NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION, DATING AND REFERENCING

TRANSLITERATION

Generally speaking, I have adopted the system for Middle Mongolian names found in J.A. Boyle’s partial translation of the Jāmi' altawārīkh of Rashīd al-Dīn, The Successors of Genghis Khan (New York, 1971). However, Turkish and Mongolian proper names, notoriously, have long defied consistent transcription. To take just two examples, the name Toqa Temür, encountered in the history of the Golden Horde, can also be transcribed as Togha Temür, and the first element is identical with the name of a Chaghadayid khan that is invariably spelled Du’a (d. 1307). The name of the celebrated Ilkhan of Iran, Ghazan (d. 1304), is identical with those of the Chaghadayid khan Qazan (d. 1346) and the latter’s antagonist, the amir Qazaghan (all three variant forms represent the Mongolian word for ‘cauldron’). Any attempt at consistency here would result in spellings unrecognisable to historians of the Mongols and would fail to compensate by imparting any particular benefit to non-specialists.

The Iranian world figures extensively in this book, and I use the modern name Iran rather than the term Persia most often employed by nineteenth- and twentieth-century writers. For place names where an anglicised form is in common use (e.g. Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo, Herat) and for titles/ranks which have long been Europeanised (e.g. caliph, amir, sultan), these forms will be given (but ‘wazir’ in

preference to ‘vizier’); although when the word ‘sultan’ forms part of a proper name it appears with diacritics thus: Sulṭān. Otherwise, for Arabic and Persian, I have observed the conventions found in The EncyclopaediaofIslam, 2nd edn (Leiden, 1954–2009), except that I employ ch (in place of č), j (replacing dj) and q (not k.). Persian is transliterated as if it were Arabic: thus th rather than s, d. rather than ż, and w rather than v; though the Arabic conjunction wa(‘and’) sometimes appears as -u in Persian phrases. Persian-Arabic spelling is also used for a nisba (e.g. Samarqandī, Ḥalabī), even where it is derived from a Turkish locality (thus Āqsarāyī, from Akseray). The Arabic definite article al- is omitted, however, in the nisbas of persons of non-Arab stock (as with Juwaynī, Āqsarāyī, Faryūmadī and Yazdī). I likewise omit the iḍāfa(-i) prior to the nisba in Persian proper names. The Arabic-Persian patronymic (bin, ibn), for which the Timurid sources frequently substitute the iḍāfa, is regularly abbreviated to ‘b.’, except when it designates an individual referred to generally by his patronymic alone – usually an author, as in the case of Ibn 'Arabshāh and Ibn Khaldūn.

Turkish, Mongol and Persian-Arabic terms that recur many times in the text (for example, quriltai, noyan, tümen, malik) are given, after the first appearance, in roman type rather than italics, and without diacritics. The names of dynasties always appear without diacritics (thus Jalayirids rather than Jalāyirids, Muzaffarids in preference to Muẓaffarids); so too do adjectives relating to place names (hence Khwarazmian rather than Khwārazmian). I have employed the form ‘Mamlūk’ for the regime that controlled Egypt and Syria, while using ‘mamluk’ (with lower-case initial letter and no macron) for the elite military slaves from whom the regime takes its name. I have called the fourteenth-century Golden Horde khan Özbeg, while retaining the more familiar form Uzbek for the people whose name was ultimately derived from his.

The Persian form of the name Mongol and its derivatives, as they appear in this book, also present inconsistencies. Although I have used ‘Mughūl’ and ‘Mughūlistān’, as found in Timurid sources, for the eastern Chaghadayid khanate and its inhabitants, the dynasty

descended from Timur that ruled in India from 1525 to 1858 is referred to as ‘Mughul’ with no macron over the second vowel (rather than ‘Moghul’ or ‘Mughal’ as more frequently encountered in the secondary literature). Throughout, I restrict the term Mongol to the Mongolian people in general, whether domiciled in present-day Mongolia or engaged in the conquest of and rule over Asia.

The two ethnic labels Uighur and Tājīk are always used in their medieval sense, the former referring to the Turkic inhabitants of the Tarim basin (rather than to the modern population of the Chinese province of Xinjiang) and the term Tājīk applying generally to speakers of Persian or Arabic (rather than to the inhabitants of present-day Tajikistan). Perhaps the most puzzling convention I have adopted relates to Timur’s Turco-Mongolian military forces. I have employed for this purpose ‘Chaghatay’ (the term which is also in general use for a widely spoken Central Asian dialect of the Turkish language), whereas ‘Chaghadayid’ refers to the polity within which Timur originated and rose to power, and to its ruling dynasty, founded by Chinggis Khan’s second son Chaghadai.

Given the fact that various letters in the Arabic-Persian script differ from one another only in the placing of diacritical points, the reading of Turkish and Mongolian proper names in the primary sources (either printed or in manuscript) is frequently problematic. I have used small capitals, particularly in the notes, to transliterate an uncertain name in a text: here Č represents the double consonant ch, G. stands for gh, Š for sh, Ṯ for th and X for kh, and the long vowels ā, ū and ī are represented by A, W and Y respectively. When diacritical points seem to be incorrect (or lacking altogether) in the manuscript original, I have transliterated the Arabic-Persian consonant as it appears there, but in italics. Thus H.[ﺣ ,ح] might in fact have stood for J [ﺟ ,ج], Č [ﭽ ,چ] or X [ﺨ ,خ]. A mere ‘tooth’ without diacritical points, which could accordingly represent B, P, T, T‒, N, Y or ʼ (if simply the bearer of the hamza, ﺋ), is indicated in transcription by a dot. An asterisk always precedes the hypothetical reconstruction of a name.

The spelling of Chinese names and terms conforms to the pinyin system. Russian is transliterated according to a slightly modified version of the Library of Congress system. For modern Mongolian I have adapted the system of transliteration for Russian: thus č, š, x and ž, rather than ch, sh, khand zh.

DATING

Where dates are cited simultaneously according to both the Hijrī calendar and the Common Era, the former appears first. Thus: 807/1404–5; 25 Sha'bān 736/8 April 1336.

REFERENCING

I have followed the same practice as I did in TheMongols and the Islamic World: namely, often citing together more than one version of a primary text, for instance the two English translations of Clavijo’s narrative, by Markham and Le Strange respectively, or the two modern editions of Yazdī’s Ẓafar-nāma, by 'Abbāsī (1957) and by Ṣādiq and Nawā’ī (2008). This is designed for the benefit of readers who (like myself on so many occasions) have access to only one such version and find an author’s exclusive reliance on a single alternative text deeply frustrating.

ABBREVIATIONS

TEXTS

CC Rashīd al-Dīn, Jāmi' al-tawārīkh, trans. Thackston, CompendiumofChronicles(2012 edn)

Clavijo Clavijo, EmbajadaaTamorlán: (1859) trans. Markham; (1928) trans. Le Strange

CO Ḥāfiẓ-i Abrū, Cinqopusculesde Ḥāfiẓ-iAbrū, ed. F. Tauer

DPT Yazdī, Ghiyāth al-Dīn 'Alī, Rūz-nāma-yighazawāt-iHind, trans. Semenov, Giiāsaddīn 'Alī.DnevnikpokhodaTīmūra vIndiiu

DzhT Rashīd al-Dīn, Jāmi' al-tawārīkh, ed. Romaskevich et al., Dzhāmi' at-tavārīkh, I, part 1; ed. Alizade, Dzhāmi' attavārīkh, II, part. 1; ed. Alizade, Dzhāmī-at-tavārīkh, III

GW Waṣṣāf, Tajziyatal-amṣār, partial trans. by HammerPurgstall, GeschichteWassaf’s

HA Ḥāfiẓ-i Abrū

HWC Juwaynī, Ta’rīkh-ijahān-gushā, trans. Boyle, TheHistory oftheWorld-Conqueror

IA Ibn 'Arabshāh, 'Ajā’ibal-maqdūr: (1979) ed. 'Umar; (1986) ed. al-Ḥimṣī; see also TGAbelow

IB Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Tuḥfatal-nuẓẓār

IKPI M.Kh. Abuseitova et al. (general eds), Istoriia Kazakhstanavpersidskikhistochnikakh, 5 vols (Almaty, 2005–7): I (Jamāl al-Qarshī, al-Mulḥaqātbil-Ṣurāḥ); III (anon., Mu'izzal-ansāb); V (Izvlecheniiaizsochinenii XIII–XIXvekov)

IKT Ibn Khaldūn, al-Ta'rīfbi-IbnKhaldūn, partial trans. by Fischel, IbnKhaldūnandTamerlane

JT Rashīd al-Dīn, Jāmi' al-tawārīkh(the edition by Rawshan and Mūsawī, unless otherwise specified)

Khwāfī Khwāfī, Faṣīh. al-Dīn Aḥmad, Mujmal-iFaṣīḥī: (1962) ed. Farrukh; (2007) ed. Naṣrābādī

MA anonymous, Mu'izzal-ansāb

Masālik Ibn Faḍl-Allāh al-'Umarī, Masālikal-abṣār(partial edn and trans. by Lech, DasmongolischeWeltreich, unless otherwise stated)

MFW Rubruck, Itinerarium, trans. and ed. P. Jackson with D. Morgan, TheMissionofFriarWilliamofRubruck

Mignanelli Mignanelli, Beltramo di, DeruinaDamasci: (1764) ed. Baluze; (2013) ed. Helmy in TraSiena

MM Christopher Dawson (ed.), TheMongolMission

MP Marco Polo, LeDevisementdumonde(Ménard’s edition unless otherwise specified)

Naṭanzī Naṭanzī, Muntakhabal-tawārīkh: (1957) ed. Aubin; (2004) ed. Istakhrī

PC Plano Carpini, YstoriaMongalorum, ed. Menestò et al.

PSRL Polnoesobranierusskikhletopisei

RIS L.A. Muratori (ed.), RerumItalicarumScriptores, 25 vols in 28 parts (Milan, 1723–51); 2nd series, Raccoltadegli storiciitaliani, ed. Giosuè Carducci et al., 34 vols (Città di Castello and Bologna, 1900–75)

RN Yazdī, Ghiyāth al-Dīn 'Alī, Rūz-nāma-yighazawāt-iHind: (1915) ed. Zimin; (2000) ed. Afshār

Sayfī Sayfī (Sayf b. Muḥammad b. Ya'qūb al-Harawī), Ta’rīkhnāma-yiHarāt: (1944) ed. aṣ-Ṣiddíqí; (2004) ed. Ṭabāṭabā’ī Majd

SF Van Den Wyngaert (ed.), SinicaFranciscana, I

SGK Rashīd al-Dīn, Jāmi' al-tawārīkh, trans. Boyle, The SuccessorsofGenghisKhan

SH Mongghol’unniuchatobcha’an(The Secret History of the Mongols), trans. with commentary by De Rachewiltz

Shāmī, ZN Shāmī, Niẓām al-Dīn, Ẓafar-nāma

SMIZO V.G. Tizengauzen (ed.), Sbornikmaterialov, otnosiashchikhsiakistoriiZolotoiOrdy

SP Rashīd al-Dīn, Shu'ab-ipanjgāna

Ta'rīf Ibn Khaldūn, al-Ta'rīfbi-IbnKhaldūn: (1951) ed. al-Ṭanjī; (2008) ed. and trans. Cheddadi; see also IKTabove

TGA Ibn 'Arabshāh, 'Ajā’ibal-maqdūr, trans. J.H. Sanders, TamerlaneorTimur,theGreatAmir

TGNN Anonymous, Tawārīkh-iguzīda-yinuṣrat-nāma

TJG Juwaynī, Ta’rīkh-ijahān-gushā

TN Jūzjānī, Ṭabaqāt-iNāṣirī

TR Ḥaydar Dughlāt, Ta’rīkh-iRashīdī

Waṣṣāf Waṣṣāf, Tajziyatal-amṣār: (1853) Bombay lithograph edn; (2009) partial edn by Nizhād

WR Rubruck, Itinerarium, ed. Chiesa

Yazdī, ZN Yazdī, Sharaf al-Dīn 'Alī, Ẓafar-nāma: (1957) ed. 'Abbāsī; (1972) ed. Urunbaev; (2008) ed. Ṣādiq and Nawā’ī

Zayn al-Dīn Zayn al-Dīn b. Ḥamd-Allāh Mustawfī Qazwīnī, Dhayl-i

Ta’rīkh-iguzīda: (1990) ed. and trans. Kazimov and Piriiev; (1993) ed. Afshār

ZT

Ḥāfiẓ-i Abrū, Zubdatal-tawārīkh

PERIODICAL AND SERIES TITLES AND WORKS OF REFERENCE

AEMA ArchivumEurasiaeMediiAevi

AF Asiatische Forschungen

AHSS Annales.Histoire,SciencesSociales

AKM Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes

Al-Masāq Al-Masāq.IslamandtheMedievalMediterranean

ANSMN AmericanNumismaticSocietyMuseumNotes

AOH ActaOrientaliaAcademiaeScientiarumHungaricae

AS AsiatischeStudien

BEC Bibliothèquedel’ÉcoledesChartes

BEO Bulletind’ÉtudesOrientalesdel’InstitutFrançaisdeDamas

BHM BulletinoftheHistoryofMedicine

BI Bibliotheca Islamica

BIAL Brill’s Inner Asian Library

BSOAS BulletinoftheSchoolofOrientalandAfricanStudies

CAC Cahiersd’AsieCentrale

CAJ CentralAsiaticJournal

CHC TheCambridgeHistoryofChina: VI: AlienRegimesand BorderStates907–1368, ed. Herbert Franke and Denis Twitchett (Cambridge, 1994); VIII: TheMingDynasty,1368–1644, ed. Denis Twitchett and Frederick W. Mote (Cambridge, 1998), 2 parts; IX, part 2: TheCh’ingDynastyto1800, ed. Willard J. Peterson (Cambridge, 2016)

CHE Carl F. Petry (ed.), TheCambridgeHistoryofEgypt, I: Islamic Egypt,640–1517(Cambridge, 1998)

CHI TheCambridgeHistoryofIran: V: TheSaljuqandMongol Periods, ed. J.A. Boyle (Cambridge, 1968); VI: TheTimurid andSafavidPeriods, ed. Peter Jackson and Laurence Lockhart (Cambridge, 1986)

CHIA Nicola Di Cosmo, Allen J. Frank and Peter B. Golden (eds), TheCambridgeHistoryofInnerAsia.TheChinggisidAge (Cambridge, 2009)

CHT Kate Fleet (ed.), TheCambridgeHistoryofTurkey, I: ByzantiumtoTurkey,1071–1453(Cambridge, 2009)

CSIC Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization

CSSH ComparativeStudiesinSocietyandHistory

CWH TheCambridgeWorldHistory: V: ExpandingWebsof ExchangeandConflict,500 CE–1500 CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks (Cambridge, 2015); VI: TheConstructionofaGlobalWorld,1400–1800 CE, ed. Jerry H. Bentley, Sanjay Subrahmanyam and Merry E. WiesnerHanks (Cambridge, 2015), part 1: Foundations; part 2: PatternsofChange

D&R Documents et recherches sur l’économie des pays byzantins, islamiques et slaves et leurs relations commerciales au Moyen Age

DTS V.M. Nadeliaev et al. (eds), Drevnetiurkskiislovar' (Leningrad, 1969)

EDT Sir Gerard Clauson (ed.), AnEtymologicalDictionaryofPreThirteenth-CenturyTurkish(Oxford, 1972)

EI2

EI3

EncyclopaediaofIslam, 2nd edn, ed. Ch. Pellat, C.E. Bosworth et al., 13 vols (Leiden, 1954–2009)

EncyclopaediaofIslamThree, ed. Marc Gaborieau et al. (Leiden and Boston, MA, 2007–in progress)

EIr EncyclopaediaIranica, ed. Ehsan Yarshater (New York and Costa Mesa, CA, 1982–in progress; and https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/browse/encyclopaediairanica-online)

EMME Christopher P. Atwood (ed.), EncyclopaediaofMongoliaand theMongolEmpire(New York, 2004)

ES EurasianStudies

EV ÉpigrafikaVostoka

GAL Carl Brockelmann (ed.), GeschichtederarabischenLitteratur, 2 vols, 2nd edn (Leiden, 1943–9), and 3 supplement vols (Leiden, 1937–42)

GMS Gibb Memorial Series

HCCA, IV C.E. Bosworth and M.S. Asimov (eds), HistoryofCivilizations ofCentralAsia, IV. A.D.750totheEndoftheFifteenth Century, part 1: TheHistorical,SocialandEconomicSetting (Paris, 1998); part 2: TheAchievements(Paris, 2000)

HJAS HarvardJournalofAsiaticStudies

HPL Edward G. Browne, AHistoryofPersianLiteratureunder TartarDominion(A.D.1265–1502), A Literary History of Persia, III (Cambridge, 1920)

HS Works issued by the Hakluyt Society

HT Mirkasym Usmanov and Rafael Khakimov (eds), TheHistory oftheTatarssinceAncientTimes, 7 vols (Kazan, 2017)

IHC Islamic History and Civilization: Studies and Texts

Iran Iran.JournaloftheBritishInstituteofPersianStudies

IrSt IranianStudies

IU Islamkundliche Untersuchungen

IUUAS Indiana University Uralic and Altaic Series

JA JournalAsiatique

JAH JournalofAsianHistory

JAOS JournaloftheAmericanOrientalSociety

JESHO JournaloftheEconomicandSocialHistoryoftheOrient

JGH JournalofGlobalHistory

JNES JournalofNearEasternStudies

JPS JournalofPersianateStudies

JRAS JournaloftheRoyalAsiaticSociety

JSAI JerusalemStudiesinArabicandIslam

JSYS JournalofSong-YuanStudies

JTS JournalofTurkishStudies

JWH JournalofWorldHistory

ME MedievalEncounters

MM The Medieval Mediterranean: Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400–1453

MO ManuscriptaOrientalia

MongolicaMongolica.AnInternationalAnnualofMongolianStudies

MS MongolianStudies

MSR MamlūkStudiesReview

MTB MemoirsoftheResearchDepartmentoftheToyoBunko MuqarnasMuqarnas:AnAnnualontheVisualCulturesoftheIslamic World

NCHI, III David O. Morgan and Anthony Reid (eds), TheNew CambridgeHistoryofIslam, III: TheEasternIslamicWorld, EleventhtoEighteenthCenturies(Cambridge, 2010)

NZO NumizmatikaZolotoiOrdy

OM OrienteModerno

Orient Orient.ReportsoftheSocietyforNearEasternStudiesin Japan

PIA Papers on Inner Asia

PL C.A. Storey, PersianLiterature.ABio-bibliographicalSurvey (London, 1927–in progress)

PL2 C.A. Storey, PersianLiterature.ABio-bibliographicalSurvey, trans. and extended edn by Iu.É. Bregel' , Persidskaia literatura.Bio-bibliograficheskiiobzor, 3 vols (Moscow, 1972)

PNAS ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesofthe UnitedStatesofAmerica

QGIA Quellen zur Geschichte des islamischen Ägyptens

REMMM RevuedesMondesMusulmansetdelaMéditerranée

SEA Studies on East Asia

SOL Sammlung Orientalischer Arbeiten

SRS Silk Road Studies

StIr StudiaIranica

StIsl StudiaIslamica

TDPKV Trudydvadtsat' piatogokongressavostokovedovMoskva916avgusta1960, 5 vols (Moscow, 1963)

TMEN Gerhard Doerfer (ed.), TürkischeundmongolischeElemente imNeupersischen, 4 vols, VOK 16, 19, 20 and 21 (Wiesbaden, 1963–75)

TP T’oungPao.InternationalJournalofChineseStudies

TS TiurkologicheskiiSbornik

TSCIA Toronto Studies on Central and Inner Asia

Turcica Turcica.Revued’ÉtudesTurques

Turkestan1V.V. Bartol'd, Turkestanvépokhumongol ' kagonashestviia, 1st edn, 2 vols (St Petersburg, 1898–1900)

Turkestan3W. Barthold, TurkestandowntotheMongolInvasion, 3rd edn by C.E. Bosworth, with additional chapter trans. by T. Minorsky, GMS, n.s., 5 (London, 1968)

UAJ Ural-AltaischeJahrbücher

VOK Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur: Veröffentlichungen der orientalischen Kommission

ZAS ZentralasiatischeStudien

ZDMG ZeitschriftderDeutschenMorgenländischenGesellschaft

ZOO ZolotoordynskoeObozrenie

ZOTs ZolotoordynskaiaTsivilizatsiia

OTHER ABBREVIATIONS

Ar. Arabic

b. bin/ibn [in Arabic and Persian personal names – see above, ‘Note on Transliteration’]

BL British Library

BN Bibliothèque Nationale de France

CE Common Era

Ch. Chinese

Mo. Mongolian

Pers. Persian

RRL Rampur Raza Library

TSM Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, Istanbul

Tu. Turkish

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must begin by expressing my gratitude to Heather McCallum and Yale University Press for the enthusiastic reception they gave my book proposal; and to Heather and her colleagues Rachael Lonsdale, Lucy Buchan and Katie Urquhart for seeing the finished version through the press.

My dependence on a number of major research libraries in the UK is among the other important debts I have accumulated in writing this book, and I must record my gratitude to the staff of the British Library; the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in the University of London; the Aga Khan Library in London; the Wellcome Library; Cambridge University Library; the Needham Research Institute Library in Cambridge; the Ancient India and Iran Trust Library in Cambridge; the Bodleian Library and the Nizami Ganjevi Library in Oxford; the University of Oxford China Centre; the Kuwait Library in the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies; the John Rylands University Library of Manchester; Birmingham University Library; Edinburgh University Library; Glasgow University Library; and the National Library of Scotland.

I am especially grateful to those institutions mentioned above from which I have been permitted to borrow books under the SCONUL scheme. In the preface to my previous book I described this as an invaluable privilege. I have had even greater reason to

value it in retrospect, once the advent of Covid-19 and the suspension of SCONUL in March 2020 seriously disrupted scholarly endeavours by apparently compelling university libraries in the UK to restrict physical access to their collections to their own staff and students for almost twenty months. I appreciated all the more the readiness of some of these institutions to reopen promptly to external visitors when SCONUL was restored to life in November 2021.

Of libraries outside the UK, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France kindly supplied digitised copies of mss. Supplément persan 1278 (Shabānkāra’ī, Majma' al-ansāb), Supplément persan 1651 (Naṭanzī, Muntakhab al-tawārīkh), Arabe 1544 (al-'Aynī, 'Iqd al-jumān) and Arabe 3423 (an anonymous jung or safīna, a literary anthology containing three of Timur’s fatḥ-nāmas), and the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek a digitised version of ms. A.F. 112 (Qāyinī, Naṣā’iḥ-i Shāhrukhī). Several years ago the Universitätsbibliothek Graz provided me with a digitised copy of ms. 1221 (the Libellusde notitiaorbisof Archbishop John of Sulṭāniyya). I have also made use of work I did in the more remote past in libraries outside Western Europe: the Süleymaniye Kütüphanesi, the Nuruosmaniye Kütüphanesi and the Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, in Istanbul; and the Raza Library in Rampur, U.P., India. For the courtesy and helpfulness of the staff at all these institutions I am profoundly grateful.

I have also received invaluable help from academic colleagues. Dr. Na’ama Arom, Dr. Hannah Barker, Dr. Jonathan Brack, Dr. Konstantin Golev, Dr. Michael Hope, Dr. George Lane, Professor Charles Melville, Professor Lorenzo Pubblici, Dr. Philip Slavin, Dr. Jana Valtrová and Dr. Márton Vér kindly supplied me with references and pdf copies of articles and/or texts that were unknown or inaccessible to me. Dr. Tibor Porció was good enough to provide me with his translation of the Tibetan version of the Buddhist treatise Sitataśastra, which includes mention of plague in medieval Central Asia. In addition, I have benefited from corresponding with Dr. Monica H. Green, who has kindly shared references and forwarded publications that she had produced or encountered in connection

with her work on the Black Death, and with Dr. Nahyan Fancy, who sent me digitised copies of a ms. of Ibn Shākir’s 'Uyūn al-tawārīkh and of a printed edition of an early section of Sibt. Ibn al-Jawzī’s Mir’ātal-zamān.

Thanks are also due to the anonymous readers who some years ago responded so positively to the proposal and draft introduction that I submitted to potential publishers and those who, more recently, reported on the completed text. Their encouragement has meant a great deal to me, and their comments saved me on more than one occasion from wrong or imbalanced conclusions. It goes without saying that the responsibility for any remaining errors is exclusively mine.

As so often in the past, my wife Rebecca has been a tower of strength, accepting – and even welcoming – the encroachment of Timur and his myrmidons (not to mention his numerous enemies and victims) on our daily routine. She has read the introduction and all the chapters in successive drafts and offered comments and suggestions, despite the increasingly heavy demands made of her as someone who works within the UK’s beleaguered public services. For reasons which – I should emphasise – are quite unconnected with this last-mentioned circumstance, she has also shared with me the task of being my most stringent critic. I owe her an immense debt of gratitude.

This book is dedicated to the memory of a very good friend who was also a distinguished and widely respected scholar and indeed a household name for anyone working on (or even just interested in) the Mongol empire. His numerous publications comprise not merely what is still a much-quoted standard work on the Mongols more than thirty years after its first appearance (1986; second edition, 2007), and a history of medieval Persia (1988; second edition, 2016), but a pioneering article entitled ‘The empire of Tamerlane: An unsuccessful re-run of the Mongol empire?’ (2000), which addresses some of the themes explored in this book. His death in October 2019 was a heavy blow to a great many of us.

Madeley, Staffordshire, May 2023

INTRODUCTION

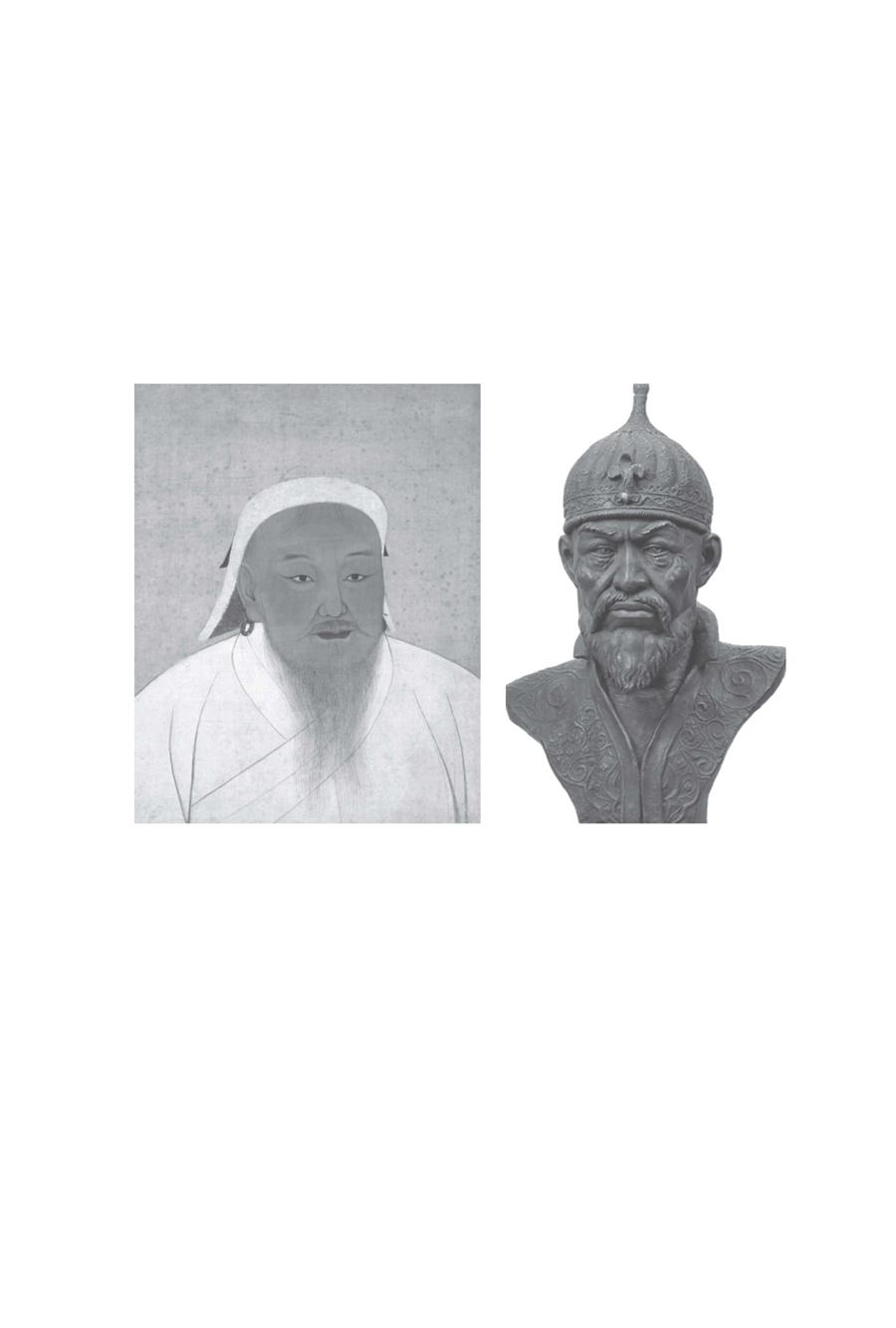

The title page is the last occasion in this book when the names of the two conquerors appear in that guise without qualification. ‘Genghis’ is a bastardised spelling with a convoluted pedigree that goes back to a faulty transcription of the title in the early eighteenth century. The founder of the Mongol empire (d. 1227), whose personal name was Temüjin, will appear here as ‘Chinggis Khan’ in accordance with the Mongolian spelling (rendered in Persian texts as ‘Chingīz’). ‘Tamerlane’ is a European corruption of Temür-i lang (‘Temür the Lame’, in Persian; the Turkish equivalent is AksakTemir). This was the usage – from wounds he had suffered to his right leg and right arm in his youth – under which he was immortalised by those writing outside his dominions. It was well embedded by the time Marlowe published his famous play in two parts, Tamburlaine the Great (1590; part I first performed in 1587). In preference to ‘Temür’, a common Turco-Mongolian name (meaning ‘iron’), I have adopted ‘Timur’, as the spelling found in Persian and Arabic sources and more often than not reproduced in the secondary literature. My aim is to avoid confusion with the many other persons in this book who bore the name either singly or in compound form, and in relation to whom I employ the spelling Temür.

Timur (d. 807/1405), a member of the Turco-Mongol Barlās tribe, was born in Transoxiana (Ar.-Pers. Mā warā’ al-nahr, ‘what lies beyond the river [Oxus]’), within a world irreversibly shaped by the

Mongols (or ‘Tatars’, as they were often known) and which still lay under Chinggis Khan’s shadow. At one level, and particularly from an Iranian vantage point, he represented, as the Mongols had done, the forces of ‘Turan’ – the vast tract beyond the Oxus (Ar.-Pers. Amūdaryā) – that traditionally had long posed a threat to Iran and the Near East, a menace encapsulated in the Iranian epic Shāh-nāmaof the eleventh-century author Firdawsī. As the last Turanian or Inner Asian conqueror at the head of a nomadic cavalry to forge a truly trans-regional empire, he did more than simply partake of the Mongols’ legacy. He appears to have tried both to transcend and to perpetuate the Mongol achievement. During a series of expeditions spanning over three decades, he humbled not merely Mongol rulers descended from Chinggis Khan but the Sultan of Delhi, the Mamlūk Sultan of Egypt and Syria, the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid and a host of lesser princes. At his death, having already carved out a realm that stretched from Anatolia and Syria to the Punjab and the borders of present-day Xinjiang, he was on the point of heading an invasion of Ming China. As a commoner lacking Chinggisid ancestry, he did not reign officially over his conquests, but governed them in the name of a shadow khan of Chinggisid descent, himself accepting the ArabicPersian title of Amir, ‘Commander’, or its Turkish equivalent, Beg, or sometimes ‘Great Amir’.

Unlike Chinggis Khan, but in common with a great many of the Mongol conqueror’s fourteenth-century descendants, Timur was a Muslim – one reason, perhaps, why he tends to emerge unfavourably from the almost inevitable comparisons with Chinggis Khan, who could be excused his excesses as a mere infidel.1 Timur drew on a range of traditions, Islamic as well as Mongolian, to define and justify his rule: to exercise, as one modern author puts it, ‘a cultural ambidexterity of sorts’.2 And whether or not one sees his espousal of jihād as springing from sincere religious conviction, his wars against the unbeliever – and against those he denounced as ‘bad’ Muslims – produced a greater sensation, and had a more powerful impact, than the campaigns of any Muslim Mongol ruler before him.

TWO EMPIRES

The world in which Timur was active, well over a century after Chinggis Khan’s death, had undergone significant political and social changes, of which Islamisation was only one of the most conspicuous. The unitary Mongol empire had long since ceased to be a reality. Chinggis Khan had allotted a specific territory and population (or ulus, to use the Mongolian term for such an amalgam; its modern meaning is ‘state’) to each of his sons and to other members of his family. But in the course of a civil war between rival candidates for the dignity of Great Khan (Qaghan) in the early 1260s, the empire had fragmented so that the principal uluses formed autonomous states. The western steppes were home to at least two such polities, ruled by the progeny of Chinggis Khan’s eldest son Jochi, the foremost being the Qipchaq khanate (frequently designated as the ‘Golden Horde’), centred on the Volga and the Crimea. The descendants of the second son, Chaghadai, ruled in Transoxiana and Turkestan (corresponding today to most of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, south-eastern Kazakhstan and western Xinjiang). The other two principal states both came to be governed by rulers from the line of Chinggis Khan’s fourth son Tolui. The Qaghan’s dominions – the ‘Great Khanate’, or the Yuan Empire as it is known – comprised China, Mongolia, Manchuria and parts of Tibet; the Ilkhanate embraced present-day Iran, part of Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, the Caucasus and most of Anatolia. By Timur’s day, however, the Ilkhanate had dissolved and its territories had passed into the hands of regional rulers, frequently of Iranian stock, while the Yuan dynasty was expelled from China in 1368 and supplanted by the native Ming. The Chinggisid states had already begun to follow different cultural trajectories. The majority of the nomadic populations of the western Mongol khanates – unlike the Yuan dominions – were ethnically Turks. And whereas Buddhism predominated under the Yuan, the nomads of Western and Central Asia were steadily Islamised. The Ilkhans had adopted Islam definitively in 1295; in the Jochid territories and the Chaghadayid state the khans had done so by the 1340s.

Although it now seems a trifle inappropriate to regard Timur as inaugurating the ‘second phase’ of the Mongol empire, as implicit in the title of a book published almost a century ago,3 the idea that he was trying to recreate Chinggis Khan’s empire is still widespread. This too is emphatically not beyond question, though it cannot be denied that Timur often acted in such a way as to evoke Chinggis Khan’s memory. We might be tempted to subscribe to a recent definition of Timur’s dominions as ‘in effect, a neo-Mongol empire’.4 He was of Mongol descent (although his ancestors almost certainly included Turks, and Turkish appears to have been his native language). If he did not follow, strictly speaking, a nomadic lifestyle,5 the core of his army nevertheless comprised mounted nomad archers, just as had the Mongol forces; the khans he professed to serve were Chinggisid princes; and Mongol law and custom still played an important part in his governance. The formulation, accordingly, is by no means inapposite, provided we bear in mind two circumstances.

First, Timur’s world differed geographically and spatially from that of the Mongols. His incessant military operations did not span so vast an area. Though his capture of Delhi represented a triumph that had eluded them, and his troops penetrated as deeply as theirs into Syria and Anatolia, his conquests on other fronts were less impressive. The Mongol empire has been described as ‘the largest continuous land empire that has so far existed’.6 Timur’s domain encompassed only a fraction of that empire – a very large fraction, to be sure, but far from the entirety of the Chinggisid conquests.7 Its kernel was not the original Mongolian homeland but Central Asia, and in particular the land north of the Amū-daryā (Oxus) and extending as far as, or beyond, the Sīr-daryā (Jaxartes River): Transoxiana, the western part of the territory that Chinggis Khan had bequeathed to Chaghadai. Here pasturelands were interspersed with regions centred on irrigation agriculture and wealthy towns like Samarkand and Bukhara, and Turkish nomadic groups and Persianspeaking (‘Tājīk’) sedentary communities, while remaining distinct, had lived in close proximity since the pre-Mongol era – a proximity

reinforced by the nomads’ acceptance of Islam. Even though the urban dweller and the cultivator feared the nomad’s martial prowess and despised him as boorish and ignorant, while the nomad remained wary of seduction by sedentary culture and a consequential loss of military effectiveness, the relationship was one of symbiosis.8 This was a distinctive cultural area. It is symptomatic of the well-established fissures within the Chinggisid world that Timur and his nomadic troops were known to their contemporaries –and referred to themselves – as ‘Chaghatays’ more commonly than as Mongols or Tatars.

Second, Timur’s empire thus contrasted sharply with that of the Mongols in its ecological and cultural orientation. Although he sprang from a nomadic tribe, he drew above all on the resources of sedentary territories and did not aspire to rule over the steppelands, even those that had been subject to Chinggis Khan and his successors (with the exception of certain regions immediately east of Transoxiana).9 Timur’s principal residence, and the ultimate destination of much of the plunder he amassed on his campaigns, was the venerable city of Samarkand, and he evinced a strong attachment also to his birthplace, the town of Kish (later Shahr-i Sabz) in the valley of the Qashqa-daryā, likewise in Transoxiana. His dominions were far more homogeneous, in cultural terms, than Chinggis Khan’s empire, comprising as they did territories that had not only been more or less Islamised but were in large measure coterminous with the Persianate world.10

TIMUR IN MODERN EUROPEAN WRITING

The reader who seeks to learn about Chinggis Khan and the empire he created is truly assailed by an embarras de choix. Well over twenty biographies of varying quality have appeared in English alone since the early nineteenth century,11 and probably at least as many books on the Mongol empire. Work on Timur began to emerge rather later, and at first in studies with a different remit, like Barthold’s book on Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg.12 It was no

coincidence that the earliest solid academic essay devoted to Timur in his own right, ‘a short sketch’ by the veteran Russian Mongolist Iakubovskii in 1946,13 appeared in the wake of the opening of the conqueror’s tomb in Samarkand on Stalin’s orders by the archaeologist M.M. Gerasimov in 1941, just a few days before the invasion of the Soviet Union by the forces of Nazi Germany. It is to the forensic reconstruction of Timur’s physiognomy that we owe the familiar image found in a number of works, notably on the jacket of Hookham’s TamburlainetheConqueror(see below).

Timur – or rather his triumph over the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid in 1402 – has been the subject of drama, within which Marlowe’s work was both the most celebrated and the inspiration for others, and of opera, notably those by Handel (Tamerlano, 1724), Gasparini (Tamerlano, 1711; rewritten as Bajazet, 1713) and Vivaldi (Bajazet, 1735, alternatively called IlTamerlano).14 He can be said (at the risk of placing an intolerable strain on the weakest of metaphors) to have lent his name to verse by Edgar Allan Poe (in TamerlaneandOther Poems, 1827) – not to mention the 1970s New Zealand rock group Tamburlaine. Chinggis Khan has been denied any such tributes. Yet it is likely that fewer people know anything of the historical Timur, albeit a towering figure in his own right, than of Chinggis Khan.15 Were it not for Marlowe, the numbers would surely have been still lower.

Additionally, Timur has attracted fewer book-length studies than has Chinggis Khan. Only three of these works have an unimpeachable claim to academic rigour, with a full scholarly apparatus of references. The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane, by Beatrice Manz, is a first-rate investigation, thoroughly grounded in the sources, of Timur’s rise, the means by which he gained power and kept it and the administration of his far-flung conquests. My immense debt to Rise and Rule, as also to Manz’s numerous other publications, will be apparent to anyone who reads the chapters that follow. The second book, Tilman Nagel’s Timur der Eroberer, is an admirable attempt to situate Timur in the broadest of contexts: that of the late medieval Islamic world and its ideas, a world peopled by