A Feather on the Breath of God

Why are these women so seldom performed in the classical repertoire?

Anonymous (famous composer, often female)

Enheduanna (c. 2300 BCE)

Cai Yan Wenji (China, c,175 - c.240)

Sahakdukht (Armenian, early 8th century)

Xosroviduxt (Armenian, late 8th century)

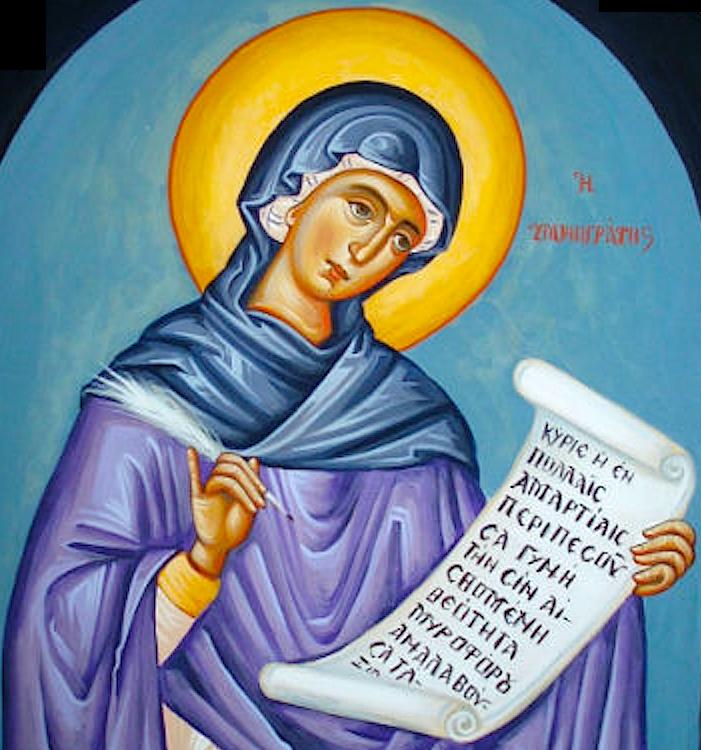

Kassiani (Byzantine, c.805 - 865)

Hildegard of Bingen (1098 - 1179)

Elizabeth of Schönau (1125 - 1165)

Iseut de Capio (c.1140 - 1190?)

Garsenda de Sabran (1181 - 1257)

Birgitta of Sweden (1303 - 1373)

Alamanda de Castelnau (1160 - 1223)

Azalais de Porcairagues (late 12th century)

Maria de Ventadorn (late 12th century)

Tibors Castelloza (1130 - 1198)

Garsenda de Proença (early 13th century)

Gormonda de Monpelier (fl.1226 - 1229)

Comtessa Beatriz de Diá (c.1140 - c.1200)

Suster Bertken (1426 - 1514)

Margaret of Austria (1480 - 1530)

Isabelle de Medici (1542 - 1576)

Gracia Baptista (fl. 1557)

Leonora Orsini (?1560 - 1634)

Raphaela Alleota (1574 - 1646)

Sulpitia Cesis (1577 - after 1619)

Lucretia Vizzana (1590 - 1662)

Alba Trissina (1590 - after 1638)

Settimia Caccini (1591 - 1638?)

Caterina Assandra (early 1590s - 1620)

Lucia Quinciani (fl. 1611)

Claudia Sessa (fl. 1613)

Francesca Campagna (1605/1610 - 1665)

Sophie Elisabeth (1613 - 1676)

Chiara Margarita Cozzolani (1602 - 1677)

Isabella Leonarda (1620 - 1704)

Mary Harvey, the Lady Dering (1629 - 1704)

Antonia Bembo (c. 1643-c. 1715)

Diacinta Fedele, (fl.1628)

Maria Xaveria Peruchona (c.1625 -c. 1709)

Maria Francesca Nascinbeni (1657/58 - ?)

Rosa Giacinta Badalla (c.1660-c.1715)

Elizabeth-Claude de la Guerre (1665 - 1729)

Bianca Maria Meda (c.1665 - post 1700)

Caterina Benedetta Gratianini (fl.1705 - 1715)

Camille de Rossi (fl.1707 - 1710)

Maria Margherita Grimani (fl.1713 - 1718)

Maria Teresa Agnesi (1720 - 1795)

Elisabetta de Gambarini (1731 - 1765)

Anna Bon (c.1740 - after 1767)

Elizabeth Hardin (c.1750 - 1780)

Juliane Reichardt (1752 - 1783)

Madame Krumpholtz (c.1755 - 1813)

Josepha von Auernhammer (1758 - 1820)

Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759 - 1824)

Jane Savage (c.1760 - c.1830)

Marianna d'Auenbrugg (? - 1781/82)

Ann Valentine (1762 - 1842)

Jane Mary Guest (Mrs Miles) (c.1762 - 1846)

Elizabeth Weichsell Billington (1765 - 1818)

Veronica Cianchettini (1769 - 1833)

Cecilia Maria Barthélemon (c.1770 - 1840)

Sophia Dussek (1775 - c.1830)

Fanny Krumpholtz Pittar (1784/88 - 1823)

Maria Szymanowska (1789 - 1831)

Emile Zumsteeg (1796 - 1857)

Maria Antonia Walpurgis (1724 - 1780)

Maria Antonia Walpurgis (1724 - 1780)

Madame Bruillon (1744 - 1824)

Maria Barthélemon (1749 - 1799)

Madame Louise (1746 - 1825)

Francesca Lebrun (1756 - 1791)

M. H. Park (1760 - 1813)

Hélène Montgeroult (1764 - 1836)

Jane Mary Guest (Mrs Miles) (ca.1762 - 1846)

Maria Margarethe Danzi (1768 - 1800)

Maria Snyzmanowska (1789 - 1831)

Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen (1745 - 1818)

Louise Farrenc (1804 - 1875)

Clara Schumann (1819 - 1896)

Elizabeth Stirling (1819 - 1895)

Faustina Hasse Hodges (1822 - 1895)

Clara Kathleen Rogers (1844 - 1931)

Marie Jaëll (1846 - 1925)

Sophie Menter (1846 - 1918)

Agathe Backer Grondahl (1847 - 1907)

Teresa Carreño (1853 - 1917)

Helen Hopekirk (1856 - 1945)

Ana Otero (1861 - 1905)

Dora Bright (1863 - 1951)

Elisabeth Kuyper (1877 - 1953)

Wanda Landowska (1879 - 1959)

Mary Howe (1882 - 1964)

Mana-Zucca (1884 - 1981)

Dora Pejačević (1885 - 1923)

May Frances Aufderheide (1888 - 1927)

Germaine Tailleferre (1892 - 1983)

Lili Boulanger (1893 - 1918)

Marie Christine Bergensen (1894 - 1989)

Cécile Louise Chaminade (1897 - 1944)

We but begin here. Roll up our sleeves. There’s a lifetime ahead.

KASSIANI is notable as one of only two Byzantine women known to have written in their own names during the Middle Ages, the other being Anna Comnena. She was born c.805 in Constantinople into a wealthy family and grew to be exceptionally beautiful and intelligent.

In 843 she had founded a convent in the west of Constantinople and became its first abbess. Her convent became associated with the nearby monastery of Stoudios, then in the midst of re-editing the Byzantine liturgical books — a process that occupied the better part of the 9th and 10th centuries.

The Emperor at the time, Theophilos, was a fierce iconoclast. Kassiani’s convent openly venerated the icons, which earned her a scourging with a last. Through it all she shouted, “I will not be silent when it is right to speak.” After his death in 842 his son Michael III and the Empress Theodora ended the iconoclastic era and peace was restored to the empire.

Kassiani eventually settled on the Greek Island of Kasos where she died sometime between 867 and 890 CE. Her tomb/reliquary may still be visited in the city of Panaghia. Kassia wrote numerous hymns still used in the Byzantine liturgy. They were spiritual poetry accompanied by music. She was regarded as an "exceptional and rare phenomenon" among composers of her day. At least twenty-three genuine hymns are ascribed to her. The most famous of her compositions is the eponymous Troparian (Hymn) of Kassiani sung late in the evening of Holy Tuesday in the week before Easter.

In his later years the Emperor Theophilus, secretly in love with her, wished to see her before he died. He rode to the monastery where she resided. She was in her cell writing the Troparian hymn when she heard the commotion of the imperial retinue. She hid in a closet, leaving the unfinished hymn on the table. Theophilus entered her cell. He intuitively understood that she was hiding in the closet, watching him, so he did not speak to her out of respect for her privacy. Then he noticed the papers on the table and read them. He sat down and added one line to the hymn, "Those feet whose sound Eve heard at the dusk in Paradise hid herself in fear". When had finally gone Kassiani emerged, read what he had written, then finished the hymn.

Kassiani’s Troparion is chanted only once a year during Holy Week. The Hymn is slow, sorrowful, plaintive. It lasts ten to twenty minutes depending on the choir’s chosen tempo. It requires a very wide vocal range, and is considered Byzantine chant’s most demanding piece. Cantors take great pride in delivering it well. The Hymn is traditionally associated with “those among woman who have suffered many sins”, a phrase associated with sex workers. In many places in Greece, “listening to the Kassiani” during the Matins service of Great Tuesday is a tradition among sex workers, who do not usually come to church. This has been the custom for so long that the hymn is now popularly referred to as “The Fallen Woman Hymn”.

BYZANTINE NOTATION is a neumatic system of musical notation traditionally used for rendering Byzantine chant into written form. “Neume” comes from ancient Greek πνεῦμα pneuma (“breath”). It is also called Chrysanthean notation, named for Chrysanthos of Madytos, one of its inventors. Byzantine differs from Western notation in that the latter is based on the pitch indicated by the position of the note on the staff. Byzantine notation adds a form of grace note related to the previous note (shown in red to the right). The grace note specifies the time interval from the previous note.

Byzantine music has eight tones called modes. These are not associated with particular “moods” as sometimes thought. Most Byzantine chanting can be done without written music because the original melodies (Gr. αυτόμελον) are so deeply embedded in the collective memory of religious services. Improvisation is encouraged, within certain constraints. There are tens of thousands of hymns in the Byzantine musical lexicon. All derive from fewer than two hundred original melodies.

Two major theological trends shaped the 12th and 13th centuries: changing the image of Jesus from a god into a man, and elevating the status of women from the obscure carpenter’s wife Miriam into the Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven.

Anti-feminism had dominated the Church for 1100 years. Hugh of St. Victor, one of the more renowned theologians before Hildegard’s time, wrote: “It is given to man that he is superior in intelligence and bodily strength: For woman is made that she is not only inferior by obedience, but by nature. It was wished by God that woman’s weakness causes love in man so that man loves woman out of kindness while woman loves man out of need“.

Hildegard had other ideas. Hildegard’s songs and numerous letters asserted that Mary gave birth not to the son of God but to the son of Man: “Mary brought more blessing over mankind than Eve had harmed it. The highest blessing for mankind was bequeathed by a woman“. Theologians were not thrilled at the news.

Unlike the restrained plainchant of her day, her lyrical songs were rhapsodies of emotion that could soar across two and a half octaves in a single unbroken vowel of notes. Her musical leaps and swirls liken more to ballet than to liturgy.

Hildegard countered the theologians and inquisitors with the idea that woman’s nurturing and peace-loving character made women superior to men. Unsurprisingly, within a century of her passing she had been erased from the liturgical record. She remained an obscure visionary until she was rediscovered by feminist musicologists in the 1970s.

COMTESSA BEATRIZ de DIA (c1140 – c1200) was a trobairitz, a female troubadour. Most troubadours were surplus aristocratic progeny who could not expect to inherit the family estates and were reluctant to join the priesthood — to say nothing of the soldiery. This left them in the agreeable position of considerable funding plus free time on their hands. Affairs were frequent and fun. This had its downsides: narrowly escaping the noose of a cuckholded lord begat a rich legacy of escapist entertainment.

The long hours of learning a musical instrument were a minor bother compared with the employment opportunities it offered to the footloose and feckless. Music compensated for the brigand-infested dangers of wandering from castle to castle.

Unsurprisingly, troubadour music became the 12th through 14th century version of the rock band for those keen on wooing the ladies, married and not, of the castles troubadours visited. Most troubadour songs are about courtly love. In principle such love was unrequited, but history tends to suggest the opposite. The rarer visits of a trobairitz rather suited the fancies of temporarily spouseless noblemen keen on a piquant bout of romantic revenge. If husbands were expected to look the other way during the visit of a gifted male voice, well, the slipper fits on the other foot, too.

Beatriz was the wife of Guillem of Poitiers, the earliest troubadour whose works survive. Apparently rather eager to take to the calling, she became the lover of the most famous troubadour of the age, Raimbaut d’Orange (1146-1173), on those occasions he was not otherwise engaged. He was six years younger.

At the time it was fashionable to write the lives of saints in biographies called vitas. Troubadours found saintly pieties unappealing so they wrote secular versions called vidas. Beatriz’ five extant songs are a gleaming necklace adorning the reputation of troubadours as lovers of literary expression fully equal to their reputations otherwise.

Five pieces attributed to Beatriz have been described as the cattiness of someone jilted — a notion tempered by the fact that since musical history was written by men more likely to be cuckees than cuckholds, they revenged with the adjective.

Of Beatriz’ five pieces, only one has musical score, A chantar m’er de so qu’ieu non volria. The score appears in Le Manuscrit du Roi collected by Charles of Anjou (1226-1285), who was the brother of Louis IX (1214-1270). Le Manuscrit du Roi contains over 600 songs composed in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Of things I’d rather keep in silence I must sing: Bitter do I feel toward him

Whom I loved more than anything.

With him my mercy and fine manners were as vain As my beauty, virtue, and intelligence.

He tricked me and he cheated me.

With me he always acted so cold,

But with everyone else he was so charming. Ah, but in love I have my victory, And now I surpass the worthiest of men.

There’s no woman near or far Who wouldn’t fall for you if love were on her mind.

But you, my friend, should have the acumen To tell which one stands out above the rest.

So don’t you forget the stanzas we exchanged.

My worth and noble birth should have some weight. My beauty and my noble thoughts,

So I ask you, there on your estate, I want to know, my handsome noble friend, Why I deserve so savage and cruel a fate.

Messenger, make him comprehend

That he not the first nor will be the last to be undone by too much pride.

Vaghi amorosi augelli

O notte o cielo o

I want to show the world the vain error of men that they alone possess the gifts of intellect and artistry, and that such gifts are never given to women.

Not much is known about Maddalena Casulana (c.1540 –c.1590) other than she was an Italian composer, lutenist and singer during the Renaissance. She was the first woman to have her music printed and distributed beyond Italy. She is remembered for her madrigals; hundreds were published in collections during her lifetime. Several dedications to Isabella de’Medici indicates a deep friendship between the two. Her work was respected and performed often; there is evidence that Orlando di Lasso conducted works by Casulana at the court of Albrech of Bavaria in Munich. A total of 66 madrigals survive today. Her work is available in the public domain; six are on YouTube. Though there are few written records of her life, she did leave strong words regarding her position as a woman in a profession dominated by men. (See above.)

Music more beautiful than words.

A

When we listen to an unknown piece of music, can we tell whether a man or a woman wrote it? Does it make any difference to the music once we know?

The oldest known complete melody, the Hurrian Hymn, was a praise-song to a woman. It was composed six centuries before the earliest texts in the Bible. It was one of 36 song fragments discovered in the 1950s in a 15th century BCE royal palace at Ugarit on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. The “score” would be unrecognisable as music to us. It was in the wedge-like characters of cuneiform on baked-clay tablets. Only one of the songs is complete enough to be playable today. The song’s colophon reads, "This song is in the nitkibli tuning of a-zaluzi written down by Ammurabi". The musical scale was five notes equipartitioned across a musical seventh in today’s notation. It was meant to be sung by women in praise of Nikkal, the Moon Goddess of the Orchards.

During Biblical times King Solomon's Temple is said to have had 24 choral groups and 288 musicians who performed 21 weekly services. The 150 Psalms in the Book of Psalms ascribed to King David became the bedrock of JudeoChristian hymnology. No other ancient poetry has been set to music more often, yet we have no idea what it sounded like. This is the case with most ancient music. Of the several ancient Greek musical treatises which lay the foundation for modern music theory, little is in notation form; most of it is fragmentary at best.

Yet neither the destruction of the Temple nor the fall of Rome silenced the spirit of song. A century before Kassiani two Armenian women, Sahakdukht and Xosroviduxt, wrote devotional hymns for nuns of the Armenian Rite church. Sahakdukht’s Srbuhi Mariam was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Khosrovidukht was a member of the royal family and composer of the šarakan (canonical hymn) Zarmanali e Ints ("Wondrous it is to me"). It is an exquisitely lyrical hymn to her brother, available today on YouTube under “šarakan, Sharakan Early Music Ensemble”. Lovers of the lyrical, ancient or otherwise, should not miss Lusine Zakarian’s 1995 Armenian Medieval Spiritual Music album on YouTube.

In our more familiar terrain of Western Christendom, what happened between the Temple and marketplace music of Jerusalem before the Roman invasion in 63 BCE, and the Gregorian chant we listen to today? Marketplace

and street-fair music is so mutable we have no idea what it may have resembled before being painted into history by the iconic peasant-carouse paintings of Breughel showing those carnivalesque bagpipes and whistles. Music destined to be liturgical likely followed the Disciples north into what became Byzantium, and west by boat to Rome. Its Orthodox variants are still sung at high mass today, memorably at Easter. Music made it to Rome with or without Saint Paul’s approval, and in due time found its way into the court of Charlemagne. It was memorised by monks but not formally written until Guido of Arezzo c. 1028. More mysterious is what became of the music that followed St. Mark into Alexandria in the footsteps of the Christian diaspora. The tapestry of musical history is fragmentary and faded here, but threads are discerned in the liturgy of the most isolated branch of the Christian faith, the Coptic rite. YouTube is an Abyssinio-Alexandrine treasury here.

Western music doesn’t really get rolling until St. Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1176). Had she married a king instead of God, Hildegard would be a musical Eleanor of Aquitaine to us. One of her best-known works is the Ordo Virtutum, the first morality play and the only one for which both the text and the music survive. It narrates how a group of Virtues successfully best Satan, who has hatched a skullduggerous plan to trap a guileless soul. The score calls for 17 female soloists coloraturing the Virtues, while Satan has but a spoken part. The Devil, of course, cannot produce divine harmony. His vocal strangulisms in the Lenten Carnival starting the Tuesday after Easter must have sounded like someone doing unspeakable things to a bassoon.

The secular Middle Ages bequeathed us female wandering troubadours called trobairitz, who composed the first songs sung by women to women. The song Na Maria by Bieris de Romans went so far as to feature a woman singing a love song to another women. Unable to halt such unseemly goings-on, the Church fathers called it a devotional song to the Virgin Mary.

A few centuries later Venice became the centre of the East-West music world. New genres of vocal music developed during the late Renaissance and early baroque periods which evolved into the first opera in the year 1600. The most famed woman composer of the time was Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677).

And there alas we must leave it for now. The music is about to begin. If you would know more, write douglasbullis@gmail.com.

Barbara Strozzi was born in 1619 the illegitimate daughter of Giulio Strozzi and his long-time servant, Isabella Garzoni, who eventually inherited his estate. Giulio recognised his daughter's musical talent, even creating an academy in which Barbara’s compositions could be performed publicly. He was quite keen to showcase Barbara’s considerable vocal ability to a wider audience. To his credit he allowed her the freedom to grow at her own pace, unusual at a time when prodigy was dominated by frankly venal parents.

Singing was not Barbara’s only talent. Very early on she displayed such a gift for composition that her father arranged for her to study with composer Francesco Cavalli, himself a student and musical heir to Monteverdi.

Barbara led a quiet life, devoting herself to music and her children. Three of her four children were fathered by Giovanni Paolo Vidman, a patron of the arts and supporter of early opera. When Vidman died he did not leave anything to Strozzi or her children in his will. Ever self-reliant, she supported herself by her investments and her compositions.

Strozzi was considered the most prolific composer of printed secular vocal music in Venice in the middle of the century. Her output is also unique in that nearly all of it consists of secular vocal music; the exception is a small volume of sacred songs. She was renowned for her poetic ability in addition to her compositional talent. Her lyrics were as articulate as they were lyric.

Che si può fare

About three-quarters of her printed works were written for soprano. Her compositions were firmly rooted in the seconda pratica tradition. Even then Strozzi’s music was more expressive in its lyricism, relying heavily on vocal dexterity.

Many of the lyrics for her early pieces were written by her stepfather Giulio. After he died she wrote her own lyrics for the rest of her life. She died in Padua in 1677 at the age of 58.

Abraham and Lea Mendelssohn were the cosmopolitan, cultured parents of Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn. They shepherded their children’s education carefully — French, German, Latin, Greek, arithmetic, geometry, geography, literature, music theory, violin, drawing. They wanted Felix and Fanny to develop cultural and intellectual richness tempered with a sense of discipline. Raising children this way was rather advanced parenting for the time.

Both children made striking progress in their musical studies. Their youthful mastery of musical technique amazed those who heard them play. Before they reached their teens, both children were producing their own compositions. By the time he was nine Felix featured in public concerts as a soloist. Thirteen-year-old Fanny pulled off the remarkable feat of performing all twenty-four preludes from J. S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier — from memory. She then disappeared from public performance for twenty years. Sadly for posterity, the social conventions of the time discouraged women from pursuing musical careers. Fanny’s aspirations to life as a public performer were firmly quashed. In an 1820 letter to her, Fanny’s father Abraham informed her that music was to be Felix's profession. "For you it can and must only be an ornament, never the basis of your being and doing.”

The following year Fanny met and fell in love with painter Wilhelm Hensel; they married in 1829 and settled into the socially acceptable domesticities deemed appropriate by society of the time. Still, her musical creativity continued to manifest itself. She was the prolific but semianonymous creator of over five hundred musical works. Much of it was in the properly "feminine" small-scale genres of keyboard pieces, songs (she wrote over two hundred fifty), chamber music, and choral works. In 1838 she returned to the concert stage when she performed Felix’s First Piano Concerto for a charity benefit. Her virtuosity on the piano was reported to equal, perhaps even surpass, her brother Felix. She died in 1849 just 42 years old of a massive cerebral haemorrhage — the same fate that met Felix a mere six months later.

Amy Beach was the first successful American woman composer of large-scale work. She was one of the first American composers to succeed without the benefit of European training, and one of the most respected and acclaimed American composers of her era. Her "Gaelic" Symphony, premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1896, was the first symphony composed and published by an American woman.

A child prodigy by any measure, she could sing forty songs accurately by age one (yes: 1). She could improvise counter-melody by age two. She taught herself to read at age three. At four, she composed three waltzes for piano during a summer at her grandfather's farm; there being no piano in the house, she composed the pieces mentally and played them when she got back home.

She began piano lessons with her mother at age six. By eight was giving public recitals of works by Handel, Beethoven, and Chopin, as well as her own pieces.

At 18 she was married to Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, a Boston surgeon twenty-four years her senior. Her concert name was changed to “Mrs. H. H. A. Beach”. Her husband deemed that she was better suited as a society matron and patron of the arts, so she gave up piano teaching because it was “an activity widely associated with women.” Dr. Beach disapproved of his wife studying with a tutor, which ended her education in composition, and limited her performances to two public recitals per year.

Undeterred, she went on to compose eight landmark works and both performed and conducted the major symphony orchestras of her time. A German critic wrote, “We have before us undeniably a possessor of musical gifts of the highest kind; a musical nature touched with genius, the first American woman able to compose music of a European quality.” The story of her life as related on Wiki is one of the most inspiring reads one is likely to find.

"Every now and then, everything would suddenly fall into place … at these moments I was flooded with a wonderful feeling of potential power … Every composer … however obscure, is surely familiar with this sensation. It is a glorious one."

I know my love I know where I'm goin' As I was goin' to Ballynure

Rebecca Clarke was born in London in 1886. Her life spanned from the late Victorian era through the end of the 1970’s — a period during which the role of women changed unimaginably.

Many years of study at London’s Royal College of Music propelled her into the ranks of the most distinguished violists of her time. But with achievement came also belittlement. In 1919 her Viola Sonata tied for first place in the Berkshire Festival Chamber Music competition — an unheard of accomplishment at the time. Jealous rumours promptly circulated that Clarke really hadn’t written the piece by herself; that it was impossible for a woman to have written music so accomplished.

It took a lifetime of hard work as a full-time composer and performer to overcome the stigma being born a woman. Yet she prevailed, and spectacularly. At a concert late in her career, Arthur Rubenstein himself introduced her as the "glorious Rebecca Clarke.”

When Emma first described this concert my reaction was, “Sweet! Repertoire I’ve never played before!” I love to explore the music of lesser-known composers and these women were eye-openers for me. I had never heard of Maddalena Casulana and Francesca Caccini, but I’m certainly going to hear a lot of them now! After studying their music note by note while seeing it as well on the large scale of their lives and times, I heartily agree that early women composers need more exposure. This is but a taster amid a fabulous banquet of sound.

If I were to add to this concert, it would include Nadia Boulanger’s "Trois Piéces" for cello simply because it is so beautiful. Nadia and her sister Lili’s compositions are truly special. I was delighted to learn that Nadia Boulanger taught the pop music icon Quincy Jones! Who knew.

It's hard to carve out one's own niche in music today. It’s near-impossible to put myself in the shoes of these women and the obstacles they faced simply because they were women. They give me strength to compose new music for the cello, to collaborate with musicians and other creative people outside of the classical music realm. For that reason I am also doing film scores these days, and of all things, video game music. It is a rich life, this music we love.

No one can do this alone. I honour my cello teacher David Cole the most. He helped me find meaning and purpose as a cellist and as a communicator who uses music as the voice of my soul.

I had never heard of these women before. Then I had the opportunity to perform works by Rebecca Clarke and Hildegard von Bingen in November last year. I left the concert brimming with excitement about classical female composers and the audience's response to them.

I have mixed feelings about the anonymity these women have been assigned in the vocal syllabus. Sad because in all my schooling I had never heard their names. Yet now I soar in my spirit because I have years ahead of me to add my voice to the great chorale of the standard repertoire, hoping it will bring others to shed their light onto the shadows of our forgotten ancestors.

In putting this programme together I came across over 150 female composers whose names I had never heard of. Names that are available today thanks to the work of 1970s feminist musicologists and those performers who have sung before me. It's hard to carve out one's own niche in music today. My wish is to continue reintroducing Western Art Music’s women composers to the public ear, and to advance the work of South African composers.

Many have helped me. I appreciate “Miss Jo”, JoNette Le Kay, Doug Bullis & Elysoun Ross, and Gareth Walwyn the most. They have buoyed me with their mentorship, and liberally shared their expertise. Sheryl Sandberg, author of "Lean In”, eloquently elaborates upon the importance of professional mentorship.

Hardly anyone makes a living at music. I do it because it is my calling. I was born to perform. I am as much the music I sing as it is of me.

At last we have entered an era in which women are finally speaking out and expressing their agency. How exciting to be involved in an event that is so pertinent to the atmosphere of the time. It has been a memorable and life changing experience practicing only female composers, because I can relate to their personal expression from an equally personal position, woman to woman. Although I adore many of the male composers, knowing that these pieces were written by composers who were also capable of giving birth and nurturing life in a visceral way has been especially life affirming.

I make a living from teaching and performing music because life is short and I don't want to waste my time. Music is the most profound way I know to inhabit time. Indeed, to outlive it. I plan on performing the music of one of my close female friends next year, and exploring the contemporary female experience through performance and writing.

I am inspired by men and women who do not fall prey to the absurdity of prejudice in any form, and of course anyone with whom I share a love of music.