Acknowledgements

Most of the chapters in this volume were selected from contributions written for a conference on the Oberammergau Passion Play funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) as part of a larger project (2017–2022). After about a year and a half of project work, this conference was intended to place our studies on the Passion play and its village in a broader context – disciplinary, theoretically, and historically. Unfortunately, in times of a pandemic, the editing and completion of this volume took much longer than planned. Thus, first, we wish to thank all contributors for their patience.

The conference took place from 12 to 14 September 2018 at the Carl Friedrich von Siemens Stiftung, Nymphenburg Castle, Munich. We would like to thank our host, the Carl Friedrich von Siemens Stiftung, for its extraordinary hospitality, and especially Gudrun Kresnik who assisted us in all stages of planning.

In organizing the conference, we were supported by Katharina Schweigart. Anna-Dorit Lachmann and Laura Benetschik proofread the contributions, and Markus Kubesch helped with editing and formatting. It is our pleasure to thank all of them for their engagement.

Our special thanks go to the team of our DFG project, Céline Molter and Dominic Zerhoch, who also contributed to this volume, for their years of trustful cooperation.

Last but not least, we thank Laura Hussey and Swatti Hindwan at Routledge, who patiently awaited the manuscript.

4.1 Welcome to Oberammergau, Simplicissimus 26/53, 29 March 1922, extra issue: On to Oberammergau! (Auf nach Oberammergau! ), title page 54

5.1 Official poster to advertize the Passion play 1934 (Jupp Wiertz) 71

5.2 English version of the official poster for the Passion play 1934 73

5.3 Cover of the booklet by Business Management Catholic Tours Division for the Passion play 1934 80

5.4 Cover of the booklet by ARO Ackermann Travel Service Oberammergau for the Passion play 1934 83

5.5 Swastika flags and a banner express the community’s support for Hitler prior to the German referendum in 1934 86

5.6 “Entering Oberammergau”: Hitler visits the Passion play in August 1934 86

5.7 “Crucify him”. Mass scene to advertize the Passion play in 1934, official brochure 87

5.8 Hitler visiting the player s backstage at the Passion Play Theatre 87

6.1 The good shepherd: Jesus enter ing Jerusalem, Passion play, 2010 Oberammergau 94

6.2 Official advertisement of the Passion play in Oberammergau in 1934 96

6.3 Deutsche Passion 1933, Reichsfestspiele Heidelberg 1934, Schlosshof, Director: Hanns Niedecken-Gebhardt 99

6.4 Advertising the first Thing-Season in 1934: cover of the journal Die Spielgemeinde 101

6.5 Deutsche Passion 1933, Thingstätte Halle-Brandberge 1934, Director: Günther L. Barthel 103

8.1 Spielerwahl: waiting for the players’ names to be written on the chalk board 124

8.2 Children’s choir 137

8.3 Invitation to motto party on the election of Passion play performers 138

x Figures

9.1 Hair hunters: satirical response to the notorious fascination with the long-haired Passion players 153

9.2 The museum’s new dress: outer view of the Oberammergau Museum during the temporary exhibition (IM)MATERIELL, 2022

9.3 The hairy thread guiding the visitor s through the exhibition, (IM)MATERIELL show, Oberammergau Museum 2022

9.4 Double helix made of hair, (IM)MATERIELL show, Oberammergau Museum 2022

9.5 ‘We are connected’ – lettering in the penultimate room of the (IM)MATERIELL show, Oberammergau Museum 2022

9.6 Assemblage of photog raphs, hair, and other objects connected to the Passion, (IM)MATERIELL show, Oberammergau Museum 2022

9.7 Collage: hair on photograph, (IM)MATERIELL show, Oberammergau Museum 2022

155

156

157

159

159

160

12.1 Christ side saddle riding on the donkey 211

12.2 Magdalen, played by Bertha Wolf, at the Oberammergau Passion play, 1900 217

11.1 Literary Passion Play Scenarios, 1831–2022

Contributors

Evelyn Annuß is a theater and literature scholar serving as Professor of Gender Studies at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (mdw). She obtained her PhD from the University Erfurt (Elfriede Jelinek. Theater des Nachlebens, Fink 2007) and her habilitation from Ruhr University Bochum (Volksschule des Theaters. Nationalsozialistische Massenspiele, Fink 2019). Her research interests include cultural gender and performativity studies, (post-) colonial critique and the global history of performative cultures, theories of performativity as well as the relation of politics and aesthetics. Currently, she works on dragging from creolized carnival to Corona demonstrations. Upcoming publication: “Racisms and Representation. Staging Defacement in Germany Contextualized”, in Priscilla Layne/Lily Tonger-Erk (eds.): Staging Blackness, University of Michigan Press.

Mariano Barbato is Professor of Political Science at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Passau and DFG Heisenberg Fellow at the Center for Religion and Modernity, WWU Münster, Germany. He obtained his doctorate in political science, history and philosophy at the LMU Munich and his habilitation in political science at the University of Passau. He published widely on religion and politics and is currently the principal investigator of the DFG-funded project “Legions of the Pope. A Case Study in Social and Political Transformation”.

Toni Bernhart is a researcher in Modern German Literature at the University of Stuttgart. His research focuses on folk and popular theater, history of digital humanities, and aurality and literature. His recent publications include Volksschauspiele. Genese einer kulturgeschichtlichen Formation, Berlin, Boston 2019; (with Sandra Richter) Frühe digitale Poesie. Christopher Strachey und Theo Lutz, Informatik Spektrum 44 (2021): 11–18; (with Julia Koch) Blowing ‘The Boy’s Magic Horn’. Popularised and Synthesised Romanticism, AnneSophie Bories, Petr Plecháč, Mari Sarv (eds.): Popular Voices (forthcoming).

Martin Leutzsch held the Chair of Biblical Exegesis and Theology in Protestant Theology at the University of Paderborn from 1998 until his retirement

Contributors xiii in 2022. He is a New Testament scholar and author of numerous publications on social-historical questions of biblical cultures, on the ecclesiology of ancient Christianity, on the reception history of the Bible, and on the theory and practice of Bible translation.

Jan Mohr is Assistant Professor of Medieval German Literature at the Department of Language and Literature Studies, LMU Munich, and currently serving as Deputy Professor at the University of Bielefeld. With Julia Stenzel, he led the DFG-funded project “The village of Christ. Institutionaltheoretical and functional historical perspectives on Oberammergau and its Passion play, 19th–21st centuries” (2017–2022). Jan obtained his PhD in Modern German Literature and wrote his habilitation on Middle High German Minnesang. In addition to the Oberammergau Passion play, his research interests include courtly epic poetry, namely Arthurian romance, historical narratology, and devotional practices in the early modern period.

Céline Molter is Research Assistant at the Institute for Anthropology and African Studies at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. She is working on her PhD on the Oberammergau Passion play in the global context of Christian theming as a member of the DFG research project “The village of Christ. Institutional-theoretical and functional historical perspectives on Oberammergau and its Passion play, 19th–21st centuries” (2017–2022). She is also a member of the DFG network “Key Concepts in Theme Park Studies”, writing about religion and worldviews in theme parks. Her research interests focus on the anthropology of religion, tourism, and theming.

Robert D. Priest is Senior Lecturer in Modern European History at Royal Holloway, University of London, UK. He is the author of various works on nineteenth-century cultural and intellectual history, with a particular interest in religion and secularization. His first book, The Gospel According to Renan, explored the popular reception of religious criticism in nineteenthcentury France through the lens of the readers of the controversial Life of Jesus that Ernest Renan published in 1863. He is currently writing a book for Oxford University Press on the transnational history of the Oberammergau Passion play from the Enlightenment until the interwar period.

Julia Stenzel is a Junior Professor of Theatre Studies at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. She deputized as a Professor of Theatre Studies at LMU Munich (2021/2022) and of Religion Studies at the Forum International Research (FIW, Bonn University) in 2019. With Jan Mohr, she led the DFGfunded project “The village of Christ. Institutional-theoretical and functional historical perspectives on Oberammergau and its Passion play, 19th–21st centuries” (2017–2022). Julia works on theater and media history, theater theory, and theater and society. Her current research focuses on theater of/in Iran, theater and religion, transformations of ancient theater, and scenographies of demagoguery.

xiv Contributors

Dominic Zerhoch is a researcher at the DFG-funded project “The village of Christ. Institutional-theoretical and functional historical perspectives on Oberammergau and its Passion play, 19th–21st centuries” (2017–2022) and is currently working on his PhD at the Institute of Film, Theater, Media and Culture Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. He worked as director and assistant director. He co-founded the international and interdisciplinary PhD-Network DIS(S)-CONNECT focusing on media research. His research interests include Oberammergau and its Passion play, corporality and theories of embodiment, methodology of theater historiography, spatial theory and scenography.

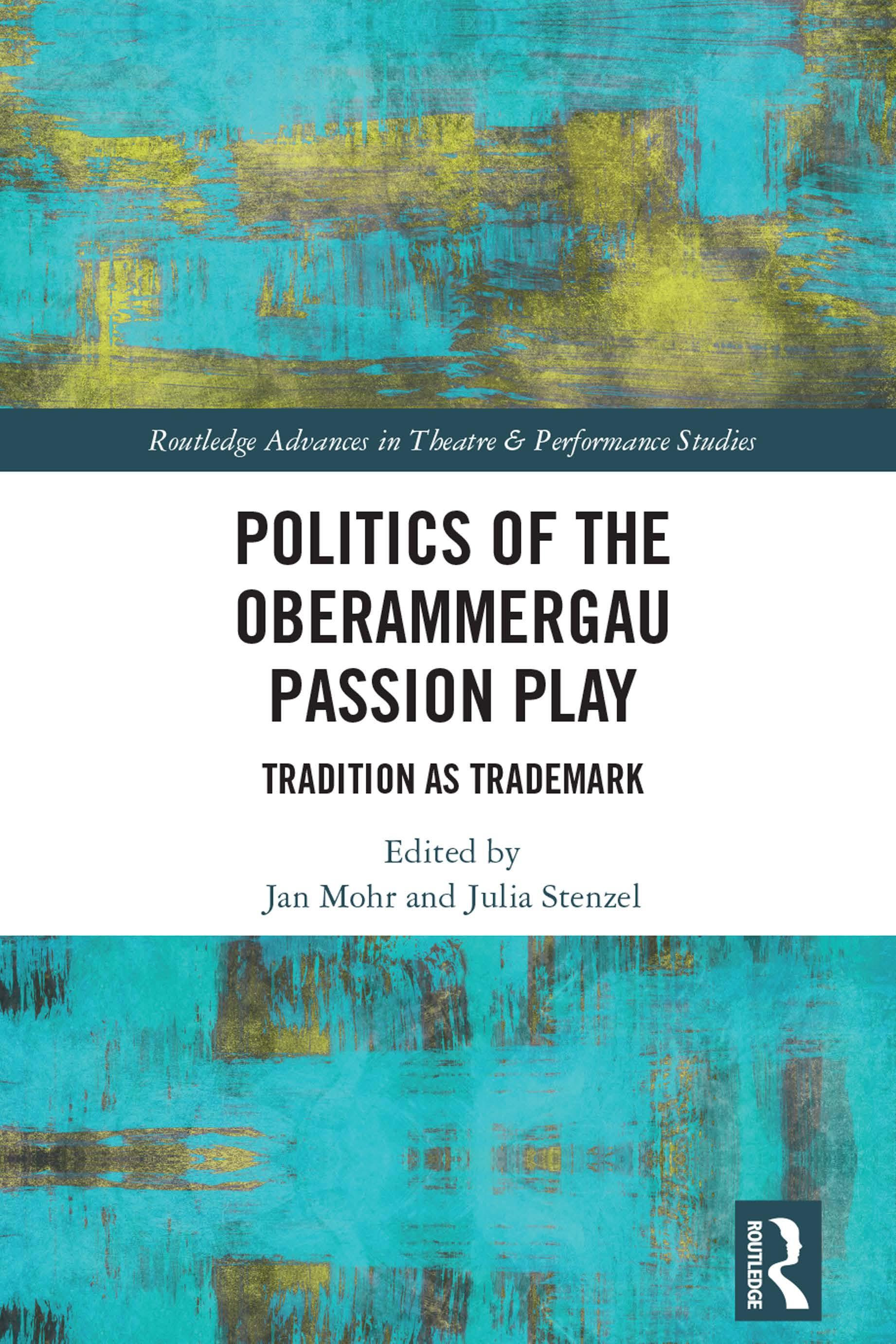

1 How to Become a Trademark

An Introduction

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

1. “Anticipation!”

Vorfreude – anticipation! Thousands of merchandise bags intended for the Oberammergau Passion play season 2020 have to be reprinted. The closing “0” is crossed out and replaced by a “2”, and the print is complemented by a handstamped “Vorfreude”, or “g’sund bleiben, g’sund werden” – “stay healthy, get healthy” (local pharmacies sell these last ones). Anticipation is half the pleasure, it is said. However, the other half is postponed to an uncertain day after tomorrow. The grammatical tense of the worldwide COVID-19 crisis seems to be the future II: When Corona will be over, people will enter shops, theatres, and museums without masks, universities will completely reopen, and the Passion play will take place without any restrictions. Although it is far from sure that there is an “after Corona” that allows for a “back to normal”, the futurologist view is complemented by a very different engagement with society’s challenges. In March and early April 2020, as the pandemic caused by a novel Coronavirus accelerated, it felt like dancing around an empty centre: Day after day, we were told about festivals, exhibitions, sports events, conferences, and theatre performances that should have taken place but did not. Instead, theatres were streaming past legendary productions. Despite things changing since the first pandemic months, the grammatical tense of pandemics is not only the future. It is also the past irrealis.

The 42nd season of the Oberammergau Passion play should have started on May 16, 2020. Moreover, when news of a highly contagious and potentially deadly virus made its rounds in early February of that year, we, as presumably all too many people worldwide, did not consider this might concern us, let alone the playing season. However, things already looked different four weeks later. In mid-March, the virus, which by then had taken the dimensions of a pandemic, thwarted the Passion play schedule drastically. After the Corona case numbers rose significantly in the Bavarian Oberland and neighbouring communities reported the first cases, the Passion 2020 was postponed by two years. One could see director Christian Stückl struggle to hold back the tears when announcing this at a press conference on March 19. Later, one could hear that the Passion play directory had doubted relatively long only to wait

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

for instructions of the district administration, which would disburden the village community from any claims of compensation after postponing the playing season. And wisely did they delay it by two years, as we can see by now.

In March 2019, a kind of interlude began in Oberammergau, the start of which was not only determined by the reversal of thousands of already purchased tickets and packages but also by an aestheticization of latency. The remains of the play that never took place were modified and brought to life beyond theatre situation: the costumes that were not worn, the fabrics that were not used become merchandise items, such as key rings, on which the double reference to the cancelled and the new season is partly inscribed, partly not. Online shoppers are invited to equip themselves with relics of a Passion play season that never took place, such as shirts and backpacks. If there is one, even the act of redesigning and repurposing is staged. The press office publishes short video clips on social media showing people reworking the aforementioned canvas bags, adding the handwritten-looking stamp print: “Anticipation!”

As is well known, the playing tradition in Oberammergau goes back almost 400 years. When the plague ravaged the Bavarian Oberland in 1633, the village, well shielded by mountain ranges, was able to keep it at a distance for a long time. But finally, a labourer, who wanted to return home to his family, crossed the mountains on hidden paths and managed to overcome the barriers, and in no time, the disease spread through the village. According to tradition, more than 80 people had died when the community elders gathered to make the famous oath: If God spared the town from the plague, they would perform the play of the life and death of our Saviour every ten years. Since 1634, the play has been performed regularly in Oberammergau, with only two cancellations (in 1770, when driven by Enlightenment thoughts, the Bavarian government tried to stop all superstitious traditions, and in 1940 during World War II) and few postponements.

During this long period, the cultural parameters in which the play was situated shifted considerably. The Passion play stands in the tradition of Catholic religious drama and sacred representations, which flourished especially in the late Middle Ages. In the 17th century, dozens of such local play traditions existed in the Alpine region and all over Europe. However, hardly any of them can show continuity up to the present day, and among the few, Oberammergau is unrivalled in fame. Not only has the text of the play changed, but of the oldest surviving text (1662), only the basic framework is preserved, which is ultimately already derived from the Gospel accounts. Fundamental revisions took place in the middle of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century. Finally, in two attempts in 1850 and 1860, the historicist form was created to be the textual basis for another 100 years. Since 1990, stage director Christian Stückl and his team have worked consistently to purge the text of anti-Semitic tendencies and recall the political and social background of biblical events.

The stage design has changed significantly over the decennials, but the theatre house would also be rebuilt several times. Whilst the plays were first performed in the cemetery directly in front of the village church, in 1830, a

Become a Trademark 3

new stage was constructed at the Northern edge, followed by new and everlarger stage buildings in 1890, 1900, and 1930. This was also necessary. Since 1850, one has become aware of the play in German countries and beyond. Since Thomas Cook set up a temporary office in Oberammergau in 1879, the play has been well-developed for mass tourism. In 1880, the British ethnographer and explorer Richard Burton could book the trip with his wife conveniently from England, and as early as 1871, a travelogue published in an American magazine reported that the journey was of a “fatal facility” (Conway 1871: 618).

The community also consistently geared its media self-presentation to an international audience. In the late 19th century, short series of periodicals were printed for the seasons to inform international audiences about the Passion play, the village and its environs; the Oberammergauer Fremdenführer in 1880 (Hännssler 1880) and the Oberammergauer Blätter in 1890 (Calwer 1890), the latter trilingual (English, German, French). The promotional tours of recent times have their prominent antecedent in the trip that the Jesus actor Anton Lang made to the United States in 1923/1924 to promote a peaceful, liberal, and hospitable host country – and not least to merchandise the local woodcarvers’ products to help his village to cope with the inflation in the aftermath of the World War (on Lang’s journey, Spear 2011; Molter 2022). In recent seasons, trailers have been shot to break up the traditional ban on filming; the Passion play homepage has grown several times over in recent years and now offers visual material that only a few years ago one had to search for in the Oberammergau municipal archive. Moreover, significantly since the lockdown in early 2020, the activities on social media have grown once again. The Passion play moves with the times, and it always has – in the play texts, in costuming, self-presentation, and self-marketing. The Oberammergau Passion play stands in a tension between tradition and innovation that has often been mentioned. However, things allow for a more specific perspective on this context.

2. Trademark

In the expression “Tradition as Trade Mark”, we combine two terms, each of which is suitable for itself to meet the tension we claim to be characteristic of the Oberammergau Passion play. In “Tradition”, the connection between the centuries-long continuity of the play and the constant redesigning and updating is addressed. Thus, change paradoxically contributes first and foremost to ensuring and stabilizing continuity. The metaphor “trademark” hints at aspects of recognition, meeting expectations, and reliability, but also quality standards that can assume the character of unique selling points. The economic and legal contexts in “trademark” are not unfounded either: the self-description of the Oberammergau Passion play as a genuinely non-economical affair generates an economically effective and globally successful “trademark” on the one hand and makes strategic marketing for self-preservation necessary on the other. Historically, the reference is appropriate insofar as the later 19th century

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

also witnessed the development of brand awareness and trademarks (Errichiello 2017: 22–33) – precisely the period in which the Passion play came to the attention of an international audience and was opened up for visitors from abroad in terms of tourism, marketing strategy, and media.

Trademarks promise more than the merely economic exchange of goods for money. The exchange is semantically charged, and different aspects can complement and support each other. Trademarks promise either sheer quality (compared to competing products) or an attitude to life that can supposedly only be achieved with this brand, but at the same time, they claim that such an impression has a foundation in the product itself. A trademark promises, paradoxically, defined production standards that ensure high quality, but simultaneously, a uniqueness; trademark products are singularities that stand out from the mass of similar products (on the sociological concept of singularities, see Mariano Barbato’s contribution in this volume). Thus, trademarks create affective and emotional bonds between product and buyer. In this way, they establish continuities in a flexible capitalist market, even if they are continuously developed further – or combined with other brands.

Like all outstanding products, trademarks seek each other out as they support and authorize each other. When the British icon James Bond drives a particular car brand, this is more than just one-way product placement, and the result of such cross-promotion is more than merely an economic factor. When a crime novel from the year 2000 interweaves a murder in Oberammergau with the Israeli Mossad, the city of New York, and the “mad” Bavarian King Ludwig II into one story, associations with the picturesque sceneries of the fairy-tale king and the Passion Village are expanded at the same time. Oberammergau moves up into a league with must-see places in the world (see Mohr: Myth). On all levels, such and similar figures of justifications, evocations, and semantic accretions can be observed around Oberammergau and its Passion play, as several contributions trace (see Annuß, Bernhart, Molter, Stenzel: What Kind of Man, Zerhoch).

A final thought on trademarks leads to the theoretical background underlying the conception of this book. Trademarks often have or are identified with a pictorial sign that makes them recognizable at a glance; a distinctive shape, a lettering, a logo, a colour combination, or even an acoustic sign (one recognizes Ennio Morricone’s film score in seconds). All imputed qualities and exceptional characteristics are condensed in this iconic tangibility and become associable for the consumer. Trademarks can be conceived as moments of institutionality.

3. Practicing and materializing social order: institutional theory

There are numerous notions of institution and institutionalization (at a glance, Esser 2005; Scott 2001). Even within sociology, the concept has a history of over a hundred years, ever since Émile Durkheim placed institutions at the

How to Become a Trademark 5

centre of sociological analysis (Durkheim 2013 [1895]). Since then, sociology has undergone various internal differentiations, and most have furthered the diversification of “institution” as a concept. Moreover, the number of works that presuppose a concept of “institution” but do not disclose it is almost incalculable. Nevertheless, the various approaches have in common that they distinguish between institutions and any pragmatic frameworks that might be labelled “organization”; thus, they deviate from everyday semantics. “Institution” does not mean “authority”, “office”, or “corporation”, but complexes of rules, roles, and scripts of conventionalized action patterns (Scott 2001: 57–8). Current institution theories emphasize an action-regulating power of institutions: Institutions offer orientation, establish expectations, and counteract behavioural uncertainties.

More specifically, in recent sociological theory, “institutionality” has been regarded as a moment in which the normative foundations of social orders become perceptible. In historical research, this view on institutions has proved to be particularly useful, among other things, where social orders have been examined in historical change (Melville 1992; Rehberg 1994; Melville 2001; Melville and Vorländer 2002; Melville and Rehberg 2012). In this perspective, it goes beyond the established practices and processes that allow an organization to work smoothly and efficiently. Social structures maintain stability not only by functioning successfully but also by making their meaningfulness tangible. According to this notion, specific institutional stability of social structures exists when an abstract order is (re)presented in embodiments or sign systems so that concepts of meaning and value standards can be experienced. We assume that such institutional moments can be observed in all organizational constellations, making their normative foundations “symbolically” perceptible (cf. Rehberg 2001, esp. 21–35): “What is institutional about an order is the symbolic representation of its principles and claims to validity” (Melville 1997: 16). The institutional pre-structures action and communication processes; simultaneously, “the assertion of the intrinsic value and the intrinsic dignity of an arrangement of order is increased and enforceable” (Rehberg 1994: 56). According to this notion, institutional mechanisms can be analysed in symbols in which the norms and values presupposed in the background come to the fore (Rehberg 2012: 425). First and foremost, institutionality implies the collective claim and performative affirmation of proper times (Eigenzeit; cf. Rehberg 2012: 433–7) and spaces (Eigenraum; cf. Rehberg 2001: 39–43).

This concept of institutionality is highly applicable to the case of Oberammergau as the “village of the Passion”. It just takes a short town walk and a certain amount of awareness to see how the entire village relates to the Passion play and its history. The names of Passion playwrights, stage composers, biblical characters, and their impersonators in historical playing seasons appear on street signs, walls of buildings are painted with biblical scenes and historical architecture, the Passionsspielhaus, which is, topographically, located at the margins of the village marks the topological centre of Oberammergau. So it seems that the village’s spatial logic develops from the Passion play, as the village seems to tell

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

its history in parallel with the history of the Passion. However, Oberammergau is not only chrono-topologically entangled with the Passion play; the decennial rhythm of play seasons and latency periods entangles individual biographies and family histories. Social time in Oberammergau is structured by specific cycles, from the decennial performances to the ushering of each season with the ritual announcement to the actors to have their hair and beards grown (Haar- und Barterlass). The growing hair changes the image in the village, thus indicating not only the state of exception but also that this state extends into the time between the Passion years, making everyday life qualifiable as a latency period. It also makes different gradations and variances of belonging visible at a glance: those who do not appear on stage may wear their hair as they wish.

The recent postponement due to COVID-19 may illustrate how the need to cope with latency periods contributes to the specific processes of institutionalization that characterize Oberammergau as the village of the Passion play. Not least in the last two years, this perspective has become apparent. It is not without a sense of irony that the play lauded for the ravaging plague had now to be postponed because of a viral pandemic. However, even in this unforeseen circumstance lies the potential to build on its tradition. The postponed season coincides with the 100th anniversary of another postponement from 1920 to 1922 after WWI. Due to casualties in the war – too many male villagers had fallen; the play directory faced a shortage of performers and orchestra players. It is only since 2020 that an epidemiological reason has also been given for the postponement one hundred years earlier: The Spanish Flu, which ravaged Europe from 1918 to 1920 and claimed many lives, especially among 20–40 year olds.

Institutionality becomes particularly visible when the institution it presupposes is called into question and comes into crisis. It is enacted and acted out when it includes the crisis – ex-post – in its own logic and derives it from its own history: Figures of institutionality always generate new significances and self-justifications, for example, as COVID starts to threaten the 2020 Passion play. However, the two-year delay of the 1920 season had been explained with reference to WWI ever since the 1920 and 2020 postponements now become explicitly paralleled. Nowadays, this postponement is contextualized with the Spanish flu. Whether this recent explanation can be proven or not, the time it comes into play is overtly significant.

It is paradigmatic for how Oberammergau continues to narrate itself by claiming both the repetitive character and singularity of its tradition: Thus, the contingency of the pandemic-driven postponement is now narrated as a common thread of the Passion play tradition. By integrating it into the narrative and material practices that help institutionalize Oberammergau as the unique “Town of the Passion”, the latency of two years is transformed into the chrono-logic of Oberammergau as the implied institution. It is precisely in its ability to bridge non-playing years and cancellations that the singularity of the Oberammergau Vow play lies: As early as 1920, a pandemic played a role in the decision to postpone to 1922 – thus, the recent delay can be reformulated

as the establishment of another cyclical structure, reenacting the founding history of the playing tradition. The entanglement of the Passion play with the individual passions of the villagers, the visitors, and the world, spiritual healing and the illnesses of humanity is actualized again. Thus, the specific aesthetics of Oberammergau’s institutionality emerges as the appearance of configurations of sense and their constant transformation.

This also applies to how individual biographies – overtly fictional as well as historical narratives by visitors as well as villagers – converge with the chronotopology of the Passion play: Although the decennial production of the Passion of the Christ continues to be perceived and conceived as a charismatic, even more as a singular event, the obedience to the plague vows is less dispensable as an individual confession of each spectator. The play remains meaningful, but the history of salvation becomes more and more open to individual or collective reformulation, transformation, and re-application.

4. Religion and secularity

“What isn’t Religion?” Kevin Schilbrack makes this polemic question the title of a considerable article that tackles the challenges that emerge with the postcolonial and critical occidentalist approaches that have been characterizing the study of religion at least since the middle of the 20th century. Schilbrack names the theoretical and methodical dilemma of contemporary religion studies that aim to establish “religion” as a concept open to non-monotheistic, non-European practices and epistemologies. Instead of supporting the deconstruction of the very category of “religion” as proposed, for example, by McCutcheon (McCutcheon 1997), he tries to evaluate the analytical and descriptive options that emerged with religion as a field of study different from the theologies. To balance the rather sociological assumption of religion as a field of social practice with semiological and experientialist or phenomenological approaches, Schilbrack conceives religion as a social practice involving the participant’s belief that this practice engages a community of believers as well as superempirical entities, beings, or logics, that is transcendence (Schilbrack 2013). As Schilbrack and others argue, religion manifests itself in practices and processes of mediation (Meyer 2020), for the encounter with the superempirical, the holy, the gods, ghosts, or inner self implies the bridging of a gap, the handling of a metaxy, the channelling of divine energy, or the emergence of a former invisible “beyond”. Against the background of this conceptual scaffold, the specificity of the Catholic Passion play tradition manifests as a medial configuration that allows for the encounter with the numinous in a human body embodying the Son of God. The audacious claim underlying the theatrical re-enactment of the Passion – “look at me, I am Jesus Christ” – presupposes a media practice characteristic of Catholic Christianity. Through the words of the eucharist, spoken in the liturgy by the priest, Jesus is not only represented in the bread and wine but is actually present. This fundamental assumption of the Catholic concept of God makes a conceptualization of the Passion play as “more-than-theatre”

8 Jan Mohr and Julia

Stenzel

plausible in the first place: as the bread and wine, the actor’s body on stage can also be experienced as more than an arbitrary embodiment of Jesus. The claim that the histrionic Jesus speaks and acts with divine charisma for the duration of the Passion play underpins numerous travelogues and fictional narratives since the middle of the 19th century, as the Passion play begins to attract audiences from all over Germany, Europe, and the world.

At first glance, it seems irritating that the international career of the Oberammergau Passion play starts in a historical situation conventionally associated with the macro-historical process of secularization, conventionally understood as the separation of state and church, individualization of belief and religious practice, a decrease of religious traditions entangled in societal and political institutionalization. Actually, only six years after the duchy (Herzogtum) Bayern became a kingdom (Königreich Baiern), a far-reaching expropriation of the church (Säkularisation) in the early 19th century profoundly influenced the social and public spheres and the cultural life of its inhabitants.

Trying to observe and evaluate this irritation, its implicit presumptions come into sight, and it can be shown that the popular micro-history of the Passion play, declaring Oberammergau as one of the last residuals of pre-modern religious theatricality in Europe, is deeply indebted to the meanwhile notorious concept of secularization as established by Émile Durckheim. Durkheim’s secularization thesis (Säkularisierungsthese) describes the modern evolution of the state and the church as separate institutions, fueled by the enlightenment and nearly completed in the 20th century. In Durckheim’s sense, secularization suggests a historical process of demystification and disenchantment (Entzauberung der Welt), profoundly transforming European societies. In the process of secularization, transcendental foundations of “man” and “world” are substituted by narratives of rationality and efficiency; in this perspective, modernity and secularity are co-evolving and intertwined. In the modernization process, secular and religious domains are separated, and the state emancipates itself from the church’s power, structurally and institutionally.

When “secularization” is understood as a notion implying disenchantment, the disappearance of transcendence, or profanation, the different conceptual pairings deriving from this notion meet in one aspect: The history of secularization can only be told in terms of either emancipation or loss. However, such a narrative tends to invisibilize that processes of rationalization/modernization and religious vitalization or revitalization are not mutually exclusive. Accordingly, the concept of secularity has repeatedly been criticized, albeit rather cursory (Arnal and McCutcheon 2013: xv). Thus, it has been argued with good reason that religion has not lost its significance in Western Europe but only transformed. However, a secularization thesis that focuses on the historical sequence of a non-secular pre-modernity and secular modernity cannot adequately comprehend individualized, syncretic, non-institutionalized forms of religiosity. As with “religion”, “secularity” should also be spoken of in plural (Führding 2015). Accordingly, as a historiographical concept, secularization

also implies no dichotomous opposition between religion and the profane or the secular. It rather presumes manifold differentiations and internal differentiation of social fields. Thus, the increasing international success of the Passion play since the middle of the 19th century is far from surprising. Moreover, its success is related to the fact that it occupies a specific niche of cultural practice in which it does not serve as a surrogate for religious contexts of practices but instead provides meaning precisely in its specific blending of “the spiritual” and “the profane”.

Instead of the challenged notion of secularization as the replacement and emancipation of secular spheres from religious institutions and norms, we apply a model of multiple secularities as proposed by Wohlrab-Sahr and Burchardt (2017) and Wohlrab-Sahr and Kleine (2021) to tackle the relation of religion and other societal fields. Departing from Shmuel Eisenstadt’s more established model of multiple modernities (Eisenstadt 2000), Wohlrab-Sahr and Burchardt differentiate between secularism as a bundle of ideological presumptions and embodied practices connected to epistemological colonialism and occidentalist hegemony and secularity as a sociological concept: While secularism stands for an ideology of separation (religion vs state, privacy of faith vs secular public sphere), secularity as a concept, in contrast, allows for describing the diverse forms of differentiation and entanglement between religion and other societal fields of practice. Moreover, unlike “secularism” and even “secularity in singular”, the concept of multiple secularities does not imply a unilateral or teleological process of modernization that makes religious practice disappear from the public sphere. Instead, it aims at establishing a typology open for historical and cultural comparatistics and not restricted to Western modernity (Wohlrab-Sahr and Burchard 2011: 71). Thus, applying this model implies material and discoursive histories as well as questions of institutionality and institutional aesthetics.

Thus, the history of the Oberammergau Passion play is not at all opposing macro-historical evolutions. Instead, its survival and transformation in the “long” 19th century can be seen as symptomatic of the multiplication and diversification of religion and secularity. In Oberammergau’s history over the last 200 years, the detachment of previously religious practices from their underlying cultural frameworks becomes observable. For example, out-oftown visitors still refer to the journey to the Passion play venue as a pilgrimage. The pilgrimage narrative, however, is overlaid with the practices and semantics of tourism; in addition to deeply religious people, those seeking recreation and those interested in culture also travel to Oberammergau, and accordingly, advertising prospects try to address these different segments of guests (cf. Zerhoch, Mohr: Pilgrims and Tourists). The vow play no longer finds its ultimate justification in a vertical axis, towards God, but in a horizontal one, when the community is considered the ultimate inescapable value. It is no longer transcendentally justified but immanently when tradition is considered the ultimate value. When the main actors engage in their characters, the embodiment of the sacred figures connects with personal life experiences and is thus subject to

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

new forms of authentication – the religious and the worldly (the secular, the profane) condition and contour each other.

Oberammergau is associated with narratives, stories, perceptions, and patterns of action that have solidified on the one hand over the last 200 years and, on the other hand, have become further differentiated. With them, the Passion play village occupies a position in a field determined by multi-layered intersections of religious, spiritualistic, touristic, cultural-critical, and ethnological interests, in which the villagers and the out-of-town visitors partly meet and partly stand out decidedly from each other. As this mélange is specific and probably unique, it seems justified to address the phenomenon of Oberammergau as a trademark.

5. On the parts and chapters

How to become a trademark? The first part proposes a typological and a historical answer about Oberammergau. Based on German sociologist Andreas Reckwitz’s singularity model, Mariano Barbato (Politology, Passau) contrasts Oberammergau with the (current) papacy. From this perspective, both institutions consistently work on validating the plausibility of their uniqueness. Furthermore, Barbato outlines that both had a pronounced constancy – which also means that they were successful in their aspirations – and works out structural parallels and differences in the respective possibilities and strategies of a self-removal.

Complementarily, Robert D. Priest (History, London) reconstructs the manifold and changing alliances that could be formed in the debate about the Passion play and its performance from a historical perspective. Based on thorough archival work, Priest analyses in two synchronous cuts (1860, 1890) the social and institutional tensions that characterized the Oberammergau Passion play in the 19th century – among the citizens as well as between parish, church, the various legal institutes, the (Free) State of Bavaria, and the Bavarian king. In 1860, the text produced by Alois Daisenberger 1850 was revised once again to make a profound impression on foreign visitors. In 1890, the Gospel tradition and the ecclesiastical-theological position opposed the local traditions in Oberammergau and the Daisenberger version of the text. Again, the village could assert itself against demands for a revision. The village community’s consistent reference to its tradition is interpreted as a strategy to preserve autonomy in dealing with its passion play – a perspective that, as the following chapters show, could easily be extended to developments in the 20th and 21st centuries.

In Part II, we focus on the emergence of a theatrical public sphere (Balme 2014), in which the institution of Oberammergau is approved and stabilized. A considerable part of this public sphere is formed by travellers – which means that it is constituted in the process of the travels itself. Secondly, through the theatrical and dramaturgical peculiarities of the play, the audience is formed into a community; nothing shows this more clearly than the attempts of Nazi propaganda to adopt the formal characteristics of the Passion play for its own

How to Become a Trademark 11 forms of theatre-based mass direction. Finally, scholarly discourse also contributes to stabilizing collective notions of Oberammergau – whether the underlying criteria are justified or not.

Jan Mohr (Medieval German Literature, Munich/Bielefeld) analyses travelogues to Oberammergau in magazines, travel reports, and memoirs. He traces narrators’ rhetorical and narrative strategies to make their journeys sound more like pilgrimages and set themselves apart from the set of “others” looked down upon as mere tourists. Dominic Zerhoch (Theatre Studies, Mainz) follows that line up to the 20th century and provides a theatrical perspective on this historical period. Based on archival research, he examines the spatial representation of Oberammergau in travel brochures of the 1934 Passion play. In an extended scenographic perspective, he shows how textual and pictorial strategies ascribed specific characteristics to the already hybrid space, thus evoking ideas (“geocodes“) and generating expectations even before the physical appropriation of space. The hybridization of the Oberammergau scenography allowed various actors to characterize Oberammergau as a Catholic place of pilgrimage but also as the destination of an alpine adventure holiday and to instrumentalize it for propagandistic purposes, thus addressing heterogeneous target groups.

Evelyn Annuß (Gender and Performance Studies, Vienna) traces the afterlife of the Passion play in the form of Nazi Thing plays (Thingspiele) in the early 1930s. In the structure of a pastoral dramaturgy, the planners of the Thingspiele perceived impulses for their concept of unifying the audience in a homogenous mass that could be ideologically governed and controlled. Just as the Passion play at least suggests the abolition of a boundary between players and spectators, the Thingspiele aimed at performative inclusion. The fact that drinking, smoking, and applause were explicitly undesirable – albeit not to be suppressed –was intended to steer the perception away from individual needs and towards the depicted homogenized mass in which a popular body (Volkskörper) was pre-figured. The concept of the Thingspiele ultimately failed after a short time while radio as a new and more effective mass medium entered the stage. Nevertheless, during the consolidation phase of Nazi power, substantial functional loans could be made to the Oberammergau Passion play before the cinema was largely established as the new leading medium of Nazi propaganda from 1936 onwards.

Based on the Oberammergau Passion play, Toni Bernhart (German Literature, Stuttgart) discusses and deconstructs the term Volksschauspiel (community play), common in cultural studies. Intuitively, the term is likely associated with collective production and/or reception modes. However, it has never been systematically and descriptively clarified. By the Oberammergau Passion, often seen as the paradigmatic folk play, Bernhart shows that the concept, suffering from its ideological prehistory in the 18th and 19th centuries, has never been clarified in German Studies. The chapter also points out the discrepancy between scholarly categorizations that are backgrounded by assumptions of structural literacy and prevailing oral traditions. In tracing the term folk play (Volksschauspiel ) and examining its development and application in German

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

Literature and Cultural Studies, the attribution of “old” becomes crucial. Conceived in the sense of “pre-historic” or “pre-historiographical” (which is, evading historiographical determination of origin), the attribute of age, which has advanced to become an essential characteristic and unique selling point of the Oberammergau Passion tradition, can serve different expectations and is open to different cultural-historical modellings.

In Part III, we tackle how the authenticity of Oberammergau and its Passion play is produced and perceived on stage and in medial responses to on- and offstage presentations of the Passion play. Finally, we ask how the Passion play practices both forms and is formed by the self-fashioning of the social image and political community.

Céline Molter (Ethnology, Munich/Mainz) analyzes the casting of actors for the Passion play 2020, which took place in the summer of 2018. Using the example of the media reception of the Oberammergau Wilhelm Tell production of 2018, she describes the multi-layered production of space and meaning in the Passion play Theatre in the run-up to the coming Passion play season and showed how the preparation for an actor’s choice for Passion play took place as an interplay of on- and offstage discourses. The tendencies that became clear during the Wilhelm Tell performances have been confirmed later, as the players cast for prominent roles would also occupy leading roles in the 2020/2022 Passion.

Julia Stenzel (Theatre Studies, Mainz) engages with the techniques, practices, and materialities involved in the reenactment of sacred suffering and bodily stigmatization in and beyond the Passion play. The chapter investigates the materiality of human body hair and its potential to be charged with charisma deriving from the performance of the Passion and the sacred figures embodied on stage. Since the early 19th century, the aforementioned hair and beard decree (Haar- und Barterlass) obliges the impersonators of the biblical figures in Oberammergau to letting their hair and beards grow from Ash Wednesday of the year before each Passion play season until the dernière. The chapter considers how the presumed “naturalness” of hair has been generating authenticity and materializing devotion, thus functioning as an interface of holiness and a reservoir of time. To explore how the hair of Oberammergau matters beyond the Passion play, the chapter discusses an exhibition in the context of the 2022 Passion play season, resulting from an artistic research project involving the last season’s performers’ hair.

Part IV traces the critical issues in the field of the literary imaginary in which a collectively shared knowledge about Oberammergau and its Passion play can be repeated, var ied, and functionalized, be it conservatively or subversively. Thus, literary works contribute to institutionalizing the village and its play.

With German philosopher Hans Blumenberg’s study Work on myth as a starting point, Jan Mohr outlines four major modes in which the traditional motifs of the Oberammergau story are varied, combined, and told anew. Blumenberg determines the myth in its cultural, functional value, which lies in the myth ordering the disordered and unmanageable diversity of the world and

making it accessible to a description. In this sense, Jan Mohr interpreted various approaches to the Oberammergau theme as work on the unclarified origins and institutional tensions of the Passion play. For example, the tradition of the historical persons who brought the plague into the village provides contradictory information. A group of literary debates with Oberammergau begins with these contradictions by inserting the historical persons into fictional stories and thus making suggestions on “how it might have been”. When the unity of village and passion play represents an established institution, it can embody cultural-critical alternative concepts. These can be used for moralizing, and ultimately restrictive role, family, and social models, as in a post-war narrative explicitly addressed to the “young generation”.

In addition, with a complementary yet slightly different focus, Martin Leutzsch (Protestant Theology, Paderborn) provides an overview of fictional passion play narratives throughout Europe. Based on this overview, which is stupendous in its breadth and unprecedented so far, he examines commonalities of literary passion play constructions in a discourse-historical approach. The leading question aims at moments of similarity between the respective Christ actor and his ‘historical’ model. Such parallels can be designed not only in a physical sense but also as a personal attitude, leading to social marginalization. From a gender-theoretical perspective, Leutzsch focuses on historically changing ideals of masculinity and shows how historical ideas of Jesus and the fictional construction of the Jesus actors converge in the Passion play texts. Jesus’ succession, it could be summed up, is designed in the Passion play stories as a performance achievement, in the narrated play itself, as well as beyond it.

Departing from one of the most popular novels on Oberammergau around 1900, Julia Stenzel furthers this gender-theoretical approach. Whilst Leutzsch shows how historical ideas of Jesus and the fictional construction of the Jesus actors converge, in a lecture of Wilhelmine von Hillern’s On the cross (1890), Stenzel focuses on how the intersections of masculinity and divinity are performed and challenged in fictional refigurations of the Oberammergau Jesus. In the 19th century, triggered by Bible historiography and new perspectives on gender, the Jesus on stage, identified as the Son of God, also qualifies as a model for multiple masculinities. Complementary, the female figures of the gospels lose their self-evidence as models for femininity. Thus, the male body of Jesus must be read in correlation to the multiple female bodies surrounding him. The critical-ness of Jesus, the man, and Mary (Magdalene), the woman, are involved in the diversification of the Passion play, especially when it comes to its popularization and distribution.

This volume was initiated before the 2020 Passion play season, and most of its contributions deal with a pre-pandemic view on Oberammergau. However, given the situation of the postponement, the approaches and attempts the chapters propose, the questions they arise, and the contexts they deal with acquire a new relevance. Since the mid-19th century, it has been an asserted potential of the Passion play to assemble people from all over the world with different cultural, social, and since the mid-20th century, even religious backgrounds.

Jan Mohr and Julia Stenzel

Since the logic of physical involvement in the ephemeral community gathering in the Passion theatre has been interfering with the biopolitical requirement of physical distancing, the connection of (mental, spiritual) health and hail has been complemented by the question of hygiene as physical health. How can gathering people from diverse cultural spheres and heterogeneous backgrounds be connected to the idea of spiritual, religious, and even bodily well-being and healing?

The Oberammergau Passion play has always shown its ability to cope with external obstacles as well as internal inconsistencies (esp. Barbato, Priest), to integrate heterogeneous influences and secondary traditions (Molter, Zerhoch), and to fuel collective as well as individual imaginations (Leutzsch, Mohr: Work on Myth, Stenzel: What Kind of Man). Facing the pandemic crisis, the officials of Oberammergau worked on integrating the threat of COVID into the story and history of the play. As we initially sketched, continuities of discontinuation were introduced, and the inevitably prolonged phase of latency leading to the 2022 season was functionalized in different ways. Conjuring up chances and challenges to refound a community of the Passion and reinvent its tradition, the story of the Passion play, once again, evidenced its potential to integrate, diversify, and confront heterogeneous ideas of its future. The success of the Oberammergau trademark lies in the capacity to endure and perpetuate this tension.

Works cited

Arnal, W. and R. T. McCutcheon. 2013. The Sacred Is the Profane. The Political Nature of “Religion”. New York: Oxford University Press.

Balme, Ch. 2014. The Theatrical Public Sphere. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Calwer, R. (ed.). 1890. Oberammergauer Blätter. Oberammergau Weekly News. Revue d’Oberammergau. Bad Kohlgrub: Faller, Buchmüller & Stockmann.

Conway, M. D. 1871. A Pilgrimage on the Ammer. Frazer’s Magazine, November 1871: 618–37.

Durkheim, É. 2013 [1895]. The Rules of Sociological Method and Selected Texts on Sociology and Its Method. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Errichiello, O. C. 2017. Philosophie und kleine Geschichte der Marke. Marken als individuelle und kollektive Sinnstifter. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Esser, H. 2005. Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Vol. 5: Institutionen. Frankfurt/M., New York: Campus.

Führding, St. 2015. Jenseits von Religion? Zur sozio-rhetorischen‚ Wende‘in der Religionswissenschaft. Bielefeld: transcript.

Hännssler, D. (ed.). 1880. Oberammergauer Fremdenführer. Munich: D. Hännssler.

McCutcheon, R. T. 1997. Manufacturing Religion. The Discourse on Sui Generis Religion and the Politics of Nostalgia. New York: Oxford University Press.

Melville, G. 1992. Institutionen als geschichtswissenschaftliches Thema. In: Institutionen und Geschichte. Theoretische Aspekte und mittelalterliche Befunde, ed. id. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 1–24.

Melville, G. (ed.). 1997. Institutionalität und Geschichtlichkeit. Ein neuer Sonderforschungsbereich stellt sich vor. Eine Informationsbroschüre im Auftrag des SFB 537 in Verbindung mit dem

Dezernat für Forschungsförderung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit der TU Dresden vom Sprecher. Dresden: Technische Universität.

Melville, G. (ed.). 2001. Institutionalität und Symbolisierung. Verstetigungen kultureller Ordnungsmuster in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau.

Melville, G. and K.-S. Rehberg (eds.). 2012. Dimensionen institutioneller Macht. Fallstudien von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau.

Melville, G. and H. Vorländer (eds.). 2002. Geltungsgeschichten. Über die Stabilisierung und Legitimierung institutioneller Ordnungen. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau.

Meyer, B. 2020. Religion as Mediation. Entangled Religions 11/3 (2020): Religion, Media, and Materiality (doi:10.13154/er.11.2020.8444).

Molter, C. 2022. ‘Made in Oberammergau’ – Materialität und Repräsentation der Oberammergauer Passions-Souvenirs. In: medioscope. Blog des Zentrums für Historische Mediologie, University of Zurich (1 July 2022). https://dlf.uzh.ch/sites/medioscope/2022/07/01/madein-oberammergau-materialitaet-und-repraesentation-der-oberammergauer- passionssouvenirs/ (accessed 23 August 2022).

Rehberg, K.-S. 1994. Institutionen als symbolische Ordnungen. Leitfragen und Grundkategorien zur Theorie und Analyse institutioneller Mechanismen. In: Die Eigenart der Institutionen. Zum Profil politischer Institutionentheorie, ed. G. Göhler. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 47–84.

Rehberg, K.-S. 2001. Weltrepräsentanz und Verkörperung. Institutionelle Analyse und Symboltheorien – Eine Einführung in systematischer Absicht. In: Institutionalität und Symbolisierung. Verstetigungen kultureller Ordnungsmuster in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, ed. G. Melville. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 3–49.

Rehberg, K.-S. 2012. Institutionelle Analyse und historische Komparatistik. Zusammenfassung der theoretischen und methodischen Grundlagen und Hauptergebnisse des Sonderforschungsbereiches ‘Institutionalität und Geschichtlichkeit’. In: Dimensionen institutioneller Macht. Fallstudien von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, eds. G. Melville and id. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 417–43.

Schilbrack, K. 2013. What Isn’t Religion? Journal of Religion 93/3: 291–318.

Scott, W. R. 2001. Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Spear, S. E. 2011. Claiming the Passion. American Fantasies of the Oberammergau Passion Play, 1923–1947. Church History 80/4 (December 2011): 832–62 (doi:10.1017/ S0009640711001235).

Wohlrab-Sahr, M. and M. Burchardt. 2011. Vielfältige Säkularitäten: Vorschlag zu einer vergleichenden Analyse religiös-säkularer Grenzziehungen. Denkströme. Journal der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 7: 53–71.

Wohlrab-Sahr, M. and M. Burchardt. 2017. Revisiting the Secular: Multiple Secularities and Pathways to Modernity. Working Paper Series of the HCAS “Multiple Secularities – Beyond the West, Beyond Modernities” 2. Leipzig: Política & Sociedade.

Wohlrab-Sahr, M. and Ch. Kleine. 2021. Historicizing Secularity: A Proposal for Comparative Research from a Global Perspective. Comparative Sociology 20: 287–316.