5 minute read

Transporting grains and soya beans – common causes of cargo damage

Grains and soya beans are essential staple food sources and important raw materials for industries such as animal feed production, biofuels, chemicals, and food processing. This trade operates on an extensive scale, and the smooth maritime transportation of these commodities plays an indispensable role in maintaining global trade dynamics.

A new guide from The Swedish Club, Bulker focus: Carriage of grains and soya beans, explores the most common causes of cargo damage when these staples are transported in bulk and provides advice on how to prevent them.

It also focuses on fumigation and ventilation in detail and contains case studies illustrating many of the common issues faced when transporting these goods.

Senior Loss Prevention Officer, and author of the guide, Joakim Enström explains: “Soya beans and grains each show a very different claims picture, until we reach the pandemic period, when claims for both categories increased sharply.”

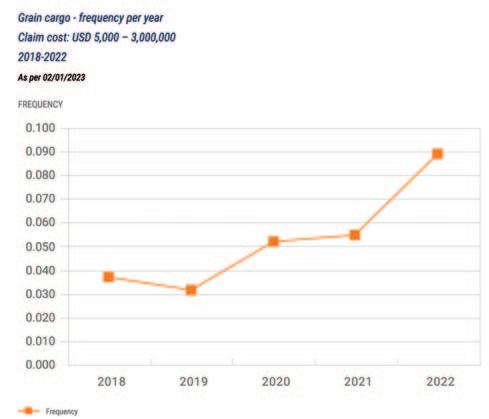

Grains’ statistics show that whilst an average of 5.6% of all bulk carriers insured have made a grain claim in the last five years, there has been a steady increase in the frequency of claims over the period. Only 3.7% of vessels made a claim in 2018 compared with 8.9% in 2022 (see graph 1).

Most claims occur in Argentina and North Africa, says Enström. “Interestingly, despite the many types of cargo damage faced by shipowners transporting grain cargoes, when it comes to claims, it’s actually cargo shortage that operators need to be prepared for.”

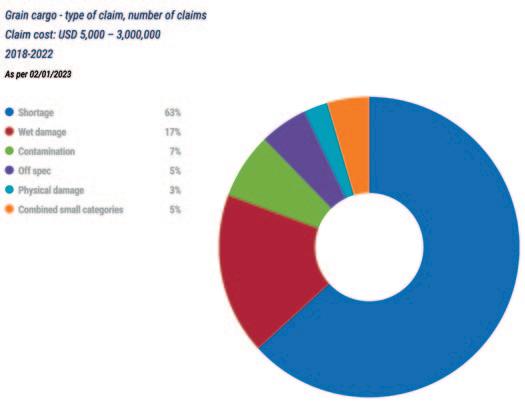

In the last five years, the Club’s statistics show that shortage was the most common type of claim for bulkers carrying grains, contributing to 63% of all claims. About

70% of these shortage claims occurred due to discrepancies between the vessel’s figures and shore figures with most claims arising in North Africa over the five-year period as a whole (see graph 2).

So why is this and what can ship operators do?

Enström explains: “In Argentina and many North African countries it is not unusual for there to be issues.”

In Argentina, mate’s receipts are presented to the Master by the shippers. The exporter (or importer) has the right to choose the weighing method for fiscal/customs purposes, which will invariably be the use of shore scales. It is not unusual to have discrepancies between the shipper’s figures based on shore scales and draught surveys.

In Tunisia and Algeria shortage claims often arise because receivers will not accept the established trade allowance of 0.5% of the bill of lading quantity. In the event of a shortage, only the shore scale figures will be recognized by the local receivers and calculation of the claims will be on that basis.

“Each country has its own rationale, but the bottom line is that the operator can find themselves seriously out of pocket through no fault of their own,” he says.

Before Covid-19 the Club saw few grain claims in China but since 2021 it has seen a steady increase in claims as a result of the pandemic. Says Enström, “The severe lockdowns that were seen in many cases delayed vessels and also made it difficult for surveyors to attend vessels for inspection. Crew and stevedores were also more hesitant to interact with each other because of the risk of becoming infected. This led to the crew not being able to verify the cargo operation and taking draught figures.”

Although each shortage claim averages to about only US$35,000 there are so many of them that they make up nearly half (44%) of the Club’s claims costs for bulkers carrying grain.

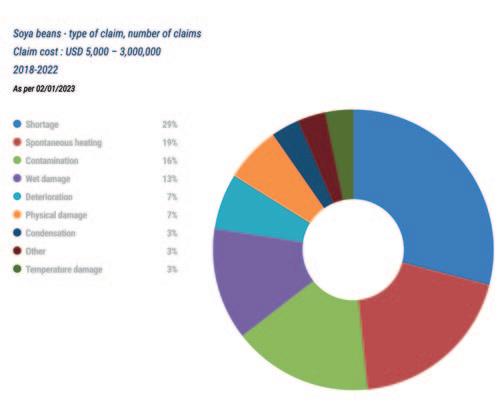

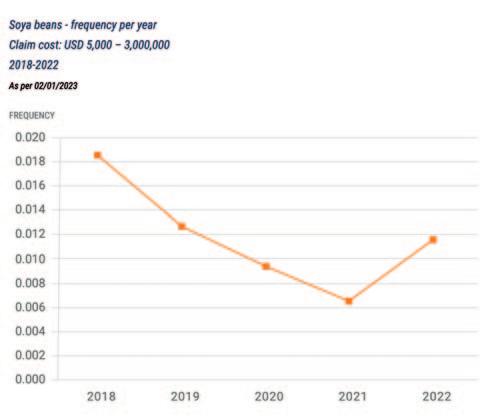

Soya bean claims show a different picture. In the past five-years only 1.1% of the Club’s bulk carriers have had a soya bean claim, but the average claim cost was US$54,000 — higher than that for grains (see graph 3).

During the pandemic vessels were forced to stay at anchor for extensive periods. “These delays can lead to heat damage which is a significant concern with soya bean cargoes,” says Enström.

The most common soya bean claim is for shortage at 29%, followed by spontaneous heating at 19% and contamination at 16% (see graph 4).

“When compared with grains, shortage makes up a considerably smaller percentage of claims — 29% vs 63% — says Enström. “This is due to different trading patterns and also due to statistics having been influenced by heat damage caused by COVID delays.”

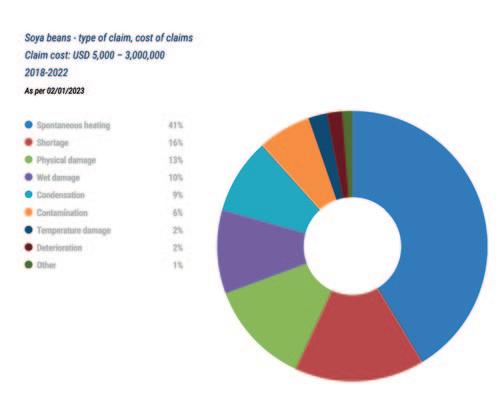

Looking at costs, however, the picture is very different. Spontaneous heating accounts for 41% of the Club’s total claims cost in this category, with an average claim cost of US$115,000. Shortage makes up only 16% of the total cost, with an average claim cost of US$29,000 and physical damage contributes to 13% of the total cost, with an average claim cost of US$103,000 (see graph 5).

Cargo self-heating depends on its moisture content, the temperature at loading, and voyage duration, says Enström. “High moisture content can lead to mould growth with an increased self-heating risk, particularly for cargo that already has an inherently high moisture content.

So what loss prevention measures can shipowners take?

There are a number of actions you can take to minimize shortage claims, explains Enström. “Carry out a draught survey before opening cargo hatches while unloading and don’t sign an incorrect draught survey report but add remarks. If hatches were sealed at the loading port, perform an unsealing survey before opening and ensure the unsealing certificate is signed by receivers and the document discharge progress. A surveyor can monitor operations and weigh discharged cargo.

“Prior to authorizing the vessel’s agent to sign shortage statements, consult the owner or Club’s correspondent. Obtain a completion statement affirming full discharge and empty holds and maintain dialogue with charterers/receivers who usually handle discharge — remember stevedores are effectively their employees. Note bill of lading discrepancies at discharge to prevent shortage claims.”

When it comes to cargo damage there are many way in which a cargo can be damaged, says Enström. “Wet damage and contamination are common to both grains and soya beans, with self heating being a major issue with the latter.”

There are a number of root causes for cargo damage, says Enström, but there are steps that can be taken to mitigate them.”

These include maintaining hold cleanliness to avoid loading refusal or claims upon discharge; pre-load hatch cover tests (ultrasound or hose) to prevent wet damage; taking swift action to address water ingress to prevent mould and future claims; and issuing a letter of protest for wet or mouldy cargo in case of heavy weather.

In addition the member should appoint a surveyor prior to loading to ensure clean, dry bilges and to record the temperature, colour and odour of soya beans in particular, prior to loading. Soya beans are high-risk due to respiration and oil content and a quick discharge is crucial, especially if the cargo is stored in piles with poor ventilation.

“Many of the claims that the Club has seen over the past five years could not have been physically prevented by our members,” concludes Enström.

“However the most effective defence against cargo claims is the maintenance of clear and accurate records and documentation of each stage of the voyage, from loading through to discharge, and constant record keeping including photographs and collecting samples during discharge.”

Bulker focus: Carriage of grains and soya beans is available to download free of charge in the Publications area of The Swedish Club’s website.