The EARCOS Triannual JOURNAL

A Link to Educational Excellence in East Asia FALL 2023

Featured in this Issue

Service Learning

Farming Nagomi

Unveiling the Transformative Tapestry: Where Collaboration Meets

Community-Inspired Beginnings

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

Leading Strategic Change: Building A Culture Of Inclusion

Instructional Coaching

The Social Mind at Work in the Classroom

THE EARCOS JOURNAL

The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruction, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

OBJECTIVES AND PURPOSES

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

EARCOS BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou), President

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School),Vice President

Rami Madani (International School of Kuala Lumpur),Treasurer

Elsa Donohue (Vientiane International School), Secretary

Margaret Alvarez (WASC / ISS International School), Past-President

James Dalziel (NIST International School)

Karrie Dietz (Australian International School Singapore)

Gerald Donovan (North Jakarta Intercultural School)

Jim Gerhard (Seoul International School)

Gregory Hedger (The International SchoolYangon)

Andrew Hoover (Office of Overseas Schools, REO, East Asia Pacific)

EARCOS STAFF

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director

Kristine De Castro, Assistant to the Executive Director

Maica Cruz, Conference Program Coordinator

Ver Castro, Membership & I.T. Coordinator

Edzel Drilo, Webmaster, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator

Robert Sonny Viray, Accountant

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Assistant

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

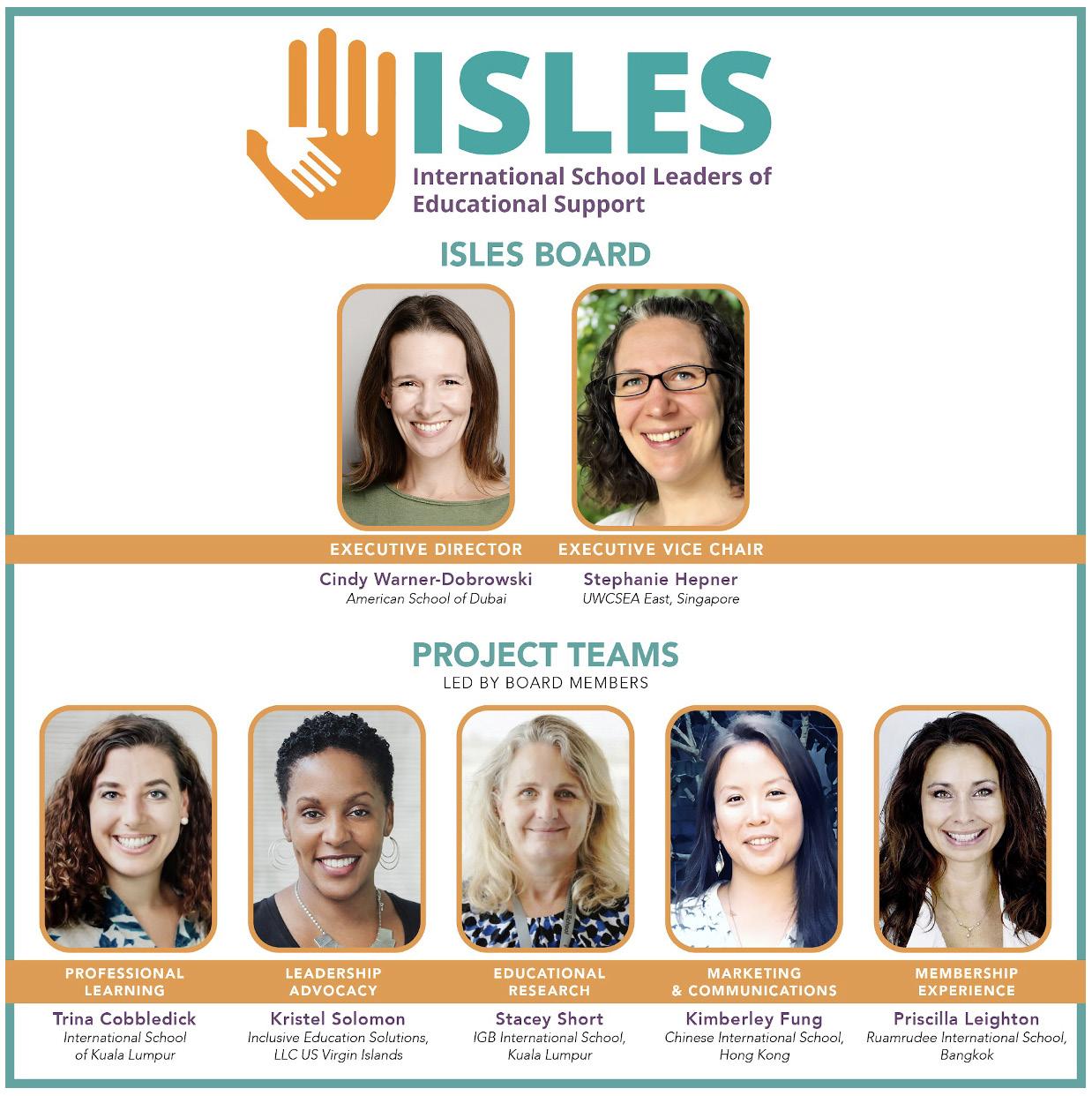

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

In this Issue

38 International Taskforce on Child Protection MAKE THE CALL! Verifying References: An Essential Practice for International School Leaders

By Jane Larsson & Pauline O’Brien

40 School Change

Connecting Key Elements to Rapidly Transform Schools

By Brian Lalor

Unveiling the Transformative Tapestry: Where Collaboration Meets Community-Inspired Beginnings

By Raquel Acedo-Rubio

By Mark William Barnett

16 MTSS

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support Leading Strategic Change: Building A Culture Of Inclusion

By Johanna Cena, Cheryl Hordenchuk, and Nitasha Crishna

18 Instructional Coaching

The Social Mind at Work in the Classroom

By

Michelle Garcia Winner

20 Project-based Learning

Using Purpose Learning to Increase Belonging in the Classroom By Jessica Catoggio

24 School Experience

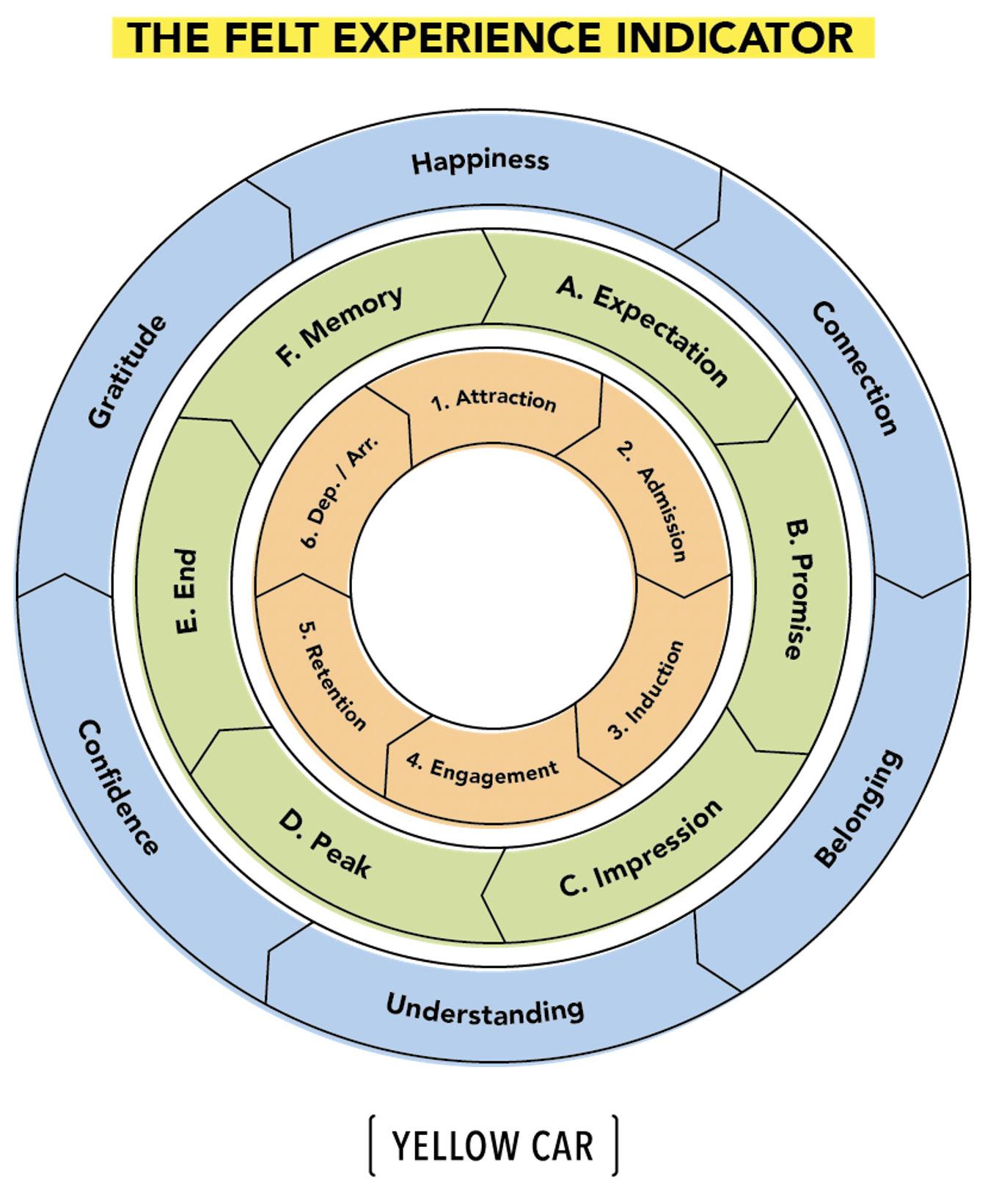

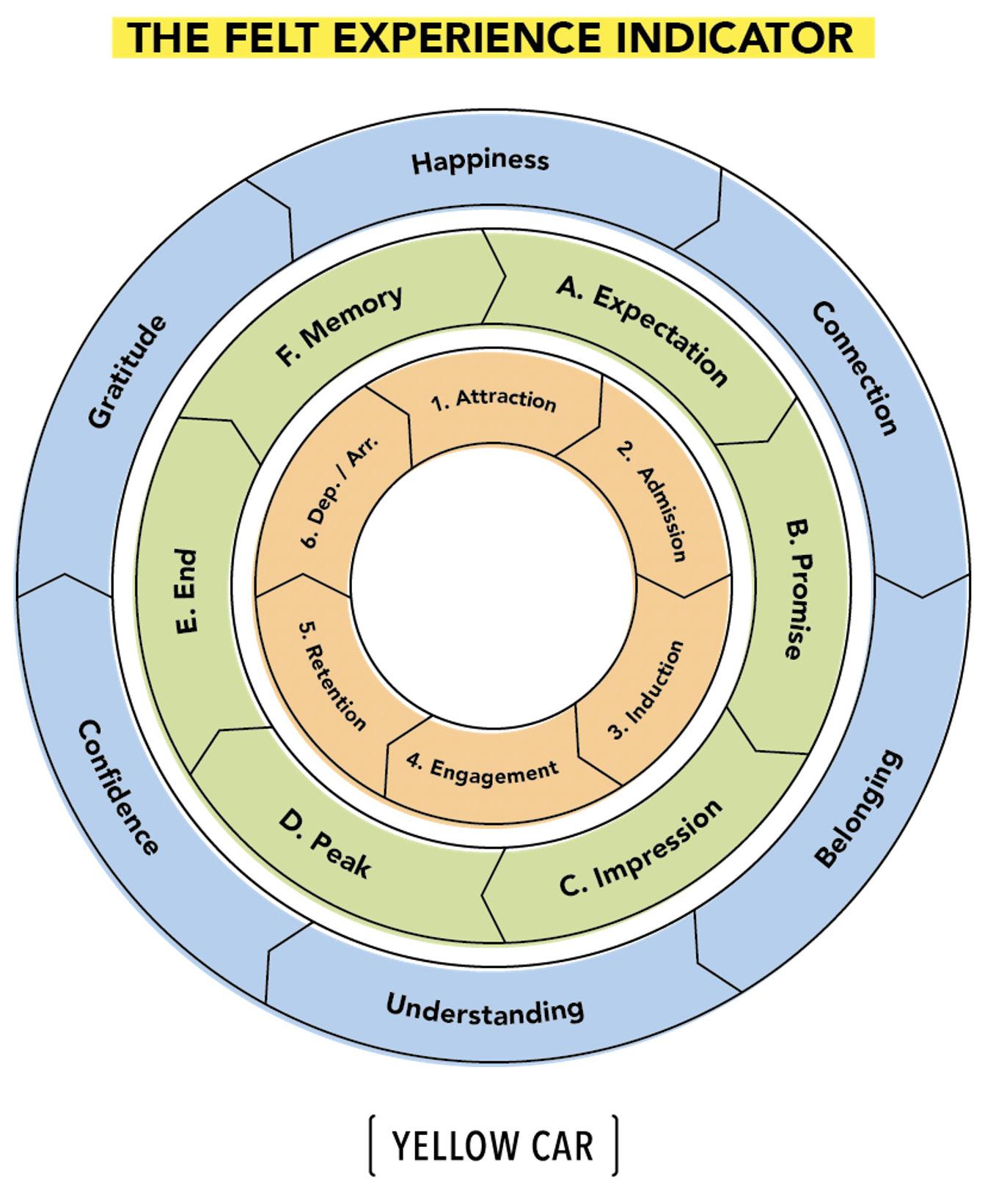

Introducing the Future of Parent Feedback to Schools By David

Willows

International Teachers Teaching: Why We Stay By Aleksa Moss

28

Mindfulness

Let’s Talk: Critical Intellectual Discussion Beyond the Curriculum By Jared Rock

Creating a coherent curriculum with the International Primary Curriculum (IPC)

By Jacqueline Harmer and Andy Freeman

42 ISLES: Strategic Leadership for Inclusive Student Support By Cindy Warner-Dobrowski, Priscilla Leighton, Kristel Solomon-Saleem and Trina Cobbledick

44 Action Research

Kagan Structures to Enhance Oral Mandarin Proficiency: The Impact of Organizing Classroom Talk

By Pham Ngoc Mai Anh

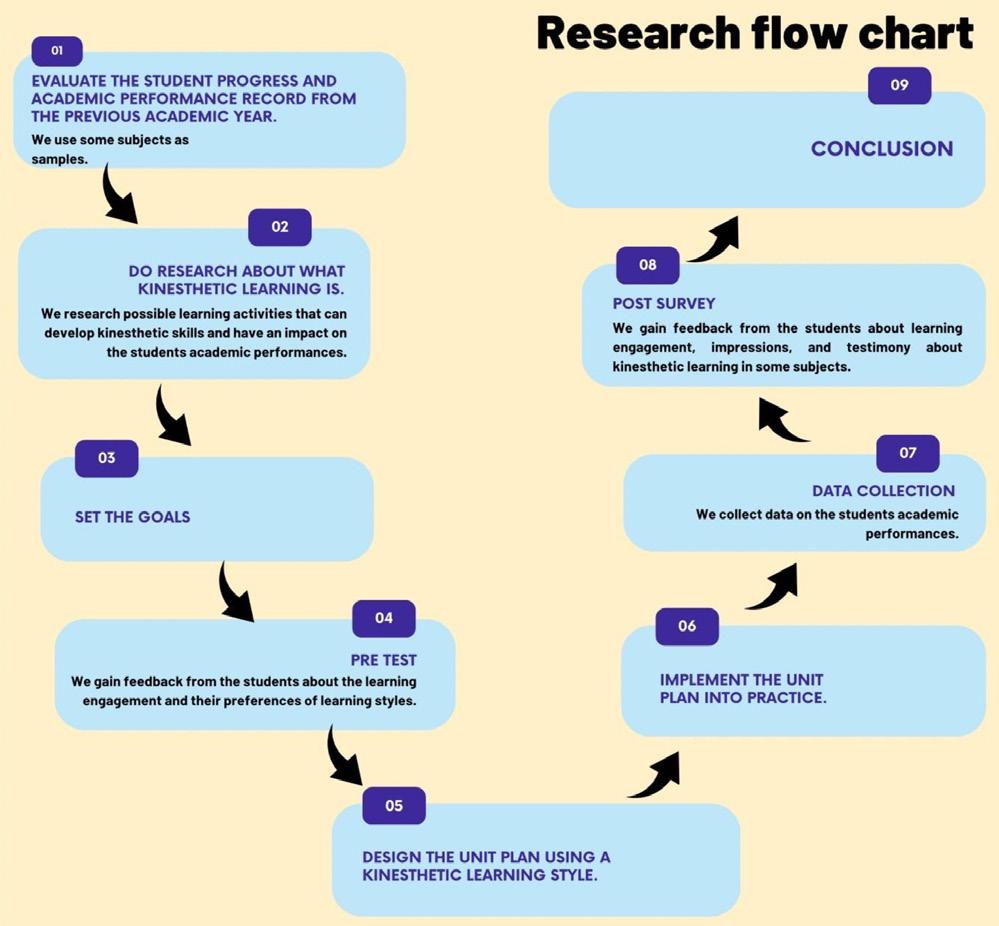

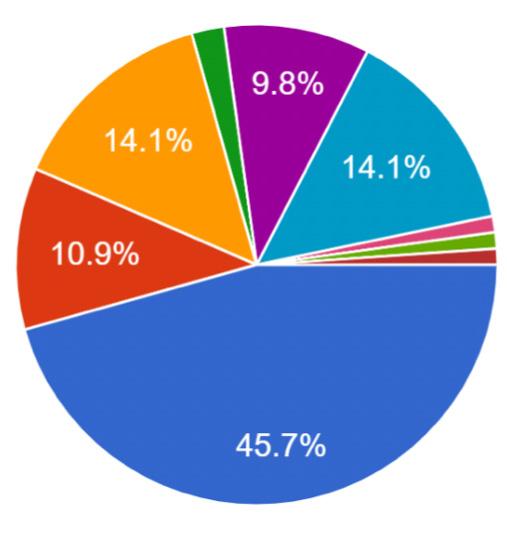

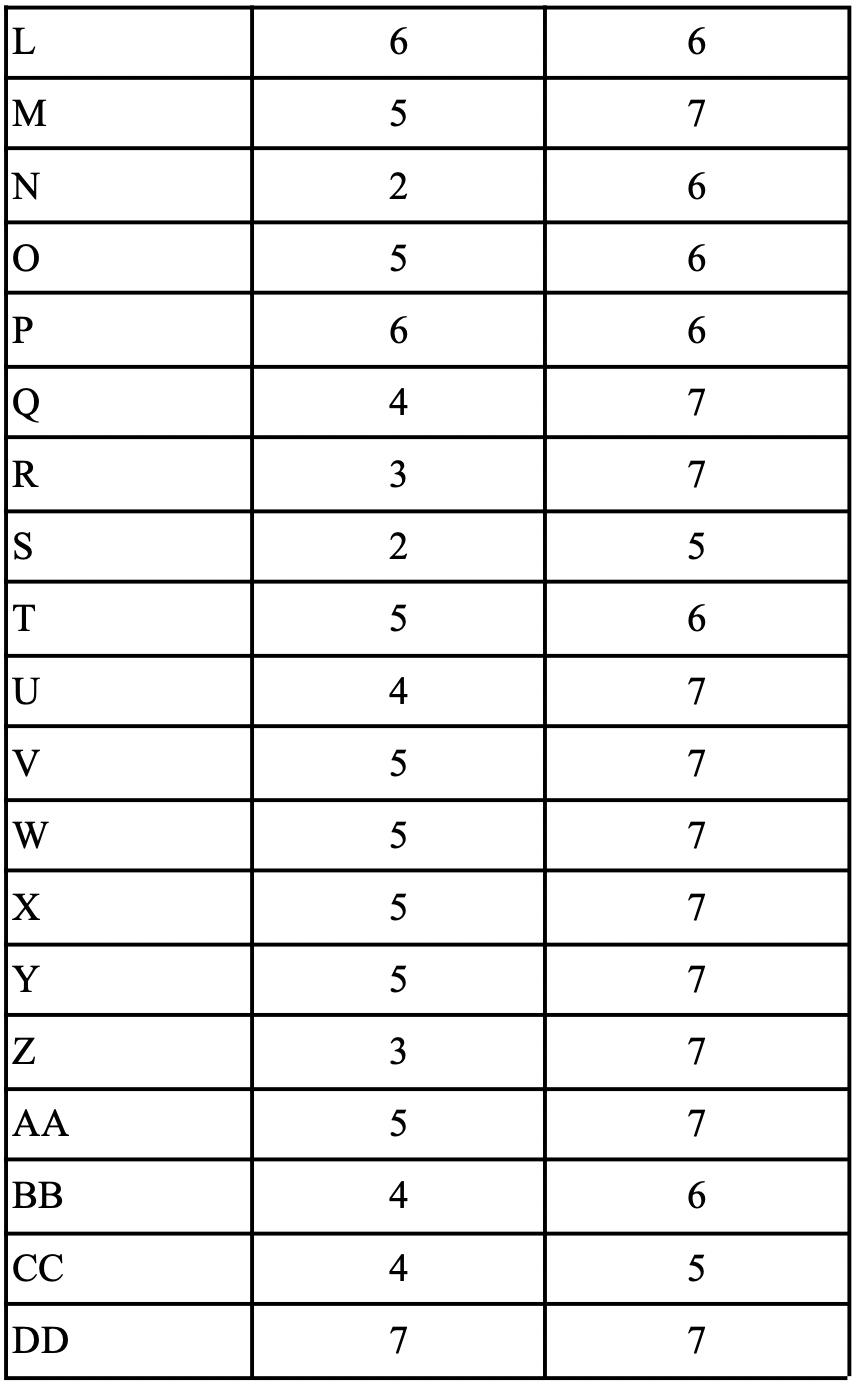

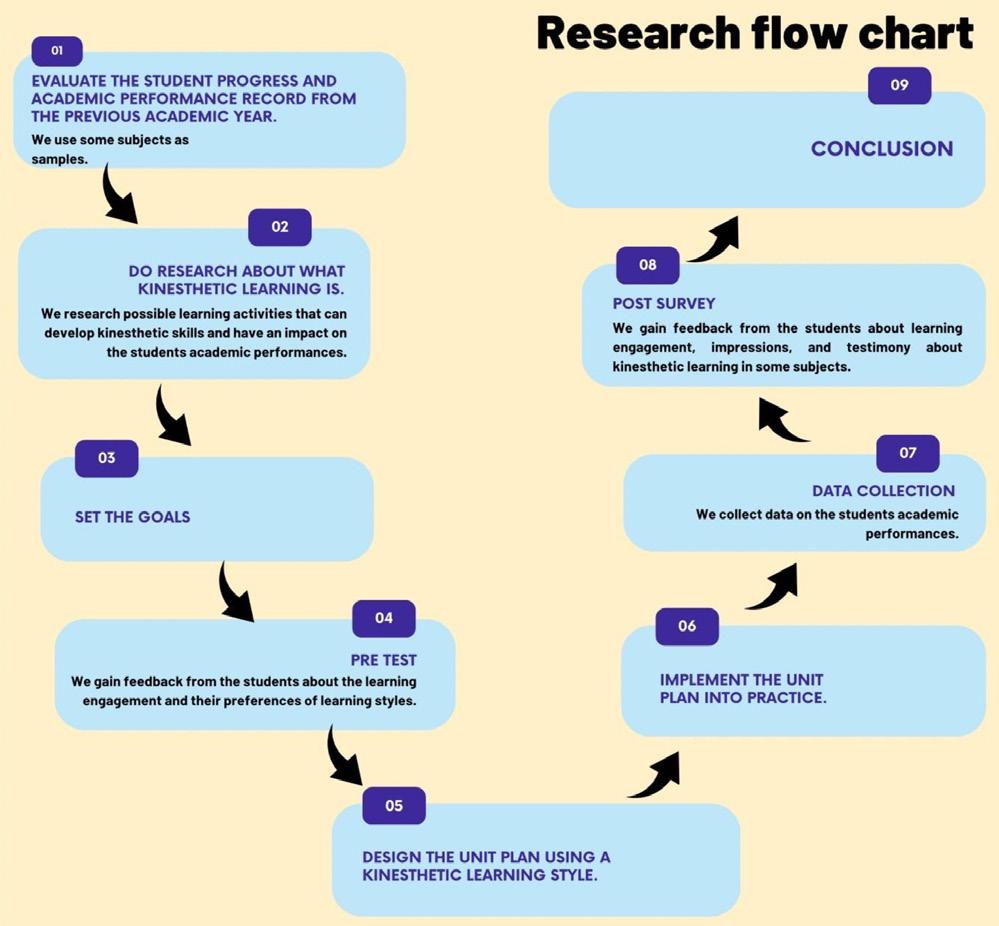

How Does Kinesthetic Skill Acquire More Knowledge?

By Gloria Natalia

The Impact of Differentiated Instruction and UDL on Secondary Students’ Critical Thinking Skills

By Thressye N Nainupu, Kustiani Widyarti & Andre Yulianto

53 Global Citizenship Community Service Grant

Triple A Mission: Empowering Youth to Raise Awareness and Promote Mental Health Initiatives Globally

By Suhani Chawla

The Dolmaa Ling Soup Kitchen (see page 56)

By Bilguunzaya Chuluunbaatar

54 Global Citizenship

A Recipe for Whole School Transformation Towards Active Global Citizenship By LeeAnne Lavender

58 Green & Sustainable

Growing a Green Movement By Paul Escott

60 Press Release

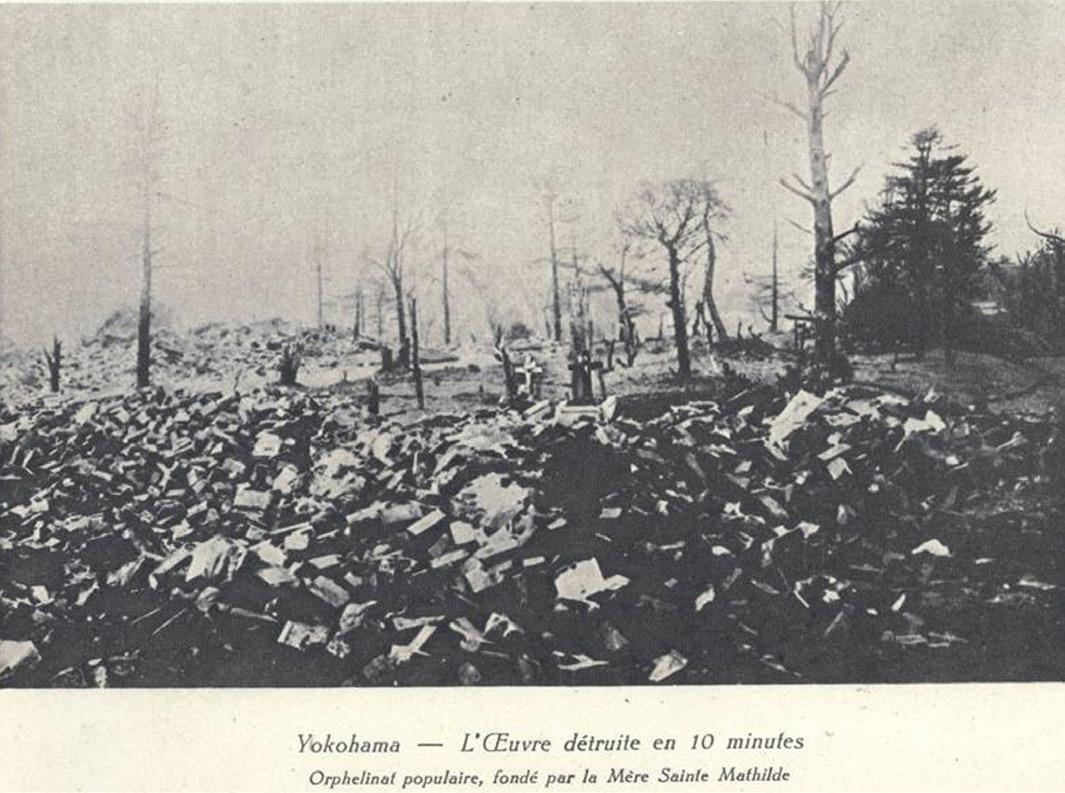

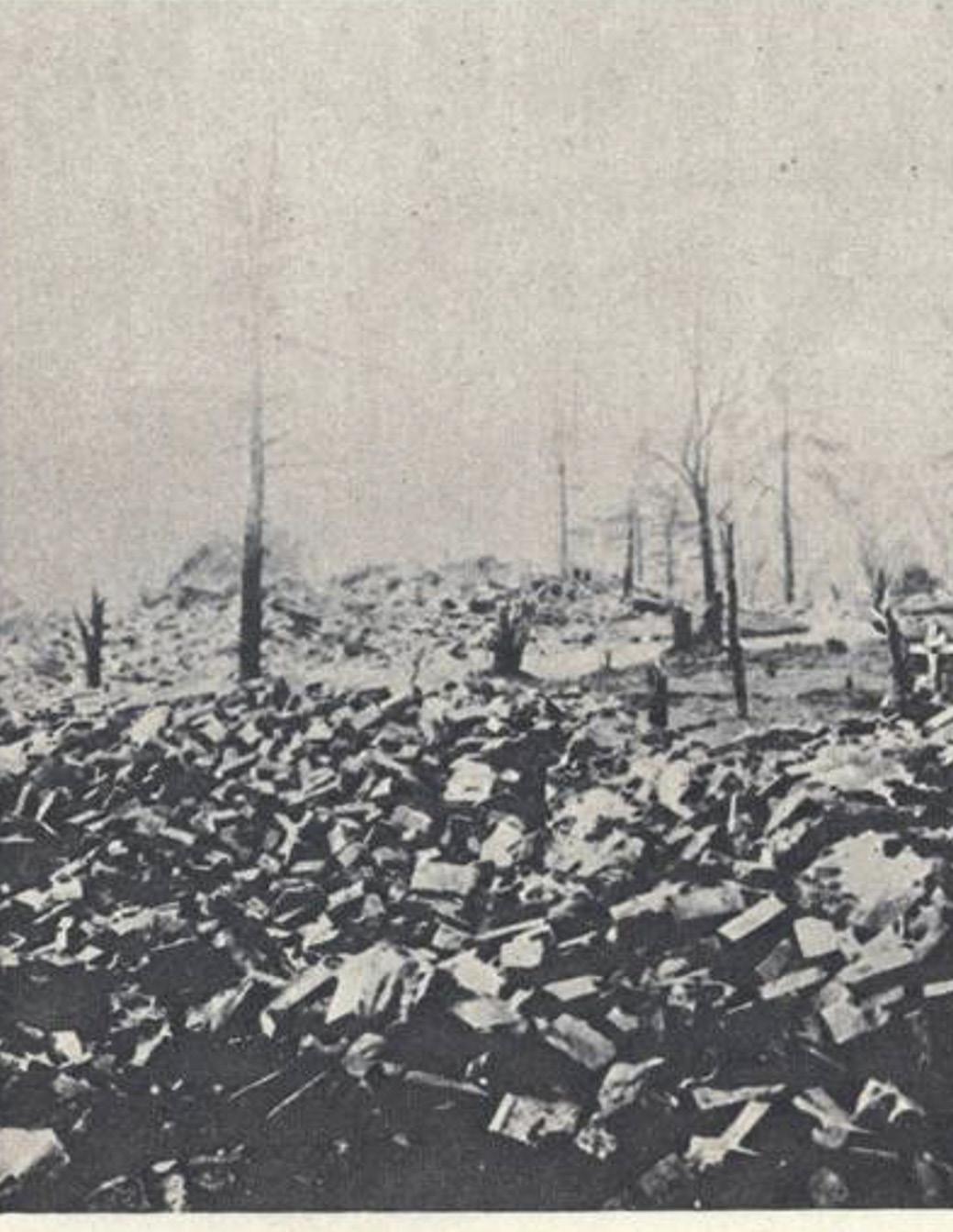

Yokohama International School Facilitates Collaboration and Innovation at JISTG Conference

62 Memoir

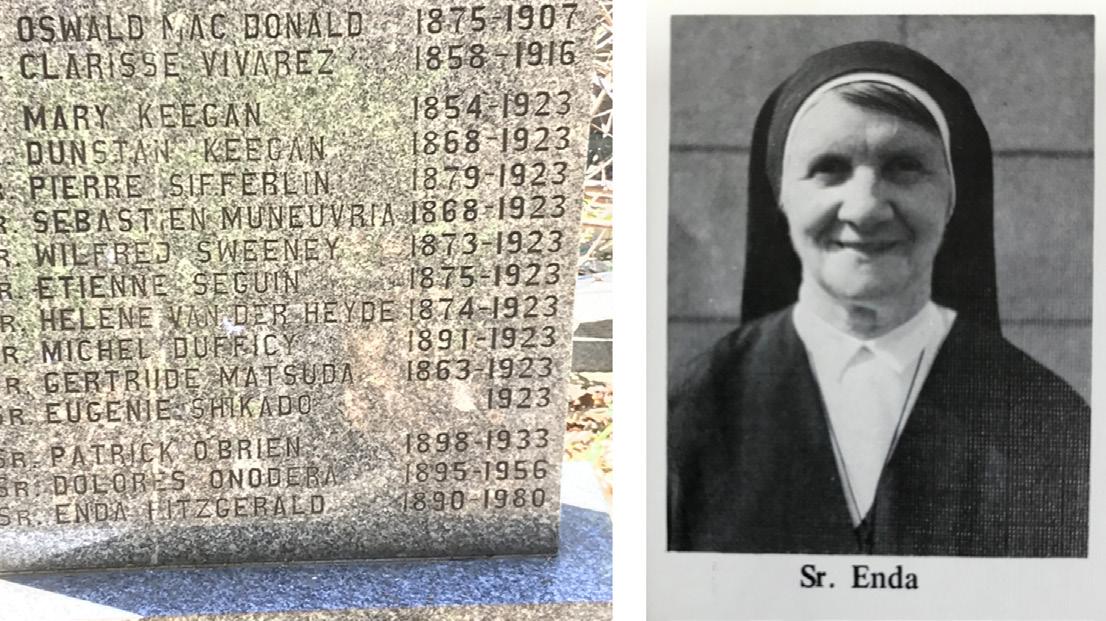

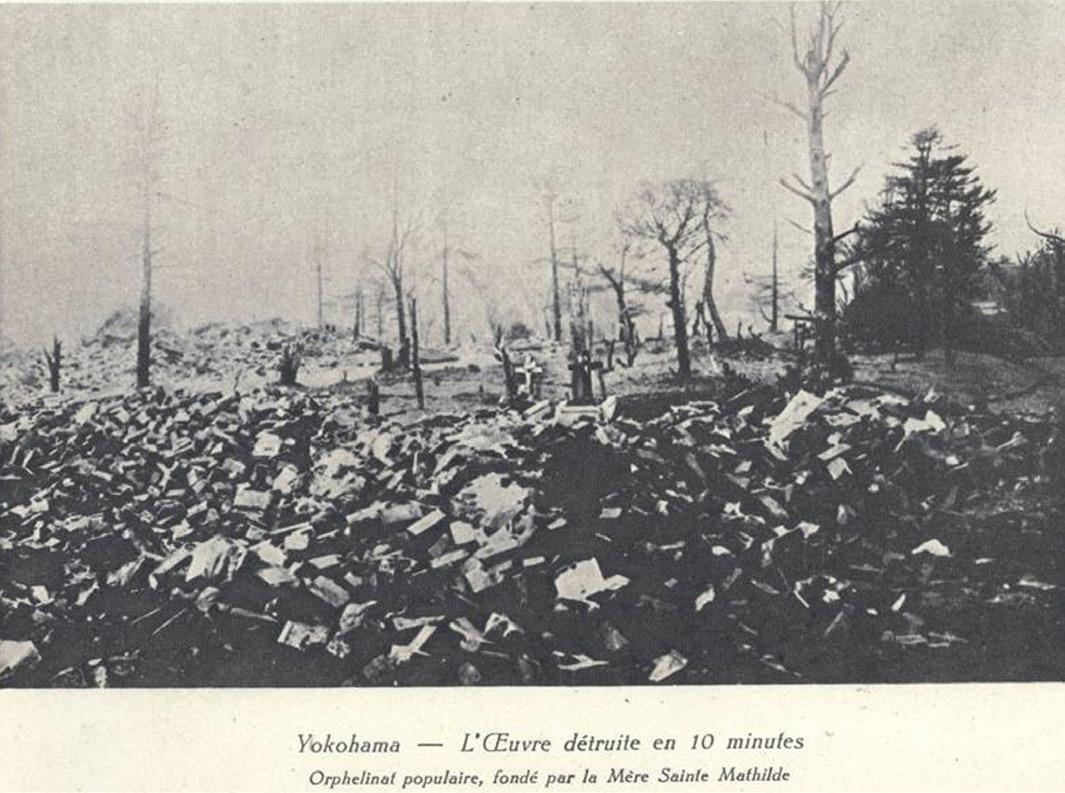

The 100th Year Commemoration of The Great Kanto Earthquake By Jeanette K. Thomas

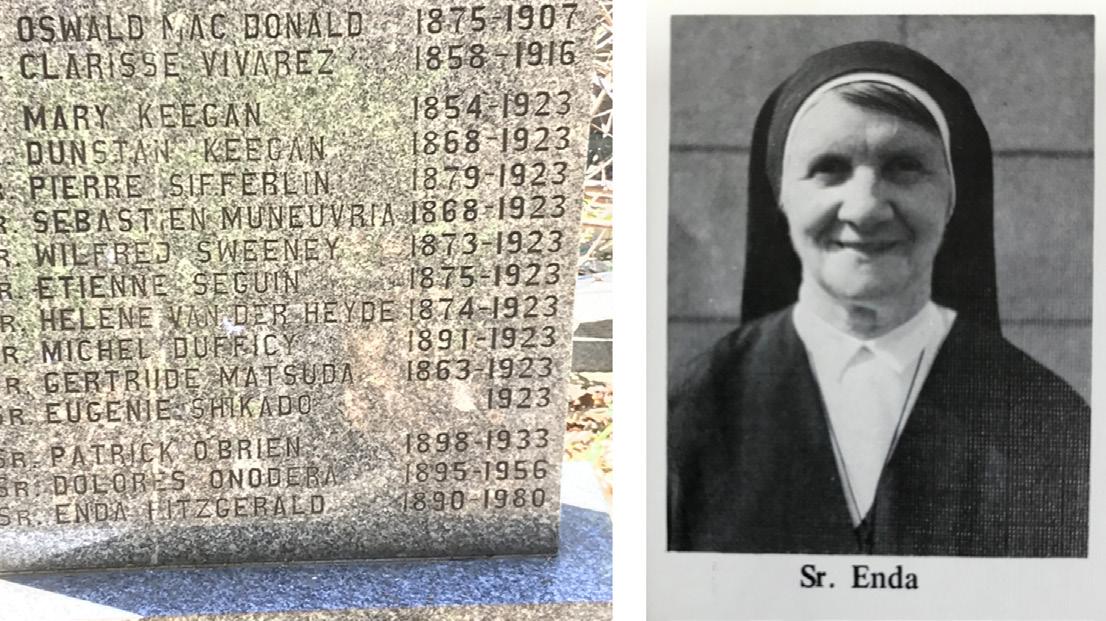

65 Remembering Sr. Maria Zenaida Ancheta

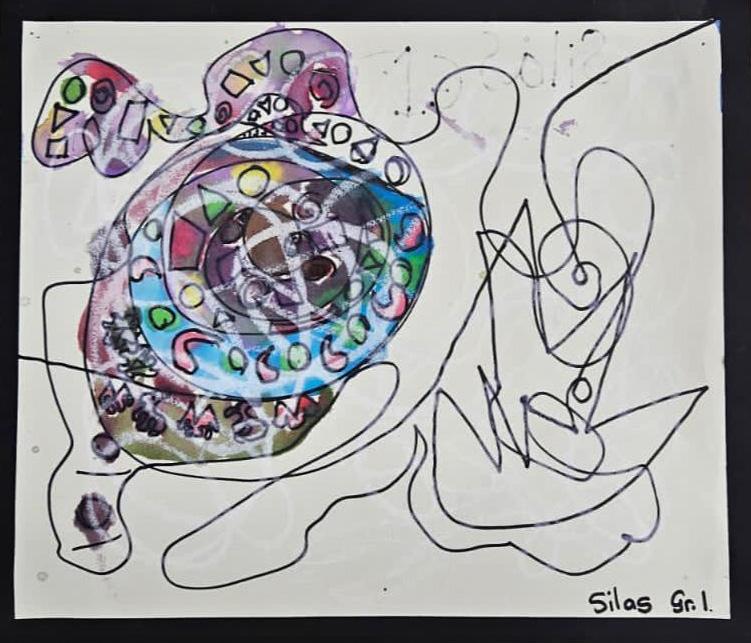

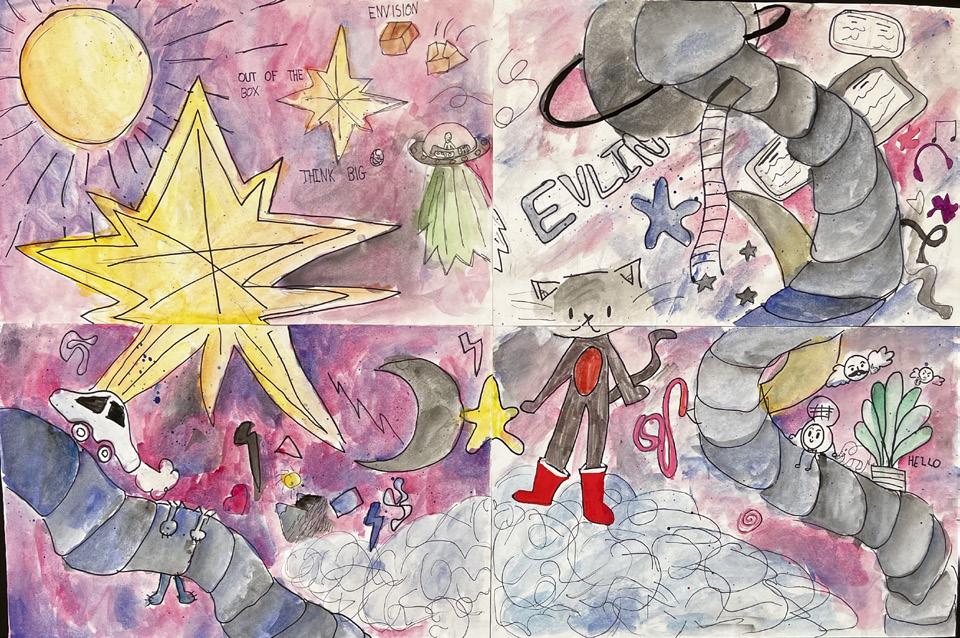

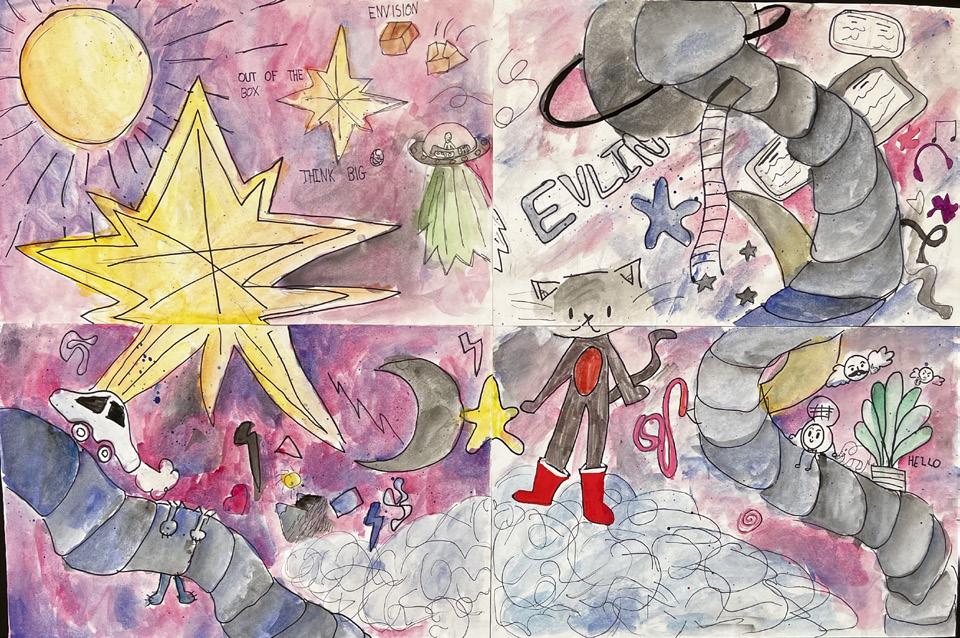

66 Elementary Art Gallery

Fall 2023 Issue 1

2 Welcome Message from the Executive Director 3 What’s in Store for 2023-2024? 4 Welcome New Heads, Principals, Associates, and Individual Members 8 Global Citizenship Awardees & Community Grant Recipients

Service Learning

10

Farming Nagomi By Emi Hisamatsu

Artificial

14

Intelligence

What can you learn about yourself while exploring AI?

26 Teacher Retention

Equity

Warrior

Mindfulness

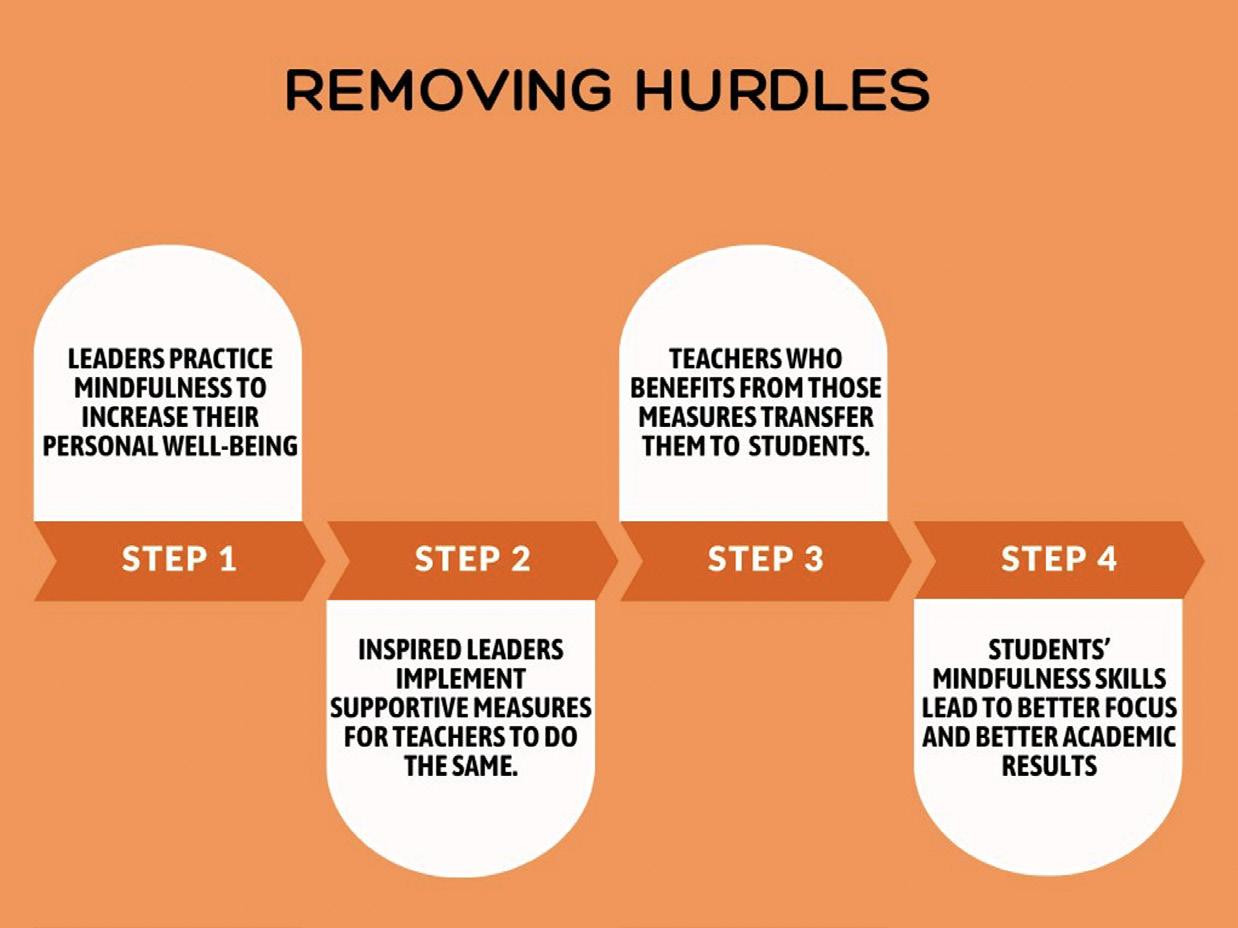

Can I be an equity warrior? By Matthew Militello & Carrie Morris 30

Curriculum

I know it would be good for me, but… By Michel Thibeault 32

Message from the Executive Director

The Tie That Binds

Welcome to the Fall edition of the EARCOS Tri-annual Journal. All of us at EARCOS hope that this finds you and your school communities thriving, happy and well. We also hope that you will find much to enjoy and think about in this issue. We are grateful to the many colleagues who have taken time to share their thinking with us. It underscores, again, what a very dynamic region this is.

As we move into the second full school year of this post-pandemic era, international educators in every region are embracing every opportunity possible to re-connect in person. It is easy to understand why.

During the pandemic we took advantage of technologies that allowed us to meet virtually, but it became obvious that we humans need to be together in real time and real place. Just thirty minutes of the evening news on any day is enough to tell you that the fabric that has (barely) held the world together in our lifetimes is coming undone. Faced with so many threatening developments can there be any question why there is such a powerful need for educators to join together to share our questions, our worries and ideas? How will we provide the young people whose futures are entrusted to us the essential skills, values and the understanding they need to combat the escalating issues of the 21st Century?

Zoe Weil, President of the Institute for Humane Education, may have said it best in her book The World Becomes What We Teach: Educating a Generation of Solutionaries (see humaneeducation.org). Are we preparing a generation that will be able to solve the challenges we are bequeathing to them? In Socratic terms, are our schools empowering young people to value, seek and live a ‘good life’ or are we preparing them for a life in a world that will no longer exist when they get there?

If you agree that educators touch the future, just what kind of future are our children and students being asked to grab on to? Creating a better world for and with our students is the reason so many of us accepted the call to become educators in the first place--and why so many remain deeply committed to education. Touching the future and creating a better world are ideas that resonate. Those ideas can flourish within every classroom today. The changes we can affect in one classroom or in one school year may be minutely incremental, but they are multiplied time and time again each day and reverberate across time and space as more and more educators join hands together to create a better world.

Consider the lasting impact programs like the Global Issues Network, Stories that Move, Inspired Citizens, Roots and Shoots, Facing History and Ourselves and #MyFreedomDay have on students. Consider, too, the power of the service-learning programs in our schools (a number of which are featured in this issue). I must admit to feeling a sense of awe when I talk to people who have created projects like the After the Wave Fund at IS Bangkok and the Leading Young Women initiative at St. Joseph’s International in Singapore and the EJAAD Afghan Project at Osaka International School—and so many other student-driven initiatives that make the world a better place. Programs such as these truly touch the future—and the hearts and minds of everyone associated with them.

The future our students need requires nothing less than a highly principled generation with the deep knowledge, understanding, empathy, will and confidence to act together across boundaries and across and within cultures. Schools may have a jambalaya of mission statements, visions, goals and objectives, but we must agree that the singular calling of touching tomorrow and creating a better world for everyone is, as it has always been, the true heart and soul of all international educators. It is the tie that binds.

We welcome your contributions to this journal and in person on initiatives you and your community are taking to prepare students for the world that hungers for their active citizenship and leadership. Our students, our children--and this fragile world of ours--need and deserve nothing less.

With continued best wishes to you, your students and communities for a happy and healthful school year.

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

2 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Here is our list of sponsored value-packed webinars, filled with International School insights provided by leading edge panelists and subject matter experts. Topics addressed are leadership, governance, assessment, curriculum, and many more.

OCTOBER

Professionally Networking to Enrich Conference Learning

Presented by: Michael Iannini

Wednesday, Oct 11, 2023

4:00 - 4:30 AM HKT

Establishing a Student-Staffed & Managed Learning Center Workshop

Wednesday, Oct 14-15, 2023

VENUE: International School of Tianjin | Tianjin, China

NOVEMBER

Why and When Do Independent School Boards Become Dysfunctional

Presented by: John Littleford

Saturday, November 4, 2023

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

Empowering Core Instruction in Mathematics: Integrating Generative AI and UDL Principles in Lesson Planning

Presented by: Erma Anderson

Saturday, November 7,14, & 21 2023

6:00 PM HKT

Exploring the Cycle of Socialization

Presented by: Margaret Park

Saturday, November 11, 2023

9:00-10:30 AM HKT

Measuring the Experience of Families in Your School

Presented by: David Willows & Suzette Parlevliet

Saturday, November 25, 2023

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

DECEMBER

Decolonization 101: How to Decolonize Your Classroom and Curriculum

Presented by: Dr. Soojin Pate

Saturday, December 2, 2023

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

Strategic Planning: Necessary, often Exciting and sometimes Risky

Presented by: John Littleford

Saturday, December 9, 2023

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

JANUARY

Reading and Evaluating Asian American Youth Literature

Presented by: Sarah Park Dahlen

Saturday - January 20, 2024

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

FEBRUARY

Women in Leadership

Presented by: Nitasha Crishna

Saturday, February 17, 2024

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

MARCH

How to Intentionally Integrate Students’ Languages in Any Class

Presented by: Tan Huynh

Saturday, March 9, 2024

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

APRIL

Identity Centered Learning

Presented by: Daniel Wickner

Saturday, April 13, 2024

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

MAY

Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Learning

Presented by: Joel Llaban

Saturday, May 25, 2024

9:00 - 10:30 AM HKT

For more information please visit https://earcos.org/2023_upcoming_events.php

Fall 2023 Issue 3 WHAT’S IN STORE FOR 2023-2024

Welcome New Schools >>

American International School Vietnam

Australian International School Pte Ltd

Cheongna Dalton School

German European School Singapore

International School of Western Australia

ISHCMC - American Academy

QSI International School of Dili

Ramkhamhaeng Advent International School

Reedley International School

Shattuck-St. Mary’s Forest City International School

The International School of Penang (Uplands)

Thalun International School

The Winstedt School

VERSO International School

Jon Standen, Executive Principal www.aisvietnam.com

Karrie Dietz, Head of School www.ais.com.sg

Jiho Park, Head of School http://daltonschool.kr/

Stefan Pauli, Principal / Schulleiter www.gess.sg

Caroline Brokvam, Principal www.iswa.wa.edu.au/

Nathan Swenson, Head of Campus www.aavn.edu.vn/

Audra Phelps, Director www.dili.qsi.org

Mary Megan Lartey, Head of School www.rais.ac.th

Rene McQuillin, Head of School www.reedleyschool.edu.ph

Gregg Maloberti, Head of School www.ssm-fc.org/

Marc Mesich, Head of School www.uplands.org

Winsome May Saldanha, Director www.thaluninternationalschool.com

Chris Raymaakers, Head of School www.winstedt.edu.sg

Ryan Persaud, Head of School www.verso.ac.th/

Xi’an Liangjiatan International School Dr. Lily Liu, Head of School https://xalis.com/

Welcome

New Heads >>

American International School, Vietnam

Aoba-Japan International School

Bandung Independent School

Berkeley International School

Canadian Int’l School of Hong Kong

Cheongna Dalton School

Dulwich College Suzhou

East-West International School

Ekamai International School

Chandra McGowan

Jake Madden

Marci Russell

Paul Pallister

Tim Kaiser

Jiho Park

David Massiah

Kate O’Connell

Rachaniphorn Ngotngamwong

Gyeonggi Suwon International School Tiffeney Brown

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu

Int’l Christian School-Hong Kong

International School Bangkok

International School Dhaka

International School of Brunei

International School of Dongguan

International School of Kuantan

Int’l School of Nanshan Shenzhen

Charles Chang Chien

Nicholas Seward

Sascha Heckmann

Steve Calland-Scoble

Stephen Kendall-Jones

Mark McCallum

Chin Hui Kee

Addie Loy

International School of the Sacred Heart Anne Wachter

ISHCMC - American Academy

Nathan Swenson

ISS International School Mun-E Chan

KIS International School

Carolyn Mason Parker

Medan Independent School Gregory McGuire

Mont Kiara International School Robert Cody

Osaka YMCA International School Kazuki Yamane

QSI International School of Dili Audra Phelps

Ramkhamhaeng Advent Int’l School Peter Munasinghe

Reedley International School René MacQuillin

Renaissance International School Mark Sayer

Shattuck-St. Mary’s Forest City Gregg Maloberti

International School

Stamford American School Hong Kong Marco Longmore

Stonehill International School Joe Lumsden

Taipei American School Evelyne Estey

The Int’l School of Penang (Uplands) Marc Mesich

The Sultan’s School Nigel Fossey

The Winstedt School Chris Raymaakers

UWC Thailand International School Lural Ramirez

XCL American School of Bangkok Sean O’Maonaigh

XCL World Academy Tammy Murphy

Xi’an Hanova International School Lucas Roberts

Yew Chung International School of Beijing Shelley Swift

Yew Chung Int’l School of Chongqing Jessie Xiao

Yogyakarta Independent School

Welcome New High School Principals >>

American International School of Guangzhou Lori Marek

American International School Vietnam Lee Parker

American Pacific International School Shaun Henriksen

Australian International School Pte Ltd Adam Patterson

Beijing City International School Natalie Harvey

Brent International School Manila Brett Petrillo

Elia Nugraha Ekanindita

Brent International School Subic Todd Wyks

Canadian Academy Brian Combes

Canadian Int’l School of Hong Kong David Butler

Canggu Community School Rick Odum

Cebu International School Benjamin Martin

Cheongna Dalton School Marisa Montelibano

4 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Christian Academy in Japan Tyrone Fambro

Dalat International School Scott Uzzle

Ekamai International School

Armin Kritzinger

European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City John Horsington

Fukuoka International School Ken Forde

Global Jaya School Howard Menand

Grace International School Anne Spohnhauer

Hong Kong International School

Aimmie Keller

Hsinchu International School Timothy Hicks

International Christian School - HK Tom Penland

International School of Beijing

Will Paananen

International School of Kuantan Kee Chin Hui

ISHCMC - American Academy

Jakarta Intercultural School

Jenn Pratt

Edward Wexler

Korea International School Christina Powers

Nagoya International School

Lisa Michelle Nnadozie

Nanjing International School Sara Morrow

Northbridge Int’l School Cambodia Sarah Newton

Punahou School

Gustavo Carrera

Raffles American School Mark Hemphill

Reedley International School Jerome Fernando Castro

Renaissance International School Andy Roberts

Ruamrudee International Sc-hool Nathan Meisner

Shanghai Community Int’l School Ken Kitchens

Shanghai Qibao Dwight High School Robbie Shields

Shattuck-St. Mary’s Forest City Int’l School Lianne Dominguez

Shen Wai International School Aloha Lavina

Springboard Int’l Bilingual School Mark Munro

St. Mary’s International School Kimberly Fradale

St. Paul American School Hanoi TJ Shiers

Stonehill International School Manpreet Kaur

Suzhou Singapore International School Patrick Phillips

Taipei American School Becky Read

The Int’l School of Penang (Uplands) Emily Vallance

The International School Yangon Mike Simpson

The Sultan’s School

The Winstedt School

THINK Global School

Lori Carpenter

Tara Beck

Andy Jenkinson

Tianjin International School Jacob Way

United World College of South East Asia Seema Desai (Dover)

Xi’an Liangjiatan International School Jaimala Quinlan

Yew Chung Int’l School of Beijing Tanya Nizam

YK Pao School James Lyng

Welcome New Middle School Principals >>

Australian International School Pte Ltd

J Dianne Brederson

Beijing City International School Natalie Harvey

Canadian Academy

Canadian Int’l School Bangalore

Canadian Int’l School of Hong Kong

Cebu International School

Chiang Mai International School

Christian Academy in Japan

Ekamai International School

European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City

Fukuoka International School

Grace International School

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu

International School of Kuantan

International School of Myanmar

Keystone Academy

Brian Combes

Andrew Nicholson

Ange Molony

Benjamin Martin

Troy Regis

Renee Van Druff

Christy Perera

John Horsington

Ken Forde

Cindy Morphis

Pingchun Wu

Kee Chin Hui

Mark Weber

Houming Jiang

Welcome

Korea International School Molly Burger

Nagoya International School Lisa Michelle Nnadozie

Nanjing International School Sara Morrow

Nishimachi International School Craig Cantlie

Reedley International School Maria Andrea De Guzman

Renaissance International School Andy Roberts

Ruamrudee International School Dr. Nathan Meisner

Shanghai American School Erica Curry

Shattuck-St. Mary’s Forest City Int’l School Lianne Dominguez

Shen Wai International School Aloha Lavina

Springboard Int’l Bilingual School Mark Munro

The Int’l School of Penang (Uplands) Emily Vallance

The International School Yangon Mike simpson

The Winstedt School Alastair Dawson

Xi’an Liangjiatan International School Jaimala Quinlan

New Elementary School Principals >>

American Int’l School of Guangzhou Virginia Udall

American Pacific International School Stephanie Dracz

Ascot International School

Australian International School Pte Ltd

Branksome Hall Asia

Canadian Int’l School of Singapore

Cebu International School

Cheongna Dalton School

Concordia Int’l School Shanghai

Daegu International School

Nicola Holloway

Emma McAulay

Peter Row

Andrew Marshall

Maureen Juanson

David Hill

Angela Beach

Steve Vis

Dalat International School Lizzy Neiger

Dalian American International School David Jones

Dwight School Seoul Serena Geddes Aguilar

Fukuoka International School Ken Forde

German European School Singapore Kristyn Holland

Gyeonggi Suwon International School Jeannie Sung

Hong Kong International School Duncan FitzGerald

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Erica Ro

International School of Kuantan Kee Chin Hui

Int’l School of Nanshan Shenzhen Thomas Tucker

International School of Tianjin Cameron Wallace

Keystone Academy Beryl Nicholson

Fall 2023 Issue 5

Welcome

New Elementary School Principals >>

Korea International School Taryn Pereira

Nagoya International School Holly Johnson

Nishimachi International School Craig Cantlie

Northbridge Int’l School Cambodia Aidan Stallwood

Oberoi International School Gunilla Bengtsson

Raffles American School Suzanne Thibault

Reedley International School Maria Andrea De Guzman

Seisen International School Serrin Smyth

Shanghai Community Int’l School Molly Myers

Shattuck-St. Mary’s Forest City Int’l School Lynne Morrin

Springboard Int’l Bilingual School Sandra Lopez

St. Mary’s International School Barry Ratzliff

Welcome

St. Paul American School Hanoi Myong ‘Moo’ Eiselstein

Stamford American School Hong Kong Rae Lang

Stonehill International School Peter Spratling

Thalun International School MazenR.DGuzman

The Int’l School of Penang (Uplands) Jacqueline North

The Sultan’s School Robin Cummings

The Winstedt School Sonia Pathela

Xi’an Hanova International School Sandy Venter

Xi’an Liangjiatan International School Marly Song

Yew Chung Int’l School of Beijing Geoffery Ross

Yew Chung Int’l School of Chongqing Graham Mayes

YK Pao School Rosalie Pietsch

Early Childhood Principals >>

Access International Academy Ningbo Charity Yi

Australian International School Pte Ltd

Eromie Dassanayake

Beijing City International School Jackie Becher

Canadian International School of Singapore Angela Spiers

Concordia International School Shanghai Robert Cantwell

Daegu International School Steve Vis

Ekamai International School Hazel Ilao

Hangzhou International School Lynn Pendleton

International School Bangkok Honey Tondre

International School of Dongguan Fiona Teh

Welcome

Int’l School of Nanshan Shenzhen Michael Lattimore

NIST International School Lauren Hateley-Crowe

Reedley International School Maria Andrea De Guzman

St. Johnsbury Academy Jeju Carla Chavez

Thalun International School Theingi Aung

The Int’l School of Penang (Uplands) Jacqueline North

The Winstedt School

Karina Estiningdiyah

UWC Thailand International School Kurtis Peterson

Vientiane International School Regina Alcorn

Yongsan International School of Seoul Susannah Wilcox

New Individual Members >>

Ericson Perez, Head of School

The Vanguard Academy

Lady Bernadette (Didi) Dolandolan, School Director Canadian American School

Johnny Mendola, CEO University Curriclum for Independent Learning

Kaanwarin Polanunt, School Director

Satit Pattana School

6 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Welcome

New Associate Institutions >>

Adobe Systems

Adobe Software for Education

Anatomage

Educational and Medical Technology

Avvanz Pte Ltd

1. Individual Background Checks including Education, Employment, Criminal, Civil, Financial, ID, Social Media covering 150+ countries

2. Company Due Diligence (When appointing Vendors or Contractors)

3. Customized elearning solutions development”

Clipboard Information Technology

EduChange, Inc.

Interdisciplinary Secondary Science Curriculum & Professional Development, Competency-based Assessment, STE(A)M, Disciplinary Literacy Methods

ELi Publishing

K12 Foreign Languages (ELT, LOTE) publisher and content supplier

Intellischool

Educational data analytics, data ops and identity management

Millie Group LTD

Careers & University Guidance for international schools

Onboard 360

Onboarding coaching, consulting, and applications

RED DRAGON BUSINESS CONSULTING

Online Teacher Training Courses at University

Toddle Education Technology

The FUTURE of

SCIENCE LEARNING

Our professionally designed curriculum ensures vertical coherence and elevates rigor without anxiety.

Multi-year models begin as early as Grade 8/Age 13.

Connects the personal, local & global (#TeachSDGs)

Prepares students for advanced exam-based courses

Customized for schools, modifiable by teachers & students

Robust English literacy, engineering, laboratory & data work

Coaching by experienced Intl School science teachers

Fall 2023 Issue 7

EARCOS

the

for

webinar.

info@educhange.com

is an

affiliate member. Start

conversation now

a 2024-25 launch! Schedule a 30-minute

+1-310-736-1300 https://educhange.com/intsciwhat

Has Arrived... and it’s INTEGRATED

Global Citizenship Awardees >>

List of Global Citizenship Award 2023Winners

This award is presented to a student who embraces the qualities of a global citizen. This student is a proud representative of his/her nation while respectful of the diversity of other nations, has an open mind, is well informed, aware and empathetic, concerned and caring for others encouraging a sense of community, and strongly committed to engagement and action to make the world a better place. Finally, this student is able to interact and communicate effectively with people from all walks of life while having a sense of collective responsibility for all who inhabit the globe.

Access International Academy Ningbo Kaiyun Zhang

American Int’l School Hong Kong Hiromichi Sasaki

American Int’l School of Guangzhou Mika Goldman Shayman

American International School, Vietnam Phuong (Hannah) Nguyen

American School Hong Kong Edric Nazareno

American School in Taichung Dalin Daniel Guh

Ayeyarwaddy International School Ye Htut Win

Bali Island School

Caspia Nadapdap

Bandung Independent School Hayun Lim

Bangkok Patana School Ansh Narula

Beijing City International School Sijia (Sophia) Hou

Brent International School Baguio Angeli Eirene Balagot

Brent International School Manila Chaewoo Lee

Brent International School Subic Jihwan An

British School Manila Mikaela Lim

Busan Foreign School Grace Bo Kyung Chun

Canadian Academy Eva Isabel Bonnier

Canadian Int’l School of Singapore Imma Tao Martinez Leger

Canadian International School, Tokyo Shao-Han Veronica Huang

Cebu International School Liam Cergneux

Chadwick International School Yun-Chen (Jin) Wu

Chatsworth International School Trinh Trong Nguyen

Christian Academy in Japan Sunwoo Park

Concordia International School Hanoi Van Anh Nguyen

Concordia Int’l School Shanghai Diya Prashantham

Concordian International School Pei-ying (Melody) Chuang

Daegu International School

Dylan Wang

Dalat International School Caleb Jun

Dalian American International School Samuel Liu

Dominican International School Rachel Junseo Park

Dwight School Seoul Hansung Kim

European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City Hwajun Song

Garden Int’l School Kuala Lumpur Bryan Lim

German European School Singapore Linda Jaschik

Hangzhou International School Sera Bajaj

Hanoi International School Minseo Kang

IGB International School Thesya Thiruchelvam

International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Shiue-Lang Chin

Int’l Christian School - Hong Kong Clement Chin Cheung Chan

Int’l Christian School - Pyeongtaek HaYeon Lee

International School Bangkok Ayaka Bijl

International School Dhaka Marcelle Karina Lamarche Valenzuela

Int’l School Eastern Seaboard (ISE) Taejun Park

International School Manila Reyn Bungabong

International School of Beijing Alexander Domingo

International School of Busan Charlene Kim

International School of Dongguan Pao-Chia Hsu

Int’l School of Nanshan Shenzhen Gordon Nie

International School of Phnom Penh Bisruti Pandey

International School of Ulaanbaatar Bilguunzaya Chuluunbaatar

International School Suva Joy Clark

Kaohsiung American School Wilson Yu

Keerapat International School Thiranat Elaine Kittikhunkhongkha

KIS International School Franciszek Maurer

Korea International School-JeJu Campus Hajin Ruy

Lanna International School Thailand Aran Tantinipankul

Marist Brothers International School Rina Okazaki

Medan Independent School Sara Henao

Mont’Kiara International School Zeynep Cetingul

Nagoya International School Judy Joo

Nanjing International School Sofia Brevigliero

Nansha College Preparatory Academy Ray Kairui Ou

NIST International School Zenia Mistry

Osaka International School Ayami Nozaki

Osaka YMCA International School Anju Manfred

Prem Tinsulanonda International School Sonam Choki Lhamo

Ruamrudee International School Thitilapa (Ivy) Sae-Heng

Saint Maur International School Yura Kitamura

Seisen International School Mika Kato

Sekolah Ciputra Cheryl Loemantoro

Seoul Foreign School Isabella Jia Dunsby

Seoul International School John Kim

Shanghai American School-Pudong Campus Vivian Chou

Shanghai American School-Puxi Campus Connor Tai-Chi Chen

Shanghai Community Int’l School - Ying-Shan Pinkgua Mao Hongqiao Campus

Shanghai Community Int’l School - Federico Cordischi

Pudong Campus

Shen Wai International School Hanqi (Angel) Wang

Shenzhen College of Int’l Education Xiwen Liang

Shenzhen Shekou International School Athena Zhiyi Wang

Singapore American School Gio Park

Singapore Int’l School of Bangkok Panthira Polcharoen

St. Johnsbury Academy - Jeju Aman Shajee

St. Joseph’s Institution International Angelica Claudia

8 EARCOS Triannual Journal

St. Marys International School

St. Paul American School Hanoi

Kevin Oh

Khuat Minh Hoi Tran

Surabaya Intercultural School Ji Woo Chae

Taejon Christian International School Mu Jun Kim

TEDA Global Academy Lin Ting-Wei

Thai-Chinese International School Annie Natganthima Hsu

Thalun International School

The American School in Japan

Wai Yan Win Aung

Sena Chang

The British School New Delhi Arnav Gupta

The Int’l School of Kuala Lumpur Pulkit Chaudhari

The International School Yangon Hmwe Hmwe Aung

Tianjin International School

SoHee Choi

Tohoku International School Yu Iwamoto

United Nations Int’l School of Hanoi Tanuska Bora

United World College of South East Asia

Jaeim (Jamie) Paik East Campus

Utahloy Int’l School Guangzhou Ayako (Catherine) Nozue

UWC Thailand International School

Ornkanya Kaengkan

Victoria Shanghai Academy Shi Yao (Anna) WEI

Vientiane International School

Thanakrit Nolintha

Western Academy of Beijing Hannah Garabito-Silva

Western Int’l School of Shanghai Thomas Liu

Wuhan Yangtze International School Luke Paul deMena

XCL World Academy Boon Xuan Cheah

Xiamen International School Min Sung Kim

Yangon International School

Thant Thawdar Thwin

Yantai Huasheng International School Jungwon Moon

Yew Chung International School of Shanghai Yilun Allen Li

Yongsan International School of Seoul Kyra Yeun Jun

Global Citizenship Community Grant Recipients >>

All of us here at EARCOS wish to extend our sincere congratulations to the following Global Citizens who have been chosen to receive an EARCOS Global Citizen Community Service Grant of $500 to further their excellent community work during this upcoming academic year. The recipients are:

NAME

Reyn Bungabong

Bilguunzaya Chuluunbaatar

SCHOOL

International School Manila

International School of Ulaanbaatar

Angelica Claudia St. Joseph’s Institution International

Sena Chang

Phuong (Hannah) Nguyen

Suhani Chawla

The American School in Japan

PROJECT NAME

The Wagon School

The Dolmaa Ling Soup Kitchen

Aku Bisa (‘I can’ in Indonesian)

ASIJ Sustainability Steering Committee

American International School, Vietnam Service Pals

Shanghai Community International School - The Triple A Hongqiao Campus

Fall 2023 Issue 9

SERVICE LEARNING Farming Nagomi

By Emi Hisamatsu Aoba Japan International School

By Emi Hisamatsu Aoba Japan International School

For centuries, the Japanese have been defining the meaning of life through the concept of nagomi which refers to being in a state of “balance, harmony and wellbeing in the mind and in the physical body” (Dickinson, 2023). Empathy is integral in achieving a balance in a world where mental health is on the decline and where people can easily become focused on their own needs while forgetting the needs of others (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2021). Jamil Zaki, a Stanford University psychologist, defines empathy as “the ability to share and understand one another’s feelings— a psychological “superglue” that connects people and undergirds cooperation and kindness” (Zaki, 2019). In most International Baccalaureate (IB) schools, empathy forms the foundation for many of its underpinnings. There is a drive to foster international-mindedness, encourage servicing the community, as well as to take part in inquiry-based learning where empathy can assist in considering different perspectives. I believe that we can find nagomi through turning our attention to the natural world surrounding us and through starting from the basics of growing our own food. In a complex world, where it may seem difficult to find the right path, the simple initiative of farming can teach us the values of patience, hard work, compassion, and respect for our local community.

To gain a deeper understanding of empathy, we need to delve into how it is separated into three distinct categories: cognitive, emotional and compassionate empathy (Miller, 2022). Cognitive empathy is being able to understand someone else’s thinking and feelings, emotional

empathy is being able to feel someone else’s joy or pain, and compassionate empathy is being able to provide support to another person. Although it is hard to make generational comparisons with regards to the level of empathy that individuals hold or express, some researchers have tried to look at the relationship between the change in our society and our self-perception of empathy. A study led by a group of researchers at the University of Michigan found that, among American college students, the level of empathy has declined from the 1980’s to the 21st century (Konrath et al., 2010). To address the reason for the decline, the authors mention a few possibilities: increase in expectations for success, changing parental styles, rising importance of personal technology and social media use, as well as a rising emphasis on the self instead of others. On the other hand, the fact that empathy among people can decline is indicative of the fact that empathy is fluid and can change over time. From this, we gain hope in understanding that our surroundings and everyday experiences can influence our motives and inclinations for taking action.

In the field of education, teachers are in a good place to model empathy to students, be it through teaching perspectives, communicating empathetically, or listening actively. IB Service as Action (SA) in the Middle Years Programme (MYP) focuses on compassionate empathy that is student-driven, in the form of actions that are taken to address the needs of a community. When living in a metropolitan city like Tokyo, and coming from an affluent background, some students find that issues within the community may not be very conspicuous. A recent study used brain scans to demonstrate that adolescents have lower cognitive and emotional empathic abilities compared to adults (Kim et al., 2020). When adolescents can relate to another person’s experience, then they are more likely to feel empathy towards that person. So as a child, initiating community service may sound like a chore or a daunting task at hand. But once they understand how others live, they are better able to put their own challenges in perspective.

While teaching middle school science in 2019 at Aoba Japan International School (A-JIS), I was lucky to have met Jon Walsh, a Tokyobased urban farming and sustainability consultant, who inspired me into starting a student-led farming project on school campus. The first farm project launched in the fall season of that year, where a cohort of Grade 7 students used available spaces around the campus to grow simple foods such as leafy greens, herbs, tomatoes and peppers. To align with the concepts of sustainability, animal ethics, and health, the first rule of thumb was to grow food without the use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. Most students came with limited experience in growing food, but something about the energy that emanates from nature rekindled their curiosity. Those who feared insects and soil animals slowly changed their perspectives through observing the power of nature in turning a seed into a flourishing plant. The nature of the language being used to address the living creatures changed from that of disgust to that of respect. In taking care of the farm, students were assigned roles and responsibilities for care and maintenance and also learned about composting for the health of the soil. The level of commitment in taking care of the farm really varied by student, but the common attribute was that everyone cooperated and worked as a team.

Farming is all about establishing a balanced relationship with the land and the wild animals, which allows for the personality of the plants to be expressed (Pywell et al., 2015). Every season turns out to be a different experience, with some being better than others due to unforeseen circumstances like typhoons, insect attacks and extreme

10 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Students working on the back garden and transplanting seedlings.

heat. During good seasons, students were able to donate up to 6 shopping-bags’ worth of vegetables to Tokyo’s largest food bank, Second Harvest. Forming a connection with the local food bank was great because not only did students gain a deeper understanding of the poverty and homelessness situation in Japan, but the possibilities for compassionate empathy opened up through being able to share food with others and to volunteer at their food donation kitchens for meal distributions. In addition to making use of the produce for donations, the staff at Cezar’s Kitchen (the catering service at AJIS), often collaborates with our student farmers to utilize the vegetables for school lunch as well as for cooking demonstrations. In the process of taking something from the farm to the table, there is laughter, pride, compassion, connection to the Earth, as well as a sense of community. Being involved in the farming project has provided an opportunity for the students to empathize with the people in their community, with the other species in nature, and to feel harmony through a healthy ecosystem being created right in front of them.

Over the past 3 years, the Covid-19 pandemic has no doubt taken a huge toll on school children around the world. A European study saw signs of an increase in mental health problems and decrease in quality of life among children and adolescents in the year 2021 (Barbieri et.al, 2022). In many cultures around the world, the discussion around mental health is often stigmatized and this can lead to an environment that challenges the seeking of nagomi (Thornicroft, 2006). In 1982, the Japanese coined the term Shinrin-Yoku, which refers to a holistic approach of healing through immersion in nature. Shinrin Yoku is also referenced as Forest Bathing, and in a recent meta-analysis, has been shown to improve mental health in the short term, particularly by reducing anxiety (Kotera et al., 2020). The act of nature walking and growing food have homogeneous elements and bring about the benefits of instilling a sense of mindfulness and a deeper appreciation for nature. A recent study by the University of Colorado found that those who started taking part in community gardening ate more fiber, engaged in more physical activity, and saw a decrease in stress and anxiety levels (Litt et al., 2023). This can be a good encouragement for schools to start implementing programs to get children outside more often. There are challenges to objectively knowing the extent to which someone is in a calm state, free from stress and anxiety, partly due to both internal and external factors being at play. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that regardless of age, allowing children to engage in farming can be a valuable experience in enhancing their overall wellbeing.

As educators, we have the responsibility of modeling core values such as inclusion and respect, and to ensure that students are supported as best as they can in order to achieve a level of balance in their academic and social lives. Farming can bring us back to reality, make us feel grounded, and help us realize our most important capability, which is to let empathy guide our decisions and actions. While schools around the world strive towards incorporating inclusion and wellbeing in their educational systems, they should not underestimate the power of farming programs, whether it is on-campus or renting out a community garden, for the abundance of skills and values that the experience can bring to the students. Farming is not just about growing food with others, but it is also about giving the students the agency to make healthy and informed decisions to serve themselves, their communities and the planet.

About the Author

Emi Hisamatsu works at Aoba Japan International School as an MYP

Math teacher, Science teacher and Grade 7 Homeroom teacher. She can be contacted at emi.hisamatsu@aobajapan.jp

References

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. (2021, November 6). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1700-1712. https://www.thelan cet.com/article/S0140-6736(21)02143-7/fulltext

Dickinson, K. (2023, April 27). Nagomi: The Japanese philosophy of finding balance in a turbulent life. Big Think. Retrieved August 9, 2023, from https://bigthink.com/the-learning-curve/nagomi/

Kim, E. J., Son, J. W., Park, S. K., Chung, S., Ghim, H.-R., Lee, S., Lee, S.I., Shin, C.-J., Kim, S., Ju, G., & Park, H. (2020, July 1). Cognitive and Emotional Empathy in Young Adolescents: an fMRI Study. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(3), 121130. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7350548/

Konrath, S. H., O’Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2010, August 5). Changes in Dispositional Empathy in American College Students Over Time: A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2). https:// journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1088868310377395

Kotera, Y., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2020, July 28). Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 337–361. https://link.springer. com/article/10.1007/s11469-020-00363-4

Litt, J. S., Alaimo, K., Harrall, K. K., Hamman, R. F., Hebert, J. R., Hurley, T. G., Leiferman, J. A., Li, K., Villalobos, A., Coringrato, E., Courtney, J. B., Payton, M., & Glueck. (2023, January). Effects of a community gardening intervention on diet, physical activity, and anthropometry outcomes in the USA (CAPS): an observer-blind, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(1), e23-e32. https://www. thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00303-5/ fulltext

Miller, M. (2022, March 14). The 3 Parts of Empathy: Thoughts, Feelings and Actions. Six Seconds. Retrieved July 29, 2023, from https://www.6seconds.org/2022/03/14/3-parts-of-empathy/

Mogi, K. (2022, November 14). “SUCCESS ISN’T A PREREQUISITE FOR HAPPINESS”. THE Stylemate. Retrieved August 9, 2023, from https://www.thestylemate.com/erfolg-ist-keine-voraussetzung-fuerglueck/?lang=en

Pywell, R. F., Heard, M. S., Woodcock, B. A., Hinsley, S., Ridding, L., Nowakowski, M., & Bullock, J. M. (2015, October 7). Wildlife-friendly farming increases crop yield: evidence for ecological intensification. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 282(1816). https://doi.org/10.1098/ rspb.2015.1740

Thornicroft, G. (2006). Shunned: Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness. Oxford University Press.

Zaki, J. (2019, June 7). How to increase empathy and unite society. The Economist. Retrieved July 29, 2023, from https://www.economist. com/open-future/2019/06/07/how-to-increase-empathy-and-unitesociety

Fall 2023 Issue 11

Unveiling the Transformative Tapestry: Where Collaboration Meets Community-Inspired Beginnings

By Raquel Acedo-Rubio Head of

Learning

Mount Zaagkam School, Indonesia

At the core of Mount Zaagkam School’s approach to community involvement lies a profound commitment to the defining principles of the IB learning community (IB, 2023). Embracing a holistic educational environment, the school honors and values its entire community ecosystem, from students and families to the broader community. This outlook lays the groundwork for a thriving philosophy of collaboration, nurturing an environment dedicated to the inclusion and well-being of all members.

At times, in contrast to best practices, educational institutions have segregated the roles of parents and teachers in the child’s development. However, this distinction overlooks the reality that children absorb both values and academics within and beyond the classroom walls. Students’ observations of adult interactions, decision-making, and problemsolving, whether in school or the community, significantly shape their self-esteem, beliefs, and worldview. Collaborative efforts between parents and the school foster an inclusive environment that recognizes both individual differences and shared experiences. Witnessing a harmonious partnership between home and school cultivates positive attitudes toward education, resulting in enhanced achievement

Parent involvement and representation through school communities such as the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) occupy a central role in MZS’ educational approach. The PTA serves as a vital conduit, solidifying connections between students, teachers, parents, guardians, and the larger educational community, and strengthening a sense of partnership. It acts as a dynamic catalyst for advocating initiatives that prioritize and nurture student well-being and a sense of community and belonging.

From MZS’ vantage point, the distinction between a “traditional” start to the academic year and an innovative departure was illuminated by an organic collaboration with the school’s PTA. Members of the MZS community orchestrated a week-long series of captivating circus-related events designed to gently immerse students into the year. This approach was envisioned to lay the groundwork for an academic year marked by collaboration, inclusiveness, growth mindset, and an unyielding readiness to tackle the challenges ahead. Much like the interconnected circus performers crafting mesmerizing human formations, students, parents and educators were encour-

aged to come together, fostering unity and collective support.

The captivating performances mirrored the palpable excitement and enthusiasm for the endless possibilities the upcoming year held. As the curtain drew to a close on this inaugural week of acrobatics and wonder, the stage was perfectly set for a year of unparalleled engagement and collaboration, where every member of the school community plays a pivotal role in shaping the narrative of who we are and who we become.

References

International Baccalaureate Organization-IB (2023). The learning community. International Baccalaureate Organization. Retrieved August 25, 2023 from https://www.ibo.org/ programmes/primary-years-programme/ curriculum/the-learning-community/

Comer, J, and Haynes, N. (1997). The Home-School Team: An Emphasis on Parent Involvement. Edutopia professional learning. Retrieved August 24, 2023 from https:// www.edutopia.org/home-school-team

SERVICE LEARNING

and growth, irrespective of background (Come and Haynes, 1997).

12 EARCOS Triannual Journal

The 19th EARCOS Teachers’ Conference 2024

Theme: Awareness, Agency, and Action

MARCH 21-23, 2024

SHANGRI-LA HOTEL BANGKOK, THAILAND

SAVE THE DATE!

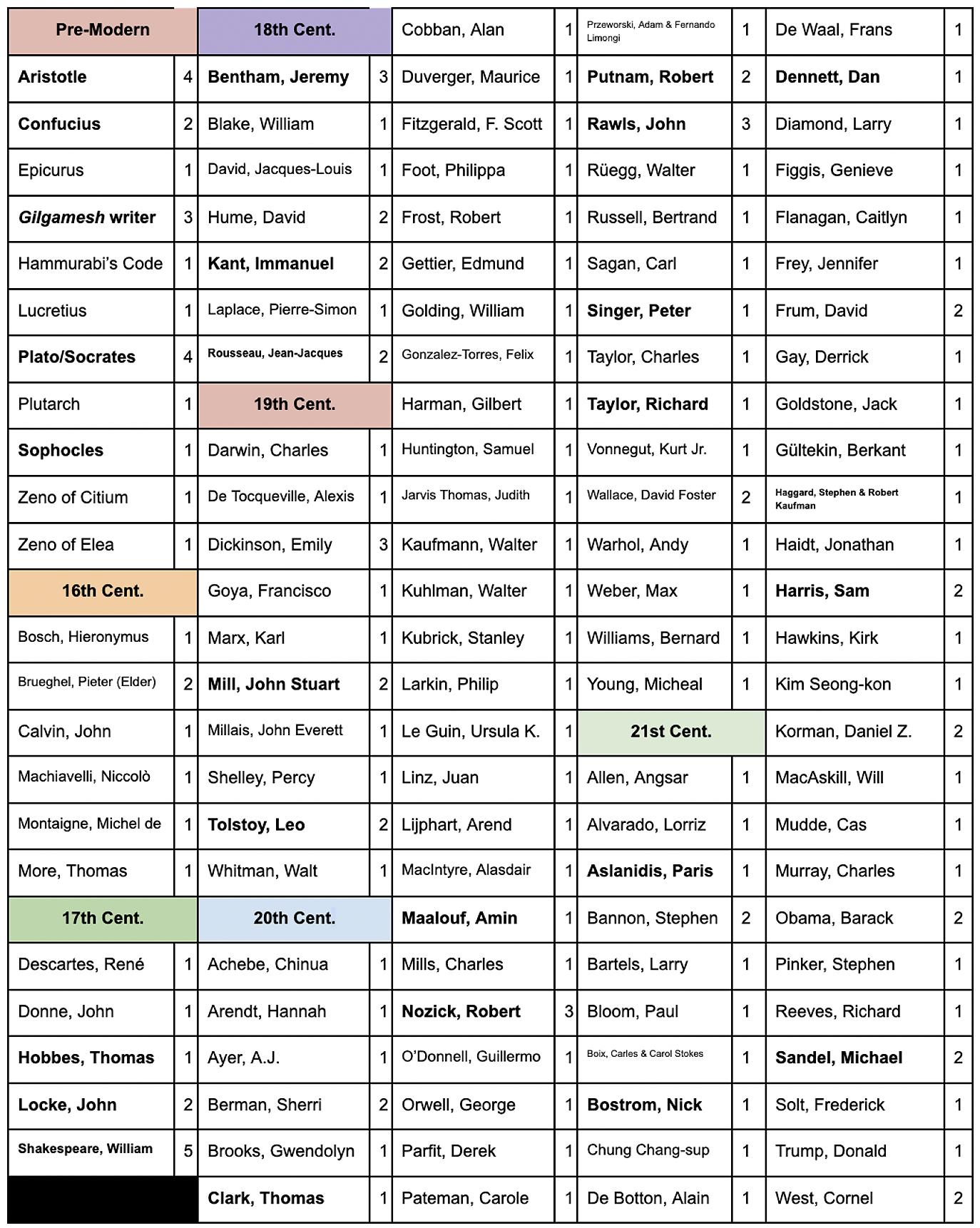

What can you learn about yourself while exploring AI?

By Mark William Barnett Vice President of Education and BSD Education

By Mark William Barnett Vice President of Education and BSD Education

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

14 EARCOS Triannual Journal

As a PhD student delving into the realm of Artificial Intelligence’s impact on classrooms, I recognized the challenges and possibilities it could bring for both educators and students. My investigation into how students respond to AI tools began just before the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when AI had limited applications beyond computer science and engineering education. However, the swift and profound educational influence of ChatGPT, launched in November 2022, took me by surprise. It is conceivable that we are only at the cusp of the disruptive effects posed by ChatGPT and similar advanced AI tools on the workforce and in the field of education.

As generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Midjourey have started to shift the culture of work and education, I think it is important to take a step back to understand the roots of AI, and what might be a beneficial way to look at how humans and AI can learn from each other. My understanding of the roots of AI started with reading and researching about how pioneers in the field shared their vision. In 1959, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert were both faculty at MIT who launched the now famous Artificial Intelligence Lab to develop primitive models of Neural Networks. Minsky and Papert started developing what came to be known as the “Society of Mind Theory”. The theory attempts to explain how what we call intelligence could be a product of the interaction of non-intelligent parts (Minsky, 2007). Minsky and Papert were both deeply interested in how intelligence is derived and how humans can learn from machines.

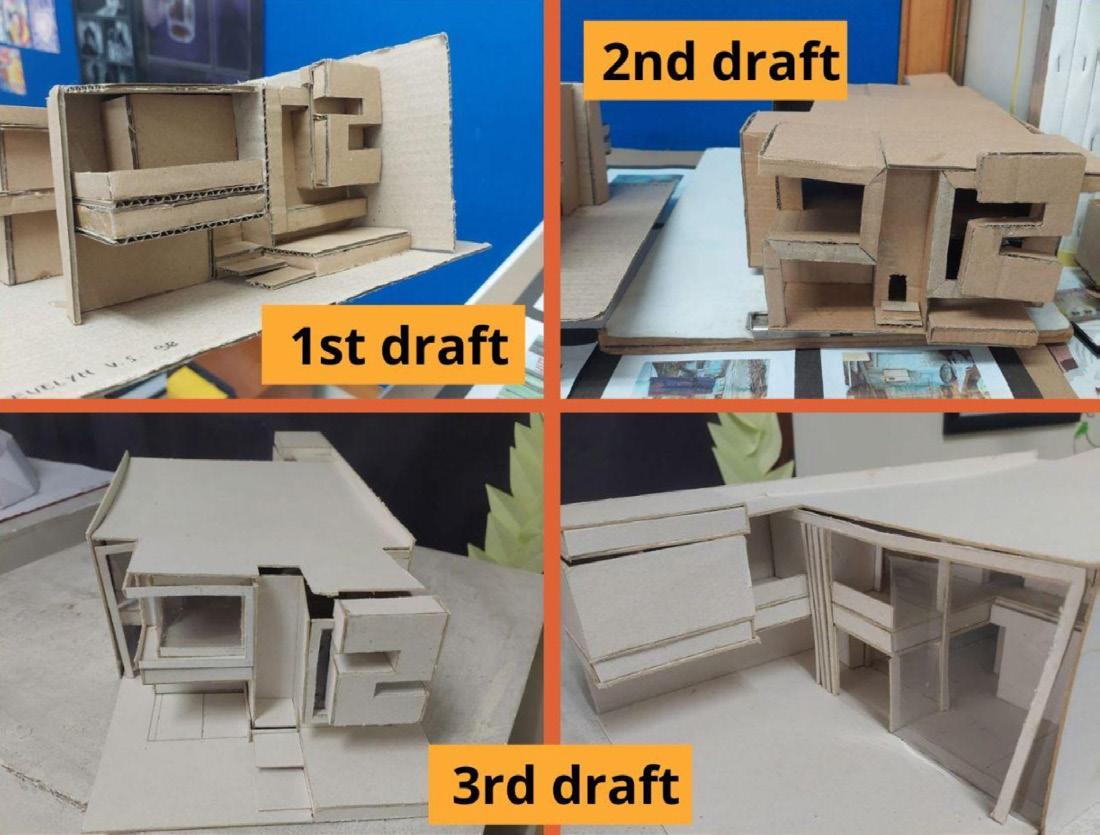

Eventually Seymour Papert would go on to further elaborate on his ideas through an educational pedagogy that he called “constructionism” which suggests that learning happens best when students have the agency to create artifacts, reflect on those artifacts and connect their learning to prior knowledge, thus developing deeper understandings of themselves and the learning. While Papert shifted his focus more towards computer programming for children, he never left his ideas of Artificial Intelligence behind. Papert created a programming language for children called “Logo” that required students to program a moveable turtle around the screen through a series of written computer commands like “move forward,” “turn right,” “repeat,” etc (Papert,1980).

While observing how students interacted with the on-screen turtle, Papert came up with a concept that he called “Body Syntonicity” that explains how children relate their own bodies to the movements of the turtle. So, if they wanted to program the turtle to move in the shape of a square, they would first think about how they would move their own body in the shape of a square, causing students to think about the steps before writing the code.

In my research with currently available AI, I have developed an analogous concept called “Neural Syntonicity” that describes

the relationship between a person and how they interact and learn from AI to learn more about themselves. For example, when students learn that AI is trained on a data set that contains bias, the bias is reflected into the output of the AI. With this in mind, my research aims to see if students can begin to see how human biases are caused by the quality of their training data. Human training data is simply a collection of your memories, events and knowledge. In my first stage of research, I worked only with AI Image Recognition tools to study relationships between visual information and how people label and predict image data, which is remarkably similar to how AI completes the same task.

In my upcoming research on Neural Syntonicity, I will be further exploring the concept, using chatbots like ChatGPT to see how people can learn more about their own learning process by interacting with chatbots, to further validate and bring credibility to the idea of Neural Syntonicity and to breathe life back into Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert’s original vision of students and teachers using AI as instruments to enhance learning, not to replace it.

You don’t have to wait for my research to be published to start thinking about this on your own or experimenting with your students. I highly recommend that you begin to learn as much as you can about AI chatbots, generative AI and the newly emerging field of “Prompt Engineering”, which just means the art of writing clever chatbot-prompts to get what you want with ease. What you will likely experience is that when prompting chatbots, you will encounter situations that cause you to have to re-state your intention, re-write your instructions, seek clarity, ask follow-up questions or scrap everything and start over. There are extremely valuable lessons in communication that can be learned from interacting with AI chatbots that both teachers and students can start to explore.

Keeping true to the legacy of Seymour Papert’s vision of AI and Constructionism, I suggest that you approach using AI chatbots with a sense of playfulness, making space for creativity and self-exploration, asking yourself “What can I learn about myself through this process?”

About the Author

Mark William Barnett is the Vice President of Education and BSD Education, an EdTech company aimed at providing digital-skills solutions for educators all over the world, including courses on AI, prompting and coding. Mark lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand and is set to complete his PhD at Chiang Mai University in 2024 studying in the legacy of Seymour Papert on the topic of Neural Syntonicity. He spent 20 years in the education space working at International Schools as a Design and Technology teacher and provides consultant services for makerspaces, design thinking, constructionism, robotics and AI.

Fall 2023 Issue 15

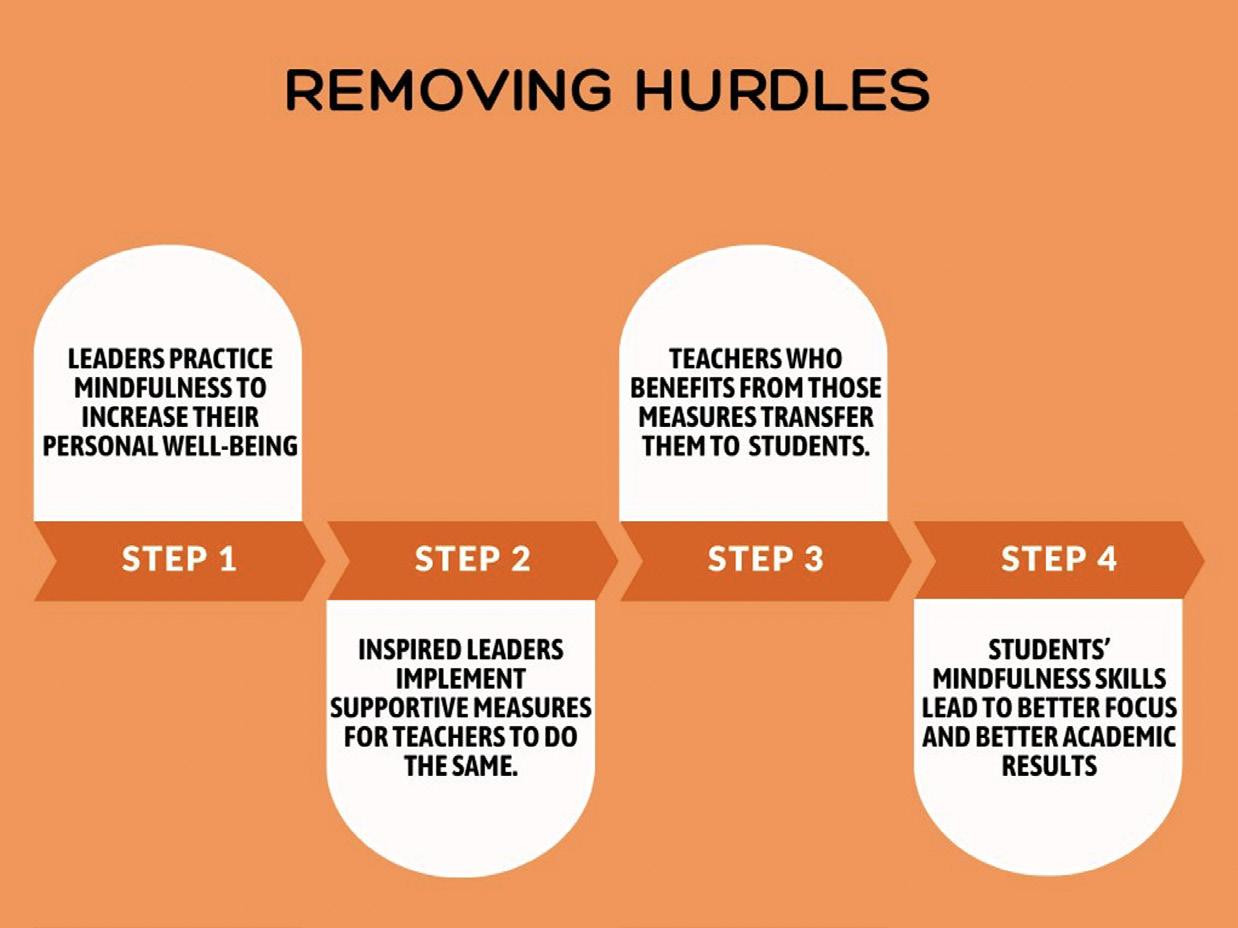

Leading Strategic Change: Building A Culture Of Inclusion At UNIS Hanoi

By Johanna Cena, Cheryl Hordenchuk, and Nitasha Crishna

By Johanna Cena, Cheryl Hordenchuk, and Nitasha Crishna

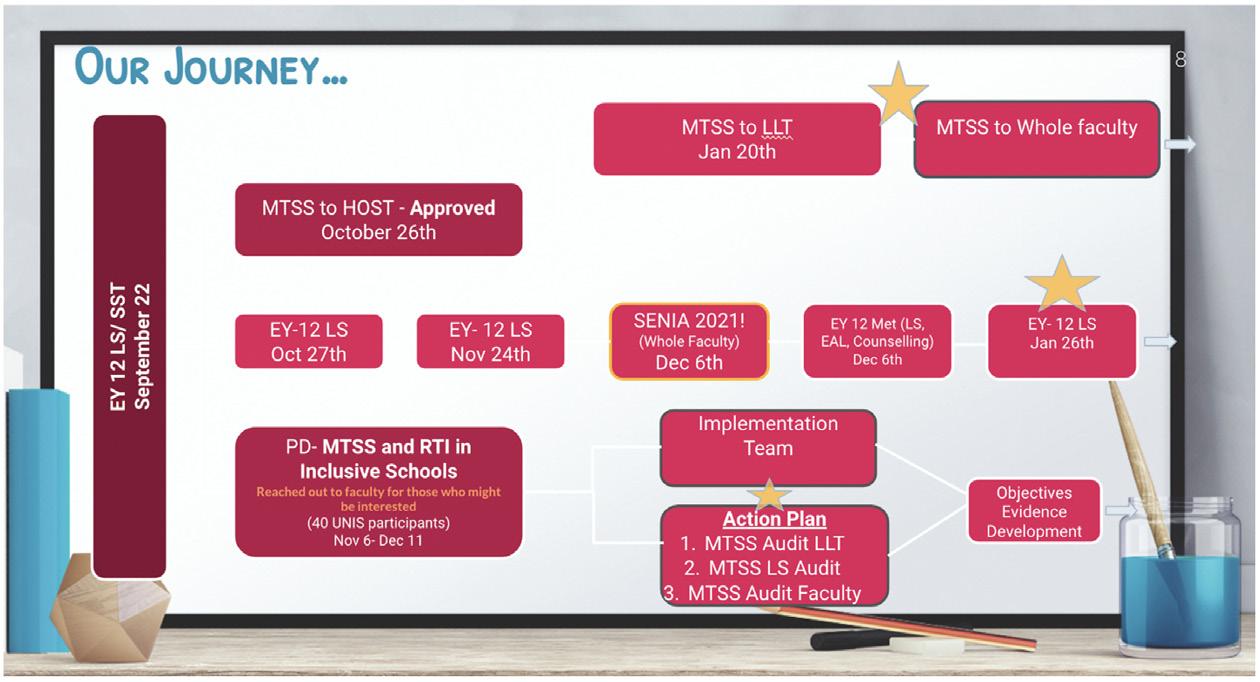

It was a hot Hanoi day in April 2021 when educational leaders, Cheryl Hordenchuk and Nitasha Crishna, at the United Nations International School (UNIS) in Hanoi, first met with the Student Success Team from across the school. While they knew that their team consisted of committed and experienced professionals, they quickly learned that they first needed work on articulating a shared vision and common understanding of how UNIS approached success for every student at UNIS Hanoi before the school could move forward.

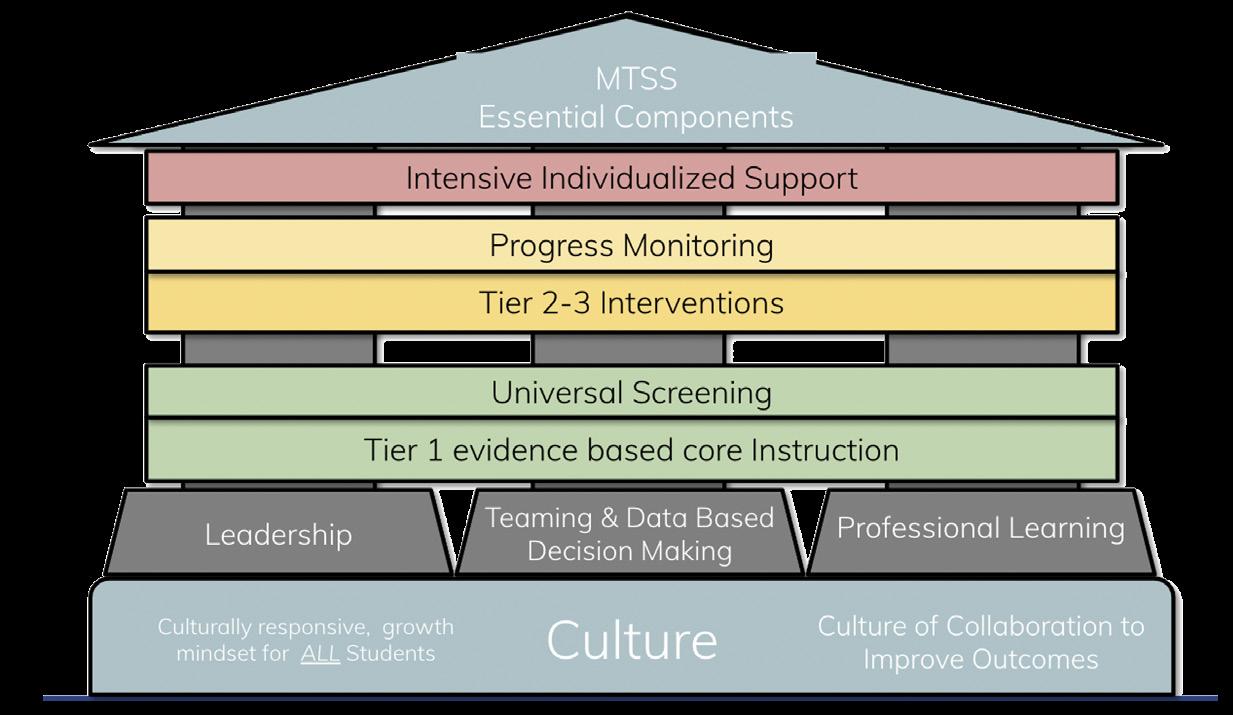

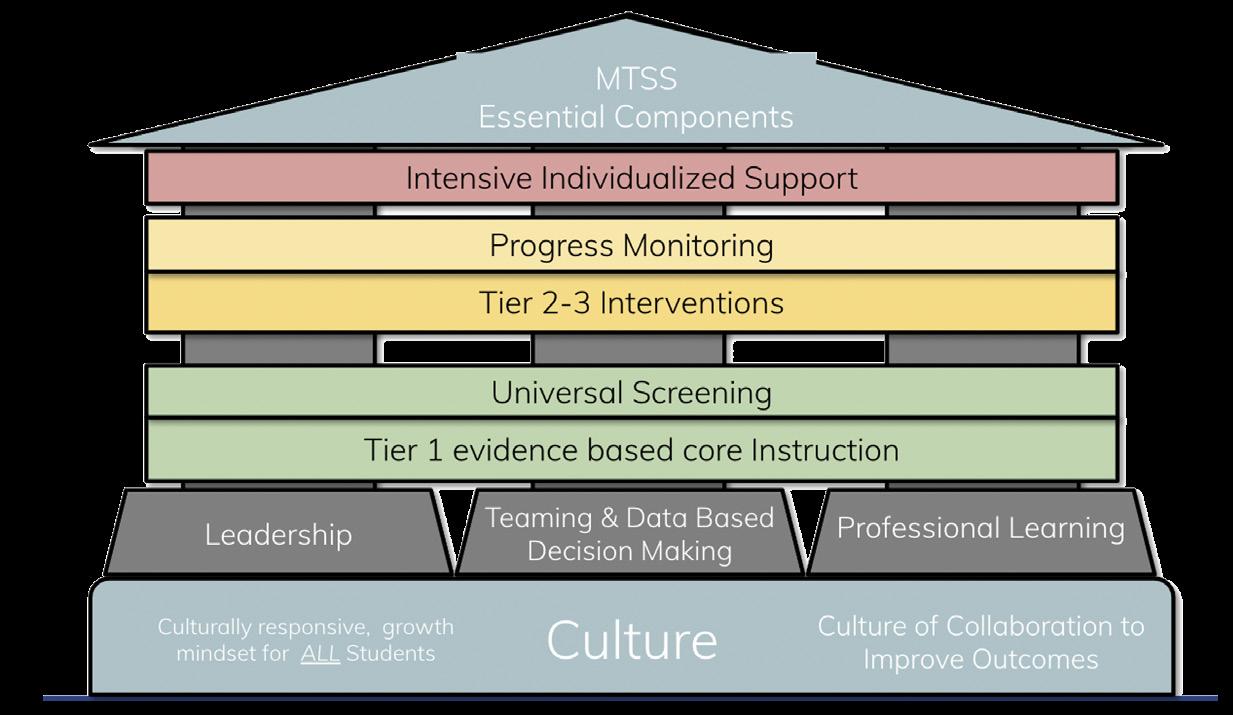

As the world continues to navigate the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of inclusive educational practices in international schools has become more critical than ever before. Cheryl and Nitasha saw this first hand as their students and staff came back to in-person learning. Collaborating with Lead Inclusion consultant, Johanna Cena they took a closer look at how a multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) could help to create a more inclusive culture of care and belonging so that all students could get the support they need. “MTSS is a proactive and preventative framework that integrates data and instruction to maximize student achievement and support students social, emotional, and behavior needs from a strengths-based perspective” Center on MTSS at the American Institute on Research.

Over the 2021-22 school year of distance learning and school closures, Nitasha and Cheryl engaged in leading the schoolwide Student Success teams, composed of the Learning Support teachers, the Speech Learning Pathologist and the School Psychologist, centered around helping the team work with a schoolwide perspective. They were guided by UNIS’s strategic directions which focused on an alignment of systems, their commitment to inclusion and neurodiversity and promoting the wellness of all members of the community.

Much of Nitasha and Cheryl’s leadership during what was a long and challenging year online was ensuring that the virtual meetings had time for people to connect, that they used the capacity and strength of team members to have generative conversations and then intentionally broke the work up into small manageable chunks.They knew the cognitive and the emotional load was heavy and as leaders they were very aware of the pace and balancing the needs of the team.

MULTI-TIERED SYSTEMS OF SUPPORT

Fig 1- Essential components of Multi- Tiered Systems of Support. Photo credit Lead Inclusion

Fig 2- UNIS Hanoi’s values and strategic directions

16 EARCOS Triannual Journal

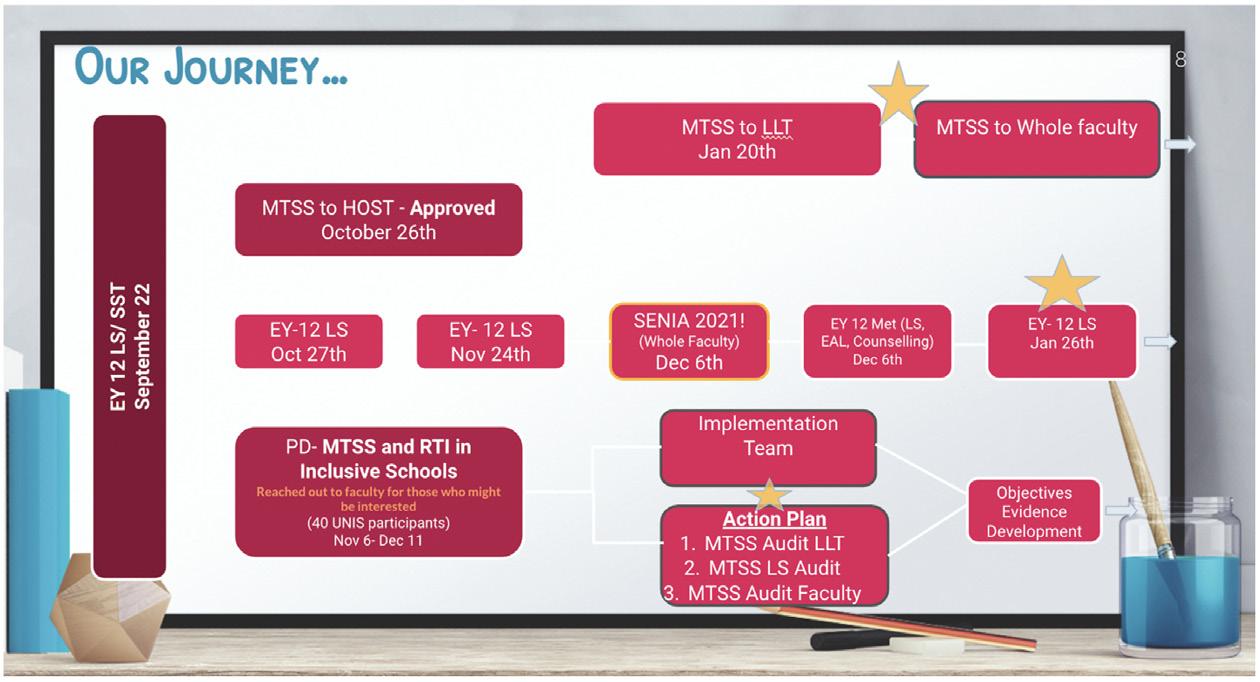

Image of yearly overview from the proposal to adoption of MTSS as a school

A big outcome of their work together was the recommendation to their senior leadership team that the school adopt the MTSS framework for the school. This recommendation stemmed from the six week professional development that a group of 45 cross divisional faculty members engaged in to learn the elements of MTSS. The Professional Development was facilitated by Johanna Cena and Nitasha and Cheryl could see how having a systems-based approach to creating the right conditions for MTSS would be most beneficial.

Once approved by the Senior Leadership Team, Nitasha and Cheryl got busy creating and writing an Action Plan. Working with the Elementary and Secondary Team Leaders and capitalizing on the wealth of expertise with MTSS in the UNIS faculty, they co-created an Action Plan to support the implementation of MTSS over three years.

UNIS Journey continued…Professional learning design for all.

A critical component of the action plan was to provide a schoolwide MTSS course for all staff. Cheryl and Nitasha reached back out to Johanna and in the fall of 2022 UNIS launched a schoolwide MTSS courses for all staff: assistants, specialists, teachers, and leaders. The course was implemented over a six month period of monthly online meetings and asynchronous learning between sessions. The model emphasized the shared belief that all students are our students, and focused on creating a shared culture and understanding of inclusive practices through MTSS. Throughout the course, staff collaborated in a variety of different group structures and sizes across departments, grade levels and divisions both online and in person.

It was important to create a space for staff to ask questions, understand multiple perspectives and to clarify ideas after each session by using a shared document which then drove adjustments to subsequent sessions and school documentation.

One of the foundational features of this model was the importance of providing time for all faculty to define common key terminology together and develop a UNIS hanoi terminology document accessible in Vietnamese and English.The definitions document ensures that all of the work UNIS does is now front loaded with clarity around what the different technical vocabulary means. This was one of the big successes of the work.“The definitions were a wonderful piece of the puzzle that pulled so much together for me.” UNIS teacher.

Another key element and success of the program design was providing prompts, tasks and collaborative time for teams to work on developing shared tools and resources for MTSS implementation catered to the needs of UNIS Hanoi. In these conversations, staff explored ideas around effective universal tier 1 instruction, data based decision making, problem solving and intervention support. From these collaborative conversations came the creation of a school wide behaviour matrix also co-written by all faculty. The behavior matrix was created by all teachers inputting what acceptable expectations of behavior look like and after several iterations has evolved into articulated behaviour expectations from the Early Years to Grade 12.

Having had the opportunity to have the entire faculty contribute to these foundational resources has meant that it belongs to everyone.

The intentional program design continued to balance the big understandings of schoolwide MTSS and each faculty member’s role in the system which helped to build a strong MTSS foundation.

What we learned

As leaders, it can be challenging to meet the professional learning needs of all staff. One of the key successes of this experience was the rich collaborative planning between Johanna, Nitasha and Cheryl.They had clear outcomes, open communication and the flexibility to adjust to the needs of the staff. Because ALL staff attended over multiple sessions, this was a transformative professional learning experience for the school. However, one important take away was the reminder that “less is more”. Asking staff to complete learning modules between sessions took away from the motivation and cohesion of the learning experience. The power of the learning was in the dialogue amongst staff.

Nitasha and Cheryl learned that leading UNIS in articulating a shared vision and common understanding of MTSS is challenging work, but approaching professional learning from the same inclusive mindset that educators aspire to for students empowers all staff to feel valued, connected and invested in a system that best supports all students

References:

https://mtss4success.org/essential-components

Fig 3 (From L-R) Nitasha, Johanna and Cheryl jointly presenting at the culminating faculty event at UNIS Hanoi

Fall 2023 Issue 17

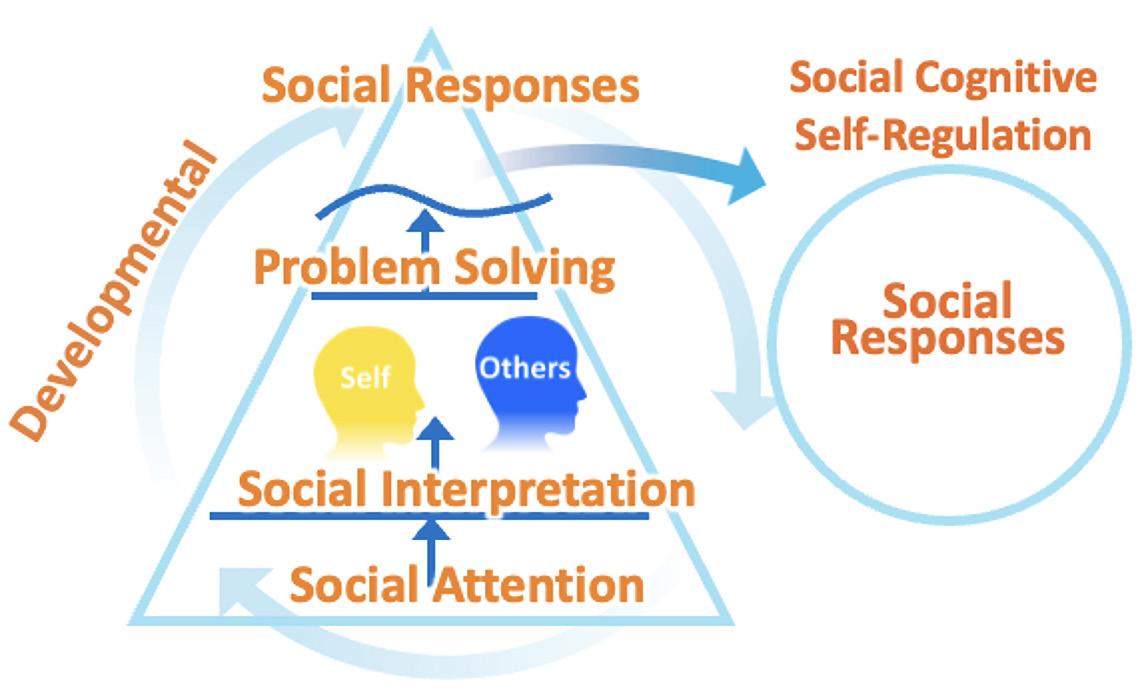

INSTRUCTIONAL COACHING The Social Mind at Work in the Classroom

By Michelle Garcia Winner, MA, CCC-SLP

By Michelle Garcia Winner, MA, CCC-SLP

Copyright 2023, Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Early in my career, as a speech-language pathologist working with students in a high school district, I found that many of them were perplexed by the social world. They felt left out and lonely. It was not uncommon for them to also struggle with aspects of academics, particularly when they were required to summarize and interpret socially based information presented in their curricula, or when asked to engage in written expression beyond journal writing. They also struggled with organizational skills and social initiation, as well as deciphering the main idea, whether they were conversing with others or asked to write a topic sentence. Informed by research and my students’ experiences, I created an acronym, ILAUGH, to illuminate different factors at play within the social mind that contribute to academic and social success. Now, more than 20 years later, the ILAUGH Model of Social Cognition continues to guide individuals, family members, and professionals to consider different aspects of the social mind and how each of these may be relevant to understanding and possibly helping individuals with different types of social learning styles.

ILAUGH Model defined:

I = Initiation of asking for help, connecting with others, as well as getting started on doing things that one finds harder to accomplish.

L = Listening with one’s eyes, ears, body, and touch

A = Abstracting and inferencing socially based information, whether it’s spoken, written, or presented visually

18 EARCOS Triannual Journal

U = Understanding and/or imagining one’s own and others’ perspective (thoughts and feelings)

G = Getting the main idea (also referred to as gestalt processing), getting organized, getting things done

H = Humor and human connection

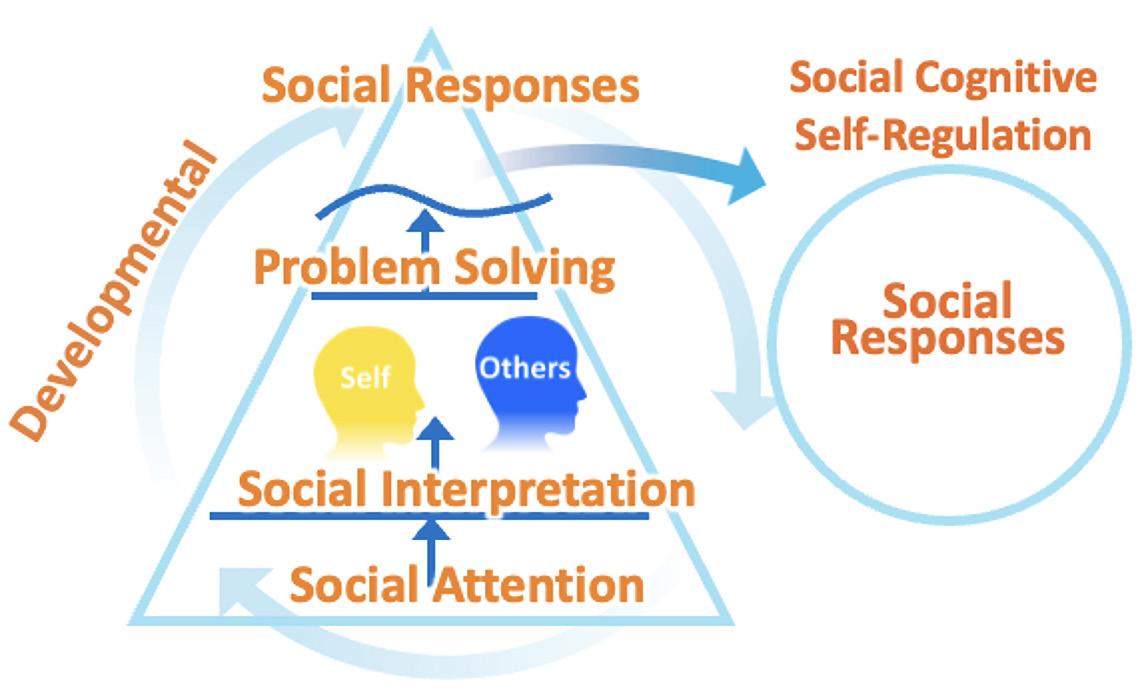

The reality is, when most people hear the word “social” they are likely to think about activities that involve people meeting up, such as when students hang out at school, or meet up for school dance. Yet, the social mind is not all about friendship, but it is all about making sense of people in context. Developmentally, beginning in infancy, neurotypicals emerge in their ability to form social competencies. To better understand this process, the Social Thinking® Methodology provides the Social Competency Model (SCM), a tool that encourages us to explore the real-time social cognitive (i.e., social thinking) process through which we interpret and possibly respond to socially based information across the vast range of contexts experienced in our lives and through what we read, hear, or see in text or media. The SCM explores the research-informed process through which we socially attend to interpret information, leading us to socially figure out (problem solve) what’s going on to determine whether a social response is needed or desired, or whether it should be withheld. Ultimately, how we make sense of ourselves in the social world leads to our ability to socially self-regulate our feelings and actions– which is what we refer to as “social cognitive self-regulation.” The easiest way to consider this information is through the graphic below:

The Social Thinking-Social Competency Model summarized in a graphic:

walk quickly, leading to this social response.

• When shopping in a grocery store and ready to purchase what you’ve gathered, you attend to where you should go to initiate the purchase and then interpret how to make that happen, problem solving whether this involves communicating with others and then producing the social response to gather your possessions and leave the area in a timely manner, so that others can efficiently move through this same process themselves.

• In classrooms, on playgrounds, in the community and at homestudents and adults are expected to attend, interpret, problem solve and respond to socially self-regulate their behavior, based on the situation.

Through our company, Social Thinking Publishing, Inc. We bring these ideas alive through story books. A very popular book that has been adopted for use into mainstream/general education classrooms for students roughly 6-8 years old is our, You are a Social Detective, 2nd edition paired with the related Teaching Curriculum and Support guide

While this information seems technical and somewhat sterile when exploring the graphic, now consider how this information plays out in real life:

• When a pedestrian crosses a street at an intersection, they attend to cars and, more specifically, the eyes of a drivers, who are stopped at the sign/signal, to make sure they are attending, interpreting, and then problem solving your actions, which should then lead to their refraining from moving forward. Simultaneously, you are also interpreting their desire to drive through the intersection. Therefore, you problem solve that you should

We offer many opportunities to learn more about the Social Thinking Methodology for free, through the exploration of our free articles and webinars that can be viewed anytime on our website, along with many more ideas for teaching all different age groups starting at 4 years old and spanning across adulthood through a range of products, all of which can be found on our website, www.socialthinking.com.

About the Author

Michelle Garcia Winner, MA, CCC is a speech-language pathologist who specializes in the treatment of students with social cognitive challenges, including but not limited to diagnoses such as Autism Spectrum Disorder, Asperger syndrome, ADHD/ADD, Twice Exceptional and Non-verbal learning disorder. She has a private practice in San Jose, California where she works with clients, consults with families and schools and she travels internationally giving workshops as well as being invited to train psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, and state policymakers. She presents many different all-day workshops and helps to develop programs for implementation in schools and classrooms.

Fall 2023 Issue 19

PROJECT-BASED LEARNING “Using Purpose Learning to Increase Belonging in the Classroom”

By Jessica Catoggio, Director of Professional Learning World Leadership School

Over a decade ago, project-based learning transformed my teaching practice. It allowed me to make space for student agency while still addressing my curriculum, it gave me the opportunity to assess students in alternative ways, therefore genuinely reaching more students than I ever had before.

I believed so deeply in it that I became an instructional coach, supporting dozens of fellow educators as they implemented these practices in their classrooms, trained parents on the ins and outs of “how teaching and learning have changed”, and became a fierce advocate for PBL in as many administrative offices as I could gain entry in order to tout its benefits.

Fast-forward more years than I’d like to admit, and I now am the parent to two adolescents, each on their own educational journey, AND have the great privilege of serving as the Director of Professional Learning for World Leadership School a purpose-driven, North American-based organization whose mission is to:

“Partner with K-12 schools to reimagine learning and create nextgeneration leaders.”

Diving head-first into this role at the height of the pandemic gave me the opportunity to deeply examine the ways in which we partner with schools, and more importantly, the work we do directly with teachers. Weaving my own experience into WLS’ well-established work around purpose and purpose learning quickly became the piece of the pedagogical puzzle I wasn’t aware had been missing from my own entrenched PBL practice: Belonging.

Purpose learning, with its deep roots in the best practices of both project-based learning and Design Thinking, provides a space for belonging in learning. Repeat: Belonging in learning. Learning in which all students belong, and have the opportunity to connect content to themself as an individual, and allows them to have real-world impact at the same time. Revolutionary. This is the meaningful environment I want for my own vulnerable, adolescent children on their formational journey to becoming world citizens.

Before one can understand purpose learning, however, it is important to understand purpose itself. Stanford University’s Center on Adolescence’s body of work is the most significant research to date on this important topic. As such, at World Leadership School, we base our work on Stanford’s definition of purpose:

20 EARCOS Triannual Journal

“…a sustained commitment to an identity-relevant life goal that is both meaningful to the self and intended to contribute to the world beyond the self.” (1)

Simply stated, purpose is a journey inside to understand oneself- gifts, identity, goals, and to contribute to something outside the classroom. Blue Zones research alongside Stanford and many others tell us that purpose-driven individuals are happier, live longer, and engage in healthier relationships.(3) Blue Zones, too, remind us that purpose in life is an ancient human practice spread across most cultures. The quest to understand “why I get out of bed in the morning” is called Ikigai by the Okinawans and “plan de vida” by the Nicoyans in Costa Rica. Likewise, we see this in our work with teachers and students. A clarified and articulated purpose is a priceless tool on the path toward happiness and resiliency.

“Blue Zones” are areas in the world that report the highest number of centenarians, and report “extreme longevity.” Scientists have studied these zones and have identified lifestyle habits that residents of these regions share in common.(2)

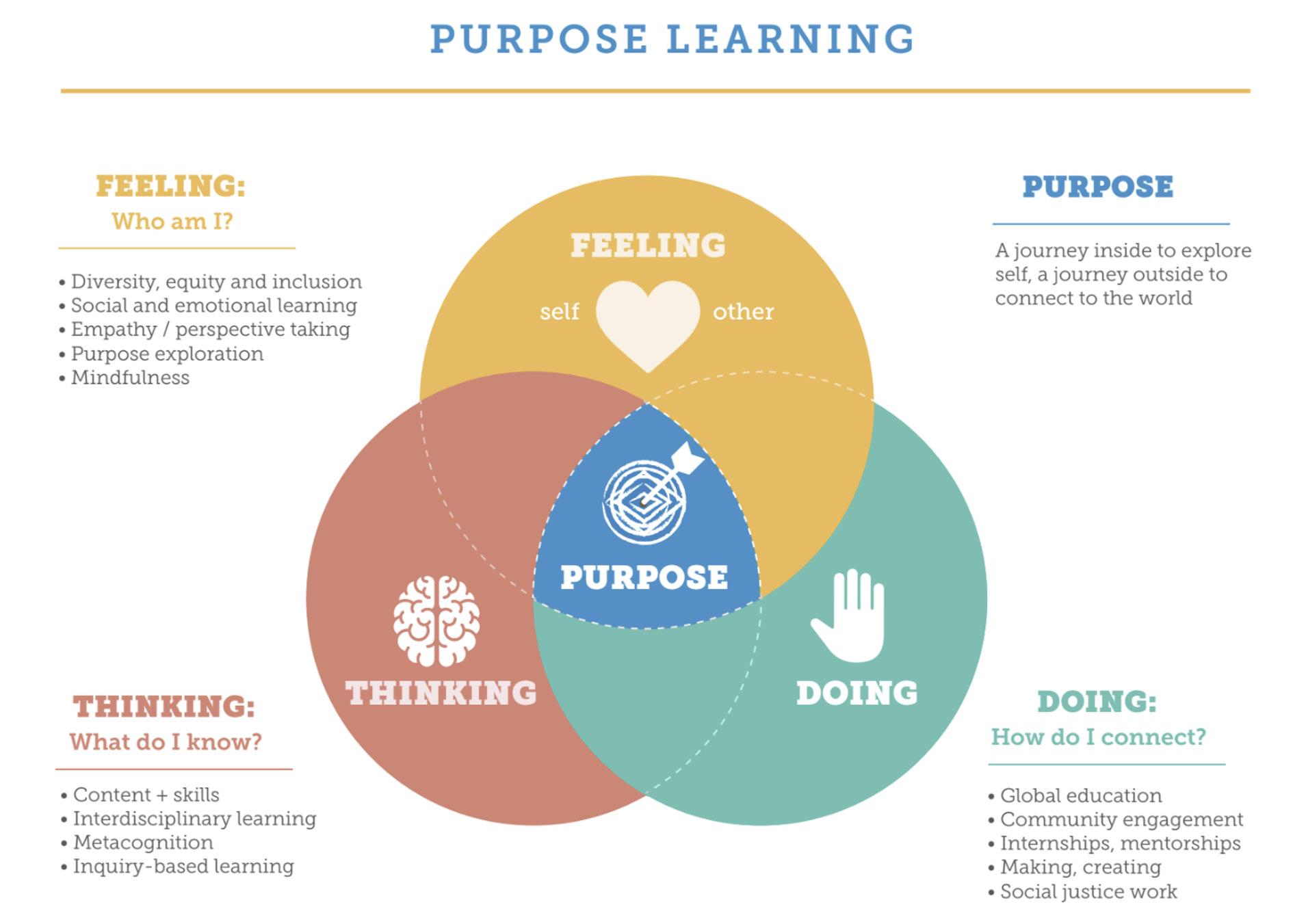

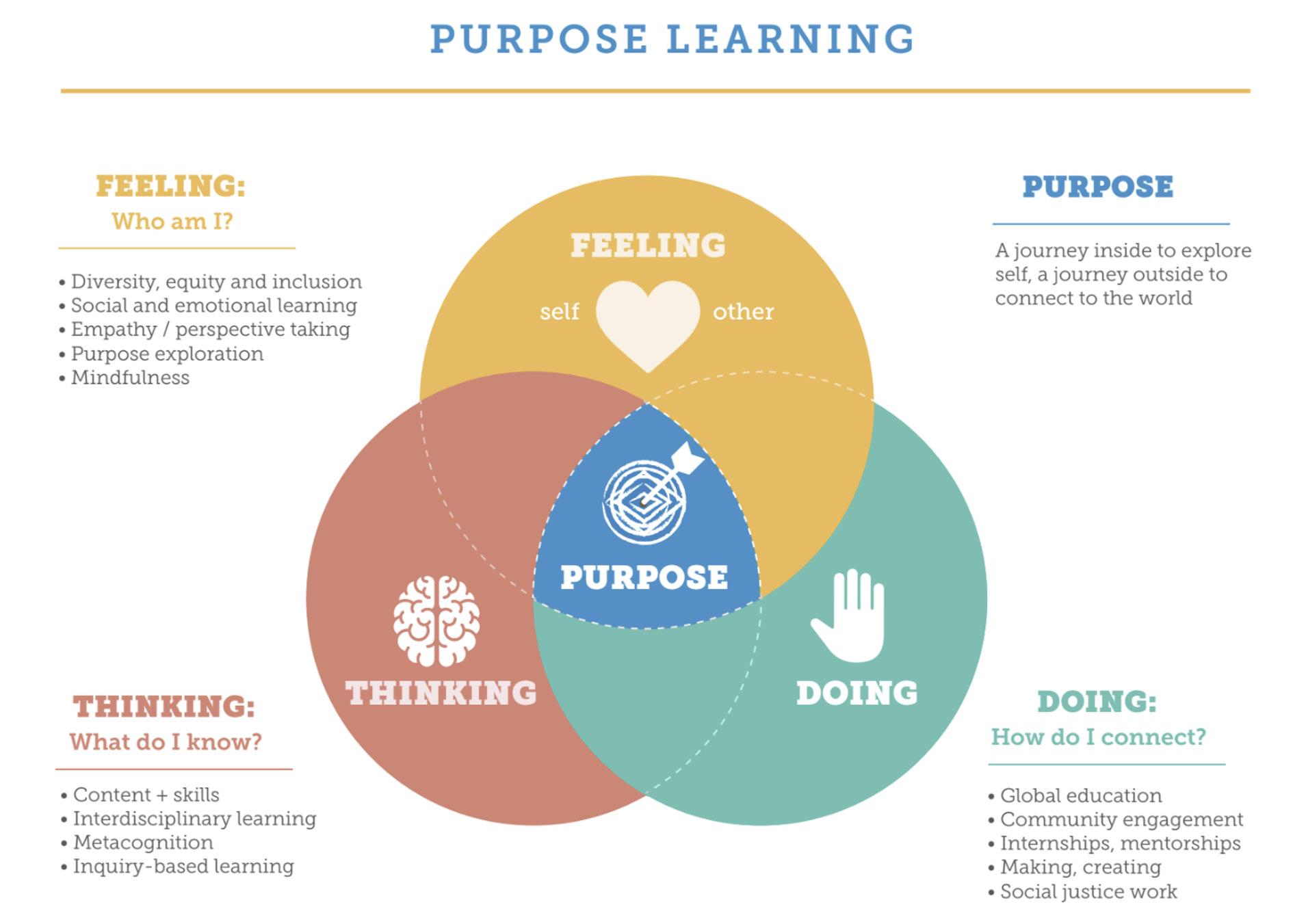

As purpose is a two-way journey, Purpose Learning is analogous to a busy, two-way street in which the “drivers” dynamically change lanes, detour at will, travel in the fast lane or slow depending on the road conditions, navigate roundabouts, and thoughtfully make return trips. Traveling one way on this busy street, “drivers” internalize and connect learning to self. In the other direction, the journey allows students to connect learning to the world outside of self in ways that are rich and meaningful. Additionally, as shown in the graphic below, the learning is no longer solely about the “thinking” (content, memorization) or the “thinking” plus “doing” (hands-on, community engagement, global ed) as my beloved PBL was. The learning journey in purpose learning brings in the crucial piece I was missing- “feeling”. (Identity, SEL, empathy, perspective taking). All of which leads to our key piece: belonging.

Purpose is an individual journey that is present in a community of belonging. Therefore, the importance of belonging cannot be understated. Belonging is also a Blue Zone habit, and a key indicator of student achievement, adolescent growth, and a basic human need. Recent research around culturally responsive teaching from Zaretta Hammond and others reminds us of what we already know and remember from our own school journey: belonging matters. Studentfacing organizations like Challenge Success share data that makes this impossible to dispute. An alarming number of adolescents do not feel a sense of belonging in their school community. One 2019 study showed “Between 17–29 percent of high school students and 14–27 percent of middle-level students say they do not feel that they belong.”(4)

There are a number of ways to schools today are increasing belonging- advisory programs that create safe spaces often top this list. Denise Pope at Challenge Success attests that “...when teachers intentionally design lessons that are meaningful to their students, build an authentic climate of respect into their classrooms, listen closely to students and incorporate their input, and grade in a way that students consider fair, students’ sense of belonging and academic engagement are more likely to be high.”(5) Purpose Learning.

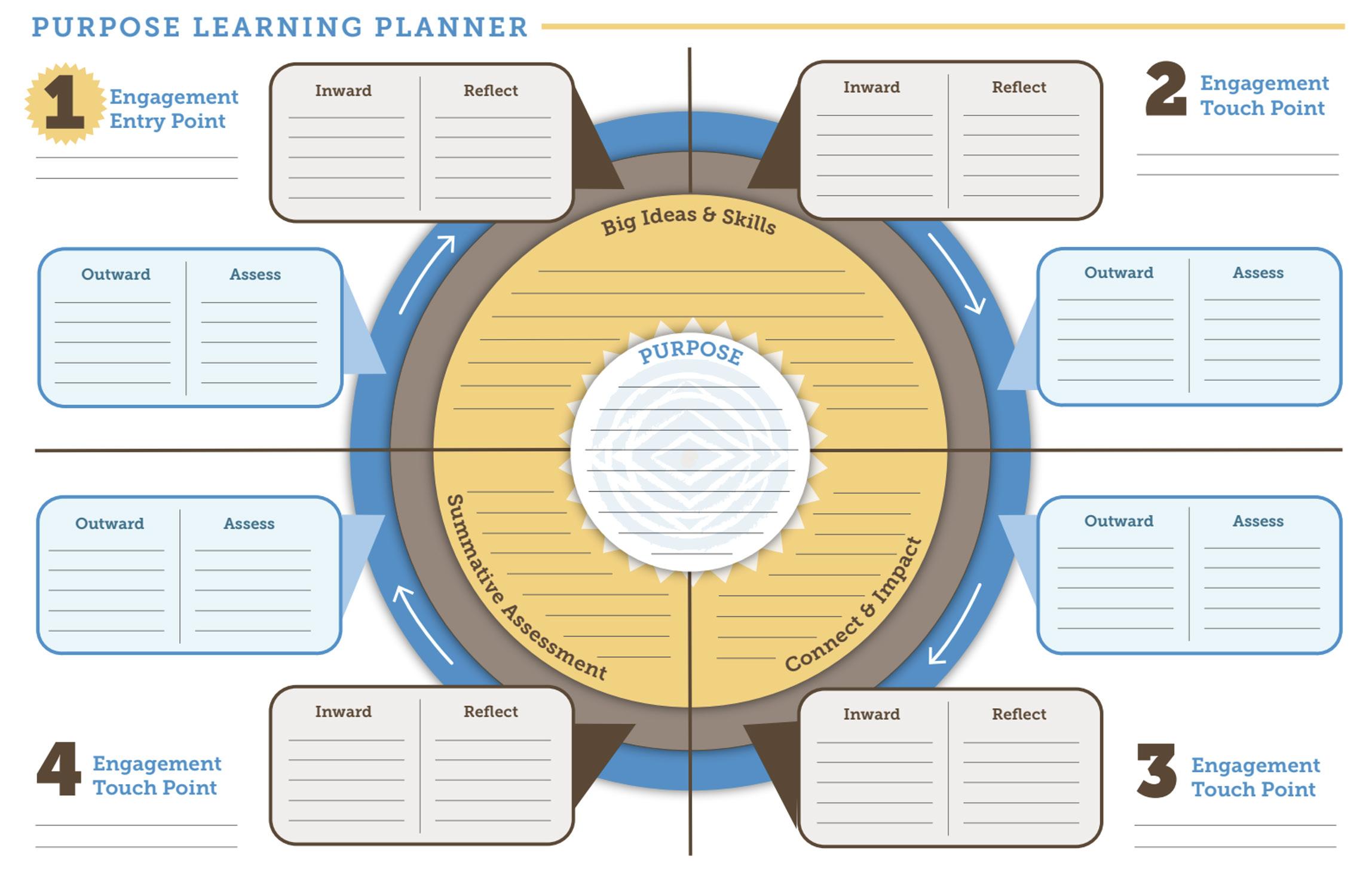

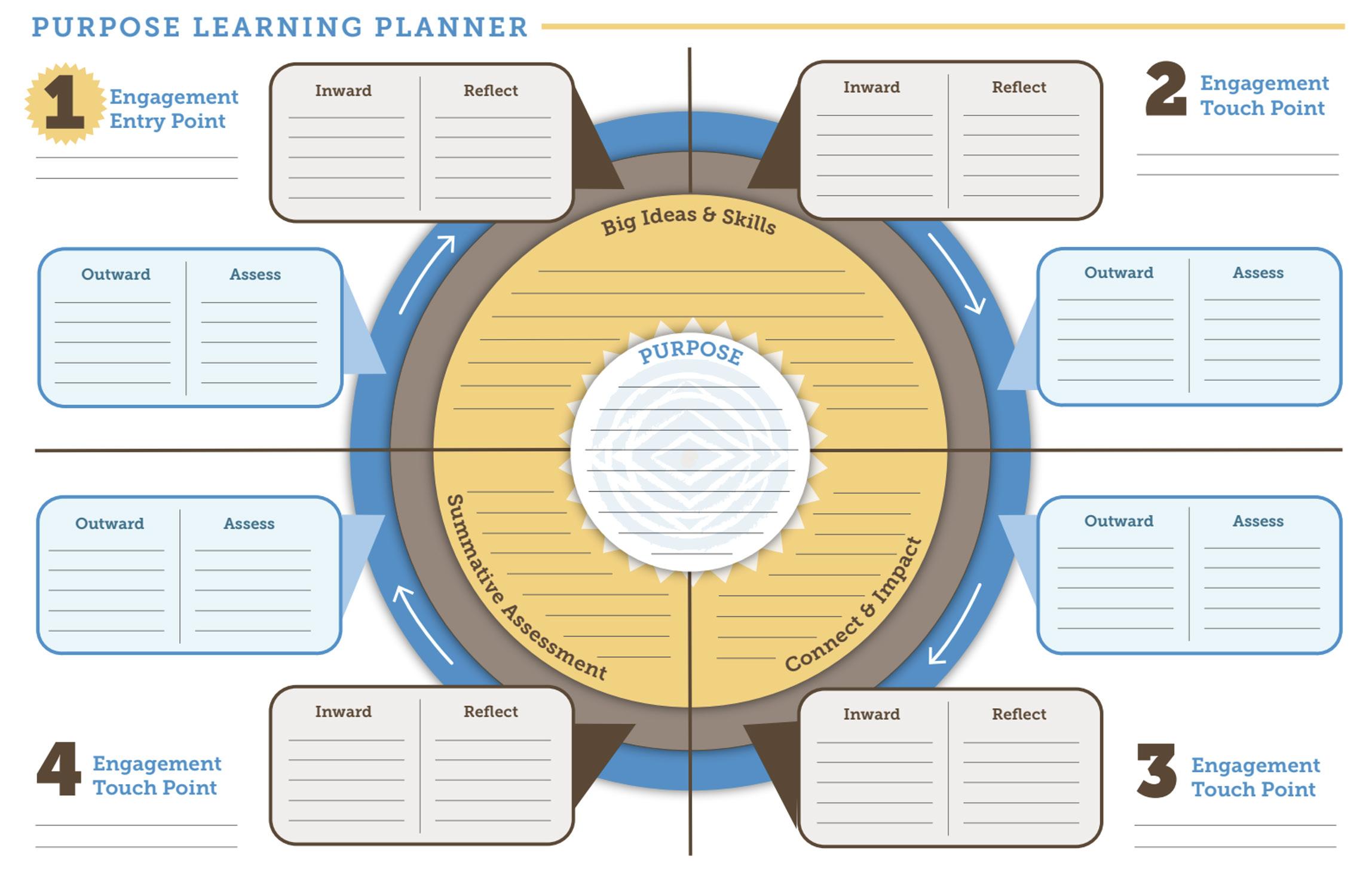

The Purpose Learning tools we have developed at World Leadership School, such as the Purpose Planner below, support educators seeking to increase belonging. As such, Purpose Learning is taking on many exciting forms in schools with whom we partner. For example, one of our schools launched an entire middle school in which memorization has been replaced by agile, self-expressive, and community-connected learning, and an AP History class in which students now think empathetically about content, tie it to their own personal or family history and then use an informed perspective to raise awareness in their community. No matter what form it takes these are classrooms in which students belong. They belong because learning is a two-way journey: connected to each student’s identity and also to the world outside the classroom

Fall 2023 Issue 21

I still believe that project-based learning is an important pedagogical tool. It remains beneficial in all the ways and for all the reasons I first came to believe in it. What we see in our hallways and read in the research, though, is that in this unique moment, our adolescents need more. They need learning environments that are celebratory of their identities, reflective of the world around them, and inspiring. They need classrooms in which they can experiment, fail safely, understand, and engage with the world around them. Students need to believe that they belong.

About the Author