The Chania Town News

The people who live in Crete’s most interesting city

Douglas Bullis

Atelier Books Ltd. Co.

Postnet 18

P. Bag X-1672

Grahamstown/Makhanda

Eastern Cape 6140

South Africa

atelierbooks@gmail.com

Copyright © 2025 by Douglas Bullis, all rights reserved.

The right of Douglas Bullis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act of 1988. All rights reserved.

Nearly all of the images herein were taken by the author. In the few cases where images do not belong to the author, in some cases the provenance was not recorded at the time they wee recorded since there was no thought to assemble them into a book. Douglas Bullis has made all reasonable efforts to trace rights holders to copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the author welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements may be made in future editions. If you are the originator or owner of any illustration in this book that is not given credit, please contact the author through the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-998965-04-5

Cretan Wine

I was up before dawn. Pale buildings, pale leaves, pale light. Mist on the hills, dew on the grass, breath in the air. Autumn smells of moss, thyme, burnt weeds, wild garlic, basil, dill.

I neared the kitchen. The smell of lamb and bread merged with the acridness of a pigsty and the sweetness of a bower of mallows. The table was gouged from years of sliced loaves. Somebody threw me a glass. I caught it in midair and filled it from an unglazed wine pot on the table. They cheered. Later I was told that everyone had a glass thrown to them before they sliced their first piece of bread for the day.

in the village. Coarse salt in metal dishes. Lamb boiled in whole spices. Trays of olives. Apples.

As they filled their mugs, they spoke of the long day ahead.

Someone muttered that so-and-so was planting vineyards. Someone else responded that vineyards always got planted when there is hope in the future, while olives go during times of doubt.

The wine was musky and tart. It went well with the traditional grape harvest breakfast. Hard-boiled eggs mounded in bowls. Square trenchers of barley and rye. Bowls of honey and yogurt. Wedges of ripe graviera cheese, the best

A moustached old man in a weather-beaten hat made a doll for his grandkids out of a pine cone, with dry grass for hair and chickpeas for eyes.

We all trooped outside and hopped aboard a tractor cart. Red-faced old men cradled pink-faced granddaughters. Everybody waved good-bye to the rooster flapping his wings and making a grand show of himself. He would have been more subdued had he known he was dinner tonight.

The cart slipped through olive groves into the dawn. A quarter-hour ride took us to the first vineyard, a small holding on a ridge. Venus, that so brightened evenings last spring, was rising now in the fall. Someone recited stars stories, half ancestry, half locale. One constellation chased another, which turned with a raised stick. A neighboring town name was slipped in, then the nickname of a landlord they all loathed. Boys’ eyes widened as they heard their surroundings turned into tales.

We rocked and tumbled against each other as the cart lurched in the ruts crossing a dry stream bed. As we ascended the fog thinned, delicately revealing mist’s spirit of place — how things seem far even when near; how shadows find their density as the mist thins; how mist curves and folds and vees in unison with the land; how grey unveils day’s pastels; how the spring nestles itself in grass modesty; how the stream lives moments as seasonlessly as it lives centuries; how we experience ourselves that way when we become what the stream is to the sea.

When we feel the land’s foldings as though they were our own, from hill to hollow to grove to pool, winding and coiling and descending and joining; until one day, now careless of self as of knowing and end, we come to know that I is not a me, I is a We.

It was the first time I had a thought that did not come from my mind.

We passed rows of trees, hollows and copses and gullies and fords. We lifted over the gravelly crest of a hill, saw a sudden strange vagueness, a shape that wasn’t but was, a life jelling mist out of its own breath, then dimensioning to being and acquiring humanity. I squinted, looked sharply, saw one ... two ... three ... fivesixseven, maybe more.

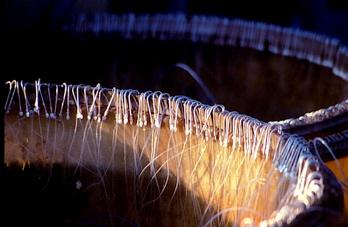

The locals knew the familiar mounds, the stones in heaps, the grass-haired posts, the bower where we would sleep after lunch. Its ferns were now spiderweb droplets dappled with dew. We got down from the cart, twisted our waists to take the aches out of our backs. One of the men shook a vine with a stick, spattering dewdrops in a scatter of flung silver. The women threw down the kalafia καλαφια baskets for the grapes and handed our lunch hampers to the children to put in the shady grove where we would eat.

Everyone chatted as we arrived at our allotted rows. Our rows were distinguished from others by blue paint on the end posts. Someone bent down to strip off a few grapes. He nibbled a few. ’The grapes are ready’ he informed me, ’when the skin breaks easily as you bite them. But the smart farmers let them ripen a week or two longer to reach their full sweetness.’ He wiped his hands on the dew-wet grass.

He taught me every imaginable detail about grapes that day. Since vine leaves turn color nearest the ripest fruit, I should look for the prettiest leaves as I paw through the maze. The more grape clusters to the bunch, the better the wine. He pointed out some mouldy grapes near the ground that ’smoked’ when he nudged them with a stick. ’Don’t breathe it or you will catch a cold this winter. If you see vine leaves punctured from a hailstorm, pass them by; their clusters will be ragged and the grapes too small.’

Two to a row, each with a καλαφια hooked into our elbows, we moved surprisingly quickly. Vine leaves trembled. Insects scattered wildly. Within minutes our sleeves were dew-soaked to the shoulders. My hands acquired a purple stain that didn’t wash out for days. Painful fissures opened on my fingers.

The work was coldest during that first row of the day, but there was the promise of warmth amid the colours gelling out of the mist. The work became not quite so cold, then not quite so uncomfortable, then not so bad. My back still ached as I groaned down for low fruit. Swallows skreeked as they devoured insects above the field-edge grasses. Day colours emerged first along the ridge tips even as the valleys were still misty with the descending greens of autumn, bursting and ripe and poised for the turn.

Four thousand years of experience understood in a glimpse.

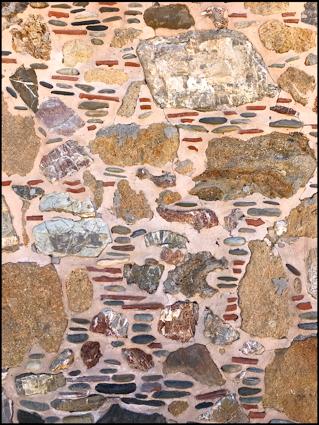

I rose from my cutting to survey the long rows ahead. Signs of a poor region abounded. House walls made of broken rather than cut stone. Some were whitewashed, most not. A communal bread-oven loomed on a mound, its smoke-dark fire pit under a dome crusted with ashes. Carved stone laundry basins lined a wide spot in a stream; in one of them was a tangle of shirts that had been left to soak overnight.

Nearby was a circle of stones that marked an aloni αλόνι or threshing pad for barley. In the distance was the grass-edged meander of a seasonal rivulet so small that no matter how hard or long the rain, it would remain always a rivulet thanks to the water-draining porosity of Crete’s limestone geology.

I mused at the notion of a stream fated by the land to go nowhere. Then I looked at the people around me.

Gathering the grapes, a silent kouvalias κουβαλιάς plodded up and down the rows. A wide-mawed kofini κοφίνι was strapped to his back. He reached the ragged line of grape cutters and muttered, “El-laaa” as he bent to one knee. A flurry of kalafia καλαφια basket passed over the rows and were upended to into his κοφίνι. “Ka-laaa,” he rose as the baskets were passed back to their cutters. He wiped his forehead with his sleeve and leaned into his trudge. The huge basket now creaked under its load.

The harvest cart was stained from years of broken fruit. It smelled of mould and grape must and manure. His shoes sagged over the ladder rungs as he centred each foot before giving the rung his full weight.

At the top, he grunted, “Hoof-laaa”, dropped his left shoulder sharply and thrust forward from the waist, hurling the grapes into the cart in a blur of purple. He stepped down as carefully as he did going up. His long trudge back was as silent as before.

Lunch time passed in a flurry of wildly waving spoons and deep quaffs of wine, followed by a long snooze in the grove. A few older folks poked out the soft parts of their bread and then used the crust-rings to play toss-pin against a twig stuck in the grass.

When I awoke I was enervated from too much exertion early in the day and too much wine in the middle of it. I followed the lead of the others by hopping up and down while waving my arms in giant angel-wing flaps. A dog came up to me, wagging its tail in short wiggles, letting me know it wanted to be friends.

Work in the heat of the afternoon went slower as cutters gossiped and told stories. I watched the work styles of the others. Some took it easy, standing up periodically to rest their hands on a vine stake and enjoy a long look around.

Others buried themselves in the leaves and never seemed to emerge. Somebody started an overly long story they already knew. Their eyes rolled and they gazed at the sky as he droned on and on.

Some knelt as they worked each plant, then rose to go on to the next. Others stayed bent all the way down the row. Some complained. Others laughed. Still others sang. The kalafia filled at about the same pace no matter what they did.

My soreness was gone by late afternoon. Everything seemed distilled — colours, smells, pleasure, laughter, life. Then the field’s owner arrived towing a cart with two large flagons of wine.

His shout, ’Pollliii kalllaaa’ πολλλιιι καλλλααα was the signal to stop. Plastic glasses were filled, the froth blown off. They squinted through the brown crimson into the sun.

It was their first taste of last year’s wine, still grapey and, to outsiders who don’t know Cretan wine, too maderised and sweet.

III

’Too maderised and sweet’ is a taste that goes back at least as far as the sixteenth century. The scholars of Oxford labeled it vinum Creticum and averred it came from Monemvasia in the Peloponnese. They were wrong by two centuries and two hundred kilometres. In 1420 the Venetian Senate referred to Cretan wine as ’from Malevyzi Μαλεβύζη on Candia [Heraklion].’ That tongue-tangler of a word Μαλεβύζη became ’Malmsey’ by the time it hit England’s shores.

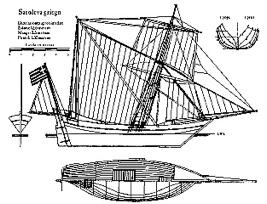

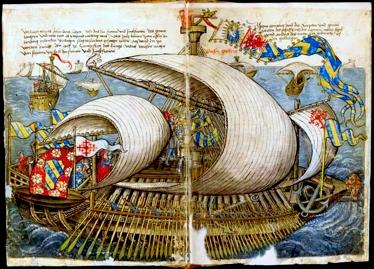

The Arsenali shipyard in Venice designed a special vessel for wine transport — the rakesailed sacoleva σακολέβα. Its wineglass-shaped hull became the FedEx of the wine trade.

In 1554 a Venetian accountant with the nicely euphonic name of Leonardo Loredan totted up the totals of Crete’s wine trade:

The city Candia and its province make 14,000 butts of wine. Of this, 200 butts of moscatti go to Flanders because it is not of too good quality; 500–600 butts of liatici are exported to Venice and elsewhere. Chissamo [Kissamos] and apokorona make about 2,000 butts for Flanders. The rest is logade and cozzifalli, which are sent to Flanders, Venice, Constantinople, Alexandria, Messina, and Malta.

Since a butt was 104 British imperial gallons, the above export was roughly ten million of today’s bottles. No wonder the Venetians designed the sacoleva σακολέβα to get it to market as quickly as possible.

Even the fastest boats on the Mediterranean had their limits. During Crete’s era of Venetian suzerainty, the island’s wine was stored in pithoi and shipped in amphorae. Both containers allowed enough oxygen to seep in to turn the wine to vinegar once the sugars had converted to alcohol.

While the sacoleva sliced like a dagger through the modest wavelets of the Mediterranean, it was no match for the merciless whiplashes north of the Bay of Biscay. Wine for Northern Europe suffered the ignominy of being offloaded in Jerez or Lisbon to wallow northward in carracks built for the ingots and lumber of the Age of Discovery, not the silks and spices of the Age of Merchants.

In the sixteenth century it was discovered that wine shipped in airtight oak casks from Madeira to Britain would turn brown and become smoke-flavoured and sweet without turning to vinegar — a chemical reaction called maderisation, induced in an airless container crossing warm seas.

The Cretans from Malevyzi Μαλεβύζη near Rethymnon hit on a technique of hastening the process by deliberately heating the wine before transport. They experimented until they found a formula that enhanced the wine’s longevity without ruining its flavour. During the grape harvest large cauldrons heated the

... Celia

Thy baths shall be the juice of July-flowers

The milk of unicorns and panther’s breath, Gather’d in bags and mixed with Cretan wines ...

... Malmsey had all but vanished from the export records by 1700. (No one recorded what happened to the unicorn milk and panther’s breath.)

IV

Someone handed me a second glass and it was gone as quickly as the first. No one wanted to be the first voice to break the glow. Then there was a grunt and a backslap as we teamed up on the last of the rows. The καλαφια were collected by the children and stacked in the cart. The men hacked off olive branches while the women gathered vine branches with broad leaves. The children levelled the grapes in the cart. The men angled the olive branches across the top of the load and the women crisscrossed the vine branches above them. Everyone hopped on, giving the grapes a pre-crush the owner didn’t seem to mind.

My eyes drifted over Crete’s countryscape like fingers over a first love. Everyone here had walked these lands till their feet hurt, found every recess and hilltop, knew the water sources trickling out of their moss dens, how the olive tree fattens from grape must to 60°C for several days. The cooked version became the export of choice due to its long storage life compared to uncooked wine from the same region. In a viticultural version of form follows function, British popular taste shifted to the sweet wines of Malvasia.

All this faded with the coming of the cork around 1600 (the same date that gave us opera). Wine tastes changed from amohora-transported and sweet to bottle-transported and dry. Despite Ben Jonson’s early clickbait in Volpone ...

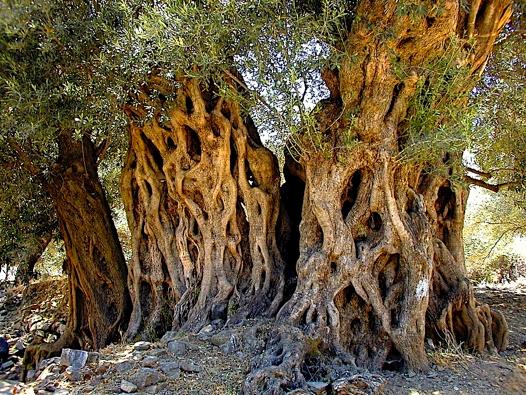

finger-thin seedling to lightning-riven old sentinel still bearing fruit in spite of its gaunt centuries.

A wrinkled face with a towering shock of white hair strangled out a tune reminiscent of a sneezing walrus. Another man unwrapped a pouch of snails he’d collected while going down the rows. He now counted them as others opined on how to properly sauté them with garlic. Two little girls marvelled over the remains of a swallow’s nest they found. A boy faced into the wind as the tractor ploog-plooged down the road. He threw a rock at a scarecrow, a dead raven that had been hung from a tree.

We descended into the afternoon sounds a Cretan hill-slope hears — hisses and rock clacks from a plow blade cutting through a fallow field. A mule balking and snorting as a farmer lurches through a tight corner. Laughs and howls and oofs and curses. Knotted caws as startled ravens tipped into the air low on their wings. Chimes from a chapel roiled over hill slopes of sheep bells. Splattery buzzes hummed out of flower cups to whirr their way back to the hive. Curt phrases swelled to screeches and back to silence as a married couple work too closely at a disagreeable task. The silvery song of shepherd’s pipes wafted in and out of the zephyrs.

Then came the sounds of the patiri πατύρι, the hamlet where local girls will tread the grapes. The map of Crete is freckled with the names of such hamlets. Duty and dwelling dot the landscape with place names and walking times till the map can bear no more. Clans prefer nearness to their fields over nearness to other clans.

Cretans still navigate landforms with names coined in Minoan times — Zakros, Praisos, Syvritos, Gournia, Malia, Knossos. On the road or along the old trails that thread chapel to chapel, each place-name is only a few dozen to a few hundred paces distant from the next. Each name has its own heritage of legend and lore, about which the further locals venture from their hamlet, the less they know.

Cretans still navigate landforms with names coined in Minoan times — Zakros, Praisos, Syvritos, Gournia, Malia, Knossos. On the road or along the old trails that thread chapel to chapel, each place-name is only a few dozen to a few hundred paces distant from the next. Each name has its own heritage of legend and lore, about which the further locals venture from their hamlet, the less they know. The spring where moss clings to stones, making them bright green. The muddy place in a gully where moles rustle between fallen chestnut leaves. The meadow of lone pines and dry grasses. The slump in the earth where a stream hisses its protest at a patch of stones. Places named after flowers, others after herbs.

Even so specific a name as a place where the herb ybright might be gathered to use for making faces fair. There is no songline significance to these; they are simply the identities of getting around.

Hamlets named by swampy groves, hamlets where stonecutters work, hamlets where itinerant ironmongers once set up their bellows on market days. Place-names for the best fields, place-names for the worst. Names for the hamlet where goat-cheese makers lived, for the crossroads where people took the left path in the spring and the right path in the fall. The churches where a single baptism anoints all the children born that year.

As I mused over these things, a plover landed nearby and left its food search in dust prints. Fingers over a first love. At the πατύρι I heard sounds of water sloshing into barrels to swell the wood into an impenetrable seal. Thin chirpy conversation rose from the sheltered bowers where the girls were patima πατιμα, treading grapes in concrete crushing basins.

The girls had hiked their skirts thigh-high and were now thigh-deep in purple. They walked slowly in a circle, executing a leftward swivel of the foot at each step to shred the skins — one of the many harvest movements that found its way into Cretan country dances today.

Someone told me that the grapes were crushed three times. The first treading yielded the sweetest juice and the lightest color. The second crush squeezed juice from the leftover mash by putting boards on it and weighting them with large stones; this yielded semisweet, more deeply coloured juice. The last squeeze saw the hamlet’s five biggest men, all brothers, hop on the boards and jump up and down, which yielded a last thick juice of dark color. Red-faced from exertion and wine and wind, the five were stocky and short-legged, hence their clan nickname, “Lowpisser.”

The skins and seeds will then be scraped into a barrel partly filled with sugar water. There it will ferment for a month into a juice which is then distilled in an antique alembic into raki.

A winemaker is an οινοποιός, oinopoiós, the root for oenologist today. The οινοποιός’s skill decides the proportion of the various wines from different fields to blend to achieve a particular taste and shelf life of wine. Wild yeast is already on the grape skins so there is no need to waste money on storebought powders. Cretan yeast is a slow fermenter that takes two months or more to finish. The οινοποιός will visit the barrels every week, put his ear to them and listen for a faint hissing. Upscale οινοποιός employ a physician’s stethoscope.

The most skilled οινοποιός have mastered the rarefied art of wedding wines. For those, especially fine grape clusters are set aside during harvest in a year when a child is born. Those few clusters will be made into a few bottles of wine to be aged until the child marries. The bottles will be opened for their wedding toast. With two or more decades of bottle time, it will be the smoothest wine they will ever taste. A popular tradition has it that the first swallow of wedding wine is as propitious as the arrival of the first swallow in spring marking the end of winter.

When the barrels are at last silent the οινοποιός performs a final φίσίμα fisima by blowing into the barrel-bottom dregs with a rubber hose to bestir a final fermentation from residual sugars in the dregs. When the barrels grow again silent the wine is done.

Hours later, after a bracing wash in a bucket by the well, I thought, “After a day like this, I know life.” Each glance around me all through the day had revealed the immensity to be had in a moment. It was at this epiphanic moment that a friend came up and nodded in the direction of the taberna, saying, “Muse all you want, but we don’t know the half of things, and never will.”

of lamb just in from the kitchen, this being the one stuffed with olive oil and rosemary.

Dinner was a din-filled, truly abandoned time. Motions, gestures, laughter, ripostes, smells, wine tumblers filled the moment they were emptied, fresh-baked bread falling apart at the knife, stubby hands, slaps on the back, full bellies patted. After an hour of this I gasped, “Enough! No more!” Then

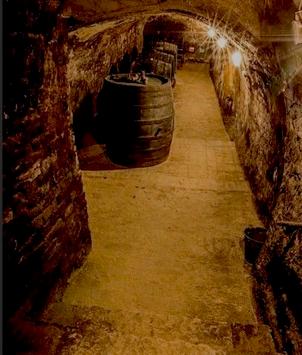

We went out into a cool night dappled with dew. The matted grass was necklaced with spiderweb funnels. The hasp on the wine-cellar door fell away. The door opened with a dull scrape. Bins and barrels appeared, dim in air thick with wine smell. Dusty barrels, speckled with mould and tiny mushrooms. Barrels with the tart, musty smell of wine that’s been in them for years. A cooper’s initials were carved into the end of a spigot. Someone dipped a wine-thief into the bung hole at the top of a barrel. It emerged streaming earth-hued droplets that turned dusky in my glass. We walked from one barrel to another, savouring not from the seductive goblets the experts extol, but plain, no-nonsense, water tumblers.

The wine was true Μαλεβύζη — brownish-red, tannic as a leatherworks, rich in the scents of the earth turned into the

ere was a moment of silence, of the marriage of taste and scent, then a thin whistle as one of them sipped in a little air, filling his palate with the wine’s musk. ’Might as well enjoy it while you can,” he said, “you go to your ghost in God’s good time no matter how much you pray.’

Slowly, taste by taste, the years receded like the aches in my bones. The light became ghostly. The details of faces diminished as they acquired a crispless mystical quality. Daytime clarity melted into edgeless shapes. Features became essences. Eyes glittered with feelings that cannot be felt in daylight. Candle flames trembled from gusts of laughter.

Laughter that drowned all the sounds that accompany mist and cold and daylong labor. Laughter, the vowel-pocked rivulets of words, the embrace of life that shouts up at Icarus, ’Hey! Why are you going? Come back! You can see everything you want with the light that you have.’

I realised I had no need to look in the mirror and say, ’Farewell, basket, the vintage is in.’

The linger of candle smell after they are snuffed out.

That was how this began.

What is the ’Real’ Crete?

Crete’s craggy geography is renowned for its mythic Minoan civilization; its tumultuous history; its hardy, feisty people. The Mediterranean Diet so beloved of nutritionists and cookbook writers may not have originated on the island, but Cretans are among its longest-lived practitioners. Travel writers ransack their vocabularies to paean the island’s rugged mountains, balmy beaches, and photo-perfect seaports. The island is a fount of print articles, podcasts, academic research papers, and wide-eyed first-timers TikToking their glee.

But what is the ‘real’ Crete?

Is it the mythical Crete, the birthplace of Zeus, the land of the Minotaur trapped and killed in the Labyrinth, or Mount Dikte, haunt of Olympian gods and mystical beasts?

That image of Crete nearly fell by the wayside as the myths faded into obscurity when archaeological facts came out. Praise be to the legions of historical novelists for puffing life into ancient balloons so they may loft again.

The Renaissance mystique of Diana the Huntress beloved of painters through the ages is a fiction that can be traced to a historical fact. The role model for Diana was no huntress with a bow and sandals, she was a Cretan villager named Diktynna (called Britomartus by Romans). Her story was so highly regarded in her own time that a shrine to her on the Rhodópou Peninsula was a popular pilgrimage from Mycenaean times to the end of the Roman Empire.

Thanks to Strabo (10.4.12) we know that the word diktyon

δίκτυον means ’net’. Instead of violently beating animals to death with sticks and spears as men did when they got hungry, Diktynna devised a net to snare them. A kri-kri mountain ibis in a wood-staked pen too tall for it to leap over soon attracts a mate, which gets in thanks to a convenient ramp on the outside. Before long Diktynna was feeding her village all year long. She bequeathed us a word so obvious that it is surprising how seldom it is used: gatheress.

Is the ‘real’ Crete the mediagenic tourist magnet fabled for its quayside cafes, memory-making balcony views over harbours, quaint towns filled with narrow lanes lined with restaurants and trinket shops? Is it the island’s fabulous hiking, deep chasms, scent of wild herbs, the jangling of sheep bells on grassy slopes? Its whitewashed chapels that dot the countryside. Its mountainous spine and cove-pocked coast?

Is the ‘real’ Crete the longest continuously inhabited island with its own unique civilization? Is it the agricultural hothouse that has provisioned the millennia with olives, honey, barley, and tomatoes ever since the first Minoan boats sailed to Egypt 3900 years ago? Is it the agricultural cornucopia of polytent hothouses that today produces a fifth of the Common Market’s vegetables? Is it the center of modern scientific research papers in astronomy, archaeology, botany, soils science, drip irrigation, geology, and fisheries management?

Is the ‘real’ Crete the iconic Minoan sevenflounced skirt that benchmarks the origin of the sewn and structured garment as we know it today? While the rest of the women around the Mediterranean made do with variations of the rectangular tent we know mainly by way of the toga, Minoan women were a parade of bouquets.

In truth, Crete is all of these. But in this recital of Crete’s civilization in fragments, there has been a key omission: the people.

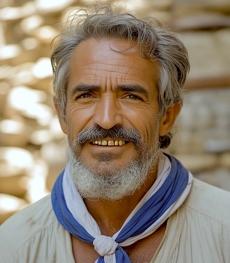

Who are the Cretan people — or as they refer to themselves, Kritis? What do they do all day long? What are their jobs, their pastimes, their worries, their rules for good living? How do they raise their children? What do they think about each other, the mainland Greeks, the hoards of summer tourists, their futures in an era fraught with the environmental omens of rising sea levels and tinderbox wildfires?

There is a predictable generation gap between Zorba the Greek and today’s young professionals who shun the mythic Crete in favor of advanced degrees in Athens and abroad. But while those young people are serving “Real Cretan Food” in touristtrap cafes as they earn the money for next semester at school, what do they really think about you?

The panoply herein makes for entertaining reading, but it is a pallid facsimile of everyday life — the smells, the sights, the fleeting facial expressions that unmask inner thoughts, how children play, how elders walk, how Cretans manage to enjoy themselves despite life around them changing too quickly and too much.

Go there and spend three months talking to everyone you can. People in blogs aren’t nearly as interesting as the ones sitting next to you.

You won’t know until you ask.

Honey Moon Room

I found the flat of my hopes in an old Venetian building in the yesteryear Topanas Quarter. The two-floor flat was above a gift shop owned by a charming, plumpish woman named Maria. The sign on the street billed it as ‘Room Honey Moon.’ The notion of a bachelor renting a flat with that appellation conjured an image of arriving alone with a backpack at an inn in the Cotswolds and asking for the bridal suite.

Maria confided that a writer residing there for three months would bring in many more euros than newlyweds who stay three days. The building was a wedding gift to Maria and her husband Tassos. They passed their honeymoon and most of their marriage there. They raised their two boys in the building, then moved to the suburbs when the boys were early teens who needed private rooms of their own.

Maria offered to take down the sign if I wished I said, 'No, I’ll have a honeymoon with Xania.' She beamed. The rental was off to a good start.

The flat’s upper balcony looked down on Odos Zambeliou or ‘Street to the Spring.’ It is a threadneedle lane that wriggles its way downhill to Chalidon Square. The fourteenth and fifteenth century Venetian traders who built townhouses along the lane platted them with just enough width to accommodate oxdrawn delivery carts — the only way to transport cumbersome building materials and furnishings in those days.

Below my balcony and to the right a broad street named Odos Domeniko Theotokópolous descended half a kilometre to the sea.

Theotokópolous was the patronymic of the sixteenth century painter El Greco. He was not born in Xania, nor did he ever live there. His Venetian colonial parents were driven from Xania in a Cretan rebellion between 1526 and 1528. He arrived on Earth in 1541 and eventually found his way to Spain in 1577.

That doesn’t stop AirB&B agents with rentals on Odos Theotokópolous from

claiming ’El Greco slept here’ in their online pitches. By their claims, dear Domeniko slept in more beds than Napoleon.

Stroll down to the sea on this street and the colours of the buildings resemble those you see in El Greco’s early paintings. Squint your eyes and you can easily imagine you are walking around and meet him with an easel in his hand.

My days began with Xaniá’s love affair with bells. Every quarterhour sounded like a competition between March of the Marionettes and a union protest at an iron works.

Despite these tintinnabular exhortations, morning-time Xaniá bestirred itself slowly. The only predawn sounds were the swifts skreeking their arcs across the sky and the cats in yet another yowly territorial dispute. At eight a.m. the streets below were all but empty despite the boisterous sun. Here, an old woman carried a rustling basket of breads. There, a boy trudged his way to school, book pack strapped to his shoulders, his oversize sports shoes going galumph, galumph. A few minutes later some imbecile braaaaked by on an unmuffled Vespa. A rooster skrawked.

Once a week Xaniá’s sole remaining καράκλας karáklas man hollered his raucous rounds as he advertised his armload of fresh-cut rushes gathered before dawn from a swampy spot in the Klathissos River on the western edge of the city. Yioryio by name, he repaired brooms and wicker chairs. As the Topanas Quarter is the ritzier side of town, he started at our end where his rushes would be the freshest.

The empty balconies that greeted him suggested that forbearance is part of the karáklas job description.

Myriads of wash lines on the balconies and roofs fluttered in the morning. The breezes that came with the heat of afternoon would have them rippling like pennants on a yacht. But now, still dripping, they smelled redolently of olive oil and rosemary.

Olive oil soap is ubiquitous and inexpensive in shops and open-air markets. A mother can dab a baby’s face with this soap. A workman can lather off the grime of a plumbing repair. A laundress can swizzle silks and cottons in the same water.

Elegant upmarket olive soaps come prettily wrapped in marbled paper that looks like the endpapers of an antique book, yet the soaps are humbly priced at about a Euro.

This soap, wrapped gifty or plain, is an example of how Xaniá refuses to let itself be institutionalised despite the spending hoards that throng through every summer. Starbucks has an outpost on Chalidon Square, but a discerning ear hears no Greek. Seattle’s cutesy concoctions may dazzle the TikTok chatterboxes, but they don’t cut much ice with Cretan palates fine-tuned on four centuries of cafe élleniko thick enough to float a spoon.

When I wanted bread I would stop by Yorgos’s αρτοποιείο, bakery, hail out a ’Yasas’ and choose from an assortment of ψωμί psomi (breads, and be sure to aspirate both the ’p’ and the ’s’) still hot and yeasty from the oven. No industrial additives besmirch Yorgos’s psomi, nosiree. I watched him work from one till ten in the morning through every step of the αρτοποιός

(artopoiós psomioú) art, from scooping flour from a cardboard barrel to pulling crackling loaves out of the oven with a flat wooden paddle.

Armonia Keramika’s day commenced when Maria’s wind chimes were hung up to announce the event, to the accompaniment of the cats Capuleting and Montaguing over the newly altered territorial claims mandated by the shop doors having been opened.

On day Maria called me down to present me with a psomi. It was about eight inches in diameter, an inch or so thick, and made mostly of barley flour (as is quite a bit of Kriti bread). Dozens of olives had been pressed into the dough before baking.

She had purchased it from Yorgos, one of the last traditional bakers left in Xaniá. His oven dated from the fifteenth century. It was a wood-fired affair that looked like a vision of Hades by Hieronymous Bosch as filtered through the wit of Walt Disney’s 1930s-era animators.

Whenever I stood in his shop perspiring profusely in the hot Mediterranean morning, the volcanic heat radiating into the room made me think that before my very eyes lay the door to perdition.

But if this was perdition, what came out of it was paradise. His fresh loaves yeastily advertised themselves on the shelf. A dozen mottled browns would waft their sourdough smells like morning mist off a pond. Nut-brown crusts were coated with oatmeal on the top and almond dust on the bottom before baking. The almond dust was to keep the loaves from sticking to the oven when they first went in. Plain round buns were a fragrant brown.

Back in my second-floor kitchen with the loaf Maria brought, I didn’t quite know what I was supposed to do with this psomi from the heavens. I called to Maria downstairs in her shop. She tromped up the stairs, broke the bread into chunks on a wooden platter, crumbled a layer of feta over them, drizzled olive oil over that, anointed the whole affair with fresh oregano and basil from the planter boxes just out the windows, and pronounced, ‘Πόλη εύηευστο.’ Poli eviefsto — very tasty. That was the understatement of the day. The loaf was embedded with slivers of sun-dried tomato to add piquancy to the olives baked into the crust. The loaf inside was freckled with marjoram. It crackled fragrantly as I munched chunks of it dipped in Ηλίας Λάδα, ilias lada, olive oil.

I had bought the ilias lada directly from a barrel at the Mom & Pop shop just across from Yorgos’s bakery. The same shop sold home-made (and probably home-stomped) Cretan wine, also directly from the barrel. From what I’d seen of it, one sip would stain your teeth for life.

The only thing missing from Maria’s psomi feast was a chunk of γραβιέρα graviéra cheese, the local gruyere-style cheese that’s the best bread-extender the Cretans have come up with.

I wrote graviéra on my shopping list. Plus tomatoes, so fresh and scented they all but leap out of the bin into your basket. Plus capers. Plus several kinds of olives. Plus a slab of feta.

Plus oranges for dessert, to be peeled the way Kriti children love to peel oranges in lunchtime contests, strung out in as long an unbroken strip as they can.

Morning Mundanities on Odos Zambeliou

Odos Zambeliou, Οδός Ζαμπελίου, is one of the main routes that navigate the labyrinthine Topanas quarter. Today it is paved with cobbles of granite, a vast improvement over the miry rutways urban streets were for centuries. Even today a few of the old palaces have mud scrapers at the side of the door to demuck one’s boots.

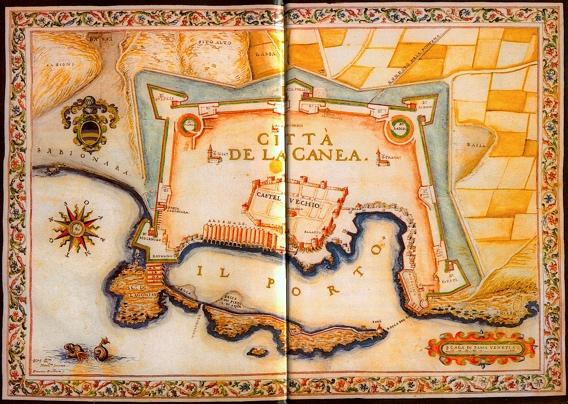

The Topanas Τοπανάς was the wealthy merchant district in Chania’s Venetian heyday from the middle of the thirteenth century until the Turks overran the city in 1645. Odos Zambeliou marked the boundary that separated the worry-free wealthy from the wannabe wealthy. The arched portal leading out of town to the left of my balcony dates from the 1400s.

So quiet was the quarter that I would awaken to silence. The first arrival of the day was the newspaper deliverer. She was a stout girl of maybe fifteen to eighteen. In the cool mornings she wore enough jackets atop jerseys to look like a blue serge bowling ball. The papers were pathetically skimpy little things; the ad base must have been atrocious. She rolled them into tubes stuffed like cinnamon sticks into a sheet metal box on the back of her Vespa. The whole affair looked like it would tip over backwards the moment a gear was engaged.

Then silence again until Chania bestirred itself in earnest around 8:30.

Most Topanas buildings are narrow, varicoloured, tri-floor Venetian townhouses, soft-textured and soft-hued with a cramped floor plan that makes one think of life in a telephone booth.

Interiors are gloomy with featureless. Shadowless light. Steep stairs. Balconies barely wide enough to accommodate a table and two chairs. They are childproofed with large flower pots out the windows too big for a toddler to climb over.

The Old Harbour ended in the Mediterranean on the north and merged into the Splantzia or Turkish quarter to the east.

To the northeast was Kastelli, a jutting outcrop with a sweeping vista of the sea, atop which Chania’s 8,000 years of continuous civilisation began.

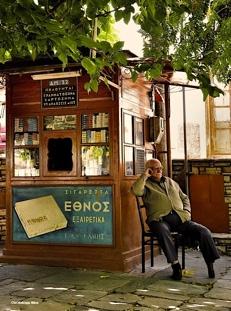

Xaniá Old Town is a warren of alley-like streets merging into tiny little plazas with newspaper/cigarette/chewing gum/ lotto-ticket kiosks surrounded by townhouses. Descriptiondefying tints of pastel. Windweathered windows with cats sleeping on the sills. Flower pots frothing bougainvillea, stavesacre, geraniums.

Soft mottled surfaces. Cats hissing at each other. Lemon trees. Gnarled vines trellised into overhead sunshades. Cobblestone lanes so narrow outstretched arms touch both walls.

Elderly widows dressed in black. Cats doing nothing in particular. Mandolin music drifting from second-floor windows Cylindrical chimneys venting wood-fired ovens. Oranges on window sills. Scents of fresh bread. Balcony clotheslines dripping onto cobbles.

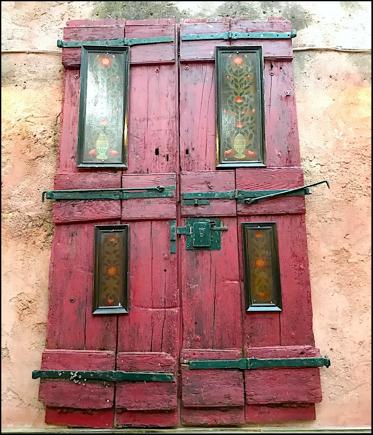

Dwelling doors of Cretan blue and marigold ochre.

Bicycles lain against walls. Thick impastos of whitewash. Children screeching to the sound of a bouncing ball. Dignified old gents who acknowledge a 'Yasou' with lips as compressed as the Sphinx.

And still more, **sigh**, cats.

Unsurprisingly, Crete’s most ubiquitous postcard theme is cats. If you want to see visiting coffee-table book editors roll their eyes and grimace, propose 'Cretan Cats.'

On the other hand, given all this battle-honed claw power, I never saw a dog loose from a lead.

Today a group of workers showed up at the unearthly hour of 8:00 to make a show of progress on a seemingly endless cobblestone repair on the street below. Now it was 8:15 in the morning. The workers below were half tapping and half arguing into place the myriad cobblestones of a re-paving job that had been going on since I arrived. The fruits thus far were about twenty metres of the left half of Odos Zambeliou looking like a proper street.

It was hard to tell if what lay below me was one supervisor and four workers or four supervisors and one worker. Every stone had to be emplaced with as much discussion as possible.

Today one of the Zambeliou dwellers abruptly interrupted the discussion with a grumpy cantata of shout-filled, handwaving, finger-pointing locutions so staccato they sounded like a bankruptcy auctioneer on fast forward. Why did these workers insist on waking up all Xaniá by discoursing and taptap-tapping thus at the unholy hour of 8:15 in the morning, and on a Tuesday at that? Hadn’t they ever heard of rubber hammers in their profession? Bricklayers use them all the time.

The gentleman applied a truly munificent eloquence to so brief a point.

Naturally, all work halted. The nearby balconies lined with housewives and children in a display of civic solidarity on the side of their neighbour.

The discussion ended with the workers agreeing to tap more humbly until the time to break for lunch, followed by the union-mandated nap through the hottest part of the day and a wine-sluggish return to work about five.

Have you ever wondered why medieval towns took so many centuries to build?

II

The Room Honey Moon was at the far western or 'high' end of Odos Zambeliou. Beyond it the Odos abruptly tee-boned into the Cavalierotto Santa Catherina Bastion. Below and to the left was a splendid wall of blue morning glories surrounding a former merchant palace.

It was inhabited by a reclusive widow in her eighties living out her dwindledown days being attended to by a daughter who had opted for filial duty over uxorial bliss. Every morning she brought a hamper of prepared meals. Every evening she took away the dishes.

The Santa Catherina portal didn’t exit the town any more.

The Bastion’s fourteenth- and fifteenth-century exoburgi farmer’s market declined in the sixteenth century as the Venetians took stock of Turkish intentions in the eastern Mediterranean and decided this would be a good time to prepare for the probable. Today the portal leads to the massive fortress walls the Venetians built to fend off the Turks.

Build they did. A fortress two miles in circumference embraces Xaniá Old Town, roughly twenty metres wide across the parapet and fifteen metres straight down to the now-empty moat — today dotted with modest little onion and artichoke patches tended by citizens who pay a small fee to rent their plot. In Crete, there is an adage to the effect of, 'You can take the family out of the farm, but you can’t take the farm out the family.’

The Venetians did not think petite. Their mindset evidenced itself eloquently in the massiveness of the old fortress walls. Think of them as living with a huge bedmate in a small bed.

The Venetians built them brick by brick using local peasant labor extracted at sword point from Crete’s interior mountain villages, even if it meant their crops would rot.

The phrase 'brick by brick' doesn’t convey any sense of what it must have been like working in one of those press gangs. Pretty as the Topanas quarter may be, it was built by wealth accumulated

by exploiting inland Cretans the same way Caribbean slaverunners maltreated their chattel of Africans.

'Brick by brick' can’t hint at the dust that would have been always in the air. The pipestem legs of gruel-fed men. The knee-high mud when it rained. The flyblown donkey piles in the road. The yells of the workers when someone got hurt. The squalid rat-squirming reed shacks in which the wives and children alternately seared and froze during the year. The smells of cooking fires at night. The children tapping oxen along with sticks while staying warily clear of the lurching, yawing wagons sagging from bricks or broken limestone to fill in the wall’s surface made flat enough to trundle cannon wherever it was needed.

Those words don’t convey that the surveyor’s technique for levelling the tops of the embankments was to sightline along two pots of water with a string stretched between them. Or that the clay sealing layer that topped the fill was simultaneously compacted and made flat by driving herds of sheep or goats along it for days on end — a technique that has been passed almost without alteration into our own time in the form of water-filled cylindrical earth tampers used in highway construction whose outside surface is dozens of steel knobs which compact and smooth the soil the same way the sheep did, and is called a sheepsfoot roller for that reason.

Much of the rampart is now broken down. Turkish cannon started it. Modern merchants continued it. Gates were removed to accommodate autos that are wider than farm carts. In the early 1900s the thrifty civic fathers flattened the Piatta Forma and used the brick to make a large square on which they built a proud new agora public market. History evolves from market to market. War and revolt reset the prices.

Clippety Clop

The fabled clickety-clack of railway travel now having vanished into the linear screech of welded ribbon-rail, one of the few surviving rhythms of pre-petrol conveyance is the clippety-clop of six horse-drawn carriages in Xaniá.

Every afternoon and evening the plaza around Chalidon Fountain and Karaoli ke Dimitriou ring with the clippety-clop of iron horseshoes on stone cobbles. Yet another tourist family or swain courting a girl are enjoying the ride of their lifetime. The image library of Xaniá’s dictionary is too diverse to distill into a few pages, or perhaps even a book. But at least one page must be devoted to carriage rides and the horses that propel them.

The carriages arrive around eleven in the morning. Six teams are especially trained and licensed to act as public conveyances at hire. No budget-aware Xaniote would pay the multi-euro fee for a perambulation through the Old Town’s back lanes. They walk those lanes every day.

Carriage rides proceed at a pace so leisurely they invert the Tortoise and Hare story. The Tortoise is the carriage and the Hare is any local resident who wants to get where he or she wishes in as little time as possible. In the Xaniote variant of the tale, the Hare easily laps the Tortoise four or five times before the Tortoise returns to its starting post.

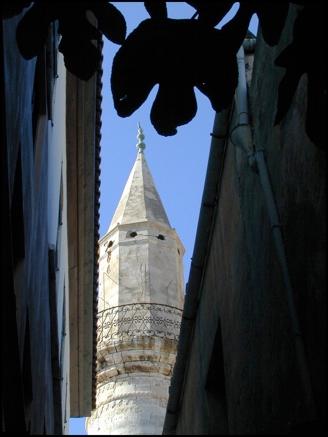

Xaniá’s carriage-ride parking lot is exotic even for Crete. It is located between Akti Tombazi that edges the eastern jetty and Masjid Kücük Hassan — the Mosque of the Janissaries — the harbour’s comeliest piece of architecture.

The horse-and-carriage teams arrive from their owners’ stables out on the southern edge of go-go-go modern Xaniá — which is indistinguishable from any other Greek city given urban Greece’s unfortunate architecture, worse traffic, and residents who wouldn’t be caught dead taking a tourist-trap carriage ride for the fun of it.

On the other hand, a carriage ride through Xaniá Old Town is a FUN tourist trap. So is Disneyland — but in Xaniá you don’t have to wait hours in line for five-minute ride that one endures in Disneyland.

Kitschy or not, the clippety-clop carriage rides are among Old Town’s busiest attractions. At any time between noon and seven in the evening you can be strolling the harbour esplanade (avoiding the phalanx of cafe touts as you would a phalanx of lances), all the while admiring the water-hued pastels of Xaniá’s Venetian architecture. Suddenly before you looms a line of six gaily painted carriages with riders holding their horses’ bridles, huge spidery wheels, bench seats that can accommodate a family of four. Given the quality of the grooming, the owners devote as much time to their curry combs as they devote to banking the Euros they bring in.

One horse is a palomino, two others are chestnut roans with tâches (white patches) between their eyes. Another is an aging grisaille dowager, still beautiful and still reliable but clearly in line for pasture.

The eye-popper of the lot is a jet-black bucephalus of pure muscle with the chunky forelegs and pyramidal hooves of the Shire breed in England or Clydesdales in Scotland. His forelegs are tree trunks of hair bred to plough the loamy mud of tidal flats in northern England and the polders of Holland and Belgium. Those muds are thick, gooey, and deep. The lithe legs of thoroughbreds would sink to their bellies in the stuff.

This particular horse is a model of the well-groomed steed. His owner must spend hours on the plaited mane and a tail whose braid reaches his fetlocks. Any horse lover would swoon at the beauty — a reaction seen in every child who pats his nose and begs to sit on his back.

The carriage owner explains for the umpteenth time that all riders must be seated in the carriage. Whatever budget-aware parents might have planned with their cellphone calculators in the morning, guess who ends up in the carriage seat blowing the daily budget to smithereens?

The route taken by these carriages rounds the Chalidon fountain to pass eastward along Karaoli ke Dimitriou.

One becomes an eardrum expert on the demographics of the carriage trade in Xania. They pass so close that passersby might as well be security cameras recording the expressions on their faces as Germanic bottoms try to fit into seats made for Cretan ten-year-olds, while leggy Nordics hug their knees to chests. The loveliest memory of all is the ring of iron shoes on cobbled stone.

It’s not Chania: it’s Χανιά

Why does the Χανιά Old Town look more like Italy than Crete?

From 1285 to 1639 Χανιά’s ladle-shaped harbour was a major Venetian port. Cretan labor built the harbour; Venetian commerce sent home the wealth it created. The Venetian model of subjugating a distant populace to prosper a populace at home initiated waves of wealth for a few at the cost of poverty for a multitude, a dissonance that still roil the theories of prosperity today.

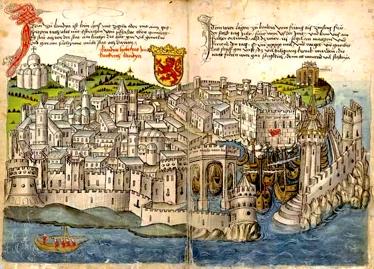

Venice converted Crete from a bucolic backwater into a bulwark whose stone-hard esplanades and arsenals smoothed into the eye-candy strolls of today. The island’s two main harbours Χανιά and Κάντια (Candia, today’s Heraklion) were the foci of an ellipse that looped Byzantine Constantinople in the Northeast, Antioch and Acre in the the Levant, Alexandria in Egypt, Andaluciá in Spain, Barcelona in Catalonia, Marseille in Provence, and Genoa/Pisa. Trade within that ellipse amassed enough wealth to raise Venice from a soggy cluster of islets to promulgating the mandates of Mediterranean power.

Many lines of type have been set to opine the consequences, and many eyelids have drooped amid the volumes of conclusions. The Xaniá Town News sees its namesake city as a centuries-old art gallery filled with timeless people gazing into the mirror of changing times.

Constantinople

For a millennium Constantinople was the largest trade entrepôt in the eastern Mediterranean and the largest religious entrepôt of Byzantine Orthodoxy.

During the era of Xaniá’s rise, Constantinople was starting to wilt. Trade and Turks were coequal predators. To the Venetian patricians, the city’s greatest asset was its trade links to Samarkand, a forty-day caravan journey to the east.

But Samarkand, too, was in decline. A merchant city built on the markups of the Silk Routes trade, Samarkand was the western terminus of a webwork of roads serving Sogdia, Bactria, Kushan, Persia, Gandhara, India, Tibet, China. A romantic litany that was unromantic to live in.

Samarkand survived as a terminus of southerly trade to Persia and northerly to Rus and the Viking-controlled Baltic lands. The Vikings surprised everyone by shifting from predators to profiteers when it dawned on them that predating Irish and French priories was small change compared with the wealth to be had from schmoozing Samarkand sultans.

Constantinople’s lifeline to India and China declined to extinction in the 1400s as Central Asia was overrun by Mongols. Silk Road caravans were outflanked by the more hazardous but more profitable Silk Sea ships, which debarked not in Constantinople but Alexandria to the south. Constantinople had also seen two vital manufactures slip from its grasp: silk weaving and paper making. When Samarkand wilted, Constantinople withered.

In 1453 the Turks overran the city. They looted its wealth but left its merchants alone. Even uncouth heathens know who replenishes the money they loot. Venetian traders saw 1453 as a hiccough. Xaniá barely noticed.

Constantinople’s most calamitous loss was not its trade capital, but the loss of its intellectual capital. Nearly every significant work of thought and art produced by ancient Greece survived in original documents in the monasteries and libraries of Byzantium. The works of philosophy and mathematics known to northern Europe between the time of Cluny to Aquinas were Arabic translations from Greek produced during the great Beyt-al-Hikma era of Muslim scholarship in Baghdad. From Greek to Arabic in Damascus and thence from Arabic into Latin in Andaluciá, Aristotle and Plato might just as well been debating in Cordoba.

Greek scholars in Constantinople could read doom on the horizon as clearly as they could read glyphs on parchment. They fled west with donkey loads of scrolls. They bequeathed the Renaissance an intellectual heft that reinforced the arts after the mathematics of perspective were formulated.

An eighth century silver dinar found in the Viking Vale of York hoard in Durham, England bears the mint mark of Sultan Isma'il I (892-907) — an eloquent glint from the Volga-trade wealth. Courtesy of the York Museums Trust.

Levant

Crete’s central trade arc sailed to the Levant of Antioch and Acre. History ladles out a more piquant tale than the pieties ladled out by Saint Paul.

Knights in iron led by princes in peacock feathers had the Levantine wool pulled over their eyes so adroitly that the reliquaries of European chapels boasted enough bits of weathered wood for three True Crosses and enough glass phials of Mary’s Milk to nourish entire orphanages. That Mary’s milk didn’t spoil was taken as a miracle. Mary’s Milk is a colloid of water, glycerine, and powdered white dolomite from the Sitti Mariam grotto a few minutes’ walk from Bethlehem.

The disciples of Galilee fished for souls. The merchants of Jerusalem fished for suckers. Crete welcomed them both.

Alexandria

To the south, Egypt had been a trade destination since the time of Minoan Knossos. Minoan drinking vessels buried during the catastrophic earthquakes and Mycenaean invasion of the island emulate those depicted in Egyptian palace frescoes painted centuries earlier. Two thousand years later the Silk Sea trade route from Guangzhou to Cochin to Aden to Alexandria replaced the overland route.

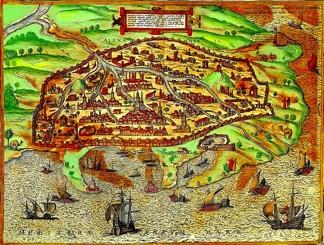

Alexandria in Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Braun & Hogenberg 1572. In eastern Mediterranean seas Venetian mariners in their billowy three-masted vessels would have been easily distinguished from angular dhoni-rigged Levantine vessels. Vessels with both sails and serried ranks of oars were preferred by pirates because they could make headway directly into the wind.

Over the centuries a stony shoal on the north side of the harbour was gradually walled off from the sea with thick wavedefeating ramparts save for a narrow access channel dredged to a navigable depth on the western end. The landmark lighthouse which signals the harbour entrance is a glory of seventeenth century maritime architecture, refurbished in he mid 2010s to is ancient glory.

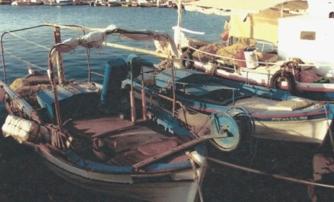

Today the bustle of Χανιά’s Arsenale repair depot and ship chandlery have dwindled to sailing vessels winched out of the water onto trunnions for a barnacle scrape and new coat of paint. The bristling warships have been replaced by grandiose yachts and a contingent of local fishers whose sword against the sea is a boat roughly the size of a compact car with a prow and stern attached.

The water is lucidly clear and trash-free. Fishing boats appear to levitate above a bottom so clear one can see fish darting insouciantly between the fish hooks and anchor chains. Stone bulwarks rise about four feet above the tide line to an esplanade of large rectangular slabs.

These slabs are living history, trodden smooth by galleyslave agony in one century, sweating shipbuilders the next, entrepôt merchants the century after that, and volta promeneurs today. The walkway is about twenty meters wide, lined with dozens of street cafes and restaurants featuring downscale cuisine at upscale prices. Occasionally the dishes are indeed ’real Cretan’.

The tables are shielded by awnings which are rolled back in the evening to reveal magnificent moonscapes over the harbour. Inside, these eateries are furnished with bamboo and wicker chairs, tasseled cushions, glass-top or cloth covered tables, fresh cut flowers, and in the evenings, battery operated LEDs that flicker like the candles. The different premises are bordered off from each other with potted palms, ficuses, bamboo screens, and mutual disinterest.

I soon settled on a convenient scribbling spot, the Kyma Cafe, Κύμα Καφενείο. The name Κύμα meant ‘wave’. The reason for such an anodyne name is Cretan shrewdness. The Greek tax authorities have keen noses for the whiff of undisclosed gain. Chaniote Χανιώτη cafe owners deodorise their balance sheets with a rose-water of changing identities and bookkeeping so intricate that it is referred to as the Triantáfyllo system. Τριαντάφυλλο is the Greek word for ’rose’, literally ’thirty petals’. The term describes the layers concealing an average cafe’s true recipients of false profit-and-loss statements.

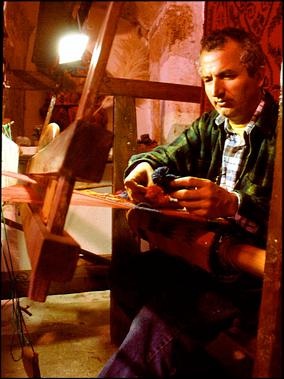

The Κύμα was on the west side of the harbour, out of the sunset’s glare. It was secluded enough to work without being disturbed, yet gave a full view of the arc of the harbour. Directly across the water was the town’s architectural piece de resistance, the Mosque of the Janissaries — more accurately but less elegantly known as the Masjid Küçük Hasan. This lovely shaped but unlovely named mosque has been gentrified into an exhibition centre for Cretan crafts. Exhibitions change biweekly. Cretan domestic and trade crafts are so true to the soul of the land they are worth a three-week layover just to appreciate how deeply creative vitality runs on this island.

The original model for this modern edition of a Minoan-era Snake Goddess might have been worn as a brooch, a garment clasp, or the pendant on a necklace. The double-tiered headdress, oversized gold earrings, and Egyptoglyphic foot stance all point to deified womanhood. The symmetry of large masses around a central column suggests the quasi-mystical labrys or double-headed axe. The central figure would be the Mother Goddess, reinforcing the Minoan validation of feminine wisdom as true power. The geese symbolise marital fidelity, since geese were thought to mate for life. The four snakes represent life, death, nature, and rebirth.The three winged creatures at the knees represent bees, whose honey and wax were key calorie sources in daily life. Bees were also thought of as exemplars of mutual dependency and social support. A society that lived close to nature’s processes, Minoan ornamental art depicts animals and insects as being on par with and inextricably linked to human welfare. It is noteworthy that such this potent goddess associates with animals, not other humans.

Upper face of a Minoan-era gold ring in the Athens Archeological Museum. The significance of the scene is speculative. One interpretation is four emissaries from the nether world disguised by animal masks are presenting ritual obeisance gifts

Fanfare for the Common Cafe

Chania’s Old Harbour is history in a bell jar — a fifteenth through seventeenth century Venetian colonial outpost that in its heyday comprised a commercial entrepôt in the west harbour and ship repair facility to the east. The north side is a long sea wall with thick wave-defeating ramparts adorned with a recently refurbished lighthouse at the end.

A sea lane to open water lies between the lighthouse and the Firkas Fortress to the west.

The harbourmaster has the daunting task of accommodating both grandiose yachts and a contingent of local fishers whose sword against the sea is a boat the size of a compact car with a prow and stern attached.

The ancient stocks and hangman gibbets which enforced morals when political appointees ruled the roost have been replaced by rubbish bins for plastic, glass, and paper.

The western, touristy part of the harbour is about the size of a small college campus. The quays are a droplet-shaped semicircle of stone ramparts rising about a metre above the tide line.

These stones are a pedestrial history text, trodden smooth by galley-slave agony in one century, sweating deckhand labourers the next, merchant wagons the century after that, and global flâneurs today.

The promenade is about twenty metres wide, lined with dozens of cafes and restaurants featuring mainly taberna dishes at Cordon Bleu prices.

The restaurants are shielded by broad-striped canvas awnings that are rolled back in the evening to reveal magnificent moonscapes over the harbour. They are furnished with bamboo and wicker chairs, fluffy cushions, glass-top or linen-covered tables, fresh flowers, and oil lamps in the evenings. The different premises are bordered off from each other with potted palms, ficuses, bamboo screens.

I soon settled on a convenient scribbling spot, the Κύμα Καφενείο (Wave Cafe). Quayside Καφενείον regularly change names as aspiring newbies try their hand at milking tourist Euros. On subsequent visits my old haunt changed its name and staff three times over twenty years, though the

interior decor and kitchen and bar were as familiar as ever. I was never able trace down the staff I had come to know while jotting my first notes there.

The Κύμα Καφενείο was on the west side of the harbour, out of the afternoon sunset’s glare. It was secluded enough to write in obscurity behind potted plants, yet open enough to fully embrace the nonstop parade.

Directly across the lagoon lay the town’s architectural piece de resistance, the Kücük Hasan Masjid — also known with less élan as the Yali-Tzamisi Mosque. Local lovers of euphony call it the Mosque of the Janissaries.

This lovely-named but unlovely-shaped masjid is now a municipal art gallery focused on Cretan culture. The frequent exhibitions of children’s art from local schools are the best introduction to Crete’s future that a free admission can buy. The mosque’s mammiliform domes contrast with the fussy, vertiginous Venetian architecture of the rest of the waterfront. The buildings are painted in Italianate pastels of ochre and blue and pale yellow, with Grecian-blue wooden window frames and lacy curtains wafting in and out in the breezes.

These buildings are four hundred to six hundred years old and show it. There is a sweet dilapitude to their facades, a dowager-past-her-prime look made all the more charming by no two buildings being repainted in the same decade and shapes that were not quite square even when new.

The cafes and restaurants have ’house’ music that tries to make up for their absence of distinguished decor. The

specialised in Cretan love songs. That attracted a clientele that convinced me to make it my home.

During the morning shift at the Κύμα, three people were on board: co-proprietors Teodos and Iannis, plus Teodos’s amour Anna in the kitchen. Another Anna, dubbed II, relieved Anna I at around 4:00 so she could take care of her baby.

Anna II was the Κύμα’s premier confectionist. While Anna I was slim as a toothpick, willowy, and walked as though she had been a zephyr in a former existence, Anna II was well weighted towards the middle, dark-eyed, dusky, and moved like a dowager in search of lost youth.

Iannis generally came in around 6:30 a.m. and worked till 4:00 p.m. He then took three hours off and came back till the

last customer went home. Teodos turned up at about 11:00 a.m. and worked straight through till midnight. Except for an occasional backgammon match with one of the harbourside regulars, neither had more than a few minutes off their feet at any time during the day.

The two Annas fared little better, except that they divided the day more evenly so Anna I could turn the back rows of the Κύμα into an impromptu day-care center from four to seven in the afternoon. Other cafe mothers knew about the Κύμα’s Moppet Welcome Mat and by five p.m. the place looked like Naptime in Totland.

Iannis

I soon befriended one of the owners, a man in his early thirties named Iannis. He was at the career stage where the magnet of serving tables for the rest of his life repulsed more than it attracted. His income was at the level where marriage was out, a permanent home was impossible, and — the ebb and surge of the Mediterranean cafe-economy being what it is — even a fixed country was out.

After a few days of repeat visits, he brought me the customary gratuity of a thimble glass of raki along with the bill. I declined, mentioning that I don’t drink.

'That’s a rarity in a place like Xaniá,' he replied. 'Many tourists come for the express purpose of getting commode-hugging drunk where the neighbours won’t see.’

’I’m a writer. If I don’t have clarity, I don’t have a job.'

He confided, 'To tell you the truth, I don’t drink, either.’

'Now it’s my turn for the Why?'

customers. After a few years they owned their own cafe. I asked myself what they had that I didn’t. Truth is hard to face.'

'Wish wears a thousand masks, and denial can find a thousand excuses. Add them together and you’ve got the gods.'

'When I first got into the cafe business, I saw people like me who became very successful. They started like me serving

’You’re telling that to a Greek? We have been at it thirty-five-hundred years.’

We were interrupted by the approach of a Roma woman in an old-fashioned handpropelled wheelchair. She was dressed in black. A black scarf covered her hair. I had noticed her a few times before as she made the rounds of the cafe tables. I admired how adroitly the woman manoeuvred the wheelchair with one hand while proffering cello-wrap packets of hand tissues with the other.

A handful of customers occupied the tables facing the quay, sipping tall glasses of iced cappuccino.

The customers pretended she did not exist. Her face implacable granite, she wheeled to the next cafe.

I watched her progress to the end of Restaurant Row. She gleaned many avoided glances but no sales. As she returned

to circuit the quay in the other direction, I stepped forward and bought five packets. She tucked the bank note into her sleeve, said nothing, wheeled on.

Iannis was watching.

‘You just bought more tissues than she sells all day,’ he informed me.

’How many is that?’

’I asked her one time,’ Iannis replied. ’She held up four fingers. She is not allowed to speak with a gadjo male.’

‘Why does she do it?’

‘She’s not there to sell tissues. She’s there to keep her eye on the chaj, the unmarried girls who sell those glittery balloons and long-stemmed roses. ’They work in pairs. An unmarried Romani must never be out of the sight of a married Romani. Next time you are on a stroll, pass the back lane behind the Mosque. She holds court with the Romani balloon and rose sellers there when she’s not selling tissue packets. She’s the Matroana, the matriarch of the Roma clan that lives in windowless delivery trucks that park near the Sabbionara Bastion. The young girls who sell the balloons and roses hand their money to her after each round of the quay. She feeds them packet meals wrapped in newspaper. She is as truculent

with them as with you. I have never seen any of them smile. Around ten at night their phrals, the word for “brothers,” come along, take their money, and escort them back to their trucks for the night.’

’I strolled past one of those trucks last week. The back doors were open, The interior was lined with carpets, including the walls. The only furnishings were cushions and sleeping mats.’

’The girls start off with ten roses or balloons in the morning. They have to give their fathers ten Euros when they go home. Count the roses or balloons and you know how their day is going. The average Roma family has ten members and earns about six thousand Euros a year. That’s what Teodos and I pay to rent this cafe for a month.’

’Their language is an archaic form of Hindi.’

’So is their culture. Fathers set the rules of patriarchy, but mothers do the enforcing. A girl’s husband is chosen for her by the time she is eleven.’

A saxophone solo shimmered from across the harbour, sounding like Branford Marsalis at the bottom of Atlantis.

The water was like trembling glass. Tables were littered with empty beer bottles and pistachio shells. A teenboy’s arm draped over a teengirl’s shoulder as her arm clasped his waist. A mountainous carton of popcorn led around a tot.

’Iannis, if you are not a natural businessman at heart, what are you?’

He was silent a long time, then said, ‘I wish I knew. Running a cafe is all I know. It takes so much time and money, I can’t be anything else.’

A portly foursome stopped before the menu on the quay. Dowagerish and ample, the two women wore long dark skirts and their men wore white office shirts. They would spend quite a bit wherever they lighted. With thirty other cafes competing for every appetite and thirst, timing was critical.

Iannis scooted over them and began his pitch — in German.

Mystery Boat

I went back to jotting notes. The dumpiest fishing boat I have ever seen was easing away from the quay in front of the kaphenion next to the Κύμα. This kaphenion had the look of a tourist trap putting on airs of minor mob connections, so it was hardly surprising to see this piece of motorised flotsam in front of it. Lacquered brass and teak it was not. The hull paint could have been vastly improved by any five-year-old. The gunnels were weather-beaten poles weighed down with yellow fish net. There was a canvas sunshade over the afterdeck lashed to angle iron so rusty it looked like just after the explosion in an action movie. There was a loudspeaker lashed to the mast,

a couple of red jerrycans for fuel on the quay, a rudder held together by the type of stamped metal hinges one sees on the cupboards in the cheaper class of motel room. The whole thing reeked of diesel and fish.

But when it started up and pulled away from the quayside I couldn’t believe the transformation. The motor — the motor! — this thing’s motor purred with a low, throaty, finelymeshed rumble that sounded more like a big Maserati than the godforsaken wreck it pushed through the water. With a burbling snort like a cross between leopard and drag racer, it hurled that entire shuddering hull of flotsam and junk from dead stop to harbour speed within seconds. It traversed the harbour like an arrow. Once outside the jetty it opened up into an unmuffled raspy tiger-on-the-prowl roar that sounded like a hydroplane racer at full throttle. I don’t know what was below the waterline, but it sure wasn’t what was above it.

I looked in astonishment at Iannis, who had returned to my table.

’Smuggler’s boat,' he said.

’Where do you think Libya gets its Marlboros?'

Café Concert

An elderly gent wandered in. He strummed on a loutro, the Hellenic ancestor to the lute.

Unfortunately, his ’Never on Sunday’ had the effect of ’Never At Any Time, Especially Right Now.’ Offkey, off-beat, voice like a kazoo, three tables away he smelled like an empty ouzo bottle.

Two British women at a table nearby gave him a sum and shooed him away. A pity. Compared with the nose rings and tattoos that make much of the midday quayside crowd, he was the most interesting character to pass all morning. After turning away this man as socially unacceptable, the woman

went back to her Daily Mail whose headline screamed in dissonant assonance, ’Mauler Mutilates Maid’.

I went back to the laptop. Two kids were playing hide-andseek amid the cafe chairs and potted palms. They were a study in the energy levels of face and voice that come with fantasy and spontaneity, one moment horseys and the next moment kitties, the gurgly incantations of tots miming adults, inventing games in which the rules change according to the mood of the moment, the instant inventions of kid play, kid laughter, kid flailing feet and kid akimbo arms, hide-and-seeking among the tables and elders and teapots and tabletop flowers and strollers and umbrella-shaded infants, all against background music of Cretan love songs. The sun was getting low by the time this pair’s mother gathered them up and swept off to home. Afternoon came alive in front of my eyes. The volta promenade’s self-writing stories were back on parade. The harajuku hairdos of young teens under the influence of TikTok’s highs. Deltoid hunks with their sleeves rolled up. The contented trudge of forty years of marriage. Silver hair and golden bangles. The tentative handholding of a second date. A jacket slung over a shoulder and a daughter hanging on a sleeve. Fishing smacks from East Harbour exited the lighthouse into the open sea beyond. In a hour or two they would be setting their yellow arcs of floats and hooks while back in the harbour the volta walkers would be settling into their floral cushions and florid menus.

The self-writing stories wee already on parade — styleconscious brushes at the hair, flip-flops, tattered cut-offs. A toddler’s pace turned his parents to toddlers too. A young man accessoried his hair like an electrocuted broom, with black tight pants, black tight shirt, a black leather shoulder bag, stride like a hammer on an anvil, and all made elegant by a single gold earring.

Amid these a Lotto-ticket seller made his rudderless rounds.

Iannis returned to my table.

'Are young Cretans religious?' I asked. 'I have seen only one pappas your age since I’ve been here.'

'Most young Greeks won’t have anything to do with the Orthodox Church. Orthodoxy has too many rules. Too many forbiddens. Too many excludeds. Too many againsts.’

‘The old folks knew tougher times.’

‘The old folks don’t know anything about the world we live in, while we know far too much about theirs. That is why most young Kritis just want to enjoy life. Get a good job that doesn’t demand a lot of work. Have all the sex we want and not have babies. Go on holidays as often as we can. It’s the European way. A lot of young Kritis want it that way here.’

'Why do young Cretan women still wear so much black?'

'When things change in Kriti, they are careful not to show it. If you really want to how young Kriti women are different, don’t look at their clothes. Look at how many times they go to the health and dental clinics. Why should they end up a toothless old crone just so Kriti can keep its image as the last old soul of Europe?’

’Do any quayside strollers ever ask what you think of them?’

’Kritis of today wonder why visitors can’t see us for what we really are. Real Crete is not down here in the cafes of the Old Harbour, it is out there in the Chalapa district and Nea Chora where everybody’s got a nice kitchen and a bedroom for every kid.’

To the signboard out front came two menu dawdlers. Each tapped their finger on the same item. Iannis smiled as he went out to greet them.

They dawdled no further and walked on. Iannis returned with no expression on his face.

’How many times a day does that happen?’ I asked.

’For every two couples that walk away, a third couple comes in.’

’You said it cost you six thousand Euros a month to operate a cafe like this.’

‘That is just the rent. We have to pay for the entire year in advance, even though we are closed four months in the winter. Then we have to hire people, buy food and drinks, pay insurance, electricity, the water, the cleaning crew at night.’

’I see how many tables fill and empty through the day, and have some idea of their bills. It doesn’t add up to seventy-two thousand Euros just for the rent. How do you get by?'

'This is mid-May. Things are slow. During the high season from June to the second week of September, the quay is packed all day long.’

’That is why I leave on May 30.’

’You cannot imagine what goes through my head at the end of an August day when we have never left this place while all the Hoorah Henrys and soccer yobbos are bellowing for beer and bitching about the bill. They go off to the beach while we stay here mopping the floors and cleaning the toilets. By 2020

we had worked five years to save enough to start our own kaphenion. Then Covid came along and wiped us out.'

'Why did you come back?'

'What choice do I have? I haven’t got a degree and I don’t know a politician. At the end of October, we are so exhausted we can’t face it any more. Teodos and Anna go to their family home in Salonika for the winter. By the end of November the quay is a ghost town.’

’And you?'

'I return to my family in Sitia on the eastern end of Kriti. I read a lot about New Age ideas — soul migration, reincarnation, nature mysticism. But it is easier to read about those things than living the way you need to achieve them.’

’Ownership kills the soul the same way it kills the mind. Where do you get the money to start over?’

'Relatives. In Greece the banks won’t loan to restaurants operated by people who haven’t lived in the area all their lives. And even more especially to restaurants that still need money after three seasons.'

Judging from the number of half-built shells at prime locations that I had seen along the highways, I could see the indirect effects of this. The rusting reinforcing rods sticking out of the unbuilt sections on top of a business were awaiting enough profits from the first floor to build the second floor.

'We Kritis have seen a lot of people come and go. Two thousand years of occupiers and a lot of pirates in between. We know how to take care of ourselves. But it makes for a tightfisted people. We would never go on the credit-card binges that northern Europeans go on. Kritis use a credit card only when absolutely necessary, and then don’t use it again till the balance is paid off.'

’Maybe that mindset is why Kriti has survived for so long.’

Down by the Docks

The perfect time to escape the crowds of the old Venetian quarter is also the perfect time to watch the local fishers depart at dusk.