7 minute read

LIVING THE DREAM –PRODUCTIVE COWS AND HAPPY CALVES

By Richard Prather, DVM, Ellis County Animal Hospital, Production Animal Consultation

In the Fall 2021 issue of Protein Producers , Dr. Ray Stegeman provided the perspective of stewardship in what we do as caretakers of God’s creatures. Dr. Nels Lindberg emphasized the importance of people accomplishing our mission while here on earth. The origin of Dr. Ray’s and Dr. Nels’ wisdom can easily be followed in Genesis 2:19 when the Lord brought every living creature to Adam to see what he would call them. In that era of our history, Adam was destined to spend unlimited time enjoying the blessings of grazing livestock and we are told each animal was designed “to be fruitful and multiply”

If we continue to follow the history of the interaction of God with people and animals, we see one of the early concepts of genetics, DNA, and animal caretaking. Noah, along with his wife and family, followed precisely the designed plan for the first recorded animal husbandry equipment that would meet the needs of both his family and the animals during the great flood. The people and animals that heeded the call of the Creator and survived the storm carried with them the genetic DNA for understanding and appropriately responding to the impending elements of a challenged world.

Practical implementation of sound principles and lessons from the past improve the likelihood of successful reproduction and fruitful growth of a highly marketable calf. Jumping forward to today’s challenges in animal husbandry, Dr. Randall Spare described how strategically measuring Body Condition Score (BCS) during the annual management cycle of a cow herd benefits nutritional decisions and mitigates risk of challenging winter weather as well as the everchanging seasons of rain or drought. If today’s beef producers are to be sustainable, the cow-calf operation must be profitable as well as enjoyable. In today’s discussion, we will elaborate further to combine the science and animal husbandry tools made available to us by astute animal caretakers.

Body Condition Score at Calving (BCS)

The critical factors that determine when a cow will cycle for rebreeding after calving are:

• day of calving relative to calving season length

• Body Condition Score at calving

• milk producing ability

• nutritional status

Each of these factors have a built-in cost. Kansas State University and the Kansas Farm Management Association data show that 60% of the annual cow-calf profit is affected by cost and 40% of the profit is determined by revenue.1 To optimize the cost/revenue equation, cowcalf producers must find balance between feeding enough to achieve adequate breed back after calving while being careful not to consume too much of the revenue of weaned pounds sold. The nutritional requirements from calving until early in pregnancy is the most expensive portion of the annual cow cycle in terms of dollars that need to be spent for both energy and protein. The number of days from calving to first breeding is largely determined by the BCS of the cow on the day she calves as well as her ability to produce milk. Cows have an average 283-day length of pregnancy, which leaves 82 days to become pregnant again and continue to calve once every 12 months. The uterus requires a few weeks to recover after calving before the cow is capable of cycling or successfully becoming pregnant during bull exposure. Cows are only receptive to the bull once every 21 days, leaving roughly 2-3 opportunities to become pregnant and maintain one calving per year. A thin cow, calving with a BCS of 4 or less, will take longer to rebreed and likely miss these critical opportunities. Ideally, to breed and stay in sync with the calendar, the breeding cow herd manager should attempt to target an average BCS of 5 or slightly greater at calving. As Dr. Spare discussed, to keep cows from falling behind or culled as open, intentional monitoring of BCS can help mitigate this risk. Forage management, feed supplementation, and strict commodity cost control are key management tasks required for the operation to remain profitable. A frequently overlooked method of managing the high cost of feed is matching the cow to her environment and selecting replacement offspring from successful cows. Simply put, a 1,600 lb. cow producing 30 lbs. of milk per day grazing the tall grass of southern Missouri is not as likely to succeed in a harsher environment of the Texas panhandle as would a cow weighing 1,200 lbs. and producing 20 lbs. of milk per day grazing little bluestem and grama. The bottom line is to find balance in managing BCS at calving while keeping feed cost under control.

Utilizing Technology to Increase Pounds Marketed – Front Loading the Breeding (Calving) Season

Pounds of offspring sold is the largest revenue stream for the cow-calf operation. The single most important influence on pounds weaned is days of age. Technologies available to maximize pounds weaned include use of natural service sires with synchronized estrus, artificial insemination (A.I.), and implanting. University of Nebraska Extension researchers demonstrated that turning bulls out on day 0, followed by a single dose of prostaglandin on day 5, shortened the breeding and subsequent calving season from 60 to 45 days and numerically increased weaning weights.2 NAHMS data show A.I. to be highly underutilized in commercial beef cow-calf operations.3 Seedstock producers recognize the benefits of A.I. and have made tremendous genetic progress in far less time than would have been required by natural service. With the development of new products and the improved estrus synchronization protocols over the past several years, commercial cowcalf producers are now successfully utilizing fixed-timed artificial insemination (FTAI) for improved genetics and profit at the market. With existing facilities and labor, FTAI can be conducted at the same or less cost per pregnant cow as natural service. Producers may choose to utilize the benefits afforded by the technology of implanting without any additional labor or facility modifications. Implanting nursing calves that are at least 30 days of age has been shown to increase weaning weight by as much as 32 lb. in an independent multiphase study involving multiple university extension researchers.4 Commercial herds that have adopted both FTAI and implants have improved weight per day of age from 2.9 lbs. weight per day of age to 4.7 lbs. weight per day of age at weaning.5

Sire in the Equation

Producers with an intentional effort to front load the calving season are diligent in their efforts to ensure proper fertility of the pasture sires. If the cow herd nutrition has been appropriately addressed, a fertile sire should be able to settle approximately 2 out of every 3 coverings for an anticipated 65% or greater first service conception rate, with 85% of the cows pregnant by the end of the second 21-day breeding cycle. Sires that have a semen morphology analysis with >70% normal sperm are necessary to achieve adequate front loaded calvings. Numerous complications can arise in any given year such as the tremendous cold weather surge experienced over a large part of the country in early 2021. Therefore, annual bull breeding soundness evaluations are necessary prior to each breeding season and will be discussed in further detail in this issue.

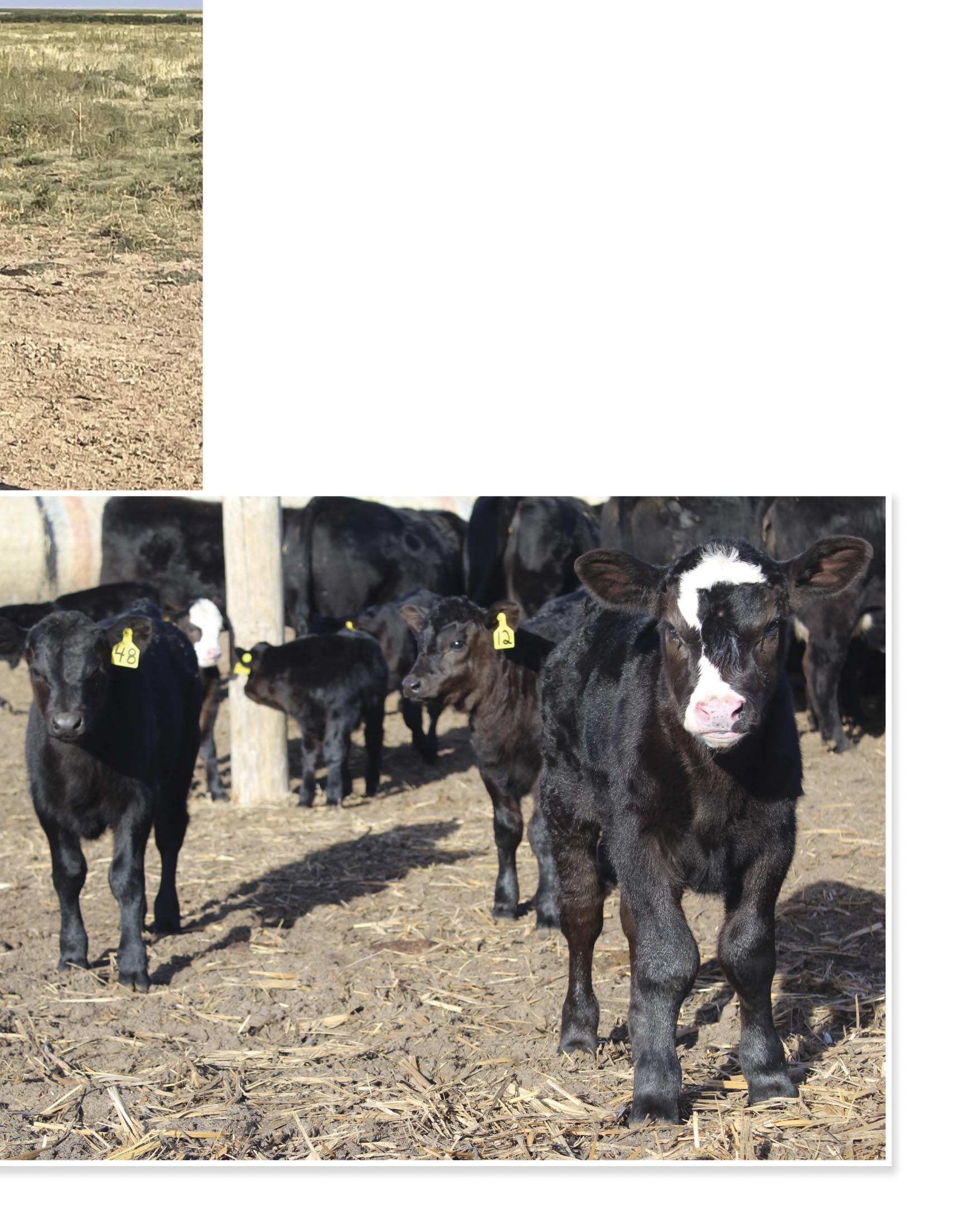

Calf Health and Production

Regardless of the technologies applied after calving to improve weaning weight, nutrition remains the top priority in the breeding female to maintain milk production, become pregnant again, and provide adequate nutrients to her calf prior to processing and vaccination at branding. For vaccination to have its expected outcome, the calf must be on an adequate plane of nutrition. Vaccination with the expected result of improved resistance to disease challenge is largely affected by the length of the calving season. Colostrum that is consumed appropriately at birth aides in disease protection for various diseases for a period of weeks to months after calving but also creates some challenges in timing for vaccinating the calf. A shorter breeding season will obviously shorten the subsequent calving season which results in less age difference between the youngest and oldest calf at first vaccination. When the calves are more similar in age, the maturity of the immune system of the calf group is similar and the interference from maternal colostrum is less impactful in developing good health after vaccination. Recent research has shown that certain aspects of the calf immune system can adequately respond to vaccination even when the protective effects of the cow colostrum are still present. 6 Vaccination against respiratory disease at branding has been shown to improve the booster response to vaccines administered at weaning. 6

Springtime after calving is my favorite time of year. I am convinced the Lord has a sense of humor as He watches the young calves darting through the pasture with their tail up, bucking and kicking as they enjoy life. Here in Ellis County, Oklahoma, we are just doing the best we can not to mess up what He has so wonderfully made.

Resources

1. Pendell, D & Herbel, K. Differences Between High-, Medium-, and Low-Profit Cow-Calf Producers: An Analysis of 2016-2020 Kansas Farm Management Association Cow-Calf Enterprise. Kansas State University Department of Agricultural Economics Extension Publication, December 1, 2021.

2. Larson, D, Musgrave, JA, & Funston, RN. Effect of Estrus Synchronization with a Single Injection of Prostaglandin During Natural Service Mating. University of Nebraska – Lincoln Nebraska Beef Cattle Reports, 1-1-2009.

3. National Animal Health Monitoring System. Beef 2017: Beef Cow-calf Management Practices in the United States, 2017. May 2020.

4. Webb, MJ, et al. Cattle and Carcass Performance, and Life Cycle Assessment of Production Systems Utilizing Additive Combinations of Growth Promotant Technologies. Translational Animal Science, 2020 Nov 21; 4(4).

5. Internal data, Ellis County Animal Hospital.

6. Kirkpatrick, JG, et al. Effect of Age at the Time of Vaccination on Antibody Titers and Feedlot Performance in Beef Calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 2008 Jul 1; 233(1).

Richard and Angie Prather received their DVM degrees from Oklahoma State University in 1986 and 1987. After joining Dr. John Kirkpatrick in mixed animal practice in Shattuck, Oklahoma, they became coowners of Ellis County Animal Hospital in 1990.

Dr. Richard has been involved in dairy and cow-calf practice with an emphasis on production medicine while Dr. Angie tended to small animal medicine and surgery. The Prathers have also been involved with improving cow-calf herd profitability as well as rabies prevention and public health in Zambia, Africa, since 1995. Together, they have hosted over 40 interns and preceptors as they strive to inspire the next generation to provide care and services that promote sustainable agricultural practices through science and evidencebased decisions.