Proposal Essays

Artists Bios Thank Yous

2

PROPOSAL

Dressed to Be Seen presents clothing created by local and international BIPOC artists who inspire, challenge, and engage with Fashion and its subversive characteristics, reflecting a BIPOC point of view.

Miami, FL December 2022

Dressed to Be Seen will feature clothing created by BIPOC artists who inspire, challenge, and engage with Fashion and its subversive characteristics, reflecting a BIPOC point of view. The project aims in exploring how the works engage with each other, suggesting alternatives that use Fashion to traverse our present, disseminate future forms of knowledge, center collective healing, and forge new vocabular ies to stake our claim to our place in society.

The streets have long been a space to subvert colonial power and reposition agency within BIPOC and queer bodies. Dressed to be seen celebrates how BIPOC and LTBG+ bodies show resilience, offering strength in the face of adversity and joyful affirmation and self-love, documenting intimacy and indomitability.

Dissident Fashion will celebrate a diverse range of approaches by the BIPOC gaze from multiple viewpoints in a publication that brings together BIPOC practices from the social sciences, the arts, and the fashion industry. Dressed to be seen will be the first of many more Dissident Fashion projects, an initiative that aims to question traditional notions of Eurocentric Fashion. Dissident Fashion will examine Fashion from the Afro-Indigenous point of view, using radical imagination as a tool for colonial subjects to gain agency through recontextualized dress and adornment. We believe that by putting disobedience as a praxis of liberation at the center of the discussion, clothing is not a weapon of domination and control but a tool of empowerment and subversion. We have chosen local artists and artists from the Americas to document their clothing and tell us why they create. The publication will be accompanied essays written by BIPOC artists. Dissident Fashion will be divided into a publication and an artist’s colloquium. The documentation of the Dressed to Be Seen will be presented in a full color publication that will be distributed for free to the public at arts institutions, galleries and art fairs as well as online through Issuu a digital publishing platform so that it is available internationally.

3

4

ESSAYS

DRESS THE BODY.

By Johan Mijail

To dress implies an exploration of languages and communicative actions, when we consider the poten tial of clothing to make visible corporealities outside the structure of hegemony. That is why, apart from its typical meaning, we can understand clothing as a device that functions at once as a tool for distinc tion and as a signal of identity. Historically, it has served as a library of trends capable of locating the expressions of certain groups and populations that resist the canon, and its reproduction in the main stream, the media and mass culture.

To analyze, then, what it means to dress the body illuminates a fascinating network on which to situate the dynamics of rebellion. Which is to say: to reference what is dressed and situating it within its contextual possibilities, offers reflections capable of framing a politics of the epidermis. Such a politics stems from a system of symbols, and which speaks to a non-verbal language that is active within societ ies. As Umberto Eco (1976) notes, such a language might, through its semiology, deepen the communi cative character of dressing.

To discuss dressing as both an adornment and a means of communication reveals new perspectives. The body manifests not only a genesis that locates the subject within a reality (racial, gender, beliefs, or geography) but its own discursive power. Clothing, beyond its usual purpose, exists as a resource that al lows us to address complex ideas: to investigate in greater depth, for example, people’s daily lives, what they are communicating and/or expressing at the moment of dressing. Clothing, then, reveals networks through which to explore the distribution of discourse and, from its qualitative potential, the sociologi cal and cultural frameworks that underpin it.

I remember, for example, that as a black person in an immigrant situation, in the southernmost part of America, people used to tell me that when I dressed in “so many colors” I called “too much attention.” In this particular case, the colors of my clothing manifested through Afro-descendant cultural cues of the Caribbean culture in which I had formed my style of dress, but which detonated in other people alternative meanings.

Though this instance appears isolated, it located my black body in the definitions of that society’s nat uralized racism in its day-to-day spaces. On a larger scale, it almost always defined foreigners through these kinds of micro-xenophobic arguments, which didn’t permit an understanding of the complexity that clothing can express about the existence and difference of the non-national other. This is articulat ed in “Racism in Chile: the skin as a mark of immigration” published by Editorial Universitaria (2016), through ideas like the performativity of Afro-Caribbean bodies (Colombians, Dominicans and Haitians), and how their manner of dressing precipitated a cultural shift in the cold, gray city of Santiago, follow ing a significant wave of black migrations since 2010.

If we want to find power in these approaches, we must understand clothing as a distinct field of inquiry that explores beyond its function as a design. The study of Clothing is typically approached as that of an “object”, situated in a historical moment, rather than of the relationship between the dress and who wears it; let alone as a resource – or even an act – that conveys messages. To dress oneself should imply a bodily practice and how this practice is immersed in a social interaction. This is confirmed by the many groups of people who build communities that differ from others, to a large extent, by how they dress.

In this sense, authors like John Carl Flügel in “The Psychology of Clothes” (1930) tell us that clothing serves to cover the body and thus to gratify the impulse of modesty. But at the same time, it can serve to enhance the beauty of the subject; this was most likely its most primitive function. In other words,

5

from their origins, clothes anticipate moral judgements. Society has used clothes, on the one hand, as a way to hide “our shame” or to display that which makes us attractive. And it is precisely this aspect - dressing as a result of a practice inherent in social life around the world - which contrasts with an idea of fashion as a social construct invented after clothing, to its - we might sayprimitive necessity.

On the other hand, Isabel Cruz de Amenábar points out that, since primitive times, clothing has had more purposes than just covering the body: Decoration, modesty and protection, in this order would be the deep motivations that have led humanity to dedicate so much effort, resource and interest to clothing.

The phrase “the habit does not make the monk”, encourages us to consider the human beyond their clothed appearance. Yet, certain contemporary scholars have inverted the idea by underlining the importance of the external image of man, revealing the subject as both an individual being and as a social entity.

What we see, from these points of view, is a historical evolution of clothing, as ever-changing, and which defines eras and groups by its differentiating power and unique characteristics. The act of dressing activates symbols, from both the unconscious and the conscious, in its capacity to reveal imaginative worlds for the purpose of its creation, but which also invites us to consider dressing as an emancipatory tool of socially repressed groups. More recently, clothes have communicated an eth ics, through their environmental sustainability, or, in addition, a criticism of global capitalism and the exploitation of adults and children around the world for its industrial production.

Villa Mella, 2022.

THE POWER OF THE GARMENTS

By Charo Oquet

What is considered beautiful has always been in the eye of the beholder. Allegedly, beauty is, widely recognized. Historically, beauty is defined as the opposite of what is unattractive. Usually, anything different elicits hostile reactions, violent repulsions, fear, and even terror.

This idea led me to search for dissident fashion that seeks to identify and analyze the relationship between fashion and otherness - everyday expressions that re-signify the ugly and at the same time, illuminate the logic and constructions of contemporary society’s point of view on fashion.

In 2019, Just as the pandemic began, I began my Ecue-Yamba-O fashion project. The work concerns the body, and clothing; the worldwide pandemic crisis brought these topics into new focus. The project sought to examine the relationship between fashion and power, and to question its scope and pervasiveness in our society in current local and global culture.

As coronavirus spread throughout the world, the body became a dangerous weapon, a mortal threat. Bodies were restricted, secluded and excluded. We could no longer physically socialize; we had to keep our distance and remain in our homes.

Three years later, with or after the recent Supreme Court ruling that overturned the 1974 Roe v. Wade law - which had guaranteed women’s access to abortion in the United States - has once again placed the body at the center of our lives. There is a new fight for its control.

6

In these times, clothing, dress, and adornment are recontextualized, and play a key role as a form of expression of our bodies. They become tools of empowerment and subversion, communicating identity, and commanding respect.

After many years of making garments and necklaces my practice has taught me that my interest in fashion is not about the production and retail aspects, but rather of wearing them and celebrating the works of others. I want to create visibility for others who also create garments and adornments to mark spaces. I want to show clothing as a tool of resistance, fashion can help you navigate and subvert a system created to keep you in your place and invisible. Through this project, I want to show how clothing allows you to code-switch in all spaces. I want to illuminate the power of clothing and the people that make it, to move beyond the decorative, and find in clothing a political device.

Fashion is an omnipresent medium, vital to the dynamics not only of art but of contemporary life. Since the beginning of conceptualism, the photographic image marked a new way into use discourse and language, tracing new ways of understanding the world and seeing the invisible.

Invisible is the non-immediate, the indirect, that which takes a little longer to reveal. That which underlies the images: ideology, memory, drive, dilemma, aporia.

Photography is the artistic practice that best reflects our time. It is an exercise in conscience that borrows from so many fields of knowledge and inquiry: ethnography, anthropology, sociology and psychoanalysis. The photographic image documents and testifies to who we are. But it is necessary to test the image, and reflect, with a critical eye that questions not only the obvious, but what is not usually seen.

With “DTBS” I wanted to deploy the strategies and procedures of fashion, as they develop in the context of artistic creation. To sharpen our understanding, and to find the blurred angles of the non-visible, seeking a diverse aesthetic to inform new ways of organizing and interpreting the world, with a critical eye that questions the lived reality.

The project aimed to link the central concepts and the language of fashion as a way to build meaning, and to interrogate what is real and what is imaginary through registration, intervention, appropriation, construction and re-signification. The project articulates contemporary stories, reaf firming the principle of creation from subjectivity, from photographic records, and appropriation.

The idea of creating a publication meant that I could collaborate with artists outside of Miami, who were also creating garments whether to wear them or use them in their performances. With Dressed to Be Seen I succeeded in collaborating with a group of artists who challenge, and engage with fashion and its subversive characteristics, and reflect it through a BIPOC lens. It fueled my interest in exploring how each artist’s work engages with the others - suggesting alternative uses of fashion that traverse our present, disseminate future forms of knowledge, center collective healing, and forge new vocabularies that stake our claim to our place in society.

This is an ongoing dialogue that I hope to continue through other platforms.

7

ARTISTS

DONA ALTEMUS Miami, FL

For the project titled “Holding it Together”, I created wearable sculptures to activate handmade objects and conversations relating to gender roles and the human form. Since the human form is already charged in many ways it is used as a platform to expand sculpture aiming to challenge gender associations juxtaposed against body language in relation to the symbolism of objects of move ment . I aim to create modular pieces that can be altered and reformatted according to a particular moment in an attempt to reflect the process of one reconsidering and reorganizing any potential distortions. I began exploring wearable sculptures about a year ago. I create wearable sculpture and am interested in shifting objects from being discrete and stagnant (on display) to becoming activated and engaging with people as an interactive part of their walking experience. I use fabric as a draw ing material and also duct tape at times. I like to use more experimental material surfaces other than paper for drawing projects. I sew but more to create textile pieces not necessarily to make clothes.

9

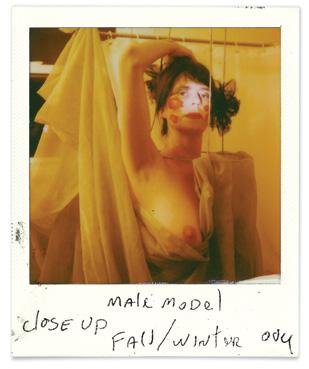

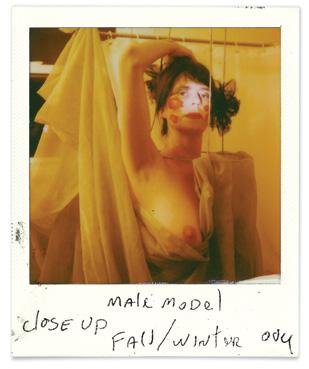

EDDY

ALVAREZ

Miami/New Orleans

- MALE MODEL

Inspired by the need of humans to be wasteful, Male Model started making and implementing un wearable clothing from metal and discarded fabrics and materials into his performance art. With his latest clothing concept, Male model looks forward to achieving a new visual syntax blending casual with formality and playfulness with trash.

10

ARANTXA ARAUJO Mexico/New York

My practice is about enlightenment. Through thorough research, both scientific and philosophical, I construct transdisciplinary projects that expand our awareness about aspects of the physical, the affec tive, the cognitive and the spiritual. In these projects, the clothes and objects I design and utilize, aim to become entry points to access embodied meditations to practice being present, learning how to no tice, and become aware of our past and present by accessing heightened states of consciousness. The clothing and objects I use in performance are made of reflective and light emitting materials. These become extensions of my body and are tools of self-reflection and illumination. They invite the eye to observe, ponder and meditate. They bring us to our present and establish new modes of consciousness that enable balance, blissful presence.

Photographer: Kolin Mendez

Photographer: Kolin Mendez

11

ADAH BENNION Utah

Referencing both the Depression and wartime era practice making clothes, quilts, and household ne cessities from emptied cloth flour and feed sacks, and the decadent attire and sheer opulence worn by celebrities at the Met Gala, High Fashion, Great Value! is an haute couture collection made entirely from repurposed low density polyethylene (plastic) shopping bags and single use product packaging that explores the lifespan and reusability of the material waste generated on a daily basis by a con sumer society obsessed with the luxurious immediacy and convenience of cheap, disposable products and fast fashion, and how, if left unchecked, this will alter and shape the resources of the future.

Swathed in used, hand sewn and intricately detailed plastic packaging, we stand boldly; physical acts of rebellion; in defiant solidarity of a society that idolizes the reckless pursuit of profit by individual capitalists, ignoring the fire raging in its own house. Reclaiming our power and our voices, we neuter their advertising campaigns and subvert the algorithms as we consciously and collectively reframe and redefine the very idea of value. No longer willing to promote their fabricated beauty standards or support their wallets with our bodies, we intentionally choose byproducts over their products, elevating the material waste of their market to a state of great value, identifying for ourselves the true objects of desire.

12

BLUU BLUUSA (MERCEDES ESCOLAR ARÉVALO) Dominican Republic/Spain

Dress to be you. It is to leave the uniforms, the alienating bondage that oppresses us, and the masks that disguise us. To have the elegance of dressing oneself.

To cover your body is to discover it. Imagine the clothing that grooms you, to create life, to shelter it from you.

To be part of an endless fabric, like your lineage and untangle the skein from your tree; to adorn it from you.

In the background a ceramic patchwork, like a loom, that Bluusa Bluu has created to wrap her terrace. She dresses, to be her: with a pinch bag of Dominican craftsmanship, a second-hand dress, a recycled necklace and sandals of Spanish design.

13

PIP BRANT

Miami, FL

Initially my mother got me started working with sewing my own clothes as a kid. By the time I was in Jr. high, I made most of my own clothes. There were a few reasons to make one’s own clothes when living in an isolated community—no stores and the curiosity to see what my mother and I could make. Today, I do my own sewing. I have several machines (way too many) to serve different functions. In a way both textile or fiber simultaneously were my first medium. However, my formal art training covered painting long before entering the surface design medium. The connection to painting is totally blurred to me. They function the same. Color, Line, Shape and Texture. I use the same head for both painting and textiles.

My goals now are different from when I was young. Now I want to make my own surface designs on cloth and have them be the main point of the garment. These designs have a message-or code. They are not simply decorative. Now my clothing is simple in construction to allow the surface design to come through. Now the body becomes a type of exhibition space.

14

MARIA EUGENIA CHELLET

Mexico

I use clothes in my artistic proposals because I work with prototypes, archetypes and female stereotypes that are culturally recognized through both their attributes and their wardrobe, especially stereotypes that use uniforms such as the nurse, the maid, the nun, etc.

15

GIANNA D Miami, FL

“It’s my Party and I’ll Cry if I Want To“ Sometimes we can feel pressured to put on a mask that says everything is perfect, even when it’s not. My 4-tiered cake mask, overlayed with sparkly, colorful, eye- catching sequins, screams celebration. The sequins, reflect off one another, directing your atten tion here or there, creating a beautiful distraction – concealing the fact that we may actually want to cry. It’s okay to not be okay.

16

VICTOR DIEGUEZ

Miami, FL

Growing up I had a hard time communicating and expressing myself. Artistic expression is the core of who i am. My style cannot be narrowed down to one aesthetic. I take inspiration from previous decades, from 1920’s through the early 2000’s. While referring to the past for artist inspiration, I also love challenging gender stereotypes to create a unique type of fashion, ultimately showcasing my talents as an artist.

My artistic designs encompass makeup, traditional/digital art and fashion designs. My style is eclectic and breaks down mainstream fashion barriers. It represents me, forever changing

17

HUMANJUICES

Brooklyn, NY

Deconstructed and frankensteined – 100% Organic, fair trade, ethically sourced, and sustainable – a detritus utopia covers the body in elaborate fibrous layers of crumpled cotton, frayed polyester, and weathered wool transformed into a glimmering fitted mould for the ecologically conscious fashion victim.

21

JAN & DAVE Miami, FL

HEADPIECE/COSTUME DRIVEN PERFORMANCE ART, by Janese Weingarten

When I write the concept/scripts for the “Jan & Dave” performances I am driven by my joy of mak ing costumes and headpieces. So, I make the headpieces first and then the costumes, script, dialog, actions, cue cards, and songs. A garage band sound track is made and oversized cue cards that the audience is meant to see and read. There is a battle that creates the tension and plot of the perfor mance. For example, for the performance entitled “Randy California Vs. Led Zeppelin” is based on a true legal battle between a well known rock band and a lesser known band who accused them of plagiarism.

Therefore, I based the concept/headpieces/costumes on a song that parodied the alleged plagiarized song “Stairway to Heaven” called “Hairway to Steven”. I took the title literally and created a head piece with an actual ladder on my head extending to the heavens. The meaning of the headpiece was to combine the ideas of hair, ladders, and heaven. The costumes and the head pieces are meaningful to the performance both visually and conceptually. They don’t enhance the meaning…they convey the literal meaning of the performance.

23

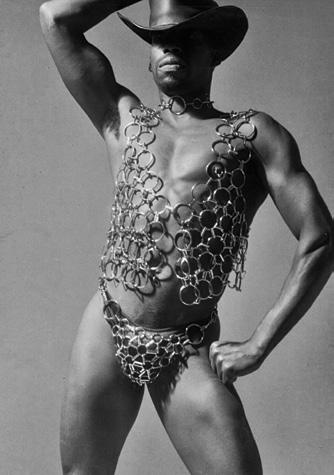

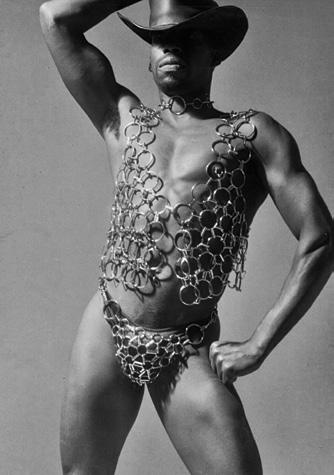

CAROL JAZZAR Miami, FL

My interest in fashion started in my childhood in Brittany, where I grew up. I spent afternoons in our backyard making elaborate dresses and headpieces with garden leaves and flowers. At the time, this was simply called “play,” but that first creative impulse redefined and manifested itself when I started Chains Addiction, this alternative-wear clothing line.

In a way, the premise was the same. Instead of flowers, leaves, or branches, I used different pieces of metal, large and small, which I combined to create what might look like an outfit. It was a creative exploration with no real commercial intent.

24

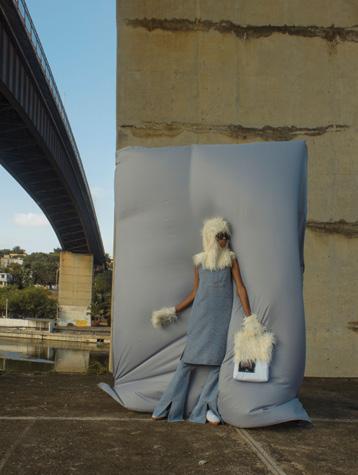

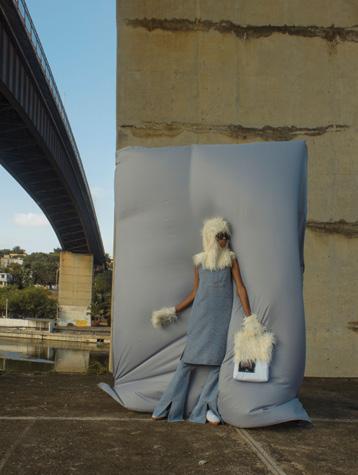

LEBLANCSTUDIOS

Santo Domingo

is a Caribbean brand from Santo Domingo founded in 2014 by Angelo Beato & Yamil Arbaje. With an awareness of globalization, highlighting personal identity and the blend of races, Leblancstudios strives to become a social, cultural and political movement that empowers a generation of young peo ple across all continents to express themselves.

The brand aims to redefine a new Caribbean masculinity and femininity to the fashion landscape.

25

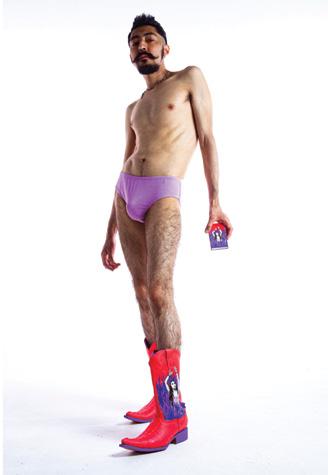

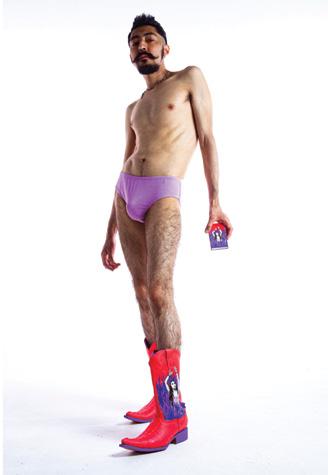

LECHEDEVIRGEN

Mexico

The cowboy boots overlayed with the image of the “Anima Sola” (Lonely Soul) were part of the main iconography of “Inferno Varieté,” a performance project addressing hegemonic masculinity as the cornerstone of Cis-Heteropatriarchy violence. The work is meant to reflect on the construction of the social image of ‘men’ from well-defined figures and images of strength, virility, and power. The cowboy boots represent the symbolism associated with the traits of hegemonic masculinity of north ern Mexico. Simultaneously, overlayed with the image most associated with the Catholic religion, the Animas, a woman burned in purgatory. Using and juxtaposing the images and objects portray the complicated social relationship of gender violence and hate crimes in Mexico, and the dominance of the socially accepted masculine over feminine.

26

LEECHY

Miami/New Orleans

These fabric garments play a major role in our performances. They allow for us to create different shapes and play with size and contrast.

27

LULU LOLO

NYC

The methodology to create each of the personas in my performance art and theater work, begins with the costume. Through research and character study, I determine the mode of the stylistic details according to their identity. Once defined, I’m able to assume the interiority of the individual. I perform in the guise of different identities to illustrate timely topical issues. Wearing historical costumes for street performances as Mother Cabrini, Joan of Arc, The Gentleman of 14th Street, I create a dialogue and relationships with passersby. The palette for my own style of dress and home decor is dedicated by color and pattern: black, red, and polka dots with attention to details, hats and gloves.

28

BRENO LUAN Brazil

“MANTO SAGRADO” is a testament to eternal memories left by our loved after their departure. “MANTO SAGRADO” Sacred Cloak looks into the chaos and reveals the creations still playing a part in the reality of young Brazilians today. “Sacred Cloak” is part of a crocheted artwork begun by Caique Alexandre, and although they have passed it enabled us to create something that transcends life.

Accompanied by the sensitivity of Vinicius Marques’ photography, this work is meant to offer care and support to young blacks still alive. Breno Luan’s creations remind him of what life meant (to him individually) and can be translated for the world to relate.

29

JOHAN MIJAIL CASTILLO Dominican Republic

Manifest.

This body is not completely mine. This place that I inhabit, born of genital contradiction, of a blackness that constitutes me as a place of resistance, of the trans-feminist radicality. It is in turn the body of others.

It is impossible for me to try to write – here - a reflection of the corporeal, of its sex, without a reflection of the collective body. There is no individualized body, there is always a social body that crosses it, affects it and fills it with context, with political potentiality.

I cannot become decolonized without first experiencing the loss of a homogeneous masculinity that I was taught, supposedly impenetrable, supposedly destined to win in its rigid and ignorant pettiness. I cannot de colonize myself in this migratory process without linking myself to other processes where identity is also put in crisis. A crisis that allows us to continue building a fiction that is not racist, a trans-feminist invention that gives us the opportunity to experiment by promoting failure, “abortive unproductivity”, our right to imagine.

This body is not completely mine; it is a noise, the epidermis of other animals and plants, of cells, of other atoms. A membrane that learns that identity is not a common space, but a form of radical relationship with life. This body, this anus, is social. This body, this year, is you.

30

CHARO OQUET Miami, FL

I have used clothing as an instrument with which to connect the past with my present and the fu ture, an energy essential to my work. I have always felt wearing certain clothing helped me create my performances and believe my garments are transmitters of the creative energy that flows through my body. My garments are not only tied to Afro-religious imagery - they also connect to my indigenous roots, drawing on figures like the Heyoke, the sacred clown – who is also connected to Elegua, the Orisha deity of the crossroads.

Among my works I also give great importance to the aesthetic and spiritual dynamics of the festive Dominican/Haitian Gaga/Rara carnival tradition, which shares a common heritage with Afro-Cuban and African-American carnival traditions. I want to show that clothing can be a tool of resistance, it can help you navigate and subvert a difficult system created to keep you in place and invisible, allow ing you to code switch in such spaces.

31

AMITA PAIZ Miami, FL

I’m a dynamic ever changing human shaped creature. I’ve spent my whole life playing, exploring, creating. I haven’t married to any medium, I want to try all, all at once, then leave it behind, then try again. I like to surprise myself as I create, most of the time I improvise I let things happen.

I have been experimenting with textiles for two decades now. Transforming existing pieces and giving birth to new ones, wear them, dance with my creations see how they move on me, with me. I would say I become a new character every day.

I documented my everyday outfits for 6 years. It was a creative exercise: a way to play with the garments I already had and wear them in a new way, layer them, transform them, repurpose them. It was also a social experiment; people would react different towards me depending on what I was wearing. Fashion to me is a way of expression, I still enjoy creating fun outfits, but I recently became interested in adding a bit more fantasy and playfulness building this wearable/sculptural characters in which I could also perform.

32

GERALDINE RIVERA

As someone who was born and raised in the Dominican Republic, to be seen wearing a dollar sign dress it all about creating visual contradictions to make people stop and laugh, so they think about the larger message.

I remember a Sylvia Plath poem: “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; I lift my lids and all is born again. (I think I made you up inside my head.) ...” To me it’s creating a persona is about having the liberty to recreate and reconstruct the self every day. I wake up a blank canvas, and treat myself as a continuation of my artwork. That persona gets to experience that day, but comes undone at the end of the day. I get to live and die all in 24 hours, and start all over the next day.

33

“Future Clothing of the Ancestral Future”, in which the theme is related to an imaginary survival in the dark present. Clothing created to change the social/political structures of the West and also to relive as a shamanic other.

34

WAGNER ROSSI CAMPOS Brazil

KALAN SHERRARD New York, NY

I think it has to do with me being really bored with the world — really bored and really interested. I think it has to do with politics and being against and critical of how the world is organized. The only thing left to do is act insane. Fundamentally I’m against providing context and sort of not inter ested in describing what I do — a non-narrative nihilist anarchist puppet show about literary theory. I make things out of garbage and dead animals. I like to collect things that seem to semiotically carry weight and use them to collage, sort of to suggest the work is very meaningful but also to say nothing is very meaningful at all.” (Meet Kalan Sherrard, NYC’s Most Avant-Garde

Performer By Joe Coscarelli, New York)

Nihilist Subway

35

MICKI SPILLER

Brooklyn, NY

My work and artistic practice are inspired by books and book structures. Books create a physical space where things may be stored; stories, pictures, information, data, facts, etc… My recent projects have stemmed from reading, which culminated in a series of Book Jackets (pun intended!) I envision these garments being worn in a bibliophile fashion show, not by prancing models, but where ordinary people walk down runways with their noses in books.

My studio practice can be evenly divided into reading, writing, and making. Each individual book jacket begins by reading a book, writing in a journal then designing, sewing, and embroidering a jacket depicting the work of literature. The structural forms of the jacket and the words embroidered take on themes and images of how I was inspired as I was immersed in the book.

36

KOCO TORIBIO Dominican Republic

I came to the world of fashion because of a concern I had since I was a child, I have never seen my self as a fashion designer, but somehow that restlessness manifested itself in my work and always at tracted clients from the fashion world. Sokio my brand, was born from my desire to mix my art with clothing... the first collection was presented in 2009 using silkscreen on American apparel. In that process I chose not to use prefabricated clothes and put art on it, I wanted to design the clothes and the art... With everything as part of the work I learned to design my clothes and my own patterns. On a conceptual level, Sokio is the combination of everything I enjoy, creating graphic design, fash ion, and painting, adapted to streetwear. I am interested in seeing my work anywhere I walk without expecting it so it can provoke reactions and conversations

37

ANABEL VANONI Argentina/México

Triptych “LAS MAGAS” (the Magicians) Fotoperformance Year: 2019/20 In Art, which fuels my passion and provides oxygen, the only medium where I found total creative freedom is the Perfor mance genre. Using my physical, emotional, and spiritual creativity I can evolve and share with the others again and again... For many years I have used photo-performance, live pieces, video per formance or installation in each of my works. By composing a thoughtful and detailed wardrobe I create color and symbolic elements to contribute to the concept and the visual dialogue. The chromat ic pieces invite the viewer to immerse themselves and go deep into my work. By creating work at the intersection of art, design, fashion, the ancestral and avant-garde elements merge providing me with indispensable tools to generate more work.

38

LISU VEGA

Miami, FL

My early work on experimental engraving opened up the possibility of working on multiple materi als, such as paper, fabric, and metal, which also became an incentive to move off the canvas and to tri-dimensional work.

My interest in better understanding my own identity led me to the exploration of the relationship between fiber and the human body, and to go beyond the body to the space that surrounds us.

I employ a myriad of mediums, materials, and techniques to work on the themes that interest me, using weaving and my knowledge of its ancient techniques passed down through my Wayuu heritage. This work has become my preferred expression and exploration of my own memories, identity, and migration story. The intensive physical nature of the weaving work conjures my feelings of loss for what has been left behind, simultaneously creating a bridge to my past and a strong message of hope for the future.

39

PANGEA KALI VIRGA Miami, FL

The ‘Inner Compulsion’ collection, inspired by the Bauhaus movement draws inspiration from the linear graphic aesthetic traditionally aligned with the Bauhaus school combined with a flair for the chaotic and layered. Special attention was paid to the overlooked female figures in the movement and their gridded patchworked maximalist fiber works, often made of unusual upcycled materials. The Inner Compulsion collection is made entirely of upcycled materials such as shower curtains, decon structed sculpture, donated second-hand garments, creatively reworked to become a new textile and garment. Each scrap and thread cut during the process is reintegrated into new designs until every element is used completely, resulting in a radical zero waste process.

40

BIOS

DONA ALTEMUS

Interdisciplinary practice explores the tension between human perception and fragments of material culture from fields as diverse as biology, architecture, and mathematics. Most recently, they have worked on wearable sculpture as a method of articulating the space between being and experiencing a work.

EDDY ALVAREZ - MALE MODEL

is a Miami/New Orleans-based visual and sonic artist whose performances have examined cultures of consumption, overstimulation, and in his first solo exhibition at Edge Zones gallery in Miami, examined inner city structure and urban environment as paralyzed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

ARANTXA ARAUJO

is a New York-based Mexican artist with a background in academic neurosci ence and bio-behavioral research and technology, whose work has been shown in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

ADAH BENNION

is an artist, sculptor, photographer, and educator from Utah, who works primarily in found materials using techniques from textiles and needlework to investigate ideas of inheritance, materiality, possession, mortality, and memory.

BLUUSA BLUU MERCEDES ESCOLAR ARÉVALO

works at the intersection between science and art, through her training as an ethnographer and visual anthropologist, and has worked on the topics of culture, gender and environment. Born in Madrid she became a naturalized Dominican in 2006.

PIP BRANT

Brant has degrees from the University of Montana (BFA) and the University of Wyoming. (MFA). Brant grew up on the western Plains Indian reservations (Sioux, Cheyenne, Assiniboine) where the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Public Health employed her family. She has lived and worked in Montana, Wyoming, London, England, and Missouri and in 1999 moved to Florida. She is an associate professor in painting and drawing at Florida International University.

Pip Brant has exhibited in Belfast, Ireland, Lithuania and London, England. In 2003 she won the South Florida Cultural Consortium for Visual and Media arts for her works in fiber, Tabled Reports. Other awards include the Wyoming Arts Fellowship and funding from the New Forms Regional Initiative for Cattle/Text Interaction. Recent venues for solo exhibitions include the Univer sity of Wyoming Art Museum,( Tabled Reports) and the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, (interactive installation, Flying Carpet, and fibers, 2007). Another solo exhibit with paintings was exhibited at the Deluxe Arts Gallery in April of 2007. Brant’s work embraces the use of the absurd and humor and cites the plays and philosophy of Bertold Brecht as a major influence.

MARIA EUGENIA CHELLET

is a multidisciplinary visual artist from Mexico, exploring female archetypes, prototypes and stereotypes through video, performance, and object, often through the lens of self-portraiture to articulate the multiplicity of identity. A pioneering professor at the Faculty of Political and Social Studies at UNAM, she has exhibited many times both in Mexico and around the world

GIANNA D is a mixed-media artist from Miami, FL, who was a Florida International University Ratcliffe Art + Design Incubator Fellow where she also earned her BFA and MFA. She has exhibited nationally and internationally.

VICTOR DIEGUEZ

works with makeup and fashion, having evolved their practice beyond tra ditional art into something new when dressed around the body. Often using surreal techniques, Dieguez ties makeup into their practice to experiment with new dimensions and forms.

NICOLÁS DUMIT ESTÉVEZ

RAFUL ESPEJO OVALLES is a Dominican-born, New York-based artist and performer who has exhibited at galleries and institutions around the US and Europe. Nicolás is the founding director of The Interior Beauty Salon, an organism living at the intersection of creativity and healing.

KRZYSZTOF ANDRZEJ DZIEMASZKIEWICZ (LEON) is a Polish visual artist, dancer and choreographer who has led his theater company, Read My Lips (Patrz Mi Na Usta), since 1995. He is a frequent collaborator with the legendary art space and nightclub Sfinks in Sopot, Poland.

DIANA EUSEBIO is a multidisciplinary artist based in Miami, FL, working across photography, fashion, and textile design. In 2016 she was named US Presidential Scholar in the Arts–the highest national honor for a young artist by the Obama administration.

HOUSE PENCIL GREEN is the multimedia, multi-platform collaboration between interdisciplinary artist/designers Amy Ruddick and Joseph Herring, formed in Los Angeles CA.

HUMANJUICES

works across fashion, costume, and film - a connoisseur of trash, on a mission to upcycle the world.

JAN & DAVE combines visual and audio performances, linking clothing and sculpture through to the sonic profile of the music. Using found objects and the concept of thrift, they become characters immersed in the narrative through headpieces and costumes.

CAROL JAZZAR

is an interdisciplinary artist and former clothing designer who lives and works in El Portal, Florida. Her work examines nature through studio practices of collage, drawing and writing; and outdoors through photography and site-spe cific installations.

42

LEBLANCSTUDIOS

is a brand founded in 2014 by Angelo Beato & Yamil Arbaje in Santo Domin go, Dominican Republic, which aims to redefine a new Caribbean masculin ity and femininity in the fashion landscape. The brand was a finalist at the Iberoamerican design biennial in Madrid 2018.

LECHEDEVIRGEN is a non-binary artist specializing in hybrid and expanded art forms, combining performance, critical writing, image creation, photography and video. Currently, they teach on the gender studies program at the Universi dad Autonoma de Querétaro UAQ. Their work reflects on sexual dissidence, non-human entities, the occult, body, disease, death and gender studies.

WAGNER ROSSI CAMPOS is a visual artist from Brazil who works on contemporary identity through the perspective of ancestry, gender, and decolonization. Through performance, video, paining and installation, they use clothing to contextualize the ephem eral body in constant change. He teaches Fine Arts at the School of Fine Arts at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

KALAN SHERRARD

is a street performance artist, puppeteer, anarchist and posthumanist. De scribed in New York Magazine as New York City’s “Most Avant-Garde Nihilist Subway Performer”, Sherrard has faced arrest at protests against Art Basel in 2014, and in 2016 made headlines satirizing then-candidate Donald Trump.

LEECHY is a performance art duo experimenting with sound, movement and visual art.

LULU LOLO is a performance artist, playwright, actor, and activist who has worked extensively on themes of age, immigration, ritual, symbolism, and myth over a twenty-five year career. Her performance, Where Are the Women? (2015) interrogated New York City’s lack of public monuments to women and was featured in the New York Times.

BRENO LUAN is a writer, poet, and performer in São Paulo, Brazil, whose work seeks to transcend while expressing the hatred that surrounds him. Vinícius Marques is a photographer and video creator in São Paulo, Brazil.

JOHAN MIJAIL CASTILLO is a writer and performer from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The author numerous books of illustrated poetry and essays, their most recent book is a novel, “CHAPEO”. They have performed across the Americas and Europe.

MICKI WATANABE SPILLER is an New York-based artist, sculptor, and writer and whose books feature in the collections at MoMA, Franklin Furnace, The Newark Public Library, among other venues. Micki teaches 3D design at Parsons New School University and the Pratt Institute.

KOCO TORIBIO is a visual artist and graphic designer and illustrator from the Dominican Republic, whose designs take shape in the streetwear brand Sokio_o.

ANABEL VANONI is a director and performer in the fields of dance, theater, and experimental film. Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, she now resides in Mexico City, and has lectured and exhibited work across the Americas and Europe.

LISU VEGA is a Venezuelan-American multidisciplinary artist working with engraving, sculpture, installation, and fashion art. Her work explores ideas of sustainabil ity, migration, memory, and identity, employing a zero-waste creative practice and the weaving techniques of her Wayuu heritage. Vega has exhibited across Latin America, the U.S. and Europe.

CHARO OQUET is a Dominican born, Miami based, interdisciplinary artist whose extensive oeuvre includes performance, sculpture, installation, painting, fashion, video and photography, and which she has exhibited, performed, curated and lectured around the world since 1981. Her work, which incorporates dynamic installations alongside the idioms of Afro-Caribbean culture and religion has received numerous awards and features in leading publications. She is the founder and artistic director of Edge Zones, a non-profit arts organization in Miami, FL, and is the author of works including SuperMix, Wet, Arrayanos Portraits and Arrayanos Interiors.

AMINTA PAIZ is a multidisciplinary artist, photographer, textile and costume designer from Guatemala, whose creative process incorporates improvisation, transformation, and dance.

GERALDINE RIVERA is a multidisciplinary artist, director and fictional character from the Dominican Republic. Working out of Santo Domingo after a career as a graphic designer in NYC, her award-winning audiovisual work has featured in national biennials and international festivals. She currently teaches at the Altos de Chavón art school.

PANGEA KALI VIRGA is a multimedia artist, fashion designer, stylist, educator, creative director, and producer whose work spans art and fashion. Her current project fuses high fashion and sustainability through the creation of wearable art out of upcycled materials that deploy clothing as a storytelling device, cultural marker, and political catalyst.

43

THANK YOU

I want to thank all of the people who made this project possible through their partic ipation in Dressed to Be Seen project. I specially want to thank Gabriela Keddell for her coordination, and Manny Prieres for his design of the book. DTBS seen was made possible with the support of the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor and Board of County Commissioners. It is also supported in part by by the the national endowment for the arts (NEA) and Oolite Arts, The Perez Family Foundation, The Knight Foundation, and The Miami Foundation.

Printed in Miami 2022

44

Photographer: Kolin Mendez

Photographer: Kolin Mendez