11 minute read

PREPARING FOR CALVING

By David Rethorst, DVM, Beef Health Solutions, Veterinary Applied Systems Thinking, Production Animal Consultation

As we think about preparing for the upcoming calving season, we must remember that calving is an important step in the creation of value in the beef industry. Creating value (profit) for beef producers is the art of managing the resources (land and cattle) that have been entrusted to our care in a manner that meets the wants and needs of the consumer (production of a product, beef, that they want and are willing to pay for). Today’s consumers, at least the vocal ones, are concerned about how we care for cattle, how we use antibiotics, and the impact beef production has on the environment. In other words, we need to practice good stewardship.

Stewardship is the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one’s care. What a powerful definition! In the conversion of cellulose to high quality red meat protein, aka, beef production, we have been entrusted with not only the careful and responsible management of our beef animals but also that of the air, water, soil, and grass that we utilize in the production of beef. Each time an animal in our care dies, not only is that animal’s life wasted, but the natural resources that were utilized in getting the animal raised to that point in its life are wasted. The grass and water it took to get the cow pregnant and to carry the calf to term are wasted along with the resources used during the calf’s life. A certain amount of sick and dead cattle are inevitable in the production of beef. However, each sick or dead animal should cause us to ask ourselves if we could improve our stewardship practices.

There is ample opportunity to reduce the death loss, reduce the waste, and put more steaks, roasts, and hamburgers in the meat counter without increasing the size of the cowherd in the United States. The weaned calf crop in this country averages in the eighty percent range and the opportunity exists to increase the beef supply through improving reproductive efficiency rather than increasing cow numbers. An even lower hanging fruit is reducing the weaning-associated sickness and death loss caused by respiratory disease.

The key for these changes is to make sure that we are performing basic animal husbandry practices very, very well rather than incorporating more vaccine and antibiotics. These practices include: body condition score (BCS), 5-5.5 for cows and 5.5-6 for heifers, as they go into calving. These condition scores indicate that the dams have adequate energy intake during gestation. Cows whose energy is restricted in late gestation tend to give birth to calves with light birthweight, low vigor, and low ability to survive.1 These calves are more susceptible to neonatal scours and have a higher mortality from birth to slaughter. In another study, calves born to thin cows are slower to nurse, have lower IgG and IgM levels, and have reduced thermogenesis.2 Cows that are in adequate BCS going into calving have the necessary brown fat in the colostrum to serve as a neonatal energy source and will have the necessary condition for rebreeding in a timely manner.

Extensive fetal programming work has been done in the last twenty years demonstrating the importance of protein intake during the third trimester of pregnancy. A study at the University of Nebraska showed that the steer calves out of cows that were supplemented with protein while grazing dormant pastures outperformed steers born to unsupplemented cows in the feedyard.3 The same study demonstrated the yearling reproductive performance of heifer calves born to supplemented dams was significantly better than that of heifers whose dams were not supplemented. Two studies at New Mexico State University (NMSU) demonstrated that protein supplementation strategies during the third trimester of pregnancy impacts feedyard BRD morbidity and mortality.4,5 One set of cows received supplemental protein 3 times a week (3X), another group received free choice protein supplement (CONT), and the third received protein when inclement weather was anticipated (VAR). The trace mineral for the free choice group

“Because nutrition matters.” Those three words very appropriately summarize the importance of nutrition to the lifetime health and performance of beef cattle. Gestational nutrition will serve as the foundation for this discussion as protein, energy, vitamins, and trace minerals during pregnancy are necessary on a timely basis in order for cattle to perform as expected.

As we think about energy in the pregnant cow, it is essential that the cows are maintained in a near optimal was incorporated into the protein while the other two sets of cows were on free choice mineral. Figure 1 is a summary of the health performance of the steers from these studies in the feedyard.

Given the transfer of trace minerals from dam to fetus that occurs in the third trimester and the importance of this transfer to immunocompetence,6,7 the question that bears asking in these two studies should be, “Are the differences seen in these studies due to protein supplementation, trace mineral supplementation, or a combination of the two?” The cows in the free choice protein group received both the protein and trace mineral they were supposed to since the trace mineral was incorporated into the protein supplement while the cows in the other two groups were offered free choice mineral.

The levels of trace minerals that are fed during gestation do not have the impact on calf vigor that protein and energy do.2 However, there is evidence that the trace minerals will impact immune system function.8 Copper, zinc, and selenium are the primary trace minerals of interest when immune function is discussed. When reproduction is considered, manganese should be evaluated. Trace minerals are transferred from the dam to the fetus during late gestation to provide the very high fetal liver stores of trace minerals that are required for proper immune function the first 50-60 days of life.

Nearly all discussions of colostrum focus on the antibodies that are transferred from the dam to the newborn calf via colostrum as this is an important factor in determining the pre-weaning health and performance of beef calves. Calves in a study at Meat Animal Research Center (MARC) that did not receive adequate colostrum were 6.4 times likely to experience neonatal illness, 3.2 times more likely to become ill prior to weaning, and 5.4 times more likely to die prior to weaning when compared to calves receiving adequate colostrum.9 Calves that became ill in the first 28 days of life were 35 pounds lighter at weaning than the healthy calves. In the feedyard, calves receiving adequate colostrum were 3 times less likely to become ill and 3.1 less likely to experience respiratory disease than the calves receiving inadequate colostrum. In a second MARC study, calves receiving inadequate colostrum were 1.6 times likely to become ill and 2.7 times more likely to die prior to weaning.10 Calves receiving adequate colostrum were 7 pounds heavier at weaning. No differences were seen in the feedyard in this study.

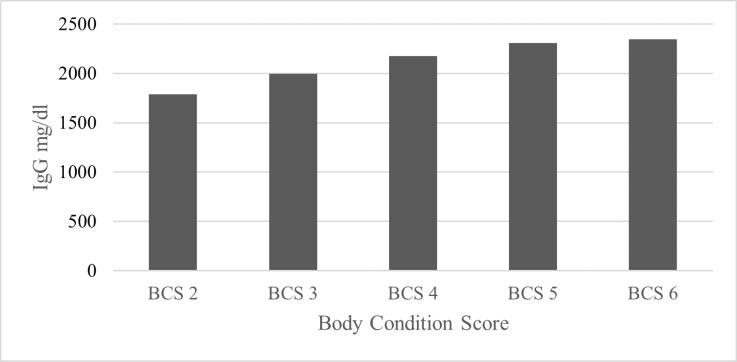

Fat and leukocytes (primarily lymphocytes) are other components of colostrum that are essential for the neonate. Colostral fat serves as a nutritional energy source to help the neonate thermo-regulate, especially in the first hours of life. Colostrum plays an integral role in supplying neonatal energy needs and this role has been described to be of equal importance to colostrum’s role in transferring passive immunity to the newborn.11 Calves born to prepartum protein restricted two-year-old beef heifers had lower heat production as a neonate than calves from heifers fed adequate protein prepartum.12 In a related study, body condition score (BCS) of two-yearold heifers was directly related to immunoglobulin absorption by their calves.12

Colostral leukocytes are absorbed by the neonatal gastrointestinal tract and can influence the immune function of the calf.13 The impact on neonatal morbidity and mortality associated with this leukocyte absorption has not been studied. However, one could hypothesize that if the lymphocytes of the dam are primed with viral vaccine antigens prior to colostrogenesis, the viral immunity of the calf could be enhanced early in life by the colostral lymphocytes.

Calves are born with very low Vitamin A and Vitamin E and thus rely on colostrum as the primary source of these fat-soluble vitamins. Both of these vitamins are necessary for optimum immune function as well as other tissue functions. Vitamin A deficiency has been shown to impair the viral immune response in neonatal calves.14 Deficiency of this vitamin causes damage to the epithelium and allows viruses and bacteria to invade.15

Vitamin A deficiency has become more prevalent in recent years primarily due to a fire in Germany that destroyed the only plant that manufactures feed grade Vitamin A, the increased use of distillers grain that is relatively low in Vitamin A content, and ongoing droughts which affect forage quality.

In an older study at the University of Idaho looking at weak calf syndrome, protein supplementation in late pregnancy was shown to increase the amount of colostrum that was absorbed by calves born to two-yearold heifers.16

A closing thought on colostrum management is to encourage producers to, if at all possible, wait until the newborn calf is dry before tagging, weighing, or giving vaccines. This allows for better bonding between the dam and the neonate, which in turn encourages improved intake of colostrum. Discussions about colostrum focus on the immunoglobulin transfer that occurs, but it is essential that fat content, vitamin content, and leukocyte content are considered as well.

Environmental management includes windbreaks for cows during pregnancy, bedding and windbreaks during calving, and timing of calving season. Windbreaks will aid in maintaining body condition by reducing calories needed for basic maintenance. Bedding will keep calves warmer, reducing stress and keeping the immune system more functional. One reason some producers move to late spring calving is to reduce stress on calves, thus a healthier calf. Another example of environmental management is the use of the Sandhills Calving System in order to reduce the occurrence of calf scours. The basic premise of this system is to move the cows that have not calved to a new calving area approximately every two weeks allowing the newest calves to be born on clean ground.

Now is a good time to make sure your calving equipment is where you think it is and in good working order. Remember that calf jack that did not work correctly on the last calf you pulled last spring? Now is the time to fix it rather than when that first heifer OB is in the headgate. Is that the same headgate that would not consistently hold a heifer last spring? Let’s get those repaired or replaced now. Make sure the OB straps or chains are clean and where they are supposed to be. Disinfectant, soap, OB lube, towels, and OB sleeves should be checked on now also. Spending some time checking on these now will save a great deal of anxiety once calving starts.

During stage I of labor, uterine contractions begin that rotate the calf to an upright position, dilate the cervix, and allow the water bag to appear. Once the water bag breaks, stage I is complete. This usually takes 2-6 hours. Once the water bag breaks, stage II of labor or the actual delivery of the calf has begun. Mature cows should complete this stage within an hour while heifers may take 12 hours. If they are not progressing within an hour, the time to intervene is now. Catch them, get them in a headgate, and get an arm in them to determine what is going on. Once the calf is delivered, stage III of labor, the passing of the placenta, begins. This should be completed in a matter of 2-8 hours.

Please do not try to “look a calf” out of a cow. One of my pet peeves when I was in practice was when a client would call at 5:30 PM as I was leaving for the day and say they had noticed a heifer calving at 7:00 AM that morning but she still hadn’t calved and ask if they could bring her in right away. Invariably, the result was a dead calf and I went from the asset side of the ledger sheet to the liability side when I did not have any control of the situation. With weaned calves being worth $900 to $1100, it just makes sense to intervene early so the result is a live calf.

Healthy calves are the result of doing even the small details extraordinarily well. This creates value for the cow-calf producer because the cattle have a more functional immune system which is something the feedyard industry wants and is becoming more willing to pay for.

All segments of the beef industry are able to create value by reducing labor costs involved in treating sick animals, improved performance, and reduced death loss. This reduction in use of antibiotics and corresponding reduction in the chance of antibiotic resistance are both good in the eyes of our consumers. This approach reduces waste and allows for more efficient use of our natural resources. It is good stewardship. It is sustainable. It creates value for the producer and the consumer.

Portions of this article are excerpted from:

• Rethorst, D. Creating Value for Producers, Consumers. Joplin Regional Stockyards Cattlemen’s News, 2016; October: 8-9.

• Rethorst, D. Flippin’ the iceberg: A systems thinking approach to immunology and vaccination protocols in beef cow-calf systems. American Association of Bovine Practitioners Proceedings of the Annual Conference, 2021; 90-97.

Resources

1. Corah LR. Understanding basic mineral and vitamin nutrition, in Proceedings: The Range Beef Cow Symposium XIV, 1995.

2. Corah, LR. Effect of pre-calving energy, protein and trace minerals on calf vigor and survival. Agri-Practice, 1994; 15:9.

3. Funston, R, et al. Effects of maternal nutrition on conceptus growth and offspring performance: Implications for beef cattle production. Journal of Animal Science, 2010; 88:E205-E215.

4. Mulliniks, JT, et al. Supplementation strategy during late gestation alters steer progeny health in the feedlot without affecting cow performance. Journal of Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2013; 185:126-132.

5. Mulliniks, JT, et al. Winter protein management during late gestation alters range cow and steer progeny performance. Journal of Animal Science, 2012; 90:5099-5106.

6. Van Saun, RJ. Fetal mineral metabolism and its impact on neonatal health and performance. Proceedings: American College Veterinary Internal Medicine, 2003.

7. Van Saun, RJ. Importance of transition cow mineral and vitamin nutrition for calf development and survival. Proceedings: Danish Bovine Practitioner Seminar, 2007.

8. Marques, RS, et al. Effects of organic or inorganic Co, Cu, Mn, and Zn supplementation to late-gestating beef cows on productive and physiological responses of the offspring. Journal of Animal Science, 2016; 94(3):1215-1226.

9. Wittum TE, et al. Passive immune status at postpartum hour 24 and long-term health and performance of calves. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 1995; 56:1149-1154.

10. Dewell RD, et al. Association of neonatal serum immunoglobulin G1 concentration with health and performance in beef calves. Journal American Veterinary Medical Association, 2006; 228:914-921.

11. Carsten GE. Cold thermoregulation in the newborn calf. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 1994; 10:69-106.

12. Odde KG. Survival of the neonatal calf. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 1988; 4:501-508.

13. Perino LJ, et al. Immunization of the beef cow and its influence on fetal and neonatal calf health. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 1994; 10:15-34.

14. McGill, J. Vitamin A deficiency impairs the immune response to intranasal vaccination and RSV infection in neonatal calves. Scientific Reports, 2019; 9:15157.

15. Carroll, JA, et al. Influence of stress and nutrition on cattle immunity. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, 2007; 23:105-149.

16. Blecha, F, et al. Effects of prepartum protein restriction in the beef cow on immunoglobulin content in the blood and colostral whey and subsequent immunoglobulin absorption by the neonatal calf. Journal of Animal Science, 1981; 53(5):1174-1180.

A native of southwest Kansas, Dr. David Rethorst attended Kansas State University where he received his DVM in 1978. He spent 35 years in primarily beef cattle practice in south central Nebraska and northwest Kansas before accepting a position as the Director of Outreach for the Beef Cattle Institute at Kansas State University in 2013. Returning to private practice in 2017, he is currently mentoring young veterinarians in three practices in addition to serving a clientele of beef producers. His preventative approach focuses on basic animal husbandry, especially nutrition in the cow herd, rather than more vaccine and more antibiotic.