Russian Fine Arts Section at the World’s Columbian Exposition 1893, Notes on Organization and Reception,” Online Journal MDCCC 1800, 6: 9 (2017) 119–130. Other writers have addressed Russia’s involvement in European expositions, but I have chosen not to include those as my focus is the United States. In fact, the literature on non-American exhibitions of Russian art, especially those in Great Britain, is more extensive.

20. Zavyalova, 123. Her valuable research used archival materials in Moscow.

21. To determine whether or not this was a goal of the artists who sent works would require studying the complete bodies of work done by each artist and the provenance of each work. A worthy study but somewhat outside the boundaries of this one.

22. Although I have been able to track down a copy of the exposition catalog for Chicago, I have not had that luck with Philadelphia.

23. Spelling as listed in the Official Catalogue, Part X, Department K, Fine Arts, for the World Columbian Exposition of 1893 (available online through Google and through HathiTrust MARC); description on 364–365 with the artist’s name spelled Klagess and in an earlier listing as Klagis.

24. Hubert Howe Bancroft, the Book of the Fair (Chicago, IL: Bancroft, 1893), volume 8 as digitized by the Smithsonian, 754.

25. Bancroft, Fair, 758. Spelling of artist’s name as in the book.

26. Shaw, World’s Fair Notes, A Woman Journalist Views Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition (St. Paul, MN: Pogo Press Inc., 1992), 71.

27. Greenhalgh, Ephemeral vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851–1939 (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988).

28. Gustin, “Building Babel: The 1876 International Exhibition at the Philadelphia Centennial” Sequitur, 2: 1 (2015), quotation p. 2; Robert W. Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 1984), 21. Gustin and Rydell disagree on the unusual system of arranging the galleries in Philadelphia and the degree to which they can be called racist. Rydell does not discuss the Art buildings, while Gustin does not discuss the main building, making the extent of their disagreement unclear.

29. Robert C. Williams, “America’s Lost Russian Paintings and the 1904 St. Louis Exposition,” chapter 13 in Williams, Russian Art and American Money, 1900–1940 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980), 87–213, is the most complete discussion of this event that I have located.

30. “The National Note in Russian Art,” The Literary Digest, xxxii: 5 (Feb 3, 1906), 157–158; Brinton, “Russia through Russian Painting,” Appleton’s Booklovers’ Magazine, 7 (1906), 151–172.

31. Andrew J. Walker, “Critic, Curator, Collector: Christian Brinton and the Exhibition of National Modernism in America, 1910–1945,” doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1999, 34–35 refers to Brinton’s friendship with Grunwaldt and his article for Appleton’s. He does not spend much time on this article as it comes somewhat before the period of Brinton’s career that interests him but he does see it as contributing to Brinton’s theory of national modernism.

32. Brinton, Russian painting, p. 173.

33. Odom and Salmond, preface to Treasures into Tractors, xv–xix.

34. Olga D. Kamenova, “Cultural Rapprochement: The US.S.R. Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries,” Pacific Affairs 1: 5 (Oct 1928), 6–8.

Chapter 1 Sources

Altshuler, Bruce, ed., Salon to Biennial – Exhibitions that Made Art History. Vol. 1: 1863–1959. Vol 2: Biennials and beyond, 1962–2002. New York and London: Phaidon Press, 2008–13.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe, The Book of the Fair. Vol. 8. Chicago, IL: Bancroft, 1893. https://doi. org/10.5479/sil.780071.39088011387669

Barr, Jr., Alfred H., “Russian Diary,” October. Vol. 7 (Winter 1978), 10–51.

Blakesley, Rosalind P. and Susan E. Reid, eds., Introduction, Russian Art and the West. Dekalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2007, pp. 3–20.

Bowlt, John E., “Art in Exile: The Russian Avant-Garde and the Emigration,” Art Journal, 41: 3 (1981), 215–221.

Brinton, Christian, “Russia through Russian Painting,” Appleton’s Booklovers’ Magazine, 7 (1906), 151–172.

Chunikhin, Kiril, “At Home among Strangers; U.S. Artists, the Soviet Union, and the Myth of Rockwell Kent during the Cold War,” Journal of Cold War Studies, 21: 4 (Fall 2019), 175–207. Fisher, David C., “Exhibiting Russia at the Worlds’ Fairs, 1851–1900,” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 2003.

Flamm, Christoph, ed. et al., Russian Émigré Culture: Conservatism or Evolution? Newcastle on Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publisher, 2013; ProQuest Ebook Central.

Gilburd, Eleonory, To See Paris and Die; The Soviet Lives of Western Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Gray, Camilla, The Russian Experiment in Art 1863–1922 (revised and enlarged edition). London: Thames & Hudson, 1986.

Greenhalgh, Paul, Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851–1939. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988.

Introduction and Prelude

Kamenova, Olga D., “Cultural Rapprochement: The U.S.S.R. Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries,” Pacific Affairs, 1: 5 (Oct. 1928), 6–8.

Keyser, E. N., “Russian Art: Its Strength and Its Weakness,” Brush and Pencil, 14: 3 (June 1904), 161–173.

Makaryk, Irene R., April in Paris: Theatricality, Modernism, and Politics at the 1925 Art Deco Expo. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Odom, Anne and Wendy R. Salmond, eds., Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia’s Cultural Heritage, 1918–1938. Washington, DC: Hillwood Estate and Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009.

Rueschemeyer, Marilyn, Igor Golomstock and Janet Kennedy, “Soviet Emigré Artists: Life and Work in the USSR and the United States,” International Journal of Sociology, XV: 1–2 (1985).

Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Shaw, Marian, World’s Fair Notes, A Woman Journalist Views Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition. St. Paul, MN: Pogo Press Inc., 1992, p. 71.

Swift, Anthony, “Russian National Identity at World Fairs, 1851–1900,” In Josephy Theodor Leerson and Eric Storm, eds., World Fairs and the Global Moulding of National Identities. Leiden, Boston, MA: Brill, 2022, pp. 107–143.

Walker, Andrew J., “Critic, Curator, Collector: Christian Brinton and the Exhibition of National Modernism in America, 1910–1945,” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1999.

Williams, Robert C., Russian Art and American Money, 1900 – 1940. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Yezernitskaya, Mechella, “Christian Brinton: A Modernist Icon,” Baltic Worlds, XI: 1 (2018), 58–64.

Zavyalova, Anna, “Russian Fine Arts Section at the World’s Columbian Exposition 1893, Notes on Organization and Reception,” Online Journal MDCCC 1800, 6: 9 (2017), 119–130.

Reconsidering the 1920s

Chapter 1 took us to the beginning of the 20th century with its focus on three world expositions and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 which seemed to bring an end to exhibitions of Russian art until the 1920s. Although it is relatively easy to find reasons for an interruption in foreign exhibitions during the second decade of the 20th century, it was not a complete interruption.

Unlike the 1920s, the 1910s do not offer any major exhibitions of Russian visual arts although there is a one-year tour of the Ballets Russes in 1916.1 Opera singers, dancers and dance companies, and other forms of spectacle performances did not experience the same interruption that we find in exhibitions of the visual arts. The performing arts and the visual arts are rarely examined together making it difficult to compare the presence or absence of these events in terms that go beyond chronology and names. Yet, hypotheses regarding the “steady stream of Russian performers of ballet, vaudeville, and opera” point to such factors as impresarios and patrons, audience interests in novelty and exoticism, and the roles of company managers as playing important parts in the mostly continuous attraction and presence of these arts in the U.S.2 Nonetheless, the visual arts were here, not only in the form of émigré artists: gallery exhibitions of artists such as Nicholas Roerich, Boris Anisfeld, Natalia Goncharova, and others were held, often at the Kingore Gallery, the Knoedler, and others with greater or lesser longevity, and often traveling to galleries in Boston, Chicago, and other cities. Some of the early gallery shows were arranged by individuals who would later be putting together larger exhibitions, while in other cases, an artist’s association with a ballet or opera company may have led to the gallery’s interest in arranging an exhibition.

Whether the 1910s or the 1920s, we encounter the growing appeal of Russian artists as trend setters in fashion, and the degree to which early newspaper reviews adumbrated the inability to define and differentiate between styles of Russian art. In many cases, as we will see, this was not the fault of gallery owners, and even when it was, newspaper critics tended to group exhibitions and media together in articles indicating what people could see, hear, or watch at a certain time and certain place. These descriptive reviews were often more concerned with the owner of the objects for sale, what was available to be seen (or bought) than aesthetic evaluation. Just as the 1920s will bring some large and major exhibitions, reviews will also begin to focus more on style and differences between the emotional use of color and varied styles or emotions versus realism (Anisfeld or Goncharova, for example, versus Repin and, in some cases, the “curious realism” of Roerich3). Some reviewers searched for but could not always find a quality that could be called “Russian” rather than French, Anglo-Saxon, or Teutonic, and in other cases

Reconsidering the 1920s

(perhaps easier to do in performances than paintings, especially when realism was so widely admired), comparisons were made, generally unfavorably for painters, to the work of Russian theater where rehearsals and practice culminated in perfection.4 It will also become clear as we move later into the 1920s that definitions of the avant-garde were unstable. Before then, Brinton, rarely writing as a critic, was more specific about the qualities that made Anisfeld, for example, an exemplar of Russian or Slavonic art although he did not limit his praise to Anisfeld: “‘You will fail to grasp the significance of temporary [sic] Slavonic art in all its color and complexity,’ declares Dr. Brinton, ‘if you do not remember the fact that it constitutes, first and foremost, a protest against realism, a triumphant renaissance of the ideal – or to be more explicit, of decorative idealism.’”5 For other viewers, however, realism was the key to recognizing Russian art if it depicted stereotypically Russian settings.

That there are certain curators whose names recur in the larger exhibitions should not be a surprise. Yet, the interest of these several curators in Russian art does not arise for the same reasons. We find Christian Brinton and Katherine Dreier to be among the early leaders in planning exhibitions of Russian art, and although they worked together in more than one instance, they cannot be called collaborators. Brinton, in fact, may be seen to have collaborated with William Henry Fox, the director of the Brooklyn Museum, and in one case, all three worked together (the 1923 exhibition of Russian painting and sculpture). Dreier’s knowledge of Russian art never seems to be as thorough or committed as Brinton’s, given her goal of demonstrating that Paris was not the center of the art world and her belief that the Soviet Union should be thanked for creating a large émigré population of artists and thereby disseminating the “great spiritual contribution which Russia has to give.”6 Dreier was less likely than Brinton to work with specific museum directors as she planned to found her own museum of modern art. Despite their differences and the questionably phrased credit she gives to the Soviet Union, both Dreier and Brinton must be given credit for bringing Russian art to the attention of many Americans in the 1920s along with differing interpretations and judgments of this art. They each played a significant role in arranging gallery exhibitions, often at the Kingore, for such artists as Archipenko, Goncharova, Larionov, and others. A less familiar patron, Alice Garrett, made it possible for Leon Bakst to make two trips to the U.S. during which he had exhibitions in New York, Chicago, and Canada and gave lectures on fashion and design.7

In some respects, this history of exhibitions is also a history of competing interpretations of Russian art and of modernism, particularly between but not limited to Brinton and Dreier. We will see that the Dreier “school” is one which has a more personal, universalist, and theosophical interpretation at its heart; the Brinton “school” begins with a nationalist theory (called “racial” by Brinton) that evolves into a social theory. Louis Lozowick and Frederick Kiesler, both of whom are artists whose work shows an affinity with Russian constructivism, may be said in different ways to make this affinity important in their exhibition-related work, generally done with another curator; and Alfred Barr, whose exhibition ideology always seems to be more concerned with the evolution of his vision of modernism rather than an evolution of Russian art, initially contributes little to the development of exhibitions of Russian art despite growing a collection of Russian art for the Museum of Modern Art which he willingly loaned to others. Although Hilla von Rebay will later be denied sufficient credit for her role in creating the Guggenheim museum’s collection of abstract paintings – in particular the Kandinsky collection – and influencing the construction of the final building, despite her interest in Kandinsky and

Reconsidering the 1920s 17 other non-objective artists, she was not a dedicated collector of Russian art and cannot be seen to have played a strong part in the eventual development of the Guggenheim’s role in exhibiting Russian art.8 Exhibitions at the Guggenheim (before it was called that) rarely included enough examples of Russian art to be seen as Russian art exhibitions. By the end of the 20th century, the Guggenheim will have become a major force in mounting large Russian art exhibitions, an evolution that is not predictable from its origins as a museum of non-objective painting, as Rebay preferred to call it. Jane Heap, although better known as an editor and publisher, should be considered as yet another curator with an interest in the avant-garde and experimental art. Not a collector herself, her exhibitions did include Russian art and architecture, and her writing in the Little Review offers another perspective on the content and importance of the 1920s in this early phase of Russian art exhibitions. To be sure, we cannot overlook the gallery exhibitions that were frequently devoted to the work of one artist, sometimes through the efforts of Dreier and at other times Brinton: David Burliuk, for example, was promoted by both. Although he was widely known and wrote articles for magazines and newspapers about art and collected art, Brinton was never really a trained art critic. He promoted artists, especially the émigrés he met in NYC, making arrangements for them to exhibit their work. Not entirely altruistic, Brinton earned commissions for making these connections between artists and galleries. Anisfeld was one of the artists that Brinton helped, arranging an exhibition at what was the new Grant Kingore galleries (references to shows at this gallery begin to appear around 1920). He did the same for Roerich.9

Whereas Brinton and Dreier were important supporters of the emerging gallery scene in the 1920s, later in the 20th century artists themselves took the lead in forming artist-run galleries. Before that happened, however, galleries that may be little known today were taking shape. The New Gallery, for example, was founded in 1922, and although not dedicated to Russian art, it did show and sell the work of numerous Russians. Whether working alone or together, Dreier and Brinton fostered gallery shows of Burliuk, Anisfeld, Leon Bakst, Goncharova, Larionov, and others. Max Rabinoff, involved in the promotion of opera and ballet stars, worked with Brinton and Fox on Anisfeld’s first exhibition. The Kingore gallery was frequently used by Brinton to display the work of émigré artists. James N. Rosenberg, the author of the privately published booklet describing the New Gallery, was soon involved in many of the groups and associations that planned and installed exhibitions. As he wrote in the forward to New Pictures and the New Gallery, 1923, the goal of the gallery was captured precisely by the word “new” – the gallery was not claiming greatness or identifying styles in the works displayed but claiming only that the work was new. The list of artists, who had sold works through the gallery in its first year was international, included a variety of media and also included men and women. Neither Brinton nor Dreier was on the list of directors although they both supported the gallery.10 In her book about Burliuk, Dreier discussed the recent founding of the shortlived New Gallery at 600 Madison Avenue, using funds provided by members of the New Gallery art club (in most cases, previous exhibitors in the gallery).

1923: Brinton and the Brooklyn Museum

Both Brinton and Dreier have been the focus of much research, generally more familiar in the case of Dreier and her Société Anonyme, and less so in the case of Brinton, although there are dissertations that focus on his work. Despite his relative unfamiliarity, his role in the early years of this exhibition history cannot be downplayed. Brinton is an

Reconsidering the 1920s

enigmatic figure, not only as a collector of art but also as a writer and curator. His tastes were broad and not limited to Russia, and his earliest involvement in exhibitions goes back to the early 1910s and featured Scandinavian art. As Andrew J. Walker notes in his dissertation on Brinton, his engagement with art was so extensive and dominated his life in so many ways, it is difficult to fathom why so little reference is made to him in art historical literature. (Did he lack the entrepreneurial skills of someone like Sol Hurok, or was it his love for and focus on Russian art, just before and then after the Russian revolution?) As Robert C. Williams tells us, Brinton was a major promoter of Russian art, 11

connecting with Russian émigré artists almost as soon as they arrived in New York. In

addition to arranging exhibitions for Anisfeld and Roerich, before any group exhibitions of Russian artists were held, he connected with William Henry Fox, the director of the Brooklyn Museum, working with him on the Scandinavian art shows of the 1910s and the upcoming Russian art shows in the 1920s. Fox and Brinton may have met as early as the St. Louis Exposition where Fox served as the Secretary of the Fine Arts Department; both were involved with world’s fairs which is where the exhibition of Swedish art originated prior to moving it to the Brooklyn Museum. Fox become director of the Brooklyn Museum in 1914, a position he held until his retirement in late 1933 (announced in 1934). Curatorial collaboration with Brinton may have suited both Fox and Brinton as they shared a belief in the national identity of modernism, making the Swedish show a natural predecessor to the 1923 exhibition of Russian art.12 Brinton continued to work with Fox and the Brooklyn Museum while at the same time working with Dreier to arrange gallery exhibitions for Archipenko, Burliuk, and works of Suprematism, and planning for the 1924 exhibition at the Grand Central Palace (GCP).

Walker argues that Brinton was developing an alternative theory of modernism which is not based on international or universal aesthetic goals but on the extent to which contemporary art is shaped by and reflects specific social conditions and national or racial characteristics of the people living in those societies. Quoting Brinton, his theory is summarized by his belief that “there is no greater fallacy than the pretension that art should strive to be international or cosmopolitan.”13 We will see this belief dominating much of Brinton’s published writing from the 1920s and 1930s. Walker proposes that Brinton’s ideology was central to the dissolution of his working relationship with Katherine Dreier, who was committed to a universalist theory of modernism.14 This does seem likely, although it also seems probable that in both cases, their highly personalized views of modernism and their individual collecting directions would have made an extended collaboration impossible. If possible, such collaboration would have necessarily been complicated by the fact that the end of the 1920s witnessed the emergence of new museums dedicated to modern and contemporary art, marshaled by directors who had their own distinctive theories. Brinton continued to have strong ties to the Brooklyn Museum, to Philadelphia, and to the American Russian Institute (ARI), factors that may also have complicated the working relationship between him and Dreier. As John David Angeline observes in a dissertation on Dreier, her ideas about museums were unconventional and may have had more in common with house museums such as Hillwood and the Barnes Foundation, than with other museums of modern art. Here the crux of her difference with Brinton becomes clear. To Dreier, contemporary art is tied to a particular time period and does not change (although there would by necessity be a variety of contemporaries if this definition holds); modern art, in contrast, was always looking to the future and to “new cosmic forces.”15 If it stopped changing, it would be moved to a different museum. Given Brinton’s growing interest in nationalist theories of art, it