The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruction, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School), President

James Dalziel (NIST International School), Vice President

Jim Gerhard (Seoul International School), Secretary

Rami Madani (International School of Kuala Lumpur), Treasurer

Gregory Hedger (The International School Yangon), WASC Representative

Karrie Dietz (Australian International School Singapore)

Matthew Parr (Nagoya International School)

Marta Medved Krajnovic (Western Academy of Beijing)

Maya Nelson (Jakarta Intercultural School)

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou), Past President

Margaret Alvarez (WASC), Ex-Officio

Andrew Hoover (Office of Overseas Schools, REO, East Asia Pacific)

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director

Kristine De Castro, Assistant to the Executive Director

Maica Cruz, Events Coordinator

Ver Castro, Membership & I.T. Coordinator

Edzel Drilo, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator, Webmaster

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Assistant

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

Effective Teachers in International Schools: What about the

Marie H. Slaby

Robert Landau

Newly Founded East Asia Pacific International Schools Association (EAPISA) to Serve Schools and Students in the EARCOS Region! By Colin Brown

58 Global Citizenship Community Service Grant Empowering Change: Pathway To Freedom Women In Need (WIN), Sri Lanka By Bo Xin Zhao

Submit an article to the EARCOS Triannual Journal

What can be Contributed?

Here are some of the features:

Welcome New Member Schools, New School Heads, Principals and Associate members. (Fall Issue)

Faces of EARCOS – Promotions, retirements, honors, etc.

Campus Development – New building plans, under construction, just completed.

Curriculum Initiatives – New and exciting adoption efforts, and creative teacher ideas.

Green and Sustainable – Related to campus development and/or curriculum.

Service Learning Projects – Educational approach where a student learns theories in the classroom and at the same time volunteers with an agency (usually a non-profit or social service group).

Action Research Reports - Summaries of approved action research projects

Student Art – We will highlight ES art in Fall issue, MS art in Winter issue, and HS art in Spring issue.

Student Writing – Original short stories, poetry, scholarly writing.

Welcome to the Fall edition of the EARCOS Tri-annual Journal. I do hope your school year has begun smoothly and happily. All of us at EARCOS hope that this finds you and your school communities thriving, happy and well.

The EARCOS Tri-annual Journal promotes the exchange of ideas across the schools in our dynamic community. I hope that within the pages of this issue, you will find more than a few ideas and strategies to consider. The collection of articles in this issue addresses some of the most pressing topics facing international educators today. We welcome your contributions and are grateful to the many colleagues who have taken the time to share their thoughts with us. It underscores, again, what a very dynamic region this is.

We look forward to seeing many of you at the Leadership Conference (in Bangkok), the Teachers’ Conference (in Kuala Lumpur), and our upcoming webinars. Also on tap are dynamic new virtual institutes that many of you will surely want to consider. These new initiatives are designed to provide outstanding professional development in the comfort of one’s home throughout the school year. There is, truly, something for everybody available through EARCOS this year.

Please contact us any time you require assistance, have questions or recommendations on how EARCOS can continue to serve you and your community. With continued best wishes to you, your students and communities for a happy and healthful school year. May you embrace all that is so powerfully good about being part of an international school community.

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

Shangri-La Hotel, Bangkok, Thailand

OCTOBER,

APPLICATION DEADLINE: MAY 15, 2025

This award is presented to a student who embraces the qualities of a global citizen. This student is a proud representative of his/her nation while respectful of the diversity of other nations, has an open mind, is well informed, aware and empathetic, concerned and caring for others encouraging a sense of community and strongly committed to engagement and action to make the world a better place. Finally, this student is able to interact and communicate effectively with people from all walks of life while having a sense of collective responsibility for all who inhabit the globe.

APPLICATION DEADLINE: JULY 1, 2025

Students designated by their schools as a Global Citizen are eligible to apply for one of six $500 Community Service Grants. These grants are awarded to Global Citizens who are actively involved in a service project benefiting either children, adults, or the environment. The grant is intended to enhance and support the student’s continued efforts with the project during the final year of high school. Interested students are asked to work with their high school principal or designated faculty advisor to complete the application which is found below.

APPLICATION DEADLINE: JUNE 1, 2025

The EARCOS Board of Trustees has established the Richard T. Krajczar Humanitarian Award to recognize, each year, the work of one not-for-profit organization with a proven record of philanthropy in the East Asia/Pacific Region. For more information please visit the earcos.org website.

professionally designed curriculum ensures vertical coherence and elevates rigor without anxiety.

Multi-year models begin as early as Grade 8/Age 13.

Connects the personal, local & global (#TeachSDGs)

Prepares students for advanced exam-based courses

Customized for schools, modifiable by teachers & students

Robust English literacy, engineering, laboratory & data work

Coaching by experienced Intl School science teachers

Start the conversation for a 2025-26 launch! Click to schedule a 30min. webinar.

Learn more about the future of IT in education, including the evolution of AI and the potential of Power BI technology.

Crafted with the help of our iSAMS school Data Managers, the iSAMS team, and a range of industry experts, this guide discusses key topics impacting today’s school IT department.

Here’s a sneak peek at the contents:

• What is Power BI and why is it vital to driving school growth?

• The future of Artificial Intelligence in education and how schools can prepare for the changing landscape

• The best iSAMS features for Data Managers, the challenges they face, and how they’re supported in their role

• Busting the MIS migration myths and simplifying the implementation process

• How to protect your school data with dedicated systems and cloud-based security

• Details about the range of support options available for all iSAMS Data Managers 24/7

Want to read more? Scan to download your guide

Australian International School Phnom Penh

CIA FIRST International School

Daystar Academy

NIVA International School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan-Kemang Village

American School of Bangkok, Sukhumvit (XCL)

Australian International School Phnom Penh

Avenues Shenzhen

Brent International School Manila

Brent International School Subic

Canadian Academy

Canadian International School - Vietnam

Changchun American International School

Connie Kim

Betsy Hanselmann

Angela Xu

Jason Jarret Atkins

Jason Jarret Atkins

Lindsey Berns

Chandra McGowan

Ildiko Murray

Chinese International School Manila Angelica Fernandez de Castro

CIA FIRST International School

Daystar Academy

Dominican International School

Ekamai International School

Michael Gordon Wilde

Daniel Williams

Jacqueline Manuel, O.P.

Saowanee Kiatyanyong

European International School Ho Chi Minh City Ben Armstrong

Forest City International School

Garden International School

German European School Singapore

Global Jaya School

Hong Kong Academy

International Christian School - Pyeongtaek

International Community School - Singapore

International School Eastern Seaboard (ISE)

International School of Myanmar

International School of Qingdao

International School Suva

Tarek Razik

Peter J. Derby-Crook

Joram Hutchins

Howard Menand IV

Kasson Bratton

Don Lee

Darryl Harding

Emily Cave

Lyle Moltzan

Gabriel Lee

Thomas Van der Wielen

Shenzen Oasis International School

True North International School

Tsinghua International School

Keerapat International School

Benjamin Edmunds

Nansha College Preparatory Academy Hanson Yeung

NIVA American International School

North Jakarta Intercultural School

Oberoi International School

Raffles American School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan-Kemang Village

Shanghai SMIC Private School

Shenzhen Oasis International School

Singapore International School of Bangkok

James Cooke

Ezra Alexander

Patrick Hurworth

Alexander Pethan

Mark Thiessen

Dani Ma’u

Peter Garnhum

Kelvin Koh

Springboard International Bilingual School Yuan (Shirley) Su

St. Joseph’s Institution International

Stamford American International School

Taipei American School

The Winstedt School

THINK Global School

Tohoku International School

Tsinghua International School

United World College of South East Asia

Utahloy International School Guangzhou

UWC Thailand International School

Vientiane International School

Yayasan Sekolah International Australia

YK Pao School

Alice Smith School

American International School Hong Kong

American International School of Guangzhou

American School of Bangkok, Sukhumvit (XCL)

Asia Pacific International School

Bandung Independent School

Berkeley International School

Branksome Hall Asia

James Worland

Andrew Ris

Lori Marek

Mechum Purnell

Galen Rosenberg

John Gilberston

Lynda Nocera

Drew Alexander

Canadian International School - Vietnam

Canadian International School, Tokyo

Chadwick International School

Chiang Mai International School

Columbia International School

Concordia International School Shanghai

Daegu International School

Dwight School Seoul

Bradley Bird

Matt Mills

David Frankenberg

Nick Fawcett

Andy Wood

Hiroko Yoshida

Renee Ying Zhu

Cameron Hunter

Daniel Mullen

Jonathan Field

Andrew Ferguson

Craig Eldred

Iain Kilpatrick

Chandra McGowan

Kevin Passafiume

Megan Shaffer

Ade Oni

Barrie McCliggott

Laura Berntson

Dr. Aaron Willette

Esther Myong

European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City Ben Armstrong

Forest City International School Tarek Razik

Global Jaya School

Grace International School

Nelsy Saravia

Krista Wiesenauer

Hanoi International School Mr. Terry Linton

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Jess Cheng, Dean

International Christian School - Hong Kong Brian Schroeder

International Christian School - Pyeongtaek Don Lee

International Community School - Singapore Kara Stucky

International School of Phnom Penh Katie Ham

International School of Qingdao

Justin Crull & Collee Quernemoen

International School of Ulaanbaatar Regine De Blegiers

Keerapat International School Joel Gariepy-Saper

Keystone Academy Nick Daniel

NIVA American International School Frankie Tun

Osaka YMCA International School Kenya Washington

QSI International School of Shenzhen Jessica Hu

Raffles American School Sok Wee Kho

Ramkhamhaeng Advent Int’l School Sudha Rani Ebenezer

Saint Maur International School Samuel Jones

St. Johnsbury Academy Jeju Gregg Shoultz

Suzhou Singapore International School Scott Legan

The American School of Bangkok - Dan Mock

Green Valley Campus

Tohoku International School Robert Zehmke

Tokyo International School Robert Service

Tsinghua International School Weiky Liu

Unity Concord International School Jonathan Degler

Utahloy International School Guangzhou Martin Grist

Vientiane International School Sarah Clover

Wuhan Yangtze International School Paul deMena

Xi’an Liangjiatan International School Shameek Ghosh

Xiamen International School Cal Stuart

Yayasan Sekolah International Australia Beth Ashfield

Yew Chung Int’l School of Chongqing Pierce Wise

Yongsan International School of Seoul Jae Hwang

Alice Smith School James Worland

American International School of Guangzhou Lori Marek

Brent International School Subic Todd Wyks

Canadian International School - Vietnam James Howard

Canadian International School, Tokyo Kevin Passafiume

Chadwick International School Charlton Jackson

Concordia International School Hanoi Jonathan Mc.Daniel

Concordia International School Shanghai Jeshilma Villafane

Daegu International School Aaron Willette

Ekamai International School Marijo Escueta

European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City Ben Armstrong

Forest City International School Tarek Razik

Hangzhou International School Cynthia Wissman

Hanoi International School Terry Linton

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Jess Cheng

International Christian School - Pyeongtaek Don Lee

International School of Qingdao Justin Crull & Colleen Quernemoen

International School of Ulaanbaatar

Regine De Blegiers

Keerapat International School Joel Gariepy-Saper

Okinawa Christian School International Brad Skarin

Osaka YMCA International School Kenya Washington

QSI International School of Shenzhen Hafida Becker

Raffles American School David Hornby

Ramkhamhaeng Advent Int’l School Rhea Mae Pineda Recheta

Saigon South International School Dan Kerr

Saint Maur International School Samuel Jones

Sekolah Pelita Harapan-Kemang Village Jason Poarch

Shanghai SMIC Private School Amy Krauth

Suzhou Singapore International School Scott Legan

The Harbour School Thabo Metcalfe

Tsinghua International School Weiky Liu

United World College of South East Asia Rebecca Smith (Dover)

Utahloy International School Guangzhou Martin Grist

Vientiane International School Sarah Clover

Wuhan Yangtze International School Paul deMena

Xi’an Liangjiatan International School Shameek Ghosh

Xiamen International School Cal Stuart

Yongsan International School of Seoul Kimberly Kershner

American International School Hong Kong Aaron Baumgartner

American School of Bangkok, Sukhumvit (XCL) Rebecca Carter

Ayeyarwaddy International School Scott Dennison

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School Richie Morris

Berkeley International School Carla Chavez

Brent International School Subic Todd Wyks

Canadian International School - Vietnam James Howard

Canadian International School Bangalore Gail Mahoney

Canadian Int’l School of Hong Kong Wil Chan

Canadian International School, Tokyo Kevin Passafiume

Hangzhou International School Jeffery Hart

International School Dhaka Michael Palmer

International School of Dongguan Alexander Paulson

International School of Myanmar Jacob Huff

International School of Qingdao Justin Crull & Colleen Quernemoen

International School Suva Jake Verley

Keerapat International School Irene Gatanela

NIVA American International School Robert Randal

QSI International School of Shenzhen

Raffles American School

Ramkhamhaeng Advent International School

Sekolah Pelita Harapan-Kemang Village

Shanghai SMIC Private School

St. Johnsbury Academy Jeju

St. Paul American School Hanoi

TEDA International School

The Harbour School

Penny Blackwell

James Elliot

Sophia Anand Rao Manduri

Hana Tjong

Paul Davis

David Griffith

Kim Marantos

Christopher Randall

Thabo Metcalfe

Alice Smith School

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School

Canadian International School of Hong Kong

Canadian International School of Singapore

Dwight School Seoul

Ekamai International School

Hangzhou International School

International School Ho Chi Minh City

International School of Dongguan

International School of Qingdao

NIVA American International School

Alan Mc Carthy

Richie Morris

Karen Lindner

Angela Spiers

Nicole Nel

Angie Cordero

Jeffery Hart

Leanne Le

Keisel Escudero

Justin Crull & Colleen Quernemoen

Marle Baybay

Tianjin International School

Dani Beth Barsalou

Tokyo International School Michelle Jasinska

Tsinghua International School Rachel Rudisaile

Unity Concord International School

Daniel Loss

Utahloy International School Guangzhou Chantelle Parsons

Wuhan Yangtze International School

Lida Penn

XCL World Academy Maria Sweeney

Yew Chung Int’l School of Chongqing

Yokohama International School

Christopher Babbage, Director ICT

Henri Bemelmans, Executive Director

Nick Bevington, Head of Junior School

Daniel Brown, Director of Professional Learning and Development

Finbar Burke, School Director

Michael Callan, Director

Yael Cass, Senior Consultant & Strategist

Marwa Elgezery, Head of School

Melanie Ellis, Head of Senior School

Kevin Haggith, Head of School

Lynda Howe, Head of School

Osaka YMCA International School

Suzhou Singapore International School

Thai-Chinese International School

The Harbour School

Unity Concord International School

Yan Liu

Dave Secomb

Adam McGuigan

Edward Anaya

James Cooke

Thabo Metcalfe

John Conger

Utahloy International School Guangzhou Jai Roa

Western International School of Shanghai

XCL World Academy

Yew Chung International School of Qingdao

Yokohama International School

Yongsan International School of Seoul

Dulwich College (Singapore)

Australian International School Bangkok

Dulwich College (Singapore)

Dulwich College (Singapore)

Discovery International School

International School Kenya

EDUmasterminds

Sakura International

Dulwich College (Singapore)

Yoyogi International School

Myanmar International School Yangon

Tamara James-Wyachai, Curriculum Head - English Language Arts and Reading Sampoerna Academy Schools, Indonesia

Kenji Kiyosawa, University Counselor / Public Relations Director

Jacob Martin, Deputy Head of College

Paola Morris, Director of Business Administration

Chris Perez, Headmaster

Dominic Robeau, Head of School

Jonah Rosenfield, Founder & Executive Director

Rodita Salonga, School Director

Jan-Mark Seewald

Erica Smeltzer, Head of School

Michael Taylor, Principal

Xing Wei, Head of University Counselor

Meikei High School

Dulwich College (Singapore)

Dulwich College (Singapore)

Ivy Collegiate Academy

ABIS

Global Safeguarding Collaborative

Canadian American School

JM Seewald Consulting

BASIS International School Guangzhou

UIA International School of Tokyo

Beanstalk International Bilingual School

Fabienne Brown

Maria Sweeney

Anna Li

Dave Secomb

Becky Palisuri

ADAPTIVE

Leadership Consulting and Coaching/Board Governance/Board and Head of School Relationship/Transition Coaching for Leaders and Teams

Amplify

Publisher; education services for educators

Ascend Now Pte. Ltd. Soft Skills/University

Avallain edtech solutions provider

Benchmark Education

English Literary Programs, Early Learning, Intervention, Leveled Texts

Consilience Education Foundation Learning Data Analytics

Corwin Press Inc. K-12 Education Publishing & Consulting

College Board Advanced Placement Program

Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) Professional Development and Research

Educate Plus Membership Organisation

Hudson Global Scholars K-12 Online Education Provider

IEAC- International Education Accreditation Council UK

Accreditation of Schools, Universities and Colleges

IEXP 360

Experiential Education Specialists through Outdoors and Travel

iGNIS - the Governance Network for International Schools iGNIS facilitates and promotes good governance in international schools, whatever their ownership and governance model

Khiri Campus Educational Travel

Maryanne Lechleiter Consulting Group Student Recruitment and Enrollment Marketing Consultant

Membean edtech

Optimal School Governance Support services for school boards and leaders

OWN Education Limited Educational Event Management Company

PeerSphere Professional Development and Networking

Quizizz Education Technology

Solros Development Group Positive Organizational Development for Schools

Vidigami Education Technology

This award is presented to a student who embraces the qualities of a global citizen. This student is a proud representative of his/her nation while respectful of the diversity of other nations, has an open mind, is well informed, aware and empathetic, concerned and caring for others encouraging a sense of community, and strongly committed to engagement and action to make the world a better place. Finally, this student is able to interact and communicate effectively with people from all walks of life while having a sense of collective responsibility for all who inhabit the globe.

Access International Academy Ningbo Gulshanoi Qodirova

American International School Hong Kong Sonia He

American International School of Guangzhou Euna Jang

American School Hong Kong Chung Man (Ryan) Leung

Bandung Alliance Intercultural School Ju Eun Song

Bandung Independent School Ting Wei Lin

Brent International School Baguio Yewon Choi

Brent International School Manila Shivam Mull

Busan Foreign School Miru Eum

Canadian Academy Miranda Ancona

Canadian International School of Singapore Finn Muir

Canadian International School, Tokyo Marin Hirata

Canggu Community School Trey Eckstein

Cebu International School Ji Yeon Oh

Chadwick International School Jihyeon (Cherry) Sung

Chiang Mai International School Xinran (Emily) Xu

Christian Academy in Japan ZhiEn Huang

Concordia International School Hanoi JaeEun Koh

Concordia International School Shanghai Amy Wang

Concordian International School Chanyanuch (Mily) Sakdibhornssup

Daegu International School Selina Son

Dalian American International School Suah Lee

Dominican International School Eric Lin

Dwight School Seoul Se Hyun Ra

European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City Cavan Anden

Garden International School Kuala Lumpur Sumayyah Mohamed Rafe

Hangzhou International School Huaize (Andrew) Zhu

Hong Kong Academy Kaela Lam

Hong Kong International School Min Kyung Ariane Lee

Hsinchu International School Yunju Paek

IGB International School Jeong (Julie) Hayoon

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Katelyn You-Ying Chen

International Community School-Bangkok Yu Juan

International Community School-Singapore Zaara Baruah

International School Bangkok Nippita (Tam) Suteesopon

International School Dhaka Vanisha Goel

International School Eastern Seaboard (ISE) Yeon Joo Cheong

International School Manila Pepe Pyykko

International School of Beijing Rhea Shinde

International School of Busan Antonio Navarro

International School of Dongguan Yan-Xin Kuo

International School of Kuala Lumpur Yanqing (April) Huang

International School of Nanshan Shenzhen MinJu Song

International School of Phnom Penh Sonyta Ty

International School of Qingdao JeongWoo (Justin) You

International School Suva Latina Fatiaki

ISS International School Jiyoon (Ashley) Park

Kaohsiung American School Ellie Chen

Keerapat International School Raynhuga Nabunyareuk

KIS International School Alyssa Thai

Korea International School-JeJu Campus Seoyeon (Olivia) Choi

Korea Kent Foreign School Younghoon Ko

Lanna International School Thailand Pichada Saeheng

Marist Brothers International School Sara Koda

Medan Independent School Ethan Lau

Nagoya International School Leon Miyashita Leon Miyashita

Nanjing International School Ziqi Ye

Nansha College Preparatory Academy Mike Xiaozikang Fu

NIST International School Ava (Avanisha) Shrestha

North Jakarta Intercultural School Tanisha Dhillon

Oasis International School - Kuala Lumpur Eunchae Han

Oberoi International School Arshbir Tuli

Osaka International School Yi An Hah

Osaka YMCA International School Baum Jake Seo

Panyaden International School Thanida Jaito

Saint Maur International School Jungwoo Huh

Seisen International School Leina Pham-The (Matsuoka)

Sekolah Ciputra Shannon Melody Singopranoto

Seoul Foreign School Grace Cho

Seoul International School Wongyeom Yang

Shanghai American School-Pudong Campus Sydney Madison Lu

Shanghai American School-Puxi Campus Bo Xin Zhao

Shanghai Community Int’l School-Pudong Campus Hye-Wwon Moon

Shen Wai International School Yuelong (Alice) Huang

Shenzhen College of Int’l Education Qiaochu Ou

Shenzhen Shekou International School Sangchun Harry Yeh

Singapore American School Erin Chen

Singapore Int’l School of Bangkok Vedanth Bhandari

St. Mary’s International School Bastien Czoe Bagui

St. Paul American School Hanoi Khai Minh Nguyen

Surabaya Intercultural School Shun Sato

Taejon Christian International School Sue Hyun Kim

TEDA International School May Zhang Xin Nuo

Thai-Chinese International School Khwanchanok Paka-Akaralerdkul

Thalun International School Nang Nang Onn Hseng

The American School in Japan Arnab Karmokar

The British School New Delhi

The International School Yangon

Adiva Goel

Maggie Chang

United Nations International School of Hanoi Chaeyeon Park

Utahloy International School Guangzhou

UWC Thailand International School

Vientiane International School

Wells International School-On Nut Campus

Western Academy of Beijing

Wuhan Yangtze International School

XCL American School of Bangkok

XCL World Academy

Nayoung Oh

Margaret Gem Martinez

Agata Palentini

Krittika (Grace) Luangyot

Kwanyoung Park

Nathan Lin Xiao

Yuna Tokiwa Patimanon

Hethn Banesh

Yongsan International School of Seoul Emily Dhong

All of us here at EARCOS wish to extend our sincere congratulations to the following Global Citizens who have been chosen to receive an EARCOS Global Citizen Community Service Grant of $500 to further their excellent community work during this upcoming academic year. The recipients are:

NAME

Euna Jang

Adiva Goel

SCHOOL

American International School of Guangzhou

The British School New Delhi

Khwanchanok (JiaJia) Thai-Chinese International School

Paka-Akaralerdkul

Arshbir Tuli

Bo Xin Zhao

Hayoon (Julie) Jeong

Oberoi International School

Shanghai American School - Puxi campus

IGB International School

Suah Lee Dalian American International School

PROJECT NAME

Education for Afghan Girls

The Ourchive Project

H.E.R. (Health. Equity. Respect.)

Project Samruddhi

The Project Pathway To Freedom (PTF), under NGO Women In Need (WIN) in Sri Lanka

Debate Workshop for Government School Students

Curious Kids

Ung’s Family.

By Loung Ung

On April 17, 1975, a scorching day in Cambodia, my life and the lives of millions of Cambodians changed forever when the Khmer Rouge seized power. I was only five years old, living in Phnom Penh with my parents and six siblings. The soldiers arrived with jubilant smiles, firing their guns into the air, and ordered us to evacuate our home. Little did I know that over the next four years, the Khmer Rouge would unleash a brutal genocide, claiming nearly two million Cambodian lives—a quarter of the country’s population. This nightmare of terror, separation, and loss would define my childhood and fuel my life as an activist.

As a writer, my resolve to tell Cambodia’s stories ignited on April 15, 1998, the day the Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot died. Listening to his last interview on the radio, I was enraged by his claim that his actions in Cambodia stemmed from love. My hands trembled with fury at this grotesque distortion. Love does not harm, torture, or commit mass murder. Love does not turn children into orphans and soldiers, resulting in genocide. Love, as my parents taught me, nurtures, heals, and protects. I decided then to pen my own story of love between children and families, husbands and wives, mothers and fathers. My memoir, First They Killed My Father, was born out of this determination.

I am grateful that my small book, published in 2000, continues to resonate in classrooms and lecture halls, bringing me to the 2024 EARCOS Conference in Bangkok. There, I had the privilege of meeting many teachers and educators who, like me, refute Pol Pot’s legacy with their own stories of love. I am profoundly moved to be in your presence and grace. As educators, you are the original influencers in countless young people’s lives, creating change not only in classrooms but in life.

Like Linda Costello, my second-grade teacher, who I met when I was ten, a newly arrived refugee in America. Linda did not know Cambodia’s history, politics, or its civil wars. I could not share with her how my heart ached for my beautiful Cambodia—a lush, green land full of temples, art, and songs. A land populated by seven million Khmers, including my beloved father, mother, three brothers in bell-bottom pants, and three sisters with whom I argued so loudly that my father once threatened to replace us with monkeys. Cambodia, where I spent my days going to pagodas, parks, and movies with my family.

This Cambodia ended when the Communist Khmer Rouge took power on April 17, 1975. They sealed Cambodia’s borders and ordered us to evacuate the city. In just 72 hours, Phnom Penh, with a population of two million, was emptied. My family was among the two million Cambodians forced to abandon our homes. The Khmer Rouge aimed to create a new utopian agrarian society, banning and eliminating everything I had known and loved. For the next three years, eight months, and twenty days, we lived in villages resembling labor camps where every day was a workday, regardless of age. We built dams, dug trenches, and grew food to support a war we did not believe in. Books, schools, movies, music, markets, and temples were destroyed, banned, or abolished. We were dictated what to wear, when to sleep, eat, and work—there was no time for play.

Anyone who did not buy into the Khmer Rouge mission was deemed a traitor and enemy, to be purged from the land. Soldiers captured former politicians, civil servants, lawyers, architects, doctors, business leaders, teachers, singers, musicians, writers, and students. My family knew my father was in danger and moved from village to village, but the soldiers found us.

I will never forget the day the soldiers came for my father. I was seven and had learned that to survive, I had to remain silent. While my mother sobbed, my father lifted me up, my face resting at the nape of his neck. When he put me down, I watched him walk away with soldiers on either side, rifles slung over their shoulders.

Three months after my father was taken, my mother gathered my siblings and me and told us we had to leave her. I did not know of her fear that the soldiers would return for us. Filled with anger, I went to live at children’s camps where I was trained as a child soldier. My anger turned to hatred when a year later, the soldiers came for my mother and four-year-old sister. To this day, I do not know the exact fate of my father, mother, and sister, only that their bodies likely lie in one of the 20,000 mass graves scattered across Cambodia. Forty years later, I continue to pray their deaths were swift and painless.

My war ended on January 7, 1979, when Vietnamese forces overthrew the Khmer Rouge. A year later, my brother Meng, sister-in-law Eang, and I arrived in America as refugees. I met Linda that same day, a child full of hurts, fears, and distrust of the world. With her kind smiles, Linda taught me to read and took me on a magical trip to the Brownell Library. Suddenly, I was embarking on grand adventures across the universe! For a few hours, I escaped the soldiers to solve mysteries with Nancy Drew or The Hardy Boys. But wars do not end because you leave them; they follow you into your sleep, reemerging while you stare at the fireworks on the 4th of July.

Sensing my growing darkness, Linda’s husband, George Costello, a middle school principal, gave me a book that altered my life:Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. From this, I discovered the Holocaust and logotherapy, and began documenting my experiences in journals. With each word, I reclaimed my voice and courage. In tenth grade, I wrote an excerpt of my story for a class assignment. The following week, Mr. Severance, the English teacher, returned my paper with an A++ grade. I could not believe my eyes! I had never received

such a grade and was certain there had been a mistake. With a racing heart, I approached Mr. Severance after class. He looked at me with compassion. “Sometimes the content of your story matters more than its correct words,” he said. “And I hope you keep writing.”

Mr. Severance’s words stayed with me when I returned to Cambodia in 1995 and met landmine victims who often struggled to articulate their pain and horrors. Landmines devastate communities, with millions still buried across a third of the world’s nations—weapons of slow-motion mass destruction. Upon returning to the US, I joined the Campaign for a Landmine-Free World as its spokesperson. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote, “It is not enough to talk about peace, one must believe in it. And it isn’t enough to believe in it. One must work on it.”

Three decades have taught me that peace is not an abstract concept but a series of deliberate, courageous actions we choose every day. It begins with us, requiring consistent, intentional acts to create a better world. Sometimes, it’s a kind word, a book, or a trip to a library. Other times, it’s a small act of kindness or a challenging assignment that builds

into monumental change. The impact of these actions, like those from Linda, George, and Mr. Severance, shapes futures and shows we care. In today’s world, this is the love story that opens hearts, transforms minds, and lights the way to a more just, beautiful, and safe world. This light is within all of us; we just need to choose it.

Loung Ung is a prominent activist, bestselling author, and co-screenplay writer of the 2017 Netflix film First They Killed My Father, based on her memoir. Loung has made over 40 trips to Cambodia and has delivered keynote addresses at numerous venues in the United States and internationally, including Philips Exeter Academy, Singapore American School, Harvard University, and Stanford University. For additional information, visit www.LoungUng.com.

By Kristi Williams

Governance is a critical component for any organization, providing the essential foundation, structures, and processes necessary for effective decision-making, accountability, and sustainability. In the context of international schools, the importance of governance is heightened due to the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the diverse and global nature of international education.

Effective governance in international schools goes beyond the basic framework; it becomes a strategic imperative for ensuring the institution’s success in fulfilling its mission. The complexities involved in managing a diverse student body and navigating international standards, within different local contexts, necessitate governance structures that can guide the institution through dynamic challenges using international best practices.

International schools are often subject to unique host country politics, insecurity, and inequities, adding an additional layer of complexity to governance responsibilities. The role of governance in international schools extends beyond oversight; it becomes a driving force for shaping the educational experience, fostering global citizenship, and preparing students for an interconnected world.

Additionally, in most international school boards, board positions are filled with well-intentioned parents that want the best for their children. Most of these well-intentioned parents don’t fully understand the responsibility of the board and how the focus of the board is on the future of the school. The Board is solving to support, sustain, improve, and grow the school for students enrolled in next 3 -10 years, not for students enrolled today.

As such, the importance of effective governance in international schools lies in the ability to provide vision, stability, and adaptability necessary for schools to thrive amidst the complexities of a globalized educational landscape.

This is the first installment of a three article series. The series will look at the role of Boards at international schools and the need to re-evaluate their composition, diversity, skills, and experiences to build and sustain a board for long-term stability.

In the complex landscape of international education, governance serves as the cornerstone for ensuring excellence, sustainability, and accountability within educational institutions. Governance encompasses a multifaceted approach that involves strategic planning, oversight, and stewardship to navigate the diverse needs of students, faculty, parents, and other stakeholders.

Governance in international schools encapsulates the structures, policies, processes, and practices that guide decision-making and operations to achieve the school’s mission and vision. It entails fostering a culture of transparency, integrity, and ethical conduct while upholding educational standards and promoting the holistic development of students.

Effective governance establishes clear lines of authority, delineates responsibilities, and fosters collaboration among stakeholders to drive continuous improvement and innovation.

Highly effective boards are able to lead with the following good governance practices:

• Visionary Leadership: Governance provides visionary leadership that anticipates future trends and challenges. This leadership helps the school develop long-term plans that align with its mission and vision while being responsive to changes in the educational environment.

• Data-Driven Decisions: Effective governance relies on data-driven decision-making. This involves collecting and analyzing data on student performance, enrollment trends, financial health, and other key metrics. Data-driven decisions are more likely to be effective and sustainable.

• Stakeholder Input: Including input from stakeholders in the decision-making process ensures that the school’s strategic plans reflect the needs and priorities of the community. This input can be gathered through surveys, focus groups, and advisory committees.

• Scenario Planning: Governance involves scenario planning to prepare for different future possibilities. This planning helps the school develop contingency plans and remain flexible in the face of uncertainty.

Governance is about developing clear parameters and guidelines for which the school operates and for the community to behave.The board of international schools, set the policies for the existence, authority, and operations.

Policies are parameters that guide decisions, actions, and behaviors in fulfilling a school’s mission and strategic goals. Policies establish standards, principles, and rules that govern aspects of governance, operations, and conduct within the school and among all stakeholders, such as faculty, students, and parents. They provide a framework for decisionmaking, resource allocation, and problem-solving, ensuring consistency, fairness, and accountability.

The Board’s role is to develop, maintain and update school policy documents to ensure alignment with the school’s mission and vision, alignment with school practices, alignment with global best practices, and alignment with local government cultures and regulations.

Having good policy documents in place ensure effective governance, compliance with regulations, and behavioral expectations for students, faculty, parents, and stakeholders.

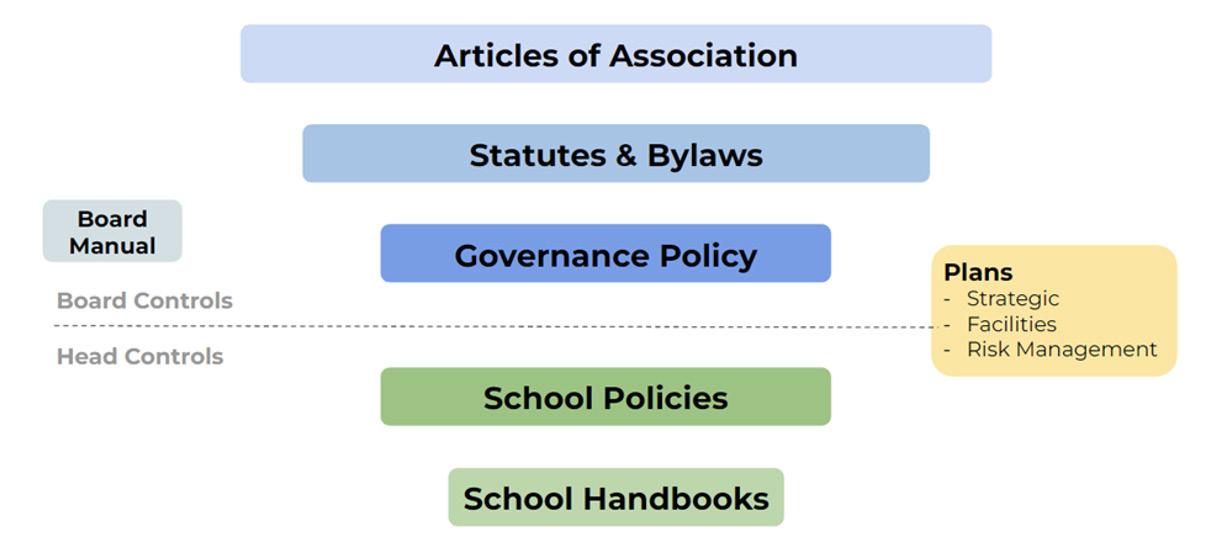

The Board has ownership of the following policy documents: 1. Articles of Association or Founding Charter

Statutes and or Bylaws 3. Organization Policies

Board Manual

Strategy Plans

Figure 1. Governance Document Hierarchy

Articles of Association or Founding Charter

The articles of association provide a legal framework for the organization’s operation, ensuring clarity, transparency, and accountability in its governance and functioning. They establish the rights, obligations, and relationships of the organization’s stakeholders and for complying with legal requirements and regulations governing its activities.

They serve several important purposes such as:

1. Establish the School’s Structure

2. Set out Association Member’s/Board’s/Employee’s Rights and Obligations

3. Regulate Board and Officer Conduct

4. Provide a Framework for Decision-Making

5. Protect Association Interests

6. Provide a Legal Framework for Operations

Many times, the articles of association were first written at the founding of the school 30, 40 or 50+ years ago and require a vote by Association Members. It’s important for Boards to ensure that the articles are up to date with evolved processes, practices, and regulations at the school and within the host country.

Statutes establish the fundamental principles, legal framework, and governance structure of an organization, such as an international school. Statutes serve as foundational documents that define the organization’s existence, purpose, powers, and operational guidelines.

While similar to articles of association, statutes can be more specific and detailed to complement the articles. Some schools opt to not use Statutes.

Bylaws provide detailed rules and procedures for the internal governance and operations of the Board. Bylaws complement statutes or articles by elaborating on the broad principles established in the organization’s governing documents and providing specific guidelines for its functioning.

School policies play a crucial role in guiding, regulating, and supporting organizational activities, promoting compliance, accountability, transparency, efficiency, and innovation. They contribute to the overall effectiveness, integrity, and sustainability of the organization, enhancing its reputation, performance, and impact.

There are typically two types of policies – Governance Policies and School Policies. governance policies establish the overarching framework for effective leadership, decision-making, and accountability within the school, while school policies address specific operational and ad-

ministrative matters that directly impact the day-to-day functioning of the institution.

• Scope: Governance policies focus on the overarching principles, structures, and processes that guide the strategic direction, decision-making, and accountability of the school. They establish the framework for effective governance and leadership within the institution.

• Focus: Governance policies address matters related to the school’s mission, vision, values, goals, and long-term strategic priorities. They define the roles, responsibilities, and authority of the governing body (e.g., board of trustees, board of directors) and its relationship with school leadership (e.g., head of school).

• Scope: School policies address specific operational, administrative, and instructional matters that directly impact the day-to-day functioning of the school. They govern a wide range of activities and areas within the institution.

• Focus: School policies cover various aspects of school operations, including academic programs, student behavior, staff employment, facilities management, safety and security, student services, extracurricular activities, and more. They are designed to ensure consistency, fairness, and compliance with legal and regulatory requirements.

The role of the board is to provide a governance policy framework that provides clear overarching principles and goals, supported by more detailed guidelines or regulations that specify how those principles should be applied in practice. This allows for flexibility and adaptability while still ensuring clarity and consistency in implementation. The level of specificity in a policy should be determined based on the nature of the issue, the needs of stakeholders, and the goals of the policy itself.

Boards need to ensure there are sound governance policies that address a specific problem or issue effectively while considering its broader impact on society. The ideal approach is to have a policy framework that provides clear overarching principles and goals, supported by more detailed guidelines or regulations that specify how those principles should be applied in practice. This allows for flexibility and adaptability while still ensuring clarity and consistency in implementation.

Installment 2 will focus on the specific roles and responsibilities of boards and board members in particular in setting the direction, managing fiduciary risk and in overseeing management.

Kristi Williams is a recognized leader in partnering with international and independent schools and non-profit organizations to empower boards, leaders, and teams.

Kristi specializes in empowering boards to optimize governance, shape policy, and develop board members’ capacities to make an impact. Her experience in strategic planning ensures boards and schools are equipped for success and stability in today’s dynamic environment. Kristi is a Board Governance Trainer authorized by the US State Department Office of Overseas Schools and a CIS Affiliated Consultant

Email: Williams.kristi@gmail.com LinkedIn

By Terry Roberts, National Paideia Center troberts@paideia.org

The phrase “critical thinking” is everywhere in education, yet it was not that long ago when we struggled to define the term. In a 2008 article in Educational Leadership, a colleague and I wrote about the struggle to teach and even measure cognitive skills. In doing so, we offered the following definition of critical thinking:

The ability to successfully explain and manipulate complex systems. By system, we mean a set of interrelated ideas, often represented by a human artifact. As students learn to think, they are able to explain and manipulate increasingly complex systems containing many discrete elements and complex relationships. (Roberts & Billings)

We went on to explain that the curriculum was full of what we were calling “systems,” across all grade levels and subject areas. “A folktale by the Brothers Grimm, the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, and a word problem in algebra … the periodic table of the elements”—all complex systems.

I recall that definition here to address a similar problem that we now face with the phrase creative thinking. It is increasingly in use by educators and often as if its meaning is both clear and widely accepted. Neither is the case. To move forward, we need to define it in a way that is both clear and useful. To that end, I would offer that:

Creative thinking is the ability to generate and portray new and compelling versions of complex systems, often by rearranging the elements in those systems or by combining multiple systems in novel and meaningful ways.

This definition of creative thinking uses many of the same terms as our 2008 definition of critical thinking and acts in a complementary way. It suggests that the students in our classrooms can go beyond the analysis of the systems developed by others into an arena where they learn to produce their own.

The first element of our definition of creative thinking is “the ability to generate and portray.” These two words—generate, portray— represent a vital shift in our current thinking about the classroom because the prevalence of standardized testing has created a culture of convergent thinking in most public schools. This trend exists in despite of a slowly growing interest in creativity. In 2001, a group of cognitive psychologists updated Benjamin Bloom’ classic taxonomy in a hierarchy titled “A Taxonomy for Teaching, Learning, and Assess-

ment.” The new version listed remember, understand, and apply at the bottom of the taxonomy followed by analyze and evaluate, all of which mimics the original version. What is significant, however, is that the highest form of thinking in the 21st century version is to create. The authors go on to describe this cognitive skill as the ability to “produce new or original work,” listing as examples to “design, assemble, construct, conjecture, develop, formulate, author, investigate” (Armstrong, 2010). All of these verbs are examples of the “ability to generate and portray” that goes beyond the critical skills of analysis and evaluation.

The phrase “new and original work” from the 21st century Bloom anticipates the next element in our definition of creative thought: “new and compelling versions of complex systems.” A critical thinking approach to cognition in the classroom typically stops with a detailed analysis of a text of some sort (poem, speech, math problem, science experiment, map, photograph, etc.) that is relevant to the curriculum. Occasionally, analysis even leads to evaluation of the text, but the key element is that the text under consideration was produced by someone other than the students.

Creative thinking picks up where critical thinking leaves off in that it often asks students to go beyond analysis or even evaluation to produce works of their own that expand the curriculum. For example, a creative thinking approach asks them to write a poem, give a speech, construct a math problem, design an experiment, take a series of photographs, and so on. The National Paideia Center’s seminar plan for the traditional Periodic Table of the Elements requires students to design other ways (in three dimensions as well as two) to represent the elements heretofore discovered or manufactured by scientists. Their task: to represent the relationships more accurately between and among the elements so that the entire “table” is portrayed in a “new and compelling version.”

As you can see from this example, students would respond by “rearranging the elements in the system” that is the periodic table in ways that are not just novel but also meaningful. This same form of creative expression would be in play when students designed new number systems in mathematics, created new poetic forms in English, constructed new experiments based on classic examples in science, and investigated historic events through new perspectives in social studies. To take the example of the Periodic Table one step further, imagine a Paideia Seminar on twin texts: the Table of the Elements and a landscape painting. Students would analyze the ways in which these two representations of nature are alike and different, and in so doing, would discover the surprising number of similarities between the two. In addition, they might evaluate which of the two “systems” (table or painting) is most useful and in what circumstances. The post-seminar challenge for students would be to design a “system” that combined elements of both visual art and scientific classification. Creative thinking naturally leads to creative expression.

Seminar dialogue is a key ingredient in teaching creative thinking as we have defined it here. The Paideia Seminar cycle is more than just the actual classroom discussion; it includes the pre-seminar work that set the stage for the discussion as well as the post-seminar work that gives students the opportunity to build from the discussion. The entire cycle consists of five steps:

• pre-seminar content activities,

• pre-seminar process activities,

• formal seminar dialogue,

• post-seminar process activities,

• post-seminar content activities.

The pre-seminar content activities involve multiple close “readings” of the text, even when the text is nonverbal (a work of visual art, a diagram, a map, etc.) as well as background study and vocabulary development. The pre- and post-seminar process activities involve students setting speaking and listening goals both for themselves as individuals and for the group (pre-seminar); and then assessing their relative success in meeting those goals (post-seminar). The post-seminar content activities involve the students expressing themselves in writing or some other form of creative expression appropriate to the curriculum and the text.

See, for example, how these five stages in the seminar cycle play out in the seminar designed for Marc Chagall’s “I and the Village” from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (https://www.moma.org/collection/works/7898 ). This particular plan is for upper elementary grades, but we have developed a similar plan for adults, so that this colorful and evocative painting could be the basis for a faculty or parent seminar as well as a student seminar. As you can see, the pre-seminar content work invokes the students’ natural curiosity and creativity, the seminar discussion inspires a wide range of creative response, and the post-seminar content work invites students to express their own vision of the world in which they live. Notably, this seminar could be used in a social studies or math context as well as an art class. In fact, creative discussion and expression often involves breaking down artificial subject area distinctions—for the teacher as well as the students.

In the Chagall seminar, as well as other creative seminars, the actual discussion is facilitated by open-ended questions that are designed to elicit as wide a variety of “right” answers as possible. Each student is then able to juxtapose the perspectives of others with their own original insights so that as the conversation goes forward, the thinking of each is enriched by that of all. The result is not consensus. The students are never asked to arrive at the same conclusions as their peers about the text, only that their understanding is now more complex and more sophisticated. As I argued in an earlier Educational Leadership article on this subject, the goal is divergent rather than convergent thinking (Roberts, 2019).

Rich and divergent conversation, however, is not enough to guarantee that most students will grow in their ability to “generate and portray new and compelling versions of complex systems.” Creative conversation is often best generated by creative texts. In addition to Chagall’s “I and the Village,” examples abound: the use of a quilt as a geometry text in an elementary math class; a collage by Romare Bearden in a middle school social studies class, the “Beaufort Wind Scale” in a high school biology class, Emily Dickinson’s “I years had been from home” in a middle or high school language arts class. All these texts are themselves imaginative works by creative individuals, and most do not give up their meaning easily. In fact, they require creative as well as critical examination and discussion.

A consistently generative seminar text has at least two important characteristics. First, they are rich in complex ideas and values, which

means in turn that there is a lot to consider intellectually and a lot to discuss conversationally. This richness invites more students to engage with the text and on a deeper level. Second, a creative seminar text is profoundly ambiguous. It can be legitimately interpreted in many different ways. When teachers are attempting to choose a text that will inspire a creative response from their students, they should consider first how many attributes of the text there are to discuss; and second, how many different interpretations does the text inspire and reward. What is important from the students’ perspective is that richness and ambiguity reward their extended attention in a way that didactic texts do not. Creativity is not boring.

Rich and ambiguous texts also lead quite naturally to seminar participants using the texts as exemplars for their own creative efforts post seminar. Imagine elementary students using a wide variety of geometric shapes in vibrant colors to create quilt designs; middle school students working with the art teacher and in collaboration with their social studies teacher to create collages that capture the essence of their own community; high school biology students designing observational scales to measure the unseen elements of the natural world; or high school students publishing an anthology of poetry that examines the intricacies of their inner lives. Returning to “I and the Village,” note that the “Writing Task” in the seminar plan asks students to express themselves with color instead of words and to use Chagall’s painting as a model for their own. All these modes of expression—quilt design, visual art, observational scales, poetry— require creative thought on the part of students that is inspired by discussion and honed through expression.

As you can imagine, the seminar cycle as it’s portrayed here takes time. It requires more than a single class period or a once-per-week experience with the art teacher. For that reason, many teachers are intimidated by the seminar cycle and struggle to imagine how to use it in their classrooms. The answer is to integrate the various steps in the cycle into the life of the classroom over multiple days, so that pre- and post-seminar content work—as well as the seminar itself— can be accomplished over a week or more in a way that engages students with a large and important part of the curriculum.

Schools and classrooms that nurture creativity across the broad range of human endeavors have several important characteristics. As I portrayed them in The New Smart: How Nurturing Creativity Will Help Children Thrive (2019), these schools feature cross-curricular and multidisciplinary work, students working together on long-term projects, quality student production and performance, and learning experiences that foster resilience and focus. And most important of all, they consistently use seminar dialogue to inspire creative expression. Seen in this context, teaching creative thinking in schools will require a paradigm shift on the part of many educators who are only now adjusting to the idea of teaching thinking at all. The notion of integrating creative discussion into all phases of schooling requires something special. It requires creativity on the part of teachers and administrators.

Ultimately, a school that nurtures creative thinking exhibits a deliberate and consistent dedication to active student learning balanced by active student reflection. Another way to say this is that a school for creativity uses the Paideia seminar cycle to free teachers as well as students to think and express themselves creatively.

I am a lifelong public school educator. In a parallel life, I am a novelist, which may explain why I have spent the last thirty-plus years thinking about the schooling that precedes a creative life. What has become increasingly obvious during that time, however, is that the world in which our students will live their adult lives will require more of them than the linear, “critical” modes of thinking that we have traditionally taught. If anything, as that world grows more complex and volatile, it will require a non-linear, creative response from those who thrive. The creative mind will eventually replace the critical mind on the world’s stage.

Seen in this perspective, anything we can do to prepare students for that world is of vital importance. It’s imperative that we teach our students to converse in ways that generate new and compelling insights, that we free them to ask new questions leading to unexpected answers. Creativity is not an option; indeed, it may be the only path forward.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [10/2/2022] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Gardner, H. (1983). Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi. Basic Books.

Roberts, T. (2020). Opening up the Conversation and student thinking. Educational Leadership, 77(7), 52-57.

Roberts, T. (2019). The new smart: How nurturing creativity will help children thrive. Nashville, TN: Turner.

Roberts, T., & Billings, L. (2008). Thinking is literacy, literacy thinking. Educational Leadership, 65(5), 32-36.

Dr. Terry Roberts is a lifelong teacher and educational reformer as well as an award-winning novelist. As a student of intellectual history, he is fascinated by the power of dialogue to inspire critical and creative thinking. Since 1992, he has been the Director of the National Paideia Center, a non-profit school reform organization dedicated to making intellectual rigor accessible to all children. In addition to five celebrated novels, he has written extensively about public education, notably The Power of Paideia Schools, The Paideia Classroom, and Teaching Critical Thinking: Using Seminars for 21st Century Literacy (with Laura Billings). His most recent book is The New Smart: How Nurturing Creativity Will Help Children Thrive (2019, Foreword by Howard Gardner), in which he defines the sort of individual who will thrive in the year 2050, and how our schools can nurture that person.

By James H. Stronge1,2, Leslie W. Grant1, Swathi Menon1, & Altaf Khosa1

1 William & Mary School of Education; 2Stronge & Associates Educational Consulting

So Why Is Teacher Effectiveness Research So Important for International Schools?

In this article, we focus on the interaction between teachers and their students. Specifically, we ask: Who directs the learning in the classroom – teachers or students? No doubt we all have heard discussions or read an article of whether a teacher is a “sage on the stage” or a “guide on the side” with much of the discussion discouraging the former and encouraging the latter (Morrison, 2014; Sarkar Arani et al., 2019; White-Clark et al., 2008). We were curious as to what we would find in international school teachers’ classrooms.

What Teachers (and Students) Did We Study?

We conducted multiple teacher effectiveness studies over the past 10+ years in U.S. and China government-supported (i.e., public) schools. We started by studying national and regional award-winning teachers in both countries and, later, expanded to include teachers identified as effective in teaching predominantly with at-risk children and youth (e.g., rural western China students from minority language/culture backgrounds; border, highly mobile, and economically disadvantaged U.S. students). In total, there were 66 teachers included in the combination of these studies (Grant, et al., 2013; Xu, et al., 2022).

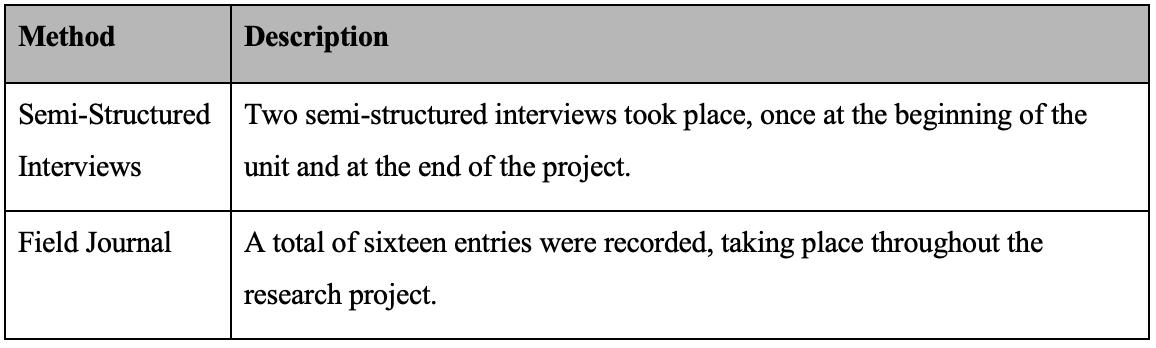

To launch this most recent project, we selected teachers from East Asian schools (predominantly EARCOS schools) to participate in a field-based study in which by visited the teachers’ schools and explored their teaching contexts, observed their teaching, and interviewed them to discover more about their beliefs and practices for effective teaching. The teachers were nominated by their school leaders as being highly effective teachers based on their work in their schools. We aimed for representativeness across grade levels, subjects taught, and large/small school inclusion. Ultimately, we selected 30 teachers from six countries and 11 schools in Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam) and 11 schools to compose the maximum variation sample. Thus, in total, we report on 96 teachers drawn from the U.S., China, and East Asian international schools for the total sample. A graphic of with whom the multiple studies were conducted is depicted in Figure 1.

The short answer is teachers: In the highly effective teachers’ classes that we included in the various studies, the teachers consistently organize and orient the classroom plan with them as directors of

the learning. In the multiple studies we conducted, we used the same data collection protocol to assess the degree to which the teachers

or students direct the learning in the classrooms, using a rating scale with a continuum of 1-5, with 1 indicating that the teacher directs all learning and 5 indicating that students direct all the learning. The protocol was applied in each classroom repeatedly in 5-minute increments with two trained observers recording their observations and, following the classroom visits, reaching consensus about the agreed-upon ratings.

Now, look at Figure 2 and view the columns that provide the average for each group of teachers and for the total group of teachers. You will see the data revealed that the teachers in all three groups directed the learning. Comparative analysis indicated that the international (M= 1.87) and U.S. (M = 1.73) teacher groups were less teacher-directed than the China (M = 1.34) teacher groups. Although the China teachers were statistically significantly different (more teacher-directed) from the U.S. and international teachers, that isn’t the major finding here. The first real finding here (and perhaps our biggest surprise when we first started the effective teacher studies) is that all groups – regardless of whether the teachers were in government versus independent schools, Asia or U.S. locales, lower, middle, or upper schools, or any other variable we considered, the findings were remarkably consistent with the overall mean being 1.57. And remember, on a 5-point scale a “1” means the teacher directs all learning.

Figure 2. Who Is the Learning Director in Highly Effective Chinese, U.S., and International School Teachers’ Classrooms?

The Learning Director was rated on a five-point scale as a continuum of 1) teacher directs all the learning to 5) student directs all the learning engagement.

We know this finding of teacher directedness runs completely counter to much of the professional literature in education, but the clear fact remains: In our intensive investigation of 66 teachers across U.S. and China government-support schools, and 30 international independent schools in East Asia, we consistently found that the teachers were the directors of the learning. They prepared the lessons – and even, in some instances, designed or adapted the curriculum; they implemented the instruction based on why they knew (or believed) students should know and be able to do and, they assessed the students’ learning. And, overall, the teachers were in charge of the learning.

A key finding in this investigation of who directs classroom learning is that teacher direction does NOT eliminate student-centeredness. As we noted at the beginning of the article, the educational literature is replete with cautions about teachers being the proverbial “sage on the stage” and encouragement for teachers to be the “guide on the side.” We found this paradigm, at least with the 96 teachers in the multiple studies included in this research, simply didn’t hold up. In fact, it proved to be a false dichotomy for how effective teachers plan for teaching and how they actually teach. We want to be very clear about what we observed – the teacher directing the learning did not mean that the teachers were in front of the students lecturing during the entire lesson. What we observed were instructional activities -- a combination of whole group, small group, and individual -- that were carefully planned and orchestrated by the teacher.

Of course, there were some exceptions for some lessons – and for portions of some lessons – when the teachers provided more student choice. However, what we observed and what we heard from the teachers when we interviewed them was that they came to their teaching with a deep understanding of what and how to teach in their assigned grades or subjects - whether that was with an International Baccalaureate, Advanced Placement, Cambridge, or some other curriculum design. But that wasn’t the guiding feature of their being the directors of learning; instead, they held the students at the very center of thinking about, planning for, and implement-

ing teaching practices. When we analyzed the totality of all words spoken by the 30 international school teachers in the interviews we conducted with them, the following word graph emerged (Figure 3):

Frequency Map of Words Used Most Frequently by International School Teachers

Not only did the international school teachers talk about their student focus far more than any other topic, in lesson after lesson we found the teachers focusing on the learning needs of the students. Thus, it wasn’t the curriculum that guided them; it was the students. Essentially, the teachers created classroom learning experiences that were built on student-focused needs and teacher expertise. In the interview, we asked teachers to share with us the characteristics that make a successful international school teacher. One teacher summed up this student-centered focus well: Someone who is willing to grow, willing to get to know the students, and willing to make changes that best fit the students’ needs.

References

Grant, L.W., Stronge, J.H., & Xu, X. (2013). A cross-cultural comparative study of teaching effectiveness: Analyses of award-winning teachers in the United States and China. Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 25(3), 251 - 276. https://dx.doi.org/ doi:10.25774/w4-m1vm-2c33

Morrison, C. D. (2014). From “Sage on the Stage” to “Guide on the Side”: A Good Start. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.20429/ ijsotl.2014.080104

Sarkar Arani, M. R., Lander, B., Shibata, Y., Kim Eng Lee, C., Kuno, H., & Lau, A. (2019). From “chalk and talk” to “guide on the side”: A crosscultural analysis of pedagogy that drives customised teaching for personalised learning. European Journal of Education, 54(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12340

White-Clark, R., DiCarlo, M., & Gilchriest, N. (2008). “Guide on the side”: An instructional approach to meet mathematics standards. High School Journal, 91(4), 40.

Xu, X., Grant, L.W., & Stronge, J. H. (2022). Dispositions and practices of effective teachers: Meeting the needs of at-risk minority students in China. Chinese Education and Society, 55(3), 147 – 164.

By By Jo Fisher, Kevin Hoskins, and Mimi Stephens Brown University’s Choices Program

Teaching about war in a meaningful way can be challenging as educators attempt to interest students in the study of events that often seem distant and unrelated to their lives. The Choices Program at Brown University has developed an innovative and engaging threepart framework for teaching the history of U.S. military conflicts that can be applied to many wars taught in secondary-level courses. This approach was presented at an NEH Institute last year and can be seen in Choices’ award-winning curriculum unit on the Vietnam War.

EARCOS members can learn about this framework and try out the Choices Program’s curriculum unit The Vietnam War: Origins, History, and Legacies in their classrooms, thanks to an EARCOS webinar being hosted on Saturday, October 19, 2024, at 9 am HKT. Register now to secure your spot.

The new framework links scholarly debates regarding the causes of American wars with primary source analysis of the experiences of diverse groups of people. It investigates both veterans’ personal memories of their service and the politicized nature of Americans’ collective memories of war. This approach pulls students into personal stories in a way that makes the history meaningful and more relatable to their lives.

The Choices Program’s curriculum The Vietnam War: Origins, History, and Legacies provides a tangible and practical example of how to implement this framework in the classroom. The curriculum tells the “long history” of the destructive, deadly, and divisive U.S. war in Vietnam by tracing its long-term origins and assessing its ongoing consequences. It looks backward toward the history of French colonialism in Southeast Asia, the evolution of the Vietnamese nationalist movement, and the First Indochina War/Anti-French Resistance War. In this manner, students are exposed to historical events that lay the ground for the U.S. war in Vietnam. It also looks forward from the end of the U.S. war in Vietnam to examine the experiences of Vietnamese refugees and to reflect on the conflict’s effects on Vietnamese and American societies long into the future.

The curriculum unit tells personal stories and experiences from all sides of the conflict and initiates students into the study of historical memory, both veterans’ memories and collective memories of war. The unit integrates new voices and perspectives, many of which had not previously been included in any secondary-level curriculum on the Vietnam War. These new and multiple viewpoints support students’ understanding of the contested legacies and discourse on the long-term effects of the war.

The framework’s “long history” approach is evident in the curriculum unit’s organization. Part I begins with French colonialism and Vietnamese nationalism and takes students through President Johnson’s decision to engage the United States in war in 1965. Part II of the unit focuses on the U.S. war in Vietnam, while Part III dives into the aftermath of the war and its effects in the Southeast Asian region and the United States.

Call-out boxes and quotes are found throughout the unit that describe experiences and viewpoints of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians. A key lesson in Part III provides students with oral histories of Vietnamese refugees and their eventual resettlement in the United States.

All of the lesson plans in the curriculum strive to immerse students in a more complex and nuanced view of the war. For example, the “Women, Gender, and the Vietnam War” lesson investigates American and Vietnamese women’s views, opinions, and experiences from the U.S. war in Vietnam. Small groups of students analyze primary sources from all sides of the Vietnam War and work to identify connections across the sources.

The Vietnam War highlights recent scholarship in Vietnamese Studies, U.S. history, and the history of the global Cold War. The curriculum includes a 74-page Student Text of readings as well as a 78-page Teacher Resource Book that contains seven ready-to-implement lesson plans, along with graphic organizers and two study guides for each part of the Student Text.

Christian Appy, Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and one of the most influential U.S. historians of the Vietnam War, praised the curriculum unit for “reflect[ing] a deep immersion in relevant scholarship.” He proclaimed it “the most sophisticated presentation of information and analysis on the war written for a high school audience that I’ve ever read.”

The Vietnam War: Origins, History, and Legacies received the 2024 Buchanan Prize from the Association for Asian Studies. The prize is awarded annually to recognize an outstanding pedagogical, instructional, or curriculum publication about Asia designed for K-12 or college undergraduate instructors and learners.

This is the third time that the Buchanan Prize has been awarded to the Choices Program. The award is granted to a curriculum that reflects “current scholarship as well as innovative pedagogical methodologies that emphasize student-centered learning and skill development.” The Choices Program received the award in 2012 for The United States in Afghanistan and in 2014 for Indian Independence and the Question of Partition.

By Gisou Ravanbaksh

In January of 2023, when China finally ended its quarantine requirements for those entering, it signified the end of an era – no more daily Covid tests, no more mandatory masks, no more health apps and no more long periods of separation from our loved ones overseas.