12 minute read

GREAT RANCHES TELL GREAT STORIES: THE BROWNOTTER BUFFALO RANCH

By Darla Dwyer, DVM

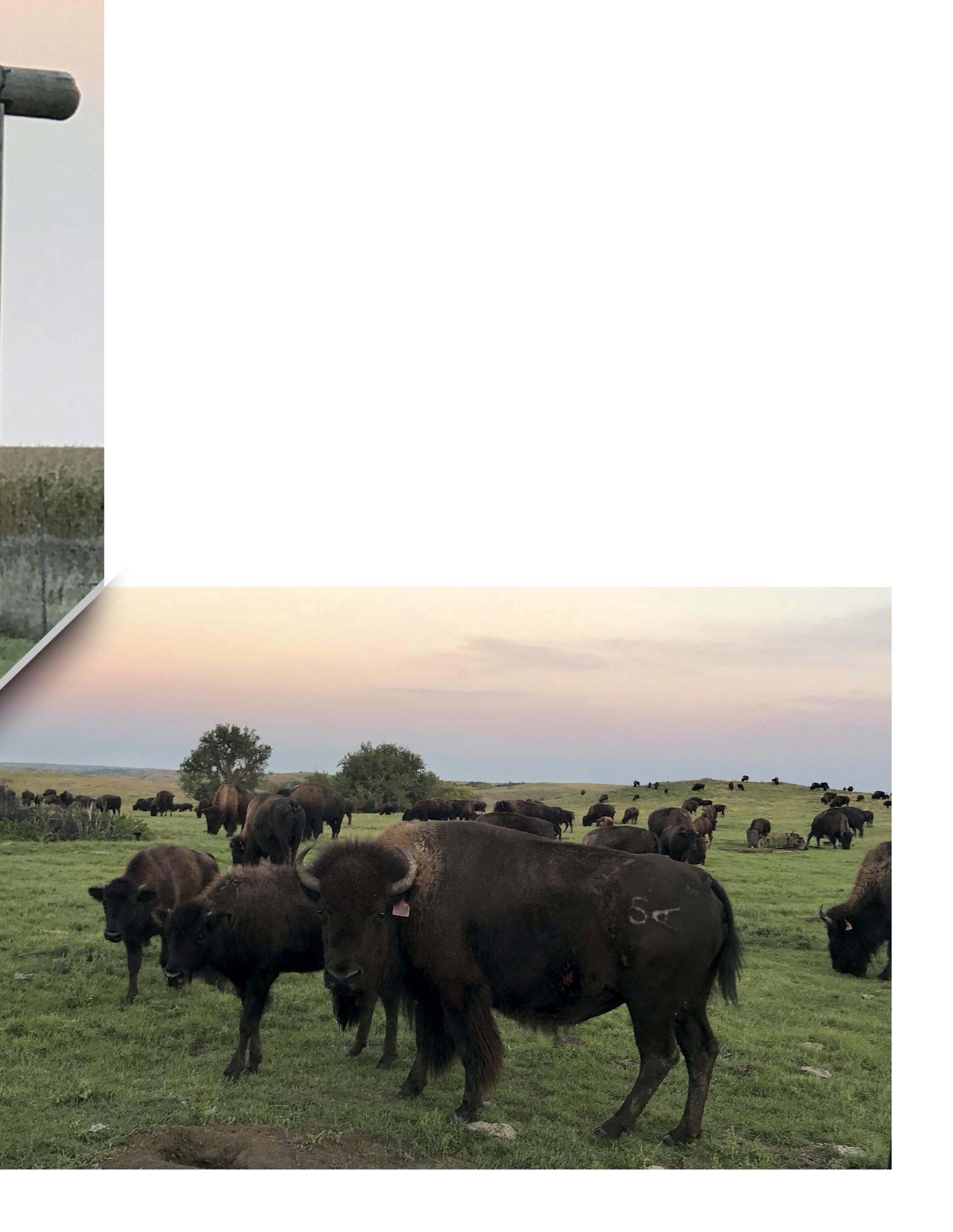

Great ranches can tell great stories; you just have to ask someone that knows them well. In the early 1900s, Ron Brownotter’s grandmother received an allotment of 320 acres from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The land was on the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation near Bullhead, South Dakota. Unlike much of the surrounding land it was never sold but passed down through the family. This land is the origin of the Brownotter Buffalo Ranch, home to the largest Native-American owned buffalo herd in the United States. The journey for the Brownotter family from raising cattle on the original 320 acres of land to a herd of buffalo that utilizes over 20,000 acres is this chapter of the ranch’s story.

Ron Brownotter always knew he would become a rancher. At the age of twelve, he was enrolled in the Johnson O’Malley Program and educated at a boarding school. Even then, he began using everything he had to work toward his dream, buying axes, shovels, fencing pliers, and other tools whenever he could. After graduation, Ron joined the military. His family had a legacy of military service, serving in both World Wars, Vietnam, and Korea. He even had ancestors that fought for their sovereignty at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Ron wanted the type of life they had, and military service was something they all had in common. Originally, he aspired to be an Army Ranger, but the Marine Corps would take him more quickly and his struggle with direction and alcoholism was becoming urgent. “The Marines saved my life with God’s help,” he said. Shortly after joining, he was placed in inpatient alcohol rehabilitation, and after went on to serve 10 years.

After finishing his military service in July of 1992, Ron enrolled in Cal Poly, and started studying Animal Science and Agronomy in August of that year. He chose the area because he could stay with his wife’s family, about 45 minutes away. Ron and his wife, Carol, had already started a family, and owned cattle in South Dakota. Ron commuted from California to the family ranch in South Dakota as often as he could before graduating in 1998. The winter of 1996-1997 proved to be especially challenging, bringing the type of blizzards that are only seen every 100 years or so. That year, Ron spent some extra time on the ranch in addition to his winter break to attempt to save their cow herd. At the time, he only had a two-wheel drive truck and a tractor not well suited for the snow. He fed bags of range cubes by hand in the draws, attempting to pull the herd through the weather before he had to return to Cal Poly for the spring semester. That year his family lost half of his cows to the cold, and they knew they knew something had to change.

While in college, Ron took part in a business class that worked on livestock industry business planning. His group made their plan on how to raise buffalo in South Dakota, but it wasn’t until a few years after the blizzard in the late 90s that his family started to add buffalo to their operation. They started with six buffalo and have gradually phased the cattle out over the last 21 years. In Brownotter’s experience, buffalo are hardier and more suited to the environment in South Dakota because they evolved to fit the environment. Compared to the cattle he previously raised, Ron said they are smarter, travel a lot farther, and are more efficient with native grass. They even have more hair follicles than cattle with a coat that is more like wool, one of their main adaptations. While that hard winter was the obvious driver of the transition, culture and heritage also played a huge role. As a Native American,

Ron knew the importance of buffalo to his people, and this was further demonstrated by research published at that time. Research by Richard Steckel and Joseph M. Prince 1 analyzed data collected in the late 1800s by Franz Boaz. This data indicated that bison dependent tribes were among the tallest humans on earth at the time, an indicator of both physical and societal health. According to Ron, the buffalo are not only a huge part of maintaining Native American culture but are also a crucial part of restoring their health. Buffalo are a central part of tribal ceremonies, but some Native American families have started to add it back into their regular diet in efforts to eat and live healthier. Despite efforts by Indian Health Services, Native Americans still have a greater risk for diabetes than any other ethnic group in the United States. 2 Ron lamented the toll he has seen that take on Native American people through complications, including amputations and kidney disease.

You may have guessed that Ron has a great deal of care for and involvement in his community. He has been involved in the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Government and the Sitting Bull College Board of Trustees, among other roles. As we discussed challenges in his community, many of them mirrored our challenges in rural America: access to fresh and healthy foods, healthcare, education, and jobs. Ron said that jobs in agriculture, casinos, Indian Health Services, and Bureau of Indian Affairs are available on the reservation, but most other opportunities and education for them is something you must leave the reservation for. Although this is a significant barrier, the most pressing challenge and urgent need in his opinion is the need for an inpatient drug and alcohol treatment center. These treatment centers throughout the country are notoriously difficult to be admitted to, and even more difficult to pay for. The location of these centers in combination with restrictions from the state and Medicaid resources that often provide healthcare to people on the reservation have made them almost completely inaccessible to people there. Unfortunately, the need there is still very real. As we discussed this further, Ron described drug and alcohol addiction by comparing it to the parable of the blind men and the elephant in the room. As each person silently identifies the piece they’re touching, the one touching the trunk will suspect a snake while another touching the tusks imagines a spear. He believes the elephant in the room emanated from trauma dating back to relations between settlers and Native Americans, trauma that has been passed down via habits and coping mechanisms for generations. In his experience, when the seed is planted that the elephant is a family problem, only then can people finally start to understand it and work together to heal. He is actively looking for anyone willing to help with or fund local resources for this and hopes for a day when this resource that helped him early in life is available to other Native Americans.

The legacy of the Brownotter Buffalo Ranch is rich with history, dating back before the time of Sitting Bull, who lived less than a mile from the eastern part of the ranch. It tells of conflict between people and how they adapted and overcame through time. The Brownotter family's chapter of the ranch’s history tells of many challenges and lean seasons, but also of triumph, innovation, and growth. It’s part of a larger story in the area of grassroots movements back toward foundational culture and health; one the Brownotters like to share with people who visit for a guided buffalo hunt. Like a true rancher, Ron spoke with great gratitude of the most rewarding things from his part in the tale: God, family, friends, clean and sober living, the importance of integrity, and the many wonderful people in his life. “Do what you love, and never quit,” he said.

Resources

1. Steckel, Richard, H., and Joseph M. Prince. 2001. "Tallest in the World: Native Americans of the Great Plains in the Nineteenth Century." American Economic Review , 91 (1): 287-294.

2. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aian-diabetes/index.html

Dr. Darla Dwyer grew up on a farm in rural northeast Kansas. She graduated with her DVM from Kansas State University in 2013. Darla has spent her career in mixed animal practice in rural Kansas and Nebraska. She enjoys the variety that mixed practice brings, but especially enjoys herd work with cattle and swine. She and her husband currently practice in the panhandle of Nebraska at Pioneer Animal Clinic in Scottsbluff.

WORKING TO REPLACE YOURSELF: 4 STRATEGIES TO CREATING A LEGACY BUSINESS

Dr. Nels Lindberg, Production Animal Consultation

If you are reading this, you are likely involved in or working in some sort of business. It could be a feedyard, ranch, backgrounder, or farming operation, or some combination of all of these. The business you are in is a living breathing thing. It has a life of its own that has ups and downs with good years and tough years. Just like your life, a business is either growing or dying, and there isn’t a lot in between.

Growing may not be rapid growth or even the slow accumulation of ground, cows, or bunk space. It may be that you have a mindset for growth and stewardship of your blessings. Each year you make decisions to ensure facilities are continually upgraded so that in 20 years you do not have a dilapidated, worn-out physical operation. We often think about the hard assets of the business and making sure they are operational for the future, but are we also thinking about the human capital operational future or legacy?

I would like to focus on the growth mindset of creating a legacy operation. To me it is, “How am I going to continue the legacy of this business, so it can go on past me when I am gone?” I hope you have the same mindset for your feedyard, farm, or ranch, because there are real, living, breathing people that depend on that operation to be there beyond you! A veterinary clinic is no different than any agriculture operation. When I bought a veterinary clinic in 2005, my goal was to grow it and ensure that it survived and thrived so it could provide best-in-class veterinary care for years beyond me. What I did not know at that point was truly what it would take and the sacrifices it would require of me to achieve my goal. Through trials and tribulations, failures and successes, I began and continue to learn the process of creating a legacy business.

The following are four strategies to replacing yourself and creating a legacy business. I have learned these strategies over many years as the practice grew and I spent less time at the practice from day to day. It has been a high-speed crash course in creating a legacy, and it could still fail but the pieces are in place. Only time will tell.

1. Creating a culture of “It’s not about me. It’s not about you. It’s about the business.” I remember the first time I said this in a meeting with our clinic team quite a few years ago. I wanted to convey to our team that what we were working towards was not for my personal benefit, but it was for the sustainability of the clinic. It was about deciding to change how we did things for the good of the clinic.

If we do not communicate to our team, they can routinely have the mindset of, “Well, that’s fine. I will do it, but he (or she) is just all about himself (or herself).” To end that line of thinking, just let your people know, “It’s not about me. It’s not about you. It’s about the operation.” Doing this also begins to build a mindset that is less selfcentered and more outward-centered. People begin to think less of what they think is best and instead ask, “What do we all think is best?”

2. Working to replace yourself as you lead an operation will be difficult in the beginning, as you must first understand your role. Over time, you get pretty good at what you are doing by making enough mistakes. You begin to understand how the different seasons go, the ebbs and flows, and the do’s and don’ts of your operation. Your mindset will move from being reactive to anticipating. Then as time goes on, you can share that with your team to help them anticipate what is coming next.

Over time, we often get comfortable, as we love the work we do, we like that we have full control, our souls are fulfilled, and so we don’t look beyond that. However, if we are to create a legacy business, we must be able to humbly look forward and let our ego go to work to replace ourselves. Letting go of the control and letting go of our ego, my friends, is the toughest part of the process. If we do not do it, we are writing a recipe for some sort of failure or at least limiting the full capacity of success that could be seen after we are gone. We have to be looking to replace ourselves and grooming the next person in line, similar to the “next man up” mentality of any successful football team.

3. Intentionally turning the reins over to our successor is the next step. This isn’t a one-time grand event, where you say, “Now it’s yours. You’ve been named the leader. Take it and run!” Successfully turning over the reins is a methodical process that can take years. You may not have years, but for best long-term sustainable outcomes, years is best. You led an operation for 10, 20, or 30 years, and you cannot expect to pass over all that knowledge on in a month, 6 months, or even a year. Your knowledge was built up over decades, through repeated seasonal events and screw-ups, and then more screw-ups.

The true goal is to take a person that meets your behavioral value set, personal code of conduct, and core values, and coach them into a legacy leader over time. Metaphorically, we start by showing them how to brush the horse before saddling the horse. As more time passes, we show them how to successfully pad the horse, saddle the horse, ride the horse, and so on. You get the picture. It is a process of slowly but surely giving them more responsibility and decision-making authority. We coach them every step of the way, talking to them and asking them, “What do you think?” We ask them to be patient, humble, and respectful and to ask us the same question, “What do you think?”

Our biggest challenge in this process, as the leader, is letting go of the control and letting go of our ego. We have been successful at what we have done so we sometimes think “I don’t need their input!” or We know what we are doing!” or “They just need to do what they are told and stop asking questions!”. But we must remember they have great ideas, and some of them may be better than ours! The key is for both parties to be open minded, able to communicate through difficult or crucial decisions, and focused on doing what is best for the operation rather than fulfilling personal agendas, ideas, or biases.

The biggest challenge for the “next man up” is patience and respect. They must relax and be patient in the long process because replacing a leader takes time. It is an emotional journey for the leader because they are “giving up their baby”. They can show respect by asking the leader, “What do you think?” when they face difficult decisions or new challenges.

Ultimately, successful transitions require the leader to lose their ego and be willing to give up pieces of control over time and the successor to be patient and respectful by routinely asking the leader for their thoughts and input.

4. Being an advisor is the final step after you have accomplished the prior steps in this journey. By this point in the process of replacing yourself, you have done your homework, you have done the work, and you can be 100% absent. The operation not only goes on successfully but often more successfully than when you were in charge! The reins have been completely handed over and the operation is running like they are competing at the Kentucky Derby. You are simply the cheerleader, the consultant, or the chair of the board. Your job is to be there some, sit back and absorb what is going on (sometimes up close, sometimes from a distance), offer advice as you see big waves coming, be counsel when called upon, give crucial advice if you see it is needed, and be the cheerleader.

This article does not do this whole process justice but provides a glimpse into an area of opportunity I see for many operations and businesses. As I went through this process of replacing myself at my clinic, I made a lot of mistakes and experienced a wide range of emotions. Throughout the process, I continued to reflect on and then verbalize it.

Again, the toughest challenge for a leader replacing himself or herself is giving up the ego and the control. This can eat a person alive, but if you truly have the mindset of creating a legacy operation that goes on after you are gone, you must do this over time. We can all think of operations that did not do this and did not survive. This is a brutal question, but is that what you want? I don’t think so! If it is not what you want, then please take these steps! If you want to dig more into the process, please reach out to me. I would be glad to help you because we need your operation to be a legacy operation!