3 minute read

WATER QUALITY IS VITAL TO A HEALTHY HERD

By Steve Ensley, DVM, PhD, & Scott Fritz, DVM, Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Large animal veterinary toxicology cases typically account for 5-10% of all cases seen on a routine basis by a large animal practitioner. Infectious diseases are the main cause of decreased health and performance; therefore, we spend a vast amount of time in veterinary school talking about bugs and drugs. This article focuses on drinking water quality for food animals.

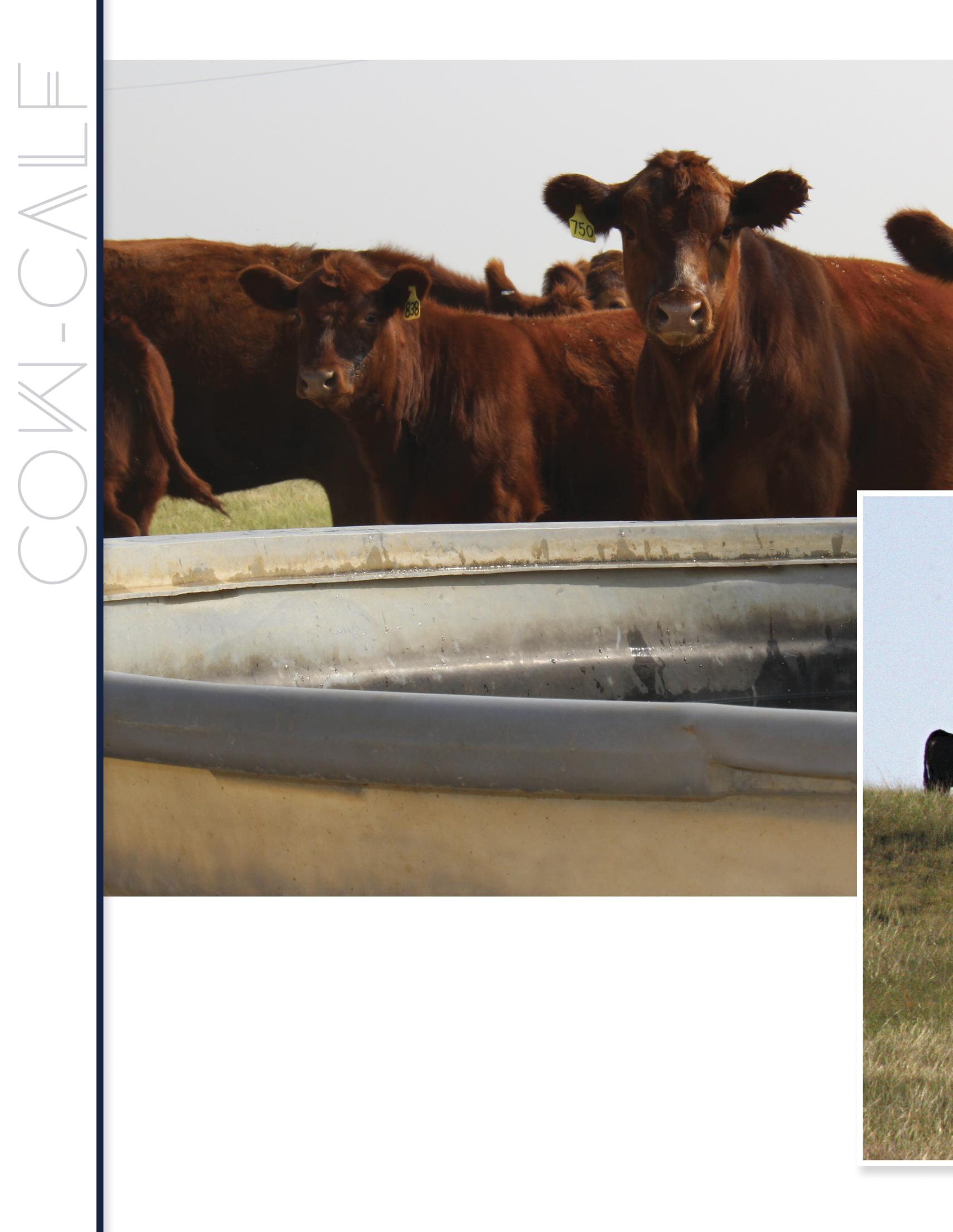

Drinking water quality and quantity for production animals is often misunderstood. Drinking water is the most important ingredient in food animal production. Some questions to ask about your drinking water include: what is the surface water source? If well water is used, how deep is the well? How old is the well? Is the well cased or not? During times of adequate rainfall, the typical surface water sources like ponds, dug outs, artesian water, creeks, rivers, and sub irrigated meadows provide adequate quantity and quality. Surface water sources during drought periods can be problematic in both quantity and quality. Drought conditions can concentrate some of the soluble components like sulfate to hazardous levels. Elevated concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus can lead to blue-green algae blooms. Drinking water testing should be done before animals are offered this water as their drinking water source.

Water testing is typically done at laboratories that do human drinking water analysis. Most laboratories do an excellent job of analyzing the drinking water. Interpreting the report’s results is where inconsistencies develop. The normal ranges for the different drinking water parameters used to interpret animal drinking water are different from human drinking water standards. When these drinking water parameters are flagged as out of the normal range, there is unnecessary concern. You need to make sure the drinking water laboratory you are using has normal ranges for food animals and knows how to interpret them.

The water collection bottle needs to be as clean as possible. If you are going to measure coliform (fecal contamination) in water, the sample needs to be collected as aseptically as possible. It is easiest to get a drinking water container from the local convenience store, so you do not have to use the empty soda bottle on the floor of the pickup as your sample container. To collect an animal drinking water sample from a well, you need to collect one as close to the well as possible, then a second sample at the most distant part of the water distribution system. To collect a sample from surface water, collect the water sample at least a few feet away from the bank and fill the bottle, dump it out, and then refill it. After collection of the water sample, keep it cool and get the sample to the laboratory as quick as possible.

Blue-green algal blooms occur in surface waters that we use for animal drinking water during the summer months. If you suspect an algal bloom, you need to collect a sample of the affected water. Appropriate samples are a water sample of at least 100 mL collected an inch below the water surface. Samples should be refrigerated before and during shipping. Do not freeze the sample as this may lyse the cyanobacteria. When collecting water, gloves should be worn, as some cyanobacteria produce dermatotoxins. If Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (KSVDL) identifies cyanobacteria in the sample, a test for the most common toxin (microcystin) can be performed. To watch a short video on blue-green algae sampling, visit the KSVDL YouTube page at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= wOogJtDNUfQ&list=PLNjV05pK4JEVLnizQ_jEiqLN1eYdp Jtdq&index=6&t=0s.

Dr. Steve Ensley graduated in 1981 from Kansas State University with a DVM. After 14 years in mixed practice in the Midwest, he received a MS and PhD in veterinary toxicology at Iowa State University completing his PhD in 2000. Dr. Ensley has worked for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Bayer AG, Iowa State University, and Kansas State University. Dr. Ensley’s interests are clinical veterinary toxicology and applied veterinary toxicology research. Dr. Ensley has published extensively on applied veterinary toxicology and gives numerous presentations on these topics. Food animal veterinary toxicology is his passion.

Dr. Scott Fritz is a Diagnostic Toxicologist at the Kansas State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Dr. Fritz grew up in south-central Nebraska and earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from Hastings College (NE) and his DVM from Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Fritz spent five years in private practice working nearly exclusively with beef cattle in rural South Dakota. His interests are centered on food animal clinical toxicology.