1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mastroianni, George R., author.

Title: Of mind and murder : toward a more comprehensive psychology of the Holocaust / George R. Mastroianni.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018009285 | ISBN 9780190638238 (jacketed hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Psychological aspects.

Classification: LCC D804.3 .M3735 2018 | DDC 940.53/18019—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018009285

The views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For My Teachers:

Daniel N. Robinson

Robert P. Wease

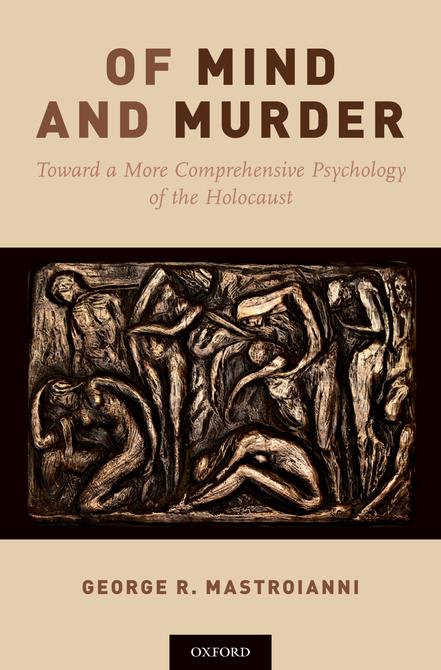

ABOUT THE COVER PHOTO

This plaque originally hung in the entryway of Lela Karayanni’s house on Limnou Street in Athens, Greece. Lela Karayanni was a leader of the Bouboulina anti-Nazi Resistance group. This group operated for three years gathering and passing on intelligence to the Allies, helping vulnerable people escape the Nazis, and organizing acts of resistance against the Nazi occupiers. Lela Karayanni was arrested by the Nazis on August 11, 1944, and was subjected to days of torture, though she revealed nothing to her captors. She was shot along with seventy-one other members of the Resistance on September 8, 1944, in the forest of Daphni. She reportedly led her compatriots in the Zallogos, a Greek dance of defiance, as they were executed.* On September 13, 2011, Lela Karayanni was honored as Righteous Among Nations by Yad Vashem for her heroism in saving the family of Solomon Cohen. The plaque, by an unknown artist, probably dates to the construction of the house on Limnou Street, sometime in the 1920s. The plaque is now in the possession of Iason Carayannis, Lela’s grandson, who generously made it available for this cover photograph.

NOTE

* http://www.drgeorgepc.com/LelaCarayannisTribute.html

Acknowledgments xi

Human Nature and the Peace xiii

Introduction xix

1. What Was the Holocaust? 1

2. The Holocaust: A Brief History of Psychological Explanation 35

3. Matters of Method: Issues and Problems in the Psychological Study of the Holocaust 71

4. Clinical/Abnormal Perspectives 105

5. Personality 137

6. Learning and Conditioning 165

7. Cognition and Memory 197

8. Age and Development 231

9. Social Psychology 263

10. In the Aftermath 303

11. Psychology, Context, and the Risk of Genocide: Japanese Evacuation and Confinement 333

12. The Psychology of the Holocaust in Perspective 367

Index 401

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I appreciate the support of the United States Air Force Academy, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership in helping make this book possible.

I am deeply indebted to Dagmar Herzog, Irina Goldenberg, Connor Sebestyen, Greg Robinson, Karen McComb, and anonymous reviewers at Oxford University Press for their review of all or parts of earlier versions of this manuscript and their immensely helpful comments and criticisms. Their collegiality and wisdom have improved the book greatly: defects remain solely my responsibility. Abby Gross, Courtney McCarroll and Katie Pratt at Oxford University Press have been wonderfully patient and professional with me, and their unparalleled competence and unfailing courtesy are deeply appreciated.

I am also grateful to my wife Kathy, and my daughters Katie and Corey for the patience and forbearance through what has been many years of sometimes difficult work on this project.

HUMAN NATURE AND THE PEACE

GORDON W. ALLPORT ■

On April 5, 1945, there was released to the press a statement signed by 2,038 American psychologists. This statement had its origin during the summer of 1944 in informal conversations among psychologists, about twentyfive of whom contributed to its formulation. Although at no time was the statement officially sponsored by any psychological organization, the funds for printing and mailing were supplied by the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI), and the recipients of the statement were the 3,803 members and associates of the American Psychological Association listed in its 1944 Yearbook. The covering letter soliciting endorsements was signed by the following group of psychologists: G. W. Allport, R. S. Crutchfield, H. B. English, Edna Heidbreder, E. R. Hilgard, O. Klineberg, R. Likert, M. A. May, O. H. Mowrer, G. Murphy, C. C. Pratt, V. S. Taylor, and E. C. Tolman.

While many mail solicitations bring only a 25 percent response and while many psychologists were abroad in war service and hard to reach, the result of this call brought more than a 50 percent response. Among those replying more than 99 percent subscribed to the statement. Included among the signers are 350 clinical psychologists, 230 industrial psychologists, approximately 250 in other fields of applied psychology, and approximately 300 in the armed services. The remainder were in

universities and colleges. Minor comments and suggestions were received from ninety-two individuals. There were only thirteen refusals to sign.

Besides being printed in newspapers, the statement was sent to 535 representatives and senators in the United States Congress and to many organizations and individuals prominently concerned with peace-planning and international cooperation. The statement likewise is printed in the recent Yearbook of the SPSSI, Human Nature and Enduring Peace, edited by Gardner Murphy.

The full text of the statement follows:

HUMAN NATURE AND THE PEACE: A STATEMENT BY PSYCHOLOGISTS

Humanity’s demand for lasting peace leads us as students of human nature to assert ten pertinent and basic principles which should be considered in planning the peace. Neglect of them may breed new wars, no matter how well-intentioned our political leaders may be.

1. War can be avoided: War is not born in men; it is built into men.

No race, nation, or social group is inevitably warlike. The frustrations and conflicting interests which lie at the root of aggressive wars can be reduced and re-directed by social engineering. Men can realize their ambitions within the framework of human cooperation and can direct their aggressions against those natural obstacles that thwart them in the attainment of their goals.

2. In planning for permanent peace, the coming generation should be the primary focus of attention.

Children are plastic; they will readily accept symbols of unity and an international way of thinking in which imperialism, prejudice, insecurity, and ignorance are minimized. In appealing to older people,

chief stress should be laid upon economic, political, and educational plans that are appropriate to a new generation, for older people, as a rule, desire above all else, better conditions and opportunities for their children.

3. Racial, national, and group hatreds can, to a considerable degree, be controlled.

Through education and experience people can learn that their prejudiced ideas about the English, the Russians, the Japanese, Catholics, Jews, Negroes, are misleading or altogether false. They can learn that members of one racial, national, or cultural group are basically similar to those of other groups, and have similar problems, hopes, aspirations, and needs. Prejudice is a matter of attitudes, and attitudes are to a considerable extent a matter of training and information.

4. Condescension toward “inferior” groups destroys our chance for a lasting peace.

The white man must be freed of his concept of the “white man’s burden.” The English-speaking peoples are only a tenth of the world’s population; those of white skin only a third. The great dark-skinned populations of Asia and Africa, which are already moving toward a greater independence in their own affairs, hold the ultimate key to a stable peace. The time has come for a more equal participation of all branches of the human family in a plan for collective security.

5. Liberated and enemy peoples must participate in planning their own destiny.

Complete outside authority imposed on liberated and enemy peoples without any participation by them will not be accepted and will lead only to further disruptions of the peace. The common people of all countries must not only feel that their political and economic future holds genuine

hope for themselves and for their children, but must also feel that they themselves have the responsibility for its achievement.

6. The confusion of defeated people will [sic]call for clarity and consistency in the application of rewards and punishments.

Reconstruction will not be possible so long as the German and Japanese people are confused as to their status. A clear-cut and easily understood definition of war guilt is essential. Consistent severity toward those who are judged guilty, and consistent official friendliness toward democratic elements, is a necessary policy.

7. If properly administered, relief and rehabilitation can lead to selfreliance and cooperation; if improperly, to resentment and hatred.

Unless liberated people (and enemy people) are given an opportunity to work in a self-respecting manner for the food and relief they receive, they are likely to harbor bitterness and resentment, since our bounty will be regarded by them as unearned charity, dollar imperialism, or bribery. No people can long tolerate such injuries to self-respect.

8. The root-desires of the common people of all lands are the safest guide to framing a peace.

Disrespect for the common man is characteristic of fascism and of all forms of tyranny. The man in the street does not claim to understand the complexities of economics and politics, but he is clear as to the general directions in which he wishes to progress. His will can be studied (by adaptations of the public opinion poll). His expressed aspirations should even now be a major guide to policy.

9. The trend of human relationships is toward ever wider units of collective security.

From the caveman to the twentieth century, human beings have formed larger and larger working and living groups. Families merged into clans, clans into states, and states into nations. The United States are not 48 threats to each other’s safety; they work together. At the present moment the majority of our people regard the time as ripe for regional and world organization, and believe that the initiative should be taken by the United States of America.

10. Commitments now may prevent postwar apathy and reaction.

Unless binding commitments are made and initial steps taken now, people may have a tendency after the war to turn away from international problems and to become preoccupied once again with narrower interests. This regression to a new postwar provincialism would breed the conditions for a new world war. Now is the time to prevent this backward step, and to assert through binding action that increased unity among the people of the world is the goal we intend to attain.

INTRODUCTION

The passage of seventy-five years has not diminished the power of the Holocaust to challenge our understanding of ourselves and others. Academic and scholarly works on the topic continue to appear in great number, as do artistic, literary, and cinematic contributions to our thinking about what remains, in many ways, the paradigmatic genocide. Psychologists have been engaged in explaining and understanding the Holocaust from the very beginning and continue to make important contributions. And yet there remain large gaps in our psychological understanding of the Holocaust.

From the early 1960s until quite recently, psychological scholarship on the Holocaust was dominated by Stanley Milgram’s situationist approach to obedience. In the 1990s, though, two books were published that would ignite controversy and discussion and would ultimately have the effect of causing a reconsideration of the centrality of obedience in understanding the psychology of the Holocaust. Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland1 and Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust2 both contain the word “ordinary” in their titles. This word has struck a chord with many interested in the Holocaust and has given new life to some old questions: How could people do these things to other people? Was the Holocaust the work of ordinary people, or were the perpetrators sick, insane, or monstrously evil? These questions have been such a persistent feature of psychological (and other) discussions of

the Holocaust in part because of the implications they seem to have for the rest of “us.” By placing the blame on a few disturbed or evil people we run the risk of sweeping the Holocaust, and the propensity for mass violence more generally, under a kind of psychological rug, negating the need for careful self-reflection. To see the Holocaust as the work of ordinary people, though, may appear to help us acknowledge our own potential for such behavior, to more honestly engage the continuing potential for mass violence, and to offer more realistic hopes for preventing such violence in the future.

HOW COULD PEOPLE DO THESE THINGS?

How could people do these things? The answer that seemed to resonate with the public in the years after the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg was that there were a few insane or evil men at the top but that most of those who had perpetrated the Holocaust were merely following orders, absent any real ideological commitment or anti-Semitic prejudice. The public was seemingly content to follow the lead of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who (proposing the establishment of a United Nations Commission on War Crimes to deal with atrocities in Europe) said on October 7, 1942:

The number of persons eventually found guilty will undoubtedly be extremely small compared to the total enemy populations. It is not the intention of this Government or of the Governments associated with us to resort to mass reprisals. It is our intention that just and sure punishment shall be meted out to the ringleaders responsible for the organized murder of thousands of innocent persons and the commission of atrocities which have violated every tenet of the Christian faith.3

This statement was made during the most intense period of killing: some 80% of those who would die in what we call the Holocaust were killed

between early 1942 and the summer of 1943. Roosevelt could not have known then what has taken many years of research and study to establish: the full story of the Holocaust, still being written, is much more than a story of a few ringleaders and a population of mostly good citizens. Roosevelt’s view of the civilian populations of Europe may simply have reflected his naïve understanding of what was happening. The focus on “ringleaders” did, however, lay the groundwork for a speedy and limited judicial response at the end of the war that would help make possible a rapid reconstruction and rehabilitation of European countries as America confronted the prospect of Soviet domination of Europe. It is worth noting that Roosevelt’s view of the Japanese population was rather less charitable than his view of European populations, as a few months earlier he had signed an executive order that would be used to facilitate the involuntary confinement of some 110,000 Japanese Americans solely on the basis of their race, defined as Japanese “ancestry.” These 110,000 were not a small subset of the population of Japanese Americans, but the entire population of Japanese Americans living in the exclusion zones established by the military.

Milgram’s obedience studies had given the ringleader theory, for lack of a better term, new life by the mid-1970s. A major difficulty with the ringleader approach had always been defining the mechanisms by which so many could be induced to behave so badly by so few. Until Milgram, there was no general agreement on the mechanism by which the ringleaders were able to get the ordinary masses to carry out their destructive and murderous aims. Insanity, peculiar German child-rearing leading to the development of authoritarian personalities, particular aspects of German history and culture, and a particularly German cultural obsession with obedience were all explanations that had been tried and found wanting.

THE SITUATIONIST ACCOUNT

Milgram’s scientific demonstration of obedience in the laboratory, coupled with Hannah Arendt’s interpretation of the Eichmann trial as illustrating

“the banality of evil,” seemed to offer a simple and persuasive solution: the power of “the situation” could irresistibly transform good people into bad people. Phillip Zimbardo, Milgram’s high-school classmate, seemingly confirmed this power a decade later in his Stanford Prison Experiment. Both Milgram and Zimbardo explicitly connected their situationist account of behavior to the Holocaust. This account came to dominate psychological thinking about the Holocaust and also became immensely popular with the lay public.

That this viewpoint resonated so powerfully with American psychologists and the public is perhaps at least partly explicable in terms of the changes then taking place in American culture. Consider some of the historic events that occurred in the United States during the decade bookended by Milgram’s obedience studies and Zimbardo’s prison study: the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), the assassination of John F. Kennedy (1963), the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Tonkin Gulf affair and the escalation of the Vietnam War (1964), the Voting Rights Act (1965), the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy (1968), the assassination of Martin Luther King (1968), the My Lai Massacre (1968), the Charles Manson murders (1968), worldwide summertime protests and riots (1968), Woodstock (1969), the shootings at Kent State (1970), the US invasion of Cambodia (1970), and the Watergate break-in (1972).

These developments had a monumental impact on American society, and especially on the academy, as draft resistance and protests were centered on many college campuses. The breakdown of trust in fundamental institutions and the polarization of American society led to dictums like Timothy Leary’s “Question Authority”4 and Jack Weinberg’s “Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30,”5 both of which would make some sense as reactions to the Milgram experiments. An image of corporations, institutions, and bureaucracies as malevolent entities manipulating the innocent into doing their evil bidding coincided with growing unease at the effects of modernity itself, as the world faced the possibility of nuclear devastation. These images fit the tenor of the political times and also dovetailed nicely with the social psychology of Milgram and Zimbardo.

The task of reshaping society after generations of institutional racism and segregation lay ahead. The pernicious consequences of viewing human nature in terms which too strongly emphasized “nature” over “nurture” had been exposed in the most horrific way possible during the Holocaust. The hope that lay ahead for America was, in many ways, seemingly to be found in the adoption of the opposite approach from that taken by the Nazis in their attempt to reshape German society. The Nazis focused on the “nature” side, the biological and genetic determinants of human nature, and attempted to “improve” German society by changing the genetic composition of the population through “positive” measures, such as promotion of reproduction among the genetically fit, and “negative” measures, including sterilization, euthanasia, and, eventually, extermination.

In America, the goal was to improve society by leaving the population as it was and changing the environment: the assumption was that all could and would benefit from improvements in housing, education, nutrition, and health care and that, with the achievement of these improvements, the legacies of inequality would gradually disappear. The Milgram and Zimbardo studies, showcasing extreme examples of the role the environment can play in affecting human behavior, were thus in synchrony with both the anti-authoritarian impulses of the Vietnam era and the focus on external, environmental, situational factors as the means by which civil society could be reconstructed in a truly egalitarian direction.

While Milgram’s work would eventually come to be seen (though not in these terms) as providing a sound basis for the ringleader theory, Milgram himself did not spend much time talking about the ringleaders, preferring to focus on the influenced rather than the influencers. Gertrude Stein, speaking about obedience in 1946, saw both sides of the equation: she suggested that World War II was the direct result of “bad men” using uniquely obedient peoples (Germans and Japanese) to accomplish evil ends. Phillip Zimbardo, like Gertrude Stein, also focuses on the role of individual authority figures (bad men) in creating situations that then engage basic human psychological mechanisms (obedience, conformity) to make good people do bad things, but Zimbardo no longer limits this assessment to only Germans and Japanese: he applies it to all of us.

Zimbardo frequently uses the metaphor of the “bad barrel” as opposed to “bad apples” as an explanatory framework. Blaming a few low-level individuals for bad behavior in corporate or military environments is, on this account, a species of victim-blaming, as the individuals are only responding naturally and involuntarily to the conditions created by the “system” and those in charge of it. Blaming a few bad apples, such as the soldiers who abused Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib, is nothing more than a dodge employed by the “system” (the “System” or “Systems Managers” in Zimbardo’s terminology) to protect those who are really responsible, the high officials whose actions and policies created the situation to which the soldiers then responded.

The idea that most of the blame for the Holocaust lay mainly with the “ringleaders” has been remarkably persistent in America and in Europe: in 1995, when an exhibition in Germany suggested that average German soldiers during the Nazi years were far more directly and willingly involved in atrocities in the East than they cared to admit, widespread anger and demonstrations resulted. But since the 1990s, long-standing impressions and assumptions about the role played by ordinary German soldiers (and other ordinary Germans) have had to undergo substantial revision in the face of new scholarship. The situationist perspective has increasingly been seen as constituting at best a limited explanation of the behavior of some Holocaust perpetrators. This perspective has never really addressed the origins of the behavior of those on whom the blame actually gets placed (those in authority issuing the orders) or, indeed, of many others.

A NEGLECTED HISTORY

Psychology, then, does not seem to have offered a complete answer to the questions that most of us have about the Holocaust: How could people do these things to other people? Was the Holocaust the work of normal, average people, or were the perpetrators exceptional in some way? The hegemony of the situationist interpretation of the Holocaust

as a set of events to be understood mainly through the lens of obedience, and the ease with which serious thinking about the interior lives of ordinary Germans or Nazi killers could be discouraged by invocation of the “fundamental attribution error,” have perhaps deflected our attention from a more complete history of psychological thinking about the Holocaust.

As it happens, though, even before Milgram there was a substantial, vibrant, and diverse body of psychological scholarship on the Holocaust dating back to the years immediately following the war, when awareness of the Holocaust as we now understand it was just emerging. There is also a substantial body of scholarship on the rise of Hitler and the Nazis, some of which antedated not just the Holocaust but the war itself, and even Hitler’s rise to power. Much of this work directly addressed the basic questions about human nature posed by the Holocaust, with which we continue to grapple.

One purpose of this book is to resurrect and perhaps rehabilitate some psychological approaches to understanding the Holocaust that have been largely forgotten, or remembered only as something to be dismissed at second hand as hopelessly outdated. Gustave Gilbert and Douglas Kelley, for example, who were both present at Nuremberg and wrote about the major war criminals, also thought deeply about the origins of Nazism and the psychological mechanisms that had made the Holocaust possible. These men are often mentioned but rarely covered at any length in discussions of the Holocaust in psychology: they seem to be mainly treated as a kind of footnote to be acknowledged before moving on to the really serious material. This is a shame, as both Gilbert’s and Kelley’s experiences were very nearly unique as psychologists interested in understanding what had happened: they lived in occupied Germany immediately after the Nazi surrender, interacted with a wide variety of people, and had access to the men deemed most important by the Allied judicial authorities. They were the last psychologists to speak to the eleven who died at Nuremberg (ten who were executed and Goering, who committed suicide) and saw their role as one of great psychological and historical significance: it was they who would have this unique experience and they