in Macrobrachium rosenbergii

Kianann Tan 1 , Jiongying Yu 1 , Shouli Liao , Jiarui Huang , Meng Li , Weimin Wang *

College of Fisheries, Key Lab of Agricultural Animal Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction of Ministry of Education, Key Lab of Freshwater Animal Breeding, Ministry of Agriculture, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Macrobrachium rosenbergii

Androgenic gland ablation

Transcriptomic profiling

Sex-reversal

Gonad development

ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

M. rosenbergii is a giant freshwater prawn from Malaysia and Thailand (Aflalo et al., 2012). Under natural conditions, M. rosenbergii can survive in both brackish and freshwater environments (Nagamine et al., 1980). M. rosenbergii is an important freshwater prawn cultivation species (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2009). The monosex culture has more merit in the aquaculture sector, including growth enhancement and reduced sexual territorial behaviour (Sagi and Aflalo, 2005). Many solutions for realizing the monosex culture have been applied to crustacean production over the last 30 years (Curtis and Jones, 1995; Lawrence, 2004; Siddiqui et al., 1997). Some techniques, such as androgenic gland ablation, androgenic gland transplantation, and dsRNA and siRNA knockdown of insulin-like androgenic gland hormone (IAG), have been developed to achieve monosex culture (Nagamine et al., 1980; Ventura et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2020). The male reproductive system accessory endocrine gland was discovered in Callinectes

* Corresponding author.

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquaculture https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738224

Androgenic glands (AGs) regulate male sexual differentiation in M. rosenbergii, and AG ablation may induce sexreversal and male-to-neofemale transformation. However, information on gonad development following AG ablation is scarce. To investigate the effects of gonad development and sex reversal after AG ablation, we utilized transcriptomic profiling, RT–qPCR, and histological and morphological observation. Transcriptomic profiling generated 42.32–42.92 million clean reads. A total of 94,747 unigenes were assembled with a total length, average length, N50, and GC content of 160,460,655 bp, 1693 bp, 3438 bp, and 39.86%, respectively. Hsp70, IGFBP7, Mar-Mrr, Serpin, TUBA3, CREB, EF1a, and BMP7 were identified as differentially expressed by gonad transcriptome profiling after AG ablation. Interestingly, the Rap1, Hippo, PI3K, oxytocin, thyroid hormone, and apoptosis signalling pathways were all found to be involved in the sex-reversal process by regulating cell proliferation and gonad development and maintaining homeostasis. Sexual morphology features and histological changes following AG ablation validated the sex reversal from male to neofemale. Sexual manipulation permits monosex culture while considerably improving output yield. Taken together, these findings provide insight into the sexual reversal mechanism of M. rosenbergii after AG ablation. The findings in this study may aid in the future investigation of the sex-reversal mechanisms in other decapod species and offer a new breeding and culture strategy for M. rosenbergii aquaculture industry.

sapidus and was initially described as a tubule accessary gland attached at the end of the vas deferens (Cronin, 1947). This accessory gland was formally named the androgenic gland in 1955 (Charniaux-Cotton, 1954). The androgenic gland regulates the sexual differentiation and development of male primary and secondary characteristics in crustaceans (Sagi et al., 1990). Some have observed that removing or transplanting the androgenic gland can lead to sex-reversal in decapods, implying that the androgenic gland is crucial for sexual differentiation (Aflalo et al., 2006; Barki et al., 2006; Manor et al., 2004; Nagamine et al., 1980). Previous studies have shown that by removing the androgenic gland during the early stages of sexual development, males will sex reverse into neofemales (Sagi and Cohen, 1990; Ventura, 2018). In contrast, after androgenic gland transplantation, the female external sexual phenotype was degraded, oocyte production was retarded, and vitellogenesis was inhibited (Charniaux-Cotton, 1957; Charniaux-Cotton, 1962; Malecha et al., 1992).

Although it is generally understood that the androgenic gland

E-mail addresses: kianann1987@webmail.hzau.edu.cn (K. Tan), yujiongying@webmail.hzau.edu.cn (J. Yu), wangwm@mail.hzau.edu.cn (W. Wang).

1 Kianann Tan and Jiongying Yu contributed equally to this work.

Received 7 September 2021; Received in revised form 29 March 2022; Accepted 4 April 2022

Availableonline7April2022

0044-8486/©2022ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

functions as a regulator in male sex determination, differentiation, and maintenance of male primary and secondary sexual characteristics (Nagamine et al., 1980), the actual functional component is the androgenic gland hormone (also known as insulin-like androgenic gland hormone, IAG). The androgenic gland secretes IAG in decapods (Ventura et al., 2011). IAG has been extensively researched, and an ‘IAG switch’ has been proposed to regulate sexual development and differentiation in decapods (Levy and Sagi, 2020). IAG expression ensures male sexual determination, but IAG depletion results in sex reversal in male decapods. According to some reports, knockdown of IAG using dsRNA or siRNA induces sex-reversal, resulting in testis to ovary transformation and the production of neofemales (Ventura et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2020). Furthermore, the androgenic gland cell suspension approach successfully yields WW chromosome males that lack a masculine Z chromosome (Levy et al., 2019).

Many strategies have been used to examine sex-reversal mechanisms, including transcriptome sequencing analysis (high-throughput sequencing technology) and RNA interference (RNAi). However, the utility of RNAi technology is limited. RNAi can only be used to investigate functional genes. Transcriptome sequencing analysis is the collection of all transcription products in a cell under physiological conditions (Guo et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014). Transcriptomic analysis can be used to investigate gene transcription under certain conditions, as well as the regulation and molecular mechanism of a biological network (Li et al., 2014). High-throughput sequencing technology has sped up the analysis of genomic or genetic information and has been widely utilized to improve the economic traits of crops, livestock, and aquaculture species. In recent years, high-throughput sequencing has also been applied to screen genes in crustaceans for economic traits, reproductive growth and disease resistance (Jung et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2012). A Macrobrachium nipponense androgenic gland transcriptome study was performed, and the results revealed 47 novel sex-related gene families. In comparison to the earlier transcriptome analysis of M. nipponense (Ma et al., 2012; Qiao et al., 2012), 40 candidate genes related to sex regulation were discovered (Jin et al., 2013).

Androgenic gland ablation in M. rosenbergii demonstrated the significance of the androgenic gland in male sexual differentiation, as the ablated males were entirely feminized into functional neofemales (Aflalo et al., 2006; Sagi and Aflalo, 2005). However, research into the molecular mechanisms involved in sex-reversal is scarce, particularly during the transformation of the testis into the ovary, which involves testis degeneration and ovary development following androgenic gland ablation. The purpose of this study was to investigate the molecular mechanisms that occur during the transformation of the testis to the ovary following androgenic gland ablation. The effect of androgenic gland ablation on gonad development and sex-reversal in M. rosenbergii juveniles was investigated using transcriptomic profiling, histological and morphological observation, and RT–qPCR.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

All males (3–4 cm, carapace length; 2 months old) of M. rosenbergii utilized in this experiment were reared and bred at the prawn breeding hatchery of Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Males were cultivated in 300 L tanks. The culture tank’s water was aerated, and the temperature was maintained at 28 ± 0.5 ◦ C. M. rosenbergii was fed shrimp pellets (Yuequn, Guangdong, China) four times a day. The nutrition content of the shrimp pellet was ≥54% crude protein, ≥ 11% crude lipid, ≤ 15% ash, ≤ 2% crude fibre, and ≤ 10% moisture. The Huazhong Agricultural University’s Scientific Ethics Committee authorized the experimental methodologies and animals used in this study. The Scientific Ethics Committee’s approval code is HZAUFI-2019-012.

2.2. Androgenic gland ablation

One hundred tails of male (3–4 cm) M. rosenbergii were chosen for bilateral androgenic gland ablation. Before performing surgical ablation, all surgical tools were disinfected using 1 ppm of complex iodine solution (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany). Male M. rosenbergii were anaesthetized on ice for 10 s prior to surgical ablation. Surgical scissors were used to remove the fifth pereiopods. Then, the terminal ampullae and vas deferens were extracted from the body using surgical forceps. The androgenic gland was attached to the medial concave surface at the end of the vas deferens and terminal ampullae. Thus, removing the terminal ampullae and vas deferens results in removal of the androgenic gland. Fig. 1 depicts the AG ablation procedure. Following surgical ablation, the wounds at the fifth pereiopods were disinfected using a diluted iodine solution (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany). The ablated M. rosenbergii was transferred into a 300 L tank for further culture. The water temperature was kept constant at 28 ± 0.5 ◦ C. M. rosenbergii was fed shrimp pellets (Yuequn, Guangdong, China) three times a day. Dead M. rosenbergii were removed from the culture tank.

2.3. Sample collections

Gonad specimens were collected every two weeks after androgenic gland ablation for a total of 6 weeks (when the testis had completely transformed into an ovary). The sampling weeks were assigned into four stages: Stage 1: 0 days after androgenic gland ablation (week 0); Stage 2: 14 days after androgenic gland ablation (week 2); Stage 3: 28 days after androgenic gland ablation (week 4); Stage 4: 42 days after androgenic gland ablation (week 6). M. rosenbergii (n = 6) with androgenic gland ablation were anaesthetized on ice for 3 min before dissection. To prevent RNA degeneration, the gonad specimens (n = 3) were surgically excised and immediately placed into liquid nitrogen. Total RNA extraction was performed on the gonad specimens. Another set of gonad specimens (testis and ovary, n = 3) were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for subsequent histological observation.

2.4. Morphological and histological observation

During the sex-reversal process, changes in morphological features, such as appendix masculinity, appendix interna, ovipositing setae, ovigerous setae, genital papillae, brood chambers, and setal buds, were observed. The collected gonad specimens (testis and ovary) were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological observation. The preserved specimens were cleaned and encased in paraffin wax. A microtome (Leica, IL, USA) was used to cut six-micron thin sections, which were then mounted onto glass microscope slides. Next, the slides were counterstained with haematoxylin and eosin. An optical light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe the stained slides.

2.5. RNA isolation and transcriptome sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the testis and ovary tissues using TRIzol Reagent (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The gDNA eraser (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China) was used to eliminate genomic DNA from isolated RNA samples. The quantity and quality of isolated RNA were assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) and a Nanodrop ND2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), respectively. The isolated RNAs were further quantified using the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA), and an equal weight of isolated RNA from the testis of each individual was pooled and reversetranscribed into cDNAs for sequencing as PE125 on the Illumina HiSeq™ 2300 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, USA) by BGI Genomic (Shenzhen, China). For RNA sequencing, each sample at each stage was sequenced in triplicate.

Fig. 1. The androgenic gland ablation procedure. (A) Surgically removal of the fifth pereiopod. (B) Forceps were used to locate and pinched the terminal ampullae. (C) Removed the terminal ampullae. (D) The terminal ampullae (with androgenic gland) and vas deferens of M. rosenbergii were entirely excised.

2.6. De novo assembly and annotation

After RNA sequencing, the FastQC application version 0.11.5 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) was used to evaluate and visualize the quality of raw reads. The NGS QC Toolkit filtered and removed low-quality reads and those read with adaptors (Patel and Jain, 2012). The Trinity platform, including Inchworm, Chrysalis and Butterfly, was used to assemble the de novo transcriptome into transcripts using Kmer = 25 (Grabherr et al., 2011). To obtain the nonredundant unigenes, the TGI Clustering Tool version 2.1 was used to remove further sequence splicing and redundancy (Pertea et al., 2003). BLASTx version v2.2.26 was used to perform the annotation process, with an E-value cut off point of 10 5 . The obtained unigenes were blasted and annotated using NCBI nonredundant protein sequences (NR), NCBI nucleotide sequences (NT), Swiss-Prot protein database, Pfam, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), euKaryotic Orthology Groups (KOG), and Gene Ontology (GO).

2.7. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis

Bowtie2 software was used to quantify the number of reads that mapped to the genes (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). All read counts from each sample were loaded into the R package DESeq2 for DEG analysis (Love et al., 2014). The expected number of fragments per kilobase of transcript sequence per million base pairs sequenced (FPKM values) were used to predict differential gene expression levels, and the FPKM values were calculated based on the base mean values. The p value was regulated by the q value (false discovery rate), where the q value <0.05 and | log2 (fold change) | > 1 were set as the thresholds for significant differential expression. The GOseq package was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for the DEGs, which was based on the Wallenius noncentral hypergeometric distribution (Young et al., 2010). The significantly enriched pathways were

identified using KOBAS 2.0 with a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05 (Xie et al., 2011).

2.8. Quantitative real-time PCR assay

Total RNA from the testis and ovary was isolated using TRIzol reagent (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and quantity of isolated RNA samples were determined using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a Nanodrop ND2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). After evaluation, the samples were stored at 80 ◦ C until use. The Serpin (Accession number: EL696020), Hsp70 (Accession number: AY466445), MZT (Accession number: MH883364), CREB (Accession number: JZ905131), Caspase (Accession number: KF878972), TUBA3 (Accession number: EL696409), EF1a (Accession number: JZ905060), and IGFBP7 (Accession number: EL696430) genes were amplified using the forward and reverse primers listed in Table 1 β-actin was employed as a reference gene, and its stability in M. rosenbergii has been confirmed (Thongbuakaew et al., 2016). The forward and reverse primers for β-actin are listed in Table 5. The first strand of cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription utilizing the Prime Script RT Reagent kit with a genomic DNA (gDNA) eraser (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China). All samples were examined using Quantstudio 6 Flex (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher, USA) to examine the transcription levels of Serpin, Hsp70, MZT, CREB, Caspase, TUBA3, EF1a, IGFBP7, and β-actin The RT–qPCR analysis was performed in a 96-well plate with each well containing 20 μL of reaction mixture. The reaction mixture contained 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China), 0.4 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL of cDNA template, and 7.2 μL of sterilized double distilled water (ddH2O). The RT–qPCR conditions were as follows: predenaturation at 95 ◦ C for 5 mins, followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95 ◦ C for 10 s and 72 ◦ C for 15 s. Each sample was tested in triplicate. Three replicates were used to calculate

K.

Table 1

Forward and reverse primers used for transcription level quantification by RT-qPCR.

Gene name

Primer sequence (5′ to 3′ )

Serpin-F GTCAGCATCACAACGGAAGG

Serpin-R TCCTCCTGATTTTCCTGGGG

Hsp70-F ACAAGGGTCGCCTCAGTAAA

Hsp70-R CCTCTGGCACCTTGTCCTTA

MZT-F GGTCTTCCATCGCAGTTGTG

MZT-R CGTTGTCTGCTCCAATCCTG

CREB-F TGCGTAGTTGAGACCCATGT

CREB-R TTGAGGAAGCGCAAACACTG

Caspase-F CATCTTGAAGGCAGCGAGTC

Caspase-R TCTGCAGGCCTGAATGAAGA

TUBA3-F TGGGCCAGACTTAACCACAA

TUBA3-R CCTTCGTCTCGGCCTCTTAA

EF1a-F CACCACGAAGCTCTGACTGA

EF1a-R CAGTCGAGCACAGGGGAATA

IGFBP7-F CATCCCTTGCCAGAGAGACA

IGFBP7-R CATTTGCCGCGTCTATTCCA

β-actin-F CTCCATCATGAAGTGCGACG

β-actin-R AGGTGGGGCAATGATCTTGA

the average value per gene. The 2-△△Ct method was used to calculate the transcript levels of each gene (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

2.9. Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Analytics, VA, USA) was used to examine all the statistical data. The homogeneity of the variances was tested by Levene’s test. The residuals of the data were normally distributed by Shapiro-Wilk test. Then, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey-HSD test was used to evaluate significant differences between samples. The statistical significance threshold was set at p < 0.05 (significant).

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptome sequencing and assembly

The DNBSEQ platform was used to sequence 12 samples from 4 developmental stages, including S1–1, S1–2, S1–3, S2–1, S2–2, S2–3, S3–1, S3–2, S3–3, S4–1, S4–2, and S4–3. A total of 43.82–45.57 million raw reads were sequenced. A total of 42.32–42.92 million clean reads were obtained after filtering and removing low-quality and contaminated reads (Table 2). Then, 94,747 unigenes with a total length, average length, N50, and GC content of 160,460,655 bp, 1693 bp, 3438 bp, and 39.86% were assembled, respectively (Table S1, Fig. S1). Furthermore, 37,851 coding sequences (CDSs) (Table S2) and 40,305 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) (Table S3) were discovered. The NGS sequenced data are available in NCBI under the BioProject number PRJNA787407.

3.2. Functional annotation and classification of the transcriptome

A total of 94,747 unigenes were then annotated against seven major functional databases (NR, NT, SwissProt, KEGG, KOG, Pfam, and GO), resulting in 40,892 (NR: 43.16%), 20,738 (NT: 21.989%), 30,407 (SwissProt: 32.09%), 32,193 (KEGG: 33.98%), 29,130 (KOG: 30.75%), 32,820 (Pfam: 34.64%), and 24,639 (GO: 26.01%). All annotated unigenes were classified into three functional categories in the Gene Ontology (GO) classification: biological process (38.52%), molecular functions (33.31%), and cellular components (28.17%) (Table S4, Fig. S2). Cellular anatomical entity and intracellular terms were significantly enriched in cellular components, followed by cellular process and metabolic process in biological process. Binding and catalytic activity were the most well-represented terms in the molecular function category. Annotated unigenes were assigned to six pathways in the

KEGG pathway analysis, including organismal systems, metabolism, human diseases, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, and cellular processes (Table S5, Fig. S3). Among these genes, 5103, 2941, 2910, 2377, and 2370 were related to signal transduction, the immune system, the endocrine system, translation, and transport and catabolism, respectively. For the KOG annotation, three functional types, metabolic pathways, information storage and processing, and cellular processes and signalling, were identified and subsequently classified into 25 divisions. General function prediction only (21.75%), signal transduction mechanisms (12.19%), function unknown (7.89%), and posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones (7.54%) were the most highly enriched terms in KOG functional annotation (Table S6, Fig. S4).

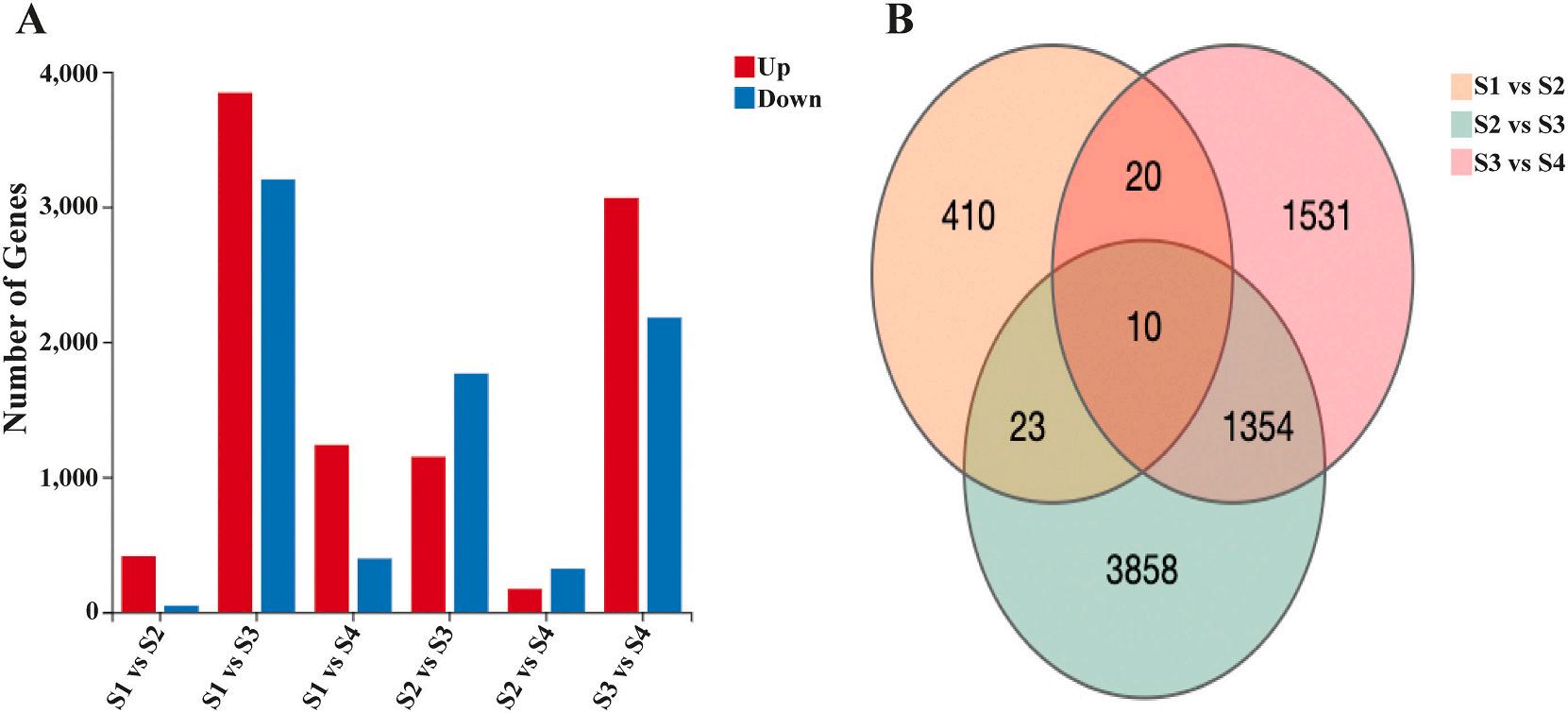

3.3. Differential gene expression (DEGs) analysis

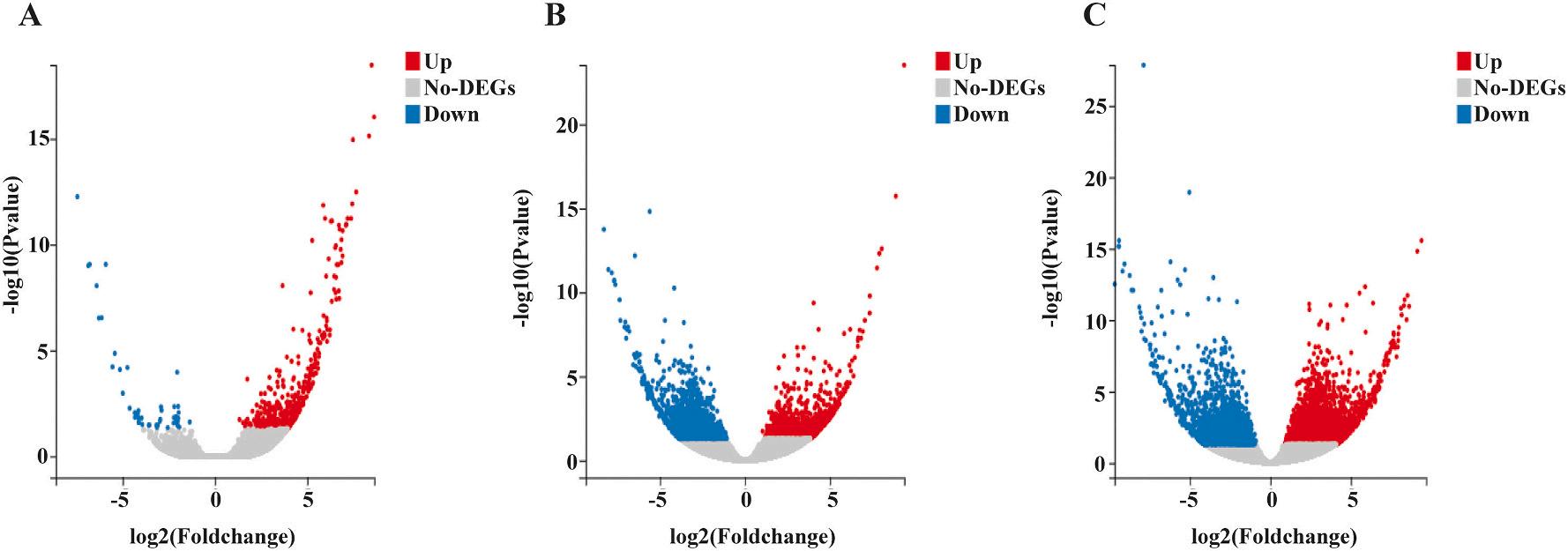

The six comparative groups yielded a total of 17,799 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). There were 463, 7047, 1635, 2915, 494, and 5245 significant DEGs found between the S1 vs. S2, S1 vs. S3, S1 vs. S4, S2 vs. S3, S2 vs. S4 and S3 vs. S4 groups, respectively (Fig. 2A). Ten DEGs were discovered through a three-way Venn diagram in the S1 vs. S2, S2 vs. S3, and S3 vs. S4 comparisons (Fig. 2B). The volcano plot illustrates the upregulated and downregulated genes in the S1 vs. S2, S2 vs. S3, and S3 vs. S4 groups (Fig. 3). Based on NR annotation, heat shock protein 70 (hsp70), insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP7), male reproductive-related protein A, male reproductive-related protein B, serine protease inhibitor (Serpin), chorion peroxidase-like (Pxt), tubulin alpha 3 chain, and ccr4-not transcription complex subunit 6-like (CCR4) were identified to play important roles in sexual development and the endocrine system. cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB), caspase 1, elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1a), DNA-direct RNA polymerase III subunit RCP9 (CRCP), bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7), and mitotic-spindle organizing protein (MZT) were also found to be involved in gonad degeneration and development during testicular to ovarian transformation. Table 3 displays the transcript levels of the selected genes.

Table 2

Summary statistics for the transcriptome sequencing data from each sample.a

a Note: Stage 1: 0 day after androgenic gland ablation; Stage 2: 14 days after androgenic gland ablation; Stage 3: 28 days after androgenic gland ablation; Stage 4: 42 days after androgenic gland ablation.

identified in the S1 vs S2, S2 vs S3, and S3 vs S4 comparisons.

Fig. 3. The expression volcano plot demonstrated the up- and down-regulated of identified DEGs. (A) S1 vs S2. (B) S2 vs S3. (C) S3 vs S4. Indication, Up: upregulated; Down: down-regulated.

Table 3

The transcription level of annotated DEGs involved in the sexual development and endocrine system.a

Gene annotation (matched species) Fold change

vs S2 S2 vs S3

Heat shock protein 70 [Macrobrachium rosenbergii] + 6.92 + 2.29 - 1.05

Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 [M. rosenbergii] + 3.25 - 1.92 + 1.68

Male reproductive-related protein A [M. rosenbergii] + 6.22 - 2.79 0

Male reproductive-related protein B [M. rosenbergii] + 4.82 - 0.78 0

Serine protease inhibitor [M. rosenbergii] + 4.48 - 2.54 + 3.35

Chorion peroxidase-like [Penaeus vannamei] + 3.36 - 0.85 +2.60

Tubulin alpha 3 chain [M. rosenbergii] + 2.14 - 0.64 + 1.17

CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 9-like [P. vannamei] + 5.42 - 0.85 + 1.80

cAMP responsive element binding protein [Procambarus clarkii] + 3.65 + 0.34 - 1.60

Caspase 1 [P. vannamei] + 3.17 - 0.85 - 1.60

Elongation factor-1-alpha [M. rosenbergii] + 3.76 + 1.11 + 0.88

DNA-directed RNA polymerase III subunit RPC9like [P. vannamei] + 5.14 + 0.14 + 1.51

Bone morphogenetic protein 7 [Palaemon carinicauda] + 3.92 - 0.82 + 0.79

Mitotic spindle organizing protein [M. rosenbergii] + 2.58 - 0.96 - 0.30

a Indicator: ‘+’ represent up-regulated, ‘-’ represent down-regulated.

3.4. Functional categorization (GO and KEGG) of DEGs

Cellular anatomical entity, binding, catalytic activity, cellular process, intracellular, and metabolic process were revealed to have the highest number of candidate genes in the S1 vs. S2, S2 vs. S3, and S3 vs. S4 groups in the GO analysis of DEGs. A total of 130, 102, 63, 62, and 49 candidate genes were enriched in cellular anatomical entity, binding, catalytic activity, cellular process, and intracellular, respectively, in the S1 vs. S2 group. In the S2 vs. S3 group, candidate genes in cellular anatomical entity, binding, catalytic activity, cellular process, and metabolic process were found to be 656, 572, 494, 357, and 252, respectively. The number of candidate genes for cellular anatomical entity, binding, catalytic activity, cellular process, and metabolic process in the S3 vs. S4 group was 1142, 982, 828, 795, and 534, respectively. Table 4 illustrates the involvement of GO terms (up- and downregulated) in the S1 vs. S2, S2 vs. S3, and S3 vs. S4 groups. The majority of DEGs were annotated into immune system, translation, signal transduction, signalling molecules and interaction, cell growth and death, endocrine system, and transport and catabolism in the KEGG analysis. In the S1 vs. S2 group, a total of 53, 52, 29, 20, and 29 candidate genes were annotated in the immune system, signal transduction, signalling molecules and interaction, cell growth and death, and endocrine system, respectively. Furthermore, in the S2 vs. S3 group, 233, 167, 131, 130, and 86 candidate genes were assigned to signal transduction, the immune system, the endocrine system, transport and

Fig. 2. The summary of identified DEGs. (A) The number of up- and down-regulated DEGs. (B) Three-way Venn diagram of all evidencing numbers of the DEGs

Table 4

The list of GO terms (up- and down-regulated) in S1 vs S2, S2 vs S3, and S3 vs S4 groups.

Group Go term

Up-regulated Down-regulated

- Integral component membrane

- Chromatin remodeling

S1 vs S2

S2 vs S3

S3 vs S4

- ATP binding

- Extracellular region

- Insulin receptor signalling pathway

- Initiation complex

- mRNA processing

- RNA binding

- Growth factor activity

- Calcium ion binding

- Bicellular tight junction assembly

- - NAD binding

- Regulation of microtubule polymerization or depolymerization

- Wnt signalling pathway

- Integral component of membrane

- Intracellular signal transduction

- Signal transduction

- Protein phosphorylation

- Regulation of actin cytoskeleton organization

- Cell-cell adhesion

- Adherens junction

- Plasma membrane organization

- Regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase

- Metal ion binding

- Helicase activity

- ATP binding

- Ligase activity

- Ubiquitin-protein transferase activity

- Metal ion binding

- Protein kinase activity

- ATP binding

- voltage-gated chloride channel activity

catabolism, and cell growth and death, respectively. In the S3 vs. S4 group, a total of 388, 235, 201, 249, and 189 candidate genes were annotated into signal transduction, translation, endocrine system, immune system, and transport and catabolism, respectively. Table 5 shows

Table 5

The list of KEGG signalling pathways and the number of annotated candidate genes.

Group Term Signalling pathway Gene number

Immune system Platelet activation 11

Signal transduction

S1 vs S2

Signalling molecules and interaction

Cell growth and death

Endocrine system

Signal transduction

S2 vs S3

Leukocyte transendothelial migration 10

Rap1 signalling pathway 17 Hippo signalling pathway 12

ECM-receptor interaction 14

Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction 14

Apoptosis 11 Cellular senescence 4

Oxytocin signalling pathway 13 Thyroid hormone signalling pathway 10

Rap1 signalling pathway 43 PI3K signalling pathway 38

Immune system IL-17 signalling pathway 38 Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation 20

Endocrine system

Thyroid hormone signalling pathway 31

Oxytocin signalling pathway 21

Transport and catabolism Phagosome 40 Lysosome 38

Cell growth and death

Signal transduction

S3 vs S4

Apoptosis 29

Necroptosis 19

PI3K signalling pathway 76

Rap1 signalling pathway 58

Translation RNA transport 127

Endocrine system

Immune system

mRNA surveillance pathway 71

Thyroid hormone signalling pathway 50

Oxytocin signalling pathway 33

IL-17 signalling pathway 64

Platelet activation 34

Transport and catabolism Endocytosis 78 Lysosome 36

the top KEGG signalling pathways and the number of annotated candidate genes in each.

3.5. Histological and morphological study

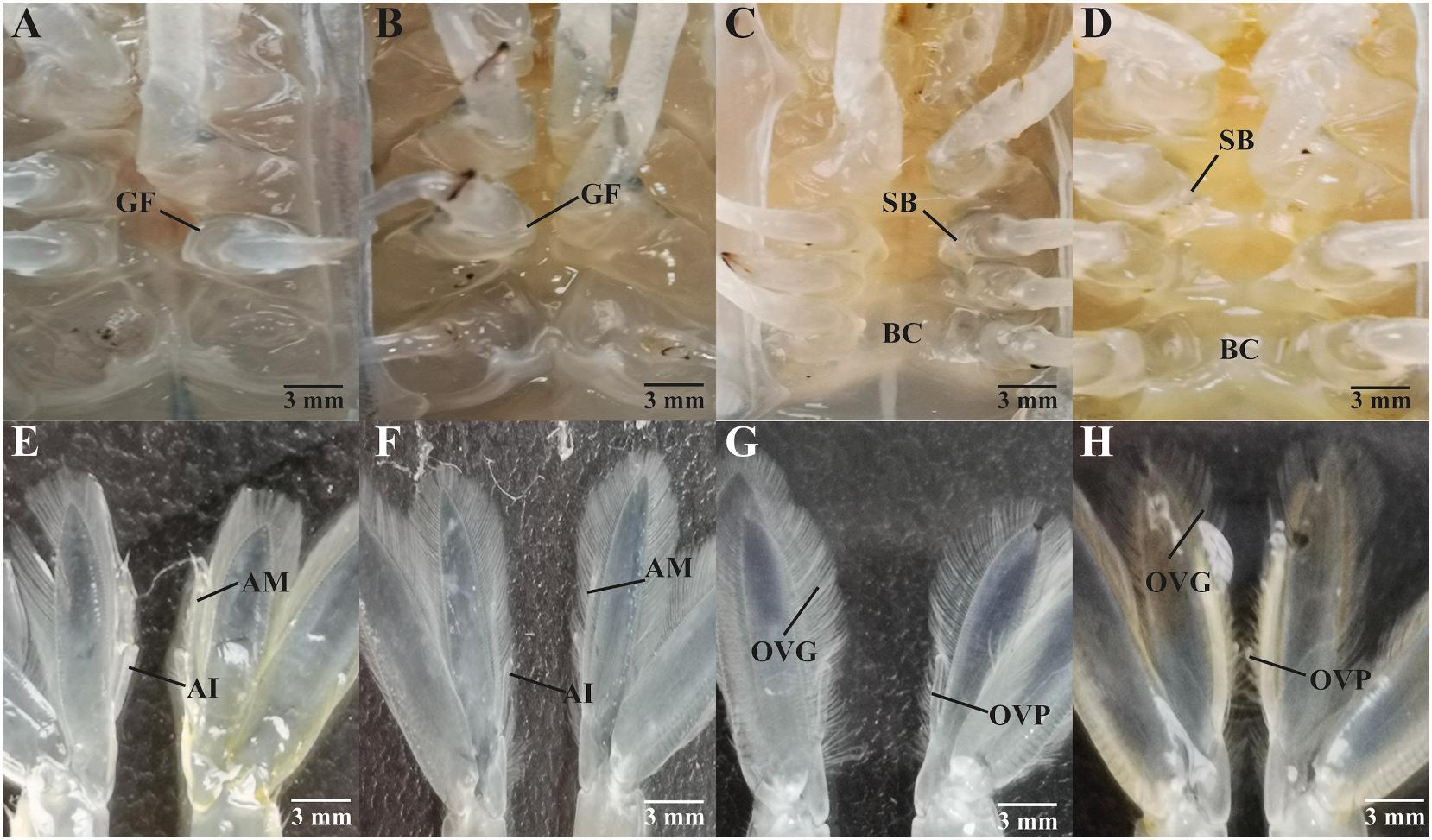

Histological observation is an excellent method for studying and examining changes in the testis after androgenic gland (AG) ablation. Prior to observation, the gonads were sectioned and stained with haematoxylin-eosin. The seminiferous lobules of the testis can be easily detected before AG ablation and are completely occupied with spermatozoa (Fig. 4A). The seminiferous lobules of the testis were loosely oriented after two weeks of AG ablation, and many spermatocytes were observed (Fig. 4B). Four weeks after AG ablation, several previtellogenic oocytes and developing oocytes were observed (Fig. 4C). The sixth week after AG ablation, there was better proliferation of developing oocytes (Fig. 4D) that looked like vitellogenic oocytes in the female ovary (Fig. 4E). Of note, the anatomy of the testis before AG ablation is comparable to that of a mature male (Fig. 4F).

After AG ablation, the sexual morphological features of the ablated male changed, particularly in the gonopore flap, genital papillae, appendix masculine, and appendix interna. The gonopore flap of M. rosenbergii can be seen at the ventral site 0 and 14 days following AG ablation (Fig. 5A, B). Female phenotypes such as setal bud and brood chamber were observed instead of gonopore flap and genital papillae as development progressed (Fig. 5C, D). On the other hand, the appendix masculine and appendix interna can be plainly seen on the second pleopod on 0 and 14 days after AG ablation (Fig. 5E, F). However, as development progressed, the second pleopod, ovigerous setae and ovipositing setae (Fig. 5G, H) were observed instead of the appendix masculine and appendix interna.

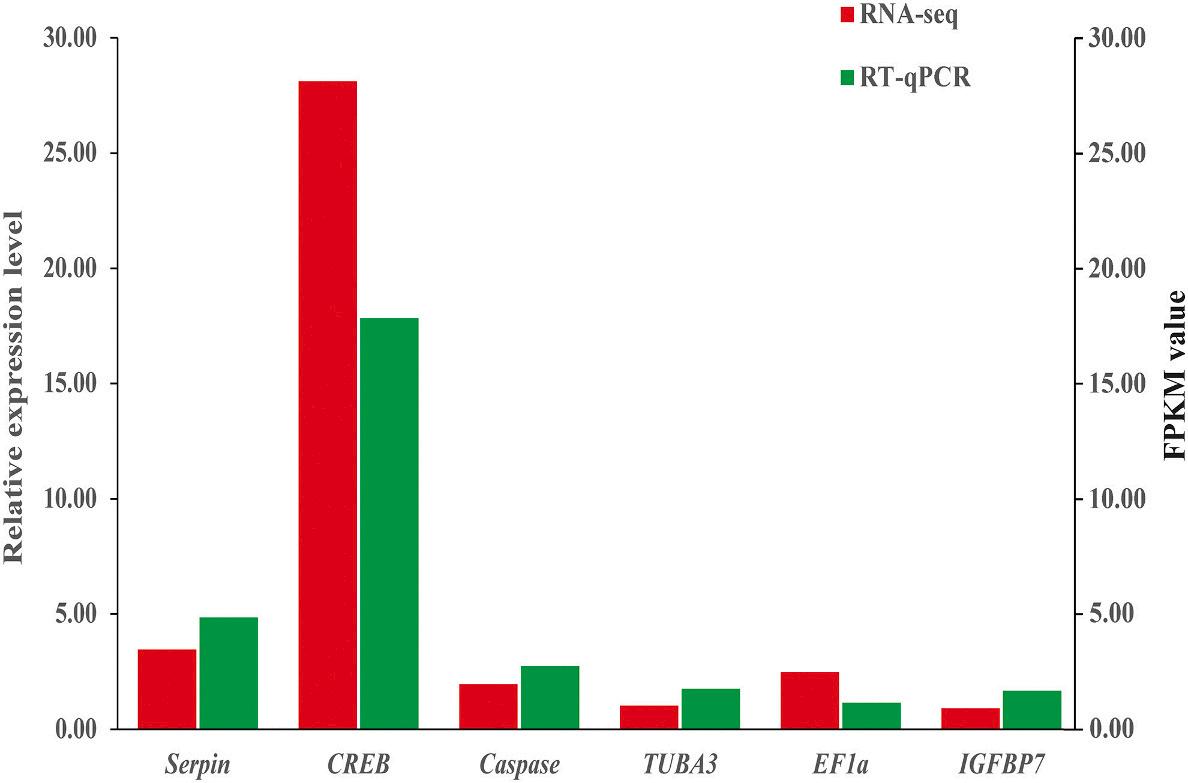

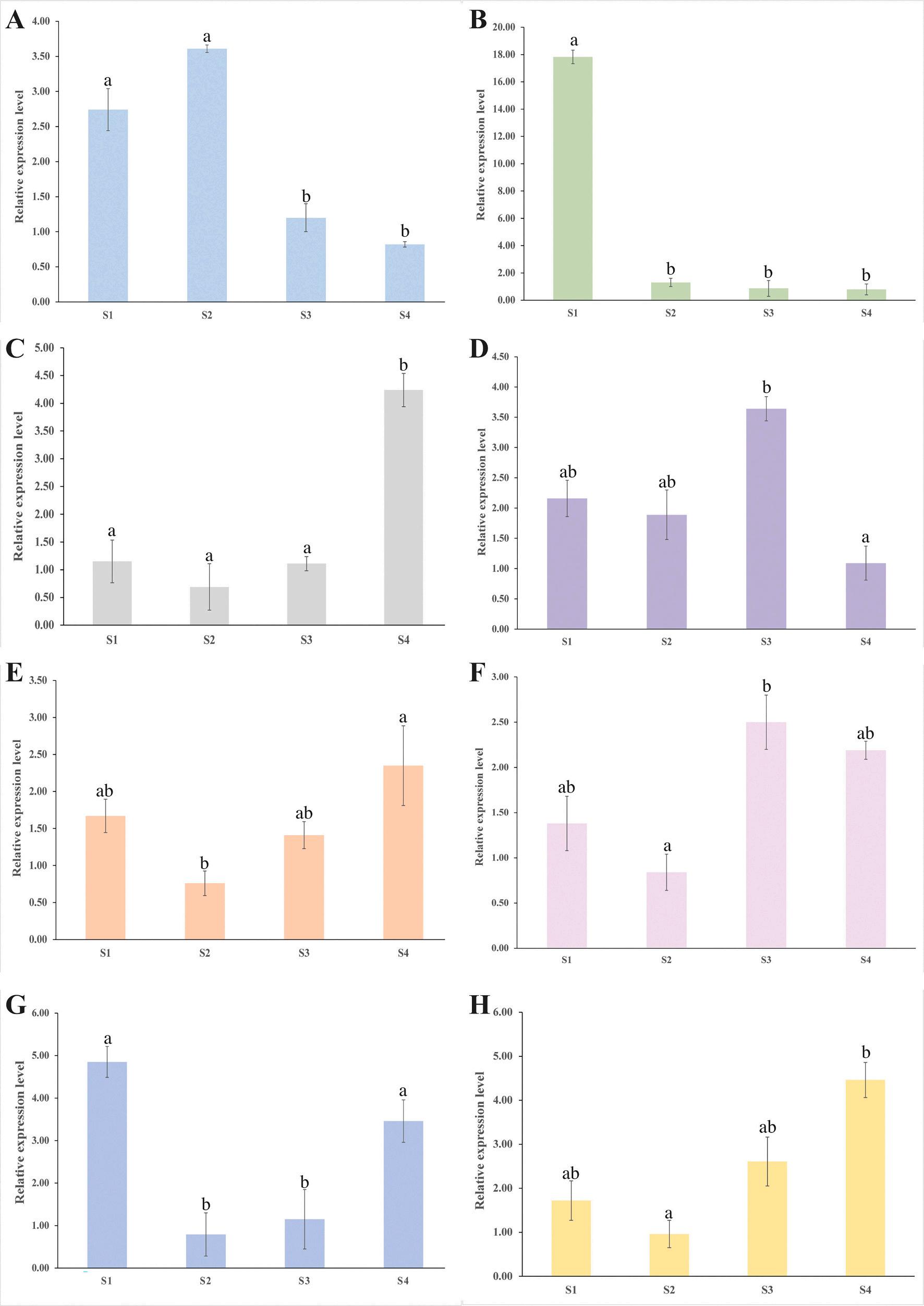

3.6. RNA-seq validation and quantification analysis of mRNA with RTqPCR

Serpin, CREB, Caspase, TUBA3, EF1a, and IGFBP7 were chosen for RNA-seq data validation in M. rosenbergii RT–qPCR was used to quantify these selected genes. The RT–qPCR results demonstrated concordance between the RNA-seq and RT–qPCR results, indicating that the RNA-seq data were trustworthy (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the transcription patterns of Serpin, CREB, Caspase, TUBA3, EF1a, IGFBP7, Hsp70, and MZT were studied across the four gonad development stages after AG ablation (Fig. 7). During stage 1 (0 days after AG ablation), CREB and Serpin displayed the highest transcript levels, while EF1a had the lowest transcript levels. Caspase exhibited the highest transcript levels, whereas CREB had the lowest levels as the gonad continued to develop (14 days after AG ablation). At stage 3 (28 days after AG ablation), CREB still had the lowest transcript levels, while Hsp70 and MZT transcript levels increased dramatically to reach their highest levels. EF1a, IGFBP7, and TUBA3 had the highest transcript levels, but CREB still exhibited the lowest transcript levels 42 days after AG ablation.

4. Discussion

M. rosenbergii monosex culture outperforms mixed sex culture in the aquaculture industry. M. rosenbergii can devote all its energy to growth and development in the monosex population, resulting in rapid growth (Mohanakumaran Nair et al., 2006; Levy et al., 2017). As a result, several approaches for achieving all-male monosex culture have been developed and deployed, including manual segregation, dsRNA or siRNA knockdown, and androgenic gland ablation (Sagi et al., 1990; Ventura et al., 2012). According to several studies, the androgenic gland plays an important role in the sex differentiation mechanisms of crustaceans, including M. rosenbergii (Charniaux-Cotton, 1962; Katakura, 1989; Sagi et al., 1997; Sagi et al., 1988). M. rosenbergii androgenic gland ablation causes sex-reversal, and IAG knockdown also induced sexreversal. The genes and signalling pathways involved in gonadal

haematoxylin-eosin after AG ablation. (A) AG ablated male, 0 days after AG ablation. (B) AG ablated male, 14 days after AG ablation. (C) AG ablated male, 28 days after AG ablation. (D) AG ablated male, 42 days after AG ablation. (E) Female. (F) Male. SC, spermatocytes; SZ, spermatozoa; PO, previtellogenic oocytes; DO, developing oocytes; VO, vitellogenic oocytes.

development following androgenic gland ablation were discovered in this study. Furthermore, the morphological features and histological changes were investigated.

Several mRNAs, including heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), male reproductive-related protein (Mar-Mrr), serine protease inhibitor (Serpin), tubulin alpha 3 chain (TUBA3), cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB), elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1a), and bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7), were differentially expressed in the transcriptomic profiling of gonads after AG ablation. In general, gonad development necessitates a high energy supply, and heat shock proteins may serve as a major stress tolerance mechanism and contribute to cellular energy requirements in crustaceans, including M. rosenbergii Heat shock proteins were previously found to be ubiquitous and transcribed in all organisms, and they were recognized to improve stress tolerance and facilitating protein

synthesis efficiency (Brokordt et al., 2015; Javid et al., 2007). Furthermore, heat shock proteins play an important role in protein biogenesis by preventing premature folding and polymerization of polypeptides (Frydman et al., 1994; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl, 2002). Hsp70 was expressed during testis to ovary transformation in this study, similar to the findings of Brokordt et al., who reported that Hsp70 is expressed during the gonad maturation process in Argopecten purpuratus (Brokordt et al., 2015). In addition, a previous study reported that Hsp70 was substantially expressed during the early stages of gonad development in Gammarus fossarum, significantly decreasing when it matured (Schirling et al., 2004), consistent with the findings in our study. Spermatogenesis was halted, and the testis degenerated after AG ablation. As a result, it is speculated that Hsp70 not only functions in stress tolerance but also rescues the damaged proteins, prevents aggregation and aids in the retention of proteins and irreversible damage during testis degeneration

Fig. 4. The histological section of the gonads stained with

Fig. 5. The sexual morphology of the ventral surface and second pleopods in AG ablated male M. rosenbergii. (A) Ventral surface of an AG ablated male, 0 days after AG ablation. (B) Ventral surface of an AG ablated male, 14 days after AG ablation. (C) Ventral surface of an AG ablated male, 28 days after AG ablation. (D) Ventral surface of an AG ablated male, 42 days after AG ablation. (E) Second pleopod of an AG ablated male, 0 days after AG ablation. (F) Second pleopod of an AG ablated male, 14 days after AG ablation. (G) Second pleopod of an AG ablated male, 28 days after AG ablation. (H) Second pleopod of an AG ablated male, 42 days after AG ablation. BC, brood chamber; SB, setal buds; GF, gonopore flap; AI, appendix interna; AM, appendix masculine; OVG, ovigerous setae; OVP, ovipositing setae.

6. The transcription patterns of Serpin, CREB, Caspase,

(Fink, 2018; Parsell and Lindquist, 1993).

, EF1a and IGFBP7 were compared to the expression patterns in the RNA-seq.

M. rosenbergii and Portunus pelagicus male reproductive-related protein (Mrr) were previously identified and characterized (Cao et al., 2006; Sroyraya et al., 2013). Mrr was revealed to play role in M. rosenbergii sperm fertilization and capacitation (Phoungpetchara et al., 2012). In this study, two copies of Mrr were found to be upregulated in the testis and downregulated during testis degeneration, but none were found to be upregulated during ovary development. These findings are consistent with a previous study in which Mrr expression was non-existent in female M. rosenbergii (Jiang et al., 2019). It was confirmed that Mrr was exclusively identified and expressed in males and that Mrr was not detected in sex-reversed males after AG ablation. Serine protease inhibitor (Serpin) regulates protease activity in inflammation, fertilization, coagulation, fibrinolysis, complement activity, apoptosis, and remodeling (Carrell et al., 1991; Ligoxygakis et al., 2003; Pak et al., 2004;

Travis and Salvesen, 1983). Serpin is also engaged in a variety of extracellular and intracellular processes, such as regulating sperm protease and decapacitation activity in Penaeus monodon (Chotwiwatthanakun et al., 2018). Serpin has been found in both male and female growing gonads (Charron et al., 2006). Serpin was found to be downregulated during testis degeneration and upregulated as ovary development progressed after AG ablation. Serpin is thought to play a significant role in female gonad development. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) is a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily and has a regulatory role in germ cell development, including germ cell proliferation and maintenance (Kawase et al., 2004; Narita et al., 2000; Shivdasani and Ingham, 2003). Furthermore, BMP7 is expressed in the gonads of both male and female mice (Ross et al., 2007). A previous study discovered BMP7 in the chicken ovary following sexual differentiation (Hoshino et al., 2005). BMP7 was upregulated in the

Fig.

TUBA3

7. The transcription pattern of selected genes in four developmental stages. (A)

(B)

(E)

Indication: S1, stage 1 (0 days after AG ablation); S2, stage 2 (14 days after AG ablation); S3, stage 3 (28 days after AG ablation); S4, stage 4 (42 days after AG ablation). Error bar represents standard error of the mean (SEM); the statistical difference among stages (P < 0.05) represented by different lowercase letters.

Fig.

Caspase

CREB (C) EF1a (D) Hsp70

IGFBP7 (F) MZT (G) Serpin (H) TUBA3

testis and during ovary development but downregulated during the testis degeneration process in this study. It has been proposed that BMP7 may play an important role in sex differentiation during gonadogenesis after AG ablation. The cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), on the other hand, is also involved in the testis-to-ovary transformation after AG ablation. CREB is a transcription factor superfamily member that influences gene expression by binding to the cAMP response element sequence (Auger, 2003). CREB may also help RNA polymerase reach the transcription initiation site faster, and CREB phosphorylation is essential for spermatogenesis in Sertoli cells (Fix et al., 2004; Meyer and Habener, 1993). In this study, androgenic gland ablation resulted in testis degeneration and spermatogenesis inhibition. Of note, the levels of CREB expression decreased from 14 days after androgenic gland ablation. As a result, it is speculated that CREB may play a significant role in spermatogenesis in M. rosenbergii Notably, after AG ablation, only a few genes were engaged in the testis-to-ovary transformation process. The majority of the identified genes were involved in cell proliferation, gonadogenesis, sperm protease, and decapacitation activity, enhanced stress tolerance, protein synthesis efficiency, and protein biogenesis. AG ablation results in the depletion of an important gene, IAG, which is essential for testis development, spermatogenesis, and maintenance of primary and secondary male sex characteristics (Ventura et al., 2012; Levy and Sagi, 2020). Depletion of IAG in M. rosenbergii causes testis degeneration and induces ovary transformation (Ventura et al., 2012). Hence, it is speculated that these genes each have their own functions and collaborate to regulate the process of organogenesis and maintain normal homeostasis after AG ablation.

Aside from the discovered differentially expressed genes, some signalling pathways that are notably involved in the mechanisms of testis to ovary transformation after AG ablation were identified. The primary signalling pathways discovered were Rap1, Hippo, PI3K, IL-17, oxytocin, thyroid hormone, apoptosis and ECM-receptor interaction. The Rap1 signalling pathway is present in all groups and is essential for platelet coagulation, angiogenesis, endothelial barrier function, and lymphocyte homing (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 2013; Pannekoek et al., 2014). In addition, Rap1 signalling promotes integrin-mediated adhesion, cell motility, cell polarization, and transendothelial migration downstream of the chemokine receptor (Boettner and Van Aelst, 2009; De Bruyn et al., 2002; McLeod et al., 2002). Furthermore, earlier research has shown that Rap1 is required for normal vascular development and function (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 2013). The Hippo signalling pathway is a conserved mechanism that is important in the regulation of organ growth and cell fate (Misra and Irvine, 2018). The Hippo pathway regulates organ growth and tissue size by restricting cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in excess cells (Halder and Johnson, 2011). Previous studies have shown that the Hippo pathway is crucial in tissue repair and regeneration in Drosophila by modulating cell density, cell–cell contact and cell stretching following tissue damage (Staley and Irvine, 2012). Generally, the PI3K signalling pathway is vital in mice for cellular activities and physiological regulation (SantanaSantana et al., 2021). Previous studies found that the PI3K signalling pathway regulates cellular activities such as oocyte maturation, growth, translation, proliferation, and transcription in Monopterus albus and Micropogonias undulatus (Chi et al., 2017; Datta et al., 1999; Pace and Thomas, 2005). Notably, in this study the PI3K signalling pathway was heavily implicated during ovarian development after AG ablation. The transformation of the testis to the ovary is a complex process that involves a series of signalling pathways. In this study, multiple signalling pathways were found to be substantially enriched throughout the testisto-ovary transformation process. These signalling pathways are thought to play a role in organ growth regulation, cell fate, oocyte maturation, translation, proliferation, as well as stimulating integrin-mediated adhesion, cell motility, and cell polarization during the testis-to-ovary transformation process. As a result, involvement of these signalling pathways may shape and govern the testis-to-ovary transformation process.

The oxytocin signalling pathway was also discovered to be involved in testis-to-ovary transformation after AG ablation. Oxytocin signalling is believed to play a physiological role in female puberty regulation, accelerating sexual maturity by increasing GnRH secretion (Bourguignon et al., 1992; Parent et al., 2008; Rettori et al., 1997; Yamanaka et al., 1999). Not only does oxytocin signalling play a role in sexual maturation, but it also participates in early development, neuron functionality and synapse formation (Bakos et al., 2018; Palanisamy et al., 2018; Ripamonti et al., 2017). Sexual maturation and synapse formation are both essential for the development of the ovary after testis degeneration. The thyroid hormone signalling pathway was found to have a diverse set of functions in growth and development, homeostasis maintenance, cell proliferation and differentiation. Thyroid hormone signalling has indeed been related to male and female reproduction, as well as testis and ovary development, according to some studies. Thyroid hormone signalling may influence testicular cell differentiation and proliferation, affecting testicular function and size in rats (Gao et al., 2014; La Vignera et al., 2017). Thyroid hormone signalling also impacts ovarian physiology and reproductive functional properties in adult rats (Meng et al., 2017). The thyroid signalling pathway was identified during testicular degeneration and ovary formation in this study. Sex-reversal is a complex process involving a series of multiple signalling and regulatory processes. The androgenic gland secretes IAG, which has a strong influence on testis development and spermatogenesis in decapod crustaceans. Thus, androgenic gland ablation inhibits IAG secretion, resulting in testicular degeneration and spermatogenesis arrest, which induces ovary development (Levy and Sagi, 2020). The androgenic gland ablated male will become a neofemale with a female phenotype after being femininized.

The androgenic gland not only affects primary and secondary male characteristics but is also responsible for maintaining the anatomical and sexual morphological features of male M. rosenbergii (Ventura et al., 2009). The transformation of male to female morphological features demonstrates that the male morphology feature had degraded following androgenic gland ablation. The brood chamber, setal buds on the ventral surface, ovigerous setae, and ovipositing setae in the second pleopod can all be seen in turn. These characteristics are only present in M. rosenbergii females. In general, the androgenic gland secretes insulin-like androgenic gland hormone (IAG) to maintain male morphology (Sagi et al., 1990; Tan et al., 2020). Due to the lack of an androgenic gland, IAG production ceased, resulting in the degradation of male physical features. These findings are congruent with those reported in an IAG silencing study, which found that silencing IAG induced sex-reversal and a shift in morphological characteristics from male to female (Tan et al., 2020). In addition, a previous study revealed that appendix masculine loss was observed after androgenic gland ablation (Nagamine et al., 1980). As a result, this confirms the significance of the androgenic gland in sustaining male morphological features.

In most cases, the feminization process occurs after androgenic gland ablation. The testis degenerates and gradually transforms into an ovary as the process of feminization progresses. In this study, degeneration of the testis was observed 14 days following androgenic gland ablation. The degeneration of the testis and the retardation of spermatogenesis are thought to be signs of feminization. The seminiferous lobules in the testis vanish 28 days after androgenic gland ablation and are replaced by previtellogenic oocytes and developing oocytes. Mature oocytes such as vitellogenic oocytes can be observed 42 days following androgenic ablation, and they resemble those found in normal females. The absence of IAG led to testis degeneration and induced ovary development. This phenomenon is comparable to that described by Ventura et al., in which male gonads and genital ducts were feminine and histologically resembled those in females (Ventura et al., 2012). Furthermore, previous research revealed that IAG silencing halted spermatogenesis (Tan et al., 2020). It has been suggested that removing the androgenic gland from male M. rosenbergii can induce sex-reversal and the transformation of the testis to the ovary (Ventura et al., 2012).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the first description of the involvement of genes, signalling pathways, and changes in the morphology and histology of the testis to the ovary after androgenic gland ablation. Hsp70, IGFBP7, Mar-Mrr, Serpin, TUBA3, CREB, EF1a, and BMP7 were identified as differentially expressed in gonad transcriptomic profiling in response to androgenic gland ablation. The Rap1, Hippo, PI3K, IL-17, oxytocin, thyroid hormone, apoptosis and ECM-receptor interaction signalling pathways were all enriched during the sex-reversal process, regulating cell proliferation and gonad development and maintains homeostasis. Sexual morphological features and histological changes after androgenic gland ablation indicated sex-reversal from male to neofemale. Taken together, these findings provide insight into the sex-reversal mechanism of M. rosenbergii after androgenic gland ablation. The findings of this study may aid in the future investigation of the sex-reversal mechanism in other decapod species and provide a new breeding and culture strategy for the M. rosenbergii aquaculture industry.

Ethics statement

The experimental techniques and animals used in this study were approved by the Scientific Ethic Committee of the Huazhong Agricultural University. The approval code of the Scientific Ethic Committee is HZAUFI-2019-012.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kianann Tan: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. Jiongying Yu: Methodology, Investigation, Visualization. Shouli Liao: Methodology. Jiarui Huang: Formal analysis. Meng Li: Investigation. Weimin Wang: Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 31501858.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738224.

References

Aflalo, E.D., Hoang, T.T.T., Nguyen, V.H., Lam, Q., Nguyen, D.M., Trinh, Q.S., Sagi, A., 2006. A novel two-step procedure for mass production of all-male populations of the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii Aquaculture 256, 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.01.035

Aflalo, E.D., Raju, D.V.S.N., Bommi, N.A., Verghese, J.T., Samraj, T.Y.C., Hulata, G., Sagi, A., 2012. Toward a sustainable production of genetically improved all-male prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii): evaluation of production traits and obtaining neo-females in three Indian strains. Aquaculture 338–341, 197–207. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2012.01.025

Auger, A.P., 2003. Sex differences in the developing brain: crossroads in the phosphorylation of cAMP response element binding protein. J. Neuroendocrinol. 15, 622–627. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01041.x.

Bakos, J., Srancikova, A., Havranek, T., Bacova, Z., 2018. Molecular mechanisms of oxytocin signaling at the synaptic connection. Neural Plast. 2018, 4864107. https:// doi.org/10.1155/2018/4864107

Barki, A., Karplus, I., Manor, R., Sagi, A., 2006. Intersexuality and behavior in crayfish: the de-masculinization effects of androgenic gland ablation. Horm. Behav. 50, 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.03.017

Boettner, B., Van Aelst, L., 2009. Control of cell adhesion dynamics by Rap1 signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 684–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2009.06.004

Bourguignon, J.P., Gerard, A., Gonzalez, M.L.A., Franchimont, P., 1992. Neuroendocrine mechanism of onset of puberty-sequential reduction in activity of inhibitory and facilitatory N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1736–1744. https:// doi.org/10.1172/JCI116047

Brokordt, K., P´ erez, H., Herrera, C., Gallardo, A., 2015. Reproduction reduces HSP70 expression capacity in Argopecten purpuratus scallops subject to hypoxia and heat stress. Aquat. Biol. 23, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.3354/ab00626

Cao, J.X., Yin, G.L., Yang, W.J., 2006. Identification of a novel male reproduction-related gene and its regulated expression patterns in the prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii Peptides 27, 728–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.09.004

Carrell, R., Evans, D., Stein, P., 1991. Mobile reactive Centre of serpins and the control of thrombosis. Nature 353, 576–578.

Charniaux-Cotton, H., 1954. D´ ecouverte chez un Crustac´ e Amphipode (Orchestia gammarella) d’une glande endocrine responsable de la diff´ erenciation des caract` eres sexuels primaires et secondaires m ˆ ales. Compt. Rendus Hebd. Seances l’Academie Sci. Paris 239, 780–782

Charniaux-Cotton, H., 1957. Croissance, regeneration et determinisme endocrinien des caracteres sexuels d’Orchestia gammarella Pallas (Crustace Amphipode). Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. Biol. Anim. 19, 411–559

Charniaux-Cotton, H., 1962. Androgenic gland of crustaceans. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1, 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-6480(62)90095-3

Charron, Y., Madani, R., Nef, S., Combepine, C., Govin, J., Khochbin, S., Vassalli, J.D., 2006. Expression of serpinb6 serpins in germ and somatic cells of mouse gonads. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 73, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.20385

Chi, W., Gao, Y., Hu, Q., Guo, W., Li, D., 2017. Genome-wide analysis of brain and gonad transcripts reveals changes of key sex reversal-related genes expression and signaling pathways in three stages of Monopterus albus PLoS One 12, 1–19. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0173974

Chotwiwatthanakun, C., Santimanawong, W., Sobhon, P., Wongtripop, S., Vanichviriyakit, R., 2018. Inhibitory effect of a reproductive-related serpin on sperm trypsin-like activity implicates its role in sperm maturation of Penaeus monodon Mol. Reprod. Dev. 85, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.22954

Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M., 2013. Distinct functions for Rap1 signaling in vascular morphogenesis and dysfunction. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 2350–2359. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.07.022

Cronin, L.E., 1947. Anatomy and histology of the male reproductive system of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun. J. Morphol. 81, 154–159.

Curtis, M.C., Jones, C., 1995. Observations on monosex culture of redclaw crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus von martens (Decapoda: Parastacidae) in earthen ponds. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 26, 154–159

Datta, S.R., Brunet, A., Greenberg, M.E., 1999. Cellular survival: a play in three akts. Genes Dev. 13, 2905–2927. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.13.22.2905

De Bruyn, K.M.T., Rangarajan, S., Reedquist, K.A., Figdor, C.G., Bost, J.L., 2002. The small GTPase Rap1 is required for Mn2+ - and antibody-induced LFA-1- and VLA-4mediated cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29468–29476. https://doi.org/10.1074/ jbc.M204990200

Fink, A.L., 2018. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol. Rev. 79, 425–449

Fix, C., Jordan, C., Cano, P., Walker, W.H., 2004. Testosterone activates mitogenactivated protein kinase and the cAMP response element binding protein transcription factor in Sertoli cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 10919–10924. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0404278101

Frydman, J., Nimmesgern, E., Ohtsuka, K., Hartl, F.U., 1994. Folding of nascent polypeptide chains in a high molecular mass assembly with molecular chaperones. Nature 370, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1038/370111a0

Gao, Y., Lee, W.M., Cheng, C.Y., 2014. Thyroid hormone function in the rat testis. Front. Endocrinol. 5, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2014.00188

Grabherr, M.G., Haas, B.J., Yassour, M., Levin, J.Z., Thompson, D.A., Amit, I., Regev, A., 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883

Guo, L., Zhao, Y., Yang, S., Zhang, H., Chen, F., 2014. An integrated analysis of miRNA, lncRNA, and mRNA expression profiles. Biomed. Res. Int. 345605 https://doi.org/ 10.1155/2014/345605

Halder, G., Johnson, R.L., 2011. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development 138, 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.045500

Hartl, F.U., Hayer-Hartl, M., 2002. Protein folding. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295, 1852–1858. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1068408

Hasanuzzaman, A.F.M., Siddiqui, M.N., Chisty, M.A.H., 2009. Optimum replacement of fishmeal with soybean meal in diet for Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De man 1879) cultured in low saline water. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 9, 17–22

Hoshino, A., Koide, M., Ono, T., Yasugi, S., 2005. Sex-specific and left-right asymmetric expression pattern of Bmp7 in the gonad of normal and sex-reversed chicken embryos. Develop. Growth Differ. 47, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440169x.2004.00783.x

Javid, B., MacAry, P.A., Lehner, P.J., 2007. Structure and function: heat shock proteins and adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 179, 2035–2040. https://doi.org/10.4049/ jimmunol.179.4.2035

Jiang, J., Yuan, X., Qiu, Q., Huang, G., Jiang, Q., Fu, P., Jiang, H., 2019. Comparative transcriptome analysis of gonads for the identification of sex-related genes in giant freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) using RNA sequencing. Genes 10, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10121035

Jin, S., Fu, H., Zhou, Q., Sun, S., Jiang, S., Xiong, Y., Zhang, W., 2013. Transcriptome analysis of androgenic gland for discovery of novel genes from the oriental river

prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense, using Illumina Hiseq 2000. PLoS One 8, e76840. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076840

Jung, H., Lyons, R.E., Dinh, H., Hurwood, D.A., McWilliam, S., Mather, P.B., 2011. Transcriptomics of a giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii): De Novo assembly, annotation and marker discovery. PLoS One 6, e27938. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0027938

Katakura, Y., 1989. Endocrine and genetic control of sex differentiation in the malacostracan crustacea. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 16, 177–181. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/07924259.1989.9672075

Kawase, E., Wong, M.D., Ding, B.C., Xie, T., 2004. Gbb/Bmp signaling is essential for maintaining germline stem cells and for repressing bam transcription in the Drosophila testis. Development 131, 1365–1375. https://doi.org/10.1242/ dev.01025

La Vignera, S., Vita, R., Condorelli, R.A., Mongioì, L.M., Presti, S., Benvenga, S., Calogero, A.E., 2017. Impact of thyroid disease on testicular function. Endocrine 58, 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1303-8

Langmead, B., Salzberg, S.L., 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923

Lawrence, C.S., 2004. All-male hybrid (Cherax albidus× Cherax rotundus) yabbies grow faster than mixed-sex (C. albidus× C. albidus) yabbies. Aquaculture 236, 211–220 Levy, T., Sagi, A., 2020. The ‘IAG-switch’ - a key controlling element in decapod crustacean sex differentiation. Front. Endocrionol. 11, 1–15

Levy, T., Rosen, O., Eilam, B., Azulay, D., Zohar, I., Aflalo, E.D., Sagi, A., 2017. All-female monosex culture in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii - a comparative large-scale field study. Aquaculture 479, 857–862

Levy, T., Rosen, O., Manor, R., Dotan, S., Azulay, D., Abramov, A., Sagi, A., 2019. Production of WW males lacking the masculine Z chromosome and mining the Macrobrachium rosenbergii genome for sex-chromosome. Sci. Rep. 9, 12408

Li, J., Ni, J., Li, J., Wang, C., Li, X., Wu, S., Yan, Q., 2014. Comparative study on gastrointestinal microbiota of eight fish species with different feeding habits. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117, 1750–1760. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.12663

Ligoxygakis, P., Roth, S., Reichhart, J.M., 2003. A serpin regulates dorsal-ventral axis formation in the Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 13, 2097–2102. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.062

Love, M.I., Huber, W., Anders, S., 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Ma, K., Qiu, G., Feng, J., Li, J., 2012. Transcriptome analysis of the oriental river prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense using 454 pyrosequencing for discovery of genes and markers. PLoS One 7, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039727

Malecha, S.R., Nevin, P.A., Ha, P., Barck, L.E., Lamadrid-Rose, Y., Masuno, S., Hedgecock, D., 1992. Sex-ratios and sex-determination in progeny from crosses of surgically sex-reversed freshwater prawns, macrobrachium rosenbergii Aquaculture 105, 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(92)90087-2

Manor, R., Aflalo, E.D., Segall, C., Weil, S., Azulay, D., Ventura, T., Sagi, A., 2004. Androgenic gland implantation promotes growth and inhibits vitellogenesis in cherax quadricarinatus females held in individual compartments. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 45, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/07924259.2004.9652584

McLeod, S.J., Li, A.H.Y., Lee, R.L., Burgess, A.E., Gold, M.R., 2002. The rap gtpases regulate b cell migration toward the chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL12): potential role for Rap2 in promoting B cell migration. J. Immunol. 169, 1365–1371. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1365

Meng, L., Rijntjes, E., Swarts, H.J., Keijer, J., Teerds, K.J., 2017. Prolonged hypothyroidism severely reduces ovarian follicular reserve in adult rats. J. Ovarian Res. 10 (1), 1–8

Meyer, T., Habener, J., 1993. Cyclic adenosine 3′ , 5′ -monophosphate response element binding protein (CREB) and related transcription-activating deoxyribonucleic acidbinding proteins. Endocr. Rev. 14, 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-40206754-9_1752

Misra, J.R., Irvine, K.D., 2018. The hippo signaling network and its biological functions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 52, 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-120417031621.

Mohanakumaran Nair, C., Salin, K.R., Raju, M.S., Sebastian, M., 2006. Economic analysis of monosex culture of giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii De man): a case study. Aquac. Res. 37, 949–954

Nagamine, C., Knight, A.W., Maggenti, A., Paxman, G., 1980. Masculinization of female Macrobrachium rosenbergii (de man) (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) by androgenic gland implantation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 41, 442–457 Narita, T., Saitoh, K., Kameda, T., Kuroiwa, A., Mizutani, M., Koike, C., Yasugi, S., 2000. BMPs are necessary for stomach gland formation in the chicken embryo: a study using virally induced BMP-2 and noggin expression. Development 127, 981–988. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.127.5.981

Pace, M.C., Thomas, P., 2005. Steroid-induced oocyte maturation in Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulatus) is dependent on activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Biol. Reprod. 73, 988–996. https://doi.org/ 10.1095/biolreprod.105.041400

Pak, S.C., Kumar, V., Tsu, C., Luke, C.J., Askew, Y.S., Askew, D.J., Silverman, G.A., 2004. SRP-2 is a cross-class inhibitor that participates in postembryonic development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: initial characterization of the clade L serpins. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15448–15459. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M400261200

Palanisamy, A., Kannappan, R., Xu, Z., Martino, A., Friese, M.B., Boyd, J.D., Culley, D.J., 2018. Oxytocin alters cell fate selection of rat neural progenitor cells in vitro. PLoS One 13, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191160

Pannekoek, W.J., Post, A., Bos, J.L., 2014. Rap1 signaling in endothelial barrier control. Cell Adhes. Migr. 8, 100–107. https://doi.org/10.4161/cam.27352

Parent, A.S., Rasier, G., Matagne, V., Lomniczi, A., Lebrethon, M.C., Gerard, A., Bourguignon, J.P., 2008. Oxytocin facilitates female sexual maturation through a glia-to-neuron signaling pathway. Endocrinology 149, 1358–1365. https://doi.org/ 10.1210/en.2007-1054

Parsell, D.A., Lindquist, S., 1993. The function of heat-shock proteins in stress tolerance: degradation and reactivation of damaged proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 27, 437–496. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.002253

Patel, R.K., Jain, M., 2012. NGS QC toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS One 7, e30619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0030619

Pertea, G., Huang, X., Liang, F., Antonescu, V., Sultana, R., Karamycheva, S., Quackenbush, J., 2003. TIGR gene indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics 19, 651–652. https:// doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034.

Phoungpetchara, I., Tinikul, Y., Poljaroen, J., Changklungmoa, N., Siangcham, T., Sroyraya, M., Sobhon, P., 2012. Expression of the male reproduction-related gene (mar-Mrr) in the spermatic duct of the giant freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii Cell Tissue Res. 348, 609–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-0121380-1

Qiao, H., Fu, H., Jin, S., Wu, Y., Jiang, S., Gong, Y., Xiong, Y., 2012. Constructing and random sequencing analysis of normalized cDNA library of testis tissue from oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). Comp. Biochem. Phys. D. 7, 268–276

Rettori, V., Canteros, G., Renoso, R., Gimeno, M., McCann, S.M., 1997. Oxytocin stimulates the release of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone from medial basal hypothalamic explants by releasing nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 2741–2744. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.6.2741

Ripamonti, S., Ambrozkiewicz, M.C., Guzzi, F., Gravati, M., Biella, G., Bormuth, I., Rhee, J.S., 2017. Transient oxytocin signaling primes the development and function of excitatory hippocampal neurons. Elife 6, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.7554/ eLife.22466

Ross, A., Munger, S., Capel, B., 2007. Bmp7 regulates germ cell proliferation in mouse fetal gonads. Sex. Dev. 1, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1159/000100034

Sagi, A., Aflalo, E.D., 2005. The androgenic gland and monosex culture of freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De man): a biotechnological perspective. Aquac. Res. 36, 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01238.x

Sagi, A., Cohen, D., 1990. Growth, maturation and progeny of sex-reversed Macrobrachium rosenbergii males. World Aquac. Rep. 21, 87–90

Sagi, A., Milner, Y., Cohen, D., 1988. Spermatogenesis and sperm storage in the testes of the behaviorally distinctive male morphotypes of Macrobrachium rosenbergii (Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Biol. Bull. 174, 330–336. https://doi.org/10.2307/ 1541958

Sagi, A., Cohen, D., Milner, Y., 1990. Effect of androgenic gland ablation on morphotypic differentiation and sexual characteristics of male freshwater prawns, Macrobrachium rosenbergii Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 77, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-6480 (90)90201-V

Sagi, A., Snir, E., Khalaila, I., 1997. Sexual differentiation in decapod crustaceans: role of the androgenic gland. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 31, 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 07924259.1997.9672563

Santana-Santana, M., Bayascas, J., Gimenez-Llort, L., 2021. Fine-tuning the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway intensity by sex and genotype-load: sex-dependent homozygotic threshold for somatic growth but feminization of anxious phenotype in middle-aged PDK1 K465E knock-in and heterozygous mice. Biomedicines 9, 747

Schirling, M., Triebskorn, R., Kohler, H.R., 2004. Variation in stress protein levels (hsp70 and hsp90) in relation to oocyte development in Gammarus fossarum (koch 1835). Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 45, 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 07924259.2004.9652585

Schmittgen, T.D., Livak, K.J., 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101

Shivdasani, A.A., Ingham, P.W., 2003. Regulation of stem cell maintenance and transit amplifying cell proliferation by TGF-β signaling in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Curr. Biol. 13, 2065–2072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.063

Siddiqui, A.Q., Al-Hafedh, Y.S., Al-Harbi, A.H., Ali, S., 1997. Effects of stocking density and monosex culture of freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii on growth and production in concrete tanks in Saudi Arabia. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 28, 106–112

Sroyraya, M., Hanna, P.J., Changklungmoa, N., Senarai, T., Siangcham, T., Tinikul, Y., Sobhon, P., 2013. Expression of the male reproduction-related gene in spermatic ducts of the blue swimming crab, Portunus pelagicus, and transfer of modified protein to the sperm acrosome. Microsc. Res. Tech. 76, 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jemt.22142

Staley, B.K., Irvine, K.D., 2012. Hippo signaling in Drosophila: recent advances and insights. Dev. Dyn. 241, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.22723

Tan, K., Zhou, M., Jiang, H., Jiang, D., Li, Y., Wang, W., 2020. siRNA-mediated MrIAG silencing induces sex reversal in Macrobrachium rosenbergii Mar. Biotechnol. 22, 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-020-09965-4

Thongbuakaew, T., Siangcham, T., Suwansa-Ard, S., Elizur, A., Cummins, S.F., Sobhon, P., Sretarugsa, P., 2016. Steroids and genes related to steroid biosynthesis in the female giant freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii Steroids 107, 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2016.01.006

Travis, J., Salvesen, G., 1983. Human plasma proteinase inhibitors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52, 655–701

Ventura, T., 2018. Monosex in aquaculture. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 65, 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92486-1_6

Ventura, T., Manor, R., Aflalo, E.D., Weil, S., Raviv, S., Glazer, L., Sagi, A., 2009. Temporal silencing of an androgenic gland-specific insulin-like gene affecting phenotypical gender differences and spermatogenesis. Endocrinology 150, 1278–1286. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2008-0906.

Ventura, T., Manor, R., Aflalo, E.D., Weil, S., Khalaila, I., Rosen, O., Sagi, A., 2011. Expression of an androgenic gland-specific insulin-like peptide during the course of prawn sexual and morphotypic differentiation. ISRN Endocrinol. 1-11 https://doi. org/10.5402/2011/476283

Ventura, T., Manor, R., Aflalo, E.D., Weil, S., Rosen, O., Sagi, A., 2012. Timing sexual differentiation: full functional sex reversal achieved through silencing of a single insulin-like gene in the prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii Biol. Reprod. 86, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.111.097261

Xie, C., Mao, X., Huang, J., Ding, Y., Wu, J., Dong, S., Wei, L., 2011. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr483

Yamanaka, C., Lebrethon, M.C., Vandersmissen, E., Gerard, A., Purnelle, G., Lemaitre, M., Bourguignon, J.P., 1999. Early prepubertal ontogeny of pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion: I. inhibitory autofeedback control through prolyl endopeptidase degradation of GnRH. Endocrinology 140, 4609–4615. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.140.10.6971

Young, M.D., Wakefield, M.J., Smyth, G.K., Oshlack, A., 2010. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14

Other documents randomly have different content

tarkatessa meitä silmin ja korvin, kuin missäkin huvinäytelmässä — ainoana toivomuksenamme halu päästä tuosta kiusallisesta tilanteesta? Minulle on sanottu: 'Käyttäydy vain aivan luontevasti.'

Tiedän että se on mahdotonta. Olen vakuutettu, että joudun mielenhämmennyksen valtaan, ja kenties esiintymisenikin siitä saa teeskennellyn sävyn. Teidän läsnäolonne tuntuu minusta sittenkin paljoa siedettävämmältä, kuin noiden uteliasten ihmisten, jotka tietäen asioista tulevat meitä katsomaan.

Minulle on puhuttu teistä paljonkin, ja teille epäilemättä samaten minusta. Mutta minusta tuntuu luultavalta että kahdenkeskinen keskustelu — sillä paremminhan juttelu muutoinkin käy kahden, kuin kolmen tai neljän kesken, — saattaisi meidät paremmin tuntemaan toisemme, kuin kaikki, mitä muut voivat meille toisistamme kertoa… Olen siksi miettinyt itsekseni: Miksi meille ei suoda tilaisuutta tuollaiseen keskusteluun? Mitä haittaa voisi noista vilpittömässä ja vakavassa tarkoituksessa puhutuista sanoista olla?

Ja nyt lausun siis teille ehdotukseni:

Huomenna, tiistaina, olen tavallisuuden mukaan iltapäivällä Louvressa. Tulkaa sinne minua tapaamaan. Kello kahden aikaan olen minä Darun porraskäytävässä Samotraken Voiton vieressä. Minulla on tummansininen puku, turkislakki ja pieni orvokkikimppu… Löydätte minut varsin helposti. Me juttelemme toverillisesti, pyrkien olemaan vilpittömiä niin puheisiimme kuin katseihimme ja äänensävyymme nähden. Tämä on sitten meidän todellinen tutustumistilaisuutemme. Kun sitten tuo toinen, virallinen tulee, emme enää olekaan vieraita toisillemme.

Tämä, mitä teille kirjoitan, on hirmuista… Älkää luulko, etten sitä käsitä. Kiltti isoäitini sanoo usein, että minä olen vain villi vesa,

jonkunmoinen rikkaruoho…

Älkää siksi arvostelko minua aivan siten kuin jotain toista nuorta tyttöä, jos olenkin erehtynyt ajatellessani, että kun isoäiti olisi valmis antamaan minut teille koko elämäniäkseni, niin voisin minä kunnioittaa teitä uskomalla itseni kahdeksi tunniksi teidän suojelukseenne. Mutta kenties olette hyvinkin loukkaantunut tästä ehdotuksestani? Kenties on myöskin vaikea lukea kirjeeni sanojen ja rivien väliltä, mitä tunteita mielessäni liikkuu… nimittäin mitä rehellisin pyrkimys vilpittömyyteen ja suoruuteen ja mitä valtavin halu onnen saavuttamiseen ja suomiseen…

En tahdo missään tapauksessa, sen kyllä käsitätte, teiltä vastausta kirjeeseeni. Jos loukkaannutte tästä kirjeestäni, niin älkää tulko… tekisitte väärin, jos tulisitte. Käsitän täysin, mitä poissaolonne merkitsee. Te ette ole minua ymmärtänyt… siinä kaikki. Eikä siitä koidu minulle suurtakaan mielipahaa, sillä koko avioliittotuuma on lähtöisin isoäidistäni. Emme peruuta jouluaaton tapaamista, se olisi liiaksi monimutkaista, ja meidät toimitettaisiin kumminkin jollakin muulla tavalla samaan seuraan. Te voitte sanoa kuvitelleenne minua isommaksi tai pienemmäksi, ja minä sanon että viiksienne väri ei minua miellytä… Ja niin on kunniamme pelastettu!

Luottaen hienotuntoisuuteenne ja kohteliaisuuteenne toivon teidän pitävän tämän salaisuuden omananne ja polttavan kirjeeni… riippumatta siitä, mitä siitä ajattelette.»

Kirjeen alla oli kirjoittajan täydellinen nimi:

»Marie-Denyse de Jolan.»

— No niin, herra herttua, huudahti Jumel, ja noissa sanoissa väräji hillitty närkästys.

Herttua de Groix asetti tuon sinisen paperin suurelle kirjoituspöydällensä, kirjeittensä ja asiapapereittensa joukkoon… Hymyily leikitteli hänen huulillansa.

— Mikä pikku veitikka! mumisi hän.

Jumel päästi kiukkunsa valloilleen.

— Ja ajatelkaa, että olin aikeissa mennä hänen kanssaan avioliittoon, silmät ummessa… tuollaisen nuoren tytön kanssa, joka ehdottaa minulle, että tapaisimme toisemme kahdenkesken, tytön kanssa, joka…

Herttua hymyili vieläkin.

— Kuulkaas, te kunnon Jumel, sanoi hän, — te arvostelette tuota asiaa väärin. Hän, joka on kirjoittanut teille nuo rohkeat sanat niin kauniille siniselle paperille, ei suinkaan ole vailla syvällisyyttä… Hän pystyy hiukan purevaan pilaan… eikä hän puolestaan halua mennä avioliittoon silmät ummessa. Mutta jollen tykkänään erehdy — ja se olisi harmillista, katsoen niihin suuriin edellytyksiin, joita minulla olisi elämän ja maailman oikeaan arvostelemiseen — on tuo nuori tyttö vilpittömin, puhdasmielisin, viattomin olento, mitä mies voi toivoa vaimoksensa… Jumel, tuo uhmamielinen kirje on viehkeä… ja teidän sijassanne minä, ystäväni…

Jumel oli kuin pilvistä pudonnut.

— Kuinka, herra herttua, te… te neuvoisitte minua menemään Louvreen?

Herttua vaikeni epäröiden.

— Rakas Jumel, jatkoi hän sitten, — yleensä on kartettava sellaisen neuvon antamista, jota neuvonanoja ei missään tapauksessa tahdo seurata… tai seuraa vastahakoisesti ja toivottua tulosta saavuttamatta. Sillä tavoin tuottaisi asianomaisille ainoastaan turhaa kiusaa. Neiti Jolan'in edellyttämä mahdollisuus on toteutunut, — te ette ole häntä ymmärtänyt, Jumel… On asioita, jotka ymmärtää heti, harkitsematta ja punnitsematta niitä, pelkästään tunteen välityksellä, tai joita ei ymmärrä koskaan. Mitä ikinä teille sanoisinkin, vallitsisi teidän mielessänne kumminkin epäilys, halveksiminen, mennessänne tuota lapsukaista tapaamaan. Vaivanne menisi hukkaan, tekonne olisi melkein rikollinen…

— Te hyväksytte siis aikomukseni olla menemättä tuohon kohtaamiseen?

— Niin teen.

Jumel hengitti helpommin.

— Minun olisi ollut vaikea, sanoi hän, — tehdä tuo päätökseni ilman teidän nimenomaista suostumustanne. Jouluna menen kyllä rouva Letourneurin luo, koska neiti de Jolan nähtävästi pitää sitä suotavana, ja kohteliaana miehenä suostun siihen, että viikseni ovat hänestä epämiellyttäviä…

Hän viivähti vielä, ja viitaten sitten sinertävään, köykäiseen kirjeeseen, jonka herttua oli pannut kirjoituspöydällensä, varovasti, sitä rypistämättä, kuin kallisarvoisen kukkasen, hän sanoi juhlallisesti:

— Herra herttua, tahdon polttaa tuon kirjeen teidän nähtenne.

Mutta herttua esti sen. Hän otti itse tuon sinisen paperin, ja lempeästi, kuin mielipahoissaan, hän jätti sen valkean valtaan, joka hyväilevästi kääräisi sen kokoon ja ahmaisi sen, jättämättä siitä mitään jäljelle.

— Tunnen vapautuneeni raskaasta taakasta, tunnusti Jumel. Avioliitto on vakava asia.

Mutta herttua ei näyttänyt tarkkaavan hänen sanojansa. Hänen katseensa seurasi uudelleen elpyneen valkean notkeita hyppyjä, ja hänen huulillansa oli sama hymyily kuin hänen lausuessaan äsken: »Mikä pikku veitikka!»

* * * * *

Maryse seisoo Darun porraskäytävässä, »Siivekkään voiton» edessä. Hän näyttää henkilöltä, joka on tykkänään vaipunut taidenautintoon. Mutta hän ajattelee: »Mahtaneeko hän tulla!» Ja hänen katseensa eivät näe ollenkaan tuota silvottua ihanneolentoa…

— … Mikä häikäisevän suurenmoinen teos! Tällä paikalla ei katse, ei ajatus voi kiintyä muuhun kuin siihen, eikö totta? lausuu miehen ääni hänen rinnallansa.

Ja järkytettynä Maryse huomaa, ettei hän ole ollenkaan varmasti luottanut herra Jumelin tuloon ennenkuin tänä hetkenä, jolloin hän tietää, että herra Jumel seisoo hänen rinnallansa.

Hän on saapunut… Mikä ihmeellinen seikkailu! Päätään kääntämättä Maryse antaa jonkun epämääräisen vastauksen.

Tuo miehekäs ääni kuuluu vakavalta… mutta siihen kätkeytyy salainen, vieno hymyilyn häive… Se puhuu kreikkalaisesta taiteesta, ehkäpä myöskin Demetrios Poliarketeestä. Maryse on kiitollinen tuosta juttelusta… jota hän sentään ei kuuntele. Hän ei katsele enää