*

*

FOLLOW US twitter.com/Mix_Magazine facebook/MixMagazine instagram/mixonlineig

CONTENT

Content Directors Tom Kenny, thomas.kenny@futurenet.com

Clive Young, clive.young@futurenet.com

Senior Content Producer Steve Harvey, sharvey.prosound@gmail.com

Technology Editor, Studio Mike Levine, techeditormike@gmail.com

Technology Editor, Live Steve La Cerra, stevelacerra@verizon.net

Contributors: Craig Anderton, Barbara Schultz, Barry Rudolph, Michael Cooper, Robyn Flans, Rob Tavaglione, Jennifer Walden

Production Manager Nicole Schilling

Design Directors Will Shum and Lisa McIntosh

ADVERTISING SALES

Managing Vice President of Sales, B2B Tech Adam Goldstein, adam.goldstein@futurenet.com, 212-378-0465

Janis Crowley, janis.crowley@futurenet.com

Debbie Rosenthal, debbie.rosenthal@futurenet.com

Zahra Majma, zahra.majma@futurenet.com

SUBSCRIBER CUSTOMER SERVICE

To subscribe, change your address, or check on your current account status, go to mixonline.com and click on About Us, email futureplc@computerfulfillment.com, call 888-266-5828, or write P.O. Box 8518, Lowell, MA 01853.

LICENSING/REPRINTS/PERMISSIONS

Mix is available for licensing.

Contact the Licensing team to discuss partnership opportunities. Head of Print Licensing: Rachel Shaw, licensing@futurenet.com

MANAGEMENT

SVP, MD, B2B Amanda Darman-Allen VP, Global Head of Content, B2B Carmel King MD, Content, AV Anthony Savona

VP, Head of US Sales, B2B Tom Sikes

Managing VP of Sales, B2B Tech Adam Goldstein VP, Global Head of Strategy & Ops, B2B Allison Markert, VP, Product & Marketing, B2B Scott Lowe Head of Production US & UK Mark Constance Head of Design, B2B Nicole Cobban

Sometime back in the mid-2000s, my brother-in-law Rick turned me on to a book called How the Irish Saved Western Civilization, by the best-selling author Thomas Cahill. It’s a fun read as far as popular, historical nonfiction goes, and though its claims may be overstated at times (surely there were others working on the same thing) and its interpretations may skew in favor of St. Patrick, St. Augustine and others, its basic premise is sound. And that premise is this:

When the Roman Empire was falling, ushering in the Dark Ages, education, and most certainly the recording and preservation of knowledge, fell out of fashion for the next 600 years or so. Seeing this, the new monastic orders of Ireland, based on a foundation of education and the promotion of knowledge, began using their contacts on the Continent to smuggle every piece of text they could find to Ireland. There, over the next half a millennium, from the Isle of Man in the east to the shores of Galway in the west, monks and scribes began copying those books and scrolls—over and over and over. That’s how the Irish saved Western civilization

Now, in the past few weeks, a couple of things came across my desk that made me think of those monks in an entirely new light. Maybe, I thought, they loved their work, excited to be a part of the world’s first large-scale information backup. Maybe they realized that the simple physical storage medium of ink on paper was backward-compatible to the Rosetta Stone and early pictograms, and forward-compatible to the end of the human race, as long as it was properly preserved and then transferred with care to whatever distribution and storage systems might appear in the future.

The first item that made me rethink the monks was the news story from late-June that Paramount had quietly shuttered the MTVnews.com website, only to have it blow up into a major story. Where did the 30 years of unique music news, journalism, photography and videos go? Was it gone forever? Writers and personalities for the site were enraged and went public, futurist pundits made comments, other music sites chimed in and we’re still in the middle of the fallout. In 2019, MySpace was back in the news with something similar, admitting that it had irreversibly lost 12 years worth of music and photos, affecting 14.2 million users and 53 million tracks. Just gone.

The sad truth is that situations like this occur daily across the media and entertainment industries, admittedly on a smaller scale. A small-town newspaper shuts down its digital archive to cut costs and can no longer find its physical assets after the new corporate owner takes over storage responsibilities. An early-Nineties regional punk music zine might have appeared very early on in the internet’s development, but unless you saved a physical copy of that

particular issue, you are unlikely to find anything today.

The second thing that made me rethink the monks was reading this month’s feature by senior writer Steve Harvey, “It’s Time to Talk About Hard Drives,” the third in a series of recent pieces on Iron Mountain’s technological efforts surrounding the storage, preservation and archiving of music and media assets. It was a bit shocking, but not too surprising, to learn that during a recent inventory survey of media assets, they found that 20 percent of hard disk drives were unreadable. It’s not Iron Mountain’s fault; the drives were brought in that way and there’s only so much they can do if a disk doesn’t spin or a root system file is corrupted. If a song from the mid-to-late ’90s was recorded, mixed, mastered and distributed all-digital, never touching a physical medium, there’s no guarantee that it will play back in 2024, or that the assets will ever be recovered.

Robert Koszela, director of North American Studio Operations at Iron Mountain, has seen it all in nearly 30 years as a media archivist, from issues with tape through today’s most up-to-date preservation and restoration technologies. He’s not up late at night worrying about doomsday scenarios, and he doesn’t believe the sky is falling—so when he issues an industry-wide call for awareness and action regarding digital storage and playback, it’s best to pay attention

I’m no Chicken Little either, and by no means am I advocating a return to paper storage and photos that are picked up at a lab. I believe that with a little digital and physical sleuthing, many assets can be recovered.

But it’s also true that the vast majority of people today suffer from a false sense of security that when they hit Save or Send that information is digital and now available forever. That’s simply not true. Talk of the Digital Dark Ages first popped up in the mid-’90s to describe the counterintuitive concept that with all the digital technologies available today, and with storage increasing in capacity and decreasing in price year after year, we are actually losing large chunks of the historical record on a daily basis. That makes no sense, yet it’s true.

At the end of the day, all you can really do is pay attention to your assets and do your best to future-proof them for all formats yet to come. Then backup, backup, backup. If that proves too time-consuming, you might try asking a monk for help. They have a pretty good track record.

Tom Kenny Co-Editor

By Steve Harvey

As governments worldwide assess the implications of artificial intelligence and work on policies to ensure that the technology is used positively, 50 music industry bodies a nnounced in June that they had thrown their support behind “Principles for Music Creation With AI.” Barely a day later, the Recording Industry Association of America filed two copyright infringement cases against AI tech companies Suno and Udio.

“Principles for Music Creation With AI,” a set of clarifying statements introduced by Roland Corporation and Universal Music Group in March, offers a shared philosophy around the application of AI in music creation. To promote greater adoption within the music industry, the organizations are strongly encouraging additional organizations worldwide—including manufacturers, educators, associations, labels and others—to officially endorse these principles under the AI for Music banner.

Among the organizations endorsing the principles are NAMM, Sydney University, BandLab Technologies, Splice, Native Instruments, Focusrite, Output, Beatport, Waves, Soundful, Landr, Eventide, GPU Audio, and others. The coalition states that it is committed to adhering to ethical industry standards that protect human creativity, while also exploring innovative ways for artificial intelligence to empower and support artists, according to a joint statement.

The core principles stress the inseparable link between humanity and music, stating that technology should support and amplify human creativity. According to an AI for Music statement, “We believe that transparency is essential to responsible and trustworthy AI.”

The statement also reads: “As we usher in a new era of music creation, the emergence of AI-powered tools offers exciting opportunities but also presents significant risks. Therefore, a critical need to manage their impact responsibly is required. The ‘Principles for Music Creation With AI’ were developed to address these challenges, establishing clear guidelines

that emphasize the need for strong internal governance and broad industry support. By adhering to these principles, the music industry can protect artistic integrity while harnessing AI’s transformative potential.”

Separately, UMG recently announced a strategic agreement with AI tech company SoundLabs, led by producer/artist BT, that will enable UMG artists and producers to create vocal models of the label’s artists. A new plug-in under development will reportedly allow users to do voice-to-voice, voice-to-instrument and speechto-singing transformations, as well as language transposition and more.

In the announcement, Chris Horton, SVP, strategic technology, at UMG, commented, “UMG strives to keep artists at the center of our AI strategy so that technology is used in service of artistry, rather than the other way around.”

The RIAA’s filings are based on the mass infringement of copyrighted sound recordings copied and exploited without permission by the two multi-million-dollar music generation services. The plaintiffs in the cases are music companies that hold rights to sound recordings infringed by Suno and Udio, including Sony

Music Entertainment, UMG Recordings and Warner Records. The claims cover recordings by artists of multiple genres, styles and eras, according to a statement from the RIAA.

“The music community has embraced AI, and we are already partnering and collaborating with responsible developers to build sustainable AI tools centered on human creativity that put artists and songwriters in charge,” said RIAA Chairman and CEO Mitch Glazier. “Unlicensed services like Suno and Udio that claim it’s ‘fair’ to copy an artist’s life’s work and exploit it for their own profit without consent or pay set back the promise of genuinely innovative AI for us all.”

The cases seek: (1) declarations that the two services infringed plaintiffs’ copyrighted sound recordings; (2) injunctions barring the services from infringing plaintiffs’ copyrighted sound recordings in the future; and (3) damages for the infringements that have already occurred.

RIAA chief legal officer Ken Doroshow added, “These lawsuits are necessary to reinforce the most basic rules of the road for the responsible, ethical and lawful development of generative AI systems and to bring Suno’s and Udio’s blatant infringement to an end.” n

By Clive Young

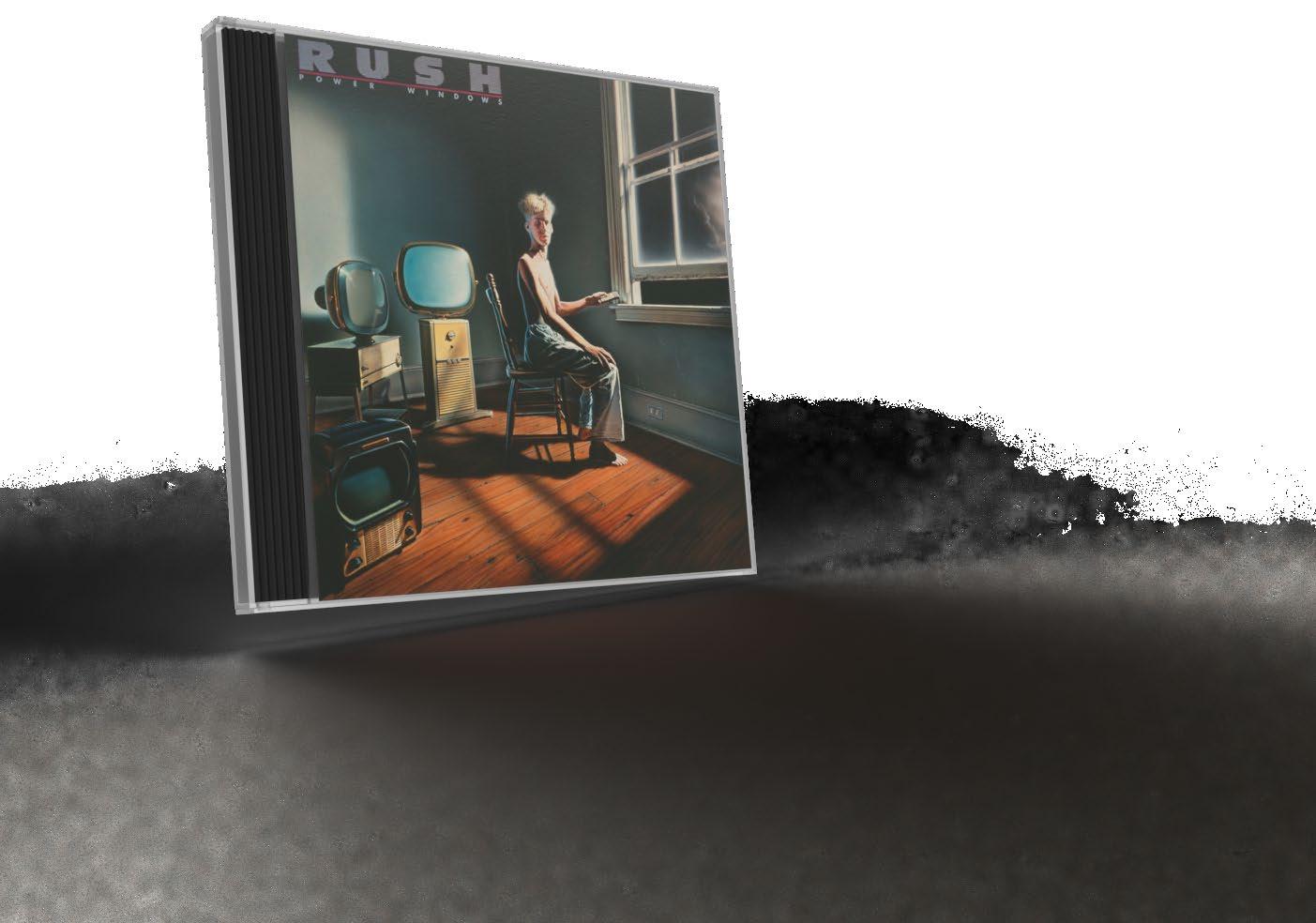

Ahitmaker for decades, Nashville-based producer Peter Collins died at home in June. According to published reports, Collins passed following an extended battle with pancreatic cancer.

Over the course of a nearly 40-year career in the production chair, Collins helped artists craft hit albums and singles across a wide variety of genres, working with artists as varied as Rush, Tom Jones, Musical Youth, Indigo Girls, Suicidal Tendencies, Rick Astley and more. He was 73.

Born January 14, 1951, in Reading, England, Collins first broke into the music industry as a member and producer of UK one-off pop act, Madison in 1976. After the trio failed to chart, he formed a production company with Pete Waterman (who went on to co-form the late1980s era-defining pop production team Stock Aitken Waterman), before going on to hit his stride as a hitmaker during the early 1980s, shepherding hits for Musical Youth (“Pass the Dutchie”), The Belle Stars (“Sign of the Times”), Tracy Ullman (“They Don’t Know”) and multiple UK smashes with Nik Kershaw.

Collins moved to Canada in 1985 to produce Rush’s Power Windows (1985) and Hold Your Fire (1987) albums—the first of four with the trio—and with that success, began to focus more on hard rock and metal, going on to produce the likes of Billy Squire, Gary Moore, Queensrÿche, Bon Jovi, Suicidal Tendencies and Alice Cooper over the next decade. Shifting to the singer/songwriter revival of the later 1990s, he oversaw hit albums by

Jewel, Shawn Mullins, Lisa Loeb, Indigo Girls, Nancy Griffith, Beth Nielsen Chapman and others. During this era, he also began a long association with The Brian Setzer Orchestra, ultimately producing four albums for the swing revival act—a move that paved the way for his last production credit, producing the Setzer-led Stray Cats reunion album 40, released in 2019.

Speaking with Mix in its December 1998 issue, Collins discussed his production methods over the years, noting, “I’m a huge fan of pre-production…. I try to catch the early performances. They don’t get better. They usually get worse. It’s important to catch the drummer while they’re fresh and not ‘thinking.’ Then you just get a natural flow of performance.” n

By Steve Harvey

Grammy-winning, Jamaica-born, Canadian producer and songwriter Boi-1da got his initial break while still in his late teens, producing several songs on a number of Drake’s early mixtapes. Since then, he’s collaborated with some of the biggest names in the business, including Eminem, with whom he had his first Billboard Hot 100 Number One, in 2010, and Rihanna, whose “Work,” featuring Drake, brought him his second chart-topper in 2016. The hits have kept on coming as his production credits have grown to include a long list of hip-hop greats, including Kendrick Lamar, Nicki Minaj, Kanye West, Juice Wrld and others.

Boi-1da, who grew up listening to Jamaican music and is much in demand for his dancehall sound, travels a lot, says studio designer Martin Pilchner of Pilchner Schoustal International Inc. However, the producer also values his time at home, so he approached Pilchner to design a production suite in his house comparable to the commercial facilities in which he regularly works. The new studio, filling roughly 420 square feet, is tucked away off the family room on the lower level of his house in Pickering, Ontario, just east of Toronto. Enabling him to produce studio-quality beats and tracks at home while also offering plenty of space for collaborators, the room is intended to be the epitome of the modern production workflow.

“These guys don’t work on consoles,” Pilchner says. “They work on laptops, and a lot of times

they’re all working together at the same time on different laptops.”

The studio design includes numerous ports around the studio, which also features a couple of couches at the rear of the room, into which collaborators can plug their computers. The setup enables anyone in the room to access the monitoring system and to transfer files to a centralized Pro Tools HDX system, which is interfaced via an Antelope Audio Galaxy. Revolution Custom Shop in Toronto designed the technical system, Pilchner reports. “Everybody

can create all the different musical components, then consolidate them in one place and mix in Pro Tools.”

With no mixing console or producer’s desk in the room, to further encourage the collaborative process, Pilchner hit on the idea of configuring the long studio desk to curve toward the front wall at each end, the reverse of the more traditional design. “If you are sitting in the middle and collaborators are sitting on the left and right side, they can see each other and interact with each other more easily,” he says of

the novel solution.

Of course, configuring the workspace at the front of the room for three people to sit side by side by side also demanded a wider, controlled sweet spot. “It was all about trying to get the mix window as wide as possible,” Pilcher confirms, a goal that was made slightly easier by the length of the room. “Then it was just a matter of getting rid of all the unwanted sidewall reflections to create the opportunity for consistency across the left and right side of the desk, which worked out pretty well.”

There is a large Augspurger in-wall main monitor system comprising Duo 12MF and Sub 212 units, something of a standard feature in today’s rap and modern pop production rooms. The studio also features a Genelec 7.1.4 monitoring setup. “The front channels of the Genelec Atmos system sit on motorized stands that lift up and down,” Pilchner explains. “If they want to work on the Genelecs, they press a button and they pop up.” When the room is configured for Dolby Atmos projects, the Augspurger subwoofers switch to handle the low-frequency extension. A Grace Design m908 provides monitor control, processing and management.

The controlled reflection geometry of the production space provides a smooth and uniform response for the Augspurger stereo and the Genelec Atmos systems, he continues. “The ceiling in the space wasn’t super-generous, so we had to eliminate the ceiling refractions. The front part of the ceiling is done with a fairly thick absorber that has a PG [perforated] finish. The back half of the room is all low-frequency trapping, but every other surface is diffusive; we built walnut diffusors with niches in them that light up.”

Because the space is well-damped, Pilchner says, Boi-1da can cut studio-quality vocals in the room. The racks at the front of the room house the expected outboard, including a vocal chain featuring a Tube-Tech CL 1B compressor and choice of AMS Neve 1073 or 1084 mic pre/EQs for use with the Sony C800 G PAC microphone. API 500 Series modules and an SPL MixDream summing mixer round out the processing complement.

Two windows in the rear wall of the room provide natural light. Those windows, together with the glass in the entranceway to the studio from the family room, are fitted with LCD glass that turns opaque for privacy at the touch of a button. n

By Clive Young

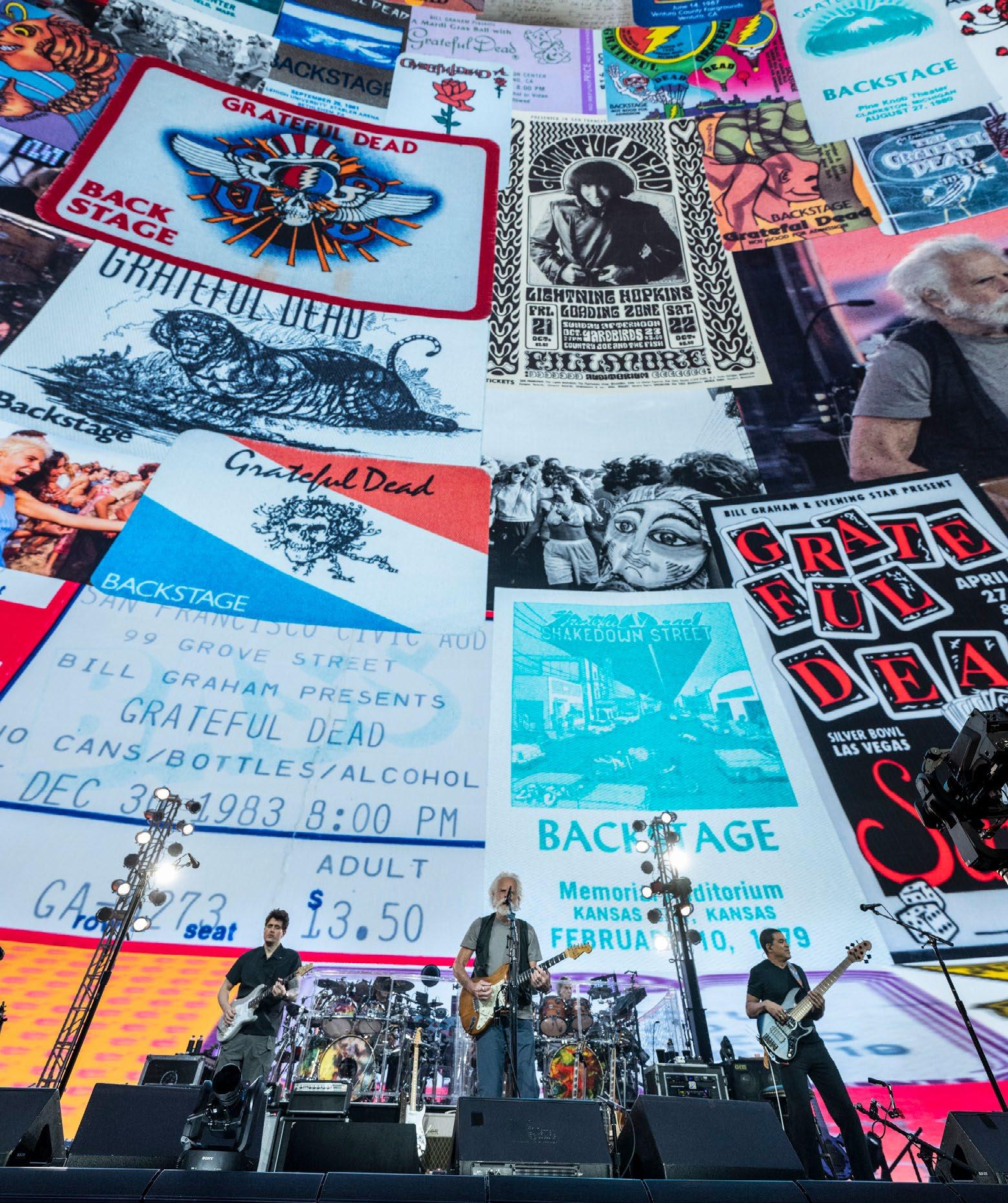

Since opening last fall, Sphere in Las Vegas has become one of the most famous buildings in the world—a giant, orb-shaped venue able to blow the minds of more than 17,000 people at a time, thanks in large part to the 160,000-square-foot LED screen that towers above its stage. That giant video wall isn’t just a technical gamechanger, however; its sheer magnitude quietly dictates what acts can play there, because Sphere isn’t just meant for performers who can fill an arena; no, it’s meant for artists whose visual legacies are as rich as their musical ones. In other words, it’s tailor-made for Dead & Company.

The supergroup—Grateful Dead mainstays

Bob Weir and Mickey Hart, singer/guitarist John Mayer, bassist Oteil Burbridge, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti and drummer Jay Lane—has been playing there since May and will wrap up its 30-date Dead Forever - Live at Sphere residency this month. Along the way, each show has sent audiences careening through time and space to experience touchstones from the Grateful Dead’s colorful history—1960s San Francisco, a 1978 concert at the Great Pyramids in Egypt, the legendary Wall of Sound P.A. system, and more. The result is nothing less than a multimedia epic that plays out over the course of two sets and

three hours each night, all soundtracked live by the band in fine form.

It’s a far cry from last summer when Dead & Company played its final tour, making the rounds one last time with live sound provider UltraSound (Petaluma, Calif.), which has worked with the Grateful Dead and its spinoffs since 1978. Sphere opened soon after the tour’s final show, however, and it wasn’t long before the opportunity to play a residency came along. The decision to play there was easy to make, but everything after that was a bit more complicated.

Shepherding the residency’s development, Mayer took on the role of creative director, while the band’s longtime tour director and frontof-house engineer, UltraSound CEO Derek Featherstone, became the show producer, and Sam Pattinson, managing director of creative agency Treatment Studios, led the project’s content creation.

Given that the show’s music and visuals are so tightly intertwined, getting content creation underway early was the top priority. Featherstone recalls, “It came down to, not really a pitch, but getting Bobby and Mickey together with John and myself, and presenting John’s vision and theme for the show—essentially reviewing his storyboards and talking about content concepts. Everybody in the band was in agreement and thought Mayer’s concept was a cool direction to go in. We started to plug away at it in November, and Sam created a team of animators and artists who were working endlessly up until we started in May. Meanwhile, I’ve been working on producing and also the administrative side, keeping the timeline and budgets in order—or out of order, depending on how you look at them.”

Creating visuals for the massive media plane (the official term for the LED screen) was particularly challenging because the content had to work with an improvisational band that never plays a song the same way—or length—twice. Throw in perpetually changing set lists and a repertoire filled with hundreds of songs, and things only get more complicated. “The show needs to stay as fluid as a Dead and Company show typically would be,” says Featherstone, “because the one thing we were conscious of was to not build a show where the band was worried

the whole time about timecode or video sync.”

Ultimately, Treatment Studios developed more than seven hours of visual content, roughly five hours of which get used across the three shows the band plays in a given residency weekend. Content isn’t tied to specific songs, however, because every show’s running order is different. To help create each night’s set list, Dave Matthews Band FOH engineer and longtime UltraSound employee Tom Lyon coded a database of every Dead & Company song ever played, based on information from SetlistFM. Analytics from Nugs.com were added, calculating the 10-year cumulative average length of each song in the band’s repertoire, followed by AI data determining the most popular songs, and streaming counts that indicated which tunes have been listened to the most.

“We’re looking at each song and saying, ‘this piece of content would fit here’ or sometimes we’ll lay the content out and say, ‘this song would fit here,’ so it’s a pretty creative way of building a set list, and a true collaboration between Weir, Mayer, a database, and myself,” says Featherstone. “One piece of content might be eight minutes long, so you say, ‘that wouldn’t work with this acoustic song, but it might fit this one.’ Having the average timing for every song played over the last 10 years became crucial in lining these shows up. We’ve already passed playing 100 different songs so far.”

Every performance is heard through a house audio system comprised of more than 1,600 speakers around the venue, centered around a proscenium array of 464 Holoplot X1 speaker modules located behind the LED panels so as

not to block the screen. The result of all those speakers is spatial audio that is used not so much to send sounds whipping around the room— although it can do that—but rather to ensure everyone hears the same level of audio quality. The unique nature of the P.A., however, requires rethinking how a mix is approached.

“We’re sending about 38 to 44 channels of audio out—and there’s no left or right; you’re mixing in blocks,” says Featherstone. “Behind the stage above the band are five primary clusters you’re working with; the ones in the middle are the most in-time, because they’re in the dead center of the room. If you put stuff too far off to the sides of the room, it creates a lot of slapback or giant comb filters. Say you put a snare in the furthest wide speaker clusters: you’ll hear several snare drums and that’s not what you want to be doing—but if you put a Hammond organ or something that’s less staccato over there, it sounds great. You’re building the whole mix up differently—a real change in workflow after so many years of mixing a certain way.”

Learning that new approach in the months leading up to the residency required building a miniature version of the venue’s P.A. at UltraSound headquarters, much as Phish did at Rock Lititz and U2 did in Europe to prepare for their Sphere runs. Both those acts have long worked with audio provider Clair Global, and Featherstone readily says, “Clair Global had a big role here building out this demo system.”

Recreating the P.A. required placing speakers on trusses to represent all the zones in Sphere, and then using the venue’s in-house DSP processing for practicing and checking the results. “They have some calculations where you can press a button in the Meyer Sound D-Mitri

system and change the virtual location you’re sitting in,” says Featherstone. “You’re mixing as if you’re in the mix position, and then you press a button and you’re sitting in Section 201; you readjust all the delay times on the speakers, and then you can understand how bad it sounds if you put the wrong things in the wrong places. That’s a crucial tool for getting in Sphere.”

It was a necessary one, too. Since Sphere doubles as a Vegas attraction, playing a 50-minute film multiple times a day, Dead & Company could only get two days of rehearsal in situ. “Coming into the Sphere, the key thing was getting everybody on inear monitors and used to playing with no amplified sound on stage,” says Featherstone. “In-ears are tricky to dive into when you have to versus when you want to, but you need them here. If you’re playing in the Sphere without in-ears, the latency can be up to 200 milliseconds by the time you hear the P.A. behind you; it’ll really set your timing off. During prior rehearsals in Southern California, we also put the monitor guys where the band couldn’t

see them and set up on-stage camera systems so that the band could communicate with them. We went through all that in advance so that when they showed up at the Sphere, they were used to the technology. Once we got in the building, we did a seven-hour rehearsal one day and another fourhour one—and then we just went for it.”

Hidden behind the LED wall, monitor engineer Ian Dubois mixes for Hart and Lane, while Lonnie Quinn mixes Weir and Chimenti, and Chris Bloch looks after Mayer and Burbridge, all three pros working on Avid S6L consoles. Up at the front-ofhouse position, Featherstone, along with longtime system engineer Michal Kacunel, is on a 48-fader Avid surface, with a pair of effects racks tied in over MADI streams, allowing him to use some favorite outboard gear: “I have a bunch of Summit tube compressors, old dbx160s and some UREI LA-3As and LA-4As to keep the tonality the same and retain that analog feel of the band.”

Meyer Sound Spacemap Go, a spatial sound design plug-in and mixing tool, is used for the

surround mixing. “We built Spacemap programs into the Avid, so that we’re feeding about 24 effect zones through our console, not the house D-Mitri system,” says Featherstone. “That way, at any given moment, I can pull up the plug-in and, say, take a vocal delay and make it run in a circle around the room, speed it up or slow it down, make something come from front to back or side to side. It’s freeform, which is how this band has to be approached, because everything’s always never the same.”

With that need for flexibility, the Avid desk’s snapshot feature is never used, keeping Featherstone actively mixing throughout each marathon gig. The biggest mix challenge inside Sphere, it turns out, is getting the vocals loud enough to be heard. “You have the sound system behind the vocal mics—like the Wall of Sound days—so you’re really working on keeping the P.A. out of the vocal mics,” says Featherstone. “We’ve always used gated foot pads where the musicians stand on it and it turns the vocal mic on. In the past, that let us use really nice condenser mics on vocals, but in this particular case, you really have to minimize the bleed even when they’re on the pad.” The band’s vocals are now captured with a mix of Sennheiser e945s and Shure SM58s.

With the residency now nearly over, all the months of preparation have paid off; fans have come out in droves to enjoy the spectacle of Dead Forever , making it another landmark in the history of a band that’s had plenty of highpoints already. “We’re six months into building this thing and it’s great to see it come alive, for sure,” says Featherstone. “Being in the middle of it, sometimes I don’t necessarily realize that, and then one night, I’ll be mixing and watching it and say, ‘Wow…this is a pretty cool show!’” ■

Budapest, Hungary—When is an arena really a stadium? When it’s Puskas Arena in Budapest, which despite its name is a stadium capable of holding more than 50,000 people—as proven recently when pop-rock band Hungária, first formed in 1967, recently played a reunion gig there.

At both the FOH and monitor positions, an Allen & Heath-centric system was used with dLive S7000 control surfaces paired with DM MixRacks at both mix positions. Tackling the FOH position were a pair of engineers, Daniel Toth and Zsolt Gyulai, with Toth, the chief engineer, overseeing both the band and vocal channels, while Gyulai primarily handled the sound design tasks using external insert plug-ins. They used Waves Soundgrid integration so that every lead vocal and instrument group received plug-in support from Waves SuperRack.

Meanwhile, Jozsef Sodar oversaw the monitor mix position on his own dLive S7000, looking after musicians and lead vocalists, resulting in a dozen monitor mixes heard via more than 30 wedges, six stereo IEMs and eight Allen & Heath ME-1 personal mixers on stage. Sound engineer Tamas Ditzmann was also on-hand as the dLive System Support specialist, having designed the Allen & Heath system used for the concert. Ditzmann also oversaw the ME-1 Personal Monitors for the gig.

The band’s setup included 90 analog inputs for the band, vocalists, and

B-stage instruments, with an additional 16 Dante inputs for the wireless microphone signals of the lead vocals. Featuring a DM48 MixRack and three DX168 expanders, the monitor mixing system handled the Master Clock and Gain, and transmitted 128 channels to the FOH mixer via a GigaAce card. The FOH MixRack then fed the P.A. system through AES/ EBU and redundant analog outputs. “Overall, we can say that the Allen & Heath dLive system fully met and exceeded the challenges of a stadiumsized concert,” commented Toth. “It provided exceptional sound quality and reliability.” ■

Vancouver, British Columbia

It’s been 40 years since the first TED Conference was held, and to mark that anniversary, TED2024 recently returned once again to the Vancouver Convention Centre. Central to the event is the TED Theater, a customdesigned, 1,200-seat auditorium that hosts the conference’s marquee presentations. “TED2024: The Brave and the Brilliant” had something new in store for attendees, however, as it added a 7.1 immersive system from longtime sound partner Meyer Sound, which has worked with the conference since 1992 and provided audio in the TED Theater since 2019.

The overall system, designed by Meyer Sound senior technical support specialist David Vincent, featured two flown arrays of 12 Leopard line array loudspeakers, supported by three 1100-LFC low-frequency control elements and two VLFC very-low-frequency-control elements. Rings of UPQ-1P and UPQ-2P loudspeakers served as delays, with UPM-1P ultra-compact

loudspeakers as lip fills and 32 MM-4XP miniature self-powered loudspeakers put to work as floor fills. The surround system centered around MINA, UPA-2P, UPA-1P, and UPM-1P loudspeakers. Adding immersive sound provided a new dimension to some presentations.

“We were able to take them across a desert, under an ocean, inside of a busy restaurant, and give them an experience of being ‘inside’ a song, as an artist performed live, in front of them,” said FOH engineer Michael Dunwoody. That said, the team used surround effects to enhance the audience experience, not overtake it. “We asked ourselves, ‘Should it be on and in play the whole time? Our answer was a unanimous ‘no.’ The effect needed to be used tastefully and only when the show and content warranted it.”

“The audience doesn’t know what a 7.1 system is,” said FOH pro Alex Rodriguez. “They know that when they were here, it sounded really good, or it was clear, or it gave them the chills.” ■

New York City—S.E. Hinton’s coming-of-age novel The Outsiders has been reimagined as a Broadway musical, and it’s nothing less than a hit. The show landed a dozen Tony Award nominations and took home not only Best Musical but also Best Sound Design of a Musical, due to the work of sound designer Cody Spencer.

That sound design centers around an L-Acoustics L Series loudspeaker deployment using L-ISA technology, all fielded by PRG inside the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre in Times Square.

Two centrally flown sub arrays of three KS21 each are bolstered by two more KS21 positioned left and right, under the stage. The balcony delay system features five Scene arrays of two A15 Focus flanking Extension arrays of two A15 Wide. Seven spatialized X8 speakers mounted across the face of the stage serve as front-fills for main-floor seats, and various combinations of X12, X8, and 5XT are deployed as other fills, as needed. A combination of LA7.16, LA12X, and LA4X amplified controllers drive the system.

“We also have a row of compact 5XT speakers for the middle of the orchestra that helps get the high end to the very front of the overhang,”

Spencer said, “and then another row of X8 as spatial fills to fill in the back of the orchestra underneath the overhang.” The main system’s surround arrays utilize a combination of X8 and A10 enclosures, while the balcony surrounds are four Syva, deployed two per side.

Spencer and his team, including L-ISA programmer Stephen Jensen, production audio lead Mike Tracy and front-of-house engineer Heather Augustine, went all-in on immersive sound and L-ISA technology. “The reason that I chose to use L-ISA is because early on, in communication with my director, music department and choreography team, we wanted the audience to be encompassed by the sound. With much of the show, the audience is ‘inside’ the actors’ heads—it’s a play in which much of the action is being recalled by characters instead of happening in the moment. Using L-ISA, we’re able to get people feeling the sound from all around them at all times. Early on in the show, for instance, our lead character gets kicked in the face, and you can hear the kick, but then you also hear his ears ringing—not just in front of you but all around you. Those kinds of effects help to make you feel like you’re actually part of his world.”

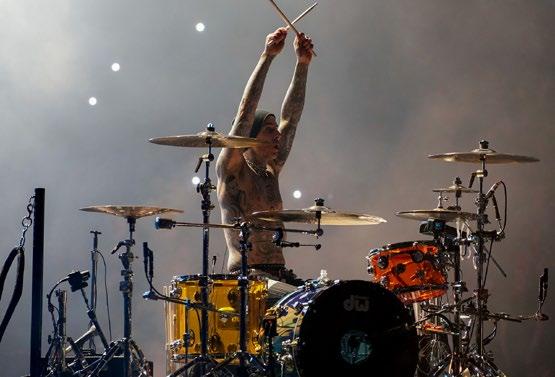

Reunited after a decade apart, the pop-punk pioneers are blasting their way through the stadiums and arenas of North America.

By Clive Young

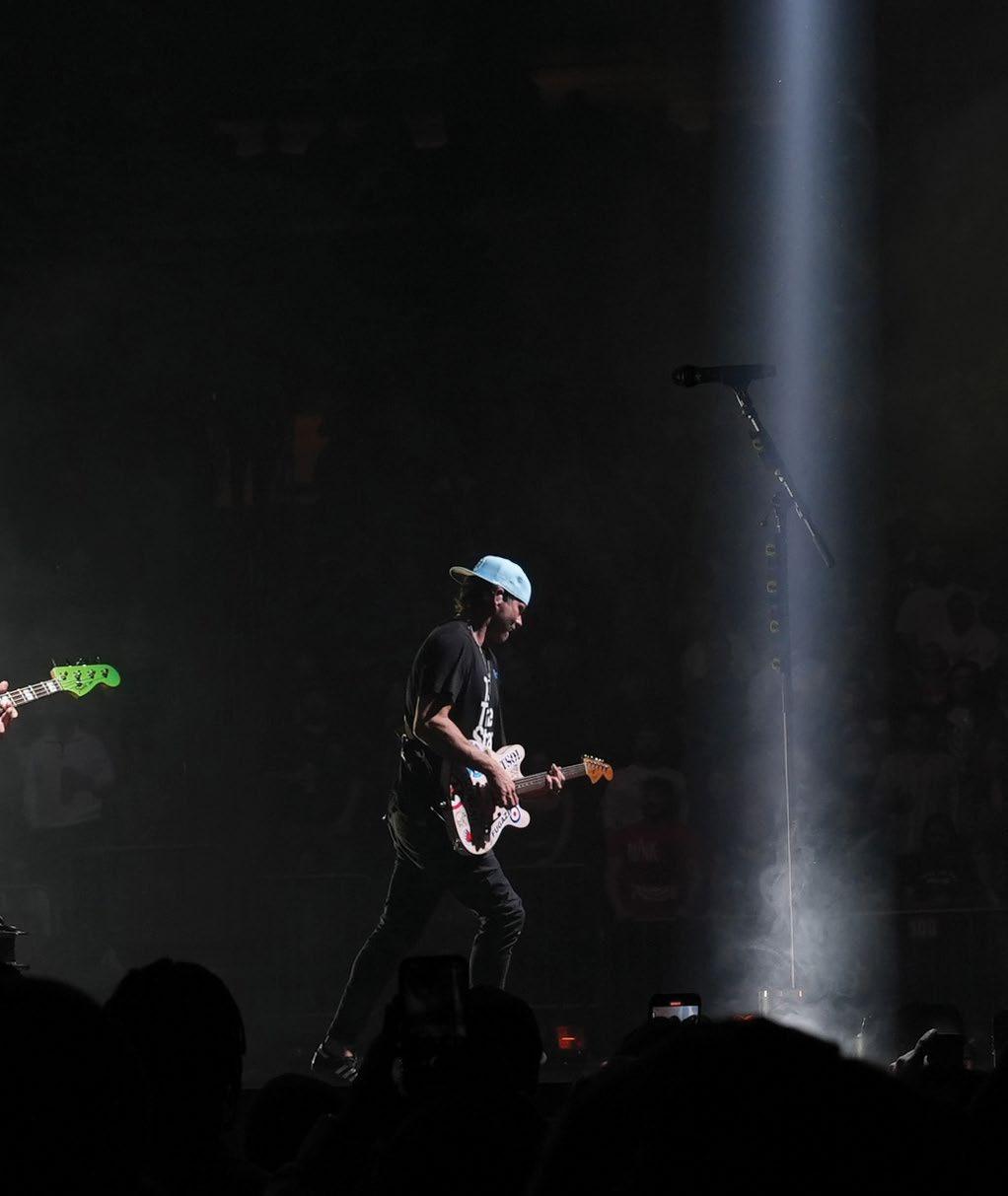

Despite first gatecrashing the scene nearly three decades ago, 2023 was arguably one of the biggest years ever for Blink-182. The band’s classic lineup of Tom DeLonge, Mark Hoppus and Travis Barker reunited for the first time since 2014 for a 60-plus date world tour, and capped it off with a new album in October, the aptly titled One More Time…. Of course, with a name like that, it was inevitable they’d return to the road for another go-round, so the pop-punk pioneers are currently lighting up stadiums, arenas and a handful of sheds across North America.

Along for the ride through it all are engineers Charles Izzo and Ray Jeffrey at the front-ofhouse and monitor mix positions, respectively, overseeing audio systems provided by Clair Global. With most of the current North American leg performed in-the-round, the pair have their work cut out for them, bringing the

Nearly all live mics

are

band’s exuberant, clean punk sound to every seat in the house.

“For the most part, it is just a straightforward rock show,” said Izzo, who’s mixed the likes of Halsey, Childish Gambino and Portugal. The Man. “I try to stay as true to the albums as possible; I feel like they’re classic records that everybody knows, so any effect that happens on the record, I duplicate. As far as the live element goes, I keep it really aggressive with an in-yourface, ‘rock show on top of the record’ sound.”

Building that sound on a Yamaha Rivage PM10 console, Izzo has snapshots for every song, explaining, “There are changes that need to happen, but a lot of the root, foundational stuff—drums, guitars, bass—stays pretty static. It’s the other elements that come and go that make it more dynamic. For instance, a lot of the newer songs have more going on than the older records do—synth sounds, cool percussion elements and things of that nature—so putting all that together keeps it interesting to mix.”

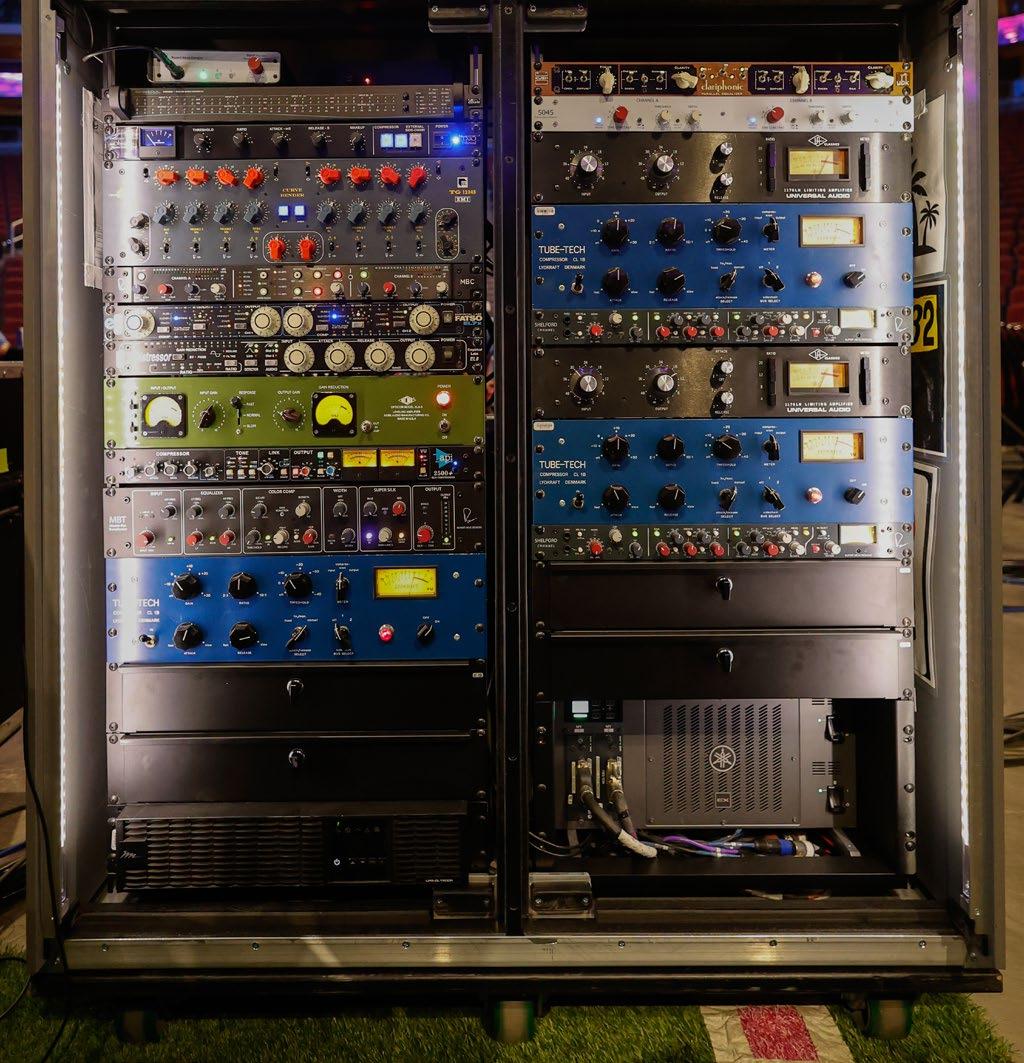

Izzo opted for the PM10 based on word of mouth and an array of options that match his mixing style, noting, “The fact that it has a lot of Rupert Neve Designs components, Bricasti reverbs and Eventides built into it was a big, big push for me to go that way. My analog rack is already a double-wide, and if I used a different desk, it would probably be a triple-wide. I feel that as P.A.s get better, the expectation—and the ability—to have better, studio-quality sound is changing as well; I think that’s why more engineers are leaning toward bringing studio gear out on tour now.”

You can count Izzo as one of those pros, too, because while he uses a smattering of SoundToys plug-ins hosted on a Waves SuperRack Performer rig, the FOH outboard racks are stuffed with high-end gear, much of it from Rupert Neve Designs. The mastering chain on the left-right bus is built around a Dramastic Audio Obsidian compressor leading into a Chandler Limited EMI TG12345 Curve Bender mastering EQ,

followed by a RND Master Bus Converter. Also residing in the same rack are an Empirical Labs Distressor for bass with an Acme Audio Opticom compressor on the parallel bus, while the drum parallel bus gets an Empirical Fatso, and the guitar bus benefits from an API 2500+ bus compressor and RND Master Bus Transformer.

Also in the racks are identical vocal chain setups for Hoppus and DeLonge, each running from a Universal Audio 1176LN into a TubeTech CL 1B compressor, followed by RND 5045 Primary Source Enhancer and Shelford Channel units, before closing out with a Kush Audio Clariphonic parallel EQ used to bring out the vocals and make them more present in the mix.

Capturing those vocals onstage are DPA 4018VL handheld vocal mics on Shure Axient wireless. “I feel like DPA is such a pop-world thing,” said Jeffrey. “I’ve been working for Lorde for seven years, and that’s been DPA since Day One, so coming over to this tour, the first phone call with Charlie was like, ‘DPA?’ ‘Yeah.’ That was our first choice—and then

the band had never used them! But Mark and Tom gave us their trust, let us run with it, and they’re very happy with them.”

The guitars run into a Fractal Audio AXE FX III while the bass hits a Neural DSP Quad Cortex, each continuing on to a Rupert Neve Designs 5211 mic preamp, so the only live mics onstage are the vocals and drums. With the exception of Josephson e22S condensers for snare bottoms, everything else is from DPA microphones, including a 4055 on the kick and 4099-Ds on the snare tops.

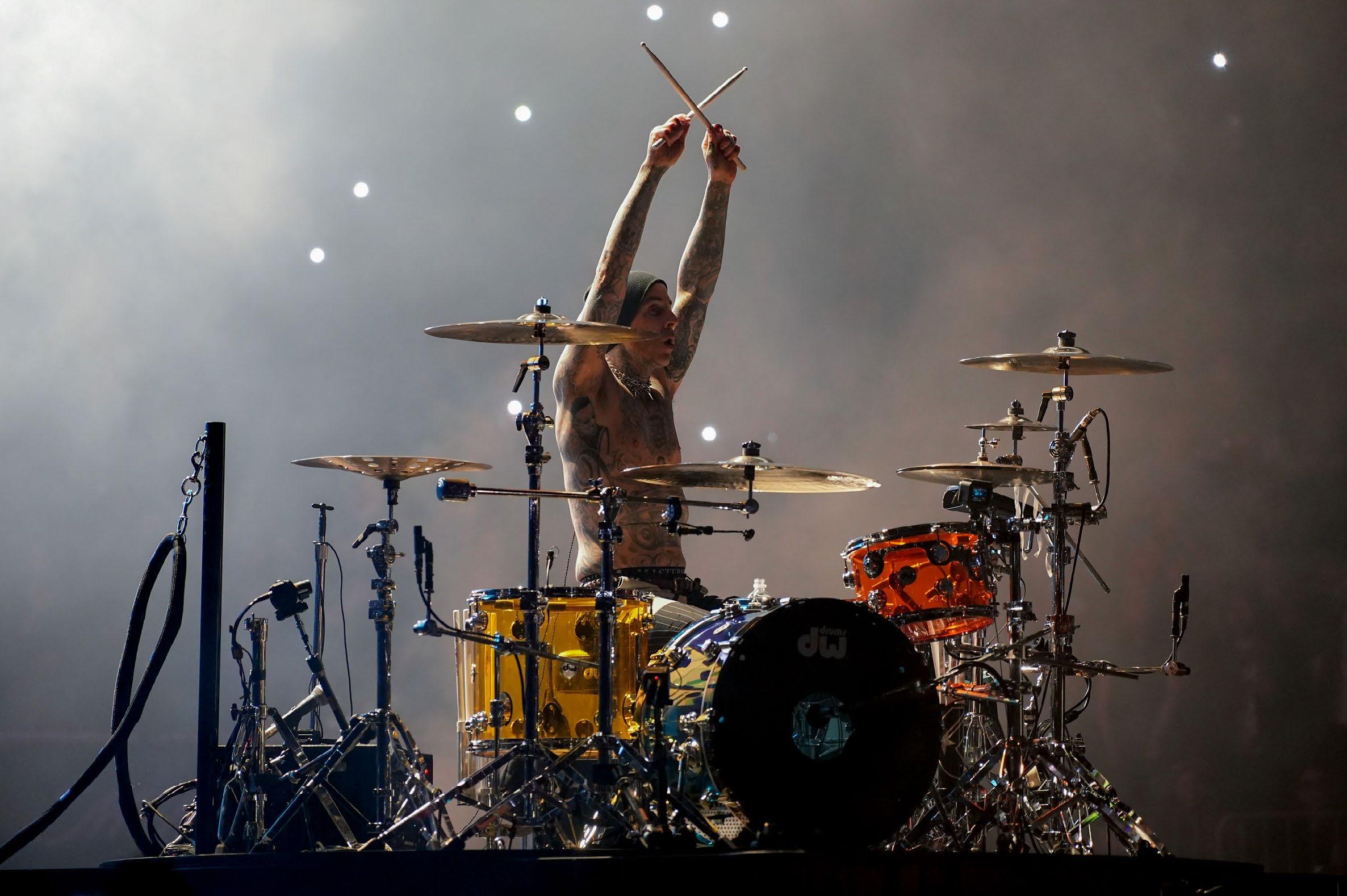

In a show full of highlights, one of the biggest is when Travis Barker’s drum kit takes to the air, flying and spinning around as he plays—a moment that is very cool but which also makes using overhead mics above the kit impossible. As a result, they use underheads instead, opting for 4015 wide cardioids to pick up the entire kit.

“They’re suspended out about 18 inches to two feet from the drum kit on arms from the crash and ride cymbals,” said Jeffrey. “Honestly, it was just trial and error moving them around to where we were getting every element of the kit, and they sound great.”

Because the drum kit takes to the air, getting signal from those mics to the rest of the system took some brainstorming, too. “The creative team was trying to figure it out, and I said, ‘Well, this could just be two ethernet cables,” said Jeffrey. “We have a little five-space rack with Rupert Neve RMP-D8 mic preamps, right on the riser with Travis, sitting in the back running Dante; Charlie controls the Dante, and they sound amazing.”

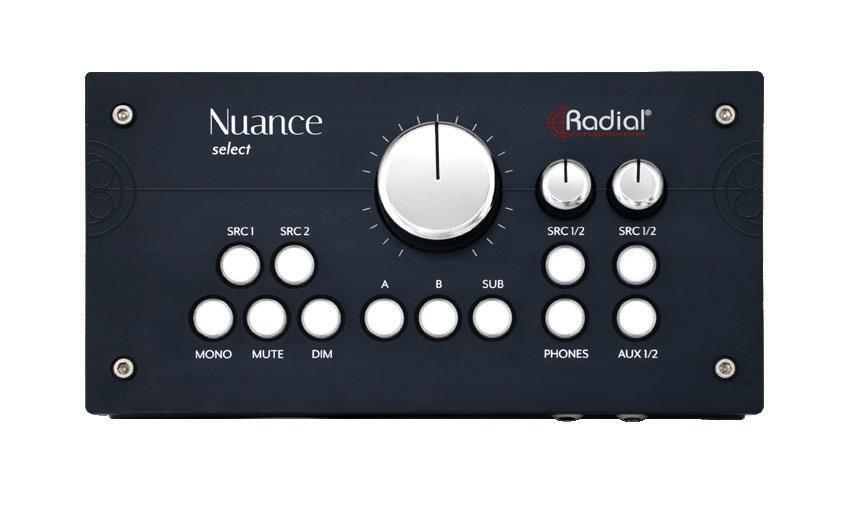

Over in monitorworld, Jeffrey mixes on a DiGiCo Quantum 5 console, and his supplementary outboard gear, much like FOH, is centered around RND 5045s and Shelford Channel units, Bricasti M7s, and a Waves SuperRack setup for a handful of plug-ins.

While the stage sports some “Texas Headphone”-style drum fills that are L-Acoustics KS21s with A15 tops, the band hears its mixes through Sensaphonics and JH Audio in-ear monitors via Wisycom wireless. “First and foremost with Wisycom is the sound quality,” said Jeffrey, “but then a big bonus is you can keep the same rack and travel the world. You can do a South America tour and then head to the

U.K. and follow it up in L.A. With the RF environments now being kind of nasty, you need it.”

The result is a relatively quiet stage, a factor aided by the use of d&b audiotechnik P.A. at each stop, covering arenas with KSL boxes and stadiums with GSL systems bolstered by KSL-Subs. “They’re great, especially in the round where we’re putting out that much energy into every corner of the room,” said Izzo. “We tried placing the subs in the corners, which is more traditional for inthe-round, then Christian Peterson, my SE, had the brilliant idea of doing center-flown subs. We were very fortunate that we had time at Rock Lititz before the tour to hang the P.A. twice, so we tried both and found that center-flown subs are far more cohesive for what the band plays, and there’s way more control on the stage with them. None of it is blowing back on the stage for Ray, which is a big, big plus for him.”

Getting the P.A. tuned up requires an extensive virtual soundcheck…and perhaps a test of the crew’s patience: “I put on the song ‘I Miss You,’” said Izzo, “which everybody in the room is probably tired of at this point because I play it about 30 times while me and Christian walk around every seat to make sure everything sounds right.”

The crew can look forward to hearing that song plenty more times, too, as the North American leg may end this month, but the group will head back to the U.K. for more shows before wrapping up with a spate of U.S. festivals. When all is said and done in the fall, Blink-182 will have played more than 120 shows in 19 months. ■

Look out Beverly Hills, Axel is back! It’s been 40 years since Eddie Murphy first starred as the rule-bending Detective Axel Foley in Beverly Hills Cop. He’s now reprising that role in director Mark Molloy’s debut feature film, Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F, which premiered on Netflix to kick off the July 4 holiday weekend. Sound, the director made clear, would be key in reviving the nostalgic 1980s feel of the original three films.

“From the first shot of the movie, when you see Axel Foley, Mark wanted this feeling of excitement, this readiness to join Axel’s team again,” says Chris Diebold, the film’s supervising sound editor/sound designer/re-recording mixer.

Eddie Murphy isn’t the only returning member of the franchise. On-screen, Judge Reinhold is back as Billy Rosewood, John Ashton as Sergeant Taggart, Paul Reiser as Detective Jeffrey Friedman, and Bronson Pinchot as Serge. Off-screen, re-

recording mixer Paul Massey (winner of the 2019 Best Sound Oscar for Bohemian Rhapsody) returned to the faders, 30 years after he mixed Beverly Hills Cop III alongside Scott Millan and Steve Pederson on a custom console with limited automation at Todd-AO Studios in Hollywood.

“Technology has evolved greatly since I started in Hollywood,” Massey notes, acknowledging his own understatement. “Everything was on magnetic film. A lot of the consoles weren’t automated—some were partially automated, just the faders. You’d mix for a week, take a hiatus, and come back trying to get analog recorders to match, and trying to get consoles to perform the same way and have the same settings. It was quite a task.”

This time around, Massey mixed music and dialog while Diebold handled effects at the John Ford Mixing Stage on the Fox Studio Lot in Century City, working from a combination

of an AMS-Neve DFC-3D Gemini console (Massey) and an Avid S6 (Diebold). Massey explains, “Both the Howard Hawks and the Ford Stages at the Fox Studio Lot have the option of S6s on both sides, DFCs on both sides, or a split DFC/S6 console combination. It works out really well.

“The main stages at Fox are two of just a few facilities in L.A. with dedicated engineers for each stage,” he continues. “That’s a great luxury and very helpful in terms of us reporting a problem and engineering responding. Bill Stein [Post Production Sound Engineer at Fox Studio Lot] has been on the Ford Stage for many years. He’s an incredible resource, guiding us through all the upgrades and different plugins, maintaining the consoles, the room, and the monitoring, and tuning the room. Tim Gomillion [sound recordist/mix tech] has been there with Bill for several years now. Together,

Paul Massey and Chris Diebold create a big, dynamic, theatrical-style mix— tailored to a small-screen premiere—with a nod to that classic ’80s sound.

By Jennifer Walden

they operate a really solid room.”

Because the film is streaming on Netflix, Massey and Diebold mixed natively in Dolby Atmos, checking downmixes to 5.1 and stereo while monitoring through screen arrays consisting of JBL 15-inch woofers with BMS coaxial drivers amplified as a three-way system, with Meyer Sound surrounds and Meyer 500-HP subwoofers.

“Knowing this was going straight to Netflix, I put a limiter on my master bus that matched the Netflix specs before we started the mix,” says Diebold. “This way, when we did the near-field mix—how most people will hear it—it wouldn’t be outrageously loud; it would translate better and sound closer to the original mix.”

As an action-comedy, Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F has high-energy sequences with vehicle impacts, crashes, explosions and shootouts, but the comedy lives in the dialog. Those performances—often ad-libbed by Murphy—sit at the heart of the film. “For [producer] Jerry Bruckheimer, dialog is king,” Massey says. “If you can’t understand the dialog, he’s the first one to point it out, which is great. It’s all about the story. Since there was so much emphasis on always making the dialog intelligible, we ended up with a very dynamic mix, but not a wide dynamic range. It maintained a very even flow throughout the entire film, and we didn’t have

huge amounts of peaks to deal with when it came to making the two-track mix. The overall internal balance didn’t need to change very much once we’d found our template to make the stereo mix fit within the streaming guidelines.”

In an interview for Netflix’s Tudum (a “behindthe-streams” site for Netflix content), director Molloy remarked that some of the funniest moments are when Murphy is improvising. Adlibbed lines aren’t repeated performances, so it was paramount to preserve production sound mixer Willie D. Burton’s recordings of those comedic deliveries. Massey uses a light touch of noise reduction and EQ during his predubs, he says, not overbaking the dialog with excessive

processing. “I like to keep a fairly full and rich dialog track through predubs to the final mix and only dig in at moments when I really need to, but not too early. Once you’ve dug in, you can’t really dig out.”

Massey’s dialog predubs took place at his Dolby Atmos facility in Ventura on a Harrison MPC5 console, which features onboard dialog processing tools as part of the built-in XTools suite of film-specific plug-ins. He says, “For the final mix at Fox, I have another Harrison rack in a road case that I interface with the DFC so that I have the same equipment. The Harrison and the DFC are my favorite consoles to work on.”

For ADR, Diebold chose ADR Supervisor Sean Massey, his mix partner’s son. “Paul wasn’t on the film yet when I reached out to Sean; I love working with Sean—he’s one of the best,” Diebold says. While there was a decent amount of ADR recorded for the film, the driving scenes, surprisingly, required very little, even in the convertible car. “There was obviously wind, traffic, engine noise, suspension creaks, and so on, but dialog supervisor Susan Dawes and editor Jim Brookshire did a great job cleaning that up,” Massey says. “Those convertible car scenes only had a couple of ADR’d words here and there.”

A snowplow chase—where a snowplow smashes into cars, and smashes cars into other cars—proved to be one of the most challenging scenes to mix. There’s massive music (composer Lorne Balfe’s

score hits hard up front and is then overtaken by Bob Seger’s “Shakedown”), radio communications blare inside the cab, and ATVs race by.

“We went back and forth to find the right balance of effects and music to make it exciting and big,” Diebold esplains. “It also had to be fun and quirky, so on the sound design side, whenever they’re inside the cab, we added funny suspension creaks, but the fun truly comes from the music being played really loud.”

Massey ended up using a lot of compression and EQ on the dialog to get it to sit in a very narrow window amid the music and effects in the scene. He recalls: “Everyone wants the music to be loud, and effects to have big moments as well, plus Eddie [Murphy] is laughing and making jokes the whole time. To make it work, I’ll take the music right up to the beginning of the dialog, apply compression, EQ and a little bit of level, and then duck the music around the dialog. Once that’s cleared, Chris can decide how much of the high- and mid-frequency sound effects he needs to subdue slightly to allow the dialog to poke through.”

It’s a long action sequence that builds over five minutes to a comedic crescendo. Massey and Diebold found that if they mixed something too loud at the beginning, then they’d lose the arc and it would feel flat. “We had to lead the audience through the story, but also through the emotion and danger of the chase up to that comedy moment at the end,” Massey says. “Each mix maneuver required us to then watch the entire scene again to make sure it was still working.”

This was also a sequence that Molloy wanted to sound very ’80s. “That means a really full, really big, really loud, really compressed sound,” Massey explains. “As a first-time director on the mix stage, Mark wanted a lot of things loud all the time. We had to give a bit of guidance as to how to highlight elements in that wall of sound so we could still have a dynamic mix that was intelligible and would fit Netflix’s spec. We got there in the end, and we’re very proud of the mix.”

A helicopter chase scene was another actionpacked moment where the comedy needed to shine. On the sound effects side, Diebold worked with sound designer Randy Torres to record an Airbus H125 helicopter. The three-bladed vehicle used in the film has more of a turbine type of sound, according to Diebold. It’s very different from a typical two-blade helicopter that produces that classic “whop-whop-whop” sound.

Diebold and Torres spent three hours recording at the Oxnard Airport in Ventura County, Calif. Onboard the helicopter, Diebold used a Neumann RSM 191 microphone feeding a Sound Devices MixPre-6 digital recorder. “I love to use Mid/Side setups because it’s monocompatible,” he notes. “That translates well in the film environment when you’re panning sounds to discrete channels. With stereo effects, sometimes you get phasing issues.”

Torres, meanwhile, was on the ground

capturing super-fast helicopter pass-bys using a Schoeps M/S rig and another Sound Devices MixPre-6. They also set up distant mics to capture the pilot’s crazy maneuvers and the super-low flyovers. Diebold also had a Sanken CO-100K onboard, “because you never know what you’re going to get in the super-high frequencies when you pitch it down.”

Diebold wanted to mount microphones outside of the helicopter, but it turns out that’s not legal. “Mark ran into the same issue when he was filming it,” he says. “He did have one onboard camera, professionally mounted on the base of the helicopter like they do for news helicopters. So to record an exterior, onboard sound, we ended up opening the door. I tried to stick my head out and record the blades closeup, but the pressure and wind from the blades were unbelievably strong. It almost tore the microphone out of my hand!”

While the helicopter recordings gave Diebold the ingredients needed to bring realism into a scene where a helicopter is making crazy maneuvers, he found that he also needed to introduce a bit of that classic “whop-whopwhop” to make it read for the audience. “There was a conceptual aspect, too, where we took the liberty to not make it realistic at all, using abstract sounds instead of realistic helicopter blades,” he says.

When Captain Cade Grant (the villain, played by Kevin Bacon) shoots down the helicopter, Diebold could have made it sound extremely menacing and scary; because this is a comedy and Axel is in the helicopter screaming, he made it sound funny. “The bullet impact ‘tinks’ are almost cartoonish, just to make sure that it stays funny instead of getting too serious,” he says.

When mixing any big action scene, there’s the question: Do the effects lead, or does the music? For a mansion gunfight near the end of the film, the excitement (and a bit of comedy) comes from the chaos of gunfire happening all around as a hail of bullets whiz by. Diebold says, “The bullet-bys and ricochets keep the energy alive. You can pan those in the surrounds and bring them down, and the frequency range doesn’t cover up the dialog, so you can keep them going even while there’s dialog happening.”

Massey’s challenge, then, was to keep the dialog feeling intimate and intelligible amid the offscreen gunfire and shouting. “It goes from wide

shots where you can see everything blowing up and guns going off all over the place and people screaming and shouting, to a closeup of fairly quiet conversation, almost whispered,” he says. “You can’t just drop all the off-stage action; you have to keep it going for the audience.”

The ’80s-style gunshots in the original Beverly Hills Cop had a slappy sound that Diebold wanted to achieve for Axel F, while also making them feel extremely beefy. His work on the video game Call of Duty: Vanguard provided invaluable experience in sound designing guns for the small screen.

“Cutting guns for video games is a different style than you’d cut for movies because you typically deal with smaller speakers,” he explains. “Having that mindset, knowing that Axel F is going to be played on TVs, we cut everything to sound extremely big with a lot of mid-low frequencies that will cut through the dialog and music. Also, we would turn down our monitors so we could hear exactly what it would sound like when things were turned down. That ends up making it sound a lot bigger in the overall scheme of things.”

Working with Torres and sound effects editor Phil Barrie, Diebold created a huge collection of bullet ricochets and -bys to carry them through the gunfight. “We needed enough material to put in the Atmos object tracks,” he says. “We used some recordings I did a few years back where I used a slingshot to shoot pennies and quarters over three mics that were set up in a line and spaced five to ten feet apart. It’s an old technique that gives you this really cool, flippy

sound. It’s like a bullet-by, but it’s twirly. That was used a lot in this movie.”

Crafting a comprehensible gunfight is challenging—what sounds will help the audience follow the action? Should the gunshot or the bullet ricochet be the hero at that moment? Making space for silence is important, too, notes Diebold. “When guns are shooting all over the place, it gets old and it loses its excitement. It helped to bring those sounds into the Atmos surround field. Much of the gunfire is happening on the second story, so they’re shooting down at everyone. It was cool to be able to utilize Atmos in that way.”

The sound of Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F might have an ’80s vibe at times, but the workflow definitely didn’t. During sound editorial, Diebold was embedded with the picture department at Bruckheimer’s facility while the rest of the sound team worked remotely. The facility’s editing suites were designed primarily for picture editorial, not sound, so the walls were thin and the acoustic treatment was lacking.

“When I moved into the room, we ordered a bunch of sound treatment material and added that to the space,” Diebold says. “I brought my 7.1 setup for monitoring; I had a Pro Tools rig and an Avid Media Composer rig as well. Both were on the Avid NEXIS server with the picture department, and we linked those together so that when I went into the Avid in my room, I could monitor levels by running everything through the FabFilter Pro-Q 3 plug-in to see

what kind of frequencies were happening.”

The environmental challenges notwithstanding, Diebold enjoyed the benefits of working this way. “It saves a lot of time for the sound team,” he says. “We can spend more time on the creative aspect and less time conforming and keeping up to date with the picture crew. Usually, when we give the picture department stems, by the time they get those, the picture has already changed significantly, so there are holes in the 5.1 or stereo bounce. By being embedded with the picture department, I’m more up to date with changes and the AAF can easily be conformed in the Avid.”

The workflow—conceptualized by picture editor Dan Lebental—consisted of Diebold cutting a scene in Pro Tools, bouncing down his numerous tracks into more compact stems, creating an AAF that was dropped onto the NEXIS server, then importing into Avid Media Composer. Once it was in the Avid, Diebold did a quick mix.

“Dan [Lebental] and I started working together using this workflow back in 2019 on Spider-Man: Far From Home,” he says. “It’s a full-circle process because I’m creating my own AAF for some specific scenes, as the assistant editors are doing a lot of heavy lifting in adding sounds like they normally would. Ultimately, it makes the mixing side easier because I mixed it, so I know the levels aren’t all over the place. Honestly, I think working this way more often— integrating it into more movies and getting the whole sound crew involved in this process—is going to make evrything better.” n

Just because a track from the 1990s had an all-digital workflow doesn’t mean that it will automatically play back, with all the necessary information, warns Iron Mountain Media and Archive Services.

By Steve Harvey

Afew years ago, archiving specialist Iron Mountain Media and Archive Services did a survey of its vaults and discovered that, of the thousands and thousands of hard disk drives that the company’s clients have entrusted them with, around one-fifth were unreadable. Iron Mountain has a broad customer base, but if you focus strictly on the music business, says Robert Koszela, Global Director Studio Growth and Strategic Initiatives, “That means there are historic sessions from the early to mid-’90s that are dying.”

Until the turn of the millennium, the workflow for record releases was simple enough. Once the multitrack was mixed, the 2-track master was turned into a piece of vinyl, a cassette tape or, starting in 1982, a compact disc, and those original tapes—by and large— then went into storage. Around 2000, with the advent of 5.1-surround releases, then in 2005 with the debut of the Guitar Hero video game, things started to get complicated. When rights holders went to the vaults to transfer, remix and repurpose some of their catalog tracks for these new platforms, they discovered that some tapes were deteriorating while others were unplayable. Not all assets had been stored under optimum conditions. Some recordings had been made on machines that were now obsolete, in formats that could no longer be easily played. And some recordings were missing.

In short, for the past 25 or more years, the music industry has been focused on its magnetic tape archives, and on the remediation, digitization and migration of assets to more accessible, reliable storage. Hard drives also became a focus of the industry during that period, ever since the emergence of the first

DAWs in the late 1980s. But unlike tape, surely, all you need to do, decades later, is connect a drive and open the files. Well, not necessarily. And Iron Mountain would like to alert the music industry at large to the fact that, even though you may have followed recommended best practices at the time, those archived drives may now be no more easily playable than a 40-year-old reel of Ampex 456 tape.

“The big challenge that we face is just getting the word out there,” says Koszela, who racked up years of experience on the record label side with UMG before joining Iron Mountain Media and Archive Services. Iron Mountain handles millions of data storage assets for a diverse list of clients, from Fortune 500 companies to major players in the entertainment industry, so the company has a significant sample size to analyze, he points out. “In our line of work, if we discover an inherent problem with a format, it makes sense to let everybody know. It may sound like a sales pitch, but it’s not; it’s a call for action.”

Many asset owners—labels, artists, artists’ estates—sleep soundly at night believing that their recordings are safe in a climate-controlled vault, Koszela notes. But just like tape, hard drives are susceptible to any number of issues

that may only be discovered when, for example, the project is pulled off the shelf to create an immersive mix.

“It’s so sad to see a project come into the studio, a hard drive in a brand-new case with the wrapper and the tags from wherever they bought it still in there,” Koszela says. “Next to it is a case with the safety drive in it. Everything’s in order. And both of them are bricks.”

Let’s say a drive containing a 1995 session does spin up. “You’ve got to update the Pro Tools session and you’re probably going to have to fix some plug-ins,” Koszela warns. “You’re off to the races, and you can create an immersive mix—but not if you wait too long and let that stuff die.”

A lot has changed in the world of digital media during the past three decades, so legacy disk formats like Jaz and Zip, obsolete and unsupported connections, and even something as simple as a lost, proprietary wall wart for the enclosure can be a challenge with some older archived assets. Based on years of experience, Iron Mountain has developed hubs at its facilities that can power up, connect to and read virtually any storage medium. If the disk platters spin and aren’t damaged, Iron Mountain Media and Archive Services techs can access the content.

As with tape, pulling an archived drive off the shelf and discovering any challenges to playing it

will typically only occur if there is a commercial imperative. “Most of the resources are freed up based on exploitation,” Koszela confirms, such as the label’s need for that immersive mix. However, an archived drive may hold an early transfer from tape at a lower resolution than is now the norm. If there’s enough budget, someone may need to go back to the tape and— hopefully, barring any issues—transfer it again at today’s accepted standard of 24 bits/192 kHz. Again, like tape, it’s not always that easy to pinpoint the exact asset that needs to be pulled. As with old tapes, where there may be little more than a ballpoint scrawl on the box label, the metadata—the writing, barcodes or other information carried along with the content—is also critical to finding the right disk drive in the archive, and the right version of the track that you are looking for. “The outside of the case might just have an artist’s name as an acronym,” Koszela says. “You don’t know if that’s a video session, an interview or what it is.”

While with UMG, Koszela would take the assets from the projects that came through Interscope’s studios and send them to the label’s archive team. “We started receiving a lot of black cases that didn’t have anything on them,” he recalls. “We would open up the drive, mount it, open up the catalog tree so we could see all

the folders, then screenshot and print it, and put that in the case.” It wasn’t the most elegant solution, he admits. “But it allowed us to quickly see what’s on the drive without going through the trouble of spinning it up.”

There are apps that now make that task easier. “Neofinder goes through the catalog tree and makes everything searchable,” he says. But these days, metadata might be embedded with the files on disk or in the cloud, not on a box or a case. Searching through that data could eventually be a task for AI, Koszela believes.

When people in the 1990s started producing music using DAWs, the entire workflow became digital, from writing to demo to tracking and mixing, but there’s a potential challenge there, years later, for anyone trying to find the complete and final master. “What if somebody brought something in on an Akai MPX [sampler] and they didn’t fly those tracks in, they triggered them?” Koszela asks. “Did the samples ever get copied to a master hard drive? And if they did, are they labeled?”

Similarly, in today’s production workflow, a

session could easily have been tracked at one studio, overdubbed at another, had strings added at yet another, then mixed and even remixed, perhaps across continents. “Who has the final copy of the session that consolidates everything?” Koszela asks once more. “If that master is lost, is there a copy or a version from earlier in the production workflow that will suffice, such as a producer’s, engineer’s or studio’s backup copy?

“It’s a plus that the data’s probably out there somewhere, but it’s also a minus, because there’s so much of it, and in so many different states of

completion. Who’s got the right version? Is the master lost? Probably not, but will you ever find it? Possibly not.”

Smaller entities, like independent labels or artist’s estates, with little budget for asset preservation, are generally letting drives sit in the archive. The bigger labels are unlikely to find and address any issues unless an asset is being commercially repurposed. Without some proactive initiative, Koszela says, “My worry is that these assets will just be lost. People need to know that their hard drives are dying.” n

Unlock the true potential of your recordings with Primacoustic Room Kits, delivering unparalleled sound clarity and accuracy so you can hear every detail of your mix.

Scan the code to get an instant recommendation for your room.

Learn more at Primacoustic.com

By Barry Rudolph

Usually, solid-state processors are the progeny of their vintage, tube-based parents. However, the Bettermaker Valve Stereo Passive Equalizer is similar in form and function to its predecessor, the solid-state Bettermaker Stereo Passive Equalizer introduced in 2022. Both are stereo, two-band, passive equalizers with selectable frequency and variable bandwidth. Both versions work as standalone equalizers and/or can be controlled via a native plug-in supported by AU, VST or AAX hosts.

Parameter changes are bi-directional. In the plug-in, mousing a control knob, switch or a node in the spectrum analyzer is immediately visible on the unit’s front panel; likewise, changes made using the VSPE’s front-panel controls are indicated in the software. The VSPE interfaces with your computer using a USB cable—but no audio passes through it. The VSPE itself must be connected like any other analog stereo EQ, in the signal path with the plug-in inserted on the same audio.

A comparison of the listed specifications of Bettermaker’s Stereo Passive Equalizer with the new Valve Stereo Passive Equalizer reveals

that they are nearly identical, with the same performance, frequency choices, boost/cut ranges, and a Hi-Boost Curve that changes the Q for the high-frequency equalizer. I like that there are no rotary switches to replace; small, lighted pushbuttons step through frequency choices and are good for finding the sweet spot.

The differences between the SPE and VSPE start to emerge with dual-triode tubes (valves) used as output amplifiers. The Valve version has a Heat feature, which switches in another amplifier to drive the valve output amplifier and transformers harder. To compensate for the level increase, a 6 dB pad is inserted, and the unit’s output impedance changes from 1,200 ohms down to 30 ohms. By using relays, switching Heat in/out is seamless.

The VSPE has an exacting, semi-parametric high-pass and low-pass filter set; it runs like a conventional EQ plug-in—only in the software. These have slopes of either 12 dB/octave or 24 dB/octave, with the HPF ranges from 20 Hz to 500 Hz and LPF ranges from 1 kHz to 20 kHz. Setting this filter is my first step when developing an EQ for any source.

Like the Pultec EQP-1A Tube Program EQ, you can boost one frequency and, at the same time, cut at the same frequency. This contorts the resultant resposne curve as shown on the spectrum analyzer. The VSPE does the same trick but also adds high-frequency choices of 20 and 28 kHz to the standard Pultec frequencies of 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 16 kHz. The low-frequency section covers 20, 30, 60 and 100 Hz.

The main reason I am drawn to the Bettermaker Valve EQ is its smooth tube/ transformer sound controlled by a modern plugin interface. It is a time-proven, vintage design that benefits greatly from modern software with its precision control, preset memories and resizable GUI. For fast A/B comparisons, there is the handy snapshot window above the main screen for storing up to 32 snapshots—or, copies of presets. Changing snapshots, as with all VSPE controls, is automatable.

There is a switchable Auto Audition solo for hearing the range of frequencies affected by a selected EQ band. There are also stereo input meters but no output meters. The spectrum

analyzer shows the audio superimposed with color-coded EQ and filter curves. There is a drop-down menu for the operational preferences of the Analyzer that includes zoom, resolution, window size and more. These settings are saved with the presets.

Also saved with the preset is a unique feature called Control Resolution. There are 101 steps for Lo Boost, Lo Cut, and Hi Boost Curve, and 34 steps for Hi Cut. In Quantize mode, this is streamed down to 17 steps. Changing from low to high resolution does not affect alreadywritten automation. This mode is disabled in standalone operation.

The Connection Menu is used to connect and switch plug-in control of multiple VSPE units for Dolby Atmos mixing or for use on different tracks in your mix. I didn’t test this, but you would connect a USB cable from each VSPE to a hub, then select the desired unit from a window in the upper-right corner.

Controlling hardware gear via a connected plug-in or standalone software is a new trend— look for more popular outboard gear starting to be offered with and without front-panel controls. Case in point: My Eventide H9000R is a blank-panel version of the H9000 Ultra Harmonizer and controlled by the standalone software and/or the Emote plug-in.

Like with the black-panel SPE, behind the VSPE’s blue front panel is a single, large circuit board that holds all the switches, LEDs and the five mounted controllers. VSPE is powered by a 12-volt wall-wart with plug adapters for anywhere in the world.

Inside on the main board are a DC-to-DC converter, two matched inductors for the equalizers, associated ICs for the USB GUI interfacing, and the circuitry for driving the red LED rings around the controls. Low-noise, Burr-Brown op amps are employed, along with

a set of (Mil-Spec), high-reliability relays for the hardwire bypass and for engaging Heat.

A separate board has the tube output amps, with two (new-old stock) Soviet-made pencil vacuum tubes. These are carefully matched and tested twin-triodes that are soldered in place; they drive the two large Bettermaker TT-1 output transformers (one for each channel), which are made in Poland. The tubes and internal fuse would have to be replaced by the factory, if ever required.

Stick-on paper labels are used to identify the Heat and/or Reset buttons. The Gain/Reset button, when held down for two seconds, resets the entire VSPE. Tapping the same button puts the unit into a “secondary layer,” with Heat mode on and the Gain/Reset button (annoyingly) flashing red. The 5 kHz LED in the Hi-Cut band is also lit red, with the Hi-Cut control now becoming the Gain control used to set final output level and for overdriving the tubes and transformers.

All the other controls on the unit go dark and inoperative while in Heat mode. The equalizer controls are adjustable in the plug-in, or tap on the Gain/Reset button again and you’re back to the “first layer” for normal operation. For fast A/ Bs of Heat on/off, simply tap the 5 kHz button while in Heat mode. In my opinion, all Heat operation and control should be done in the software, seeing as a dedicated Gain control and Heat on/off button are already there.

COMPANY: Bettermaker

PRODUCT: Valve Stereo Passive Equalizer

WEBSITE: www.bettermaker.com

PRICE: $2,999

PROS: Classic passive EQ design that sounds great.

CONS: The software interface and instructions could be better.

I connected the VSPE to a stereo pair of balanced I/O channels from my DAW, placed in the chain before my Manley NuMu Compressor Limiter for a mastering session.

I had a reggae song with a very loud kick drum and bass guitar—super-big with a lot of subsonic level. The total energy was good until the bass player started to play a busier eighthnote pattern in the chorus. Then the whole bottom end became a muddy mess.

I set up two snapshots: a verse EQ with just a Hi boost at 6 kHz, and a second for correcting the booming low frequency on the choruses. I automated changing snapshots in Pro Tools.

For the corrective snapshot, I first set the digital filter to 24 dB/octave at 49 Hz. Next, Lo Boost was set to 2.8 at 100 Hz, with Lo Cut at 1.0. The Hi Boost Curve was very broad at 6 kHz and Hi Boost at 3.3, with no Hi Cut. The digital filters are set by mousing over their knobs to read their current value in a pop-up window; the filter’s action is displayed in red curves. You can grab these curves with your mouse and move them to your liking.

The Gain control was at 1.6, but that depends on how much level you want to drive the compressor. It was easy to get -10 LUFs with this all-tube chain—if you’re interested. Because of its high precision and Class-A operation, the VSPE makes a great two-band mastering/touchup style program EQ.

In dual-channel mode, the VSPE becomes two single-channel EQs selectable in the software; both channels are unlinked, so you can dial up completely different settings on each. I like dual mono mode for vocals, kick drums, bass synths, acoustic guitars and more. I tried dual-mono mode followed by an API 529 VCA-based stereo compressor/limiter for two clean electric guitar tracks and loved it. The Heat feature fattened them up nicely giving them a certain color in the track. n

By Steve La Cerra

Solid State Logic manufactures a wide range of tools for music production, but until recently, the company had not offered a stand-alone microphone preamplifier. That changed late last year with the introduction of the Pure Drive Octo (8-channel) and Pure Drive Quad (4-channel) mic preamps.

Both units feature SSL’s SuperAnalogue PureDrive microphone preamp technology originally developed for the Origin console, onboard A/D conversion at sample rates up to 192 kHz, extensive connectivity, and a USB interface for direct connection to a DAW. The subject of this review is the Pure Drive Octo.

The Pure Drive Octo occupies two rackspaces and has a depth of about 12 inches. The front panel is cleanly arranged, with (left to right) four ¼-inch instrument inputs, controls for each of the eight input channels, four setup buttons and a metering/status display.

The rear panel provides eight XLR mic/line combo jack inputs, four XLR AES/EBU outputs, dual ADAT outputs, a USB Type-C port, BNC jacks for word clock I/O (plus a termination switch), and DB25 jacks for line input, analog out/send, and return. A hard power switch and IEC receptacle round out the rear-panel features. Once the rear-panel switch is turned on, the unit can be powered on or set to standby using the front-panel power switch.

The circuit topology behind the Pure Drive Octo is what SSL describes as a “progressive analogue design,” with no potentiometers or relays in the audio path. Analog circuits are digitally controlled via front-panel controls, an approach that enables precise repeatability and matching between channels (within a dB). Onboard A/D conversion is (up to) 24-bit/192 kHz for AES or ADAT, or 32-bit/192 kHz via USB. Dual ADAT ports support 16 outputs at 44.1 or 48 kHz, or SMUX (dual-port) output at higher sample rates with reduced channel count (up to 176.4/192 kHz).

Each channel provides two knobs and two pushbutton switches.

The Gain knob varies from 5 to 65 dB in 6 dB steps, while the Trim control adds or subtracts 15 dB to those values in 1 dB steps. Pushing the Gain knob reverses the polarity; pushing and holding it briefly turns phantom power on or off (phantom-power switching was virtually silent). Pushing the Trim knob toggles the high-pass filter on or off (75 Hz, 18 dB/octave, fixed); holding it changes the input to Line. When an instrument cable is connected to any of the ¼-inch instrument inputs, the respective channel input is automatically set to the DI.