Contributors

Daniela S. Allende, MD, MBA

Co-Section Head, Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Pathology

Vice Chair of Research

The Cleveland Clinic;

Associate Professor of Pathology

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Liver; Liver Neoplasms, and Pathology of the Liver; and Small Bowel and Pancreas Transplantation

Lodewjk A.A. Brosens, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Pathology

Gastrointestinal and Endocrine Pathology

UMC Utrecht, Netherlands

Non-Neoplastic and Neoplastic Pathology of the Pancreas

Michael Cruise, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Pathology

Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Pathology Staff

Informatic Systems Medical Director

Department of Pathology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Gastrointestinal Lymphoma

James Conner, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathobiology

University of Toronto Toronto, Canada

Pathology of the Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Bile Ducts

Leona Doyle, MD

Associate Professor of Pathology

Harvard Medical School

Department of Pathology

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

Gastrointestinal Mesenchymal Tumors

Ilyssa O. Gordon, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Pathology

Co-Section Head, Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Pathology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Esophagus

Catherine Hagen, MD

Consultant, Division of Anatomic Pathology

Assistant Professor of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota

Tumors of the Esophagus

Bence Kövari, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor Department of Pathology

University of Szeged

Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical School, Hungary Department of Pathology

H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute

Tampa, FL

Epithelial Polyps and Neoplasms of the Stomach

Gregory Y. Lauwers, MD, PhD

Professor of Pathology Moffit Cancer Center

Tampa, Florida

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Stomach and Epithelial Polyps and Neoplasms of the Stomach

Mikhail Lisovsky, MD

Associate Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth Department of Pathology

Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center

Lebanon, New Hampshire

Pathology of the Anal Canal

Mari Mino-Kenudson, MD

Professor of Pathology

Pulmonary Pathology Director

Gastrointestinal Pathology Staff

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

Non-Neoplastic and Neoplastic Pathology of the Pancreas

Reetesh K. Pai, MD

Professor of Pathology

Anatomic Pathology Director

UPMC Presbyterian

Gastrointestinal Pathology Center of Excellence Director Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Neoplasms of the Small Bowel

Rish K. Pai, MD, PhD

Professor of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology

Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology

Consultant

Mayo Clinic Arizona Phoenix, Arizona

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Colon

Nicole C. Panarelli, MD

Associate Professor of Pathology

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Section Head, Gastrointestinal Pathology

Director of Anatomic Pathology Research

Montefiore Medical Center

New York, New York

Infectious Diseases of the Gastrointestinal Tract

David Papke, MD, PhD

Instructor in Pathology

Department of Pathology

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

Gastrointestinal Mesenchymal Tumors

Deepa T. Patil, MBBS, MD

Associate Professor of Pathology

Harvard Medical School

Pathologist

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

Non-Neoplastic and Inflammatory Disorders of the Small Bowel; Non-Neoplastic and Neoplastic Disorders of the Appendix; Epithelial Neoplasms of the Colorectum, Molecular Testing of Colorectal Carcinoma; and Pathology of the Liver, Small Bowel, and Pancreas Transplantation

Scott Robertson, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor of Pathology

Research Analytics Medical Director

Gastrointestinal Pathology Staff

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Non-Neoplastic and Inflammatory Disorders of the Small Bowel

Safia Nawazish Salaria, MD, MMHC

Section Chief and Fellowship Director

Division of GI, Liver and Pancreas Pathology

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Officer

Associate Professor, Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Nashville, Tennessee

Liver Neoplasms

Amitabh Srivastava, MD

Member, Memorial Hospital

Attending, Memorial Hospital for Cancer and Allied Diseases

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

New York, New York

Tumors of the Esophagus, Gastrointestinal Polyposis Syndromes, Pathology of the Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Bile Ducts, and Liver Neoplasms

Sarah E. Umetsu, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Pathology

University of California San Francisco

San Francisco, California

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Stomach

Kwun Wah Wen, MD, PhD

Associate Professor Department of Pathology

University of California San Francisco

San Francisco, California

Epithelial Polyps and Neoplasms of the Stomach

Laura D. Wood, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Pathology & Oncology

Department of Pathology

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Non-Neoplastic and Neoplastic Pathology of the Pancreas

Lisa M. Yerian, MD

Chief Improvement Officer

Associate Professor of Pathology

Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Pathology Staff

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Liver and Pathology of the Liver, Small Bowel, and Pancreas Transplantation

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Esophagus

■ Ilyssa O. Gordon, MD, PhD

The esophagus is designed to simply serve as a conduit to carry food into the stomach. It does not have any digestive, endocrine, or metabolic role. As a result, most non-neoplastic disorders affecting the esophagus are a result of mechanical, chemical, or immune-mediated injury to the relatively resilient nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa. These disorders can be broadly categorized into inflammatory, infectious, congenital and acquired structural abnormalities; motility, traumatic, and vascular disorders; and those associated with systemic diseases. Inflammatory disorders and infections are by far the most common disorders encountered in daily practice. The remainder of the disorders usually require a combination of clinical, radiographic, and endoscopic examinations for accurate diagnosis, and histologic examination often does not yield specific diagnostic findings.

This chapter is organized based on broad categories of non-neoplastic esophageal disorders. It is, however, essential to note that inflammatory disorders are a manifestation of several common types of stimuli, such as reflux, infections, drugs, and systemic disorders, among others. Therefore, based on the predominant inflammatory cell, these disorders can also be categorized into neutrophil-rich esophagitis, eosinophil-rich, lymphocyte-rich, and paucicellular esophagitis. Neutrophil-rich disorders are most commonly caused by reflux disease and infections (see Chapter 9 for details). Eosinophilrich disorders include eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), reflux, parasitic infections, Crohn’s disease, drug hypersensitivity, hypereosinophilic syndrome, celiac disease, vasculitis, and collagen vascular disorders. Lymphocytes are a predominant component of inflammation in patients with chronic reflux, drugs or medications, Crohn’s disease (pediatric), achalasia or motility disorders, autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], common variable immunodeficiency [CVID]), celiac disease, and dermatologic conditions. Last, some conditions, such as corrosive injury, sloughing esophagitis, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), CVID, and certain medications may not show a significant inflammatory component and thus manifest as paucicellular esophagitis.

■ ESOPHAGITIS

Inflammatory DI sor D ers

Reflux esophagitis

Reflux esophagitis, also known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), is one of the most common non-neoplastic disorders of the esophagus. Its prevalence ranges between 5% and 22% and depends on the geographic location. The reported prevalence of GERD is 22% in the United States. Pregnant women have a higher incidence. The pathophysiologic hallmark of reflux is the presence of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) dysfunction. Nonerosive reflux disease (NERD) is defined as patients with classic GERD symptoms but no evidence of mucosal injury on endoscopy.

CliniCal featu R es

Reflux occurs at all ages and in both genders. Typical symptoms include heartburn and regurgitation. Other uncommon or atypical symptoms include dysphagia, angina-like chest pain, chronic hoarseness or cough, asthmatic episodes, and protracted hiccups. If left untreated, reflux may lead to complications such as erosive esophagitis, strictures, Barrett’s esophagus (BE), and malignancy. Importantly, a number of individuals with reflux do not manifest symptoms, although the risk for adenocarcinoma arising from BE remains. GERD may be a secondary complication of other disorders affecting the esophagus, such as systemic sclerosis.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a clinical diagnosis and is often classified as erosive or nonerosive based on endoscopic or pathologic findings. The current recommendations from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy do not support using endoscopy and biopsy to diagnose typical GERD but rather to exclude other pathologies in complicated or refractory cases. Furthermore, the degree of histologic damage may not correlate with clinical symptoms, and histologic findings alone have a low sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing GERD.

Patholog I c features

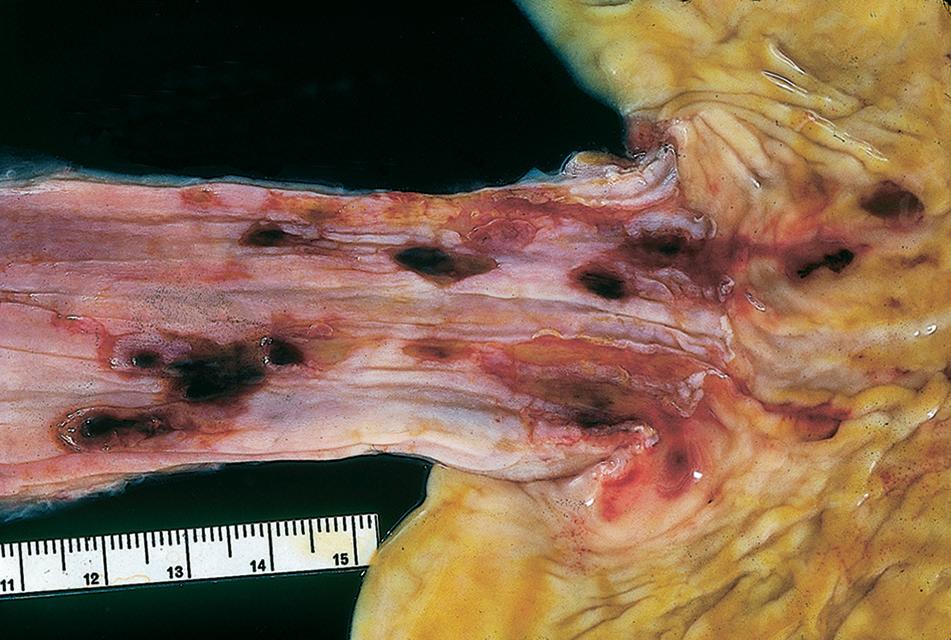

gRoss findings

Endoscopic examination in cases of reflux is variable, depending on the severity and the chronicity of the symptoms. Some patients may have erythema, erosions, or ulceration. Deep ulcerations, bleeding, and peptic strictures are seen in severe cases (Fig. 1.1). Patients with NERD by definition have normal white-light endoscopy, although high-definition endoscopy or narrow-band imaging may reveal subtle changes, including prominent vascularity and irregularity of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), creating a group of patients with so-called minimal change esophagitis.

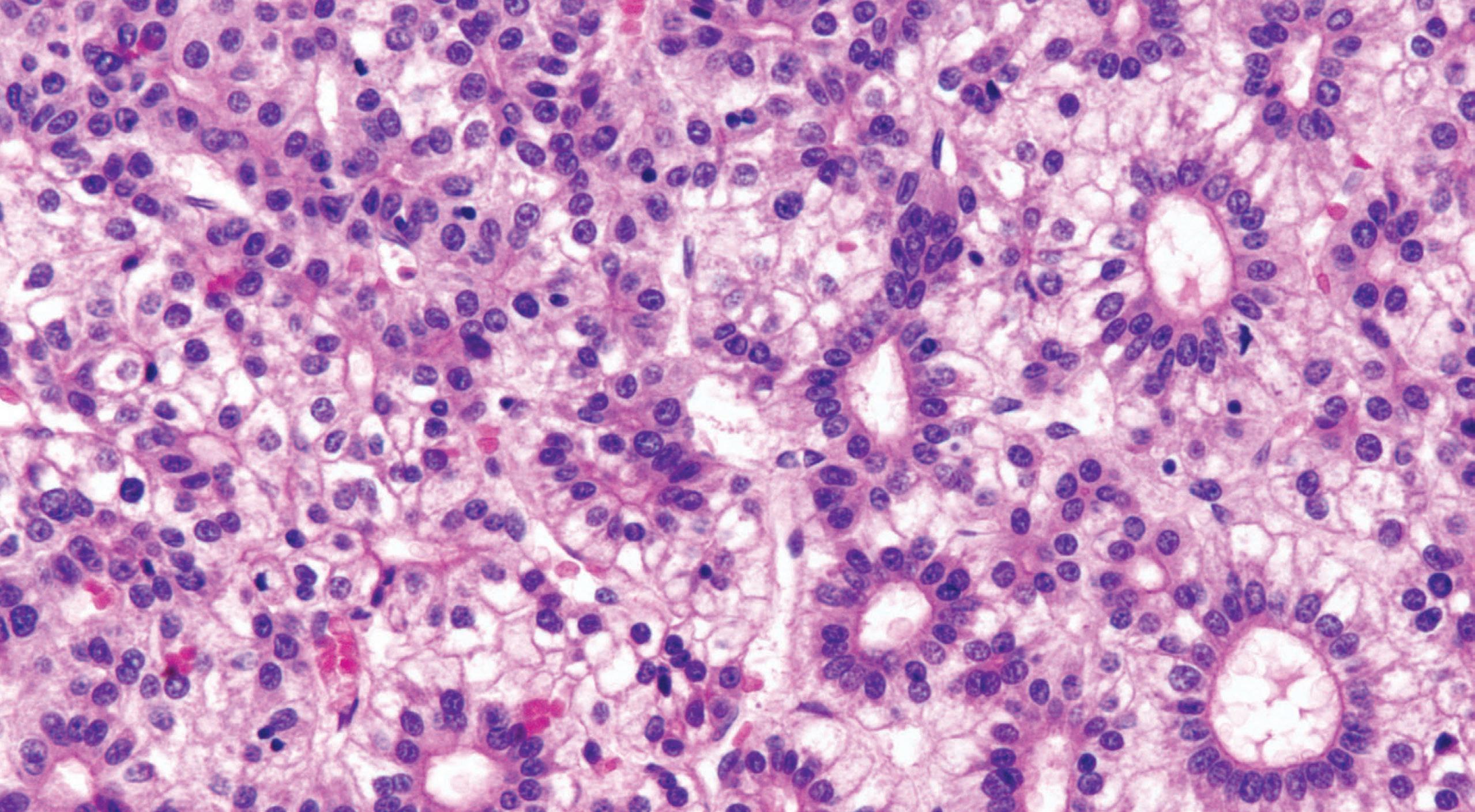

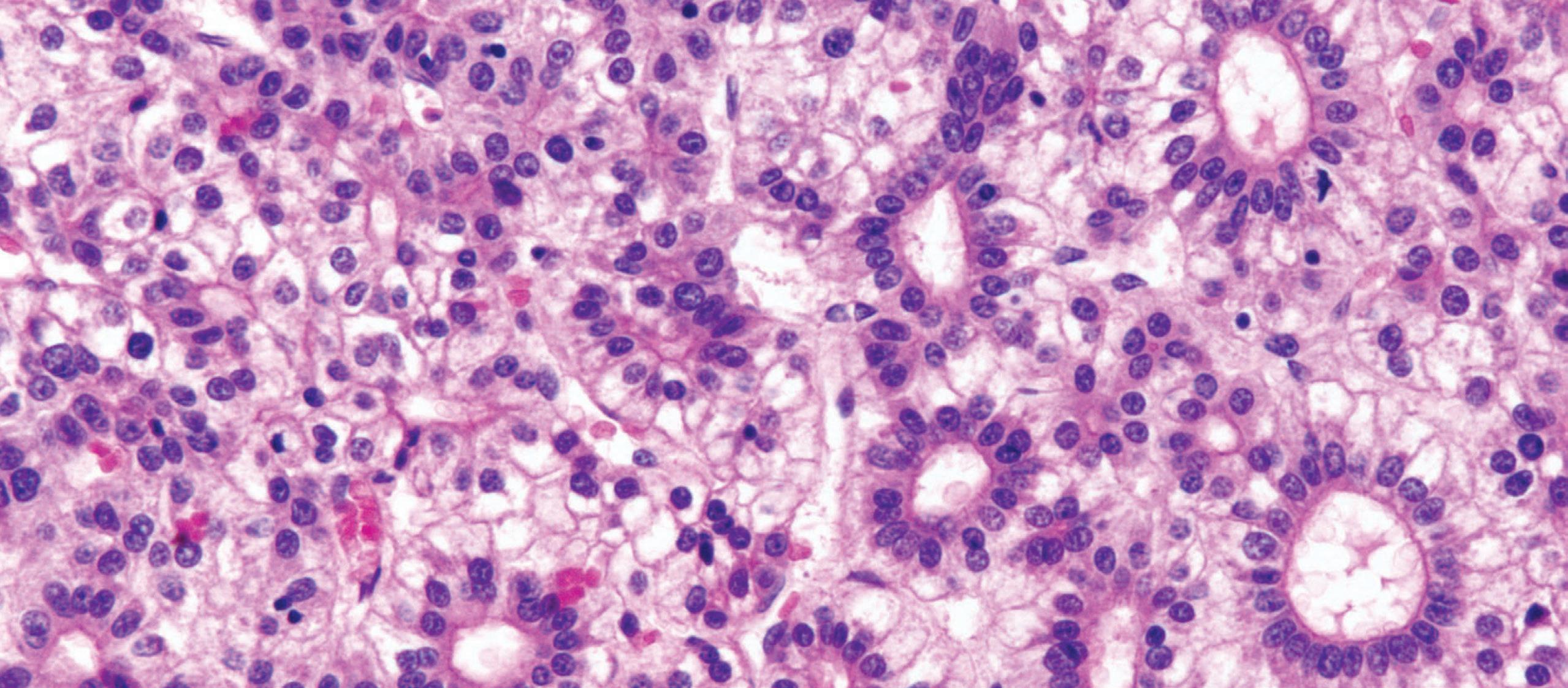

MiCRosCopiC findings

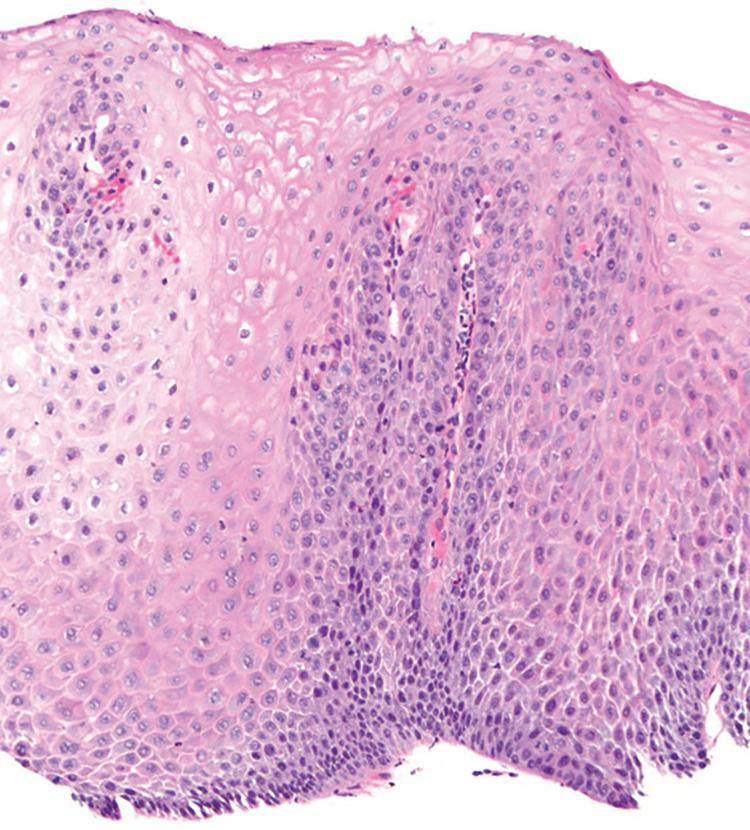

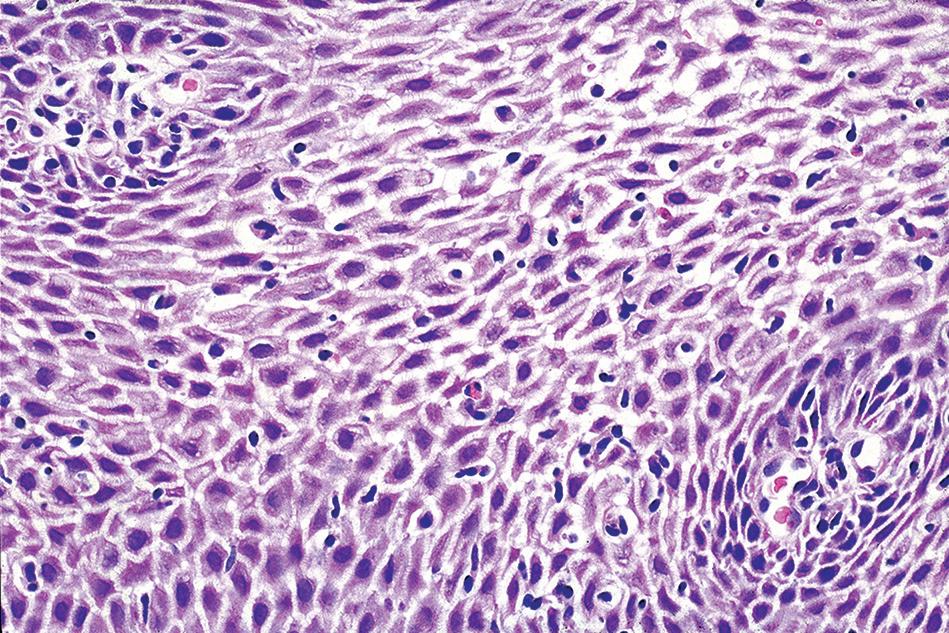

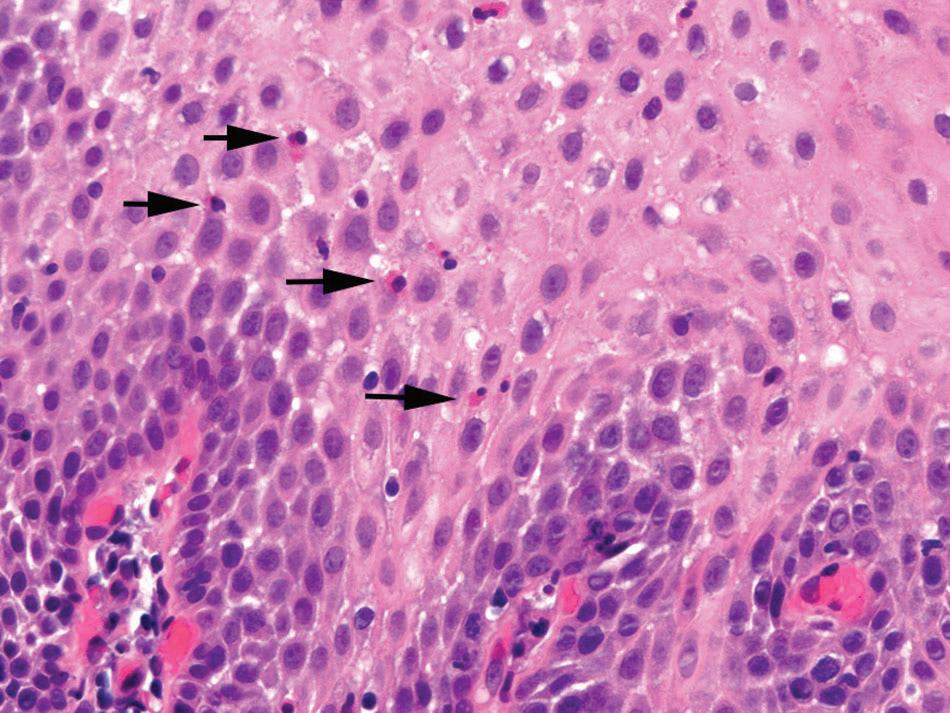

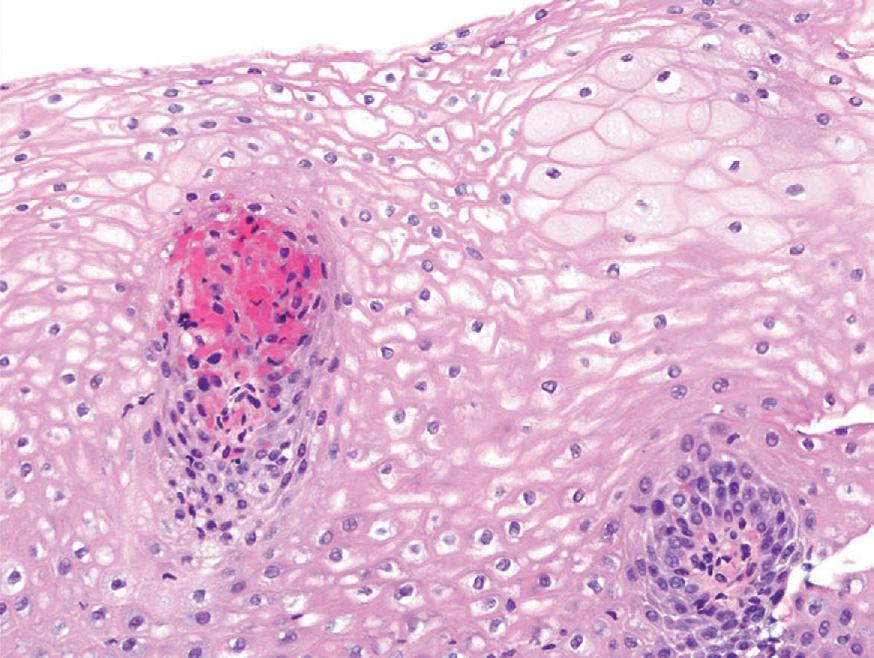

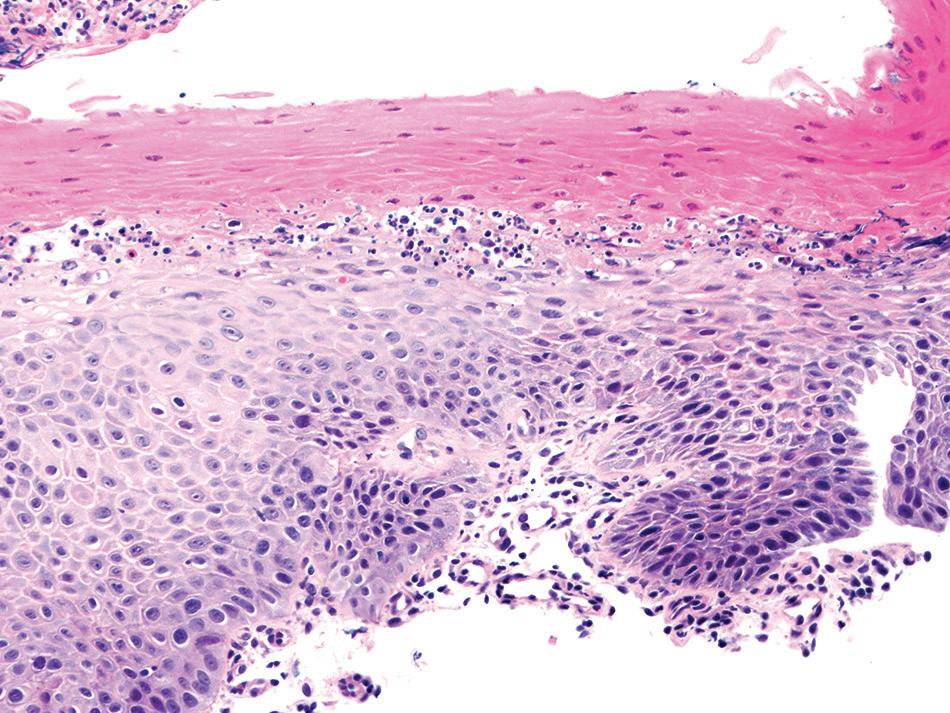

Histologic findings are usually localized to the lower esophagus and taper off or are virtually absent in the proximal segment of esophagus. The typical histologic features include basal cell hyperplasia (thickening of the basal layer to >15% of the total epithelial thickness or more than four to six basal cell layers in well-oriented sections), elongation of the papillae (>60% of the total epithelial thickness), and spongiosis (Fig. 1.2). Inflammatory changes include increased numbers of lymphocytes (Fig. 1.3), neutrophils, and eosinophils (Fig. 1.4). Erosions or ulcers are typically associated with severe GERD. Intraepithelial lymphocytes are predominantly T cells, which tend to acquire an elongated shape (“squiggly lymphocytes”) while traversing between the intercellular spaces. Additional findings including balloon cell change (Fig. 1.5) and hyperkeratosis.

The presence of dilated intercellular spaces (spongiosis; see Fig. 1.3) was once considered to be a promising histologic marker of early GERD. It may be the predominant histologic finding in a patient with GERD; however, given the low interobserver agreement in assessing this feature, it remains less helpful compared with other

FIGURE 1.1

Esophagitis. severe, with hemorrhagic erosions. (Courtesy of Dr. P. vasallo.)

FIGURE 1.2

reflux esophagitis. Basal cell hyperplasia, elongation of papillae, and spongiosis.

FIGURE 1.3

reflux esophagitis. increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes are present among dilated intercellular spaces (spongiosis).

FIGURE 1.4

reflux esophagitis. intraepithelial eosinophils (arrows)

typical features of GERD described already. It should be noted that many patients undergoing endoscopic biopsy have been on a trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and may have been asked to discontinue the medications 1 or 2 weeks or before endoscopy. In this setting, the most common histologic features are increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, basal layer hyperplasia, and elongation of the papillae. The finding of basal layer hyperplasia, elongation of the papillae, and a few eosinophils within 1 to 2 cm of the GEJ may also represent physiologic reflux. This finding is of no clinical significance. In a recent prospective evaluation of 336 patients with clinical symptoms of GERD, Vieth et al. (2016) found that total epithelial thickness of 400 µm or greater at 0.5 cm and 430 µm or greater at 2.0 cm above the Z line was the best histologic feature to reliably identify patients with GERD.

Although endoscopically normal, patients with NERD may have dilated intercellular spaces (spongiosis), as well as basal layer hyperplasia and elongation of the papillae of the squamous epithelium, often grouped together as reactive epithelial change, without significant inflammation. Reporting these findings may be helpful to distinguish patients with NERD from those with functional heartburn.

diffeR ential diagnosis

Eosinophilic esophagitis, infectious esophagitis, and pill esophagitis are in the differential diagnosis. In EoE, there is an increased density of eosinophils per high-power field (hpf) along with eosinophil microabscess formation and superficial layering of eosinophils. More importantly, EoE affects both the distal as well as proximal segments of the esophagus, is associated with characteristic rings and furrows on endoscopy, and is resistant to PPI therapy.

Infectious esophagitis, such as that caused by Candida, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) shows specific features. Candida

esophagitis reveals yeast and pseudohyphal forms that invade the mucosa and are accompanied by severe acute inflammation. Squamous epithelial cells infected with HSV show multinucleation, nuclear molding, and margination of chromatin. Viral cytopathic effect of CMV is best appreciated in stromal and endothelial cells within granulation tissue where large, infected cells show intranuclear and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions.

Pill esophagitis can be associated with prominent eosinophilia, spongiosis, and ulceration. These changes are nonspecific and need to be analyzed in light of the clinical presentation. Polarizable crystalline material may be seen in alendronate-related injury, and crystalline stainable iron can be found in ferrous sulfate-induced esophagitis. Lymphocytic esophagitis (LE), skin disorders such as lichen planus, and esophageal dysmotility states, such as achalasia and strictures, are in the differential diagnosis when increased intraepithelial lymphocytes are present. Esophagitis can also be seen in Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, GVHD, collagen vascular disease, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

pRognosis and theR apy

Prognosis depends on the degree of LES pressures. Extremely low pressures (6 mm Hg) predict a more severe degree of reflux and worse prognosis. Early diagnosis, before the onset of extensive ulcers and strictures, is essential for best patient outcome. Conservative therapy includes significant lifestyle modifications, such as elevation of the head of the bed, avoiding recumbence after meals, weight loss in obese patients, avoiding dietary triggers, and avoiding tobacco and alcohol consumption. PPIs, histamine 2 receptor antagonists, and antacids are the mainstay medical therapy for GERD. Nissen fundoplication and laparoscopic sphincter augmentation are surgical options for those who have failed medical or endoscopic therapy,

FIGURE 1.5

reflux esophagitis. Balloon cells can be present along the luminal aspect (A) or within (B) the squamous epithelium.

REFLUX ESOPHAGITIS—FACT SHEET

Definition

■ inflammation of the lower esophagus resulting from damage caused by acid reflux from the stomach

Incidence and Location

■ the most common form of esophagitis, with prevalence of about 22% in the United states

■ localized to the distal esophagus

Gender and Age Distribution

■ affects both sexes and all age groups

Clinical Features

■ heartburn and regurgitation are the typical symptoms; dysphagia also occurs

■ atypical presentation includes angina-like pain, hoarseness, cough, asthma, and hiccups

■ some individuals are asymptomatic

Prognosis and Therapy

■ Prognosis depends on the degree of lower esophageal sphincter pressure

■ Early detection prevents complications

■ if left untreated, severe ulcerations, strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma may develop

■ treatment includes lifestyle modifications, proton pump inhibitors, and surgical procedures (Nissen fundoplication) in severe cases

■ EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

clI n I cal features

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a primary clinicopathologic disorder of the esophagus that has been associated with an increasing prevalence and has gained significant recognition over the past few years. It is defined as a chronic immune and antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation. Three specific criteria are required to diagnose EoE: symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction, a peak eosinophil count of at least 15 eosinophils/hpf on esophageal biopsy, and eosinophilia limited to the esophagus with other causes of esophageal eosinophilia excluded. Although one of the clinical features of EoE is the lack of response to PPIs, recent studies have shown that one-third or more patients with esophageal eosinophilia can show response to PPIs. This phenomenon has been termed PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia. A recent transcriptome analysis study by Wen et al. (2015) found significant molecular overlap between PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and EoE, suggesting these two entities represent a diagnostic continuum or that PPI-responsiveness is a subphenotype of EoE. However, this relationship is yet to be fully characterized.

reflux esoPhagItIs—PathologIc features

Gross Findings

■ half of symptomatic patients have normal endoscopic examinations

■ Erythema, erosions, or ulceration can be seen

■ Deep ulcers are followed by strictures in severe disease

■ Barrett’s esophagus (salmon-colored mucosal tongues) may be present in long-standing cases

Microscopic Findings

■ architectural changes of basal cell layer hyperplasia, elongation of papillae, and spongiosis

■ increased numbers of intraepithelial eosinophils, lymphocytes, and/or neutrophils

■ Erosion or ulceration

■ Balloon cell change, hyperkeratosis, and increased total epithelial thickness may be seen

Differential Diagnosis

■ Eosinophilic esophagitis has proximal esophageal involvement and often has more severe eosinophilic infiltrates, superficial eosinophil layering, and eosinophilic microabscesses

■ infectious esophagitis (Candida, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus) can be assessed on hematoxylin and eosin and confirmed by special stains and immunohistochemical stains

■ lymphocytic esophagitis and lymphocyte-rich skin disorders typically have only lymphocytes without neutrophils or eosinophils but require clinical correlation

■ Pill esophagitis and Crohn’s disease require clinical correlation

Eosinophilic esophagitis occurs in all age groups but is seen more frequently in young children with atopic symptoms such as eczema, asthma, and food allergies. Symptoms manifest differently in different age groups: whereas infants and children often present with feeding difficulties, regurgitation, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, and vomiting, adults usually describe dysphagia and food impaction with or without chest or abdominal pain. If not recognized early, EoE can progress to odynophagia and stenosis.

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS—FACT SHEET

Definition

■ a form of allergic esophagitis associated with atopic symptoms

■ Can present alone or as part of eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Incidence and Location

■ 1% to 2% of patients undergoing esophageal biopsy

■ the entire esophagus is involved; proximal eosinophil count may be higher than distal; eosinophils may be patchy in distribution

Gender and Age Distribution

■ occurs in all age groups but is more common in the children and young adults

■ Men are more frequently affected than women

Clinical Features

■ symptoms in children include vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and solid food impaction

■ symptoms in adults include dysphagia, food impaction, and chest and abdominal pain

■ associated with food allergies and atopic symptoms

Prognosis and Therapy

■ Best outcome if diagnosed and treated early

■ May lead to severe esophageal strictures if untreated

■ Elimination of food allergens and topical corticosteroids are the treatments of choice

■ When strictures occur, dilation is indicated

Patholog I c features

gRoss findings

Classic endoscopic findings include mucosal rings, furrows (also known as “trachealization” of the esophagus), granularity, exudates, and mucosal fragility (Figs. 1.6 and 1.7). However, in some patients, the endoscopic findings can be completely normal. In longstanding cases, stricture formation may be seen.

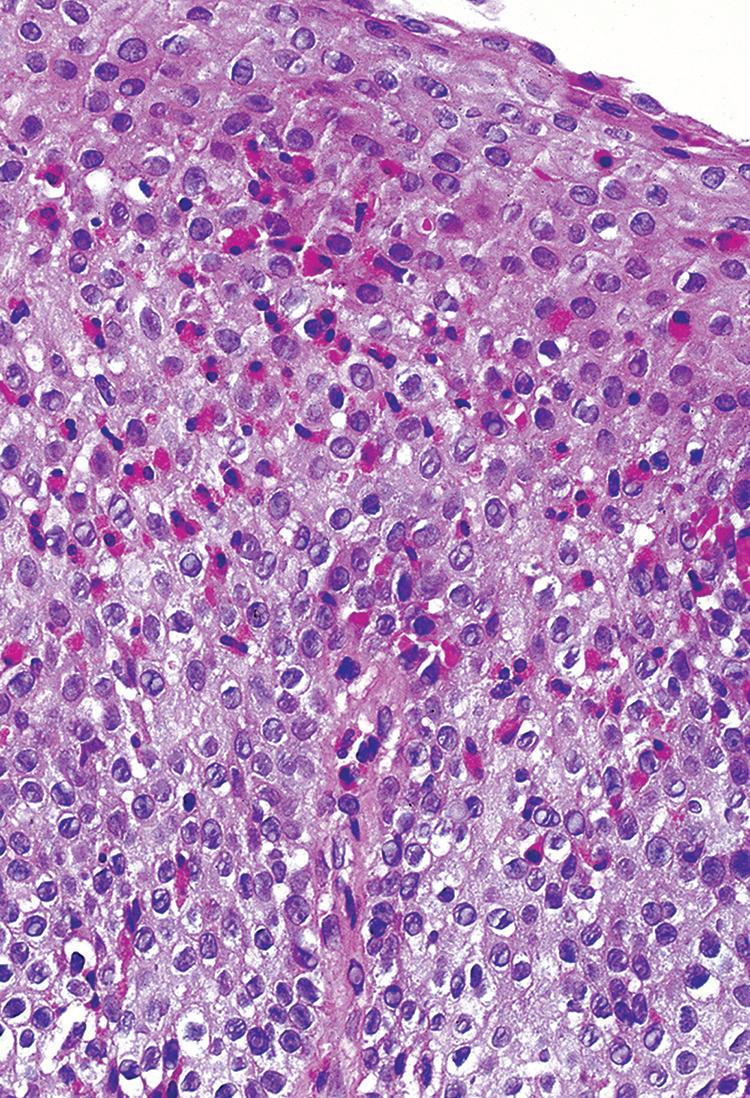

MiCRosCopiC findings

Biopsies show increased intraepithelial eosinophils (≥15 eosinophils/hpf) with concentration of eosinophils toward the luminal aspect of the epithelium (superficial layering). Eosinophilic microabscesses and degranulation of eosinophils (Fig. 1.8) are frequently present. The density of eosinophils can vary with anatomic location of biopsy and within biopsy fragments. In general, biopsies from the proximal segment reveal more eosinophilia than the distal segment. It is therefore recommended that the total number of eosinophils per high-power field

be generated by examining the fragments at low magnification and selecting the high-power field with maximum number of eosinophils (Fig. 1.9). Care should be taken to avoid counting eosinophils within the papillae. Other findings include basal cell hyperplasia, elongation of the papillae to greater than 50% the thickness of the squamous epithelium, spongiosis, lamina propria, and submucosal fibrosis. In patients who have received diet elimination or steroid therapy, follow-up biopsies may be performed to evaluate response to therapy, in which case, giving the exact eosinophil count may be helpful.

FIGURE 1.6

Eosinophilic esophagitis—endoscopy. Mucosal granularity. (Courtesy of Dr. J. Gramling.)

FIGURE 1.7

Eosinophilic esophagitis—endoscopy. typical furrows and rings. (Courtesy of Dr. J. Gramling.)

FIGURE 1.8

Eosinophilic esophagitis. intense eosinophilic infiltrate.

Gross Findings

■ Endoscopic examination reveals mucosal rings, furrows (“trachealization” of esophagus), erythema, and granularity

■ in long-standing cases, strictures are seen

Microscopic Findings

■ Marked increase in intraepithelial eosinophils (≥15/hpf)

■ Eosinophil infiltrates may be more prominent in the proximal than in the distal esophagus

■ superficial layering of eosinophils, eosinophilic microabscesses, and degranulation

■ additional findings include basal cell hyperplasia, elongation of the papillae, spongiosis, and fibrosis of the lamina propria and submucosa

Differential Diagnosis

■ reflux esophagitis changes are mostly seen in biopsy samples from the distal esophagus or gastroesophageal junction

■ in eosinophilic gastroenteritis, eosinophils are also present in other segments of the gastrointestinal tract

■ Drug-induced injury to the esophagus requires clinicopathologic correlation

■ Parasitic infections do not typically affect the entire esophagus. Biopsy specimens may show parasitic organisms

Eosinophilic esophagitis must be distinguished from reflux esophagitis, pill-induced esophagitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and parasitic infections. It is important to note that any of the histologic features of EoE can also

be seen in patients with reflux esophagitis. Distal esophagus-predominant mucosal changes with unremarkable proximal esophageal biopsy favors a diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. Pill-induced esophagitis is often accompanied by ulcer and granulation tissue. Some medications (alendronate, iron supplements) can be visualized on light microscopy. However, confirmation of drug-induced injury requires clinicopathologic correlation. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is usually associated with peripheral blood eosinophilia and affects the rest of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Parasitic infections tend to be a localized phenomenon, and deeper levels may reveal the organism.

The prognosis is excellent when treatment is given promptly. Dietary elimination of the six common offending foods (milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanuts and tree nuts, and seafood) and topical steroids leads to dramatic improvement in symptoms and histology. Rarely, patients refractory to steroid therapy may show disease progression in the form of esophageal strictures that require repeated dilation procedures.

■ LYMPHOCYTIC ESOPHAGITIS

Lymphocytic esophagitis is a poorly defined clinicopathologic entity. A variety of clinical diagnoses may be associated with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes on biopsy; therefore, lymphocytic esophagitis pattern of injury is the preferred diagnostic terminology used by many pathologists. Some studies have demonstrated that the increased intraepithelial lymphocytes of LE in patients with dysmotility are predominantly CD4+ T cells, in contrast to the normally present scattered intraepithelial lymphocytes, which are CD8+ T cells. In patients with LE and normal motility, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are increased.

clI n I cal features

Symptoms include dysphagia, chest pain, heartburn, nausea, and odynophagia. Symptoms can lead to a clinical impression of EoE. Adults and children both can be affected, and most patients are diagnosed in the fifth or sixth decade of life. Men and women are equally affected. Many patients diagnosed with LE also have potentially confounding diagnoses, including GERD, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), hypothyroidism, allergies or asthma, history of radiation or chemotherapy, and connective tissue disease.

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

Prognos I s an D theraPy

FIGURE 1.9

Eosinophilic esophagitis. intraepithelial eosinophils (>20/hpf).

Patholog I c features

gRoss findings

In about a quarter of patients, the endoscopic impression of the mucosa is normal. Endoscopic findings can mimic those seen in EoE and include esophageal rings, esophagitis, and strictures. Findings suggestive of motility disorder may be identified. Erythema, nodularity, plaques, furrows, and webs have also been reported.

neutrophils and eosinophils. Esophageal Crohn’s disease is characterized by increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, especially in the pediatric population. Granulomas may be seen in some cases. However, involvement of the rest of the GI tract is helpful in confirming a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. Achalasia and other motility disorders can have increased intraepithelial lymphocytes on biopsy but usually show radiographic and endoscopic evidence of dysmotility. Inflammatory disorders of the skin, including lichen planus, can affect the esophagus resulting in increased intraepithelial lymphocytes. The presence of interface activity, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, dyskeratotic keratinocytes, or a history of inflammatory skin disease can be helpful.

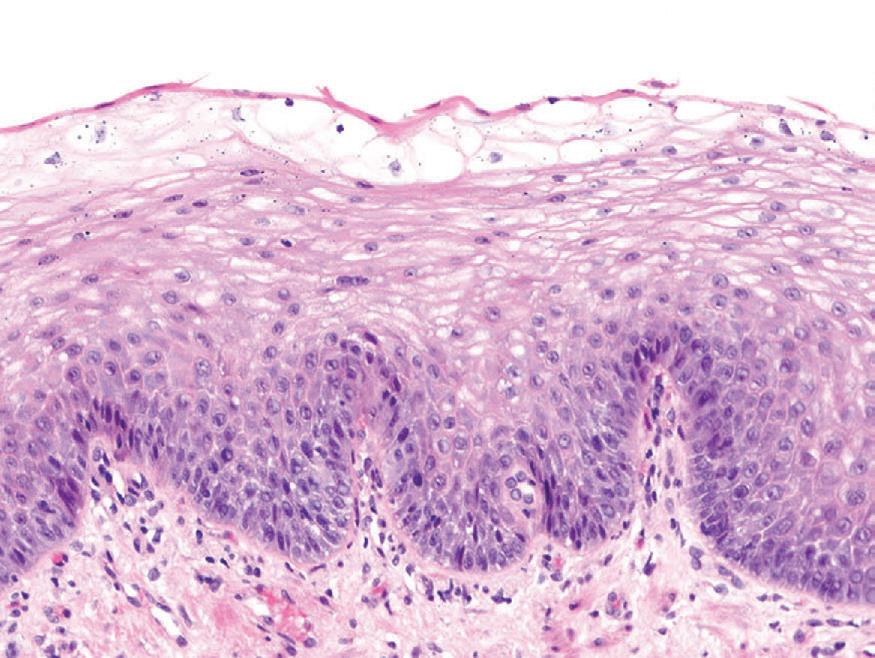

The esophageal biopsy shows increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, predominantly in a peripapillary distribution, with spongiosis of the associated peripapillary squamous epithelium (Fig. 1.10). Similar to EoE, the distribution of intraepithelial lymphocytes is usually patchy and can vary between different biopsy fragments, with some papillae being unaffected. Neutrophils or eosinophils are rare or even absent. There may be accompanying basal cell hyperplasia and spongiosis. Unfortunately, there is no standard number of intraepithelial lymphocytes to diagnosis LE, and studies have included various minimum cut-offs of 20 lymphocytes, 30 lymphocytes, or 50 lymphocytes per high-power field. It is therefore appropriate to render a descriptive diagnosis of “LE pattern of injury” with a comment consisting of the various conditions that may result in this pattern of injury.

Prognos I s an D theraPy

More than half of patients have symptomatic improvement with treatment, which most often includes a PPI. Patients with IBD may benefit from immunomodulatory therapy. Dilation is often helpful in patients with strictures. Follow-up endoscopic biopsies with the LE pattern of injury have shown persistence of LE, progression to reflux or Crohn’s disease, or complete resolution of histologic findings.

LYMPHOCYTIC ESOPHAGITIS—FACT SHEET

Definition

■ increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, predominantly peripapillary, within the squamous esophageal mucosa, with associated spongiosis, and rare to no neutrophils or eosinophils

Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes can be seen in reflux esophagitis, which typically shows more

Peripapillary lymphocytosis with spongiosis.

Incidence and Location

■ incidence has been increasing over time

■ Can be seen anywhere along the esophagus

Gender and Age Distribution

■ Men and women are equally affected

■ any age can be affected; most patients are diagnosed in the fifth to sixth decade of life

Clinical Features

■ symptoms include dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain, and heartburn

■ Patients may also carry a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or allergy

Prognosis and Therapy

■ Most patients have symptomatic improvement with proton pump inhibitors

■ Dysphagia is likely to resolve

■ Gastrointestinal symptoms and histologic findings persist in some patients

mI crosco PI c fI n DI ngs

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

FIGURE 1.10 lymphocytic esophagitis.

Gross (Endoscopic) Findings

■ Normal mucosa, esophageal rings, esophagitis, strictures, features of motility disorder, erythema, nodularity, plaques, furrows, and webs

Microscopic Findings

■ increased peripapillary lymphocytes associated with spongiosis and rare to no neutrophils or eosinophils on biopsy of esophageal squamous mucosa

■ the lymphocytosis is patchy, with some unaffected papillae

Differential Diagnosis

■ Gastroesophageal reflux disease has more than rare granulocytes

■ Crohn’s disease may have granulomas and almost always has involvement of other gastrointestinal sites

■ Motility disorders have radiographic and endoscopic evidence of dysmotility

■ inflammatory disorders of skin may have interface activity, hyperkeratosis, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes

■ LICHEN PLANUS AND LICHENOID ESOPHAGITIS

clI n I cal features

Lichen planus of the esophagus, or lichen planus esophagitis, can occur with or without concurrent cutaneous lichen planus. For both lichen planus and lichenoid esophagitis pattern of injury, girls and women are affected about three times more often than boys and men. Adults and children can be affected, with a median age of about 64 years. Clinical symptoms include dysphagia and stricture and less commonly, esophagitis, heartburn, chest pain, and hiatal hernia. Whereas comorbidities including viral infections (HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C) have been reported in patients with lichenoid esophagitis, hypothyroidism and rheumatologic diseases have been reported in patients with lichen planus esophagitis. Polypharmacy is associated with both conditions.

Patholog I c features

The squamous epithelium and lamina propria are involved by a dense band of predominantly T-cell lymphocytic infiltrates. Lymphocytic inflammation can be patchy or diffuse and affect the upper and lower esophagus. Apoptotic or otherwise degenerating squamous cells (Civatte bodies) in a lichenoid background are diagnostic of lichen planus esophagitis. The background squamous epithelium can be atrophic. Other inflammatory

cell types are not prominent. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates globular immunoglobulin M (IgM) deposits at the squamous–subsquamous interface in lichen planus and cases with negative direct immunofluorescence but with the other histologic features of lichen planus have been termed lichenoid esophagitis pattern of injury.

Graft-versus-host disease, achalasia and other motility disorders, Crohn’s disease, and reflux esophagitis with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes are prominent. LE has a peripapillary lymphocytosis, rather than bandlike, and lacks Civatte bodies.

Lichen planus is a chronic progressive disease that can result in esophageal stricture or even squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Immunomodulatory medications are the mainstay of treatment.

■ CROHN’S DISEASE

clI n I cal features

Esophageal involvement in Crohn’s disease is uncommon, affecting about 6% of patients with Crohn’s disease.

Patholog I c features

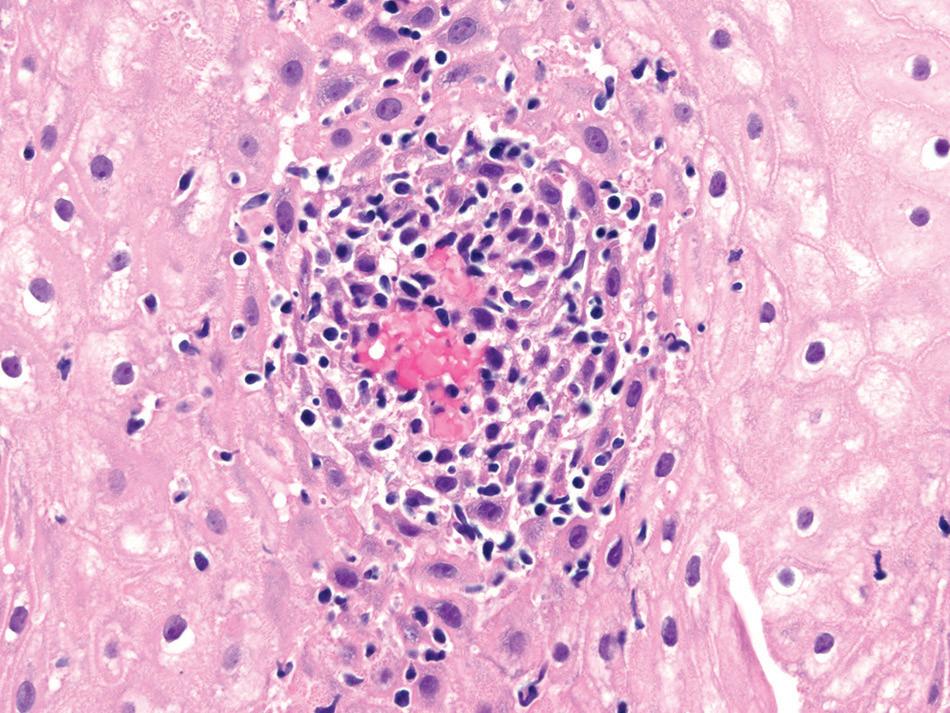

Esophageal biopsies may show increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, especially in pediatric patients (Fig. 1.11).

Well-formed, non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas may also be present. Active inflammation consisting of intraepithelial neutrophils, erosion, or ulceration can be seen.

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

Knowledge of a patient’s diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, by demonstrated involvement in other organs, is useful when considering the differential diagnosis. Granulomatous esophagitis and LE are the main considerations if there is no other evidence of Crohn’s disease

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

Prognos I s an D theraPy

in other organs. Granulomatous esophagitis can be caused by infections, such as mycobacteria and fungus, sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatous, chronic granulomatous disease, or some medications.

Prognos I s an D theraPy

Patients with Crohn’s disease who have esophageal involvement are treated similar to those with disease elsewhere in the GI tract, including antiinflammatory agents and immunomodulators. There is no reported difference in prognosis for patients with Crohn’s disease who have esophageal involvement.

■ GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST

DISEASE

clI n I cal features

Esophageal involvement is uncommon in patients with GVHD and usually accompanies involvement of other parts of the GI tract. Symptoms of esophageal involvement include dysphagia and chest pain. On endoscopy, the mucosa appears friable and may be ulcerated. Rarely, severe cases may show prominent sloughing of the esophageal mucosa.

Patholog I c features

A lichenoid pattern of intraepithelial lymphocytosis along with scattered apoptosis manifested as dyskeratotic keratinocytes is characteristic. In acute GVHD, neutrophilic inflammation, including erosions or ulcers

and rarely sloughing, can be seen. Chronic GVHD may affect the esophagus with lamina propria fibrosis, although this may be difficult to detect on biopsy.

Infectious esophagitis, pill esophagitis, sloughing esophagitis, LE, cutaneous lichenoid disorders affecting the esophagus, and mycophenolate injury are all in the differential diagnosis and can be excluded by clinical history and special stains.

■ IGG4-RELATED ESOPHAGEAL DISEASE

Similar to other organ systems, a rare subset of patients with IgG4-related disease can show esophageal involvement. The clinical presentation can be quite variable and includes strictures, posttreatment achalasia, erosive esophagitis, and submucosal esophageal nodule. The diagnostic criteria for IgG4-esophagitis include the presence of IgG4positive plasma cells (≥50 IgG4-positive plasma cells per high-power field or a ratio of IgG4 to IgG-positive plasma cells ≥50%) and two of the three major histologic features: prominent lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, storiform pattern of fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis. Needless to say, these changes are best appreciated on esophageal resection specimens. The biopsy findings tend to be quite variable and nonspecific. Whereas some cases may show ulceration with a marked increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes and plasma cells, others show an esophagitis dissecans superficialis–like pattern. Immunohistochemical stain is helpful in highlighting a dominant population of IgG4-positive plasma cells. A study by Clayton et al. (2014) found IgG4-positive plasma cells to be prominent in adults with EoE, raising the possibility for a role of the IgG4 pathway in the pathophysiology of EoE. At this time, there is no standard recommendation as to when to perform an IgG4 immunohistochemical stain, especially on biopsy specimens.

■ THERAPY OR TOXIN-RELATED INJURY RADIATION OR CHEMOTHERAPY ESOPHAGITIS

clI n I cal features

Esophageal symptoms in radiation injury depend on factors such as total dose, time period, and previous surgery. At doses of 60 Gy (6000 rads), the esophagus suffers irreversible damage. Acute radiation injury develops

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

FIGURE 1.11

Crohn’s disease. inflammation is predominantly lymphocytic with a few eosinophils and dyskeratotic keratinocytes.

after 2 weeks of therapy and consists of dysphagia, odynophagia, and sometimes hematemesis and chest pain. These symptoms subside after radiation stops. Sequelae of radiation include strictures with dysmotility and dysphagia.

Symptoms are similar with different chemotherapeutic agents. When chemotherapy and radiation therapy are given, their synergistic effect results in more severe damage and more serious symptoms. The incidence of severe acute esophagitis in patients with lung cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy is 14%.

Patholog I c features

gRoss findings

In acute cases, endoscopic examination reveals friable mucosa with edema and coalescent ulcers (mucositis). In chronic cases, strictures develop 13 to 21 months after therapy (Fig. 1.12).

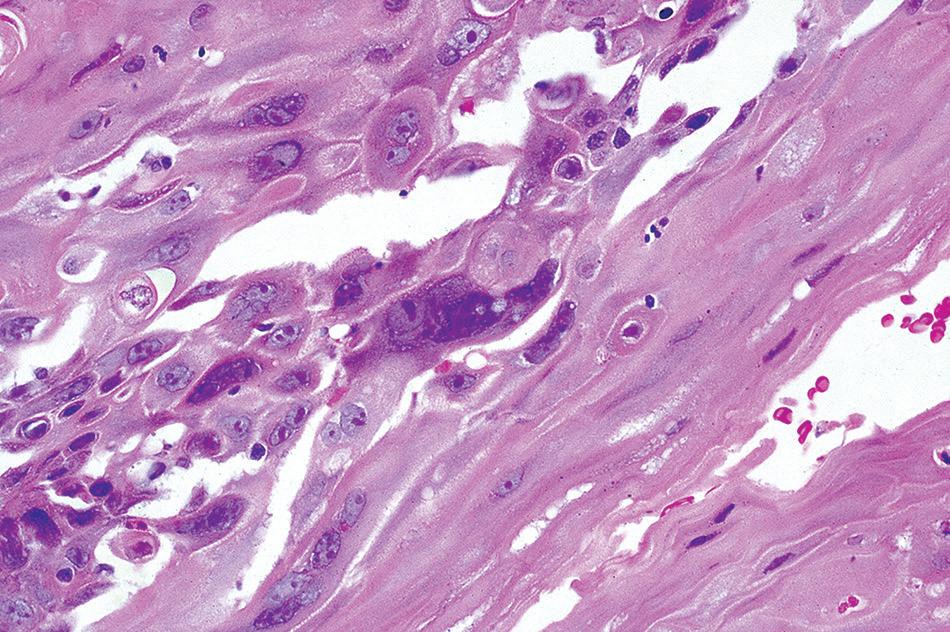

pattern. Multinucleation as well as abundant vacuolated cytoplasm is common (Fig. 1.13). The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is usually preserved. More superficial biopsies show active esophagitis, granulation tissue, or both.

Biopsies are not often procured in the acute stage, but when examined, they show mucosal necrosis and edema. Histologic examination in chronic radiation or chemotherapy esophagitis shows significant atypia in epithelial and stromal cells. The cells are enlarged with hyperchromatic nuclei and a smudged chromatin

Resection specimens of posttreatment esophageal carcinomas often show atrophic mucous glands, squamous metaplasia of esophageal ducts, submucosal and mural fibrosis, and hyalinized vessels. These atrophic glands should not be misinterpreted as residual tumor and can be identified by their location and lobular configuration. The mural fibrosis may alter the wall architecture sufficiently to make staging of residual tumor difficult. A localized ulcer may also be present.

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

The most important entities in the differential diagnosis are malignancy and viral esophagitis. Malignant epithelial cells and radiation- or chemotherapy-induced damage can mimic each other and sometimes coexist in the same patient. Malignant cells show an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei, irregular nuclear membranes, and mitotic activity. Malignant glands may be simplified but are often angulated and do not form a lobule as an atrophic gland would. Atypical stromal cells are usually single cells with ill-defined cell borders, smudged nuclear chromatin, and elongated cell processes. It can mimic therapy-related changes in an isolated malignant cell, which usually has a well-defined cell border and denser eosinophilic cytoplasm. A cytokeratin immunostain can be helpful to confirm the presence of a malignant cell versus an atypical stromal cell. Multinucleation can be confused with herpes infection, but there is no molding or margination of chromatin. Special immunostains for HSV are indicated to help in this differential diagnosis.

mI crosco PI c fI n DI ngs

FIGURE 1.13

radiation esophagitis. Cytomegaly with pale nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, and multinucleation.

FIGURE 1.12

Esophageal stricture. (From turk J l, ed. royal College of surgeons of England. Slide Atlas of Pathology. Alimentary Tract System london, Gower Medical, 1986, with permission.)

Prognos I s an D theraPy

Reversible damage occurs in doses lower than 6000 rads. There prognosis is more severe when the damage is a result of both radiation and chemotherapy. Esophageal dilation is indicated when stricture develops.

RADIATION

Definition

■ Damage to the esophagus as a result of radiation, chemotherapy, or both

Incidence and Location

■ the incidence of severe acute esophagitis in patients with lung cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy is 14%

■ any part of the esophagus exposed to the therapy may be affected

Clinical Features

■ acute radiation injury occurs after 2 weeks of therapy, and symptoms include dysphagia, odynophagia, hematemesis, and chest pain

■ Chronic radiation injury resulting in stricture leads to dysmotility and dysphagia

■ symptoms from chemotherapy are similar

Prognosis and Therapy

■ Damage is reversible if exposure is less than 6000 rads

■ the prognosis is worse when damage is from a combination of radiation and chemotherapy

■ Dilation is indicated for therapy of esophageal stricture

raDIatIon or chemotheraPy esoPhagItIs—PathologIc features

Gross (Endoscopic) Findings

■ acute injury includes friable mucosa with edema and ulceration

■ Chronic injury is characterized by stricture

Microscopic Findings

■ Mucosal necrosis and edema are seen in the acute stage on biopsy

■ atypia of stromal cells and epithelial cells are seen in the chronic stage

■ Enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei with smudged chromatin and multinucleation

■ vacuolated cytoplasm and preserved nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio

■ in posttreatment resection specimens, there are atrophic mucous glands, squamous metaplasia of esophageal ducts, fibrosis within the wall (sometimes distorting the normal wall organization and architecture), and hyalinized vessels. localized ulceration can also be seen

Differential Diagnosis

■ Malignancy can coexist with radiation- or chemotherapy-induced damage or can be missed if the clinical history is not known

■ Multinucleation or atypia of viral esophagitis can be confused with radiation- or chemotherapy-induced damage and atypia. immunohistochemical stains for viral entities should be used

■ PILL ESOPHAGITIS

clI n I cal features

Pill esophagitis is a result of esophageal injury that occurs because of prolonged direct mucosal contact with tablets or capsules taken in therapeutic doses. Commonly implicated agents include antibiotics (particularly doxycycline), potassium chloride, ferrous sulfate, quinidine, and alendronate, among others.

Although the older adult population is more often affected, pill esophagitis can occur at any age. The main symptoms are sudden retrosternal pain and painful swallowing. The patient often gives a history of having taken the medication with little or no fluid just before going to bed and was aware that the pill had “stuck” in the chest. Some patients present with atypical symptoms, suggesting a myocardial infarction or reflux disease. Some medications such as sodium valproate, ferrous sulfate, and aspirin–caffeine compounds have been associated with esophageal perforation and mediastinitis.

Patholog I c features

gRoss findings

Endoscopic examination reveals the presence of one or more discrete ulcers, often containing residual pill fragments. The lesions are more commonly seen at the level of the aortic arch.

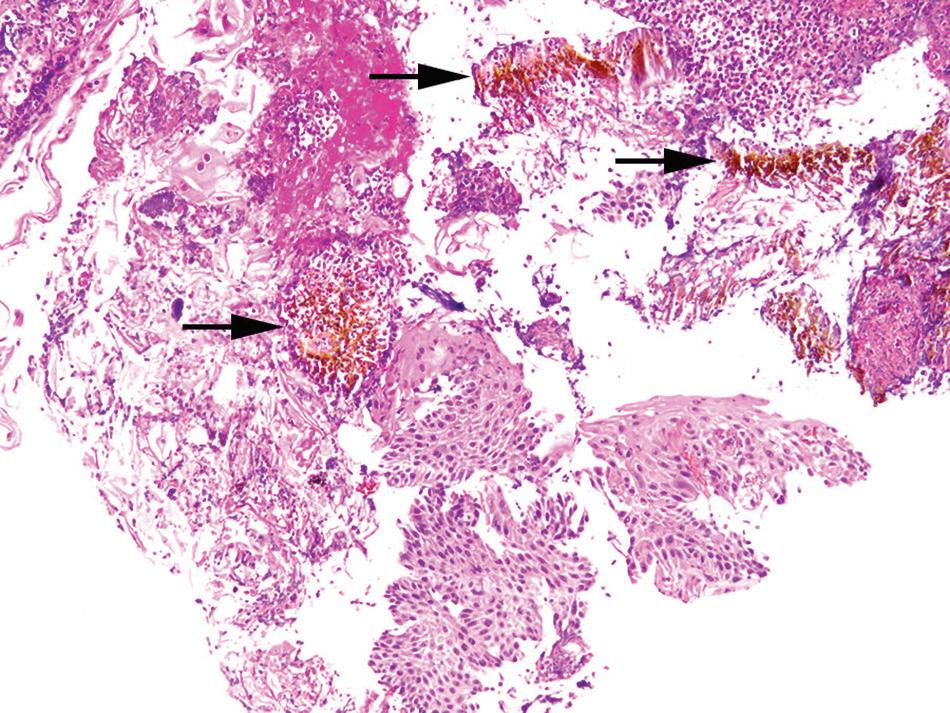

MiCRosCopiC findings

Histologic findings are nonspecific and include superficial erosions or ulcerations with marked acute inflammation and florid granulation tissue (Figs. 1.14 and 1.15). However, many patients have prominent eosinophilia, spongiosis, and necrosis of the squamous epithelium. Polarizable crystalline material (alendronate) or stainable crystalline iron can be demonstrated in the ulcer bed.

diffeR ential diagnosis

Severe GERD, infections, and EoE can mimic pill esophagitis. Fungal or viral infection can be excluded

Pill esophagitis. Esophageal mucosa with ulceration.

PI ll esoPhagItIs—PathologIc features

Gross Findings

■ one or more discreet ulcers, which may contain pill fragments, most commonly at the level of the aortic arch

Microscopic Findings

■ Nonspecific erosions or ulcerations

■ Prominent eosinophilia, spongiosis, and necrosis of the squamous epithelium

■ Pill fragments or polarizable or stainable crystalline material can sometimes be seen

Differential Diagnosis

■ severe gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis have basal cell hyperplasia, spongiosis, and prior typical clinical symptoms

■ Fungal or viral infections can be excluded by special stains and immunohistochemistry

by special stains. GERD and EoE are typically associated with other salient histologic findings of basal cell hyperplasia, spongiosis, and history of prior clinical symptoms.

Prognos I s an D theraPy

Most patients have an uneventful recovery after discontinuing use of the medication. Antireflux medication and topical anesthetics may also be helpful to relieve symptoms.

Pill esophagitis. refractile brown iron pill material (arrows) is present among inflamed squamous epithelium.

PILL ESOPHAGITIS—FACT SHEET

Definition

■ Esophageal injury that occurs because of prolonged direct mucosal contact with tablets or capsules taken in therapeutic doses

Gender and Age Distribution

■ any age can be affected but more common in older adults

Clinical Features

■ antibiotics are among the common medications that cause pill esophagitis

■ Feeling of a pill being stuck in the esophagus after taking the pill with little or no fluid, especially just before lying down

■ atypical symptoms can mimic myocardial infarction or reflux

Prognosis and Therapy

■ recovery occurs after stopping the medication

■ antireflux medication or topical anesthetic may help alleviate symptoms

■ ESOPHAGITIS DISSECANS SUPERFICIALIS OR SLOUGHING ESOPHAGITIS

clI n I cal features

Sloughing esophagitis is a recently described entity that has also been reported in the literature as esophagitis superficialis dissecans. It is unclear whether these are two distinct entities or represent a spectrum of the same disease process. Patients are typically middle aged, debilitated, and taking multiple (five or more) medications (especially bisphosphonates, potassium chloride, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), often including a central nervous system depressant. Consumption of hot beverages, chemical irritants, smoking, and collagen vascular diseases have also been associated with this

FIGURE 1.14

FIGURE 1.15

CHAPTER 1 Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Esophagus

condition. Clinical symptoms include upper GI bleed, dysphagia, and nausea and vomiting.

Patholog I c features

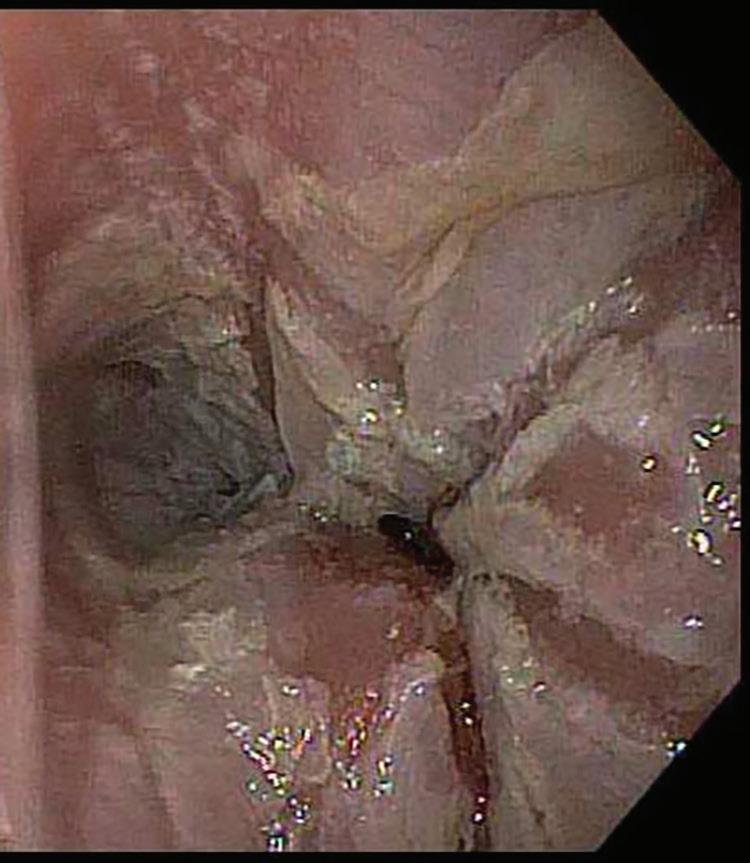

gRoss findings

Endoscopically, necrosis of the superficial squamous epithelium is seen as white plaques or membranes, the edges of which may be detached from the underlying tissue, creating the appearance of linear ulcers (Fig. 1.16). The distal esophagus is most often affected. Involvement of the mid and proximal esophagus can be seen when the process is more diffuse.

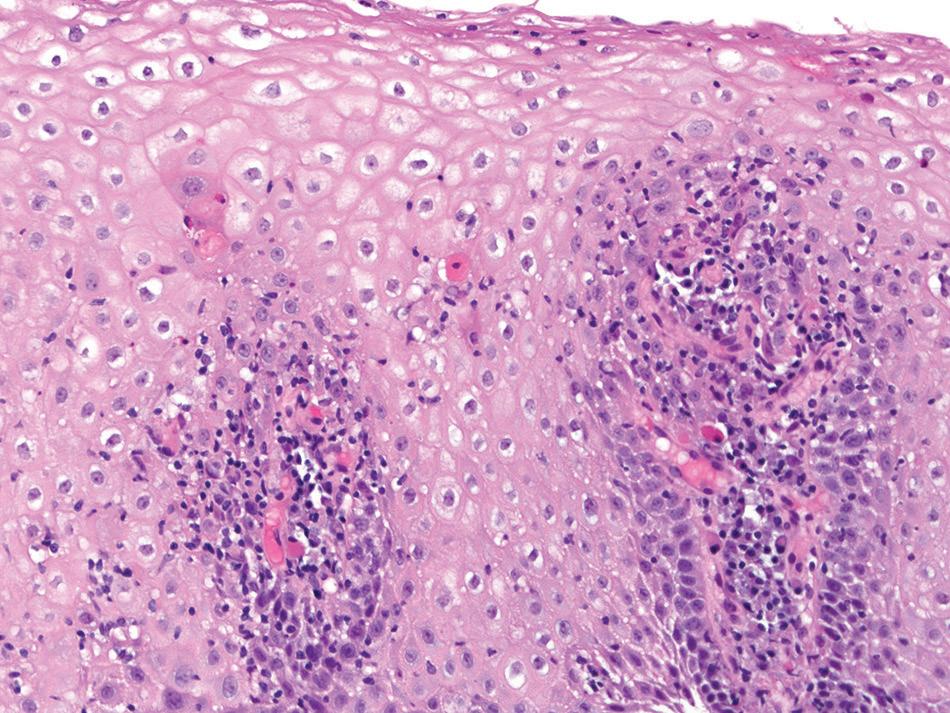

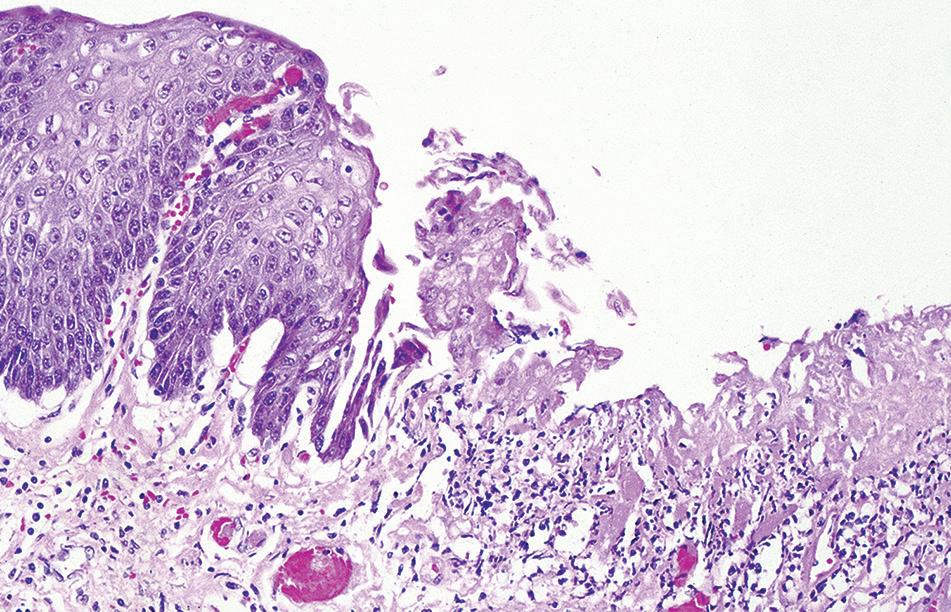

MiCRosCopiC findings

The most striking feature is a two-toned appearance of the squamous mucosa at low power, with the superficial necrotic aspect being markedly eosinophilic compared with the viable basal aspect (Fig. 1.17). A distinct demarcation between the two layers is present, and neutrophils and apoptotic debris may be present along this line of demarcation. In some cases, the superficial layer shows parakeratosis and sloughing of the necrotic squamous epithelium.

DI fferentIal DIagnos I s

Fungal esophagitis, pill esophagitis, and caustic esophageal injury can all result in necrosis of the esophageal epithelium. Clinical history of ingestion and special stains for fungal elements can help distinguish these entities.

sloughing esophagitis. superficial necrosis is seen as an eosinophilic luminal aspect and a basophilic basal aspect. this case has degenerative nuclei in between the layers.

Bullous skin lesions affecting the esophagus should also be considered and can be distinguished by their characteristic histologic features and immunofluorescence. Acute esophageal necrosis may have a similar endoscopic appearance, but histologically, the characteristic features include diffuse and deep ulceration with fibrinopurulent exudate and full-thickness mucosal necrosis.

Prognos

I s an D theraPy

The lesion tends to heal with acid suppressants, topical anesthetics, and discontinuation of the offending agents. A high death rate of patients with sloughing esophagitis is attributed to the comorbid conditions.

ESOPHAGITIS DISSECANS SUPERFICIALIS OR SLOUGHING ESOPHAGITIS—FACT SHEET

Definition

■ a recently described entity that may be a spectrum of the same disease process, characterized by detachment of the superficial squamous epithelium

Clinical Features

■ affects middle-aged debilitated patients taking five or more medications, which often include a central nervous system depressant, bisphosphonates, potassium chloride, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

■ also can occur in the setting of hot beverage consumption, chemical irritant exposure, smoking, and collagen vascular disease

■ symptoms include upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting

Prognosis and Therapy

■ lesions heal with acid suppressants, topical anesthetics, and discontinuation of the offending agents

■ high death rate attributed to comorbid conditions

FIGURE 1.16

sloughing esophagitis. Endoscopically, white plaques with detached edges characterize the superficial epithelial necrosis.

FIGURE 1.17