6 minute read

HEAT LOAD REVIEW

By Dr. Kev Sullivan, BVSC, Bell Veterinary Services

Summer is fast approaching, and at this time of year, it is timely to review the heat load management plan for your feedlot. In this article, I will discuss the causes of heat load and the major risk factors as well as the signs cattle exhibit and the behavioral changes that the cattle go through as they load up more heat. I will also discuss some of the key factors involved in preparedness and prevention.

Factors contributing to heat stress

A combination of two or more of the following environmental conditions are needed to produce a heat stress event:

• A recent significant rainfall event

• High ongoing minimum and maximum ambient air temperatures

• High and ongoing relative humidity

• Absence of cloud cover and high levels of solar radiation

• An extended period (4-5 days) of low or no air movement

• Sudden change to adverse climatic conditions (a lack of time for cattle to adapt)

Feedlot deaths have been greatest when a rainfall event is followed by several days of high temperatures and high humidity with low air movement and only limited overnight cooling.

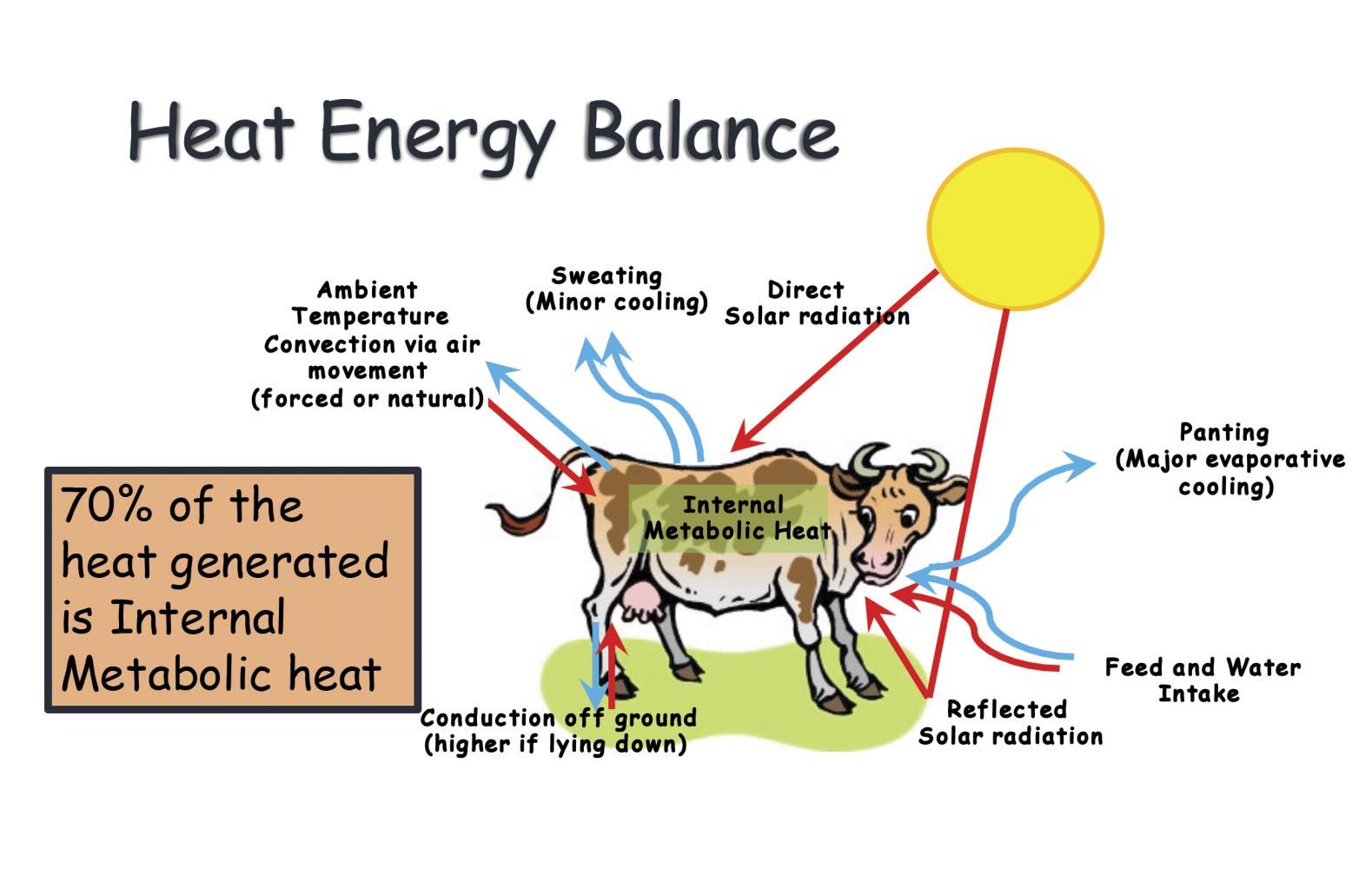

When the total amount of heat generated by the animal plus the heat absorbed from the environment is greater than the ability of the animal to dissipate the heat into the environment, heat is stored in the animal. This is called heat loading.

Factors to assess heat stress

The heat load index is determined by the weather and is out of our control (black globe temperature, humidity, and wind speed). The point at which animals accumulate heat (Heat Load Index threshold) is a combination of animal factors (breed, coat color, health, acclimatization, and days on feed) and environmental factors (pen conditions, mud depth, water temperature, water trough space, shade, and bedding).

Recognizing heat stress

It is important to watch the weather station information and the weather forecast, but most importantly the cattle will tell you how they are coping by their behavior and physiological response. Look at the cattle and observe their respiration rate and the level of panting. Watch their feed intake and their behavior. Check your high-risk cattle at daybreak and every few hours throughout the day.

Cattle progress through a series of behavioral changes as the exposure to heat load conditions increases. The animals adopt these behavioral changes in an effort to maintain acceptable levels of comfort. These behavioral changes are as follows:

1. Body alignment with solar radiation

2. Shade seeking

3. Increased time standing

4. Reduced feed intake

5. Crowding over water tank

6. Body splashing

7. Agitation and restlessness

8. Reduced or stopper rumination

9. Bunching to seek shade from other cattle

10. Open mouth and labored breathing

11. Excess salivation

12. Ataxia/inability to move

13. Collapse, convulsions, coma

14. Physiological failure and death

Cattle coping

Cattle not coping

Cattle always seek shade if it is available, so in shaded pens, many of the first nine behaviors may not be evident.

Panting score and respiratory rate

Respiratory rate and panting score are useful indicators of heat stress in cattle because they are the first visual changes seen in hot conditions. Panting score, breathing condition, and respiratory rate are shown in the following table.

1.0

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5 normal. Difficult to see chest movement.

Slight panting, mouth closed, no drool or foam. Easy to see chest movement.

Fast panting, drool or foam present. Easy to see chest move. No open mouth panting.

As for 2.0, but with occasional open mouth, tongue not extended.

Open mouth plus some drooling. Neck extended and head usually up.

As for 3.0, but with tongue out slightly, occasionally fully extended for short periods plus excessive drooling. Neck extended and up.

Open mouth with tongue fully extended for prolonged periods plus excessive drooling. Neck extended and up.

As for 4.0, but head held down. Cattle breath from flank. Drooling may cease.

The following table shows the relationship between accumulated heat load units (AHLU), cattle indicators, and heat stress risk.

What should be considered when evaluating when to intervene and mitigate?

There are some key monitoring points that should be considered in making the decision to intervene. The first of the two that I think are most important is the percentage of cattle with a panting score of over 2.5 at 6:00 am. If that is more than 10%, then it is going to be a tough day. The second key point is the amount of overnight cooling that has occurred. As a guide, if the overnight temperature has been less than 68˚F for more than 6 hours and the wind speed is more than 5mph, then the cattle will have a big chance of having unloaded most of their heat overnight. It is very important to keep a close watch on the forecast for today and the next three days.

When the feed intake across the yard has decreased by 10% or more, then the cattle are in a status of heat load.

Mitigation

In summer, if the forecast is poor and a heat stress event is likely, then there are some things that can be done. One of the key interventions is to stop cattle work or cattle movements. Processing, sorting, reimplanting, revaccination, and moving cattle can increase the animals’ body temperature by 3-4˚F. This is sometimes enough to tip those cattle over into a heat stress crisis. Some mitigation strategies are shown in the following table.

Use of sprinklers can be beneficial especially in low humidity environments. The main objective is to wet and cool the pen floor so cattle can choose to lie down in comfort and dissipate heat. It is essential that the sprinklers do not make mud puddles for cattle to stand in and create mud slop holes. This will exacerbate the heat stress problem. The use of sprinklers has shown to reduce the temperature of an unshaded pen floor from 140˚F to 95˚F.

Feeding management

One of the important ways to manage heat load is through dietary management. Seventy percent (70%) of the heat comes from metabolic heat, that is heat generated by the animal. Therefore, trying to manage the heat generated by the animal is an important aspect to heat stress management. The response of cattle to mitigate heat stress is to stop eating. It is not uncommon to see reductions in feed intake by 30-50% if cattle are fed without any change in ration or in bunk management in the early stages of a heat stress event. The key to heat stress dietary management is to try and maintain feed intake throughout the heat event as best as possible and have cattle return to pre-heat stress intakes as soon as possible after the crisis has passed without developing rebound acidosis. There are several methods to managing feed and feed intake. One is to move cattle to a “heat stress” ration early in the event. These rations are usually designed to reduce the heat generated from digestion and typically these rations are fed until about 48 hours after the crisis has passed. A second approach is to manipulate the amount cattle are fed without changing the ration and reduce the metabolic heat load by reducing the allocation starting before the heat stress event occurs. The program relies on reducing allocation to 85 or 90% before, during, and after the event and maintaining a slick bunk program throughout, letting the cattle down on feed intake rather than letting cattle stop eating themselves. This method has shown to have a much better return to pre-heat stress intakes after the crisis has passed than other heat stress feeding management systems.

Other approaches in feeding management include increasing vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants as well as ionophore throughout summer. Increasing fat in the diet reduces heat increment, however antioxidants are needed to prevent oxidization of the fats during the heat of summer.

The use of betaine in the diet has shown to reduce panting scores in cattle and improve feed intake during heat load events. Betaine in the supplement has become an important part of heat load management for many feeding operations. This osmolyte helps maintain cellular integrity of the gut, improves cellular hydration, and spares energy which is then available for production.

Pen management

Pen management is probably the most important factor in reducing the risk of heat stress. Ensure that the manure load in the pens in the runup to summer is reduced to no more than two inches of dry manure in the pen. This will produce six inches of wet manure following a significant rainfall event. More than six inches of wet manure not only contributes to the humidity of the pen but also produces noxious gases that the cattle inhale, and the physical exertion of moving through these muddy pens increases the heat production in these animals. Furthermore, the manure that gets caked on the hide further increases the heat that the animals are exposed to.

Summary

Every summer has risks of heat stress. The effects of heat stress are dependent not only on the magnitude and duration of the event but also on the rate at which environmental conditions change.

Losses of healthy cattle during heat stress events should be small or non-existent if adequate preparation and mitigation strategies are put in place. From an animal welfare standpoint, the use of shade, shelter, and other mitigation strategies in summer is recommended for most cattle that are confined and are on full feed.

With the current feed and cattle price structure, the economic benefits of minimizing the effects of environmental stress are greater today than in the past. In addition to the performance response, environmental stress mitigation has significant animal comfort and consumer perception implications.