Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Ecue-Yamba-O is made possible with the support of the Knight Foundation, Oolite Arts, Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs, and supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Table of Contents

2 3. Acknowledgements 4. ESSAYS 4. The

7.

9. Ecue-Yamba-O

40. ENSAYOS 45. BIOGRAPHY

Poetics of Fashion and Body Differences CHARO OQUET

Charo Oquet’s artistic tensions: A language for these times YOLANDA WOOD

photos CHARO OQUET

CHARO OQUET

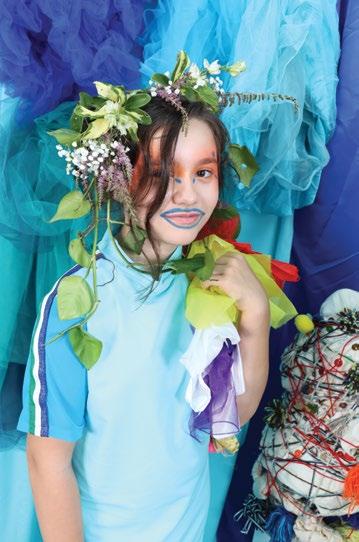

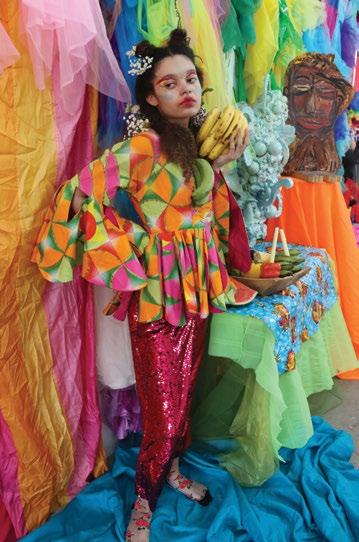

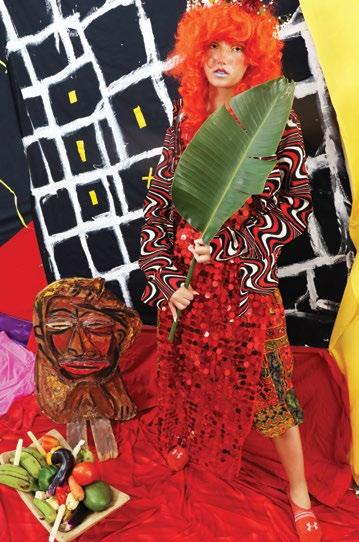

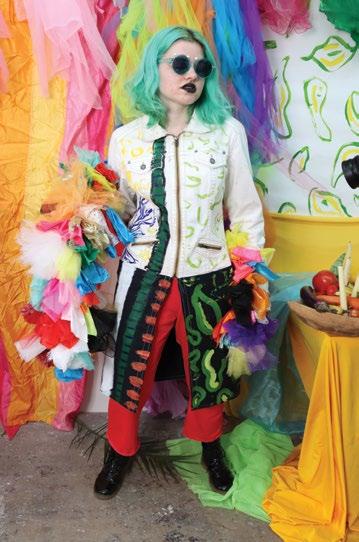

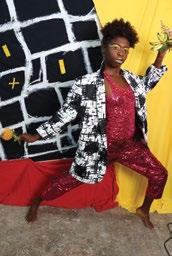

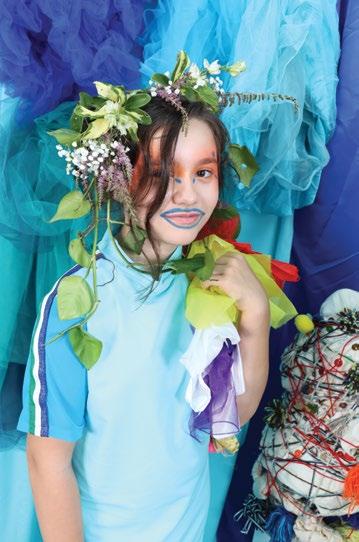

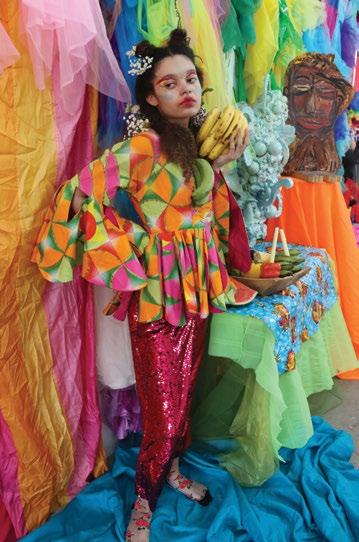

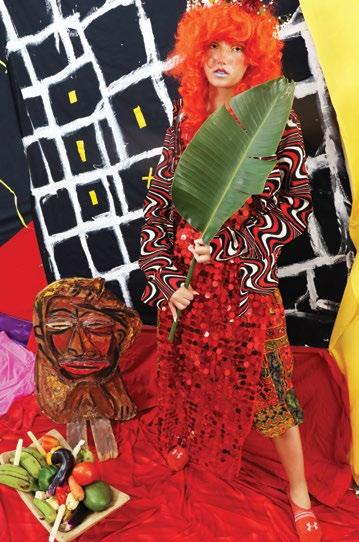

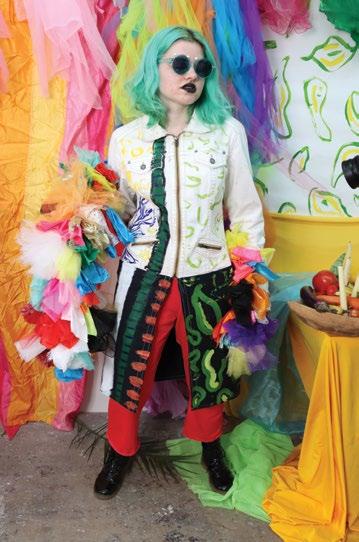

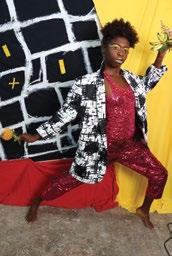

“Ecue-Yamba-O” is a Charo Oquet Project. “Ecue-Yamba-O” is a multimedia project which explores Afro-Caribbean design through immersive fashion, art, and performance to explore identity and healing, uplifting and re-edifying distressed bodies through a visual and aural feast featuring handmade garments. The multi-media exhibition and workshops took place at Edge Zones Art Center, in Allapattah, Miami, FL. “Ecue-Yamba-O” uses fashion, art, video, and performance to explore identity and healing through a visual feast. Working with a team of artists and students, to build garments and accessories. and design as a powerful medium to celebrate the richness of contemporary Afro-syncretic creativity. It foregrounded the Afro-Caribbean roots of Miami’s Latinx diasporic culture through art and design presented in an immersive environment in a series of events that celebrate and recognize African diasporic traditions in vernacular culture, reclaiming fashion, beauty, and design as tools of resistance instead of consumerism and assimilation.

First Edition: 2022 Charo Oquet

Acknowledgment

I want to thank all of the people who made this project possible through their participation in Ecue-Yamba-O project as, photographers, make-up artist, stylist, fabricators, designers, filmmakers and installers, photographer assistant and Coordinator: Gabriela Keddell, Gregorio Alvarez William Keddell, Robert Gil, Lillian Shaleesh, Claudia Ariano, Izabela Cookson , Nathan Campos, Isabella Mendoza, Dannae Cuenca and Jason Morrison. Our models where students mostly from, Design and Architecture Sr. High, Miami Arts Charter and Dr. Michael M. Krop Senior High, Ramson Everglades School: Zipporah Hinds, Jade Peraza, Alexis Nicoleau, Isabella Sanchez, Leah Llenaoux, Eseer Curtis, Tamina Simons, Narah Deeb, Lory Charles , Ella Estrella, Vera Ramirez, Marco Tulio Rivera Rosa, Charlene Francoise, Nina Vara, Kamilla Polese, Jorja Corporan, Aeon Morales, Jennifer Parra, Arielle Morales, Arianna Sanchez, Samantha Valdes, Alina Melfi, Abel Reyes,

Contributors

Seaming: Abel Reyes, Juan Beltre, Diamond Gabriel, Maite Collection, Robert Gil Makeup: Isabella Mendoza, Izabela Cookson Jewelry, Photography & clothing design: Charo Oquet |Photography Students: Lillian Shaleesh, Nathan Campos

Production Assistant: Zipporah Hinds , Dannee Cuenca, Jason Morrison, Juan Ayala Photography Assistant: Juan Ayala Videography/Video Editing: Vidium Styling /Hair: Robert Gil , Zipporah Hinds, Claudia Ariano, Abel Reyes, Gabriela Keddell, Vera Ramirez. Design and Layout: Manny Prieres Design coordination: Rafael Vargas Bernard

3

The Poetics of Fashion and Body Differences Charo Oquet

The pandemic began as I received a grant to work on my Ecue-Yamba-O fashion project. The work was concerned with the body, and clothing – and the worldwide crisis brough these topics into new focus. As coronavirus spread throughout the world, the body became a dangerous weapon that could kill us. Bodies were restricted, secluded and excluded. We could no longer socialize physically; we had to keep distance and remain in our homes.

Three years later, and the recent Supreme Court ruling that overturned the Roe v. Wade judgmentwhich guaranteed women’s access to abortion in the United States - has again placed the body at the cen ter of our lives. There is a new fight for its control.

In these times, recontextualized clothing, dress and adornment, play a key role as a form of expression of our bodies. They are tools of empowerment and subversion, communicating identity, and command ing respect.

The Ecue-Yamba-O fashion project is an investigation of bodies that celebrate higher entities using peace and joy. I call “higher” the sacred and ancient forces that live in myths, and are figures of light. My per formance work proposes beautiful and mysterious bodies, that are an invitation to be discovered.

My Ecue-Yamba-O project celebrates how BIPOC and LTBG+ bodies show resilience, offering strength in the face of adversity. It explores joyful affirmation and self-love, documenting intimacy and indomita bility.

This project is the culmination of a lifetime’s inter est. I have been a migrant in various countries and

cities throughout my life. As a child, my parents were exiled from the Dominican Republic and we moved to New Jersey. I transformed from an upper middle-class daughter, to the member of a work ing-class family, with parents that worked in facto ries, and did not even speak English. My siblings and I had fit in, quickly.

Once we returned to the Dominican Republic years later, I had to adapt again because, at the expensive prep school I was enrolled in, my working-class En glish set me apart. In both cases clothing helped me code switch. As I grew older, I would design amazing dresses by copying high couture fashion I found in European and American magazines – helping me to fit in with my peers.

Since the beginning of my career as an artist, I have centered my work and research on the historical and present-day connections between Indigenous and African communities in the Americas, and the effects of forced migration, exploitation, genocide, slavery, on-going evolution, inventions, and shifts in culture, visual art and language.

I have used clothing as an instrument with which to connect the past with my present and the future, an energy that is essential to my work. During my years of art practice in New Zealand in the 1980s, I began to produce photo-performances wearing clothing that took me back to my Dominican roots. Once in Miami, during the 1990’s, I created installations that served as backdrops to my photo performances,

4

where I would wear eltaborate dresses and crowns in a style connected to the Afro-Caribbean and Bra zilian voodoo priestess.

I have always felt that wearing certain clothing helped me create my performances and believe that my garments are transmitters of the creative energy that flows through my body. In my clothing, I have made use of the palette and patterns I have found in my research, exploring the interaction of materials and designs, to give them new meaning. The photos of my performances have been exhibited in several spaces, including a show in Barcelona (2001) at the Galeria Senda, Espai 292. during the exhibition, titled Mermaid Song (Canto de Sirena).

Among my works I also give great importance to the aesthetic and spiritual dynamics of the festive Dominican/Haitian Gaga/Rara carnival tradition, which has common heritage with Afro-Cuban and African-American carnival traditions.

My garments are not only tied to Afro-religious imagery - they also connect to my indigenous roots, drawing on figures like the Heyoke, the sacred clown – who is also connected to Elegua, the Orisha deity of the crossroads.

In Rara, participants wear hats and collars that are full of shining objects. Bows, beads, and brightly colored ornaments that shine in the sun are worn to seduce the gods. The skirts worn by the Mayores, or Majors, are made up of many scarves of different colors, that represent the deity that they serve. The

5

Mermaid Song (Canto de Sirena) installation/ performance, Galeria Senda,, Barcelona, Spain 2001

Rituals and Syncretism, Española Way Arts Center, Miami Beach, FL 1998. The Kingdom of our World, installation/ performance Coral Gables, FL, Ambrosino Gallery, 1999

Miami Beach Rara processional performance, Lummus Park, Miami Beach, FL 2019 Photo: Greg Alvarez

Miami Rara processional performance, Institute of Contemporary Art of Miami (ICA), Miami, FL2017 photo Javier de Pisón

garments are blessed and kept hidden, only to be revealed when their procession begins, a form of marking or mapping of territories that will allow the pilgrims to become present and visible in areas that are usually forbidden to them.

In my practice, I make necklaces that are similar to the Rara collars. They also resemble Paquet congo, Haitian spiritual objects made by vodun priests and priestesses, a collection of magical ingredientsherbs, earth, vegetable matter- wrapped in fabric and decorated with feathers, ribbons and sequins. Paquet Congo serve as power objects

This project has also inspired me to collaborate with a group of artists who challenge, and engage with fashion and its subversive characteristics, reflect ing a BIPOC point of view. It fueled my interest in exploring how each artists’ work engages with the others - suggesting alternative uses of fashion that traverse our present, disseminate future forms of knowledge, center collective healing, and forge new vocabularies which stake our claim to our place in society.

What is beautiful has always been in the eye of the beholder: beauty has historically been defined as a denial of what is different – the sources of hostile reactions, violent repulsions, fear, and even terror. The knowledge of this led me to search for dissident fashion that seeks to identify and analyze the rela tionship between fashion and otherness - everyday expressions that re-signify the ugly and, at the same time, highlight the logic and constructions of contemporary society. This project seeks to examine the relationship between fashion and power, and to question its scope in current local and global culture. This conversation will continue on - so, the end of this project is just the beginning of another –of a broader and more inclusive project, in which we come together with others to explore and celebrate.

and are kept on Vodum altars to be used in healing ceremonies. They are also used as protective amu lets in people’s homes that bring health, wealth and happiness.

Many years of making garments and necklaces has taught me that my interest in fashion is not that of marking clothes and selling them, but rather wearing them and celebrating the works of others who also create garments and adornments to mark spaces, to become visible. I want to show that clothing can be a tool of resistance, that it can help you navigate and subvert a difficult system created to keep you in place and invisible, allowing you to code switch in such spaces.

6

Every People – Multi-Media exhibition ,Edge Zones Gallery, Miami, Fl, 2021

Charo Oquet’s artistic tensions: A language for these times Yolanda Wood

Artworks tend to reflect contemporary nuance and tensions, and in Charo Oquet’s work these bursts through with great force, the result of creation in a powerful triangular space, defined by an imaginary shape linking the Greater Antilles and the southern United States.

In this part of the world, we are accustomed to critical triangulations - that of the Bermudas, to mention a geographical example. The configuration where Charo Oquet’s artistic tensions are located have their apex in Miami, where the artist lives. The foundation of this symbolic triangle is the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic - the latter is where Charo was born. Emerging between these socio-cultural coordinates is the work of an artist distinguished by its conceptual maturity and a very personal artistic approach within the current landscape of the Caribbean.

and in dialogue with spectators. The treatment of recycled materials in her installations, for example, is located in a triangle of tension where the com mon definition of the objects is modified. Charo’s work using these materials situates them between dazzling Miami accumulation and alluring consumer ism, and the bases of her triangle – Haiti and the Do minican Republic - where the use and reuse of the already-used becomes part of the everyday world of domestic poverty and informal market.

The artist revisits these universes and operatesconsciously - with her artistic materials, with all the energy that they preserved, with the tactile memory which they carry in mind. This is how she throws herself into the mysterious journey of the imagina tion with surprising creative capacity. By employing what overflows in Miami’s flea markets - clothes, stuffed animals - and relocating them, values are reversed to evoke their opposites in the field of insecurity and deterioration. The artist provokes a magical reallocation of meaning between the ‘here’ and ‘there’ of this triangle – with all the implications this has on its north-south axis in the global world.

In Charo’s assemblies, she is interested in the ways use of objects and other resources can shift their original meanings – allowing them to acquire new values through artistic manipulation. These new meanings form not only from the creative process itself, but also by their new functions - aesthetic and communicative - that are established in context,

7

Miami Rara, processional performance, Institute of Contemporary Art of Miami (ICA), Miami, FL2017 photo Javier de Pisón

Miami Flyers, Here and Now Festival ,Miami Light Project, Miami, Fl, 2016

The forces of ancestral African divinities also feature in this zone of tension. Spiritual beings have trav eled with the Antillian diasporas, in both their legal and illegal migrations, creating a cultural geography. People have carried their universes of reference in their imaginations, and they are present, in a space to be received. The artist appropriates these values and is immersed in the theatricality of performance; her body is covered with symbolic clothing. After the act - with its transvestisms and configurations - a liberating subject is constructed, emancipatory for spirits and investigative of gender identity through a legitimization of certain female roles and their ways of seeing and understanding the world, through a mythical universe.

This journey, in an area of contact with supernatural forces, generates a sensitive place of solemn spiritu ality in Charo’s work that comes from popular culture

Charo shows a deep connection to her country of origin and its conflicts, including contemporary political and social issues, such as the territorial and border limits within the interior of the island, and its impact and significance in the racial and cultural imaginary of the two sides. Charo does not evade these circumstances and she involves herself; this is why her work transcends and remains in the critical area of the triangle. Her art does not neglect the persistent presence of memory as an essential quality in the complexity of the language of the times.

Mexico City, September 30, 2015

8

Engungu in White – A celebration of our ancestors and a community spiritual cleaning, Be.Bop European Body Politics , Spiritual Revo lutions & the Scramble for Africa: Nikolaj Kunsthal, Copenhagen, Denmark , 2014

Cuatro Vientos (Four Winds), residency and performance, ACCIONArar, Anolaima, Colombia, 2016 photo: Tzitzi Barrantes

Ecue-Yamba-O

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

Texto en Español/Spanish Text

40

La Poética del Vestir y las Diferencias de Cuerpos Charo Oquet

La pandemia comenzó cuando recibí una subvención para trabajar en mi proyecto de moda Ecue-Yam ba-O.

El trabajo se centró en el cuerpo y la ropa, y la crisis mundial trajo estos temas a un nuevo enfoque. A medida que el coronavirus se extendía por todo el mundo, el cuerpo se convirtió en un arma peligrosa que podría matarnos. Los cuerpos fueron restringi dos, aislados y excluidos. Ya no podíamos socializar físicamente; teníamos que mantener la distancia y permanecer en nuestras casas.

Tres años después, y el reciente fallo de la Corte Suprema que revocó la sentencia Roe vs. Wade , que garantizó el acceso de las mujeres al aborto en los Estados Unidos , ha vuelto a colocar al cuerpo en el centro de nuestras vidas. Hay una nueva lucha por su control.

En estos tiempos, la vestimenta, el vestido y el adorno recontextualizados, juegan un papel clave como forma de expresión de nuestros cuerpos. Son herramientas de empoderamiento y subversión, de comunicación de identidad y de imponer respeto.

El proyecto de moda Ecue-Yamba-O es una investi gación de cuerpos que celebran entidades superi ores utilizando la paz y la alegría. Llamo “superiores” a las fuerzas sagradas y antiguas que viven en mitos, y son figuras de luz. Mi trabajo de performance propone cuerpos hermosos y misteriosos, que son una invitación a ser descubiertos.

El proyecto Ecue-Yamba-O celebra cómo los cuerpos BIPOC y LTBG+ muestran resiliencia, ofreciendo for taleza frente a la adversidad. Explora la afirmación alegre y el amor propio, documentando la intimidad y la indomabilidad.

Este proyecto es la culminación del interés de toda una vida. He sido migrante en varios países y ciudades a lo largo de mi vida. Cuando era niña, mis

padres se exiliaron de la República Dominicana y nos mudamos a Nueva Jersey, E.E.U.U. Me transformé de una hija de clase media alta, a miembro de la clase obrera, con padres que trabajaban en fábricas y ni siquiera hablaban inglés. Mis hermanas y yo nos adaptamos, rápidamente.

Una vez que regresamos a la República Dominicana años más tarde, tuve que adaptarme nuevamente porque, en la costosa escuela preparatoria en la que estaba inscrita, mi inglés de clase obrera me distin guió. En ambos casos, la ropa me ayudó a cambiar el código. A medida que crecía, diseñaba vestidos increíbles copiando la moda de alta costura que encontraba en revistas europeas y estadounidenses, ayudándome a encajar con mis compañeros.

Desde el comienzo de mi carrera como artista, he centrado mi trabajo e investigación en las conex iones históricas y actuales entre las comunidades indígenas y africanas en las Américas, y los efectos de la migración forzada, la explotación, el genocidio, la esclavitud, la evolución en curso, las invenciones y los cambios en la cultura, el arte visual y el lenguaje.

He utilizado la ropa como instrumento con el que conectar el pasado con mi presente y el futuro, una energía que es esencial para mi trabajo. Durante mis años de práctica artística en Nueva Zelanda en la década de 1980, comencé a producir fotográficas performáticas con ropa que me llevó de vuelta a mis raíces dominicanas. Una vez en Miami, durante la década de 1990, creé instalaciones que sirvieron como telón de fondo para mis fotográficas per formáticas, donde usaba vestidos y coronas elabora das en un estilo conectado con la sacerdotisa vudú afrocaribeña y brasileña.

Siempre he sentido que usar cierta ropa me ayudó a crear mi performance y creo que mis prendas son transmisoras de la energía creativa que fluye a través de mi cuerpo. En mi ropa, he hecho uso de la paleta y los patrones que he encontrado en mi investigación, explorando la interacción de materia les y diseños, para darles un nuevo significado. Las fotos de mis performances han sido expuestas en varios espacios, incluyendo una muestra en Barcelo na (2001) en la Galeria Senda, Espai 292. durante la exposición, titulada Canto de Sirena.

41

Mis prendas no solo están ligadas a la imaginería afrorreligiosa, sino que también se conectan con mis raíces indígenas, recurriendo a figuras como el Heyoke, el payaso sagrado, que también está conectado con Elegua, la deidad Orisha de la encru cijada.

Entre mis obras también doy gran importancia a la dinámica estética y espiritual de la tradición festiva del carnaval dominicano/haitiano Gaga/Rara, que tiene herencia común con las tradiciones carnavales cas afrocubanas y afroamericanas.

En Rara, los participantes usan sombreros y collares que están llenos de objetos brillantes. Lazos, cuentas y adornos de colores brillantes que brillan al sol se usan para seducir a los dioses. Las faldas que usan los mayores, están formadas por muchas bufandas de diferentes colores, que representan a la deidad a la que sirven. Las prendas son bende cidas y mantenidas ocultas, solo para ser reveladas cuando comienza su procesión, una forma de mar caje o el mapeo de territorios que permitirá a los peregrinos hacerse presentes y visibles en áreas que generalmente están prohibidas para ellos.

En mi práctica, hago collares que son similares a los collares Rara. También se asemejan a Paquet Congo, objetos espirituales haitianos hechos por sacerdotes y sacerdotisas Vodúm, una colección de ingredientes mágicos -hierbas, tierra, materia vegetal- envueltos en tela y decorados con plumas, cintas y lentejuelas. Paquet congo sirven como objetos de poder y se mantienen en altares vodum para ser utilizados en ceremonias de curación. También se utilizan como amuletos protectores en los hogares de las personas que aportan salud, riqueza y felicidad.

Muchos años haciendo prendas y collares me han enseñado que mi interés por la moda no es el de marcar la ropa y venderla, sino más bien llevarla y celebrar los trabajos de otros que también crean prendas y adornos para marcar espacios, para hac erse visibles. Quiero mostrar que la ropa puede ser una herramienta de resistencia, que puede ayudarte a navegar y subvertir un sistema difícil creado para mantenerte en su lugar e invisible, permitiéndote cambiar de código en tales espacios.

Este proyecto también me ha inspirado a colaborar con un grupo de artistas que desafían y se involu cran con la moda y sus características subversivas, reflejando un punto de vista BIPOC. Alimentó mi interés en explorar cómo el trabajo de cada artista se relaciona con los demás, sugiriendo usos alterna tivos de la moda que atraviesan nuestro presente, difunden formas futuras de conocimiento, centran la curación colectiva y forjan nuevos vocabularios que apuestan por nuestro lugar en la sociedad.

Lo que es bello siempre ha estado en el ojo del espectador: la belleza se ha definido históricamente como una negación de lo que es diferente, la fuente de reacciones hostiles, repulsiones violentas, miedo e incluso terror. El conocimiento de esto me llevó a buscar moda disidente que busque identificar y analizar la relación entre moda y alteridad, expre siones cotidianas que resignifican lo feo y, al mismo tiempo, resaltan la lógica y las construcciones de la sociedad contemporánea. Este proyecto busca examinar la relación entre la religióny el poder, y cuestionar su alcance en la cultura local y global actual. Esta conversación continuará - so, el final de este proyecto es solo el comienzo de otro - de un proyecto más amplio e inclusivo, en el que nos reunimos con otros para explorar y celebrar.

42

Las tensiones artísticas de Charo Oquet: lenguaje de estos tiempos Yolanda Wood

La inquietud contemporánea adquiere todos los matices y tensiones en las obras de los artistas de la región, pero en la de Charo Oquet irrumpen con fuerza mayor por su propia existencia dentro de un potente espacio triangular, definido por un trazo imaginario sobre las Antillas Mayores y el sur de los Estados Unidos. Habituados como estamos en esta parte del mundo a las triangulaciones críticas, la de Las Bermudas por ejemplo por solo mencionar las geográficas; la configuración donde se sitúan las tensiones artísticas de su obra, han desplazado en algunos grados el equilátero para mantener su vértice en Miami, donde reside la artista, y colocar la base de esa figura simbólica en la isla compartida por Haití y República Dominicana, tierra –esta última - donde Charo nació. Surgida en esas coordenadas socio-culturales, la obra de la artista se distingue por su madurez conceptual y por un laboreo artísti co muy personal dentro del panorama actual del Caribe.

Interesa en sus ensamblajes, el uso de objetos y otros recursos que desplazan sus significados orig inales y adquieren nuevos valores en la trayectoria humanizada de su manipulación artística, no solo como parte misma del proceso creador sino también por las nuevas funciones - estéticas y comunicativas - que establecen en el espacio y con los espectado res. El manejo del reciclaje en sus instalaciones, está auténticamente situado en ese triángulo de ten siones donde se modifica la definición común de los objetos. Desde una mirada cruzada, su obra se sitúa entre el Miami de la deslumbrante acumulación y el atrayente consumismo, y las bases del triángulo donde el uso y re-uso de lo ya usado forma parte del mundo cotidiano de la pobreza doméstica y del mercado informal.

La artista revisita esos universos y opera – consci entemente - con las cargas de sus medios artísticos, con todas las energías que conservan, con la memo ria de la que son portadores. Así se lanza al miste rioso viaje de la imaginación con una sorprendente capacidad creadora. Al emplear lo que en Miami se desborda en los pulgueros: ropas, peluches…, y re situarlos en sus estructuras visuales, se invierten sus valores para evocar – críticamente - a sus opuestos

en el ámbito de la precariedad y el deterioro. Una reinversión mágica de sentido entre el aquí y el allá de ese triángulo de fuerzas que la artista maneja a su antojo, situado en un eje norte-sur con todas sus implicaciones en el mundo global.

En esa zona de tensión circulan también las ances trales fuerzas de las divinidades venidas de África. Con las diásporas antillanas, en sus desplazamientos legales e ilegales, han viajado los seres espirituales de todos los que desde las islas los transportaron consigo, en esa geografía, no física, sino cultural. La gente se ha llevado sus imaginarios, sus universos de referencia, y ellos están allí, en el espacio de recepción. La artista se apropia de esos valores e inmersa en la teatralidad del performance, su cuer po se cubre de vestimentas simbólicas y tras el acto - con sus travestismos y figuraciones -, se construye un momento liberador del sujeto, emancipatorio para los espíritus, indagatorio sobre la identidad de género al legitimar ciertos roles femeninos en sus formas de ver y entender el mundo proveniente de ese universo mítico. El viaje de estas creencias si bien resulta un espacio de contacto con las fuerzas sobrenaturales, genera un lugar de solemne espiri tualidad muy sensible en sus obras que emana de la cultura popular.

Charo muestra una profunda conexión con su país de origen y sus conflictos contemporáneos con sus problemáticas políticas y sociales, entre ellas, la territorialidad y los límites fronterizos al interior de la isla compartida por su impacto y significación en los imaginarios raciales y culturales de los dos lados del margen. Charo no evade estas circunstancias y se implica, por eso su obra trasciende, y permanece en la zona crítica del triángulo, con su arte compro metido que no descuida la tenaz presencia de la memoria como cualidad esencial en la complejidad del lenguaje de estos tiempos.

Ciudad de México, 30 de septiembre de 2015

43

44

Charo Oquet (b. 1952, Dominican Republic)

Working across multiple media, Charo Oquet is one of the leading Miami artists of her generation, with a body of work characterized by cultural reflection, historical research, and formally involving aspects of visual art, video, music, fashion, dance, and performance. Oquet’s art practice includes community activism, curating, and creating projects and platforms with hundreds of artists in the U.S. and internationally. She founded Edge Zones Projects in 2004, The Miami Performance International Festival ‘12, Index–Miami/Santo Domingo ’11, and Zones Contemporary Art Fair ’06-11. Oquet has exhibited, performed, curated, and lectured worldwide since 1981 and is known for her dynamic installations, incorporating idioms of prevalent Afro-Caribbean religions. Recent exhibitions include Entering Sacred Grounds, Institute of Contemporary Art of Miami (ICA), Miami, FL; The XIII Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba; Relational Undercurrents, Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago; and Pacific Standard Time: LA/ LA, Museum of Latin American Art Frost Art Museum. Oquet’s work is in several museum collections, such as the Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art; Frost Art Museum, Florida International University, Miami, FL; Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Las Palmas de Gran Canarias, Spain; Bass Museum of Art, Miami Beach, Florida; New Zealand National Museum, Wellington, N.Z.; Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, New Zealand; Foresight Collection, Auckland, New Zealand; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wellington, New Zealand; Gulf & Western Americas Corp., New York; Museo de las Casas Reales, Dominican Republic and Museo del Arte Moderno, Dominican Republic. Oquet received Ellies Creator Award 2020; Knight Challenge Grant ’19, Perez Family Foundation Create ’19, NALAC ’19, SF Cultural Consortium Visual Fellowship 15; MAP Fund‘15; National Performance Network ‘11; and Dominican Biennial, Museum of Modern Art of Santo Domingo ‘11. Oquet’s work is in collections of the Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Spain; New Zealand Parliament; Bass Museum; Fort Lauderdale, Frost Museum Florida; | New Zealand National Museum.; Govett-Brewter Art Gallery, NZ; the Modern Art Museum of Dominican Republic; The World Bank. In 2002, a book on her work and practice, “Charo Oquet – Lo Que Ve La Sirena,” was published.

45

Ecue-Yamba-O was made possible with the support of the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor and Board of County Commission ers and The Miami Beach Cultural Affairs Council. It is also supported in part by by the State of Florida, Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs, the Florida Arts Council, And the national endowment for the arts (NEA) and Oolite Arts, The Perez Family Foundation, The Knight Foundation, and The Miami Foundation.

Printed in Miami 2022 Designed:

All rights Reserved

All images Charo Oquet copyright @Charo Oquet 2022

Ede Zones Press edgezones@gmail.com

305 303 8852

46

47

Charo

P.O. Box 398356. Miami Beach, FL 33239, USA www.edgezones.org (305) 303-8852 edgezones@gmail.com

Oquet and Edge Zones Press Miami

Oquet and Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Edge Zones Press Miami

Oquet and Edge Zones Press Miami

Oquet and Edge Zones Press Miami